The end of the war to end all wars

Today, 11 November 2018, we remember the sacrifice of an entire generation throughout Europe, four years of a fratricide war that changed the geopolitical maps of the world, toppling empires but also setting up the conditions, unfortunately, for a second, even worst global conflict. This was 100 years exactly day for day.

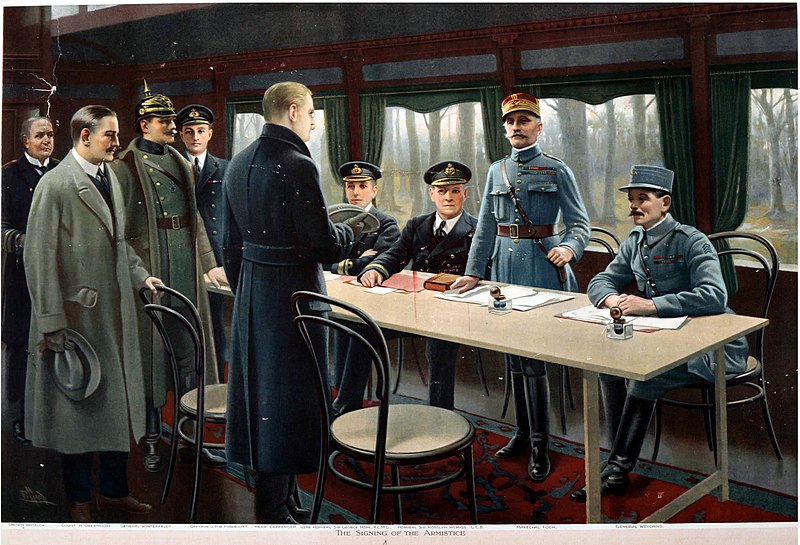

At that day exactly, German delegates signed in a Wagon at Rethondes, in a rush, an unconditional surrender for the German Army. This was the tipping point of several armistices already signed the previous days, taking out of the war the Ottoman Empire, Bulgaria and the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

All three countries will experienced internal troubles, seeing a toppling of regime or dissolution as a political entity. Germany was no exception, thrown into a revolution after the abdication of the Kaiser. But oddly, peace was not signed yet. It would take this first act on 11 November, and three prolongations until peace was officially ratified at 4:15 pm on 10 January 1920.

Indeed, Europe was the object of civilian and military turmoil, with new borders drawn, new countries appearing (like Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia and Poland), and of course the Russian civil war. Allied troops were still fighting the “reds” in 1919. But in this article of course, we will focus on the naval aspects of this armistice.

Previous armistices: The fate of Ottoman and Austrian navies

Of the three central empires, Imperial Germany was the one with the largest navy and the cause of great concerns for the Entente. Together, the Ottoman Turk navy and Austro-Hungarian fleet accounted for a small fraction of this total. On the Entente side all along the conflict, as we saw the previous month and years, the central Empire were dominated head to toes by the entente navies: Not only the Royal Navy, but also the French, US, Italian, and Japanese navies to name a few. In ww2, the Japanese and Italians, both frustrated by the consequences of the armistice, swapped on the other side, which perhaps explains the duration, global character and ferocity of this conflict.

In 1914, the few German squadrons that were not in the Baltic or safely in north sea ports were chased throughout the globe. This led to Graf Spee’s Pacific squadron flee the Pacific to literally roam the oceans, or Souchon’s Mediterranean squadron taking refuge at Constantinople, and swapping to the fez…

For most of the war, the Austro-Hungarian navy was trapped into the Adriatic (hence the Otranto barrage and multiple attempts to destroy it) and the Turkish Navy trapped into the black sea, with a de facto blocus of the Dardanelles after 1915. Of course Germany on her side was trapped into the Baltic, and a blocus enforced, leading to submarine warfare in retaliation. The definition of a total war, as populations were severely affected.

Fate of the Austro-Hungarian Navy

It’s rare and notable when an old empire is dislocated and split between several new countries. Such was the case of the venerable Empire, and naturally, questions were asked about the future of its relatively strong fleet, counting by then three dreadnoughts and most of her high sea capital ships and cruisers still intact, spared for a large scale decisive battle like the Hochseeflotte.

By the end of October 1918, the Austro-Hungarian Army was exhausted and on the verge of mutiny as some minorities rejected the war and commanders sought a ceasefire. The Battle of Vittorio Veneto has been a turning point and triggered a chaotic withdrawal, while discussions started from 28 October onwards. Augmenting pressure, seizing Udine, Trento, and Trieste the Italians threatened to break the truce and the Austro-Hungarians accepted to sign the surrender on 3 November followed the next day by a cease-fire. This was the Armistice of Villa Giusti.

The armistice forced evacuation of South Tirol, Tarvisio, the Isonzo Valley, Gorizia, Trieste, Istria, or Dalmatia, German forces were ordered out, while the Italians would occupy Innsbruck and North Tyrol, followed after the war by an annexation of Trentino-Alto Adige (South Tyrol) (Treaty of London), Trieste and the Austrian Littoral. This, importantly, gave Italy a useful maritime facade for the fleet. Trieste, in particular, was of prime importance.

Treaty of St Germain en Laye: The Empire was disbanded and the new Republic of German-Austria signed on 10 September 1919 a formal treaty of peace. This ratified Italy’s acquisitions of the Austrian Littoral such as Gorizia and Gradisca, Trieste and the March of Istria plus Dalmatian islands which ensure the control of both sides of the Adriatic.

The Treaty of Trianon signed 4 June 1920 at Versailles, effective on 31 July 1921 was a peace treaty with the new Kingdom of Hungary. The Kingdom of Romania, the Czechoslovak Republic, and the Kingdom of Yugoslavia all benefited from large land acquisitions. The Austro-Hungarian navy was disbanded and the army of Hungary was to be restricted to 35,000 men, no conscription, Heavy artillery, tanks, and air force prohibited. Of course, no mention of a fleet was made as the country was landlocked.

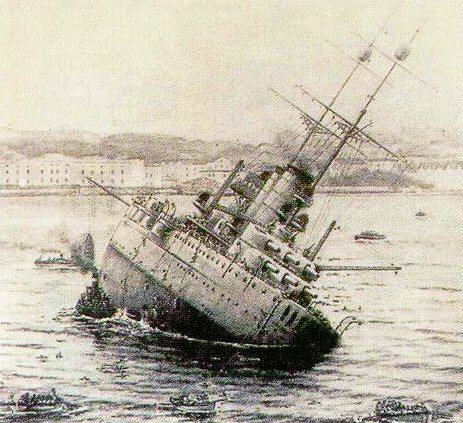

The fleet was mothballed since the 31 October. The Battleship Viribus Unitis, sank by Italian frogmen at anchor, was a freak event while the Empire just gave up the fleet to the newly created State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs. Renamed Jugoslavija she was sunk indeed on 1st November.

Indeed Raffaele Paolucci and Raffaele Rossetti, penetrated Pula with their Mignatta (“leech”), a manned torpedo during the night and their mission started before this transfer occured, so they were unaware of this and the neutrality of the new state (although there were considerable tension between Italy and the new state).

Since both frogmen had no breathing apparatus they were spotted, captured, revealed to the captain the timing of the explosive charges but not their location, and the ship was evacuated. However since the explosion did not occured as planned but 15 min. later, some sailors believing the frogmen were lying, returned to the ship and became fatalities.

The k.u.k. Kriegsmarine’s ships not given to the new state (later unified as the kingdom of Yugoslavia) were turned over to the Entente, that has them mostly scrapped. However many other ships stayed in service up to WW2. One of the longest in service was the monitor Bodrog, now a museum ship. Outside TBs which served with the Yugoslavian and Romanian navies, a handful of riverine patrol vessels survived until 1932. These were the only Austrian ships authorized through the Treaty of St Germain-en-Laye. In addition, three monitors were allocated to Hungary in 1927. The Stör distinguished herself in by greatly contributing to stopping the advance of the Soviet troops during the siege of Vienna in 1945. She survived until 1966.

War Prizes & post war allocations:

- Habsburg, Herzherzog classes: UK, BU Italy 1920-21

- Radetzky class: US Navy control, >Italy BU 1921-26

- Tegetthoff class: 1 Yugoslavia (V. Unitis sunk 1919), Italy BU 1924 (Tegetthoff), France (Prinz Eugen) sunk as target 1922.

- Kronprinzessin coastal BBs class > Italy BU 1922-26

- Monarch class coastal BBs >UK, BU Italy 1920

- Cruisers Maria Theresa, Karl VI, Skt Georg > UK, BU Italy 1920-21

- Cruiser Kaiser Fz Joseph > France, sank 1919

- Panther class> UK, BU Italy

- Tiger> Yugoslavia, scrapped Italy

- Zenta class> UK, BU Italy

- Zara class and other Torpedo Cruisers: Italy, BU 1920

- Blitz class DDs> France BU Italy 1920

- High seas TBs Python class> France BU Italy 1920

- Admiral Spaun class cruisers> UK (BU), Italian Venezia, Brindidi (BU 1937), French Thionville (BU 1941)

- Huszar class DDs > 1 Greece, 7 Italy, 2 France, BU 1920

- Warasdiner> Italy

- Tatra/Ersatz Tatra class DDs> Italy BU 1920

- Kaiman class TBs> UK (BU 1920), Yugoslavia (4)

- Tb 74 T> 4 Romania, Italy, Yugoslavia post-ww2

- Tb 82 F> 3 Romania, 6 Portugal (sold), 3 Greece, 4 Yugoslavia (last BU 1963)

- Tb 98 M> 3 Greece

- Tb I> Italy BU 1920

- Tb VII> Italy 1925-26 (customs)

- Austro-Hungarian submarines: Italy, BU 1920 with exception of Curie (captured, renamed U 14 then ceded back to its original owners)

Fate of the Ottoman Navy

The fate of the Golden Horn Empire was fixed by the Treaty of Sèvres, signed 10 August 1920 by France and the entente countries on one side and Turly on the other. While the Ottoman Army was restricted to 50,700 men, the Ottoman Navy was authorized a force of seven sloops/gunboats and six torpedo boats whose armament was precisely limited. The treaty included an inter-allied commission of control and organisation to supervise the execution of the military clauses.

Turkish signatories at Sevres.

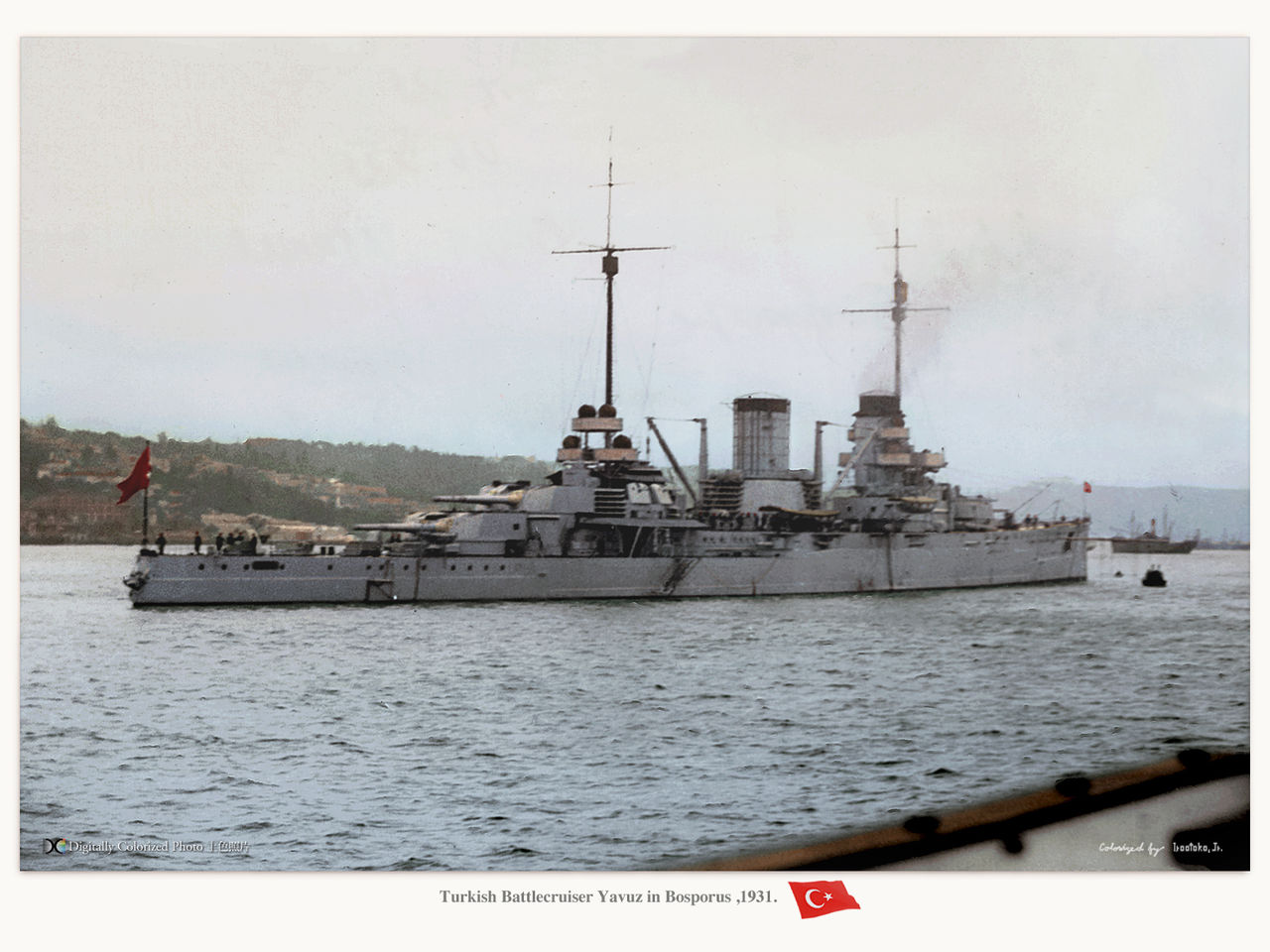

The new Turkish navy flagship, ex-Goeben, Yavuz Sultan Selim, was interned in Izmir under British control. The Yavuz, like the rest of the heavy ships, which were supposed to be given to Great Britain or Japan. But events had the wheel spinning an odd way:

In 1922, Mustafa Kemal (Ataturk) made a coup that ousted Sultan Mohammed VI, starting a revolution and a civil war. Kemal’s own two gunboats took refuge in the Black Sea, then in the hands of “Reds” to avoid capture. While Greek victory was recognized by the Treaty of Lausanne on July 24, 1923, this allowed the release of the Turkish fleet interned in Izmir and saved the battleship Yavuz.

The Yavuz was modernized twice in the interwar at the the Gölcük Naval Shipyard, in 1927 and refitted in 1938. Turkey remaining neutral during WW2, Yavuz was still in service during the cold war and not scrapped until 1973. Indeed, short of the budget to keep her as a museum ship she has been offered to the Federal Republic of Germany in 1963, but the latter declined her. So in short, the Republican Turkish fleet inherited from the prewar Ottoman Navy, but most of the ships were scrapped due to their age and worn-out conditions, not because of any transfer, war prize or obligation. Soon after Turkey started to purchase destroyers and submarines from Italy and Germany and in 1939 it emerged in a generally better shape than in 1914.

Fate of the German Navy

Of course the greatest concern for the Entente was the fate of the largest and most modern fleet within the central powers. This formidable Navy had been quite inactive after the battle of Jutland and maintained idle, but ready, amidst growing discontent and spread of communism.

Last acquisitions of the Hochseeflotte

The Hochseeflotte before the end of 1918 had received many new ships, mostly destroyers and submarines:

-The battlecruiser SMS Hindenburg, completed in October 1917, and considered as one of the best, if not the best battlecruiser ever built and a prototype fast battleship. In addition, work was ongoing on new classes, the Mackensen (launched April and September 1917) and Ersatz Yorck class (four battlecruisers) laid down mid-1916 in Vulkan, Hamburg and other yards, which had their construction halted.

-The new battleships of the Bayern class has been accepted already in June 1916 and February 1917, but the next Sachsen class (31,000 tons, 22 knots, 8 x15-in guns) construction was suspended in 1918. Both ships indeed have been launched in November 1916 and June 1917. But because of manpower issues and material shortages, work had stalled and stopped completely in 1918 and both were later scrapped at Kiel and Hamburg, respectively. No doubt they had been formidable battleships if completed and authorized by the treaty of Versailles. In some way, they were the only reference for engineers that started the Bismarck class design twenty years after.

-Unlike capital ships, cruisers suffered less from late war shortages: The last class was the Cöln (Cologne), 10 ships ordered to various yards and laid down from 1915 to 1916. However if seven were launched, the last, SMS Frauenlöb II in October 1918, only two were completed, Cöln II and Dresden II, in January and March 1918. They saw little service. This new model of cruiser, 7500 tons fully loaded and capable of 28 knots served as an interwar model for the new KMS Emden, with few improvements.

-The bulk of the efforts were seen in light ships, destroyers or “Hochseetorpedoboote“. The large and innovative S113/V116 class, B122, V125, G148, V158, H166, V170, S178 and H186 classes were either never completed, or cancelled.

-The last classes of German WWI submarines were the U-115, 127, 142, 151, 213 and 229 cruiser submarines, or the large-scale UB 48 (which inspired clandestine interwar designs in Holland), of which 130 were planned and 92 delivered before the war ended, like the UC 80 minelaying type (25 out of 115 completed).

The first mutiny: Scheer’s aborted last offensive

Hochseeflotte’s last battle

History retains Jutland as the last major naval battle for the Royal Navy and German Navies, but after month of inaction and idleness, sensing the crew’s morale were quite low after the bad news of the front, and under pressure of the general staff and the Kaiser planned an all-out, last-ditch offensive with all the Hochseeflotte. The plan was elaborated a bit like than for Jutland. This was still about drawing a part of the Royal Navy on an ambush laid by submarines, but seeking direct confrontation this time with the bulk of the fleet and not a single battlecruiser squadron for a decisive victory without waiting for capital ships to arrive. Confidence indeed has been restored after Jutland over German ships’ resilience and exposing also British deficiencies. It should be noted the Hochseeflotte performed three sorties since Jutland: one on 18–19 August 1916 (The RN lost two cruisers), 18-19 October 1916 (SMS Munchen shelling of Sunderland), and 22–25 April 1918 (SMS Baden failed convoy interception)

The battle has been for obvious propaganda reasons presented as a German victory. Yet, the head of staff preferred not to risk the bulk of the fleet in another large battle. But by late 1918, desperation grew while morale sank, sailors, knowing about the suffering of the civilian population because of their inaction with the naval blockade and resenting their absence of commitment compared to the Infantry. Sensing this, and gradual consequences of the Soviet revolution and spread of communism in the Navy, added to a general discontent over the regime, Scheer planned the naval order of 24 October 1918.

Preparations

It happened just when notes were exchanged with the US Government about a cessation of hostilities, one conditions being the cessation of submarine warfare. Therefore all U-boats at sea were recalled on 21 October. However the day after, Scheer ordered Admiral Hipper to prepare for an attack on the British fleet, with the main battle fleet and using the available U-boats. Details and final plans were approved by Scheer on 27 October and the Hochseeflotte concentrated at Schillig Roads off Wilhelmshaven in preparation. In addition, the Germans had now fine-turned their intelligence and their communications were much harder to break. They had been in April 1918 able to launch massive surprise sorties against convoys off Norway.

The order implied the Hochseeflotte was to sail to Hoofden, due south, attacking combat forces and mercantile traffic on the Flanders coast and Thames estuary. This was supposed to draw the British Fleet toward the line Hoofden/German Bight. On day II of the operation, local forces were supposed to be engaged by torpedo-boats during the night of Day II or III while the northern grand fleet approach routes (from Scotland) up to the area of Terschelling were infested by mines and ambushing positions by submarines.

In total, 25 U-boats were to be deployed in six lines in the southern North Sea. However the days of their deployment four U-Boats were sunk. The British Admiralty was soon informed of the concentration and prepared for a possible emergency sortie.

Mutiny and Cancellation

On the afternoon of 29 October the fleet was busy preparing for sailing the following day, 30 October. Official communications used in deception mentioned a training sortie. The raid on the Thames and the Flanders Coast were scheduled for 31 October. A large scale battle was expected in the afternoon to evening. However in the evening of 29 October unrest and serious acts of indiscipline multiplied: The men became convinced their commanders were intent on sacrificing them, to sabotage the Armistice negotiations.

Stokers failed to return from shore leave on two battlecruisers, while mass insubordination happened on four dreadnoughts and outright mutiny erupted in König, Kronprinz Wilhelm and Markgraf. On Baden also, officers were on their guard as the crew was restless and agressive. Mutiny indeed affected mostly large ships, whereas the crews remained quiet on smaller ships. Because of the fear of an all-out uprizing and the safety of officers, Admiral Hipper decided to cancel the operation on 30 October. He also ordered the fleet to disperse. On 3 November there was another large scale mutiny in Kiel, and ships of the 3rd battle squadron pointed their guns on the rebellious vessels. But this unrest was not over. The last act occured in 1919, in Scotland…

The end of the Hochseeflotte

Consequences of the Treaty of Versailles for the German Navy were not fixed when negotiations commenced on 18 January 1919 at the Quai d’Orsay, the diplomatic quarter in Paris. 70 delegates from 27 nations participated minus Russia, which had a separate peace signed at Brest-Litovsk on 3 March 1918. In addition to the loss of German colonies, Lloyd George wanted to neutralize the German navy, in order that the Royal Navy could keep her advantage.

Soon however the new country was allowed to keep a glorified coastal naval force: Six pre-dreadnought battleships (of the 1904 Deutschland vintage) and six light cruisers (capped to 6,000 long tons (6,100 t)) plus twelve destroyers (capped to 800 tons) plus twelve torpedo boats (200 tons). Of course, strict interdiction to study and built submarines.

Manpower was reduced accordingly to 15,000 men, which comprised not only the crews, but coastal defenses, signal stations, and administration with no less than 1500 officers. In addition, the remainder of the fleet was to be surrendered: Eight modern battleships, eight cruisers, forty-two destroyers, and fifty torpedo boats while thirty-two auxiliary ships were converted back as merchant vessels.

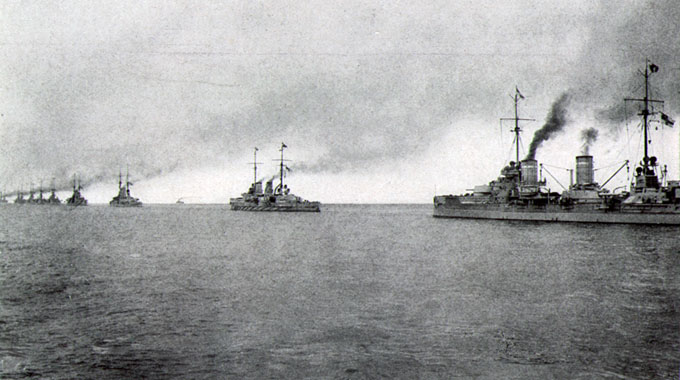

On 12 November 1918, instructions were sent to the German HQ to ready the Hochseeflotte for a departure on 18 November to an indicated place where she could be on guard, pending her fate. The threat was for the British to occupy Heligoland. Three days after, Rear-Admiral Hugo Meurer (Hipper’s representative) went on board HMS Queen Elizabeth to see Admiral David Beatty and receive instructions. U-boats were to sail at Harwich, the closest convenient place for short-range subs, placed under supervision of Rear-Admiral Reginald Tyrwhitt’s Harwich Force. The surface fleet, the Hochseeflotte, was to sail with a reduced crew to the Firth of Forth at the Grand Fleet’s naval base of Scapa Flow north of Scotland.

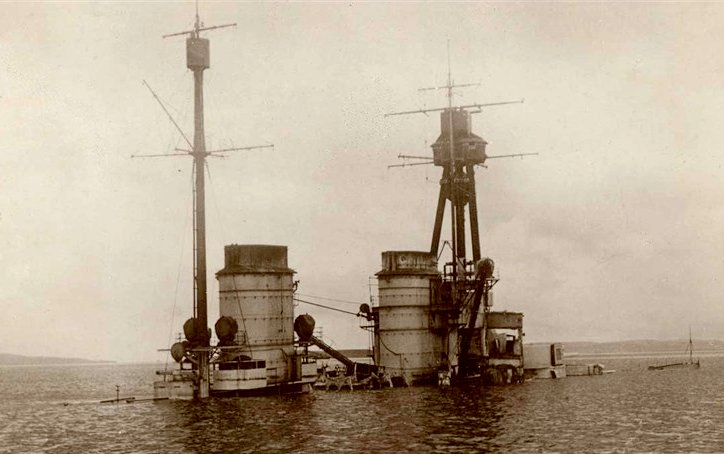

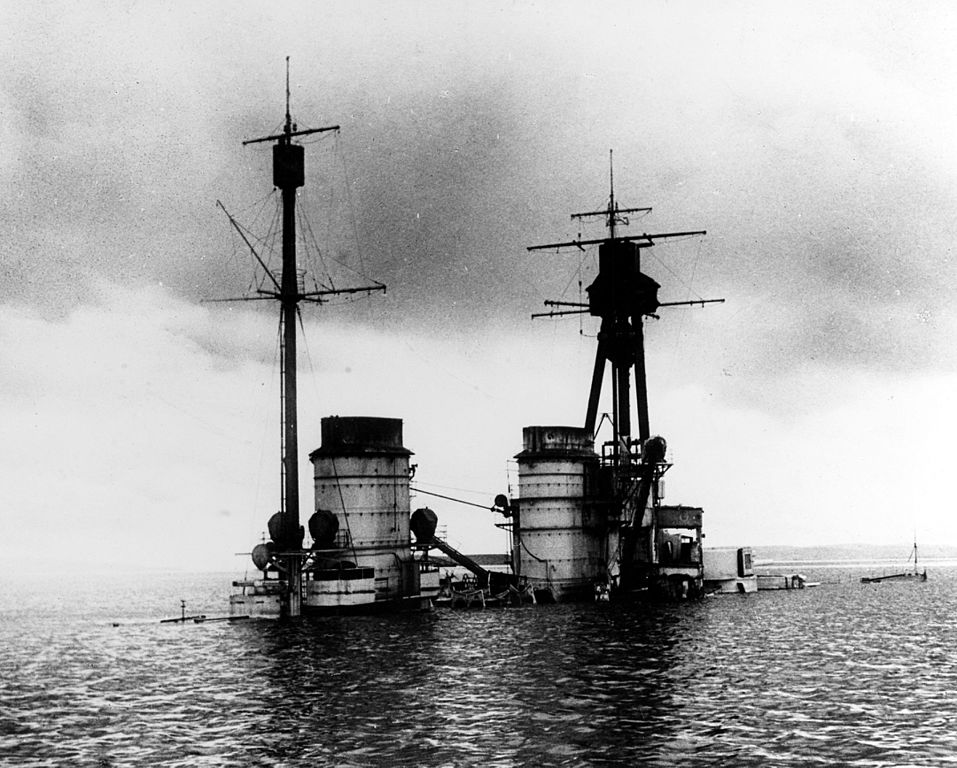

Hugo Meurer temporized, knowing the mood of the sailors. He did not want a refusal and outright mutiny. In the following days from 20 November until the next year, 176 U-Boats sailed and were interned to Harwich. The 21, the 70 most significant ships of the fleet destined to be handed over were led by light cruiser Cardiff to Scotland. That was an exceptional sight. However the battleship König and light cruiser Dresden were left behind because of engines problems; The last Hochseeflotte ship sank by a mine, yet in peacetime, was the V30, during the dangerous crossing. When the fleet eventually arrived at Scapa, they were guarded by an armada of about 270 British and allied ships. David Beatty signaled the Hochseeflotte to then anchor in respective sites along the bay and the German flag be hauled down. Battleships and cruisers were placed north and west of the island of Cava and later the König and Dresden joined in.

Captivity was grim for the crews: The lack of discipline, poor morale, idleness, the terrible weather, poor food from seldom arriving Germany, lack of news from home, led to the ships to be in a state of “indescribable filth for some of the ships” according to British officers. At the head of this jailed fleet, Rear-Admiral von Reuter soon requested his flagship to the be the SMS Emden on 25 March 1919 as he was regularly prevented to sleep by the “red guard” sailors night rambling and stomping. To avoid further disturbances, crews were conducted back to Germany (only more loyal crews remained), at a rate of about 100/month. In total, only 4,815 men were left to take care of the ships.

This was a skeleton crew in charge, pending the fate of the Hochseeflotte at the Paris Peace Conference. Crucially Article XXXI of the Armistice precised that the Germans were not permitted to destroy their own ships, that were to be either destroyed by the British or sent as war reparations. However Von Reuter started to prepare the scuttling o his ships, and effort in this sense redoubled after May 1919. Further instructions in this way came later from Admiral Erich Raeder.

In June, when it was clear to Admiral Madden that the German intentions were precisely to scuttle the ships, he devised a plan to seize them. The date of the operation was planned to be midnight of 21/22 June, corresponding to the treaty of Versailles signed and entering the application. However, the first battle squadron departed for an exercise, planned to returned on 23 June in order to carry out the order, later than planned.

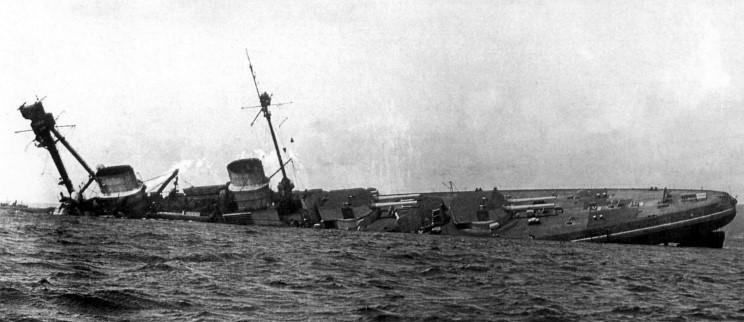

It was precisely at this moment that Von Reuter gave the famous order to scuttle the fleet at 10:00 a.m. on 21 June 1919, when there were only a few destroyers left at Scapa Flow. This was immediately carried out. It was not performed by explosive charges but simply by opening seacocks and flood valves and let water flow in unrestricted by watertight compartment or doors. In addition, the crews bored holes through bulkheads to speed things up. British crews were not aware of this until seeing the Friedrich der Grosse starting to list heavily to starboard. Soon also, flags were hoisted to the masts, the old Imperial German Ensign. Crews were also ordered to abandon ships.

Fremantle receiving news of the scuttling at 12:20 and immediately ordered the fleet to turn back. He arrived just when major ships were still afloat and immediately ordered the ships to be boarded and beached if possible. The last capital ship to sink was the battlecruiser Hindenburg at 17:00, which gently sat straight underwater, while Baden also sank in shallow waters and remained largely unaffected by the scuttling. A British crew was able to beach her soon after. Other ships sank in deeper waters and capsized, preventing any recuperation.

Since this was in violation of orders and almost an act of war, German crews rowing to land were shot on sight by British ships. In all, nine Germans sailors were killed, sixteen wounded, the last “wartime” casualties of the Hochseeflotte which cased to exist as a fighting force. This would remain the largest fleet scuttling in history, and the largest fleet Germany ever had, the dream of grandeur of Kaiser Wilhelm II.

Reactions to the scuttling were mixed. The French were disappointed, counting on some recent ships acquisition, while some British officers saw it as a “blessing”, not willing to have long and painful negotiations for redistributions. Admiral Reinhard Scheer, of course, rejoiced about the regained honor. Not all the fleet was lost, however. 15 of the 16 capital ships were, 5 of the 8 cruisers and 32 of the 50 destroyers effectively sank, but the others were at least partially afloat and did not need a lot to be towed to safety and sailing again under a short notice.

All these hulls did not hamper navigation that much since Scapa flow bight was quite large and the ships were relegated in a specific corner. But it would take time to recover these ships of possible and have them towed to breakers or broken in situ. Refloating them, even for the value of scrap metal, was not seen as interesting since so many ships already obsolete or useless war reparations were already sold for scrap.

The only motivated endeavor was from entrepreneur Ernest Cox which managed to purchase and refloat 26 destroyers, two battlecruisers, and five battleships. The remainder of the hulls rested there until the 1980s, classed as archeological remains. They are laying in depths up to 47 meters (154 ft) and can be still visited today by divers if that was not for the poor weather and cold. Probably the most interesting remain had been the battlecruiser Hindenburg, which was visited by Royal Engineers and studied carefully. They discovered the quality of internal compartmentation and armor scheme. It is said that reports helped to design some details on following “super-dreadnoughts” or fast battleships after the Nelson.

War reparations:

Since not all ships have been lost, war reparations were possible but concerned mostly cruisers, destroyers and submarines left home. Only the Baden survived only to be used by the UK as a target ship. However, France acquired the Emden, but she was in such poor state she was not repaired and broken up in 1926, as well as the destroyer V26 and V100. most surviving ships given to UK, USA, and Japan were soon broken up. However, there was still a flurry of intact U-Boats at Harwich, that ended in the French and Italian navies, including some U-Boats to the USA. The U-boats, in particular, had considerable design influences. The interdiction to built new ones was not respected very long: From 1926 onwards, Germans engineers installed a design bureau in the Hague in the Netherland, and planned export to finance their research. They secretly designed submarines for Sweden, Norway, the Soviet Union, Spain, Finland, and Turkey gaining valuable experience in the process, helping to design new models from 1937.

Read More

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Armistice_of_11_November_1918

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiel_mutiny

- https://www.historytoday.com/richard-cavendish/german-battle-fleet-scuttled-scapa-flow

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Naval_order_of_24_October_1918

- https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-30128199

- https://royalarmouries.org/stories/our-collection/der-tag-the-day-the-german-high-seas-fleet-surrendered/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scuttling_of_the_German_fleet_at_Scapa_Flow

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Armistice_of_Villa_Giusti

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign