United Kingdom (1937-55)

United Kingdom (1937-55)Dido, Bonaventure, Naiad, Phoebe, Cleopatra, Charybdis, Euryalus, Hermione, Scylla, Sirius, Argonaut

The First Dedicated Royal Navy British AA cruisers

The Dido class were at first developed as conventional light cruisers, but in 1937 the designed evolved quickly as dedicated AA cruisers, whereas plans were made to convert vintage WWI vessels of the C and D class the same way in case of war to defend convoys. An ambitious plan of sixteen or even twenty was setup, but only the first eleven were completed as planned as their dual purpose turrets were highly critized. The next five were completed with a more conventional AA armament as the Bellona class. Nevertheless, completed until 1942, the Dido class were the first dedicated anti-aircraft British cruisers, moirroring the USN Atlanta class. They proved still very capable and active in WW2, three of these being sunk by U-Boats in convoy escorts.

Design & development

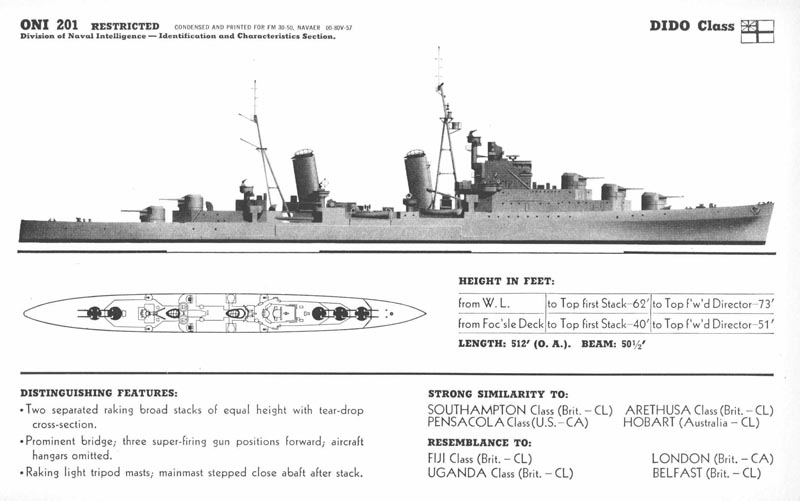

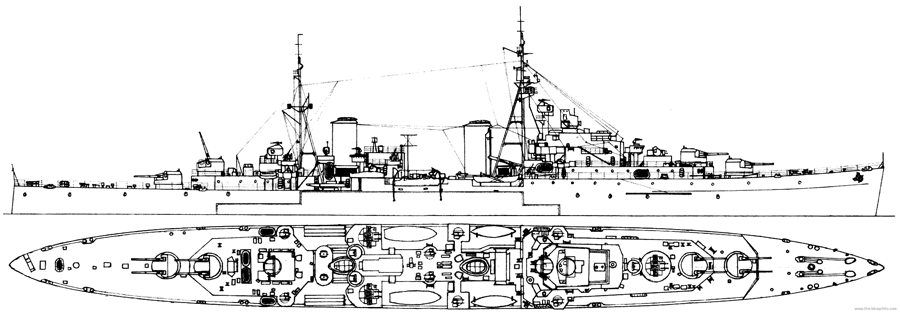

ONI 201 plate depicting the Dido class

ONI 201 plate depicting the Dido class

Genesis of the project

The idea of an anti-aircraft cruisers did not emerged before 1935, for convoy escort and fleet protection, and by that time it was widely believed that high altitude bombers was the main threat, so emphasis was made on heavy guns, with the benefit in that case of being dual-purpose. One of such caliber was the ubiquitous 5-inches in service in the USN. The Royal Navy at the time had no such caliber, the 4-inches being the closest, but lacking power for antiship tasks. Thus, the admiralty contacted Vickers for such a gun, at first to equip the new battleships of the King Georges V as main secondary armament, if possible with a semi-automated reloading system.

Until then, the RN possessed the 5.5″/50 (14 cm) BL Mark I as a naval gun (HMS Hood, Furious, Hermes, Cruisers Birkenhead and Chester) but it was not suited to be adapted and instead, work started in 1931 on a new model for cruiser and possibly destroyer use, which was the Experimental 5″ (12.7 cm) and the 5.1″ (13 cm) QF Guns. The 5.1″/50 (13 cm) QF Mark I was first developed as a versatile, high rate of fire and partly automated destroyer weapon, possibly to arme the aircraft carrier HMS Ark Royal. Two prototypes were manufactured for shore and “B” mount on the destroyer HMS Kempenfelt, a “C” class flotilla leader. It fired 108 lbs. (49 kg)but still on a manually-worked reload, too heavy to be development further.

Work around the weight conducted to a 70 lbs. (31.8 kg), and then 62 lbs. (28.1 kg) rounds, with a Muzzle velocity of 2,693 fps (821 mps) and 2,790 fps (850 mps) respectively, quite honorable and helping accuracy. Monobloc barrel and two piece barrels differienciated the prototypes and the mounting CP XIV, with a new cradle enabling 40° elevation.

These were further developed in the end of the 1940s as the 5″/70 (12.7 cm) QF Mark N1 and the 5″/62 (12.7 cm) QF Mark N1, and the very heavy 5″/56 (12.7 cm) QF Mark N2 in the 1950s, intended for next-gen AA guided cruisers. The whole program was cancelled in 1953 (src). Nevertheless in between, a new caliber was studied, soon after the 1931 prototypes, this time as a perfect dual purpose mount, as anti-aircraft threats were taken more seriously. It had the potential of both antiship defense at closer range, suitable as a secondary artilley on battleships, new and modernized, and aicraft carriers. The one chosen was eventually the 4-in (114 m) but it was recoignised it lacked power.

Thus, work started in 1935 on a Dual-Purpose (DP) intended as secondary armament for the King George V and Vanguard class battleship classes. It was considered the size allowed a heavy weight, still manually handled by an average gun crew. The gun itself was not too problematic to design and manufacture, but the gunhouse allowing its proper service, with a dedicated twin cradle, was designed a bit as a afterthought and proved cramped and not ergonomic.

Alongside, the idea of a dedicated AA cruiser emerged in a letter written in 1933 by the Director of the Tactical Division, Captain Tom Phillips, to the Commanders in Chief of the Home and Mediterranean fleets. He asked for their opinions about a small, 4,000 ton cruiser to replace vintage WWI C and D classes still in service, FY 1935+. At the same time, the Leander class were building for trade protection and the Arethusa class for fleet combat, both at a slight higher tonnage. Later, the ‘Towns‘ were specifically designed to face in Asia the Japanese Mogami class.

The Admiralty Board on its side was also aware of the age of the C-D cruisers and needs of the fleet, and looked at a cheaper alternative to the Arethusas. The Commander in Chief, Mediterranean fleet, expressed his desire of having a small cruiser which can work woth destroyer flotillas, so more for screening purpose and as leader. Its main armament was suitable to fight off enemy’s destroyers, usable as flotilla flagship and rallying point for a destroyer flotilla. The Town class in developed was way too large for this.

In 1934, the HMS Curlew and Coventry were the first modernized and converted as specialized Anti-Aircraft cruisers. They were entirely armed with 10-4” guns and “pompom” in large numbers. They re-entered service in the Mediterranean Fleet in 1935 and proved their worth during the Abyssinian crisis. Based on this report, the Admiralty received further demands for a cruiser with heavy AA firepower. Further design refinements went on until February 1935, when agreement was found on a small, cheap cruiser that can be produced in numbers allowing the full replacement of the “C” and “D” class FY 1937-40.

Their size was just large enough for fleet work, even in heavy seas, and allowing maximal firepower, while preserving speed and agility (to the expense of protection). It was established that ten of the new guns was ideal for all situations. Still, the new 4.5” which was now standard was considered too small for the size of the new cruiser and dual role, so that the 5.1” Dual Purpose gun under development at the time of the King Goerges V class was chosen “of the shelf”.

This the 5.1” gun rapidly was enlarged and modified as the 5.25” gun proposed for the King George V class, but soon the twin mount proved both was complex and heavy, still tests shown in preformed well in low

angle role.

By June 1936 an unnamed 5,300 tons design was approved by the admiralty, mounting a battery of ten 5.25” guns. Later a name was chosen, and like the C-D class they replaced, mythologic names adopted. “Dido” was the lead ship, and official class name in late 1936. These were not simple AA cruisers, but truly small cruisers with emphasis on Dual Purpose role, while the Admiralty wanted the 4.5” gun reserved exclusively for AA

purposes. Finalization of the design, based on teh Arethusa class hull and main arrangements, design proceeded swiftly. Engineers modified of course the fore and aft section to accomodate five wells for the artillery instead of three, and pushed back the bridge, which was heightened to dominate the second superfiring turret. Modifications were dones also to improve armour, and increase it. Top speed was to be moderate, and range defined to be just what was needed for any standard convoy escort, taking the Atlantic crossing as comparison.

Order, Construction, and Modifications

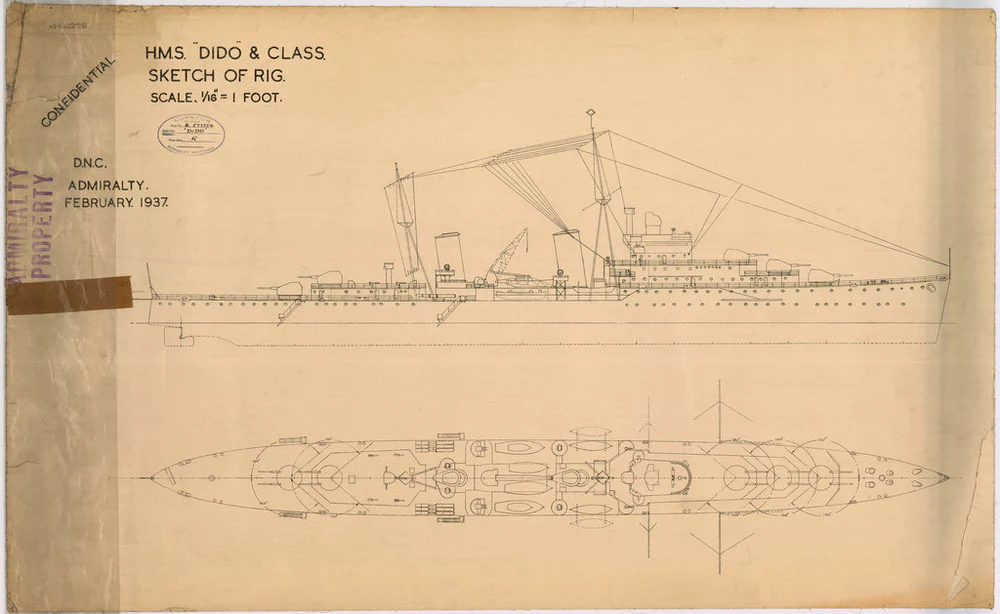

Original sketch of the Dido class and rigging plan

After the final design was approved, funds were obtained for a first order, a batch of seven in 1937, after being ordered by 1936. Five were in reality ordered in 1936: Dido, Euryalus, Naiad, Phoebe, Sirius, two in 1937: Bonaventure, Hermione: Three in 1938: Charybdis, Cleopatra, Scylla and six in 1939, Argonaut, Bellona, Black Prince, Diadem, Royalist, Spartan, making this the largest cruiser program since the First World War, as the international situation degraded. After all, they were intended to replace the ‘C’ class cruisers, mass produced in WWI as follow-up of the “town” class.

Given the pennant #37, HMS Dido was laid down eventually at Cammell Laird, Birkenhead.,But she was not the first one, neither launched or completed earlier, so it is somewhat surprising the class was named aft her. A convention amidst historians generally opted for the launch date as the lead name for the class. In that case it should have been HMS Phoebe, laid down earlier, and launched 25 March 1939. But based on completion, the date pointed to HMS Bonaventure. Indeed, the vessel intended for RCAN crews was completed the first, on 24 May 1940, but not laid down also the first (30 August 1937), as this was HMS Naiad, on 26 August. Based on the pennant alone, again, it was Bonaventure the first. I cannot find any explanation but a convention as the name was short and easy to remember.

Anyway, the first 1937 batch was ordered in seven yards: Cammell Laird, Birkenhead (Dido, 26 October), Fairfield, Govan (Phoebe, 2 September), Alexander Stephen and Sons, Glasgow (Hermione, 6 Oct.), Scotts, Greenock (Bonaventure, 30 August), Hawthorn Leslie, Hebburn (Naiad, 26 August), Chatham Dockyard (Euryalus, 26 October). In 1938, a single ship from the original batch was ordered, at Portsmouth Dockyard, Portsmouth (HMS Sirius, 6 April). 1939 saw the last batch of ten ordered, starting with HMS Cleopatra on Hawthorn Leslie, Hebburn on 5 January, then HMS Scylla in April at Scotts, Greenock, two at Cammell Laird, Birkenhead (Charybdis, Argonaut, on 9 and 21 November), Harland and Wolff, Belfast (Black Prince, 2 November), Fairfield, Govan (Bellona, 2 November and Diadem on 5 December), Vickers-Armstrongs, Barrow-in-Furness (Spartan, 21 December) and eventually the very last, at Scotts, Greenock, HMS Royalist, on 21 March.

While construction proceeded for five of those of the second batch, serious doubts had been expressed about the new dual purpose mounts and constructiion was suspended shortly for a redesign. Thus, part of the second batch of ten was modified: Five identical but with the second superfiring mount removed and replaced by a Bofors and other modifications, while the second group of five (renamed the Bellona group) was completely redesigned, eliminating the dual purpose mounts entirely, replaced by smaller, but trusted 4-in mounts. This led to a brand new class which will be seen later that year.

Eventually the class was split into three groups with the first (Dido, Euryalus, Naiad, Phoebe, Sirius, Bonaventure, Hermione, Cleopatra, Argonaut) all preserving the original design, and although completed with only four turrets, received the fifth later. The second group comprised Charybdis and Scylla armed with 4.5” guns and the third (Bellona, Black Prince, Diadem, Royalist, Spartan) had received instead a modified design with four 4-5.25” turrets only, reduced superstructures and extra AA. But by 1939, the hard-pressed British industry was unable to ramp up to war production level and for such large number of cruisers, was unable to produce turrets, fire control equipment, turbines, and reduction gearing. Delays amounted (Bonaventure was delayed for more than a year), aggravated by emergency choices, like reserving these turrets to complete the King George V class battleships first. Each of these five capital ships had eight of them aboard. They fared as poorly as the Dido in combat, as shown by the fate of HMS Prince of Wales in December 1941.

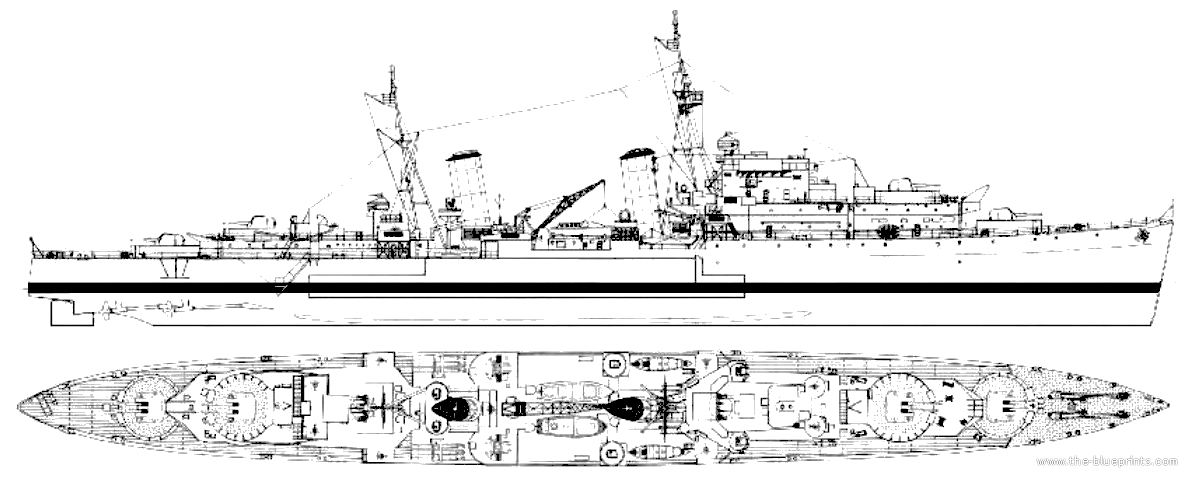

Final design

Once approved, the Design was quick in late 1936 and early 1937, as engineers took the basic hull of the Arethusa class,but with with 3 gun turrets forward and two aft and superstructures around. The bridge was higher as usual to clear ‘Q’ (or ‘C’) mounting and the fore funnel raked aft to reduce the fumes effects. Two funnels were adopted as for the Arethusa, and the internal arrangements, and engines, were still close to the same design, with also raked masts, tripod in order to minimize stays interfering with more complicated fields of fire.

Hull and superstructures design

HMS Naiad, general arrangement

The original design called for a seaplane and service crane installed like for the Arethusa between the funnels. However due to the weight of the tall superstructure, engineers insisted weight savings were necessary to save an already compromise stability. Therefore it was decided to replace it by two quad 2pdr pompoms, reinforcing the light AA defence instead. But the admiralty insisted to keep a powerful antiship weapon in the shape of two two triple torpedo mounts on deck.

Engineers tried to preserve the metacentric height by taking as many weight-saving measures they could:

-Welding of the forward sections instead of riveting

-Reduced number of shells

-Copper piping instead of steel

-No handing room between the magazines and turrets

-No spare gun barrels aboard

-Lighter High Angle directors.

The profile of the new cruiser was unmistakable, with a two-stage superstructure housing the dual purpose mounts, extended aft and supporting the bridge, one level higher compared to the Arethusa class. For surface targeting, a Mk IV director was installed on the bridge to serve the mounts and two high angle directors for AA fire were fitted in different locations: Above the bridge forward and aft of the mainmast so that AA could target two aircraft simultaneously. The aft HA director was dual purpose in case the main would be disabled, helping use the main artillery as backup, against air and surface targets.

Four service boats were located amidships, close to the fore funnel. This was completed, saving place and weight, by inflatable boats. The deck TTs were located further aft, with a limited traverse fore and aft. The bulk of AA artillery was also located amidships, starting abaft the bridge, and on either sides of the funnels and in the space freed by the absence of aviation. The choice of removing the latter had a reasoning: These vessels were not intended to act alone but in convoy as so, aerial reconnaissance would be provided by other vessels. The ship’s task was to be AA cover alone and torpedo tubes were intended as a last-ditch defence, reassuring the admiralty about her capabilities at closer range given the small caliber of her main artillery. Her armour was also thicker and better studied to resist 6 inch shells.

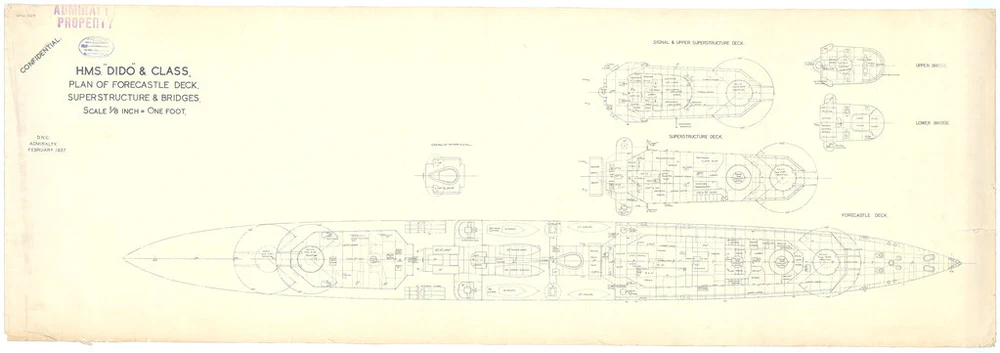

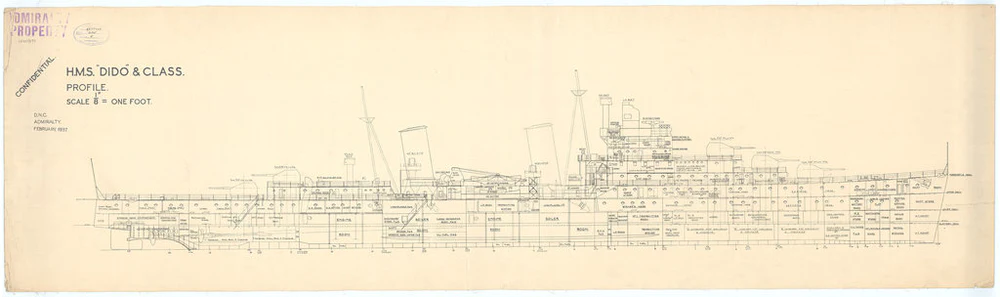

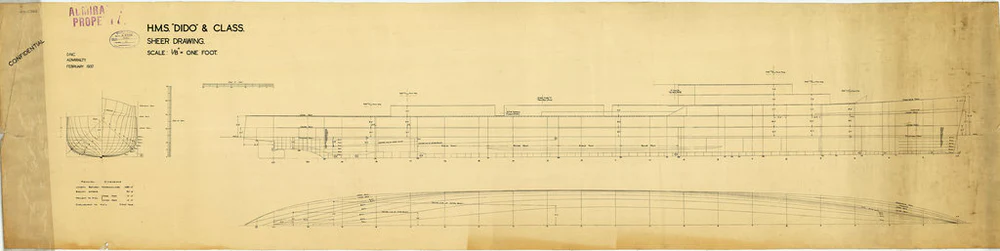

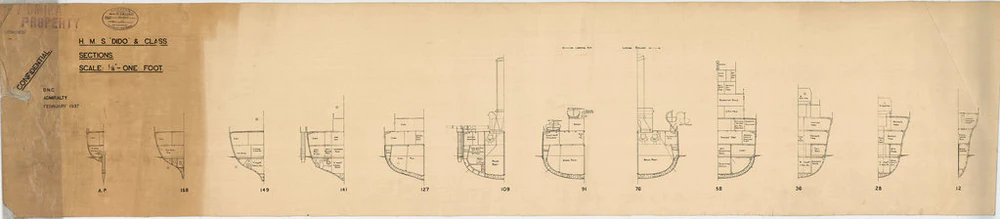

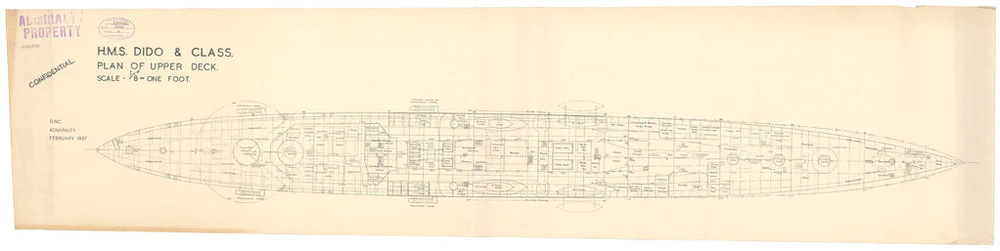

Dido class plans: platforms, superstrucures bridge

deck plans

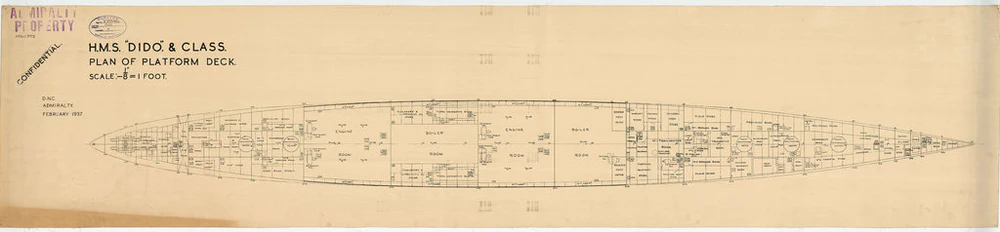

inboard plan

sheer plan

sections plans

deck plans

Powerplant

As said above, the powerplant was directly based on the Arethusa class, but with more modern, high pressure boilers. These cruisers had four propeller shafts connected to four Parsons steam turbines, fed by the steam produced in four Admiralty 3-drum boilers, for a total output of 62,000 shp (46,000 kW). By comparison, this was 64,000 shp (48,000 kW) for the Arethusa class, so bit less. The machinery with its alternating boiler and engine rooms was completed by four turbo-generators capable of generating 1,200 Kwh and power notably the turret’s elevation and traverse.

As a result, designed top speed not particulary great, at 32.25 knots (59.73 km/h; 37.11 mph), still correct for fleet work (same as Arethusa), for a lesser range of 4,850 nmi (8,980 km; 5,580 mi) at 11 knots (20 km/h; 13 mph), versus 5,300 nmi (9,800 km; 6,100 mi) at 13 kn (24 km/h; 15 mph) for the Arethusa, based on 1,325 tons fuel oil. For the Dido class it was likely less. At sea, they reached thier designed speed, and showed the agility required, with a hull structure able to resist the battering of the north Atlantic. The hull lenght was however too short to go through waves, and rather ride them. But they were responsive at the helm, having however a higher metacentric height. They developed some stability issues with a somewhat high roll.

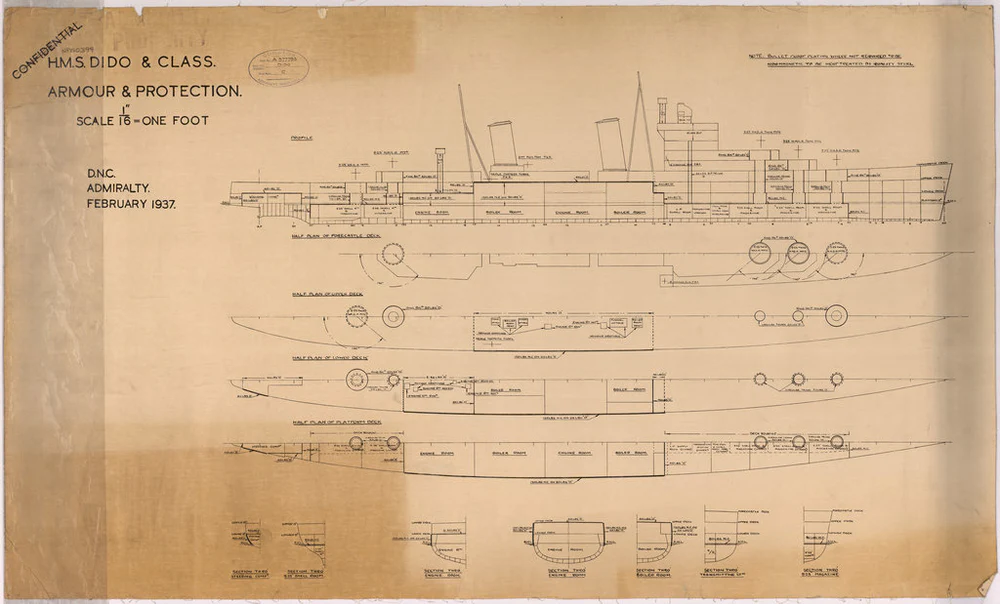

Armour Protection

Armor protection scheme, original blueprints.

The “poor child” of the design, it was limited to the strict minimum. Again, compared to the Arethusa it had some differences:

-For the Arethusa class it was limited to 1 to 3 inches over magazine box protection, 2.25 inches for the belt and 1 inch for the armored deck, turrets and bulkheads.

-For the Dido class, the Belt was a bit thicker at 3-inches (76 mm), with transvrse bulkheads 1.1 inch (25 mm) thick and DP turrets protected by just 0.5 inches (13 mm) and the armor deck by 1.1 in (25 mm) of armour overall, but reaching (2 inches) 51 mm over the “sensible parts”, steering gear, and ammunitions magazines below. So overall, it was slitghly better.

Like the original design, the engine compartimentation on four separate rooms helped ASW protection, as the hull’s extra side compartimentation, and double bottom for a part of the hull. The 3 inch belt was abreast the engineering spaces and enclosed as seen by one inch for the horizontal deck above, and and transverse bulkheads on both ends of the citadel. An extra 2 inch deck covered magazines enclosed by one inch longitudinal bulkheads fitted abreast. The turret’s one inch protecting walls was increased forward to 1.5 inch plating. The steering gear was entirely enclosed by one inch sides and deck. All that design scheme was deemed sufficient for engineers to deal with with 6 inch (so light cruiser) gunfire. It was permitted by the weight saving measures taken in general, and participated to the overall stability of the hull.

Armament

HMS Dido proceeds along the Italian Coast for a successful bombardment of enemy positions of Gaeta area (Operation Husky)

The Dido class received Mk II 5.25” mountings, chosen initially as featuring combined magazines and shell rooms which also saved weight, offering in addition of some 60 crew members, something quite appreciable in peacetime as a cost-saving measure, and in wartime, freeing crews for other vessels. These ten 5.25-inch (133 mm) guns were spread into five twin turrets using the same barbettes and casemates as the secondary armament in the King George V-class battleships.

These guns were constructed of autofretted loose barrel witout liner and a jacket 99 inches (2.5 m) from the muzzle. It also had a removable breech ring, equipped with a sealing collar. Its horizontal sliding breech block was manually operated, but with with semi-automatic opening. So it was never “semi-automated” in the end. Changing barrel was a long and complex operation. In total, Vickers produced 267 guns (six were even loaned to be tested by the Army). They were spread between the 10 cruisers initially ordered (ten each to 100 plus spares) and the King Georges V (forty plus spares) so it should have been well above 300 total.

The manufacturer never ceased improving the gun and worked on the Mark IV in a new Mark III twin mounting with vertical-sliding breech blocks to fire fixed ammunition, so reaching a higher rate of fire. However these were proposed on paper and only ordered in 1944, staying in the end porjects only. Postwar, the twin Mark III (70 RPM) stayed on the drawing board. Nevertheless, the army also tested the 5.25″ (13.4 cm) Mark II, Mark III and Mark V as AA guns with higher muzzle velocity but few were manufactured and tested, having stronger breech ring and breech block. They never reached production.

HMS Dido received her fifth intended turret on “C” position by late 1941, but the second group had all five twin 5.25-inch guns. The third group were armed with eight QF 4.5-inch (113 mm) guns in four twin turrets, a wide decision as the latter was far better suited to AA fire. They were coupled with a simpler dual-purpose twin Director Control Tower (DCT) while 2-pounder armament was increased to ten mounts. The Bellona subclass will be seen later. read more on navweaps

Controversy: Worst dual purpose artillery ever ?

Leander and Dido class comparison

It appeared that the dual purpose artillery so many hoped for would be a game changer as a universal defensive caliber, proved to be disappointing to say the least. Forst off, its rate of fire was far lower than expected. This was compunded by the slow elevating and training speeds of both mounts, completely inadequate to engage modern high-speed aircraft. When the mount was first worked on however, aviations worldwide still fielded biplane bombers reaching 250 kph at best.

Not only these were crippling blows for the hopes placed in them, but in addition bottlenecks prevented all turrets to be fitted on the Dido as planned, those being reditected to complete the King Georges V in priority. And if that was not enough, when tried, ‘A’ turret repeatly jammed in service. There were no less than 13 separate incidents reported during 1940-41. And this was in combat as well, as report by HMS Bonaventure when fring at KMS Admiral Hipper in December 1940. These resulted in a previously unsuspected consequence of lightening the hull so much. The bow indeed flexed in heavy weather or in high-speed turns header than expected, and this cause the sensitive ‘A’ barbette to jam.

This was fortunately rectified, stiffening the bow section and greater attention to detail in the mountings installation. Further modifications were incorporated during construction of the next vessels so no such problems were encountered afterwards. Also in the winter of 1941 more aware captains started to learn and “handled them appropriately” in heavy weather also contributing to the solution. Still, in 1950 HMS Euryalus same A turret had her barbette roller path worn out, comdemning this turret. D.K. Brown of the RCNC said about these to be “generally unreliable.”

To add insult to injury, these proved difficult to manufacture, taking extra delays. So much so was the impatience of the admirakty that instead of having all these cruisers waiting it was decided to share the available on the completing cruisers save for HMS Charybdis and HMS Scylla, with the radical decision to get rid of these turret altogether and give them instead eight 4.5″ (11.4 cm) guns while the early batch was completed with four original turrets. Had to wait late 1941 to be fitted, Bonaventure was sunk before, and HMS Phoebe never received it as the Spartan sub-group.

As a result of all this mishaps, mountings designed for HMS Vanguard were completely improved with notably a much more capable RPC system coupled with the USN’s outstanding Mark 37 fire control system. The manually-operated fuze-setters were liminated and accuracy increased ten fold whereas the gun crews enjoyed a much greater working space. But Vanguard never saw action in WW2 not in Korea and cound not prove the worth of this weapons system. It was far too late.

AA Armament

HMS Charybdis design

The Dido class, as originally planned were to be armed (first group) with a single 4 in (102 mm) gun used for saluting and firing star shells, plus two quadruple QF 2-pounder (40 mm) “pom-poms”. It was rather weak to 1941 standard (when some were completed), with only these quadruple 2-pdr (40 mm (1.6 in)) installed amidships. These were capable of 115 rpm, with 732 m/s (2,400 ft/s) muzzle velocity, a 3,960 m (13,300 ft) A/A ceiling and 6,220 m (6,800 yd) at 701 m/s (2,300 ft/s) range. Reload was manual, using 14-round steel-link belts.

They received also four twin 0.5 in Vickers AA machine guns placed for and aft on sponsons (later eliminated during refits). The 0.50″/62 (12.7 mm) MG Mark III came into three “flavors”, single, dual and quad. The dual mounts had water-cooled jacketed barrels, which fired a 2.9 oz (0.08 kg) round at circa 6-700 rpm in cyclic mode, 450 rounds with delay pawl to cool the barrels and down to 150 practical. They could reach a target at 800 yards (730 m), effective range. Read More

Torpedo Armament

The Dido class, at the insistence of the admiralty which wanted to preserve antiship capabilities, were fitted each with two triple banks, likely the 21″ (53.3 cm) Mark IX**. The latter carried the best warhead of the type, with 805 lbs. (365 kg) Torpex, at two settings, 11,000 yards (10,050 m) at 41 knots or 15,000 yards (13,700 m) for 35 knots using a Burner-cycle, 264 hp @ 41 knots. They were retired later in the war on some ships (see modifications).

ASW Armament

A 20 mm Oerlikon gun on board HMS Hermione, showing a naval gunner utilising the rubber shoulder rests for high-angle firing, with the Thornycroft depth charge thrower Mark II and depth charge launching rail in the background, confirming some cruisers were indeed so equipped according to photos.

None was planned initially, but some sources cites a Type 128 ASDIC sonar installed during their career, but i can’t back it up anywhere. However if no ASW suite was noted on the Dido it was present on the Bellona class and photos as well as battlke records confirm most Dido class indeed carried racks and projectors. HMS Charybdis used her ASW depth charge throwers. It could be localized to a specific sub-variant, proper to her and Scylla, since their lacked their intended artillery but in fact most cruisers were so armed, it’s just records are not straight as this was apparently a later wartime refit. U-Boats in their career became indeed their primary concern. None was sunk by aviation action.

Electronics

The ships were completed late, but still not fitted with radars at completion. They were in short supply, reserved to larger ships, and it was feared that their light construction would cause prejudiciable vibration for the sensitive electronics.

-First, only HMS Phoebe was so equipped, with a type 281, type 284, and type 285 radars in April 1942. Next, HMS Cleopatra in mid-1942 received a type 272 radar. Charybdis followed in 1943, while the same year for her second refit, HMS Dido recived the type 272, type 282, type 284, and type 285 radars and a month before in April, her sister HMS Euryalus received the same suite. Phoebe would receive the Type 272 in July 1943, and Argonaut the type 277, type 282, type 293 radars in early 1943. HMS Argonaut was the first to receive the type 281B radar in late 1944. After the war, all settled on about the same radar suite, comprising the type 272, type 279, type 281, type 284, type 285 radars, with some minor variations between them.

Author’s old illu of HMS Sirius in 1941, with its standard Atlantic camouflage. More recent, HD to come.

⚙ Dido class specifications *original |

|

| Dimensions | 512 x 50 x 16 ft 10 in (156 x 15,40 x 5,11 m) |

| Displacement | 5,521 long tons (5,610) standard, 7,081 long tons (7,195) full load |

| Crew | 487 |

| Propulsion | 4 shaft Parsons turbines, 4 Admiralty boilers, 62,000 hp (46,000 Kw). |

| Speed | 32.25 knots (59.73 km/h; 37.11 mph) |

| Range | 4,850 nmi (8,980 km; 5,580 mi) at 11 knots (20 km/h; 13 mph). |

| Armament | 10 x 133 (5×2)*, 2×4 2-pdr QF pompom, 4×2 0.5 in HMG, 2×3 21-in (533 mm) TTs. |

| Armor | belt: 3-in, bulkheads: 1-in, turrets 0.5 in, decks: 1-2 in |

Wartime Modifications

HMS Black Prince in 1944. Note the absence of ‘Q’ turret

1941:

In 1941, Naiad, Euryalus and in November HMS Hermione received two quadruple Vickers 05. in /62 HMGs AA and five 20mm/70 Oerlikon Mk II/IV AA guns. In September Dido was the first receiving it’s lissing fifth 133mm/50 QF Mk I and a single 102 mm/45 (4 in)? In December she would also received the same quad Vickers and five 20 mm Oerlikon AA.

1942:

In March, HMS Phoebe received a single 102mm/45 same Vickers and three extra quad QF Mk VIII Pompom, plus eleven Oerlikon AA guns and radars. HMS Cleopatra received two single extra 40mm/39 Bofors and five Oerlikon and Euryalus by September, two extra Oerlikon, and a single one on Clepatra later in October.

1943:

By February Charybdis received a single extra 4-in (102mm/45) and two single Pompom plus two twin and two single Oerlikon plus radar while Argonaut received four extra single and seven twin Oerlikon AA and new radars. In March Euryalus received two, four twin single Oerlikon and radars, in April Dido had three single, four twin extra Oerlikon Mk II/IV and extra radars. In May, Sirius received two twin Oerlikon and in July Phoebe, three quad Pompom and seven single Oerlikon, then three quad 40mm/56 Bofors Mk 1.2, and six twin 20mm/70 Oerlikon plus radar.

1944:

Scylla in Jan-Feb. received six twin Oerlikon AA, Sirius a single andtwo single 40mm/56 Bofors Mk I/III. In July Euryalus received its missing “Q” 133mm/50 turret, an extra quad Pompom 40mm/39 2pdr QF Mk VIII, two twin Oerlikon and new radars. By November, Cleopatra also received her “Q” turret and two quadruple Bofors, four single Oerlikon and new radarsn and and later three quad US 40mm/56 Bofors and six twin Oerlikon, upgraded rara suite. In December, Argonaut received the same upgraded suite plus six Oerlikon AA.

1945:

In April, Sirius received two extra Oerlikon and two single Bofors. In August, Argonaut received (at last !!!) her missing “Q” turret and seven twin Oerlikon, seven single Bogfors and a single quad QF Mk VIII Pompom. Howver it seemed it was retired and Argonaut, Cleopatra, Euryalus and Phoebe reverted to four 5.25 in (133/50 Mk II) turrets, but also the standard AA suite of three quad Bofors Mk 2, six twin 20mm/70 Mk V and several single Mk III Oerlikon, and they kept their TTs. Info is always conflicting about the presence or not of ASW armament.

Final assessment: Were they that bad ?

The Dido class had been lambasted for their inadequate main artillery, way too slow to engage aircraft and too weak for an antiship, making these vessels “three legged ducks”. But still, they possessed a sizeable ASW armament, and after modifications, loosing their “C” turret for conventional Bofors, with extra AA added and the TT sacrificed, plus extra ASW armaments, they became more useful escorts.

About the five turret 5.25 in configuration with the actual “Q” turret it was rare and only Dido had her full armament as planned for most of WW2. The others had it later, or not at all, and it seems to have made little difference. It’s mostly on their QF 1-pdr Pompom, 40mm/56 Bofors and 20mm Oerlikon, obtained soon enough, they relied on. Not intended for fleet action but escort, these cruisers did just that, with expected losses due to the theater or operations they fought on, and losses that had nothing to do with their faultly main AA: Apart Charybdis sunk in a night battle by German torpedo boats (seems the 4-in gunners never had the time to fire a shot), the three others were sunk by U-Boats (most were indeed torpedoed but some survived, like Phoebe and Argonaut). At least two served in Crete, most made several, or even took part in all Malta convoy, enduring the fiercest axis air attack, and all survived.

All along they seemingly provided the valuable escort they were tasked for, on several theaters, not only in the Med, but on the Indian Ocean, Atlantic north and south, or on the dreaful supply route to Russia in Murmansk, again under fire from Norway-based Luftwaffe. Ship to ship duels were rare, so they mostly spent their time providing AA defense. All in all, these are not clues of “bad cruisers”, not at all. Their default was never fatal and they accomplished their missions regardless, as intended. They were not ideal, but still worth the taxpayer money, although indeed their active life was short, rarely going very far after the end of WW2 (most were scrapped in 1955-59, with long reserve periods in between). Seems their concept was a one-off attempt quickly made obsolete with modern jets and the advent of missiles.

Links/sources

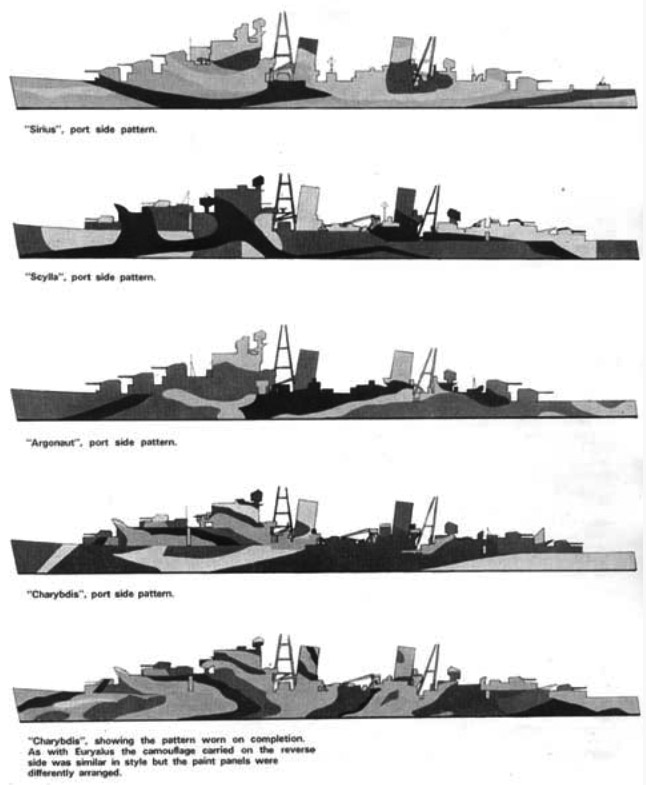

Various liveries of the class

Books

J. Dardiner, Roberts eds. Conway’s all the world’s fighting ships 1922-47

Brown, D. K. & Moore, George (2003). Rebuilding the Royal Navy: Warship Design Since 1945. NIP

Campbell, John (1985). Naval Weapons of World War Two. Annapolis, Naval Inst. Press (NIP)

Campbell, N.J.M. (1980). “Great Britain”. In Chesneau, Roger (ed.). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1922–1946.

Friedman, Norman (2010). British Cruisers: Two World Wars and After. Barnsley, UK: Seaforth Publishing.

Lenton, H. T. (1998). British & Empire Warships of the Second World War. NIP

Murfin, David (2010). “Damnable Folly? Small Cruiser Designs for the Royal Navy Between the Wars”. Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2011. NIP

Raven, Alan; Lenton, H. T. (1973). Dido Class Cruisers. Ensign. Vol. 3. n.p.: Bivouac Books.

Raven, Alan & Roberts, John (1980). British Cruisers of World War Two. NIP

Rohwer, Jürgen (2005). Chronology of the War at Sea 1939–1945: The Naval History of ww2 NIP

Whitley, M. J. (1995). Cruisers of World War Two: An International Encyclopedia. London: Cassell.

Links

On maritime.org

WNBR_525-50_mk1 navweaps.com

navweaps.com guns

www.navypedia.org

On uboat.net

On laststandonzombieisland.com

naval-history.net

On militaryfactory.com

On gb-navy-ww2.narod.ru

hmsnaiad.co.uk

world-war.co.uk

wiki

On gb-navy-ww2.narod.ru

Extra details on the armor protection

Videos

Drachinifel’s HMS Dido – Guide 129

warthunder 3d renditions footage

On armada, world of warships

3D renditions

The model kit corner

main query on scalemates

The large hull of southerncrossmodels.com.au

1:700 naiad – modellbau-koenig.de

On shapeways

fleetscale.com

steelnavy.net

HMS Dido (1939)

HMS Dido (1939)

HMS Dido at completion

HMS Dido was commissioned on 30 September 1940 at Birkenhead, sent to Scapa Flow for training, notably to perform high-speed sweeps off Fair Isle and Greenland. Her first mission came about in November, sent to the Atlantic, escorting HMS Furious to West Africa ferrying aircraft. Next, she joined the Atlantic fleet. She spent four months in relatively uneventful convoy duty. Next she was sent to the Mediterranean for a serie of supply convoys to Malta and Eastern Mediterranean Fleet (Force Z, Alexandria, Egypt) in April 1941. In next May she covered evacuation convoys from Crete. She escorted a convoy from Souda Bay on 14 May with prevcious bullion from Greece ($7,000,000). On 29 May 1941 during another such mission however, she was taken by a massive Stuka attack, and badly damaged whilst evecuating more troops from Crete. “patched” and repair ed summarily she was sent on East African hosting on 8 June 1941, the surrender of Italian Forces in Assab in Eritrea, by Royal Marines.

Next in July she crossed the Atlantic to join the Brooklyn Navy Yard in New York City. Repairs and refit followed, until November 1941, allwing her to rejoin the Eastern Mediterranean Fleet, by December 1941. The first three months of 1942 saw her escorting convoy between Alexandria and Malta, with a short assignment in March as part of the bombardment group of Rhodes. She would take part, just a week late to the Second Battle of Sirte with her sister HMS Cleopatra and Euryalus, and the light cruisers Penelope, and the old C-class Carlisle, under RADM Philip Vian. She emerged damaged from the battle after taking a bomb to the stern.

On 18 August 1942 Captain H. W. U. McCall took command, and sailed to Massawa for major repairs of her stern. At this particular moment, a but like in the Pacific, she represented no less than 1/4 of British surface power in the Eastern Mediterranean, making her repairs all the more urgent. Since the Massawa drydock was not large enough, was partially floated up to clear the stern, her bow low in the water. Repairs were performed at a frantic pace and six days later she was undocked and back to action with her sisters Euryalus, Cleopatra and Sirius. She would be after many more missions transferred to the Western Mediterranean Fleet in December 1942, and participated to Operation Torch for anti-aircraft cover, on front of Bone and Algiers, being relieved from duty by March 1943.

In April she was back in drydock in Liverpool for a well deserved 3-month refit. She returned to the Western Mediterranean squadron, taking part in diversionary bombardments in North Sicily during Operation Husky. She covered also the invasion in Palermo and Bizerte. On 12 September 1943, she escorted a single troopship to Taranto just as Italy surrendered, moving to Sorrento as a troop support. October-November 1943 saw her back in Alexandria for a third refit.

Next, she was stationed in Malta, alternating with and Taranto, taking part in another diversionary action off Civitavecchia to allow landings at Anzio. By August 1944 she took part in landings in southern France, Operation Anvil Dragoon. By September 1944 she was back home for another refit, and a month later, back at sea, reassigned this time to the northern convoys to Murmansk. There, she escorted her first convoy by October and was reassigned to support one of the several carrier strikes off Norway to destroy KMS Tirpitz. By April 1945, she performed one of her last escort mission, covering HMS Apollo, Orwell, and Obedient during their mainelaying of the North Kola Inlet, interdicting U-Boats.

Her very last wartime mission was to assit the surrendering of German occupation troops in Copenhagen, firing the last shot in the war in Europe, and assisted to the surrender of Dönitz Kriegsmarine, signed aboard. After this shecorted the future war prizes KMS Prinz Eugen and Nürnberg to Wilhelmshaven to be disposed of by the allies. The war ended in Europe but not yet in the Pacific. By July she was not scheduled to be sent to the Pacific, and instead hosted King George VI and Queen Elizabeth during a Royal trip to the Isle of Man. 1946-1948 sw her having a new captain, P. Reid. Her career was relatively uneventful, and apart a 1953 Fleet Review for the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, she was placed in the Reserve Fleet, as flagship. She was decommissioned and sold for BU in 1957.

HMS Bonaventure 1940 (IWM_A_1733)

HMS Bonaventure was built at Scotts, and commissioned on 24 May 1940. After the usual quick sea trials and intensive wartime training she was assigned to the Home Fleet and deployed for her first mission to Operation Fish, the evacuation of British Gold to Canada, largest gold stock transit in history. She took part in many escort missions to mid-atlantic, until deployed in th Gibraltar based Western Mediterranean Fltee. On 10 January 1941 Bonaventure she teamed with HMS Southampton and Hereward for a shelling mission off Cape Bon (Tunisia). There, she sank the Italian torpedo boat Vega during Operation Excess. She also lost two sailors to return fire.

On 31 March, however he luck turned and she was ambushed underway and hit amidships by two torpedoes from the Italian submarine Ambra (Perla class). The flooding was so intensive she sank rapidly south of Crete, carrying with 139 of her 480 crew, but slowly enough for 310 survivors to be rescued by her destroyers escorts HMS Hereward and HMAS Stuart. She was both the first Dido class sunk, and the largest warship sunk by an Italian submarine during the war.

HMS Naiad (1939)

HMS Naiad (1939)

HMS Naiad 1940 (IWM)

HMS Naiad Completed in July 1940 and commissioned on 24th July 1940. After sea trials and initial training, she was assigned to the Home Fleet and started a cycle of escort missions. She was assigned to the 15th Cruiser Squadron and deployed in search of German raiders after the sinking of the AMC HMS Jervis Bay in November 1940. She was directed after a reconnaissance, with other vessels, to the German weather ship Hinrich Freese off Jan Mayen, which was sunk.

In December 1940 and January 1941 she escorted two convoys to Freetown (Sierra Leone). By late January 1941 she patrolled the north sea. She briefly spotted the “terrible sisters”, Scharnhorst and Gneisenau south of Iceland as they started their breakout into the Atlantic, named Operation Berlin. This encounter srambled the RAF and RN to stop them. By May 1941, HMS Naiad was reassigned to the Mediterranean, with Force H to start dangerous convoy escort missions to Malta. There, she became flagship of the 15th Cruiser Squadron.

She took part in the evacuations in Crete, and was one of the rare Dido class vessels actually damaged by aviation, with a near-miss from a Stuka. After summary repairs she took part, still in 1941, the the operations against Vichy French forces in Syria. With HMS Leander, she bombarded the main port and its assets, and engaged the attacking French destroyer Guépard. She spent the rest of the year and early 1942 in two convoy escorts to Malta and patrolling. By March 1942 however, while sailed from Alexandria to attack a damaged, stranded Italian cruiser (a false report), she found nothing and when back underway on 11 March 1942 she was spotted and sunk by U-565 south of Crete. She sank slowly enough (likely a single torpedo hit) so that 77 of her crew went with her to the bottom. The rest was rescued.

HMS Phoebe (1939)

HMS Phoebe (1939)

HMS Phoebe in 1940 (FL5271)

HMS Phoebe was commissioned on 27 September 1940, and after the usual speed trials, fixes, and shakedown cruise plus intensive training, all wrapped in a month due to the war, she spent her first six months with the Home Fleet, detached to escort troop convoys via the Cape to the Middle East, without incident. In April 1941 she was asssigned 7th Cruiser Squadron, Mediterranean Fleet. One of her first operations was to evacuate allied troops in Greece and Crete. Next she covered the landings in Vichy-Controlled Syria and she carried herself troops troops to and from Tobruk.

On 23 October 1942, she was ambushed on her way, torpedoed by U-161 off the Congo Estuary, while underway to French Equatorial Africa with Simonstown, South Africa and Freetown in Sierra Leone as destinations, with a mid-refuelling at Pointe Noire in Congo. there, U-161 and U-126 were patrolling that area, knowing full well this poissibkle refuelling spot for allied vessels, and it worked. By the way, the south atlantic/west coast of Africa was far less patrolled.

She was struck by a torpedo and slowed down considerably, becoming an easier target, but was protected by a Flower class corvette coming up from the harbour at the tight time, which chased off the U-Boat, preventing it to finish the job. 60 crew members were killed in the explosion and flooding. She was able to limb back to Pointe Noire for temporary repairs, just enough to carry out a tran-atlantic crossing to New York NyD for more complete repairs. This represented 10,000 nautical miles (19,000 km) in her poor state, with a hastily patched gaping hole 60 by 30 feet (18.3 m × 9.1 m).

Full repairs were carried out with a refit and modernization but ended by June 1943. She was back home afterwards for more escort missions, and by October was ordered back to to the Mediterranean for Aegean operations. The goal was to clean up the axis-infested islands, one of the last stronghold in this area. Once done she was back home for another refit.

Phoebe Belfast 1942

By May 1944, she was transferred to the Eastern Fleet, proceeding to Alexandria and then through Suez to the Indian Ocean, taking part in raids against the Japanese-held Andaman Islands, Sabang (Northern Sumatra) and the Nicobar Islands. By January 1945, she was versed to the British Pacific Fleet (BPF) to support landings in Burma, bringing fire support and AA defence and noted for her actions at Akyab, Ramree Island (Arakan Coast) and Cheduba Island. In April-May 1945, she was reassigned to 21st Aircraft Carrier Squadron and took part in the amphibious assault on Rangoon. Last operations in the areas followed, and repatriations of POW after August.

She returned home by late 1945, for refitting and be placed in reserve. She was not scrapped in 1947 like some, but spent five years in the Mediterranean Fleet. In early 1948, she carried Royal Marines 40 Commando to Haifa, during the British withdrawal from Mandate Palestine. On 30 June 1948, she carried the last General Officer Commanding of Palestine and the last rearguard troops. She returned in reserve until sold for scrap in 1956.

HMS Cleopatra (1940)

HMS Cleopatra (1940)

HMS Cleopatra in the far east, 1945 (IWM)

HMS Cleopatra was commissioned on 5 December 1941 and after short training with the Home fleet for the remainde rof the year and in January, she was assigned to Gibraltar in early 1942. On 9 February she she was assigned to a first convoy to Malta, and to stay there. She damaged by a bomb during the “blitz”. Repairs were done so she could complete them in Alexandria in March, assigned to the 15th Cruiser Squadron.

She became also Admiral Philip Vian’s flagship as she sailed at the head of her unit and the large squadron (4 light cruisers, 17 destroyers) deployed in the Second Battle of Sirte. There, she was the centerpiece of the battle pitted thme against the battleship Littorio, two heavy cruisers, a light cruiser and 10 destroyers en route to intercept another large eastern convoy to Malta. Cleopatra’s radar and wireless stations were destroyed by a 6 inches round from Giovanni delle Bande Nere. Her aft turrets were also damaged but the battle was won strategically as the convoy could proceed unscaved. But a defeat tactically due to the heavy losses: 39 killed, 3 light cruisers damaged, 2 destroyers disabled and 3 destroyers damaged, versus no casualy and only light damage on littorio.

By June 1942, she took part in Operation Harpoon/Vigorous, the double convoy battle. She emerged largely unscaved from the fight. In August 1942 she took part in the shelling of axis-held Rhodes, as a diversion for Operation Pedestal. She was in maintenance, drydocked in Massawa on 19 September 1942, also for repairs and cleaning, out in 5 days. However the refloating operation saw her slipped on the angled drydock, crushing the wooden keel block with light hull damage. Captain G. Grantham was communicated a minor leak, which was patched as she went out for her next assignment.

By January 1943, she was reassigned to Force “K” (later “Q”) and operated in convoy escort and then off Bône to intercept Axis traffic to and from Tunisia. She was reasigned to the 12th Cruiser Squadron, participating to Operation Husky (Sicily) in June 1943, called for gunnery support ashore. On 16 July 1943, she was torpedoed by the Italian submarine Dandolo (Marcello class) and badly damaged, probably a single torpedo. Her ASW protection held firm, which she listed as a result, and underwent Temporary repairs at Malta, until October 1943

This was considered enough for her to cross the Atlantic to Philadelphia NyD for more extensive repairs. Like HMS Phoebe she received US pattern quad Bofors. Due to reports over the frequency of air attacks over the bow forward fire power was was enhanced by the addition of quad Bofors in “B” position (and so the turret was removed). She was underay again by in November 1944. But operations at sea on the western front were mostly over and after some escort missions she was reassigned in early 1945 for the East Indies. There, she took part in the late campaigns of the BPF, and became the first ship entering the recaptured base at Singapore, in September 1945.

Post-war saw her with the 5th Cruiser Squadron, East Indies, before a refit back in Portsmouth on 7 February 1946. She was stationed next in the Home Fleet, 2nd Cruiser Squadron until 1951. She had a major refit, gaining notably the new twin Mk 5 40 mm guns with a new captain since 1948, P Reid. She was back in the Mediterranean in 1951-1953, taking part in the 1953 C.S. Forester’s Brown movie “Sailor of the King” or “single-handed” in the US as the fictional “HMS Amesbury” and “HMS Stratford”. Back in Chatham on 12 February 1953 she was paid off and by June took part in the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II Fleet Review. Until 1956 Cleopatra she became flagship, reserve squadron with a skeleton crew. By 15 December 1958 she was sold to Newport yard, J Cashmore and BU.

HMS Charybdis (1940)

HMS Charybdis (1940)

HMS Charybdis was completed, like her sister ship Scylla (of course paired, mythology oblige), with four 4.5 in AA guns instead of the intended artillery. And this was for the best. Both had a very active life. HMS Charybdis was completed and entered full commission on 3 December 1941. After trials she started training with the Home Fleet, and departed on December 1941 with the 1st Minelaying Squadron as escort during Operation SN81, laying the Northern Barrage.

By March 1942 was adopted by the civil community of Birkenhead after a Warship Week savings campaign. On 30 March she escorted another minelaying mission, SN87. In April 1942 she was reassigned to Force H at Gibraltar, sailing the escorting along the way USS Wasp and HMS Renown. Later she was reassigned upon arrival to Force W, still escorting Wasp to deliver aircraft to Malta, Operation Calendar. After being back to Gibraltar she escorted her into the Atlantic and returned. She next escorted other aircraft carriers for extra taxiing missions to Malta, often screening Wasp and HMS Eagle at Operation Bowery (May), the same and HMS Argus for Operation LB and into June 1942 (Operation Style and Operation Salient).

On 11 June with Eagle and Argus, and escorted by HMS Malaya, the cruisers HMS Kenya and Liverpool she took part in Operation Harpoon, in coordination with another convoy from Egypt (Operation Vigorous). Despite fierce attacks on the convoy she remained unscathed. In July 1942 she escorted two other convoys (Operations Pinpoint and Insect) with more carrier deliveries to Malta. By August she was reassigned to Force Z, escorting HMS Eagle in Operation Pedestal.

This time, things became “hot” for the light crisers, after so many missions without much harm. The massive, 15-ship convoy was protected by the largest naval force assembled to date. HMS Eagle under her protection was sunk by torpedoes from U-73, only five merchant ships escaped. Charybdis apparently was armed with depth charge as she launched attacks on U-73 without sccess and assisted the damaged HMS Indomitable providing AA cover the best she could while salvage operations proceeded. The carrier was saved.

On 13 July Admiral Edward Neville Syfret ordered her to join Force X with the destroyers HMS Eskimo and HMS Somali escorting merchant veseels. They were caught by a violet air attack while passing through the Strait of Sicily. HMS Manchester being crippled, HMS Charybdis replaced her as flagship before returning to Force Z, repelling other air raids on the way back to base. By September 1942 it was decided to give them other roles, and she was sent in Atlantic patrols, searching for German blockade runners coming back from the Far East.

By late October she was back in the med, taking part in Operation Train, escorting HMS Furious for another taxiing mission to Malta. On 25 November she joined the 12th Cruiser Squadron, Force H based in Gibraltar. Together they sailed to Algiers for Operation Torch, escorting invasion convoys and provided on side, bombardment support, having her guns blazing in that manner for the first time, providing on-demand cover for engaged land forces, but staying for AA defence, dealing with the rare Vichy French air attacks. On 12 December 1942 she was sent home for a well deserved refit.

Charybdis was back to the Home Fleet after post-refit trials in March 1943. Training in Scapa Flow, she covered new minelaying operations before beong sent in patrol in the North Sea until April 1943, and transferred to Plymouth Command to escort allied convoys in the Bay of Biscay. Back in Gibraltar by August 1943 she resumed her Mediterranean convoy escort missions. By September Charybdis she took part in Operation Avalanche with Force V (landings at Salerno). She hosted US General Dwight D. Eisenhower when stationed off Salerno. Back to Plymouth for a short leave and minor refit, this was cut short and she returned in the Bay of Biscay.

British intel by late 1943 knew about the German blockade runner Münsterland carrying latex and strategic metals vital for the German was industry to be closing and trying to get back in Germany. For escorting her, submarines were posted along the way and aviation ready to pounce. Meanwhile the admiralty activated Operation Tunnel to intercept her before reaching the safety of the Luftwaffe. Lieutenant-Commander Roger Hill placed at the head of the flotilla voiced his reservations about the cruiser assignment, but she was assigned anyway, and prepared from 20 October, departing two days later with escorting destroyers HMS Grenville and Rocket, and four Hunt-class destroyers (HMS Limbourne, Wensleydale, Talybont and Stevenstone). Münsterland’s surface escorts were five newly joined Type 39 torpedo boats (4th Torpedo Boat Flotilla), commander Franz Kohlauf.

Charybdis picked up them on radar in the dead of night, scrambling the alarm to the flotilla, and prepared to engage them from 7 miles but HMS Limbourne which heard radio transmissions failed to pick up them as the cruiser blocked its view. At 1:38 am, German torpedo boat T23 (Kapitan Friedrich-Karl Paul) spotted Charybdis on its port side and directed T27 so that both would fired six torpedoes. The cruiser was hit by two of them amidship. HMS Limbourne was also hit and later scuttled while the convoy escaped unharmed. The mission was a total failure and Charybdis sank quicky, in 30 min. with the loss of more of her crew, over 400 men including captain George Voelcker. Four officers and 103 sailors survived, picked up for most the following days. She had her indirect revange: Münsterland tried to pass the channel and was spotted and fire at by coastal batteries west of Cap Blanc-Nez. Crippled, she was forced ashore andfinish off on 21 January 1944.

HMS Charybdis gained six battle honours, ‘Malta Convoys 1942’, ‘North Africa 1942’, ‘Salerno 1943’, ‘Atlantic 1943’, ‘English Channel 1943’ and ‘Biscay 1943’.

HMS Euryalus (1939)

HMS Euryalus (1939)

HMS Euryalus in June 1941 as completed (IWM FL 5242)

Commissioned on 30 June 1941 (after being launched in October 1937, so it took five years to have them put into service), HMS HMS Euryalus was hard-pressed into training with the Home Fleet, this summer, and was on mission on 17 September 1941, escorting convoy WS 11X from Glasgow to Gibraltar. On 24-30 September 1941 she took part in Operation Halberd her first Malta Convoy. Together with other cruisers, she sailed with her sister HMS Hermione from Gibraltar. Axis air attacks from Sardinia, starting on 27 September were fierce but she arroved and sailed back unscaved. On 1 October she was assigned to Force W at Gibraltar but later she joined the 15th Cruiser Squadron at Alexandria (11 November).

On the 24th was deployed with Force B (HMS Ajax, Galatea, Naiad, Neptune) searching for axis convoys to Benghazi. On 15 December she was detached with Naiad and eight destroyers under RADM Philip Vian to escort the freighter MV Breconshire to Malta. On 17 December she met with Force K from Malta and the whole duelled for a short time with the Italian fleet, before withdrawing, mission accomplished, to Alexandria. On 12 February 1942 she operated with Force B to escort Convoy MW 9 (with HMS Naiad, Dido and eight destroyers). A Luftwaffe attack on 14 February claimed the Clan Chattan. On 22 March 1942 she took part in the Second Battle of Sirte.

On 12-16 June 1942 she took part in Operation Vigorous to Malta, from Alexandria, with other vessels coming from Port Said and Haifa. She sailed with HMS Cleopatra (flagship), Dido, Hermione, Euryalus, Arethusa, Newcastle (RADM W. G. Tennant flagship), Birmingham, Coventry, and 19 destroyers. But also by the 1911 dreadnought (assumed retired) playing as a bogus deterrent, HMS Centurion, masquerading as Anson. Despite the loss of Hemione, the mission was a success.

On 23 January 1943, HMS Euryalus with Cleopatra and three destroyers selled axis forces at Zuara. Next she was mobilized for Operation Husky. On 10 July 1943 she was reassigned to the 12th cruiser squadron with HMS Aurora, Penelope, Cleopatra, Sirius and Dido. She was to cover attacking forces and Force H (VADM Algernon Willis) of four battleships, HMS Formidable and HMS Indomitable. The mission was a success and she was back to Alexandria.

After Sicily, she took part in Operation Avalanche, the landings at Salerno (9 September 1943) as part of Task Force 88, still under Vian. She had in charge the protection of the carriers HMS Unicorn, HMS Attacker, Battler, Hunter and Stalker. With her were HMS Scylla, Charybdis, and 9 destroyer, including a Polish one.

After this, the axis was defeated in the Mediterranean and apart the Aegan islands, operations came to a standstill. Although there was still Operation Anvil-Dragoon to come, the Admiralty wanted Euryalus in the far east. She was reassigned to 4th Cruiser Squadron based at Trincomalee (Ceylon) in January 1945. On the 24th she took part in Operation Meridian I, covering carrier strikes on refineries at Pladjoe in Sumatra. On 2 February she was definitely assigjned to the BPF at Fremantle, Australia, forst visit of the city and short refit.

On 28 February she was sent to Manus, and started operations with the BPF on 7 March. She met the USN Task Force 58 at Ulithi and the US Fifth Fleet for the last strikes on Japan and Okinawa. Her first operational area was Sakishima Gunto (Operation Iceberg 1). On 1 April she was assigned to the TF 57 carriers attacking Formosa (Taiwan). On 12 April sher took part in Operation Iceberg Oolong, covering strikes on Shinchiku and Matsugama. She was back later off Sakishima Gunto. By May she joined TF 45, assigned with TF 57 carriers, and took part in the same area of phase 2 of Operation Iceberg.

On 27 May HMS Euryalus was reassigned to US TF 37, making a refill/refit stop at Brisbane on 4 June before returnin to Manus FOB. From 6 July she was prepared for Operation Olympic, the invasion of Japan which never took place. She operated with TF 37, assigned to TF 38 covering strikes on the Tokyo – Yokohama area. On 24 July she covered striked on Osaka and Katori. On 9 August this was against north Honshu and Hokkaido. On 12 August she made a resplenishement back in Manus. Unlike the USN, the British Pacific Fleet lacked a comprehensive refuelling at sea support tankers force.

On 15 August, the surrender saw her tranbsferred back to RN control, and after a stop at Manus on 18 and 27 August she sailed with TU.111.2, covering HMS Indomitable and HMS Venerable, and cruisers such as HMS Swiftsure, HMS Black Prince, and three destroyers, for the surrendering of Hong Kong.

Euryalus served until 1954 on the South Atlantic station. She was the last and most modernised Dido, notably at John Brown NyD (October 1943-June 1944). 1946-47 saw her spending 18 months in the Pacific Fleet, operating from Sydney, Japan and Hong Kong. She was modernized back at Rosyth in 1947–48. She received the 279b/281 radar suite, precursor of the Type 960. She received the same turret modificatons as on Vanguard’s and Royalist, notably with large Perspex sighting windows. A 1950 modernization for Phoebe, Diadem and Cleopatra as well as her along the lines of HMS Royalist was dropped as per budget cuts and she was placed in reserve and BU in 1955.

HMS Hermione (1939)

HMS Hermione (1939)

HMS Hermione underway 1942

Commissioned on 25 March 1941, HMS Hermione and after workup training, she was assigned to the 15th Cruiser Squadron, Home Fleet. She escorted Atlantic convoys and took part in the pursuit of the KMS Bismarck and Prinz Eugen during their famous breakout attempt in the Atlantic to rampage the convoys. Their sortie in the North Atlantic in May 1941 saw Hermione rushing out of Scapa Flow on 22 May with King George V and the aircraft carrier HMS Victorious. On 24 May, Victorious escorted by Hermione, Aurora and Kenya launched an air attack on Bismarck, its Swordfish torpedo bombers managing in appealing weather and fierce AA barrage to score a single torpedo hit on Bismarck at the time without much consequence but the loss of oil.

On 25 May, Hermione was short of fuel and detached to refuel in Iceland. In between she learned about the loss of Bismarck. Next she was mobilized for a major search of German supply ships pre-stationed in the Atlantic for these raids. Hermione also searched for German blockade runners, but found none. She was reassigned to Force H, the Western Med Fleet based in Gibraltar, on 22 June. HMS Hermione started convoy escorts right away. On 2 August 1941, while underway she was attacked by the Italian submarine Tembien (an Adua class coastal submersible). She was too slow to dive and Hermione’s captain simply decided to ram her, sinking her in the process. This became a painting artist Marcus Stone, used as wartime propaganda.

But the “sub killer”, was to fall by another one. While under Captain G.N. Oliver she was taking part in another escort with Force A group, protecting convoy MW-11 (Overall command RADM Philip Vian) from Alexandria to Malta, the eastern convoy of Operation Vigorous. On 14-15 June 1942, heavy air attacks went on without respite and the cruiser fought them off, spending all her main ammunition in the process. Her captain decided it was wiser ti detach her bacl to Alexandria, escorted by HMS Aldenham, HMS Beaufort, and HMS Exmoor to resupply ammunitions and fuel.

However underway at 23:20 hours, while darkness had fallen on 15 June, U-205 spotted this night an unidentified group of warships, north of Sollum. The submarine attacked the two destroyers with a single guided G7e torpedo for each at 23:38 and 23:40 hours, but missed. When spotting the silhouette of a cruiser, the U-Boat fired a spread of three standard torpedoes at 00:19 hours. Hermione was hit on the starboard side, perhaps by two or even all three torpedoes. She immediately settled by the stern, listing 22° and capsized rapidly, her belly remaining afloat for 21 minutes before she disappeared beneath the waves, carrying with her eight officers and 80 ratings, but most of the crew survived, being picked up by the escorting destroyers, landed safely at Alexandria.

HMS Scylla (1940)

HMS Scylla (1940)

HMS_Scylla_1942

HMS Scylla after commission and trainin served with the Home Fleet, on the dangerous Arctic convoys route to Murmansk. She became flagship of RADM Robert Burnett during the famous PQ 18 escort in September 1942. She landed a signals intelligence team to the Kola Peninsula, collecting Signals Intelligence (PRO HW 14/53 and 55).

Next she was sent to the hotter Mediterranean, with the western fleet at Gibraltar on 28 October 1942. In November she took part in Operation Torch as part of Force “O” (Eastern Task Force) escort, and then shore gunnery support and patrols to prevent reinforcements. By December, she patrolled the Bay of Biscay in search of German blockade runners. On 31 December 1942, she was sent to intercept the spotted KMS Rhakotis (by RAF Coastal Command Whitley, 502 Squadron based in Cornwall). Thus was an exploit given the appalling weather and the bomber attacked her, but ran out of ammunition, shadowing her for over an hour before Scylla arrived and shelled her 200 miles (320 km) NW of Cape Finisterre. She was scuttled.

In February 1943 she was back to Arctic convoys and was sent again in the Bay of Biscay by June 1943, this time to cover anti-submarine operations (which confirms in a way she had no ASW suite). By July 1943 she stopped the Irish schooner Mary B Mitchell in the Bay of Biscay, and which she resumed her blockade runners patrols. In September 1943 she supported the Carrier Force involved in Operation Avalanche at Salerno. Next she was home, to be refitted as an Escort Carrier Flagship (October 1943-April 1944) one of the two cruisers of her clas fitted with the Action Information Organisation (AIO) room.

This way she could to co-ordinate radar and intercept information and vector escort carrier attacks. Scylla took her place as flagship for the Normandy landings, hosting Vice Admiral Philip Vian. She was considered vital to all shipping and naval movements, vectoring notably MTBs attacks against incoming German E boats and avoided many “blue on blue” incidents. She stays as flagship, Eastern Task Force for 18 days straight. On 23 June 1944 Scylla however she was badly damaged by on of the numerous air-dropped deriving German mines, declared a constructive total loss. She had to be towed to Portsmouth, never repaired and only disposed of in 1950 after being used as target from 1948. She was BU in Thos. W. Ward from 4 May.

HMS Sirius (1940)

HMS Sirius (1940)

HMS Sirius IWM coll. FL5263

HMS Sirius was completed in May 1942, after delays caused by a Luftwaffe bombing of the Portsmouth Dockyard. She was sent to Scotts Shipbuilding in Greenock, Scotland, for full completion. Assigned to the Home Fleetat first, she was sent to the Mediterranean by August 1942, just in time for the largest Conoy to Malta yet, Operation Pedestal. Next she was reassigned to the South Atlantic patrol, hunting Axis blockade runners. She was back to Gibraltar in November, reassigned to take part in Operation Torch in Force Q, and later took part from Bone by December to intercept Axis convoys to and from Tunisia until the surrenbder of axis forces in North Africa.

Force Q, comprising Sirius, Aurora, Argonaut and the destroyers Quentin and Quiberon, took part in the Battle of Skerki Bank, one of the very last major naval battles of the Mediterranean. Force Q was sent to intercepted a small Axis convoy in the Sicilian Channel, heading for Tunisia. There were the German troopship KT-1 and Italian troopships Aventino, Puccini and Aspromonte, escorted by three destroyers, two torpedo boats. The interception took place, thanks to radar, on 1–2 December, with flares and projectors. All four troopships and destroyers were sunk, but one heavily damaging and the two torpedo boats. Camicia Nera neverthless launched her six torpedoes from just 2 kilometers in the British formation, missing. At dawn, the British only deplored the loss of HMS Quentin, not to surface action, but a Luftwaffe’s Stuka attack at dawn.

Reassigned to the 12th Cruiser Squadron in July she took part in Operation Husky off Sicily. She supported by gunnery ashore oin demand the British army’s progression. In September 1942, she took part in the occupation of Taranto. She was reassigned to Adriatic operations afterwards, and by 7 October 1943 with HMS Penelope and the destroyers Faulknor and Fury she intercepted an axis convoy (Battle of Astipalea) off Stampalia (Dodecanese) co-sunk the sub-hunter Uj 2111, cargo ship Olympus and seven Marinefährprahm (one of the latter escaped).

Among her last actions in the Mediterranean was the action against Kos Harbour, with HMS Aurora on 17 October, under a fierce air attack off the island of Karpathos. She was hit on the quarterdeck by a Stuka’s 250 Kg bomb. This started fires aft, killing 14 sailors so she was obliged to withdraw to Massawa for repairs. This went on between November 1943 and February 1944.

After a further refit home, she was prepared to participate in D-Day operations, and supported landings in Normandy, off Sword area. Operation Overlord, saw her part of the reserve of the Eastern Task Force. But she returned in August to Mediterranean and participate to Operation Dragoon on the French Riviera. She returned in the Aegean to mop up the last axis vessels, and by October 1944, was present during the reoccupation of Athens. She was in the Mediterranean Fleet, 15th Cruiser Squadron until 1946, and was back home for a refit in Portsmouth, reassigned to the 2nd Cruiser Squadron, Home Fleet by March 1947. Paid off in 1949 she was kept in reserve, and eventually sold on 1956, BU at Blyth yard, Hughes Bolckow.

HMS Argonaut (1941)

HMS Argonaut (1941)

HMS Argonaut underway 1941

HMS Argonaut was commissioned on 8 August 1942. After intensive training in the Home Fleet in September, by October-November 1942 she was sent to escort the convoys as part of Operation Torch, stating to provided AA cover and then on-demand shore shelling. She was assigned to Force H (Gibraltar), under orders of VADM Sir E.N. Syfret. She guarded also the landings against a possible Italian attack or more probable Vichy French reinforcement from Toulon, and was dispatched on a diversionary mission.

In December 1942, she was reassigned to Force Q (RADM Cecil Harcourt) tasked of disrupting German–Italian convoys on the Tunisian coast, bringing reinforements to “Smiling Albert” Kesselring. In addition to Argonaut, she sailed with Aurora and Sirius, escorted by the destroyers HMS Quentin and HMAS Quiberon. By 1 December, Force Q took part in the Battle of Skerki Bank. They intercepted one such Italian Convoy, and largely destroying it and its destroyer escort: Four troop ships and the destroyer Folgore were lost. No casualty on the Allies side. This showed the Dido could quite well perform “classic” cruisers missions. A day after when sailing back theu were attacked by the Luftwaffe, which succeeded in sinking HMS Quentin west of Cap Serrat.

On 14 December 1942, HMS Argonaut was ambushed and torpedoed by the Italian submarine Mocenigo (Marcello class boat). She was struck with two torpedoes out of four close to the bow and stern, causing heavy damage as both were blown off and she lost all steering. Fortnately she lost only three crew members, but the axis reported her sunk. In fact, while the submarine fled ASW attacks, she was patched up by the crew, and after a day or more of at sea fortune repairs, she limped back to Algiers for more better repairs in drydock. Afterwards, she sailed for the US and a full refit plus 7-month reconstruction, emerging from the drydock by November 1943 (aso with new AA).

Back to UK, she received her new radar suite (Type 293 and 277) before making a quick refresher training cruise and taking part in many exercizes without notable events. She was tasked to take part in D-Day Operations in June, at Sword Beach. She stayed to provide shore gunnery a few days, before being sent to the Mediterranean, prepared again, this time under command of Captain Longley to support the Allied invasion of Southern France, Operation Dragoon, and started a final service as escort carrier flagship in the Mediterranean.

Still in this theater, she made a sweep of the Aegean Sea infested by axis forces, sinking small Axis craft, and transited via Suez to the Indian Ocean, joining the British Pacific Fleet in 1945. She followed troop convoys involved in the final phases of the war in the pacific, but was never damaged. She returned to the UK in 1946, was placed in reserve until scrapped in 1955.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign

Some of your comments contradict all other information released about these ships. Their main armament was indeed not fast enough for optimal use against aircraft but when providing barrage fire, especially in the Mediterranean and Arctic it proved a key element in deterring mass air attacks by breaking up formations. Several sources also state that their main armament was most effective in surface engagements at close range.

Hi David, as stated, this is a placeholder post, the text is an old automatic traduction from an even older source. Needless to say it will be rewritten in due time top to bottom and triple checked when officially released.