United Kingdom (1908) – St Vincent, Collingwood, Vanguard

United Kingdom (1908) – St Vincent, Collingwood, VanguardWW1 RN Battleships

HMS Dreadnought | Bellerophon class | St. Vincent class | HMS Neptune | Colossus class | Orion class | King George V | Iron Duke class | HMS Agincourt | HMS Erin | HMS Canada | Queen Elizabeth class | Revenge class | G3 classMajestic class | Centurion class | Canopus class | Formidable class | London class | Duncan class | King Edward VII class | Swiftsure class | Lord Nelson class

Invincible class | Indefatigable class | Lion class | HMS Tiger | Courageous class | Renown class | Admiral class | N3 class

The second dreadnought-type serie

The St Vincent were built in record time, compared to the previous Bellerophon which differed in many details from HMS Dreadnought. However, they still had their share of own differences: Higher upper masts, improved engines, slightly longer and beamier hull which was also shallower and more hydrodynamic, but also 650 tons more in displacement. Moreover, their guns were the new 305 mm Mk.XI, calibre 50. They also received three torpedo tubes and no less than eighteen four-inch (102 mm) Mark III 50-calibre quick-firing (QF) guns.

These ships were nonetheless criticized afterwards for their propensity for excessive rolling, which did not help the watcher’s work. Critics were the same about the positioning of the second mast, handicapped by the smoke from the first funnel, which was eventually suppressed.

Before the war, their crews had just four years to train, as they were accepted in 1909-1910. Apart HMS Collingwood badly damaged on an uncharted rock off Spain in 1911, northing of note happened during that time. During WW1, they spent most of their time idle in the Orkneys at Scapa Flow with the rest of the Grand Fleet. Apart a few sorties for exercises in high seas, this was an uneventful career, that is, until the battle of Jutland. HMS Vanguard however did not end quietly like her sister-ships: At anchor in Scapa flow on July 9, 1917, mishandling of shells turned to drama, with a huge explosion which blasted the hull and sank the ship very fast, taking down to the bottom some 804 men of her crew. That was one of the tragedies that often result in losses not related to any hostile action at sea that every navy experienced.

Background

The Admiralty’s 1905 building plan precise the fleet needed four capital ships FY1907–1908 Naval Programme, but the new Liberal government cut down these by mid-1906. Another was postponed and reported on the FY1908–1909 Naval Programme. This move was also about waiting for the conclusion of the ongoing Hague Peace Convention*. However as it happened, the Germans refused to agree to any naval arms control and the Admiralty waited until June 1907 to decide it wanted a squadron of four same class battleships. Three appeared to be of the St Vincent class, the last one reported on FY1908–1909 Naval Programme (the single HMS Neptune).

*The Hague Peace Conventions of 1899 and 1907 were the first multilateral treaties addressing the conduct of warfare, largely based on the Lieber Code. The 1907 convention (first proposed by Teddy Roosevelt) increased focus on naval warfare, and the British Empire tried to impose limitations, which were mostly refused, by Germany in particular. Among others, this convention addressed the following:

-Legal Position of Enemy Merchant Ships at the Start of Hostilities

-Conversion of Merchant Ships into War-ships

-Laying of Automatic Submarine Contact Mines

-Bombardment by Naval Forces in Time of War

-Adaptation to Maritime Warfare of the Principles of the Geneva Convention

-Restrictions with regard to the Exercise of the Right of Capture in Naval War

-Establishment of an International Prize Court

-Rights and Duties of Neutral Powers in Naval War

Once orders were confirmed, to gain time, it was chosen to just improve on the HMS Dreadnought basic design, and on the preceding Bellerophon class.

Design

The design stayed very close to the Bellerophon class, but with a more powerful artillery and some improvements in armour, and a slightly larger size. Overall, their hull was 536 feet (163.4 m), for 84 feet 2 inches (25.7 m) in beam at normal draught of 28 feet (8.5 m), compared to 160 x 25 x 9 m for the HMS Dreadnought, or 160.3 x 25.1 x 9 m for the Bellerophon class. Displacement went up to 19,700 long tons (20,000 t) normal, and 22,800 long tons (23,200 t) deeply loaded, against 18,120/20,730 tonnes and 18,596 tonnes respectively. They were 650 long tons (660 t) heavier, 10 feet (3.0 m) longer, 18 inches (46 cm) beamier. Their crews were larger too, totalling 755 officers and sailors, expanded up to 835 during WWI.

Powerplant

The St Vincent-class battleships were powered by two Parsons direct-drive steam turbines in a separated engine room, driving four propeller shafts. The outer ones were coupled to the high-pressure turbines, and later exhausted into low-pressure turbines driving the inner shafts, with separate cruising turbines. Steam came from 18 water-tube boilers with oil injectors working at a 235 psi (1,620 kPa; 17 kgf/cm2) pressure. This power plant was rated for 24,500 shaft horsepower (18,300 kW). As designed, top speed was 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph). In sea trials, they all exceeded these figures, at 21.7 knots (40.2 km/h; 25.0 mph) on average, base on an output of 28,128 shp (20,975 kW). In total, 2,700 long tons (2,743 t) coal was stored, plus 850 long tons (864 t) fuel oil sprayed by injectors on the coal to boost combustion. Range was 6,900 nautical miles (12,800 km; 7,900 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). This was much better than the Bellerophon at 5,720 nmi, or HMS Dreadnought at 6,620 nmi.

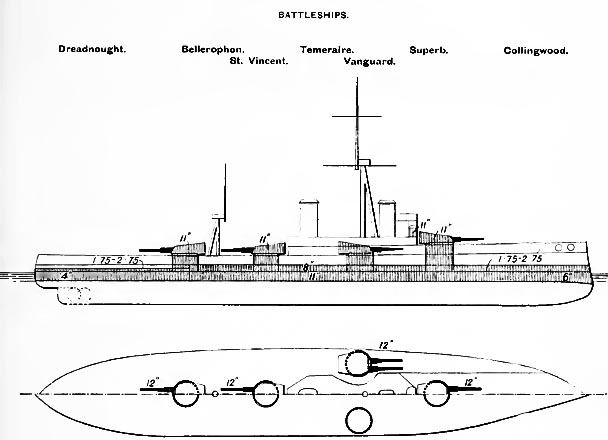

General Scheme, Brassey’s naval annual.

Armament

Main artillery

The Saint Vincent class battleships still carried the same 12-in artillery, but of the 50-calibre breech-loading (BL) Mark XI model. Previous ones were 45 cal., and muzzle velocity went up 75 feet per second (23 m/s) higher. However, they acquired a bad reputation, for drooping at the muzzle, affecting long range. It was however found within normal tolerances, accuracy as stated staying “satisfactory”. The better muzzle velocity allowed the AP shells to penetrated 12 inches of armour from 7,600 to 9,300 yards. It also reduced however the barrel life.

These ten Mark XI guns were placed the same way as on previous battleships, in five deck-level hydraulically powered twin-gun turrets, three axial, two broadside. The forward three were available in chasing, or in retreat combined to the rear turret, and four turrets (eight guns broadside), but one wing turret was lost in any case. These were named ‘A’, ‘X’ and ‘Y’ forward and ‘P’, ‘Q’ aft. Maximum elevation was the same as previous Mark X at +20° for a max range of 21,200 yards (19,385 m). Their standard AP shell weighted 850-pound (386 kg), for a muzzle velocity of 2,825 ft/s (861 m/s). Like previous model, the rate of fire was one shot every 30 seconds (2 rpm). In peacetime, 80 shells were provided by guns, up to 100 shells in wartime.

Secondary artillery

This consisted of twenty 4-inch (102 mm) BL/45 Mark VII guns. They were installed in pairs without shielding exposed on the ‘A’, ‘P’, ‘Q’ and ‘Y’ turrets. The other twelve were positioned in single mounts at deck level on the forecastle and superstructure. Maximum elevation was +15° and range 11,400 yd (10,424 m). They fired a 31-pound (14.1 kg) shell at 2,821 ft/s (860 m/s). Normal provision was 150 rounds per gun and up to 200 in wartime. In addition, four 3-pounder 1.9 in (47 mm) saluting guns were also carried, plus three 18-inch (450 mm) submerged torpedo tubes, broadside and stern, nine torpedoes in reserve.

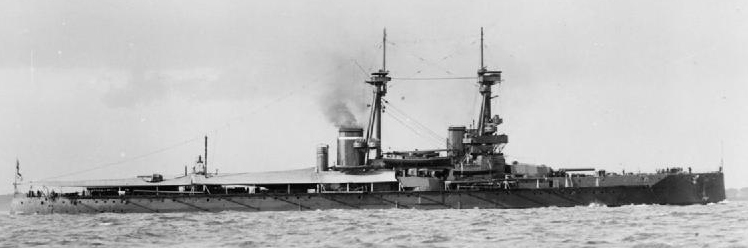

HMS Collingwood after completion

Fire control

Spotting tops on the fore and mainmasts carried these fire control systems. There was a main 9-foot (2.7 m) Barr & Stroud coincidence rangefinder on each of these two control positions. Data from these combined to the target’s speed and course information were fed to a Dumaresq mechanical computer. The solution was electrically transmitted to Vickers range clocks in the transmitting station. The latter was located beneath each gun position on the main deck. Wind speed and direction came through the transmitting station by voice pipe or sound telephone. The range clock displayed the data converted into elevation and deflection for the gunnery officer in each turret. The data was also recorded and displayed on the plotting table for the eyes of the main gunnery officer, with target location prediction. There was a backup, as the ‘A’ and ‘Y’ turrets could take over this task if needed.

Protection

The St Vincent-class waterline belt was made of Krupp cemented armour, 10 inches (254 mm) in thickness. It extended between the outermost barbettes on each end, then tapered down to 2 inches (51 mm) to the ends. It reached in height to the middle deck, and down 4 feet 11 inches (1.5 m) below the waterline. There, it was tapered down to 8 inches (203 mm). There was a strake of 8-inch armour above. Transverse bulkheads were 5-8 inches (127 to 203 mm) thick, closing the main box at the waterline and upper level. The three centreline barbettes had 9 inches (229 mm) thick wells, down to 5 inches (127 mm) below the main upper belt level. The wing barbettes were thicker at 10 inches, but only for their outer faces. The main turret face and sides were equally protected by 11-inch (279 mm), down to 3-inch (76 mm) for the roof.

There were no less than three armoured decks. The thinnest at upper level was 0.75 in, down to 3 inches (76 mm) outside the central armoured citadel. The conning tower walls were 11-inch thick, 8 inches on the roof for the forward CT and 3 inches for the aft one, with 8-in sides. For ASW protection, in addition to compartmentation, there were two longitudinal anti-torpedo bulkheads which were only 1–3 inch (25–76 mm) thick. They extended between the outermost barbettes. Compartments between them were filled with coal.

Service Modifications

HMS St Vincent and Collingwood, were launched in 1908, and HMS Vanguard the next year as planned, in 1909. They were commissioned in May 1909 (St Vincent) and February-April 1910 for the others. Modifications started in 1910–1911 already when the Vanguard’s 4-in roof ‘A’ turret were removed and replaced by a 9/12 ft rangefinder. In 1913, the two others underwent the same modification.

1914 in light of service, they all three saw a reduction of their upper pole height. Later that year, the remaining rooftop guns were replaced by 9-foot rangefinders, protected by armoured hoods on all three. In 1915 two 76 mm AA guns were added, upgraded to 102 mm AA in 1917. In between, in 1916, their anti-torpedo nets were removed. Two smoke deflectors were added to their funnels to reduce smoke interference. Also by December 1915 and May 1916 for the other two, a new fire-control director electrically providing data to a dial was installed. In early 1916, a Mark I Dreyer Fire-control Tables was installed. By 1917, the stern TT was removed. In 1918 a platform was installed on their ‘A’ and ‘Y’ turrets to launch a Sopwith Strutter and a Sopwith Pup.

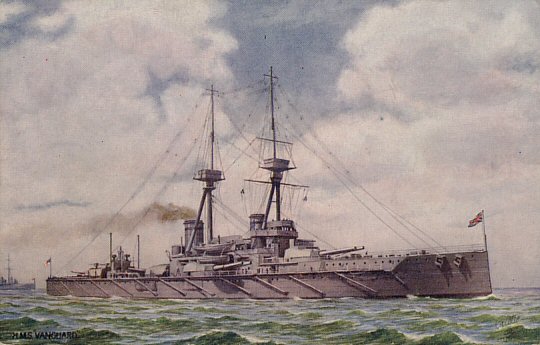

HMS Vanguard – Postcard

Saint Vincent class rendition by the author

St Vincent specifications |

|

| Dimensions | 836 x 84 x 28 ft (163,4 x 25,6 x 8,5 m) |

| Displacement | 19,560/19,700t Standard, 23,030t FL |

| Crew | 758 peacetime – 835 wartime |

| Propulsion | 4 shafts, 2 Brown-Boveri turbines sets, 18 Wagner boilers, 24,500 hp |

| Speed | 21 knots (29 km/h; 24 mph) |

| Range | 6,900 nmi (12,800 km; 7,900 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Armament | 10 x 12-in (305mm) (5×2), 20 x 4-in (102mm), 3 x 18-in (457mm) TTs (sub, 2 sides, 1 stern) |

| Armor | Belt 250, Battery 200, Barbettes 230, turrets 280, blockhaus 280, bridge 75 mm. |

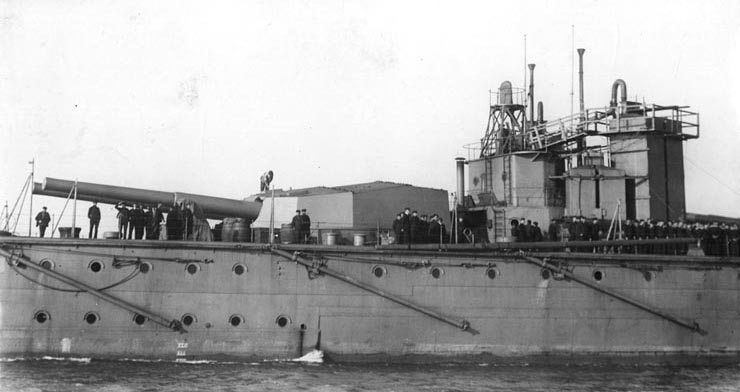

HMS Vanguard aft guns, probably where the tragic explosion took place in 1917.

HMS Saint Vincent (1911)

HMS Saint Vincent (1911)

HMS St Vincent (named after John Jervis, 1st Earl of St Vincent (1735 – 1823)) was commissioned on 3 May 1909. Construction cost was between £1,721,970-£1,754,615. She joined in 1910 the junior 1st Division of the Home Fleet as flagship under command of her first Captain, Douglas Nicholson. She was in Torbay when visited by King George V. She later participated in the Coronation Fleet Review at Spithead in June 1911 and in 1 May 1912 her unit, now renamed the 1st Battle Squadron participated in the Parliamentary Naval Review, on 9 July, also at Spithead. Furthermore, she was refitted afterwards and was back in commission on 21 April 1914, as flagship, second-in-command of the 1st Battle Squadron (Rear-Admiral Hugh Evan-Thomas).

Until 20 July 1914, she was mobilised, and sent to Portland on 27 July, to join the Home Fleet in Scapa Flow. An attack of Imperial German Navy was expected. By August 1914 the Home Fleet became the Grand Fleet (Admiral John Jellicoe) and made a sweep on 22 November 1914 south of the North Sea, St Vincent supporting Vice-Admiral David Beatty’s 1st Battlecruiser Squadron. She sortied again too late for the raid on Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby, and on 25–27 December.

The 1st battle squadron at sea in 1915

HMS St Vincent conducted gunnery drills in January 1915 between the Orkney and Shetlands and, on 23 January, arrived too late for the Battle of Dogger Bank. By 7–10 March, there was a sortie in the northern North Sea, and again on 16–19 March. On 11 April, same in the central North Sea and on 17–19 April, followed by gunnery drills on 20–21 April. Two more sweeps followed on central North Sea on 17–19 May, 29–31 May, gunnery practice on 11–14 June and inspection by King George V aboard St Vincent on 8 July. More training followed and in 2–5 September, a sortie in the northern end of the North Sea followed by training exercises, a sweep on 13-15 October, a fleet training on 2–5 November, before St Vincent was relieved by HMS Colossus as flagship.

She made another sortie with the Grand fleet in the North Sea on 26 February 1916, as it was planned to use the Harwich Force to venture into the Heligoland Bight, although this was thwarted by bad weather. Another sweep on 6 March was cut short y the weather, less for the battleships than the escorting destroyers. The fleet separated during the night of 25 March to support Beatty’s battlecruisers raiding the German Zeppelin base at Tondern. On 26 March it was already over. On 21 April, the fleet was sent off Horns Reef as a diversion while the Imperial Russian Navy laid defensive minefields in the Baltic. They also sortied too late for the raid on Lowestoft and in May, there was another sweep off Horns Reef, also because of a Russian operation. The big test was to come in May 1916, precisely:

St Vincent at the Battle of Jutland

The German High Seas Fleet comprised 16 dreadnoughts, 6 pre-dreadnoughts, sortied from the Jade Bight on 31 May, preceded y Hipper’s battlecruisers. Room 40 intercepted and decrypted radio traffic about this operation, and the Grand Fleet was scrambled, with 28 dreadnoughts and 9 battlecruisers. HMS St Vincent by then was under command of Captain William Fisher. She was part of the 5th Division, 1st Battle Squadron. At 14:20, Iron Duke received signals received incoming strong radio traffic from the High Seas Fleet, signalling its presence. The Grand Fleet, in parallel columns, deployed in a single line at 18:15 with the 5th Division at the rear. St Vincent and the 20th ship, and had to slow down to take her place to 14 knots while battlecruisers took the head of the line. She started firing on the light cruiser SMS Wiesbaden around 18:33. Until 19:00 she turned away twice because of supposed torpedo attacks and ten minutes later started firing on the battlecruiser SMS Moltke. She hit her twice, but the latter managed to disappear into the mist. One apparently ricocheted, striking the upper hull, damaging superstructure and causing some minor flooding. The second penetrated the rear armour, at the aft super firing turret level. The turret was badly damaged and a fire broke up, quickly extinguished. This was all the day. In total, St Vincent fired 98 main shells.

1916-1918

St Vincent joined afterwards the 4th Battle Squadron and made another sortie on 18 August, in position to ambush the High Seas Fleet in the southern North Sea. Both miscommunications and mistakes prevented this, while two British light cruisers were sunk by U-boats and Jellicoe feared to expose his major units in the sector, also because of mines. From then on, the Admiralty won’t risk the Grand Fleet, unless in the remote case the German fleet was escorting an invasion fleet to the coast of Britain, or in case of an engagement under the best conditions. The rest of 1916 and 1917 passed without notable events but training exercises off the Orkney and Shetland islands, close to Scapa.

On 24 April 1918, St Vincent was in Invergordon’s drydock for maintenance when she was ordered with HMS Hercules to reinforce Scapa Flow and Orkneys. Indeed, room 40 intercepted radio traffic from the Hochseeflotte trying to intercept a convoy to Norway. No encounter was made as they arrived too late. St Vincent witnessed their surrendered at Rosyth on 21 November. By March 1919, she was placed into reserve, and gunnery training ship at Portsmouth, flagship of the Reserve Fleet in June 1919 and relieved in December, sent to Rosyth until discarded and sold in March 1921 to Stanlee Ship breaking & Salvage Co., towed to Dover and BU in March 1922.

HMS Collingwood (1911)

HMS Collingwood (1911)

HMS Collingwood in Rosyth 1917

HMS Collingwood was named after Vice-Admiral Cuthbert Collingwood, built at Devonport Royal Dockyard, completed in April 1910 at a cost of £1,680,888/£1,731,640 and commissioned on 19 April 1910. She joined the 1st Division, Home Fleet, with Captain William Pakenham. In February 1911 she damaged her bottom plating on an uncharted rock off Ferrol. She was repaired here and was present for the Coronation Fleet Review at Spithead later. Captain Charles Vaughan-Lee took command on 1 December and in May-June 1912, now part of the 1st Battle Squadron, Captain James Ley assumed command, and she became flagship, under Vice-Admiral Stanley Colville, 1st Battle Squadron. After the Parliamentary Naval Review at Spithead by March 1913, she visited Cherbourg in France, and later she hosted Prince Albert (later King George VI) as a midshipman on board from 15 September 1913. Later she hosted Edward, Prince of Wales, during a short cruise in April 1914 and even a private ship as Colville hauled down his flag in June. But sabre rattling could be heard in the Balkans already.

Until 20 July, HMS Collingwood participated in a test mobilisation (July Crisis) in Portland, and then proceeded to Scapa Flow. In August, this became the Grand Fleet, based at Lough Swilly in Ireland for a time. For the rest, HMS Collingwood took part in the same sorties at sea than her sister-ship St Vincent. No need to dwelve in detail about these. The real test came with the Battle of Jutland:

By 18:00, the Grand Fleet approached the battle, deployed for action, and despite some congestion with the rear divisions, and slowing down some ships to 8 knots (15 km/h; 9.2 mph) to avoid collisions, the battle line was formed. At first, HMS Collingwood fired eight salvos on SMS Wiesbaden from 18:32, while her secondary battery engaged the approaching destroyer SMS G42, but no hits were recorded. At 19:15, HMS Collingwood fired HE shells on SMS Derfflinger, she was hit but escaped in the mist. One exploded on the sickbay and damaged the superstructure. She also fired later on a German destroyer around 19:20, and dodged two torpedoes, missing by 10-30 yards forward. Guns shut for good. This was the last time the battleship would fire them in anger for the remainder of the war. The High Seas Fleet and so did the Grand Fleet, taking its nighttime cruising formation to return home. The great sweep on 1 June, mainly served at spotting and finish off possible damaged German ships, but in vain. HMS Collingwood in total fired 52 AP, and 32 HE shells and 35 secondary shells during the battle, Prince Albert as a sub-lieutenant was commanding the forward turret during the action.

In June 1916, Collingwood joined the 4th Battle Squadron (Vice-Admiral Sir Doveton Sturdee) and took part in two sorties in the North Sea and exercises in between. She received a brief refit at Rosyth in September 1916. On 29 October Sturdee presented the ship her battle honour, “Jutland 1916”, a few days later, Captain Wilmot Nicholson assumed command, replaced soon after by Captain Cole Fowler in March 1917. The 4th Battle Squadron was mostly deployed for exercises. Collingwood was however present at Scapa Flow in July 1917 when her sister ship Vanguard suffered a terrifying magazine explosion. Her crew recovered the bodies of three of her men. In January 1918, she made a sweep off the coast of Norway. Another followed on 23 April. By November 1918, HMS Collingwood was refitted at Invergordon and was not present when the High Seas Fleet surrendered on 21 November. She was slightly damaged on 23 November when scrapping her side with oiler RFA Ebonol. In January 1919, she sailed to Devonport, Reserve Flee, later called Third Fleet, and she became its flagship. She served as a tender to HMS Vivid, a gunnery and wireless telegraphy (W/T) training ship too, later transferred to Glorious on 1 June 1920. She became a boys’ training ship on in September 1921, and paid off on 31 March 1922, sold to John Cashmore Ltd and scrapped in Wales from March 1923.

HMS Vanguard

HMS Vanguard was built at Vickers Armstrong, Barrow-in-Furness shipyard, completed on 1 March 1910 at a cost of £1.6 million and commissioned the same day, Captain John Eustace assuming command. She joined the 1st Division of the Home Fleet, in Torbay during King George V visit, and next the Coronation Fleet Review at Spithead. In September 1911, Captain Arthur Ricardo took command, she was refitted and recommissioned on 28 March 1912, 1st Division, later “1st Battle Squadron” in May. She was refitted again in December, notably to receive in drydock new bilge keels. By June 1913, Captain Cecil Hickley took command. After the summer test mobilisation and fleet review she joined Scapa Flow, and via the Grand Fleet. On 1 September, panic spread as the light cruiser HMS Falmouth spotted a suspected German submarine, which proved untrue. HMS Vanguard also spotted “a periscope”, opening fire at it. This submarine scare was such the fleet was relocated at Lough Swilly in Ireland. Meanwhile, ASW defences at Scapa were heavily strengthened. The rest of her career is similar to other ships of the same unit and her sister ships St Vincent and Collingwood.

1915 saw gunnery drills off the Orkney and Shetland, missing later the Battle of Dogger Bank, others sweep in March and April, and more gunnery drills, again in May, exercises in June and July, a sweep in September, and October and training off Orkney in November. Captain James Dick assumed command on 22 January 1916. Other sweeps followed, often as a backup force for Beatty’s battlecruisers, such as for the German Zeppelin base at Tondern’s raid in March. In April, Vanguard was now part of the 4th Battle Squadron. Followed two versions of operations in favour of Russian operations in the Baltic Sea, and a scramble for the raid on Lowestoft. Next in May was the Battle of Jutland.

Beatty’s battlecruisers managed to bait Scheer and Hipper and draw them towards the Grand Fleet’s battleships. They were deployed into line of battle, and HMS Vanguard ended as the 18th ship from the head of the battle line. She fired 42 rounds on the SMS Wiesbaden at 18:32, claiming several unconfirmed hits. Later around 19:30, she engaged German destroyer flotillas, but it was the last time she fired in the battle, because of poor visibility and Scheer disengaging under the cover of darkness. In total, she would fire 65 HE and 15 AP, plus 10 4-inch shells during the battle. She participated in another sortie on 18 August, but failed to spot the Germans due to miscommunications and mistake while two light cruisers were sunk by German U-boats, prompting Jellicoe to retire the fleet, which from there, would not attempt sorties in the North Sea except for particular circumstances.

Disaster: The Tragic end of Vanguard

She was anchored north of Scapa Flow around 18:30 on 9 July 1917 the crew performing a routine and nothing unusual was recorded before first explosion at 23:20. The battleship sank very quickly such was the damage, and only three of the crew survived, one dying later of his condition. In total, 843 men were lost. This included two Australian stokers from HMAS Sydney onboard the battleship’s brig as well as Captain Kyōsuke Eto, IJN military observer (as part of the Anglo-Japanese Alliance agreements). 17 bodies were later recovered, including Lieutenant Commander Alan Duke, still alive but which died after being rescued. Later others were recovered, buried at the Royal Naval Cemetery at Lyness, with commemorative plaques at Chatham, Plymouth and Portsmouth.

Of course, a Board of Inquiry was constituted for hearings of the many witnesses onboard nearby ships. The consensus was there was a small explosion, showing a white glare between the foremast and ‘A’ turret. It was followed soon after by two much larger explosions that in effect destroyed the ship. The board lacked available evidence (what was left of the shattered hull was at the bottom of the sea) that the explosions were likely to have started in either ‘P’ magazine, ‘Q’ magazine, or both. Fallen debris landed on nearby ships to be collected and analysed as well. Some parts showed no signs of a blast in ‘A’ magazine. In the end, it appeared logical, the explosion took part in the middle of the ship, breaking her in two.

It was clearly assumed to be a detonation of cordite charges. Theories were proposed to explain it, by default of any evidence.

-Some cordite on board temporarily offloaded in December 1916 past its stated safe life, and was prone to spontaneous detonation.

-Some ship’s boilers were still in use and watertight doors open. This could have cause dangerously high temperature in the magazines.

The final conclusion was that a fire started in a four-inch magazine and in chain caused the spontaneous ignition of cordite, which flash-spreading to the other main magazine.

HMS Vanguard’s wreck was eventually salvaged in 1984 for non-ferrous metals but also part of the main armament and armour plate, and declared a war grave. The Wreck and associated debris covers a large area at 34 metres depth. The amidships section is gone, ‘P’ and ‘Q’ turrets lays 40 metres away. Bow and stern are almost intact, as shown by divers in 2016. A full survey report was published in April 2018. It is a protected site, forbidden to divers since 2002. Her loss centenary was commemorated on 9 July 2017 with descendants of the crew laying 40 wreaths above her wreck, and a Union Jack deposed on it, with more ceremonies at the Lyness Royal Naval Cemetery.

Links

Books

J. Gardiner, Robert & Gray, Randal Conway’s all the world fighting ships 1906-1921.

Brady, Mark (September 2014). Part Two. “HMS Collingwood War Record”.

Brooks, John (2005). Dreadnought Gunnery and the Battle of Jutland: The Question of Fire Control.

Brooks, John (1995). “The Mast and Funnel Question: Fire-control Positions in British Dreadnoughts”.

Brooks, John (1996). “Percy Scott and the Director”. In McLean, David; Preston, Antony (eds.). Warship 1996.

Burt, R. A. (1986). British Battleships of World War One.

Campbell, N. J. M. (1986). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting.

Corbett, Julian (1997). Naval Operations. History of the Great War: Based on Official Documents.

Friedman, Norman (2015). The British Battleship 1906–1946. Barnsley, UK: Seaforth Publishing.

Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One. Barnsley, UK: Seaforth.

Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I.

Massie, Robert K. (2003). Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea.

Parkes, Oscar (1990). British Battleships (reprint of the 1957 ed.).

Preston, Antony (1972). Battleships of World War I: An Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Battleships of All Nations 1914–1918.

Tarrant, V. E. (1999) [1995]. Jutland: The German Perspective: A New View of the Great Battle, 31 May 1916 (repr. ed.).

Links

The St Vincent on wikipediaThe st Vincent class at dreadnoughtproject.org

On worldwar1.co.uk

St Vincent class on dreadnoughtproject.org

On navypedia.org

The model’s corner:

–HMS Vanguard 1/1250 Navis Neptun

-Combrig 1/700 St. Vincent class 1910

–The ship on Turbosquid

Video: Tragedy of the Vanguard

.png)

.jpg)

-rear.jpg)

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign