Development: Replacing the “Kate”

In 1942 at Midway and before that at Cora Sea and in many other operations including Pearl Harbor, the Nakajima B5N (allied code “Kate”), proved to be the successful first line aircraft carrier torpedo bomber of the Imperial Japanese Navy. But its original conception dated back from 1936, under the direction of Katsuji Nakamura. Very modern for its time, it was obsolete in 1941, as its first limitations already appeared in 1938 over China. By December 1939 a Navy specification to Nakajima was issued for the “14-Shi Carrier Attack Aircraft”, capable of carrying the same load as the B5N and same three-man crew, cantilever all-metal construction, but this time with a top speed of 250 knots (460 km/h; 290 mph), cruising speed of 200 knots (370 km/h; 230 mph) and 1,000 nmi (1,900 km; 1,200 mi) range, with the standard 800 kg (1,800 lb) bomb load and 2,072 nmi (3,837 km; 2,384 mi) in taxiing conditions, without armament.

In 1942 at Midway and before that at Cora Sea and in many other operations including Pearl Harbor, the Nakajima B5N (allied code “Kate”), proved to be the successful first line aircraft carrier torpedo bomber of the Imperial Japanese Navy. But its original conception dated back from 1936, under the direction of Katsuji Nakamura. Very modern for its time, it was obsolete in 1941, as its first limitations already appeared in 1938 over China. By December 1939 a Navy specification to Nakajima was issued for the “14-Shi Carrier Attack Aircraft”, capable of carrying the same load as the B5N and same three-man crew, cantilever all-metal construction, but this time with a top speed of 250 knots (460 km/h; 290 mph), cruising speed of 200 knots (370 km/h; 230 mph) and 1,000 nmi (1,900 km; 1,200 mi) range, with the standard 800 kg (1,800 lb) bomb load and 2,072 nmi (3,837 km; 2,384 mi) in taxiing conditions, without armament.

Long story short, the Nakajima B6N Tenzan (“Heavenly Mountain”), Allied reporting name: “Jill” was planned as the new standard carrier-borne torpedo bomber but due to its protracted development, it entered service only by August 1943, and the shortage of experienced pilots combined to US air superiority meant it was never able to fully demonstrate its combat potential, despite being infinitely superior to the “Kate”. Amazingly, its replacement was planned already in 1941 (first flight in May 1942) but only appeared by late 1944, the Aichi B7A Ryusei “Grace”. Apart from IJN Shinano, sunk in her first sortie for fitting out, the latter and the B6N, only operated from bases at that stage. In addition, the B7N was not strictly speaking a “torpedo bomber” but a universal “attack plane” to also replace the Yokosuka D4Y “Judy” dive bomber and streamline war production. This made the B6N the very last specialized torpedo bomber of the IJN. Its first prototype actually flew in March 1941, so it could have been ready at the time of Pearl Harbor, but alas, it was only introduced from the summer of 1943.

Long story short, the Nakajima B6N Tenzan (“Heavenly Mountain”), Allied reporting name: “Jill” was planned as the new standard carrier-borne torpedo bomber but due to its protracted development, it entered service only by August 1943, and the shortage of experienced pilots combined to US air superiority meant it was never able to fully demonstrate its combat potential, despite being infinitely superior to the “Kate”. Amazingly, its replacement was planned already in 1941 (first flight in May 1942) but only appeared by late 1944, the Aichi B7A Ryusei “Grace”. Apart from IJN Shinano, sunk in her first sortie for fitting out, the latter and the B6N, only operated from bases at that stage. In addition, the B7N was not strictly speaking a “torpedo bomber” but a universal “attack plane” to also replace the Yokosuka D4Y “Judy” dive bomber and streamline war production. This made the B6N the very last specialized torpedo bomber of the IJN. Its first prototype actually flew in March 1941, so it could have been ready at the time of Pearl Harbor, but alas, it was only introduced from the summer of 1943.

Evolution

The B5N weaknesses were already reported and known in the Sino-Japanese War so the IJN planned a longer-ranged replacement already in early 1939. It’s in December 1939 that a specification to Nakajima (no competition, a successor was looked out there) for a Navy Experimental 14-Shi Carrier Attack Aircraft able to carry the same weapon load, but with greater performances across the board. A crew of three was kept, with outside the pilot, a navigator/bombardier and radio operator/gunner, bith vital for operation across the Pacific Ocean, with only water from horizon to horizon). Of course on the technological standpoint, same low wing, cantilever and all-metal construction, with some surfaces still fabric-covered to save strategic materials. For performances the naval staff wanted a top speed of 250 knots (460 km/h; 290 mph) and a cruising speed of 200 knots (370 km/h; 230 mph) for a range of 1,000 nmi (1,900 km; 1,200 mi) with its 800 kg (1,800 lb) bomb load and in ferry mode or reconnaissance, a range of 2,072 nautical miles (3,837 km; 2,384 mi) without payload.

The Navy also wanted the installation of the proven Mitsubishi Kasei engine, but Engineer Kenichi Matsumara proposed instead to adopt the new 1,870 hp (1,390 kW) Mamoru 11, 14-cylinder air-cooled radial. It was more powerful, but also had a lower comparative fuel consumption plus was more flexible in regimes at all altitudes. This proposal however, adopted on paper, proved a liability in practice as the promising Mamoru proved very troublesome and its development lagged for more than two year, also never reaching the expected power rating. In the end, this delayed the B6N for two years…

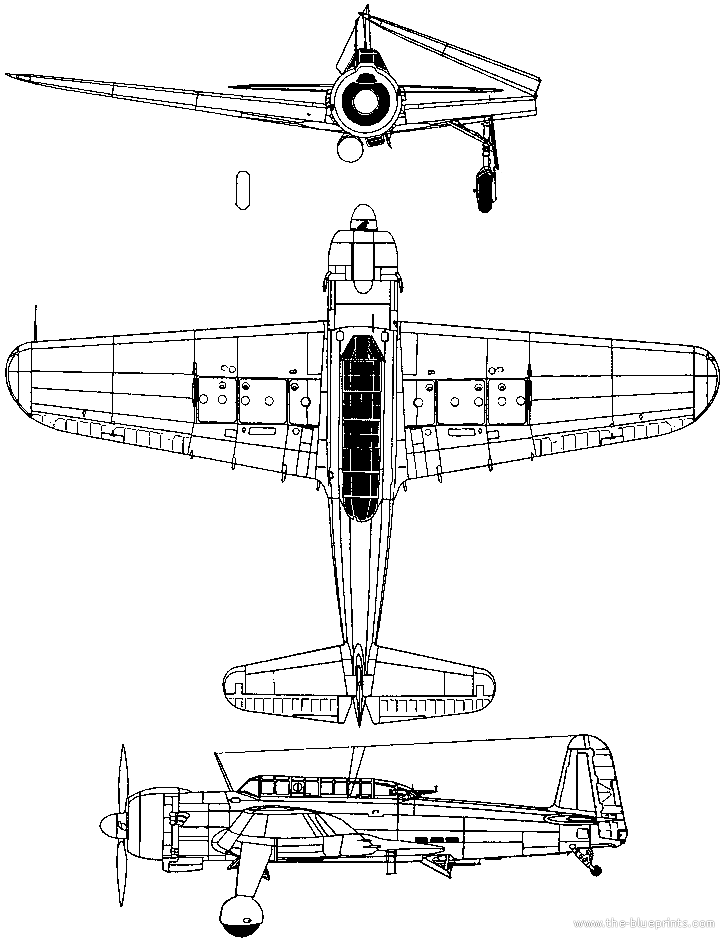

Designer Matsumara was obliged by the Navy in between the find compromised for the wing folding, in a span and area similar to the B5N and overall length of 11 m (36 ft). This made the new model looking unbalanced with a relatively low wingspan compared to the fuselage (and thus, given the poor performances of the engine, higher wing loading, heavier controls), as well as its swept-forward tail fin and rudder. The outer wing panels were hydraulically folded, and like on the B5N and they allowed the model to be reduced to 6.3 m (21 ft) in wingspan. To lessen increased wing-loading Fowler flaps were installed, of such a large are they could extend well beyond the wing’s trailing edge for extra lift especially when landing. They were placed an angle of 20° in take-off, 38° when landing. Still, the B6N had a higher stall speed compared to the nimbler B5N.

Teething issues

The prototype B6N1 maiden flight was on 14 March 1941 at the Nakajima Test airfield, and the testing program was interrupted many times as defects after defects were discovered. Test pilot discovered the prototype had an alarming tendency to roll while in flight due to the extreme torque of the four-bladed propeller. To compensate, engineers at Nakajima thinned down the tail fin, then moved 2 degrees, ten minutes, to port to compensate. After handling characteristics were far better. The B6N1’s Mamoru 11 engine was a constant source of pain. It displayed severe vibrations as well overheating on some (many) regime speeds. So much reports accumulated on this power unit than the Navy judged too unreliable for service. A second prototype was built with many revisions, and both will go on until the end of the tests phase.

Engineers at the engine departement under the whip of Matsumara made all ranges of modifications over the very long trials period, until it reached a base level of reliability, at least enough to motivate a production, knowing there will be further improvements on the long run and more data with the first batches. Official Acceptance Trials started by the end of 1942, so after nearly two years of ironing out defects. This was completed by test flights aboard the carriers IJN Ryuho and Zuikaku. Reports indicated the need to strengthen the tail hook mounting. To compensate for the lack of lifting capabilities at full weapon load, some suggested to use RATOG (rocket-assisted take-off gear). Several early batches of B6N1s were tested with these to serve on smaller carriers, but it was not adopted in the end.

Production Greenlighted

The B6N1 was officially approved in early 1943 under the name “Navy Carrier Attack Aircraft Tenzan Model 11”. As soon as it appeared, US intel attributed the letter J to this model, thus it became the “Jill” in USN nomenclature. After a prototype pre-production batch helping curing many operational issues, the late models obtained a flexible Type 92 machine gun in a ventral tunnel, at the rear of the cockpit, in addition to the single Type 92 plus a 7.7mm Type 97 in the port wing, deleted after the 17th in line.

Another measure was taken after several torpedo launches, consisting in angling the torpedo mounting rack 2° downward. The torpedo was maintained also by stabilization plates and measures were taken to prevent it from bouncing at low-altitude release, as well as strengthening the main landing gear. Also, the designers proposed at this stage to used heavier but much safer self-sealing fuel tanks. However the Navy seeing the 30% drop in fuel capacity rejected it outright.

Evolution

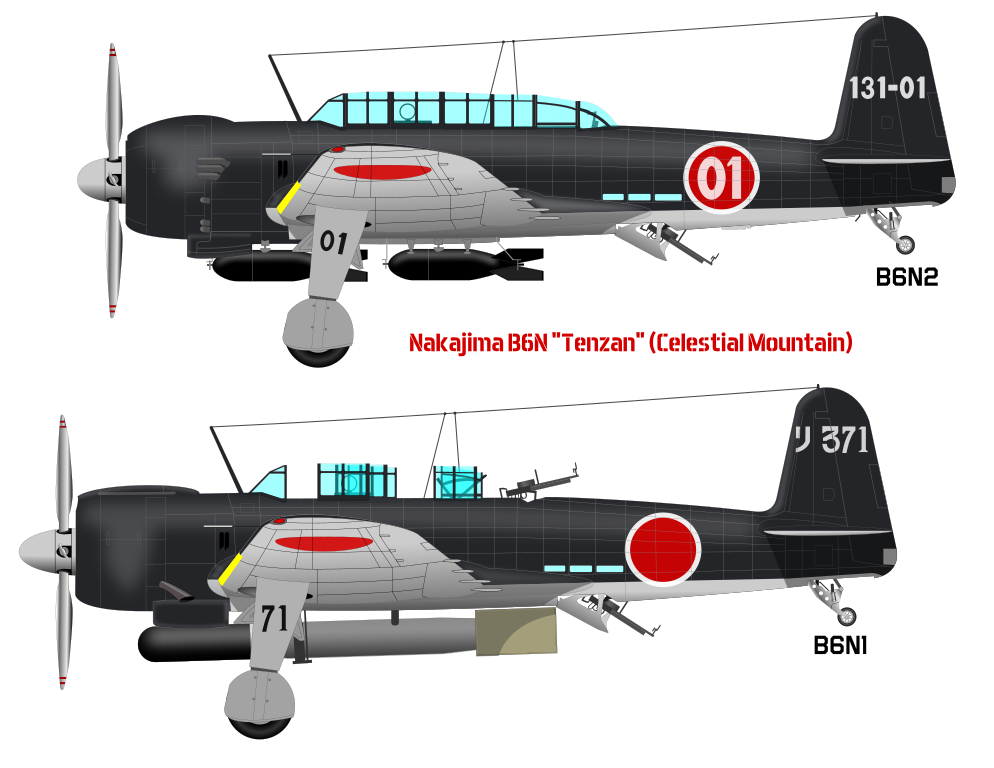

B5N2

After only 133 B6N1s were delivered by July 1943, the Japanese Ministry of Munitions intended at enhancing standardization across the board, ordered Nakajima to put an end on the Mamoru 11 engine and forced the adoption of the new 18-cylinder Nakajima Homare engine 1,850 hp (1,380 kW) or in the meantime the already available Mitsubishi MK4T Kasei 25 engine, the one chosen by the Navy in 1940. The advantages were that the Mamoru 11 and Kasei 25 were similar in size. Only differences were a nose extension to maintain the center of gravity, plus minor alterations such as oil cooler and air intakes on the cowling. So by late 1943, the immense majority of IJN torpedo bombers were still the venerable B5N2, soldiering until 1945.

To combat torque, it was decided to adopt a smaller, 3.4 m (11 ft) diameter, yet still four-bladed propeller. It was to go with a smaller spinner, with some weight-savings, notably the now fixed tailwheel, in down position. Both initial single exhaust stacks were replaced by a serie of multiple smaller stubs. It allowed to low glare at night and participated to a small gain in forward thrust. This resulted in the greenlighted production of the largest production run, the Carrier Attack Aircraft Tenzan Model 12, B6N2.

Production started at the fall of 1943, with one every three plane being fitted with a 3-Shiki Type 3 air-to-surface radar, quite a novel addition in the IJN, for night combat or poor visibility attacks. Maintaining radio communication, flights of three planes would rely on the radar data of the flight leader for guidance. Yagi antennas were placed on the wing leading edges, protruding from the rear fuselage’s sides.

In 1944 was introduced the last production version, the B6N2a or Model 12A. It had a revised dorsal armament with its twin flexible Type 92 machine gun replaced with a single 13 mm Type 2 machine gun. No other changes were made.

B5N3

The B6N3 or Model 13, was planned for land-based since in mid-1944 carriers in the IJN were in short supply. Surviving smaller carriers such as the Zuiho, Chitose or Taiyo class lacked catapults for these heavy models. The B6N3 remained at prototype stage, adopting the new Kasei Model 25c engine, more streamlined and powerful. The crew canopy was modified and main landing gear strenghtened while a new retractable tail wheel was added and the tail hook removed. Two B6N3 prototypes were completed in mid-1945, but the scarcity of resources meant in August, the production was not greenlighted. Still at the time, priorority was to dive bombers and fighters, the latter having better survival chances in kamikaze attacks.

As of August 1945, 1,268 B6Ns, mostly B6N2s had been manufactured at its plant of Okawa, Gumma district and in Aichi plant, Handa district at a rate at best of 90 monthly planes.

Design

The new B6N looked more robust, especially compared to the B5N. The fuslage was deeper, the cicpit a bit longer and more spacious, for a crew of three, which could left their seat swap to another post, the rear gunner and bombardier in particular to access both to their map table, secondary dashboard (later radar for those equipped), and radio set. The fuselage measured 10.865 m (35 ft 8 in) overall with a similar wingspan as the B5N at 14.894 m (48 ft 10 in) with an Airfoil which root was classified K121 and tip K119. It was also relatively low, just 3.8 m (12 ft 6 in) in height overall. To compensate for the lack of wingspan the profile of the wings was somewhat modified for a better wing area of 37.2 m2 (400 sq ft).

This was an heavy model, at 3,010 kg (6,636 lb) empty, a Gross weight of 5,200 kg (11,464 lb) when loaded, reaching with its full military payload a total 5,650 kg (12,456 lb) max. at takeoff. And yet still unprotected. The Navy rejected a proposal for self-sealing tanks and armour was limited to a small piece at the top of the pilot’s seat and perhaps an armoured glass plate for the rear gunner.

Powerplant:

The other differences were in the powerplant, a much more massive and heavier Mitsubishi MK4T Kasei 25 (after standardization in late 1943), a 14-cylinder, air-cooled radial piston engine. It delivered 1,380 kW (1,850 hp) for take-off, 1,253 kW (1,680 hp) at 2,100 m (6,900 ft) and 1,148 kW (1,540 hp) at 5,500 m (18,000 ft). The last difference was a generously sized 4-bladed constant-speed propeller, instead of the smaller diameter three bladed one of the B5N, with consequence sin torque that piloted hated at first; The design of tail notably looked peculiar.

Thanks to this engine, the B6N could reach 482 km/h (300 mph, 260 kn) at 4,900 m (16,100 ft) and when cruising, 333 km/h (207 mph, 180 kn) at 5,500 m (18,000 ft) for a range of 1,746 km (1,085 mi, 943 nmi) and Ferry range on 3,045 km (1,892 mi, 1,644 nmi), a service ceiling of 9,040 m (29,660 ft)

Armament:

Guns comprised a single 7.7 mm (0.303 in) Type 92 machine gun in the rear cockpit (later twin mountn and later a 13mm on the B6N2a) and a single 7.7 mm (0.303 in) Type 92 firing through the ventral tunnel. The rear gunner hads to unseat, crouch, and lay into the cradle, then lower it in flight (with wind rushing in) to fire in this position, generally the weakest point of any aircraft at the time when chased.

As for Bombs, the B6N carried a single 800 kg aerial torpedo or 800 kg (1,760 lb) of bombs, the usual panel being a single 800 kg or 500 kg AP bombs or two 250 kg. The B5N was not designed as diver bomber, but tests were made for a semi-dive bomb release with some success. The ratio between the strenght and powerplant were however not excellent.

Detailed specs

| Crew: | 3, Pilot, Bombardier/Navigator, MG-gunner/radio |

| Fuselage Lenght | 10.865 m (35 ft 8 in) |

| Wingspan | 14.894 m (48 ft 10 in) |

| Height | 3.8 m (12 ft 6 in) |

| Wing Area | 37.2 m2 (400 sq ft), airfoil root K121; tip: K119 |

| Empty weight: | 3,010 kg (6,636 lb) |

| Gross weight: | 5,200 kg (11,464 lb), max TO 5,650 kg (12,456 lb) |

| Powerplant: | Mitsubishi MK4T Kasei 25 14-cyl. ARCPE 1,380 kW (1,850 hp) TO, 1,148 kW (1,540 hp) at 5,500 m |

| Propeller: | 4-bladed constant-speed propeller |

| Maximum speed: | 482 km/h (300 mph, 260 kn) at 4,900 m (16,100 ft), cruise 333 kph |

| Service ceiling: | 9,040 m (29,660 ft) |

| Range: | 1,746 km (1,085 mi, 943 nmi), ferry 3,045 km (1,892 mi, 1,644 nmi) |

| Time to altitude: | 5,000 m (16,000 ft) in 10 minutes 24 seconds |

| Power/mass: | 0.2652 kW/kg (0.1613 hp/lb) |

| Wing loading: | 139.8 kg/m2 (28.6 lb/sq ft) |

| Armament | 2×7.7 mm LMGs rear, 1×7.7mm vent. 800 kgs torpedo/bombs |

The B6N in action

Battle of Kwajalein Sept. 1943

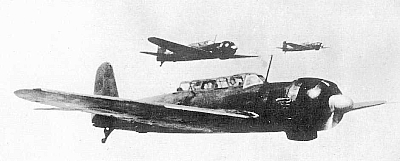

The B6N Tenzan only arrived at front-line units in August 1943 and in small numbers to gradually replace all of the B5N2s (and surviving, worn out B5N1s) “Kate” torpedo bombers present on all carriers of the Third Fleet, by then based at Truk Atoll, Carolines. Combat intensified in the the Solomon Islands and the IJN intel deduced the next US target would be Bougainville. Operation Ro was planned, and this urge a reinforcement of land-based air units at Rabaul. In all, 173 carrier aircraft from the Kido Butao (1st Carrier Division) from Zuikaku, Shokaku and Zuiho flew there, including forty B6Ns from Truk to Rabaul on 28, 29, 30 October and 1 November. They were overall deployed on the Shōkaku, Zuikaku, Taihō, Jun’yō, Hiyō, Ryūhō, Chitose, Chiyoda and Zuihō.

On 5 November, fourteen B6N1s, escorted by four A6M Zero fighters, took off to attack the US amphibious fleet at Bougainville. Four B6N1s were lost without scoring a single hit despite claims to have sunk a medium carrier, two heavy and two cruisers/large destroyers (likely Atlanta class), with another attacks mounted on 8 November and 11 November, both again with heavy losses. When iit was over, 52 out of 173 landed back to Truk on 13 November, notably 6 B6N1 Tenzans of 40. Although losses from low-flighing torpedo bombers were always heavy, this was not a stellar start for the ‘Jill”.

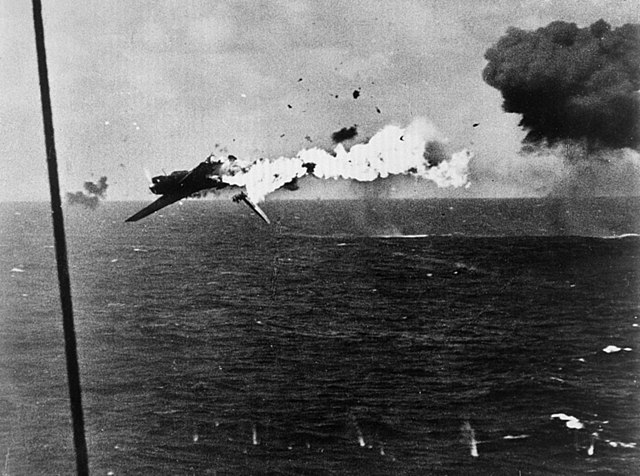

B6N torpedo bomber attacking TG 38.3 during the Formosa Air Battle, October 1944

On 19 June 1944, B6Ns (probably a mix of few remaining N1s and newly arrived N2) made their carrier-borne start at the Battle of the Philippine Sea, under full US air superiority. None could go through the massive US Navy CAPs in order to reach their targets and influct any damage. This was for the new F6F Hellcat fighter pilots, an occasion to add dozens of “Jills” to their tally. Overall, they were deployed by the land-based Himeji, Hyakurihara, Kushira, Sunosaki, Suzuka, Taiwan, Tateyama, Taura, Usa and Yokosuka Kōkūtai as well as the carrier (and later land-based)

131st, 210th, 331st, 501st, 531st, 551st, 553rd, 582nd, 601st, 634th, 652nd, 653rd, 701st, 705th, 752nd, 761st, 762nd, 765th, 901st, 903rd, 931st, 951st, and 1001st Kōkūtai.

When the B6N2a arrived by mid-1944, carriers and experienced pilots were sorely lacking so most B6N2 from then on only operated from land bases, and half were destroyed in US air raids. Still, they were extensively used in the Battle of Okinawa and most started to be used in kamikaze missions with little success as they were the least nimble, most sluggish of those attackers, ealy prey for radar-assisted Bofors and 5-in/38 aboard the fleet. They were assigned to the Kikusui-Tenzan group, Kikusui-Ten’ō group, Kikusui-Raiō group, Mitate group No. 2 and No. 3 as well as the Kiichi group. The remainder were destroyed on their airfields on Kyushu in the summer. Those land-based aerial squadron, often a motly collection of models dating from the Sino-Japanese war for some, included the Attack 251-256th Hikōtai and 262-263nd Hikōtai.

As of today, B6N2 c/n 5350, captured and tested by US forces, remains stored at the National Air and Space Museum’s Paul E. Garber Facility in Suitland (Maryland), currently disassembled. It was saved from the Naval Air Station Joint Reserve Base Willow Grove in Horsham, Pennsylvania and acquired by the National Air and Space Museum in 1981, so in the process of full restoration. This is the only one ever survivor anywhere. This story concludes a relatively unfavourable picture of a model that could have a far more remarkable service record, of Nakajima’s chief engineer had not heavily instisted upon the adoption of an untested engine, overopromising in the process performances that were never there. Delays of nearly 2.5 years were probably the most damming issue, as the “replacement” was never ready, missing the Solomons campaign, and added to this, a heavier weight, somewhat heavier commands made it not a choice for pilots which preferred the old B5N.

When it was available in quantities by late 1944, there were never enough and the USN naval program had in between completely reversed the superiority in the Pacific. Between the lacxk of aircraft carrier to operate it, frequent air raids, stronger opposition and the steel wall offered by the fleet’s AA, the B6N never stood a chance. Equally as kamikaze, as they were probably among the easiest to shoot down by ship’s gunners.

Gallery

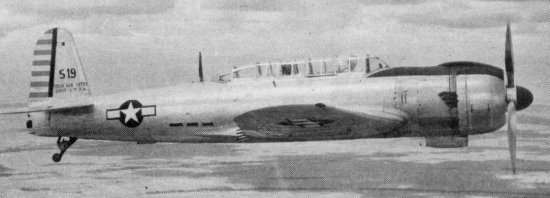

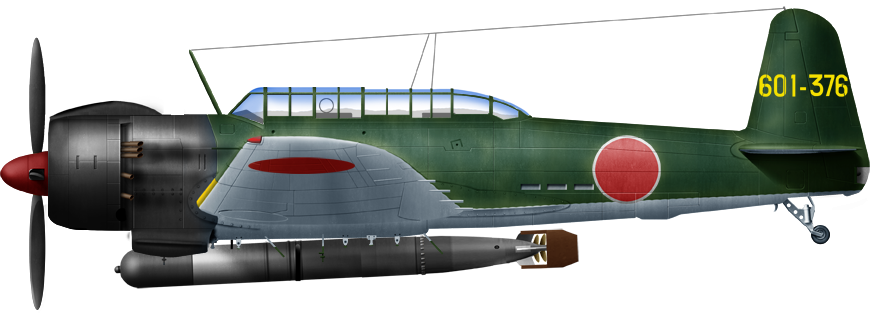

B5N2 for comparison

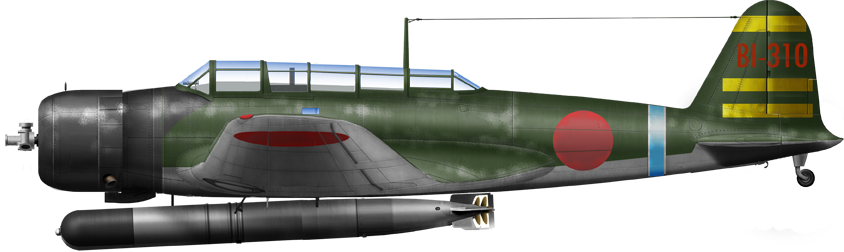

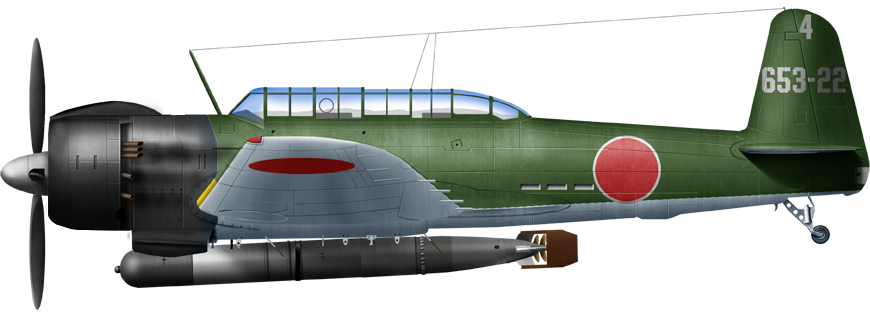

B6N1, Yakurigahara Kokutai 1943

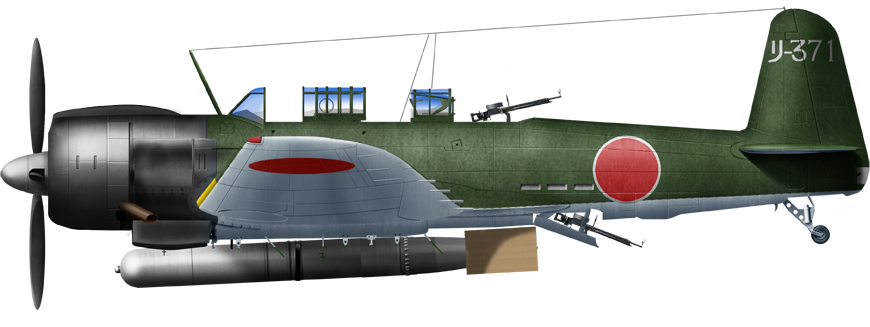

B6N2, IJN Chiyoda, Battle of Leyte, October 1944

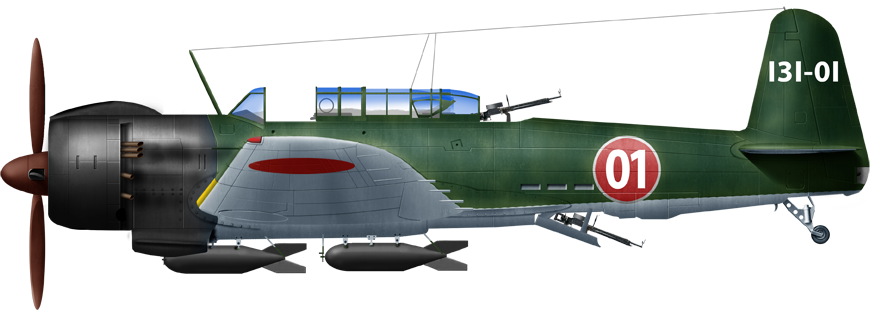

B6N2, 131 Kokutai

B6N2 on board IJN Shinano, 29 November 1944.

Read More/Src

Books

Francillon, René J. (1969), Imperial Japanese Navy Bombers of World War Two, Windsor, Berkshire, UK: Hylton Lacy Publishers Ltd.

Francillon, René J. (1970), Japanese Aircraft of the Pacific War (1st ed.), London: Putnam & Company Ltd.

Francillon, René J. (1979a), Japanese Aircraft of the Pacific War (2nd ed.), London: Putnam & Company Ltd.

Francillon, René J. (1979b), Japanese Carrier Air groups 1941-45, London: Osprey Publishing Ltd.

Gunston, Bill. Military Aviation Library World War II: Japanese & Italian Aircraft. Salamander Books Ltd.

Mondey, David. Concise Guide to Axis Aircraft of World War II. Temple Press, 1984.

Thorpe, Donald W. Japanese Naval Air Force Camouflage and Markings World War II. Fallbrook, California; Aero Publishers Inc., 1977

Tillman, Barrett. Clash of the Carriers. New American Library, 2005.

Wieliczko, Leszek A. (2003), Nakajima B6N “Tenzan”, Famous Airplanes vol. 3, Kagero

The Maru Mechanic No. 30 Nakajima carrier torpedo bomber “Tenzan” B6N, Ushio Shobō (Japan), September 1981

Links

https://web.archive.org/web/20170522233616/https://airandspace.si.edu/collection-objects/nakajima-b6n2-tenzan-heavenly-mountain-jill

https://airandspace.si.edu/collection-objects/wings-pair-nakajima-b6n2-tenzan-heavenly-mountain-jill/nasm_A19810429002

https://web.archive.org/web/20101128003630fw_/http://preservedaxisaircraft.com/Japan/Nakajima/Nakajima.htm

https://web.archive.org/web/20201022011145/https://airandspace.si.edu/collection-objects/wings-pair-nakajima-b6n2-tenzan-heavenly-mountain-jill/nasm_A19810429002

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nakajima_B6N

Model Kits

On scalemates

From Hasegawa 1:48 to Pit-Road 1:700 (for carrier kits), mostly old kits.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign