The “Mighty Hood”, the symbol

The HMS Hood is exceptional in more ways than one: She was the last battlecruiser, launched way after the Japanese Kongo class ships. She was the most powerful warship afloat during the interwar. She was above all the proud steel ambassador of the whole Royal Navy and of the country. She spent many years showing the Union jack in every harbour from 1921 to 1941. She was invincible in the mind of the average citizens.

The aura of this symbol of a ship however, could not mask a fundamentally outdated concept. The HMS Hood made that clear by paying the ultimate price, in a painful demonstration of the concept inanuity. This legendary artillery duel of the two the world’s most powerful warships opposed Hood and Winston Churchill’s own nightmare, KMS Bismarck.

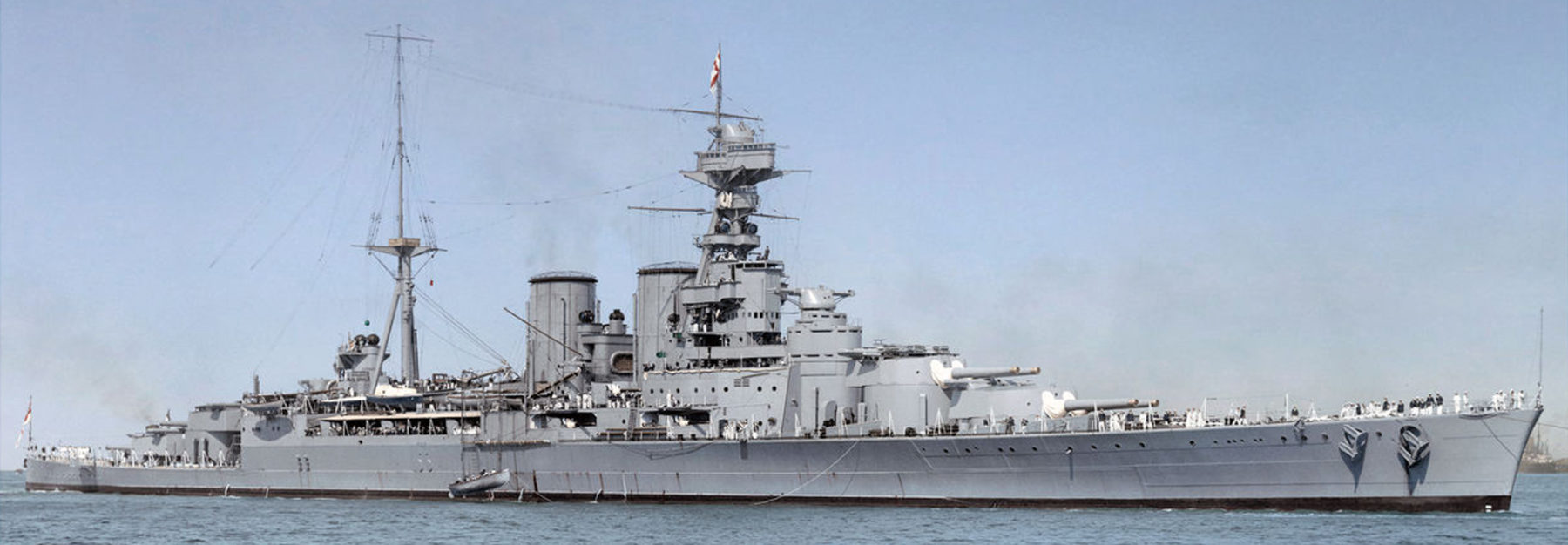

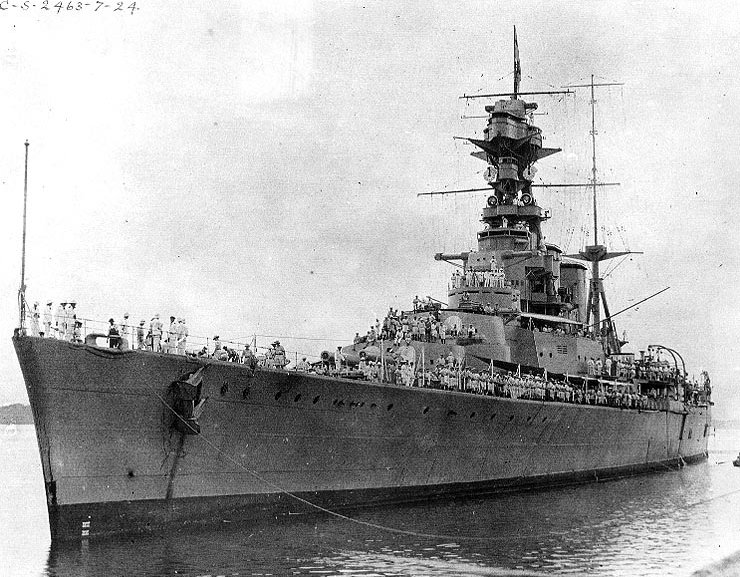

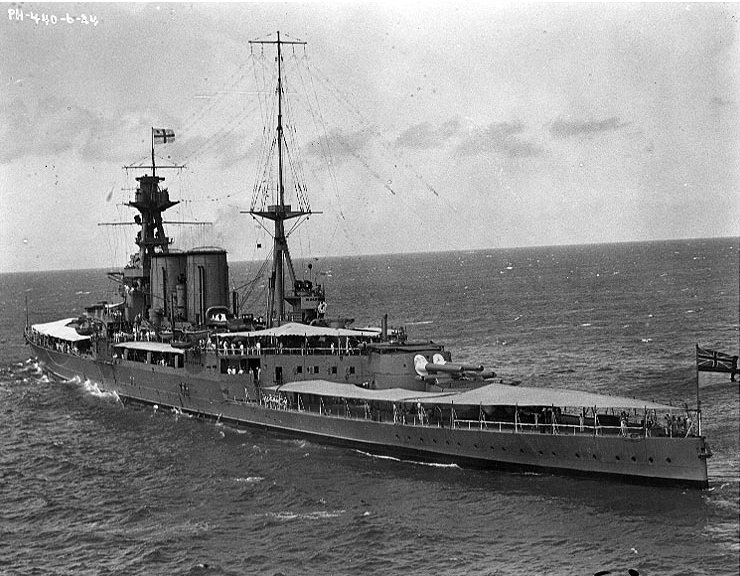

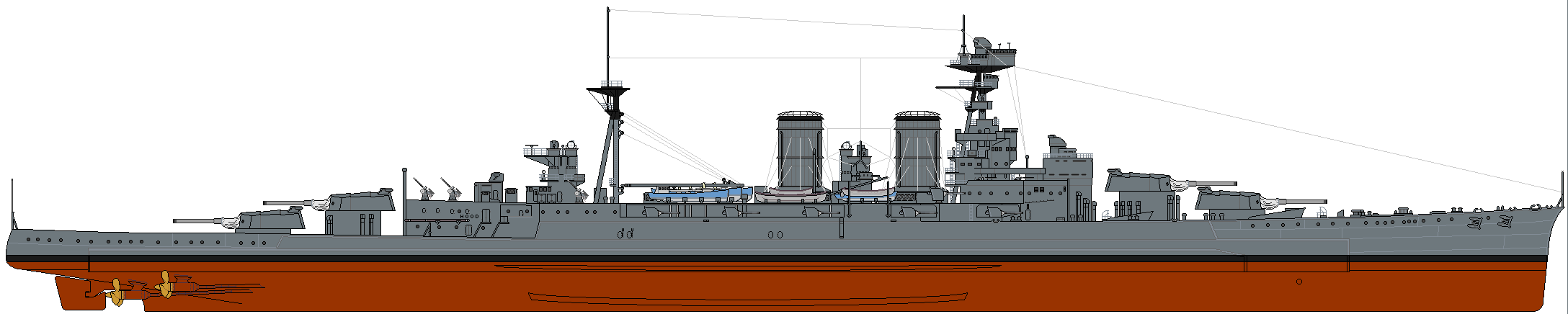

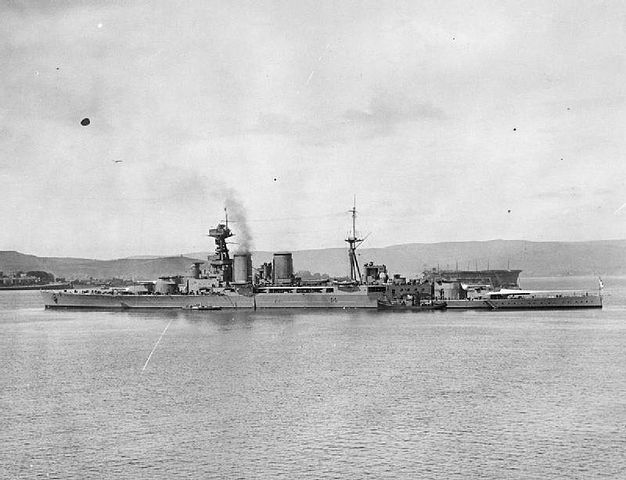

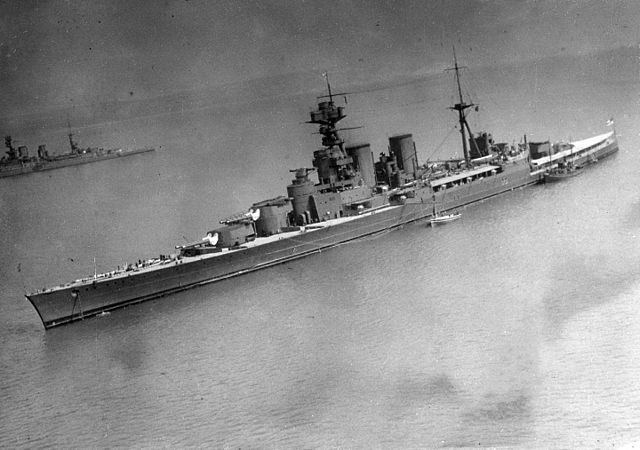

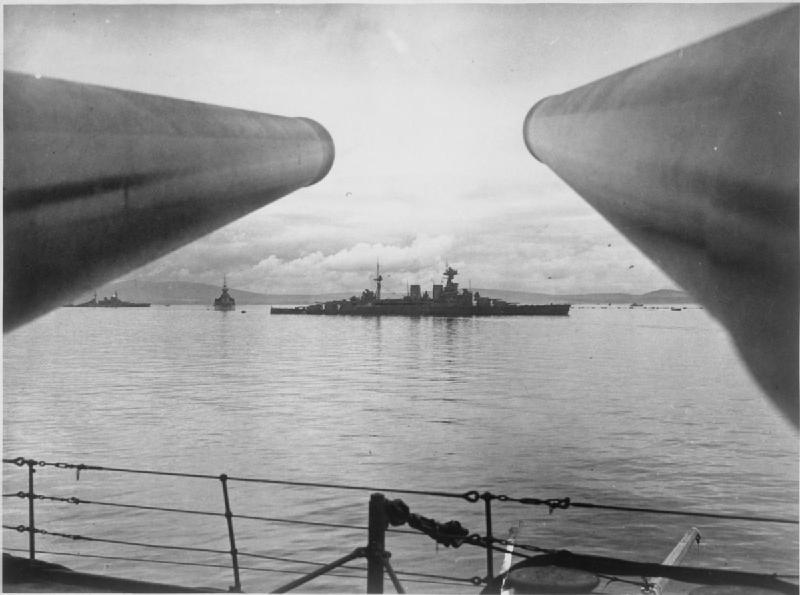

The Hood in 1924. The tragedy of this beautiful ship was to never undergo the major refit she needed in order to better withstand the German salvoe, as well as better meeting the needs of the fleet during the war.

Early developments

The Hood first and foremost was betrayed by an armor designed before the Battle of Jutland. Parabolic trajectories were estimated then too uncertain to constitute a sufficient risk to weigh down the ship. This was sacrificed on the altar of sacrosanct speed. Jutland did not shown at the time how much these sacrifices would cost. The tremendous losses of battecruisers this day was not yet well explained, until the discovery of the wreck and re-reading of the case. This warning was not followed by the addition of real protection thereafter, and when the Bismarck catch her the result was clear and flawless.

What really was the Hood: A battlecruiser or a fast battleship ?

For the Royal Navy Hood was a battlecruiser. However some modern historians (such as Anthony Preston) considered her as a fast battleship, improving over the Queen Elizabeth-class battleships. On paper her level of protection was the same, but she was significantly faster. Vice Admiral William Sims and other USN officers in Europe discussing with Admiral Henry T. Mayo, (at the head of the Atlantic Fleet) spoke of the Hood also as a “fast battleship”, advocated back home the development of a similar class, but eventually they choose the lightly armoured Lexington-class battlecruiser class instead (later cancelled).

There was some influences from the Hood on the Lexington designs indeed, although the main armour belt was thinner and “sloped armour” made systematic. The four above-water torpedo tubes was also an influence. Royal Navy documentation of the time described any battleship capable of 24 knots + (44 km/h; 28 mph) as a “battlecruiser” regardless of the protection, like the G3 class later at the basis of the Nelson class.

The Hood protection was updated after Jutland but did not fares well on paper against later 16-inch (406 mm) guns generation like the American Colorado-class and the Japanese Nagato-class. Royal Navy’s pundits were aware of this and so the Hood was used as a proper battlecruiser, in the battlecruiser squadron (with the Renown class). The choice of engaging the Hood was not foolish in May 1941, it was only driven by the urgent need of a ship that can match Bismarck’s speed and armament, regardless of protection.

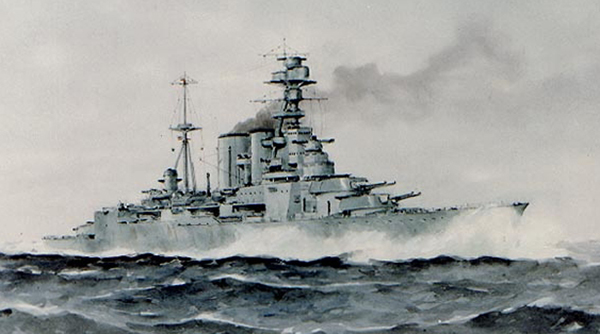

HMS Hood circa 1932

Design development of the last British battlecruisers

About the “Admiral Class”

In 1915 the Admiralty studied a replacement for the Queen Elizabeth-class battleships. The Director of Naval Construction, Sir Eustace Tennyson-d’Eyncourt, prepared designs. Specifications included to retake the armament, armour and powerplant of the battleship class but with a new hull made for speed and all the latest underwater protection innovations. The first was known as design ‘A’, submitted to the Admiralty on 30 November 1915. The draught was reduced by 22% as the ship was widened by 104 feet (31.7 m), lengthening to 810 feet (246.9 m).

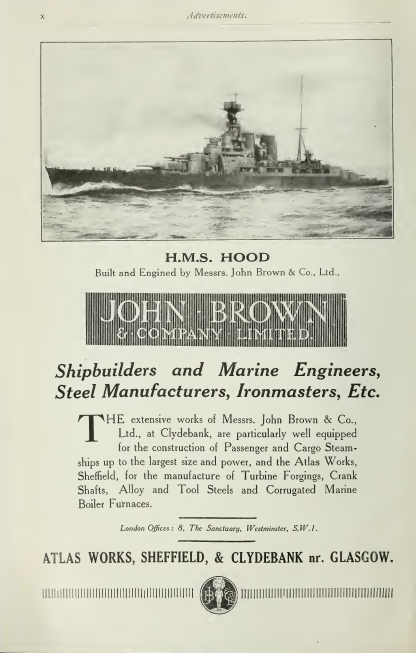

John Brown yard’s pride was the HMS Hood, here adverstised in the 1923 edition of Brasseys.

Operationally maintenance could only be made at Rosyth and Portsmouth, but large anti-torpedo bulges were designed, and there was still a secondary armament of twelve 5-inch (127 mm) guns (forecastle deck). There was a high freeboard, and reserve buoyancy with an estimated speed of 26.5 knots (49.1 km/h; 30.5 mph). It was 2.5 knots faster than the Queen Elizabeth class. However First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir Henry Jackson, widely detected that better deck protection was preferrable to defeat plunging shells in long-range gunnery duels.

This led to order a revised design, called ‘B’. The latter has a maximum beam of 90 feet (27.4 m) to the expense of underwater protection. Two more revision with a reduced speed to 22 knots, shortening the hull to make the ship easier to “park” in existing floating docks and minimum draught were sent to the Admiralty, called ‘C1’ and ‘C2’. ASW bulge protection was restored in the first. The second was as long as the QE class, but with the best bulge protection so far. ‘C2’ was only 610 feet or 185.9 m long, but with a greater draught. Secondary guns were reduced and armour thickness in some places as well. The Admiralty rejected both designs, asked for a revised version ‘A’, shortened and with the same speed as the QE. and the old 5.5-inch (140 mm) guns for secondary armament.

Admiral John Jellicoe, the Grand Fleet commander, saw these designs and commented that there was a need for battlecruisers, not battleships. He knew what British Intelligence carried back from Germany, plans of the three new Mackensen-class battlecruisers capable of 30 knots and carrying height 15.2-inch (386 mm) guns. They were on paper superior to the two Renown-class and the three Courageous-class. Jellicoe’s own experience was also that theere was no need of an intermediate in speed between a battlecruiser and the Queen Elizabeth-class. Eventually he came with the idea of either an improved 21 knots battleship OR a 30 knots battlecruiser, and advocated strongly for the latter.

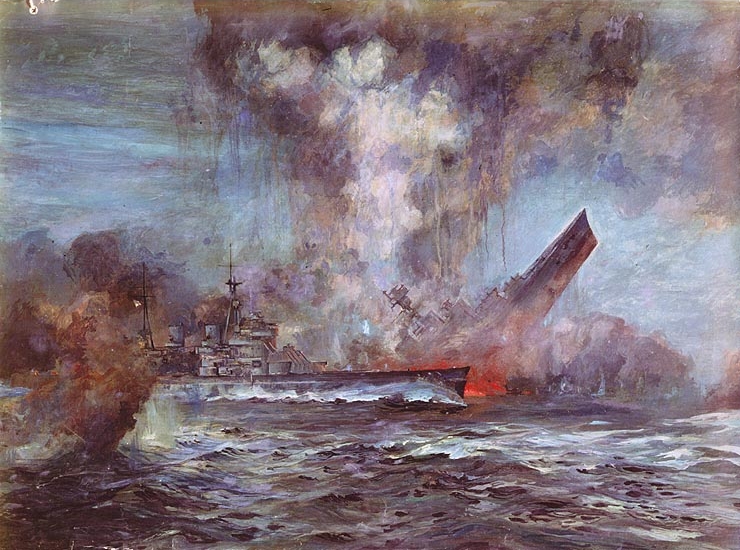

The loss of HMS Hood by Drachinfels. Most probable scenario, a very lucky hit.

The Director of Naval Construction drafted two new designs after February 1916, two 30-knots battlecruisers armed with eight 15-inch (381 mm) guns like the Mackensen. The first displaced 39,000 long tons (39,626 t), using also large-tube boilers (at the insistence of the Engineer-in-Chief of the admiralty), making her much larger than any previous capital ship to reach the desired speeed. The second design had small-tube boilers and save 3,500 long tons with less draught. The DNC then was asked for four more designs using small-tube boilers in February. The third design was an enlarged ‘2’ with 160,000 shaft horsepower and 32 knots and the others introduced heavier 18-inch (457 mm) guns in various configurations. It was was selected upon Admiral Jellicoe advice for an eight-gun design. From there, two variants were proposed with either 12 or 16 5.5-inch secondary guns. On 7 April the latter approved, orders followed on 19 April for three battelcruisers called Hood, Howe and Rodney, hence the “admiral class”. Anson was ordered on 13 June 1916.

Jutland and design revisions

HMS Hood was laid down on 31 May 1916, just as the Battle of Jutland took place. The infamous loss of three British battlecruisers shook the Navy to the core, spawning outrage and requiring a thorough investigation into possible design flaws. As a result, the construction of the new battlecruisers was stopped immediately, pending results for possible revisions. Admiral Jellicoe himself participated in the investigation and blamed the losses to faulty cordite handling procedures. Indeed practice shown that to achieve greater rate of fire, safety doors were left open and measures normally used in peacetime were relaxed. Anti-flash equipment in magazines and handling rooms were to be fitted on future designs as a result, as well as reinforcing deck armour over the magazines. The DNC (Director of Naval Construction) and Third Sea Lord however did not agreed about the magazines penetration was shells, which had severe consequences in future years.

HMS Queen Mary at the battle of Jutland. The result had deep and immediate consequences in the design revisions of HMS Hood.

In July 1916, the DNC submitted two revised designs, the first had slight armour increases to the deck, turret, barbette, and funnel uptake armour, 5.5-inch ammunition hatches and hoists. Electrical generators were also doubled and the displacement rose by 1,250 long tons, draught increased by 9 inches (228.6 mm). The second design made the class fast battleships as the protection level was even greater with vertical armour doubled, but horiztontal protection left unchanged. The latter displaced 4,300 long tons more than the original design, costing also half a knot in speed. On paper this desifn was a 7 knots (13 km/h; 8.1 mph) faster QE with improved torpedo protection. The return of both revised designs led to more variations in armament, with triple fifteen-inch turrets. The Admiralty eventually settled on the second “fast battleship” design. Construction resumed from 1 September 1916, after four month of design revisions.

Other reports coming from the battle analysis led to a revised armour scheme, notably the deck armour was slightly increased to cope with shells under 30° plunging trajectories. New alterations were made in 1917. The turret faces and roofs received a better protection. This new changes bring 600 long tons more, deepening the draught by 3 inches (76.2 mm) while speed fell to 31 knots. In 1918 the magazine crowns were doubled. However the price paid was the removal of the funnel uptakes armor. In May 1919, the main deck armour abreast the magazines reached three inches (76 mm). Four 5.5-inch guns were removed to save weight.

The very last planned revision in 1941 (never made) was to include her main deck over the forward magazines thickened to 5-6 inches (152 mm) over the rear magazines to the expense of the four above water torpedo tubes protection and the torpedo control tower walls reduced. Later another plan would lead to its replacement by a new structure and completed by a new bridge a la Warspite.

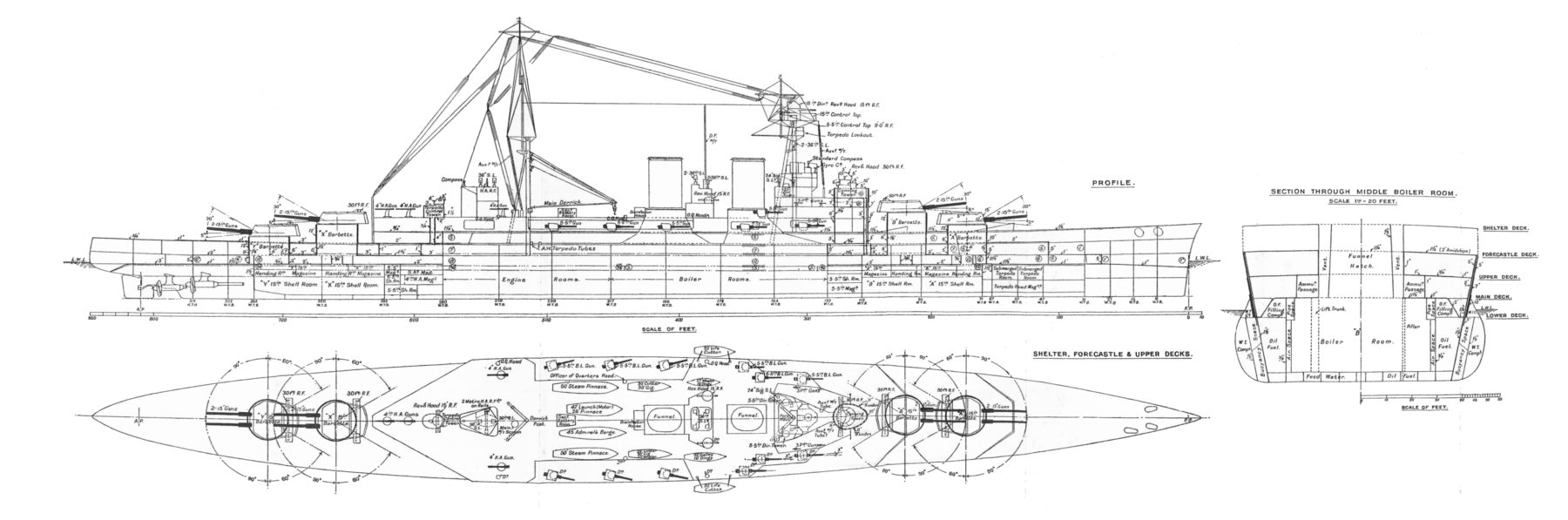

3-views of the ship – The blueprints. Prow by Christopher Snook, Stern by Thomas Schmidt

What could have been the Admiralty class

The Hood’s three sister ships was left suspended in 1917 to save labour workforce and resource for more urgent needs such as the construction and repair of merchant ships and escorts. Design work progressed however. Hood was so much advanced in 1919 that the remaining three ships could have constituted their own class, including many changes designed and not integrated into the Hood. At the end of 1917 indeed, their turret roofs and armoured bulkheads were revised, their bridge structure, funnels placement, also the 16-in shellrooms and magazines.

Hood’s construction was maintained all along in case the Germans delivered their new battlecruisers, largely pushed by Admiral Beatty. When the was ended, the three sister-ships were cancelled and we are left with “what if”s.

The Admiral-class ships were much larger than the Renown class, longer at 262.1 m, larger at 104 feet (31.7 m) and draftier at 31 feet 6 inches (9.6 m). This increase was 33.5 m x 4.3 m. Displacement at 41,200-45,620 long tons (46,352 t) was an increase of 13,000 long tons, the equivalent of two cruisers. Metacentric height was higher at 4.6 feet (1.4 m) and ASW protection much better with a complete double bottom.

Propulsion-wise, the increase was also considerable, the four Brown-Curtis single-reduction geared steam turbine arranged in three engine rooms with two wing shafts, and a unique middle compartment for the inner shafts. In case one torpedo hit the wing shafts this did not affected the central room, allowing the ship to go on. In addition there was cruising turbine built into the casing of each wing turbine. Twenty-four Yarrow small-tube boilers were separated into four large boiler rooms, with a total output of 144,000 shaft horsepower (107,000 kW), enough for 31 knots.

Outline drawn from the original Blueprints for the 1936 edition of warships today (high definition, can takes a wile to load).

The Admiral-class battlecruisers would have been armed with the intended same eight BL 15-inch Mk I guns and Mark II turrets, as the Hood and QE ships, capable of a −3° +30° elevation, 20° loading angle, 120 shells per gun carried, and secondary armament of sixteen masked BL 5.5-inch Mk I guns on pivot mounts on the forecastle deck. Their maximum range was 17,700 yd (16,200 m) at 12 RPM. In their initial form these “admirals” also received four QF four-inch Mark V AA guns elevated to 80°, 15 rpm, and theoretical 31,000 ft (9,400 m) ceiling. Torpedo armament was generous with two 21-in submerged broadside TTs forward of ‘A’ turret, eight above-water Mark V tubes abreast the rear funnel. They could be traversed by hydraulic power, using cordite charges. 32 Mark IV and IV* torpedoes were carried.

The Admiral-class ships controlled fire from two fire-control directors. They were redundant in case one was disabled. The first was above the conning tower and the other in the fore-top tripod. Data from the rangefinder was transmitted to a Mk V Dreyer Fire Control Table on the platform deck, converted into range and deflection data. Targeting was recorded and shown on a plotting table for the gunnery officer. This arranement was kept for the hood, as the secondary armament 5.5-inch directors each side of the bridge assisted by two additional fore-top rangefinders, all fitted with a local Dumaresq calculator and spotting data sent on the same table on the lower deck. This data was calculated by two Type F fire-control analog computers. AA guns were controlled by a 2-metre (6 ft 7 in) rangefinder on the aft superstructure. Torpedoes also were guided by various rangefinders and data provided to a Dreyer table in the torpedo TS in the lower deck but it was removed during Hood’s 1929–1931 refit.

The Admiral-class waterline belt was 12 inches (305 mm) thick, angled 12° outwards, allowing torpedo hits to vent to the atmosphere. The sloped belt was very close to the 330 mm found in the latst British dreadnoughts and clearly way above the usual battlecruiser protection level. It was indeed only xx on the Repulse. The HMS Hood’ figures could be applied to the class. Strangely, the outer faces of ‘A’ and ‘Y’ barbettes were considerably thicker (below decks) than the others. The conning tower (9-11 in) was record-thick for a British capital ship. This piece weighted as much as 600 long tons (610 t) alone, a destroyer.

The main fire-control director was protected by an armoured hood 6-3-2 in, and a 6-in communications tube ran to the main deck. The anti-torpedo bulges of the Admiral-class battlecruisers were the first fitted and the most advanced in the world for ASW protection. The HMS Hood had this system. All in all of the Admiral class has been completed, their deck protection in particular would have made them more difficult to penetrate, although still insufficient in 1941. The result of a duel with the Bismarck for any of these ships, unmodified, could have been equally disastrous.

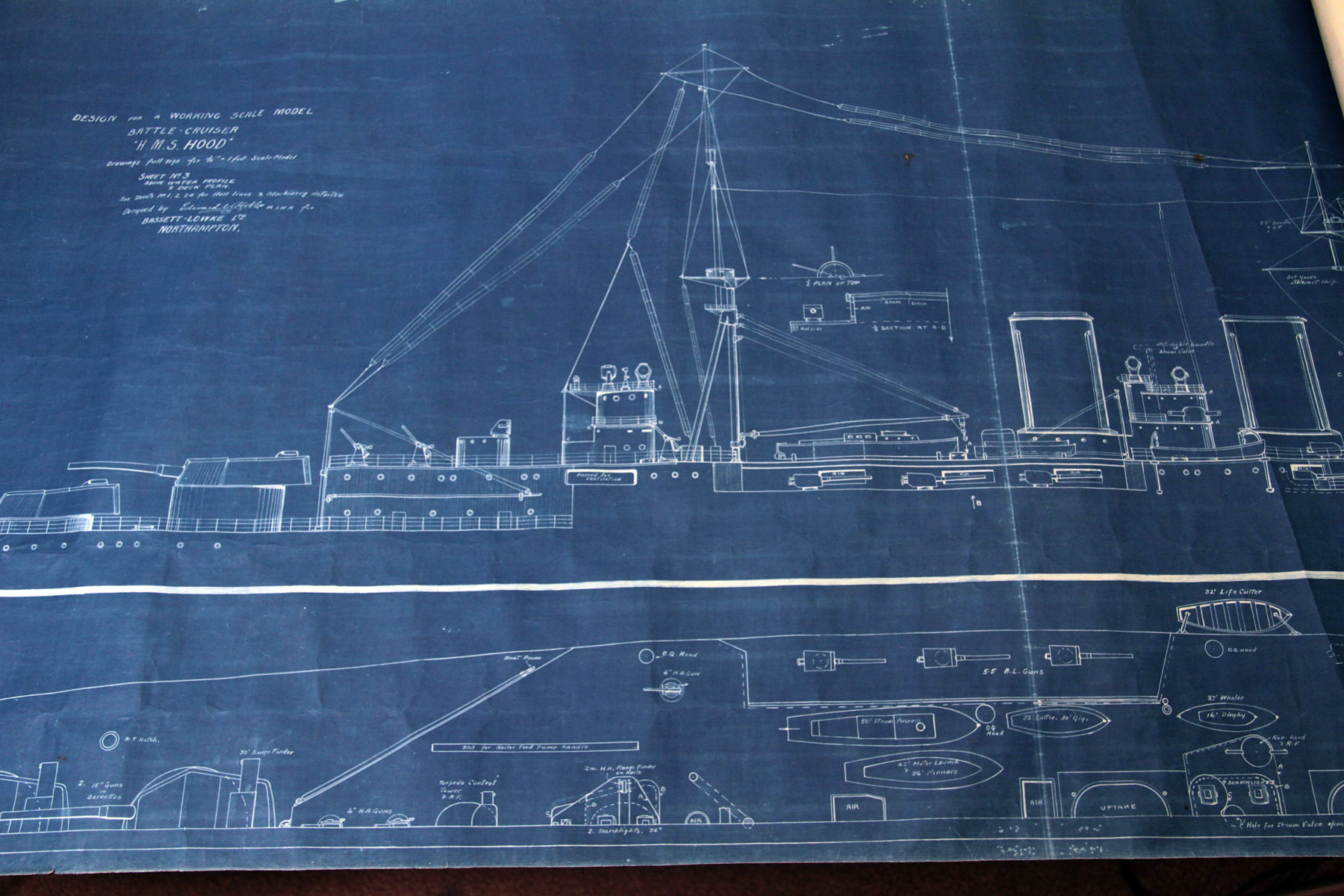

The original blueprints of the Hood, derived from the originals, for Bassett-Lowke Models c1928 were sold at auction recently.

In the end, HMS Hood was started at John Brown, Clydebank, named after Admiral Samuel Hood, 1st Viscount on 1 September 1916. She was launched on 22 August 1918 and completed on 15 May 1920. The HMS Anson (named after Admiral of the Fleet George Anson, 1st Baron Anson) was laid down at Armstrong Whitworth, Elswick on 9 November 1916. Work was suspended on 9 March 1917 and she was cancelled by 27 February 1919.

HMS Howe (named after Admiral of the Fleet Richard Howe, 1st Earl Howe) laid down at Cammell Laird, Birkenhead on 16 October 1916, same fate as the Anson. And HMS Rodney (named after Admiral George Brydges Rodney, 1st Baron Rodney) was laid down at Fairfield, Govan on 9 October 1916, same fate as the two others.

Design of the HMS Hood

We will not go though all the descriptions of the hull and compartmentation which are basically those of the admiral class, but with differences in armour design and armament:

High defintition Profile drawing (wikimedia commons) as it was in 1921.

Powerplant of the Hood

The Hood’s propulsion system comprised four propellers, connected by Brown-Curtis geared steam turbines consisted, fed by 24 Yarrow boilers. The As designed this powerplant could deliver 144,000 shaft horsepower (107,000 kW). Top speed as designed was 31 knots (57 km/h; 36 mph). Sea trials in 1920, showed a total output of 151,280 shp (112,810 kW), allowing her to reach 32.07 knots (59.39 km/h; 36.91 mph). For endurance, she carried 3,895 long tons (3,958 t) of fuel oil. Theoretical range was 7,500 nautical miles (13,900 km; 8,600 mi) at a reduced speed of 14 knots (26 km/h; 16 mph).

Armament

Main artillery

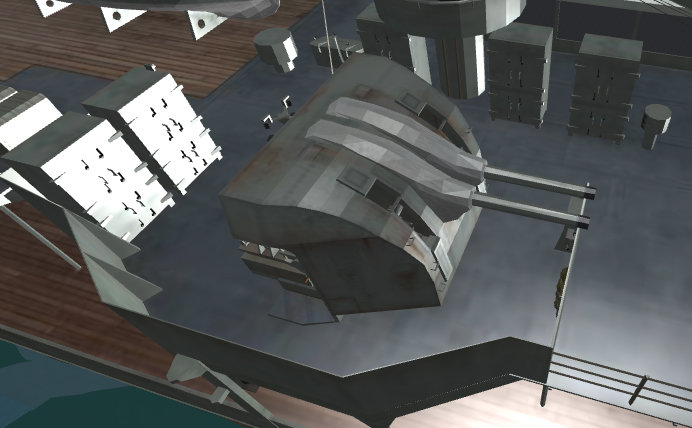

The Hood carried eight 42-calibre BL 15-inch Mk I guns. They were mounted in hydraulically powered twin gun turrets and each could depress and elevate, respectively, from −5° to +30°. Each barrel fired a 1,920-pound (870 kg) shell at 30,180 yards (27,600 m) in max elevation. 120 shells were carried for every gun. These turrets were designated ‘A’, ‘B’, ‘X’, and ‘Y’ in service.

Secondary artillery

The Hood’s secondary artillery comprised at the origin a dozen of 50-calibre BL 5.5-inch Mk I guns. Each were provided with 200 rounds. They were fitted on single-pivot mounts, shielded, rather than in casemates as usual for British battleships, and fitted along the upper deck and forward shelter deck, opened but protected. They were all protected on three sides by a shielding (see protection figures). Each fired a 82-pound (37 kg) shell to 17,770 yards (16,250 m) at maximal elevation.

Since they were placed relatively high, they were rarely “wet” and could fire in any weather, little affected by waves and spray. Two on the shelter deck were temporarily replaced by QF 4-inch Mk V AA guns in 1938 and removed in 1939. However all these guns were removed during the 1940 refit.

Anti-aircraft artillery

The original AA armament comprised four QF 4-inch Mk V guns in single AA mounts. In the early 1939 refit, they were joined by four twin mounts, each with 45-calibre QF 4-inch Mark XVI dual-purpose guns, also standard in many modernized RN warships (such as the C-class cruisers conversions). This single guns were removed later this year while three more twin Mark XIX mounts were added in early 1940, including one on the aft tip of the weatherdeck. All these turret mounts were capable of a +80° elevation. Theis gave them a maximum ceiling of 39,000 ft (12,000 m), and a range of 19,850 yards (18,150 m) against surface targets. The Mk XVI gun fired twelve 35-pound (16 kg) HE shells per minute at a 2,660 ft/s (810 m/s).

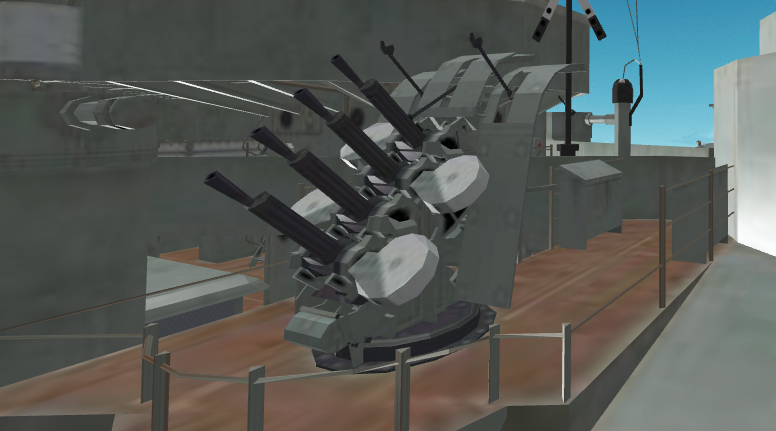

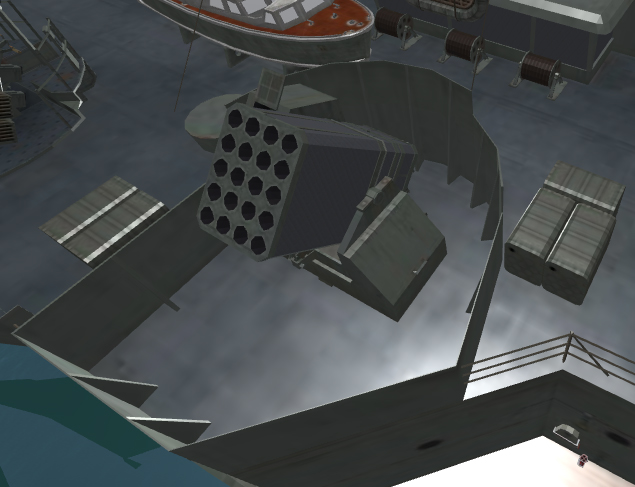

In 1931, the Hood received two 8-barrel 40-mm (1.6 in) QF 2-pounder Mk VIII better known as “Pom-Pom”. They were added on the shelter deck abreast of the funnels. A third mount was added in 1937. All could elevate to +80°, at a distance of 3,800 yards (3,500 m). Their rate of fire was 96–98 rpm. Each round weighted 0.91-pound (0.41 kg), exiting the barrel at 1,920 ft/s (590 m/s).

The third and lightest type of AA weaponry installed on board consisted in two quadruple mountings, Vickers 0.5-inch (12.7 mm) Mk III machine gun. The barrels were mounted on top of each others. Th first were mounted in 1933, followed by two more in 1937. They could elevate to +70°. This gave them a maximum range of around 5,000 yd (4,600 m), but it was really effective up to 800 yards or 730 m. These Vickers heavy machine guns fired a 1.326-ounce (37.6 g) bullet at 2,520 ft/s (770 m/s).

Another layer was added to the protective AA bubble in 1940, in the shape of five rocket launchers. Each carried a serie of twenty 7-inch (180 mm) rockets. These rockets were a unusual AA solution: When fired, they carried out a steel cable, kept aloft by parachutes. These cables were there to snag aircraft, drawing up a small aerial mine, which would detonate on the aircraft. This was a variant of the infamous “Z battery” proposed by Projectile Development Establishment at Fort Halstead in Kent and backed by Prof.

Lindemann and an enthusiastic Churchill in June 1940. The rockets were propelled by a special solvent-free cordite and in 1942, 2.4 million rockets were being produced annually, each with a 500 foot cable (153 m) and a mine. However the system as deployed during the battle of Britain was somewhat disappointing, and only a naval version deployed at RAF Kenley shoot two Dornier-17. Most ended with the Home Guards. In the Royal Navy, they were deployed at first in 1940s refitted or modernized ships, mostly capital ships, but ended in the merchant marine.

Torpedo armament

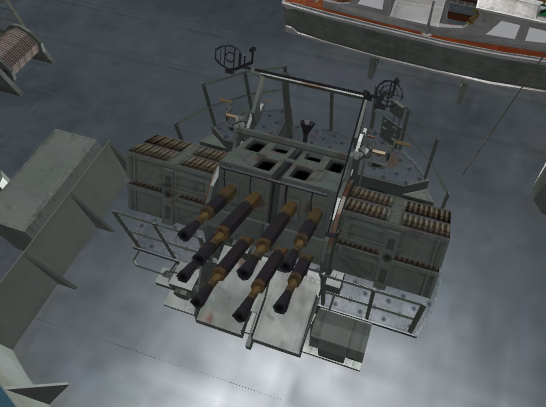

The HMS Hood carried a rather generous array of fixed 21-inch (530 mm) torpedo tubes, three on each broadside. Two were submerged near ‘A’ turret’s magazine and four were placed above water abaft the rear funnel. Each Mk IV torpedo carried a 515 pounds (234 kg) TNT warhead. They could be setup to two speed and range levels, at 25 knots – 13,500 yards (12,300 m) or 40 knots – 5,000 yards (4,600 m). 28 of these Mark IV torpedoes were carried.

The concept of capital ships carrying torpedoes could seems strange as they lacked the agility to be effective carriers, but the idea was to fire salvoes in battle lines: Indeed they were intended to be fired against a long line of ships, like at Jutland, this line was about 12,000 yards long, with a fair chance that some of these would effectively hit the last battleships in line due to the range and distance. This tactical factor was very much respected in WW1 and indeed at Jutland capital ships fired a total of 21 torpedoes at one another, but without scoring a single hit. The only occurrence in WW2 was HMS Rodney against the Bismarck on 27 May 1941, mostly to finish her off, but not scoring a hit. In the Interwar years therefore, torpedo tubes were generally removed from battleships.

Fire control and computing

Hood has two fire-control directors, one mounted above the large conning tower under an armoured hood, housing a 30-foot (9.1 m) rangefinder. The other was placed on the tripod mast fighting top, above the fire control bridge, and housing a lighter 15-foot (4.6 m) rangefinder. The four turrets also had each a 30-foot (9.1 m) rangefinder (see below).

Main turret individual rangefinders (lightened up)

The secondary armament was controlled by bridge directors, each side. They were reinforced by two additional control positions placed on the fore-top, and each housed a 9-foot (2.7 m) rangefinder. These were 1924–25 additions. The AA battery was controlled by a simple high-angle 6 ft 7 in (2 m) rangefinder placed on the aft control position and fitted during the short 1926–27 overhaul. The torpedo tubes were controlled by towers fitted on the weatherdeck, and each housing a 15-foot (4.6 m) rangefinder. There were three of them, two amidships the main control tower and a third on the centreline, abaft the aft control position.

In 1929–31 was installed the high-angle control system (HACS), Mark I director. It was placed on the rear searchlight platform. It was followed by the addition of two director positions for the “pom-pom” AA guns. They were placed at the rear of the spotting top. The 5.5-in control positions and rangefinders were of course removed with the guns themselves in the 1932 refit and two years later, the “pom-pom” directors were relocated on the 5.5-inch former position (spotting top) and signal platform, while the projectors were relocated.

In 1936, these “pom-pom” directors were placed this time on the rear corners of the bridge, ahead of funnel smoke while another director was added on the rear superstructure. It was placed abaft the HACS director two years later. The HACS system was modernized also: Two Mark III directors were placed on the aft end of the signal platform in 1939. The rear Mark I director was also upgraded to a Mark III. During the HMS Hood’s last refit, a Type 279 air warning radar and Type 284 gunnery radar were fitted on the top tripod mainmast. However this Type 279 radar lacked its receiving aerial and could not be used at the time she went into action.

Hood’s speed trials

Protection

Hood’s armour scheme was based on the HMS Tiger originally. It consisted in a 8-inch (203 mm) waterline belt. However this armour was not flat but angled outwards 12° from the waterline. This made a sloped part, increasing artificially its thickness in relation to flat-trajectory shells. However this added a vulnerability to plunging shells, exposing more the weaker deck armour. So by late 1916 as lessons from Jutland were digested, some 5,000 long tons (5,100 t) of armour were added but at the cost of deeper draught. This was achieved by making the existing armour thicker. In total protection accounted for 33% of the ship’s displacement, quite a treat for a British capital ship, more so for a battlecruiser, but still less than German designs such as 36% on the battlecruiser SMS Hindenburg.

The armoured belt had face-hardened Krupp cemented armour, in three strakes. The main one was 12 in of 305 mm thick between the outermost barbettes, going down to just 5-6 in or 127-152 mm on both ends. The bow and stern were left unprotected. The middle armour bel was 7 in or 178 mm thick but thinned to 5 in abreast ‘A’ barbette. The upper belt was 5 in or 127 mm thick amidships starting from the ‘A’ barbette, and completed aft by a short 4-inch (102 mm) extension.

Hood’s speed trials, warships today 1936.

Gun turrets and their barbettes belows were protected by 11-15 in or 279 to 381 mm, also with KC armour. Turret roofs were just down to 5 in. Decks were protected by high-tensile steel plates, with the forecastle deck just 1.75-2.0 in (44 to 51 mm), the upper deck 2 in (51 mm) over the magazines down to 0.75 inches (19 mm) and the main deck 3 inches (76 mm) over the magazines but just 1 in (25 mm) elsewhere but with 2-iin slopes, meeting inside the bottom of the main belt. The lower deck was 3 in thick, covering the propeller shafts, the magazines (2 in) down to 1 inch elsewhere. This several folds were design to absorb the energy of a penetrating round, exploding prematurely.

The main deck armour was added first, requiring to retire four 5.5-inch guns and their ammunition hoists. Despite of this, Live-firing trials with the new 15-in APC (Armour Piercing, Capped) shell against a mock-up showed her vitals cud be penetrated through the 7-in middle belt and slope. Therefore it was asked to better protect the forward magazines with 5-6 in in July 1919. The submerged torpedo tubes were removed for compensation, and the aft torpedo-control tower was to be left with just 25 mm walls. But this was never carried out fully. The anti-torpeo protection comprised a 7.5-foot (2.3 m) high torpedo bulge. It went for most of the side between barbettes, divided into an empty outer compartment, inner compartment with a serie of water-tight “crushing tubes” and backed by a 1.5 in torpedo bulkhead.

HMS Hood in 1924

Onboard aviation tests

HMS Hood was given flying-off platforms on ‘B’ and ‘X’ turrets. They could operate the Fairey Flycatcher fghter. However they were retired in 1929–31. Instead a trainable and folding catapult was installed on the quarterdeck. A crane to recover the unique Fairey IIIF from No. 444 Flight RAF. In the West Indies in 1934 the catapult was shown only operating in calm seas. Therefore catapult and crane were removed in 1932.

Construction

Ordered during the war, even before the Battle of Jutland (March 1916), Hood’s keel was laid in September 1916, and the ship was launched in John Brown on August 22, 1918. She was however completed after the war, accepted in active service by May 15 1920. Compared to the previous Repulse, he was a perfect example of the arms race that prevailed at the time between naval superpowers and for which the Treaty of Washington (1922) forced to end. This treaty also mechanically led to the cancellation of the Admiral serie, for the other 4 sister-ships which would have been commissioned otherwise in 1922-24.

Construction of Hood began at John Brown shipyards in Clydebank (Scotland) on 1 September 1916. As a result of the Battle of Jutland, 5,000 tons of extra armour and bracing were added while the deck protection was flawed—spread over three decks. The idea was to detonate incoming shells on impact with the top deck and absorbing its remaining energy being with the next two decks. This solution was as bright as it is today. It’s the principle of spaced armour, as used by the space station to protect it for incoming space debris, while preserving weight.

However soon were developed in response time-delay shells, at the very end of 1918, so this scheme became less effective. So any incoming shell would explode deep inside the ship anyway. In addition, this overweight made the ship “plough” in heavy weather, making her very wet, and with a highly stressed structure which perhaps explained how she broke in two so easily.

HMS Hood was launched on 22 August 1918 by the widow of Rear Admiral Sir Horace Hood, great-great-grandson of the Admiral Samuel Hood. The latter honored his family lineage by his fatal service in command of the 3rd Battlecruiser Squadron at Jutland. His flagship was the HMS Invincible, one of three battlecruisers lost during the Battle. The busy slipways of John Brown’s shipyards forced however the Hood sail for Rosyth for completion and fitting-out in January 1920. She made extensive sea trials, showing better speed and output than design specs. She was commissioned on 15 May 1920. Her first Captain was Wilfred Tompkinson. Total cost for British Taxpayers was £6,025,000. That would be £334,483,551.12 today with the inflation.

The Hood was by speed, armament, and size de facto the most powerful warship on earth and stayed so until ww2. In this 20 years was the queen of the Royal Navy, the “mighty hood” for the press and general public, the uncontested knight champion of the oceans and guarantee that the Empire were well protected. She was regarded by all admiralties, including the USN, as THE finest-looking warships ever built, and in the end in her role as an ambassador, symbolising the might of the British Empire itself.

But as battle cruiser the brainchild of the admiralty, but above all war veterans Sir John Jellicoe and David Beatty, her protection remained lower than the super-battleships which will be delivered in the late 1930s. But this type of ship could be the most striking case of a risky duel with a battleship from a distance, with only safeguard as using a good range of fire and adequate speed. In the end the situation was desperate enough to send a battlecruiser and an unprepared battleship barely commissioned to fight the largest battleship afloat. She was not ready to fight the Bismarck, a late 1930s fast battleship marrying the “best of both worlds” in a terrifying package and the result was stunning.

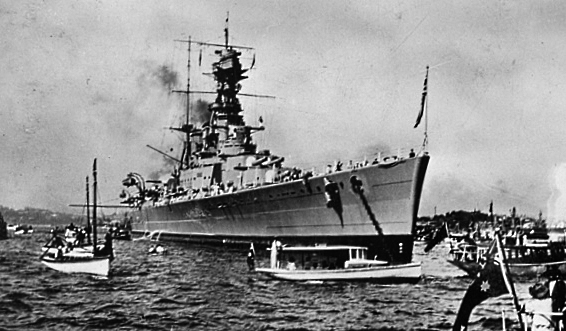

HMS Hood in Sydney Harbour

Interwar Career

After her commission in 15 May 1920, HMS Hood assumed the role of flagship of the Battlecruiser Squadron of the Atlantic Fleet, under command of Rear Admiral Sir Roger Keyes. Her first cruise was in Scandinavian waters under Captain Geoffrey Mackworth. The next two years shos would visit the Mediterranean, showing the flag, training with the Mediterranean fleet. Afterwards, she sailed on a cruise to Brazil and the West Indies.

HMS Hood entering Vancouver

Her additional armour showed ill-effects as her draught was increasing by 4 feet, freeboard lowered, and front deck very wet as a result. She required a secondary wave-breaker abaft the second turret. At full speed and in heavy seas it was shown that water flowing over the ship’s quarterdeck entered the mess-decks and living quarters through ventilation shafts. So she ended nicknamed “the largest submarine in the Navy”. This had the unexpected ill-effect of outbreaks of tuberculosis cases, which were attributed to this persistent dampness and poor ventilation. In 1919 the Hood’s crew comprised 1433 men as a squadron flagship but in 1934 and regular service this was reduced to 81 officers and 1244 men, which shall be considered as the “normal” complement.

Graf Spee, HMS resolution and Hood in the background at 1937 king Georges V coronation ceremonies at Spithead

Captain John im Thurn took his duty on board, and the Hood departed with the battlecruiser Repulse and Danae-class cruisers (1st Light Cruiser Squadron) for a world cruise. They headed west to east via the Panama Canal, starting in November 1923. Visiting the dominions and recall them to the necessary British sea power, trying to secure financial support, but also to develop shipbuilding and create new facilities. The campaign lasted for 10 months and ended in September 1924. Hood visited South Africa, India, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and other colonies as well as the United States. In Australia, by April 1924, the squadron escorted the battlecruiser HMAS Australia to her last voyage, scuttled at sea in compliance with the Washington Naval Treaty.

The squadron also visited Lisbon in January 1925 (Vasco da Gama celebrations) and joined the Mediterranean for joint exercises, the annual winter training whill last for a decade. Captain Harold Reinold relieved Captain im Thurn on 30 April 1925, and later Captain Wilfred French in May 1927. At last, HMS Hood returned in drydock for an overhaul and a refit, which lasted from 1 May 1929 to 10 March 1931. Mostly this concerned minor armour changes and fire directors, AA. Afterwards she resumed at the head of the battlecruiser squadron under Captain Julian Patterson. At the fall of 1931, Hood’s crew participated in the Invergordon Mutiny, over pay cuts resulting of the crash of wall street and budget restrains. The battlecruiser squadron cruised in the Caribbean cruise by early 1932, before returning home for a new refit (31 March-10 May 1932) at Portsmouth. Captain Thomas Binney took command on 15 August 1932 and the battlecruiser resumed her usual winter training sessions in the Mediterranean alternated with home waters in spring and summer. Captain Thomas Tower took his place in August 1933 while the ship seen her secondary and AA fire-control directors rearranged during her short 1 August-5 September 1934 refit.

The 1935 incident

The only incident reported, happened on her way to Gibraltar. She was rammed in the port side quarterdeck by the Renown on 23 January 1935. Damage was limited to her left outer propeller but this left a 18-inch (460 mm) dent in hr hull, with a few hull plates knocked loose. Repairs were made at Gibraltar, enough to allow her to head for Portsmouth. Repairs ended in May 1935, meanwhile both captains were court-martialled as well as the squadron commander Rear Admiral Sidney Bailey. Captain Sawbridge of the Renown was relieved of command but he was later reinstated the the admiralty that led another enquiry, criticizing Bailey for his unclear signals during the manoeuvre that led to the disaster.

HMS Hood in August 1935 participated in King George V’s Silver Jubilee, the great Fleet Review at Spithead. She was at Gibraltar when Second Italo-Abyssinian War broke up, under Captain Arthur Pridham. Hood was back in portsmouth for a brief refit lasting from 26 June to 10 October 1936. She was transferred to the Mediterranean fleet on 20 October as the Spanish Civil War broke up, escorting British merchantmen into Bilbao, under the vigilant eye of Nationalist-held Almirante Cervera. Hood was later refitted at Malta until December 1937. Her submerged torpedo tubes were removed. Captain Harold Walker took command in May 1938. Later the ship headed for Portsmouth in January 1939 for a long overhaul. It ended in 12 August. There were also another overhauls in 1939 and 1940, after the war broke out.

Colored photo of the Hood in Malta, during one of her numerous winters in the Mediterranean.

The projected great refit of HMS Hood

Hood was due to be modernised in 1941. The admiralty was fully aware of the age of the design and compromises in protection and they wanted to bring her up to more modern standards, at least similar the modernised Queen Elisabeth and Resolution class fast battleships. The plan included the fitting of received new, lighter turbines and boilers, eight twin 5.25-inch dual purpose gun turrets, six octuple 2-pounder Bofors “pom-poms”. Instead of a 5-inch upper-armour strake, the deck armour would have been greatly improved.

Also the ship lacked an aircraft for reconnaissance and a catapult would have been fitted across the deck. Also the remaining surface torpedo tubes would have been removed, the heavy conning tower removed and the bridge completely rebuilt in the new style seen on the Queen Elisabeth, Malaya and Warspite. Major survey would have been made also of the hull to detect any fatigue due to extensive service in the interwar. Unfortunately this never happened.

With the outbreak of World War II the Hood was too precious to be put out of commission, and never received the scheduled modernisation. Meanwhile, for the battlecruiser Renown and several of the Queen Elizabeth-class battleships it was already too late and completion of their modernization was resumed. Reports made clear however that the Hood’s condensers were in bad shape and leaking. The output from the fresh-water evaporators was severaly reduced, and as a result the crew had no water left to wash and bathe or even heating the mess decks. Steam pipes were really worn out. This steam output reduction has another consequence, leaving the ship unable to reach her designed speed anymore, which gave her no advantage in return for her weaker protection.

Operation Catapult

The Hood only concessions to progress included a more efficient AA but her artillery and fire direction system was grossly obsolete. The Hood began a series of atlantic patrols in search for possible breakouts of German fleet between Iceland and the Norwegian coast. She rallied force H in the Mediterranean, taking part in Operation Catapult in August 1940. The great irony of this war that her first shots in anger were against the French fleet at anchor, in Mers-el-Kebir. As reported by sub-Lieutenant philip, HMS HOOD was the flagship of the Fleet and leading ship of the line, with the other two Battleships disposed astern. They were backed up at some distance, out of range, by HMS ARK ROYAL.

As gunnery range decreased to nine miles, the French fleet was still partially obscured by the jetty. With no alternative, the possibility that the French could leave the harbour it was ordered to open fire at this close range. The French waited until they could see the fall of the first salvo, in the harbour and the mole. Shore batteries then opened fire. Then they were followed by the various warships in the harbour, concentrating on the Hood. The whole action lasted for less than fifteen minutes. But the destruction was terrible. French fire was very heavy and accurate but the Hood was not hit. At 20h 53 it was ordered to cease fire. More on this event.

Home water service

Back to Scapa flow HMS Hood remained there in case of a German invasion in the Channel, Operation Seelowe was indeed a very real prospect in the summer. Prince of Wales joined her, freshly commissioned. The threat of an invasion evaporated with the success of the Battle of Britain, but the German fleet was about to receive an ace of its sleeve. A dark and threatening, massive, nightmarish one: The KMS Bismarck. The 50,000 tons battleship, pride of the Kriegsmarine, was commissioned on 24 August 1940, and spent the next month to train and iron out the few defects detected. In March and April she was prepared carefully by the Oberkommando der Marine or OKM headed by Admiral Erich Raeder, to act against British convoys in the Atlantic. As designed, she would be able to destroy any escort at sea. Indeed the two Scharnhorst-class battleships based in Brest just completed Operation Berlin which was seen as a good operation, leaving hope to be reinforced by the Bismarck, making a very tough squadron to defeat, too close to home for comfort (for the British admiralty). Well informed by spy networks, progresses of the Germans were known to make the Bismarck ready for her first campaign in May.

Battle of Denmark strait

1960 British classic, now open source “sink the bismarck”. The film would certainly deserve a modern version, with the levels of CGI we know and a more “on board action” oriented script it would be awesome. An idea for a release in May 2021. Contact me if you are interested.

In May 1941, the threat became very real. The Bismarck accompanied by Prinz Eugen made it into the Atlantic, after crossing through the Skagerrak. The following events are well rendered by the 1960 movie “Sink the Bismarck”. British Admiralty’s chief of operations, Captain Jonathan Shepard studied his limited options to intercep the German squadron before making it into the Atlantic. The German plan was to repel any intercepting ships and fall onto British convoys in the northern atlantic and then making it back east to Brest for further operations. She was intercepted by the Hood group, apparently on paper with some advantage. But in reality the battle group was not up to the task, due to the limitations of the Hood both in protection and fire control, whereas HMS Prince of Wales’s crew was too ‘green’ and not yet fully operational. Workers of the yard onboard to try to iron out problems with her turrets until the last minute !.

But Churchill’s order was clear: To “sink the Bismarck” whatever the cost maybe. When Bismarck’s position was confirmed, Hood and Prince of Wales were sent out in an interception course. Several other groups of British capital ships were also scrambled, including those protecting the convoys in order to catch them before they could break into the Atlantic. HMS Hood was under command of Captain Ralph Kerr, flying the flag of Vice-Admiral Lancelot Holland. The Norfolk & Suffolk spotted the Bismarck and PE (Prince Eugen) on 23 May. Holland’s ships were set to intercept the Bismarck in the Denmark Strait, between Greenland and Iceland sometime on 24 May.

But Churchill’s order was clear: To “sink the Bismarck” whatever the cost maybe. When Bismarck’s position was confirmed, Hood and Prince of Wales were sent out in an interception course. Several other groups of British capital ships were also scrambled, including those protecting the convoys in order to catch them before they could break into the Atlantic. HMS Hood was under command of Captain Ralph Kerr, flying the flag of Vice-Admiral Lancelot Holland. The Norfolk & Suffolk spotted the Bismarck and PE (Prince Eugen) on 23 May. Holland’s ships were set to intercept the Bismarck in the Denmark Strait, between Greenland and Iceland sometime on 24 May.

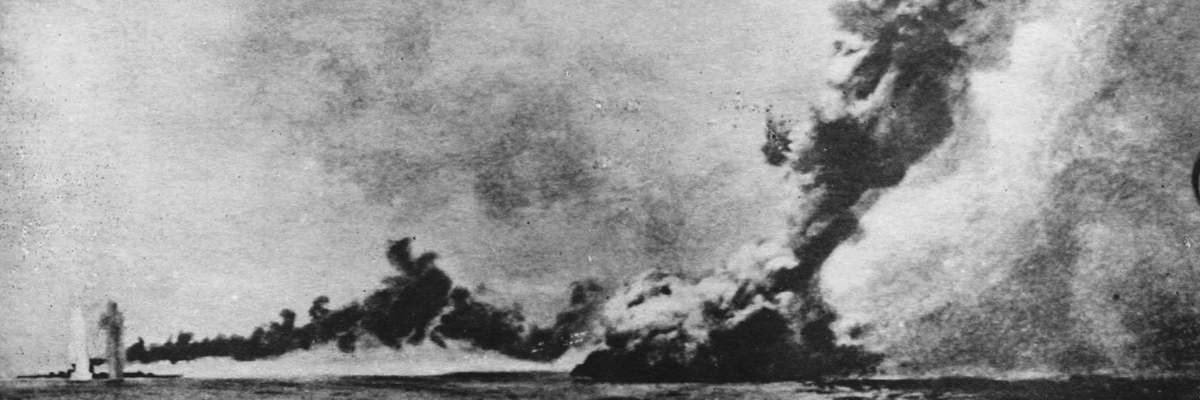

Eventually the British squadron spotted the Germans at 05:37, four hours ahead of local time so shortly after dawn. However at that time, the Germans were already on war foot, the latest Prinz Eugen’s hydrophones detected theit high-speed propellers southeast of their position. Despite of this, the British opened fire first, at 05:52. Hood engaged Prinz Eugen, believing she was the Bismarck, as the lead ship in the formation (it is said the choice of this cruiser by Lutjens, which silhouette was reminiscent of the hood was no accident). The latter returned fire three minutes later and both ships concentrating on the Hood. KMS Prinz Eugen probably hit her first, set ablaze the Hood’s boat deck between the funnels. This started a large fire, quickly reaching the ready-use AA ammunition and Z-battery stockpiles of rockets. There could have been transmission but the enquiry made on the wreck rediscovered in recent years stayed inconclusive on this chapter.

Before 06:00 however, HMS Hood made a 20° turn to port allowing her to align her aft turrets when she was hit again on the boat deck, this time by the Bismarck. It was at that time her fifth salvo, coming in plugin fashion across 16,650 metres (18,210 yd). The spotting top was destroyed, and suddenly a massive jet of flame burst out of Hood near the mainmast. It was followed by a humongous magazine explosion, that properly stunned all ships and crews present. The blast wave reach them soon, and the explosion ripped apart the aft section and broke the whole section of the hull. Her prow almost vertical was for all the last sight of HMS Hood, which was gone under the waved under just three minutes.

A survivor’s sketch (now exposed at the British RN Historical Branch Archives) gave the last position 63°20′N 31°50′W. HMS Hood went down in two parts, stern first, carrying with her 1418 men aboard, but three survived: Signalman Ted Briggs, Able Seaman Robert Tilburn, and Midshipman William John Dundas, rescued about two hours after by the destroyer Electra in freezing water. The explosion and rapid sinking came as a shock even for the Germans which expected a longer fight, given the reputation of the British flagship. We can only guess the mood in the Prince of Wales. Both German warships soon turned on her and the British battleship, struggling to have the artillery and turrets properly working and rapidly hit, was obliged to run away. The whole affair sounded like an humiliation of the Royal Navy, and shook to the core public opinion.

It riveted the press, general public, house of commons and entire Royal Navy staff for the next hours, following the fate of the German battleship. All had only one word in their mind and lips: Revenge for the Hood. Against all odds and a rocky turn of events, the proud Bismarck was sent to the bottom of the Atlantic after trying to reach France, hammered without compassion by the British battleships which came to the fray. The Hood was avenged. But since then, a mystery long followed the dramatic end to the Navy’s symbolic flagship.

Painting by Edward Tufnell

No end (yet) to the mystery

In 2001 was rediscovered the wreck of HMS Hood, which was the subject of a report from the BBC. However, a thorough examination of where the explosion began had not solved the riddle of the exact cause of the explosion. Indeed, the descriptions and drawings made of the explosion put the finger on a problem: It had started far from the rear ammunition bay. There was virtually nothing in this place likely to provoke it, or at least not in this magnitude. To date the hypothesis are going wild but truth always escaped specialists and authors.

HMS Hood just after the tremendous explosion that wrecked her, and the Prince of Wales passing in front. The magnitude of the event shook everybody, including the Germans.

Specifications |

|

| Dimensions | 242 m long, 27.4 m wide, 9.7 m draft (full load). |

| Displacement | 42 670 tonnes standard -45 200 tonnes Fully Loaded |

| Crew | 1477 |

| Propulsion | 4 propellers, 4 Brown-Curtis turbines, 24 Yarrow boilers, 120 000 hp. |

| Speed | Top speed 31 knots, 8000 nautical mile radius 12 knots. |

| Armament | 8 x 381 mm (4×2), 14 x 102 mm (7×2) DP, 8 x 40 mm AA (2×8), 1 rocket launcher. |

| Armor | Belt 300 mm, decks 100 mm, range-finders 152 mm, turrets 380 mm, citadel 130 mm, blockhaus 280 mm. |

Links/sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Hood_(1920)

Conway’s all the world’s fighting ships 1922-1947

google books – WW2 weaponry Encyclopedia

https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/bismarck-vs-hood-how-hitlers-most-deadly-battleship-sunk-pride-royal-navy-28347

https://nationalinterest.org/feature/battlecruisers-the-glass-jawed-warship-failed-13828

https://www.plasius.de/wracks/schlachtschiffwracks/

Videos Corner

//www.youtube.com/watch?v=AXBODH8tkeE

//www.youtube.com/watch?v=4_jDaUSSPhc

Models Corner

1-200 Trumpetert HMS-Hood

amazon.co.uk Trumpeter HMS-Hood-1/350

amazon.com Trumpeter-Hood 1/700

revell.de hms-hood 100th-anniversary 1/700

cornwallmodelboats.co.uk Heller HMS-Hood 1/400

Italeri hms hood 1/720

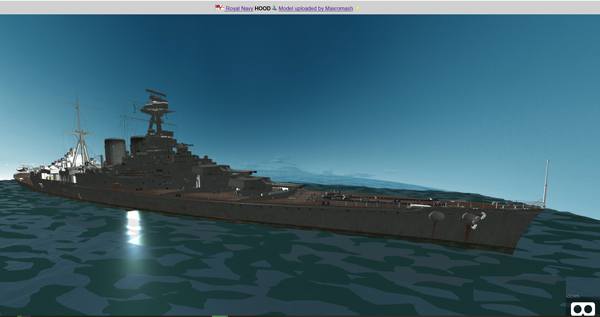

3D Corner

sketchfab – ThomasBeerens (Free DL)

sketchfab model foom WoW Free DL

Author’s illustration of the hood in 1941

What the Hood could have been

Photoshopped view of HMS Hood as planned for refit (From Quora, unknown author)

IF the Hood has been for example hit by a magnetic mine or hit another ship and damaged, so in a drydock in May 1941 (and missed the battle), it is dubious at first the admiralty had sent the unprepared Prince of Wales alone and the famous battle could have never been fought. The Bismarck took no serious hit during the actual battle so its weight on the following event was negligible compared to the action of naval aviation.

So let’s imagine that the admiralty suddenly get a dose of realism about the actual potential of the Hood and given its precious status ordered a reconstruction and modernization a la Renown. It could have ended in fall 1942 (with the highest priority), but with a ship significantly improved in protection, gunnery targeting and fire control and AA.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign

In 1938 Director of Naval Construction Sir Stanley Vernon Goodall warned that HMS Hood was in poor mechanical condition and that her thin deck armour made the ship ‘unfit for service’. Goodall proposed a number of new armouring schemes but concluded that Treasury limits on spending would rule out any upgrade.