The Trafalgar of ironclads

While on the other side of the Atlantic, a young nation still constructing was reeling from its worst, first, and last civil war, innovating and experimenting in naval matters along the way, new nations of turbulent Europe were struggling for independence. A particular ship of that era, the ironclad, was green and untested. The battle of Lissa became the “Trafalgar” of ironclads and had many important developments and consequences on naval warfare and warship designs until after ww1. However, some also argue this was the “most hilarious” industrial era naval battle ever, at a time armor was superior to gunnery.

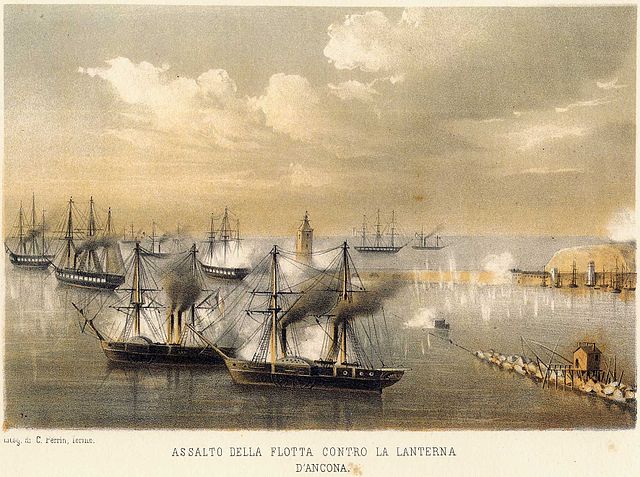

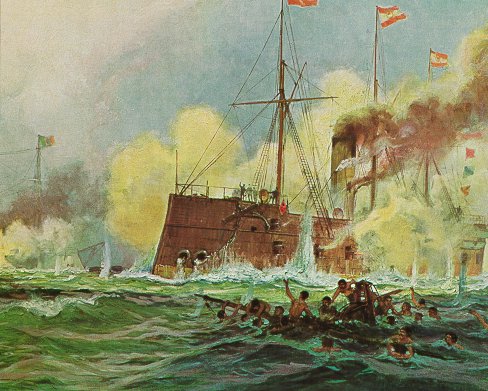

Battle of Lissa by Josef Carl Berthold Püttner

Context: Italy’s third independence war

When speaking of young countries, Italy was one of these Nations very old and yet of particularly significant historical heritage, yet disunited after the fall of the Roman Empire. In the 1860s, nearly 1400 years after this downfall, unification was on sight once again. In this last risky game, what constituted Italy then was allied with Prussia and pitted against the old enemy, Austria. The objective to complete the unification was to gain the old Venetia, dominating the Adriatic constituted of Venice and at least part of its surrounds from Austria.

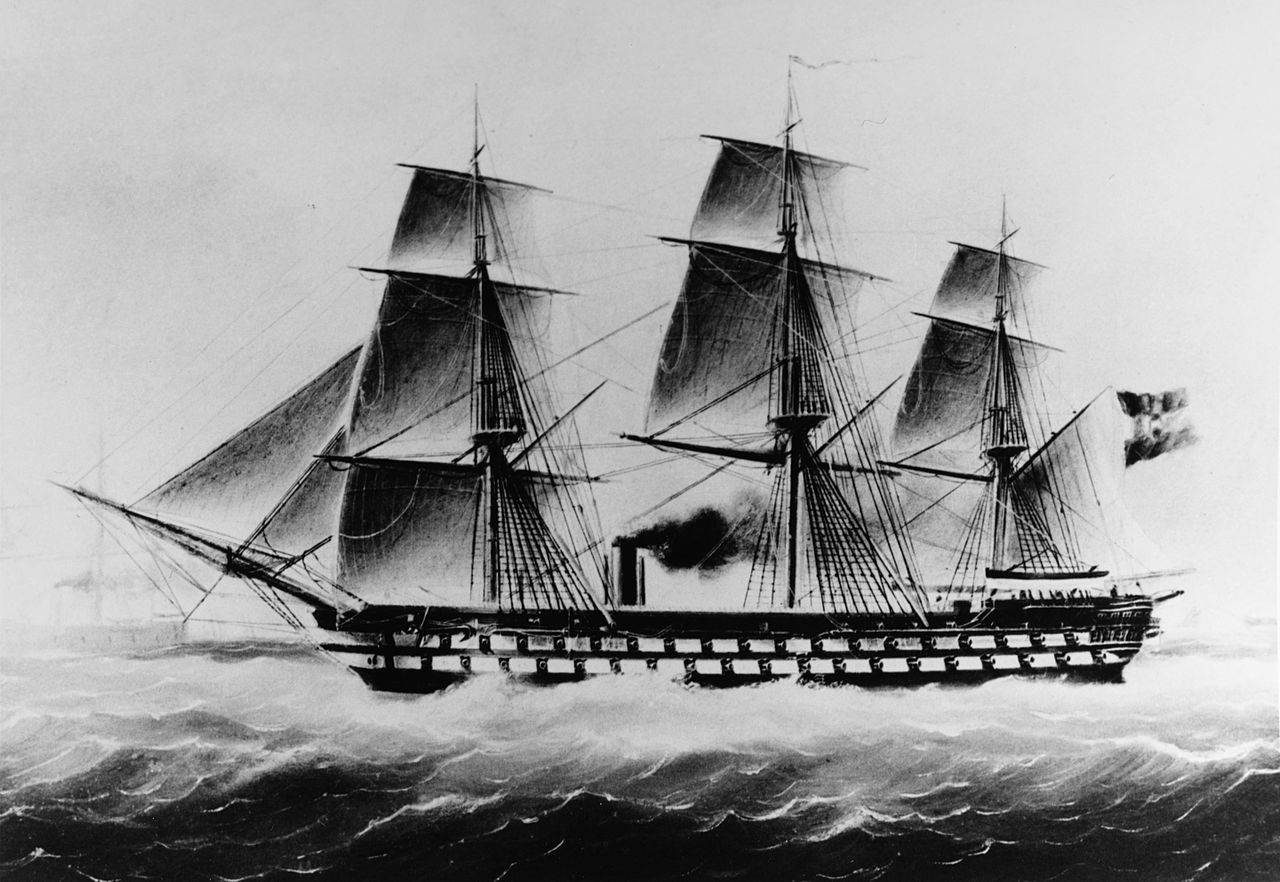

French broadside Ironclad Gloire (1859). Like the dreadnought in 1906, this ship rendered obsolete all traditional fleets, already still reeling from the conversion to steam. However at that time, armor was superior to muzzle velocity. The world took notice and in the 1860s, UK, the Italian Kingdoms, Prussia, Austria, Spain and Turkey invested in this new kind of warship. The Royal Navy soon retook the lead with the HMS Warrior, first all-steel broadside ironclad. (Author’s illustration)

While the war raged from June to August 1966, and saw a victory for the Italians, securing the status of Victor Emmanuel III and Garibaldi in history books as founding fathers, Independence was also secured by the northern diversion procured by the Prussians and previous decisive victories of Napoleon III (Solferino and Magenta).

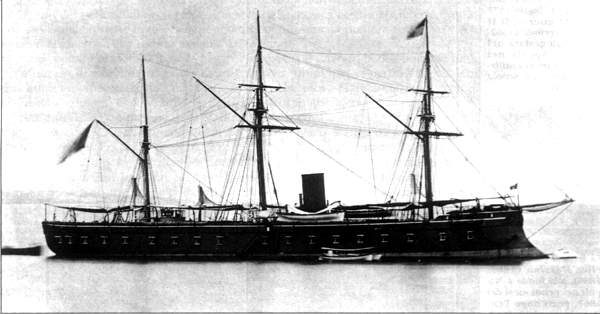

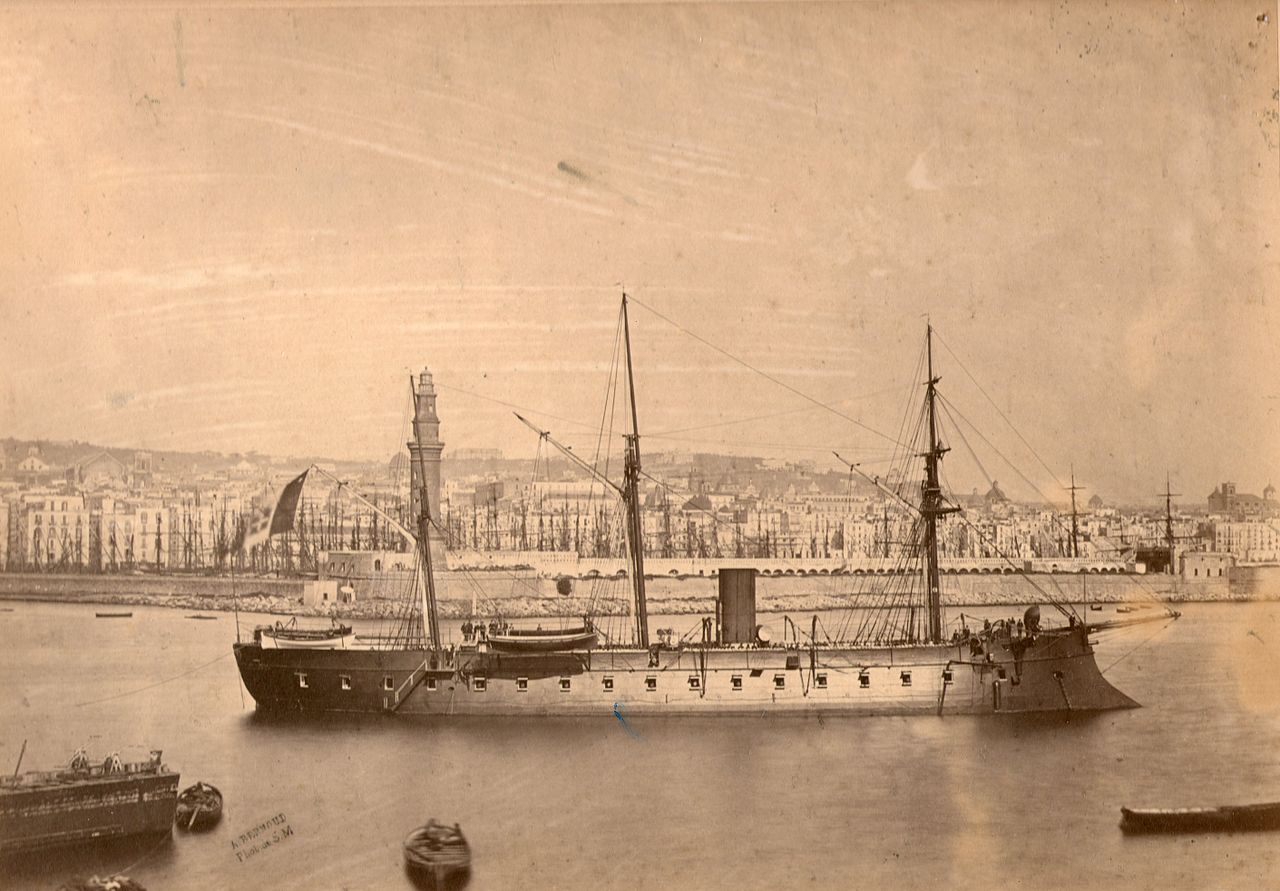

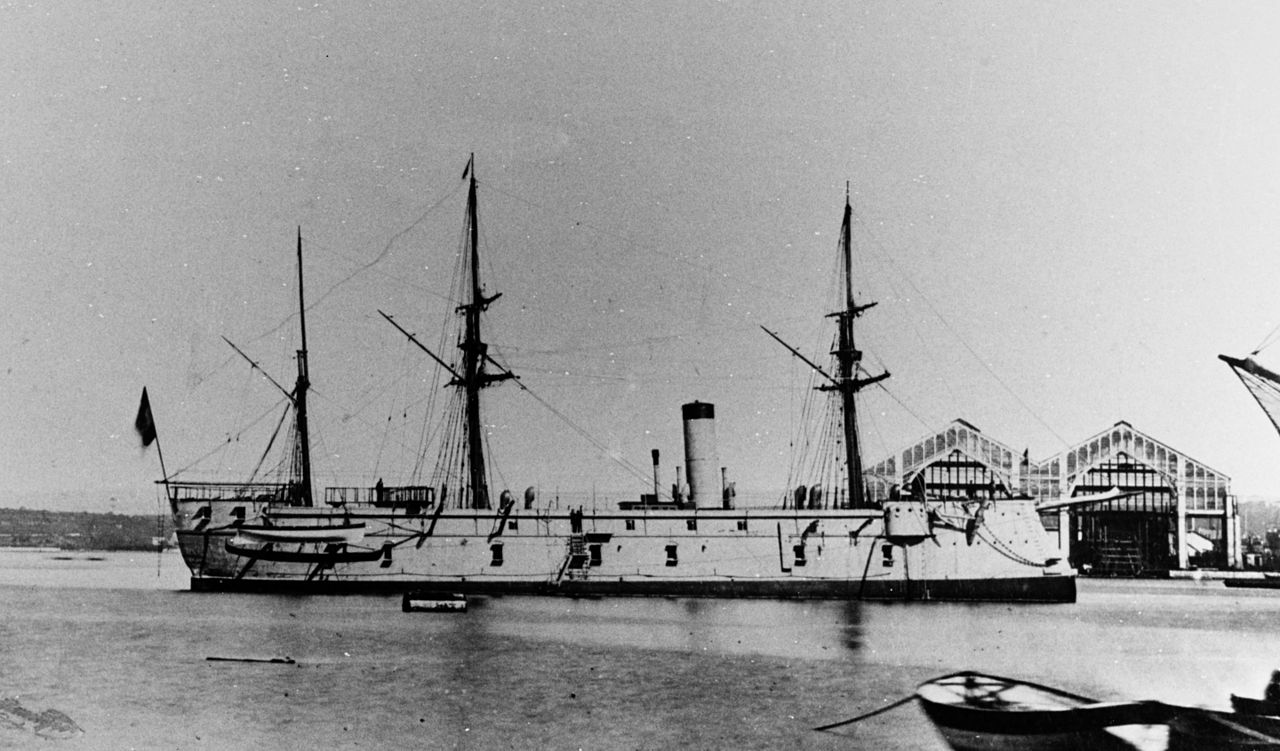

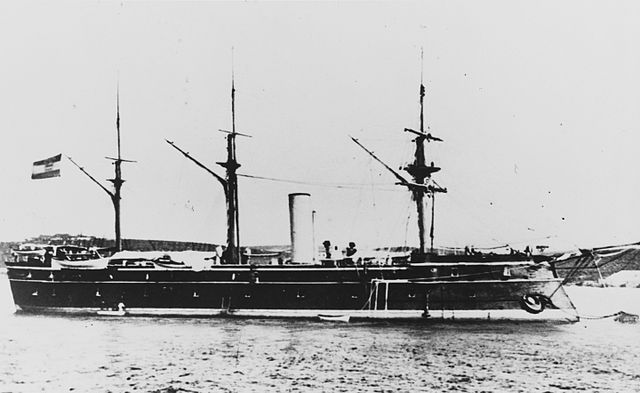

Ironclad Ancona in 1870, built with the lessons of the battle

In this part however, the fleet played an important role, but on the losing side: The recently unified Italian Navy, commanded by Admiral Carlo di Persano was to set sail from Ancona with the objective of seizing Trieste. Although outnumbering the Austrians by a fair margin, the result was a victory for the latter, sinking two Italian Ironclads while only having a steamer damaged. The battle was fierce and reintroduced the ram in naval warfare. It was both a test for ironclads and for turret ships. On the Austrian side, it made Teghetthof a national hero and a revered figure patronizing the later Austro-Hungarian Navy.

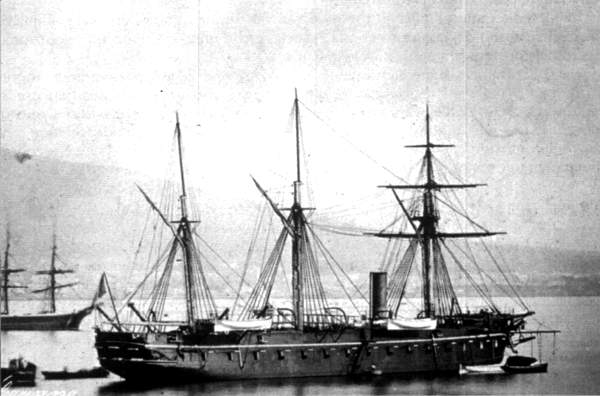

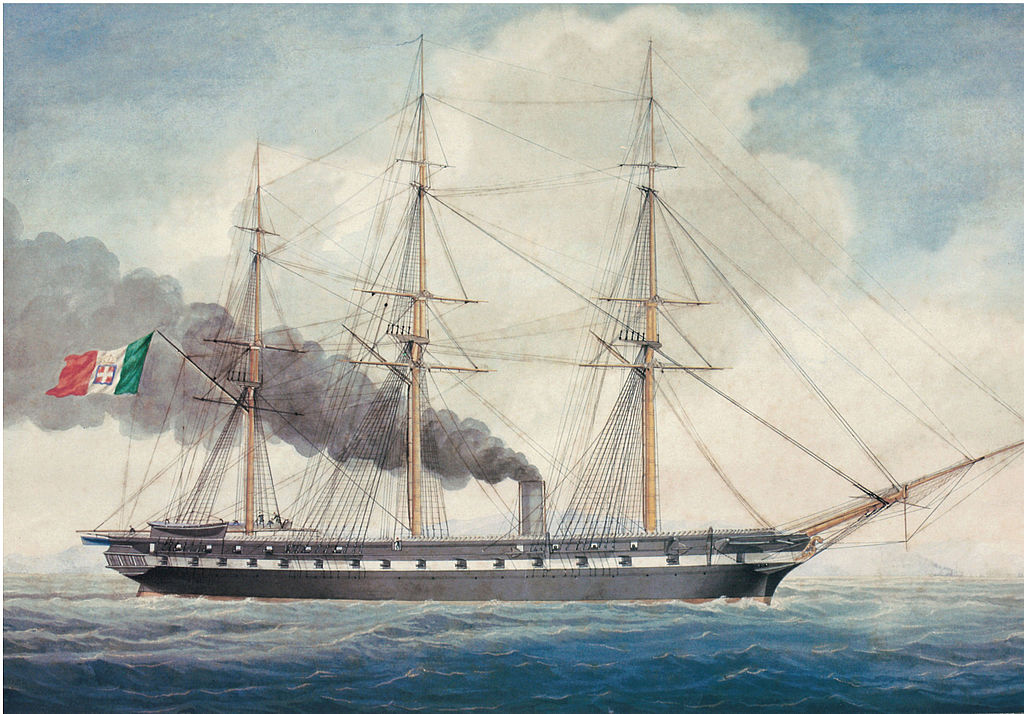

Italian wooden frigate Carlo Alberto (1853). This former Sardinian 3231t vessel was armed by eight 160 mm ML rifles, ten 108pdr and thirty-two 72pdr guns firing shells plus, 7 smaller gun. She fought at Lissa.

Austrian ironclad Drache (1861). Together with the Salamander, these early Austrian wooden broadside ironclads were barely larger than glorified corvettes, but a 110 mm armored belt made all the difference. Shells just bounced harmlessly on her.

Forces in presence: The Italian Navy

Despite numbers in her favor, the Regia Marina was hampered by its very constituents, former independent navies which grew even stronger rivalry, despite being technically under the same banner since 17 March 1861. These were the fleets of the former kingdoms of Sardinia and Naples. Both had different practices, naval academies and traditions, not speaking of different ships.

Plus this new Navy appeared and spent a great deal of energy to unite amidst an era of rapid advances in naval technology and tactics. Despite all of this, the ships engaged in 1966 were steam-driven, armored for most, one even being a brand new concept, the turret ironclad ram (Affondatore). This was due to the efforts Admiral Carlo di Persano made into purchasing ships abroad to supply the lack of suitable yards and expertise. Therefore the largely obsolete navy of the years before was completely eclipsed by a new one, certainly up-to-date but still exhibiting some peculiarities. In addition, foreign ships meant longer training, supply and maintenance issues.

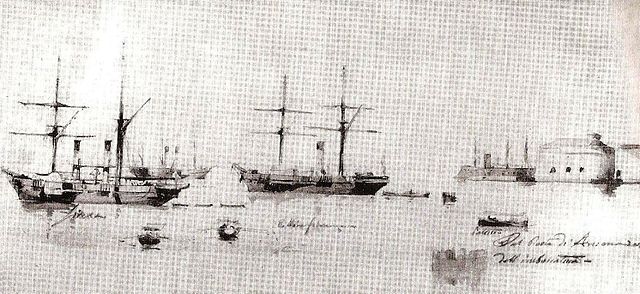

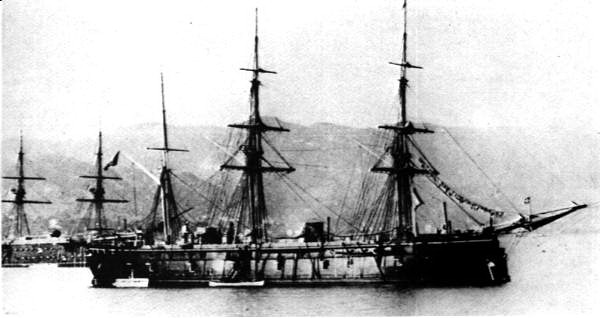

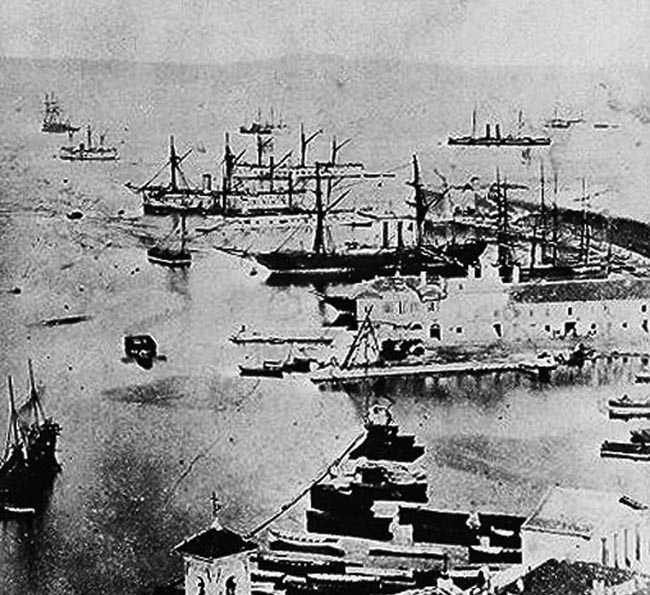

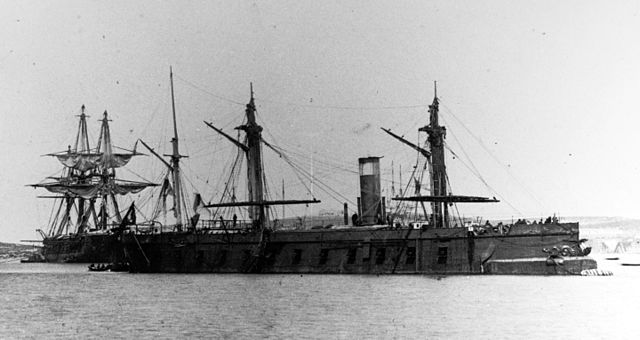

The Italian fleet gathering at Ancona in 1866 before the battle.

On paper however, it was formidable. The day of the battle, Italy could muster 12 ironclads, mostly built in France, on the Gloire model (1859) or her derivatives. They were wooden-hulled with iron sides over the waterline, and one protected gun deck, full rigging, steam and screw, but lacked a spur. Half of the fleet was made of wooden steam warships, in which protection was limited to traditional multiple layers of different woods. Speed on average was 10 knots, Austrian ships were a little built faster.

Broadside ironclad Formidabile. First of this type in service with the Italian Navy, this 2800 tons wooden-built small corvette was protected by a complete belt, 109 mm thick and armed with just 20 guns.

However, on the gunnery side, they were all equipped with classic broadsides of old-style RML (Rifle Muzzle-Loading) guns firing lead balls or 1850s Paixhans-style explosive projectiles. Naval technology was evolving very fast. In less than 10 years, Breech-loading rifled cannons firing explosive shells, central batteries with 90° traverse or turrets, double and later triple expansion steam engines, all-steel hulls revolutionized naval technology. Most of these transitions were happening at the time and after the battle.

Not all Italian warships were present at the battle such as the Galantuomo, a wooden, steam unarmored 84 guns two-decker ship of the line (Authors illustration for cyber-ironclad). She was the admiral ship of Ferdinand II, and named Monarca at first.

The Italian steam Frigate Italia. She was originally the 54-guns Neapolitan navy Farnese. Not in action at the battle.

In addition to 13 ironclads, 10 wooden steam frigates and corvettes, the Regia Marina also was supported by 10 smaller steamers such as the Giglio, an ex-Tuscan sloop of 1846 (246t, 2 SB), the three Cristoforo Colombo class gunboats (4-30pdr SB), the 1863 two sidewheel dispatch vessels of the Esploratore class (981t, 2-30pdr SB, 17 knots) and the unarmed support merchantman Indipendenza, Piemonte, Flavio Gioia and Stella d’Italia.

Ironclads

Formidabile class (1861):

Both the Formidabile and Terribile were ordered by the Kingdom of Sardinia in 1860. Both ships did saw heavy action against the Austrians during the War of Independence of 1866 and Lissa campaign but without participating in the battle itself.

- Displacement 2807t – 3100 tons FL

- Armament 4 × 203 mm (8 in), 16 × 164 mm (7 in) guns

- Armor: Belt 109 mm

- Single shaft, single-expansion steam engine, 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph)

Principe di Carignano class

The first Ironclad built in Italian yards. These units were ordered at the same time the Formidabile class, but the first two had been laid down as unarmored steam frigates and conversions took place during construction. The class comprised in total three ships, such as the Messina and Conte Verde.

The Principe di Carignano only was been completed in time to see action in the Third Italian War of Independence, taking part in the Battle of Lissa, as the lead ship in the Italian line of battle, but not heavily engaged, contrary to ships in the center, more heavily attacked by Tegetthoff.

- Displacement 3900t – 4300 tons FL

- Armament 10 × 203 mm (8 in), 12 × 164 mm (7 in) guns

- Armor: Belt 121 mm (4.7 in)

- Single shaft, single-expansion steam engine, 10.4 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph)

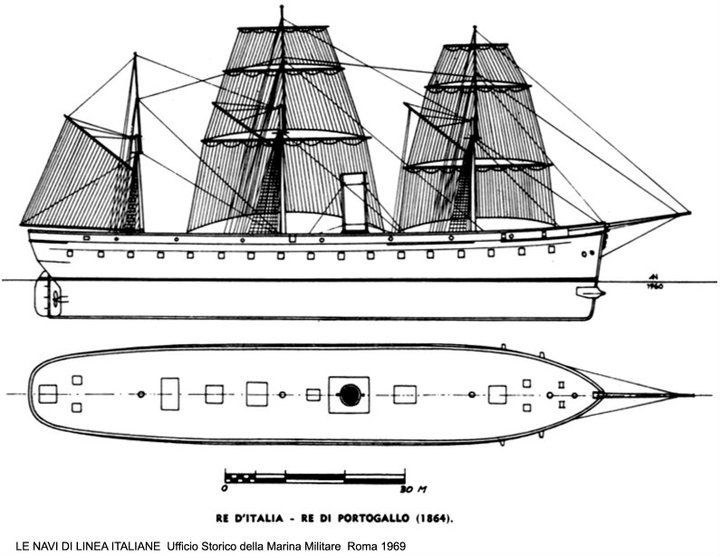

Re d’Italia class

To compensate for the busy Italian shipyards, the new Kingdom of Italy completed orders abroad, and after France, the Re d’Italia class was ordered from the United States, which themselves have no previous experience for this type of ship but the Old Ironsides, copied the French Gloire. They were larger and carried 36 heavy guns, but proved unsuccessful in service. Their sterns were unprotected and lightly built, causing the Re d’Italia to be rammed and sink at the Battle of Lissa but also to use unseasoned timbers for their wooden hulls, rotting fast. The class comprised also the Re di Portogallo, both were launched in 1863.

- Displacement 5700 tons FL

- Armament 6 × 203 mm (8 in), 30 × 164 mm (7 in) guns

- Armor: Belt 114 mm (4.5 in)

- Single shaft, single-expansion steam engine, 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph)

Regina Maria Pia class

Other orders were placed for four more ironclads in 1862, from three different shipyards, varying slightly in their dimensions, but answering to the same specifications. They had the same twenty-six heavy guns in broadside while three were placed in forward and rearward firing barbettes. They proved more effective in service than the Re D’Italia class and stayed in service until the 1880s. They were launched in 1863 and completed in 1864.

The class comprised the Regina Maria Pia, San Martino, Castelfidardo and Ancona; They formed the core of the Italian ironclad fleet, the center of the battle line at Lissa and therefore the most heavily engaged. San Martino while trying to salvage Re D’Italia’s survivors and collided the Regina Maria Pia, and the latter collided with the Varese. They survived as served for twenty more years.

- Displacement 4,527 t (4,456 long tons; 4,990 short tons)

- Armament 8 × 203 mm, 22 × 164 mm guns.

- Armor: Belt 121 mm (4.7 in)

- Single shaft, single-expansion steam engine, 12.96 knots (24.00 km/h; 14.91 mph)

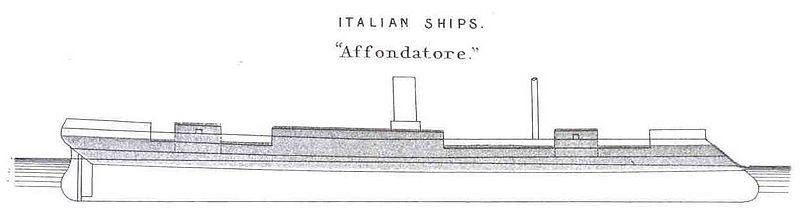

Affondatore

Certainly the most remarkable Italian ironclad of this battle, this ship was one of the earliest sea-going turret ship. She was ordered from UK in 1862, the last foreign-built ironclad of the Italian Navy. When the battle of Lissa began she was also the only one with a built-in ram. It has been designed however by Simone Antonio Saint-Bon, originally as a ramming ship, semi-submerged ship like some Confederate ones, but a British designer altered the design when in construction for the ship to be fitted with a pair of 300-pound Armstrong guns, each in their own Coles turret.

She has a low freeboard and reduced superstructure, which can help reduce armor and make her more difficult to hit. She was just being fitted out in June 1866, when war was to break out and was sent to Italy fast with a reduced crew and no training, part of her equipment missing. At Lissa, Affondatore received admiral Persano, which hoisted his flag on her rather than the Re d’Italia, but without informing the rest of the fleet, causing much confusion. He therefore failed to rally the ships not engaged and after Re d’Italia was rammed and sunk, he led Affondatore in the heart of the melee, trying to ram the Kaiser. Affondatore foundered after the battle due to gun damage and the storm but was refloated, modernized three times and was still active in 1907.

Roma & Principe Amadeo class (In construction)

In 1863, another two ironclads were ordered at a time central battery ships started to be tried and replace broadsides. The formula had the advantage of concentrated protection in one space (which could be made thicker) and heavy guns with more traverse. Roma was the first to be built, while her sister ship Venezia was extensively reworked while under construction as a central battery ship. While Roma had five 254 mm and ten 203 mm guns, Venezia had eighteen 254 mm guns, and when she entered service, the Caio Duilio-class turret ships were already laid down.

Both were built before, but completed after the Third Italian War of Independence, and both missed the battle of Lissa. They were commissioned indeed in 1869 and 1873 but served until the 1890s. Also of this prewar generation, the Principe Amadeo class were laid down in August 1865, also as central battery/broadside mixed ironclads, way too late to take part in the battle of Lissa as they entered service in 1874-75.

Wooden Frigates

- Gaeta (ex-Neapolitan) 1861, 3917t, 8–160 mm ML rifles, 12-108pdr shell, 34-72pdr shell)

- Maria Adelaide (ex-Sardinian) 1859, 3429t, 10–160 mm ML rifles, 22-108pdr shell, 19 small guns) (Squadron Flag)

- Duca di Genova (ex-Sardinian) 1860, 3459t, 8–160 mm ML rifles, 10-108pdr shell, 32-72pdr shell)

- Garibaldi (ex-Neapolitan Borbone) 1860, 3390t, 8–160 mm ML rifles, 12-108pdr shell, 34-72pdr shell)

- Principe Umberto (ex-Sardinian) 1861, 3446t, 8–160 mm ML rifles, 10-108pdr shell, 32-72pdr shell, 4 small guns)

- Carlo Alberto (ex-Sardinian) 1853, 3231t, 8–160 mm ML rifles, 10-108pdr shell, 32-72pdr shell guns, 7 small guns)

- Vittorio Emanuele (ex-Sardinian) 1856, 3201t, 8–160 mm ML rifles, 10-108 and 32-72pdr shell guns, 7 small guns)

- San Giovanni (ex-Sardinian corvette) 1861, 1752t, 8–160 mm ML rifles, 14-72 pounder shell, 12 small guns)

- Governolo (ex-Sardinian sidewheel paddle corvette) 1849, 2243t, 10-108pdr shell, 2 small guns)

- Guiscardo (ex-Neapolitan sidewheel paddle corvette) 1843, 1343t, 2–160 mm ML rifles, 4-72pdr shell)

Forces in presence: The Austrian Navy

Note this was the Austrian, not Austro-Hungarian Navy. Indeed, the Empire was unified after 1867 as a consequence of the battle and Italian Independance (but not only that). The flag was the classic three bands red and white with Royal armories.

Ironclads

Drache class (1861):

Laid down in February 1861, launched in 9 September 1861 and completed in November 1862, the Drache class (Drache and Salamander) were the first Austrian ironclads, built locally at Trieste in response to the Italian Formidabile class, following the launch of Gloire in France in 1859. The ship was propelled by a single shaft and horizontal steam engine, single funnel and 2000 hp. The armament comprised ten 48-pounder smoothbore guns and eighteen 24-pounder rifled, muzzle-loading (RML) guns. During the battle, Drache engaged Palestro with concentrated broadsides, using hot shot to set the Italian ship ablaze. She fled, and Drache then turned against the Re d’Italia. She was hit during this time, a shot killing the captain and another the mainmast. This was not serious though and the ship emerged from the battle largely unscathed.

- Displacement 3110t – 3160 tons FL

- Armament 10 × 48 pdr, 18 × 24 pdr guns

- Armor: Belt 115 mm

- Single shaft, single-expansion steam engine, 10.5 knots (19.4 km/h; 12 mph)

Kaiser Max class (1862):

The next class ordered by the head of state alongside the Drache were three larger and improved broadside ironclads named SMS Kaiser Max, Prinz Eugen, and Juan de Austria. They had a larger gun battery and more powerful engines, being quite fast. They were launched in 1862 and completed in 1863. SMS Don Juan d’Austria already saw the Second Schleswig War (1864) but did not see combat. At the Battle of Lissa however all three saw action. They were heavily engaged, but not seriously damaged nor inflicted heavy damage to their adversaries, their balls bouncing harmlessely on the armor plating. After the war they were comprehensively modernized.

- Displacement 3588t – 3955 tons FL

- Armament 16 × 48 pdr, 15 × 24 pdr, 1x 12 pdr, 2x 6 pdr guns

- Armor: Belt 110 mm

- Single shaft, single-expansion steam engine, 11.4 knots (21 km/h; 13 mph)

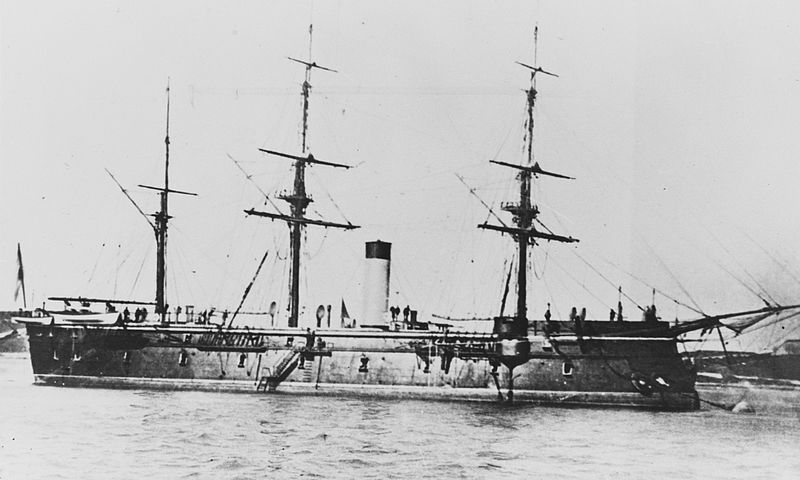

Erzherzog Ferdinand Max class (1865):

The Erzherzog Ferdinand Max and Habsburg were the first serie of ironclads built for the Austrian Navy but also their last broadside armored frigates. They were to be armed with breech-loading Krupp guns but the outbreak of the 1866 War prevented it, swapped to a conventional 48-pdr muzzle-loading guns battery.

Barely outfitted, both ships were thrown into the Battle of Lissa. Erzherzog Ferdinand Max was the flagship of Rear Admiral Wilhelm von Tegetthoff, famously ramming and sinking the Re d’Italia, the decisive action in that particular battle and probably the most famous ramming in history. SMS Habsburg was not significantly engaged however. She pounded Italian ships but without much success. Both would be modernized as intended with modern BLs and served well into the 1890s.

- Displacement 3588t – 3955 tons FL

- Armament 16 × 48 pdr, 4x 8 pdr, 2x 3 pdr guns

- Armor: Belt 87-123 mm

- Single shaft, single-expansion steam engine, 12.5 knots (23.2 km/h; 14.4 mph)

Wooden Frigates

- Kaiser squadron flag, 2-decker ship of the line (1858) 5811t, 2-24pdr ML rifles, 16-40pdr SB, 74-30pdr SB, wooden and unarmoured, 11.5kts

- Novara screw frigate (1850) 2615t, 4-60pdr shell, 28-30pdr SB, 2-24pdr BL rifles, 1-12pdr landing gun, 1-6pdr landing gun, 12kts

- Schwarzenberg screw frigate (1853) 2614t, 6-60pdr Paixhans shell guns, 26-30pdr Type 2 ML, 14-30pdr Type 4 ML, 4-24pdr BL rifles, 11kts

- Radetzky class screw frigates (1854-56) 2234t/2165t, 6-60pdr Paixhans shell guns, 40-24pdr SB, 4-24pdr BL rifles, 9kts: Radetzky, Donau, Adria

- Erzherzog Friedrich screw corvette (1857) 1697t, 4-60pdr Paixhans shell guns, 16-30pdr SB, 2-24pdr BL rifles, 9kts

Prelude of the battle

The name of the battle is related to the most strategic piece in the maritime defence of Austria, in the central Adriatic: The unassuming island of Vis (Croatian name nowadays) near the Dalmatian island of Lissa. This was an outpost controlling passage between the north and south the sea and approaches of the coast as the most advanced of all the Islands of the area. This 89.72 km2 (34.64 sq mi) peace of land was 587 m (1,926 ft) high on its maximal elevation and the coast was later riddled with pens and a naval base.

This was an early uninkable “aircraft carrier” (a role which the island would play during the Great war and ww2 as well). A bit like Sicilia for the Mediterranean it was seen also as the “hinge” of the Adriatic. Controlling it was therefore a decisive step in this war. Not surprsingly thare has been already a naval battle here, the first Battle of Lissa (1811) when Captain William Hoste, defeated a larger French squadron there. In 1866, the fort and naval base was under order of Oberst David Urs de Margina, a Romanian officer from Transylvania.

The mobilization of the fleet had taken on the italian side place and on 3 May 1866, General Diego Angioletti, Minister of the Navy, had informed Rear Admiral Giovanni Vacca, commander of the Taranto-based squadron that the government had decided to set up a battle fleet made of three fleets made of armored ships (placed under Admiral Carlo Pellion of Persano), and a subsidiary squadron composed of wooden warships (Under Admiral Giovan Battista Albini) plus a third siege fleet made of armored ships (under Vacca). The Re d’Italia, Principe di Carignano, San Martino, Regina Maria Pia, Palestro, Gaeta and two scout frigates were in Taranto. Formidabile and Terribile, Ettore Fieramosca and Confienza were in Ancona and the other ships in various Italian bases while the remainder of ironclads were just been delivered by shipyards.

In Taranto there was only a small amount of coal, a much larger in Ancona so it was decided to gather all ships there.

Persano arrived in Ancona on May 16, 1866, quickly realizing the unpreparedness of the fleet: Until May 23 and on May 30, he repeatedly informed the Navy Minister of the impossibility of preparing the fleet in a short time. He even thought of resignation, but ultimately decided to prepare the fleet at least for some common exercizes. Vacca collaborated in this attempt, but Albini, hostile to Persano, cooperated very little. On 8 June 1866 Admiral Persano received the order to take on the Austrian fleet, and sailing to Ancona to prepare operations, but not to attack Trieste or Venice. Orders were of unclear origin, neither General Alfonso Lamarmora, Army Chief of Staff or Angioletti, the navy minister.

On 20 June, the Ricasoli government replaced the minister by Agostino Depretis, which first order was to urge Persano to sail from Taranto to Ancona and enter the Adriatic. Persano had trouble to have all ships-boiler hot fast enough. He ordered the Formidabile and Terribile to join the fleet via the southern Adriatic. The naval formation left Taranto on the morning of 21 June 1866, and joined by Formidabile and Terribile in off Manfredonia. The combined fleet arrived in Ancona on the afternoon of 25 June at about five knots so as not to strain the machines.

Ancona however, had no dry dock, and the enclosure defined by the jetty was rather small.

The bulk of the fleet was moored at some distance. Ships proceeding to coaling operations during which accidental fires broke out on the Re d’Italia and Re di Portogallo. It was also established that many wooden ships would give part of their guns to be installed on the ironclads so as to equip them with as many modern 160mm cannon guns as possible. Castelfidardo, Regina Maria Pia, Re d’Italia and di Portogallo, Principe di Carignano, San Martino and Varese therefore received a complement of 20, 16, 12, 12, 8, 8 and 4 additional cannons. Four guns (Castelfidardo and Varese) came from Naples, the rest were taken from other ships. The Duca di Genova for example was almost stripped bare. On June 26, 1866, Persano sent the faster steamers Esploratore to patrol the waters in front of Ancona in case the Austrian sent their own scouts or attempted an attack.

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battaglia_di_Lissa

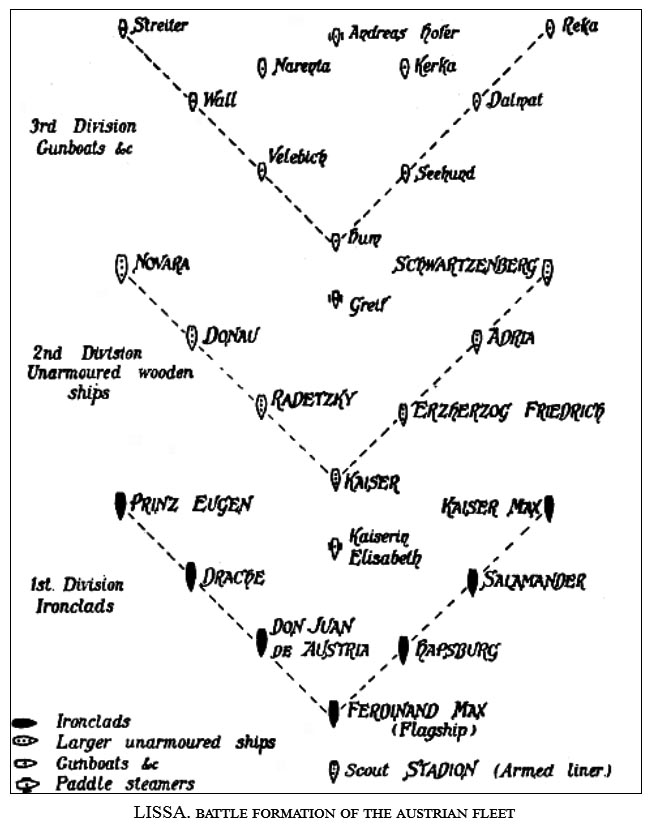

Orders of battle

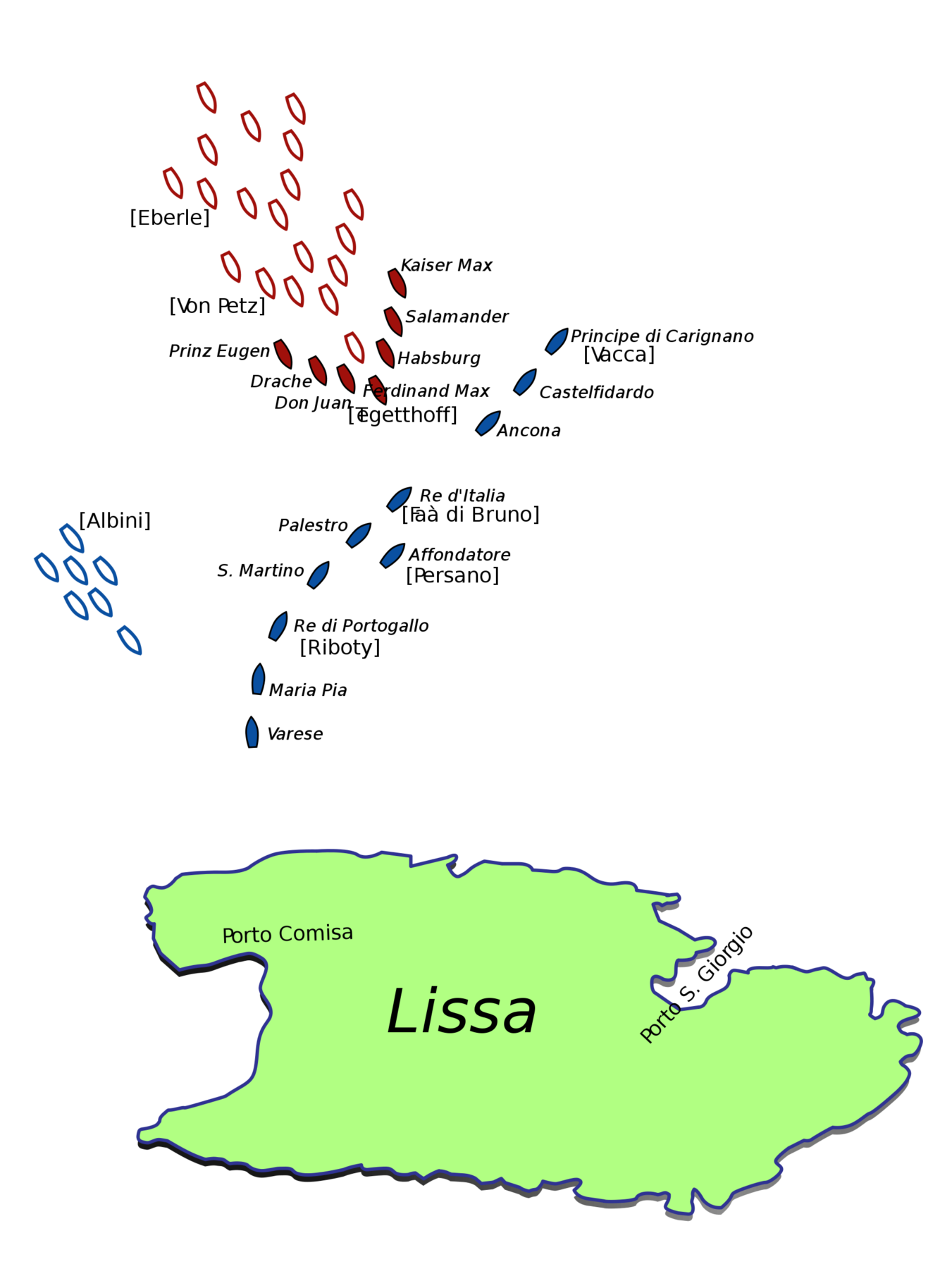

The Italian fleet headed by admiral Persano directed three divisions, himself having the main battle force with 9 ironclads, Albini, the “support” division used to support the landings operations and Admiral Vacca the reserve division composed of wooden ships (seen above).

Facing them, the Austrians split their own force into three divisions. The first was made of the ironclads, the second was made of unarmoured wooden vessels, like ship of the line SMS Kaiser and 5 large frigates. The third one comprised screw gunboats and armed merchantmen while a single armed merchant cruiser, SMS Stadion, was acting as scout well ahead of the fleet.

These three Austrian divisions were formed in successive “V” formations, with the first under Tegetthoff making the forward, outer arrow, and gunboats, paddle steamers closing the march, and Kommodor Petz’s 2nd division’s wooden warships in the central arrow.

Tegetthoff plan was to close quickly into a melée, using both range fire and ramming attack in order to destroy at least a few Italian ships early one and breaking the Italian morale and will to fight.

On their own side, the Italians were not really prepared for battle, as Persano knew perfectly. The day of the battle, they were confident enough of their numerical superiority to focus on covering the landings on Vis (Lissa). They did had scouts; some picket boats which therefore spotted an approaching fleet but signals were at first ignored, wasting precious time. Persano then had eventually the landings operations suspended and tried to hastily reorganize the fleet into a line abreast. However soon after, when the ships were already moving into place, he had serious doubts and canceled the order, creating some confusion and ordered a line ahead formation, a classic from the age of sailing ships of the line.

The 1st division (Principe di Carignano, Castelfidardo and Ancona, Admiral Vacca) moved into place, followed by Captain Faà di Bruno’s 2nd division (center, Re d’Italia, Palestro, San Martino) – which was to take the brunt of the Austrian assault- and the 3rd division (Re di Portogallo, Regina Maria Pia, Varese, Captain Augusto Riboty) followed. The latter saw little action. The Italians’s 11 ironclads was quite a formidable force reinforced by the wooden frigates and corvettes dispersed into the battleline. Affondatore, the “joker” in this game, was on held on the far side of the 2nd squadron, out of the battleline in reserve. By that time Persano’s flagship was the Re d’Italia.

Therefore, soon after the ships moved into this final formation, Persano suddenly decided to transfer his flag from Re D’Italia to the Affondatore. However, this caused another confusion and delays as the two later division had to slow down or stop to allow Re d’Italia to lower her boats, while the signal to slow down was ignored by the 1st Division which continued straight away opening a gap in the Italian battle line.

To add to this mess, Persano never signaled the fact he swapped flagships, and throughout the action, the Italians captains observed carefully the Re d’Italia for orders rather than Affondatore.

The battle: Crossing the T

The morale in the Austrian fleet there excellent although some fear was crawling about the Italian superiority. In gunnery alone, 641 guns versus 532 and far more iron. When the battle started, the Vacca third division (support) was on the north of Lissa, far away from the battle. The Albini group of wooden ships totalled 398 guns, but did not fire a single shot during the battle.

When Persano was transferring his colors and reorganizing his ships, Tegetthoff caught him, spotted the gap opening between the 1st and 2nd Divisions and headed right into it, in ramming formation. On the other hand he allowed his T to be crossed and therefore Vacca’s 1st Italian Division commenced firing while the Austrians could only fire back with their rare chase guns. No general order was given as Persano was in boats just in between flag transfers. The 2nd and 3rd Divisions waited for orders, not firing at first, while the Austrians continued to be pounded, suffering some serious damage. SMS Drache alone on the starboard wing took 17 hits, her mainmast was cut and propulsion stopped temporarily. Captain Heinrich von Moll was decapitated by a shell and Karl Weyprecht took command and had the ship back in action.

At 10:43 am the Austrians were inside the close Italian perimeter, SMS Habsburg, Salamander and Kaiser Max (left wing) splitting to engage the Italian 1st Division, and the Don Juan d’Austria, Drache and Prinz Eugen of the right wing, took the 2nd Division head one. Persano at that stage just reached Affondatore, clear of the engagement. Basically his fleet was headless at that point.

Kommodor von Petz took (2nd Division) went on, exchanging broadside fire on the way, and turned on the Italian rear, falling on 3rd Division. His wooden ships were facing modern ironclads, but nevertheless, he comprehensively engaged them, holding his formation despite taking punishing fire. Screw frigate SMS Novara for example was hit 47 times, captain Erik af Klint killed. SMS Erzherzog Friedrich took a shell below the waterline but resulted fighting, SMS Schwarzenburg eventually was broken and set adrift.

Decisive moment: Ramming attacks

Persano eventually decided to take action with hhis flagship and to steam ahead and ram the wooden ship of the line Kaiser, further away than ships of the fighting his 2nd Division. Kaiser therefore spotted him in advance and had no trouble to dodge the Affondatore. The captain of Re di Portogallo however spotted the admiral move and decided to concentrate fire on SMS Kaiser in turn. Von Petz conducted a counter ram and hit the Italian ironclad hard. Kaiser’s stem and bowsprit were badly hit, the bow’s figurehead embedded in Re di Portogallo. The latter then fired at very close range and disabled both the mainmast and funnel, clearing the bridges also with shrapnel fire. Smoke bellowing from the decapitated exhaust eventually clouded the scene and while Re di Portogallo was manoeuvering for a ramming attack both ships lost sight of each other.

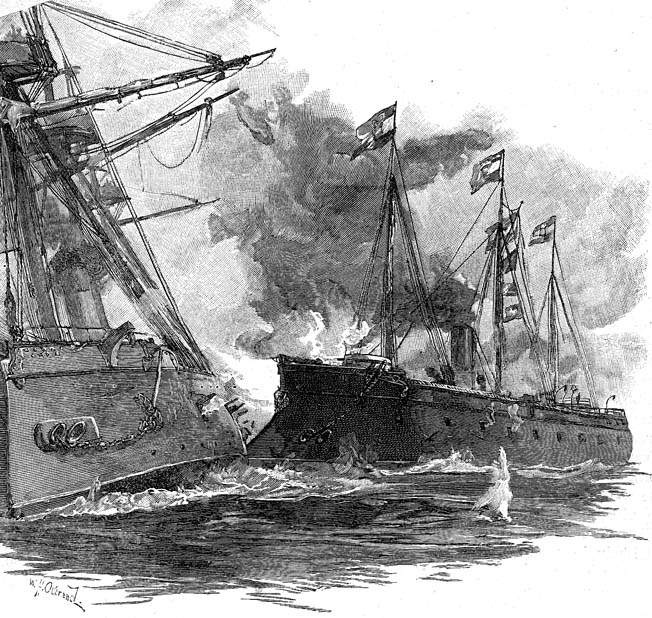

Meanwhile Tegetthoff’s flagship Erzherzog Ferdinand Max (Captain Maximilian Daublebsky von Sterneck) directed his fire first on the Re d’Italia, and then Palestro, causing serious damage. Palestro was dismasted and set alight, almost written off for the rest of the battle. Therefore his captain Alfredo Cappellini pulled out of the line. He ordered his crew to evacuate but the latter refused to abandon their captain and she ships eventually blew up and sank at 2.30pm (19 survivors).

Erzherzog Ferdinand Max was then turning around Re d’Italia, pounding her and turned decisively to ram Faa di Bruno’s ship. She was unexpectedly helped in this by the reverse manoeuver, a failed attempt to avoid the ramming manoeuver. Herzherzog’s ram left a 18 ft (5.5 m) gaping hole below the Italian ironclad waterline. Water rushed in, she struck colours and sank in just two minutes with great losses of life. Faa di Bruno possibly shot himself after the colours were struck according to surviving crew members. His name was honored by the Regia Marina, as posthumous recipient of the Medaglie d’oro, and during ww1 a monitor being named after him.

After this feat, Erzherzog Ferdinand Max made two other ramming attacks, while Ancona, the only ship left of the 1syt division, closed on her to ram her in turn, and her gunners prepared a full broadside at point blank range, but apparently, gunpowder has not been loaded in the confusion of the fight.

Meanwhile, Kommodor von Petz’s ship of the line Kaiser, having cleared off range with Maria Pia was now in the immediate vicinity of Affondatore. Unexpectedly, whereas his wooden ship was a very tempting ramming target, Persano ordered his flagship to turn away. From his position, he estimated the fight was lost and over.

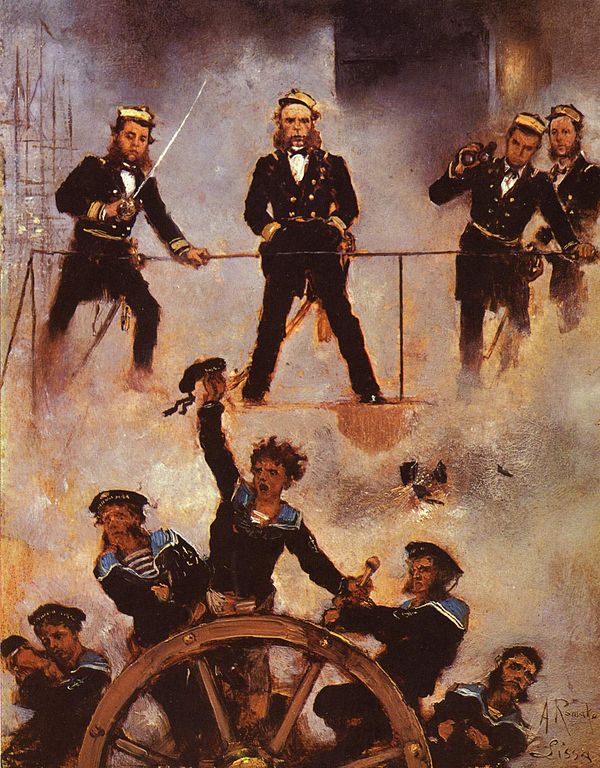

Admiral Tegetthoff during the heat of the battle by Anton Romajko

Victory at hand

Tegetthoff was saluted by his mariners, mostly Croats and Venetians shouting “Viva San Marco!” and at 15:00, the victorious Austrian admiral penetrated into the harbour of Lissa. A badly damaged but victorious Kaiser was already there to greet him. Astonishingly, Italian ships were there too, but both Albini and Vacca ignored Persano’s orders to attack the Austrians. Later this behaviour was confirmed at Persano’s trial. Persano at this point had lost some crew, the remainder being exhausted, was low on coal and ammunition and decided to head for Ancona.

However while the Italians line withdrew, long range fire was still exchanged until it became useless.

Aftermath of the battle

Blame and Fame

Back in Italy, Persano was keen to call the encounter a victory, which was followed by celebrations, at least until news from other officers and sailors came to the surface. There was outrage over the loss of two ironclads, and the scandal went right to the parliament. Persano was judged by the Italian Senate and after commission hearings, condemned for incompetence, degraded, forced to retire and his pension was curtailed.

He was in effect, stripped of his rank and thrown to the national mediatic vindict. Admiral Albini was on his side was also blamed but since he was under orders, only relieved of command. Admiral Vacca only had to retire officially for age limits, and so the Admiralty can get rid of the actor of such embarrassment. Recent history has made a better judgment of Persano, which seemed to have been sufficiently competent for the task and was certainly more experienced than Tegetthoff, although the latter won the trust of his subordinates in the Schleswig War.

Outside his poor decision of swapping flagships at the worst possible time, Persano’s command was plagued by the disloyalty of his Piemontese and Neapolitan subordinates (which also passed all the blame on him at the hearing and trial), with a direct result on coordination in battle, whereas his ships sufferred from poor gunnery skills from the crews and less rifled cannons than the Austrians -therefore loosing in accuracy. The Austrians achieved local superiority by their manoeuver, despite taking risks, like crossing the T of the Italians.

A total contrast of fate as Tegetthoff returned home a hero. Invited by the head of state, awarded numerous prizes he was was promoted Vizeadmiral, and had his name secured for posterity, defining a sense of pride and belonging for the Austro-Hungarian navy which was formed soon after. In 1912, a brand new dreadnought battleship class was named after him.

Strategic consequences

Despite the decisive character of the engagement, it had no immediate effect on the outcome of the war. Indeed, on land, the crushing Prussian victory over the Austrian Army at Königgrätz soon eclipsed the shame of this defeat. Austria, in addition, already bullied by Napoleon III threw the sponge, agreed to cede Venetia to Italy despite Italian unability to get it by military action. Tegetthoff’s efforts were rewarded however as the Italians were dissuaded to land troops on Lissa and therefore were deprived of a strong rear base to assault other Dalmatian islands, once part of the Republic of Venice and which will remain under Austrian control.

Consequences on naval warfare

Ramming as shown in this battle, took a whole new importance in naval warfare. Indeed as guns were mostly inefficient against armour, ships resorted to brute force to dig holes under the waterline and sink their opponents.

This triggered an unexpected return in the admiralties of the ram and ramming tactics. The idea was indeed forgotten since the antiquity, but its return was logical on one account: Like ancient galleys which used rowers to stay independant from the wind and moderate their speed as will, in this new industrial, human power was replaced by steam power. Ships, and especially major naval warships since 1850 had been transitioning from sail alone to a mixed solution (which will carry on at various degree until 1890); Sail and steam.

Sail as a safety, and steam which allowed to double the speed of a ship independently from its position towards the wind. This allowed in effect complex, free manoeuvers and enabled ramming tactics once more. In addition, this idea was particulary seductive in naval circles as it coincided with a Romantic return to antiquity in art, fashion, and new found historical interest for the ancient past (like archaeology which boomed at that time).

Therefore naval designers were pressed over the next fify years to integrate ram bows in all their future warships, especially the largest ones like battleships and cruisers. Inded the idea of a superior size and mass effect was about the same that motivated ancient hellenistic rulers when asking for their giant galley. Some designers were even compelled to create specially designed ships which became a class on their own: The torpedo-ram.

In the 1870s major countries like UK and France and others developed the idea of semi-submersibles ships: Surrounding water as a buffer, a cylindrical-section armored hull on which projectiles would bounce over, and steam power alone aplenty with large rudders to ram at will. The fad was short but created interesting ships like the French Taureau (“bull”) class and British Polyphemus.

However this also carried an unforeseen consequence during exercizes. This truly aggravated a number of incidents, collisions that could have created les harm, should a ram was not implied. But with it, a damaged ship would certainly sink. The most famous example ever perhaps, was the loss of HMS Victoria (1887), the pride of the Royal Navy at that time.

A radical, steam-only heavy guns turret ship, she was rammed in accident by HMS Camperdown near Tripoli, Lebanon, during manoeuvres and quickly sank. By sinking so fast she carried with her 358 crew members including the commander of the British Mediterranean Fleet, Vice-Admiral Sir George Tryon. In addition ramming never featured as a viable battle tactic again, at least in the scale of lissa.

There has been however many example of hostile had oc ramming when the situation arose. We can cite as an example, HMS Dreadnought that rammed and sank the German submarine SM U-29, (captain K/Lt Otto Weddigen the same that commanded U-9), avenging the loss of three British armoured cruisers, on 18 March 1915. Ramming submarines, half-blind, became a favourite tactic for escorts and there has been countless examples of that.

The specialized P-Boats submarine chasers had been designed with a reinforced bow for just such task. Events such as these ocurred again in WW2 in some occasions, although no destroyer escort of frigate has ever been designed for suhch extreme tactic, left to the appreciation of the captain each time. Damage indeed could be for the ship, especially the light ones (like Flower class corvettes), hazardous up to fatal, with long repairs at hand. Some authors also argues that this late XIXth century fixation on ramming may also have inhibited the development of gunnery, just like partisans of cavalry insisted to the virtues of the massed charge in 1914.

At Lissa however the role of the ram has been far too overrated for modern authors: In fact, only one ramming manoeuver succeeded, and only because of the unfortunate move of Captain Faa di Bruno, which stopped his ship dead and easily exposed his flank. All the other ramming attemps failed and the battle was largely decided by gunnery skills and performance.

Nowadays, modern commentators and authors agree that this battle in particular was stuck into a freak technological transition phase. This was a period of weapons development when armour was considerably stronger than the guns available to defeat it. Guns which were still for the most, muzzle-loaded and not rifled, firing in addition still crude projectiles at low velocities. One could add that on the Italian side, poor gunnery training was to blame on better results on the Austrian part which in addition had been deprived for some of their ships like the famous Ferdinand Max without their full armament, a result of the Prussian embargo.

One can only be amazed by the SMS Kaiser, a traditional -steam-powered- ship-of-the-line, which only armor was made of several layers of wood, like man-o-war two hundred years ago, and yet managed to duel with four ironclads at close range, partially repaired overnight, and still reported ready for duty the morning after the battle. This feat had been unprecedented and would remain so in the annals of history. That event alone, and what followed, made the battle of lissa a true landmark in naval warfare, and a mandatory chapter studied in all naval academies.

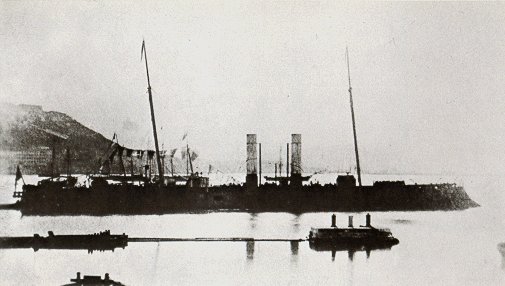

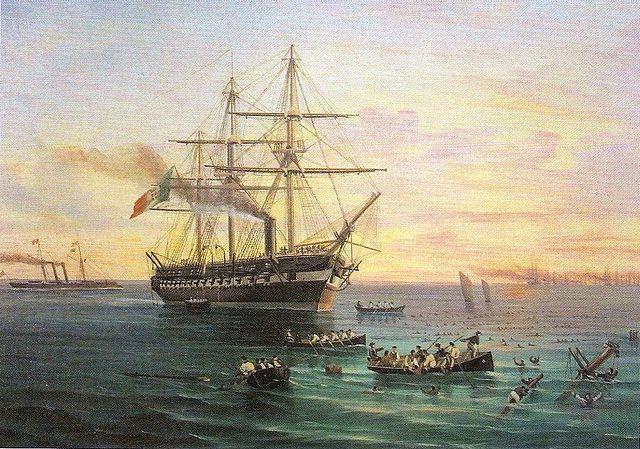

The Regia marina at Ancona after the battle

The Regia marina at Ancona after the battle

Read More/Src

https://www.jstor.org/stable/1874536?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

John Gardiner Conway’s all the world”s fighting ships 1860-1905

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marina_del_Regno_di_Sardegna

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battaglia_di_Lissa

https://www.uow.edu.au/~morgan/lissab.htm

https://www.lingq.com/lesson/lissa-1866-315834/

https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/europe/at-kuk-kriegsmarine-lissa.htm

http://www.catchthispilum.com/july-20th-1866-battle-lissa/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vis_(island)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Battle_of_Lissa_(1866)

https://forum.worldofwarships.eu/topic/8761-battle-of-lissa-1866-a-new-look/

1860 Regia Marina vs

1860 Regia Marina vs 1860s KuK Kriegsmarine

1860s KuK Kriegsmarine

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign