The Kyūshū Q1W Tōkai (“Eastern Sea”) was the first and last Imperial Japanese Navy (and world’s first) dedicated anti-submarine patrol aircraft (Allied name “Lorna”). Although superficially similar to the German Junkers Ju 88 it owe little to it in technical terms, being made deliberately slow and underpowered as well as much smaller traded for range. But beyond its technical specs, it embodied the late realization by the Imperial Japanese Navy staff that allied submarines could pose a serious threat to its communication lines, across its recently acquired Empire. Something that will haunt the IJN for the next years (and doomed Japan for that matter). Development of the Kyūshū Q1W as the “Navy Experimental 17-Shi Patrol Plane” started indeed all the way back to September 1942, but it only first flew a year later in September 1943, and worst still, only entered service by January 1945.

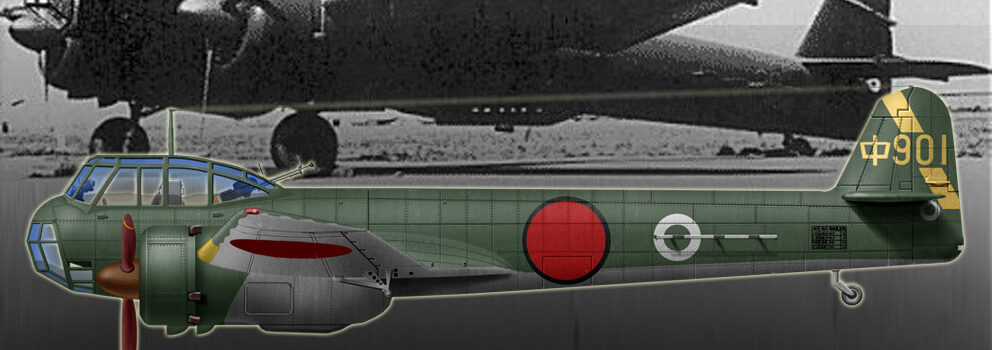

Prototype in 1944

The core specification was not speed, but visibility and the ability to fly low and slow for long period of time. The all-wooden Q3W1 Nankai (South Sea) was a successor developed alongside but went nowhere. Only 153 were delivered, and they arrived way too late to make a difference.

The Tokai (Q1W) was a land-based anti-submarine patrol aircraft of the Imperial Japan of World War II. As the name Q1 suggests, it was Japan’s first aircraft developed as a patrol aircraft. 153 aircraft were built, of which 68 remained at the time of the defeat.

Development

The Imperial Japanese Navy ordered development of the Kyūshū Q1W as the “Navy Experimental 17-Shi Patrol Plane” in September 1942. At that time, the US submarine threat has just yet registered, but it was planning for maintaining the communication lines within the Empire. The project compared to everything else, was however low-priority. The first test flight took place in September 1943 and it entered service in January 1945. Apart is strange resemblance to the German Junker Ju.88 it was given low-power engines, perfectly suited for long periods of low-speed flight.

As the Pacific War intensified, the Navy felt the need for a coastal patrol aircraft wit dedicated anti-submarine (ASW) attack capability. Watanabe Iron Works (later Kyushu Aircraft) at the time relatively “free” was ordered to develop the prototype 17 test patrol aircraft, in September 1942 (Showa 17). Initially, it was considered as a carrier-based aircraft as well as a seaplane, but the land-based variant was to be tested and proven first.

The main specification points requested were:

- To be as slow as possible

- To be capable of flying over 10 hours or more.

- To be capable of diving to strike after detecting an enemy submarine.

Watanabe immediately started working, but only completed the first prototype in December 1943 (Showa 18), a year and three months after receiving the specifications. In between, the company had been renamed Kyushu Aircraft. The design was heavily based on data from the Junkers Ju 88 bomber, which the Navy purchased plans from Germany before the war for research on “twin-engine dive bombers”. The design did had some influence on several manufacturers, but none retook the design as deeply as Kyushu. This enabled its engineers to gain a considerable time.

The prototype first flew in September, so before even the prototype was officially completed, and the results of the test were generally good, except for some issues with its directional stability. So after producing eight prototypes and increased the tail’s dimensions and shifted position, mass production was approved in April 1944 (Showa 19). This was without even waiting for official adoption. Its equipment was changed, the armament was strengthened, these changes were made on the fly at the facorty floor, delaying completion. So by January 1945 (Showa 20), the Tokai 11 (Q1W1) was officially adopted by the Imperial Japanese Navy.

In addition to this model, the company started improvng on the design, and worked on a derivative which swapped its 7.7mm swivel machine gun, for a forward-fixed 20mm machine gun located on the underside of the main wing base. It was used for self defence as well as to fire on surfaced submarines. It was designated the Tokai Ichiichi Ko type (Q1W1a), but the main problem was to find well trained enough pilots. The model was indeed found difficult to maneuver for rookies. The company immediately started working on a trainer type, same twin-engine, but modified with a parallel double control system, whuch became the prototype Tokai training aircraft (Q1W1-K). Unfortunately, production of the latter was authorized but never materialized.

About Kyūshū Hikōki K.K. (九州飛行機)

The Kyūshū Aircraft Company Ltd) was a Japanese manufacturer of military aircraft, mostly created in the 1930s to bolster the industrial capacity in Japan but limited to other firms’ designs. By the end of the war however, there was enough accumulated experience over ten years to undergo its own products, such as the radical J7W “Shinden” fighter. The company was named after the Kyushu island, southermost of the large home islands, where it was based. It originated in Fukuoka-based Watanabe Tekkōjo (a former Steel Foundry) and started aircraft parts manufacturing in 1935. By 1943 the aircraft division was consolidated as Kyūshū Hikōki, the original company enamed Kyūshū Heiki (Kyūshū Armaments). Postwar it became Watanabe Jidōsha Kōgyō (Automobile Industries), making bodies and parts until dissolved in 2001.

The company was responsible for a large array of aircraft, the E9W – ‘Slim’ 1935 submarine-based reconnaissance floatplane, the J7W Shinden prototype fighter in 1945, the K6W (WS-103) seaplane for Royal Siamese Navy, K8W 1938 floatplane trainer prototype, K9W Kaede (Maple) “Cypress” 1939 basic trainer (licenced Bu 131 Jüngmann), K10W – ‘Oak’ 1943 intermediate trainer, K11W Shiragiku 1943 crew trainer, Q1W Tokai and Q3W Nankai ASW/patrol aircraft. The company was quite budy in 1945 notably producing the K11W1 Shiragiku bomber trainer converted for Kamikaze strikes.

Outside the Q1W which at least saw some production, even limited as the company was a dwarf compared to Nakajima, the Q3W1 Nankai (South Sea) was a mass-produced evolution of the first design, but in all-wood construction. The only prototyoe was destroyed during a landing after its first flight. The IJN for ASW warfare could also count on the Mitsubishi Q2M1 “Taiyō” derived from the famous torpedo bomber Mitsubishi Ki-67 Hiryū “Peggy” but it did not progressed beyond preliminary design stage.

Design of the Q1W or Kyushu Model 11 (陸上哨戒機 東海)

The Q1W was tailored to conduct long-term patrol flights at low speeds, with a cruising speed as low as 70 knots (160 kph or 80 mph). It was in addition able to dive immediately after a submarine was spotted, and recover from this dive after dropping one or two 250kg bombs. This made for a design that was indeed, for 1945, not fast at all and relativerly easy to caitch and down by any fighter of the day. However, its slow speed was rather an advantage in that case as th difference in speed made it more difficult to hit actually, given the huge difference with its predator, which onl had a limited opportunity window to engage before overtaking it.

fuselage and general layout

The Q1W was a narrow-body elongated 2-engine all-metal cantilever monoplane of conventional design. Its wingswpan was of 16 meters, so too much for IJN carriers, apart perhaps Shinano, for a wing area of 38.21m2. In addition these wings were not folding, so it would have been permanently parked on deck, taking a considerable area. The fuselage reached, from the glassed nose to the tail end, 12.085m for a full height of 4.118m at the top of the tail. As usual in Japanese construction, it was very lightly built and only weighted 3,050 kgs empty, 4,745kg loaded with gasoline, with a reglar service load of 4,300kg and an overload limit calculated for taking off at 5,332 to 5,318 kg and heavy load limit at 4,480kg,gross weight at 4,800 kgs. It had rounded tail and rudder, but its straight wings ended in the same way as the Mitsubishi G1M.

The diving requirement obliged engineers to work out of the box. To enable an immedate, steep descent at an angle of 70 degrees, which was contrary to the light construction made in order to spare fuel and extend the range, the strucutre was still reinforced enough to support the charge. The flap functioned as an air brake, and can be fixed at any angle from 0 to 90 degrees by hydraulic actuation. It was a slotted flap to make it light, with slits (elongated gaps) at 45% and 70% of the flap chords. Even if they were opened at a large angle, they were calculated to do not cause vibration.

They helped also landing, especially important for carrier landing, opening up to 90 degrees and 70-75° during steep descent to suppress overspeed, but there was still buffeting and sole instablity left and right due to snagging so the pilots needed some care. In addition, the manufacturing quality of each rotor blade rudder was poor making variations in weight balance and dimensions. There was in fact a accident during a steep descent seemd to be originated by rotor blade flutter. As a countermeasure, mass balance was installed on each rotor blade, while pilots were instructed not to make their dive beyond to 170 knots (314.84 km / h), wheeras the deep dive angle was also restricted. All this required extra training from rookie pilots.

The crew of 3 comprised the pilot located in the glassed cockpit, slightly offset of the axis, the observers crouching in the glassed nose, with binoculars and a targeting calculator slaved to the diving indicator for bomb release. There was also the navigator, seated behind the pilot in the cockpit, facing a radio and having a map table. The Q1W was virtually defenseless apart a single flexible rearward-firing 7.7 mm Type 92 machine gun in th fuselage aft of the glassed cockpit, manned by the navigator.

Engines

The core of the low fliying abaility ws a pair of very minipalistic powerplant for 1945, the smallest on production at the time, the Hitachi GK2 Amakaze 31, with 9-cylinder, air-cooled radial piston engines. They were rated for 455 kW (610 hp) each. These engines worked well for transport planes and trainers. Hitachi manufactured aircraft engines since 1929 and concentrated on low-power 7 and 9 cylinder radials as well as inverted inline 4s. In 1939 Hitachi took over Tokyo Gasu Denki K.K. (Tokyo Gas & Electric Co.) and procured nearly all IJA and IJN trainers, mostly copies of German designed Hirth air-cooled inline engines.

This radial was the smaller in service for an active combat aircraft of the IJN, only powering the Kyushu Q1W Tokai (Eastern Sea) Patrol Plane and it proved the right engine for it, with a 785 Amakaze engines built between 1944 and 1945. It was coupled with a 3-bladed Hamilton type variable-pitch propeller, three balded, with a diameter of 2.5 m. It was a direct-coupled engine with no reduction gears, with a propeller speed 2-3% higher. There were two tanks, one of 1200 liters in the fuselage balance center, and 800 liters in the wings.

Performance

The Q1W was not tailored to break any top speed records, only capable of topping 322 km/h (200 mph, 174 kn at 1,340m) or 222 km/h at 1,500m, with a range, most expected, of 1,342 km (834 mi, 725 nmi). It had a service ceiling of 4,490 m (14,730 ft or 6,000m) in order to detect surfaced submarines at long ranges. Given its almost animc engines, the rate of climb was limited to 3.8 m/s (750 ft/min). Its wing loading was 126 kg/m2 (26 lb/sq ft) and power/mass 0.19 kW/kg (0.12 hp/lb). It needed 8 minutes 44 seconds to 2,000m and 2 minutes 40 seconds to 1,000m altitude.

Equipments

For navigation, the Q1W was planned to be fitted with the new electric probe for detection, but it could not be completed in time, so instead it went it was equipped with the outdated H-6 radar detector. Antennas were installed on the wings and fuselage, with a search direction in three directions, forward, right, and left. The operator needed to constantly switch between them so as not to miss anything on the flight path. The display was a very rudimentary A-scope type with an horizontal axis for the distance, vertical axis for the signal strength as well as a Type 3 No. 1 detector or KMX.

For navigation, the Q1W was planned to be fitted with the new electric probe for detection, but it could not be completed in time, so instead it went it was equipped with the outdated H-6 radar detector. Antennas were installed on the wings and fuselage, with a search direction in three directions, forward, right, and left. The operator needed to constantly switch between them so as not to miss anything on the flight path. The display was a very rudimentary A-scope type with an horizontal axis for the distance, vertical axis for the signal strength as well as a Type 3 No. 1 detector or KMX.

The detection width was narrow at 100 m left and right, so it was assumed the aircraft would be used in formation with a horizontal interval for diagonal cover and complemented by magnetic search also in formation, making for a 1 km wide search area with a 6-aircraft formation which unfortunately never materialized. To no disturb the magnetic anmoaly detector, the ASW bombs (depth charges) were made in demagnetize metal and platic or wood. For these, there were two types of delay fuzes with a upper fuse detonating in 10 seconds under 100 water, and the second, 5 seconds under 50 m.

The “C device” emitted an ultra-long wave of about 100 kHz, transmitted underwater from a ground base station, detecting interference waves in the sky above the submarine, so potentially to be caught by the Q1W in flight, and vectored in. The Jeju Island Corps tested the “C device” finding it better the classic electric probe, and again it was designe dto be used in formation.

As an ASW patrol aircraft, the large glassed nose was perfect for wide forward and downward view, helping improving the visual detection even of underwater submarines under a low depth (just below the surface). But it is also vulnerable in crash landings or accidents, and increased the casualty rate of the crew. The cockpit was partly offset to the left side of the fuselage, with the navigation officer on the rear seat concentrating on the maps, radio as well as magnetic search displays as well as being in charge of the rear machine gun.

armament

On this chaper, the only armament was for long a single flexible rearward-firing 7.7 mm Type 92 machine gun, activated by the navigator at the rear of the glassed cockpit. However there was no forward-firing armament, but this was corected notably to actively attack encountered submarines, and one or even two fixed forward-firing 20 mm Type 99 for the Q1W1a, autocannon fitted when available latter in 1945 in pods under the wings roots. The usual load was two 250 kg (550 lb) bombs or four 60 kgs. depth charges strapped under the fuselage. The setup was by magnetic proximity but the bombs were equipped with contact fuses.

Variants

- Q1W1: One prototype.

- Q1W1 Tokai Model 11: main production model.

- Q1W2 Tokai Model 21: version with tail surfaces in wood, built in small numbers.

- Q1W1-K Tokai-Ren (Eastern Sea-Trainer): trainer with capacity for four, all-wood construction. One prototype built.

In same time, Kyūshū built the K11W1 Shiragiku bomber training plane (also used in Kamikaze strikes) as well as the Q3W1 Nankai (South Sea), a specialized antisubmarine version of the K11W, in all-wood construction. The first prototype was however destroyed during a landing accident on its first flight and the program terminated.

operational life

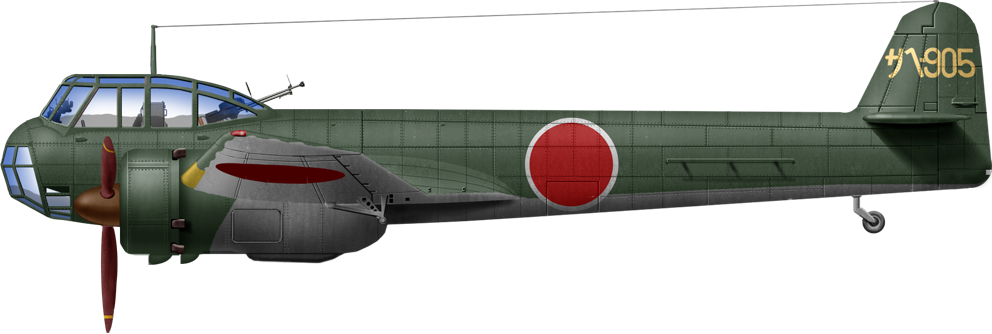

The first unit to deploy the “Tokai” was the Saiki Naval Air Corps in June-July, which wrote the procedures to use this model and this unit was operational in October 1944 (Showa 19). Initially, all production aircraft were vectored to the Saiki Naval Air Corps. This was for training the pilots and mechanics for maintenance. After that, they were redeployed to various air squadrons around the Japanese home waters, but many ended in the 901st Naval Air Squadron at Tateyama Air Base.

In any ase, they were used for anti-submarine patrols in the East China Sea area, from the Ogasawara Islands and Jeju Island and Soyeupo Air Base. The biggest weakness underlined by pilots was the low-output engines, leaving little room for power generation and so to expand the capabilities of the on board electronics or upgrade them. In fact batteries were provided, but tey added to the total weight of the aircraft and further degraded performances. The Tokai was deployed by the 901, 903, 954, 956, Saiki Kokutai and the Reconnaissance 302nd Squadron. By August 1945 only 68 remained, most being shot down or lost in accidents or training attrition.

After the war, some Japanese researchers came to the conclusion the Tokai managed to sink seven U.S. submarines in a single week, but there are no records supported by either official Japanese or US records. By the time it was officially adopted, the Japanese military had lost air superiority over even the Japanese home islands, making the slow and poorly agile Tokai and easy target for US Hellcats and Corsairs. There was even a record of a TBM Avenger shooint down one of these. One was even chased off by two PBM flying boats. Th majorit of the losses were attributed to encounters with fighters. From October 19, 1944 official service start to August 1945, it recorded an extremely high wear and tear rate.

The Tokai was an interesting design nonetheless, quite radical in its approach, the first truly dedicated to detect and sink submarines. The 3-member crew operating Type H6 airborne radar and dropping tow special Type 1 Number 25 Mk 2 depth charges were a powerful combination, authorizing day and night operations. To extend the range, two additional drop tanks were fitted. As for kills there were a few probable, given some US submarine deployed in home waters were indeed sunk with unclear reasons and often reported aircraft attacks. The kill obtained by on Tokai of the 901st Kokutai based in Shanghai was credited with probably the USS Trigger in March 1945 near the Tushima straits. When not in use fo ASW patrol it was also used for reconnaissance missions and a few were impressed for last-ditch kamikaze attacks with rookies pilots. Many were captured postwar, and at leas one tested, seen with US markings.

| Crew | 3 |

| Lenght | 12.09 m (39 ft 8 in) |

| Wingspan | 16 m (52 ft 6 in) |

| Height | 4.12 m (13 ft 6 in) |

| Wing area | 38.2 m2 (411 sq ft) |

| Empty weight | 3,102 kg (6,839 lb) |

| Gross weight | 4,800 kg (10,582 lb) |

| Max takeoff weight | 5,318 kg (11,724 lb) |

| Powerplant | 2 × Hitachi GK2 Amakaze 31 9-cylinder air-cooled radial piston engines, 455 kW (610 hp) each |

| Propellers | 3-bladed variable-pitch propellers |

| Maximum speed | 322 km/h (200 mph, 174 kn) |

| Range | 1,342 km (834 mi, 725 nmi) |

| Service ceiling | 4,490 m (14,730 ft) |

| Rate of climb | 3.8 m/s (750 ft/min) |

| Wing loading | 126 kg/m2 (26 lb/sq ft) |

| Power/mass | 0.19 kW/kg (0.12 hp/lb) |

| Machine gun | 1 × flexible rearward-firing 7.7 mm Type 92 |

| Cannon sometimes fitted | 1 or 2 × fixed forward-firing 20 mm Type 99 |

| Bombs or depth charges | 2 × 250 kg (550 lb) |

| Avionics | Type 3 Model 1 MAD (KMX), type 3 Ku-6 Model 4 Radar, eSM Antenna |

Gallery

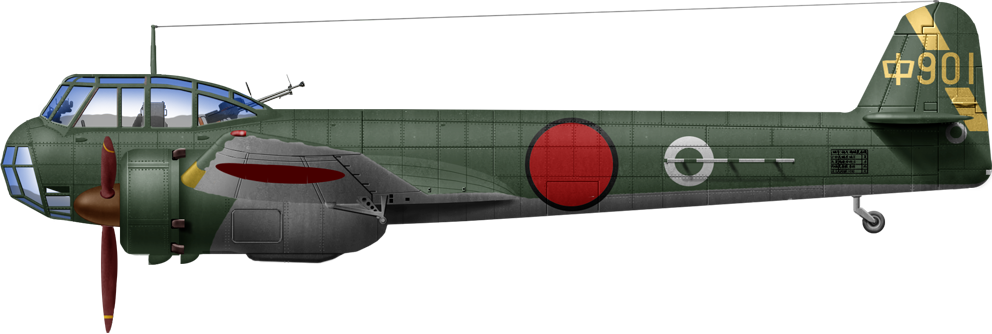

901st Kokutai, Shanghai (credited with sinking USS Trigger, March 1945).

Read more

Books

Francillon, R. J. (1979). Japanese Aircraft of the Pacific War. London: Putnam & Company Ltd.

“Naval Air Corps” Kōjinsha NF Bunko, October 1990. ISBN 978-4-7698-3234-8。

Masatake Okumiya, “The Complete History of the Naval Air Corps,” Asahi Sonorama, November 1988.

Yasuzo Nakagawa, Naval Technical Research Institute, Kodansha Bunko, October 1990.

Jun Okamura et al., “The Complete Picture of Aviation Technology,” Hara Shobo, 1976.

Shigeru Nohara, “Japan Army and Navy Prototype/Planning Aircraft 1924~1945,” Green Arrow Publishing Co., Ltd. ([Illustrated] History of Military Aircraft in the World 8), September 1999.

Minoru Akimoto, “Aiming for the Hero of the Air Defense of the Mainland,” Volume 4, Green Arrow Publishing Co., Ltd., “The Complete History of Japan Military Aircraft Air Warfare,” June 1995.

“Pacific War Japan Navy Aircraft” No. 38, Bunrindo (Aviation Fan Bessatsu Illustrated), August 1987.

Tsuruo Toriyo, supervised by “Unknown Military Aircraft Development,” Shotosha (Bessatsu Aviation Information Aviation Secret Story Reprint Series 1), March 1999.

Naval Air Corps, Kojinsha NF Bunko, October 1990.

Masatake Okumiya, Complete History of the Naval Air Corps, Volume 2, Asahi Sonorama, November 1988.

Yasuzou Nakagawa, Naval Technical Research Institute, Kodansha Bunko, October 1990.

Jun Okamura et al., The Complete Picture of Aviation Technology, Volume 1, Hara Shobo, 1976.

Shigeru Nohara, Japanese Army and Navy Prototype/Planned Aircraft 1924-1945, Green Arrow Publishing. September 1999.

Akimoto Minoru, Aiming to Become Heroes in the Defense of the Homeland, Vol. 4, Green Arrow Publishing June 1995.

Pacific War: Japanese Navy Aircraft, No. 38, Bunrindo, Aviation Fan Special Edition Illustrated, August 1987.

Torikai Tsuruo (ed.), Unknown Military Aircraft Development, Vol. 1, Kantosha, Special Edition. March 1999.

Links

www.airtoaircombat.com

militaryfactory.com

aviastar.org

forum.warthunder.com

airandspace.si.edu/

en.wikipedia.org

ja.wikipedia.org

daveswarbirds.com

combinedfleet.com

airpages.ru

avionslegendaires.net

historyofwar.org

valka.cz

airwar.ru/

ne.jp/

aviastar.org

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign