Pallada class cruisers (1899)

Imperial Russian Protected Cruisers: Pallada, Diana, Aurora

Imperial Russian Protected Cruisers: Pallada, Diana, Aurora

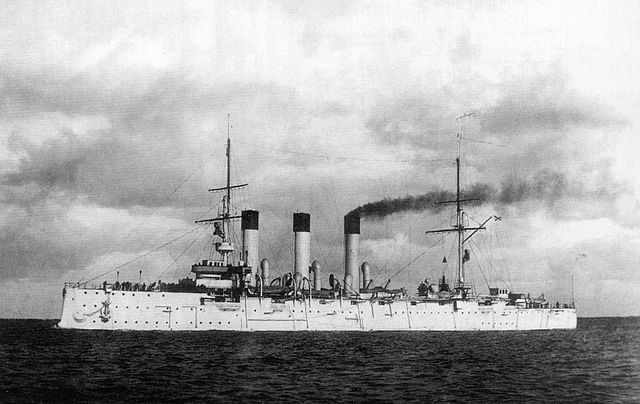

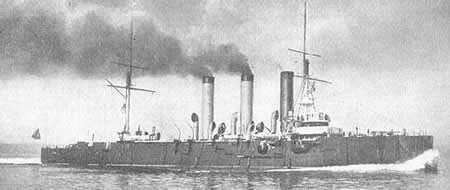

The Pallada-class cruisers (“Diana-type” in Russian) were three protected cruisers of the Imperial Russian Navy built for the late 1890s massive naval plan, bolstering the Baltic and new Pacific fleets. Intended for commerce raiding they were named after mythological figures and met very different fates: All three soldiered in the Russo-Japanese war, Pallada was captured by the Japanese and became IJN Tsugaru, but Diana and Aurora took part in WWI with the Baltic fleet and the latter took a historical role in the Russian revolution, still fully crewed today and listed as an active Russian Navy ship and museum ship in St Petersburg. #ww1 #russiannavy #russianpacificfleet #aurora #pallada #diana #russojapanesewar #1917revolution

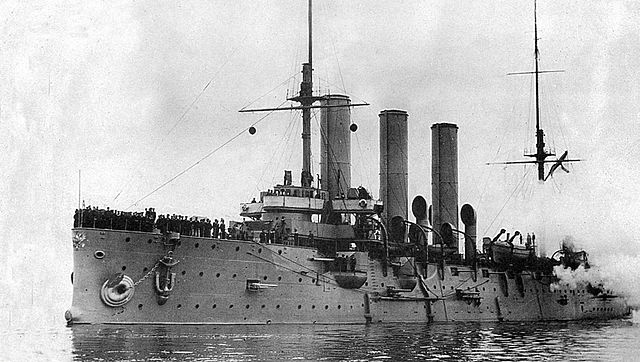

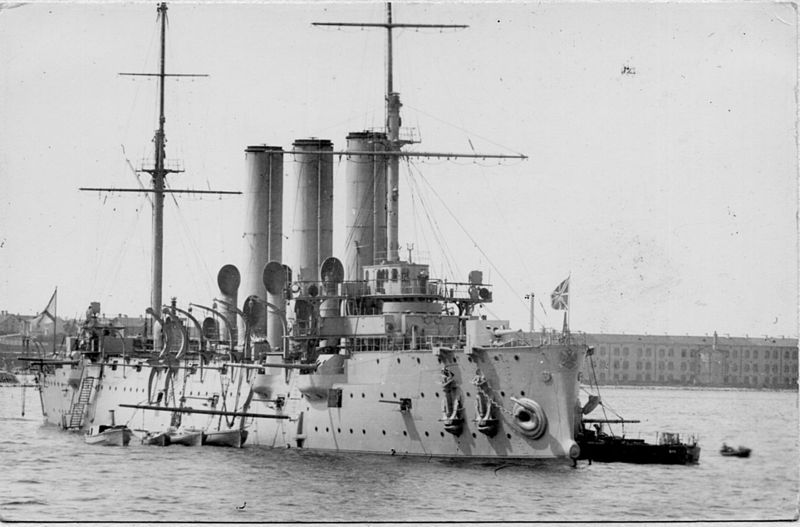

Aurora 1903

Genesis of the Pallada class

The international situation that developed at the end of the 19th century forced the Russian Imperial government to build up coastal defense forces but also to create a strong ocean fleet, with an emphasis on cruising forces. The main adversary of the time was indeed at start of the 1890s, Great Britain. There was a “russian scare” and rapid naval arms race between the two Empires. Simultaneously with the order of ships at foreign shipyards, it was decided to start construction of new cruisers on domestic yards as well. Thus, On March 2, 1894, on the instructions of Admiral N. M. Chikhachev at the head of the Naval Ministry, the Naval Technical Committee announced a competition for the best design, for a high-speed, armored ocean cruiser specialized in trade warfare. The goal was of course to prey on British communication lines.

Based on the examination of proposals, three were elected as winners, but none was eventually retained in the end. In between indeed, the frosty situation with Great Britain had been settled, and the Russian Empire now faced the growning new Kaiserliches Marine in the Baltic. The Imperial naval forces was to grow both qualitatively and quantitatively to face this, as the Germans had an ambitious plan, starting at the time with a serie of new battleships (the Brandenburg class), many new cruisers, and this was just the start. The Russian shipbuilding program was re-adjusted.

Without waiting for the final competition result as part of the additions made in 1895 to the 20-year shipbuilding program, three protected cruisers were ordered, the future Diana (Pallada) class. Main goal wit these was going on par with the German Navy first, and secondary states in Baltic like Sweden, or outside like the UK. The order for design and construction was issued on April 7, 1895 by the Main Directorate of Shipbuilding and Supply, of the Naval Ministry, to the Imperial Baltic Shipyard. It was state-owned and so the design bureau was practically also an admiralty design bureau by default.

Characteristics of these future cruisers had revised parameters to still face Great Britain and it was assumed that the project needed to at least match England’s most recent protected cruisers types, chosen as a basis for the new design. The one chosen at the time was the Astrea class cruisers, of which a “replica” was originally intended as a prototype. But this was was rejected, since, according to the design bureau engineers, “among other newest cruisers of different nations it does not represent the most advantageous type”.

Design development

The Pallada class were initially planned in 1897, in order to reinforce the Baltic fleet. Their role was seen as dual, as they were also intended in case of war to be sent to the far east and wage a commerce raiding campaign, mainly intended on British interests the main potential foe at that time since the armored cruisers arms race of 1890.

Within a month, the New Admiralty Shipyard of St Petersburg completed and submitted to the Marine Technical Committee three drafts of various displacements – from 4,400 to 5,600 tons. A few days later, another developed version with a displacement of 6,000 tons was added, the prototype of which was the latest British cruiser HMS Talbot. According to Russian historians, its initiator was the yard’s director himself, Sr. shipbuilder S. K. Ratnik. The cruiser was to be armed with two 203-mm (8-in) and eight 152-mm guns (6-in), as well as twenty-seven 57-mm guns (12-pdr). This option was later revised under instructions of General-Admiral Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich to replace the two 8-in with an all-152-mm guns battery, it this served as the basis for further developments.

A series of discussions on the new cruiser main caracteristic like its final dimensions, shape of the hull and location of the artilery as well as many other parameters were agreed upon. By May 1896, the final artillery arrangement, after many revisions, was fixed to ten 152-mm (6-in), twenty 75-mm (3-in) and eight 37-mm guns (2-pdr).

In November 1896, the project was revised for the last time, as engineers came with an unexpected additional overload of 182 tons. To eliminate it, it was decided to sacrifice part of the coal supply and abandon gun shields, reducing the number of main guns from ten to eight. This decision was facilitated the late 1896 “German threat” faded into the background of priorities whereas confrontation with Great Britain came back on the fore. On paper, the new cruisers surclasses their British counterparts whereas range and autonomy did not played a major role after the defensive agreement concluded with France, allocating naval bases to the use of the Russian Fleet in case of war with Britain.

Thus, the Imperial Russian Navy wanted more armoured cruisers versus battleships for pitch battles. They started to look at foreign armored cruisers designs. In particular, the Apollo class and Astraea class were looked at up with greater interest. Eventually discussion would lead to adopt a purely domestic design. Armor protection was light overall, but still way better design than previous Russian cruisers.

After the admiralty settled on the final design, funds were secured, and orders were placed for Pallada and Diana in December 1895. Aurora followed much later, in June 1897. Very long construction time, as ussian battleships, meant they were obsolete when entering service. Since Russian yards were at full capacity, other cruisers were delivered far quicker alongside, the foreign-built Varyag, Askold, and Bogatyr completed between January 1901 and August 1902 and considered way superior to the Pallada class, and notably top speed.

Detailed design and construction

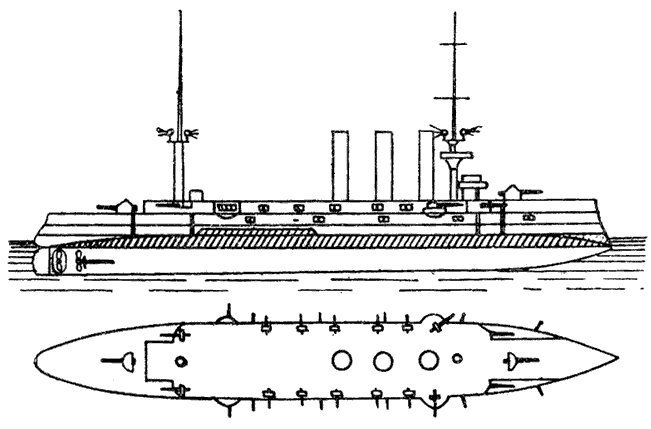

Brassey’s general outlines of the class

Hull Construction and general design

Hull scheme, general

On April 20, 1896, final specifications approved for construction stated a mean displacement of 6,630 tons (6,932 tons when fully loaded) corrected after the latest calculated data as approved by the Committee, with the dimensions at the waterline of 123.75 meters overall, 16.76 m in beam and down to the keel on standard displacement, 6.4 m in draught.

The hull was assembled from mild shipbuilding steel with a set of steel plating, flooring, double bottom and three decks: Upper, battery and armored decks as well as a forecastle and two gunnery platforms at the bow and stern. In the hold two more were located at each end, divided into compartments by 13 bulkheads. From bow to stern, a vertical inner keel was riveted to a two-layer horizontal keel and stems were cast in bronze.

Longitudinal strength was provided by 135 composite frames. An outer steel sheathing with a thickness of 11 to 16 mm was attached to a set of overlapping frames attached with two rows of rivets. The underwater hull section was sheathed with 102 mm teak boards topped by 1 mm copper sheets in order to prevent fouling. To reduce pitching, side keels 9 mm thick in steel were installed along the hull. Decks and platforms were covered with teak flooring with 89 mm oak boards laid around the upper deck guns notably.

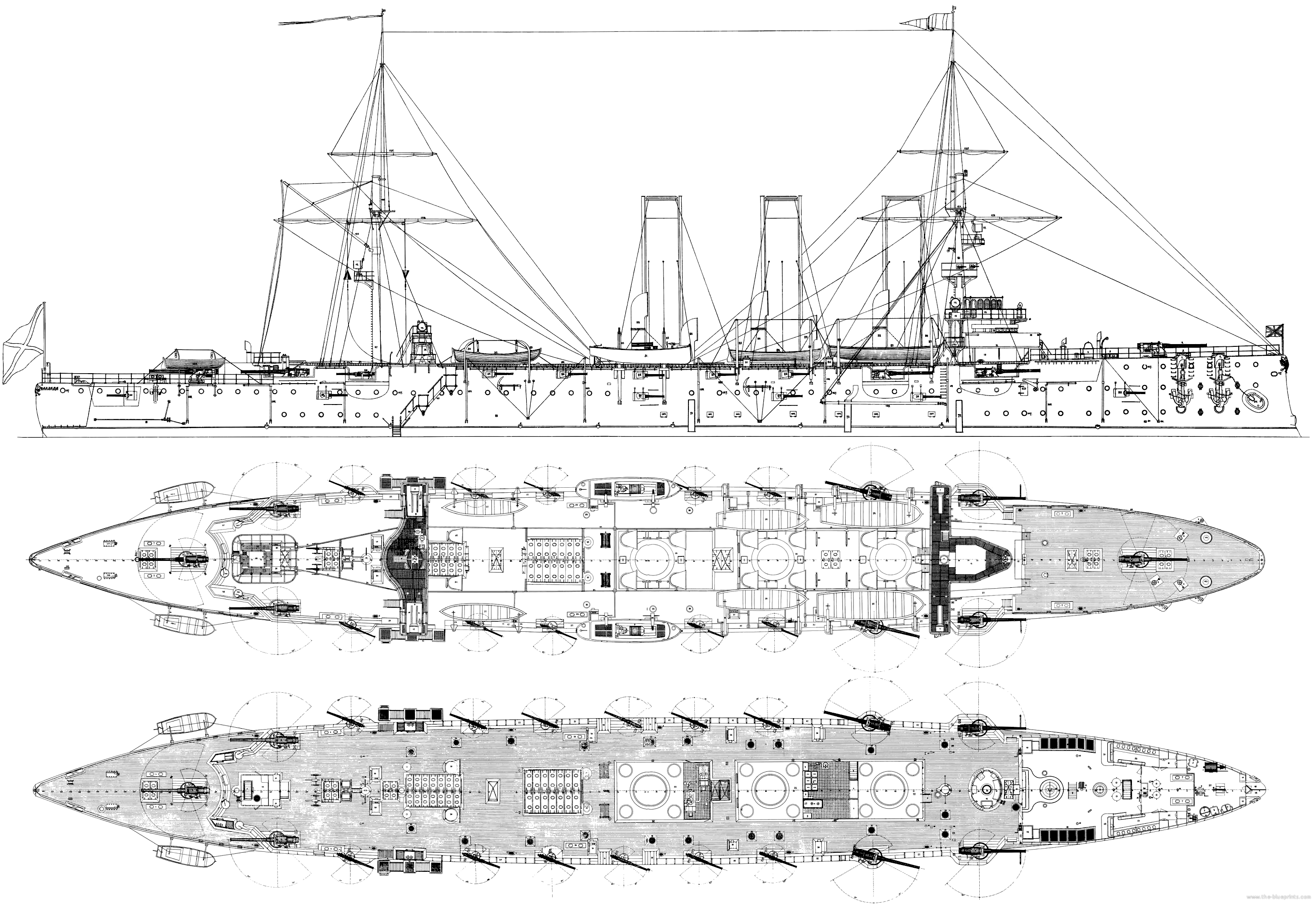

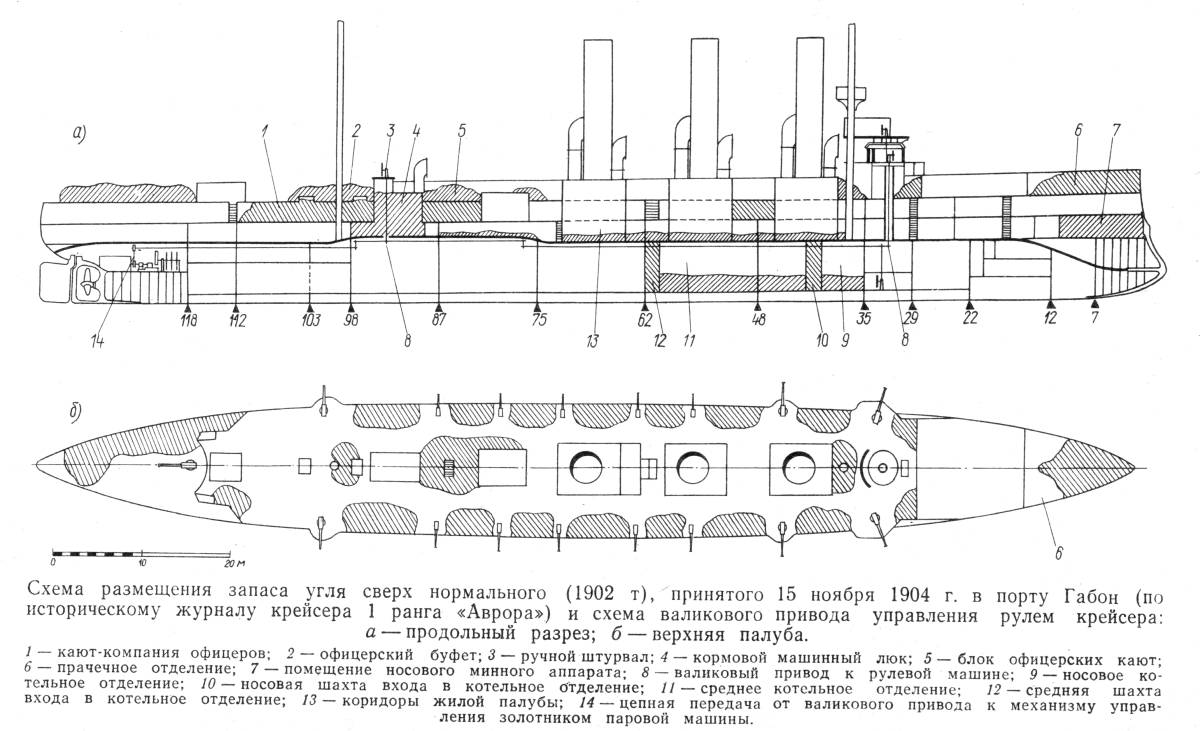

The HD rendition of the Pallada, based on the surviving Aurora. This is the best known russian cruiser class today thanks to this preservation as a historical landmark. This is probably a book scan (from the blueprints.com) which showed originally a legend, due to the numbered items visible.

The cruisers had two masts, a small winged bridge built partly above the conning tower, enclosed and with an open bridge around. The roof of it was not acessible. The CT itself was encased in a squared structure acessible by two staircases and half-deck high. The bow had a rounded deck top, and crowned as usual for the time by the Imperial eagle, golden leafed and painted. The forward torpedo tube was slightly protruding just above the waterline. The hull was ended by a ram bow as customary at the time, duly reinforced. The three main forward anchors were hold vertically under davits, two port and one starboard.

Alongside the primatic bridge, on the wings were located two light signal projectors, one for each side. The lower level extensions were supporting secondary artillery telemeters. The bridge platform was unusual in what the chadburn was located at the end of the projecting platform end forward.

Behind the bridge was located the foremast, a semi-thick French style military mast with external ladder enabling access to the main fore fighting top, fully enclosed and containing four of the light Hotchkiss guns, covering all frontal arc angles. There was no fighting top aft.

The Pallada-class cruisers with 413 ft long overall, for a beam of 55 ft and 21 ft draft made them not very hydrodynamic, with a defavourable hull ratio. The next amidship section comprised the #5 and #6 main guns on the main open battery deck, protected by walls and placed on sponsons for a better arc of fire. These were followed by the ten 75 mm (3-in) rapid-fire Canet guns on two levels, four on the lowel level, suceptible of water spray interference in heavy weather, and the remainder six on the upper open level but protected by walls, and not sponsoned, thus having a limited broadside arc.

This main deck also comprised the main machinery superstructure, with many access doors and air intakes, with three funnels clustered with tall gooseneck air intakes of various height, forward lower and aft taller pairs. Above the heads of the gun crews and resting on davits were located the service boats, four large yawls, followed by the two steam pinnaces on semi-external davits, and the two light pine cutters aft, on internal davits, abaft the main access and loading hold hatches to the inferior decks. Loading depending on a 300° traverse rotating boom crane attached to the near-top of the aft mast lower part.

The latter supported no aft fighting top but a yard. Like the foremast, the aft mainmast was composed of two levels, and the top masts a top yard, which were rigged as for holding sails, which were planned but never mounted unlike the 1880-90s cruiser generation of the eastern cruisers such as Novik, Rossia and Gromoboi. Like the foremast, it also mounted a light projector platform. The aft bridge was limited to the same two-level wing platform, with telemeters on the lower and signal lights on the upper level. The main access doors and collapsible access flexible staircases were located also there. Aft of the mainmast was located a prismatic structure with a platform ending with a small aft steering cabin. It seems the two undercarriage Baranowsky guns were installed there also. The two main guns aft were semi-encased in this structure. The stern was pointed, rounded, with casemated, recessed aftermost 3-in guns. There was also a pair of small yawls on external davits.

The number of portholes was limited on the lower level, with just a serie aft abaft to the mainmast, a serie of coaling hatches above the main armor deck, and a serie of forward portholes forward, ending befire the main anchors, and a second battery level serie, including some in sponsons, and an upper serie on the forecastle at battery deck level, making for three portholes levels forward, enchancing their tall bow.

Armor Protection

Protection was limited, as for protected cruisers at the time, to an armored deck at the waterline level, ranging from 2 to 3 in (51–76 mm) in thickness, the largest being on the slopes. They also had a forward Conning tower, with 6 in (152 mm) thick walls with was coherent with her own armament. Its roof was probably around 76 mm (6 in). No particular attention was given to underwater protection apart the usual compartimentation and double hull for some lenght.

The armor belt was not provided in the initial construction project, so all vital like the engine and boiler rooms ans well as the steering rooms and ammunition stores, but also the central combat post and underwater torpedo tubes were protected by a unique turtleback protective deck 38 mm ( in) thick for its horizontal section, gradually thickened to 63.5 mm () towards the sides and ends to face incoming horizontal fire while presenting well angled slopes.

The conning tower located on the second tier of the foerecatle was had 152-mm (6 in) armor walls. The funnel crowns, ammunition elevator shafts, control pipes above the armored deck were 38-mm thick (). The main artillery only had a 16 mm (0.55 in) steel shields to protect guns crew from shrapnel unlike what was decided initially.

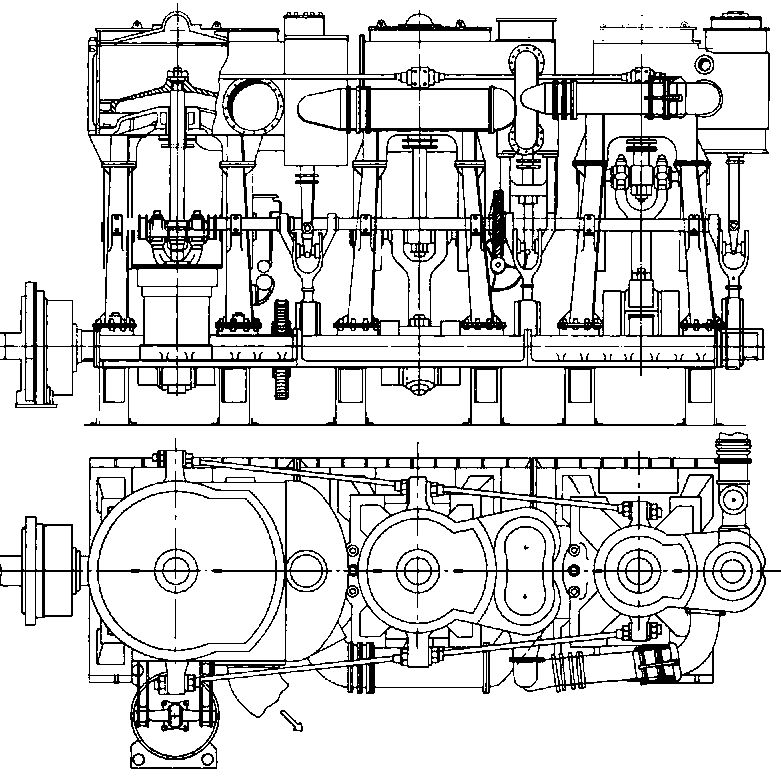

Powerplant

The Pallada class were powered by three triple-expansion steam engines (VTE), fed by no less than 24 small tubes Belleville boilers, rated for a total of 13,000 horsepower (9,700 kW). In fact it diverged among ships, with some rated at 11,971 and others (Aurora) at 13,100 ihp (8,927–9,769 kW), for an average top speed of 19 knots (35 km/h; 22 mph) as designed. Overall range was not impressive for commerce raiders, with just 3,700 nautical miles (6,900 km; 4,300 mi), enabled by a coal stock of just 972 tons. This radious was achieved only at cruise speed, 10 knots.

Three three-bladed propellers had a diameter of 4.09 m. The three-cylinder triple expansion steam engines were designed for a total ouput of 11,610 hp for a shaft rotation speed of 135 rpm. The 24 Bellevile Boilers rendered for the steam engines a pressure of 12.9 atm, but without economizers they reached 17.2 atm. They were placed as follows: Eight boilers in the bow and stern compartments, six in the middle one. It’s the expander, which saw the pressure was reduced from 17.2 atm to 12.9 atm at the inlet to the steam engine. Total boiler area was 108 m², and total heating surface 3355 m². Each steam machine had three cylinders wit a bore of 800, 1,273 and 1,900 mm, designed for a working pressure of 12.9 atm highest down to 5.5 atm medium and even 2.2 atm at the lowest expansion phase. Coal was loaded into 12 lower and 2 upper holds. They were located in the in the outer space near the boiler rooms, and eight coal spare ones, more difficult to access and located between the armor and battery decks, also near the engine rooms. Specifications were revised for weight issue and the final ones planned a 4,000 miles range at a 10-knot cruise speed.

The three cruisers also had steam dynamos, generating a total of 336 kW, for a 105 V current.

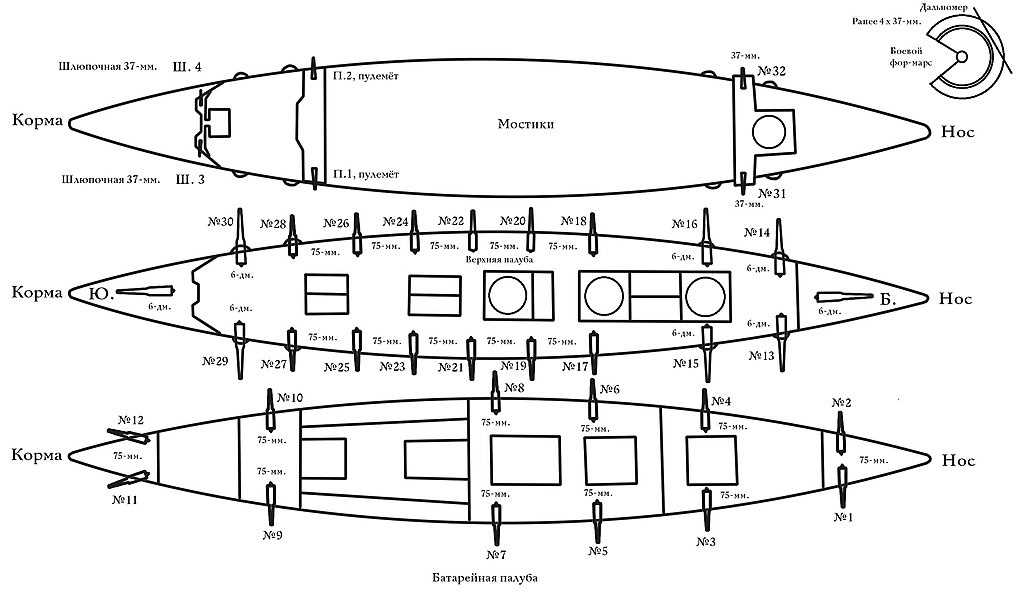

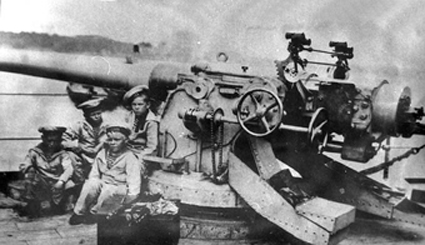

Armament

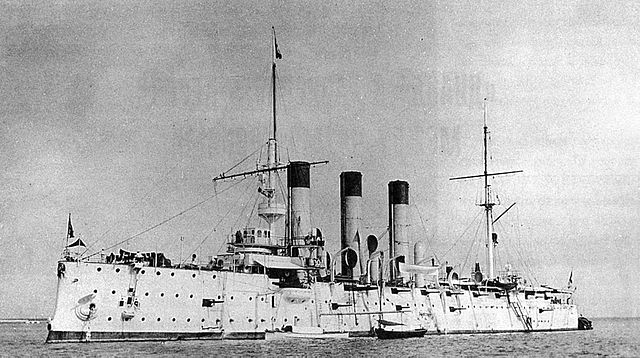

Pallada underway

The artillery according to the final design version consisted only of rapid-firing guns with eight French Canet 152 mm guns (Russified as “Kane”) 45 calibers, all in deck mounts, and twenty-four 75 mm Canet 50 caliber, plus eight single-barreled 37-mm Hotchkiss Revolver guns, also French in design but licenced at Obukhov in Russia, as a byproduct of the recent Russo-French alliance. In addition the ships had two 63.5 mm Baranovsky guns on wheeled carriages for landing parties naval assault.

Artillery fire control provided by the St. Petersburg Electromechanical Plant N.K. Geisler and Co. comprised the two wings telemeters allowing the firing of individual guns or in battery, the ship as a whole.

8x 152 mm/45 Canet

Main: Eight 152 mm 45 caliber Pattern licenced Canet 1892 guns (The best Russian guns at the time).

The main caliber of the ship was placed in deck installations: on the forecastle and poop there were running and retard guns, respectively, six more guns in pairs were on board on sponsons behind the forecastle, in the stern and on the 45th frame. The trio of forward facing guns comprised the axial deck one and two main battery deck side guns behind recesses in semi-enclosed positions.

6-in/45 Canet Specs:

Barrel length: 6858mm/45 caliber

Type: Piston valve Recoil hydraulic system, Unitary loading

Barrel weight with sliding block: 5815-6290Kgs

Projectile weight: 41.4-49.76 kgs

Initial muzzle velocity: 229-793m/s

Rate of fire: 7-10 rpm

Gun mount weight: 14,690 kgs, trunk radius 4823 mm, rollback length 375-457 mm,

Elevation/Traverse: °20, 1.1°s/sec. and traverse 2.3°sec.

Maximum firing range: 11,523-15,910m (20°-25°)

Shield armour thickness: 25 mm

Crew: 10

Secondary: Twenty-four 75-mm Schneider guns.

75-mm guns, which were considered anti-mine caliber, were located side by side on the upper and battery decks, providing shelling across the entire horizon.

The ammunition was stored in the hold under the armored deck in four specially equipped cellars. For 152 mm guns, it was supposed to have 1414 rounds on board, for 75 mm – 6240 rounds, and in the bow cellar there were 3600 rounds for 37 mm guns.

Specs:

Weight: kg 879-910 kg in combat position

Barrel length: mm 3750/75 caliber

Elevation/Traverse -10° to 20° and 360°

rate of fire: 12-15 rpm

Range: shrapnel 8,967 m/40°, HE 9,150m/35° or 6,405 m/13°

Tertiary: Eight 37-mm Hotchkiss cannons. Four were located in the forward fighting top and the remainder four on the bridges’s wings fore and aft.

Quickspecs: Weight, 240 kg in firing position, Barrel length 43.5 mm/47 caliber ROF 15 rpm, sighting range 4.6 km.

Torpedoes: Three 380 mm torpedo tubes.

Standard Whitehead 15″ (381mm) Type “L” on all Russian ships in 1898-1905, carrying an explosive charge of 141 lbs. (64 kg) TNT for a Range/Speed of 980 yards (900 m)/25 knots

or 660 yards (600 m)/29 knots settings. The Pallada class had all three submerged tubes, one forward and two broadside.

At an early stage of design, surface torpedo tubes were included for all future cruisers but by the start of 1897, their installation was called into question, since experience of the Sino-Japanese war showed their danger of detonating during an artillery battle. Thus the design was altered in a timely manner, and kept to just three 381-mm torpedo tubes (the russians still called them “self propelled mines”) with a surface retractable tube in the bow, and two underwater traverse-mounted. The aiming was assured by sights placed in the conning tower.

Total ammunition for the torpedo tubes amounted to eight torpedoes. In addition, the cruisers were supposed to have a 35-chain barrier minefield to be installed at anchor from an aboard mine raft or coaling barge, a solution preferred to the usual nets.

Misc.: Two Baranowski 63.5-mm-L/19 landing guns for land operations.

They were located on deck aft of the mainmast, in between the latter and the wheelhouse, to be hoisted on the steam pinnaces by the main boom crane. There were, as customary at the time, a large provision of rifles, perhaps 200, officers pistols and polearms for the crew, enouygh to mount a sizeable landing party, with the two steam pinnaces forward of the boats, mounting two apparently small pintle guns (perhaps Nordenfelt, the type is unknown). The two Baranowsky guns were also mounted on these and carried on shore for support. These guns weighted 272 kgs with the wheeled undercarriage, Barrel length 19.8 mm (1260 mm overall with undercarriage)/63.5mm caliber, Elevation -10° to 15° ROF 5 shots per minute, Sighting range, approx 4.6 km

Construction of the Pallada class

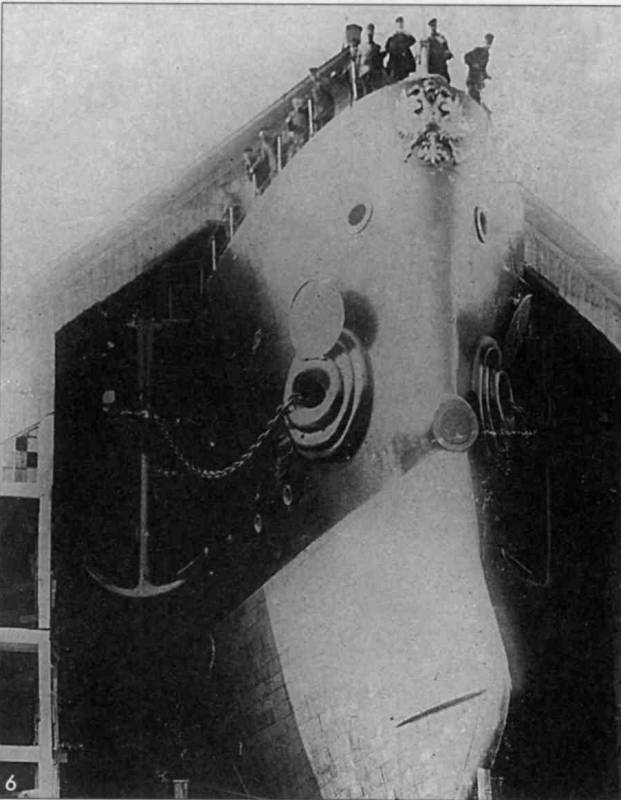

The Prow of Aurora before launch

So as said above the cruisers all built at New Admiralty Shipyard, St Petersburg, Russia, laid down from 1895:

Pallada was the first laid down on December 1, 1895, Launched on August 26, 1899 and Commissioned May 1901, two years before her last sister Aurora. But she suffered like the others of the same shortages which delayed launching by four years and completion by two years (see later). This aspect is crucial to understand their poor reception in the fear east fleet. Technology went ahead and since they were design in 1893, they were now obsolete by 1904.

Diana was laid down on 4 June 1897, launched on 12 October 1899 and commissioned on 23 December 1901, much sooner than Aurora.

Aurora was laid down on 23 May 1897, Launched on 11 May 1900 and Completed on 10 July 1903, so seven years.

Throughout the construction of the Aurora (and otehr ships as a whole, but her in particular), there was a lack of skilled labor at the state-owned shipyards in St. Petersburg. Indeed the latter were already struggling to built in emergency the battleships Borodino, Emperor Alexander III, or Prince Suvorov for example as well as the cruiser Oleg and transport Kamchatka, all for the Pacific fleet. Thus, work progressed very slowly for the Pallada class cruisers.

Tests of watertightness at the aft and bow boiler rooms showed the need to rework fasteners, which also delayed completion work. More serious were delays in manufacture vertical armor for the conning tower by the Izhora plant. The first arrived was reviewed and judge of so poor quality that it was rejected, and the company forced to redo the casting. This also affected the timing. Work on Aurora only in May 1902 and even in the final stage of construction electrical equipment proved faulty and badly installed, showing the immaturity of Russian domestic industrial and manufacturing development.

The anchor system on Aurora, as shown when inspecting battle damage in Manilla where she was interned during the Russo-Japanese war.

At the start of 1902, Hall anchors are installed on the Aurora, which becomes the first Russian cruiser so fitted in the fleet. By May 1902 she is considered completed, and by July 28 ready for her shakedown cruise and maiden voyage to Kronstadt, for further workout. Captain 1st Rank I. V. Sukhotin was accompanied by the Yards specialists and half the crew. During her trabsfer, steering briefly failed when she hit the shore of the channel, slightly damaging the right propeller. But she arrived in Kronstadt and ten days were needed to further prepare the ship for full testing and sea trials. By that time, her whole cost had been evaluated to approximately 6.4 million rubles.

Author’s old illustration

Pallada class specifications |

|

| Dimensions | 107 x 20.4 x 8.4m (351 x 67 ft x 27 ft 7 in) |

| Displacement | 10,206 long tons (10,370 t) standard |

| Crew | 24 +417 |

| Propulsion | 2 shafts TE engines, 12 Cyl. boilers, 9000 ihp |

| Speed | 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph) (16 knots as designed) |

| Range | 3,050 nmi (5,650 km; 3,510 mi) at 10 knots |

| Armament | 4 x 305 (2×2), 8 x 152, 14 x 47 mm, 12 x 37 mm, 6 TT 450 mm |

| Armor | Waterline belt: 12–16 in (305–406 mm), Casemate: 5 in (127 mm), Turrets: 12 in (305 mm), CT: 10 in (254 mm) |

The pallada class in action

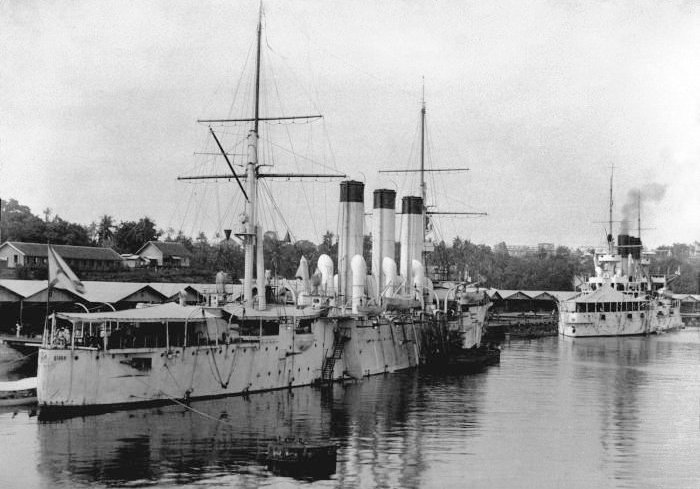

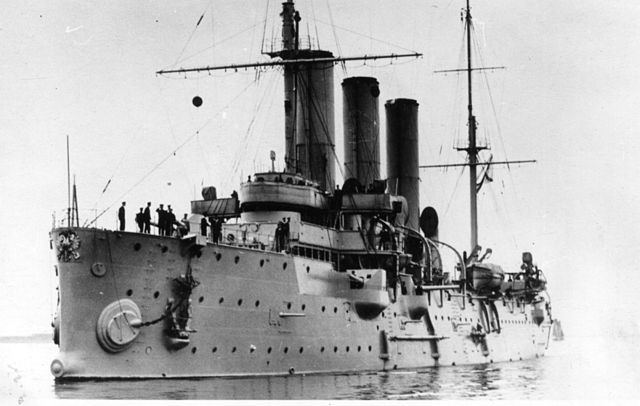

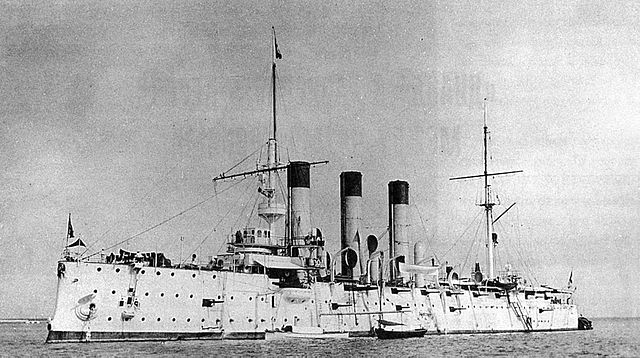

Pallada in Sabang harbor

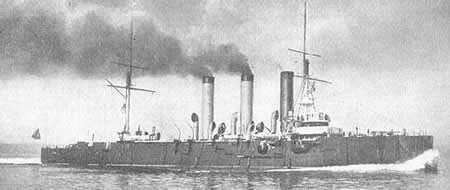

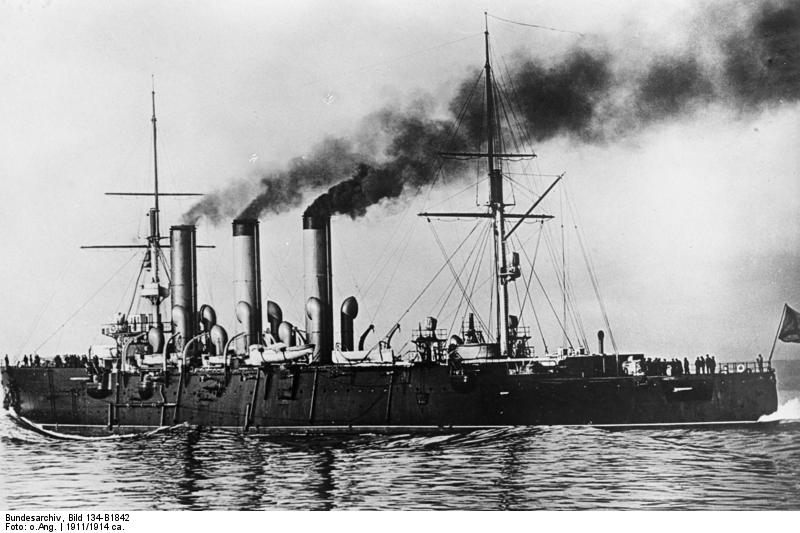

Soon after commission in early 1902, Pallada and Diana were assigned to Port Arthur in the Pacific Squadron and proceded there, joining Aurora practically a few days before the attack on Port Arthur. They took part in the initial actions of the local squadron, with little success. Pallada, blockaded after the last attempted breakout, was destroyed at anchor in Port Arthur by IJA’s heavy howitzers and later relfoated, repaired and integrated as ISN Tusgaru. Diana broke out the blockade successfully, attempted to reach home, but short of coal she was she ended in Saigon, interned until the end of the war. Aurora sailed with the Second Pacific Squadron and nearly escaped destruction at the Battle of Tsushima. She escaped and tok refuge in Manila, Phillipines, also interned.

Both Diana and Aurora returned to the Baltic fleet after the war and during the war served together in the Second Division of cruisers, Baltic Sea, participating in the Battle of the Gulf of Riga in 1916-1917. While she was drydocked in Petrograd, Aurora was taken over by her revolutionary crew and fired the opening shots of the revolutionary war, as a centerpiece of the October Revolution and since preserved as an iconic ship in St Petersburg until today.

Pallada

Pallada

To start with, there was an other Russian cruiser Pallada, launched in 1906. She was an admiral Makaroff ship, built as a replacement for the losses at Port Arthur, the battle of Yellow sea and Tsushima.

The original Pallada was still working out and training when by October 1902-April 1903 she was prepared and sailed with the battleship “Retvizan” and her sister “Diana” to the Far East, and join Pacific Squadron.

Aurora as completed, before and after during her far east trip (she was repainted soon before the war).

Here, Far East Governor, Adjutant General Alekseev, reviewed the ships. In a report sent to the capital, he spoke unflatteringly about the capabilities of both cruisers:

“The cruisers of the 1st rank Diana and Pallada, built at the state-owned shipyard in St. Petersburg, are significantly behind their foreign counterparts in all ways, both in relation to artillery technology, as well as their full completion and work execution and quality. So, for example, back in Kronstadt, the commission indicated that the contractual speed was achieved without the last four boilers, so they are an extra load. Meanwhile, there was no place for a full set of artillery shells, and the ammunition rooms are partly located next to the boilers. Marine qualities are also low, since the ships plows heavily, and full contracted speed is not reached (20 knots). Officers of the Pacific squadron ironically called these “goddesses of domestic invention” and sailors dubbed called them the “Dashka” and “Palashka”.

Pallada, repainted for far east service, before the war. The second photo is from Bundesarchiv.

Nevertheless, Pallada took part in the Russo-Japanese War. On February 8-9, 1904, during the night attack, Pallada is torpedoed by a Japanese destroyer in the outer roadstead of Port Arthur. Towed back into the harbor, repairs commenced and she is only recommissioned by April 1904. She therefore sorties with the squadron and took part in the battle in the Yellow Sea without success, after which returned to Port Arthur, for repairing more damage. On December 8, 1904 while still berthed in the port, the Japanese which had managed to bring their heavy howitzer on the hard-fought batttles of the hills, now covered by direct fire the port, and sank Pallada in the inner harbor.

Nevertheless, Pallada took part in the Russo-Japanese War. On February 8-9, 1904, during the night attack, Pallada is torpedoed by a Japanese destroyer in the outer roadstead of Port Arthur. Towed back into the harbor, repairs commenced and she is only recommissioned by April 1904. She therefore sorties with the squadron and took part in the battle in the Yellow Sea without success, after which returned to Port Arthur, for repairing more damage. On December 8, 1904 while still berthed in the port, the Japanese which had managed to bring their heavy howitzer on the hard-fought batttles of the hills, now covered by direct fire the port, and sank Pallada in the inner harbor.

A sunken Pallada in Port Arthur, pounded by IJA’s 28 cm Howitzers.

In September 1905, she was raised by the Japanese, patched and repaired locally enough to be towed to port. There, probably in Sasebo, she was refitted, put to Japanese standards and recommissioned into the Imperial Japanese Navy as Tsugaru. From 1911, she was used as a training ship as most captured Russian ships. This went on during WWI and she did not left home waters. In 1920, she was converted into a minelayer, and by 1922, she was at last stricken but not sold for BU. Instead, the Japanese had an idea: On May 27, 1924 she was apparently sunk by Japanese naval aviation during a demonstration bombardment, in honor of the anniversary of the Battle of Tsushima. Like Mitchell in the US, some advocates of naval aviation in Japan milited to raise awareness of that kind of warfare to the general staff.

Diana

Diana

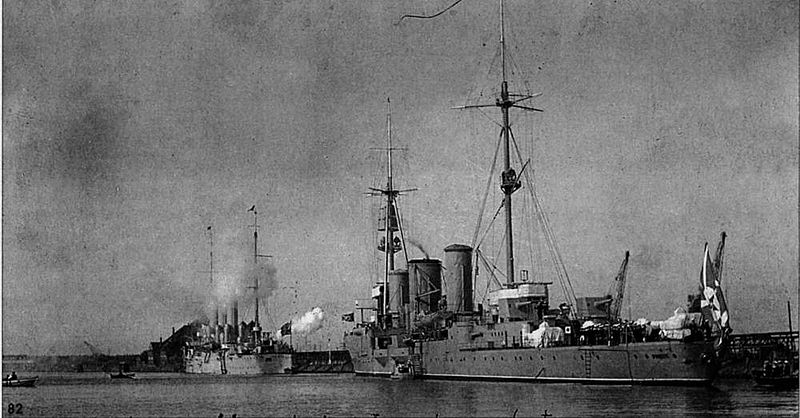

Diana in 1908

Diana was the second of the Pallada class, also built also at the Admiralty Shipyard, St Petersburg. Commissioned on 23 December 1901 like Pallada and Diana, she was assigned to the Russian Pacific Fleet, to be based at Port Arthur. Thus she departed Kronstadt on 17 October 1902. The journey was marred by difficulties between inclement weather, mechanical failures and unexpected heavy coal consumption than originally anticipated. After numerous coaling stops, the ships reached Nagasaki on 8 April 1903 to rendezvous with Askold, and placed at the disposal of Russian envoy A. Pavlov for his negotiations between the governments of Korea and Japan. Basically she was there to show the flag and flex muscles. She reached Port Arthur on 24 April.

During the night attack of the IJN, Diana was damaged near her waterline on the second wave, in the morning of 9 February 1904, by the Admiral Dewa Shigeto “flying squadron” of cruisers. She was able to return into the inner harbor for repairs in a few days, her state being far less critical than her sister Pallada, torpedoed. She fired eight 152 mm and 100 mm shots during the attack, at Admiral Dewa’s cruisers. The Japanese recorded not hit on their side.

In the sortie led by Admiral Stepan Makarov on 13 April 1904, Diana followed illediately the flagship Petropavlovsk, when the latter hit three naval mines, exploded and sank in less a minute. Diana assisted rescuing survivors, and went back to port undamaged.

On 22 April, as the IJA progressed on land, it was decided to strip her of part of her artillery to bolster the defenses of Port Arthur: Two 152 mm guns, four 75 mm guns from the upper deck, and all eight 37 mm Hotchkiss as well as the two 63.5 mm rapid-fire Baranowsky land-carriage cannons were landed from Diana. They were installed in fortifications facing the landward approach to the fortress. Here, a fierce battle developed for weeks on end for the control of the hills.

On 23 June, under command of Admiral Wilgelm Vitgeft, Diana took part in the ill-fated breakthrough attempt of the Japanese blockade. This was repeated on 10 August, with more resolve and desperation, resulting in the Battle of the Yellow Sea. The cruiser squadron was located behind the main battle line, and escaped major damage, but still Diana received several hits, having 10 crewmen killed, 11 wounded, while ordered to stay behind and cover the retreat back to Port Arthur.

Now under command of Admiral Nikolai Reitsenstein, the Russian cruiser squadron attempted to breakthrough along the Japanese lines and rejoin Vladivostok. Diana’s Captain Prince Alexander Lieven however previously disagreed with Admiral Reitsenstein citing the northern port inadequate facilities and coal supplies. Eventually the choice was made instead of a run towards the south, leaving few options but a return back home, if practicable, coaling en route in neutral ports. Accompanied by the destroyer Grozovoi, Diana managed to reach the German naval base at Kiaochou, to receive a supply of coal. Captain Lieven then ordered Grozovoi to Shanghai to be interned with Askold. Meanwhile, Diana was to continued on to Haiphong in French Indochina (and ally) and from there, to Saigon to be interned in more favourable conditions and leniency. It was home the defensive alliance would play in case the IJN showed up. She arrived in Saigon on 23 August but was interned by French authorities, following international neutrality rules.

She stayed there until the end of the war, the crew being allowed to repair the ship and train before departing for the Baltic Fleet after the treaty was signed between Russia and Japan. Back home, she was considered too old to be retained first line and instead converted into an artillery training vessel. Her main armament was back to ten 6-in guns, and she was overhauled between 1912 and 1914, her boilers being replaced by modern ones, her main armament modified with the addition of two modern 130-mm guns.

As World War I start, Diana, freshly out of refit and making a fresher training, was assigned to the Cruiser’s Second Division, Baltic Sea. She famously took part in the Battles of the Gulf of Riga in 1916 and 1917.

By 3 March 1917, her crew joined the February Revolution and to seize control of the ship, killed many officers. By October 1917, she took part in the Battle of Moon Sound. By November 1917, became an hospital ship and departed Helsinki for Kronstadt in January 1918. From May 1918, she was permanently moored there, disarmed. Her guns ended in Astrakhan, mounted on the newly formed “red Caspian Flotilla”. The civil war started and by 1st July 1922, Diana, in poor state, was examined by a soviet commission and it was decied to have her decommissioned and towed to Germany to be scrapped, which was done in Bremen, by late 1922. She was only officially stricken by 21 November 1925.

Aurora

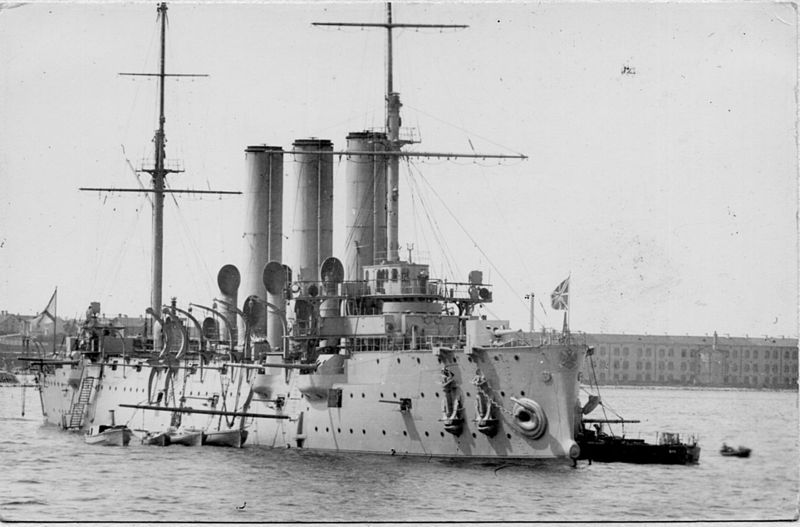

Aurora

Aurora early into service, 1903

Soon after completion, on 10 October 1903, Aurora departed Kronstadt as part of Admiral Virenius’s “reinforcing squadron” for Port Arthur. While in the Red Sea, still en route to Port Arthur, the squadron was recalled back to the Baltic Sea despite protests of Admiral Makarov who specifically requested Admiral Virenius to continue his mission to Port Arthur. Only the seven destroyers of the reinforcing squadron were allowed to continue to the Far East. Upon her arrival back to homeport Aurora was refitted, and afterwards ordered back to Port Arthur as part of the Russian Baltic Fleet.

The Dogger Bank Incident

She, as part of Admiral Oskar Enkvist’s Cruiser Squadron (on Oleg) part of Admiral Zinovy Rozhestvensky’s Baltic Fleet. This force sailed for the Far East, and while underway in the Dogger Banks, some spotters rang the alarm, believing the ships spotted in the fog might be Japanese torpedo boats. A fierce “free for all” started, in which Aurora received five hits, bringing light damage through friendly fire, but killed the ship’s chaplain and a sailor. The Dogger Bank incident was caused in reality by mistaken British trawlers in the area, in the fog, and nearly caused full-out war with Britain, after the diplomatic incident. It was resolved the same way and the fleet continued its journey to the far east and a beleaguered Port Arthur.

Aurora during this long trip led the third echelon also consisting of two destroyers the icebreaker Yermak and transports Anadyr, Kamchatka and Malaya. Before the incident, they passed in front of the island of Bornholm, went rhtough a small storm near the Fakkebierg lighthouse, crossed the Great Belt to Skagen and there, were divided into small detachments, Aurora ending with the 4th detachment (Rear Admiral O. A. Enkvist) behind Dmitry Donskoy and the transport Kamchatka, heading for Tangier. Kamchatka dragged one 17 miles behind.

As for the Dogger bank Incident, the Russians claimed they saw the silhouette of a three-funnel vessel (either a liner or cruiser) in front of their line while in the mist, and moving without distinctive lights on a course crossed the Russian squadron in “gross violation of international rules”. The Russian squadron entered at the same time a fishing flotilla and at 00:55 on Prince Suvorov, illuminating flares were sent around, the officers apparently mistook the trawlers for destroyers and opened fire, followed by the entire detachment of battleships and cruisers, on both sides.

Aurora and Dmitry Donskoy on the left wing also started their lights and opened fire but due to their position being a surprise apparently for some commander, she too, was mistaken for an hostile ship and fired upon. Within a few minutes she took five hits: Three 75-mm and two 47-mm. The hull received minor damage, and the engine room was holed twice, as one of her funnels, her priest (Father Anastasius) was seriously wounded and later died after his arm was torn off by a shrapnell while in tangiers, and other sailors were lightly wounded. The fire stopped at 1:05 a.m., and at 3 o’clock in the morning, the Russsian squadron entered English Channel. The sinking of the Gullsky, and badly damage caused to almost all other trawlers in the vicinity caused a diplomatic incident, and triggered an International Commission of Inquiry.

An harrowing trip to the far east

By October 16, Aurora and Dmitry Donskoy, as well as the transport Kamchatka reached Tangier. They stayed a while to rest, resplenish and recoal, at anchor until October 23, and received ordered to proceed to Dakar and then to the Cape. On November 3 they arrived in the mouth of the Gabon River, loading 1,300 tons of coal on a rate of 71 tons per hour, best of the entire squadron, under unbearable heat. The crew was congratulated later for its efficient and often set as an example by the squadron commander. While rounding the Cape of Good Hope, she took a double supply of fuel, and was later visited by P. Rozhdestvensky which examined what he estimated a very rational placement of coal, which he transmitted to other officers to follow on their ships. Aurora arrived at Great Fish Bay on 23 November and until December 16, the fleet stopped for coaling until reaching French-held Madagascar. They also went trough two storms along the way. By December 8, wind and swells were so strong Aurora rocked and rolled up and down to 30°.

Captain 1st Rank E.R. Egoriev noted that the crew’s discipline was impeccable. Transferred to the Aurora after M. M. Belov was evacuated due to illness, Zgoriev’s adviser V. S. Kravchenko soon wrote in his diary this he was impressed by the crew being “cheerful and obedient” while coal was so aplenty that she could coal sail alone. But its placement was allowed her to keep it even in the storm despite a lot was on the upper deck, battery deck, saloon, quarters, etc.

Organization of leisures during their stay in Madagascar, waiting for the Suez Canal squadron was also exemplary with boat races, semaphore alphabet revisions, aiming and running contests adnd various performances held on the cruiser with both sailors and officers participating. The ship’s theater group even performed on other ships present at Madagascar. The Second Pacific Squadron eventually arrived to meet the First Pacific Squadron and the were prepared for the long final trip to Asia.

On December 21 Aurora and Admiral Nakhimov (RADM O. A. Enkvist) moved to Diego Suarez escorting the coalers. They arrived at Nosy Be to join Admiral D. G. Felkerzam’s detachment, and the squadron rested there, but the cruisers stayed on patrol duty, with a flying squadron comprising Almaz, Aurora and Dmitry Donskoy. Until January 5, 1905, they had difficulties coaling but still Aurora’s crew impressed the fleet by the celerity of it’s crew, setting a new record at 84.8 tons per hour. Midshipman M. L. Bertenson became the new doctor, and Father George the new clergyman aboard.

On January 13, they performed artillery drills in clear and calm weather, and only Aurora was noted for her accuracy and speed. It was less than stellar for the rest pf the fleet.

By March 3, the combined squadron was on marching order, Aurora, sailing together with the auxiliary cruiser Dnepr, in the wake of Cruiser Zhemchugu, right wing of the first armored detachment. The Indian Ocean crossing was difficult with coaling stops made always at sea, difficult and dangerous with the help of cutters and boats.

On March 26, they passed the Malacca Strait and started to prepare for battle.

Aurora at Tsushima

Upon arrival, they were waited for by admiral Togo, which took his dispositions. The battered fleet, with already worn out ships and tired crews went trhough a hellish battle, on 27 and 28 May 1905 The Battle of Tsushima saw Aurora firing left and right against Japanese opponents, taking heavy punishment. Captain 1st rank Evgeny Egoriev died during the engagement as well as 14 crewmen, and many more wounded. Here’s how it happened:

On March 31, the squadron arrived in Cam Ranh Bay and sailed off the coast of the Indochinese Peninsula to leet Rear Admiral N. I. Nebogatov’s force. Oleg and Aurora were detached forward by order of Z. P. Rozhestvensky and on April, 6, Aurora maneuvered with a detachment of battleships. The force went to Phan Phong Bay and on April 26 joined Nebogatov’s detachment. By May 1, 1905, Second Pacific Squadron, reorganized and prepared briefly left Annam for Vladivostok, expecting an encounter mid-way, Aurora being placed at the right outer transport column behind Oleg. On May 10 she made her last recoaling at sea. Later the cruisers Oleg, Aurora, Dmitry Donskoy and Vladimir Monomakh led the third armored detachment, left wing, by May 13, ordered to make ready for battle and the following day entered the strait of Tushima.

At 06:30 it’s IJN Izumi whichi is detected first at the horizon starboard while the fleet moved at 9-knot in two columns. At 11:10, Vice Admiral Deva’s battleship “Eagle” started firing without orders at the cruiser IJNKasagi and the rest of the battleships followed suite, too early to be accurate. The Japanese retreated to draw them on Togo’s main battlefleet. At 11:14 Aurora commenced firing too until signaled “not to fire yet.” At noon, the Russian battleships lined up in one column and started their course, then at 12:30, rearranged in two columns at 9-knot. With the Japanese in sight again, the cruising detachment of Rear Admiral Enkvist, was signalled to veer to the right at full speed, leaving the battleline behind, and act independently to protect the transports.

Izumi approached them and fire first on Vladimir Monomakh but soon Oleg and Aurora supported her, firing at the Japanese cruiser and moved to the starboard side of the transports, to better cover them, until Izumi withdrew.

At 3:00 PM however, Dewa’s 3rd Battle line (Kasagi, Chitose, Otowa, “iytaka) and Uriu’s 4th (Naniwa, Takachiho, Akashi, Tsushim) were called to attack the transports. They approached at 14:30 and commenced firing, Oleg and Aurora turning to starboard to cover the transports at 17-18 knots, and trying to attract and divert enemy fire. They were in a counter-course and at a falling distance but way below the Japanese in terms of firepower, so Rear Admiral Enquist started complex maneuvers to ibcrease the distance and not present broadsides. The battle continued on relatively parallel courses and during the exchange, Aurora received shell fragments from near-hits, receiving damage to the lower winch room, some hull flooding, one 75 mm gun disabled, foremast shattered, conning tower hit, and bow gun crew wounded or killed.

From 14:50, however the two Japanese cruiser lined made their crossfire at a reducing distance, now hammering the Russian cruisers wihth accuracy. Aurora received several direct hits at once, loosing the feed elevator and a steam boat, a 8-in shell penetrated the side joint near the upper deck, disabling two 75-mm guns and started an ammo fire, extinguished by sailors Timerev and Repnikov, then more 6-in hits on her starboard side close to the bow and bridge, the gangway of the forward bridge so she lost control, until retaken in hands by helmsman Tsapkov. Captain 1st rank Egoriev was mortally wounded and soon died by a shrapnell hitting his head, senior navigator K. V. Prokhorov took command, wounded, later replaced by senior officer A. K. Nebolsin.

At 15:35, Suvorov was spotting coming to the rescue byOleg, with Admiral Enquist coming woth the Donskoy and Monomakh, until withdrawing. At circa 4 p.m., all Russian cruisers were caught by the enemy crossfire and Aurora barely avoided an incoming torpedo from one of the cruisers.

She took more hits, mainly in the bow. With the line she started to lean first to the north, then to the east. The cruisers were saved at some point by an incoming column of Russian battleships offering some respite but at 17:30, Aurora was hit in the stern. As darkness fell, she had one officer and nine sailors killed and later many more died of their wounds with eight officers and 74 lower ranks injured, mostly the exposed gun crews.

Combat damage of “Aurora” after the Battle of Tsushima. src

Shortly after sunset, following the battleship Emperator Nikolai I, Nebogatov’s flagship now in command, the squadron fell into complete disorder as torpedo attacks commenced. After 19 hours, Admiral Enquist’s cruiser detachment was now left behind the main forces and disappear from view, the cruiser detachment acting independently. At nightfall they were attacked by Japanese destroyers and the cruisers turned off all the lights, often forced to dodge torpedoes and opening fire only in extreme cases. At 9 PM, Svetlana, Almaz and Donskoy fell behind as well a Monomakh and by 11 PM Oleg and Aurora were also lef behind and separated by Zhemchug, all deciding to go south, and then turn to Vladivostok, having their way blocked by Japanese ships. Admiral Enquist decided to leave the Korea Strait and veer to the southwest and by May 15, the squadron trie to reconstitute its forces, at slower speed, while repairs were ongoing on Aurora, expecting another fight at dawn.

But it never happened. In all, Aurora fired 303 main shell of 152 mm 1,282 of 75 mm and 320 of 37 mm and she conceived 18 hits. Its difficult to assess the damage on IJN ships she was responsible for. Eventually Admiral Enquist decided head for Shanghai to recoal. The headquarters switched to Aurora at noon, and the command flags were mounted later on an impromptu flagpole on the foremast.

Eventually the admiral decided to head instead for Manila, where the coaler Svir was supposed to be, at a 8-knot course.

On May 20, a search detachment entered Sualruen, Philippines, and sailors were sent ashore for reconnaissance. On May 21 Aurora’s captain was buried and salute of seven cannon shots was fired. Some radio communications was re-established and soon they spotted a detachment of ships on the horizon, Lieutenant von Den determining these were two US battleships and three cruisers froml the Manila detachment. A salute was fired with live shells and a few hours later, they were escorted to Manila, dropping anchor. Admirals Enquist appoint a special commission to inspect damage and determine the repair timing given neutraliy laws.

Internment in Manila and back to Russia

26 sailors from the cruisers were treated to an American naval hospital. Contracts the following days were made to repair Aurora, signed with local factories. On May 30, 55 workers, mostly Chinese, started to repair her hull, replacing rivets and repalcing steel sheets. By agreement, 35 of the crew were allowed to go ashore daily, bringing back food. Discipline was observed, and during the long internement, however news fell of the Potemkine uprising. The cruiser experienced a cholera outburst by mid-August and later weathered several tropical typhoons. The American administration wanted the guns put out of action or at least the breech blocks dismounted and sent to shore but this was denied.

Having completed repairs in late August, the Russian cruisers started combat training and daily combat service routine. Aurora was now commande by lieutenants N. I. Ignatiev and V. I. Dmitriev as senior artillery officer and senior navigator.

On August 23, 1905, the Treaty of Portsmouth between Russia and Japan was signed in the United States and so the Russian detachment started preparations to return home. Captain 2nd Rank V. L. Barshch, arrived at the Aurora in September and on the 28th, Zhemchug and Aurora made sea trials. On October 10, they were norified by a USN attaché they were now free of actions. After gathering coal, water and provisions Auroa departed on October 15 in the morning, painted white again. After exchanging salutes and cheers with the US fleet, she left Manila.

Battle damage assessment, November 1905

On September 9, 1905, the surviving ships Tsesarevich, Gromoboi, Rossiya, Bogatyr, Oleg, Aurora, Diana were assembled to Saigon, Diana went solo while Aurora had new staff assigned still as flagship. She stopped in Colombo and by December 21 Aurora and Oleg were in Djibouti. They entered the red sea by 1906 and Aurora left Oleg, having boilers issue behind, goinf back to the Baltic on her own with Admiral Enquist remaining on Oleg. Aurora arrived on January 28, in Algeria, Cherbourg on February 3, the North Sea, and at last by February 19, 1906, Libaya, that she left 458 days ago.

Prewar Operations

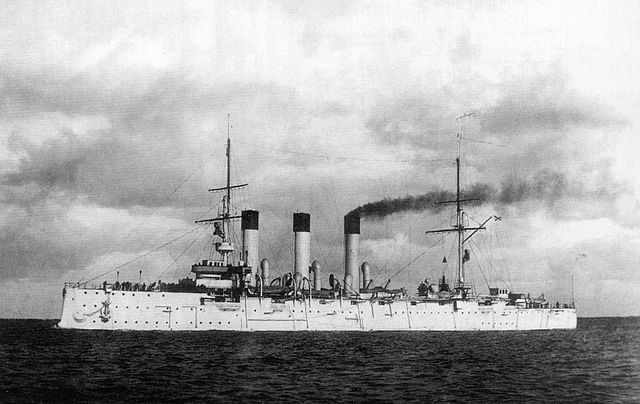

Aurora back in her peacetime white livery between 1909 and 1914. She was painted medium/dark gray in the summer.

In Libaya, Rear Admiral V. V. Lendenstrem reviewed the Aurora and a commission estimated she could be demobilized, 330 of the crew leaving and ship. By March 10, she entered the reserve with a skeleton crew of 157. By May, she was moved to St. Petersburg for repairs, of a month and a half, on the boilers, artillery with the 37-mm guns all removed, two more Maxim machine guns installed on the aft bridge. Three 6-in guns were repaired, six 3-in guns dismantled and replaced. The ship wintered at the Konstantinovsky Dock of Kronstadt for further modifications. She received two Barr and Stroud rangefinders and started for a midshipmen cruise in the summer, visiting several foreign ports. By March 1908, Captain 1st Rank Baron V.N. Ferzen became her new commander. By August 13 she entered a new refit at Baltic Shipyard, and she ended with ten 152-mm and twenty 75-mm guns, all refusbished anew.

After sea trials, and change to Captain 1st Rank P.N. Leskov she was ready for operations by the autumn of 1909, with Diana (flagship) and Bogatyr, which sailed out with midshipmen and by 1910, Aurora stayed in the Mediterranean Sea and at her return took part in the Kiel Week and other events. By November 1910, she retuned in the Mediterranean. By February 1911, she was sent in the 1st reserve cruiser brigade.

By September 21, she went to Siam to participate in the coronation celebrations of the Siamese king, via the Mediterranean.

Leaving Bangkok via Singapore she stayed a while in Batavia and headed for Colombo, Djibouti, Suez and on her way stopped in Falera, was visited by Greek King Nikolai Georgievich. She was also posted at the international squadron off Crete. She was back in the Baltic by July 1912, and spent the winter in Kronstadt.

In 1913 under command of Captain 1st Rank V.A. Kartsov, she trained in the Baltic and underwnt a refit at New Admiralty, becoming later the flagship of the training detachment, making small voyages with cadets. In july she had a new commander, G. I. Butakov, and she was reassigned to the 2nd cruiser brigade (flagship Rossia, Bogatyr, Oleg).

Aurora in the Great War

By July 17, 1914, she was on full alert, make preparations for battle and moved to Revel. She moved to the Gulf of Finland and guardedg the cruiser Magdeburg, recently stranded at Odensholm. Next she moved withe Diana in the Gulf of Bothnia. In winter she was in Helsingfors an prepared for minelaying missions, with rails for 150 impact mines Model 1908. Relocated to Kronstadt, four of Diana’s 6-in guns were installed on Aurora but she kept fourteen 75-mm guns, and eventually had no less than fourteen 152 mm guns and four 75 mm on the upper deck alone.

She spent the summer of 1915 in the Abo-Oland skerry area and in the winter damage her propeller while crossing ice. In Helsingfors she received a 40-mm Vickers AA guns and four 75 mm Canet AA guns. By February 8, 1916, Captain 1st Rank M.I. Nikolsky became her new CO.

The 1916 campaign, saw her only making midshipmen cruises, and she was back in the brihade by July. She was prepared for the operation in the the Gulf of Riga via Moonsund Canal and she took an active part assisting ground forces with artillery fire. She was strafed by German floatplanes, but never hit. On September 6, she was in Kronstadt for a major overhaul completed in April 1917. However the situation changed drastically.

Revolution and Aftermath

After the overhaul started to maintain discipline, Captain Nikolsky established strict restrictions on crew leave ashore and thorough inspections after work. By February 27, 1917, Nikolsky ordered to strengthen the armed guard on the cruiser, now led entirely by officers. “Agitators” and “instigators” were placed under guard on the Aurora during the events. Revolutionary-minded sailors eventually forced their release, insulted the guards and both Nikolsky and the senior officer opened fire on the sailors. He wounded three and reported the event to the headquarters planning to send a hundred Cossacks. While riots took place place in St. Petersburg the situation calmed down.

In the morning, under the watchful eyes of 14 officers, 11 conductors and three midshipmen the crew began cleaning up the premises but groups of workers started to appear in front of the Aurora and demonstration with red flags, ribbons and armbands started, with armed men among the demonstrators. The crowd filled the ship, sailors were hurried ashore and all weapons, including those of officers, were handed out with the workers demanding immediate reprisals against the commander and senior officer on news of the previous firing. The sailors brought them to Taurida Palace, tore off their epaulettes and eventually the senior officer was stabbed in the throat with a bayonet, Nikolsky being forced to carry the red flag, refusing like his now dead fellow officers, and was shot dead. The cruiser was now in the hands of the revolutionaries.

Soon, a ship committee was elected, and its chairman was the artillery Ya. V. Fedyanin, but Bolsheviks were absent of it. By June however 42 members of the RSDLP were imposed. The commander was Lieutenant N.K. Nikonov. Rallies and meetings were held almost daily on Aurora and the crew participated in all events organized by the Bolsheviks. Maintenance ceased.

On July 4, sailors from the Aurora, while at Sadovaya, were machine-gunned by loyal units to the Provisional Government and seven sailors arrested by a commission of inquiry which went on the cruiser. By early September, the ship committee was re-elected, headed by Bolshevik machinist A. V. Belyshev. Repairs waere nearing completion and by October she was scheduled for sea trials. The Bolsheviks however opposed this to have her firepower ready to serve their needs in Petrograd so she stayed on the Neva.

On the night of October 25, the Committee entrusted Aurora to sail to the middle of the Neva and she later took part in the the storming of the Winter Palace.

The Boshevks intended to fire and silence the old Peter and Paul Fortress. She fired blank shots while her radio bradcasted an appeal written by Lenin “To the citizens of Russia!”. At 21:40, she scared out the defenders of the Winter Palace while signalling the assault on the Winter Palace. Afterwards her guns never fired again. She would later completed her repairs.

Interwar

Aurora and Profintern in Swinemunde, 1929

On November 28, 1917, Aurora, tested boilers and machines, and moved to Helsingfors, to join the 2nd cruiser brigade, and later to Kronstadt for the winter. She had another refit at the Admiralty Plant, but by 1918, two attempts were made to sabotage her. By May 9, 1918, she had a crew of 127 left, the rest was on the front. It was planned to flood her in order to block Kronstadt to the International fleet in support of the counter-revolution. This was not done.

Instead she spent her time in drydock at Konstantinovsky, by November-December 1919, and until June 8, 1922, having her artillery removed as well as ammunition, transferred to Kronstadt storage.

By September 1922 she was inspected by a commission which estimated she could only be commissioned as a training ship. She was under command of L. A. Polenov, and replaced the old Komsomolets training ship in early 1923, started her new carrer of training ships of the Baltic Fleet, and becoming the first operational cruiser of the new Soviet Baltic Fleet.

After her last refit she earned ten modern 130-mm/55 guns, two 76 mm Lender AA guns on the aft bridge and four Maxim machine guns. Mine rails were modernized and a new radio and navigation equipment was installed. She made her new sea trials by July 1923, and assisted to combat a fire aboard the battleship “Paris Commune” (Parishizka Kommuna).

She trained routinery ip to the island of Gotland and took part in fleet maneuvers. Later she made a long cruise with the Special Practical Detachment (Aurora and Komsomolets) on the Kronstadt-Arkhangelsk route and back, under tcommand of N. A. Bologov.

She later cruised around Scandinavia in 1925. She had a short refit in 1925-1926 and was upgraded for her firing and several navigational instruments. By late 1926 she visited the Kiel Bay area.

By late 1927, she was awarded the Order of the Red Banner and received a bronze memorial plaque on the bow gun shield to commemorate her role in the revolution after 10 years. She made several foreign voyages and made the first visit of German port for any Soviet warship.

Her last long cruise war around the Scandinavian Peninsula, ending in August 1930. She stayed in the Baltic due to her worn out boilers, having just 1/3 crew. In 1932, tshe was still tested capable of 17.5 knots.

By the autumn of 1933, the naval staff wanted her to underwent a major overhaul, and it was scheduled until 1937, but soon stopped due to other emergencies in the spring of 1935. Boilers were left and so she was reclassified as a non-self-propelled training ship. In the winter of 1935-1936, one boiler room was removed to make space for cadets and she had a new anchor system. She was taken in tow to the Eastern Kronstadt roadstead to train first-year cadets and in winter was in Oranienbaum, handed over to submariners. By it was planned to have her stricken.

Aurora in WW2

In July 1941 with Operatipon Barabrossa starting, her decommission while in Oranienbaum, was not carried out and instead she was included in the Kronstadt air defense system. She received two DP 76.2-mm/55 gun mounts on the forecastle, two AA 76.2-mm on the middle bridge, three SP 45-mm/45 calibers on the aft bridge, and a M-1 system quad Maxim mount. Some authors believe she was also given a B-13 artillery system. She was commanded by 3rd rank Lt. I.A. Sakov, at the head of 260 crew members, mostly AA crews. As the Germans approached Leningrad, Aurora was deprived of her main guns, sent the front.

In July 1941 as “battery A” the cruiser in Duderhof area, so had nine 130-mm guns removed but kept her AA battery. She fell under orders of the commander of the naval defense of Leningrad Rear Admiral K.I. Samoilov which formed two separate two-battery special-purpose artillery battalions and until October, under the Red Banner Baltic Fleet. Sailors crewed her guns when deployed around the city in statioc defence. They put quite a fight during the long siege.

German aviation also started to target Aurora during their raids over the city, starting on September 16. Later German ground artillery was close enough to joi n in and bombard the ship. By September 27-30, she was hit several times, sunk to the bottom in shallow waters while listing 3° to starboard, her AA position still operational. By late November, her remaining crew was transferred to the shore and a small watch of combat-ready anti-aircraft gun crew were left. What left of her artillery was removed while she was pounded daily by German artillery, taking 56 hits. The last of her 130 mm guns ended on the armoured train “Baltiets”.

By August 1943, Aurora again received three more hits but the Germans now assumed she was inoperable and never targeted her again.

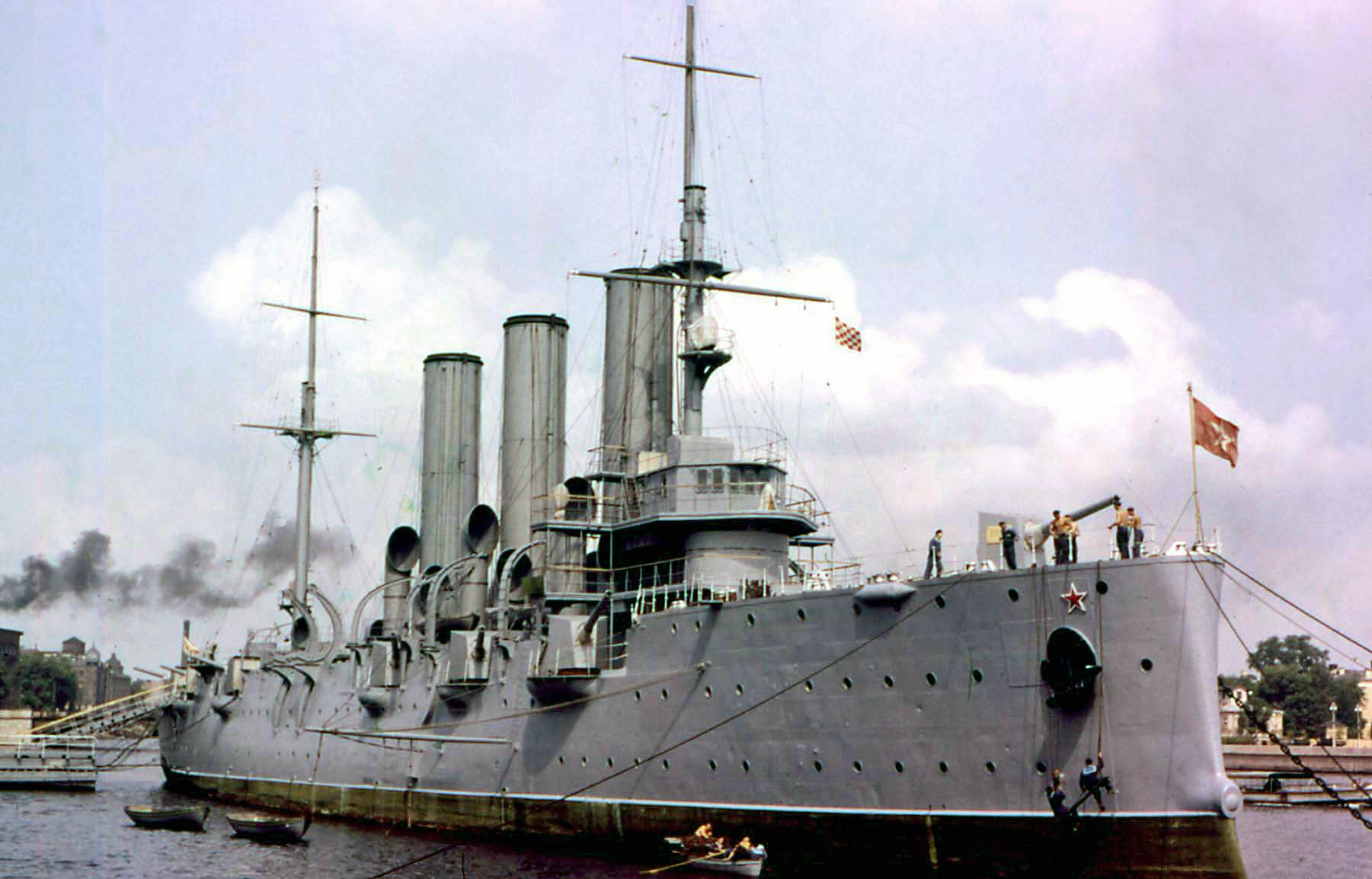

Preservation

Aurora in 1961

In August 1944, Aurora, for all her military and historical significance, was voted for to be installed at Petrogradskaya Embankment as a museum-ship, the first of USSR. It was to be berthed close to the Leningrad Nakhimov Naval School. On July 20, she was raised and under Captain 3rd Rank P. A. Doronin she was transferred to Leningrad. However by May 3 she developed a roll so bad that she had to be semi-submerged again due to a flooding of one engine room. After 20 days, she was raised again and transferred to Kronstadt dock, and after repairs by September she was towed to Leningrad stripped to be re-equipped later. By October she was used for a movie dedicated to the Varyag. She was trabsfomed t look like her in 1946. To stay stable, almost the entire underwater hull was poured with a thin layer of high-grade concrete.

After the movie she was towed to Maslyany Canal to have fourteen 152-mm original Canet uns were re-installedn and four 45-mm guns to fire salutes in pairs on the middle and aft bridges. By November 6, 1947, she took part in festivities under Lieutenant Schmidt Bridge and later moved to Bolshaya Nevka and started wotking for the Leningrad Nakhimov Naval School. The nearby shore museum created was expanded in 1956 as a branch of the Central Naval Museum, largest dedicated to the Russian Navy. In 1960, she entered the list of monuments protected by the state and was written off from the Leningrad Nakhimov Naval School. Awarded the Order of the October Revolution, she was renovated in 1984-1987 for 35 million rubles.

In the 1990s, her interrior was further reequipped, notably with an accurate dental office of the time. On June 6, 2009 during the St. Petersburg Economic Forum, there was a “party on the Aurora”, which nearly damaged the ship.

By December 1, 2010, she was officially stricken from the Navy by order of the Minister of Defense, transferred to the Central Naval Museum. The crew since that time comprises a staff of three military personnel and 28 civilian personnel. By June 27, 2012, deputies of the St. Petersburg Legislative Assembly wanted the President of the Russian Federation to return her status of ship No.1 in the Navy and retaining the military crew and by January 26, 2013, Defence Minister Shoigu, announced she would be refreshed and put even in running condition. The renovation started in 2014, docked at Veleshchinsky, and returned in July 2016 after 840 million rubles spent, and a new exposition for the Central Naval Museum created. Symbolically it’s onboard that the Orthodox ship church, abolished in 1917, was restored and services are now held in her chapel every holidays and weekends.

Read More:

Books

Campbell NJM, Conway’s all the world’ fighting ships 1860-1905

Budzbon, Przemysław Russian section in Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1906–1921.

McLaughlin, Stephen (2019). “In Avrora’s Shadow: The Russian Cruisers of the Diana Class”. Warship 2019

Skvorcov, Aleksiey V. (2015). Cruisers of the First Rank: Avrora, Diana, Pallada. Sandomierz, Poland: Stratus.

Watts, Anthony J. (1990). The Imperial Russian Navy. London: Arms and Armour.

Campbell, N. J. M. (1979). “Russia”. Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1860–1905.

Howarth, Stephen. The Fighting Ships of the Rising Sun: The Drama of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1895–1945.

Jentsura, Hansgeorg. Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869–1945. NIP

McLaughlin, Stephen (2019). “In Avrora’s Shadow: The Russian Cruisers of the Diana Class”. Warship 2019. Osprey Publishing.

Skvorcov, Aleksiey V. (2015). Cruisers of the First Rank: Avrora, Diana, Pallada. Sandomierz

Балакин С.А. Крейсера типа «Диана»: внешние различия и модернизаци 2009.

Бережной С. С. Крейсера и миноносцы: Справочник. — М.: Военное издательство, 2002.

Крестьянинов В. Я. Часть I // Крейсера Российского Императорского флота 1856—1917. 2003.

Лисицын Ф.В. Крейсера Первой мировой. — М.: Яуза, ЭКСМО, 2015.

Ненахов Ю. Ю. Энциклопедия крейсеров 1860—1910. — Минск: Харвест, 2006. — С. 226—228.

Новиков В., Сергеев А. Богини Российского флота. «Аврора», «Диана», «Паллада». — М.: Коллекция; Яуза; ЭКСМО, 2009.

Поленов Л. Л. Крейсер «Аврора». — Л.: Судостроение, 1987. — 264 с.

Скворцов А. В. Крейсеры «Диана», «Паллада», «Аврора». — СПб.: ЛеКо, 2005. — 88 с. — (Стапель Вып. 3).

Скворцов А. В. Крейсера «Диана» и «Паллада» в русско-японскую войну // Судостроение. — 2004. — № 2.

С. Сулига. Японский флот // Корабли Русско – Японской войны 1904-1905 гг. — 1995. — 48 с. — (Арсенал).

Тарас А. Корабли Российского императорского флота 1892—1917 гг. Энциклопедия. — Харвест, 2000

Sites

navsource.narod.ru/

ru.wikipedia.org

http://infoart.udm.ru/

mmt.ru/win/ships/diana/amain.htm

battleships-cruisers.co.uk pallada_class.htm

ru.wikipedia.org diana

ru.wikipedia.org/ aurora

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign