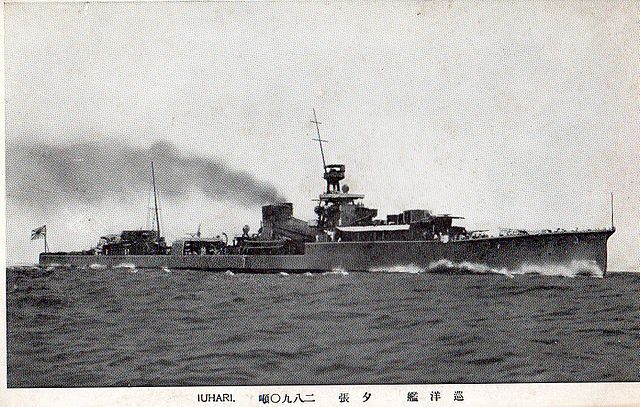

An innovative light cruiser: Hiraga’s IJN Yūbari

IJN Yūbari (夕張) was not only the very first IJN post-WW1 design, but it was an experimental light cruiser whose idea dated back from 1917 and started in 1922, and when she was completed in 1923 for the Imperial Japanese Navy, she marked a large step forward in the nation’s cruiser design. Designed by famous engineer Yuzuru Hiraga, she was largely seen as a test bed for new designs and technologies in a post-Washington Naval-treaty, tonnage restrictive environment. Nevertheless, she was commissioned and had a quite active career in many operations during the Pacific theatre of WW2. Yūbari's designs and innovation would find their way into many future IJN warships, from destroyers to cruisers. During the war, she took part in the most vicious fights in the South Pacific, notably participating in the whole Solomons campaign, from beginning to the end at Rabaul in 1944. She was commanded from 1940 to 1942 by captain Masami Ban, and until 1943 by Taiji Hirai, before in 1944 being handed to Morie

Funaki until 1944 and finally, to Takeo Nara for two months of her life.

Development

The Tenryu on trials, 1919

In 1917, new wartime IJN cruiser designs were primarily meant for scouting, raiding, and escort duties and were well seated on the model of the Tenryū. The previous class, the Chikumas, were merely a prewar design, and the Tenryū was intended to be the blueprint for a whole new series of cruisers ranging from the 1918 to 1919 programmes. This yielded four classes in all, all very similar with up to ten shielded guns, a generous torpedo armament, high speed, and very light protection, as well as onboard aviation. They also doubled as destroyer leaders. However, the last class, the Sendai's, laid down in February 1922, were to end this blueprint for Japanese light cruisers. The admiralty wanted to take a radical departure and explore new possibilities, notably in the general arrangement of the artillery, new protection schemes, better speed, and range, as well as in the implementation of experimental machinery. The 1917 project was to be named initiallyy IJN Ayase.

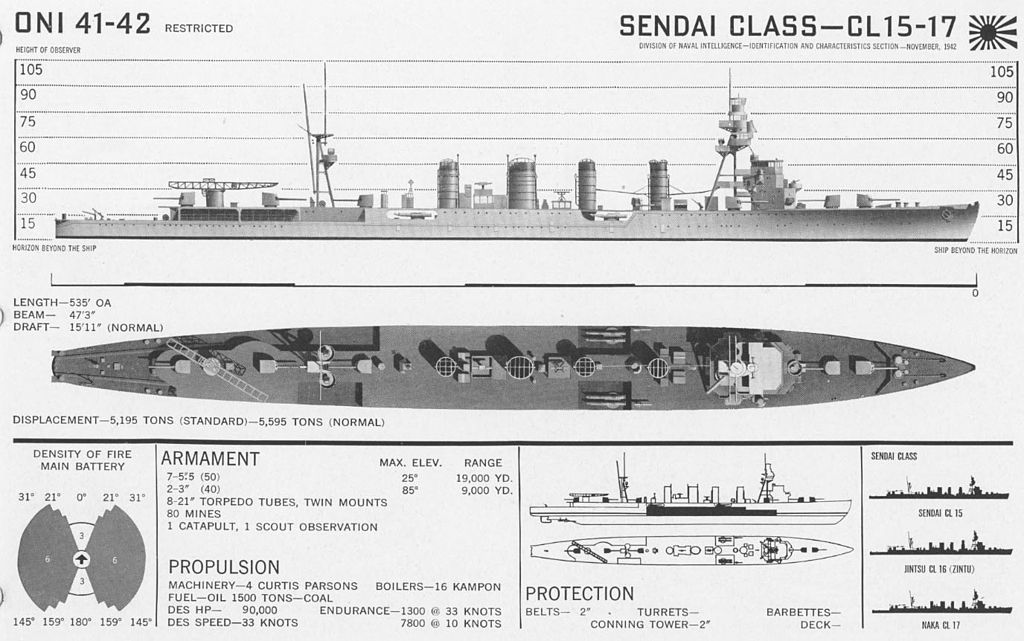

ONI recoignition plate for the IJN Sendai class, built alongside the Yubari and last of the 1917 design generation cruisers.

The experimental light cruiser was authorized under the 1917 8-4 Fleet Program. However funding was not available until 1921. Yūbari was to be a new generation scout cruiser, experimentally combining the same combat potential of the standard 5,000 t Sendai-class with a much lighter displacement. After Japan signed the Washington treaty and its tonnage limitations for cruisers, this made even greater sense. However, the experimental cruiser was a pre-Washington cruiser, tailored for IJN needs.

Captain Yuzuru Hiraga, Japan’s leading naval architect, gathered his team and started working on the blueprints. He was assisted by Lieutenant Commander Kikuo Fujimoto, and presented an innovative, influential design which was well remarked at the time. It laid down the philosophy for cruisers as well as destroyers, of more firepower for less displacement, pushed to the extreme on the Furutaka and Aoba classes, essentially heavy cruisers with a 7,000 tonnes displacement to take advantage of every tonne authorized by the treaty.

Captain Yuzuru Hiraga, Japan’s leading naval architect, gathered his team and started working on the blueprints. He was assisted by Lieutenant Commander Kikuo Fujimoto, and presented an innovative, influential design which was well remarked at the time. It laid down the philosophy for cruisers as well as destroyers, of more firepower for less displacement, pushed to the extreme on the Furutaka and Aoba classes, essentially heavy cruisers with a 7,000 tonnes displacement to take advantage of every tonne authorized by the treaty.

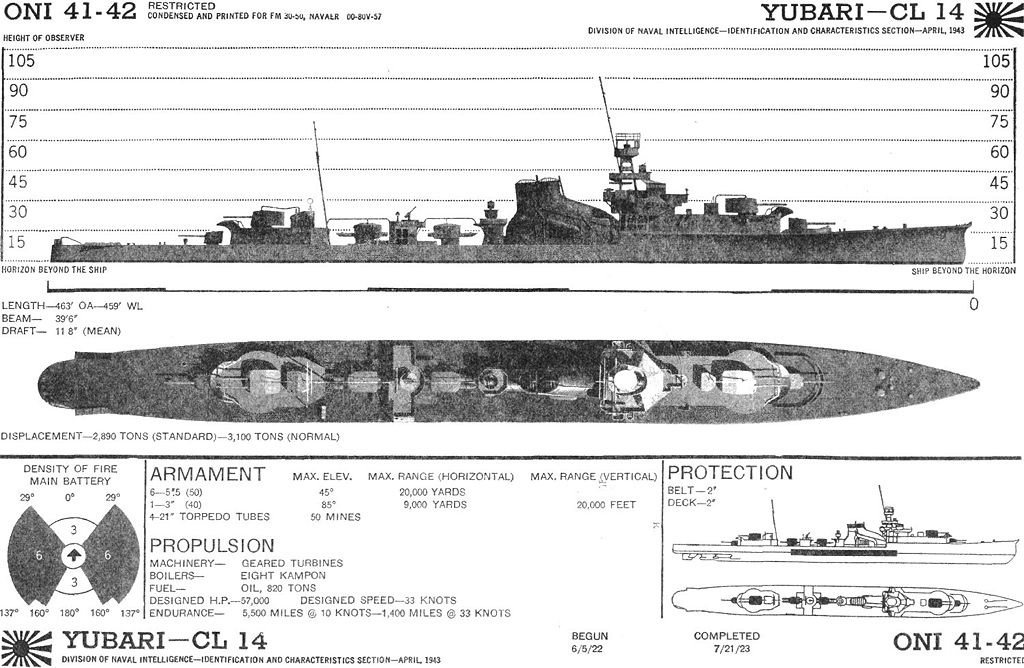

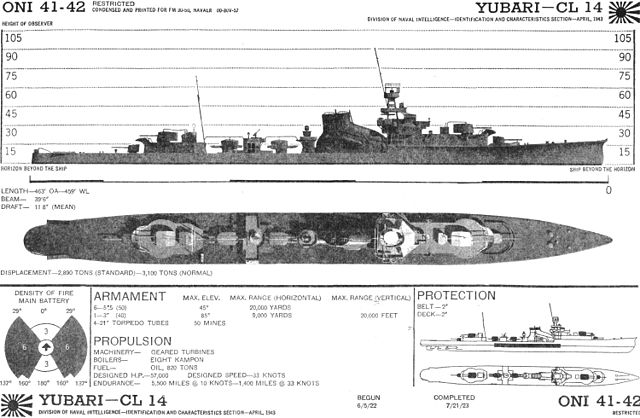

ONI recoignition plates of the USN for the Yubari

Design of the Yūbari

ONI booklet – Yubari for the USN

The basic design concept for the Yūbari was to push forward both speed and firepower, at the expanse of protection but also displacement. Weight saving measures included a drastic reduction of the armor, (which was integrated directly into the hull structure), as well as a high forecastle with significant flare, in order to improve the ship's seakeeping characteristics. With just one truncated funnel, the profile of the new ship was much shorter than preceding classes of Japanese light cruisers and ended with a displacement of 2,890 tonnes, nearly half that of

the Sendai class which was in construction at that time.

Yuzuru Hiraga succeeded in having a ship almost with half the displacement of the Sendai, but with nearly comparable firepower at six 5.5 in (127mm) guns, (Sendai had seven), still half the number of torpedo tubes, at the cost of protection. This was reduced from 2.5 in on the belt down to 2.3 in. Other figures were roughly similar, but both the "structural armour" and intensive use of welding reduced the tonnage. Simple maths showed how profitable it was to build a fleet of these, giving many extra vessels for the same tonnage.

Hull and general characteristics

The IJN Yūbari was a small ship, but not excessively so when compared to many light cruisers of WW2, many of which were of the same format: The hull was 435 feet long between perpendicular, 447 feet 10 inches at the waterline, and 455 feet 8 inches overall. Its ratio was below 1/10 as she made 39 feet 6 inches in beam (versus 46 feet 7 in on the Sendai). The bow remained alike to the Sendai in shape, but the forecastle ended right aft of the main bridge

tower. To even save electrical cabling, batteries, and associated electrical sub-systems, the hull

was pierced for three levels of ports, the lower one just above the waterline, an obvious risk for

flooding. Their framing was welded shut.

Initial weight-saving measures were so extreme that Hiraga thought it possible to target 2,700 tonnes unloaded. That was twice more than most destroyers of the time, but still very light for a cruiser. Eventually, engineers were so fearful of structural weaknesses that some stiffening during completion was necessary, making the ship 13% heavier than originally planned, 419 tonnes more to be exact. This additional weight caused an extra foot of draft, and a 1.5 knots (2.8 km/h; 1.7 mph) speed reduction over the designed speed of 35.5 knots or even 37 as initially planned in 1921. Both very new technologies, unproven sub-systems, and procedures led to many mishaps and issues, becoming apparent once in service. The recognizable truncated smoke stack was too low and thus drafted poorly. After completion and a few months of service, it was revised and enlarged by 1.80 meters in 1924. Stability was also an issue due to the narrowness and lightness of the hull, and additional ballast was added for better stability.

Powerplant

The interesting point about it was that Hiraga essentially scaled up a destroyer powerplant, with three turbine engines fed by eight oil-fired Kampon boilers for a total output as designed of 43,060 kW (57,740 hp). The exhaust pipes were trunked into a single smokestack, which freed up deck space. This was a contrast to previous IJN cruiser designs like the Sendai and its four smokestacks. However this solution was not without its issues: The draft was reduced, causing some overheating in the internals of the ship. Therefore during a refit, the funnel was heightened

and widened.

These three turbo-gear units had a cubic capacity of 19,300 liters and developed some 14.2 Megawatts for 19,250 hp, the power being utilized by three-bladed propellers. These Parsons-type turbines were developed by Mitsubishi under licence and manufactured in Sasebo. The boilers were similar to those used on the Minekaze class destroyers, with the Yubari using double the number.

The layout was also particular: Two power units were in the front and back of the engine room, which was 55 m in length, for a total area of 235 m². Each unit included two main turbines, with an active high pressure one at 3000 rpm, fed by an HP fuel pump, and a lower rate turbine for 2000 rpm used for reverse, but fed by the same high-pressure fuel pump. The transmission used two leading gears rotating a 3.12-m shaft three-bladed propeller at 400 rpm. The reverse turbine used the same housing as the high-pressure one, with no separate cruising turbines. The

two forward cruising gears were turned off at full speed.

Fuel supply comprised 916 tons of fuel oil, stored in the double hull, under the forward lower deck, and on the sides of the first boiler room. This doubled as protection by absorbing potential hull damage. This supply allowed the Yubari to extend her range to 5,000 nautical miles at 14 knots. It was however found in trials, that overheating the boilers to increase top speed for long periods of time massively increased consumption, bringing the ship’s range down to 3,300 miles when fully loaded. This is to compare to the Minekaze class’s range of 3600 miles, making the Yubari useless when acting as destroyer leader.

The eight water tube boilers were of the Kampon Ro Guo type. They integrated an oil heating system according to some sources, and to others, comprised of mixed boilers, installed due to Japan’s fear of oil shortages in case of war. They were located in three boiler rooms, two small ones forward (perhaps the mixed ones), four large ones in the middle section, and two large ones aft. Their working pressure was 18.3 kgf/cm² at 156°C (or 138°C according to other sources). A twin funnel exhaust was used, one for the first four boilers, trunked and connected in a large slope to the almost vertical aft funnel group. This was the idea of Fujimoto, as this would reduce smoke obscuring the bridge, as well as make the silhouette smaller and lighter. However, the draft was insufficient, forcing Fujimoto to rework the funnel shape after commission.

Yubari performed her sea trials on July 5, 1923, off Kosikijima Island, and was tested with an output of 62 336 liters, for a top speed of 34.78 knots as registered. This was less than the designed speed of 35.5 knots, but this was due to Yubari's unanticipated weight. (the ship weighed 3463 tonnes versus 3141 standard as planned.) The steam power was completed by an electrical power unit, a network working at a voltage of 110 V, comprising two 66 KW electric generators, powered in turn by two internal combustion engines located in the engine room.

Armament

The main battery of Yubari consisted of six 14 cm/50 3rd Year Type naval guns, the same as the Sendai, but mounted in a very peculiar arrangement: Two twin gun turrets on superfiring positions fore and aft, and two single gun turrets on the deck. This inversion of weight (the dual turrets higher up were a problem for stability) nevertheless allowed the ship to fire three guns over the bow or stern, with the bonus of the dual turrets having a better field of fire.

Her six 140-mm Type 3 guns were developed before WWI, and adopted by the IJN on April 24, 1914. The No.1 and 4 deck guns had armored shields (similar to those from standard 3500/5500-ton light cruisers). The twin closed turrets (No.2/3, type A (Ko) were initially developed for reconnaissance cruisers (1916 project and 1918 project). And apart from IJN Yubari, they were installed on the IJN Dzingei and Teigai as well as the minelayer IJN Okinoshima. The 50-ton turret measured 5.5 m long, 3.4 m wide and 2.46 m high, and was covered with HT steel plates, at 10 mm in thickness. The electric traverse speed was 4° per second. The elevation speed was 6° per second. Manual aiming backup was provided for an emergency. All six guns were placed on the central axis of the ship but there was little room available for elevation, so they could not be used for AA work and their fire was staggered to avoid causing damage to the superstructure of the ship.

Ammunition for the main guns comprised 38 kg shells with 11 kg bagged charges. They were stored in safe rooms located on the hold deck, at both ends. They were carried upwards by four bucket chain hoists, to the bow forecastle level and aft upper deck. For the single mount deck guns, loading was carried out manually through central supply wells. When Yubari entered service, four types of shells were carried, the “general purpose” ballistic cap half-AP shell alongside standard high-explosive shells, incendiary, and flare-type shells. The maximum firing range at 30° max elevation was 19.1 km.

This was completed by a light artillery battery consisting of a single 8 cm/40 3rd Year Type dual purpose naval gun (AA) and two 7.7 mm machine guns for AA defense. Near the torpedo tubes 76.2 mm/40 type 3 AA guns elevating to 75° were placed, completed by the two 7.7-mm Ryu machine guns. 76-mm shells were stored in the stern underdeck and placed right of the central propeller shaft. Two 47-mm signal guns of the Yamauchi design were located in the front

superstructure.

It seems ludicrously inadequate for WW2 but in 1922, planes were still not considered a threat to ships and were merely ways of doing reconnaissance. Many Type 3 heavy machine guns derived from the Hotchkiss 1914 model for the IJA were carried for supplemental AA defense during wartime. The 7.7-mm Ryu machine guns were located amidships on a raised platform for anti-aircraft defense.

For closer engagement, notably night fighting, IJN Yubari was fitted with two twin torpedo launcher banks placed on the centerline axis, fore and aft of the AA platform like in a destroyer, rather than side mounts like on previous Japanese cruisers. The ship lost half its torpedo capability compared to the latter but gained a 300° traverse and four reserve Type 93 torpedoes. The fire control system was centralized in the bridge, with no redundancy to save weight.

The twin rotary 610-mm torpedo tubes were Type 8 models, similar to those of IJN Nagara and Sendai. Each weighed 8.45 tons and had a length of 8.8 m, and a 3.04 m width. They were powered by a 5 hp electric motor providing a traverse of 20° on either side of the ship and as a backup, the system could be manually turned. Eight torpedoes were carried in all. Each weighed 2,362 tons and carried 346 kg of a trinitrophenol explosive warhead charge. They could be set to a 20,000 m range at 27 knots, 15,000 m at 32 knots, and 10,000 m at 38 knots. Their placement

on the central part of the upper deck allowed spare torpedoes to be easily accessed. Warheads were stored separately in a room located next to the central propeller shaft. However, the torpedoes could not be fired at full speed due to heavy spray. The problem was solved by placing them higher, and giving their operators shields, as could be seen in later pictures of theship.

Control for the main guns was centralized at a Type 13 central aiming visor placed on the tripod mast 23.06 m high. It used a synchronous transmission device based on a WWI British prototype adopted by the IJN in 1916. Its effective range coincided with the main guns at 19 km. Two 2.5 or 3-meter Barr and Stoud rangefinders were also used and were placed on the edges of the compass bridge. For night fighting, two 90-cm powerful light projectors were carried, one

located above the compass bridge, the second behind the funnel. They were put to good use at the battle of Savo Island, illuminating USS Vincennes.

While it is lesser known, Yubari could also be used as a minelayer, carrying Type B mines, the No.1 type, adopted by the IJN on September 2, 1921. They were an improved version of the No.1 Type A used since 1916. They had a cylinder diameter of 0.5 m, a 1.07 m length, and weighed 192 kg with 102 kg of their mass being trinitrophenol. Installed in pairs at the end of a 100-meter steel cable, they detonated on contact. To protect them from the effects of blast gases from the stern main guns, they were covered by a casing, on six parallel mine deck rails.

Protection

The Yubari's armour was the weak point of the design on paper, at least compared to previous classes of Japanese cruisers, notably the Sendai class. IJN Yūbari was given 38 mm (1.50 in) plating for the belt, to protect the powerplant and the gun magazines, as well as 28 mm (1.10 in) for the deck and bridge, though the armour was integrated directly into the structure, thus saving weight and giving the ship overall far better protection than it could have had. The turrets had 25 mm thick frontal plating (0.98 in).

The main armor belt was composed of three rows of NVNC plates with a total length of 58.50 m, about 42% of the hull, reaching up to 4.15 m in height and at their thickest over the powerplant, located inside the hull. Its lower edge was connected to the double bottom edge starting from the keel, and the upper one was connected to the armored deck. The belt had an internal slope of 10° outwards, from top to bottom, which proved to be a poor solution as the

contact angle of incoming shells was close to perpendicular. On subsequent projects, plates were tilted inward. The outer lining of the High Tensile steel was 19 mm. The fuel oil tanks were located in between this internal section and the belt itself. The thick liquid provided an additional buffer against vibrations caused by a shell penetration, but a heavy cal. near-miss could rupture the internal layer.

The upper part of the armor belt was connected to a 25.4 mm armored deck, made of NVNC plates. The part between the belt and outer casing was made of 22 mm thick HT steel plates, and 16 mm plates of the same were additionally attached to the inner section. The lower funnel section and air intakes were protected by a 32 mm NVNC layer, reaching up to 63mm above the armored deck. The superstructure was left unprotected but the turret wells, internal elevators, barbettes, and interphone pipes were covered with HT steel thick enough to deal with shrapnel.

Thus, despite thinner plating across some portions of the ship, the Yubari had a significantly better protection scheme than previous designs. The total armour weight was 349 tons, making 8.5% of the displacement versus 220–238 or 3.4–3.7% on the previous 5500-ton cruisers like the Sendai/Kuma-class and just 176 tonnes or 4.2% on 3500-ton cruisers, making it twice better than the Tenryu class in that respect.

The Yūbari in action

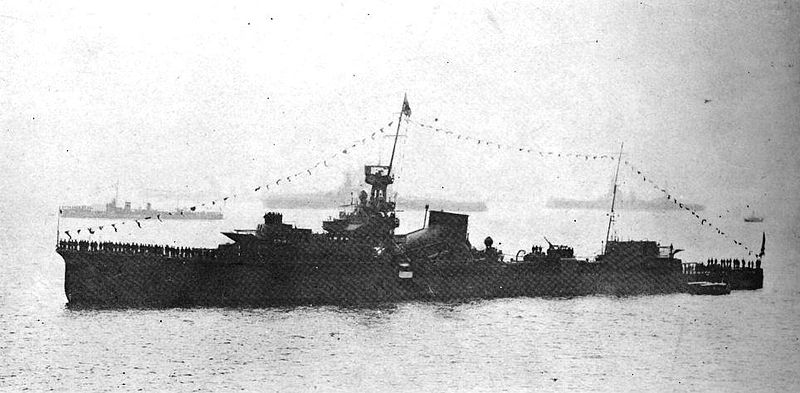

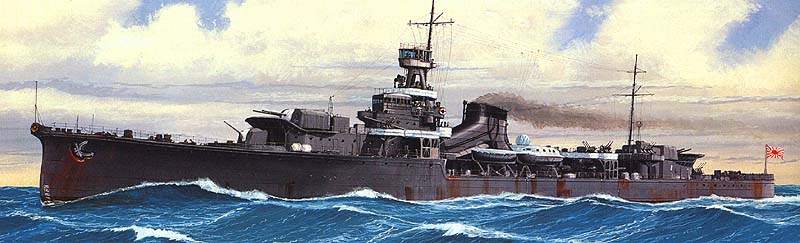

Yubari in sea trials, 1932

Early years: The interwar

IJN Yūbari circa 1932, colorized by Irootoko Jr.

IJN Yūbari was laid down on 5 June 1922 and was launched on 5 March 1923. She was completed at Sasebo NyD, and commissioned on 23 July 1923, just before the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake. She immediately was sent to help evacuate refugees from Yokohama and other stricken cities, and in September 1923 was visited by then Crown Prince Hirohito. In April 1925, she followed US Navy exercises off of Oahu, taking part in an action where she was chased by American destroyers before managing to outrun them, impressing the guests present. Back home, she was sent to the reserves in November 1933.

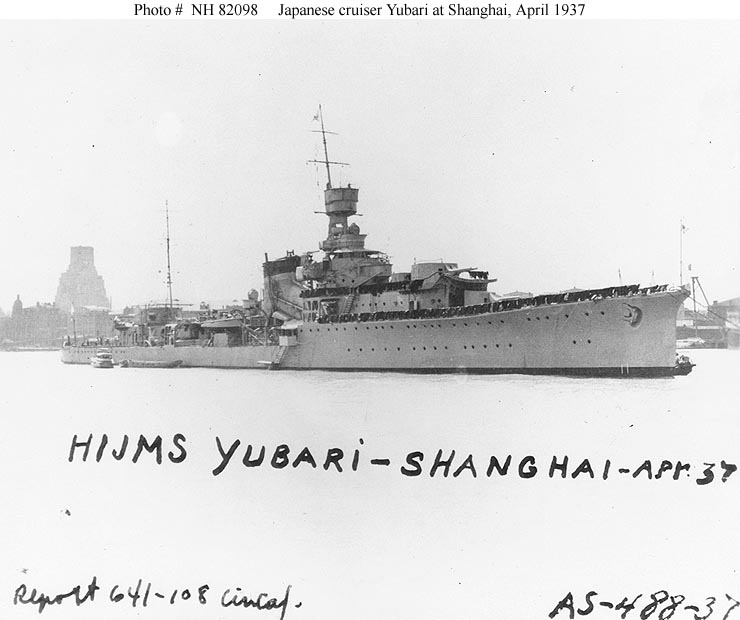

In 1932, the Yubar’s single 76 mm AA gun was removed. In 1935, two twin Type 93 13.2 mm (0.52 in) guns were fitted, long derived from the Hotchkiss M1914. These were replaced in turn by two twin 25 mm guns in 1940. Exactly one year afterward, she left the reserves under Captain Tadashige Daigo’s command. She was assigned to the Yokosuka Naval District, modernized, and refitted the next year. She spent 1935-36 patrolling the Chinese coastal waters, and when the second Sino-Japanese War broke out in August 1937, she helped evacuate Japanese civilians of southern China. She

received her next mission to cover landings of the IJA at Hangzhou on 20 October 1937. Back to Yokosuka, she joined the reserves in December 1937, emerging in March 1939 to be sent to the Ōminato Guard District and to the waters of the Sakhalin Islands, which were contested by the USSR.

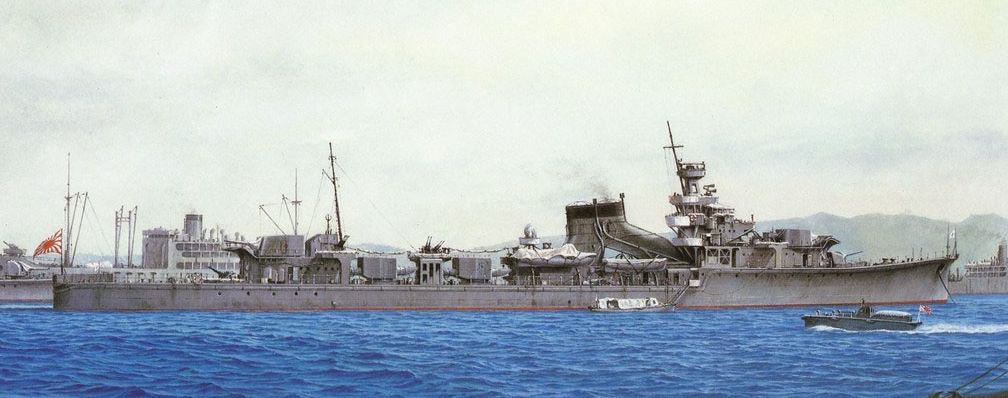

Yubari in Shanghai, 1937 – ONI

Early war

On December 7, 1941, she served as the flagship of the sixth Destroyer Squadron, 4th Fleet. This force was sent to defend the South Pacific Mandate in Truk. In early 1942, Yūbari served as flagship for the Japanese invasion force of Wake Island, coordinating covering fire from the 11th to 23rd of December 1941, and while USMC island gun positions replied, she took no apparent damage.

The Solomons Campaign: Rabaul and Salamaua

Yūbari and her destroyer group then took part in the capture of Rabaul and New Ireland in the Solomon Islands before taking part in the invasion of Salamaua–Lae on 8 March 1942. Two days later two Douglas SBD-3 Dauntless attacked her from USS Lexington. They missed, but they were so close, that Yubari had many KiA among her AA gun crews. Next, she repelled a wave of four Grumman F4F-3 Wildcats from the same force. They strafed her, hitting her bridge and killing multiple of her crew including her executive officer.

The next day at dawn she was attacked this time by SBD-3s from USS Yorktown. The latter managed to hit gunpowder charges stored near the No. 2 turret. This detonated, but the fire was contained by the damage control crew who set protective mattresses around the bridge. A single F4F-3 managed to blow up gasoline drums in her port lifeboat, causing more fires.

Fortunately for the ships, her firefighting teams were good, despite a too short fire hose. The fire started to catch the forward torpedo mount but the captain ordered them fired in an emergency. However, the mount did not move due to an electric malfunction. The crew managed to have them dumped to the sea by using pulleys and ropes while the fire was closing fast, saving the ship.

IJN Yūbari escaped certain destruction, having successfully evaded 67 bombs and 12 torpedoes, only suffering 13 KiA and 49 injured. Later, four USAAF B-17 Flying Fortress that were en route to Rabaul found her and bombed her. She took four near-misses from heavy bombs, blasting her stern with three large gashes. These were patched and the cruiser managed to sail to Truk for repairs until 25 March 1942.

Operation Mo May 1942

When Operation MO started on 4 May 1942, Yubari was again the flagship of the attack force and shelled positions. On 7 May, she was attacked again by a pack of four B-17s, which missed again. She later managed to rescue survivors from the aircraft carrier Shōhō, sunk earlier in the day. She was back in Truk on the 13th of May. She then learned that operation Mo had been cancelled due to the mixed results of the Battle of the Coral Sea. Worn out, she sailed for home, reaching Yokosuka for a short refit and maintenance lasting from 19 May to 19 June 1942 while

her crew rested.

The Solomons Campaign: Guadalcanal

On the 29th of June 1942, IJN Yūbari was part of the force engaged in the Solomon Islands and took part in the whole campaign. She carried personnel on Guadalcanal which would construct an airfield, later captured by US forces and becoming the famous Henderson Airfield. By 17 June however, her chief mechanic signalled that she had many problems with her powerplant. She was forced to never exceed 26 knots (48 km/h; 30 mph) for safety, only using two shafts.

The cruiser nevertheless was deemed fast enough to take part in the Battle of Savo Island which took place on 9 August 1942, where she managed to hit USS Ralph Talbott before she torpedoed and hit the heavy cruiser USS Vincennes, one of the four Allied cruisers sunk in the action. This crippling blow forced USMC forces present to be deprived of their well-needed supplies, as the whole landing force fled the area. They would have to fend off Japanese attacks and their constant reinforcements in the jungle for months.

On 20 August 1842, IJN Yūbari sortied from Truk to patrol up to the Marshall, Gilbert, and Palau islands. She was stationed at Tarawa on the 20th of October 1942. On 20 November she was still there as a guard ship but departed for Yokosuka in late December. She was refitted there, her middle turbine repaired, while the decks received a number of additional much-needed AA guns. She was out once again in February 1943 and sailed for Rabaul. She arrived there on the 1st of April, tasked to the Southwest Area Fleet. On 2 July her destroyer attack group shelled Rendova Island where US Forces tried to consolidate a bridgehead.

While she was sailing off Buin in August 1943, IJN Yūbari struck a mine. Her bow was blasted and the forward hull twisted down with 26 injured. Her speed fell to 22 knots due to the broken and twisted prow, but she managed to make it back to Yokosuka for repairs. This took until October 1943, but she received a complement of anti-aircraft guns. Also for the first time, she received a Type 22 surface search radar plus a Type 94 sonar for ASW warfare.

Back to Rabaul – November-December 1943

She returned to Rabaul on the 3rd of November. A day later, she made it in time to rescue 196 crew and infantry, and even manage to retrieve three field guns from the sinking transport Kiyosumi Maru, managing to stay afloat after the previous day’s air attack. Two days later, she joined the infamous “Tokyo Express” which carried troops and supplies by night to Guadalcanal. She was carrying herself 700 men of the IJA 17th Division plus 25 tons of supplies, but to

Bougainville Island.

On 11 November 1943, IJN Yūbari was attacked and damaged by planes for two carriers during a Raid on Rabaul while at anchor. This happened again on 14 November, but each time she only took splinter damage from near-misses. A week later, she was to be part of another “Tokyo Express” this time to Grove Island (New Britain), which was cancelled after she was badly damaged by a raid of USAAF B-24 Liberators and Seaplanes PBY Catalinas (which could carry

bombs). This forced her to return to Yokosuka on 19 December for long repairs. Like the previous time, the IJA pressed to add more AA batteries, which were installed wherever possible, as this was the main threat for the ship and many others in the IJN by that time.

She had therefore her more significant refit as her two single deck 140 mm (5.5 in)/50 main guns were removed. They were replaced by a single Type 10 4.7 in (120 mm)/45 guns. Also, six twin and one triple Type 96 25-mm AA guns were placed on the deck while a Type 22 search radar was installed on the mainmast, and two depth charge launchers were added on the stern for ASW warfare. Her mine rails were removed and she never performed a wartime mission of

minelaying as far as the records show.

Last operations, March-June 1944

Yubari was back in action, heading for Saipan on 30 March 1944, and departing later for Palau on 25 April. However, she was sighted two days later by the submersible USS Bluegill. The sub’s captain had a lucky spot, as this was his very first war patrol. He fired all six bow torpedoes from a range of 2400 meters. Yūbari’s spotters saw them, and she managed to evade four, but not the last two which hit her starboard side, destroying N°1 boiler room. It was approximately 10:04 AM.

The flooding was so massive that bulkheads could not stop it and the N°2 boiler room was soon flooded also. She lost speed and started to roll to starboard while her bow plunged under. Only her middle boiler room and turbine remained safe, allowing the ship to move on, but soon this failed also. By 10:30, the safety teams worked hard but could not stop the flooding. Even when the destroyer IJN Samidare tried to take her in tow at 16:50 at a 5-knot speed and using anchor chains, they burst after several attempts as Yubari was already too heavily loaded with seawater.

Nevertheless, with many air pockets, she managed to stay afloat almost 24 hours after the torpedo hits. On April 28, at 4:15 AM, water reached the upper deck, and later her captain gave the order to abandon ship. Noon came, and she finally sank at 05°20′N 132°16′E, around 10:15 AM. She lost 19 crewmen, mostly stokers killed during the torpedo hits and those trapped inside by the flooding. However, Yubari was not stricken before 10 June 1944.

HD illustration of the Yubari in 1923 and 1942 by the author, 1/200

Specifications

Displacement 3,315 t. standard -4,447 t. Full Load

Dimensions 139 m long, 12 m wide, 3.6 m draft

Propulsion 3 shaft turbines and 8 boilers, 57,500 hp, 34 knots

Armor: Armored Deck and belt 16-22-25-28 mm, gun shields 11 mm, ammo wells 32 mm

Armament: 6x 140 mm (2×2, 2×1), 1× 76mm/40 AA, 2×2 610 mm TTs, 2x 7.7mm MGs, 34 mines.

Crew: 350

Sources/Read More

WoW’s rendition of IJN Yubari

Conway’s all the worlds fighting ships 1921-1946

Dull, Paul S. (1978). A Battle History of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1941-1945.

Howarth, Stephen (1983). The Fighting Ships of the Rising Sun: The drama of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1895-1945

Jentsura, Hansgeorg (1976). Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869-1945

Lacroix, Eric & Wells II, Linton (1997). Japanese Cruisers of the Pacific War.

Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-311-3.

Roscoe, Theodore (1949). United States Submarine Operations in World War II.

Stille, Mark (2012). Imperial Japanese Navy Light Cruisers 1941-45. Osprey.

Whitley, M.J. (1995). Cruisers of World War Two: An International Encyclopedia.

Lacroix, Japanese Cruisers, p. 307, 794

Bob Hackett, Sander Kingsepp (1997). “JUNYOKAN!”.

Japanese Navy Ships at history.navy.mil.com.

//www.combinedfleet.com/kako.htm

//ww2db.com/ship_spec.php?ship_id=58

//www.fr.naval-encyclopedia.com/2e-guerre-mondiale/nihhon-kaigun.php#crois

Yūbari class Imperial Japanese Navy Page

CombinedFleet.com: IJN Yūbari, history

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Yubari_(ship,_1923)?uselang=de

http://dieselpunks.blogspot.com/2010/07/japanese-cruiser-yubari.html

Models Corner:

Tamiya 1/700 WL series

http://www.aeronautic.dk/Warship%20Yubari.htm

http://www.steelnavy.com/TamiyaYubariSS.htm

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign