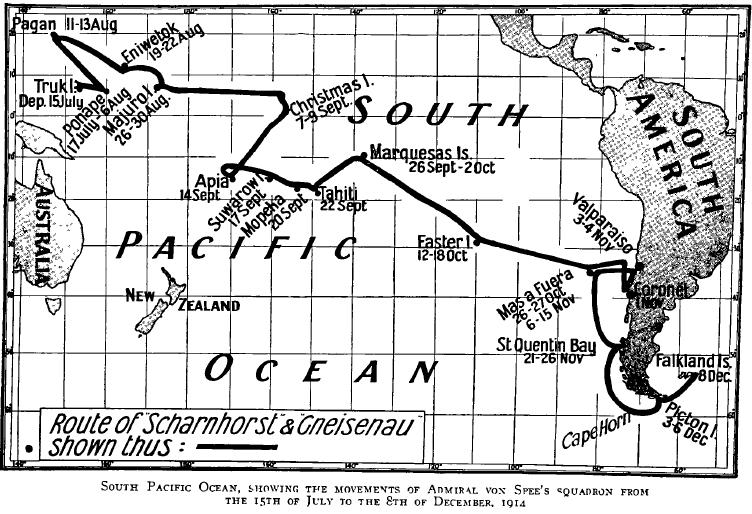

Graf Spee’s far east squadron in Valparaiso, Chile, about to sail afte the battle, Nov. 3, 1914

The first British defeat since 100 years

Long before the famous 1980s Falklands conflict, the Royal Navy had already crossed fire in this remote corner of the globe. This time it was against German forces, Graf Von Spee’s Far Eastern Squadron arriving from the Pacific, that was going to sail into the Atlantic and cause havoc on trade.

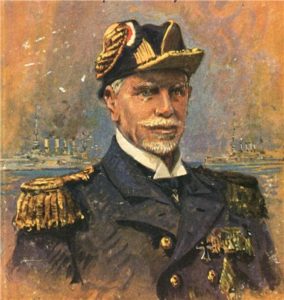

Apart from the confrontation with Heligoland, which had limited results, the first battle of Coronel was the single greatest naval event before the end of 1914. Its main protagonist was a Prussian aristocrat of the old school, National hero in his country after his epic on the other side of the world: The Count (Graf) Maximilian Von Spee.

Apart from the confrontation with Heligoland, which had limited results, the first battle of Coronel was the single greatest naval event before the end of 1914. Its main protagonist was a Prussian aristocrat of the old school, National hero in his country after his epic on the other side of the world: The Count (Graf) Maximilian Von Spee.

Admiral Von Spee

This man, born in Denmark in 1861 and who spent most of his career in Africa, had become rear-admiral at 49. He was 53 when he was about to deliver the two battles of his life in a few months. He was promoted Vice-Admiral in 1912 and was given the task of the Far East squadron, consisting of partly obsolete ships, light cruisers and cruisers, based at Tsing Tao, the old German trading post in China. In June 1914, far from the noises of war, the crew of the two armoured cruisers was all to the enthusiasm of a beautiful cruise in the turquoise waters of the South Pacific. Then by wireless, he is asked to return to the colony. At the time of the declaration of war, all that was not necessary for combat was landed, and the cruisers who had time were repainted in two shades of grey, the other retaining for some time their beautiful white colonial livery. But the squadron could not remain on the spot, for fear of being destroyed at anchor, or intercepted en route by Allied British, Australian, Russian and Japanese fleets.

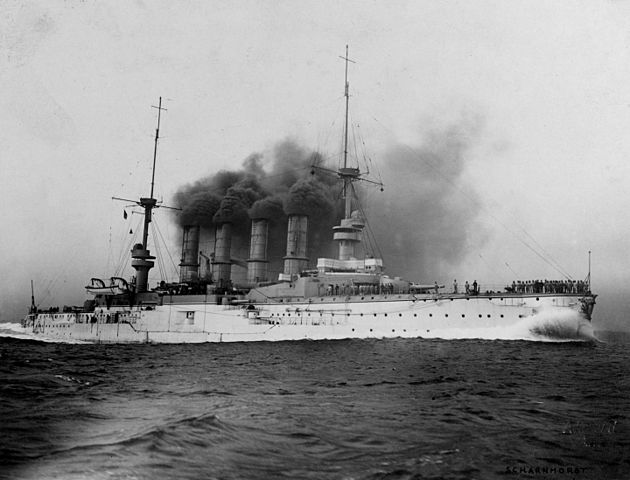

Armoured Cruiser SMS Scharnhorst, named after a Prussian General in the Napoleonic wars.

Von Spee prepared to send part of his squadron, including the two cruisers of the  (Scharnhorst and Gneisenau), light cruiser Nürnberg, two of the Dresden class (Dresden and Emden), and the old Leipzig. The rest of the squadron consisted of ships of lesser tonnage, four gunboats of the Iltis class, and three river gunboats, the Tsingtau, Otter and Vaterland, S90 torpedo boat and the tanker Titania.

(Scharnhorst and Gneisenau), light cruiser Nürnberg, two of the Dresden class (Dresden and Emden), and the old Leipzig. The rest of the squadron consisted of ships of lesser tonnage, four gunboats of the Iltis class, and three river gunboats, the Tsingtau, Otter and Vaterland, S90 torpedo boat and the tanker Titania.

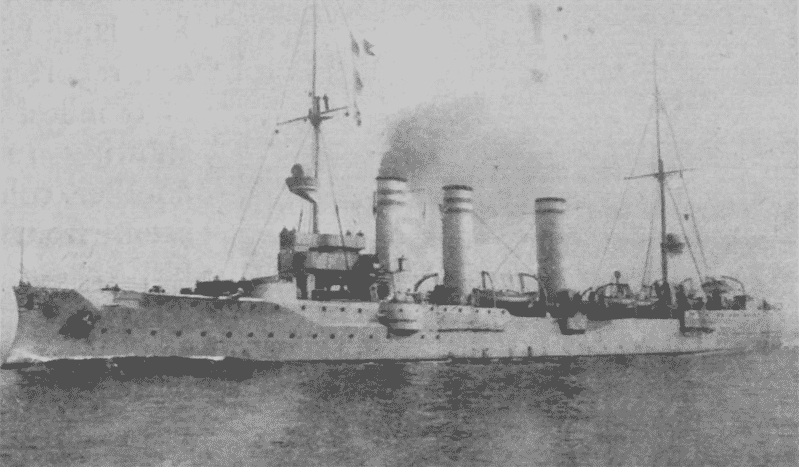

German light cruiser SMS Nürnberg. Late into the fight, she nevertheless caught the escaping, badly damaged HMS Monmouth almost by chance in the obscurity, trying to reach the Canopus.

A trapped squadron

After having assembled all the officers in the square of the Scharnhorst, which bore his mark, he discussed the best possible options. 1-He could tried to return to Germany and add his forces to the Hochseeflotte, but the risk was far too great in view of the proximity of the Grand Fleet and several closely guarded roads at the approach of the North Sea. 2-He could also attempt a privateer’s war to weaken allied traffic on all the seas of the globe, especially in the heavily defended southern hemisphere. This option seems the least risky and the most promising, and eventually pass Cape Horn and carry the war into the Atlantic. It was a real convoy of more than twenty ships which had taken shape, counting the 5 cruisers (the Emden had detached from the group on 14 August to deliver its own racing war in the Indian Ocean and make diversion). Von Spee measured the risks: He was to cross the vast South Pacific, but at 10 knots to save coal and keeping pace with the oldest, slowest steamers.

From Samoa to Tahiti

On board German ships, sailors were eager to fight. Von Spee confered one more time with officers and decided en route to attempt a raid on the Samoa Islands with his two armoured cruisers, to draw the attention of the British Navy, while hoping to find some enemy vessels at anchor. He fell on the islands at dawn, September 14th, but only to find the Apia’s wharf empty, and the Union Jack floating on the city. Apart a bombardment that would surely hurt his fellow citizens more than the British troops, he can not seriously consider taking back the city with his only two marines companies.

Von Spee biopic – The Great War channel.

Reluctantly, he resolve to change course and join Tahiti in order to shell Papeete, where a few French ships reside. He arrived on September 22 at dawn. German ships were not expected, they were no lookouts, and the two ships just maneuvered between the shallows to stand in battle line. Once spotted at last, the French evacuated the city and prepared the meager “coastal batteries” available: Guns of the gunboat Zelée, which have been landed and camouflaged previously. They fired a few warning shots, but remained silent to avoid being spotted when the two German vessels replied with their heavy artillery.

Von Spee now seek to disembark a company, since he thinks he is dealing with a weak garrison – which is true. The French then maneuvered and scuttled the Zélée across the pass, obstructing it. The two German ships then open fire on the city, quickly set ablaze. Von Spee realized that he will no longer be able to land his troops, or proceed to supply coal and food, and retire. His ultimate goal became to return to Chile, refuel, and then cross Cape Horn before engaging in a much more fruitful trade war in the Atlantic. The British, who received report from the squadron’s position are preparing to block his way. Leaving the rest of the convoy and refueling, the three light German cruisers (Nürnberg, Leipzig, Dresden), joined the two armoured cruisers.

Von Spee’s ships path

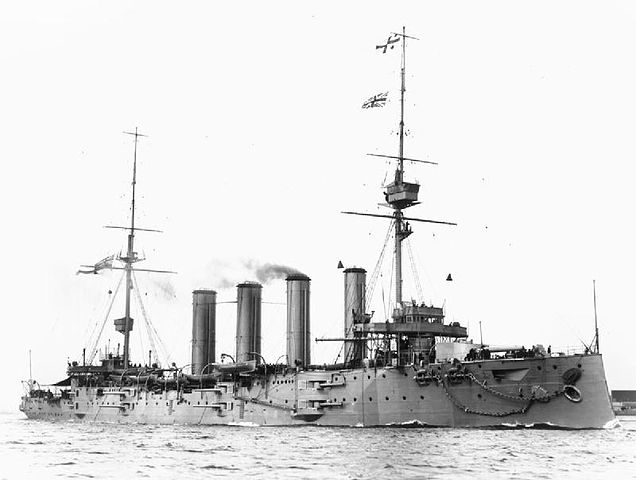

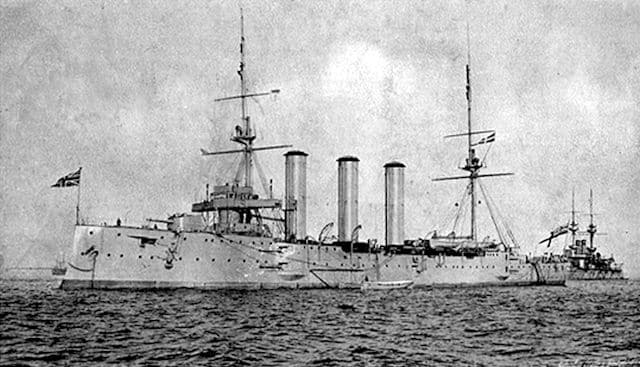

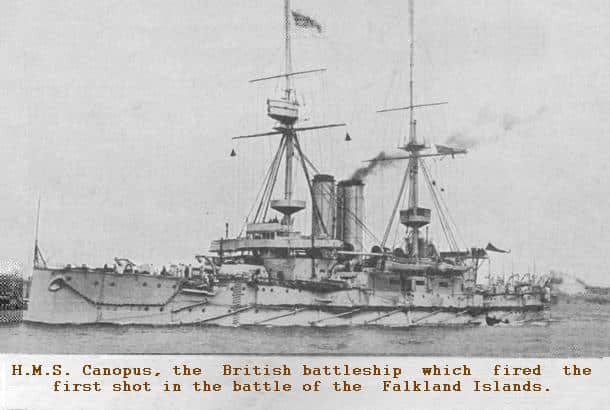

Sir Cradock’s Falklands squadron

Meanwhile, miles apart in Port Stanley, a British Navy squadron is awaiting orders from Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock. Nicknamed the “old Gentleman”, he is also an old refined aristocrat. Von Spee even knew him well personally during his stopovers in peace time. The two men respect each other. But now both are about to do their duty. Cradock’s squadron is the only one that can oppose the German ships on their way in the Atlantic. It consists of the Good Hope, an armoured cruiser, the cruisers Monmouth and Glasgow and the Otranto, an auxiliary cruiser, converted liner. Unfortunately, this squadron also includes the old battleship Canopus, but the latter had a considerable delay to heat his boilers, and would not sail in time. She only could make 12 knots and therefore layed behind.

Meanwhile, miles apart in Port Stanley, a British Navy squadron is awaiting orders from Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock. Nicknamed the “old Gentleman”, he is also an old refined aristocrat. Von Spee even knew him well personally during his stopovers in peace time. The two men respect each other. But now both are about to do their duty. Cradock’s squadron is the only one that can oppose the German ships on their way in the Atlantic. It consists of the Good Hope, an armoured cruiser, the cruisers Monmouth and Glasgow and the Otranto, an auxiliary cruiser, converted liner. Unfortunately, this squadron also includes the old battleship Canopus, but the latter had a considerable delay to heat his boilers, and would not sail in time. She only could make 12 knots and therefore layed behind.

Armoured cruiser HMS Good Hope

Cradock has been informed since the beginning of October of the imminent arrival of the Germans. He asked the Admiralty repeatedly for reinforcements, refused: The only other ships available were ordered to be kept in reserve on the other side of Cape Horn, in case the Germans passed in force. The old Admiral has no illusions about his fate: He has his own grave dug in the Falklands’s governor garden, deposited his medals, knowing his true steel sepulture would be at the bottom of the sea soon. He wrote his Testament, bids farewell to his family and the sailed following day for the cape of Good Hope (Even more Ironically named in this occurrence). His squadron set sail on October 22, headed southwest, crossed Cape Horn, and then headed north to cross the Germans.

Departure

He knows hen that Von Spee commanded two armoured cruisers, and that in the meantime his squadron was reinforced by the other three cruisers. This gives them a distinct advantage: HMS Good Hope had a more powerful artillery (240 mm) on paper, but these guns are old, with ancient sights, and can offer only one salvo for two for the Germans. As for the Monmouth, she was one of the least protected cruisers in the Royal Navy, an unfortunate experiment imposed by budget cuts. The HMS Glasgow was fairly well armed and fast, but less efficient in heavy weather. The Otranto has almost no military value. Worse still, Cradock’s ships are composed of reservists hastily mobilized and insufficiently trained…

Prelude to the battle

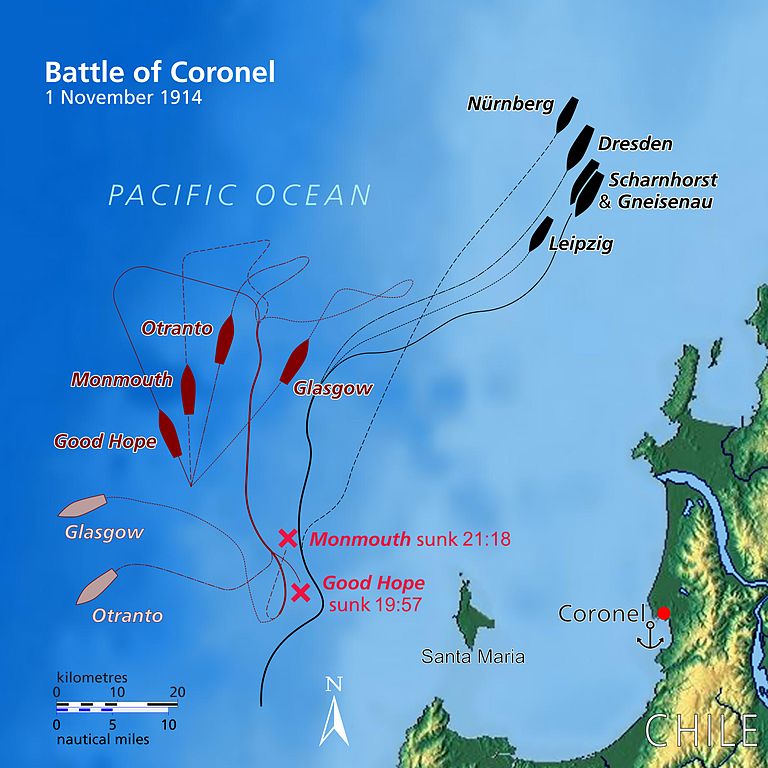

On 31 October, Von Spee was advised by wireless that an English cruiser had been seen entering the port of Coronel in Chile. Spee rallied directly the area from the northeast, leaving the Nürnberg behind off the Chilean coast, hoping to intercept the cruiser as it leaves. At the end of the afternoon (4:20 pm), Scharnhorst’s lookouts spotted three ships, later identified as British cruisers. HMS Monmouth and Glasgow are followed by the Otranto, sailing west-northwest, joined by the Good Hope at 17:20, taking the lead of the battle line, before changing course to present a broadside to the Germans. War pavilions are erected, and Von Spee prepares his ships for battle.

Armoured cruiser HMS Monmouth

A game of light and shadow

There is nearly a gale, disturbing lookouts of the two fleets, and making fire more imprecise, but the initial configuration is not clearly to the advantage of the Germans: The British ships indeed come from the south, far at sea compared to the Germans, which are coming from the North and arranged in a line along the coast. It is then 18:20. With the falling darkness, the Germans still have sunlight blinding their telemetric sights, while the British can see the metallic silhouette of the German ships shining out on the dark cliffs of Chile. Von Spee knows it, and try to stay out of reach as long as he can. The British are approaching, but not fast enough, allowing the setting sun to finally reverse the situation completely: Now the German ships are plunged in the dark and merging with the cliffs, while on the contrary Cradock ships are showing in Chinese shadows on the horizon. they are now a target of choice for the gunners of the two armoured cruisers who pass for the best of the fleet.

Rush hour

At 6.34 pm, the Scharnhorst, at the head, opened fire on the Good Hope, while the Gneisenau immediately followed on the HMS Monmouth and the Dresden on HMS Glasgow. SMS Nurnberg was still way behind. Cradock by then still hope to left the German ships and join the Canopus, which would have given him a decisive advantage, but the Germans stand precisely between him and the coast. The fight quickly turns to the advantage of the Germans who in the third salvo put the front turret of the Good Hope ablaze. The Monmouth is also also, loosing both turrets. The Otranto, in order not to be a useless victim, moves away from the battle.

As for the two light cruisers which clash at the end of the line, their salvos are lost at sea because of gale force waves. The struggle becomes fierce as the two British armoured cruisers takes more hits, burning wildly, all the communication lines destroyed. Gunners now shoot by view only. Distance soon fell to 6000 meters and the obscurity increase. Now the British ships are burning this makes the Germans firing much more precise and devastating. The secondary artillery of both English ships still cannot enter into action because or the high wave crests, and the main artillery soon silenced.

At 19:00, the distance fell to 5000 meters. Von Spee decides to take some distance, fearing a possible torpedo attack. The Gneisenau is hit by the Monmouth (three casualties). At 19:20, the Scharnhorst gives the coup de grace: One of her shells lands between chimneys 2 and 3 on the Good Hope which explodes and sank rapidly with all hands. As he foresaw, the “old Gentleman” followed his crew to the end… On the HMS Monmouth sides, things are equally gloomy. She fled, taking advantage of the falling night, at low speed, dodging the last shells.

British light cruiser HMS Glasgow

The end

The unequal battle is closing to its conclusion. The Monmouth takes advantage of the attention drawn for a while on the Good Hope, in an attempt to escape and extinguish its fires, as does HMS Glasgow in the dark. The commander of the latter then proposed to the Monmouth to take her in tow, but the latter refused, preferring to see the Glasgow escape sooner than risking to see both caught in such a bad posture. At 20:50, HMS Monmouth sails towards the coast at low speed, her blackened hull smoking, riddled with gaping holes through which yellow-orange lights still flickers.

Battleship HMS Canopus. She never was ready on time to join the battle

By then the Nürnberg just joined the fray, and by luck fall on the British ship, but she is unable to recognize the Monmouth and don’t open fire, fearing a friendly fire. Monmouth’s crew, rather than knocking down the flag and being rescued, decided to fight to the last man, despite having almost no cannon left but still one of their searchlights, which which they light their war pavilion. It’s an execution. The Nuremberg opens fire at point-blank range and achieve rapidly the sinking British ship. No survivors either. The Germans will later defend their non-assistance by pleading a nearly impossible rescue by night, in game winds and fearing possible British reinforcements (like the Canopus)… After this disaster the Otranto is left with HMS Glasgow, hit five times with low amage, that took a long loop in order to cross the HMS Canopus path.

Night’s sorrow

Although reunited, the two ships would not find Von Spee in the dark. The German squadron is retreating to Valparaiso. The Count squashed a champagne bottle in the square of the officers of the Scharnhorst while Schnapps flowed for sailors mad with joy. For the first time in more than a century, the Royal Navy is defeated at sea. Plus, the whole squadron had only three wounded to deplore (none fatally). As for damages, they could be repaired within a few hours. To do this, the squadron stops in Valparaiso from 2 to 3, to respect the 24 hours regulations for any belligerent in a neutral port, after refueling and gathering food. Von Spee regretted to not find the Glasgow and complete his destruction. Moreover he was afraid of the 12 inches armed Canopus still was looking for him. He then began a cautious run in the South Pacific, temporarily avoiding passage through the Cape Horn.

Painting of the battle by Hans Bohrdt

The British are Stunned

On the British side, the battle results are appealing: On November 2, News Headlines all tells the Cape Horn squadron and its famous admiral final doom. The House of Commons is agitated, demands explanations from the Admiralty. But this one has changed minds since Lord Fisher is appointed on the eve of the battle, as first lord of the sea in place of the old prince of Battenberg. Teaming Sir Winston Churchill, he decide to “take things in hand”. Indeed, Von Spee threatens the Chilean nitrate (vital for English shells) route, and the Argentinian beef route, providing half the needs of the population. Von Spee fate is sealed. There will be a sequel, the second battle of the Falklands, in shape of a revenge…

German Navy vs Royal Navy

German Navy vs Royal Navy

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign