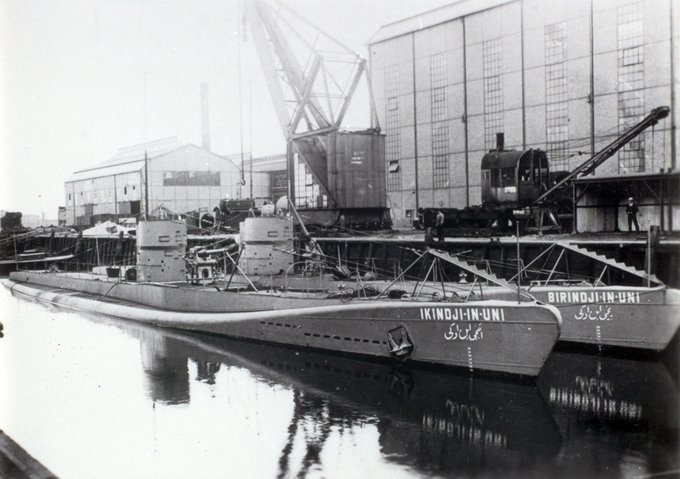

Birinci İnönü class submersibles (1927)

Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy

Introduction on Turkish Submarine 1923-1935

The development of Turkish submarines went on a long way. The very first ones, Abdülhamid and Abdülmecid, were commissonned in 1886 and 1887, at a time more Navies considered them experimental and little else. A cooperation between Sweden and British Yards, they were based on the Nordenfelt design, brought to Turkey in pre-manufactured parts, assembled in great secrecy behind closed doors, at the Tersane-i Âmire dry dock.

They stayed in service for a few years, showing the limits of the steam engine concept, but also what the future could look like. The experience served to put the basis of a submarine corps, train personal, but technology went a long way until WWI. At the time, Turkey had no submersible in service to oppose to the entente. The young turks movement and revolution that followed plus the war with Greece and the new Republic changed all this.

Therefore this history could be separated unto several periods: Following the early beginnings in 1885-1918, it’s the Republican Period (1923-1935) which prepared the way, with acquisitions, followed by WW2 (1936-1943) and the cold war era from 1944 to 1967 and from 1968. About the latter topic, see the dedicated Cold war Turkish Navy Page.

The first modern Turkish Submersibles

The first two “modern” submarines since 1885 were so during the Republican period. They had been ordered in 1925, completed and commissioned in 1928. In between was a long process. Turkey at the time had no expertise in such construction and the question was who to ask them to built them, knowing that at the time as now, this has an impact on geopolitics and state relations (notably alliances and neutrality stance). Contencious relations with the former entente (France and UK in particular) precluded orders there, as for Italy, it’s stance with Greece before WWI was something to consider. USSR, like Imperial Russia before still was still seen as a potential threat, having close borders and relations would only warm up in the 1930s. That left only Germany, the natural WWI ally for such endeavour, but after a regime change and now under the yaw of the Versailles draconians limitations, was forbidden to built any submarine. Nevertheless, through the German attaché in Istanbul, a prospect soon emerged:

The choice of Ingenieurskantoor voor Scheepsbouw

In 1919 the Versailles treaty imposed that all German U-Bootes would be delivered or dismantled to Britain as approved by Articles 188, 189 and 191, as prepared on 28 June 1919, entered into force on 10 January 1920. The entente nations was then free to pick up existing U-Bootes of their choice (and obviously some were more prized than others), leading to sometimes tense discussions and arbitrations between England, France, USA, Japan and Italy.

The Treaty of Versailles though its Article 191 in addition forbade Germany of the construction or purchase of any submarine even for purely commercial purposes. However the entente ignored the entire infrastructure of technical expertise still there, inherited from German submarine industry. It was requested to hand over existing plans and documentation, but it seems this was never carried out. Not only that, personal employed in these design bureau, now back from military duty, were seen as wasted potential by the new head of the Reichsmarine, Admiral Von Trotha. This, Germany started various activities in order not to lose this expertise, experience and knowledge. Admiral Paul behncke which replaced him and retired from the navy in 1924 setup a complete organization in order not only to no loose this precious potential, but creating an export product that could benefit the country by generating resources and keeping the expertise alight until Germany wouls restart its own submarine production.

To avoid the political troubles by acting against provisions of the Versailles treaty, the Netherlands were chosen to settle a covert German company N.V. or Ingenieurskantoor voor Scheepsbouw (IvS for short) which meant “Engineering Bureau for Shipbuilding Inc.” Basically all engineers that counted in former design bureaus settled there to resume work in 1922, with documentation of former WWI submersible models. They setup an entirely new submarine technology development and application program, completely outside the territory of Germany and the peering eye of French or British inspectors. Once all was ready, a small commercial team started to contact naval attachés in Japan, Argentina, Italy, Sweden, Spain, Finland, Romania, the USSR, China and Turkey, always in a top secret fashion. Since the former entente countries had no spies in neutrals, nothing came out of it.

An order that arrived just in time

Three shipyards were owned by two German companies Vulkanwerft (Hamburg) and A.G.Weser/Krupp (Bremen) as well as Germaniawerft/Krupp (Kiel) with top secret support of the German government, all had invested in the Hague facility by in July 1922 and went over some legal issues causing delays. Thus, IvS started to market its first product by 1925. The design team called “Inkavos” was led by Dr. Hans Techel, and its financial support provided in complete secrecy by the German navy, eager to retain its abilities. Secretly financed, IvS could thank Turkey for its first orders, with the intermediary of Admiral Ernst von Gagern, making this sale happen.

The two Turkish submarines were ordered for one million marks just when the economic conditions of the country started to balance themselves, and it became vitally important for allowing IvS a first sale, enabling more trust from future customers. This was also a was for Turkey to came to the aid of its old ally. But it was not for certain at first, as the IvS sales team had its own priority countries: Argentina, Spain and Italy where they determined a need. When proposals met some resistance at first, IvS entered a financial stalemate to the “Turkish Connection” went at a perfect timing. With this support, Germany at least could see its whole enterprise succeed.

Tractations were all done in pure secrecy, with front companies established for the order, concealing communication between IvS and the German navy such as First Mentor Bilanz GmbH, and from 1927 Igewit 1 GmbH and Tebeg GmbH. Fijenoord received the order, and plans from IvS as a Dutch legitimate business whereas it was fully controlled by Krupp. Ths whole scheme was fully uncovered during the Nuremberg hearings after the war. Part of this operation still had not been fully clarified today.

Development of requirements

Fijenoord shipyard in the Netherlands was to be responsible for this construction. And we can only wonder how Dutch engineers looked at the blueprints that were showing a good old WWI design, UB-III class (see WWI German Uboats).

Lieutenant Atâulllah (Nutku) was one of the important personalities in Turkish shipbuilding industry later, which at the time mentioned in this memoirs some training on construction of future submarines with national designs and requirements. Via contacts at the Hague’s NV Ingenieurskantoor voor Scheepsbouw just opened in 1922, this project, also assisted by other Turkish engineers authorized to draft a basic adaptation of Germany U-Boat designs. This led in 1923 to a set of requirements to be submitted to IvS.

Lt. Nuktu worked at the Fijenoord Shipyard trained by German engineers and technicians from IvS. He also had the opportunity to apply theoretical knowledge acquired later, performing various navigational and diving missions on location. It was not a coincidence he was chosen for this task as an engineer with a German education (spoke fluently German and a bit of Dutch). However once on site he was kept largely in the dark, only taking part to the sea trials and cruise back to Turkey as observer. As he declared at the time:

… me and my friends have not been subjected to any questions, interrogations or examinations since we returned from our studies in the Netherlands, and we have been kept waiting for five months without taking part in any duty…

The fact this order was placed in 1925 reveals possibilities of secret negotiations between Germany and Turkey starting perhaps even after the proclamation of the republic. Werner Fürbinger was assigned to Turkey as a technical attaché as early as 1920 but no heavy equipments could be ships at the time due to the economical conditions of the young republic.

It seems the Turkish requirements were simple and straighforward: Two patrol submarines intended to have the range to criss-cross the Black sea, meaning going from Istanbul to Odessa, Sevastopol, the Kerch strait or as far east as Batumi, and stay on station. In case of war with USSR, at least three large rivers ended there, with the associated merchant traffic. The rest were common specifications for such type of submarine, and Krupp (pardon, IvS) engineers just exhibited the UB-III design which seemed perfectly tailored for the Job (and spared them a lot of efforts):

About the UB-III design

The UB-III were the most produced, last and best “medium” German submarines even developed to that point. The type is frequently cited as the start of a long lineage culminating with the legendary Type VIII when from 1933, all experts were repatriated to Germany and IvS almost took a secondary role. The UB-III was not large, with just 555 t surfaced and up to 684 t submerged, 57.80 m long (189 ft 8 in) with a 40.10 m (131 ft 7 in) pressure hull, 5.80 m (19 ft) wide and 3.85 m (12 ft 8 in) deep. It was powered by 6-cylinder diesel engines developing 1,100 PS (809 kW or 1,085 shp) and electric motors rated for 788 PS (580 kW or 777 shp) on two propellers. Speed was not stellar, just 13.9 knots surfaced and 8 knots submerged.

But they had a range of 9,090 nmi (16,830 km or 10,460 mi) at 6 knots surfaced in the last version (late production boats) or 55 (102 km/63 mi) submerged. They did not dive deep, tested at just 50 m (160 ft), but this was largely enough for the Black sea, which was not that deep either. Armament was classic for the time with a deck 105 mm (4-in) gun, four 50 cm (19.7 in) bow torpedo tubes, one stern of the same and just 10 torpedoes. Just like other countries, Turkey envisioned to acquire also a submarine depot ship or tender.

Design of the Birinci İnönü class

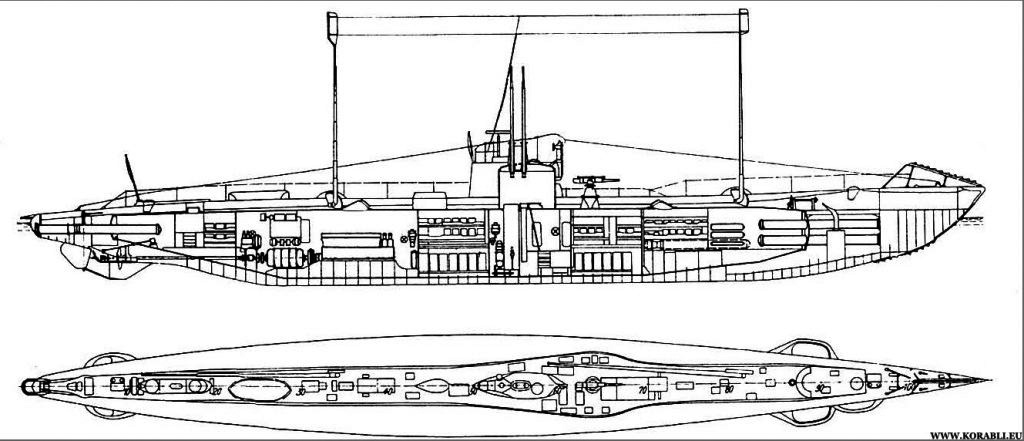

The general scheme of the UB-III type. By default of blueprints, we can guess that the İnönü class was virtually identical, with some minor dimensions changes, new interior detailed fittings, and a different conning tower, which formed the base for all German U-Boats designs to follow.

These first two submarines ordered were called the “First” and “Second” (Birinci, Icinci) battle of İnönü in 1921 which sealed the victory over the Greeks and sealed the fate of the Republic. (and not “number one”, “two” as stated in conways) The UB III class in its final (third planned) evolution in 1918, formed indeed the perfect basis with little revisions if any, ensuring the Turkish admiralty to have these in no time, despite their objections.

The first Turkish submarine therefore pioneered, from a never built planned type, and with the addition of engineering studies made in between, inclusion of recent scientifical and technological progresses, formed the first link in the long lineage that was the Type VII.

Still, these were also prototypes, full of recent R&D not completely created according to exacts demands of the Turkish Naval Forces. We can see here a political good will gesture going over the heads of the latter as it enabled the German Navy to examine design variables for their own future needs, all graciously paid for by Turkey…

Hull and general design

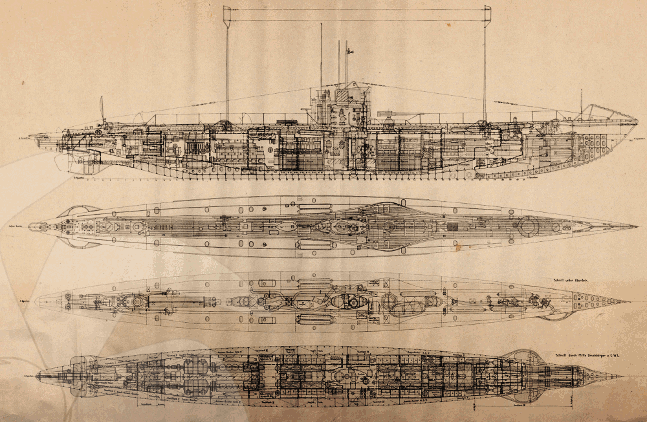

Interior design and top view of the UB-III. Again, we shall see the İnönü class as a faithful repeat, with some adjustments. The torpedo tubes room takes almost 1/3 for the pressure hull’s lenght, separated fro the main (crew) compartment amidships, the crews quarter, central operation room in the middle with the strong conning tower above and built-in periscopes, an its sail on deck. Behind, the galley, the small officers quarter and more crew quarters. Then the third compartment, separated by a watertight bulkhead like the torpedo room, containing the MAN diesels and batteries.

The hull of the İnönü class was 58.68 m long, 5.80 m wide and 3.50 m deep, so the Turkish design was longer by a 80 cm, same beam, and less deep (the original was 3.85 m) to better cope with shallow waters. After all for WW2 standards, these were coastal submarines. The only really distinctive piece (since original blueprints are lost) shows a slightly different conning tower. This had some importance (see later). The structuration was about the same as the UB-III again, with a central inner hull ending with a rectangular section running from the bow, which had moderate flare and was more rounded to improve seaworthiness, and sloped down almost to waterline level. The top of the presure hull was almost flat and covered with anti-stripping serrations.

Powerplant

There was little innovation on this: These had the usual solution of two MAN diesels, rated for 1,100 bhp combined, and two Siemens electric motors for 700 shp resulting in a top speed of 13.5 kts surfaced and 8.5 kts underwater. This was barely an improvement over the UB-IIIs, which reached up to 13.9 knots surfaced and 8 knots underwater.

Armament

It must be said that for treaty-bound peacetime regulations, these submarines had not been commissioned yet when undertaking the long trip to Istanbul. They were armed with was was available in Turkey.

Torpedo Tubes:

The Birinci İnönü class had six tubes, versus five on the UB-III: Four forward, but two aft. We can suppose for the models used that Turkey had no problem picking one of its regular 450 mm (17.7 in) models in the fleet, although there is not much info on that topic. Given the space aboard the torpedo compartment, they had likely ten torpedoes in storage, like for the UB-III. This only authorized for a short campaign, unless there was a supporting tender. Of course by WW2 standard this was a caliber considered completely obsolete. The next Dumlumpinar, Sakarya, and the “Ay” serie were all armed with 21-in tubes. In the 1920s, this caliber was still quite common for submersibles.

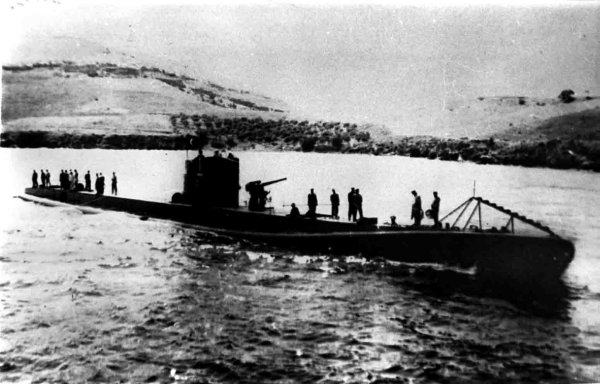

Birinci Inonu, date unknown, showing its deck 75 mm gun in maximal elevation. The CT seems rigid, and there is no trace of the aft 20 mm AA gun.

Guns & AA:

The main deck gun was probably an Italian Ansaldo dual purpose, high elevation 75mm gun (3-in) or the original Vickers model.

The AA consisted in a 20mm autocannon (Oerlikon or Hispano) setup on deck, on a pintle mount aft of the conning tower, as shown in this photo.

Here lays the main difference and innovation of this design compared to the UB-III, which missed an AA gun, and which CT was a bit different.

It must be added that like WWI models, both has a net-cutter installed forward. Two communication cables were hanging from its base, up to the Conning Tower and aft to the poop. Barriers were fitted on each side of the central structure of the inner hull, rectangular with a simple bump to accomodate for the larger stepping platform of the forward deck gun.

Conning Tower:

According to rare photos of the İnönü class, the conning tower design changed over time. This photo allegedly in 1928, shows it only with the lower part of the kiosk, integrating a small chadburn and wheel, when surface navigating, but others shows at least a canvas or metal sheeting above, to protect the crew from the elements, which is found in most photos. It was the same as for the late UB-III type, minus the inclusion of a 20mm AA gun aft, but the latter is little documented, as there are no photos shing the rear part of the CT. In any case, this CT integrates for the forward part a wave breaker and had a flange on top to deal with heavy weather. There were two apertures at the back of the upper portion of the CT for conventional navigation lights (green and red). This photo and this one also shows apparently a “rigid” CT but this one and this one shows rather a white canvas instead, so likely an earlier date. It is true also these “canvas” versions of the CT are associated with a tricolor flag which more resemble the Dutch one than Turkish. Which goes into the hypothesis early tests were done with a canvas-covered CT, which became rigid after they entered service with Turkey, either because the parts to complete the CT were sent in between, or gathered from Germany, or both were refitted in the late 1930s or possibly WW2.

⚙ Birinci İnönü class specifications |

|

| Displacement | 505t surface, 620t submerged |

| Dimensions | 58.68 x 5.80 x 3.50 m (192.6 x 19 x 11.6 ft) |

| Propulsion | 2x MAN diesels 1,100 bhp + 2x Siemens electric motors 700 shp |

| Speed | 13.5/8.5 kts surface/submerged |

| Range | 9,090 nmi/6 knots surfaced, 55nm submerged |

| Armament | 6x 450mm (18-in) TTs (4 bow, 2 stern) 75mm gun (3-in), 20mm AA |

| Diving depth (max) | 60m (196 ft) |

| Crew | 29 |

Birinci İnönü’s class career

The Purchase, Construction and Delivery Process of the 1st and 2nd Inonu was done in the context of a Power Struggle over the Turkish Navy, founded over continuous wars since the Tripoli War, by a newly established Republic of Turkey to cope with immediate geopolitical threats, inherited from the Ottoman Empire. A naval armaments program and large-scale renovation and modernization of existing, “legacy” warships idling in ports for years became priorities. The rivalry between naval and land forces recurred in the Republican Era unfortunately.

The Purchase, Construction and Delivery Process of the 1st and 2nd Inonu was done in the context of a Power Struggle over the Turkish Navy, founded over continuous wars since the Tripoli War, by a newly established Republic of Turkey to cope with immediate geopolitical threats, inherited from the Ottoman Empire. A naval armaments program and large-scale renovation and modernization of existing, “legacy” warships idling in ports for years became priorities. The rivalry between naval and land forces recurred in the Republican Era unfortunately.

The army emerged victorious from the War of Independence and with Kemal Ataturk at the head of state, became the sole authority in the modernization of the armed forces, it therefore shaped the naval program in accordance to their own needs. General Chief of Staff Fevzi Pasha wanted a limited naval program oriented towards coastal defense, with submarines and small ships. Its first traduction were the 1st and 2nd İnonu submarines, largely the product of a land forces-oriented perspective.

Birinci and Ikindci İnönü in service

Birinci and Ikindci İnönü in service

Even before completion, and even long before sporting the red and crescent flag of the young republic, the two submersibles carried an all-German personal aboard to make an extensive serie of close to shore sea trials and navigational tests in the North Sea, testing cruising performances generating extensive reports, all later carried via diplomatic briefcases to Krupp.

At completion, these submarines left Rotterdam on 25 May 1928 for their cruise to be be delivered to Turkey. That cruise was carried out under the Dutch flag, and with a the German crew, plus a few few Turkish observers on board which were just there as passengers. Neither France or Britain had any idea that a German submersible with its German crew and bogus flag were cruising along their coast, from the Netherlands through the channel and to the Gulf of Gascony, the Spanish coast, strait of Gibraltar, coasts of North africa and strait of Messina, up to the Aegeans and Greek coast, and the Dardanelles…

Nothing can be found on the service logs of these submarines, were are left in the dark here, apart the fact they were almost always seen together in photos, and likely based at the Istanbul naval base.

We also know these submarines were modernized in 1940-1941 with German help, allowing them to last a few more years (hence the new style CT shown in some photos). By September 1948 they were outdated and Birinci Inönü was lost on October 17, 1951 in the Black Sea for unknown reasons. Her sister-ship was withdrawn from service on March 14, 1954 due to a fire which wrecked her to such a point the examination team reported the dmage was too extensive at this point to make any repairs worthwile.

At the time, MDAP programs soon procure a new generation of GUPPY types to the naval forces in the frame of NATO. Thus, Ikindci İnönü was broken up soon after. Conways is quite vague on the subject, just telling they were “discarded circa 1950”.

Conclusion: A crucial first step… paid by Turkey

IvS engineers after this well timed Contract for Turkey prove it was able to the task, and soon, Finland, the USSR, Spain, Sweden, Japan, Romania, Argentina and even indirectly Italy looked forward the small Netherlands Company for their own design, with the conditions they would be built in the respectuive customer’s countries. The sum of the knowledge gained in the next submarine types, looely based on customer’s specification sometimes, fit the future Kriegsmarine’s specifications, and gave birth to the coastal Type IIA, the oceanic Type VII and long range Type IX based on all these IvS prototypes. Germany later signed an agreement on 29 June 1935 with Britain to loosen the Versailles conditions, and the first German submarine was built on German soil just five weeks afterwards, all thanks to the ground work made by the Dutch design bureau, which closed its doors before an enquiry could be done.

By allowing Germany to have a new-built UB-III and test limited innovations, the Turkish order enable a long lineag that went through approximately 1,150 U-Boats by 1945. The “numbers” were also probably the most direct ancestors of the Type VII (500-tonnes class). Despite officially Finland was a customer in 1926, Spain in 1928, the sales followed always the same pattern, proposed but first adapted to German needs. The final customers were bacically forced to accept the deal and tone down their own requirements. The Finnish types were the prototypes of the U-Boat Type IIA and the U-25 and U-26 of the 1936 Spanish E1 and Turkish Gür class. The Type I U-Boat was in fact TCG Gür, and this classification was used the first time. Many more would follow until the Type XXI and beyond…

Read More

Books

Conway’s all the world’s fighting ships

Besbelli, Saim, “İki Dost Bahriye”, Donanma Dergisi, Cilt: 69/Sayı: 417, 1957, s. 12-16.

Besbelli, Saim, “İstibdat Devrinin Osmanlı Donanması”, Donanma Dergisi, Sayı: 440, Cilt:76, 1963, s.22-34.

Büyüktuğrul, Afif, “Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Donanması’nın Ellinci Yılı” Belleten, Cilt: XXXVII, Sayı: 148, 1973, s. 497-525.

Büyüktuğrul, Afif, Cumhuriyet Donanması (1923-1960), Deniz Kuvvetleri Yayınları, İstanbul 1967.

Büyüktuğrul, Afif, Cumhuriyet Donanmasının Kuruluşu Sırasında 60 yıl Hizmet (1918-1977), Deniz Kuvvetleri Komutanlığı Yayınları, İstanbul 2009.

Büyüktuğrul, Afif, Osmanlı Deniz Harp Tarihi ve Cumhuriyet Donanması, Deniz Basımevi, İstanbul 1984.

Cemal Paşa, Hatıralar, Türkiye İş Bankası Kültür Yayınları, İstanbul, 2001.

De Groot, Sebastian J., Das Ingenieurskantoor voor Scheepsbouw (Ingenieurbüro für Schiffbau IvS): Ein Wolf im Schafspelz, Brill, Leiden 2021.

Denizaltı Filosu Komutanlığı, Sessiz ve Derinden: Barışın Koruyucusu Geleceğin Güvencesi Denizaltılarımız, Deniz Kuvvetleri Komutanlığı, İstanbul, 2007.

Digital History, The Washington Treaty, https://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.

Dümer, Vehbi Ziya, Denizaltıcılık Tarihine Genel Bir Bakış: 1971/72 Ders Yılı Emekli Amirallerin

Konferansları No:7, Deniz Harp Okulu Komutanlığı, İstanbul 1972.

Fontenoy, Paul E., Submarines: An Illustrated History of Their Impact, ABC-Clio, California 2007.

Genelkurmay Harp Tarihi Başkanlığı, Birinci Dünya Harbi’nde Türk Harbi Deniz Harekâtı, (Cilt VIII), Genelkurmay Basımevi, Ankara 1976.

Grüßhaber, Gerhard, The ‘German Spiritʼ in the Ottoman and Turkish Army, 1908-1938: A History of Military Knowledge Transfer, Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin 2018.

Gün, Taner, Atatürk’ün Donanma Gemileri ile Yaptığı Geziler, (Yayınlanmamış yüksek lisans tezi), Dokuz Eylül Üniversitesi Atatürk İlkeleri ve İnkılâp Tarihi Enstitüsü, İzmir 2007.

Güvenç Serhat ve Barlas Dilek, “Ataturk’s Navy: The Determination of Turkish Naval Policy, 1923-1939”, Journal of Strategic Studies, C.XXVI, No:1, 2003, s. 1-35.

İstanbul Bilgi Üniversitesi Yayınları, İstanbul 2010, s. 223-253.

Işın, İ. Bülent, Osmanlı Bahriyesi Kronolojisi 1299-1922, Deniz Kuvvetleri Komutanlığı, Ankara 2004.

Kalaycıoğlu, Ömer, Denizaltı ve Filomuz, Deniz Kuvvetleri Komutanlığı Yayınları, Ankara 1990.

Mehmet Süreyya, Donanma mı? Şimendifer mi?, Artin Asaduryan ve Mahdumları Matbaası, İstanbul, 1911.

Mercan, Evren, “Osmanlı Donanma Penceresinden Türk-İtalyan Harbi ve Çanakkale Boğazı’ndaki

Müşterek Savunma Konsepti”, Türk-İtalyan Müşterek Harp Tarihi Sempozyumu Bildirileri 21-22 Ekim 2019, İstanbul 2020.

Mercan, Evren, 93 Harbi’nde Deniz Harekâtı, Selenge Yayınları, İstanbul 2020.

Mercan, Evren, Osmanlı Bahriyesi’nde İlk Denizaltılar: Abdülhamid ve Abdülmecid, Deniz Basımevi, İstanbul 2012.

Metel, Raşit, Atatürk ve Donanma, Deniz Basımevi, İstanbul 1966.

Metel, Raşit, Türk Denizaltıcılık Tarihi, Deniz Basımevi, İstanbul 1960.

O’Connell, Captain John F., Submarine Operational Effectiveness in the 20th Century: Part One (1900 – 1939), iUniverse Inc., New York 2010.

Petrucci, Benito, “The “Italian Period” of The Whitehead Torpedo Factory Of Fiume (Rijeka) And The Foundatıon in Livorno Of Whitehead Moto Fides (Wmf – 1945) and of Whitehead Alenia Sistemi Subacquei (Wass –1995)”, s.201-276.

Rössler, Eberhard, The U-Boat: The Evolution and Technical History of German Submarine, Cassell & Co, London 1981.

Saville, Allison Winthrop, The Development of the German U-boat Arm, 1919-1935, (Yayımlanmamış doktora tezi), University of Washington, Washington 1963

Tunaboylu, İskender, Deniz Kuvvetlerinde Sistem Değişikliği, (Yayımlanmamış doktora tezi), Dokuz Eylül Üniversitesi, Atatürk İlkeleri ve İnkılâp Tarihi Enstitüsü, İzmir, 2008.

Türk Deniz Kuvvetleri Tarihçesi 1923-1988, Deniz Müzesi İhtisas Kütüphanesi.

Türk Deniz Kuvvetleri, Türk Bahriyesinin İlkleri, Deniz Basımevi, İstanbul 2014.

Türk Silahlı Kuvvetleri Tarihi, Balkan Harbi Osmanlı Deniz Harekâtı, Genelkurmay Basımevi, Ankara 1993.

Ünlü, Rasim, Atatürk Döneminde Cumhuriyet Bahriyesinin Oluşumu ve Gelişim Süreci, (Yayınlanmamış doktora tezi), İstanbul Üniversitesi Atatürk İlkeleri ve İnkılâp Tarihi Enstitüsü, İstanbul 1996.

Van Dijk, Anthonie. “The Fijenoord-Built Submarines for Turkey.” Warship International, vol. 23, no. 4, 1986, s. 335–40

Links

pigboats.com on UB88

Google books – research on the interwar Turkish Navy

wiki German_Type_UB_III_submarine

On uskudar.biz

On dergipark.org.tr/

On bitmezat.com/

On wowturkey.com

On savunmasanayiidergilik.com

clausuchronia.wordpress.com

Model Kits

None found, but i presume any UB-III with some scratchbuilt work on the CT would do.

UB-III kits: Found only these small 1/700 3-D printed ones on shapeways.

There is however a paper kit from UBoatInfo (1:72 scale !) with 580 parts requiring, about 100 hours to build. It shows the interior structure, the machines, armament, crew and crew space. Full review and photos.

Summary of Turkish Submarines

Birinci İnönü class (Built in NL Fijenoord) launched 29 January 1927, comm. 9 June 1928 (stk 1948)

İkinci İnönü launched 12 March 1927, comm. 9 June 1928 (stk 1948)

TGC Dumlupınar: A version of the Italian Vettor Pisani-class submarine built in CRDA, Monfalcone, launched 4 March 1931, Commissioned 06 November 1931, stricken 1949

Sakarya

Italian modified Argonauta-class submarine built in CRDA, Monfalcone, launched 5 February 1931, comp. 6 November 1931, Decomm. 1949

Gür

Modified U-Boat Type IA built by proxy by the Yard Echevarrieta y Larrinaga, Cádiz, launched 22 October 1930, comm. 29 December 1936, Decomm. 1947

Ay class:

Modified version of the Type IXA submarine built in Germaniawerft Kiel:

-Saldıray: launched 23 July 1938, comm. 5 June 1939, Decomm. 1958

-Atılay: Launched 1938? Comm. 1939? Lost 14 July 1942

-Batıray: Launched 28 September 1938, seized, comm. 20 September 1939 as KMS UA, Scuttled 3 May 1945

-Yıldıray built in Gölcük Naval Shipyard, launched 26 August 1939, comm. 15 January 1946, Decomm. 1958

More on the following classes on the cold war Turkish Navy Page

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign