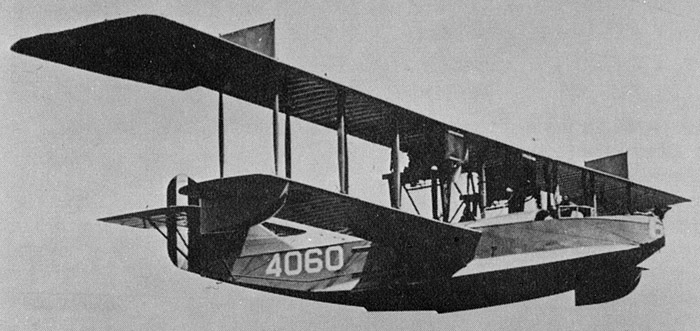

The Felixstowe F.2 was a 1917 British flying boatdesigned and developed by Lt. Commander John Cyril Porte at the naval air station of the same name during the First World War. This ws a start of a famous lineage, adapting a larger version of the initial F.1 hull design, an hybrid of Curtiss H-12 flying boat with a new hull with superior water contacting attributes. It became an essential innovation for future flying boat designs thereafter. The Felixstowe lineage went all the way up to the F.5 (las production variant in 1918) with massive number buil and used by the entente powers for ASW patrol. This was the WWI equivalent to the Consolidated Catalina, as ubiquitous and useful.

Development

About J.C Porte

John Cyril Porte (“Door” in French) CMG, FRAeS (26 Feb. 1884 – 22 Oct. 1919) was a British flying boat pioneer, born in Bandon, County Cork, Ireland. His father was a professor and notable of the Dublin society before the family moved to Britain. Porte joined the Royal Navy in 1898 (age 14) as cadet on HMS Britannia, midshipman on HMS Pilot by September 1902, then HMS Royal Oak and as lieutenant in 1905, transferred to the Submarine Service in 1906, trained on HMS Thames and HMS Forth, then in command of HMS B3 from January 1908, and worked under Murray Sueter, a pioneer of submarines, airships and aeroplanes, who encouraged Porte to join this latter branch. So the same yet he designed a glider with Lt. Wilfred Baley Pirie, flying on 17 August 190 at Portsdown Hill, Portsmouth from Wright style rails, an event featured on “Flight magazine”. This staggered wing biplane had two pilots, one on the rudder and wing warping, the other on the lift. They were attached to the submarine depot at Haslar.

John Cyril Porte (“Door” in French) CMG, FRAeS (26 Feb. 1884 – 22 Oct. 1919) was a British flying boat pioneer, born in Bandon, County Cork, Ireland. His father was a professor and notable of the Dublin society before the family moved to Britain. Porte joined the Royal Navy in 1898 (age 14) as cadet on HMS Britannia, midshipman on HMS Pilot by September 1902, then HMS Royal Oak and as lieutenant in 1905, transferred to the Submarine Service in 1906, trained on HMS Thames and HMS Forth, then in command of HMS B3 from January 1908, and worked under Murray Sueter, a pioneer of submarines, airships and aeroplanes, who encouraged Porte to join this latter branch. So the same yet he designed a glider with Lt. Wilfred Baley Pirie, flying on 17 August 190 at Portsdown Hill, Portsmouth from Wright style rails, an event featured on “Flight magazine”. This staggered wing biplane had two pilots, one on the rudder and wing warping, the other on the lift. They were attached to the submarine depot at Haslar.

In 1910, he joined HMS Mercury (tender to Holland-class subs) and captain of HMS C38 from 31 March 1910. He learnt to fly by the end of 1910 on a Santos-Dumont Demoiselle he built in his spare time. He served on HMS President in London, for a flying course to gain his certificate, the 548th. He worked with Aero Club de France from 28 July 1911 on a Deperdussin monoplane at Reims airfield and competed in the Daily Mail Circuit of Britain from Brooklands with a 60hp Anzani Deperdussin (accident shortly after takeoff) but proved to be a natural pilot. Her became technical advisor at Deperdussin and test pilot, and became the managing director of the British Deperdussin Company from April 1912 with D. Lawrence Santoni (Savoia). This was the British factory for the manufacture of a foreign aircraft and Porte became designer, soon joined to Frederick Koolhoven from France as chief engineer in mid-1912. Porte invested all in the company.

While trying to develop his business in the US, he met and also worked with Glenn Curtiss on a flying boat “America”, intended to cross the Atlantic for a £10,000 prize by the Daily Mail. But in 1914 he returned to Britain and enlisted again in the Royal Navy, quickly becoming commander of the naval air station, Felixstowe, forever associated with him. There, he recommended the purchase from Curtiss of an improved version of the “America”. This type was the Curtiss H-4, of which the RNAS receiving two “America” prototypes and ordered the whole H4 production, 62 flying boats, mostly sent to Felixstowe.

Porte-Hallett’s Curtiss “America”

Porte and “America”

Porte died suddenly in Brighton, East Sussex of pulmonary tuberculosis on 22 October 1919 (age 35), overworked in WWI, he gave everything in the development of British seaplanes and was recognized later by aviation authors (it was on his epitaph) as the inventor of the British flying boats. Like Mitchell (at Supermarine) the man was gifted but absolute, burning himself for the success of the job, and was showered (posthumously) with honours, like the DSM by Josephus Daniels, Secretary of the Navy, and in 1922 he entered the Royal Commission on Awards to Inventors. He formed the Short Brothers that would later among others, create the WW2 legendary Sunderland helping to win the battle of the Atlantic.

The Felixstowe F.1

The Curtiss H-4 was however a model with issues, as it was found underpowered and with a hull too weak for sustained operations. It was found having poor handling characteristics also when afloat, or having an hard time taking off. One test pilot, Major Theodore Douglas Hallam was not impressed, stating these were:

comic machines, weighing well under two tons; with two comic engines giving, when they functioned, 180 horsepower; and comic control, being nose heavy with engines on and tail heavy in a glide.”

To try to resolve these issues in 1915, Porte experimented modifications on four H-4s with all different hull underbellies. This led him to design a brand new 36-foot-long (11 m) hull. It still borrowed the wings and tail of the H-4, serial 3580. The engines were replaced by beefier 150 hp (112 kW) Hispano-Suiza 8 engines. The final result was called the Felixstowe F.1. It was no longer the original lightweight boat-like structure Curtiss designed but a much sturdier wooden box-girder mirroring contemporary land planes instead. It was attached a single-step planing bottom, plus side sponsons and crucially, it was given two steps, and so proved to solve the much anticipated take off problem, while being steady and safe for its and landing characteristics as well as being more seaworthy.

Modifications Porte on new hull were prepared by with his Chief Technical Officer John Douglas Rennie, and this initial new single-step hull was simply known as “the Porte I”. That Porte I hull used wings and tail unit of the H-4 but with Hispano-Suiza 8 engines and the trials of the F.1 led to these famous two further steps, as well as a deeper V-shape to improve performances, then a new hull design incorporated these aspects, but more streamlined, as the “Porte II” adapted to the larger Curtiss H-12 flying boat, forefather of the Felixstowe F.2. So overall, four F.1 were built, the last two testing more hull shapes, only retired by January 1919. They were used for instruction at Felixstowe, but never were operational. They were retired, worn out, in January 1919.

Curtiss H.16

Among differences with the F.2, they were much smaller and had a specific rounded tail rudder. They were also sesquiplanes like the Curtiss, with a much larger upper wing, shorter lower wing ending with floats underneath, and connected on top by six pairs of struts, with the two Hispano engines suspended below the central hull section. The F.1 had a crew of 4, for an overall length of 36 ft (10.97 m), an upper wingspan of 72 ft (22 m) and a total wing area of 842 sq ft (78.2 m2). The V8, 150 hp (110 kW) Hispano engine gave an approx. top speed of 130 kph.

About Felixstowe

F2Bs at Felixstowe, ready to be launched

Felixstowe Flying Boats

Felxitowe Porte Baby combination with a Bristol Scout C at Felixstowe, first composite aircraft

Felixstowes are named after the RNAS station at Felixstowe, where new types of flying-boat were developed during WW1. Squadron Leader John Porte became head of the station in 1915 and induced the Admiralty to acquire American flying-boats designed by Glenn Curtiss. These had originally been constructed for a transatlantic service but were adapted for operational use at Felixstowe, thus combining the best of British and American design. The modified aircraft had a new hull designed by Porte with the wings and tail of the original Curtiss and was designated the Felixstowe F1.

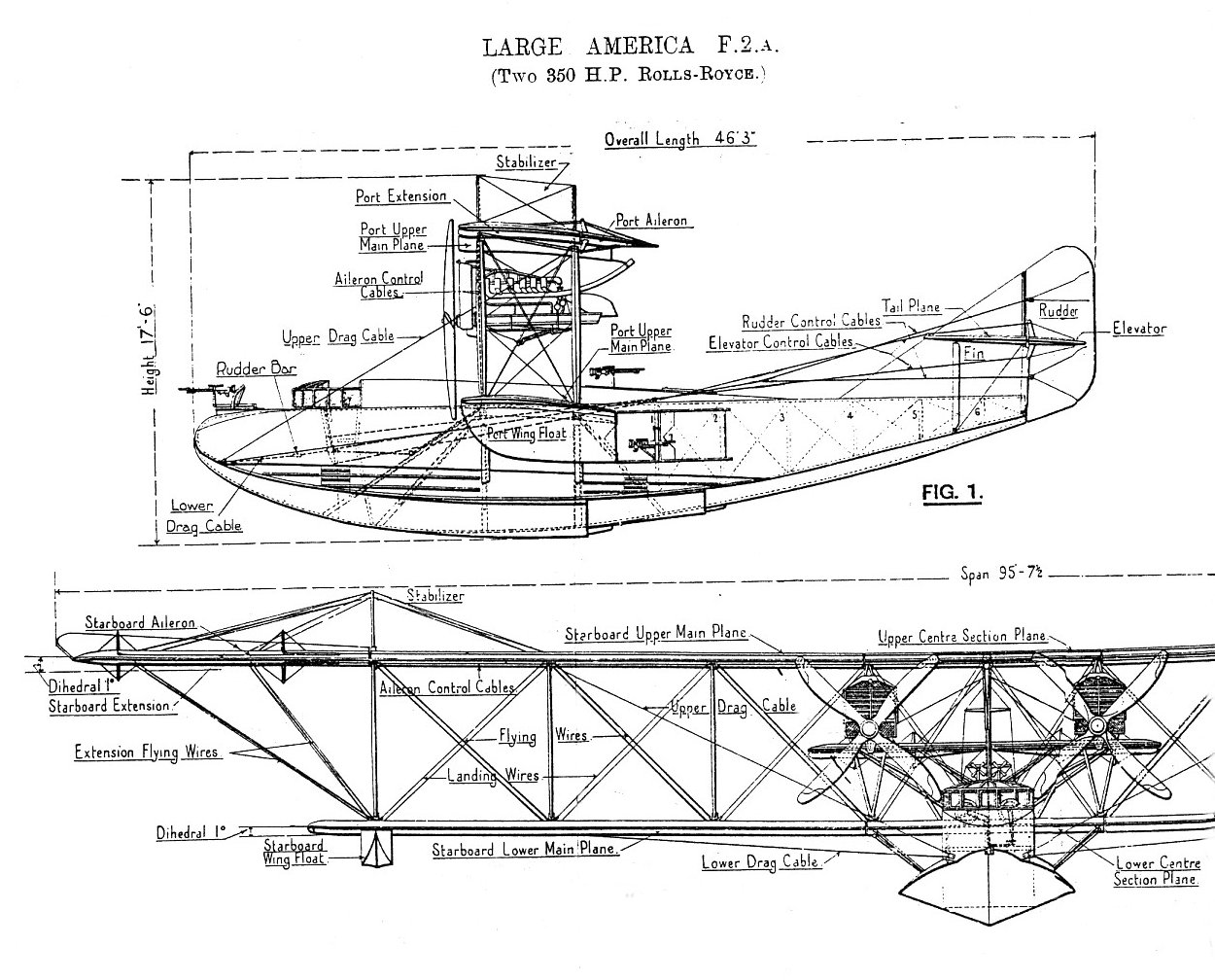

The range and load capacity of the F1 was found inadequate for North Sea patrols and Curtiss was asked to develop a larger aircraft known as the Curtiss H8 or Large America. The hull was again found to be unsuitable for North Sea conditions and was redesigned by Porte, the engines being replaced with more powerful 250hp Rolls-Royce Eagles. This became the F2 and, after a few more modifications, the F2A which was a popular and successful aircraft and remained in use until the end of the war, about 100 being built.

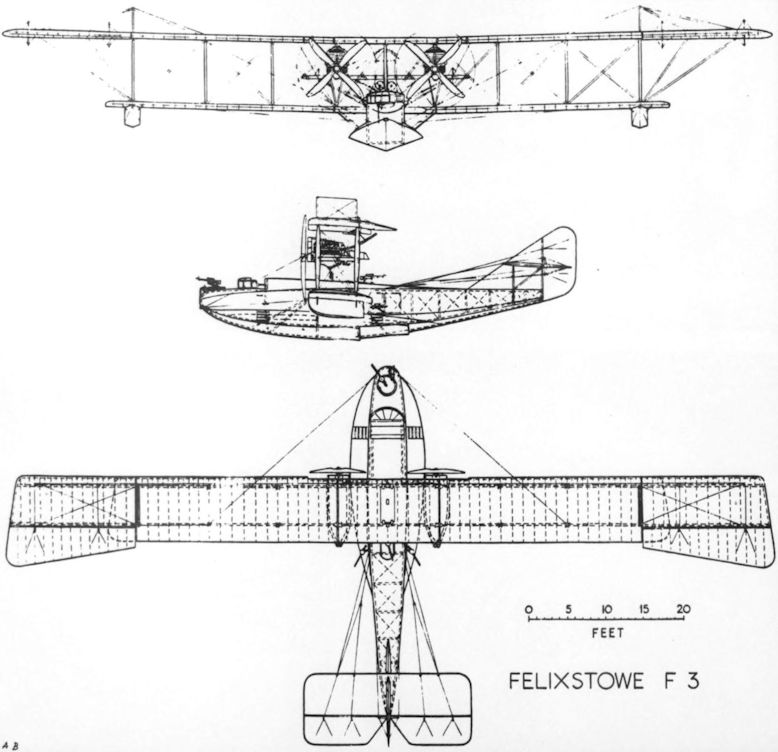

Felixstowe F.3 prototype

In February 1917 the prototype of a new flying-boat developed from the F2A appeared, designated the F3. It was intended to carry a much heavier load, but the only significant modifications were slightly extended wings and fuselage. The same engines were retained, and consequently the F3 was slower and less manoeuvrable than its predecessor, rendering it less able to engage enemy aircraft and less popular with crews. More F3s were ordered than F2As because of the F3’s 100% greater bomb load, but only about 100 were built, some of these being converted to F5s before completion. Some F3s were used by the RAF in the Mediterranean.

The prototype Felixstowe F5 first appeared in early 1918, with improvements to the hull and wings derived from experience with the former marques. Performance was an improvement upon the F3 but in the interests of economy it was decided to produce only the new hull and otherwise retain as many F3 components as possible. Eventual performance of production aircraft was consequently worse than the F3. The F5 was too late to see operational service but became the RAF’s standard post-war flying-boat until replaced by the Supermarine Southampton in 1925. F5s were also produced for the US Naval Flying Corps by Curtiss in the US, an unusual situation in that they were building foreign aircraft originally designed by themselves. The F5 was also the US Navy’s standard flying boat until the late 20s. src: https://www.willhiggs.co.uk/ archived.

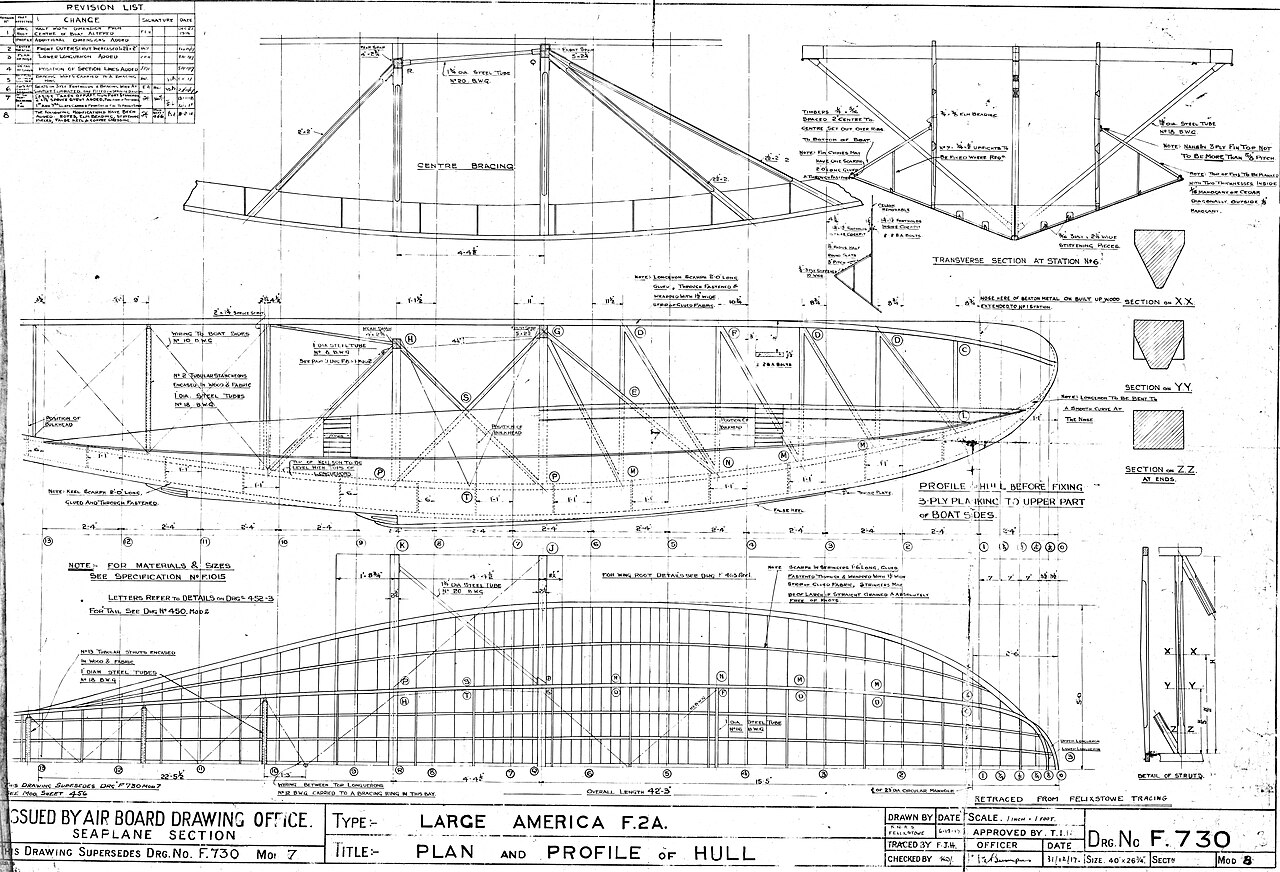

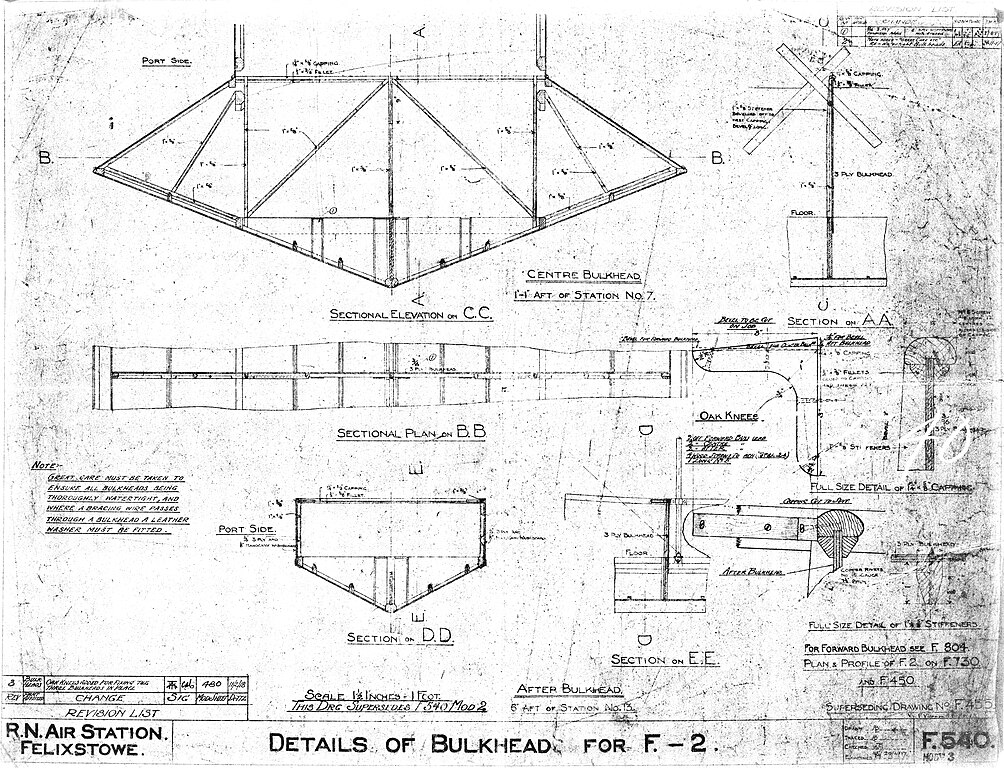

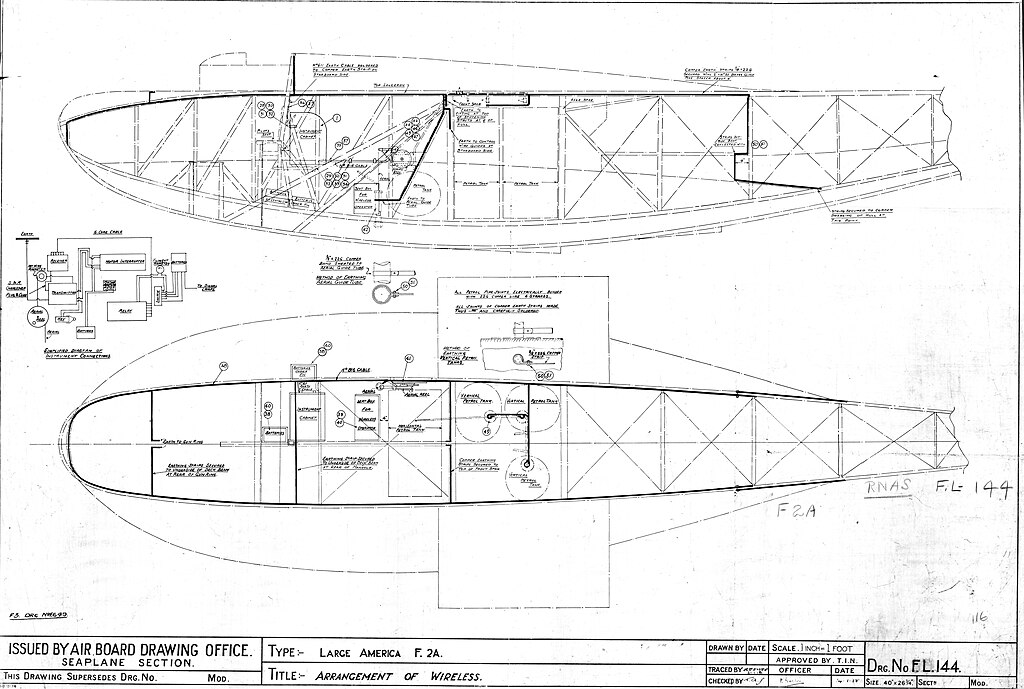

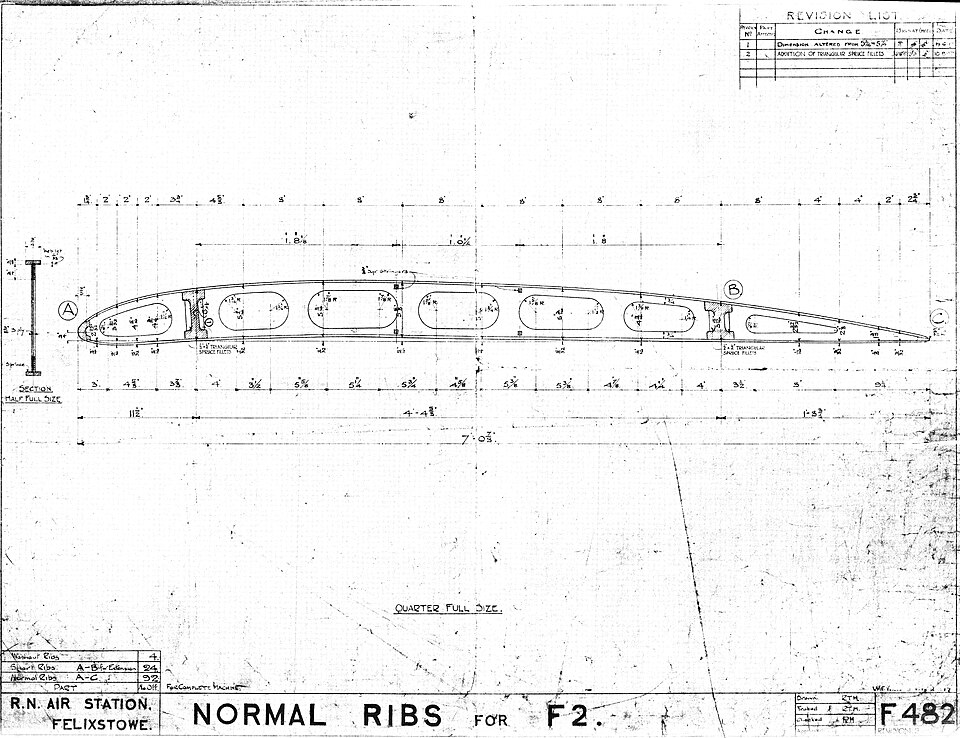

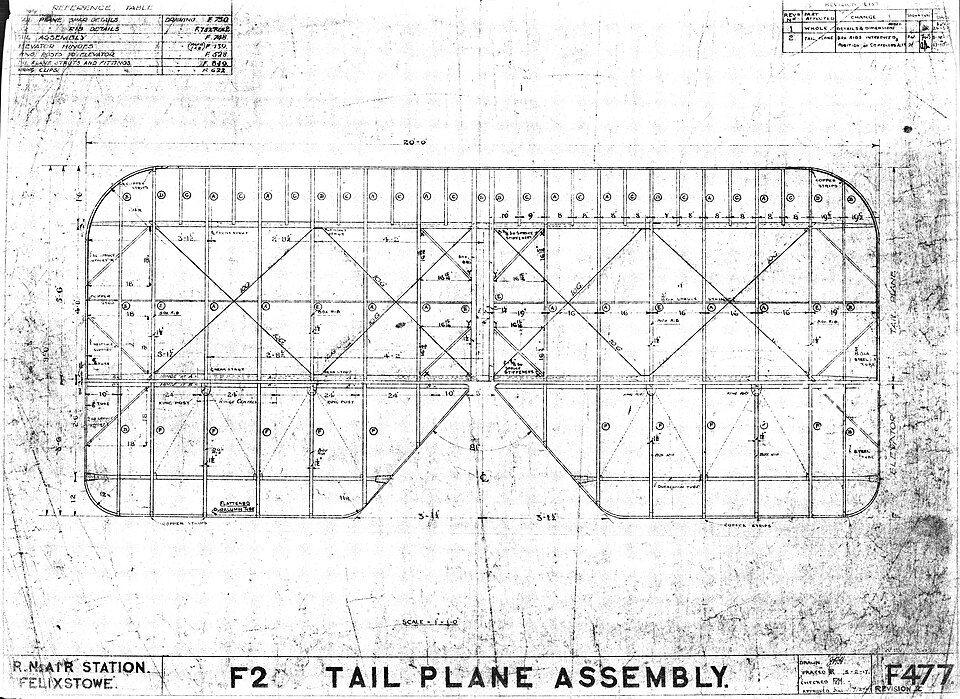

Design of the Felixstowe F.2

Porte designed a similar hull as the F.1, but for the larger and more capable Curtiss H-12 flying boat. This latter model shared the shortcomings of the H.4, the same weak hull and poor water handling. With this new double-stepped, stronger, larger Porte II hull, and the wings of the H-12, he added a new tailored tail. Next, the original Curtiss V-X-X engines by two Rolls-Royce Eagle engines. This became the Felixstowe F.2, making its maiden flight on July 1916. It was found greatly superior to the Curtiss. The F.2 entered production as Felixstowe F.2A with an enclosed cabin, two MG defensive post and racks to attach underwings bombs, as a patrol aircraft. A total of 100 F.2A, then 70 F.2B and two F.2C were completed by the end of the World War I. They all served at Felixstowe Naval Station.

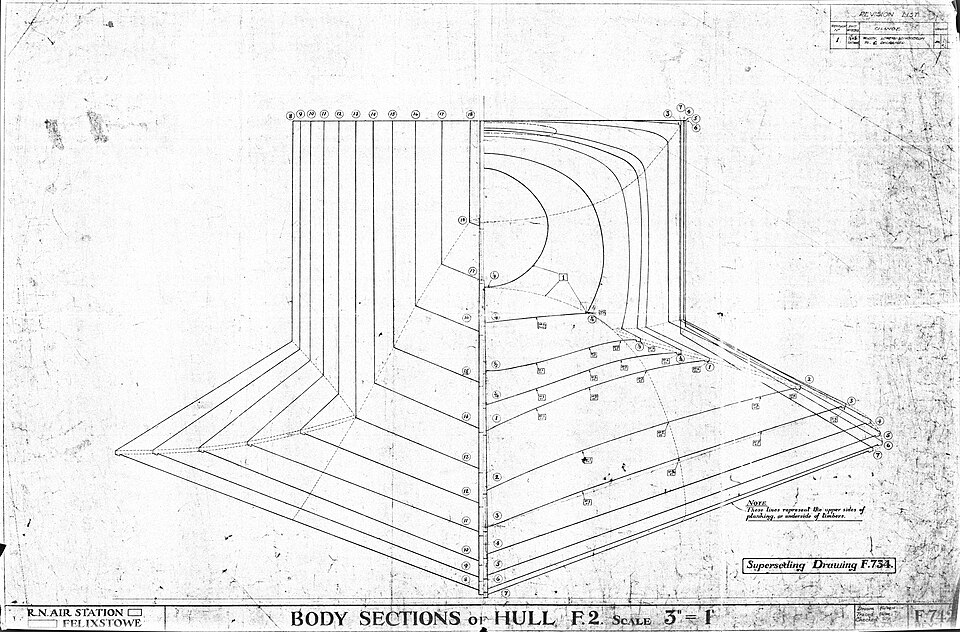

The most striking aspect of the design was the peculiar shape of the fuselage. It was composed of a squat-sectioned fuselage on top, with a lower floating hull that was looking like blisters. Seen from the top, and contrasted with the relatively long and narrow wings, it made the fuselage bulky, whereas in reality these bulges did not represent such extra weight. The secret sauce Porte put into this hull, especially compared to the Curtiss, was that famous twin step underbelly to help it take off, and generally solve the “unsticking” problem of flying boats at the time. This fuselage comprised from prow to stern, a rounded nose with berthing/anchoring apparatus, a forward Gun/observer position, a two seat side-bu-side cockpit for the pilot and co-pilot/navigator, and an amidship MG gunner.

The F.2A weighted 4,980 kg(10979 lb) at take off, but “only” weighted 3,424 kg (7549 lb) empty. The Wingspan was double that of the fuselage length at 29.15 m (96 ft 8 in), contrasted to 14.10 m (46 ft 3 in) for an height of 5.33 m (18 ft 6 in) and a wing area of 105.26 m2 (1133.01 sq ft). The narrow wings or high aspect ratio wings (ratio of length vs girth(span/chord)) are more efficient and produce less drag, reduced consumption, thus enabling extra range. In fact they are now proven 8-12% more efficient, albeit this was not known at the time. The ratios were based on simpler calculation of wing loading and the area based rather on a sesquiplane configuration, on which the lower wings had a more rational size, but a large upper wing compensated for a possible extra weight. Which was the case as Porte considerably reinforced the fuselage’s strength.

The two wings were joined by a series of wooden streamlined struts, six pairs in all, with a 7th pair on the axis between the fuselage and upper wing, the only main attachment, which was considerably reinforced. The engines were attached by a series of V and X struts, with inner legs anchored to the fuselage. The engine nacelles top was anchored underwing. These were tractor engines. The vertical tail was triangular, like the Curtiss H12 and 16, and the horizontal stabilizers essentially squat.

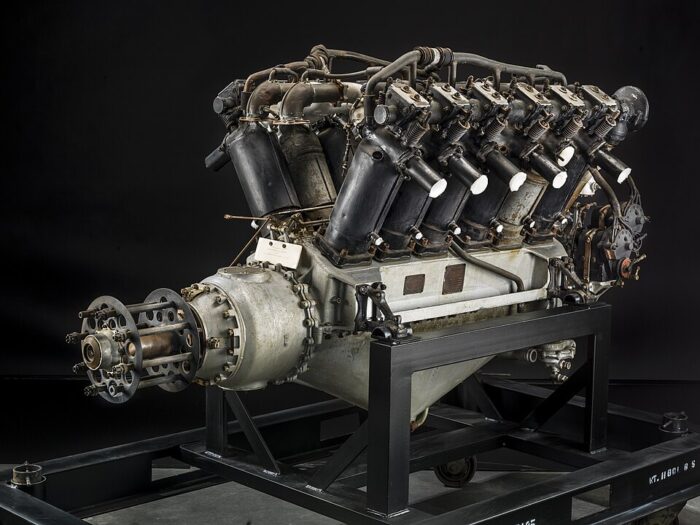

Engine:

The 345 hp (257 kW) Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII was the main engine, a V12 used for this series, with two suspended below the main upper wing on a struts cage. Both drive a two-bladed wooden fixed pitch propeller. The Rolls-Royce Eagle was the first aircraft engine developed by the company, introduced in 1915 to meet British military requirements. Its most famous user was the Handley Page Type O bombers series, and many others. It also famously powered the modified Vickers Vimy making the transatlantic flight of Alcock and Brown in June 1919. The VIII was the penultimate evolution of the type produced in 1917-1922 and capable of 300 hp as baseline, but it was pushed up to 345 hp in 1918 and knew extensive modifications. With 3,302 built at Derby this was the largest production of the entire lineage, by far. For reference, the Eagle I developed 250 hp and the Eagle IX, built until 1928, developed 360 hp as a baseline, then 400+ hp.

This gave the Felixstowe F.2A good performances overall, despite the bulk and drag of the wide body fuselage hull. Top speed was a very honourable 95.5 mph (154 km/h, 83 kn) at 2,000 ft, in 1917, for a flying boat, this was excellent, most importantly, the endurance was 6 hours at an economical speed of 100 kph. The service ceiling was 9,600 ft (2,926 m), ensuring a good spotting scan for many miles around. Of course time to altitude was not impressive, but still, the Felxstowe could take 3 min 50 s to 2,000 ft (610 m), and up to 39 min 30 s to 10,000 ft (3,050 m). Wing loading was 9.69 lb/sq ft (47.4 kg/m2) and the power to mass ratio was 0.063 hp/lb (0.10 kW/kg).

Armament

A model of the Chilean F2A postwar.

The Felixstowe F.2A was the “flying porcupine” of its day. The Lewis machine gun was the go-to aircraft defensive armament of 1917, and it was soon realized that a twin mount was preferable. But initially, there were single mounts: One in the nose Scarff ring mount, one dorsal aft of the wings, and two on pillar mounting at each of two beam positions amidship. In 1918 close to the end of the war, the two ring mounts had twin MGs, making for a total of six, and up to seven in some cases. The F.2 was slower than most fighters, capable of more than 250 kph in 1918 (so a 100 kph difference) but it was agile, which combined to the firepower and general resilience thanks to the well-built hull, make it difficult to shoot down. Being a patrol seaplane, the F.2 could also carry an offensive payload, up to 460 lb (210 kg) of bombs underwings, generally in the shape of four 50 kgs models. A single one even making a near miss of a surfaced U-Boat, could easily rupture its pressure hull.

⚙ Felixstowe F.2A specifications |

|

| Empty Weight | 7,549 lb (3,424 kg) |

| Gross weight | 10,978 lb (4,980 kg) |

| Lenght | 46 ft 3 in (14.1 m) |

| Wingspan | 95 ft 7.5 in (29.15 m) |

| Height | 17 ft 6 in (5.34 m) |

| Wing Area | 1,133 sq ft (105.3 m2) |

| Engines | 2× Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII V12 piston, 345 hp (257 kW) |

| Wing loading: | 9.69 lb/sq ft (47.4 kg/m2) |

| Power/mass: | 0.063 hp/lb (0.10 kW/kg) |

| Top Speed, sea level | 95.5 mph (154 km/h, 83 kn) at 2,000 ft |

| Climb Rate | 3 min 50 s to 2,000 ft (610 m), 39 min 30 s to 10,000 ft (3,050 m) |

| Ceiling | 9,600 ft (2,926 m) |

| Armament | 4× .303 in (7.7 mm) Lewis MGs, 460 lb (210 kg) bombs |

| Range | 6 hours endurance, c1000 nm |

| Crew | 4: Pilot, navigator, 2 gunners. |

Production & Variants

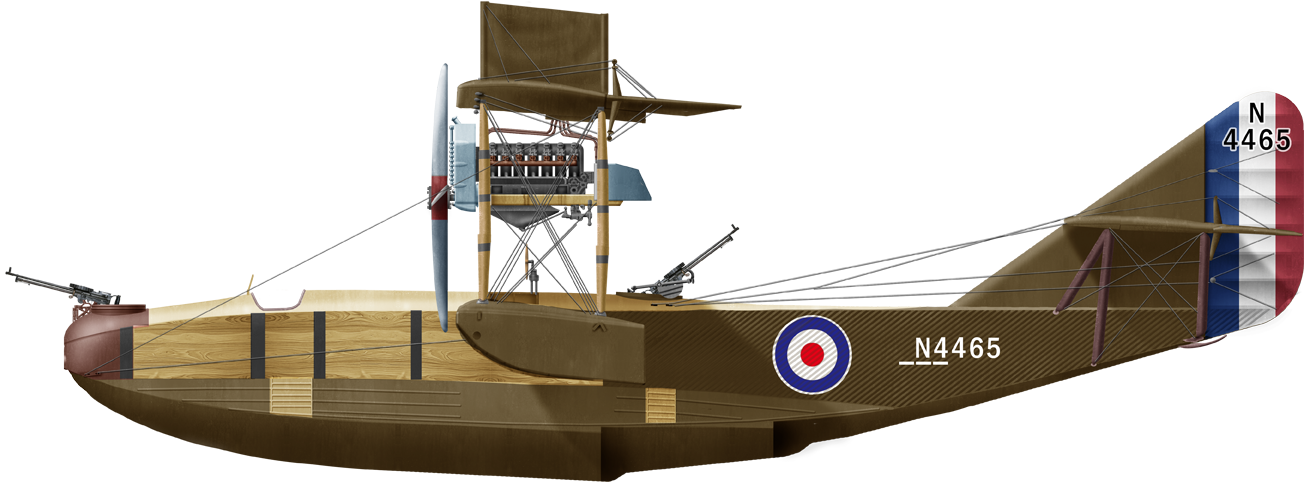

- F.2A: H12 with a new hull, 2x 345 hp RR Eagle VIII engines, 4-7 LMGs, 460 lb of bombs. Bulk of the production.

- F.2B: Same with open cockpit. Only a few built.

- F.2C: F.2A with a lighter hull. 2 built.

Operators

Chilean F2A at Las Torpederas Aeronaval Base in the interwar.

Single F2A obtained in 1920, discarded 1924.

Single F2A obtained in 1920, discarded 1924.

N4551 obtained in 1918 for the RNNAS as ‘L2’.

N4551 obtained in 1918 for the RNNAS as ‘L2’.

RNAS and 228, 230-232, 234, 240, 247, 249, 257, 259, 261, 267 Squadrons RAF.

RNAS and 228, 230-232, 234, 240, 247, 249, 257, 259, 261, 267 Squadrons RAF.

Evaluated by the USN in 1917 agains the Curtiss H12.

Evaluated by the USN in 1917 agains the Curtiss H12.

Combat

The RNAS already operated its H-12s, H-16s as well as Felixstowe F.2, 5 and 9 from flying boat stations on the west and east coasts, among which Felixstowe, for long-range anti-submarine and anti-Zeppelin patrols, over the North Sea. The RNAS operated 71 H-12s and 75 H-16s operating from April 1917, 18 H-12s and 30 H-16s still active by October 1918. The Felixstowe entered service in January 1917 and operated with the RNAS, and then with the 228, 230, 231, 232, 234, 240, 247, 249, 257, 259, 261, 267 Squadrons of the RAF after the services’ unification.

The RNAS already operated its H-12s, H-16s as well as Felixstowe F.2, 5 and 9 from flying boat stations on the west and east coasts, among which Felixstowe, for long-range anti-submarine and anti-Zeppelin patrols, over the North Sea. The RNAS operated 71 H-12s and 75 H-16s operating from April 1917, 18 H-12s and 30 H-16s still active by October 1918. The Felixstowe entered service in January 1917 and operated with the RNAS, and then with the 228, 230, 231, 232, 234, 240, 247, 249, 257, 259, 261, 267 Squadrons of the RAF after the services’ unification.

The Felixstowe F.2A was used as over the North Sea until the end of the war, combining excellent performance and manoeuvrability. It was very popular, also attacking German patrol vessels, surfaced U-Boats, but also combated and proved resilient against German, seaplane fighters or even land fighters. It was the “flying porcupine” of its day with up to seven defensive MGs, and surprisingly agile. Furthermore, it was also found effective against Zeppelins. The larger F.3 was less popular as the crews found it more sluggish than the F.2A. It was relegated to the Mediterranean in 1918, while F2As were concentrated on the North Sea. The F.5 enter service after WWI, but replaced both the F2s and Curtiss H series of 1915-17. The F5 was more successful than the F3, thanks to its new engines and remained popular and standard with the RAF, filling all its flying boat squadrons until replaced by the Supermarine Southampton in 1925. The next posts will be about the F.3 and F.5.

Gallery

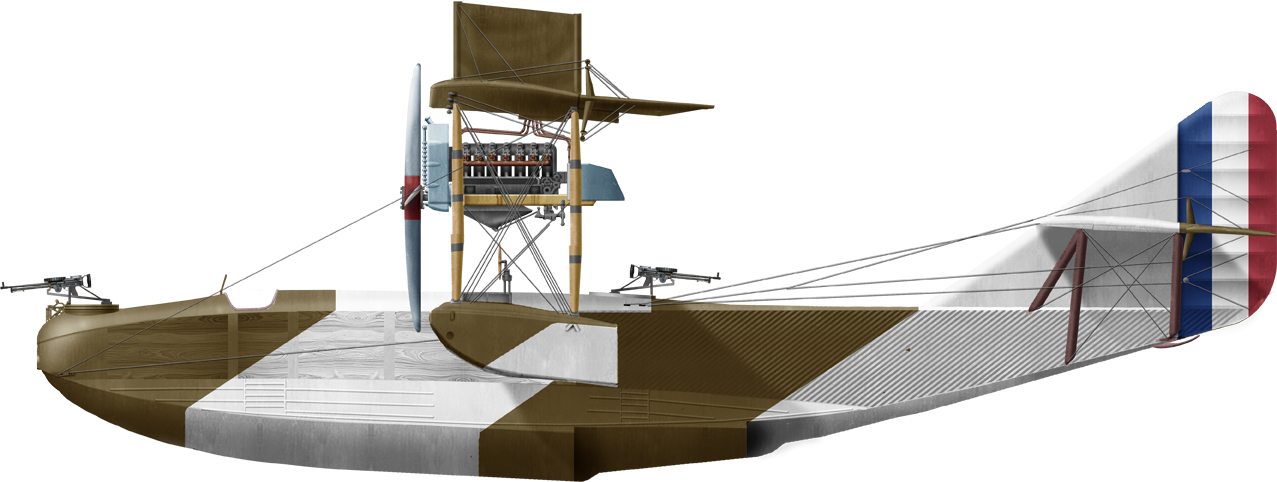

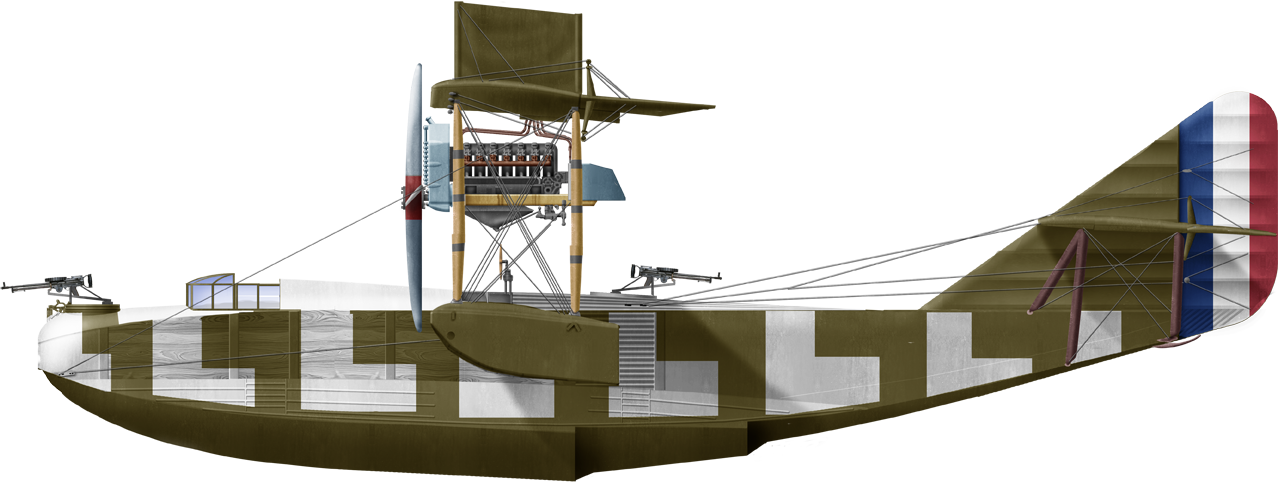

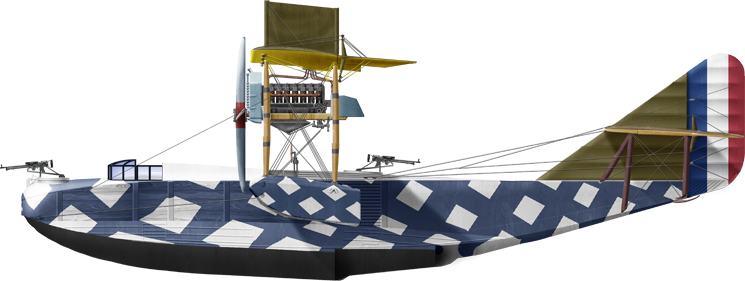

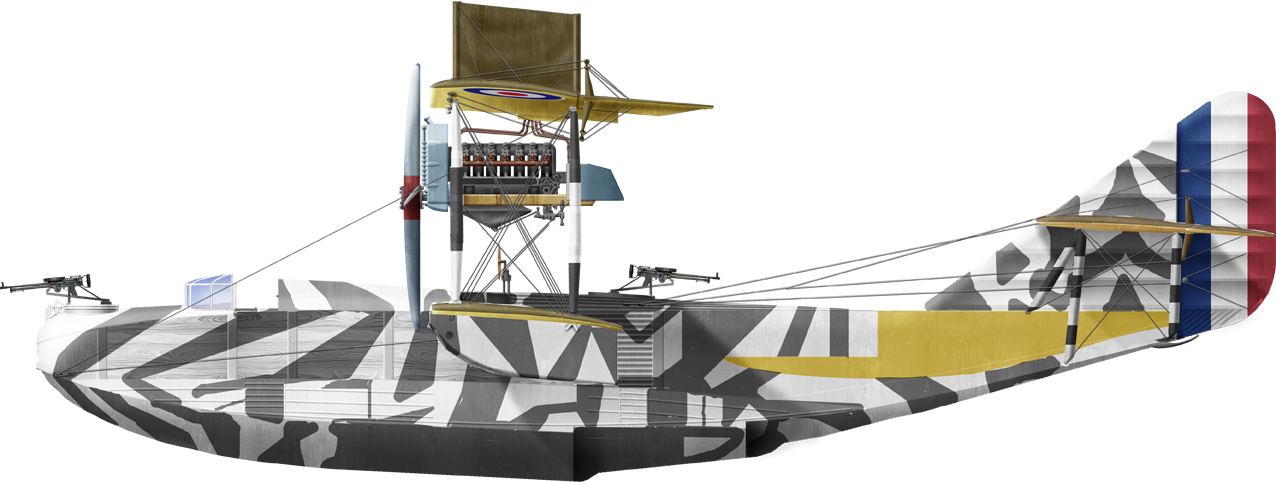

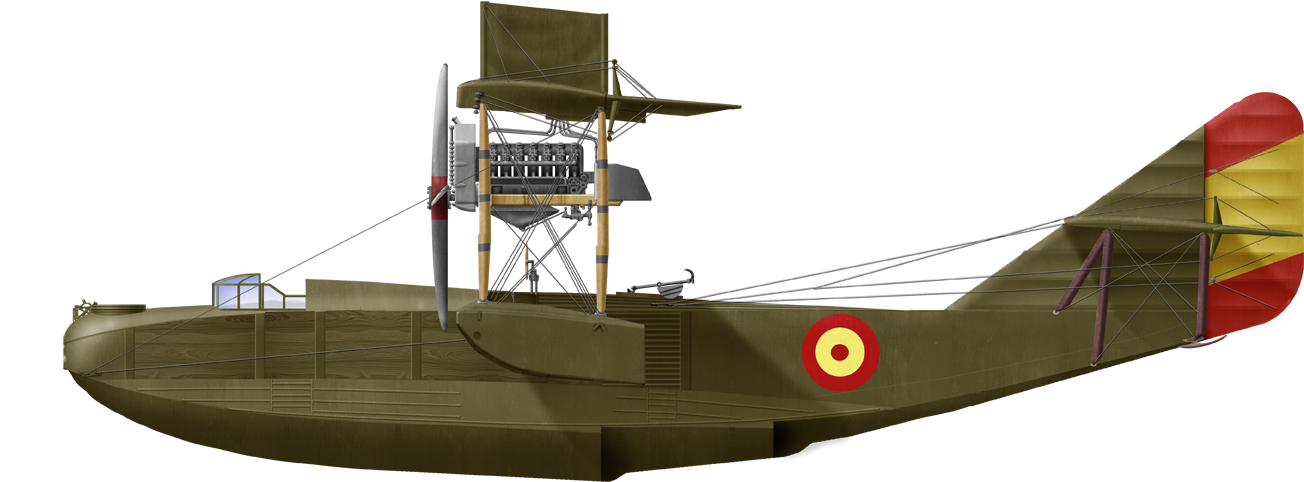

The appearance of the F2A was initially dictated by the materials used. But regulatory colours were imposed, the standard RAF “khaki-brown” with the tricolour tail, large wing roundels, became standard. However, in 1917 razzle-dazzle camouflage experiments were all the rage, and these seaplanes received among the most amazing liveries of the day. Most were dictated by the need of experimenting patterns, but there was a lot of “artistic licence” in the choices of shapes and colours, and this was closer to WW2 US bomber identification schemes rather than efficient camouflage patterns.

Illustrations

Felixstowe F2A N4087 in Felixstowe 1917

F2A in Dazzle Camo 1917

F2A in Dazzle red base Camo 1918

F2A Dazzle camo 2, 1918

F2A late production with open cockpit 1918

F2A N4283, Great Yarmouth NS, 19 March 18

Spanish F2A postwar

Photos

Read More/Src

Books

Bruce, J.M. “The Felixstowe Flying-Boats: Historic Military Aircraft No. 11” Flight, December 1955

Bruce, J.M. British Aeroplanes 1914-18. London: Putnam, 1957.

Hallam, T.D. The Spider Web: The Romance of a Flying Boat War Flight. London: William Blackwood, 1919.

London, Peter. British Flying Boats. Stroud, UK: Sutton Publishing, 2003.

Rivas, Santiago. British Combat Aircraft in Latin America. Manchester, UK: Crécy Publishing, 2019.

Thetford, Owen. British Naval Aircraft since 1912. London: Putnam, Fourth edition 1978.

Links

aviadejavu.ru

rafmuseum.org.uk

flyingmachines.ru

aircraftinvestigation.info

airwar19141918.wordpress.com

aviation-history.com/

CC images

Felixstowe_F.2

Curtiss_Model_H

willhiggs.co.uk

flightglobal.com

Felixstowe_F.1

flightglobal.com/PDFArchive, Cyril Porte

LAUNCHING OF “AMERICA” (1914) footage

John_Cyril_Porte

gracesguide.co.uk

aeroplanes.fr

iwm.org.uk footage, pigeons launched from F.2s

Model Kits

scalemodellingnow.com

hyperscale.com

modelingmadness.com

Video

Curtiss and Felixstowe Seaplanes documentary

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign