German Navy

German Navy

3-8 August 1914

Prelude to War: The Mediterranean Squadron

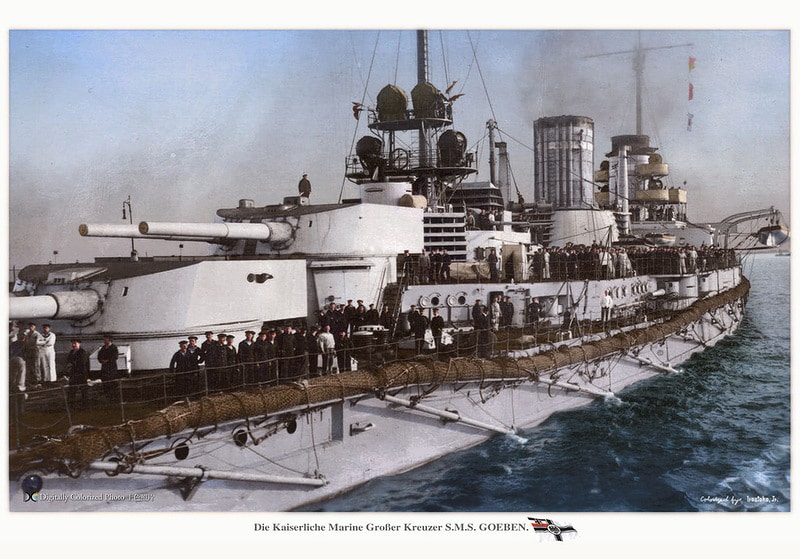

On 2 August 1914, the declaration of war was taking aback all the German units stationed outside the metropolis. The battlecruiser Goeben and the light cruiser Breslau then formed the Mediterranean squadron, usually stationed in Port Said, controlling strategic roadways from the Red Sea to the Suez Canal. However the Goeben, freshly introduced into service since 1912 accumulated after trials a few teething problems with its boiler tubes. She could not reach 18 knots for safety reasons and had to be replaced in October 1914 by its sister ship Moltke upon return to Germany for further changes.

So far her role in peacetime was to escort the Kaiser when cruising on his yacht the Hohenzollern to his summer residence in Corfu. Just after the attack in Sarajevo, the Goeben was at Pola and Breslau in Durazzo (Austria-Hungary, south of Montenegro). Killing time, sailors of Breslau disputed a friendly party of water polo with fellow men of the battleship King Edward VII anchored right next to them.

SMS Goeben, rear view, colorized photo.

Souchon’s options

That’s when the fateful messages fell by wireless telegraph. Hostilities were imminent. Rear-Admiral Wilhelm Souchon was leaning over a large map of the Mediterranean. Several options were open to him, notwithstanding the orders that could come from Tirpitz.

That’s when the fateful messages fell by wireless telegraph. Hostilities were imminent. Rear-Admiral Wilhelm Souchon was leaning over a large map of the Mediterranean. Several options were open to him, notwithstanding the orders that could come from Tirpitz.

There was one certainty indeed: If he remains in Pola, he would be locked up in the Adriatic and probably subject to the decisions of the Austro-Hungarian Admiralty, judged too timorous. He could try to rally the Hochseeflotte, but this required to run throughout western Mediterranean and especially pass Gibraltar where the Royal Navy in force was blocking the way, not to mention the French fleet, the bulk of which was within range from Toulon and the entire North African coast.

Souchon was to play all his thinking to go unnoticed, perhaps showing a Russian flag for example, or a false smokestack and canvas to disguise his silhouette. Moreover, once out on the Atlantic, he still had to join the motherland through either the Arctic Circle and bypassing Great Britain by the northwest, which also bring his ships “within range” of Scapa Flow. He could also attempt launch a raiding party across the Atlantic, even attempting to join Von Spee squadron in the south… By August 2, Germany was likely to be at war against France shortly, still not against England. It would therefore pragmatically decide initially to attack convoys of French North Africa. Thus he sailed after completing his preparations hastily and sailed to Algeria by midnight.

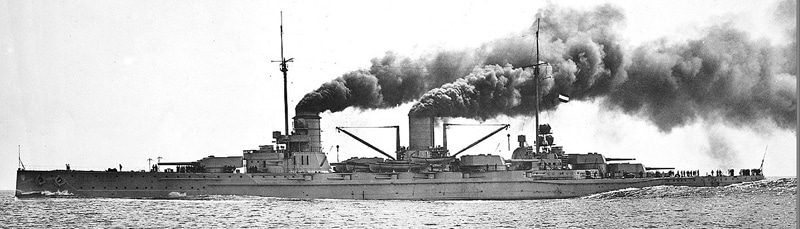

The Goeben at full speed

Leaving the Adriatic, the Goeben was joined by the Breslau. On 3 August, Souchon was traveling nearby Bonifacio, but changed course at 20 knots, to rampage the Algerian coast. French Admiral Augustin Boué Lapeyrière, French Commander of the Naval Forces in the Mediterranean, was aware of the departure of the Germans ships. He had only one obsession, protect his convoys. He was to sail from Toulon in three line towards Philippeville, Bone and Bougie. In total 89 ships carrying 49,000 men and 11,800 horses. At 18:45 a new message came down from the staff: The war was officially declared this time; But Lapeyrère was not informed. The English Admiral Milne knew, but there was no communication code between French and English fleets.

Still, Admiral Milne send his subordinate Troubridge in the Adriatic with two armoured cruisers while reaching himself Malta, hoisting his mark on the HMS Inflexible. He received at 12:45 a Churchill order to follow the two Germans ships. Meanwhile, they had forced the pace. Contrary to Admial Bouré de Lapeyrière fears, the German ships had neither the scope nor the speed to intercept the French, so all the convoys passed safely. But Souchon went also unnoticed. By August 3, at the evening 8:30 PM, Milne sent HMS Indefatigable and Indomitable in Gibraltar.

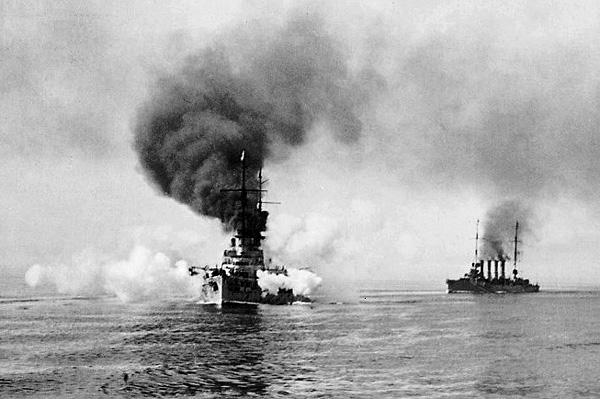

The night of August 4, at 5 am, Souchon was off Philippeville, passing through the berths. His gunners gave all their heart to the task and comprehensively pounded the harbor, one hour after the Breslau who had separated from the Goeben evening, and had won Bône to believe they moved westward. The Goeben received meantime an urgent message by wireless telegraphy from Berlin for more: “Alliance concluded with Turkey, Join Constantinople, stop.” Souchon therefore first sailed northwest to fool observers from the coast. He had passed through the French fleet, but the Royal Navy was now on full alert, and he had to re-cross the entire Mediterranean in the opposite direction! On his way he transmitted his orders to Breslau and then headed for Messina to complete its provision of coal. Breslau however side was heading directly east.

North of Goeben position at around 100 kilometers was sailing the first French squadron. Meanwhile the British battlecruisers were coming from the east at full speed, accompanied by the light cruiser HMS Dublin. The Goeben veered east at 6:30. At that time, the first French squadron commander believed on the basis of coastal observations that the German ship rallied Algiers and divided his forces into two wings, one heading west with the big battleships, while the other continued southeast with three armoured cruisers, Jules Michelet, Ernest Renan and Edgar Quinet.

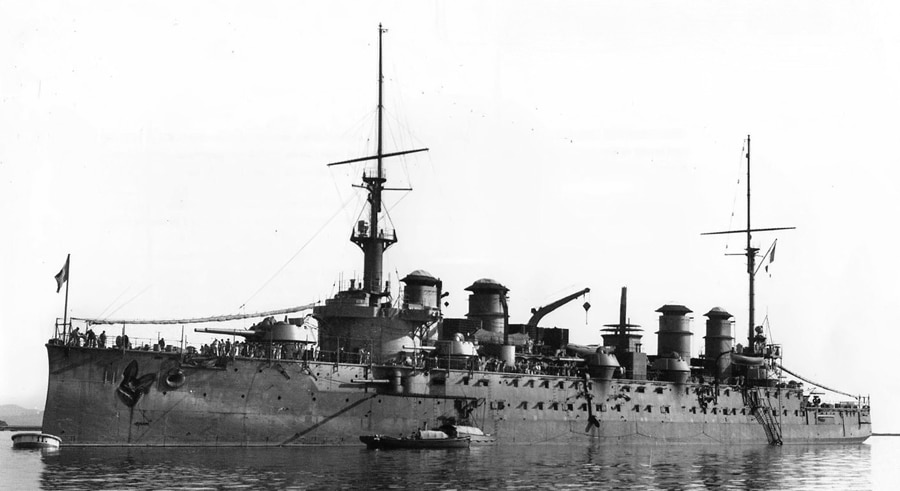

French Armoured Cruiser Jules Michelet. It would need bad coordination between allies, official hostilities dates release, and Turkish alliance to avoid the Goeben be cornered and sunk.

At 8:00 am, the weather was execrable and reduced visibility, but French ships were just 40 nautic miles (74 km) from the Goeben. The latter spotted them, but it was not mutual. When the British battlecruisers saw in turn the German battlecruiser steaming full speed eastward they changed headings and started a hot chase. The Goeben now catch in the open was making hell of its machines to reach nominal 24.5 knots, gradually seeing the English ships approaching at 9000 meters, well within gun range, although UK was still not officially at war, but Milne was unable to contact his French counterpart to close the trap. Only HMS Dublin followed Goeben to Sicily, then veered course is 21:50. Both English battle cruisers already had abandoned pursuit since 7:05 p.m due to their lack of coil. Although UK was now officially at war since 21:00, the Dublin also started to run out of fuel and could anyway not face the battle cruiser, and breaks off. Breslau arrived at Messina before the Goeben.

Rear-Admiral Souchon was annoyed to see that since the cruiser arrived supplies operations still were not started. Kettner, Breslau Commander, then claimed that the Italians had categorically refused to tap into their reserves, claiming neutrality. Souchon then requisitioned by authority all Germans steamers present in the bay, asking their captains to give their stocks of coal, laboriously transported with barges, boats, man’s backs and arms strength. At dawn, the operation was still ongoing. All sailors were committed into the task.

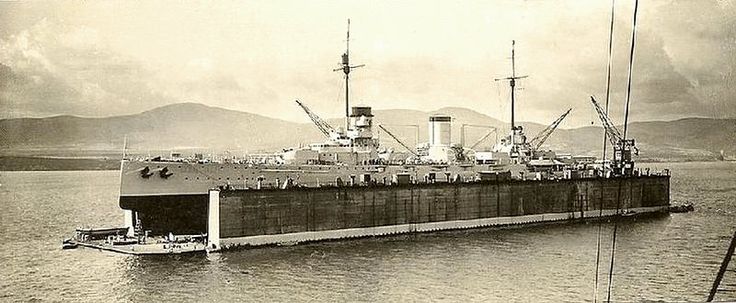

Rare photo of the Yavuz (Ex-Goeben) in drydock

Few had slept for 48 hours. This transfer to feed the steel ogre took 36 hours in total, well above the regulatory 24-hour presence of belligerent ships in neutral ports, which raised official protests from the Italian ambassador in Berlin. Authorities of the port in the morning signaled the government’s presence in the port of the two Germans ships, but it was only 18 hours later on August 5, that the Italian Ambassador in London informed the naval British attaché.

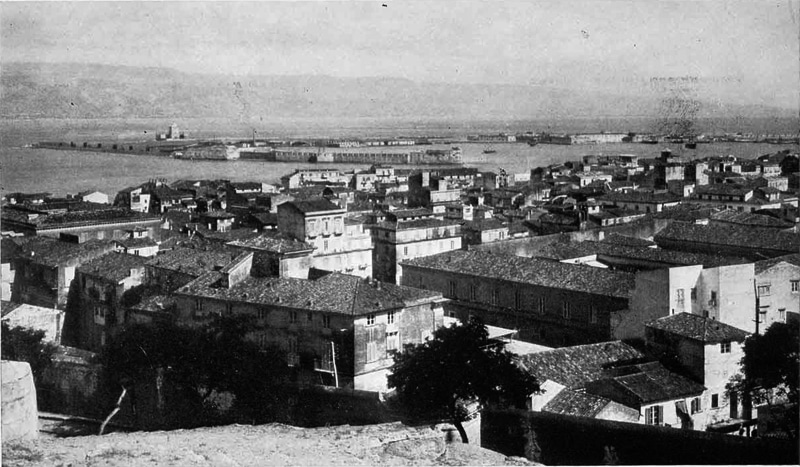

Messina harbour, circa 1914.

At the dawn of August 6, the laborious refuelling/coiling had ended. While many sailors, exhausted, collapsed in corridors, Souchon, also tired, met Kettner and Doenitz (later Admiral of the Kriegsmarine but then a mere lieutenant in the Breslau) to decide the way forward. He suspected that the English, who remained quietly outside Italian territorial waters, waiting for them. The orders from Berlin were to reach Constantinople and avoid confrontation but Souchon could not see any way off. At 17 hours, the two ships lifted anchor and headed for the pier, and then steamed full speed.

The Goeben ad Breslau entering the Dardanelles

There were first tracked at reasonable distance (out of reach of the 280 mm guns of Goeben) by HMS Gloucester. She promply signalled: “Incoming!”. Again, Souchon had to speed up his pace. The Gloucester clung knowing that Admiral Troubridge came from the east with the HMS Defence, three other armoured cruisers and 8 destroyers, but he arrived too late to intercept the German ships. He finally understood that the final destination of Souchon was probably Turkey and veered north, starting the pursuit.

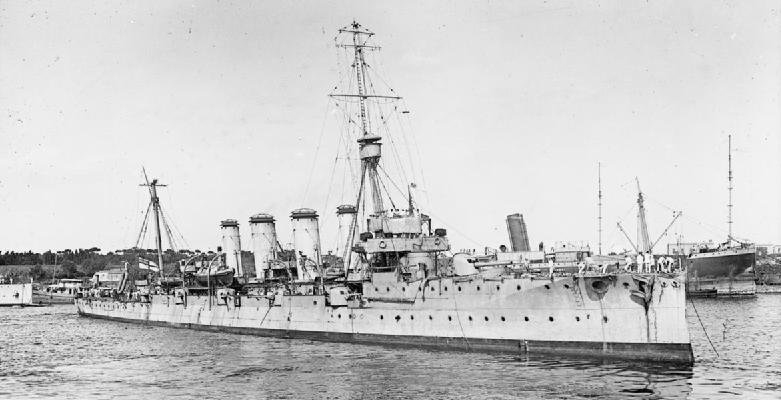

But it was Dublin that took the first hit. The Germans ships arrived off Malta rapidly. Two destroyers and HMS Gloucester closed in, the destroyers trying to launch their torpedoes, but were greeted with precise volleys and had to break off their approach. The Goucester, commanded by Capt. Kelly, then engaged the Breslau.

A 11,300 meters, at 12:35, she opened fire. Breslau had already requested Souchon if he could attack the English cruiser, but Souchon refused, preferring not to waste time. When the German cruiser took a 150 mm hit, she replied anyway, scoring two on Gloucester in reply. The latter was preparing his next salvo, but watchers saw the Goeben closed in with the Breslau, therefore having the British Cruiser within range. Kelly therefore decided to leave safely.

British Cruiser HMS Gloucester

Now nothing could stand in the way of the Mediterranean squadron. Both ships anchored August 7, in the bay of Denusa Island, at the entrance to the Dardanelles, under protection of Turkish Forts and waiting for instructions or authorization from Berlin. Both ships were still on high alert, waiting for a possible fight against the Royal Navy, but nothing came. August 10, Souchon was allowed to proceed at the entrance of the strait. A Turkish destroyer approached and the Goeben signalled in morse “I want a pilot.” The captain of the Turkish torpedo boat replied “follow me.” Both ships then crossed the nets, mines, under the reassuring shadow of the many forts and batteries posted along the high cliffs.

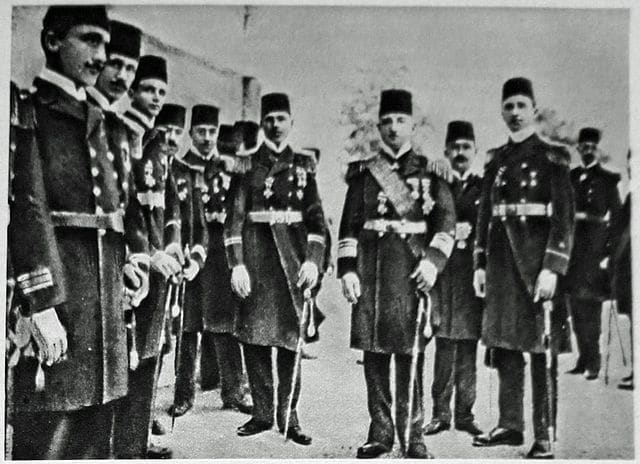

Amiral_Souchon_and-staff_in_Turkish-Uniforms

The Turkish navy back then had a rather poor navy, but they had fortified the Dardanelles in order to make the only access to Constantinople and the Black Sea unassailable. But the British did not gave up: The close ships, the cruiser HMS Weymouth, burst at the entrance to the Dardanelles, determined to follow the Germans ships. But the Turks, although still officially neutral, barred his way with several destroyers.

On the evening of 10 August, two German ships anchored safely in Constantinople. Berlin, to show its good will to the “Sublime Door”, donated the squadron to the Turkish government. The German pavilion was downed and changed for the crescent on purple, and Souchon, wearing the fez, was appointed by the Sultan “Commander of the Ottoman Navy”. It was the beginning of the “triple alliance”, and opening of a third front in the middle East.

Postcard of the Turkish Fleet in 1914

The Story of the Goeben and Breslau did not stop there however. Their rampage against the Russians will see them for the duration of the war raiding the coast and attacking convoys throughout the black sea. The Goeben will be eventually after the war renamed Yavuz Sultan Selim and stayed in service not only in the interwar, but also world war two and even until the late 1950s. It is a shame that such ships was not preserved, as it would be today the sole example of a German Battlecruiser, and even the sole ship of this type preserved anywhere. The Breslau was renamed Midilli.

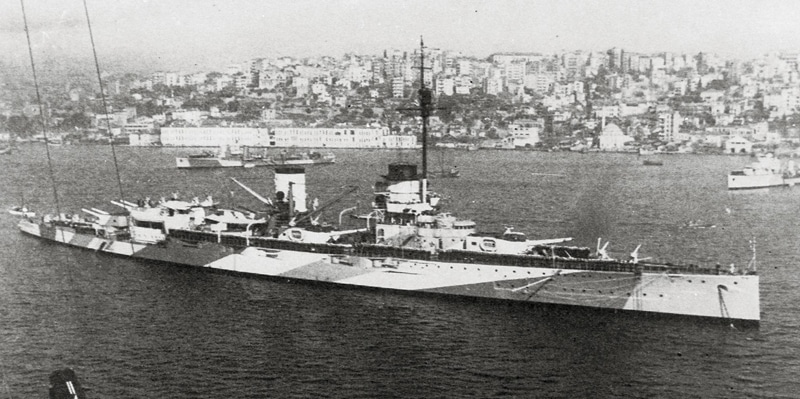

Battlecruiser Yavuz Sultan Selim, Turkish flagship until the 1950s (here in 1945).

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign