The broadside ironclads with a double life

Austro-Hungarian Navy, 1862-1883: SMS Kaiser Max, Juan d’Austria, Prinz Eugen

Austro-Hungarian Navy, 1862-1883: SMS Kaiser Max, Juan d’Austria, Prinz Eugen

Austrian Fleet |

Austrian Fleet |  pre-WW1 fleet |

pre-WW1 fleet |  WW1 fleet

WW1 fleet

The Kaiser Max class were three broadside ironclads ordered in and later laid down in 1861: Kaiser Max, Prinz Eugen, and Juan de Austria, improved version of the Drache class, launched in 1862, completed in 1863. They were more powerful, better armed and larger, and had different fates: Don Juan d’Austria took part in the Second Schleswig War (1864) and they all took part in the 1866 Battle of Lissa, Kaiser Max managing to ram the Re D’Italia. Modernized postwar they did not see further active service and were deglected, so that by 1873, they were discarded. In the budget-stripped context, the new commander Friedrich von Pöck obtained to “rebuilt” them and instead created three new casemate ironclads with the same names and recycling equipments from the previous shipsn causing some confusion for future naval historians. #austrohungary #austriannavy #kukkriegsmarine #austrohungariannavy #austrohungarian #kaisermax #prinzeugen #lissa

Context: Rivalry with Italy, leading to Lissa

In the 1860s, the Mediterranean was a hotbed of naval rivalty. The recent Regia Marina after a newly found independence grew an immediate, fierce rivalry with the long domination of Austria, now consolidated as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, consolidated in 1867. Before that Austria’s growing Naval might was seen as a threat to Italian interests in the Adriatic sea and beyond.

Until 1859, most Austrian ships were purchased in nearby Venice, but this soon changed as the city also changed hands. With the French Ironclad Gloire showing the way in 1859, there was a sudden race towards broadside ironclads around Europe. It was clear for Austrians present in Italy, that the former was now looking to purchase ironclads in France and the UK, and Austria soon followed suite converting on the spot two large frigates ordered to Trieste, Stabilimento Tecnico Triestino on February 1861 and named SMS Drache and Salamander completed by May and November 1862. They, with the Formidabile, started the Austro-Italian ironclad arms race:

The Austro-Italian ironclad arms race

⚙ The Austro-Italian naval Arms Race prior to Lissa (1864) | |

Regia Marina Regia Marina |  KuK Kriegsmarine KuK Kriegsmarine |

|

Formidabile class 1860 Principe di Carignano class 1861 Re d'Italia class 1861 Regina Maria Pia class (1862) Roma class (1863) Affondatore (1863) Principe Amedeo class (ordered 1865) |

Drache class (1860) Kaiser Max class (1861) Erzherzog Ferdinand Max class (1863) |

Development & Design

After the lauch of the French Gloire, the Austrian Navy launched an ambitious ironclad construction program under the leadesrship of Marinekommandant Archduke Ferdinand Max, brother of The Emperor (Kaiser) Franz Josef I. In 1861, the Drache class, were laid down, with three more ordered, designed by the Director of Naval Construction, Josef von Romako like the first ones, as an improved version of the Drache class, larger with more powerful engines and more guns.

Hull and general design

The Kaiser Max-class ships were 70.78 meters (232 ft 3 in) long between perpendiculars; they had a beam of 10 m (32 ft 10 in) and an average draft of 6.32 m (20 ft 9 in). They displaced 3,588 long tons (3,646 t). Wooden hulled vessels, they proved to be very wet forward and had to have their bows rebuilt in 1867. Each ship originally had a bow figurehead, which was removed during the reconstruction. They were also very unstable ships, pitching badly and having very bad seakeeping. The ships had a crew of 386.[4]

Armour protection layout

It was the same as previous ironclads: Wooden hull, but sheathed with wrought iron armor, 110 mm (4.3 in) in thickness.

Powerplant

Their propulsion system consisted of one single-expansion, 2-cylinder, horizontal steam engine that drove a single screw propeller. The number and type of their coal-fired boilers have not survived, though they were trunked into a single funnel located amidships. The engines were rated 11 knots (20 km/h; 13 mph) from 1,900 indicated horsepower (1,400 kW); on trials, Kaiser Max slightly exceeded those figures, reaching 11.4 knots (21.1 km/h; 13.1 mph) from 1,926 ihp (1,436 kW).[4] Don Juan d’Austria was capable of only 9 knots (17 km/h; 10 mph).[5] They were fitted with a three-masted rig to supplement the steam engines.[4]

Armament

The ships of the Kaiser Max class were broadside ironclads. Kaiser Max and Prinz Eugen were armed with a main battery of sixteen 48-pounder muzzle-loading guns, while Don Juan d’Austria received fourteen of the guns. The ships also carried fifteen 24-pounder 15 cm (5.9 in) rifled muzzle-loading guns manufactured by Wahrendorff. They also carried two smaller guns, one 12-pounder and one 6-pounder. In 1867, the ships were rearmed with a battery of twelve 7 in (180 mm) muzzle-loaders manufactured by Armstrong and two 3 in (76 mm) guns.

⚙ specifications as built |

|

| Displacement | 2,824 tonnes standard, 3,110 tonnes full load |

| Dimensions | 70.1 x 13.94 x 6.8 m (230 ft x 45 ft 9 in x 22 ft 4 in) |

| Propulsion | 1 Shaft, RP Steam engine, 4 boilers, 2,060 ihp (1,540 kW) |

| Speed | 10.5 knots (19.4 km/h; 12.1 mph) |

| Range | Unlimited by sail, c1000 nm or less with steam |

| Armament | 10 × 48-pounder smoothbore guns, 18 × 24-pounder rifled, muzzle-loading guns |

| Protection | Waterline belt: 115 mm (4.5 in) |

| Crew | 346 |

A side note: Recycling capital ships

The “recycling” of the Kaiser Max class is pretty unique as it happened. Some naval historians, based on the existing, well kept official records, believed these ships had been indeed rebuilt. But later works analysing memoirs of Friedrich von Pöck, the CinC of the Austro-Hungarian Navy at the time, made it clear that the “rebuilding” was a scam as the parliament new ships but did not opposed a “rebuilt”. In that case, the hull was new, but the rest came indeed from the older class. On conway’s, there is double entry for the class in page 269-270 of the book. The end status of the first class states “rebuilt Nov-Dec.1873 and Juan de Austria “scrapped in 1886” whereas the new class had different fates.

Not all what equipped the former class was reused. The machinery, 2-cylinder H LP engines were kept but boilers not. New ones were chosen, which rose the output from 1900 to 2755 ihp, but speed was about the same at 13 knots. Also not all the former armour was reused, since some already was rusty. It is likely it was cleaned up and the best plates were concentrated in the casemate. Also some former iron framing used to reinforce the older wooden hull were also kept. But in the end, these conversion appeared thrice as costly as a brand new ships. If in its obstination the Parliament refused new construction to cut corners, this had precisely the opposite effect…

There are any cases of ships recycling. On famous case, for the same navy, was the conversion of the old three-decker Kaiser (1958) which was also completely rebuilt in 1969 as a central casemate ironclad. Not far, Italy was among the nation that, under the constraint of the Washinhton treaty and its “battleship ban”, “recycled” its WWI vintage Cesare and Cavour classes in a very impressive way. Practically everything but the keel was modernized and they ended a bit like prototypes for the new Litorrio class. Britain did the same with three of her five Queen Elisabeth class, and the US with all its dreadnought, with the three New Mexico and post-Pearl Harbour rebuilts being the most impressive. Japan recycled its HMS tiger-copies (the four kongo class) as well, and after two major rebuilt transformed them as fast battleship instead of battlecruisers.

Career of the Kaiser Max class (1862-1875)

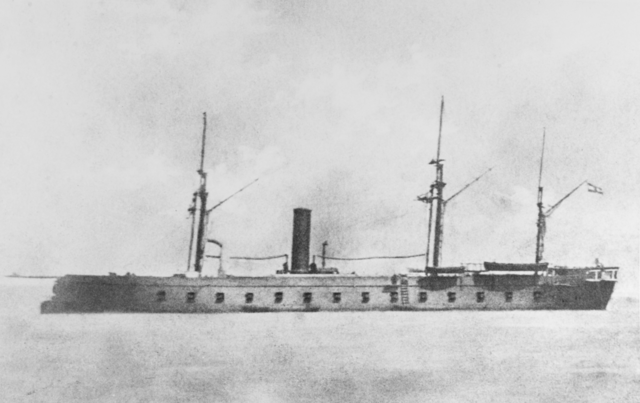

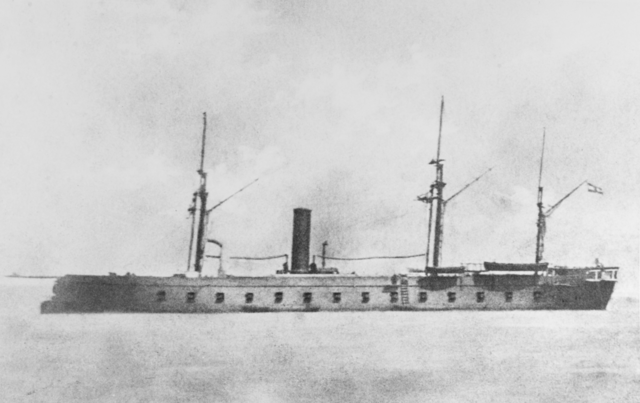

SMS Kaiser Max

SMS Kaiser Max

SMS Kaiser Max after Fitting-out was commissioned in 1863, she was noted as very wet forward (open bow, ram shape) and ploughed heavily in heavy weather and handled poorly. By June 1864, she also collided with the British merchant Rapid off Portugal and damage was severe. Repaired, she resumed service and in June 1866 was plunged into the third Italian War of Independence, at the same time as the Austro-Prussian War. She was part of Rear Admiral Wilhelm von Tegetthoff’s squadron, fully mobilized, prepared, crewed and soon in intensive training off Fasana. She sailed with the rest of the fleett o Ancona on 27 June to lure out the Italians, but without success. The next sortie of 6 July was also unsuccessful. The Italian fleet however under pressure sailed out to attack the island of Lissa under Admiral Persano.

On 18 July, Persano deployed his fleet around the Island in three areas to proceed to simultaneous assault, pounding the defences, with 3,000 soldiers waiting for the order. However for two days his ships tried to reduced the Austrian defenses without success. Tegetthoff, informed on the 17th believed it was a feint until he received confirmation on the 19th, and was authorized to attack. Arriving on the morning of 20 July, he caught the Austrians divided, with the fleet closest to him, anchored and not in battle formation, and the two others too far away to intervene. This was a golden oppurtunity and he rushed forward in a wedge formation, his ironclads at the tip and wooden vessels in the center and rear. SMS Kaiser Max was posted on his left flank.

Persano ordered to rearrange his ships at 10-12 knots, but also requested a small boat to be transferred from Flagship Re d’Italia to the just arrive from Britain, brand new and modern turret ship Affondatore as a new flagship. By the time he got there, the battle already developed and his fleet was still without orders. Tegetthoff thus broke his line and created a melee, with a first botched ramming manoeuver, and a second one. This was the right moment. Kaiser Max manage to ram former flagship Re d’Italia, while taking hits crippling her rigging, funnel and deck crew. She soon after tried to ram another ironclad but missed, and ended duelling with the coastal ironclad Palestro, pounding her with fifteen broadsides, but broke off the engagement when Don Juan d’Austria asked for help, just surrounded by Italian ships.

Persano eventually broke off the engagement as soon as he could gave orders, and then refusing to counter-attack, despite his two other fleets were gathering, arguing he was short on coal and ammunition with morale. This was heavily criticized by his own staff and miost Italian officers needless to say and later the govermnent. He was fired soon after. Tegetthoff was now in “hot pursuit” but still, kept his distance until night fell, disengaging. Kaiser Max sailed back with only limited damage.

Tegetthoff kept his fleet in the northern Adriatic, while the war was lost on the ground front at Custoza against Prussia. His fleet patrolled for a time to prevent an attack on Venice. On 12 August, the Armistice ended all operations. By the Treaty of Vienna, Austria became Austria-Hungary (Ausgleich 1867), forced to cede Venice to Italy. Tegetthoff’s navy was now subjected to budgetary cuts with the new bi-national parliament having its Hungarian half not interested by any navy. He saw most his ships decommissioned and disarmed, crews disbanded.

Any modernization effort was hampered by this partial disinterest for the Navy but at least he obtained his ironclads were fitted with new rifled guns. Kaiser Max was rebuilt in 1867 to allieviate her mrediocre seakeeping with a new open bow, plated over, new ram and new armament of twelve 7-inch (178 mm) Armstrong muzzle-loading rifle guns (MRL), two 3-inch (76 mm) 4-pdr guns. In 1873 a close examination of her hull concluded she was rotting away. She was decommissioned and the Navy obtained funds to “rebuild” her. In reality a brand new hull was ordered (same name) resuing her powerplant, guns, armour plating, a clever subterfuge repeated on her two sisters with the complicty of STT shipyard. The new ships were completed in 1875-1876 as casemate ironclad and will have a long career. “Kaiser Max” was however never officially decommissioned before the 1900s.

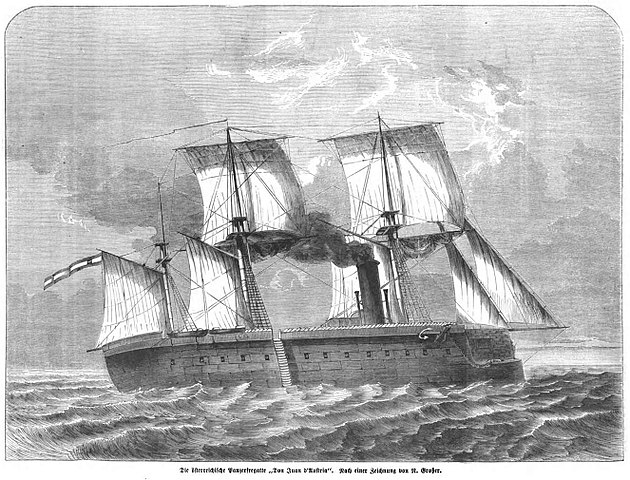

SMS Don Juan de Austria

SMS Don Juan de Austria

S.M.S. Don Juan d’Austria was from Stabilimento Tecnico Triestino (STT) shipyard, laid down in October 1861, launched on 26 July 1862, fitted out in 1863 on the same design and commissioned. She proved on sea trials in heavy weather, like her sisters, to be very wet forward and handling poorly. February 1864 saw her detached for the Second Schleswig War against Denmark with the flagship SMS Kaiser under Vice Admiral Bernhard von Wüllerstorf-Urbair, joining the frigates Schwarzenberg and Radetzky under Wilhelm von Tegetthoff. They met at Den Helder in the Netherlands before proceeding on 27 June to Cuxhaven, arriving on the 30th. The Danish fleet remained in port and declined to fight the Austro-Prussian squadron while Prussia shelled fortificatons in order to capture islands off the western Danish coast. The war won and Don Juan was back home.

In June 1866, Italy declared war on Austria (Third Italian War of Independence) and Tegetthoff mobilized the gleet as rear admiral, assembling it on 27 June at Ancona. The events decribed above saw the iconclad steaming out in the wedge formation on the morning of 20 July to Lissa on the right flank.

In the melee following the first ramming attempt (Don Juan d’Austria followed the flagship, Erzherzog Ferdinand Max but lost contact) she was soon surrounded by Italian ship, asking for help to Kaiser Max, trying to destroy Paltestro. She came to the rescue by a ramming attempt to disperse the Italians, and Don Juan d’Austria engaged Re di Portogallo, shelling her for 30 minutes without much results, before shifting to Affondatore. She took three hits from the latter’s turret holing her unarmored bow but overall she got little damage. One hit struck her belt armor and failed to penetrate a third pierced her quarter deck.

Re d’Italia had being rammed, sinking, Palestro burning and soon detonating due to magazine explosion, Italian admiral Persano broke off the engagement. The Austrians kept contact but broke off when night fall and Don Juan came back to Pola with the rest of the victorious fleet.

Tegetthoff still kept his fleet in full readiness, ready to rush to the defence of Venice. The end of the war put an end to the war with the Treaty of Vienna. In the new Austria-Hungary from 1867, the Navy had the double himiliation of seeing Venice ceded to Italy and her ships forced decommissioned, disarmed, crews demobilized.

The post-war modernization was limited. Don Juan d’Austria in 1867 had her bow rebuilt the same way as her sisters to correct her poor sea-keeping, obtaining twelve 7-inch (178 mm) muzzle-loaders from Armstrong, two 3-inch (76 mm) 4-pounder guns from the same.

In 1873, close examination of the hull led to a planned concellation. However the Austro-Hungarian Navy managed to obtain funds to have her “rebuilt”. Like her sisters in reality her hull was scrapped and a new one was built, larger, with all her equipment reused on the new ironclad, now a central battery ship made by STT shipyard from December 1873 under the same name. The new Don Juan d’Austria would serve for decades afterwards. She will be covered in a dedicated article.

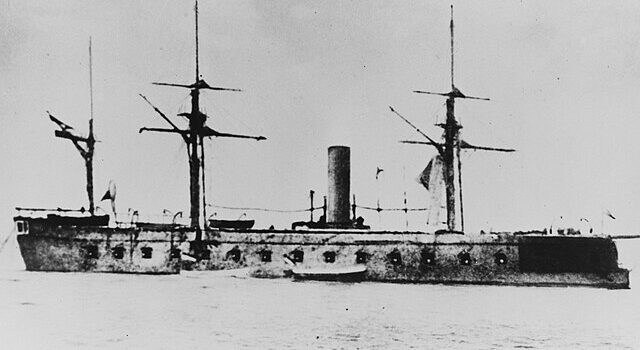

SMS Prinz Eugen

SMS Prinz Eugen

Prinz Eugen was laid down at Stabilimento Tecnico Triestino (STT) shipyard by October 1861, launched on 14 June 1862, completed in March 1863, and commissioned. Like her sister she had a “wet” bow and poor handling. She did not took part in the Second Schleswig War in 1864, remaining in the Adriatic with the two Drache-class ironclads. In June 1866 war broke out with Italy and she was fully prepared under Rear Admiral Wilhelm von Tegetthoff. At first, his opponent Admiral Carlo Pellion di Persano refused to engage his fleet, until pressure let him to besiege Lissa. For three days he pounded the defenses, until Tegetthoff arrived on the morning of 20 July in a wedge formation to break up the local Italian fleet, rearranged to face him while Persano moved to a new flagship.

Prinz Eugen like her sisters was on the right flank of the wedge.

Ploughing in the gap, Tegetthof failed to ram any Italian ships but manoeuvered for another attempt. Prinz Eugen opened fire with her bow guns at first, and during the melee, ipened up with her main battery, on unidentified Italian vessels. Affondatore attempted to ram her, but Prinz Eugen’s Captain skillfully dodged her. He answered by a volley, but it did no damage to the ironclad.

After Re d’Italia was rammed, Palestro exploded, the die was cast for for Persano, which broke off, chased by the Austrians until night fell. The fleet then headed for Pola. Like her sisters Prinz Eugen escaped heavy damage, she probably the least damaged of her three sisters. Thus, Prinz Eugen, Habsburg, and two gunboats remained behind the fleet gatherin in Pola for repairs, patrolling off the harbor for any Italian attempt.

She patrolled later in the northern Adriatic, ready to counter any Italian attack. 12 August with the Armistice of Cormons, then Treaty of Vienna the newly formed Empire of Austria-Hungary ceded Venice and had to decommission and disarm the fleet. Modernization came in 1967 for Prinz Eugen with a new enclosed bow, new ram, twelve Armstrong 7-inch (178 mm) muzzleloaders, two 3-inch (76 mm) 4-pounders. By 1873 the poor state of her hull motivated a “reconstruction”. Like for her sisters, her hull was scrapped, a new one built, all her erquipment resued in a brand new central battery ship. For the Parliamentary SMS Prinz Eugen was simply “rebuilt” with work commencing on November 1873. She will have a long carrer.

The name “Prinz Eugen” was repeated on more modern vessels in the Austro-Hungarian Navy, the second Tegetthoff class dreadnought battleships.

With the disappearance of the Empire in 1918 however the name survived. After Hitler arrived in power in 1933 and after the Anchluss in 1938, he ordered the name of the third Hipper class heavy cruisers to be “Prinz Eugen” as such, as a good will gesture to fellow Austrian sailors. KMS Prinz Eugen would famously fought the Royal Navy at the battle of Skagerrak in May 1941. The name referred to Prince Eugene of Savoy, one of the very best, most distinguished 18th-century general in the service of the Holy Roman Empire.

Read More/Src

Books

Dislère, Paul (1877). Die Panzerschiffe der neuesten Zeit. Pola: Druck und Commissionsverlag von Carl Gerold’s Sohn.

Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1979). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press.

Greene, Jack & Massignani, Alessandro (1998). Ironclads at War: Origin and Development 1854–1891. Da Capo Press.

Hale, John Richard (1911). Famous Sea Fights From Salamis to Tsu-shima. Little, Brown, & Company

Pawlik, Georg (2003). Des Kaisers Schwimmende Festungen: die Kasemattschiffe Österreich-Ungarns, Neuer Wissenschaftlicher Verlag.

Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World’s Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books.

Sondhaus, Lawrence (1994). The Naval Policy of Austria-Hungary, 1867–1918. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press

Wilson, Herbert Wrigley (1896). Ironclads in Action 1855 to 1895. London: S. Low, Marston and Company.

Links

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kaiser_Max-class_ironclad_(1862)

en.wikipedia-on-ipfs.org/ List_of_ships_of_Austria-Hungary

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign