Peruvian Navy Ironclad built 1864-66, sunk 1879

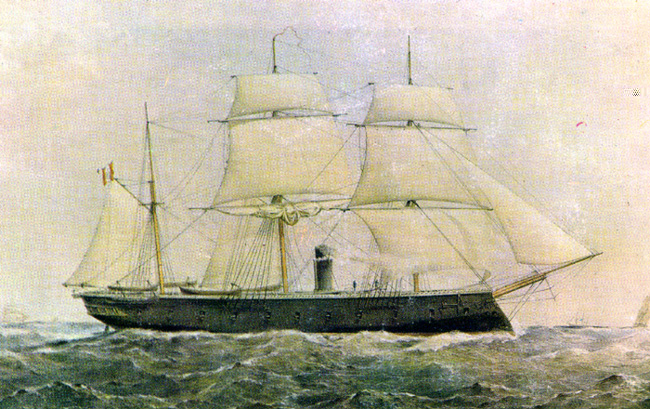

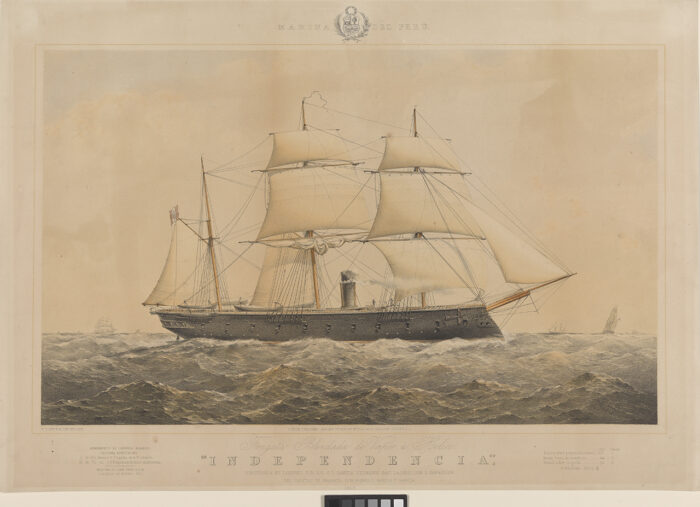

Peruvian Navy Ironclad built 1864-66, sunk 1879 Peru Day ! BAP Independencia was a modest broadside ironclad frigate (Spanish “Fregata Blindada”) built in Great Britain for the then still young Peruvian Navy in 1864-65. She had a relatively uneventful career until the War of the Pacific of 1879–83, when she saw combat the first year. She met her fate at the 1879 Battle of Punta Gruesa, running aground while pursuing the Chilean schooner Covadonga on 21 May 1879. Survivors were rescued by Huáscar and the wreck destroyed to prevent capture.

Peru Day ! BAP Independencia was a modest broadside ironclad frigate (Spanish “Fregata Blindada”) built in Great Britain for the then still young Peruvian Navy in 1864-65. She had a relatively uneventful career until the War of the Pacific of 1879–83, when she saw combat the first year. She met her fate at the 1879 Battle of Punta Gruesa, running aground while pursuing the Chilean schooner Covadonga on 21 May 1879. Survivors were rescued by Huáscar and the wreck destroyed to prevent capture.

Development

The idea of purchasing armored ships came from President Ramón Castilla in 1862. He commissioned Federico Barreda in the US for this task, negotiating with John Ericsson to purchase some now surplus Passaic-class monitors for 400,000 pesos, but this did not materialize as the Peruvian Congress refused to fund them. One faction argued they were not fit for the high seas.

On July 10, 1863, a Spanish “Scientific Expedition” arrived in Callao with several warships of the Armada, the frigates Triunfo with many specialists to conduct all kinds of studies in the countries visited but well escorted by the frigate Resolución, schooner Vencedora and protected gunboat Virgen de Covadonga, together far superior to the Peruvian fleet or even the British or French vessels present at the time in the Pacific. This Expedition came with secret instructions support any claim presented by Spaniards along the way. Admiral Luis H. Pinzón was instructed to be with Peru for its refusal to pay its independence debt. The Armada was at Callao in December.

Peruvian General Juan Antonio Pezet’s government deciding to send a commission to Europe to build two ironclads and face a possible war with Spain, already imminent, or quell any foreign interference. The other one was a modern turreted ship, the famous Huascar. In January 1864, Lieutenant Commander Aurelio García y García and First Lieutenant Miguel Grau sailed to Britain and signed a contract for the construction of two ironclads in March, but due to lack of government funds, it was potsponed in May, with the construction of Huascar pushed back to June for a total 169,454 pounds sterling, making the first ironclad, the most expensive Peruvian warship of the 19th century.

Design of the class

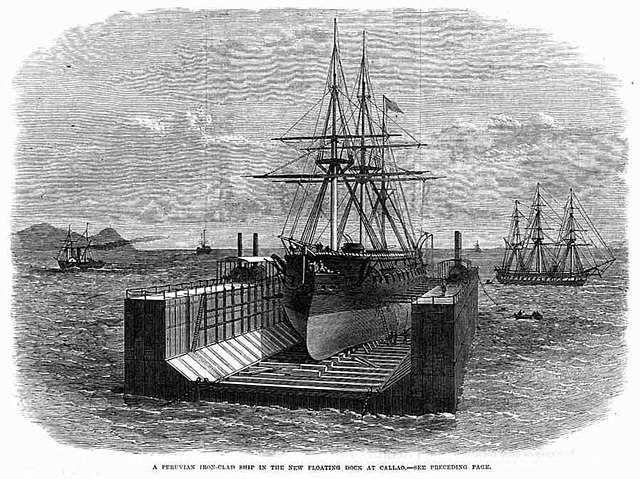

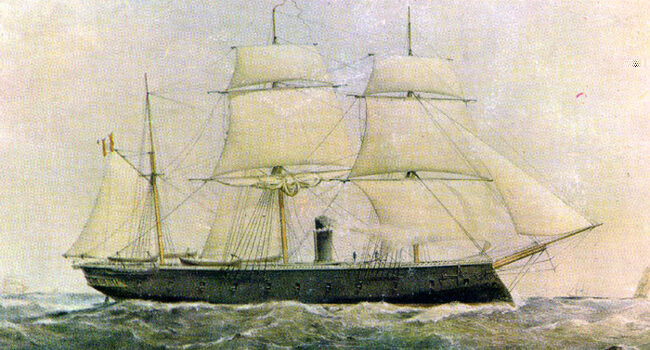

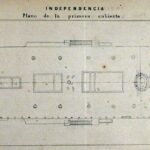

Independencia was ordered in 1864 to boost the Peruvian navy in sea-going defence capabilities, since her only capital ships at the time were the monitors Atahualpa, purchased after the end of the civil war with BAP Manco Cápac, both ex-Canonicus class. They were impressive ships that changed the naval balance of power in South America, until then detained by the Empire of Brazil. But were not enough to counter Spain. The admiralty argued the case for a projection outside river and shores, notably to lead an effective defence out at sea and other roles reasonably far from home. She was ordered after delegations were sent in Britain and France, but the British one sealed the deal. Two new ships were built, including Independencia by Samuda Brothers at Poplar Shipyard in London after a design proposed by the yard and somewhat influenced by ironclads built for the Royal Navy such as HMS Hector, scaled down, but with many differences.

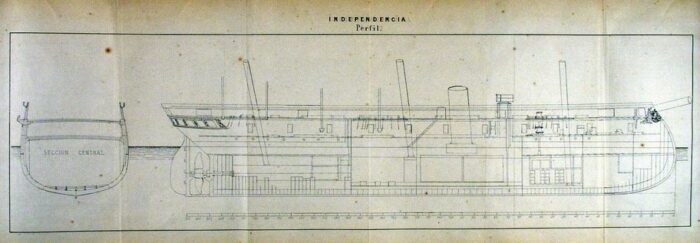

She was an iron-hulled, barque-rigged ship with a ram bow, single fixed funnel, fixed propeller, two main guns on pivot mounts on the weather deck and her main armament or MLRs in the battery, too long to be considered as a central battery. She was a central battery ironclad, even though not all authors agrees on the qualification. Conways for example and many other sources class her as a broadside ironclad, due to the battery deck being too long and with too much “light” guns and protection too spread out for a true central battery. Let’s cut it to saying she was a more of an hybrid. Furthermore, she was laid down in 1864, still a time of transition, launched on 8 August 1865, completed in December 1866. Many broadside ironclads were still built at the time. She barely managed her top speed on trials, but on the long run, her machinery degraded so much she had her boilers replaced in 1878. In February the next year, with war looming on the horizon, she was rearmed (see later).

Hull and general design

Independencia was small for British standard, rather a coastal ironclad displacing 3,500 long tons (3,600 t) versus 10,000 for some 1st rank British ones, but still affordable enough for Peruvian needs. She measured 215 feet (65.5 m) long between perpendiculars, for a beam of 44 feet 9 inches (13.6 m), making for a ratio of 5, and a generous draft of 22 feet 6 inches (6.9 m). The latter was an issue for a coastal battleship and indeed the main reason of her demise, but at the time, Samuda Bros. took the usual calculation for stability used for other British ironclads. She was after all not a monitor, but a sea-going masted ship.

Powerplant

Independencia had a single trunk steam engine driving a single 2-bladed propeller. This powerplant was provided by the steam from two boilers. This powerplant was rated for 2,200 indicated horsepower (1,600 kW) for a top speed of 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph), that was met on trials. This was complemented for long voyages by her barque rig, on three masts. Her crew amounted to 250 officers and crewmen.

Protection

Independencia had a reinforced ram with a bow in the French style, plough type. She also had a complete waterline armor belt 4.5 inches (110 mm) thick and her battery deck was protected by armor plates equally as thick, on a relatively long distance, reinforcing the idea of a broadside ironclad. Underwater, her protection consisted of three watertight compartments, notably one comprising the machinery, another forward and another aft.

Armament

The ironclad frigate comprised two Armstrong 7-inch (178 mm) and twelve 6-inch (152 mm) or 70-pdr as well four 30-pounder rifled, muzzle-loading guns. This too, advocated for a broadside ironclad. She would have been a central battery one with less guns, but of heavier caliber, for example two 7-in on deck, and four 7-in completed by four 6-in in the central battery.

The ironclad frigate comprised two Armstrong 7-inch (178 mm) and twelve 6-inch (152 mm) or 70-pdr as well four 30-pounder rifled, muzzle-loading guns. This too, advocated for a broadside ironclad. She would have been a central battery one with less guns, but of heavier caliber, for example two 7-in on deck, and four 7-in completed by four 6-in in the central battery.

All four 7-inch guns were on pivot mountings on the spar deck, and the topwith probably imposed Samuda Bros. some calculations pleadings for a larger draught to compensate and keep a reasonable center of gravity and metacentric height. Some authors would still argue she was a central-battery ironclad due to her armament “concentrated” amidships, but overall it just does not stick. All these guns were engraved the motto, below the Peruvian coat of arms, “Honor y Patria”.

2x Armstrong 7-inch RML (150 pdr): 129.85 inches long for 15,680 pounds fore and aft.

12x 6-inch RML (70 pdr): Armstrong 6.4-in exact caliber, 126.5 in long, 9,000 pounds each.

4x 30 Pdr RML: No data

2x 9-pdr: 3 inches caliber and weighing 650 pounds each.

1872 and 1878 Rearmaments

Her armament was gutted in 1871. In 1872, when Aurelio García y García received command she was re-armed and four 32-pound smoothbore cannons, a solution mostly adapted to coastal bombardment.

Due to the possibility of war with Chile, two Gatling machine guns were added on deck. One of the 300-pounder 10-inch Armstrong cannons on Callao was placed on her bow but removed on March 18, 1879, replaced with a more manageable 9-inch caliber Vavasseur rifled cannon (232-pounder) with a range of 4,300 m.

A 150-pound Parrott cannon was placed on the stern and the central battery remained unchanged.

The armament thus was reinforced by a single 9-inch (229 mm) rifled, muzzle-loading pivot gun at the bow, and a 150-pounder Parrott gun at the stern on a pivoting mount. To be precise, her French Vavasseur 250-pdr was on the main deck, completed by a US Parrot × 150-pounder on the main deck and completed by her former Armstrong 7-inch (178 mm) rifled, muzzle-loading guns, 150 pounders relocated at the bow and she still had her full batery of now obsolete twelve Armstrong 6-inch (152 mm) rifled 70 pounder muzzle-loading guns on the gun deck.

She also still had her two 9-pounder guns for her boats completed now by two 0.44 cal Gatling gun for landing parties.

Unfortunately, that change of artillery at the bow meant lost flexibility due to muzzle flash, blinding sight of the target, so she had to change course for engage it again. Due to the weight of the new cannon, it could not be traverse, and needed the 5 tons bowsprit to be removed to save weight, dreading her sailing abilities. Two former 9-pounder Armstrong remained in Callao.

Landing Capabilities

The ironclad was also originally equipped with two 40-foot launches built of mahogany, oak, and beech and rigged with copper, but only one was steam-powered, featuring a rare double propeller. Both were large and could support a 9-pdr gun and machine gun in 1879, but at that stage, they were in poor condition. Captain Juan Guillermo More, left them in Callao on May 15, 1879, for maintenance with their two 9-pound cannons. One was used during Pierola coup. The steam-powered one was armed in mid-April 1880 and took part in the Blockade of Callao, armed by a 5-barrel machine gun aft, 12-pound Fawcet & Preston forward, and a spar torpedo, with a warhead containing 32 pounds explosive, hand-launched. This launch was named BAP Independencia, assigned to the transport ship Rímac, acting as mothership.

⚙ Independencia specifications |

|

| Displacement | 3,500 long tons (3,600 t) |

| Dimensions | 215 ft x 44 ft 9 in x 21 ft 6 in (65.5 x 13.6 x 6.6 m) |

| Propulsion | 1 shaft Trunk steam engine, 2 boilers*, 2,200 ihp (1,600 kW) |

| Sail plan | 3 masts barque-rigged |

| Speed | 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph) on steam |

| Range | Unlimited on sails, c1000 nm steam |

| Armament 1866 | 2× 7-in RML, 12x 6-in RML, 4× 32-pdr RML, 4× 9-pdr (boats) |

| Protection | Belt: 4.5 in (114 mm), Battery: 4.5 in (114 mm) |

| Crew | 250 |

Career of Independencia

To prevent Independecia, still in completion, from being seized by the British Government in the face of imminent war between Peru and Spain, García y García decided to leave Greenhite, where she was still fitting out, on January 26, 1866, with some workers still on board to complete work nearby on the Scheldt River, where her artillery was installed, rigging completed, machinery and smaller boats put in order. On February 17, she sailed for Brest. On February 24, in a convoy with the chartered steamer Thames and brand new ironclad Huascar, she departed for the Pacific. On February 28, Independencia collided with Huascar, as her engine stopped unnoticed by the apparently incompetent watch officer. Damage was light, a glancing blow thanks to avoidance. On May 25, the convoy rendezvoused with the corvette América, anchored in Punta Arenas, then sailed for Ancud, ad joined the Allied fleet on June 6, 1866, then headed for Valparaíso on May 11, 1866.

On August 3, 1866, 35 Peruvian officers resigned in Valparaíso when American Rear Admiral John Tucker was appointed Commander of the Peruvian Fleet. Command of the Independencia was assumed by Frigate Captain José María García. She entered Callao on August 24. After maintenance she returned to Valparaíso on October 26, 1866. She remained there until a revolution in Peru which broke out by September 1867 leading to the resignation of President Mariano Ignacio Prado in January 1868. She returned to Callao and arrived on February 26.

Just a few months later, on January 8, 1869, she arrived at Valparaíso, with part of the delegation carrying the remains of liberator Bernardo O’Higgins from Peru, along with Chacabuco and O’Higgins. An important event was the Huáscar Uprising in 1877. Nicolás de Piérola revolted on the Huascar on the night of May 6, 1877. The government of General Mariano Ignacio Prado formed a Naval Division to subdue Huascar, commanded by Captain Juan G. More, and BAP Independencia (More) and the corvette Unión (Captain Nicolás del Portal), monitor Atahualpa, and transport Limeña towing the monitor.

The Naval Division left Callao on May 11 and joined the gunboat Pilcomayo in Iquique. On May 28, Independencia, Unión, Pilcomayo engaged Huáscar at the Battle of Punta Pichalo, without success. Huascar finally surrendered to the Peruvian fleet on May 31.

Campaign of the War with Chile:

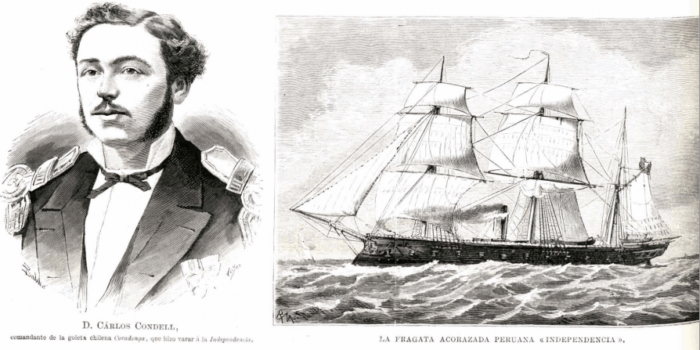

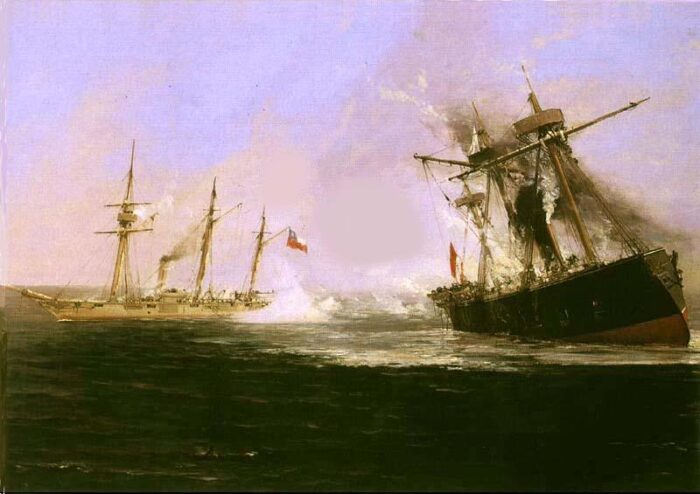

When the war started, Independencia was undergoing maintenance, scheduled the previous year. On May 10, she joined the First Naval Division under command of Captain Miguel Grau, with Huáscar and the transport Chalaco. On May 21, 1879, at the naval battle of Iquique, and the captain made the mistake of downplaying the tactics of Chilean commander Carlos Condell de la Haza. For the start, the later stated to protect her from the Peruvian ship by sailing close to the coast, in shallow waters, aware of the existence of underwater rocks in the area. As a result, she ran aground off the Punta Gruesa peninsula while pursuing the schooner Covadonga, moving south.

Captain Juan Guillermo More Ruiz, attempting to catch the Chilean ship leaving El Molle cove, decided to attack with a ramming attack, believing there were no reefs. The Chilean on purpose sailed very close to the coast and took advantage of the shallower draft, knowing full well about Independencia’s greater draft. However the schooner took more than necessary risks without realizing he was himself sailing in shallow waters. The other factor were the poorly drawn and obsolete Peruvian navigational charts, failing to mention the existence of an underwater reef. The Commander of the Second Peruvian Naval Division, Aurelio García y García, had it noted on the official chart. When the helmsmen failed to avoid the rock, it struck the bottom, shattering plating and causing immediate flooding. She started listing to port, making her it unseaworthy.

The Chilean sailors operated with navigational charts which were updated, and notably one from García y García, corrected by Condell, for the Peruvian and Chilean navies during the campaign against Spain, so they had absolutely accurate information.

Following the Peruvian ship’s mishap, the Chilean commander of the Chilean Covadonga, Carlos Condell de la Haza, reversed course south and, arrived to attack her, taking advantage she was in full evacuation. On this point, there are discrepancies between the versions of Moore and Condell, many contradictions. in the various versions given by Moore himself; according to Condell, the Covadonga approached from the sloping side and shelled the Independencia, forcing the Peruvian ship to surrender, and then fled after spotting the smoke trail of the approaching Huascar; Moore gives two different versions. Condell did not stop firing to rescue the wounded Peruvians and then immediately asserts that there was no surrender, and the stranded ship continued to repel the Chilean attack.

After unsuccessful attempts to surrender Independencia, the old schooner Covadonga fled when spotting Huáscar. The latter starte a hunt for three hours; however but whe the distance grew to 20 km and the interrogation of a captured Chilean sailor, that maintajned that Covadonga could do 11 knots (instead of 5 as believed), Grau decided to return to the island and assist the ironclad. It seeon appeared Independencia could not be salvafed and she was burned out by order of Commander Miguel Grau Seminario. This loss was overshadowed the victory that Huáscar achieved wit the Esmeralda at the battle of Iquique. The Peruvian fleet ended substantially depleted. According to Bolivian historiography, this event also changed the English position, which until then had been inclined to favor Peruvian-Bolivian interests, to shift its support to Chile.

Moore and the surviving crew were on the transport Chalaco, disembarked in Iquique, and sent overland t Arica under command of General Juan Buendía to assist defending that city. Otgher man arrived from the transport Chalaco. Captain Moore could no bear the shame and briefly if he took command of the Monitor Manco Cápac, true to his word, he died atop the hill during the defense of Arica on June 7, 1880. Divers spotted her wreck at Punta Gruesa in 1963, under 12 m. An anchor, cannons, and minor remains were salvaged are are now exhibited in the Naval Museum of Iquique and in Valparaíso.

Read More/Src

Books

Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1979). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1860–1905. page 418.

Greene, Jack & Massignani, Alessandro (1998). Ironclads at War: The Origin and Development of the Armored Warship, 1854–1891. Combined Publishing.

Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World’s Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books.

“Some South American Ironclads”. Warship International. VIII (2). Toledo, OH: Naval Records Club 1971.

Wilson, Herbert Wrigley (1896). Ironclads in Action: A Sketch of Naval Warfare from 1855 to 1895. Marston and co.

Grieve Madge, Jorge (1983). Historia de la Artillería y de la Marina de Guerra en la contienda del 79. Lima: Industrialgráfica S.A.p 220. Cálculo que realiza el autor en base al coeficiente de block.

Historia del Perú, Emancipación y República por Gustavo Pons Muzzo, pagina 174.

Vegas, Manuel (1929), Historia de la Marina del Perú: 1821 -1924. Lima. Talleres Gráficos de la Marina.

García y García, Aurelio (1866). Apuntamientos sobre la fragata blindada “Independencia”. Lima: Tipografía de Alfaro y Cía.

Carvajal Pareja, Melitón (1992). Historia Marítima del Perú, Tomo IX, volumen 2. Lima. Instituto de Estudios Histórico Marítimos del Perú.

Carvajal Pareja, Melitón (2004). Historia Marítima del Perú, Tomo XI, volumen 1. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Histórico Marítimos del Perú. ISBN 9972-633-04-7.

Carvajal Pareja, Melitón (2006). Historia Marítima del Perú, Tomo XI, volumen 2. Lima: Instituto de Estudios Histórico Marítimos del Perú. ISBN 9972-633-05-5.

Grieve Madge, Jorge (1983). Historia de la Artillería y de la Marina de Guerra en la contienda del 79. Lima: Industrialgráfica S.A.

Yábar Acuña, Francisco (2001). Las Fuerzas Sútiles y la defensa de costa en la Guerra del Pacífico. Lima: Fondo de Publicaciones Dirección de Intereses Marítimos.

Links

cavb.blogspot.com/ la-masacre-de-los-naufragos-peruanos

archive.ph/ oocities.org/ grau parte moore

https://web.archive.org/web/20070604002152/http://www.marina.mil.pe/historia/buques/independencia.htm

es.wikipedia.org/

commons.wikimedia.org BAP_Independencia

en.wikipedia.org

elmercurio.com

ecured.cu/

grau.pe/ el error de tres timoneles decide la suerte de la independencia/

members.tripod.com independencia.html

www.facebook.com/ Museos avales Peru

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign