Royal Navy Broadside Ironclads: HMS Warrior, HMS Black Prince 1859–1862, service until 1902

Royal Navy Broadside Ironclads: HMS Warrior, HMS Black Prince 1859–1862, service until 1902

The start of the ironclad age, before the name “battleship” and “capital ship” took over, started in 1860 and lasted until steam-only steel ships became the norm. For more than a decade, the flourishing of ideas and technologies was unprecedented, at a time most navies still counted vast fleets of sailing frigates, corvettes and ships of the line dating back for some to Napoleonic time. A century-old tradition defined by gunpowder and sailing power was about to be shattered, starting in the 1830s with the slow catching up of steam, and then the first breech-loading and rifled guns. The start of the ironclad started in Western Europe, in 1859, between arch-rivals, France and Britain. When unveiled, Gloire launched in 1859, was a wooden frigate armoured with wrought iron. It was immediately answered by Britain, well informed on these progress. In December 1860 was launched HMS Warrior and three months later, HMS Black Prince. They dwarved the Gloire by tonnage and introduced an all-iron construction setting up immediately a new standard. They were indeed the first ocean-going ironclads with iron hulls ever constructed. Both were the first of about 30 steam ironclads, keeping the Royal Navy stronger than the two next most powerful navies combined, and dominating the game for two decades. As for the trailblazers, Warrior (preserved) and Black Prince had a pretty uneventful career, in reserve already in 1875-78 but still around for many years.

Development

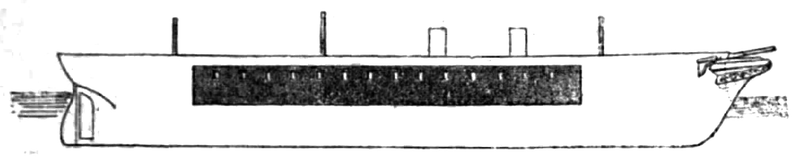

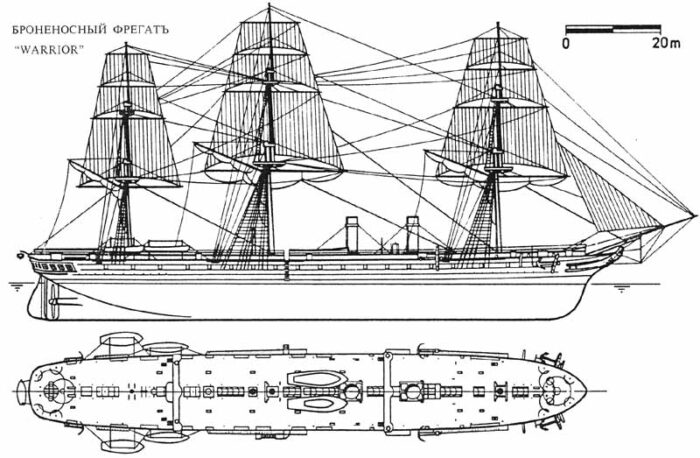

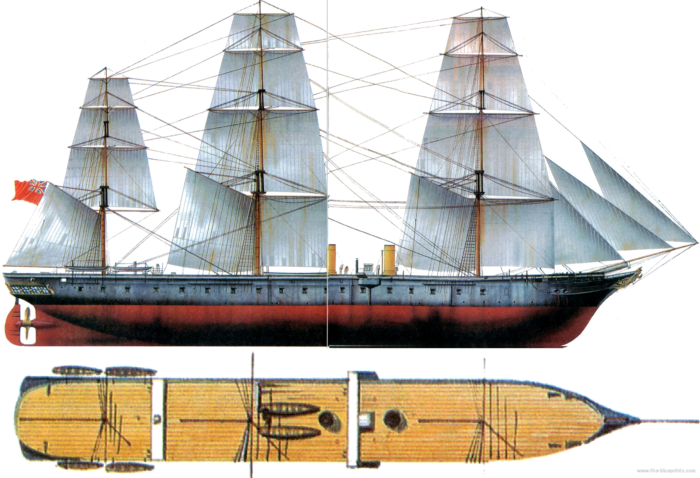

Author’s illustration of the HMS Warrior.

The development of ironclads could trace back its roots to the antique Roman Galleys and their reinforcements of their wooden hull with iron or bronze plates creating an early belt as they were unwieldy, slow and under threat of the ramming tactics of their agile adversaries. In the 1500s inb their struggled against the Japanese, the Koreans created a few “turtle ships” which extensive protection made them early contenders as well. However it’s really the Crimean war and use for the first time by the French of ironclads floating batteries to deal with Russian forts that really sparked the idea. There was already steam, so this was the next innovation in naval warfare. The question remained who built them first. Soon after Gloire and the Warriors, the first sea-going ironclads, on the other side of the Atlantic, the southerners started work on their first converted casemate ironclad, CSS Virginia, former USS Merrimack, to which the union answered with the first turreted steam-only ironclad, USS Monitor in 1862. There were two alternative designs in the ironclad family, which moved for broadside to central battery, and turrets, from extensive rigging to steam alone.

Back in 1858 and British Intelligence were perfectly aware of Dupuy de Lôme’s work (on Napoleon already in 1850, first steam powered ship of the line) on several ships and in 1858 when started the conversion of a steam screw frigate into an ironclad, it was the start of the British own ironclad program. There was a bit of “invasion scare” still at the time, although Napoleon III was reputed far more Anglophile than his uncle. The British admiralty ordered for its 1859 programme anyway the construction in emergency of two massive ships, twice the displacement of Gloire (at 9,300 tonnes versus 5,630 tonnes) and built near entirely in riveted steel, with twice the output of French ironclad, a single shaft Penn HSET engine, ten rectangular boilers for 5,267 ihp at 13.6 knots for Warrior and 14.08 knots for Black Prince, compared to Gloire’s HRCR engine rated for 2,500 ihp and 13 knots.

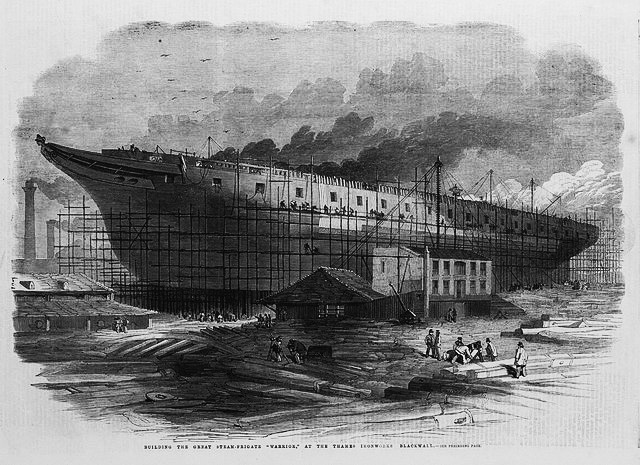

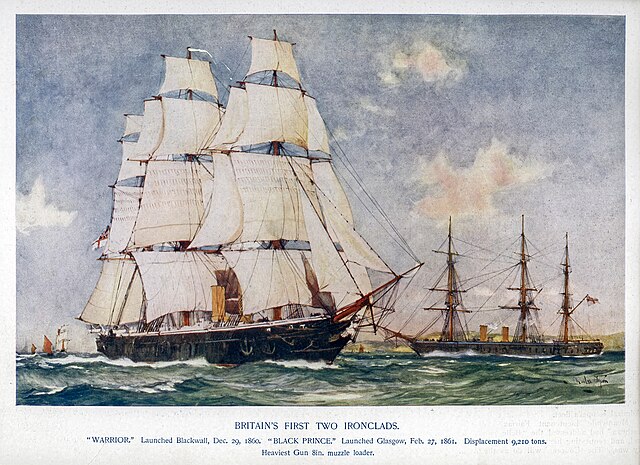

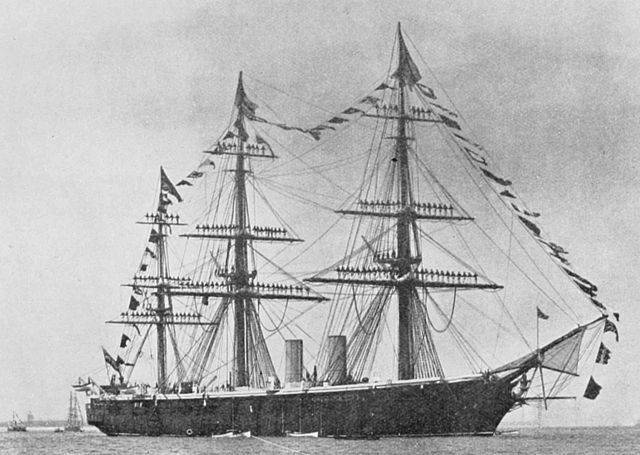

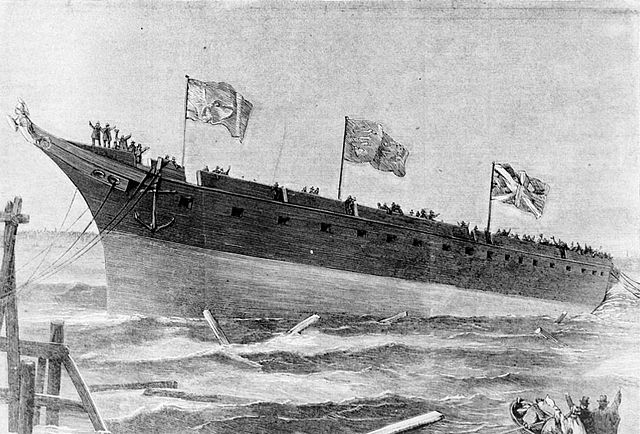

When revealed to the public, both ships were launched in December 1860 (HMS Warrior) at Ditchburn and Mare Blackwall Naval Yard and in February 1861 at Napier of Glasgow for HMS Black Prince. They both became the largest fighting ships afloat. “Fighting” as indeed prior to that, a certain Isambard Brunel created monsters of ships, the Great Britain and Great Eastern. The Warrior class dominated the first generation of French ironclads head and shoulders, and not only by indiustrial ouput, being built from scrach faster, but also they were fitted with a more impressive artillery, with no less than forty 68-pdr Smoothbore cannons versus thirty-six 6.4 in Rifle Muzzle Loaders on Gloire. This was changed during construction to ten even more impressove 110-pounder Breech loading guns and still twenty-six 68 pounder BL as well as four 70 pounder saluting guns.

Design of the class

Hull and general design

They were essentially an evolutionary, rather than revolutionary design. Naval architect and historian David K. Brown commented:

What made Warrior truly novel was the way in which these individual aspects were blended together, making her the biggest and most powerful warship in the world.

They were designed in response to Gloire yet very different in concept of operation, and true replacement for wooden ships of the line, something the smaller industrial capacity of France could not do as much. They were designed by Chief Constructor of the Navy, Isaac Watts. Essentially 40-gun armoured frigates, but made for speed and based on the fine lines of the large frigate Mersey. Warrior and Black Prince were not meant to join the line of battle as many still doubted her ability withstand concentrated fire from three-deck ships of the line. Instead they were the forerunner of battlecruisers, forcing battle on a fleeing enemy and control the battle range at at their own advantage. They were essetnially massive all-iron “super-frigates” somethwat reminiscent of the late 1700s USN frigates.

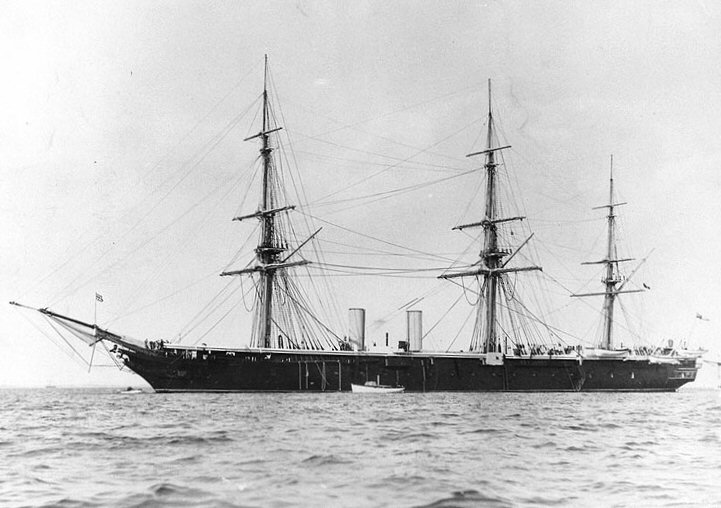

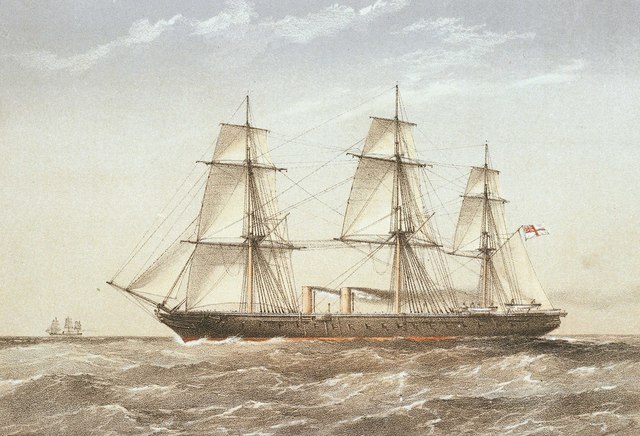

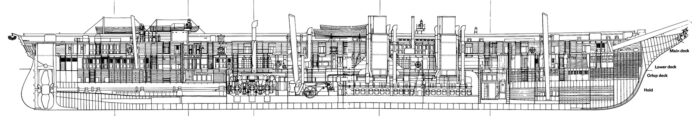

They ships had for this a high lenght-to-beam ratio and fine lines, so they were quite fast but had poor agility. Not only both warships were impressive from outside with their clipper lines and huge dimensions, but the refinement of the officers’s mess and admiral and captain rear saloons were quite impressive. They measured indeed 420 ft (128 m) overall, which already was considerable, or 380 feet 2 inches (115.9 m) long between perpendiculars, for a beam of 58 ft 4 in (17.8 m) and a draught of 26 ft 10 in (8.2 m). For comparison, the largest wooden ship of the line ever built, HMS Victoria, measured 260 ft (79 m) between perpendiculars, not counting the bowsprit. Even with it, the Warrior were much longer.

They had two bilge keels for the first time in the Royal Navy, a innovation that significantly reduced their roll. Still, they were sluggish while manoeuvring, Warrior colliding with Royal Oak in 1868. They had the tendency also to be trimmed down by the bow, between their 40-long-ton (41 t) iron knee at the bow just for shape but this prevented them from ramming. The bowsprit was shortened after completion as well to reduce the trim, but not efficient.

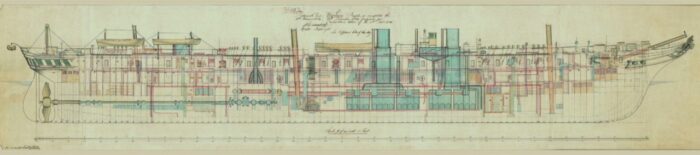

Protection

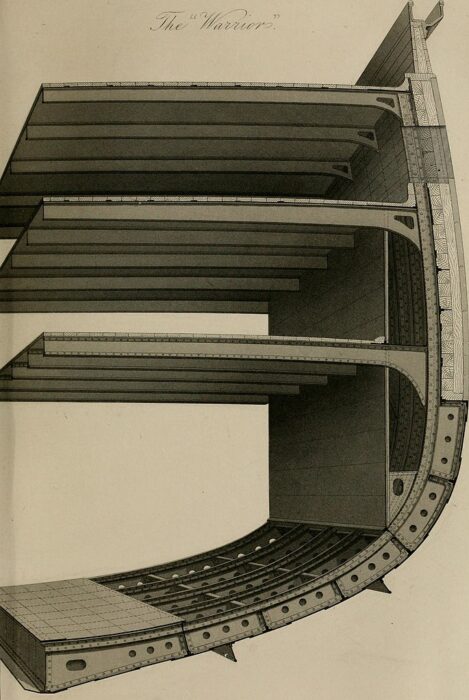

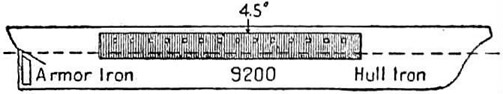

Cross-section of bulkhead armour.

Their armour belt was 213 feets long by 22 feet deep, made of iron plates 15 feets by 3 feets, 4 tons each. They were tongued and grooved to give mutual support, if hit. This was a fine idea, but a complex and costly process and therefore it was not repeated in later ships. This belt extended 16 ft (4.9 m) below and 6 ft or 1.80 m below the waterline. The bulkheads were of the same thikness, protecting the battery from raking fire. As usual, the iron plating was backed by 16 inches (410 mm) of teak.

The unarmoured ends were bilged without loss in stability, but there was no protection over the steering compartment. However, the hull was subdivided into 92 compartments and there was a double bottom for 240 feets of the total lenght. All of these could have been filled with coal if need be. The gun ports, which soze changed over time, were protected around by 7 inches (178 mm) of wrought iron.

The armour plates were also fixed using a new method at the last minute, with tongue and groove joints to lock them together, increase collective resistance to AP fire. shells. This delayed their completion, a year past contract completion date.

Powerplant

They were given each a 2-cylinder trunk steam engine, manufactured by John Penn and Sons. It was driving a single 24-foot-6-inch (7.5 m) two-bladed propeller. Low-rev very large propellers were the norm back then. Propeller shape was later modified to keep up with the ever-improving shaft revolutions. This machinery was fed by the steam provided by ten rectangular boilers working at an amazing pressure of… 20 psi or 138 kPa, 1 kgf/cm2. This made up for a total of 5,267 indicated horsepower (3,928 kW). They became thus, the most powerful warships. On sea trials in October 1861, Warrior reached 14.3 knots (26.5 km/h; 16.5 mph) but Black Prince ended at 13.8 knots. If they carried both 800 long tons (810 t) of coal for 2,100 nautical miles (3,900 km; 2,400 mi) at 11 knots (20 km/h; 13 mph), this was almost an afterthought, intended to the combat itself.

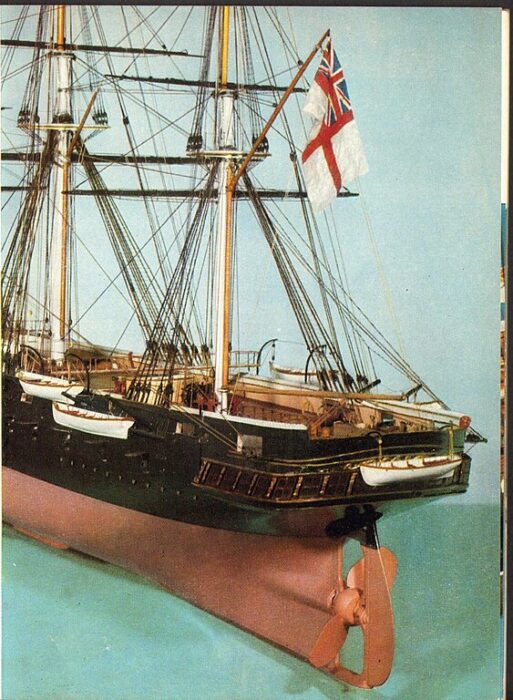

For longer range travel, these ironclads indeed were intended to go under full sail, and were rigged in consequence, with a sail area of 48,400 square feet (4,497 m2). This was little when comparing sail ratios with contemporary clippers, especially given their size and bulk. The lower masts were made of wood, the upper masts in iron. HMS Warrior was later tested under sails and performed well at 13 knots (24 km/h; 15 mph) but Black Prince not so much, only reaching 11 knots (20 km/h; 13 mph). When combining sail and steam, Warrior reached up to 17.5 knots (32.4 km/h; 20.1 mph). The funnels were semi-retractable in order to reduce wind resistance under sail whereas the propellers could be hoisted up into the stern in order to reduce drag for the same optimal performances. Due to their size and weight, they would remained the largest hoistable propellers ever. Using capstans, they required 600 men working in concert, using the two-storey capstans fore and aft, not using steam power, judged too weak.

Armament

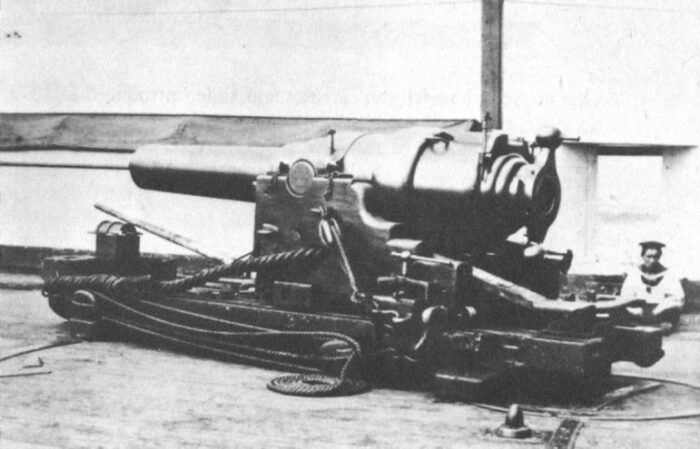

68 Pdr smooth-bore guns

They were initially armed with a mix of rifled breech-loading and muzzle-loading smoothbore guns. However the Armstrong breech-loading guns proved unreliable.

The original 40 smoothbore muzzle-loading 68-pounder guns plannedwere split in two broadsides of 19 on the main (covered) battery deck. There were one each fore and aft as chase guns, on the upper deck. During completion it was estimated this was no longer relevant and instead, modified to ten rifled 110-pounder breech-loading guns installed on the broadside, four either side, remainder as chase guns, with the outer battery made of twenty-six 68-pounders still, giving up fourteen. Four rifled breech-loading 40-pounder guns completed this as saluting guns, remaining in place when it was suggested a replacement by new 70-pounder guns, as they failed their tests.

The gun ports were built 46 inches (1.2 m) wide for a gun traverse of 52°. A directing bar was developed, an iron bar fastened to a pivot bolt located in the sill of the gun port for more precision and after the gun carriages were modified, could pivot closer to the gun port, which could be narrowed to 24 inches (0.6 m), for the same arc of fire.

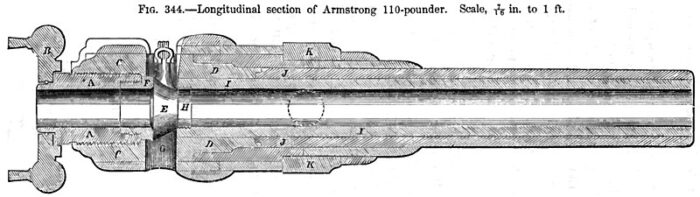

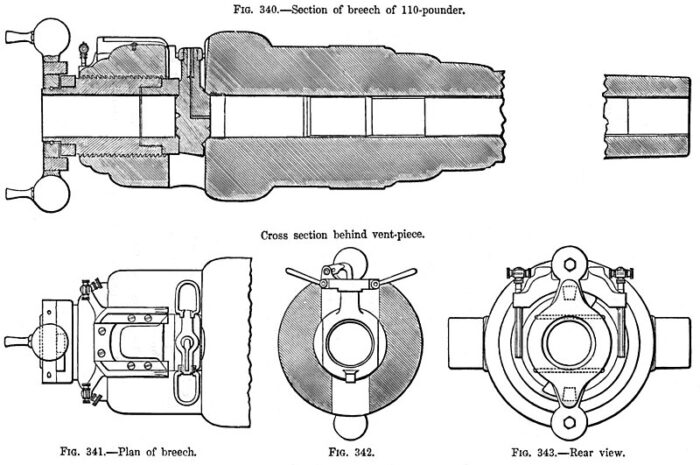

110-pounder guns

These were massive breech-loading guns, new designs from Armstrong, for which many hopes were placed. The core idea was to outrange any ship of the line, which were far better armed with up to 60 guns per broadside. The longer range 110 pounders had no equivalent in the world at the time,and they were the long-range deal breakers. Four were installed on the main battery deck amidships, the other two taking place of the 68 pdrs as chase guns fore and aft, upper deck. They had some extra traverse, placed on rails. These RBL 7-inch Armstrong guns innovated as rifled built-up gun with breechloading proved so far only suitable for small cannon. When scaled up to a 7-inch gun, the pressure required was too much for such breechloading system. So Armstrong “screw” breech mechanism was brought forward, using a heavy block inserted in a vertical slot in the barrel, behind the chamber, leaving a large hollow screw behind it.

Produced until 1864, it was derived frim the 12 pdr 8 cwt field gun, which weighed 72 cwt (8,064 lb) and there was a heavier 82 cwt (9,184 lb) version, which incorporated a strengthening coil over the powder chamber from 1861. These were seen in action at the Bombardment of Kagoshima and of Shimonoseki in 1863 and 1864 and in the New Zealand Wars in 1864. Firing tests by September 1861 against armour proved however the 110-pounder inferior to the 68-pounder smoothbore in penetration. There were also repeated incidents of breech explosion at Shimonoseki and Kagoshima, so the 110-pounder gun had a short lfe in the British inventory.

Specs:

Barrel: 99.5 inches (2.527 m) bore x 7-inch (177.8 mm) for 14.21 calibres

Shell: 90-109 pounds (40 to 50 kg)

Breech: Armstrong screw with vertical sliding vent-piece block

Muzzle velocity: 1,100 feet per second (340 m/s)

Maximum Range: 3,500 yards (3,200 m).

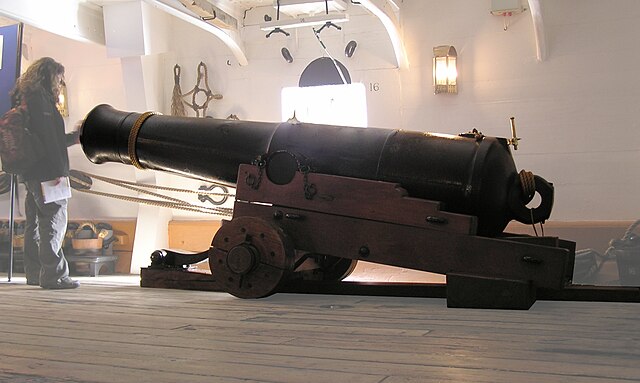

68-pounder guns

All twenty six 68-pounder smoothbore muzzle-loading guns were mounted on the main deck. These older models from 1846 saw action already in the Crimean war, but produced at a time when new rifled and breech loading guns were introduced. They were kept and cohabited with the latter due to their reliability and power, retained until eventually juged obsolete. The surplus stocks of 68-pounders were also converted with rifled barrels, remaining in service until… 1921. Designe doriginally by William Dundas and prduced at Low Moor Ironworks, as cast iron smoothbore models designed to perforate the thickest walls of the time. It was also cheap to produce with over 2,000 made seeing action well after 1872 when converted by Palliser.

Specs:

Mass: 88, 95 or 112 cwt

Barrels: 88 cwt 9 feet 6 inches (2,896 mm), 95 cwt 10 feet (3,048 mm), 112 cwt 10 feet 10 inches (3,302 mm)

Crew: 9–18

Shell: Solid Shot or Explosive, 68 pounds (30.84 kg) 8.12 inches (20.62 cm) caliber.

Muzzle velocity: 1,579 feet per second (481 m/s)

Elevation 15 degrees, range 3,000 yards (2,700 m) up to 3,620 yards (3,310 m)

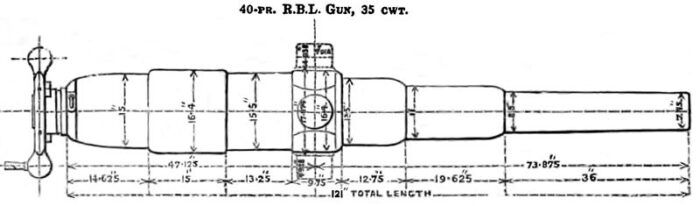

40-pounder guns

Used as saluting guns, they were rifled still, designed recentkly in 1859 by Armstrong and also produced by the Royal Gun Factory. These were land/sea universal guns, placed on horse-drown carriages for land operations, this was no the case on Warrior, which had them in low wheeled deck carriages (photos). Production ceased in 1863.

Specs:

Mass: 32 cwt (3,584 pounds (1,626 kg)), 35 cwt (3,920 pounds (1,780 kg)).

Barrel: 106.3 inches (2.700 m) x 4.75-inch (120.6 mm)

Shell: 40 pounds 2 ounces (18.20 kg), mv 1,180 feet per second (360 m/s)

Armstrong screw breach with vertical sliding vent-piece block.

Modifications

HMS Warrior joined the Channel Fleet in July 1862 and was in and out further trials and refits until 1867. The armament was changed again in the first reconstruction of the ships: They were given twenty-six Smoothbore muzzle-loading 68-pounder guns, ten Rifled breech-loading 110-pounder guns but she kept the four Rifled breechloading 40-pounder guns. The engine was revised again and allowed 14 knots (26 km/h; 16 mph).

Warrior class specifications) |

|

| Displacement | 9,137 long tons (9,284 t) |

| Dimensions | 420 ft x 58 ft 4 in x 26 ft 10 in (128 x 17.8 x 8.2 m) |

| Propulsion | 1 shaft, 1 Trunk steam engine: 5,267 ihp (3,928 kW), +rig |

| Speed | 14 knots (26 km/h; 16 mph) |

| Range | 2,100 nmi (3,900 km; 2,400 mi) at 11 knots (20 km/h; 13 mph) |

| Armament | 26× MLS 68-pdr, 10× BLR breechloading 110-pdr, 4 × BLR 40-pdr |

| Protection | Belt 4.5 in (114 mm), Bulkheads 4.5 in (114 mm) |

| Crew | 707 |

Career of the Warrior class ironclad

HMS Warrior (1860)

HMS Warrior (1860)

Indecision by the Admiralty, frequent design changes caused many delays and nearly cause the builders bankrupcy, so a state grant of £50,000 was awarded. Warrior’s launching date was on 29 December 1860, unfetrunately the coldest winter for 50 years so she frozen to her slipway, requiring hydraulic rams and additional tugs as well as many dockworkers trying to rock her free. She was eventualy commissioned in August 1861 and started her sea trials, completed on 24 October. Total cost had been £377,292, twice that a contemporary wooden ship of the line., and this was without cannons and equipments. From March to June 1862, she reveled many defects which needed to be rectified. She received notably a lighter bowsprit, shorter jib boom plus extra heads amidships.

She entered service at lasy with the Channel Squadron under Captain Arthur Cochrane. By March 1863, she escorted the royal yacht with Princess Alexandra of Denmark to Britain to marry the Prince of Wales. So please she was of the trip she requested Admiral Sir Michael Seymour to have the message passed on to Cochrane, which engraved it on a brass plate, fitted on the steering wheel. The “tradtion” was kept alive by her decendent Princess Alexandra of Kent as patron (1860 Trust).

By mid-1863 she toured British ports for 12 weeks, being visited by 300,000 as much as 13,000 daily in each in port, a record. On 19 September, she rescued survivors of the Mersey Flat Mary Agnes colliding with Snaefell at Liverpool. She ahad a refit by November 1864, with her armament upgraded, recommissioned in 1867, under Captain John Corbett and replacing Black Prince as guardship at Queenstown. Both took part in the Fleet Review of 17 July for the arrival of the Khedive of Egypt and Sultan of Turkey. She was paid off on 24 July and recommissioned a year later under Captain Henry Boys, joining the Channel Squadron on 24 September.

Later she was in Osborne Bay, guarding Queen Victoria at Osborne House, under threat by the Fenian Rising, but receiving an informal visit from the Queen. She escorted also the royal yacht HMY Victoria and Albert to Dublin in April 1868. In August while in Scotland, she collided with HMS Royal Oak, losing her figurehead and jib boom. Captain Boys was court-martialled but acquitted.

4-28 July 1868 saw both, with the paddle frigate HMS Terrible, towing a very large floating drydock for ironclads at a point 2,700 nmi (5,000 km; 3,100 mi) across the Atlantic from Madeira to Bermuda. By late August 1869, Captain Frederick Stirling took command, and after a drydock refit and repairs, she was back with the Channel Squadron. On 2 March 1870, Captain Henry Glyn took command after which she had a joint cruise with the Mediterranean Fleet and was present when HMS Captain capsized on 7 September. She later sailed to Madeira and Gibraltar.

However by 1870 she was already obsolete as in 1871 was commissioned HMS Devastation, the first steam only turreted ironclad. She had a final refit until 1875, gaining a poop deck and steam capstan (remember 600+ to hoist her propellers !) as well as a shorter bowsprit, and new boilers. In April 1875 after being recommissioned, she joined the First Reserve as guardship at Portland, still having annual summer cruises. As the Russo-Turkish War flared up she was mobilised if the Russians managed to attack Constantinople, staying in Bantry Bay. In April 1881 she was in the Clyde as guardship until 31 May 1883. Two masts were removed after inspection, and she was decommissioned and then her rigging removed entirely.

Under the new denomination as “screw battle ship, third class, armoured” in 1887 and until May 1892, when she became a “1st-class armoured cruiser” without any modifications made. She could have receive one in 1894, but judged uneconomical with just a new boiler replaced. She was stricken on March 1900, became a storage hulk until July 1902, modified as depot ship for destroyers, with engines, boilers removed and her upper deck roofed over, compartimented for the crews. She served as such until July 1902, under Captain John de Robeck. In March 1904 she was assigned to HMS Vernon at Portsmouth (torpedo-training school) and herself renamed Vernon III to free her name for a new armoured cruiser. To provide electricity she was fitted with six new Belleville boilers and four electric generators. Her upper deck was modified into classrooms for radio training, fore and mizzen masts reinstalled to hoist the cables. In October 1923, the school was transferred to a shore installation and she was declared redundant, used as oil jetty in Llanion Cove.

Post-WW1 mass scrapping lowered much the demand for scrap iron when she was sold by the admiralty on 2 April 1925. She remained at Portsmouth until 1830 and became a mooring jetty from 22 October 1927. She kept her boilers and generators, plus two diesel-driven emergency pumps added. She had accommodations built for a shipkeeper and his family. Next she was towed to Pembroke Dock in Wales as a floating oil jetty until 1977 at Llanion Cove. Eventually her upper deck was covered by concrete in maintenance before WW2 in which she became a base ship for coastal minesweepers. From 27 August 1942, she became Oil Fuel Hulk C77 to release her name yet again for the new aicraft carrier HMS Warrior starting construction. She refuelled 5,000 ships during her service.

Restoring her was discussed already in the early 1960s, and by 1967, the Greater London Council proposed this to have her converted as an attraction while she was still required in Pembroke by the Royal Navy. In 1968 the Duke of Edinburgh discussed her and other vessel’s oreserviavation, and so was created the Maritime Trust. In 1976 the Royal Navy announced the closure of the Llanion Oil Depot and funds were gathed to restore her. When the amount was secured, the Royal Navy donated her to the trust in 1979. She is the property of the Warrior Preservation Trust since 1985.

The Restoration started in August 1979 at the Coal Dock at Hartlepool under £9 million, funded by the Manifold Trust and later the Maritime Trust decided to have back in her 1862 condition accompanied by intensive research.

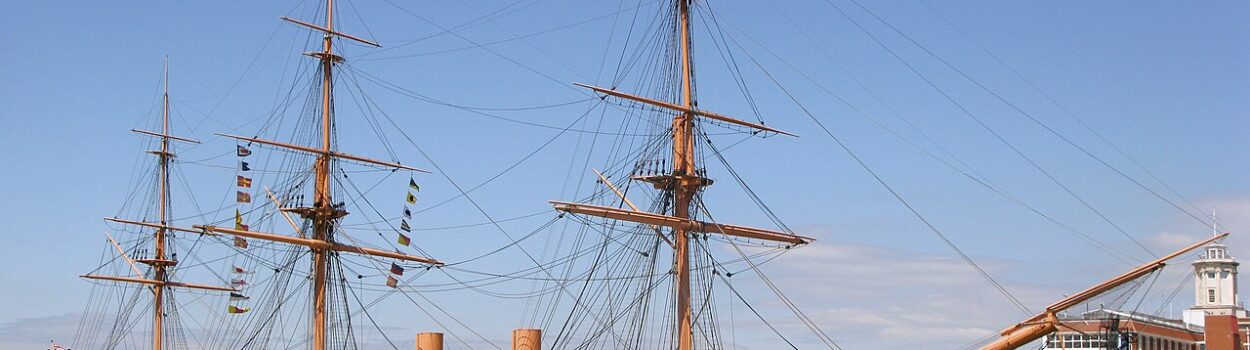

In 1985 a new berth beside Portsmouth railway station was dredged, new jetty constructed for her arrival, leaving Hartlepool on 12 June 1987 under Captain Collin Allen, was towed 390 mi (630 km) to the Solent and welcomed on arrival by thousands from walls and shore, greeted also by a fleet of 90 boats and ships. She opened at last as a museum on 27 July and officially renamed HMS Warrior (1860) to avoid confusion with the Northwood Operational Headquarters headquarters of the Royal Navy from 1863.

She is part of the National Historic Fleet, close to the Portsmouth Historic Dockyard complex, home of Nelson’s HMS Victory, and Tudor warship Mary Rose, as well as the HMS M33. In 1995 she counted 280,000 visitors. In 2017, April, the trust was taken over by the National Museum of the Royal Navy. She is also a venue for weddings to generate revenues for her maintenance.

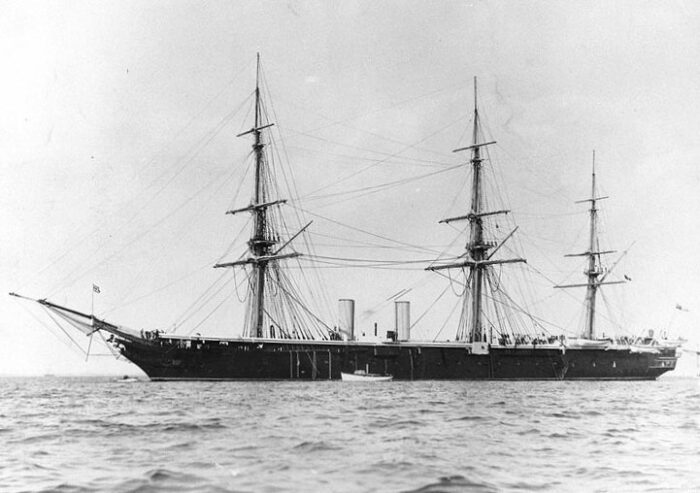

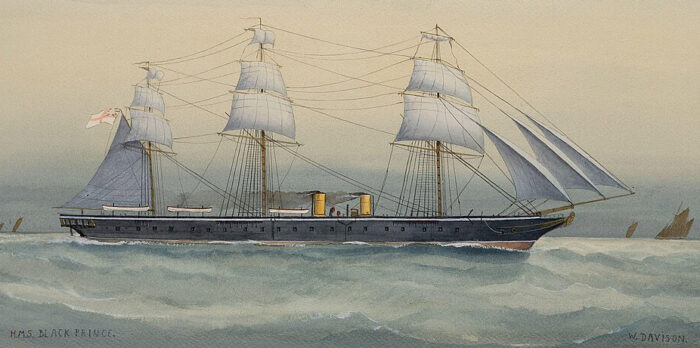

HMS Black Prince (1861)

HMS Black Prince (1861)

HMS Black Prince was ordered on 6 October 1859 from Robert Napier and Sons, Govan, Glasgow, at £377,954, laid down on 12 October 1859, launched 27 February 1861. While towed for completion on 10 March, she ran aground in the Clyde, near Greenock. Then there was a drydock accident at Greenock, damaging her masts. Se was sent to Spithead in November 1861 with minimal rigging on her fore and mizzenmasts before being officiall commissioned in June 1862, and officially completed by 12 September 1862. She served with the Channel Fleet until 1866, and becale flagship on the Irish coast Fleet. She had a major overhaul while being rearmed in 1867–1868 and became a guardship on the Clyde. In 1869 with her sister Warrior she was the only ship powerful enough for towing a large floating drydock from Madeira to Bermuda.

She had her last refit in 1874–1875, like he sister with the addition of a poop deck, and returned to the Channel Fleet as flagship (Rear Admiral Sir John Dalrymple-Hay). In 1878 under Captain H.R.H. Duke of Edinburgh newly appointed she crossed the Atlantic for the inauguration of the new Governor General of Canada. Back home she was placed in reserve at Devonport. Like he sister in the 1880s she was reclassified as armoured cruiser, never modernized but reactivated periodically, taking part in fleet exercises. She was eventually hulked in 1896 and became a harbour training ship anchored at Queenstown, renamed HMS Emerald in 1903 to free the name, and in 1910 towed to Plymouth, renamed Impregnable III, assigned the namesake etraining school HMS Impregnable. At last on 21 February 1923 she was sold for BU. Her sister was abrutply shorter than her sister indeed.

Read More/Src

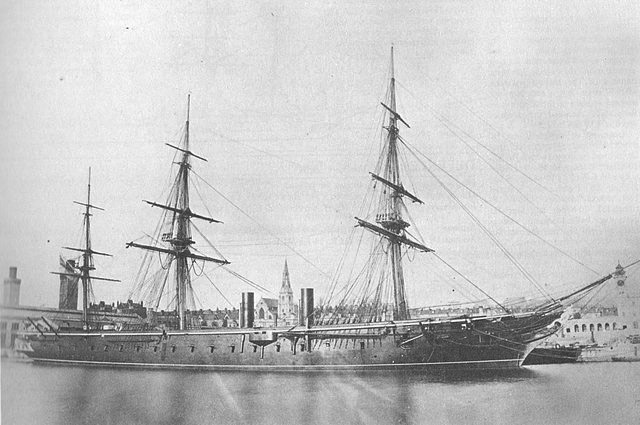

HMS Warrior as built

Books

amazon.com HMS-Warrior by Andrew D. Lambert

Ballard, G. A. (1980). The Black Battlefleet. NIP

Baxter, James Phinney III (1968) 1933. The Introduction of the Ironclad Warship. Hamden, Connecticut: Archon Books.

Brown, David K. (2003) 1997. Warrior to Dreadnought: Warship Development 1860–1905. London: Caxton Editions.

Brown, David K. (2006). The Way of a Ship in the Midst of the Sea: The Life and Work of William Froude. Periscope Publishing Ltd.

Brown, Paul (2009). Britain’s Historic Ships: The Ships That Shaped a Nation: A Complete Guide. London: Anova Books.

Lambert, Andrew (1984). Battleships in Transition. London: Conway Maritime Press.

web.archive.org/ stvincent.ac.uk/

Lambert, Andrew (2010). HMS Warrior 1860: Victoria’s Ironclad Deterrent (2nd revised and expanded ed.). NIP

Lambert, Andrew (1987). Warrior: Restoring the World’s First Ironclad. London: Conway Maritime Press.

Padfield, Peter (2000). Battleship. Edinburgh: Birlinn.

Parkes, Oscar (1990) [1957]. British Battleships. Annapolis, Maryland: NIP

Roberts, John (1979). “Great Britain (including Empire Forces”. Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1860–1905.

Sandler, Stanley L. (2004). Battleships: An Illustrated History of Their Impact. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO.

Wells, John (1987). The Immortal Warrior: Britain’s First and Last Battleship. Emsworth, Hampshire: Kenneth Mason.

Winton, John (1987). Warrior: The First and The Last. Liskeard, Cornwall: Maritime Books.

Links

ww1britainssurvivingvessels.org.uk/

nationalhistoricships.org.uk/

nmrn.org.uk/ portsmouth museum

cutaway on w.flickr.com/

on en.wikipedia.org/

pdavis.nl/

jstor.org/

web.archive.org hnsa.org/ hms-warrior/

wtj.com/articles/warrior/

on dreadnoughtproject.org/

dawlishchronicles.com

thebluejackets.co.uk/

militaryfactory.com/

navalgazing.net/HMS-Warrior

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign