British Revenge over Von Spee

Just as Newsweek frontpage stated in 1982, the “Empire Strikes Back” in December 1914. Like then and earlier, the Royal Navy departed for the Falklands. This remote, cold corner of the South Atlantic, not far from the Argentinian coast and infamous Cape Horn, was the theater of the last battle of Admiral Maximilian Von Spee, after a long and successful -if not legendary- cruise throughout the pacific. His Pacific squadron indeed concluded its odyssey back home by sinking the only obstacle in its way -Admiral Cradock’s Falklands squadron, which was soundly defeated at Coronel in November, off the Chilean coast (battle of Coronel). That was also the first naval defeat of the Royal navy since a century, which could not be left unaddressed. The mood felt like after the sinking of the Hood in 1941, the entire Royal Navy focused on taking revenge.

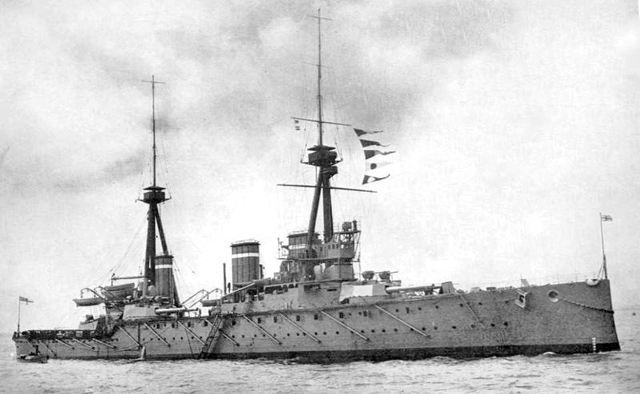

HMS Invincible

Von Spee’s next move

The purpose of the German Admiral then was to make his squadron pass into the South Atlantic, where he intended to attack Britain’s commercial traffic with Argentina (meat) and Chile (nitrate), and Possibly to join the metropolitan fleet. The route was free for Spee, who after a short stop at Valparaiso, where he embarked many exiled Germans (for a return to Germany), and after consulting the Naval HQ by the intermediary of the embassy, warning him against this project, he set course to the south. On the way, he captured four tall ships, before passing Cape Horn with his entire squadron on December 2nd. The initial route, passing 100 miles to the south to avoid being spotted from the coast, had to be abandoned because his worn out light cruisers couldn’t cope with very rough seas, even after it was necessary to throw over tons of Charcoal to lighten the hulls and avoid “plow share” effects. The squadron, therefore, returned twenty miles from the coast, and passed through less troubled weather.

The purpose of the German Admiral then was to make his squadron pass into the South Atlantic, where he intended to attack Britain’s commercial traffic with Argentina (meat) and Chile (nitrate), and Possibly to join the metropolitan fleet. The route was free for Spee, who after a short stop at Valparaiso, where he embarked many exiled Germans (for a return to Germany), and after consulting the Naval HQ by the intermediary of the embassy, warning him against this project, he set course to the south. On the way, he captured four tall ships, before passing Cape Horn with his entire squadron on December 2nd. The initial route, passing 100 miles to the south to avoid being spotted from the coast, had to be abandoned because his worn out light cruisers couldn’t cope with very rough seas, even after it was necessary to throw over tons of Charcoal to lighten the hulls and avoid “plow share” effects. The squadron, therefore, returned twenty miles from the coast, and passed through less troubled weather.

The Royal Navy mobilize

Meanwhile, the outcry caused by Coronel’s defeat caused some heads rolling in the Admiralty: Fisher took the lead as first Lord, immediately establishing a plan to join the Falklands with superior forces. He mobilized the two Invincible class battlecruisers, plus the HMS Queen Mary, previously sent to the West Indies in order to intercept Von Spee, although the latter managed to get through the British net. Eventually the Mediterranean fleet based at Gibraltar was mobilized, despite what the Dardanelles operations required, was scrambled and put in alert to intercept the German forces in case they attempted to reach the North Atlantic.

Postumhous symbolic funerals of Admiral Sir Cradock in port Stanley after the battle of Coronel.

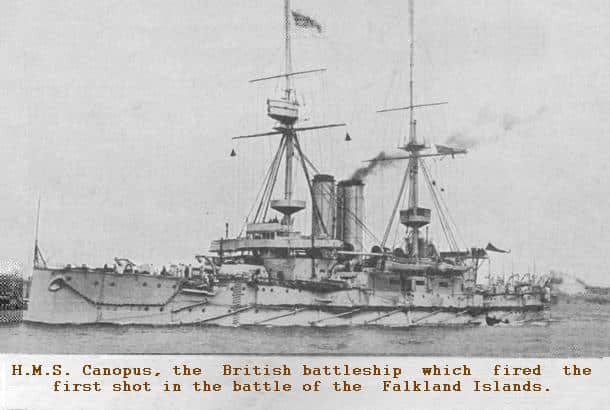

The Royal Navy solicited half of the available battlecruisers force and the two aforesaid, commanded by Vice-Admiral Sturdee, set sail for the Falklands. Fisher projected that Von Spee should probably try to take the Falklands first, settle there in order to launch raids on the British traffic. Therefore it was vital to get there before him. In addition, local authorities send a message by telegraphy (captured by Spee) confirming the departure HMS Canopus for South Africa where a revolt would have broken out. The message was a forgery, and Spee, after crossing Cape Horn, capturing a British sailboat to refuel, lost three days and left the auxiliary steamer fleet in the maze of islands of this area, thinking he could land a party to take Port Stanley.

The Royal Navy solicited half of the available battlecruisers force and the two aforesaid, commanded by Vice-Admiral Sturdee, set sail for the Falklands. Fisher projected that Von Spee should probably try to take the Falklands first, settle there in order to launch raids on the British traffic. Therefore it was vital to get there before him. In addition, local authorities send a message by telegraphy (captured by Spee) confirming the departure HMS Canopus for South Africa where a revolt would have broken out. The message was a forgery, and Spee, after crossing Cape Horn, capturing a British sailboat to refuel, lost three days and left the auxiliary steamer fleet in the maze of islands of this area, thinking he could land a party to take Port Stanley.

Sturdee arrived at the Falklands

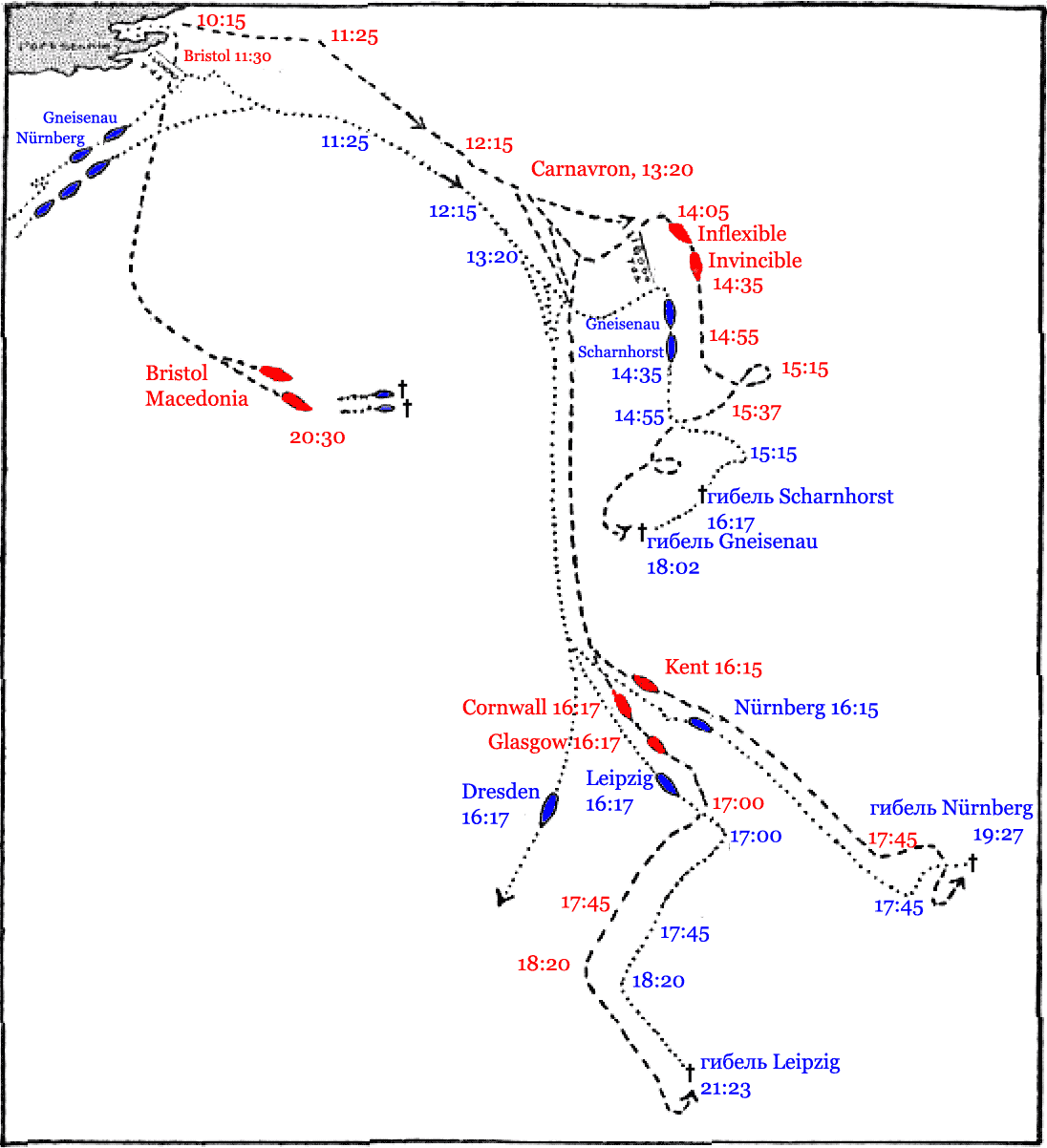

At 7:30 am, Studee’s squadron arrived at the Falklands, before Spee, who unknowingly ran into a trap. Immediately the ships resupplied because Sturdee was asked by Fisher to resume his search for the German squadron as soon as possible. What Spee knows then, however, is that a Japanese squadron is at his heels from the Pacific, so no return is possible. Sturdee, who is unaware of Von Spee’s crossing on December, 2, still thinks he can find him before his crossing of Cape Horn. The black fumes of the German squadron are spotted by an English lookout. Immediately the alarm is raised, but the ships are in bad position, still coaling, their machines are cold, barges are at couple.

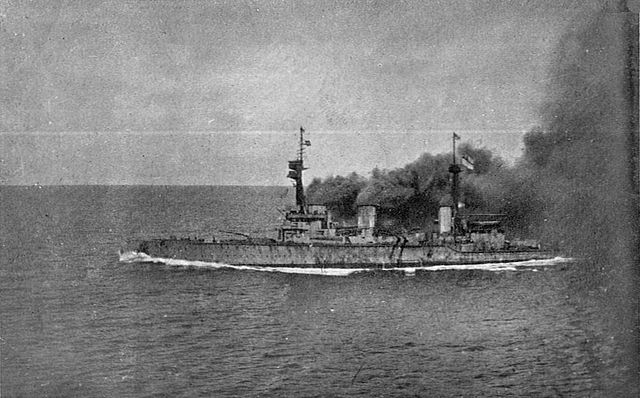

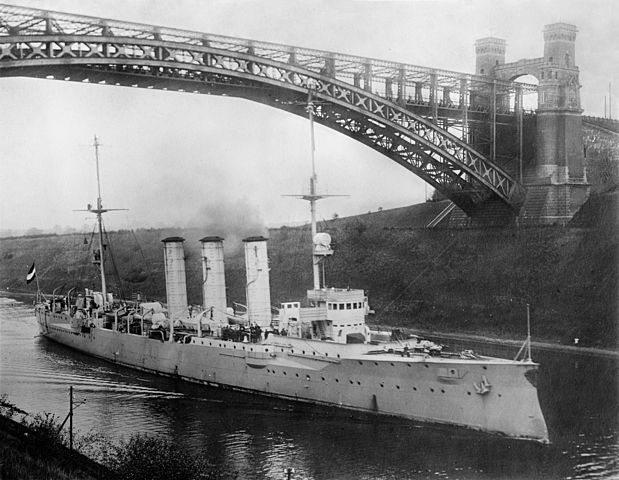

HMS Invincible racing towards the Falklands

The two fleets spots each other

Fortunately for them Von Spee only had at that time his vanguard with the Gneisenau and Nürnberg, and has to wait for the rest of his ships to catch up. Moreover, form that afar, if he spots masts and funnels, he does not identify which ships are present. On the British side, only the HMS Canopus is available immediately for action, the light cruisers Bristol and Glasgow whereas the cruisers Carnarvon, Cornwall and Kent, are also taking supplies. At 9:20 am, HMS Canopus, been deliberately stranded on a sand bank with the tide for stability, opened fire at 11,000 meters while everywhere else crews feverishly prepared for action. Spee had a unique opportunity to change things by sinking the Kent, sailing a parallel course to the exit of the harbor, which could have blocked Port Stanley. Joined by the rest of his forces, he could have the shelled the trapped, immobile English squadron while keeping his mobility.

The battle starts

However at war, nothing unfolds according to plan. Hans Pochammer, captain of the SMS Gneisenau, eventually identified and signaled to Von Spee the presence of the two English battlecruisers, spotting their tripod masts. For the British squadron, the weather was superb and visibility was perfect, and the crew just achieved a lightning fast preparation. Henceforth, all ships freed themselves of their moorings, ascended the anchors, while a black smoke rose above them. One can imagine then the effect produced by seven black plumes, while Von Spee expected to find not a single ship in Port Stanley!

HMS Canopus, firing the opening shots of the battle

The Admiral knew that his units were no match for battlecruisers, much more powerful and faster. Furthermore the Canopus then was hidden, firing from behind a hill, so it was invisible Von Spee’s lookouts, saving Sturdee valuable time. When the HMS Kent finally set sail for the harbour’s entrance, the whole squadron followed her. At 10:00 am, a “general hunt” flag climb to the mast of the Invincible, and the British squadron prepare to laid waste to the rest of Spee’squadron, the last ships arriving in the meantime. The latter renounced duelling with Kent. Aware of of the upcoming challenge, he ordered his light cruisers to escape. He was going to make a fighting retreat with his two armoured cruisers…

Duelling

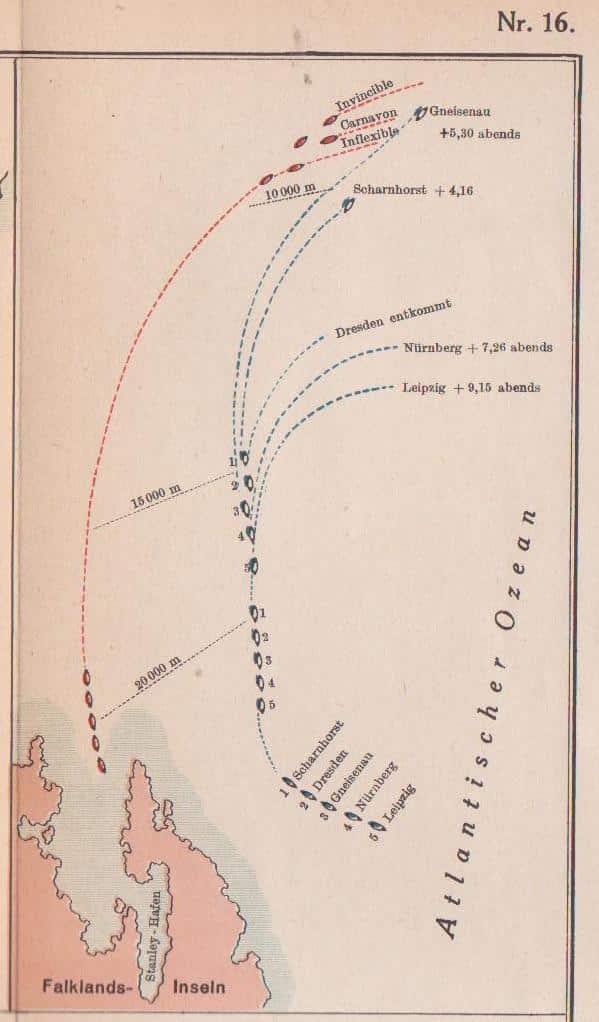

Sturdee, whose two battlecruisers reach 25 knots versus 22 for the Germans, caught them at 12:47 and opened fire at maximum elevation. The first sheaves fall near the Leipzig, but despite the perfectly flat sea, spotters are embarrassed by the torrents of greasy smoke coming out of the funnels, the engines being pushed full throttle. It is more than 13:00 PM when the Gneisenau receives three hits. Through the roof of the 210 mm casemate aft starboard, the middle deck, and the ammunition hold which had to be drowned in emergency. While the distance allowed to fire back, the Germans could not replicate, their targets being Masked by smoke. They managed eventually to hit the HMS Invincible, only a slight damage. The two armoured cruisers then attempted to change course, but the British seemed not to notice it. The German’s new position is however betrayed by HMS Carnarvon, which spotted the move. The duel resumed, but the British are still not close enough and fires at wide elevation. Shells following a parabolic trajectory penetrated the poorly protected bridges of both German Cruisers. In addition, Sturdee detached his three cruisers to chase the Leipzig and the Nürnberg out.

Deadly broadsides

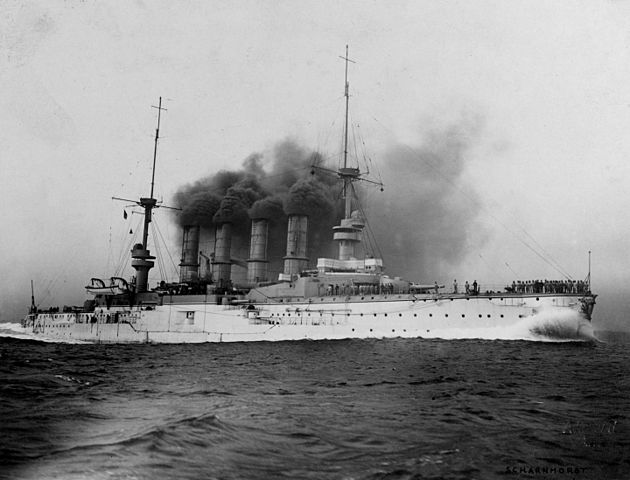

The two battlecruisers then managed to present a broadside, being able to go take a parallel course to the German line at around 3:00 pm, while Spee could do nothing but come closer in order to replicate, exposing him even more. Around 3:30 pm, Spee enjoyed an unexpected and almost supernatural respite: A large white three-masted tall ship coming from nowhere crossed the route of the English battlecruisers, which -maritime code obliged- altered course and slowed to let it pass, sail having priority over steam !… The latter thanked them courteously as in regatta time. But a few minutes later, firing resumed, Sturdee willing to wrap it up before day’s fall. At 4:00 pm, the two German cruisers has been hit many times more by heavy caliber, were prey of flames, in particular the Scharnhorst which bears the mark of the Admiral. The latter now targeted by the two British ships, became a raging inferno and a wreck, signalling to the Gneisenau by searchlight to try to escape. At 4:04 Spee’s ship was slowed down, heeling heavily, her chimneys all crippled and the artillery muted.

Peak of the battle, the Scharnhost capsizes, the Gneisenau flees.

Spee’s final stand

What passed through Spee’s mind at that time ? He brought her flagship closer to his adversaries as if trying to launch a torpedo attack or even try to ram them. The British ships after trying to decipher the move unleashed a full broadside, secondary guns included, and put a quick end to the Maneuver: At 4:17 pm, the proud Scharnhorst began to sink forward rapidly, disappearing with 795 crewmen, including the two sons of the admiral. If that was not cruel enough, survivors are condemned to drawn or freeze to death: In their haste to finish off the squadron, the British ships immediately aimed at the fleeing Gneisenau, not stopping. Around 5:15 pm, the latter exhausted all his ammunition while receiving new hits: She could not sustain more than 16 knots. The two battlecruisers then separated, the Invincible passing by the front at 10,000 meters crossing the T, while the other sailed for the other side of the German ship. At 5:20 pm, SMS Gneisenau, silenced and immobilized, bunkers submerged, began to list. Major Maerker decided to evacuate and scuttle her. The Gneisenau would capsize at 5:35 PM, but this time 190 survivors would be recovered in time from the icy waters (famous photo), including Captain Pochammer, telling later the battle from the German perspective.

Job not done

If the battle of the Falklands seems over, for Sturdee, it’s “job not done”. There are still two light cruisers left to be caught and sent to the bottom. The Dresden meanwhile has taken very early a south-west heading. Three British ships are in hot pursuit, including the two old battleships. The Germans still have good hope: They are 12 miles ahead and night is coming. HMS Kent, however, which chases the Nürnberg, is older and slower, but pushed its engines beyond maximal designed speed, all boilers red hot. The ship managed to reach 25 knots, two more than what is normal. For her part the German cruiser was to make due with worn out machines subjected to heavy strain since the month of August, plus human exhaustion.

SMS Nürnberg

Nürnberg’s end

At 5:30 pm, it’s nearly game over, as Nürnberg’s commander believes that he could no longer flee more from an enemy while under fire and not at least trying to replicate. He changed course and engaged the fight. The duel was to the advantage of the British armoured cruiser, better armed and protected. In spite of this, the Nürnberg closed at 2700 meters – close range at cruiser standard – bearing all its pieces. In one hour and a half the German ship hit fourty times, but the well-protected British cruiser had only a few wounded and one dead to deplore, while the Nuremberg is devastated.

At 6.30 pm, the German cruiser indeed had suffered two boiler outbreaks, speed falling down to a few knots, and had no steering. At 7:00 pm, she had exhausted all her ammunition and was in flames from bow to stern. The commander had the colors struck down to allow his men evacuating without being shelled. The cruiser started to list quickly and at 7:27 pm capsized and sank. Survivors, few in number because the duel had been a slaughterfest, were only 17 to take place aboard Kent’s two only yoals… Her other boats had been riddled with shrapnel during the fight and were unusable.

HMS Glasgow

Glasgow’s revenge

The SMS Leipzig meanwhile was chased by HMS Glasgow, survivor of the battle of Coronel. Suffering the same worn out conditions, the older German cruiser is caught and 150 mm shells rain down its tail. The commander of the German ship decided to drop the distance voluntarily and turn to engage a duel with its own 105 mm pieces. An artillery exchange on semi-parallel chasing course then engaged, but thanks to its superior speed, the British cruiser gradually reduced the gap with the Leipzig, finding a parallel course offering a full broadside. The German ship handicapped by its light shells was heavily pounded, and the situation turned worse as the Cornwall, just catching up entered the fray and opened fire. The latter added not less than fourteen 6 in guns, so the duel turned into a real execution…

SMS Leipzig

Leipzig’s end

Soon the Leipzig lost its front sights while the central steering wheel steering post has been disabled, receiving only orders by voice relayed in chain until the end. Leipzig’s artillery pieces are also shut down one after the other. But the cruiser still stood firm despite the rain of steel and the duel went on, amazingly, for two more hours with all guns available. At 19:00, she only had left her torpedoes, but then maneuvered only at 16 Knots and the torpedoes missed their targets. The commander decided to scuttle the ship, survivors climbing onto the deck.

Damage on the HMS Kent after the battle

Through Glasgow’s sights, observers wonders: The German cruiser was no longer moving, and its crew hidden by the smoke of the fires, was invisible on the deck. Crucially no pavilion rose to the apple of her only remaining mast. The British were even unaware that the crippled cruiser had launched its last torpedoes and was completely defenseless. Therefore still considering the ship a threat, they decided to open fire, making a carnage on the deck. Immediately, fault of a flag, two flares of distress are fired. The British ships ceased fire and boats were laid down. But before arriving, the burning carcass of what was the Leipzig capsized and sank rapidly leaving only 18 shocked survivors.

SMS Dresden

Epilogue

That was the end of the battle. Indeed, the Dresden was in fact the only cruiser able to escape. She succeeded in reaching the maze of islands of the Terra de Fuego, hiding in for a while. She went off by March 14, 1915, and without orders nor hope to return home or finding a suitable base to attempt raids in the Atlantic, had no other alternative than to present the white flag to the first warship on sight. The commander thus spared the lives of his men, avoiding a final useless sacrifice.

Survivors of the Gneisenau being rescued by the Inflexible

For the British, who have cleared Coronel’s heavy blow on Royal Navy’s prestige, victory is total. They only deplored a few dead and injured on the Invincible, Kent and Glasgow but not a single loss on the Inflexible and Cornwall. But above all, the German presence elsewhere than in the North Sea comes to an end. Any threat to the precious blood lines of the empire disappears for long (until the submarine threat became obvious). The few remaining isolated units would be cornered and sunk, and by mid-1915 the only remaining German naval forces would be permanently confined to the Baltic, with the Skagerrak strait shut. Only submersibles would from then on try to reverse the situation, reaching a new height with the the loss of the Lusitania and its consequences. That was the end of a major naval chapter in ww1.

Sources/Read more

http://www.firstworldwar.com/battles/falklandislands.htm

https://www.thoughtco.com/battle-of-the-falkland-islands-2361388

http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/the-battle-of-the-falkland-islands

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_the_Falkland_Islands

http://www.britishbattles.com/battle-of-the-falkland-islands

J.J. Antier & Paul Chack, Histoire maritime de la première guerre mondiale

German Navy vs Royal Navy

German Navy vs Royal Navy

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign