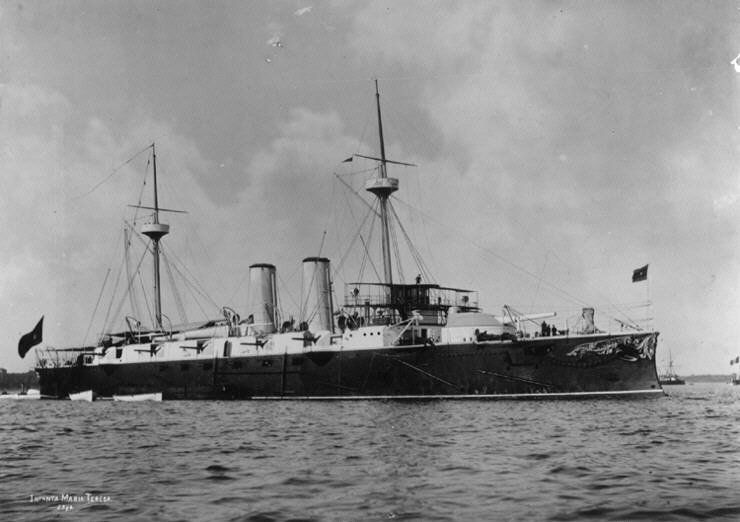

If it is a dubious privilege to have three cruisers of the same class sunk the same day, the Infanta Maria Teresa class shared it with other examples, as Cressy, Hogue Aboukir in WWI, three of the Zara class at Matapan in 1941 and three of the New Orleans class in Guadalcanal in 1942. These ships when planned in 1887 to complete the Armada rearmament with the battleship Pelayo were the most powerful cruisers ever in Spanish service, all built locally at Bilbao. With their powerful armament, good speed at the expense of protection, they were supposed to alleviate the lack of capital ship when defending Cuba for admiral Cervera when the war of 1898 broke out. All three were sunk during the battle of Santiago de Cuba on July, 3, by US Admirals Sampson and Schley.

Origin: Originally, the Spanish Navy had planned to build sister ships of the battleship Pelayo, but a confrontation with the German Empire in the Caroline Islands in 1885 caused Spain to divert the budgeted new battleships to a cheaper alternative, a serie of armoured cruisers instead. Armored cruisers were indeed considered more desirable than additional battleships at the time because their greater speed and range. For the Armada’s staff, they were just better suited for colonial crises responses.

Design of the class

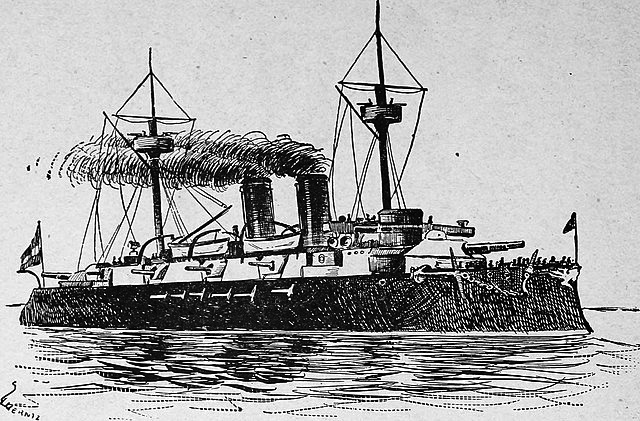

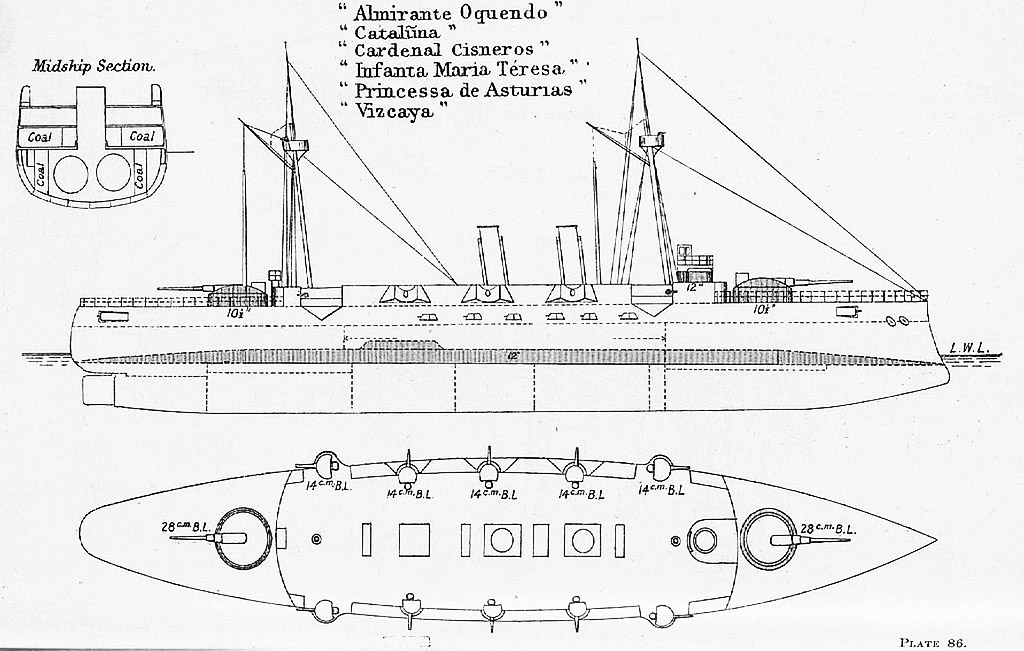

Brassey’s diagram on the serie

Bilbao naval shipyard in Spain was tasked to start on the basic design submitted (specifications) to propose a plan for three ships. They did not started from scratch, but they looked at Great Britain’s contemporary armored cruisers at the time and felt the Orlando class (1885) were a good start. Bilbao just increased their size and added a more powerful artillery, for a calculated initial displacement of 5,000 tons, and same armor.

The machinery arrangement produced a two-funnelled design, for ships that were armed with two 11-inch (279 mm) Hontoria guns mounted in barbettes on the center line fore and aft. This was more than their inspirators, the Orlando class, which had two BL 9.2-inch (233.7 mm) Mk VI guns. The large guns were the fear factor for any battleship, as they were nearly equal to the 12-in caliber (305 mm). The secondary battery was on the battery deck along the sides, ten 5.5-inch (140 mm), which was less impresive than the Orlando’s BL 6-inch (152.4 mm) battery.

However, protection was the poor child of the design, to ensure speed would be enough.

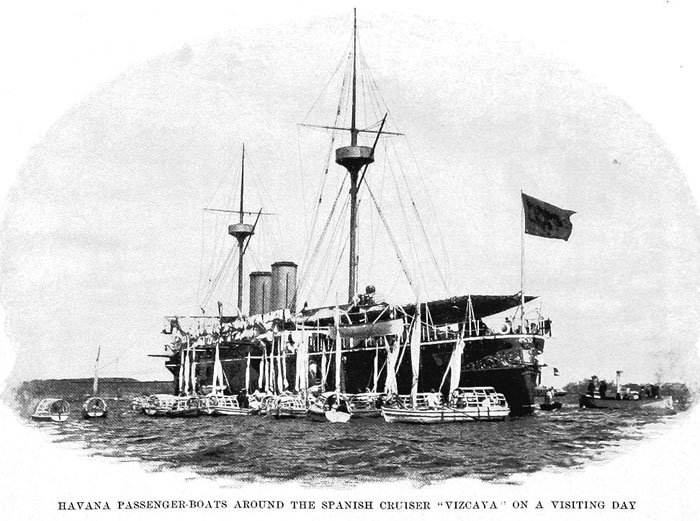

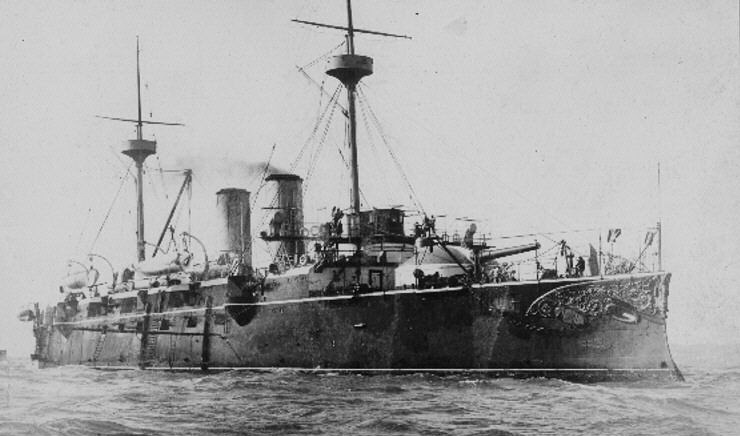

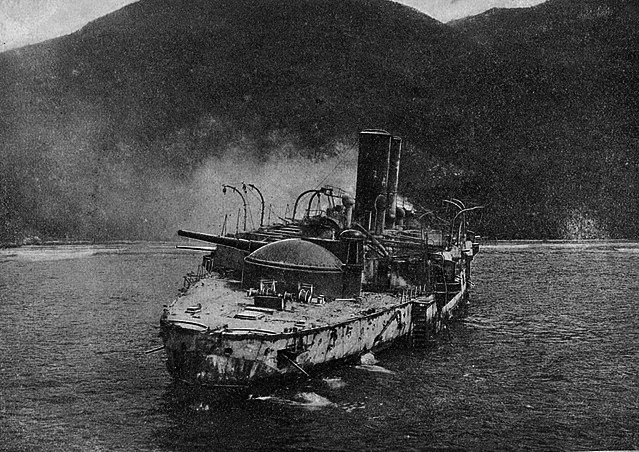

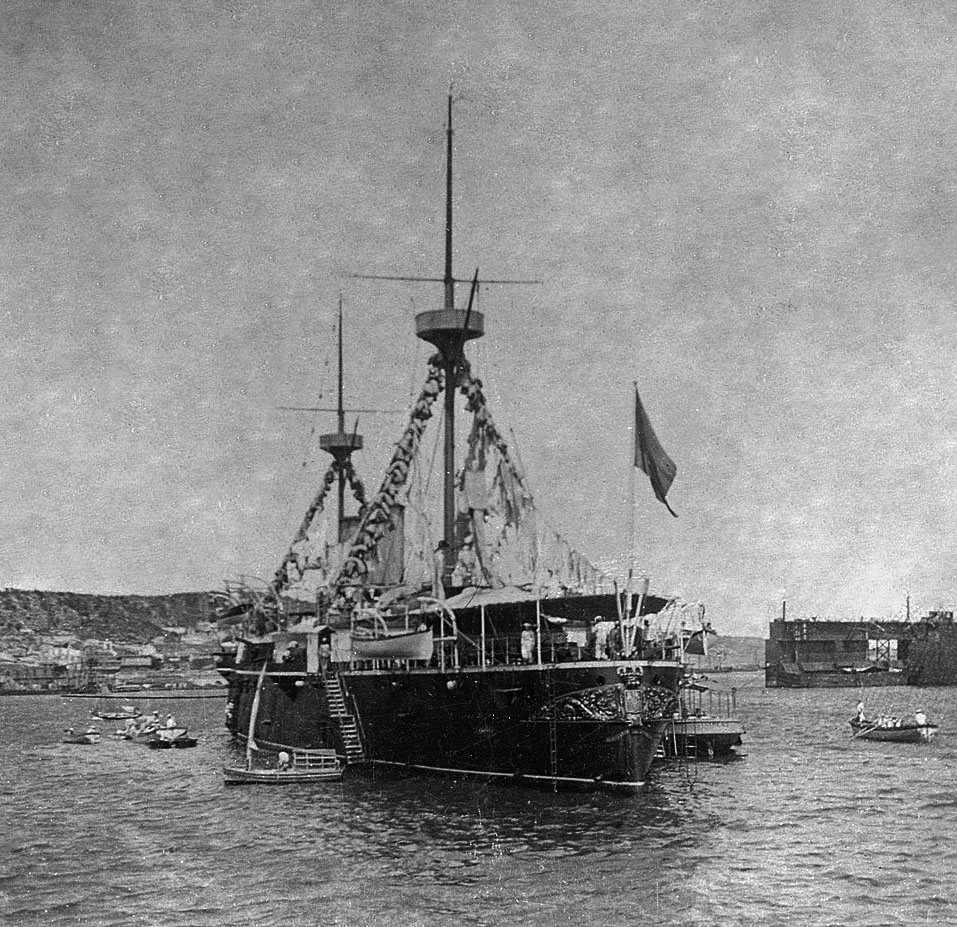

Vizcaya in Havana

In fact, when completed, these ships were initially classified as 1st class protected cruisers, but still, they were classified as armored cruisers in publications of the time, due to their low displacement (6,890 tons) combined to a protection (305-254 mm armored belt and 229 mm barbettes) that was still much higher than usual protected cruisers (up to 152 mm or 6-in), whereas the main artillery looked towards battleship. Just before the start of the Spanish-American War, as situation became tense around Cuba, the Berenguer government decided as a deterrence scheme, to call these cruisers “2nd class battleships”. Their main potential adversaries, the USN, had armored cruisers that were equal in some ways.

Overall, the ships measured 364 ft (111 m) long for 65 ft 2 in (19.86 m) in beam, making for a 6/1 ratio, making them relatively agile but not super-efficient for speed. The draft of 21 ft 6 in (6.55 m) maximum was close to that of a battleship and limited coastal operations.

Hull and general design

Bilbao Yard model of the class

Protection

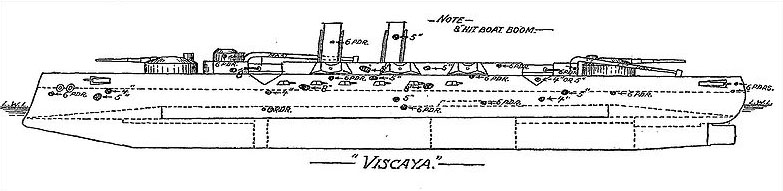

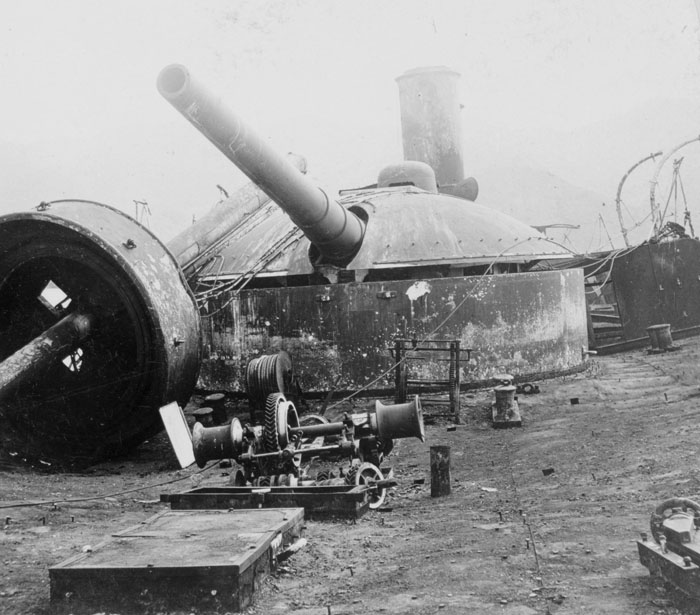

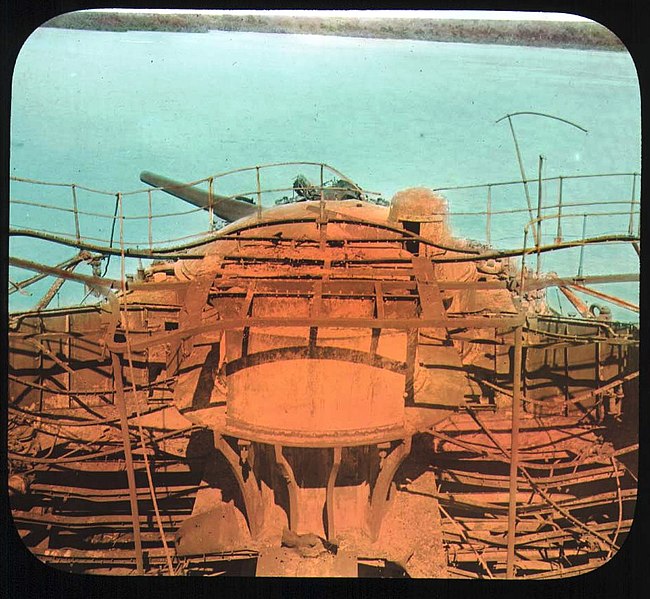

Post-battle detailed damaged assessment by the USN.

The armor belt was narrow and covered only 2/3 of the overall hull lenght. It was 12–10 in (30.5–25.4 cm) thick.

The armor belt was narrow and covered only 2/3 of the overall hull lenght. It was 12–10 in (30.5–25.4 cm) thick.

The main guns had barbettes, which crowns were armoured to 9 in (22.9 cm), goind down to the “citadel”

These barbettes only lightly armored hoods to stop shrapnel and protect the crews (probably less than 1-in or 30 mm).

The 5.5-inch guns were mounted in the open upper deck, above an unprotected freeboard. They were protected by gun shields qually thin, probably less than 1-in.

The armor deck was 2–3 in thick (5.1–7.6 cm) with the slopes being the thickest.

The upper decks (battery and weather) were just planked-over beams without steel plating, offering no protection.

The strongest part of the design was the Conning tower, which walls were 12 in (30.5 cm) thick.

The ships also were heavily decorated and provided with wooden furnitures and interiors that were not removed before combat in 1898. These fed the fires after shell hits.

But the greates problem was their high unprotected freeboard. Shells were free to go through and explode inside, notably close to ammunitions or just setting fire to the woody interior.

Powerplant

The powerplant was classic for the time, with two triple expansion vertical steam engines, driving to four-bladed screw propellers (diameter unknown), fed by six? double-ended boilers (no data) by analogy to the Orlando class. This arrngement gave them a total output of 13,700 CV, providing for a top speed of 20,25 knots. It was way more than an Orlando class (17 kts), and compared well with armoured cruisers of the time. When completed in 1893-95 they were indeed among the fastest, equivalent to the newly completed USS brooklyn (ACR-3) or New York (ACR-2), both rated at 20 kts.

Main Armament:

The two barbette for the Hontoria 280 mm guns were installed fore and aft.

More data and on navweaps

These were made by the Spanish Arsenal created by Gonzales Hontoria and were rated as 11″/35 (28 cm) Model 1883, shared by Pelayo, Infanta Maria Teresa, Almirante Oquendo, Vizcaya and Emperador Carlos V. They were based on Vickers designs. They entered service in 1888. Each weighted 32.0 tons and the barrels measured 385 in (9.779 m). Rate Of Fire was about 1 round per minute. They used separate bag-type rounds, either AP (cast iron bomb) 586.4 lbs. (266 kg) type, or HE 693 lbs. (315 kg) rounds.

The Propellant Charge weight 352.7 lbs. (160 kg) and Muzzle Velocity was 2,034 fps (620 mps) for a range of 11,440 yards (10,460 m)/15° elevation, terminal velocity of 1,017 fps (310 mps) with the AP rounds. The guns were tested against Krupp armor, with a penetration ranging between 11.5 in (292 mm) at 3,160 yards (2,890 m) and 5.4 in (138 mm) at 11,440 yards (10,460 m).

To protect the gun servants, they only had only lightly armored cowlings.

Secondary

Ten 140 mm Hontoria mounted on upper deck behind protective screens. They were designed in 1883 and introduced in 1886, becoming pretty common in the Spanish Navy. They weighted 4.4 t (4.9 short tons) for 5.3 m (17 ft 5 in) long (Barrel length 4.8 m/15 ft 9 in) on a 35 caliber. It used an interrupted screw breech and the mount cal elevate -10/+25°.

The Shell used Separate smokeless powder bagged charge and projectile, 16.4 kg (36 lb) with the shell weighting 20.6–39 kg (45–86 lb)

Muzzle velocity was 597 m/s (1,960 ft/s) and range 10.8 km (6.7 mi) at +17.5°

Tertiary

The light armament was plentiful and well able to defeat approaching torpedo boats. It was four-layered, down to what was necessary for a landing party, as befitting of a colonial cruiser.

-8 × 12-pdr (57 mm) rapid-fire Hotchkiss guns

-8 x 3-pdr (37mm) revolver Hotchkiss guns

-2 x Nordenfelt machine guns (six-tubes, 37 mm)

-2 x 70 mm bronze guns for landing parties

-2 x Maxim 8 mm liquid cooled MGs (Same)

Torpedo Tubes

These eight 365 mm torpedo tubes were located underwater: One in the bow, one in the stern and the remainder six in three series amidship, under the waterline and belt. No type precised, resumably the 1885 14 inches Whitehead model.

Construction

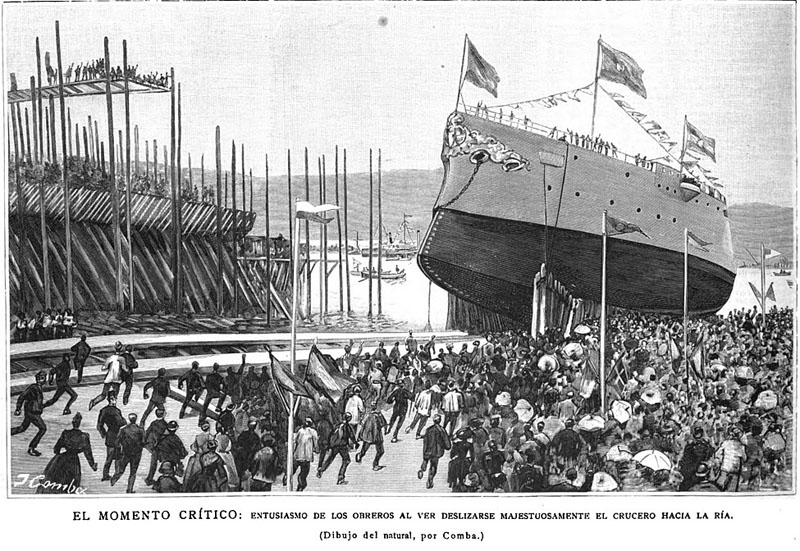

Launch ceremony, Infanta Maria Teresa

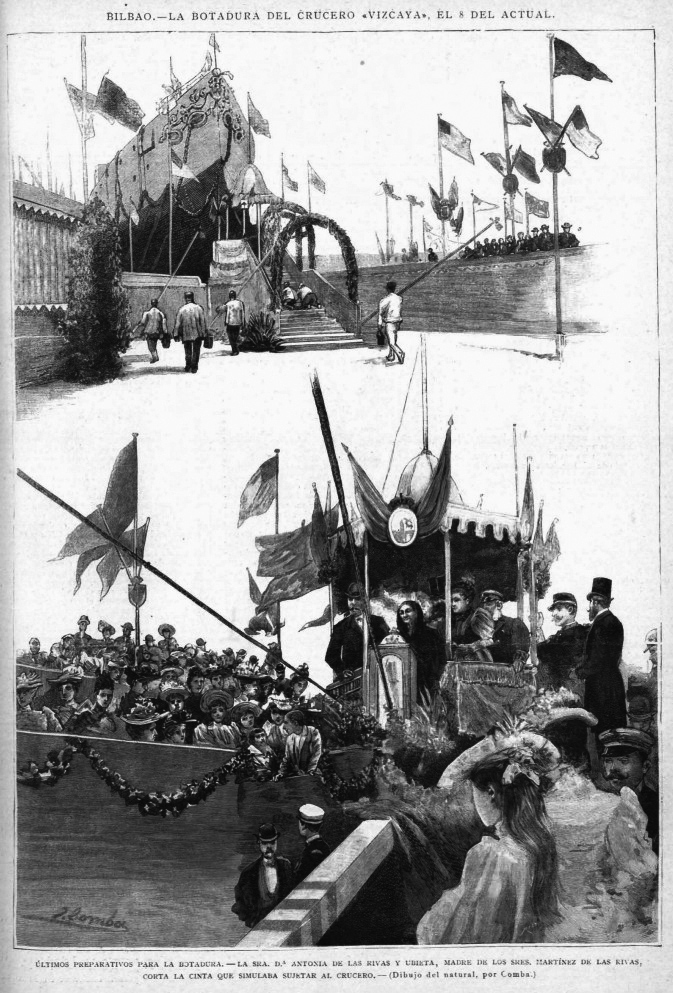

Infanta Maria Teresa was started at Sociedad Astilleros del Nervión (Bilbao, Northern Spain) laid down on July 24, 1889, launched August 30, 1890, and completed by 6 August 28, 1893. Viscaya (Biscay) was laid down on October 7, 1889, launched on July 8, 1891, and completed on August 2, 1894. Admiral Oquendo was laid down on November 16, 1889, launched on October 3, 1891 and completed on August 21, 1895, so four years after launching. This delayed the next order of three cruisers, the Princesa de Asturias class (see later).

So they had just a few years training (three years for Ocquendo) in 1898, and like the rest of the fleet, nearly not enough gunnery practice, or shell reserves for it.

Launch ceremony, Vizcaya

Author’s illustration of Vizcaya in 1898.

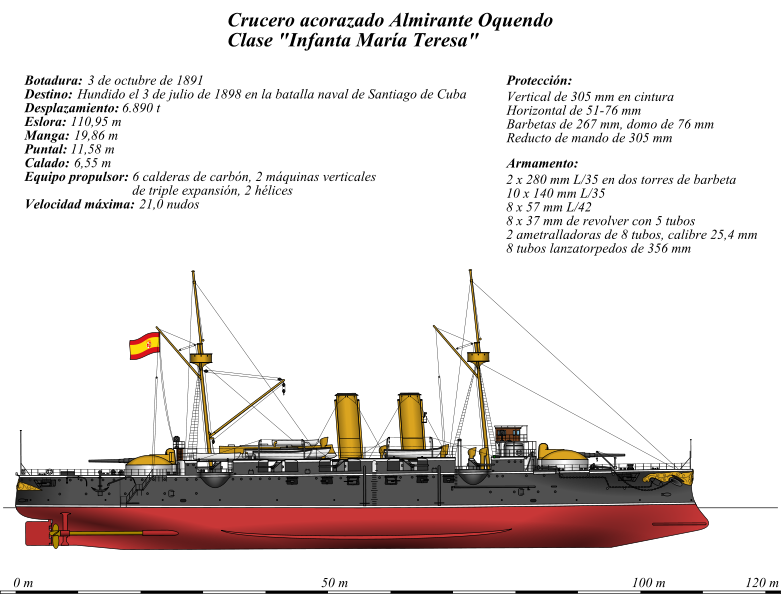

CC illustration of the Almirante Oquendo

⚙ specifications |

|

| Displacement | 6,890 tons standard |

| Dimensions | 111 x 19.86 x 6.55 m (364 ft x 65 ft 2 in x 21 ft 6 in) |

| Propulsion | 2 shafts VTE, 6? Boilers 13,700 ihp (? kW) |

| Speed | 20,25 knots (37.4 km/h) |

| Range | 1,050 tons of coal (normal), Uknown |

| Armament | 2× 28 cm/35, 10× 14 cm/35, 10× 12-pdr, 10× 3-pdr, 8× Nordenfeld MG, 2× Maxim MG, 8 TTs (sub) |

| Armor | Belt 30.5–25.4 cm, Barbettes 22.9 cm, CT 30.5 cm, Deck 5.1–7.6 cm |

| Crew | 484-497 |

Links/Sources

Books

Chesneau, Roger; Kolesnik, Eugene M. (1979). Conway’s All The World’s Fighting Ships 1860-1905.

del Rey Vicente, Miguel; Canales Torres, Carlos (2010). Breve Historia de la guerra del 98. Madrid: Ediciones nowtilus.

Tucker, Spencer (2009). The Encyclopedia of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American. Volumen 1.

Links

alojados.revistanaval.com/

todoavante.es

mgar.net/cuba/santiago.htm

mgar.net/cuba/santiag2.

eldesastredel98.com/capitulos/vizcaya.htm

eldesastredel98.com/capitulos/impactos.htm

todoavante.es/ Vizcaya_(1893)

spanamwar.com/vizcaya.htm

spanamwar.com/teresa.htm

todoavante.es/ Infanta_Maria_Teresa_(1893)

stories.lavanguardia.com/ el-ultimo-pecio-del-imperio

on en.wikipedia.org

on es.wikipedia.org

Models Kits

Not much but at least the 1/700 by WSW Modellbau is a solid reference. Src Kit review

Video

The Infanta Maria Teresa class in action

These cruisers were not bad per se, in 1895 when the last was commissioned, they were still a match for any navy, being fast and well armed, as well as rasonably well protected, although not optimal. The real problems were both internal and external. The former was the intensive woodworking in ther accomodations and decks. They were rushed to combat in such a way these flamable materials were not removed before the battle.

The external factors were due to the lack of maintenance of the ships: Like all of Cervara’s ships they were in dire need of drydocking. Some had accumulated such had a marine “life crust” to negate her their top speed -especially in Oquendo’s case- and they were dramatically short of ammunition. Some of her guns were even not operatable due to the lack of maintenance or shells, or both. Worst still, a large part of the 140 mm shells were found defective from the factory. In short, if fired, gases came out of the breech; which caused many injuries and death on Oquendo in particular, the cruiser in worst shape.

The second issue was the lack of training, especially gunnery training. The lack of ammunitions severely restricted these exercizes and as a result; Spanish gunners were far less proficient than their US counterparts. This was especially true in the Philippines where the ships and crews were in an even more dire state.

The last one was the battle itself. Comparatively to the rest of the fleet, Cervera’s crews were still an elite, and they did the best of their abilities in the worst conditions: At Santiago de Cuba, the US fleet barred their T, leaving them no fighting chance. Under orders, they had to escape, and formed the line, making them lambs to the slaughter.

The Battle of Santiago de Cuba

Admiral Cervera y Topete was a competent admiral, but he received orders to sail for Cuban waters from his flagship the INFANTA MARIA TERESA, pride of the Spanish Fleet, across the Atlantic with full preparations. After coaling in the port of Santiago de Cuba, the outer entrance was soon blockaded by the US fleet, leaving few options but to sally forth. The sortie out of Santiago Bay on July 3rd, 1898 sealed the fate of the entire fleet. His flagship drew USN fire early on and she was soon she was seriously damaged and afire, leaving the head of the fleet unable to do its direction job. Cervera still apparently made a last-ditch attempt to ram Schley’s flagship, USS Brooklyn, before running ashore to save his men.

The whole battle was more an execution than a fair fight: As the ships left Santiago in line, the entire US Battlefleet blockading the entrance waited for them, lying in a way to “bar the T” of Cervera. They could bring all guns to bear and pick the cruisers as they arrived one by one, swapping their fire on the next each time they disabled one.

Infanta Maria Teresa

Infanta Maria Teresa

When she was built, the completion director was no other than Pascual Cervera y Topete, in charge of seeing her through full commission. The three cruisers were taken to Ferrol for their full completion, from Bilbao, but construction delays had increased their price (price tag of twenty million pesetas apiece instea dof the 15 notified in the 1887 contract). But they were commissioned for the first two in 1893. Oquendo had to wait until late 1895.

Infanta Maria Teresa at Sao Vincente, April 1898

On the morning of September 2, 1893, she entered Ferrol (captain Don Joaquín Cincunegui), making a trial cruise speed of 11 knots, with six boilers afire. Official speed tests has been carried out in Galician (Atlantic, Bay of Buscay) waters on September 18. Her normal speed was 19 knots at normal draft, 21 knots at forced draft.

At first she srved with the instruction Squad and left Cartagena at the end of May for her first official sortie. She appeared at the Kiel roadstead in Germany by June 1895 escorting the battleship Pelayo and the cruiser Marqués de la Ensenada under orders of Rear Admiral Martinez Espinosa, representing Spain for the inauguration of the Kiel Canal.

She became also at the head of the squadron, the first Spanish ship to cross the new canal to the Baltic and back.

In January 1896, Rear Admiral Don José Reguera y González Polo took charge of the Training Squadron which comprised Pelayo, Almirante Oquendo, Infanta María Teresa and Vizcaya. Later they took part in the celebrations for the anniversary of President Ulisses S. Grant and monument inauguration in New York on April 27, 1897, together with the cruiser Infanta Isabel. At the time she was under command of captain Don José Morgado. They left the big apple on May 11.

By late June 1897 the two cruisers were back in Mahón where the squadron was based. She visited the Galician coast and port of Lisbon in September 1897 under Rear Admiral Bermejo y Merelo, together woth her sister Oquendo, Vizcaya and the brand new cruiser Christobal Colon escorted by the brand new Destroyer of the Audaz class. They were in Cádiz by October 1897, but Rear Admiral Bermejo left command to be appointed Minister of the Navy, replaced by Rear Admiral Pascual Don Cervera y Topete, himself a former Minister of the Navy. In November 1897, the Training Squadron set sail for Santa Pola.

Three torpedo boats remained in Cádiz until they were supplied, securing a budget, scheduled to join them later in Santa Pola for fleet maneuvers, scheduled between November 27 and December 22, 1897. They were soon joined by three other torpedo boats from Cartagena. The fleet was in Alicante by December, then Cartagena.

By January 1898, the Minister of the Navy ordered Cervera to trandfer his flag to Vizcaya as Infanta María Teresa was to visit to New York in courtesy after USS Maine visited Havana. Admiral Oquendo later also visited the United States while Cristobal Colon sailed to Genoa to have her main guns installed. In Spain only Infanta María Teresa and the old Lepanto were left.

As tension grew fast, Colon was called back, without her guns.

The squadron was partly equipped for overseas operations in Cartagena when on February 15, 1898 USS Maine blew up in Havana, a casus belli for the white house. Pascual Cervera had to scramble the fleet, while Infanta maria Teresa was prepared to sail under command of captain Concas y Palau. They left San Vicente de Cabo Verde (Cape Verde islands) on April 2, 1898 for Santiago de Cuba.

Infanta María Teresa was the lead shi dueing the famous battle, when Cervera left under orders the bay of Santiago, on July 3, 1898. By drawing fire, Cervera hoped to leave some chance to the following cruisers. But the cruiser was soon seriously damaged it and caught fire. Cervera eventually grounded the cruiser a few miles west of the entrance to Santiago Bay, and ordered to abandon ship. The crew thus managed to swim ashore and escape certain death.

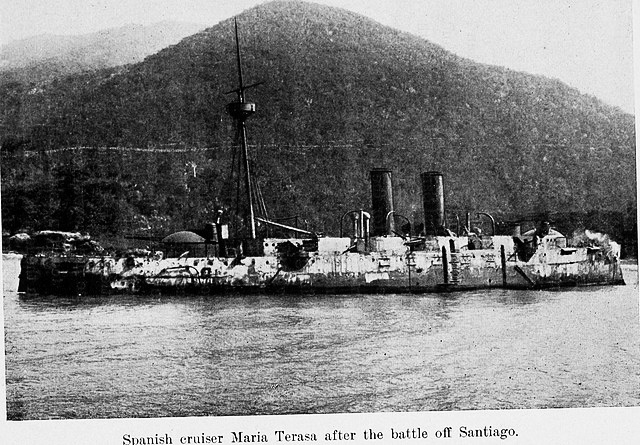

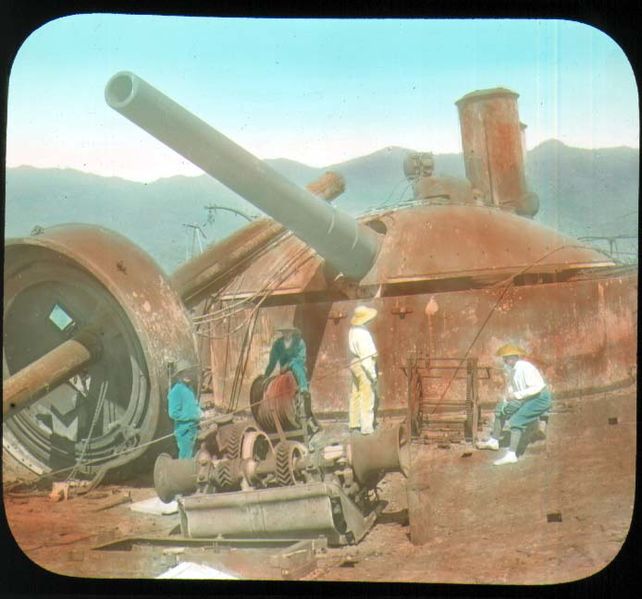

The wreck of Infanta Maria Teresa after the battle

Despite the battered state of the cruiser, she was a valuable prize. The United States Navy sent a boarding party to axmine she ship long after the fires died out. They found the ship salvageable, and so she was refloated, taken in tow to Guantanamo Bay for preliminary repairs. But as she was being towed by USS Vulcan to Norfolk for the second leg of her trip, in order to be taken in hands in Virginia for furthjer repairs and US standardization, a tropical storm hit. The towline was cut and the ship disappeared from view, finally found days later sank between two reefs off Cat Island (Bahamas). Her hull had been batters in such a way this time she was declared a total loss. Perhaps the cruiser avoided Spain the further humiliation to sport the US flag…

Vizcaya

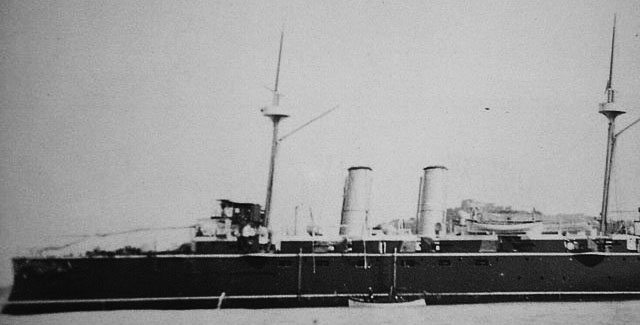

Vizcaya

Vizcaya had about the same career as her sisters. Seh was ironically sent to New York in early 1898 as an exchange after the visit of USS Maine. After the latter blew up, she rushed back to Spain to be outfitted for overseas service as her sisters, integrating Admiral Cervera’s fleet. She crossed the Atlantic and entered Santiago de Cuba for final preparations, and recoaling. Blockaded, she followed thre rest of Cervera’s force, second in line during the battle on July 3, 1898.

Cristobal Colon and Vizcaya

Despite the lead ship took the bulk of US fire, she too, started to be hit, and she too, four 8-in hits, nine 6-in and 12 of light caliber. In fire, unable to respond, Captain Antonio Eulate eventually followed the lead ship and ran his cruiser aground, on the rocks near Aserradero near Santiago while raisong the white flag to avoid further fire. Under orders to abandon ship, the crew managed to leave the ship on boats or swimming ashore. The US Navy then offered assistance as the fight was seeminglover and cease fire ordered. Captain Eulate was later carried, wounded, aboard USS Iowa; Seeing his ship still furiously burning he allegedly wave his hand saying “Hasta Luego, Vizcaya” when the forward compartment detonated…

Long after the fires died out, the same US team that inspected the wreck of Infanta Maria, came aboard Vizcaya. Unlike her sisters, the damage cause by the explosion has been so servere she was declared a total loss. Her wreck was only pârtially dismantled over time, but her remains can be still seen at Granma highway near Aserradero. She had been making the delight of divers for over 125 yeaas now. The Santiago de Cuba Naval Battle Underwater Park has been created to preserve her as a war grave.

Long after the fires died out, the same US team that inspected the wreck of Infanta Maria, came aboard Vizcaya. Unlike her sisters, the damage cause by the explosion has been so servere she was declared a total loss. Her wreck was only pârtially dismantled over time, but her remains can be still seen at Granma highway near Aserradero. She had been making the delight of divers for over 125 yeaas now. The Santiago de Cuba Naval Battle Underwater Park has been created to preserve her as a war grave.

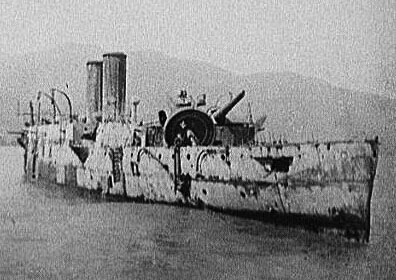

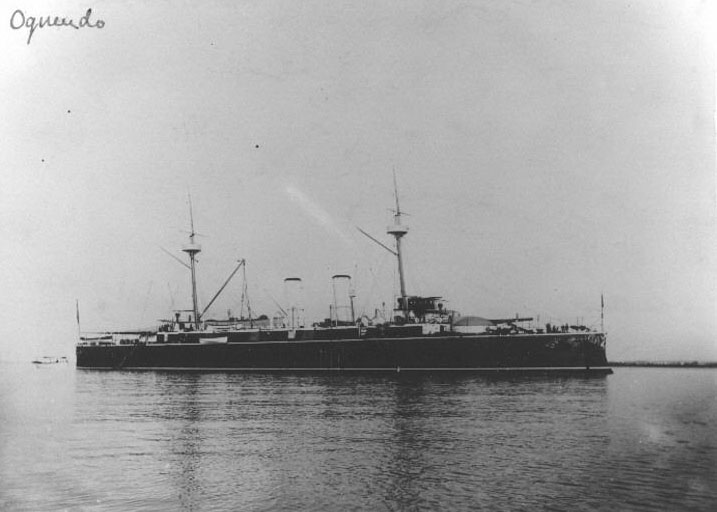

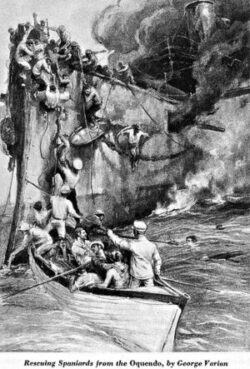

Almirante Oquendo

Almirante Oquendo

She was named after after Admiral Antonio de Oquendo (1577–1640) commanding the Spanish fleet at the Battle of Pernambuco (1633), where the Spanish won a great victory against the Dutch.

In the spring of 1898, Almirante Oquendo was in Havana, Cuba. After Vizcaya also arrived to Havana from New York, both headed for the Cape Verde Islands to join Admiral Cervera’s squadron, and as drydoc space was lacking she was not cleaned up. It was so bad she only can manage 12-14 knots.

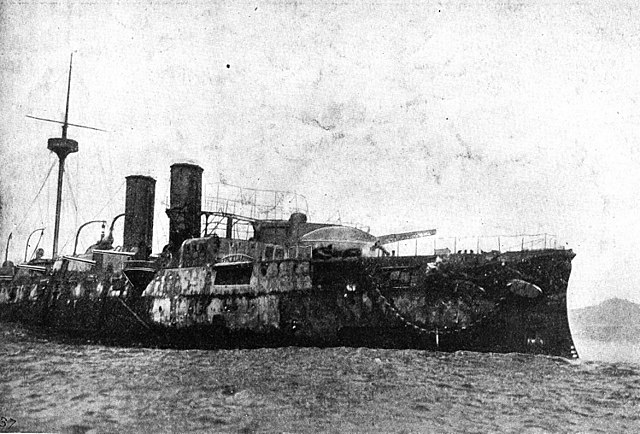

The stranded Oquendo after the battle

On July 3, she was fourth in line to sally out. Like the other she was next as a target for the battleships USS Iowa, Oregon and Indiana barring the T of Cervera at the mouth of Santiago Bay. Concentrated fire fell on her, destroying her rapidly before sge could even leave or fire back. She took 43 12-pdr hits from the Iowa ravaging her upper decks but also several 8-in hits, one 6-inch hit, one 5-in hit, and many 4-in hits. On of the 8-in round made it under the forward turret, jamming it, and killing officer and all gun crew instantly.

On July 3, she was fourth in line to sally out. Like the other she was next as a target for the battleships USS Iowa, Oregon and Indiana barring the T of Cervera at the mouth of Santiago Bay. Concentrated fire fell on her, destroying her rapidly before sge could even leave or fire back. She took 43 12-pdr hits from the Iowa ravaging her upper decks but also several 8-in hits, one 6-inch hit, one 5-in hit, and many 4-in hits. On of the 8-in round made it under the forward turret, jamming it, and killing officer and all gun crew instantly.

One of he 140 mm Hontoria guns had a defective shell and blew up, killing all the crew and setting afire the deck and ammunitions.

Boilers eventually blew up leaving Oquendo dead in the water. Captain Lazaga was mortally wounded but he ordered to ran aground. This happened around 10:30 in the morning, 700 m from the Cuban shore. 120 men had been killes so far, the remainder sawm to shore. Víctor M. Congas Palau later related the loss of Oquendo and the fate of the crew in these terms:

Missing there was the brave commander of the Oquendo, my dear lifelong companion D. Juan Lazaga, who with his glorious memory will leave the departure from the port of Santiago and the return to Bajo del Diamante as an example to all seafarers in the world. done as if it were an everyday outing, already having his ship completely destroyed and having burst a 20-centimetre projectile inside the bow tower. Under these conditions, he affectionately dismissed the pilot and finished taking out his cruiser calmly, performing the most admirable act of the entire combat. His second, Sola, was also missing, split in two by a projectile; the third chief Matos, and the three most senior lieutenants, and up to 121 individuals were missing, all dead, of that heroic crew.

To this day the wreck is lying near Juan González beach. Two of her cannons still protrude from the water. Like Vizcaya she is now a war grave, part of the Underwater Park of Santiago de Cuba.

Colorized Daguerreotypes of the ship when examined

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign