The shortest lived French cruiser

The Pluton (formerly La Tour d’Auvergne) was the shortest-lived French cruiser of WW2: Commissioned in May 1931, she served eight years, until her accidental explosion in September 1939, just 12 days into the war. But Pluton was also an oddity, the first “special service” cruiser of the French navy, tailored as a fast minelaying cruiser, fast troop carrier and later converted as a gunnery training ship to second the cruiser Jeanne d’Arc.

In 1920, the naval staff was convinced the German fast minelayer cruisers were an interesting idea, and at the same time on the other side of the channel, the British HMS Adventure (started 1922) was built. Alongside the construction of minelayer submarines, they ordered studies of a cruiser able to perform minelaying as a primary task. The main requirement was speed, armament and protection were secondary, and she was to be light. Eventually an order was authorized under the 1925 programme, but development took some more years, and she was voted by the parliament FY1928.

Arsenal de Lorient on the West coast was awarded the contract. This shipyard was quite experienced in cruisers, despite having a single basin large enough, delivering to the French navy the Lamotte-Picquet in 1924, and Tourville in 1926. Therefore two years later, the keel was laid down in April 1928. She was built in just a year and a month, launched in April 1929, but fitting out and redesigns led to a late completion in January 1932, so more than two years after.

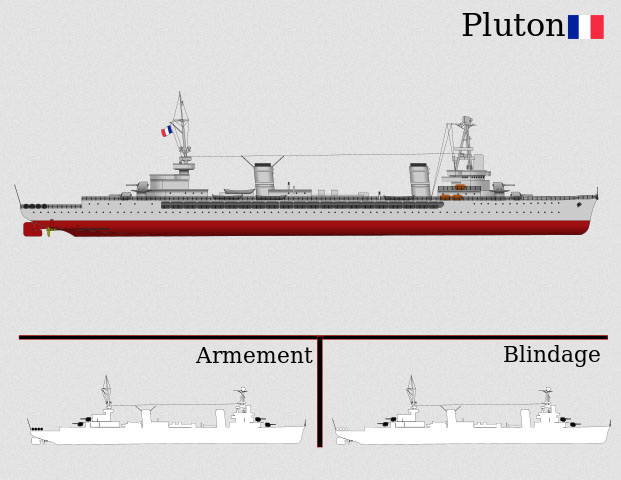

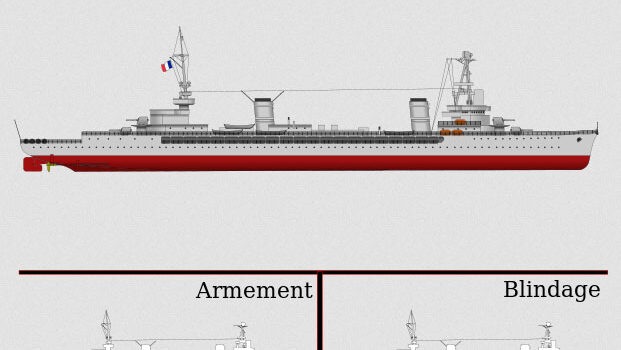

creative commons Illustration by rama, rather inaccurate, but showing the general outlines and armour/armament locations.

Her launch name was Pluton (‘pluto’) after hell/underworld’s god also called Hades. But when it was decided to convert her as a gunnery training ship she was to be given the unusual name “la Tour d’Auvergne”, unique to this cruiser and never used again in the Marine Nationale. It was related to Henri de La Tour d’Auvergne better known as Turenne (1611-1657), a famous Marshall of King Louis XIV. Two ships in the French navy were named Turenne, a 1854 100-gun ship of the line and a 1879 Bayard-class masted battleship.

Design of Pluton

Pluton was a tather small cruiser, 152.5 m (500 ft 4 in) long overall and 15.5 m (50 ft 10 in) at her largest beam, for a draft of 5.2 m (17 ft 1 in). For the first time in France, she used some aeronautical techniques, and her hull used extensively Duralumin, a metal composite used in aviation for the superstructure. This was to save weight and lower the metacentric height to make her more stable, but this resulted in corrosion, as well as strength issues. She was also unusual in that she had with a single counterbalanced rudder, powered by a (rather weak) electric motor. Her turning circle was of 875 m (957 yd) with 25° port/starboard hard over, and at 27 knots (50 km/h; 31 mph). This was not impressive, especially in comparison to the much larger cruiser Duguay-Trouin.

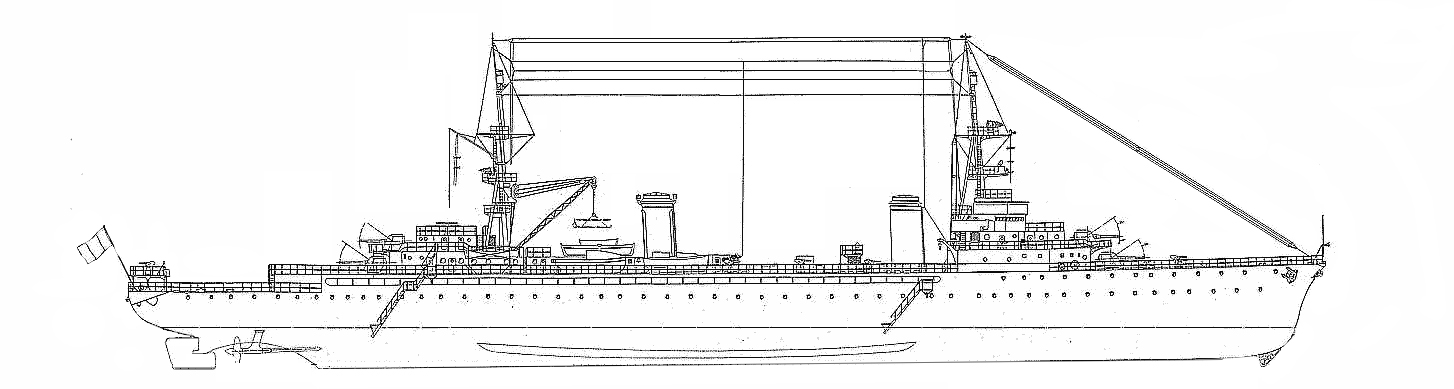

Original blueprints of the Pluton, as a minelayer. Her appearance changed when she was converted as a training ship. Her side gangways notably were plated over and the internal railings eliminated (see later), armaent was modified, fire direction also and the forward tripod expanded, the hull reinforced, etc. She spent years in drydock, further reducing her active service.

Protection

Assuredly this was the weak point of the design. She was largely unprotected, relying upon watertight subdivision to survive a torpedo hit or shell hit punching below the waterline. For this, she had was given a longitudinally framed hull subdivided by 15 transverse watertight bulkheads. This ASW passive protection was seriously tested when the ship exploded and her weak construction did not survived the blast. For extra flood protection, her two-shaft machinery layout used the alternating boiler and engine rooms scheme. That way if one section was flooded, the ship still had a workable turbine and boilers to move out of harm. Also in case magazines were heated by fire, there was an additional auxiliary boiler fitted specifically to cool the ship’s magazines (or heat them in winter), as well as providing tap water.

Powerplant

It was specified for this cruiser a top speed of 30 knots. To achieve this, Pluton was given a rather conventional cruiser propulsion, but with lighter than usual turbines: Bréguet (yet another aeronautical reference, this was a renown aircraft manufacturer) single-reduction impulse geared steam turbines. These turbines were fed by steam provided by four du Temple boilers working at a pressure of 20 kg/cm2 (2,000 kPa; 280 psi). This ensemble provided an output of 57,000 hp, enough to procure the 30 knots (56 km/h; 35 mph) as designed.

Each propeller shaft ended with a three-bladed 4.08 m (13 ft 5 in) bronze propeller and on trials, Pluton reached 31.4 knots (58.2 km/h; 36.1 mph). This powerplant was supplied with 1,150 t (1,130 long tons) of fuel oil. It was originally planned to provide her enough legs for 7,770 nautical miles (14,390 km; 8,940 mi) at 14 knots (26 km/h; 16 mph). However, this proved too optimistic and after many design revisions, it was downgraded to just 4,510 nmi (8,350 km; 5,190 mi) in service.

Indeed what was overlook, her auxiliary machinery proved thirstier as expected. For electric apparatus on board she also carried a pair of 200-kilowatt (270 hp) turbo generators, provided 235 volts and two 100-kilowatt (130 hp) diesel generators, mounted in the aft engine room to provide. This provided energy while anchored, machinery cold. A third diesel generator was also installed in first deck compartment, to be used if the former failed or were submerged, or tapped for other uses, although it was devised for emergency purpose only.

Armament

For a cruiser, the Pluton was rather lightly armed, much in line with the British HMS Adventure but better, with 5.5 in versus 4.7 in guns. The AA was rather generous and diverse, much like on the Jeanne d’Arc with three calibers ranging from 3-in to 0.5 in (13.2 mm). But of course the raison d’être of this cruiser were her mines: She carried 290 of them, of the classic contact type. This was the same as the Adventure, carrying 280 P Mk.III (large pattern) to 340 of the small pattern model.

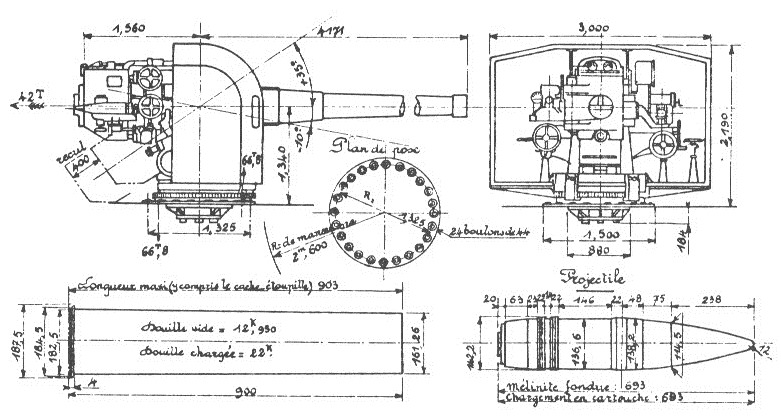

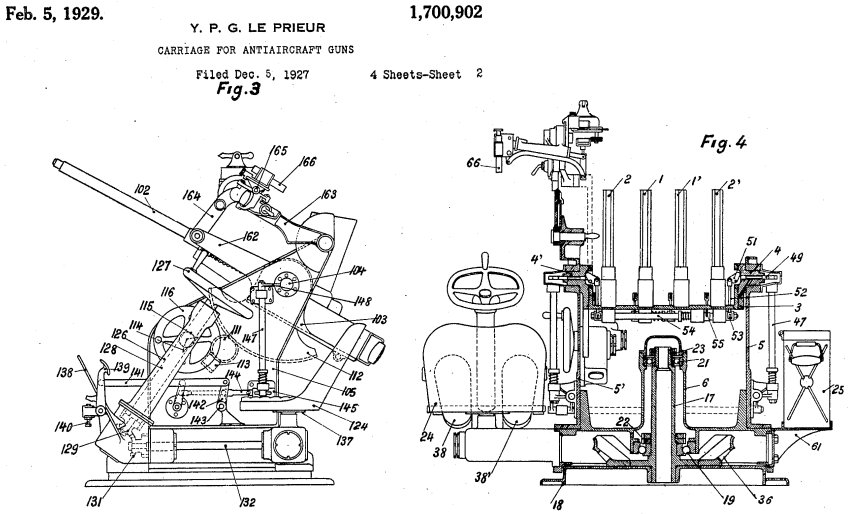

Technical scheme of the 138.6 mm Model 1923 Mounting and Ammunition, from the collection of Robert Dumas

Main guns:

Four 5.5 in/40 (140 mm) model 1927 main guns, in superfiring positions fore and aft. This was a heavy destroyer gun model, which carried quite a punch but had issues. Only the 2400 tonnes large destroyers of the Bison class had them. Exact caliber was 138 mm but they were referred as 14 cm in French ordnance. The gun used a Welin breech-block. This was a rather unsatisfactory design with a slow rate of fire. it was derived from the already unsatisfactory 130 mm Model 1919. Their mountings had raised trunnions, allowing better elevation but a difficult loading at lower elevations. This mount procured a -5° +28 ° elevation, 300° traverse. It used the standard SAP 40 kg modele 1924 QF ammunition. Theoretical rate of fire was 8-10 rpm, in service this was more 6 rpm. Maximum range was circa 16,600 m at a muzzle velocity of 700 m/s. 150 shells per gun were stored, in four separated magazines and hoist.

Quad Hotchkiss 13.2 mm with Le Prieur mounting.

Interestingly enough, the initial design studies showed two single 203 mm turrets (like contemporary Japanese and Russian cruisers) fore and aft, like on a monitor and the same AA (less 13.2 mm guns). However in the end it was found more judicious to have a quicker firing artillery to deal with destroyers, and four 138.6mm guns were adopted during construction which imposed modifications.

AA armament:

It was split between four rather classic 3-in/60 AA guns (75 mm) after reconstruction. using proximity fuse shells, installed under enveloping shields along the sides amidships, and two remaining single 37 mm guns in the superstructure, and six 8 mm Hotchkiss Mle 1914 twin machine guns. They were already obsolete in 1928, and mounted above the gangway (2) and above the machinery cooling chamber (2) the last two in front of the mainmast. 48,000 cartridges were stored. They were eliminated in 1932 and 13.2 mm models were installed instead.

These were three quadruple “chicago piano” 13.2 mm heavy machine guns. The 75 guns had a maximum depression of -10° to 90° elevation, fire 5.93 kg shells at 850 m/s, at 6-18 rpm at a maximum ceiling of 8,000 m. The Hotchkiss quad 13.2 mm had a planned cyclic rate of 450 rounds per minute, 200/250 rpm in reality because of reloads. Max ceiling was 4,200 m, but closer to 2000 m in reality. Also during the 1932 reconstruction, a simplified fire control system was added for the 138 mm guns, and 15 additional sights.

Six (or ten for another source) semi-automatic 37 mm were part of the final design and no 75 mm guns, all with protective shields. Two were mounted on the superstructure, six between the funnels on the main deck, two on the aft quarter deckhouse. 10,000 shells were carried, 144 ready-round in ammunition boxes close to the guns on the deck. The mount elevation was −15°-80° and they fired 725g AP shells at 810 m/s. They were effective against planes below 5,000 m, but this was all planned, but not realized: Only the two aft guns were preserved in 1932.

There never was a torpedo tube armament planned.

Mines:

Here are following naval mine models used in the interwar, potentially used by the Pluton.

–Bréguet mines, B2 (1916) still in storage but mostly B3 models (1922). The latter were Lever-fired and 0.865 m (34 in) in diameter, 670 kg (1,477 lbs.) with a 110 kg (243 lbs.) Mélinite charge.

–Sautter-Harlé modele H3 (1922) switch horn type, diameter 0.75 m (34 in), 670 kg (1,477 lbs.), 110 kg (243 lbs.) Mélinite charge.

–Sautter-Harlé modele H4/H4AR (1924) 1.04 m 1.13 ton coastal mines, but more likely

–Sautter-Harlé modele H5/H5AR (1928) Five switch horn type 1.04 m (41 in) 1,160 kg (2,557 lbs.) 220 kg (485 lbs.) TNT charge

–Sautter-Harlé modele H5UM1 and H5UM2 (1935) Four switch horn type, same but 500 m (1,640)-180 m (590 feet) mooring cable.

–Sautter-Harlé modele H6 (1939) larger four switch horn type, 1.15 m (45 in) 330 kg (661 lbs.) TNT.

Pluto was designed to carry 220 to 250 Sautter-Harlé mines initially, stored on the first deck called “mine deck” occupying 3/4 of the total length of the ship. The sides were open, but could be closed by panels. The same space was used for troops in that configuration. These mines were placed on chain hoists, using a system of four rails. Each rail pair converged on a turntable forward, with a gear connecting the two plates. The latter allowed to load mines more easily from one side and also to move them from rail to rail. The tracks ended aft at the poop, with the four ramps sloped down to 30°, in order to minimize the risk of an impact and quick laying when released. In alternative, up to 270 smaller Breguet mines could be loaded on the same system.

⚙ specifications |

|

| Displacement | 5,300 t. standard -6,200 t. Full Load |

| Dimensions | 152.5 m long, 15.5 m wide, 5.2 m draft |

| Propulsion | 2 shafts Breguet steam turbines, 4 FC Gironde and Normand boilers, 57,000 hp |

| Speed | 30 knots |

| Range | oil 1200t, 4,510 nm at 14 knots |

| Armament | 4 x 138 mm/40 M1927, 2x 47mm/40 M1885, 10 x 37mm/50 M1925 AA, 290 mines, see notes |

| Protection | 15-20 mm max |

| Crew | 424-513 (+1000 troops) |

The very short career of Pluton

Pluton was completed at Lorient for the cost of 102,671,658 francs, on 25 January 1932. She entered service in the Mediterranean squadron but encountered a serie of issues with her machinery, in particular excessive vibrations, a classic problem identified on powerful ships with a frail construction. After some strengthening, Pluton was given the role of artillery instruction and was to be modified to be a gunnery schoolship. The naval staff indeed considered destroyers and smaller dedicated ships were more efficient at minelaying and the cruiser Jeanne d’Arc needed some reinforcement for training cadets.

So Pluton was to be scheduled to replace the elderly armoured cruiser Gueydon (1903) and was reconverted accordingly. This was not planned initially. She was sent in drydock in on October 24, 1932. For this, new accommodations for 40 cadets is constructed in the mine deck, most 37 mm anti-aircraft guns and all the obsolete 8 mm Hotchkiss machine guns were deposed, and four 75mm guns AA are installed instead. In all, this represents 24 anti-aircraft guns plus six twin 13.2 mm Hotchkiss machine guns in quad mounts, two in place of the 37 mm guns, and four between the funnels.

Pluto’s modernization and reconstruction dragged on until 1935. She was upgraded four times during this period, with superstructure reinforcement, protection against damaged by the muzzle flame of the 138 mm guns (the duralumin catch fire quite easily), and replacement of corroded aluminium ladders and booms by steel. Also wide-angle fire direction systems are mounted to direct fire of their new 75 mm guns, of which two are converted to remotely controlled guns, the rest having masks to protect the gunners from their muzzle blast. Later, the mine deck was modified again to receive accommodations and facilities for 40 more men, so 80 total.

In 1936, she was returned to active service, and during a maintenance stop, she receive an experimental 13.2 mm twin mount, placed between the 75 mm starboard guns. The machines were overhauled in turn, starting in November 25, 1936 and completed on 13 March 1937. The turbines were overhauled and fire direction systems for the main artillery was upgraded to the ones used on the light cruisers of the Duguay-Trouin class. 13.2 mm machine guns were relocated in the superstructure. On November 15, 1938-February 15, 1939, more modifications were made to the machinery and artillery.

Orders, counter-orders, disorder

Shortly before the start of WW2, there was an urgent need for more offensive vessels, and Pluton she was taken in hands to be reverted back to her original role (and renamed La tour d’Auvergne in the process). For this, most of the gunnery training equipment was removed. Now a minelayer again, she was mobilized in the summer of 1939, to be integrated into the Brest squadron, after her service in Lorient in May to replace the cruiser Jeanne d’Arc as training ship.

After a report, not confirmed by British intelligence, the French Admiralty believed German battleships just sailed out to operate in the Atlantic, and that an attack on the Moroccan coast was a real possibility. Pluto was ordered to establish a defensive minefield against submarines notably at some strategic locations off the coast of Morocco. Pluton left Brest, with the Raid force on September 2, loaded with 125 Bréguet mines. She arrived in Casablanca on September 5 and moored at the Delure jetty, made ready to lay mines during the night of September 11-12. Later it appear the German battleships were spotted still at their anchorage and the threat now gone. The admiralty decided to repatriate the Atlantic squadron and Pluto to disembarked her mines at Casablanca and depart to join it. The Commander at Casablanca, Rear Admiral Sable, gave order on the morning of September 13 to start the mines unloading process.

The Pluto accident

Operations started at 10:30 am under direction of Captain Dubois of the Pluto. It was under supervision of Lieutenant Le Cloirec, the onboard head of underwater weapons department. Ten minutes later, a long flame burst suddenly from the rear deck with a loud bang. Pluto is enveloped in a huge cloud of dust and smoke, while suddenly she is rocked by a second explosion which rips apart the bridge and a ball of flames immediately engulfs the aft part of the ships. This terrible explosion not only destroyed most of Pluto, killing dozens instantly, but the blast wave and falling debris also killed many sailors on neighbouring ships and on land. Fuel oil spilled and ignited, and further expanded the catastrophe. The detonation was loud enough to be not only heard throughout Casablanca but well beyond. Many windows were smashed in town and nearby ships at 1,000 meters of distance.

Order is given to the twelve French submarines in Casablanca to set sail at 10:53 am to avoid more destruction in case other mines explodes. Two minutes later, Pluto started to lost to port and sinks slowly. At 11:07 am, port authorities are denying entry by signal and at 11:15 am, Pluton had now sank to the bottom, her superstructure still emerging but both decks completely underwater, including the mine deck.

Needless, there was an enquiry to determine the nature of the explosion the following days.

Sailors onboard the Polish ship Iskra and cadets on a dinghy rowing about 150 m abeam of Pluto, observed a first explosion between the aft funnel and mast, ignition of a boat docked at the stern, followed by a loud bang blasting the stern, up to the aft gangway and upper deck. The dinghy would saved 3 injured men, and picked up 19 other wounded men, disembarked on the jetty, giving first aid, soon joined by 3 French Navy doctors.

Lt. Le Cloirec’s reported also that at the time of the explosion, he was with the quartermaster electrician preparing crane B for picking up the mines, and he had time to see before falling the fall of the aft mast. He was caught between between the front funnel and the front superstructure, and channelled men to evacuated the mine deck with the master gunner. He would later phoned near hangar 10 for more help and met the Chief of Staff in Morocco relating the arrival of ambulances and medical personnel. Soon after as he was returning back from the ship again, he saw one of the munitions stores blow up. In addition to the circumstances he mentioned significant losses in the machinery personal but also the heroism and dedication of certain sailors.

The causes of the accident as determined by the Commission of Inquiry, ruled out underwater attack or criminal act and found the most likely cause was the accidental explosion of a mine, during the dangerous defusing operation. According to Naval Headquarters and Technical Department “whenever possible, embarkation and disembarkation of mines is done directly, without going through the intermediary of barge. This jumped step minimized the dangers of mishandling but also that mines must be defused on board. It was established the second explosion was likely been caused “by influence” after the first mine exploding.

The responsibility of the personnel of the cruiser Pluton and its Commander was not put into question, as the Navy commander in Morocco, when it was shown all the security arrangements has bee made. Police was present on the landing quay, and handling of landed mines carefully monitored. It was established mine security was an issue in itself, such devices remaining by their very nature, extremely delicate to handle. Therefore it was attributed to a probable human error, with all the immediate personal and proofs been literally anihilated, not firm conclusion about the precise, exact cause of the mishandling would be put forward.

In a letter dated September 19, 1939, Frigate Captain Benac, Second in Command onboard Pluton, sends his own report to the Rear Admiral in Morocco, where he cannot give an exact number of those on board during the explosion. The crew listed 17 officers, 494 crew and one hospitalized ashore, and for a total of 512, he certifies the crew present was no greater than 497. On 8 December 1939, the Directorate of Military Personnel of the Fleet sent a report to the General controller and head of the administrative section of the office of the Minister of the Navy, a name listing the missing officers and gratings present during the explosion, which included 9 officers including the captain, 162 petty officers, quartermasters and sailors, all “presumed missing”.

Captain Rostand, head of the historical service established a more precise list in 1956, establishing 10 officers killed or missing and 2 wounded, 186 KiA or missing in sailors, and 73 wounded, for 497 men. On land, the marine personal suffered also, with 1 officer killed, 1 wounded, 19 men killed or missing and 29 injured and a wounded officer on the Polish TB Wilja nearby.

The final list for the families, included 9 officers including the Commander, and 173 crew members.

Conclusion:

The tragedy of Pluton, barely a few days into the war, and quick enquiry due to more urgent matters at hand, was never balanced by a new enquiry afterwards. It simply indicated there was no great mystery about the main reason of the tragedy. Manipulating mines, whether on a ship, at sea, or on land has always been a risky operation. But the real environment leading to the catastrophe could have been the hesitations of the naval staff preceding this order. Incorrect reports were to blame, as German ships to reach north Africa would have been a very long and risky route through get there in the first place.

It would have been safer to simply lay a minefield on a strategic spot, but it’s symptomatic of the frenetic micromanagement of the French high command at that time, which only be more acute in May 1940 and rapidly showed its limits. It is certain there was some urgency to unload mines in order to join the Force de Raid as soon as possible, and this potentially caused some pressure in the crew to perform the operation quickly. Was the crew trained to perform this operation also ?

There will be some gaps in the enquiry as the exact composition of the handling crew inside the mine deck would forever stays unknown. In peacetime indeed, unloading mines was a much longer process, using for added safety a barge alongside the ship, which was anchored at a safe distance of the quay just in case of an explosion. This two-step process was lengthy, as barges needed newt to unload their mines on land. But by wartime, there was just no time for such procedures, and in addition, the mines were not diffused in case order was given to lay them at any moment. They had been previous prepared for such occurrence. The defusing was of course a precaution to ensure during the handling by a crane, any shock of the mine with its surrounding would have no consequence.

Note: Apart the single private coll. photo released in CC of the wreck after the explosion, all official, existing photos of the Pluton are property of Marius Bar coll. Toulon. I can’t show them on this website, but you can see them here on the publisher’s catalogue. All existing photos on wikimedia commons had been retired, about 90% photos of French ships of the interwar.

Pluton’s wreck along the berth in Casablanca, September 1939.

Author’s Illustration profile of the Pluton in 1939, showing her after transformations as a training ship, and reverted back to a minelayer

Src on Pluton/La Tour D’Auvergne

Books

Gardiner, Robert (toim.): Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1922–1946.

Whitley, M. J.: Cruisers of World War Two – an international encyclopedia.

Campbell J.. Naval weapons of World War Two. Annapolis, Maryland, 1985.

Jordan, John & Moulin, Jean (2013). French Cruisers 1922–1956. Barnsley, UK: Seaforth Publishing.

Osborne E. W. Cruisers and Battle cruisers. An illustrated history of their impact.

Smith P. C., Dominy J. R.. Cruisers in Action 1939 – 1945. London, 1981

Whitley M. J.. Cruisers of World War Two. An international encyclopedia. London, 1995

Notes: Vincent-Bréchignac 1930, p. 30, Guiglini et Moreau 1992

J. Guiglini, A. Moreau “Les croiseurs Jeanne d’Arc et Pluton” (Marine éditions).

Books

on en.wikipedia.org/

on navweaps.com FR Mines

navweaps.com FR 155mm/40 m1923

on netmarine.net/

alabordache.fr/

on navypedia.org/

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign