Arapiles was a Spanish broadside ironclad, wooden hulled armoured frigate built in England, launched in 1864 and in service until 1882. She was bought on the stocks, for the Spanish Navy, while being started at Green, Blackwall, London in June 1861 as an unarmored steam frigate. She was then purchased and converted into an ironclad while under construction. In 1873 she was damaged after running aground and repaired in the United States during the Virginius Affair and tensions between the US and Spain. She was hulked in 1879, but never sailed again. She was inspected in 1882 and her hull’s poor condition forced her reconstruction to be cancelled in 1882 so she was scrapped afterwards. #armada #arapiles #cantonalwar #carlistwar #1898 #ironclad #spanishnavy #blackwall #virginiusaffair

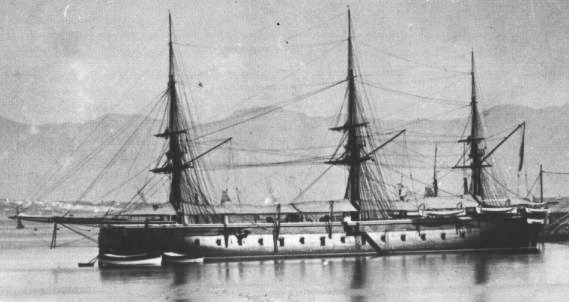

The previous vessel, as a steam frigate in 1861

Design of Arapiles

Arapiles was named for the hills at the Battle of Salamanca. She was purchased while in construction on the stocks, while building at Green shipyard in Blackwall, London. Her conversion into an ironclad started by August 1862 so barely a year after she was laid down, and she received some roughly 200 long tons (203 t) of wrought iron armor while her armament was amended on demand by the Spaniared. She was launched on 17 October 1864, completed in 1865.

Hull and general design

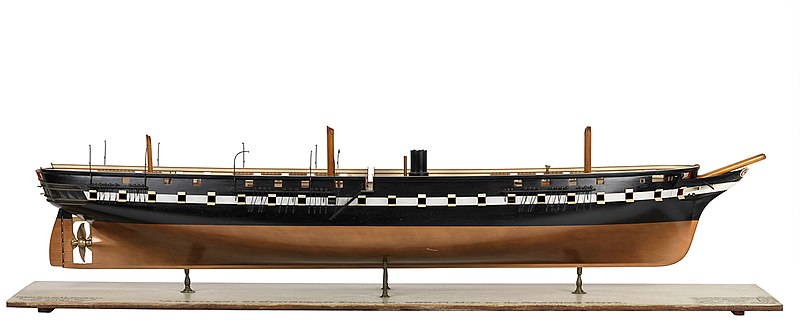

Arapiles displaced 3,441 long tons (3,496 t). She was 280 feet (85.3 m) long at the waterline, for a beam of 52 feet 2 inches (15.9 m) and draft of 17 feet (5.2 m). Her rigging was three masts, barque, with three sail stages (course, topmast, royal) and three stud sails, three jibs. This compensated for the lack of range as usual of her high consumption steam engine.

Powerplant

Arapules had a single trunk steam engine, with steam provided by six cylindrical single-ended coil burning boilers exhausting into to a single low funnel. It passed on power to a single propeller shaft, four bladed bronze, not removable, fixed pitch. It had been designed for an output of 2,400 indicated horsepower (1,800 kW) and on paper speed of 8 knots (15 km/h; 9.2 mph).

Armament

Arapiles was a broadside ironclad, yet she had two heavy main guns, Armstrong 10-inch (254 mm) and five 8-inch (203 mm) rifled muzzle-loading guns in the center of the main artillery deck completed by ten 68-pounder smoothbore guns fore and aft of these. Due to the state of her hull ten years after, apparently completely rotten, her modernization never happened. She was decommissioned with the same armament as she entered service.

Protection

Sources differ on her wrought-iron armor thickness, which happened to have range between 3 to 5 inches (76 to 127 mm) thick. The deck was not armoured and there was no conning tower.

⚙ specifications |

|

| Displacement | 3,441 long tons (3,496 t) |

| Dimensions | 280 ft x 52 ft 2 in x 17 ft (85.3 x 15.9 x 5.2 m) |

| Propulsion | 1c shaft Trunk steam engine, 6 boilers: 2,400 ihp (1,800 kW) |

| Speed | about 8 knots (15 km/h; 9.2 mph) |

| Range | |

| Armament | 2× 9-in RML, 5× 8-in RML, 10× 68-pdr smoothbore |

| Protection | Belt: 114 mm (4.5 in), Battery: 100 mm (3.9 in) |

| Crew | 537 |

Career of Arapiles

After completion, Arapiles could not leave for Spain as soon as she was ready, due to diplomatic pressure as the Spain was still raging with Chile and Peru. The United Kingdom enforced her neutrality agreements not to refuse her to depart, but to be provided state coal, except she was heading in international waters and met a coaler. There was also a clause of seizure of any warship under construction for a belligerent country.

At last, she could obtain coal and depart after the armistice of February 18, 1868 was signed between Spain and Chile, it should be noted that ships for Chile were also in construction and were unblocked afterwards.

In 1871, Arapiles was assigned to Spanish Algiers station trying to protect nationals after Kabyle revolution (border tribes), taking advantage of the Franco-Prussian War. Indeed, the city was part of the French mandate in the former “Barbary state”. Once her mission was completed, she was sent to the maritime exhibition in Naples, representing Spain during an international archaeological commission of scientists embarked that was about to depart for the Near East, and she was in escort as well as to “showing the flag”, after more than 80 years without any Spanish warship in those waters. The Spanish plan was just to acquire pieces from this area for the national Museum, the newly founded National Archaeological Museum of Madrid.

After completing this scientific expedition, Arapiles sailed to Spanish Havana. In 1867, she suffered a serious machinery breakdown while off the coast of Venezuela. She was transferred to Fort-de-France (French Caribbean) for emergency repairs, to be completed later in New York. There in Martinique, the crew learned by newspapers about the Virginius affair.

The Virginius Affair was a diplomatic dispute from October 1873 to February 1875 between the United States, Great Britain and Spain about the control of Cuba in the ten Years’ War. Virginius was a fast American ship hired by Cuban insurrectionists, used to land men and munitions in Cuba. It was captured by the Spanish which put the men on trial, some being American and British. They were declared as pirates and sentenced to death, all 53 being hanged before they could be saved by the British governor.

The affaur created an outrage in the US and there were concerns the latter might declare war on Spain. Lengthy negotiations were unlocked as there was a change of regime in spain, and in the end, US consul Caleb Cushing negotiated $80,000 in reparations paid to the families of the executed Americans. British families had been already compensated prior. The peaceful settlement implemented by US Secretary of State Hamilton Fish avoided a costly war between the United States and Spain, that was not going in favor of the former on paper, naval wise. The Virginius Affair started also a new interest in the US Navy, or more precisely, the need to beef it up. It was in 1898 when the US ultimately declared war this time.

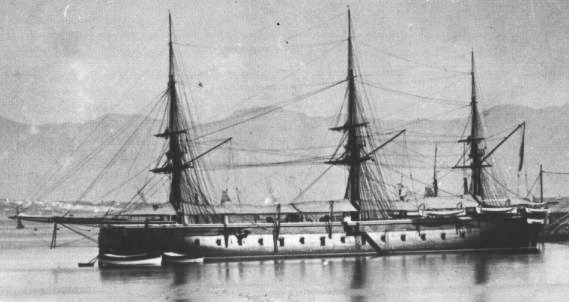

Arapiles in drydock repairs La Havana 1870

Arapiles’ repairs in New York were thus cancelled until the following spring, and by the fall of 1872, stormy weather prevented her to depart. Instead, after repairs, she sailed back to Guantánamo of Cuba. In May 1873, she set sail at last for New York with the steamship Isabel la Católica for full repairs. By January 23, 1874, she departed again for Havana, and stayed on station until 1878. At that stage, the jot and humid local climate had not been tender with her wooden hull.

The crew already could see it was riddled with various bugs and worms, and a commission examined her in detail, concluding her hull seemed in effect rotten. But it was considered safe enough to sail for Spain and undergo the complete modernization she needed.

To be certain, the construction inspector asked to remove the armour to examine the hull underneath. The naval staff thus decided to have her provisionally discharged from the Navy, and she was decommissioned in 1878. Soon after, she was berthed so that her armour could be removed, exposing the inner hull and conforming the worst fears. Her poor condition forced this time the official cancellation of her reconstruction planned for 1882. Instead, she was likely scrapped in 1883 or 1884 at the arsenal of La Carraca in Cádiz.

Read More/Src

Books

Spanish Ironclads Tetuan, Mendes Nunes and Arapiles”, p. 408

“Richard Green statue”. PMSA Public Monuments & Sculpture Association. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014.

Brassey, Thomas (1888). The Naval Annual 1887. Portsmouth, England: J. Griffin.

Lyon, Hugh (1979). “Spain”. In Gardiner, Robert (ed.). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1860–1905. Greenwich: Conway Maritime Press

de Saint Hubert, Christian (1984). “Early Spanish Steam Warships, Part II”. Warship International.

Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World’s Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books.

Spanish Ironclads Tetuan, Mendes Nunes and Arapiles”. Warship International. XI (2): 407–408. 1974.

Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1979). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1860-1905. Greenwich: Conway Maritime Press

de Saint Hubert, Christian (1984). «Early Spanish Steam Warships, Part II». Warship International

Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World’s Capital Ships. NY Hippocrene Books

Links

books.google.f

todoavante.es

alojados.revistanaval.com/

es.wikipedia.org/ Arapiles

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign