WW1 US Naval Aviation

WW1 US Naval Aviation

Introduction

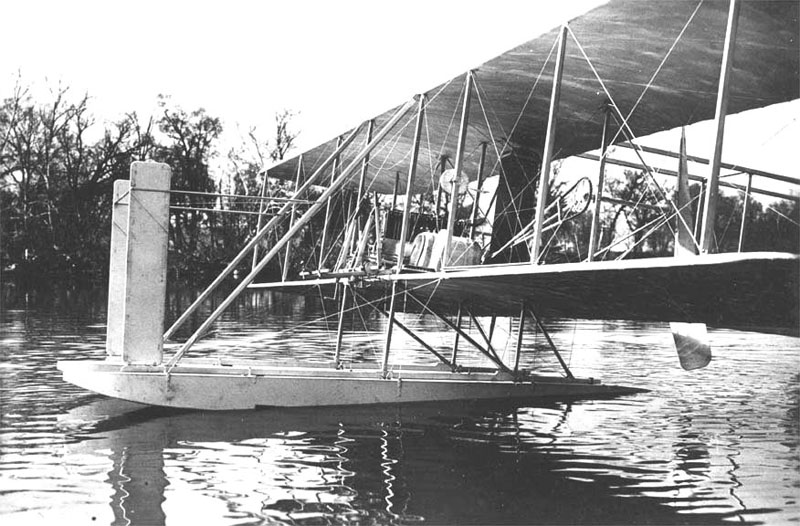

It is clear that it will remain quite difficult to separate aviation from naval aviation. The latter evolved very early on from standard models and impose itself as an evidence. With the abundance of lakes, seas and oceans around the globe, there was no shortage of free, unlimited surfaces to take off from or land on. Thus, despite the drag cause by the floats, floatplanes still made their mark and models were proposed by the Wright Brothers or Benoist as early as 1910.

In fact, U.S. Naval Aviation was born more preciselely on 8 May 1911: This came from a purchase request made by Captain Washington Chambers to test the concept for the Navy. It was a new type called the hydroaeroplane back in France, better known as a “floatplane” or “seaplane/flying boat” depending of is the fuselage was the main float or not. The latter were purely dedicated models whereas the first were adapted land undercarriage models.

In the years leading up to the great wars, pioneer aviators tested their capabilities and imagined their warfare use, and as true believed, working hard into a rather conserrvative hierachy to integrate Naval Aviation in the greater US Navy general organization and missions. But it’s really Eugene Ely’s exploits in 1911 that “sealed the deal” in a very practical -and dangerous way- for the navy. Taking off from Lakes or protected coastal areas was not the most seducive proposition for the fleet, but integrating planes in fleet operation was.

And that’s precisely what Ely did on January 18, 1911. It was already five years after the launc of HMS Dreadnought, and the first US dreadnoughts, while a full serie of new ones were constructed and planned for the upcoming years. So much attention was given to these new prince sof the seas, that cruiser development was halted entirely and the role of destroyers completely re-thought. In 1911, aviation was already no longer a sport, but started to be studied as an industry for multiple application. Last but least the military was interested, for it’s potential for reconnaissance. The Navy was equally interested by the same potential, given the possibilities of altitude long range spotting no ship could ever have.

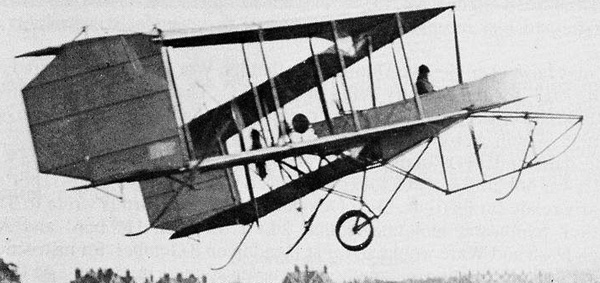

The engine power at the time was so weak, that it was not yet question of carrying any military payload. The power available was used to lift a pilot, perhaps an observer, and that was it. less dependent from the winds than a balloon, the heavier than air formula was more promising. Since 1909 already the Wright Military Flyer was tested by the U.S. Army, precisely to replace the balloon corps. Three years afterwards, in 1911, the first U.S Navy officers were trained to fly Glenn Curtiss and Wrights purchased by the Navy. A first site was established for naval aircraft operations at Annapolis but also a North Island, San Diego which had the right protection from the elements and clement weather.

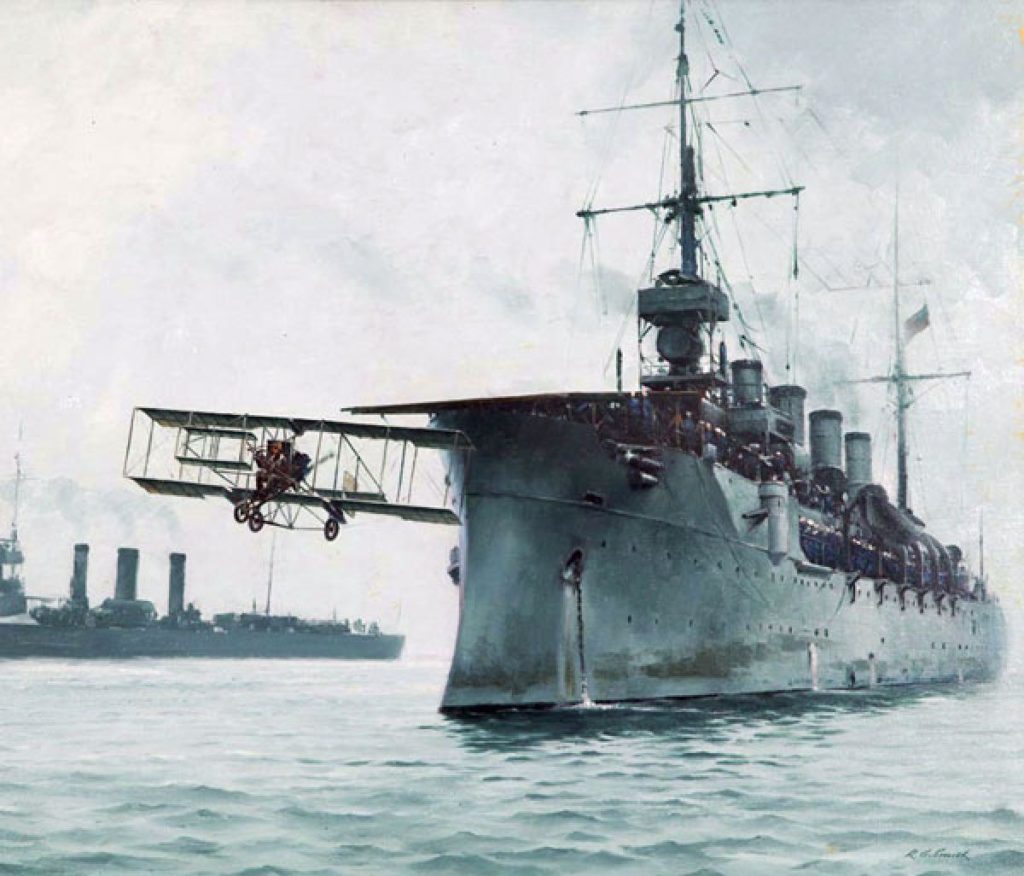

However by far, the most telling and most dramatic demonstration was done on January 18, 1911 by Eugene Burton Ely, making the first successful landing and take-off from a warship: The cruiser USS Birmingham. The man obtained an engineering degree in 1904 from the Iowa State University and after a start as an auto salesman, mechanic, and racing driver, her took his first flight lessons in 1910, soon showing natural skills.

He even became a household name associated to the touring Curtiss Exhibition Team and at the end of the year, the Navy pressed Washington I. Chambers to startt his study or practical application of aviation for naval warfare. The latter quickly saw the need to operate at sea and started to enquire if landings and take-offs from ships could be done. At the time her attended a meeting held at Belmont Park, NY by October 1910, met Glenn Curtiss but also Eugene Ely. He proposed to provide him a ship and modifications to test a first attempt to land aboard. Ely found it thrilling and acquiesed.

Soon, the Navy leased the cruiser USS Birmingham of the Chester class, and a 80 feet long wooden platform was constructed at the prow, in slope for acceleration, stacked between the bridge and tip of the bow. The ship was tall and thus, even if the plane had a downdraft, the fall itself was judged enough to regain the required velocity and thus, lift. The first tests were performed in November 1910.

Indeed, on November 14, USS Birmingham departed Norfolk and Ely prepared his modified Curtiss Pusher, based on the D-III Headless Pusher, fitted with underwings floats. Her eventually made the first take-off, but barely as shown in the photo. Although he pushed the engine hard, no attempts were made to block the wheels for a quick release. He just accelerated gradually and naturall started to fall after rolleing off the edge. But as predicted due to the tall prow, it soon settled, anf after skipping off the water and damaging its propeller managed to stay airborne. The pushed “landed” 2 miles and a half away on the nearest land, Willoughby Spit.

Next he prepared for a much riskier test: Landing on a ship. The Navy considered again USS Birmingham but due to the longer platform required, she had no suitable surface long enough, and a larger ship was searched for. Ely, again, made ready for this new try and went with idead about how to stop his plane on a short surface.

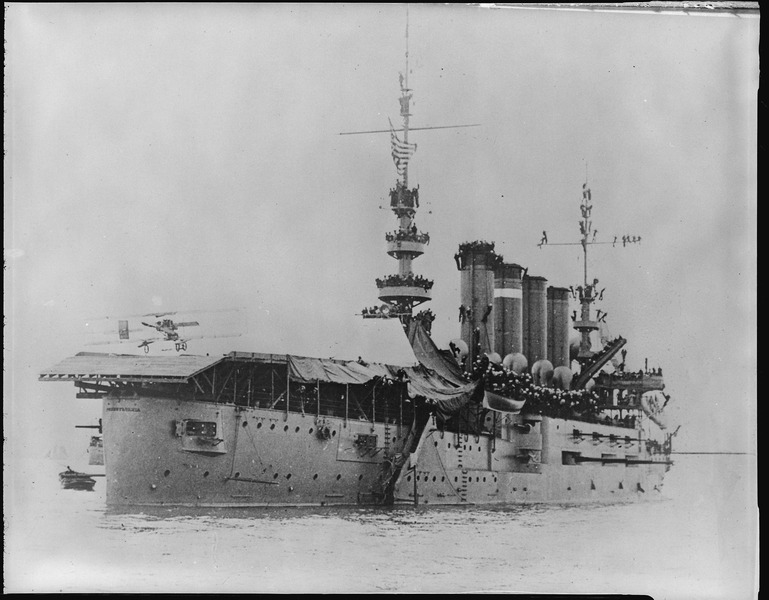

Since Ely, still in contract for Curtiss for meetings was scheduled to make a shown in San Francisco by January 1911, Chambers arranged to have a ship made ready on the west coast. The best candidate chosen was the much larger, twice heavier armored cruiser USS Pennsylvania (later renamed Pittsburg). Anchored in San Francisco Bay, her long aft deck was chosen to built a 36 meters (120 feets) landing deck, built in wooden scaffolding over the aft turret and going from the stern to the aft superstructure. Still, braking a plane at that speed on just 120 feets was a daunting prospect, and if Ely offshoot, he was almost certain of a fatal collision or plung into the sea. Ropes and sandbags stretched across were installed: This was the early idea of an arresting system.

Still, Ely was wondering about off-shooting and a canvas awning was installed at the end of the platform, to precisely catch his Curtiss at the end. His pushed had been modified in between. To make the landing easier at lower speed, it had longer wings. Hooks to catch the cross ropes were fitted on the landing gear. Ely himself was given a padded football helmet and early “michelin-like” schock-proof combination made of bycycle inner tubes (Wright Bros. initial trade by the way).

When everything was set and done, Ely prepared to take off on the morning of January 18, 1911 and aim at the cruiser anchored in the balckground. Crowds lined the shore, boats also came and went to see from close the attempt. At 11:00 a.m., Ely took off from the Tanforan Race Track. He manoeuvered to place himself in line with the Pennsylania’s safe landing, and started his careful approach, judgig the distance and speed by what he already tested on land.

The first attempt was a success and the arresting equipment stopped him many feets shy of the end. Invited in the Captain’s mess he was greeted by a toast by officers and a few photographs came aboard to report his exploits. In the afternoon, the platform was cleared, the cruiser was pointed into the wind (like all carriers would do for many decades) and Ely took off without a hinch, thanks to the larger wings and longer track, made a long turn and approach the shore, flew past the crowd, to land safely at Tanforan. This exploit made headlines around the world, and confirmed to the Navy that aboard aviation was possible, opening a brand new field of possibilities. Sadly after being a household name and folk hero in the US, Ely lost his life in a crash in Macon, by October 19, 1911. He posthumouly earned the Navy DFC in 1933.

Most important models

Boeing model 2/3/5 (1916)

Aeromarine 39 (1917)

Curtiss H (1917)

Curtiss F5L (1918)

Curtiss VE-7 (1918)

Curtiss NC (1918)

Curtiss NC4 (1918)

Manufacturers

From Wright to Curtiss

Curtiss 18T, the American triplane

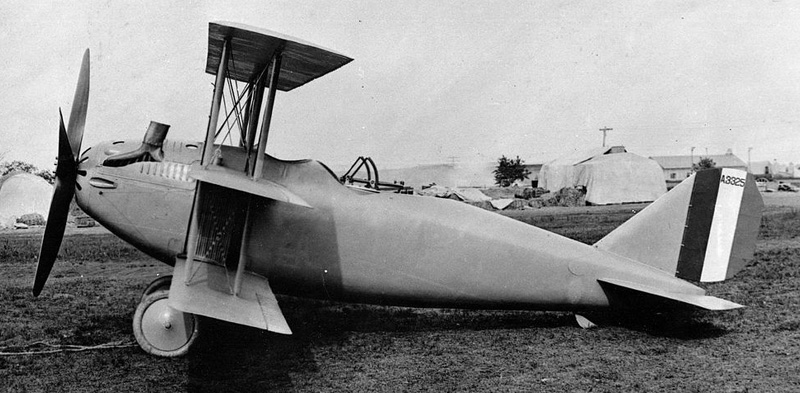

It’s the paradox that in the Wright Brother’s country, almost no US-built plane effectively took part in the operations against Europe, contrary to the troops, engaged en masse before completing training during the famous German spring offensive. The main reason, of course, was that between the declaration of war and effective start of the operations and the end of the war, delays were too short. Perhaps the best known and anlso best overall plane of that era was the Vought SE-7. Designed as an advanced trainer, for pilots already trained on other aircrafts which needed an high-performances aircraft preparing them for fighters, the Vought SE-7 proved even better than contemporary European Entent fighter. Only the test of fire with the German Fokker VII ad VIII -less the pilot’s own skills, would have show the American competence in this area where they had an initial lead.

The very strange Curtiss-Goupil Duck (1916) Built by Curtiss after drawings from 1883 patent by Alexander Goupil as an argument in patent war with the Wright Bothers.

Curtiss Jenny, which shaped an entire generation of pilots.

The earliest organism created was the Army Signal Corps, founded on August 2, 1909 and using Wright models for observation, which existed until April 6, 1917, when the Air Force, Navy and Marines had their own models, and of course the American Expeditionary Force (A.E.F.) which used a variety of models, mostly Europeans. There was a reason to this. When the excellent VE-7 thought for fighter conversion, the Army decided against it to the motive that for the sake of standardization and maintenance in operations it was better to stick with European planes. When later these models were ready for mass production, the armistice was signed.

Curtiss R-9J seaplane built for the Navy.

American Models

American plane Production during the war, April 6, 1917 to November 11, 1918:

- Boeing Model 4/Boeing EA

- Burgess H,I,J,S, Twin Hydro

- Curtiss 18-B, 18-T, JN-4/6, R-4L, SE-5

- Dayton-Wright DH-4

- Engineering Division USB/D, XB-1A

- Heinrich Pursuit Victor

- J.V. Martin Bomber

- Lewis & Vought VE-7/8/9

- L.W.F. Reconnaissance

- Martin GM series

- Motor Products SX-6

- Ordnance Engineering Orenco A-D

- Packard-Le Père LUSAC/LUSAGH/LUSAO-11/21

- Pigeon-Fraser Pursuit

- Pomilio Brothers BVL-8/12

- Standard H, JR, SJ, M-defence, Caproni, H.P. O/400, Twin Hydro

- Fisher Body Caproni, SJ-1

- Dayton-Wright SJ-1

- Wright-Martin SJ-1

- Thomas-Morse MB

- Wright-Martin M-8

- Hewitt-Sperry Automatic Airplane

- Dayton-Wright Kettering Bug

- B class blimp – various manufacturers

—–BLIMPS & Dirigibles————

Martin MB-2 bomber 1918

European Models with the AEF

Nieuport 28, the most common American Expeditionary Force fighter.

Edward Vernon Rickenbacker, was the Captain of the 94th Aero Squadron and won a total of 26 victories (4 shared), ranking as American WW1 top ace, and was awarded the Medal of Honor, Distinguished Service Cross, the Legion Honneur Officier and Légion d’honneur, Croix de Guerre 1914-1918 for his service with the famous Lafayette escadrille. Frank Luke Jr. followed as Lieutenant of the 27th Aero Squadron with 18 victories (4 shared) killed in Action on 29 September 1918.

Here, top ace Eddie Rickenbacker and his own Nieuport 28. Other 10+ aces gained fame in British service, like Captain Elliott White Springs for No. 85 Squadron RAF, and later 148th Aero Squadron after his transfer and claiming 16 victories (3 shared), Kenneth Russell Unger Lt. No. 210 Squadron RAF with 14 victories (4 shared), and George Augustus Vaughn Jr. Lt. No. 84 Squadron RAF, 17th Aero Squadron with 13 victories (7 shared), transferred to Air Service, US Army in August 1918 and Captain Clive Wilson Warman, No. 23 Squadron RAF (12 victories). In all, US Service counted at armistice day 17 former aces in French sercice (like Raoul Lufbery), 53 in British service and 50 in US service (not counting those transferred). They flew in the majority the Nieuport 28, and some the SPAD XIII they found quite superior.

Here, top ace Eddie Rickenbacker and his own Nieuport 28. Other 10+ aces gained fame in British service, like Captain Elliott White Springs for No. 85 Squadron RAF, and later 148th Aero Squadron after his transfer and claiming 16 victories (3 shared), Kenneth Russell Unger Lt. No. 210 Squadron RAF with 14 victories (4 shared), and George Augustus Vaughn Jr. Lt. No. 84 Squadron RAF, 17th Aero Squadron with 13 victories (7 shared), transferred to Air Service, US Army in August 1918 and Captain Clive Wilson Warman, No. 23 Squadron RAF (12 victories). In all, US Service counted at armistice day 17 former aces in French sercice (like Raoul Lufbery), 53 in British service and 50 in US service (not counting those transferred). They flew in the majority the Nieuport 28, and some the SPAD XIII they found quite superior.

- Dorand A.R.1/A.R.2

- Breguet 14

- Caudron G.3/4, R.11,

- Farman F.40/50

- Morane-Saulnier P/MoS.21 – AI/MoS.30

- Nieuport 10/12/17/21/23/24/27/28/80/81/83

- Salmson 2 A.2

- Sopwith 1 A.2

- SPAD S.VII/XI/XIII/XVI

- Voisin VIII/X

- Airco DH.9/504K

- Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2a/F.E.2b/S.E.5a

- Sopwith Camel F.1/Dolphin

- American Expeditionary Force (A.E.F.)

- Ansaldo S.V.A. 10

- S.I.A. 7B-1

Aeromarine

Aeromarine

The Floatplane Company

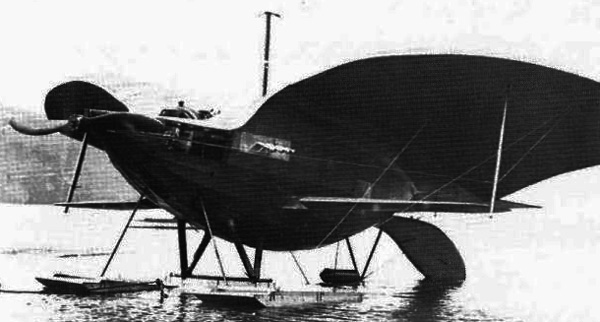

Aeromarine 700, prototype of floatplane torpedo-bomber, land or ship-based (1917)

Just like Supermarine later in UK, Aeromarine object was obvious as a company: Manufacturing seaplanes and floatplanes. This company was founded in Keyport, New Jersey, USA, by Inglis M. Upperçu, operating from 1914 to 1928 and until 1930 as the Aeromarine-Klemm Corporation after its fusion with Klemm. After Uppercu, the company was also headed by Joseph J. Boland, while Harry Bruno was its promoter, and producing not only about twenty planes but also numerous aircraft engines. Since the beginning the company targeted the Navy with dedicated long range patrol flying boats. The best known and prolific models were the 39 and 40 produced during the Great war. After the war, the company reconverted to the civilian market and opened early regularly scheduled flights, well helped by Harry Bruno insight and flair for potential of transportation airflight. From 1928, Aeromarine began producing mostly Klemm aircraft designs, but did not survived the Great Depression. Aeromarine engines were still produced after the closure of the company through the Uppercu-Burnelli Corporation.

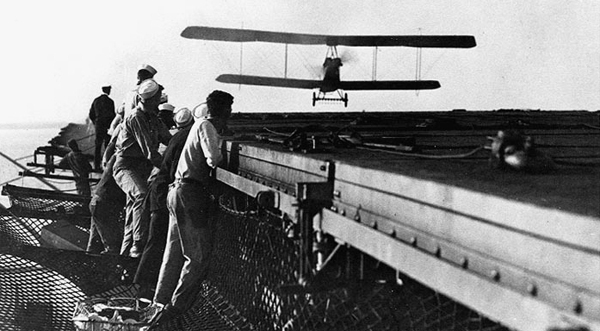

Aeromarine 39 onboard USS Langley during landing trials in October 1922.

Models

Production during the war, as shown here, was spread between licence production for De havilland, and the 2-seat amphibian trainer Model 39.

- Aeromarine Model B (1910) Canard prototype

- Aeromarine model 1914 Canard prototype

- Aeromarine 39 (1917): 150 produced – two-seat land-or-water based trainer

- Aeromarine M-1 (1917): 6 produced – advanced trainer

- Aeromarine 700 (1917): 2 prototypes – torpedo bomber

- Aeromarine DH-4B (1917): 125 licence-built Airco DH.4 for de Havilland

- Aeromarine 40 (1918): 50 built – Two-seat flying boat trainer

Aeromarine 39 (1917)

Specifications Aeromarine 39:

-Length: 29 ft 5 in (8.97 m), Wingspan: 36 ft (10.97 m), Height: 10 ft 5 in (3.18 m), Wing area: 330 ft² (30.7 m²)

-Empty weight: 1,231 lb (558 kg), load 180 lb (82 kg)

-Crew: 1 or 2

-Powerplant: Le Rhône 9J Rotary, 110 hp (82 kW)

-Performances: Top speed 90 mph (145 km/h), Cruise 75 mph (121 km/h), Range 250 mi (402 km), Ceiling: 16,000 ft (4,876 m), Climb: 700 ft/min (3.6 m/s)

-Armament: 2x synchonized 0.303 Vickers machine guns.

Aeromarine 39 on trials testing Pratt’s arresting hook

Aeromarine 40 (1918)

Specifications Aeromarine 39:

-Length: 29 ft 5 in (8.97 m), Wingspan: 36 ft (10.97 m), Height: 10 ft 5 in (3.18 m), Wing area: 330 ft² (30.7 m²)

-Empty weight: 1,231 lb (558 kg), load 180 lb (82 kg)

-Crew: 1 or 2

-Powerplant: Le Rhône 9J Rotary, 110 hp (82 kW)

-Performances: Top speed 90 mph (145 km/h), Cruise 75 mph (121 km/h), Range 250 mi (402 km), Ceiling: 16,000 ft (4,876 m), Climb: 700 ft/min (3.6 m/s)

-Armament: 2x synchonized 0.303 Vickers machine guns.

Burgess

Burgess

The first licenced manufacturer (1910-1918)

Burgess Company and Curtis, Incorporated started in 1910 after W. Starling Burgess and Greely S. Curtis (which later funded his own affair), co-founders, and Frank Henry Russell (Former manager of the Wright Company’s Dayton factory) funded it in 1910. An offshoot of the earlier W. Starling Burgess Shipyard (Marblehead, Massachusetts), the company was simply known as “Burgess”. It became the first licensed aircraft manufacturer in the United States starting in February 1911 with Wright, charged licensing fees of $1000 per aircraft, $100 per exhibition flight. The 1912 Burgess/Wright Model F had pontoons in violation of the Wright’s license agreement, which was terminated by mutual consent in January 1914. The manufacturer became the Burgess Company short, to avoid confusion with the new Curtiss Company. However the latter continued as Treasurer and major shareholder of Burgess. W. Starling Burgess designed (and flight tested) many of his new models out of Marblehead plant while Curtis acted as financial and engineering adviser and Frank Henry Russell was the head of production operations. Soon after, the Burgess Company was acquired by Curtiss and from there, operated as a manufacturing subsidiary. Burgess therefore concentrated from 1916 on Curtiss’s naval training aircrafts under the Burgess name; It was not bankruptcy but fire that destroyed all the factory assets on November 8, 1918, ended the story.

Burgess Company and Curtis, Incorporated started in 1910 after W. Starling Burgess and Greely S. Curtis (which later funded his own affair), co-founders, and Frank Henry Russell (Former manager of the Wright Company’s Dayton factory) funded it in 1910. An offshoot of the earlier W. Starling Burgess Shipyard (Marblehead, Massachusetts), the company was simply known as “Burgess”. It became the first licensed aircraft manufacturer in the United States starting in February 1911 with Wright, charged licensing fees of $1000 per aircraft, $100 per exhibition flight. The 1912 Burgess/Wright Model F had pontoons in violation of the Wright’s license agreement, which was terminated by mutual consent in January 1914. The manufacturer became the Burgess Company short, to avoid confusion with the new Curtiss Company. However the latter continued as Treasurer and major shareholder of Burgess. W. Starling Burgess designed (and flight tested) many of his new models out of Marblehead plant while Curtis acted as financial and engineering adviser and Frank Henry Russell was the head of production operations. Soon after, the Burgess Company was acquired by Curtiss and from there, operated as a manufacturing subsidiary. Burgess therefore concentrated from 1916 on Curtiss’s naval training aircrafts under the Burgess name; It was not bankruptcy but fire that destroyed all the factory assets on November 8, 1918, ended the story.

The Burgess-Dune BD-9 floatplane over the SS Asbury Park: A very unusual delta biplane configuration, which left an excellent frontal view

Models

Burgess concentrated on military seaplanes and other models. The Burgess H (S.C. No. 9) in August 1912 became the first military tractor. The Model F seaplane (Wright Model B design with pontoons) started in in September 1913, was used by the Signal Corps in the Philippines-based flying school. In December 1914, one of these (S.C. No. 17) tested a two-way air-to-ground radio communications. Outside the Curtiss N-9 which production started in 1916 (681 for the Navy) Burgess also manufactured the Herring-Burgess A which controls were designed by Augustus Herring, the Model B trainer, the model D or “Curtiss pusher” (1 built), the Model E, a Grahame-White Baby licenced copy (1 built), and the Burgess Model H (6 or 7 depending on sources). The Burgess Model G was only a blueprint of a modified Wright Model B, while one Burgess HT-2 Speed Scout was tested by the navy and one Burgess HT-1 Scout by the Army in the Philippines, the Burgess Model I was a seaplane also used by the Army in the same area, the Burgess J Scout (1 built) was a modified Wright Type C. The Burgess Type O Gunbus was a successful pusher fighter biplane only delivered to the british RNAS, the Burgess Model S was a navy flying boat and the Burgess Model U, an army one, both seeing a small production. Another model was a collaborative effort: The Burgess-Dunne was a licenced production, Canada’s first military aircraft. it was a tailless biplane designed by J. W. Dunne in UK with central floats. it was also tested by the U.S. Navy in 1914, a derivative named Burgess-Dunne AH-7 in 1914, while the Army purchased a single one as a replacement in 1913. Here follows true production models of the Company.

A single Burgess model D was tested by the Army.

A single HT-2/HT-B “Speed Scout” was used by the Navy, but here a model H is shown.

Blueprint of the 1916 Burgess HT-B (aviastar.org)

Burgess Gunbus for the RNAS (aviadejavu.ru)

- Burgess Model B (1910): (?) Biplane pusher

- Burgess Model H (1912): (6-7) Biplane tractor

- Burgess Type O Gunbus (36)

- Burgess Model S/U (12) floatplane

- Burgess-Dune D.8 (4) Delta-wing biplane

Burgess B

To Come

Burgess H

The Burgess H was used by the 1st Aero Squadron, North Island (later Rockwell Field), San Diego, California.

To Come

Burgess-Dunne D.8

Also called Dunne D.8 this was a rare, but successful V-wing biplane, here shown at Farnborough, 11 March 1914.

The Burgess-Dunne was the result of acquiring the licence for producing the remarkable D.8, mostly as single-float planes, and called Burgess-Dunne BDI. First flown in March 1914 piloted by Clifford Webster this plane had wingtip floats but for the rest was a faithful copy of the v-shaped biplane D8, however with a fuselage fitted with a nacelle containing a more enclosed cockpit. This single-seater called Burgess-Dunne BD had a more powerful 100 hp (75 kW) Curtiss OXX2 water-cooled engine. For stability and balance it was moved forwards, while the fuselage was shortened and the radiator moved between the engine and pilot (this was a pusher). The central float was 5.38 m long, of flat-bottomed and single step design.

Two prototypes were built and tested, but on the second, BDH, a second seat was added in place of the single radiator (now two, moved elsewhere). The Canadian government acquired it for its new Aviation Corps (The first Canadian military plane) which was to participate in World War I, but was badly damaged in transit and eventually never repaired. The third prototype was a two-seater powered by a Salmson M-9 radial engine (135 hp) used by the US Signal Corps, while two more were ordered by the US Navy (Type AH-7 and AH-10). They had a lighter 90 hp (67 kW) Curtiss engine and 100 hp Curtiss engine respectively, setting the American altitude record (10,000 ft, 3,050 m) on April 1915. The Burgess-Dunne BDF was another prototype, a three-seater flying boat with a span increased to 53 ft (16 m).

Characteristics

Wingspan: 46 ft 0 in (14.02 m), 545 sq ft (50.6 m2) area.

Weight: 1,400 lb (635 kg) empty, 1,900 lb (862 kg) loaded.

Engine: Gnome 7-cylinder rotary, 80 hp (60 kW), top speed: 56 mph (90 km/h; 49 kn), climb in 500 ft/min (2.5 m/s)

Burgess Type O “Gunbus”

To come

Glenn-Martin

Glenn-Martin

From records and movies to Production

Glenn martin starring in “A Girl of Yesterday” with Mary Pickford, 1913. Behind, his martin T.

Glenn L. Martin was born in Macksburg, Iowa, January 17, 1886 and after moving to Salina, Kansas, in a wheat farm he built many kites, being paid for it eventually. After studying business at Kansas Wesleyan he received an honorary Bachelor of Science degree. He was soon fascinated with flight, seeing the feats of the Wright brothers. In 1909 he started building a Curtiss June Bug model and later modified it used silk and bamboo, making a short flight. In 1912, he flew a seaplane from Newport Bay (California) to Avalon (Catalina Island) and back, breaking the English Channel record with 68 miles (109 km), winning a $100 prize. In 1913, he lost his competition in the Great Lakes Reliability Cruise (900 miles or 1,400 km) race, hitting a wave at high speed, low altitude and destroying the plane and went back on his business.

Martin MB-1 bomber. The company’s best seller during WW1

In 1912, Martin created a large workshop for airplanes in an old Methodist church in Los Angeles, stunt-flying at fairs to raise money and make advertisement, also trying to be recruited as a pilot for movies. He played indeed the role of a dashing hero in the silent A Girl of Yesterday in 1915 co-starring with Mary Pickford. Founding the Glenn L. Martin Company he devised models for the military and in 1916 was merged with the Wright Company, giving the Wright-Martin Aircraft Company. A second Glenn L. Martin Company was created by him in 1917, later merging in turn with the American-Marietta Corporation in 1961, giving the Martin Marietta Corporation, joining Lockheed in 1995 (as Lockheed Martin). During his WW1 years he designed a numbers of models, with a best seller, the MB-1 bomber, followed by the MB-2 and following models in the interwar culminating with the Collier Trophy for the B-10 bomber in 1932. The company had meanwhile from 1928 onwards moved to Maryland, bringing much-needed jobs on the area. One of the most famous WW2 models of the company was the Martin B-26 Marauder, but the company also built other heavy-duty planes like the A-22 Maryland bomber, PBM Mariner and JRM Mars, and also produced the very complicated Boeing B-29 Superfortress. After he passed out in 1955 his company would built numerous advanced experimental jets and became a prominent aerospace company, between the Vanguard rocket, ballistic missile program and satellites, up to the space shuttle.

WW1 Martin Models:

- Martin T (trainer, 1913) (?)

- Martin S (trainer floatplane, 1915) (c6-16)

- Martin MB-1 bomber (1918) (20)

- Martin NBS-1/MB-2 bomber (1918) (8?)

Curtiss

Curtiss

The largest American aircraft manufacturer in 1918

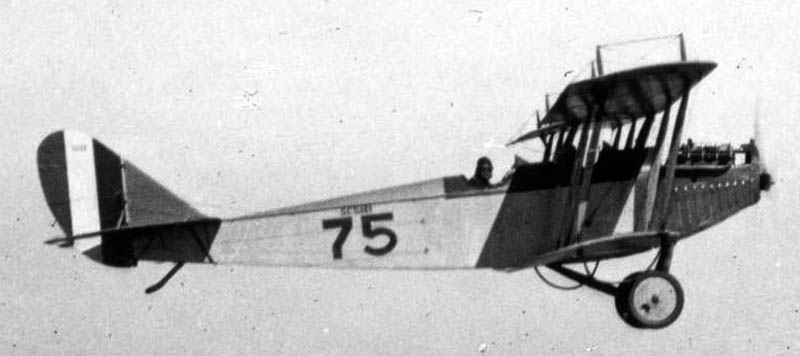

Curtiss N°1, 1909, first plane bearing this name, a Wright-style pusher also nicknamed Gold Bug or Golden Flyer

The company known as from Curtiss Aeroplane & Motor Company, Ltd was formed in 1916 by Glenn Hammond Curtiss which produced a wide variety of successful warplanes during the last years of the Great war but also later in the 1920, turning also to the civilian market with equal chance and merged with Wright Aeronautical in 1929 (Curtiss-Wright Corporation). At the origin, Glenn Curtiss joined scientist Dr. Alexander Graham Bell in 1907 as a founding member of the Aerial Experimental Association (AEA), first American aeronautical research and development organization, according to Bell for the “love of the art and helping each other”. But two years after in 1909, it was disbanded, and Curtiss decided to capitalize in the team knowhow to create the Herring-Curtiss Company with Augustus Moore Herring, later renamed the Curtiss Aeroplane Company th next year. In 1916, the company changed again for “Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company” and moved to Hammondsport, and Bath, both in New York state while Burgess of Marblehead, Massachusetts became a subsidiary. In November 1918, the company was championed as the largest aircraft manufacturer in the world, with 21,000 employees in both New York/Buffalo plants alone, and a record 10,000 aircraft, at a 100 weekly rate.

Only two prototypes of the excellent Curtiss model J (1914) were tried by the Aviation Section, U.S. Signal Corps

Curtiss needed to expand with the first orders and both the headquarters and manufacture were relocated in Buffalo, New York, a potent transportation hub with plentiful manpower and technical expertise, and wealthy investors to grow. An engine factory, the Taylor Signal Company-General Railway Signal Company was added to the complex while another dependency was opened in Toronto, Ontario for production and training, with the creation of the first Canadian flying school in 1915. In 1917, the Wright and Curtiss suceeded at the end of a violent “patent war”, to block the building of new airplanes and the U.S. government pressured the industry to create a cross-licensing organization called the Manufacturer’s Aircraft Association, strongly opposed at first by the two corporations. But then, Curtiss found a juicy market with the needs of the US Navy, and started to lobby to provide both planes and training for USN pilots. 144 Model F trainer flying boat were first ordered, and while Curtiss successfully lured B. Douglas Thomas from Sopwith as designer for this second order, the Model J trainer, and later the JN-4 “Jenny”, built by very large numbers. The Canadian JN-4 were nicknamed the “Canuck”, and five other manufacturers were soon licenced for it ti cope with the enormous orders. Numerous JN-4s after the war formed another generation of pilots including Amelia Earhart. The model became an icon from the company, right up to the fall of the twenties.

The Curtiss 18T was championed as the “fastest plane in the world” at 163 mph (262 km/h) in August 1918 with its Curtiss K-12 water-cooled 12-cylinder vee engine, 400 hp (298 kW)

The next Curtiss HS-2L flying boat became a staple of USN anti-submarine assets in the Atlantic, operated from Nova Scotia (Canada) as well as France and Portugal. The next Curtiss F5L was co-designed by John Cyril Porte from the Royal Navy, generally similar to the Felixstowe F.3. They evolved into the NC-4, first Atlantic crosser in 1919. But these were the last government orders before many cancellations. In 1920 indeed, Glenn Curtiss retired and moved to Florida, staying as advisor on design, but the new CEO was now Clement M. Keys. After winning the prestigious Schneider Cup twice (1923,1925) and the Pulitzer Trophy Race in 1925 and both the Schneider Trophy again (by Jimmy Doolittle) the company secured media attention, but the company only suvived with ciilian models like its best-seller the Robin (1928, 769 sold). The company became the Curtiss-Wright Corporation and started in a new path and also sponsored the Atlantic Coast Aeronautical Station.

The Curtiss 1918 Curtiss GS, a Navy floatplane fighter (6 prototypes)

Models

As usual, production models are in bold, production figures are under brackets.

- Curtiss No. 1 (1909)

- Curtiss No. 2 (1909)

- Curtiss Model D (1911)

- Curtiss Model E (1911) (50?)

- Curtiss Model F (1912) (150?)

- Curtiss Model J (1914)

- Curtiss Model H (1914) (478)

- Curtiss Model K (1915) (51+ for Russia)

- Curtiss C-1 Canada (1915) (12)

- Curtiss JN-4 Jenny (1915) (6813)

- Curtiss Model L (1916) (20?)

- Curtiss Model N (1916) (560)

- Curtiss Twin JN (1916) (8)

- Curtiss Model R (1915) (290)

- Curtiss Model S (1916) prototypes (6)

- Curtiss Wanamaker Triplane (1916)

- Curtiss HS (1917) (1178)

- Curtiss GS (1918) (6)

- Curtiss HA (1918) (6)

- Curtiss JN-6H (1918) (1035)

- Curtiss 18T (1918) USN Fighter (triplane) (4)

Curtiss E (1911)

(To come soon)

Curtiss F (1912)

(To come soon)

Curtiss H (1914)

(To come soon)

Curtiss C1 Canada (1915)

(To come soon)

Curtiss R (1915)

(To come soon)

Curtiss JN-4 “Jenny” (1915)

(To come soon)

Curtiss L (1916)

(To come soon)

Curtiss Twin JN (1916)

(To come soon)

Curtiss N (1916)

(To come soon)

Curtiss HS (1917)

(To come soon)

Curtiss JN-6H (1918)

(To come soon)

Packard Lepere

Packard Lepere

PACKARD LE PERE LUSAC-11: French Design, American Manufacturing

The LUSAC 11 was ordered to a staggering 3 525 orders, but the war bring cancellation and only 28 out.

When the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) landed in France in 1917 to relieve allied exhausted troops facing the onslaught of Eastern-front German reinforcements, the air force component did not even existed. When it was created, it had to make due with French Planes. The Signal Corps by then only counted 55 aircraft unfit for combat. But of course, there were plans to produce French designs (since French manufacturing industry was already overcapacity) in the United States. Therefore a French Aeronautical Mission was sent to the United States, tasked by the Engineering Division of the United States Army Air Service to design various designs. One of these was a two-seat escort fighter. Georges Lepère, a member of this Mission soon drawn a prototype. The latter was a captain and military engineer, already responsible of collaborative work for other French manufacturers like Breguet.

He designed two-bay biplane with equal span upper and lower wing and forward stagger, wood and fabric, the fuselage consisting in a wooden box girder covered by plywood, and powered by a 425 hp (317 kW) Liberty L-12 engine. It was cooled by a radiator mounted into the upper wing. Its armament consisting in a pair of cal.30 (7.62 mm) standard browning machine guns, synchronized on the engine hood, and pair of Lewis guns mounted on a Scarff ring around the observer’s cockpit, quite a deadly combination worthy of a relatively heavy fighter. But as heavy it was, the sturdiness of its construction allowed the engine to give its full potential and the LUSAC 11 (For “LePere United States Army Combat 11”) was very fast indeed.

In reality the LUSAC-11 was the perfect example of a fast and powerful “jack of all trades”, able to perform fighting missions as well as light bombing and reconnaissance. Packard Motor Car Co. of Detroit, Michigan provided the working space facilities, and additional engineers to the French team. The first of three prototypes flew in April 1918. Two other followed, making numerous demonstrations received generally favorable reviews from test pilots at Wilbur Wright Field, Ohio. So much so, that without delaying much, the Bureau of Aircraft Production launched a massive order to Packard of 3525 planes. But the tooling and setting up of the production just ended, and in November 1918 only 28 planes has been delivered in total (some sources are telling 30, perhaps taking in account the prototypes). Not only none was sent in Europe and saw combat, but they served well in the Air Service for years. Specially modified LUSAC 11 even made headlines by setting a number of altitude records at Wright Field in the early 1920s. They were modified to reach 39,700 ft. with a turbo-supercharger. Photo on the right: LUSAC 11 in flight, 1920, record-setter over McCook Field.

There were no LUSAC 11 in exhibition in the US as the only preserved LUSAC 11 went to France just before the end of the war. But in 1989 the Musee de l’Air in Paris, France sold it to the USAF National Museum, in quite bas state as it was part of the reserves. After extensive restoration by the museum it went on display in 1992, marked as the one used by Allied test facility in Orly, France, late 1918.

Specifications

Dimensions: Length: 25 ft. 3 in, Span: 41 ft. 7 in, Height: 10 ft. 7 in.

Weight: 3,746 lbs. loaded

Propulsion: Liberty 12, 400 hp,

Performances: Top speed 136 mph, 118 mph cruising, Range: 320 miles, Ceiling: 20,200 ft.

Armament: Two .30-cal. Marlin and two .30-cal. Lewis machine guns

Standard Aicraft Co.

Standard Aicraft Co.

From Sloan to Standard

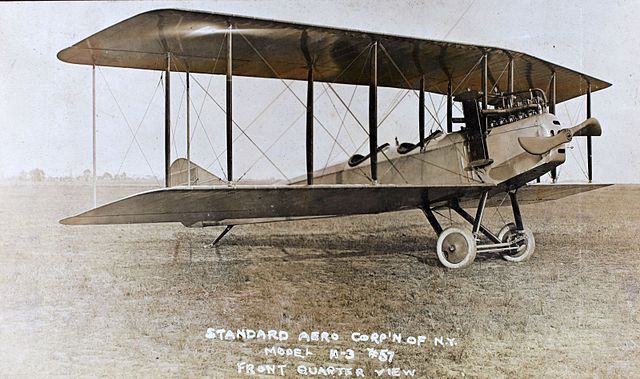

Standard J-1 skeleton, USAF Museum

The Standard Aircraft Corporation was founded in Plainfield, New Jersey, in 1916, anticipating American entry into the War, despite the isolationism policy that prevailed at that time. Standard Aircraft became one of the first supplier of planes to the U.S. Army Signal Corps, with the Sloan H (Standard H-2/H-3) as well as the Navy’s H-4H floatplane. At that time the Sloan company was renamed Standard Aircraft Company. However the most prominent model became the Standard J trainer, following the lines that made the success of the Curtiss JN-4. This plane began as the SJ prototype, and later the J-1/SJ-1 production started with about 800 been delivered. However at that time engine attribution policy gave it the Hall-Scott A-7 air-cooled straight-4 engine rated for 100 hp (75 kW). There were attempts later to replace it, or go around the problem, through several variants, but without success. JRs and JR-1Bs were also built but in fewer quantities, and made the core of the American Post Office after the war.

Standard was also seduced by the prospect of deliverin the Army an American fighter, and this was the E-1. Under-powered and late in the game, only 100 were delivered and served as advanced trainers back Home, since it was preferred for standardization to keep French models for the frontline in Europe. And about fifty only of these fighters were actually armed, the others just having provision fittings for a pair of hood machine-guns, like the M-Defense. To produce more aircrafts, the Corporation created a new plant in 1918 between Elizabeth and Linden boundary. After the end of the war, the Corporation will go on under the direction of Designer Charles Healy Day and barnstormer/showman Ivan Gates, aimed at both the civilian and military markets. This became the Gates-Day Aircraft Company, later renamed again New Standard Aircraft Company in 1927. most successful models became the Gates-Day D-24 and the New Standard D-25.

Standard H2/H3 series

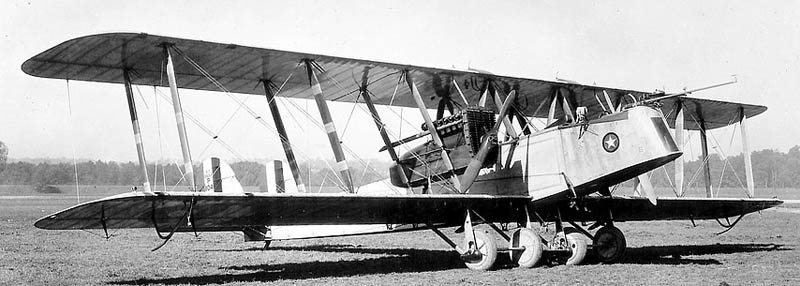

Standard H3, N°3 #57, front quarter view near New York

The Standard H-2 was an early American Army reconnaissance aircraft, first ordered in 1916 and designed by the Standard Aircraft Corporation. It derived from the Sloane H-2, an open-cockpit, three-seater tractor biplane. It was propelled by a 125 hp (90 kW) Hall-Scott A-5 engine. However only three prototypes were built for tests. This led to the next iteration of the H series, the improved H-3, which kept the engine. After succesful tests, this model gained an order of nine planes. The US Navy was soon interested by a naval variant, and ordered three H-4H floatpanes. Later two Standard H-3s were sold to Japan, while three more were built locally by the Provisional Military Balloon Research Association (PMBRA) in 1917. These late H3s had a 150 hp (110 kW) Hall-Scott L-4 engine and were used as trainers from May 1917 to March 1918, with some preventions due to their temperamental flight characteristics, borderline with dangerous.

Standard H4H floatplane USN

Specifications

Dimensions: Length 27 ft 0 in (8.23 m), Wingspan: 40 ft 1 in (12.22 m)

Weight: 2,500 lb (1,134 kg), Gross weight: 3,300 lb (1,497 kg)

Propulsion: Hall-Scott A-5 straight-6, 135 hp (101 kW), 68 US gal (57 imp gal; 260 L)

Performances: 84 mph (135 km/h; 73 kn), Endurance 6 hr, 10 minutes to 3,400 ft (1,000 m)

Armament: None.

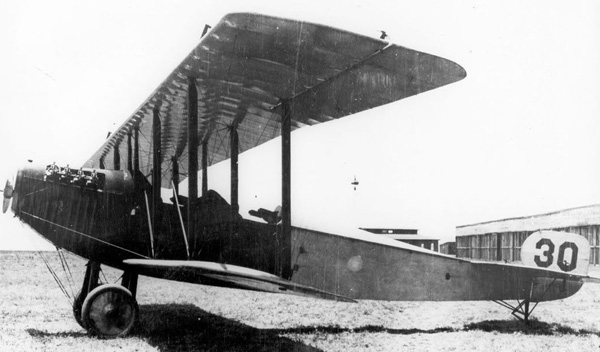

Standard J series

The Standard J as of today

This two-seat basic trainer buuilt as a sturdy two-bay biplane was produced from 1916 to 1918. It was powered by a four-cylinder inline Hall-Scott A-7a engine. Made of wood with wire bracing, and fabric. It was seen as a stopgap waiting for the Curtiss JN-4. Made by Ealy Day as a derivative of the Sloan H series under Standard Aero Corporation. Standard, Dayton-Wright, Fisher Body and Wright-Martin, delivered 1,601 of them in one year, between June 1917 and June 1918.

The Standard J-1 compared to the Curtiss JN had a swept-back wing platform, plus triangular king posts above the upper wings. Also the front legs of the landing gear were mounted behind the lower wing. Produced in large numbers the four-cylinder Hall-Scott A-7a engine was unreliable and vibrated badly to the point that in June 1918, all J-1s were grounded. JN-4s replaced them for training. At $2,000 per aircraft it was not bankable to have them converted with the Curtiss OX-5 engine. Other contracts were canceled and most were sold as surplus or scrapped. Curtiss even bought many surplus J-1s to be convertd with new engines for resale. Civilian flying schools happily received them also for barnstorming operations, until in 1927 because of new regulation banning wooden structures in aircrafts.

The evolution started with the Sloan H series trainer from 1913, derived into the Standard H series by Standard (same plane), derived into the Standard J, the Standard J-1 for the U.S. Army, SJ-1 with more forward wheels to prevent noseovers, JR-1 advanced trainer, JR-1B mail carrier postwar (also called Standard E-4).

Specifications

Dimensions: Length 26 ft 7 in (8.10 m), wingspan: 43 ft 11 in (13.39 m), Height: 10 ft 10 in (3.30 m), Wing area: 429 sq ft (39.9 m2)

Weight: Empty 1,350 lb (612 kg), Gross weight: 1,950 lb (885 kg)

Propulsion: Hall-Scott A-7 air-cooled straight-4 engine, 100 hp (75 kW) 31 US gal (26 imp gal; 120 L)

Performances: Top speed 68 mph (109 km/h; 59 kn), Range: 350 mi (304 nmi; 563 km), 10 minutes to 2,600 ft (790 m)

Armament: None

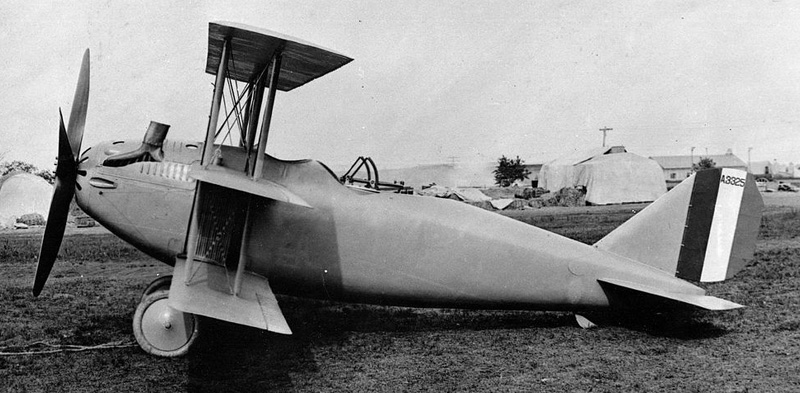

Standard E1 series

The Standard E1, a little-known American fighter of WW1.

The Plainfield manufacturer designed its last mode, the Standard E-1 as an early fighter aircraft tested in 1917. Only pursuit aircraft manufactured in the United States until that point, it was not ready on time to be sent in Europe and see action. The E-1 was an open-cockpit single-seat tractor biplane, powered by an 80 hp (60 kW) Le Rhône or 100 hp (75 kW) Gnome rotary engine, both largely available and already licence-built. Depite being lightweight, the E1 was not agile and fast enough for a 1917 fighter. The Army decided to convert the order into 128 advanced trainer, 30 powered by the 100 hp Gnome and 98 by the 80 hp LeRhone C-9 rotary engine.

Specifications

Dimensions: Length: 25 ft. 3 in, Span: 41 ft. 7 in, Height: 10 ft. 7 in.

Weight: 3,746 lbs. loaded

Propulsion: Liberty 12, 400 hp,

Performances: Top speed 136 mph, 118 mph cruising, Range: 320 miles, Ceiling: 20,200 ft.

Armament: Two .30-cal. Marlin and two .30-cal. Lewis machine guns

Standard E1, showing its streamlined engine cowl, in a training unit after the war.

Thomas-Morse

Thomas-Morse

Funded by British expatriates

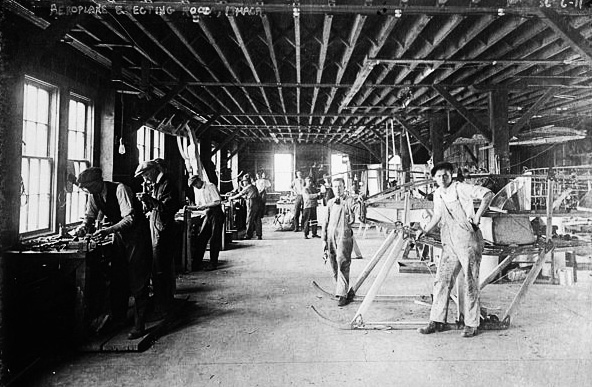

The Company Workshop at Ithaca, New York, circa 1915

The Company Thomas Morse is unknown to Fanboys of WW2, but most of its assets were passed in 1929 to Consolidated, which built several marking planes and especially the Liberator bomber. The company was founded in 1910 by two English citizens, William T. Thomas and his brother Oliver W. Thomas, and therefore started as the Thomas Bros. Company of Hammondsport, New York. The company later moved to Hornell, New York, and then ended at Bath, New York, within the same year, but it was by then little more than a glorified workshop. Their first public show would have been the Livingston County Picnic in 1912.

Their Hydro-aeroplane was indeed scheduled to fly but strong winds prevented this. They showcased their plane in a static mode, but they would have another occasion later. From 1913, the company created the Thomas Brothers School of Aviation at Conesus Lake, McPherson Point (Livingston County) in the same state, also for pilots to train on hydroplanes. The same year, the company known as the Thomas Brothers Aeroplane Company move again and was settled in Ithaca, New York by December 7, 1914. With the war, their military production started. In 1915, they built T-2 tractor biplanes. The ironic part is their chief designer was then Benjamin D. Thomas, which had no relation with the brothers but was also an English subject, experienced at Vickers, Sopwith, and Curtiss.

No Photo found of the T-2. Instead this is the S4C assembly line. Thomas Morse was a prominent fighter maker of 1918 and the S4C “Tommy” the absolute best seller, with 461 delivered for the Army with French licenced Le Rhône engines.

The T-2 was built for the RNAS, but it was fitted with floats instead of wheels and also marketed to the US Navy as the SH-4. They replace the planned Curtiss OX engines by their own, funding the Thomas Aeromotor Company for that purpose. In 1916, whereas they approached bankrupcy, they won a contract from the US Army Signal Corps, which evaluated the D-5. But apart 24 orders previously for the RNAS, by January 1917 their financial difficulties were such that they had to negociate a merging with with Morse Chain Company (Frank L. Morse) to seek indirectly the financial backing of H T Westinghouse.

So in 1917 the company became Thomas-Morse Aircraft Corporation. They tried hard from then to market training biplanes to the US Army and with their backing succeeded to sold the versatile S-4/S-4E trainer/S-5 floatplane and Fighters of the MB series, since the Country at war badly needed planes. Postwar their MB-3 fighter (1919) became until 1925 the main U.S. Army Air Service fighter, also built by Boeing. They would produced other small peace time series until the O-19 observation biplane, but after joining the Consolidated Aircraft Corporation, as a Division, they completely ceased operations in 1934.

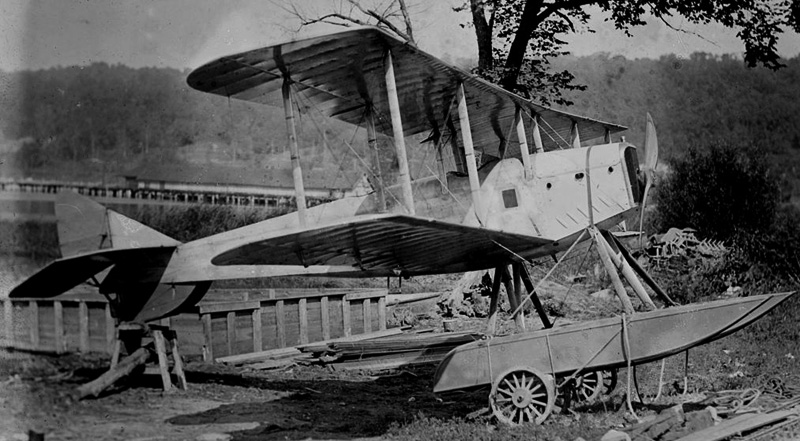

Thomas-Morse HS floatplane at Ithaca lake, New York

Most important Models

Probably the most famous model was the T-2 trainer, declined into many sub-products, and the Scout, probably the best single-seat fighter trainer of the US Air Service during the war. As usual production models are in bold, production figures in brackets.

- Thomas Brothers D-2 (2) 1915

- Thomas Brothers D-5 (2) 1915

- Thomas Brothers HS (2) 1915

- Thomas Brothers T-2 (26) 1915

- Thomas Brothers SH-4 (15) 1915

- Thomas Brothers S-4 (470) 1917

- Thomas-Morse MB-1 (2) 1915

- Thomas-Morse MB-2 (2) 1918

Thomas Bros. D-2/HS and D-5

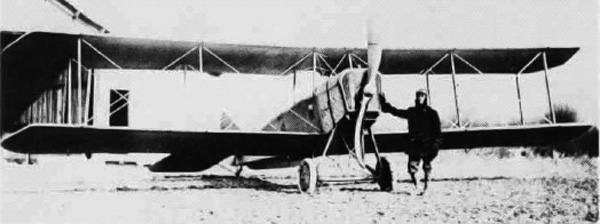

Thomas-Morse D-2 circa 1915. The 1916 D-5 was a very close copy, with the improvements bring on of the HS. Only two built for testings.

The D-2 was produced to only two planes (6 total, counting the HS and D-5) as an improved T-2. It had a 135 hp engine (top speed 132 kph), a 14.7 m wingspan, 9.1 m in length, 3.1 m hull width, and total wing area of 41 m2. This was a two-seats tractor sesquiplane, which weighted 1180 kg. The Thomas Brothers D-2 set an unofficial speed record for an American aircraft. It was soon declined into the HS for the United States Navy and D-5 for Aviation Section of the Army, the U.S. Signal Corps. It was propelled by a domestic engine, the Thomas Aeromotor Company 8-cylinder, water-cooled gasoline engine built on the basis of the 135-horsepower Sturtevant engine, which propelled the D-2. The Thomas 8 would propel some of the later aircraft produced by the company.

Thomas bros. HS of the Naval Air Service at pensacola in 1917.

The prototype D-2 first flight occurred in the spring of 1915, and it was able to reach 97.4 mph or 156.7 km/h, setting an unofficial speed record in the US, and about 100 to 102 mph (164.1 km/h) in another occasion, perhaps diving. Its climb speed was also excellent, 4500 feet (1371 m) in ten minutes. However only two prototypes were built and tested. The United States Navy was interested and ordered two planes in July 1915 of the HS version, with floats fitted under the wings and a small stabilizing float under the tail on skids. First flight occurred in late u or September 1915 at Cayuga Lake, Renwick Park. It showed the excessive drag take by the floats when turning, putting a heavy the train on the engine which overheated fast.

The radiator xas not up to the task. in the following winter, the prototype crashed during trials on the lake, when landing. It was rebuilt and modified in the same standard of the second USN model. The upper wing was extended by 350 cm, with enlarged ailerons on the upper panel only. The tail float was also modified. The first of the two models had a Sturtevant engine (accepted in January 1916) and the second had the Thomas 8 engine (June 1916). They were used for training and experiments with radiotelegraphy. In 1915, two D-5 powered by Thomas 8 engines were ordered by the Army, as traditional landing planes.

Thomas Bros. T-2

Designer Benjamin Douglas Thomas previously worked for Curtiss, where he designed the famous Curtiss Model J or “Jenny”. He at first did not receive any remuneration for his work, his remuneration being indexed on half of the future from aircraft sales. He began design work on a design he knew best, so the T-2 model (his first model) was a close copy of the Curtiss Model J and Curtiss Model H. This was a single-engine, two-seat biplane tractor powered by a 90-horsepower Austro-Daimler engine. First flight and trials were done with this model, but later production planes used by the RAN had the Curtiss OX-5 engine, also rated for 90 hp.

The T-2 flew for the first time on December 7, 1914 in Ithaca, and clearly one of the best aircraft of the time, flying at 83 mph(133 kph) with one passenger and carried an additional 450 kg load. Its ceiling was 3,800 feet (1,150 m) which it climbed in ten minutes. After the long test phase of early 1915, the British Admiralty ordered twenty-four T-2 delivered in two batches of twelve. No further orders were to follow, due to the Curtiss engines being in short supply. A naval derivative of the T-2, the SH-4, was later ordered.

Thomas-Morse MB1 (1915)

Possibly the first truly indigenous fighter plane designed and built in the U.S.A., only two were produced and not meeting expectations no further production took place. It was a monoplane, propelled by a 400hp Liberty 12, weighing 680 kg/1499 lb, 11.28 m (37 ft) in wingspan, 6.70 m (22 ft) in lenght and 2.56 m (8 ft 5 in) in height, armed with two 7.7mm MGs.

Thomas-Morse MB2 (1918)

It was designed by B. Douglas Thomas as the same time the MB-1 was built and tested. The MB-2 was powered by a 400 hp Liberty 12 engine, the first of two two-seat biplanes flying in November 1918. The Army was not impressed by the performance and no order came. Both prototypes were then scrapped. But Thomas-Morse would had more success with the MB-3 in 1919 (265 made).

Wright

Wright

The First American Plane

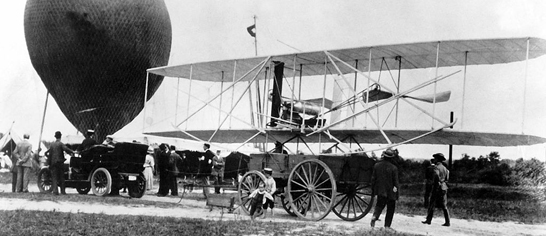

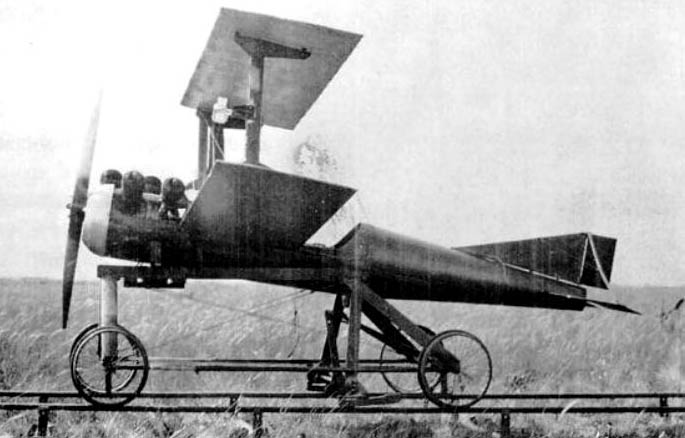

Wright Military Flyer at Fort Myer

The first flight. Worldwide. They did it. The Wright Brothers, two maverick crafty bicycle makers first leaved the ground on an heavier-than-air machine for a few seconds, fighting to find wind with an engine barely strong enough to tilt a wooden screw. That was in 1903. And homologated. But who known how many attempted this before, perhaps centuries ago. Just at the same time, flight claims had been made for Clément Ader, Gustave Whitehead, Richard Pearse, and Karl Jatho or Traian Vuia and Alberto Santos-Dumont*.

People already flew on lighter than air balloons for much longer, higher and farther than this, two centuries before. But a balloon was a slave of the wind, a toy of the elements, perhaps the hand of god, an unnatural thing capable of hanging there but not to fly. While planes were the only seemingly true artificial birds.

They looked and felt natural. And very promising. These contraptions, for all who went to study and craft these, try these with great enthusiasm, how far they were… from war ? The idea of using these for military applications didn’t cut with these pioneers. But that’s where the money was -at least when competition and prizes started to fade away.

*And some tried to disqualify their attempt as cheating, using skids, a launching ramp and strong wind, a catapult after 1903.

Wright-Martin Model V, last plane of the company. The company Wright-Martin only lived from 1916 to 1919 but the name lived on through engine manufacturing and on the other hand Glenn Martin. One of the reasons of its demise and short live was the ferocious Wright brother’s “patent war” with other aircraft manufacturers, the result of US cross-licensing wartime agreement practice.

The Wright Brothers were no different. Once they flew over and over again their famous Flyers I, II and III before officials, taking passengers in the process, each time higher, faster and further away. In 1907 they presented the “model A” the first produced in relatively large quantities (60) and licence-built in Europe. One was flown before French officials, some were sold to Germany. In the US, they gained recognition enough to motivate an order by the Aeronautical Division, U.S. Signal Corps at $25,000 plus $5,000 bonus 1909 apiece.

It was still a standard pusher, canard configuration with a 35-horsepower (26 kW) engine and carry two -the pilot and observer- on about 40 miles per hour (64 km/h) on 125 miles (201 km). That was quite an achievement given how fragile the contraption looked. So not only it could be used for reconnaissance but also liaison, carrying military VIPs on site faster than a train, in straight line over any obstacles. From then on, they declined the model B, C and D, and up to the Wright E-Pusher, the last classic model without a proper covered fuselage.

They never designed fighters, only observation and training models, but some floatplanes. The last in line of the classic planes was the model E, and it’s derivative Model EX, one-seat version also called “baby wright”. They were sold to the civilian market. There was no Wright model J, produced instead by Burgess, which acquired the license.

The Model R was essentially a competition plane, the model C a good heavy-duty mass-produced two-seats, two-propeller heavy duty aircraft which was widely produced and tried in bombing and strafing (with the first airborne machine-gun), carrying heavy loads, tried radio transmission and doing long runs missions, but was obsolete in 1914. The Models G, H and K were 1914-1915 prototypes, never ordered by the Army but introducing many advancements like a full bodied fuselage, ailerons and other innovations. The Model L was a conventional “2nd generation plane” difficult to associate with the traditional image of a Wright aircraft. Despite its apparent modernism, it was sluggish and heavy to maneuver, and was tested but never ordered. This was not the last plane of the company which became in 1916 the Wright-Martin Company until 1919. It should be added that the company produced its own engines, like the 1906 Wright 440 Engine (produced until 1912) and the 1911 Wright 660 Engine (until 1916). In 1919 indeed, the company moved to engine manufacturing only, as Wright Aeronautical, and designed the legendary Wright Whirlwind series and this famous name was later associated forever with USAF Aviation history through the ww2 winner Wright-Cyclone.

In 1918, Orville Wright will design the first ever guided bomb, called the Liberty Eagle, while in 1919 he designed the OW.1 Aerial Coupe, a civilian four-place enclosed cabin biplane for the Dayton Wright Airplane Company after the war. It was luxurious, with a roomy and well-furnished room, but also performed well, making an altitude record, but found no customer. This was the very last plane designed by the Wright Brothers.

Prewar models, From the model F to the model G

Indeed, the Model F marked a radical departure, dispensed with blinkers and curtains and using a proper fuselage for the first time. The engine was therefore replaced forward of the wings, and there was now a semi-standard tail with the rudders resting atop the elevator, and hinged it, rather than flexed. Moreover the fuselage was partly covered in aluminum to be nicknamed “Tin Cow”, also a radical departure over the previous “wood only” cage-like models. These planes were still that slow that they were flown in regular city suit. There was no such things as a helmet or goggles.

Wright 1918 Liberty Eagle, designed by Orville and Fred Nash. It was a small unmanned biplane from the Dayton Wright Airplane Company called Liberty Eagle and nicknamed “the Bug” designed as a guided missile, using a gyroscopic stabilizer, and the first attempt ever. Several were built and tested in Pensacola, Florida, half damaging their target. src: flyingmachines.ru.

Wright Factory Production

- Model A (military and civilian) 1909

- Model B (military and civilian) 1910

- Model C Heavy-duty and Floatplane (1912)

- Model R Competition one-seater (1911)

- Model H/HS 1914 prototypes

- Model K 1915 Seaplane prototype US Navy

- Model G 1916 advanced trainer prototype

Wright Military Flyer (1909)

The U.S. Army purchased its first aircraft in August 1909 after a demonstration fitted the specifications emitted by the Signal Corps, called “Specification 486” issued 23 December 1907. A Model A was carried and shown at Fort Myer, Virginia on 20 August 1908. There was a crash on 17 September 1908 killing Lt. Thomas Selfridge as passenger but depite all these ans all the successful tests that went before, the contract was maintained until 1909. The Wright Military Flyer was built with improved features and shipped to Fort Myer on 18 June 1909, showing a shorter wingspan, longer propellers and another gear ratio for the transmission in order to increase top speed, linked to the Army specs. The motor was also “broken in” to produce more horsepower. Tests started on 29 June 1909, with Orville flying. The speed test was performed with Lt. Benjamin D. Foulois on board taking the measure of 42.58 mph over 44 miles which with the Army accepted to pay the Wright company a substantial $25,000 for the Military Flyer with a speed bonus of $5000. It was further tested by the Army at College Park, Maryland, Wilbur training Lt. Frank P. Lahm and Lt. Frederic E. Humphries in October 1909, the first American military pilots. Pitch stability modifications made by Orville would lead to the Model B. Lt. Benjamin Foulois flew it alone in 1910 at Fort Sam Houston, San Antonio Texas and later flew with wheels instead of skids only. A wheeled landing gear was generalized at that time. In October 1911, this model was sent for exhibition at the Smithonian, and still is there today.

Wright Model A (1909)

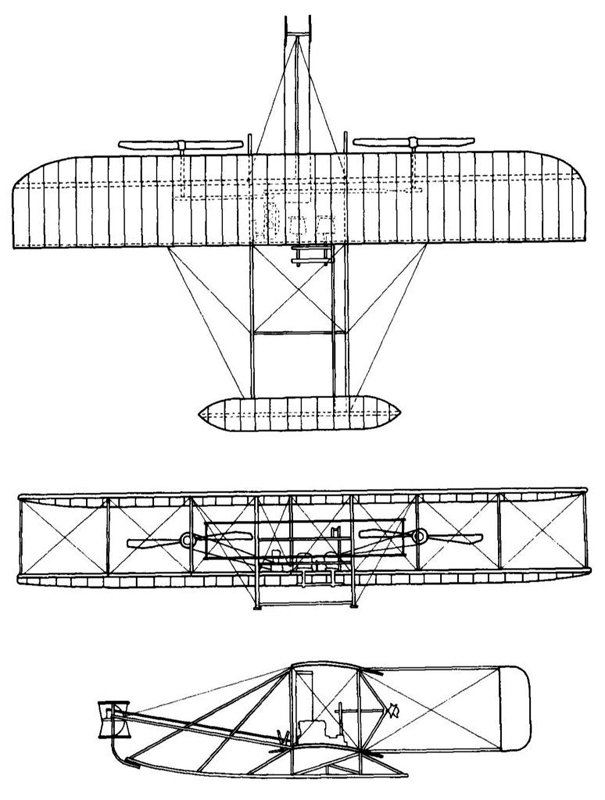

Blueprint Model A – Credits wright-brothers.com

The Model became the world’s first mass-production airplane, large enough to comprise many variants from 1907 to 1909and based on the 1905 Flyer III. Design changes were the length, weight and an improved engine. Crucially these changes allowed a two-seat configuration on the leading edge of the wing. It also had two new control systems with three separate levers for wing warping, elevator, and rudder. Wilbur was not happy with these and later devised a Model A replace the original 3-lever system shown in France and later at Fort Myer with gradual improvements. These changes produced a European variant with a “Wilbur” control system, and “Orville.” in the US, which became a purchase option. Whatever the case both featured the same two levers between the seats, for the elevator, warping the wings, tilting the rudder. This system was located such as to allow both pilots to relay or switch control, it was also usable for training.

The Model A was showcased by Orville on 8 Aug 1908 in France and later to Italy (Wilbur) in 1909. Another flown at Governor’s Island in New York (October of 1909) as part of the Hudson-Fulton Celebrations, and at Fort Myer in September 1908. Late 1909 and early 1910, the Model A eveolved with new fixed horizontal stabilizers to the tail, a movable elevator and outriggers holding the tail shaped as a rectangular framework while the front elevator/canard disappeared but this at the end of 1910, it was superseded by the Model B. About 7-8 prototypes of this type were therefore manufactured.

Wilbur was teaching the first generation of U.S. military pilots at College Park, Maryland fall 1909, when he attached a horizontal surface ahead of the twin rudders of the Military Flyer while Orville, made about the the same modification while in Germany and this modification went on to resemble the system Curtiss and Farman used. Spring of 1910 in Montgomery, Alabama students flew the “Model AB” which had elevators, front and back. This was a transitional design, “convertible” in a sense, tested extensively by Hoxsey. The brothers would also add wheels to the Model AB, and at the end of 1910 concluded the elevator worked best when placed at the back and the wheels were definitely better than a catapult. It was a forerunner for the Model B showcased at the Belmont Aviation Tournament in New York.

Specifications

Dimensions: 41 ft (8.5 x 12,3m ) Lenght – wingspan

Weight: 800 lb (362.9 kg) empty

Propulsion: 4 cylinder engine, 31 hp at 1425 rpm, average speed 37 mph (60 kph)

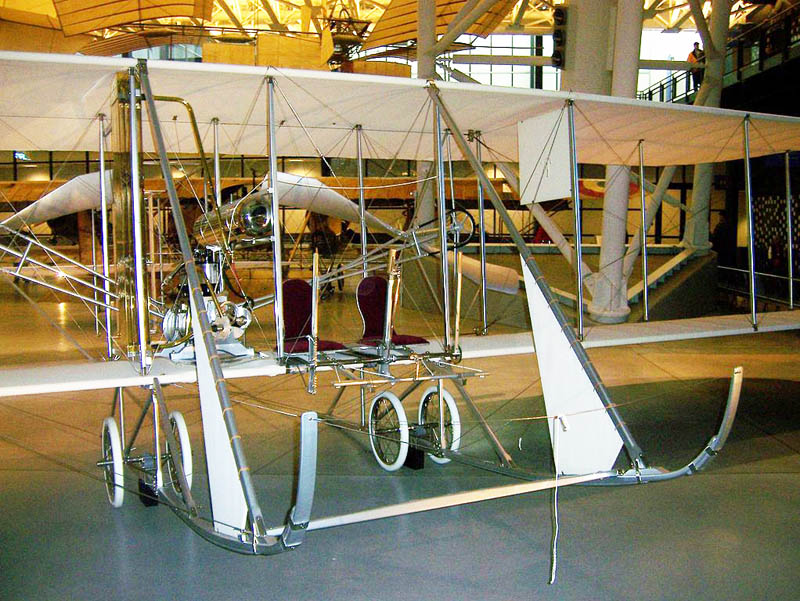

Wright Model B (1910)

The “headless Wright” because it lacked the familiar canard of the previous series, the Model B became nevertheless the most refined and successful aircraft of the serie, produced until 1914, four leaving their factory monthly, shipped globally. This model was a compromise between the late Model A, and the AB prototype with rear outriggers extended allowing the rudder and elevator to be placed further from the wing. The wheeltrain was also mixed with skids but performances and reliability, agility was a net improvement over the previous one. Despite its popularity however it did not re-establish The Wrights Brothers technological leadership, the Model B being tail-heavy and prone to stall draggy because of the numerous wires and it became obsolete in 1912. This Model B however turned to be en exceptional record holder, making a large number of “firsts” like air freight, bombing, in-flight radio message, parachute jump, naval launch, aerial weaponry among others.

The “headless Wright” because it lacked the familiar canard of the previous series, the Model B became nevertheless the most refined and successful aircraft of the serie, produced until 1914, four leaving their factory monthly, shipped globally. This model was a compromise between the late Model A, and the AB prototype with rear outriggers extended allowing the rudder and elevator to be placed further from the wing. The wheeltrain was also mixed with skids but performances and reliability, agility was a net improvement over the previous one. Despite its popularity however it did not re-establish The Wrights Brothers technological leadership, the Model B being tail-heavy and prone to stall draggy because of the numerous wires and it became obsolete in 1912. This Model B however turned to be en exceptional record holder, making a large number of “firsts” like air freight, bombing, in-flight radio message, parachute jump, naval launch, aerial weaponry among others.

So this model B was extensively tested by the Army but apparently never went into regular units. One has survived in the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and at the Air Force in Dayton, Ohio.

Burgess Model F replica preserved at Hill Aerospace Museum, Model B license-built variant.

Wright Model B reproduction in Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center.

Wright Model R (1910)

The famous “Baby Wright”, also called the “Roadster” was a smaller one-place biplane first designed for British sportsman and pilot Alec Ogilvie, especially for the Gordon Bennett air race at Belmont Park, NY. It flow in October 1910, placed third with a top speed of 55 mph (89 kph), while another one Model R was introduced at the 1910 Gordon Bennett air race, propelled by a V-8 engine. This “Baby Grand” was flown by Orville at 70 mph (113 kph) in October 1910 but pilot Walter Brookins had an engine failure during the competition and his plane crashed.

The Wright model EX for “exhibition” was a small and very fast derivative of the 1910 Model R “Baby Wright.” The gap between the wings was reduced, shorter wires creating less drag to reach up to 55 mph (89 kph) with a 30 hp engine. Later controls were modified for faster responses and the landing gear also to reduced drag. One of the EX was the “Vin Fiz” created for Cal Rodgers to fly across America, sponsored by Armour Meats which then produced the beverage Vin Fiz. The historical trip started on 17 September 1911 at Sheepshead Bay (Long Island, NY) to land in Pasadena, California on 5 Nov 1911 and it was seen in many exhibitions until 1914, until joining apparently the Smithsonian in 1934. These models were fast but at that time this did not interested the army which was focus on range ad altitude.

Later on, in 1913 the EX was derived into the Model E a version that could be carried and assembled in 12 minutes by a small crew for exhibitions. Its only modification was 7-foot pusher propeller and larger tires plus 32-foot span. Its weight was only about 730 pounds and it was tested for the 4 and 6-cylinder Wright motors. Late 1913 a model flew with an “automatic stabilizer” and won the Collier Trophy of the Aero Club of America.

Wright Model C (1911)

This was as requested by the Army a “weight-carrying” Model B capable of lifting as much as 450 lbs, climbing at 200 feet per minute with an autonomy of four hours. Its heart was a six-cylinder using carburetors, twin Zeniths for the first time for each set of cylinders, as well as water-cooled heads on the cylinders and optional muffler. This model B only differed externally by the its large vertical rectangular blinkers while the wings a bit shorter and flatter and rudder slightly taller. This was also a true dual control, perfect for training.

A few model C were delivered with the old Wright 4-cylinder. The new engine made these planes however somewhat difficult to handle and several pilots died in crashes (as well as many Curtiss pushers) so much so the army decided to ban pushers in late 1914 in favor of tractor planes only. This showed the way for the Wright brothers for their next iteration. The model D was built in parallel for an Army contract, it was derived from the Model R Roadster but fitted with 6-cylinder 60 hp engine and could fly at 66.9 mph, climb at 525 feet per minute. However tests showed it extreme landing speed and the Army canceled further orders. The model CH also developed in parallel was a floatplane version created in early 1913. It used two twin pontoons under the skid but after trials it was swapped for one single large float/pontoon completed by smaller ones under each wingtip and the tail (so four in all). It was tested but never ordered.

Wright Model C

Specifications (Model C)

Dimensions Length 29.8 ft (9.1 m) x 38 ft (11.6 m) wingspan, 440 sq ft (40.8 sq. m) wing area

Weight: Empty 920 lbs (417 kg)

Propulsion: 6 cyl. 50/75 hp @1560 rpm, two contra-rotating props, 8.5 ft, 55 mph (86 kph) average speed

Wright Model G (1913)

Wright Co. chief engineer, Grover Loening, designed a seaplane with a 38-foot span which was 28 feet in length and weighed more than 1,200 pounds. Its fuselage was a 18-foot boat-like hull and an enclosed cockpit, the first ever created by the company. It was a twin-propeller pusher but later models had the engine moved in front, the pilot seated beneath the wings. The 6-60 engine allowed the aircraft to reach 60 mph. Later modifications included dihedral wings, non-flexing elevator above the rudder, and also an optional wheel to better handle the pitch and roll.

Wright Model H & K (1914-15)

Two 1914 prototypes quite similar to the Model F but with a streamlined fuselage better blended with the tail. The HS was a short wingspan version at 9.75 meters or 32 feets, to lower the drag and improved the climb. The H on the other hand could carry more payload, over 1000 lbs (454 kg). Both were the last “pushers” double rudder models of the manufacturer. The Army was never interested. The Wright Model K born in 1915 was a seaplane specially tailored for the needs of the US Navy, as a tractor airplane as required, with both Wright “bent-end” propellers forward and ailerons for the first time. The plane rested on two pontoons, but the Navy declined any order for it.

Wright Model L (1916)

First and last “second generation plane” from the company, the Model L was a single-seat tractor biplane with standard control surfaces which seems familiar to us in its general appearance. The Wright brothers idea was to make it a high speed military reconnaissance aircraft capable of reaching 80 mph (129 kph). Critics would later say that greater speeds could have been achieved if the Brothers would had deleted its oversized tail from the Model K. Its lack of streamlining and general drag made it in the end more sluggish that its competitors and this Model L failed to secure any orders by the military. The few produced were tested only. The Wright Company was acquired afterwards, but Orville Wright was retained as a consultant. In 1916, the brothers acquired the Crane-Simplex Automobile Company and the Glenn L. Martin Aircraft Company which merge to form the Wright-Martin Aircraft Corporation.

Specifications

Dimensions: 29 ft (8.8 m) wingspan, 24.2 ft (7.4 m) Length, 360 sq ft (33.4 sq. m) wing area

Weight: 850 lbs (386 kg) empty

Propulsion: 6 cyl. engine, 75 hp @1400/1560 rpm, 8 ft propeller, 80 mph (129 kph) top speed

Vought

Vought

The story of Vought

Portrayal of Chance Vought circa 1915

The story of Vought, which still produce aircrafts under the Northrop Grumman umbrella, started with American designer Chauncey Milton “Chance” Vought (born February 26, 1890 in Long Island, New York). This American aviation pioneer and engineer co-founded the Lewis and Vought Corporation with Birdseye Lewis. The company was founded in 1917, succeeded by Chance Vought Corporation in 1922 when Lewis retired. From 1919 the business started operations in Astoria, New York by 1919, then at Long Island. Vought designed until 1930 a large array of fighters, seaplanes, training planes, surveillance planes for both the USAF and US Navy own Air Service. In 1922 when the Vought VE-7 made the world’s first takeoff from the USS Langley, the first American aircraft carrier (converted). Later planes strongly associated with Navy would be the VE-11 and Vought O2U Corsair… But in WW1 his most famous model by far was the VE-7, and its “bluebird” version in 1918 won the Army competition for advanced training machines.

The story of Vought, which still produce aircrafts under the Northrop Grumman umbrella, started with American designer Chauncey Milton “Chance” Vought (born February 26, 1890 in Long Island, New York). This American aviation pioneer and engineer co-founded the Lewis and Vought Corporation with Birdseye Lewis. The company was founded in 1917, succeeded by Chance Vought Corporation in 1922 when Lewis retired. From 1919 the business started operations in Astoria, New York by 1919, then at Long Island. Vought designed until 1930 a large array of fighters, seaplanes, training planes, surveillance planes for both the USAF and US Navy own Air Service. In 1922 when the Vought VE-7 made the world’s first takeoff from the USS Langley, the first American aircraft carrier (converted). Later planes strongly associated with Navy would be the VE-11 and Vought O2U Corsair… But in WW1 his most famous model by far was the VE-7, and its “bluebird” version in 1918 won the Army competition for advanced training machines.

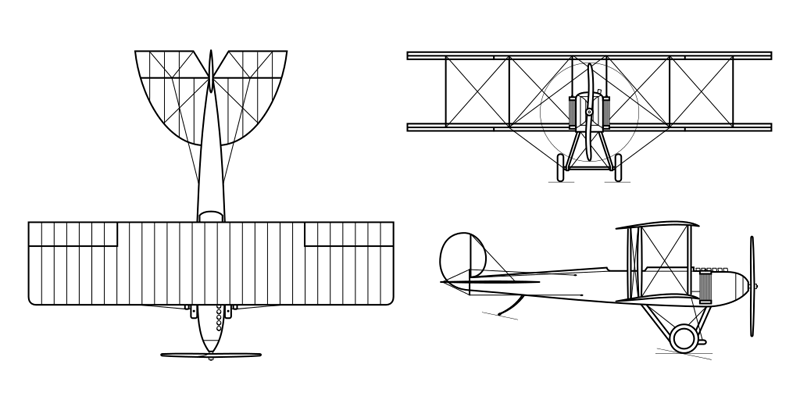

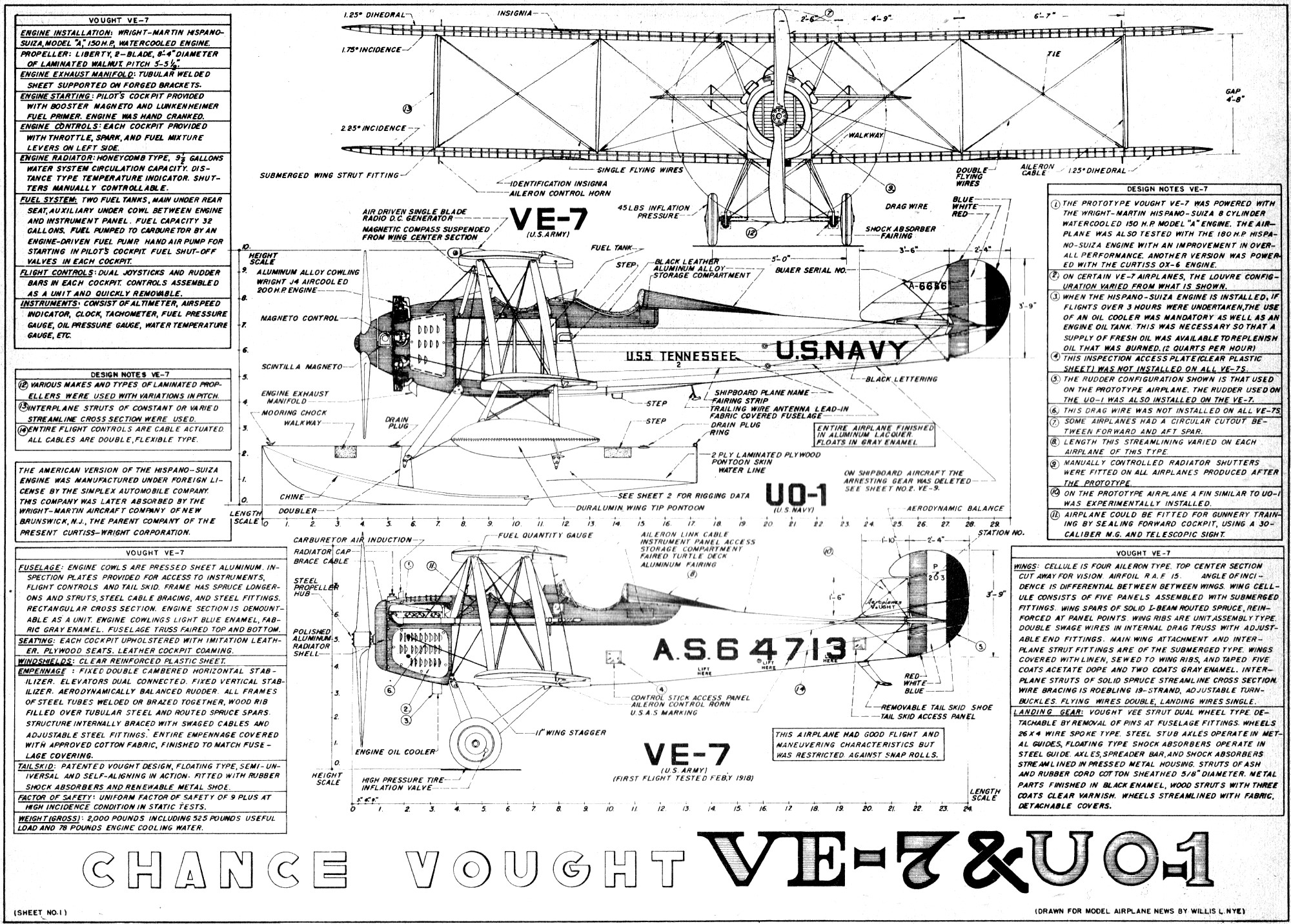

Vought VE-7 (1917)

As the company was formed a few months after the U.S. entered World War I, a trainer was quickly designed, modelled after European designs and propelled by the same liquid-cooled Wright Hispano Suiza (SPAD’s engines). Vought made it strong enough to accomodate the engine, therefore the trainer became as fast as the best fighters of the time. So much so that the Army soon ordered 1,000 VE-7 derivatives, the VE-8s, a contract cancelled when the hostilities ended. Meanwhile the Navy has been equally impressed and therefore received their own serial VE-7 in May 1920. Orders followed in such numbers that Vought passed most of it to the Naval Aircraft Factory, 128 VE-7s being built total.

Production features

The Vought VE-7 was a two-seat tractor biplane and advanced trainer answering to a government request for advanced training (fighter pilots). The first serie were built for tests, and first flew on February 11, 1918. The Signal Corps accepted it and ordered 14 VE-7 airplanes by May 1918 and the the Navy soon followed with 60 more, some later converted as VE-7SF for aircraft carrier landing tests in 1922. First tests were performed at Hazelhurst Field after which they were sent to the Airplane Engineering Department of McCook Field (Dayton) in Ohio, for official tests for the officials, and received all but praises for its show. In March of 1918, the “bluebird” took part in an open government competition, winning largely over seven competitors and this was followed by more orders both for the official Test Board and for training. The official report also stated that the plane was fit for both primary and advanced training, a sound, cost-saving solution.

This Vought model was warmly recommended to authorities by Lt. Col. Virginius E. Clark, Brig. Gen. Billy Mitchell stating it was overall better than the Spad, Nieuport, SE-5 while Entente delegates from various European Aviation Missions also praised it. The Bureau of Aircraft a conversion as a fighter and two designs followed, the VE-7A (short-range) and VE-7B (long-range) both with a single machine gun mounted behind the aft cockpit, but at the same time for standardization on the battlefield, it was decided to keep European fighters in service, therefore condemning the VE-7 as an advanced trainer only. Extensively tested, Vought’s biplane became overnight the most uniform design with equal very high standards for sturdiness, reliability, performances, agility, flight characteristics, and even maintenance. To add to this, the “Bluebird” after the competition blue-rimmed plane was as good looking as it was well-finished, with standards close to that of the best automotive luxury brands. Tests also made history in a sense they were the most thorough yet, as devised by Professor Klemin, the procedure of which was followed for the whole interwar and refined afterwards.

In May 1918, the Signal Corps ordered 14 VE-7’s with the plans and rights to build the aircraft, allowing the Aircraft Division at McCook Field to build two more. The government also granted it to the low bidders. Indeed by late October 1918, General William L. Kenly, of the fresh Department of Military Aeronautics placed an order for 1,000 VE-7’s to three companies, McCook, the Springfield Aircraft Corporation and Springfield Massachusetts, each receiving a contract for a total of 500, the remainder places after the Sturtevant Aeroplane Company based in Jamaica Plains, Massachusetts, and only four days afterwards a recommendation for 3,000 was added, but the Contract Cancellation came out only two weeks later as the war was over. Therefore what could have become the best fighter/trainer of the war never saw action in Europe. The few built however were used extensively in the early 1920s, making history as they went.

VE-7 modelling blueprint

Postwar variants

The VE-7S was converted as a single-seater with a modified front cockpit to support a single caliber 30 (7.62 mm) Vickers machine gun on the left side and synchronized. A few derived VE-7SF were given inflatable bags to help keep the plane afloat when ditched at sea. The VE-8 first flew in July 1919 with a 340hp Wright-Hispano H while the overall dimensions were slightly reduced while the wing area was widened, and the faired cabane made shorter. Most importantly it was given two Vickers guns. Only the two prototypes were ever completed but test shown these planes were overweight, had stiff controls, poor stability and overall bad performance. The drawings were revised for the VE-9 variant designed for the Navy and delivered on 24 June 1922. Vought started again with the basic VE-7 design, but much improved, especially around the fuel distribution. 21 were completed and put in service, among which four were unarmed observation seaplanes carried to test battleship catapults.

Other variants (Postwar)

VE-7G (1921): 1 converted (Marines) and 23 converted for the U.S. Navy

VE-7GF (1921): 1 converted

VE-7H (1924): 9 produced for the U.S. Navy

VE-7SH (1925): 1 7SF converted as floatplane

VE-9H (1927): 4 carried observation seaplanes by U.S. Navy battleships. The 9W was canceled.

Specifications VE-7

Dimensions 7.45 x10.47 x2.63 m (24 x34 ft x8 ft 7.5 in) Wing area: 284.5 ft² (26.43 m²)

Weight: Empty 1,392 lb (631 kg), loaded 1,937 lb (879 kg)

Engine: Wright-Hispano E-3 180 hp (134 kW), Top speed: 106 mph (171 km/h)

Range: 290 mi (467 km), Ceiling: 15,000 ft (4,600 m), Climb: 738 ft/min (225 m/min)

Armament: Vickers .30 in (7.62 mm) synchronized MG

Read More/Src:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aeromarine

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wright_brothers

Aeromarine

Aeromarine M1

Aeromarine 700

Aeromarine 40

Aeromarine 39

Aerodigest

Aeromarine planes

Aeromarine corp

Google books – Flying Magasine – Popular aviation 1932

On airandspace.si

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vought_VE-7

VE-7 product

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Burgess_Model_H

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Curtiss_Model_B

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas-Morse_Aircraft

http://www.ctie.monash.edu.au/hargrave/dunne.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Burgess_Company

http://www.aviastar.org/air/usa/burgess_ht-2.php

http://www.massaerohistory.org/Burgess.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glenn_L._Martin_Company

https://www.mdairmuseum.org/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Martin_MB-1

https://www.militaryfactory.com/aircraft/detail.asp?aircraft_id=185

http://www.joebaugher.com/usaf_bombers/mb1.html

http://www.biplane.link/martin-mb-1.htm

http://flyingmachines.ru/Site2/Crafts/Craft29845.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Curtiss_Aeroplane_and_Motor_Company

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Standard_Aircraft_Corporation

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Standard_E-1

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Standard_J

LUSAC-11