Introduction

Aviation was brand new in 1914 and already France and Russia aligned no less than 400 planes in operatioal uniits submitted to the Army. The latter, reflecting a constant struggle for independence mirrored the initial reconnaissance duties of the air corps. Aviation had many years to rise, from a bunch of sportsmen and crafty daring-do to something considered with enough seriousness to be tested and eventually adopted by the Army, its main advantage being to replace ballons for observation. From the 1903 Wright brother’s flight at Kitty Hawk, aviation already tested war operations in several occasions before the war, notably in the Balkans and far east. The first even bombing missions started during the Italo-Turkish war of 1912.

Now, if the Army detained an organic aviation corps in all belligerents:

-On the entente side, France, UK, Russia, Japan and in 1915 Italy

-Germany, Austria-Hungary and Turkey for the central Empires

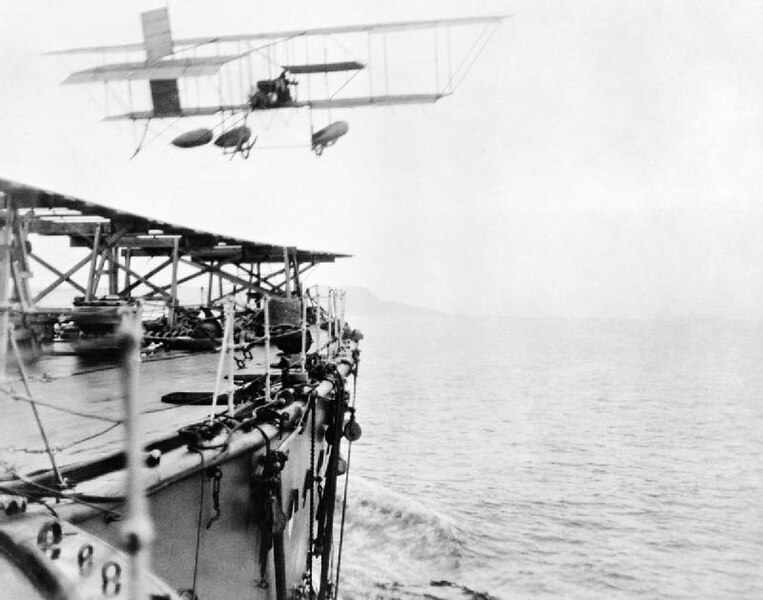

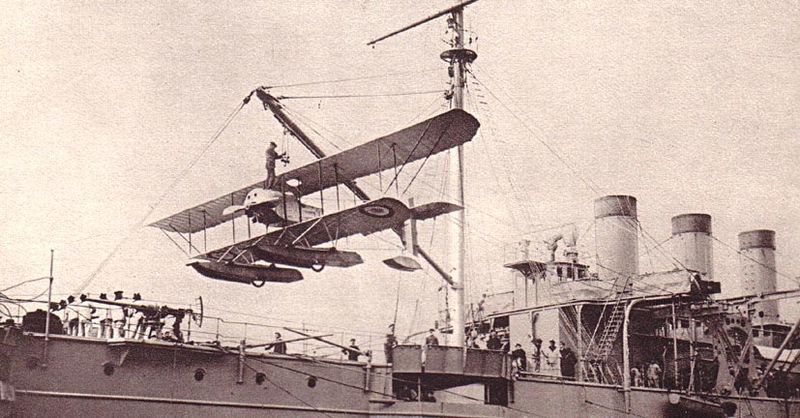

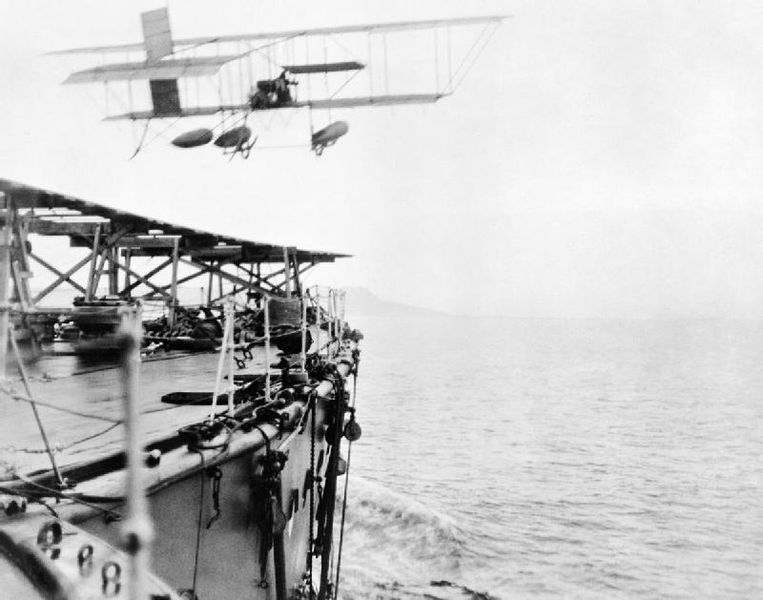

The Navy had none, or a very embryonic one. Since Eugene Ely demonstrated in 1910-11 one can take off or land on a warship, decicated naval aviation corps were few to be developed. In France, there was already such corps in 1912, with even a seaplane carrier, and in Great Britain, the RNAS or Royal Naval Air Service was established on 1 July 1914 (after the Royal Flying Corps, on 13 April 1912). On paper it existed in Russia in 1913 but really was established in 1915 and 1916 for Austria-Hungary.

Commander C. Samson of the RNAS takes off from HMS Hibernia in his modified Shorts S.38 “hydro-aeroplane”, first British pilot to take off from a ship underway at sea.

There was also a small naval air corps belonging to the USN since 1910, but it’s really from 1917 and the US entry into the war that it grew to much larger levels. Meanwhile, Japan operated a single model, the Yokosho Rogou Kougata, playing its part during the siege of Tsingtao. Germany did not lacked manufacturers and had expertise on floatplanes early on, and the Kaiserliche Marine integrated a flying corps, the Marine-Fliegerabteilung, combining airships and fixed wings aircraft.

Naval Air operations during WWI indeed included, to the difference of WW2, more types:

-The long range, large airships, with Zeppeling at the world’s lead

-Land-based Fighters for coastal defence

-Medium land-based bombers for coastal patrol

-Floatplane fighters; adapted from land-based models

-Seaplanes (or flying boats) with amphibious fuselages for patrols and as fighters

Manufacturers of Seaplanes/Floatplanes

Boeing model 2/3/5 (1916)

Aeromarine 39 (1917)

Curtiss H (1917)

Curtiss F5L (1918)

Curtiss VE-7 (1918)

Curtiss NC (1918)

Curtiss NC4 (1918)

Fairey Campania (1915)

Short 184 (1915)

Felixtowe F2A (1917)

Albatros W.4 (1916)

Albatros W.8 (1918)

Friedrichshafen Models

Gotha WD.1-27 (1918)

Hansa-Brandenburg series

L.F.G V.19 Stralsund (1918)

L.F.G W (1916)

L.F.G WD (1917)

Lübeck-Travemünde (1914)

Oertz W series (1914)

Rumpler 4B (1914)

Sablatnig SF (1916)

Zeppelin-Lindau Rs series

Kaiserlichesmarine Zeppelins

Borel Type Bo.11 (1911)

Nieuport VI.H (1912)

Nieuport X.H (1913)

Donnet-Leveque (1913)

FBA-Leveque (1913)

FBA (1913)

Donnet-Denhaut (1915)

Borel-Odier Type Bo-T(1916)

Levy G.L.40 (1917)

Blériot-SPAD S.XIV (1917)

Hanriot HD.2 (1918)

Zodiac Airships

Macchi M3 (1916)

Macchi M5 (1918)

SIAI S.12 (1918)

Grigorovich M-5 (1915)

Grigorovich M-9 (1916)

Grigorovich M-11 (1916)

Grigorovich M-15 (1916)

Grigorovich M-16 (1916)

Grigorovich M-16 (1916)

Lohner E (1914)

Lohner L (1915)

Oeffag G (1916)

Since it’s relatively easy to exchange a wheeltrain for floats, most land-based models on paper (and in practice) equipped naval aviation corps, coming from the same manufacturers as for the regular air corps. But building seaplanes was a dedicated skill and some manufacturers specialized in it. Those below starred are not “pure players”. We can cite here:

- Lohner (Austria Hungary)

- Oeffag (Austria Hungary)

- Grigorovitch (Russia)

- Fairey (UK)*

- Short (UK)*

- Felixtowe (UK)

- Friedrichshafen (Germany)

- Levy (France)

- Donnet-Leveque (France)

- FBA (France)

- Macchi (Italy)

- SIAI (Italy)

- Boeing*

- Curtiss*

- Aeromarine**

** The latter exclusively worked for the Navy, with Curtiss coming close second although it became the Army dear in the interwar.

Tactics of seaplanes/floatplanes in WWI

It was mostly the result of the geopolitical particulars of the great war. The western front froze itself in September 1914, resulting in a gruelling static trench warfare. At sea, the only sizeable central empires fleet was German. It was still away, but almost on par with the Royal Navy, ahead of the French and US or Japanese fleets. In 1915 with the added weight of the Regia Marina, the smaller Austro-Hungarian Navy was “trapped” in Pola, Adriatic, while the obsolete Ottoman Navy, althought reinforced by the Breslau/Goeben, was challenged by the Russian black sea fleet.

Once Von Spee’s far eastern squadron, chased from its Asian/Pacific bases by the combined might of the Japanese and British Navies, was dealt for in the Falklands, and its scattered remains found and sunk in turn (Emden, Königsberg and others), the Kaiserliches Marine was reduced to its main combat fleet, the Hochseeflotte. After Jutland in June 1916, it was almost inactive until the end of the war.

Instead, Germany focused its attention of the new promising submersible. And thus, it’s really the 1917-18 phase of the battle of the Atlantic, with more troopships and vital cargoes crossing to the old world, that submarine warfare, counting more U-Boats than ever at sea, became the greatest naval threat. It was to motivate the most radical increase in the entente naval corps. It was soon realized that:

1-Planes were quite able to see submerged submersibles, or detect them surfaced by clear weather at much larger distances than surface ships, still devoid of sonar and radars at the time.

2-Floatplanes could “land” anywhere contrary to land-based ones and thus were more qualified for the role

3-Planes could radio their findings but also attack by themselves with cannons and bombs in some cases.

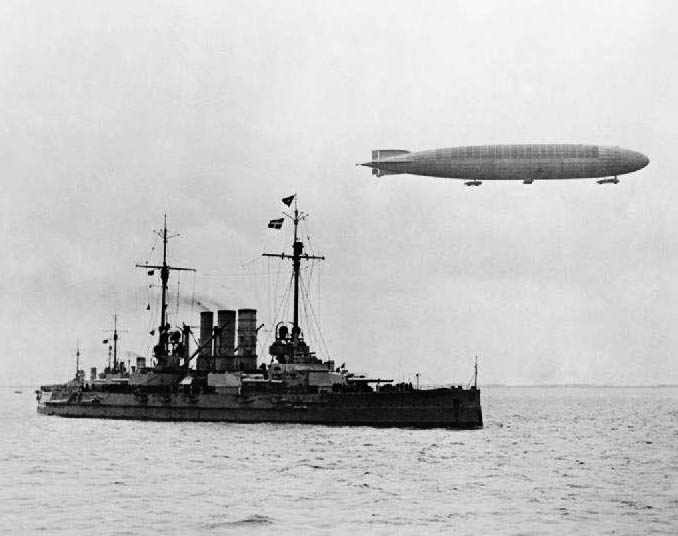

And thus, from coastal defence and patrol, directed as enemy vessels, tactics changed on the entente side to ASW patrol, mostly in the Atlantic, but also the Mediterranean, with the Black sea good third. If long range multi-engine heavy bombers of 1917-18 could have been used, they were reserved for an early form of strategic bombing for the Army. One considerable asset however for the central Empires were their airships, 118 built by Zeppelin before and during the war.

The question of strategic bombing

With their long range, they could constantly watch over the north sea when working for the Kaiserliches Marine, the others being employed for “strategic” solo bombing missions notably over London and Paris. The Royal Navy even installed long range guns to deal with them, dedicated fighter squadrons with incendiary bullets and rockets also, and there were indeed a few duels between cruisers and Zeppelins. On paper an airship was much faster (85 kph at best compared to 28 knots/51 kph for a light cruiser) and could carry four tonnes of bombs. But the admiralty never tried to bomb a ship, a shame because at the time, deck protection was minimal, if existing at all. It could have been possible for a fleet of Zeppelin to bomb the Grand Fleet in Scapa Flow.

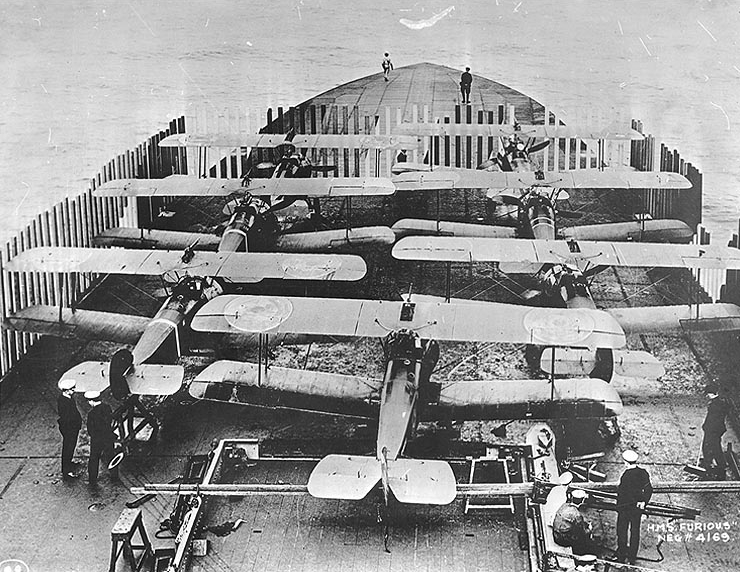

In 1917, the “blitz” started, with the Luftstreitkräfte launching dozens of Gotha bombers in formation over London. Ouitside the RFC, already engaged in France, local units of the RNAS took part in the interception. In fact Germany had a taste of its own medecine when not only the RFC started its own strategic bombing campaign in 1918 in retaliation, but also the Royal Navy launched a raid on the Tondern Zeppelin facility in 1918, trying to destroy Zeppelin sheds, while using for the first time the aircraft carrier HMS Furious in a dangerous sortie close to the German shore. Before that, the Sopwith aboard participated in daily patrols to find and destroy Zeppelins.

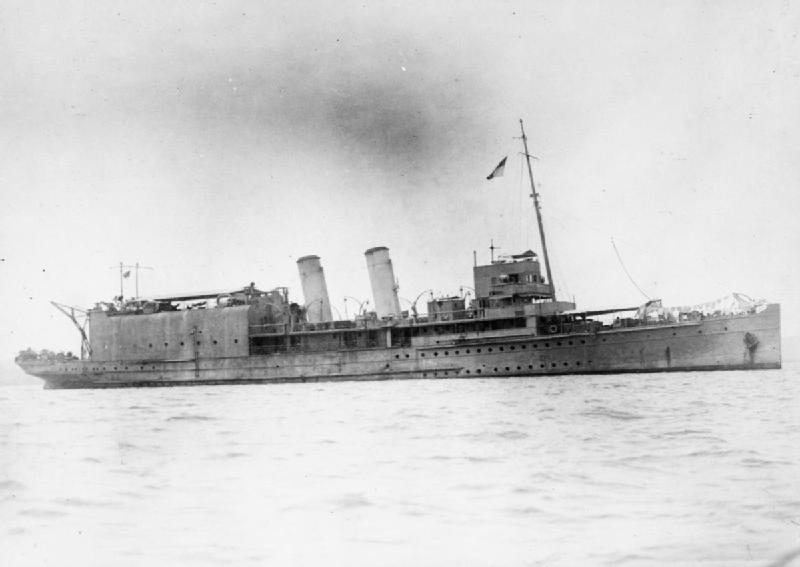

The development of seaplane carriers

(to come)

British seaplane carriers

Tactics & Strategy of Aviation

The very first tactical approach of planes was only related to their combined use with artillery. However as the war progressed, they were soon pushed into new roles, which created branches -and tactics- of their own. The Fighters are a good example of this. They emerged of necessity, when aviation met intelligence gathering in an industrial scale.

The very first tactical approach of planes was only related to their combined use with artillery. However as the war progressed, they were soon pushed into new roles, which created branches -and tactics- of their own. The Fighters are a good example of this. They emerged of necessity, when aviation met intelligence gathering in an industrial scale.

On the ground, spies were shot, but the first aviators, even from opposite sides, gently waved their hands in salute when meeting in the air. Of course this “chivalry” image persisted in culture, but the grim reality soon take over when when a pilot first shot another with a pistol.

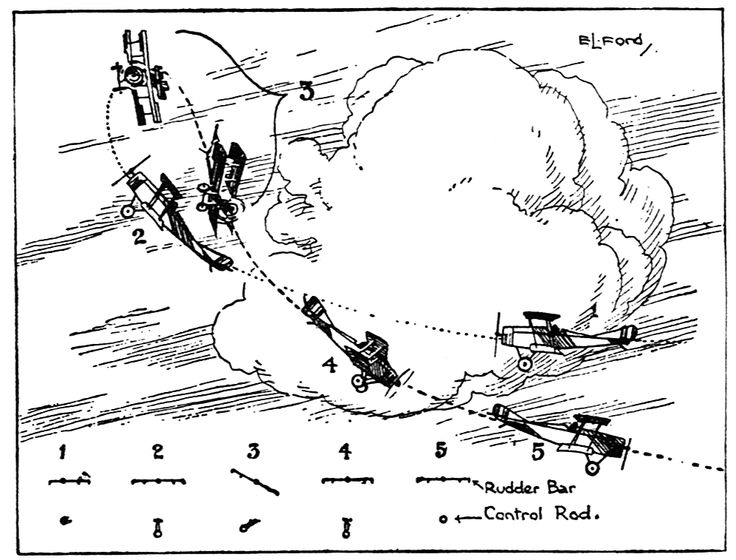

They were attempts, with grenades, lead balls, hooks, cavalry rifles, until the most deadly weapon of the war made its way in turn, amidst the canvas and ropes of the first improvized fighters. The first MG-armed serie fighters were the Fokker Eindecker E-I which advantageously replaced the prolific bird-like Erich Taube, way too frail for a machine-gun. From then on, the plane itself, thanks to the interrupter gear, could be aimed by the pilot on its target. And the first fighter tactics were born.

Max Immelman (which gave its name to a distinctive loop) was among the first to devise air-to-air combat tactics. The Germans pilots of the Luftstreitkrafte in general were the first to codify these tactics, especially Oswald Boelcke, his own great rival. The latter indeed would be considered as the Father of Air Fighting Tactic, and wrote the famous “Boelcke’s Dicta”, still bedside book for pilots at the eve of the Spanish Civil War (More on this below, see “aces”).

Max Immelman (which gave its name to a distinctive loop) was among the first to devise air-to-air combat tactics. The Germans pilots of the Luftstreitkrafte in general were the first to codify these tactics, especially Oswald Boelcke, his own great rival. The latter indeed would be considered as the Father of Air Fighting Tactic, and wrote the famous “Boelcke’s Dicta”, still bedside book for pilots at the eve of the Spanish Civil War (More on this below, see “aces”).

With his Jasta 2 in 1916, Boelke had his men practising strict formations, repeating tactical drills. One of his most avid students were Manfred von Richthofen and Erwin Böhme. At the time of the second “Fokker scourge” in April 1917, German pilots were the best in the world, making for inferior numbers.

Technology

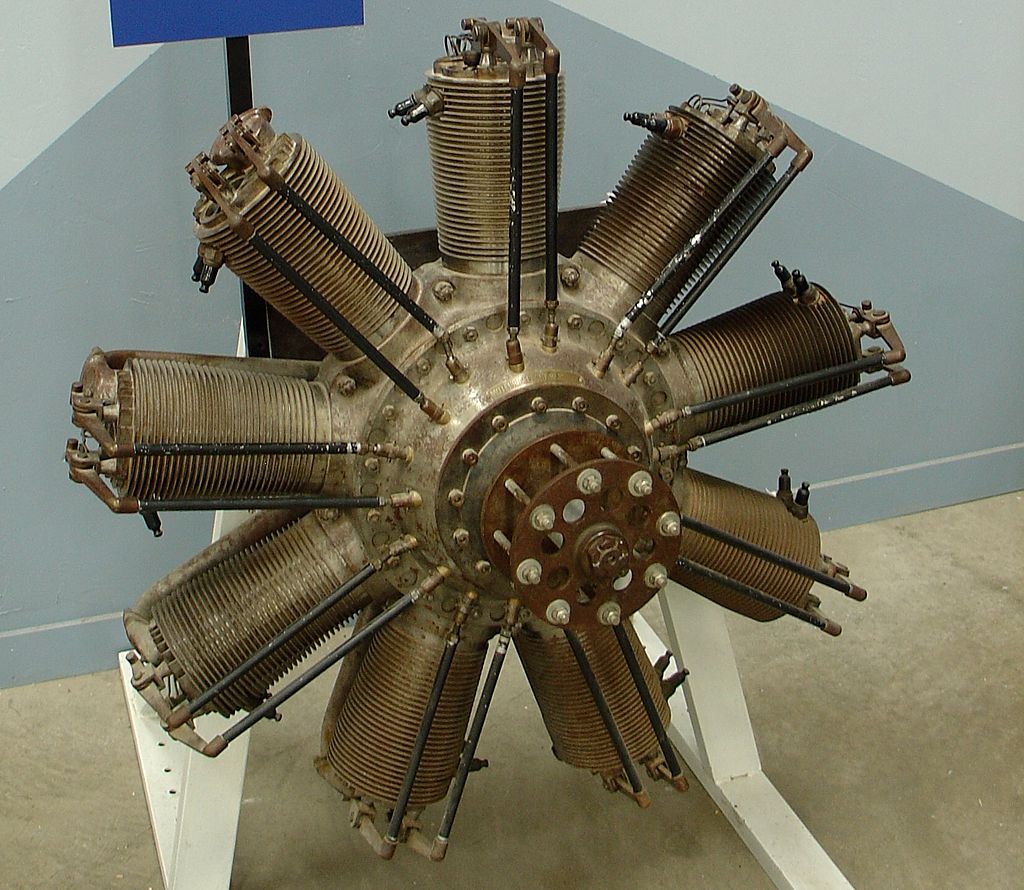

From the Wright Brothers’s “Flyer”, a frail contraption of twisted wood, ropes and canvas, using a pusher configuration and canard, planed went to the late WW1 models, either superfast, well-profiled and powerful fighter capable of 250 kph, sturdy all-duty two-seaters, or heavy four engine bombers. The hart of the plane was, as today, its engine. In 1903 Taylor built a light four-cylinder for the Wright’s brother plane. In 1906 Levavasseur built a streamlined water-cooled V8 engine. But most importantly in 1908 Seguin’s Gnome Omega, became the world’s first rotary engine, mass-built until the end of the war and used by all. This was the ancestor of fixed star-shaped engines (or radial). There would be a long and protracted “battle” between the supporters of the air-cooled radial and watercooled inline engines. Both had their advantages and drawbacks, and both were maintained in production until the coming of the jet. In this era of daring pioneers however, even more radical solutions were studied. The first ramjet engine was patented as early as 1908, first Coandă ducted fan aircraft in 1910, first Rateau turbocharger in 1914 (perfected by Moss in 1918 and later built in serie by Armstrong Siddeley as the Jaguar IV).

Mercedes D.III engine

Rotary engines has been the mainstay of propulsion in WW1, alongside inline engines. By quantity the first easily outmatched the second. They were more compact, easy to manufacture and maintain. But they also provoked a high drag. The inline engine however was compact in another way: The inline cylinders made for a much more reduced cut, and helped to create streamline fuselages with more reduced drag, and ultimately better speeds. Much costlier and requiring more maintenance and technical skills they were mostly used by the Germans. One important characteristic was inline engines were immobile, while the rotary ones, as their name suggest, turned at the very same rate as the propeller. This cause excessive fatigue and some gyration problems that made some flight characteristics tricky for untrained pilots (which was often the case). But in the end, and giving the life expectancy of planes and pilots on the Western front, the main concern became production.

The saga of WW1 seaplane & floatplanes

During World War I, seaplanes and floatplanes played crucial roles in naval operations, reconnaissance missions, and anti-submarine warfare. The United States, like other major powers of the time, developed and utilized various seaplane and floatplane models during the conflict. Here are a few notable examples:

Curtiss H-4 (America): Designed by Glenn Curtiss, the H-4 was one of the first successful seaplanes developed by the United States. It was a large biplane intended for long-range patrol and reconnaissance missions. Known as the “America,” it gained fame for its attempt to cross the Atlantic Ocean in 1914.

Curtiss NC (Nancy): Following the success of the H-4, the Curtiss NC was developed as a series of flying boats designed for long-range flights. The most famous of these was the NC-4, which completed the first transatlantic flight in 1919 as part of the NC-4 convoy.

Felixstowe F5L: While not of American origin, the Felixstowe F5L became an important aircraft for the United States during WWI. This large flying boat was used for anti-submarine patrols and convoy escort duties. The U.S. Navy operated several of these aircraft, employing them effectively in maritime operations.

Curtiss Model F: Another significant design by Curtiss, the Model F was a series of flying boats used by the United States Navy during World War I. These were versatile aircraft utilized for reconnaissance, patrol, and even bombing missions.

Huffman HS-1L: Developed by the Huffman Manufacturing Company, the HS-1L was a biplane flying boat used by the U.S. Navy for coastal patrol and reconnaissance during World War I. It was notable for its reliability and ruggedness in maritime environments.

L-6: The L-6 was a series of small seaplanes developed by the United States during WWI. These aircraft were primarily used for training purposes, but some were also employed for coastal patrol duties.

These aircraft played vital roles in maritime operations, reconnaissance, and defense against submarine threats, contributing significantly to the war effort.

- Boeing model 2/3/5 (1916)

- Aeromarine 39 (1917)

- Curtiss H (1917)

- Curtiss F5L (1918)

- Curtiss VE-7 (1918)

- Curtiss NC (1918)

- Curtiss NC4 (1918)

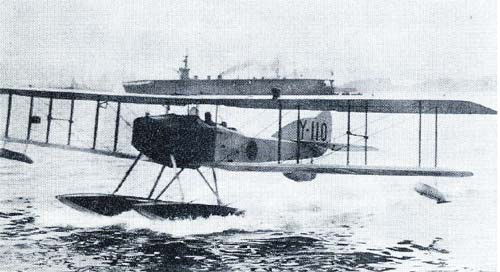

Japanese WW1 seaplanes & floatplanes

Japanese WW1 seaplanes & floatplanes

The Yokosho Rogou Kougata was the first Japanese designed military floatplane going into production

During World War I, Japan primarily relied on seaplanes and floatplanes for reconnaissance, coastal defense, and anti-submarine warfare. While Japan’s involvement in WWI was limited compared to other major powers, it did deploy several aircraft for maritime operations. Here are some notable examples of Japanese seaplanes and floatplanes from that era:

Glen Martin MS: The Glen Martin MS was one of the earliest seaplanes used by Japan during World War I. It was a flying boat design produced by the Glenn L. Martin Company in the United States. Japan acquired several Martin MS aircraft and used them for reconnaissance and coastal patrol duties.

Sopwith Baby: The Sopwith Baby was a British single-seat floatplane used by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service (IJNAS) during World War I. It was employed primarily for reconnaissance missions and coastal patrols. The Japanese Navy operated a number of these aircraft, which were deployed from seaplane carriers and shore bases.

Felixstowe F.2A: The Felixstowe F.2A was a British flying boat design used by Japan during World War I. It was employed by the IJNAS for maritime reconnaissance and anti-submarine warfare missions. The Japanese Navy operated several Felixstowe F.2A aircraft, which were effective in patrolling coastal waters and protecting shipping lanes.

Short Type 184: The Short Type 184 was a British floatplane used by Japan during World War I. It was operated by the IJNAS and employed for reconnaissance, anti-submarine patrols, and bombing missions. The Japanese Navy acquired a number of Short Type 184 aircraft and deployed them in various theaters of operation.

Watanabe E9W: The Watanabe E9W was a Japanese-designed reconnaissance floatplane used by Japan during the interwar period, but some sources suggest it may have seen limited service toward the end of World War I. It was a biplane aircraft used for reconnaissance and artillery spotting duties.

These are some of the seaplanes and floatplanes that Japan used during World War I. While Japan’s involvement in the conflict was relatively limited, these aircraft played important roles in supporting naval operations and protecting Japanese interests in the Pacific region.

- IJN Farman 1914

- Yokosho Rogou Kougata (1917)

- Yokosuka Igo-Ko (1920)

Royal Naval Air Service

Royal Naval Air Service

British WW1 seaplanes & floatplanes

Sopwith Cuckoo, the first torpedo carrying aircraft

During World War I, the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS), the aerial arm of the Royal Navy, employed a variety of seaplanes and floatplanes for reconnaissance, anti-submarine warfare, convoy protection, and other naval operations. Here are some notable examples:

Short 184: The Short 184 was one of the most successful seaplanes used by the RNAS during World War I. It was a two-seat reconnaissance and torpedo-bomber floatplane. It saw extensive service in patrolling coastal waters, hunting submarines, and attacking enemy surface vessels.

Short Type 320: The Short Type 320, also known as the “Short Folder,” was a reconnaissance seaplane used by the RNAS. It featured folding wings, which made it easier to store and transport aboard ships. The Type 320 was deployed for reconnaissance missions and coastal patrols.

Felixstowe F.2: The Felixstowe F.2 series of flying boats were among the largest and most capable aircraft used by the RNAS during WWI. Developed from the Curtiss H-4 flying boat, these aircraft were employed for long-range maritime reconnaissance, convoy escort, and anti-submarine patrols.

Curtiss H-4: While not of British origin, the Curtiss H-4 flying boat was used by the RNAS during World War I. Known as the “America” in its transatlantic flight attempt, the H-4 was also utilized for reconnaissance and anti-submarine operations in coastal waters.

Supermarine Baby: The Supermarine Baby was a single-seat floatplane used for reconnaissance and anti-submarine warfare by the RNAS. It was a small, agile aircraft that operated from seaplane carriers and shore bases, conducting patrols and escort missions.

Sopwith Baby: The Sopwith Baby was a British single-seat floatplane used for reconnaissance and anti-submarine patrols by the RNAS. It was deployed from seaplane carriers and shore bases, playing a significant role in coastal defense and convoy protection.

Felixstowe F5: Another variant of the Felixstowe series, the F5 was a larger flying boat employed by the RNAS for maritime reconnaissance and anti-submarine warfare. It featured an improved hull design and was capable of extended patrols over the open ocean.

They played vital roles in supporting naval operations and protecting Britain’s maritime interests during the conflict.

- Short 184 (1915)

- Fairey Campania (1917)

- Felixtowe F2 (1916)

- Felixtowe F3 (1917)

- Felixtowe F5 (1918)

- Sopwith Baby (1917)

- Fairey Hamble Baby (1917)

- Fairey III (1918)

- Short S38 (1912)

- Short Admiralty Type 166 (1914)

- Short Admiralty Type 184 (1915)

- Blackburn Kangaroo

- Sopwith 1-1/2 Strutter

- Sopwith Pup

- Sopwith Cuckoo 1918

- Royal Aircraft Factory Airships

Marineflieger

Marineflieger

Kaiserliches Marine flotplanes and seaplanes

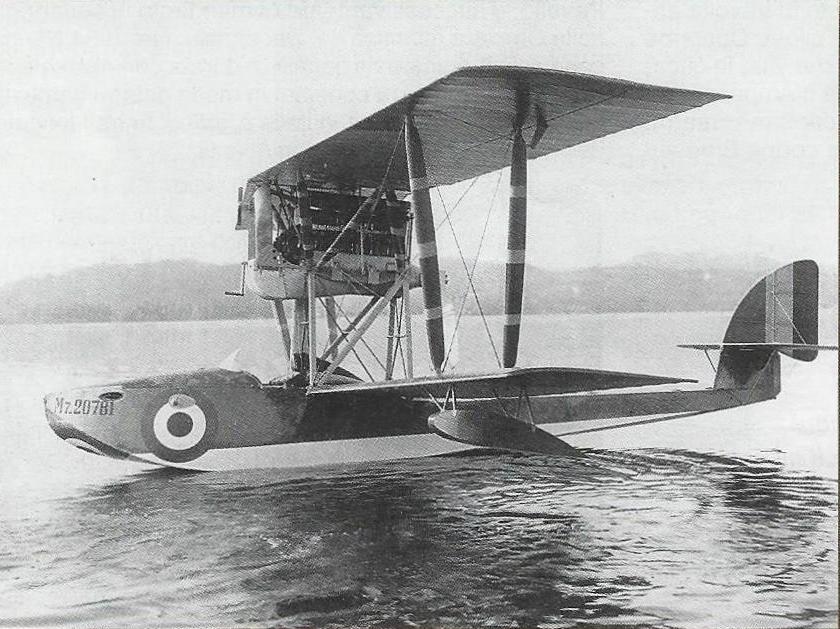

Hansa-Brandenburg W.11

During World War I, the Kaiserliche Marine (Imperial German Navy) operated a variety of seaplanes and floatplanes for reconnaissance, anti-submarine warfare, coastal patrol, and other naval tasks. Here are some notable examples:

Rumpler 6B1: The Rumpler 6B1 was a German reconnaissance seaplane used by the Kaiserliche Marine during World War I. It was a two-seat biplane with a float undercarriage, employed for coastal reconnaissance and observation missions.

Friedrichshafen FF.33: The Friedrichshafen FF.33 was a German reconnaissance floatplane used by the Kaiserliche Marine and the Luftstreitkräfte (German Air Force) during World War I. It was a two-seat biplane employed for reconnaissance, artillery spotting, and coastal patrol duties.

Gotha WD.14: The Gotha WD.14 was a German reconnaissance seaplane used by the Kaiserliche Marine during World War I. It was a large, twin-engine biplane employed for long-range reconnaissance and maritime patrol missions.

AEG N.I: The AEG N.I was a German floatplane used by the Kaiserliche Marine during World War I. It was a two-seat biplane primarily employed for coastal reconnaissance and anti-submarine patrols.

Hansa-Brandenburg W.29: The Hansa-Brandenburg W.29 was a German floatplane used by the Kaiserliche Marine during World War I. It was a single-seat biplane employed for reconnaissance, coastal patrol, and anti-submarine warfare.

Gotha WD.11: The Gotha WD.11 was a German reconnaissance seaplane used by the Kaiserliche Marine during World War I. It was a large, twin-engine biplane employed for long-range maritime reconnaissance and patrol missions.

Rumpler 6B: The Rumpler 6B was a German reconnaissance floatplane used by the Kaiserliche Marine during World War I. It was a single-engine biplane employed for coastal reconnaissance and observation duties.

These are just a few examples of the seaplanes and floatplanes used by the Kaiserliche Marine during World War I. They played important roles in supporting naval operations, reconnaissance, and maritime patrol in the North Sea, Baltic Sea, and other theaters of the conflict.

- Albatros W.4 (1916)

- Albatros W.8 (1918)

- Friedrichshafen Models

- Gotha WD.1-27 (1918)

- Hansa-Brandenburg series

- L.F.G V.19 Stralsund (1918)

- L.F.G W (1916)

- L.F.G WD (1917)

- Lübeck-Travemünde (1914)

- Oertz W series (1914)

- Rumpler 4B (1914)

- Sablatnig SF (1916)

- Zeppelin-Lindau Rs series

- Kaiserlichesmarine Zeppelins

Aéronavale

Aéronavale

French WW1 seaplanes & floatplanes

During World War I, France employed a variety of seaplanes and floatplanes for reconnaissance, maritime patrol, anti-submarine warfare, and other naval tasks. Here are some notable examples of French seaplanes and floatplanes from that era:

FBA Type H: The FBA Type H was one of the most widely used French seaplanes during World War I. It was a versatile flying boat employed for reconnaissance, patrol, and anti-submarine warfare. The Type H featured a single-engine biplane configuration and was known for its reliability and ruggedness.

Voisin Type 3: The Voisin Type 3 was a reconnaissance floatplane used by France during World War I. It was a biplane aircraft employed for coastal patrol and reconnaissance duties.

Salmson 2: The Salmson 2 was a reconnaissance biplane aircraft used by France during World War I. While primarily used as a land-based aircraft, it was also adapted for floatplane operations, serving in reconnaissance and patrol roles over water.

Donnet-Denhaut DD.8: The Donnet-Denhaut DD.8 was a flying boat used by France during World War I. It was employed for reconnaissance, patrol, and anti-submarine warfare duties. The DD.8 featured a single-engine biplane configuration and was known for its stability and endurance.

Tellier T.3: The Tellier T.3 was a reconnaissance floatplane used by France during World War I. It was a biplane aircraft employed for coastal patrol and reconnaissance missions.

Levasseur PL.4: The Levasseur PL.4 was a reconnaissance floatplane used by France during World War I. It was a biplane aircraft employed for coastal patrol and reconnaissance duties.

Nieuport 10: While primarily a land-based aircraft, the Nieuport 10 was also adapted for floatplane operations by the French during World War I. It was a reconnaissance and light bomber aircraft used for coastal patrol and reconnaissance missions.

These are just a few examples of the seaplanes and floatplanes used by France during World War I. They played important roles in supporting naval operations, reconnaissance, and coastal defense in the Mediterranean, Atlantic, and other theaters of the conflict.

- Borel Type Bo.11 (1911)

- Nieuport VI.H (1912)

- Nieuport X.H (1913)

- Donnet-Leveque (1913)

- FBA-Leveque (1913)

- FBA (1913)

- Donnet-Denhaut (1915)

- Borel-Odier Type Bo-T(1916)

- Levy G.L.40 (1917)

- Blériot-SPAD S.XIV (1917)

- Hanriot HD.2 (1918)

- Zodiac Airships

Aviazione Navale

Aviazione Navale

Italian WW1 seaplanes & floatplanes

During World War I, Italy utilized a variety of seaplanes and floatplanes for reconnaissance, coastal patrol, anti-submarine warfare, and other naval tasks. Here are some notable examples of Italian seaplanes and floatplanes from that era:

Macchi M.3: The Macchi M.3 was one of the most successful Italian seaplanes of World War I. It was a reconnaissance and patrol floatplane widely used by the Italian Navy. The M.3 featured a single-engine biplane configuration and was known for its agility and reliability.

Macchi M.5: The Macchi M.5 was a development of the M.3 and was specifically designed for air combat. It featured a more powerful engine and improved aerodynamics, making it a formidable fighter floatplane. The M.5 was used for both reconnaissance and air-to-air combat missions.

Savoia-Pomilio SP.1: The Savoia-Pomilio SP.1 was a reconnaissance floatplane used by the Italian Navy during World War I. It was a large, twin-engine biplane capable of long-range patrols and reconnaissance missions over the Adriatic Sea.

SIAI S.8: The SIAI S.8 was a reconnaissance and bomber floatplane used by Italy during World War I. It was a single-engine biplane employed for maritime patrol, coastal reconnaissance, and bombing missions.

Ansaldo A.300: The Ansaldo A.300 was a reconnaissance floatplane used by Italy during World War I. It was a biplane aircraft employed for coastal patrol and reconnaissance duties.

Ansaldo A.120: The Ansaldo A.120 was a reconnaissance floatplane used by Italy during World War I. It was a single-engine biplane employed for coastal patrol and reconnaissance missions.

FBA Type H: Although of French origin, the FBA Type H flying boat was used by Italy during World War I. It was a versatile aircraft employed for reconnaissance, patrol, and anti-submarine warfare.

These are just a few examples of the seaplanes and floatplanes used by Italy during World War I. They played important roles in supporting naval operations, reconnaissance, and coastal defense in the Mediterranean and Adriatic theaters of the conflict.

- Ansaldo SVA Idro (1916)

- Ansaldo Baby Idro (1915)

- Macchi M3 (1916)

- Macchi M5 (1918)

- SIAI S.12 (1918)

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign