The Roots of local naval rivalry

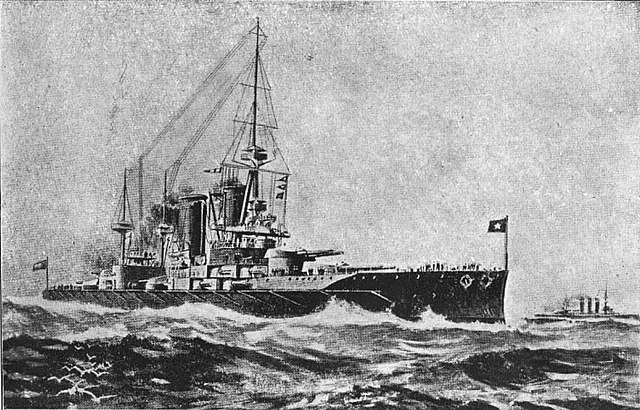

Last of the “dreadnought race”: Chile’s Latorre class – Third naval power of South America, Chile at some point in 1890 possessed certainly the largest and most powerful navy of the continent, before the Argentines ordered four brand-new armoured cruisers in Italy (The Garibaldi class). The 1902 tripartite agreement (“Pactos de Mayo”), sanctioned by UK, ended the Chilean-Argentine naval arms race, ongoing since 1880. Soon after, Brazil in 1907 revealed to the world she has took the very bold step of ordering two dreadnoughts in UK.

After the Minas Geraes class was out, threatening the very existence of both the Argentine or Chilean navies, Argentina counter-attacked with the order in 1910 of two larger dreadnoughts in US shipyards, the Rivadavia class.

Relaunch of the naval race

The Chilean government took the measure of the threat as her only active “battleship” at this point was the French-built 1889 Capitán Prat, an ironclad from a by-gone era, demilitarized by treaty since 1902. The main concern was more the building of the Rivadavia class in relation to the Argentine–Chilean boundary dispute. This was a complicated situation as despite both nations ordered many ships in British yards, the British government had extensive commercial interests in the area.

In 1902, the other strong gesture was to purchase the two Chilean battleships in construction. Now with the Argentines stepping out of the treaty, Chile wanted to respond in February 1906 already. Naval plans however were delayed by a major earthquake in 1906 and a financial depression in 1907, which impacted also greatly the nitrate market, the Chilean economy was linked to.

Order and bidding process (1910-1912)

On 6 July 1910, the National Congress of Chile passed a bill, allocating £400,000 pounds sterling for six destroyers, two submarines, and two large battleships.

Their names were chosen in a naval commission and submitted later to approval, Almirante Latorre and Almirante Cochrane. The United Kingdom was certainly the most certainly sure to be chosen due to its unique bonds with the Chilean Navy. The long-standing close relationship existed since the 1830s. Chilean naval officers were trained on British ships and a local academy was literally created by the Royal Navy. The relation was much stronger than the Anglo-Japanese alliance. Of course this privileged relation has one underpinning reason: Nitrate, used notably for explosives the Royal Navy depended upon. This was translated in 1911 by a British naval mission requested by Chile.

When the order was known, the United States actively advocated for their own shipyard order, sending Henry Prather Fletcher in Chile in September 1910. He had previously implemented President William Howard Taft’s “Dollar Diplomacy” in China but in Chile her met resistance, perhaps fuelled by the 1891 Baltimore Crisis, a sentiment confirmed The US naval attaché; The Chilean bidding process specifications were indeed mirroring the latest armament and armor of British battleships. However after pressuring the commission, Fletcher obtained an extension to the bidding process to allow US shipyards to participate;

Meanwhile, the Germans ably sent the battlecruiser Von der Tann on a South American cruise, “widely advertised as the fastest and most powerful warship afloat”. US and British shipyards, not to be undone, started to sent ships of their own. The USS Delaware on a ten-week excursion to Brazil and Chile with the pretext of carrying back the deceased Chilean minister Anibal Cruz, while the British sent an armored cruiser squadron. During her stay in Chile, USS Delaware was fully opened to Chileans personal except sensitive data about the new fire-control system, and Fletcher announced soon after the willingness to provide a $25 million loan to support the purchase. But this came to nil.

The final decision eliminated Germany, and eventually securing a loan from the Rothchilds, awarded one order to Armstrong Whitworth on 25 July 1911. The design was prepared by J.R. Perret, the same pen that draw the Rio de Janeiro. The US arenals still pushed to place a contract for the main guns, their 14-inch/50 caliber guns, but the Chilean Navy only ordered them for coastal batteries. A second dreadnought was ordered in June 1912, assorted by Six Almirante Lynch-class destroyers to J. Samuel White. The official order was published on 2 November 1911.

Development & construction of the Latorre class

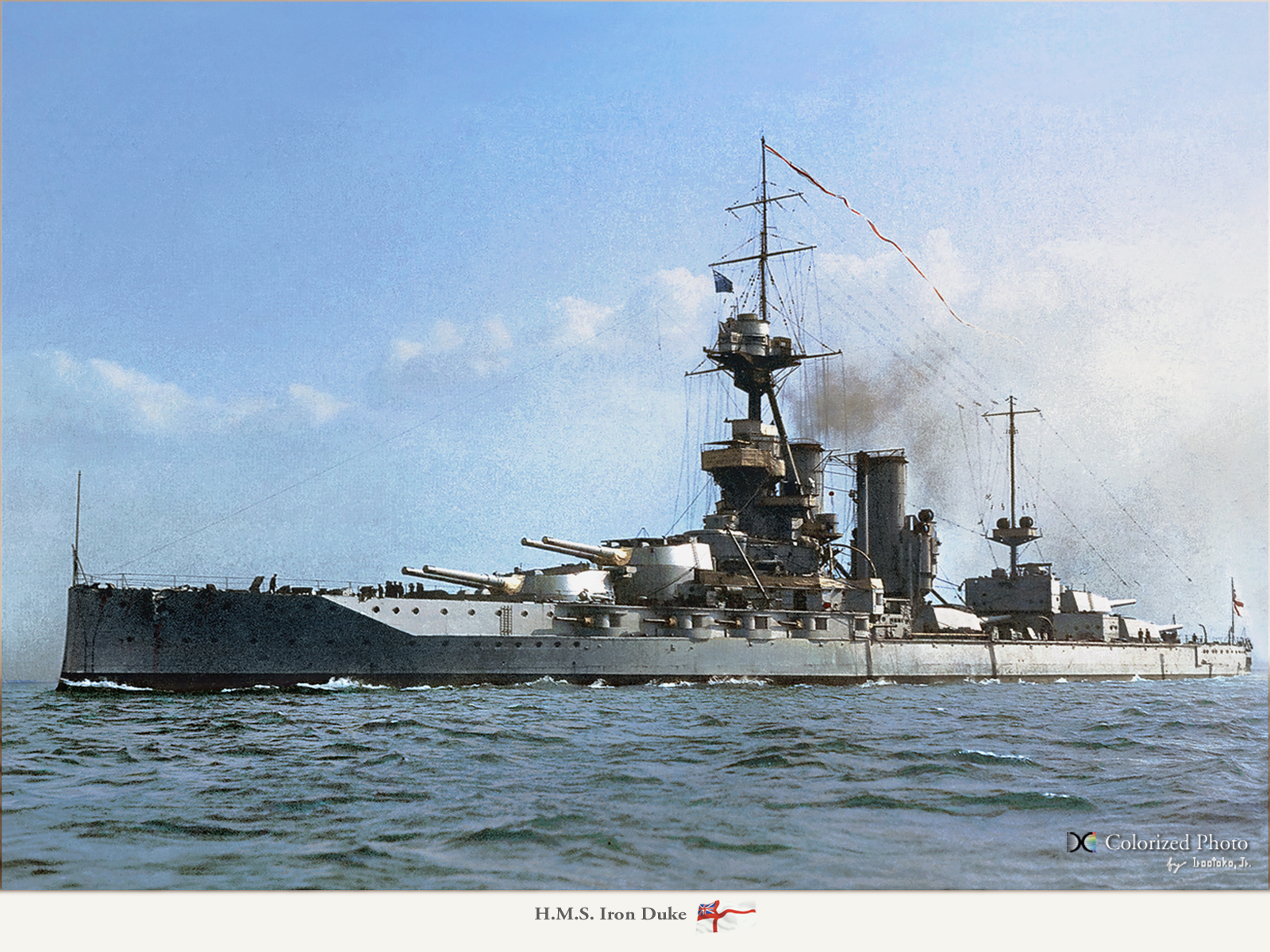

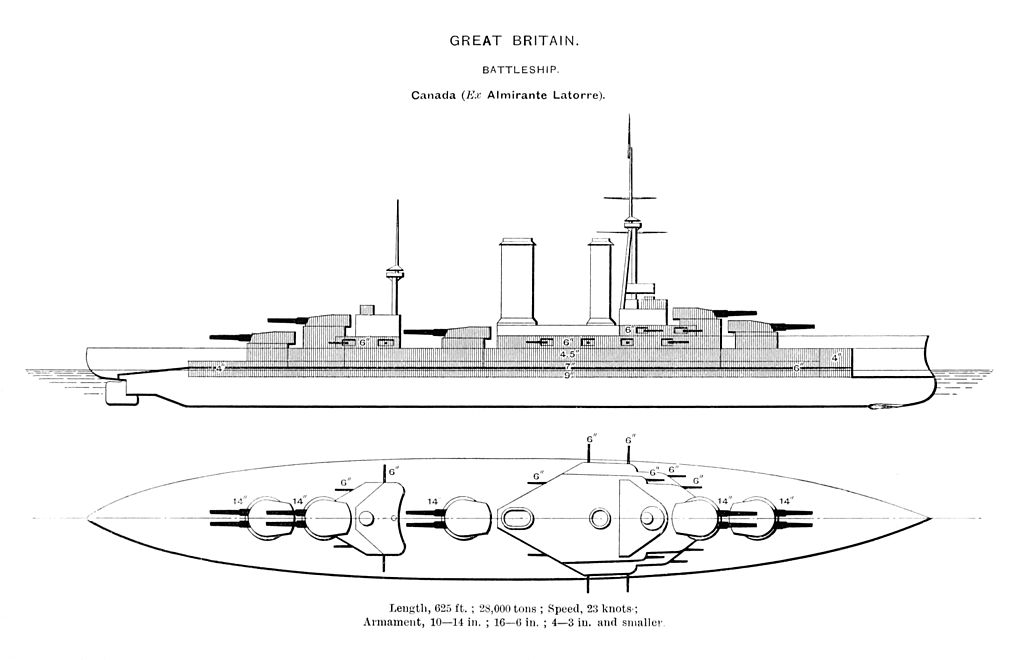

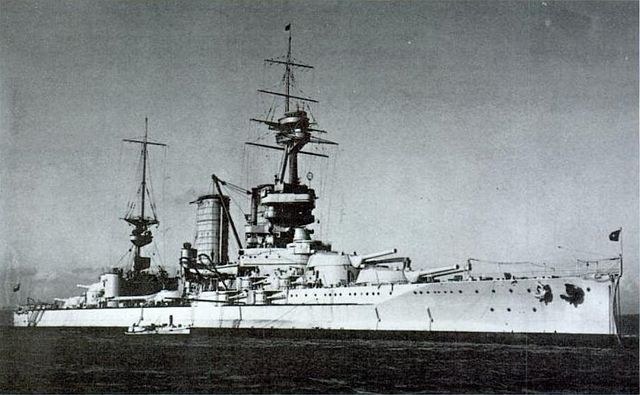

The design was modified to mount sixteen 6-in (152 mm) rather than initial twenty-two 4.7-in (120 mm) guns planned, making the displacement jumped by 600 long tons (610 t), to 28,000 long tons (28,449 t). Draft was augmented to 33 feet (10 m), and the top speed fell from a quarter-knot, to 22.75 knots. The general drawing resembled the contemporary Orion and Iron Duke classes, with five twin axial turrets, a battery of ten heavy caliber guns. This was less than the twelve of the Minas Geraes and Rivadavia, but woth a larger caliber, they can outrange them and bringing each time (and slightly faster) a heavier broadside. Moreover, their rangefinders and fire control systems were certainly more modern and provided a much greater accuracy.

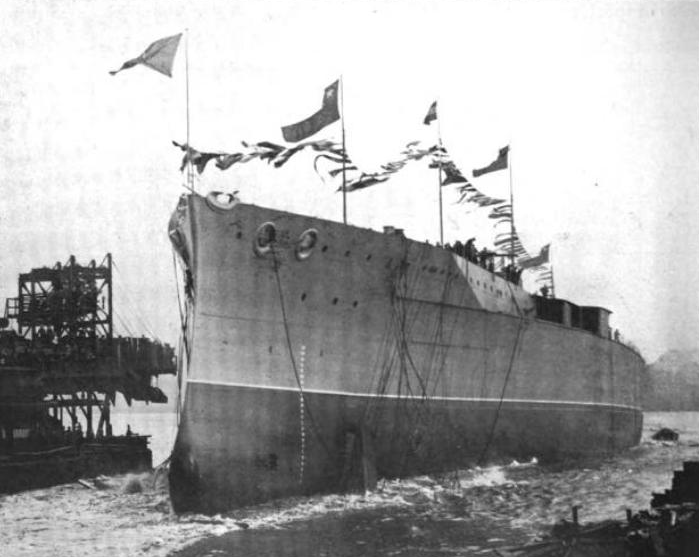

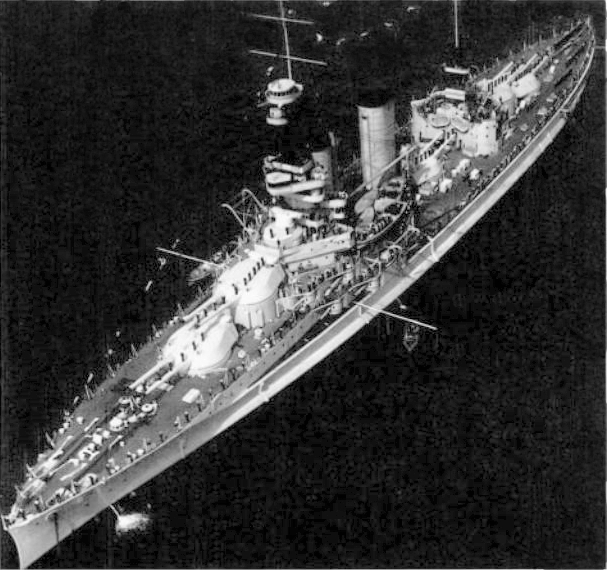

The Latore was laid down less on 27 November, 1911, ans so far her specs made her the largest ship that Armstrong had ever built, and the largest battleship at this point. The second, ordered on 29 July 1912, was laid down on 22 January 1913 only, as she has been delayed by Rio de Janeiro occupying her slipway.

Almirante Latorre was launched on 27 November 1913 in an grand ceremony attended by many dignitaries and Chile’s ambassador, Agustín Edwards Mac Clure, christened by his wife, Olga Budge de Edwards. At this point, the massive hill weighed 10,700 long tons alone. The ship was conducted to a working pier for completion.

The First World War broke out and all work on Almirante Latorre (named after Juan José Latorre) was halted. She was formally purchased on 9 September by Government for the Royal Navy, not forcibly seized to avoid backlash, because of Chile’s own particular “friendly neutral” status. She was eventually completed as work resumed on 30 September 1915, slightly modified for British service.

She was commissioned on 15 October as HMS Canada. Meanwhile, Cochrane’s construction was also halted for the duration of the war. She was purchased eventually on 28 February 1918, but only to be converted to an aircraft carrier, but labour shortages, workers quarrels with the direction and lower priority slowed her completion. She made a long career later as HMS Eagle.

Design of the Latorre class

General Characteristics

The Almirante Latorre class was basically a slightly redesign of the Iron Duke class, with a longer hull at 661 feet (201 m) overall, so 39 feet (12 m) longer. Her designed featured also less forecastle and more quarterdeck. She had larger funnels for a better draft and an aft mast. Above all, total displacement was a good indicator of her scale with 28,100 long tons (28,600 t) standard and up 31,610 long tons (32,120 t) full loaded whereas it was 25,000 tons/29,500 FL the the Iron Dukes. Latorre’s beam was 92 feet (28 m) versus 90 ft (27.4 m) but was “shallower” with a mean draft of 29 feet (8.8 m) versus 32 ft 9 in (9.98 m), which was always a good thing but for stability.

Armament of the Latorre class

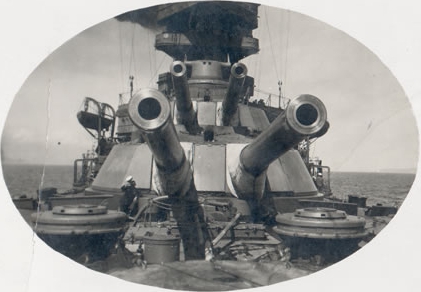

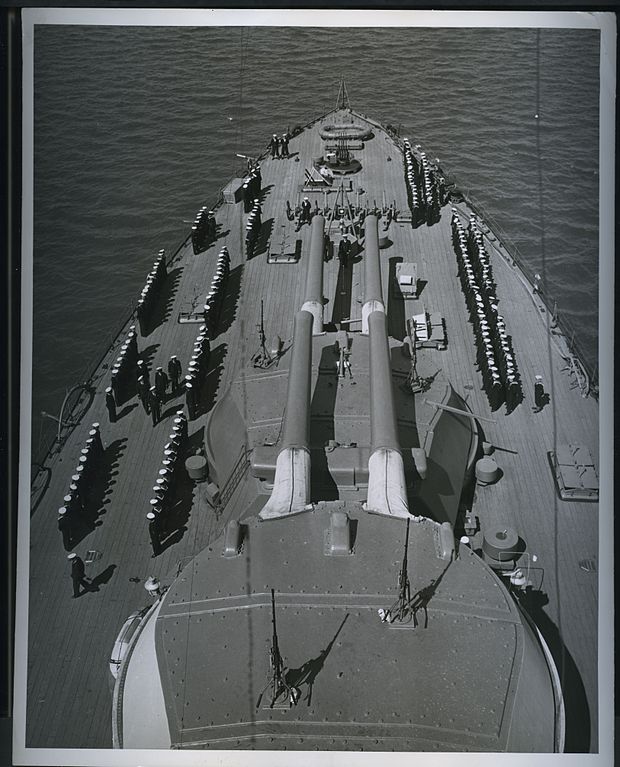

The class main battery was composed of ten 14-inch/45 cal. guns mounted in five axial dual turrets as for Iron Duke class. The same twin turrets superfiring fore and aft was kept, but the extra fifth single turret in the middle was separated by the aft superfiring pair by the rear superstructure and a mast. The superstructures design allow to fire in chase and retreat up to a certain angle, with a margin of security to avoid blast damage.

The Elswick Ordnance guns fired a 1,586-pound (719 kg) shell at 1507 ft/s (764 m/s). Their useful range at max elevation (−5° – +20°) was 24,400 yards (22,300 m). Fourteen has been manufactured for the Latorre, four kept as spares to replace worn-out barrels in mid-life, Kept by the arsenal to be sold later, but they were ultimately scrapped in 1922 unlike those for Almirante Cochrane. There would be reused after a while as the ship was converted. These guns were therefore a rarity, the only 14-inch 45-calibre naval gun manufactured by the company. A few others were also produced for Japan but requisitioned in 1914 and later used as railway guns at the front. The exact calibre was 355.6 mm, and muzzle velocity ranged from 2,450 ft/s (747 m/s) (1,586 lb shell) or

2,600 ft/s (792 m/s) (1,400 lb shell) depending of the projectile. Iron Dukes’s 13.5-inch (343 mm) guns and their range was up to 23,820 yards (21,780 m) at 20° at a slightly lesser muzzle velocity.

The secondary battery comprised sixteen 6-inch (152 mm) Mark XI guns. 155 of these ordnance pieces were built, weighing 19,237 lbs (8,726 kg), for a barrel length of 300 inches (7.620 m), a bore of 50 caliber, firing a 100 pounds (45.36 kg) shell filled with Lyddite, Armour-piercing cap or Shrapnel. The exact calibre was 152.4 mm. Its muzzle velocity was 2,900 feet per second (884 m/s), range 18,000 yards (16,000 m) at 22.5° elevation (less in barbettes).

They were completed by two 3-inch 20 cwt AA guns plus four saluting/DP 3-pounders. Close combat provision also included the traditional four submerged 21-in (533 mm) torpedo tubes. Two of the 6-inch guns located farthest aft were removed in 1916. They were indeed blast damaged by the amidships 14-in turret, o the total fell to fourteen.

Masked version of the standard 6-inch (152 mm) Mark XI guns (HMS Melbourne).

Propulsion of the Latorre class

Almirante Latorre was powered by Brown–Curtis and Parsons steam turbines producing an output of 37,000 shaft horsepower, on four propellers. The group was fed by 21 Yarrow mixed-firing boilers in separated boiler rooms. Top speed was around 22.75 knots (26.18 mph; 42.13 km/h). In comparison, the Iron Dukes powerplants were rated for 29,000 shp (22,000 kW), for a weaker top speed of 21.25 knots (39.36 km/h; 24.45 mph).

For their autonomy they carried 3,300 tons of coal and 520 tons of oil (all metric) could be carried. Theoretical range was 4,400 nautical miles (5,100 mi; 8,100 km) at 10 knots, a far cry of the Iron Dukes 14,000 nmi.

Protection

The armor belt range from 4 to 9-inch (102 -229 mm) on the ends, while her bulkheads were 3-4.5 in (76-114 mm).

Main turrets were protected by 10-in (254 mm) on the faces, 102 mm for the sides and 76 mm for the roof. Associated barbettes were 4-10 in (102-254 mm) while the conning tower was 11-inch (280 mm) thick. The armored decks ranged from 1 to 4 in (25-102 mm).

These figures were much lower compared to the Iron Dukes, which Belt was thicker, up to 12 in, as well as the Bulkheads at 8 in.

The Barbettes (10 in) were comparable but Turrets (11 in face and sides) were slightly thicker, while decks were thinner at 2.5 in max.

Almirante Latorre’s service life

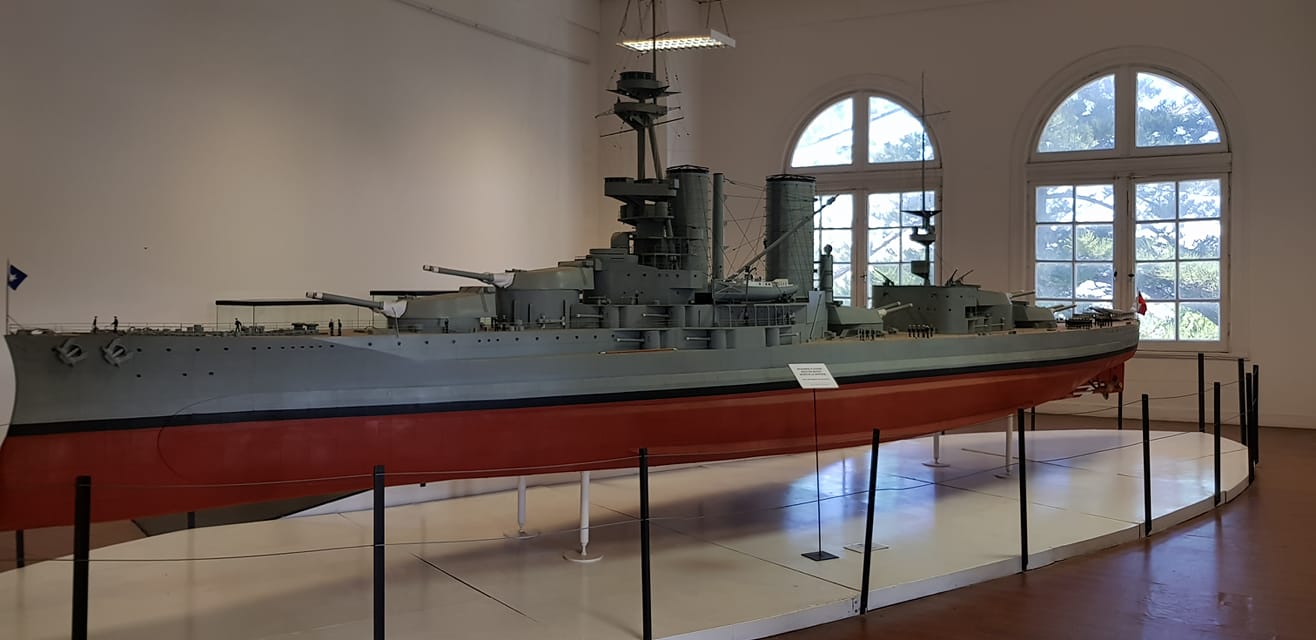

Model of the Battleship Almirante Latorre at the Valparaiso Museum – Courtesy of Triqui Bala.

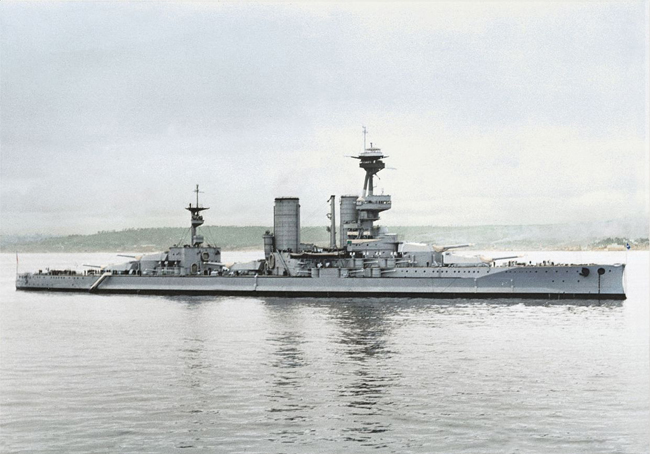

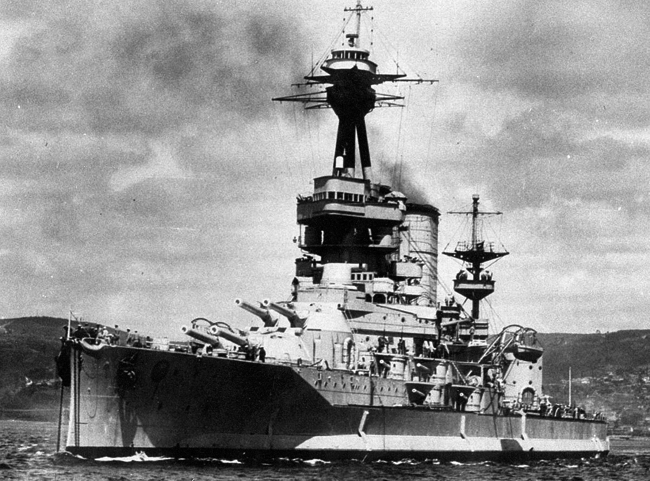

A Veteran of Jutland: HMS Canada

When the War broke out in Europe, the Chilean battleship was formally purchased by the British government on 9 September 1914, renamed HMS Canada. Modifications included two open platforms (the bridge was removed) and a mast between the two funnels on which was mated a derrick to service launches. Fitting-out completion was over on 20 September 1915, she was commissioned on 15 October.

At first she served with 4th Battle Squadron of the Grand Fleet, and fought at Jutland, 31 May–1 June 1916. She fired 42 main guns rounds and 109 lighter 6-in shells during the battle. She reported neither any hit or casualties but disabled the SMS Wiesbaden in two salvoes at 18:40 and fired on another unknown vessel around 19:20. She also fired with her secondary battery on German destroyers.

After the battle she was transferred to the 1st Battle Squadron in June 1916 and from late 1917 to mid-1918 received better rangefinders and range dials. Two of the aft 6-inch secondary guns were removed (blast damage). Flying-off platforms were later added atop the two superfiring turrets. She joined the reserve in March 1919 instead of being sent in the Baltic, on disposal for Chile or other purposes.

Indeed at that time there was a debate in Chile about what types of ships could bolster the fleet. British surplus warships were on offer, including two Invincible-class battlecruisers. However there was a rocky debate bout this acquisition, some promoted cheaper and more modern submarines and aircrafts instead; Other South American countries also were weary of another naval arms race.

Logically, Chile eventually purchased HMS Canada with four destroyers in April 1920. These were indeed the original orders of 1914. In addition total cost was less than a third of the amount Chile was to pay originally. Therefore HMS Canada was renamed Almirante Latorre again. She was formally handed on 27 November 1920, departing Plymouth with destroyers Riveros and Almirante Uribe; The squadron was under the command of Admiral Luis Gomez Carreño. In Chile, there was a ceremony held by president Arturo Alessandri on 20 February 1921 and the new battleship became the flagship of the navy.

As flagship of the Chilean Navy

Almirante Latorre frequently carried the Chilean president in official venues or events. In the aftermath of 1922 Vallenar earthquake for example, Almirante Latorre carried President Alessandri there, bringing humanitarian equipments, personal, rations, clothing and money. By that time the whole Chilean Navy was limited to the Latorre, a cruiser, and five destroyers. But the lack of a second battleship compared to Brazil and Argentina was deeply resented despite Almirante Latorre being individually superior. Her escort, a unique old cruiser, was not really useful.

In 1924, Almirante Latorre visited Talcahuano for the inauguration of a new naval drydock and after the fall of the January Junta in 1925 she carried President Alessandri at a Naval Review in Valparaíso. President Alessandri would also receive Edward, Prince of Wales on board, started negotiations for a British naval mission in 1926.

During the 1929-31 refit in the United Kingdom, four additional anti-aircraft guns were placed in the aft superstructure.

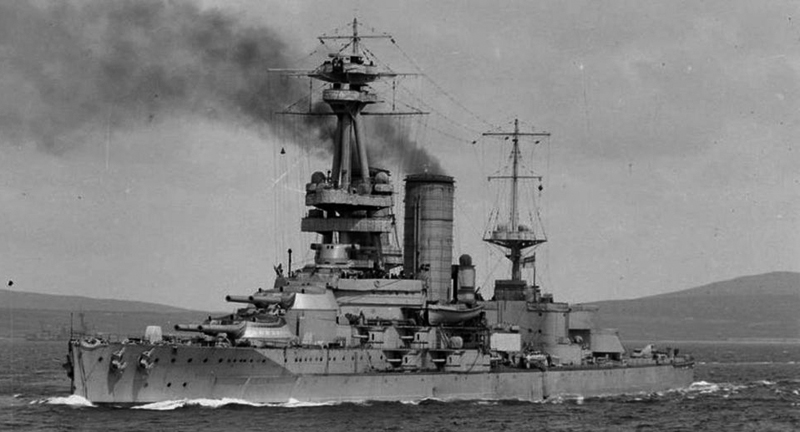

Modernization at Devonport

After a new partnership was signed with UK, Almirante Latorre sailed there for a modernization at Devonport in 1929. Departing in the Pacific coast she past Balboa an crossed the Panama Canal, refuelled at Port of Spain on 28 May 1929, crossed the Atlantic past the Azores and arrived in Plymouth on 24 June. Modernization included rebuilding her bridge, while her fire control system was comprehensively modernized and extended to serve the secondary armament as well. Her old steam turbine engines were also deposed and replaced by new models and boilers converted to oil-fire only.

A new mast was erected between the third and fourth turret. The hull received anti-torpedo bulges. A brand new anti-aircraft battery was installed on the superstructure. This took two years to complete and the ship departed after trials to Valparaíso on 5 March 1931, carrying two 33-long-ton (34 t) tug boats stored on her aft deck. She also received an aicraft catapult.

1931 Mutiny

South America is not stranger to coups, revolutions, rivaly between arms and mutiny. In 1931 While was hit badly by the 1929 stock crash crisis, seeing President Carlos Ibáñez del Campo leaving the office. Wages for civil servants fell to down 30% and naval personal in the Chilean Navy went on open revolt. After midnight 1 September, the crews jailed the officers and took the ships in the whole navy, taking advantage of the boxing tournament in La Serena were the sailors opposed to the mutiny. They elected a committee to sent requests to the government for full restoration of their salaries and punish those responsible for the Chilean economical depression. They will send later a list of twelve demands.

The Government was so keen to obey, fearing workers would join the movement across Chile. They asked the assistanvce of the US Navy and air force to assist them quelling the rebellion, which was flatly refused. Vice President Manuel Trucco choiced a path of reconciliation, and admiral Edgardo von Schroeders obtained a restpite. However the 4th fleet returned, all the assets of the mutineers on land were seized and the fleet was attacked by the air force. Only the submarine H4 was damaged while Almirante Latorre had a near-miss. This demonstration sapped the morale of the mutineers which asked for a truce. Almirante Latorre sailed later to the Bay of Tongoy with Blanco Encalada, and leaders were sentenced to death while others ended in jail.

The Latorre in WW2

In 1933 economic depression was still on hands and the Navy had to make budget cuts. Latorre was deactivated at Talcahuano, the crew dispersed and rendered to civilian life. She was not the only ship concerned, mothballed with a small caretaker crew which just ensured all ships were maintained in operational state. 1937 saw her sent for a short refit in the Talcahuano dockyard. The catapult was landed and AA was added. When the war broke out, the Latorre was definitely obsolete, even her AA was unsufficient and her protection was no longer relevant. However after the losses at Pearl Harbor, the US Government was desperate enough to ask Chile to purchase the Almirante Latorre and a few destroyers, which was declined.

The Latorre was fully reactivated nonetheless and participated in neutality patrols until the end of the war. She later joined a state of semi-active reserve but suffered a fatal boiler accident in 1951, killing three. She was not repaired and instead mothballed in Talcahuano, used as a storage hulk and decommissioned in 1958. She was sold the next year to a Japanese shipbroker.

Specifications of Latorre (1921) |

|

| Dimensions | 181.3 x 29.30 x 8.4m (594 x 98 x 27 ft) |

| Displacement | 28,600 t, 32,120 t FL |

| Crew | 834 |

| Propulsion | 4 shafts Brown-Curtis & Parsons turbines, 21 Yarrow Boilers, 37,000 hp |

| Speed | 22.75 knots (42.13 km/h; 26.18 mph) |

| Range | 10,000 km at 10 knots |

| Armament | 10 x 356mm/50 (14in) (5×2), 16 x 152mm/50 (6in), 2x76mm AA (3in), 4x47mm (1.9in) saluting, 2x533mm TTs (21in). |

| Armor | Belt: 9in (230mm), deck 1.5in (38mm), turrets, barbettes 10in (254mm), CT 11-in (280mm) |

Author’s illustration of Almirante Latorre, ex-HMS Canada

Author’s illustration of HMS Eagle, ex-Almirante Cochrane, never delivered and converted. The Chilean Government thought to ask her back but the cost of rebuilding her in original state was staggering.

Read More/Src

Conway’s all the world’s fighting ships 1906-21 and 1922-47.

Burt, R. A. British Battleships of World War One.

Garrett, James L. “The Beagle Channel Dispute: Confrontation and Negotiation in the Southern Cone”.

Gill, C.C. “Professional Notes”. Proceedings 40: no. 1 (1914)

Livermore, Seward W. “Battleship Diplomacy in South America: 1905–1925”.

Sater, William F. “The Abortive Kronstadt: The Chilean Naval Mutiny of 1931”.

Scheina, Robert L. Latin America: A Naval History 1810–1987.6.

Somervell, Philip. “Naval Affairs in Chilean Politics, 1910–1932”.

Worth, Richard. Fleets of World War II. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2001. ISBN 0-306-81116-2. OCLC 48806166.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Almirante_Latorre_(ship,_1913)

https://web.archive.org/web/20080608084301/http://www.armada.cl/site/unidades_navales/336.htm

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign