Royal Navy (1907) – Bellerophon, Superb, Temeraire

Royal Navy (1907) – Bellerophon, Superb, TemeraireWW1 RN Battleships

HMS Dreadnought | Bellerophon class | St. Vincent class | HMS Neptune | Colossus class | Orion class | King George V | Iron Duke class | HMS Agincourt | HMS Erin | HMS Canada | Queen Elizabeth class | Revenge class | G3 classMajestic class | Centurion class | Canopus class | Formidable class | London class | Duncan class | King Edward VII class | Swiftsure class | Lord Nelson class

Invincible class | Indefatigable class | Lion class | HMS Tiger | Courageous class | Renown class | Admiral class | N3 class

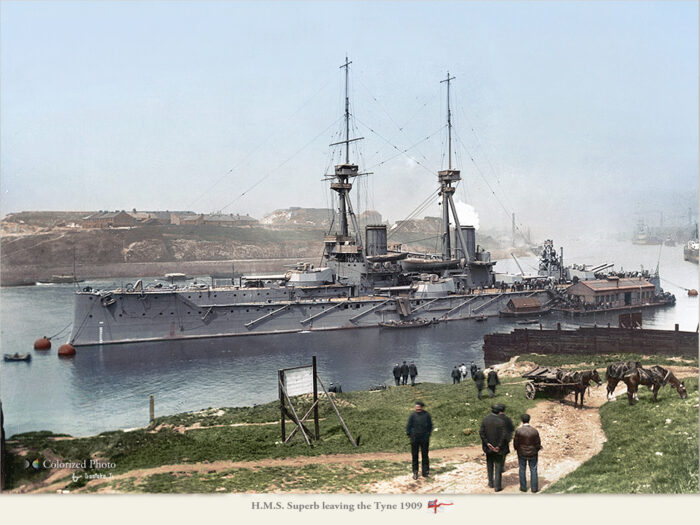

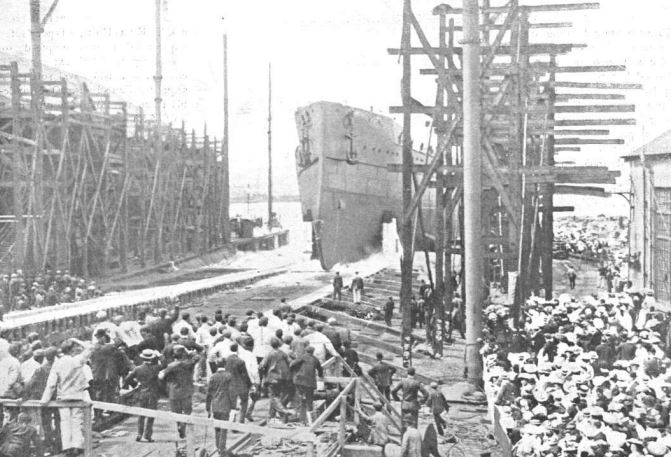

By December 1906, after the famous battleship was launched, 1st lord of the Admiralty sir Jackie Fisher was so confident over the design, that three sister-ships were already ordered respectively on similar plans. They were laid down at Portsmouth for HMS Bellerophon on 6 December 1906 and 1 January, 6 February 1907 for HMS Superb and the Temeraire, respectively, in Elswick and Devonport shipyards. Utterly similar, they however differed by some details, the first striking difference being the masts. They were launched between July and November 1907 and entered service between February and June 1909. All three had their 4-in turret roof guns judged too exposed and relocated in the superstructure.

The masts had their upper extension shortened and they received new radio system and extra AA guns while their torpedo nets were removed as the bow torpedo tube, better projectors installed. In 1918 two turrets were fitted with launching platforms for a Sopwith Pup and Sopwith Strutter. They took part in the battle of Jutland but were discarded in 1921.

Design of the Bellerophon class

Development

The Bellerophon class were direct successors of HMS Dreadnought, the great game changing design of its era, overnight making entire fleets across the world obsolete. Its combination of radical, heavy armament, speed with turbines and superior protection made it on paper superior to any capital ship of the time. For the rest of the admiralty, Fisher’s gamble to rejuvenate the Royal Navy and retake the advantage, also made the entire fleet of battleships that was the spine of the RN, far less relevant, and forced a budgetary increase to then prepare for the inevitable competition on this new design, historians naming later the “dreadnought era”.

1st Admiralty Lord Fisher at the 1907 naval review with the other lords. At a time when stylish facial hairs were proudly sported by anybody, Fisher stands out. He was perhaps the greatest reformer of the RN in a century, reducing naval budgets, modernizing it, selling 90 obsolete and small ships with 64 more pushed into reserve.

The Admiralty’s 1905 draft building plan planned initially four battleships in the 1906–1907 Naval Programme, it was soon cut back by the Liberal government in mid-1906 to three. Admiral Fisher, given his position of 1st sea lord at the time, obtained a repeat of the Dreadnought class, but wanted the new Bellerophon-class to be slightly larger and improved, with better underwater protection and a more powerful secondary armament as key directives. While chairing the Committee on Designs he also produced a derivative at the same time, that became the battlecruiser, and pushed for more studied and trials of submarines. Although retired in 1911, he returned as 1st Lord in 1914, recalled to replace the German-sounding Louis of Battenberg, and he could see in 1915-17 his modernization drive continue under Churchill, with the oil-burning Revenge class, “light battlecruiser” of the Furious class, and the world’s largest aircraft and seaplane carrier fleet.

Launch of Bellerophon in 1907

General Layout and changes compared to HMS Dreadnought

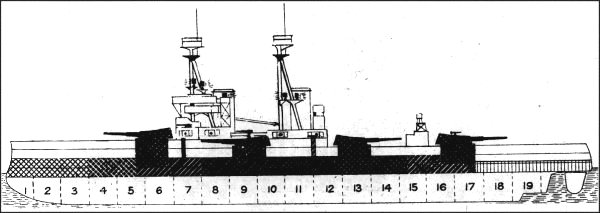

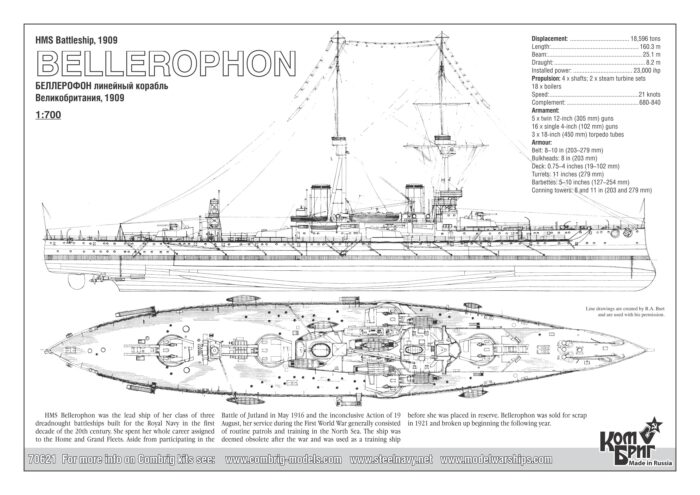

The Bellerophon-class displaced 18,596 long tons (18,894 t) at normal load and 22,211–22,540 long tons (22,567–22,902 t) at deep load versus 18,120 long tons at normal load and 20,730 long tons deeply loaded, so this was a substantial increase.

It was the reflection of greater dimensions overall, with however a similar overall length of 526 feet (160.3 m) versus 527 ft (160.6 m), but a beam of 82 feet 6 inches (25.1 m) verus 82 ft 1 in (25 m) for a normal dr aught of 27 feet (8.2 m) and probably above 30 ft deeply loaded.

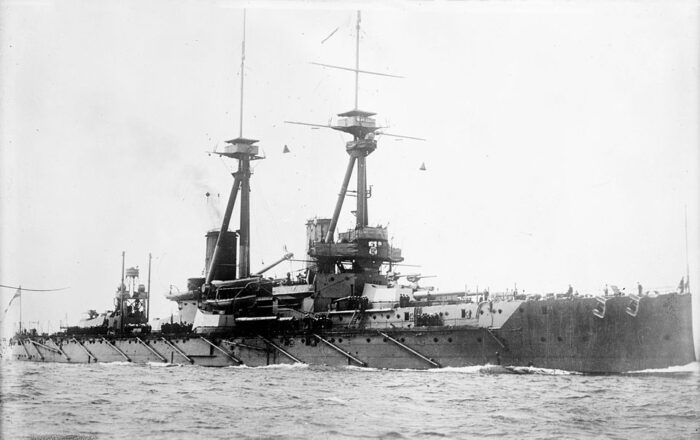

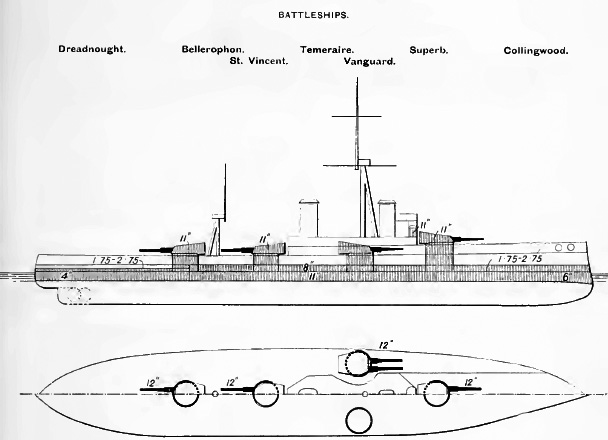

The general outlook remained the same however, with a similar gun arrangement in five twin turrets, two in the wings, two funnels, but the major immediate difference was a couple of tripod masts instead of a single one aft. The second mast was an attempt to improve fire control (more on that later). But the hull was virtually a repeat of the Dreadnought and the minor difference between ships attributed to different yards: Dreadnought was from HM Dockyard, Portsmouth, as Bellerophon, but Temeraire was from HM Dockyard, Devonport and Superb from Armstrong Whitworth, Elswick. Their complement was 680 officers and ratings when completed. With the addition of AA guns, it grew to 840 in 1914 and nearly 900 in 1918.

The main singularity of these ships as stated above was the use of two tripod military masts instead of one indeed, with the foremast being relocated in front of the first funnel to avoid the smoke plume to clog the vision of the forward observer. The second mast was located in front of the second funnel. The other major change was internal, as they received a complete internal protection without loss of speed, complete bulkheads running longitudinally through the ship whereas those of the Dreadnought only protected the magazines. Some sacrifices were done, however, with their belt armour decreased from 11 to 10 inches (254 mm) and reduced coal (therefore range).

Although their main armament was left unchanged in disposition, their secondary 3-in (76mm) QF guns were recognized as too weak to correctly deal with destroyers and replaced by Sixteen 4 in (102 mm) QF guns, which much longer range and twice the impact. This was supplemented with four 6-pdr (47 mm) parade guns, firing white rounds, removed in 1914. A subdivision for better anti-torpedo protection was also added internally.

Powerplant and Performances

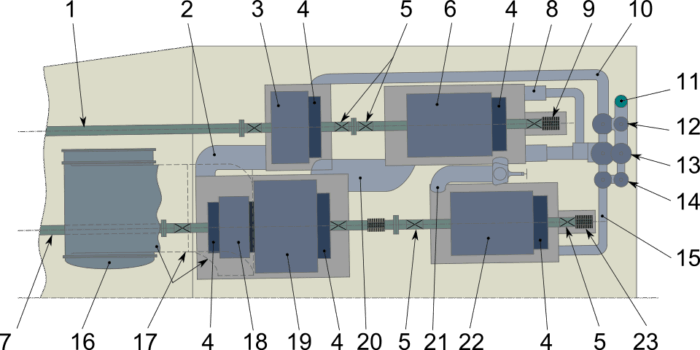

Dreadnought’s arrangement scheme.

The Bellerophon class were powered by two Parsons direct-drive steam turbine sets which activated not one, but two shafts each. They were both housed in their own separate engine room. The outer propeller shafts were coupled to the high-pressure (HE) turbines, in turn exhausted into low-pressure (LP) turbines driving the inner shafts. So they had separate cruising turbines provided for each shaft. This arrangement, a repeat of HMS Dreadnought’s arrangement, enabled to counter the main issue of consumption with steam turbines. They drive the same two 8-foot-10-inch (2.7 m) diameter three-bladed propellers as Dreadnought.

These turbines were fed by eighteen water-tube boilers, like Dreadnought, at a working pressure of 235 psi (1,620 kPa; 17 kgf/cm2) however versus 250 psi (1,724 kPa; 18 kgf/cm2) on Dreadnought. This powerplant was rated at 23,000 shaft horsepower (17,000 kW) total, the same as before however, for the same top speed of 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph). It was still way above the average pre-dreadnought. The Lord Nelson class indeed topped at 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph) only.

Compared to the Dreadnought there had been also a few hull shape refinements, so to allow the larger Bellerophon to match Dreadnought in speed based on the same horsepower rating. On sea trials, they performed well and overmatched their design speed and horsepower. There was a trick, however. To shelve a bit more weight, the armour scheme was modified, and they carried less fuel than Dreadnought at 2,648 long tons (2,690 t) of coal plus 840 long tons (853 t) of fuel oil to boost fire, using sprinklers, versus 2,868 long tons (2,914 t) of coal, and 1,120 long tons (1,140 t) of fuel oil. Final range was thus “only” 5,720 nautical miles (10,590 km; 6,580 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) versus 6,620 nautical miles (12,260 km; 7,620 mi) for Dreadnought. That was significant. For memory, this was enough still to reach the eastern Mediterranean without refuelling, or cross the Atlantic and reach the Gulf of Mexico.

Armour

The main modification here was from Fisher, which insisted on improving the anti-submarine protection, even at the expense of other figures. Thus, for these enlarged anti-torpedo bulkheads, the waterline belt thickness was reduced from 11 to 10 inches (279 to 254 mm).

This waterline belt was made of Krupp cemented armour between ‘A’ and ‘Y’ barbettes. It was tapered down to 6 inches (152 mm) forward, 5 inches (127 mm) aft. Its height was from the middle deck down to 5 feet 2 inches (1.6 m) below the normal waterline, then tapered to 8 inches (203 mm) on the bottom edge, connecting to the armour deck. Above the belt was a strake of 8 inches thick, with a top edge at 8 feet 6 inches (2.6 m) above the waterline.

There was an 8-inch oblique bulkhead connecting the thickest section of the waterline belt and upper armour belts, up to the rear barbette without forward equivalent.

The three centreline barbettes had 9 inches (229 mm) walls above the main deck. Below, it was down to 5 inches (127 mm). The rear barbette however was 9 inches thick all the way down.

The wing barbettes were the same except having outer faces, more exposed, of 10 inches (254 mm).

The gun turrets themselves were protected by 11-inch (279 mm) for their faces and sides. The roof was 3-inch only.

The three armoured decks started at 0.75 inches (19 mm) up to 4 inches when connected to the main waterline belt to create the citadel.

There were two conning towers, forward and aft, with a different protection. The forward CT had a face 11-inch walls forward, thinned down to 8 inches 3 inches at its back.

The aft conning tower was protected by all around 8-inch sides and had a 3-inch roof.

The strongest advantage was their torpedo bulkheads, longitudinal and 0.75 to 3 inches thick, protecting them all the way along the hull between the fore and aft magazines. It was more limited in length for the HMS Dreadnought.

Armament

The general scheme was kept to gain time in design, but the light armament was kept the same at first, but changed upon completion.

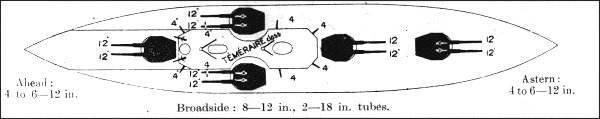

10x 12-inch (305 mm) Mk X

Ten breech-loading (BL) 12-inch (305 mm) Mk X guns, in five twin-gun turrets, three on the centreline, two in wing turrets. Designation ‘A’, ‘X’ and ‘Y’ for the centerline, ‘P’ and ‘Q’ for the wings. Their gun cradles enabled them to depress to −5° and elevate to only +13.5° initially, and were later modified to 16° after 1914.

They fired a 850-pound (390 kg) shell at 2,746 ft/s (837 m/s) muzzle velocity.

Range at +13.5° was 16,500 yd (15,100 m) with armour-piercing (AP) 2 crh shells.

The better shaped 4 crh AP shells at the same were able to fly to 18,850 yd (17,240 m).

Rate of fire was two rounds per minute

There was a reserve of 80 shells per gun, 800 in all.

16x 4-inch (102 mm)

Unlike later dreadnoughts, the Bellerophon, like the St.Vincent that followed stuck to the “monocaliber” mantra, and only had main guns and small defensive armament (plus the usual torpedo tubes) initially. However, it was soon realized the Dreadnought’s 12-pounder (3-inch/76 mm) were deemed barely sufficient to deal with torpedo boats already, so it was decided a more intermediate approach for the Bellerophon would be equipped with sixteen 4-inch (102 mm) guns. That was less still than the twenty-eight on Dreadnought, but these 50-calibre BL 4-inch Mark VII, yet still in unshielded mounts, had a far better range. For a better field of fire they were mounted on the roofs of ‘A’, ‘P’, ‘Q’ and ‘Y’ turrets. Eight remainder were located on single mounts at forecastle-deck level, in the superstructure.

Maximum elevation +15°, range of 11,400 yd (10,424 m).

Shell: 31-pound (14.1 kg) with a muzzle velocity of 2,821 ft/s (860 m/s).

200 rounds per gun in storage.

This was completed by four 3-pounder (1.9 in (47 mm)) saluting guns, only used for parade and reviews, but also capable of firing flares.

Torpedo Tubes

They had three 18-inch (450 mm) submerged torpedo tubes on each broadside and one at the stern, fourteen torpedoes in storage of the Whitehead mark I.

Fire Control

Thre the greatest advantage of the design was to have two tripod masts. There was a foremast on Dreadnought previously positioned behind the forward funnel. The vertical leg was the support for the boat-handling derrick. But still, hot funnel gases could make the spotting top too hot and blind if there was no or little wind. The Bellerophon class had thus their foremast moved forward of the funnels, and a second tripod was added to handle the derrick, positioned forward of the aft funnel, and because of this, it was in turn exposed to the exhaust plumes, from both funnels, under the right wind conditions.

There were control positions for the main armament. They were in the spotting tops at the head of the fore and aft mainmasts. Their 9-foot (2.7 m) Barr and Stroud coincidence rangefinder above each one sent data input into a Dumaresq mechanical computer. The solution was then electrically transmitted to Vickers range clocks in the transmitting station beneath each position on the main deck. There, it was converted into range and deflection data sent to the main turret’s internal display indicators. The data was graphically recorded on a plotting table for the gunnery officer, enabling him to redirect the target’s trajectory. There was also a backup on the ‘A’ and ‘Y’ turrets with their own rangefinders to take over as the main ones were disabled in combat, albeit they sat far lower on the hull.

In May 1910 they received an experimental fire-control director at the forward spotting top. It was evaluated, proving able to electrically provide data to the turrets via pointers to be follow by the crew. The director layer fired the guns simultaneously, aiding in spotting shell splashes, minimising roll effects on dispersion. This director was removed, but Superb had its final production model installed by May 1915. Temeraire and Bellerophon in May 1916, right in time before the battle of Jutland for the first, not the second (still not operational). They also had Mark I Dreyer Fire-control Tables instead from early 1916 at the transmission stations, combining functions of the Dumaresq and range clock.

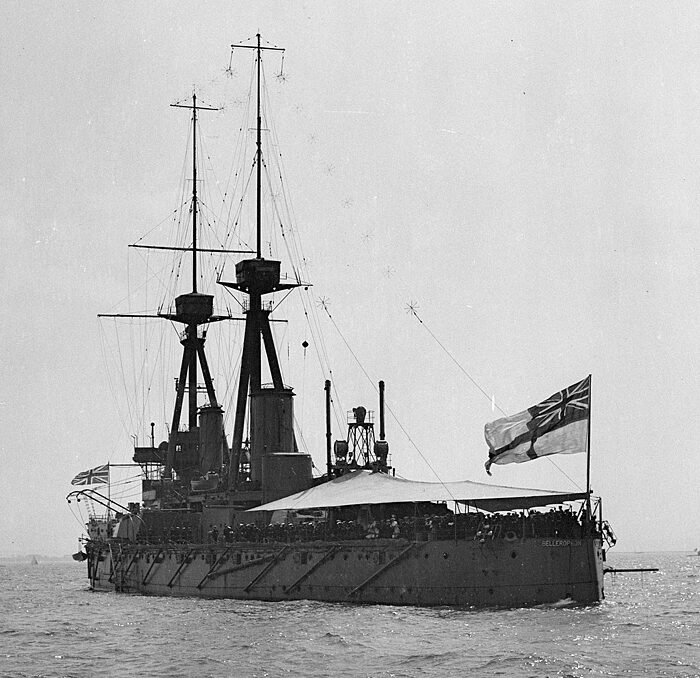

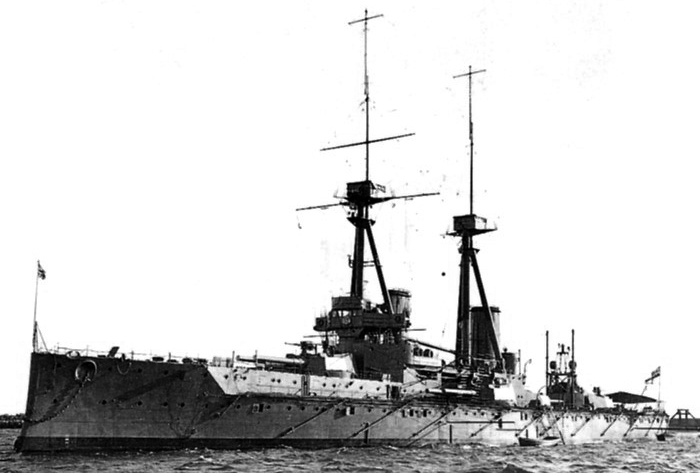

HMS Bellerophon in 1909, old illustration

HMS Bellerophon specifications |

|

| Displacement | 18,596 long tons (18,894 t) normal load |

| Dimensions | 526 ft x 82 ft 6 in x 27 ft (160.3 x 25.1 x 8.2 m) |

| Propulsion | 4× shafts, 2 steam turbine sets, 18× water-tube boilers: 23,000 shp (17,000 kW) |

| Speed | 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph) |

| Range | 5,720 nmi (10,590 km; 6,580 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Armament | 5×2 12-inch (305 mm), 16× 4-inch (102 mm), 3× 18-inch (450 mm) TTs |

| Armour | Belt 8–10 in, Bulkheads 8 in, Deck 4 in, Turrets 11 in, Barbettes 10 in, CT 8-11 in |

| Crew | 680–840 |

Modification, service and evaluation

1913-14: Forward turret roof guns transferred to the superstructure.

1914: Those of the wing turrets are relocated aft of the superstructure.

1915: Stern turret roof guns eliminated (total 12).

1915: 3-inch (76 mm) AA guns added.

1916: +23 long tons (23 t) of additional deck armour added after the Battle of Jutland.

1917: In April, single 4-inch and 3-inch AA guns and stern torpedo tube removed. One 4-inch gun removed from Superb 1917–1918.

1918: High-angle rangefinder fitted on the forward spotting top+ flying-off platforms fore and aft turrets of Bellerophon.

1919: Four 4-inch guns and AA removed from Temeraire, plus accomodations for naval cadets. Same for Superb.

The Bellerophon class was assigned to the 1st Battle Squadron. The first collided with HMS Inflexible, and another with a cargo ship in August 1914. Bellerophon fought at Jutland in May 1916, as well as the Superb and Temeraire. Superb became later flagship of the fleet sent to the Dardanelles for a new large-scale action in November 1918 that was cancelled. Temeraire remained with the Mediterranean until 1918 and later became a training ship. Superb, was placed in reserve became a target ship in 1920, disarmed. She was BU in 1923 and Superb in 1921.

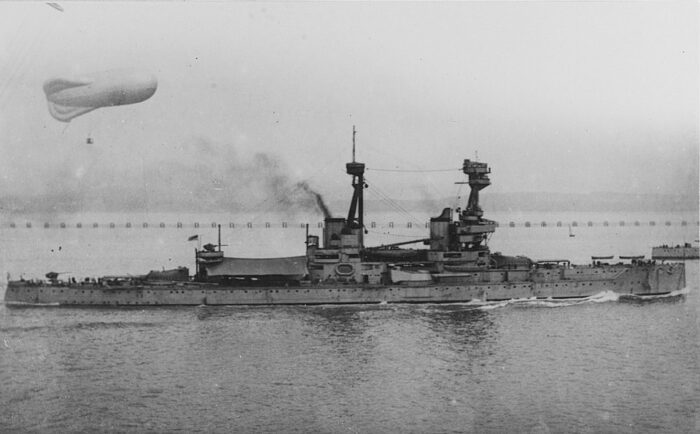

Bellerophon, aerial view, probably 1918, colorized by Irootoko Jr

The Bellerophon class in action

HMS Bellerophon

HMS Bellerophon

Bellerophon in 1911

HMS Bellerophon (after the mythic Greek hero, fourth of her name in the RN) was ordered on 30 October 1906, laid down at HM Dockyard on 3 December 1906, launched on 27 July 1907, completed in February 1909 at a cost of £1,763,491, fully commissioned on 20 February 1909 under command of Hugh Evan-Thomas, Nore Division, Home Fleet (later 1st Division). She took part in the summer combined fleet manoeuvres and review for King Edward VII and Tsar Nicholas II at Cowes on 31 July. She was in the fleet manoeuvres in April and July before Trevylyan Napier took command, followed by a refit in late 1910 at Portsmouth. Bellerophon was sent for combined manoeuvres of the Mediterranean-Atlantic Fleets in January 1911 (collision with Inflexible on 26 May). She was at the Coronation Fleet Review of Spithead on 24 June and refitted later that year. She took part in the Parliamentary Naval Review on 9 July at Spithead and Charles Vaughan-Lee took command on 16 August and Edward Bruen on 18 August 1913 (manoeuvres October 1912, November Mediterranean cruise, visited Athens).

She was reassigned to the 4th Battle Squadron on 10 March 1914.

Furthermore, she was in the test mobilisation/fleet review of 17-20 July 1914 (July Crisis) and was en route for her scheduled refit at Gibraltar on 26 July when recalled to Scapa Flow, colliding with the merchantman SS St Clair off Orkney. In August, as part of the Grand Fleet (Admiral John Jellicoe) she was based at Lough Swilly as Scapa defences were strengthened. On late 22 November, she was part of a first sweep in the southern North Sea in support of VADM David Beatty’s 1st Battlecruiser Squadron. On 16 December, after the raid on Scarborough she sortied but arrived too late. She had target practice off the Hebrides on 24 December and was in another sweep on 25–27 December.

She had conducted gunnery drills on 10–13 January 1915 west of Orkney and Shetland and missed on 24 January the Battle of Dogger Bank (too far, too late). On 7–10 March there was another sweep in the northern North Sea and training manoeuvres, same on 16–19 March. On 11 April this was in the central North Sea and back on 14 April and again on 17–19 April, and gunnery drills on 20–21 April. In May HMS Bellerophon was refitted at Devonport. On 11–14 June she followed the exercises west of Shetland as well as on 11 July. On 2–5 September she was in a sweep on the northern end of the North Sea, then another on 13–15 October, and training west of Orkney on 2–5 November.

Next she was cruising in the North Sea on 26 February 1916. Bad weather cancelled operations in the southern North Sea. Same on 6 March. Again on 25 March, in support for a raid on the German Zeppelin base at Tondern. They arrived too late for action on 26 March in a strong gale. On 21 April she was part of a sweep off Horns Reef as diversion for a minelaying operation in the Baltic Sea, and back to Scapa on 24 April. She sortied too late after the raid on Lowestoft. On 2–4 May, she was in another diversionary sweep of Horns Reef.

On 31 May, the Hochseeflotte and VADM Franz Hipper’s battlecruisers were at sea, reported by Room 40 intercepts. The Grand Fleet (28 dreadnoughts, 9 battlecruisers) sortied the night before to cut off the High Seas Fleet.

On 31 May, Bellerophon was the 14th in the battle line and only fired intermittently on SMS Wiesbaden in the evening. At 19:17 she engaged the battlecruiser SMS Derfflinger scored one hit on her conning tower and destroyed the rangefinder on ‘B’ turret. She then engaged German destroyer flotillas; and these were the last exchanged of the battle. She was not damaged, spent 62 main shells (42 APC, 21 CPC) and 14 4-in HE shells.

She was part of the 18 August sortie to ambush the High Seas Fleet in the southern North Sea, but later the threat of German U-boats reduced activities. The Grand fleet was only to defend against a direct attack of the Hochseeflotte close to home. On 31 August Bruen was relieved by Captain Hugh Watson and on June–September 1917, she became the junior flagship, 4th BS, Rear-Admiral Roger Keyes, then Rear-Admiral Douglas Nicholson when Colossus (flag) was refitted.

Bellerophon in 1918

She was in Scapa Flow when Vanguard’s magazines exploded on 9 July. Captain Vincent Molteno took command on 13 February 1918, and she made a 23 April sortie after an interception of a convoy to Norway. Francis Mitchell took command on 12 October. She was Rosyth as the Hochseeflotte surrendered on 21 November. She became afterwards a gunnery training ship from March 1919 at the Nore, under Captain Humphrey Bowring from 15 March. She was replaced by her sister Superb on 25 September, placed in reserve at Devonport, listed for disposal first on March 1921 then sold from 14 August, purchased on 8 November 1921, resold for BU to a German company by September 1922.

HMS Superb

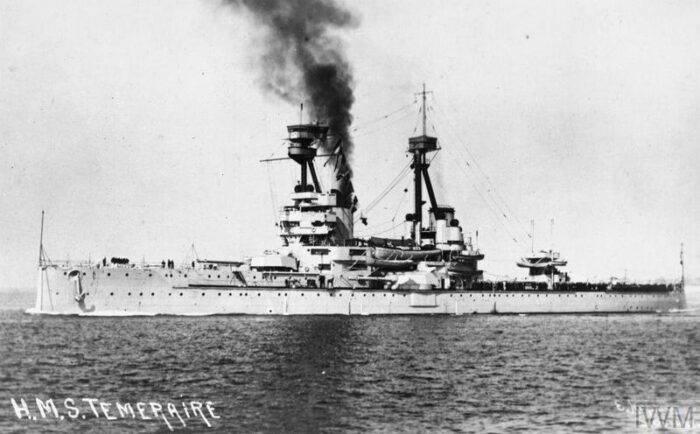

HMS Superb

HMS Superb in 1917

Superb was the 8th ship of her name when ordered on 26 December 1906, laid down at Armstrong Whitworth, Elswick on 6 February 1907, launched on 7 November, completed in May 1909 with a cost estimated between £1,676,529 and £1,641,114 when commissioned on 29 May 1909, assigned to the 1st Division, Home Fleet, with Captain Frederick Tudor in command. Her early career resembled her sisters:

-31 July 1909: Naval review for King Edward VII and Tsar Nicholas II, Cowes Week

-April and July 1909 fleet manoeuvres

-Refit late 1910 at Portsmouth.

-16 August: Captain Herbert Heath took command.

-January 1911; combined exercises for the Mediterranean, Home and Atlantic Fleets

-24 June 1911: Coronation Fleet Review for King George V at Spithead

-22 September 1911: Captain Ernest Gaunt takes command

-9 July 1912: Parliamentary Naval Review at Spithead, manoeuvres in October 1912

-30 April 1913 Captain George Hope takes command.

-July 1913, the squadron visits Cherbourg.

-17-20 July 1914: Test mobilisation and fleet review (July Crisis).

-27 July order to Portland and to Scapa Flow.

-28 July: Captain Price takes command.

-22 October to 3 November, based at Lough Swilly to reinforce the defences of Scapa Flow.

-4-6 November: Price is relieved (ill, will die 5 days later), replaced by Capt. Rudolf Bentinck

-18 January to 10 March 1915: Turbines repaired at Portsmouth, Captain Edmond Hyde Parker takes command

-16 June-September 1915, refit.

-22 November 1915, sweep in the southern North Sea, DS (Distant Support) of the 1st Battlecruiser Squadron, back on 27th

-16 December, sortie after the raid on Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby

-24 December target practice, north Hebrides and sweep in the North Sea until the 27th

-10–13 January 1915 gunnery drills west of Orkney-Shetland.

-23 January sortied in DS for Beatty’s battlecruisers (Battle of Dogger Bank)

-8 February: Captain Allen Hunt took command

-7–10 March, Sweep in the northern North Sea, training.

-16–19 March, same. 11-14 April: sweep in the central North Sea

-17–19 April, same plus gunnery drills off Shetland 20–21th.

-17–19 May/29–31 May: Sweep in the central North Sea

-2–5 September: Sweep in the northern end of the North Sea+ gunnery drills.

-13–15 October: Training exercises before and sweep in the North Sea on.

-2–5 November: Fleet training and gunnery drills west of Orkney

-26 February 1916: Sweep in the North Sea, DS for Ops. of Harwich Force in the Heligoland Bight: Poor weather southern North Sea, sweep in the northern quarter.

-3 March: Hunt is relieved by Captain Edwin Underhill. 6 March, abandoned sweep due to poor weather (escorting destroyers unable to cope).

-25 March, DS for Beatty’s battlecruisers and light forces: Tondern Raid, parred by a gale on 26 March

-21-24 April: Diversionary demonstration off Horns Reef (minefields in the Baltic).

-25 April sweep south of the North Sea, raid on Lowestoft, too late.

-2–4 May, new demonstration off Horns Reef.

-31 May 191 Superb is the 11th ship in the battle line. First stage of the engagement, started firing at 18:26 on SMS Wiesbaden, claiming hits. 19:17, fired seven salvos at SMS Derfflinger, no hits observed. No damage. She spent 54 twelve-inch shells (38 HR, 16 CPC or “common pointed, capped”).

-18 August 1916 sortie to ambush the High Seas Flee in the southern North Sea, aborted and further activity capped by U-Boat activity.

-23 April 1918: Interception sorties, attack on British convoy to Norway.

-October 1918: Temeraire and Superb are transferred to the Mediterranean Fleet, flagship, VADM Sir Somerset Gough-Calthorpe.

-13 November 1918 (Armistice of Mudros): Entered Constantinople.

-14 November, provided a crew for the Russian destroyer Derzky, turned over by the Germans.

-4 December: Conveyed Gough-Calthorpe to Odessa to inspect the situation.

-Late March 1919, visits Port Said, Egypt.

-April 1919: Relieved, sailed for home, reduced to reserve at Sheerness upon her arrival on the 26th

-September 1919: Gunnery TS. until December.

-26 March 1920: Listed for disposal at the Nore.

-December 1920: Used for gunnery experiments.

-May 1922: Used as target ship.

-December 1922: Sold to Stanlee Shipbreaking Co. towed to Dover 7 April 1923, BU.

Painting: Flagship HMS Superb leading the Mediterranean Fleet into Constantinople in November 1918

HMS Temeraire

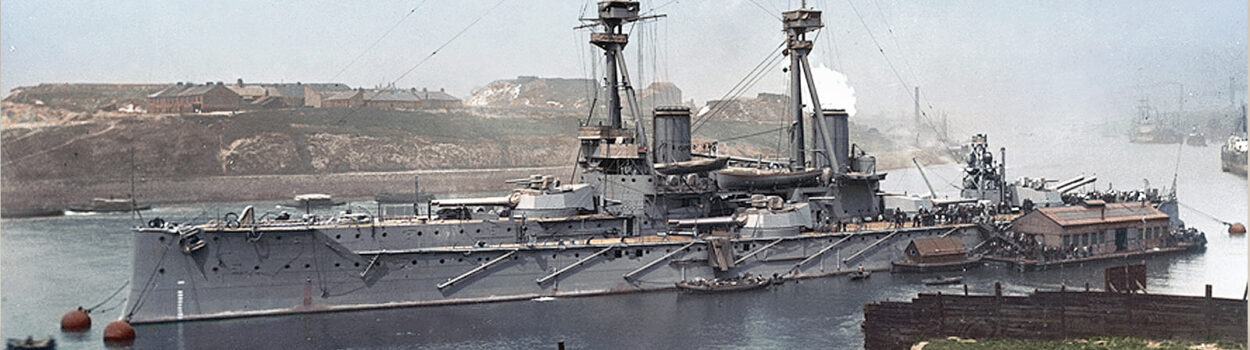

HMS Temeraire

.jpg)

HMS Temeraire

HMS Temeraire was laid down at HM Dockyard Devonport on 1 January 1907, launched on 24 August 1907 and commissioned on 15 May 1909 for £1,744,287. She was the 4th of the name, originally a captured French 74-cannon called “Téméraire”. She took part in a naval review on 31 July 1909 at Spithead, but one of her 4-inch gun accidentally exploded, injuring three men before she was even commissioned on 15 May 1909. Assigned to the 1st Division, Home Fleet under Captain Alexander Duff she took part in fleet manoeuvres in the summer, King Edward VII/Tsar Nicholas II naval review at Cowes Week on 31 July. Capt. Arthur Christian took command on 25 October and the battleship was refitted in 1911 at Devonport as well as the Coronation Fleet Review on 24 June 1911. Christian was relieved by Reginald Allenby on 12 August, and she took part in the Parliamentary Naval Review on 9 July and manoeuvres in October. On 5 April 1913 Captain Cresswell Eyrestook command before she visited Cherbourg in July and back home, Captain Edwyn Alexander-Sinclair took command from 1 September.

On 15 July 1914, she was transferred to the 4th BS and had a mobilisation drill and another fleet review on 17-20 July. From Portland she sailed to Scapa Flow and later as part of the Grand Fleet under John Jellicoe she was displaced at Lough Swilly to fortify the defences at Scapa. Her career resemble that of her two sisters from that point on:

-22 November, sweep in the southern North Sea, DS (Distant Support) of the 1st Battlecruiser Squadron, back on 27th

-16 December, sortie after the raid on Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby

-24 December target practice, north Hebrides and sweep in the North Sea until the 27th

-10–13 January 1915 gunnery drills west of Orkney-Shetland.

-23 January sortied in DS for Beatty’s battlecruisers (Battle of Dogger Bank)

-8 February: Captain Allen Hunt took command

-7–10 March, sweep in the northern North Sea, training.

-16–19 March, same. 11-14 April: sweep in the central North Sea

-17–19 April, same plus gunnery drills off Shetland 20–21th.

-17–19 May/29–31 May: Sweep in the central North Sea

Late May to August: Refit for Temeraire at Devonport

-2–5 September sweep in the northern end of the North Sea+ gunnery drills.

-13–15 October: Training exercises before and sweep in the North Sea on.

-2–5 November: Fleet training and gunnery drills west of Orkney

-26 February 1916: Sweep in the North Sea, DS for Ops. of Harwich Force in the Heligoland Bight: Poor weather southern North Sea, sweep in the northern quarter.

-3 March: Hunt is relieved by Captain Edwin Underhill. 6 March, abandoned sweep due to poor weather (escorting destroyers unable to cope).

-25 March, DS for Beatty’s battlecruisers andr light forces: Tondern Raid, parred by a gale on 26 March

-21-24 April: Diversionary demonstration off Horns Reef (minefields in the Baltic).

-25 April sweep south of the North Sea, raid on Lowestoft, too late.

-2–4 May, new demonstration off Horns Reef.

31 May – 1st June: Battle of Jutland: Temeraire is the 15th ship in line. Fired five salvos crippled SMS Wiesbaden with 3 hits at 18:34. 19:17, fired seven salvos at SMS Derfflinger, no hits. 19:27, engaged destroyer flotillas, no hits. No damage, fired 72 main HE shells, 50 shells 4-in HE shells.

-18 August 1916 sortie to ambush the High Seas Flee in the southern North Sea, aborted and further activity capped by U-Boat activity.

-23 April 1918: Interception sorties, attack on British convoy to Norway.

-October 1918: Temeraire and Superb are transferred to the Mediterranean Fleet under Vice-Admiral Sir Somerset Gough-Calthorpe and on

-13 November 1918 (Armistice of Mudros): Entered Constantinople.

-13 December: Temeraire asked to provide a crew for the Russian destroyer Schastlivy turned over to the Allies after the Armistice.

-13 February 1919: Captain Francis Caulfeild take command, she remained in the Black Sea

-3 April, departs for home after stopping at Sevastopol and Haifa. Arrived the 23th, examined at Devonport.

-September 1919: Recommissioned as cadet TS.

-8 October: 1st training cruise in the Mediterranean, back to Portsmouth.

-11 April 1921, decomm. at Rosyth, listed for disposal, sold to Stanlee Shipbreaking & Salvage Co. late 1921, BU February 1922.

HMS Temeraire in the Mediterranean, 1918

Gallery (WoW)

Sources

Books

Preston, Antony (1985). Gray, Randal (ed.) Conway’s all the world fighting ships 1906-1921.

Brooks, John (2005). Dreadnought Gunnery and the Battle of Jutland: The Question of Fire Control. Routledge.

Burt, R. A. (1986). British Battleships of World War One. NIP

Campbell, N. J. M. (1986). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. NIP

Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One: Guns, Torpedoes, Mines and ASW Weapons of All Nations. Seaforth Publishing.

Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. NIP

Jellicoe, John (1919). The Grand Fleet, 1914–1916: Its Creation, Development, and Work. George H. Doran Co.

Konstam, Angus (2013). British Battleships 1914-18 (1): The Early Dreadnoughts. New Vanguard. Vol. 200. Botley. Osprey.

Massie, Robert K. (2003). Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea. Random House.

Monograph No. 12: The Action of Dogger Bank–24th January 1915 (PDF). Naval Staff Monographs (Historical). Vol. III.

Monograph No. 35: Home Waters-Part IX 1st May, 1917, to 31st July, 1917 (PDF). Naval Staff Monographs (Historical). Vol. XIX.

Newbolt, Henry (1996) [1931]. Naval Operations. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents. Vol. V. Battery Press.

Parkes, Oscar (1990) [1966]. British Battleships, Warrior 1860 to Vanguard 1950: A History of Design, Construction, and Armament.

Preston, Antony (1972). Battleships of World War I: An Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Battleships of All Nations 1914–1918. Galahad Books.

Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World’s Capital Ships. Hippocrene Books.

Tarrant, V. E. (1999) [1995]. Jutland: The German Perspective: A New View of the Great Battle, 31 May 1916. Brockhampton Press.

Links

https://www.jutlandcrewlists.org/bellerophon

https://www.maritimequest.com/warship_directory/great_britain/pages/battleships/hms_bellerophon_1907.htm

Bellerophon class battleships on wikipedia

On dreadnoughtproject.org

on blog.livedoor.jp irotoko colorized photos

_leading_the_fleet.jpg)

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign