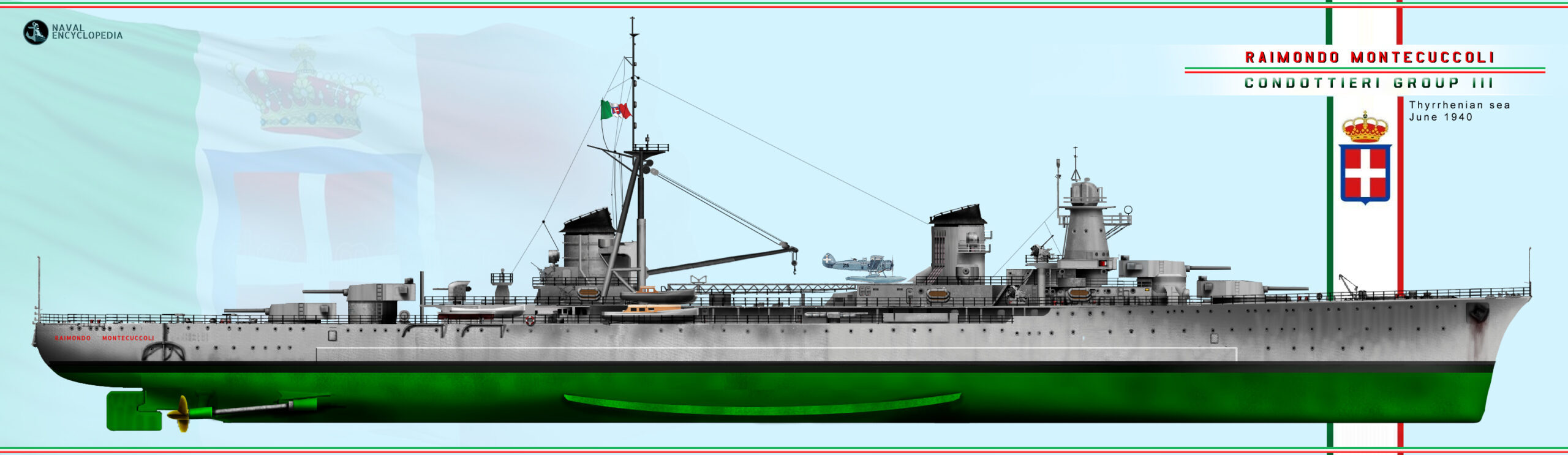

Group III “Condotierri” light cruisers

Italy (1934), Raimondo Montecuccoli, Muzio Attendolo

Italy (1934), Raimondo Montecuccoli, Muzio Attendolo

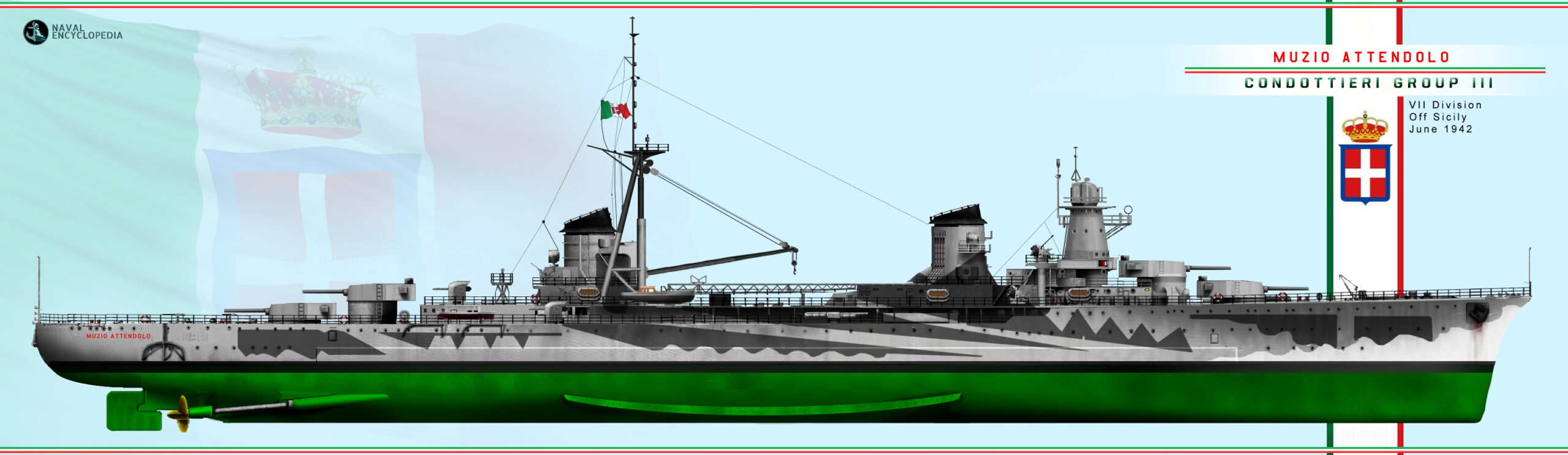

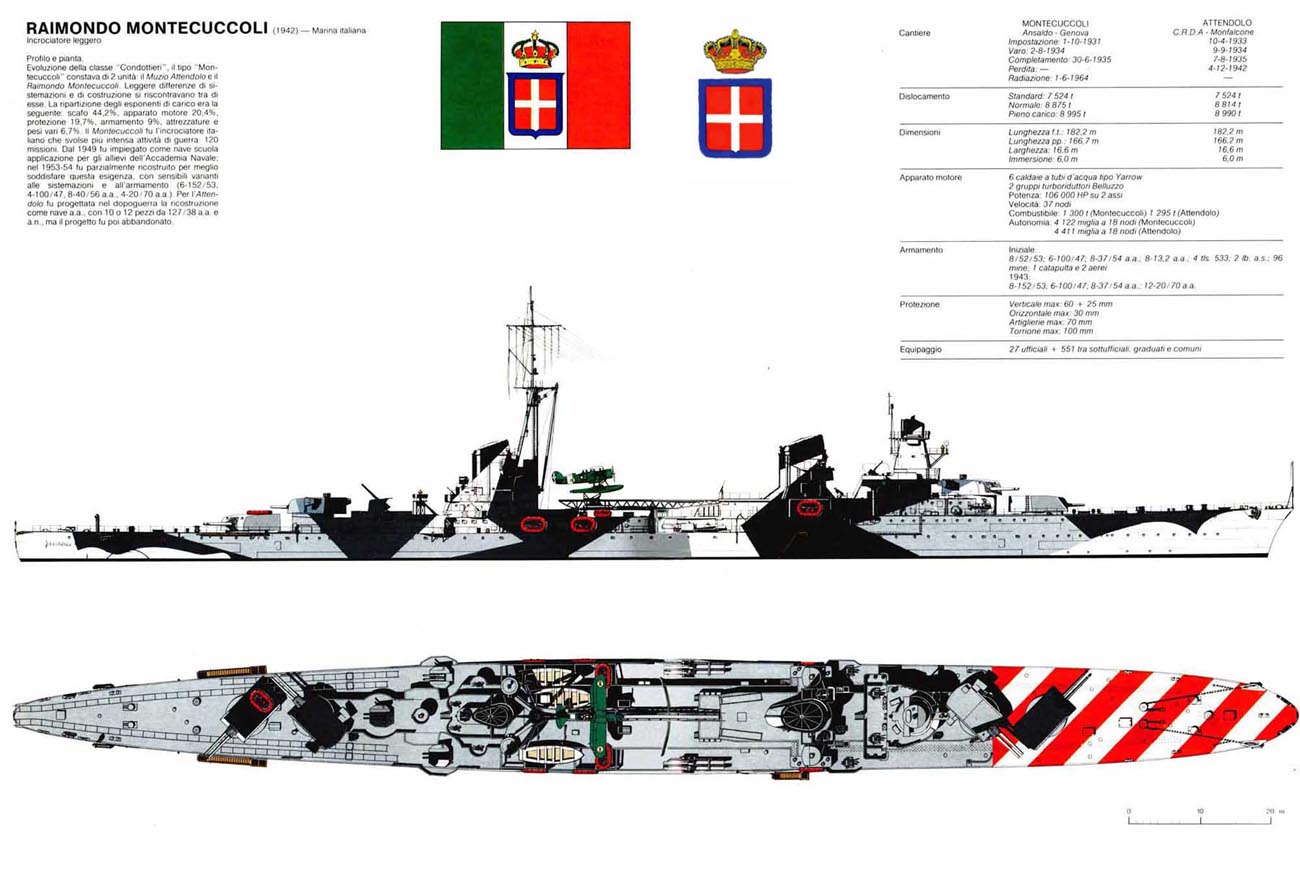

A brand new cruiser design

The four cruisers of groups III and IV were relatively similar, the Raimondo Montecuccoli class (with Muzio Attendolo), and the Emanuele Filiberto Duca d’Aosta soon after all were launched between 1934 and 1935. They were all very similar in design and appearance but differed in size, displacement and many details which explains most authors had them seperated in their own sub-classes. The Raimondo Montecuccoli class was designed from 1932, and became a real game changer, under treaty influence and in particular the Treaty of London in 1930. They constituted a complete break over previous classes of the Cadorna/Guissano, “destroyer killers” to that of fleet cruisers, more useful to the fleet with a better armament, protection and range to the price of speed.

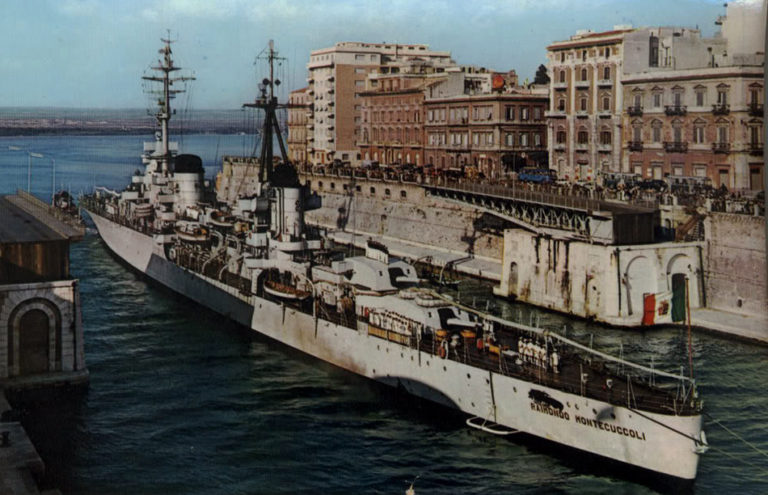

Raimondo Montecuccoli in Venice before the war.

The Montecuccoli class cruisers can be considered the first light cruisers built by the Royal Navy, in fact the previous 5000t were essentially large esploratori or scout cruisers. They were designed in 1931 and presented good protection, despite having a very high speed thanks to the extremely refined shapes of the hull. These units turned out to be excellent vessels with a remarkable speed, RN Montecuccolli exceeded 38 knots on sea trials and was considered having a sufficient protection foe the time. Both were intensively used as minelayers thanks to their two deck rails, for 130 mines of various types.

The lead ship was built by Ansaldo Yard (Genoa), named after a 17th-century Italian general in Austrian service. Muzio Attendolo was built at C.R.D.A., Trieste, laid down on 10 April 1931, launched on 9 September 1934 and commissioned on 7 August 1935, named after the 14th-century ruler of Milan and founder of the Sforza dynasty.

The previous Cadorna class, for comparison (ONI)

Raimondo Montecuccoli entered service in 1935 with the VII naval division, participating in numerous battles, as Punta Stilo and mezzo guigno, escorting convoys and laying mines. Her last wartime trip was from Genoa to Malta on 10.9.1943 as she handed herself over to the British after the capitulation. She carried out numerous missions during the co-beligerance era still, remaining postwar a valuable asset, modified into a training ship and modernized, to be stricken by June 1964.

Muzio Attendolo entered service in 1935 too, joined her sister at the VII naval division and also did her share in the same missions and battles. On her way to Messina after a cancelled attack on a British convoy to Malta, she was hit as Bolzano, by torpedo launched by HMS Safari. Her bow was ripped off but she managed to return to port, receiving a makeshift prow before making a new crossing to be fully repaired. despite of this she was sunk at quay in Naples, never having the time to return to service.

Montecuccoli colorized by irootoko Jr.

Very active in WW2, Montecuccoli survived the war, was modernized twice after it and served in the cold war until 1972, while Muzio Attendolo was sunk on 4 December 1942 in Naples by USAAF bombers on 4 December 1942, and salvaged after the war, but it was decided the damage was not worth repairing her, and she was scrapped. Leaving her the only one of the four cruisers of Group III-IV not to survive the war.

Design

Hull design and general construction

Forward and aft view of a scratchbuilt model (Flickr)

The Montecuccoli class for a start was far larger than the Cadorna, with a 182.2 m (597 ft 9 in) long hull (compared to 169.3 m or 555 ft 5 in), a one meter larger beam at 16.6 m (54 ft 6 in) versus 15.5 m (50 ft 10 in) and deeper draught with 5.6 m (18 ft 4 in) versus 5.2 m (17 ft 1 in)). The lenght ratio was even more favourable, together with finer hull lines at waterline level. This traduced into a much higher displacement of 8,875 tonnes standard and 8,895 t fully loaded, versus 5,323 t/7,113 tonnes. Note that acording to the London treaty of 1930, the tonnage of a light cruiser was understood as 7,500 tonnes standard. This was above average, as contemporary French cruisers (Bertin at 5,880 tons standard for example and the following La Galissonière) were 7,600 tonnes standard.

In addition to a great lenght, the hull was more rectangularly, fuller shaped than on the Cadorna class. Another interesting part of the design, other than that the longer hull, still with the trademark, large flare making the forward part looks much wider than the stern. This excessive flare was helping keeping the deck dry as much as possible, but would not have been a good idea in the Atlantic where cutter style prows were more in demand.

From forward to aft, after the clipper bow and its unusually large flare, were located the two anchor chains and capstans, followed by the main turrets A,B, superfiring, the forward superstructure encompassing the B barbette, the conning tower and bridge in a single unit, located right above B roof level. This simple, low bridge supported the main fire control station on a platform. It had wings either sides. The single bridge was open initially, then enclosed after completion. No proper mast but a small one to support radio cables coming from the main mast aft and hoist signals, including the radiodetection antenna.

Usual practice at the time, behind the fore funnel, surrounded by the two forward secondary armament FCS turrets, was located on the superstructure’s roof the single main aircraft catapult, with enough space port and starboard, at the foot of the forefunnel, two spare floatplanes with fokding wings as spares. They were on a raised platform -by default of a crane here- to be placed with ease of the catapult’s tip.

At the foot of the superstructure were located amidship on the main weather deck the two torpedo tube banks. Services boats were installed behind, on both sides, and served by the main boom crane anchored on the fore mast of the main tripod aft. The latter comparised a platform and supported others with the aft secondary FCS and night projectors. The secondary armament, comprising, as on previous cruisers, three twin turrets, were located port and starboard on sponsons, and an axial one, on the quarterdeck superstructure aft, followed by X and Y turrets also in a superfiring pair.

All in all, these cruisers looked much elongated, with little room to spare forward and aft of the main turrets. This was corrected both on the contemporary Zara class, and the successor Group VI, Duca Degli Abruzzi class.

Powerplant

On sea trials

The propulsion system benefited from a larger and longer hull, but still consisted of a generally similar powerplant as the previous Cardona class, with two identical units consisting in two steam generators, connected to a turbine group, the whole being housed in three separate rooms: One for the turbine, two for the generators, placed one behind the other in the center so as to avoid a single torpedo hit to flood the entire machinery spaces.

Each power unit comprised in reality a combined turbine: A high-pressure turbine was combined with a low-pressure turbine, both of the Belluzzo type. Direct action, with rapid reverse running was enabled, as connected by a gearbox to the shaft line. The forward group drove the starboard propeller right-hand and the aft group, left-land, with three bladed three meters diamters bronze propellers. Below the turbine group was installed the low-pressure condenser cooled with sea water. It could operate the turbines in a closed circuit. To compensate for the loss of distilled water, three evaporators were capable of producing 154 tonnes of the latter over twenty-four hours.

For the boilers, which were of the Yarrow type, superheated steam generators worked at 225° C. The watertube boilers had five collectors and were capable of producing 90tonnes per hours of steam pressure. The combustion chamber for each generator was provided with by twelve nozzles, and spread oil was heated up to 90-100°C. Fumes from the two stern generators were evacuated were truncated into the aft funnel, and the forward ones in the corresponding forward funnel, both rounded, same size, slightly raked, provided with a cap, and widely spaced apart, a clear recoignition sign. Steam generators were fed with distilled water preheated to 100°C by the auxiliary turbines.

All in all, this powerplant provided 120.000 hp, compared to 95,000 for the Cadorna, enough to reach 37 knots (same). On trials Montecuccoli exceeded her contract speed even reached 38.7kts, on however a displacement less than standard, plus machinery pushed 18% above normal figures. In service, fully loaded she never ventured beyond 34 kts. These cruisers carried 1,300 tons of oil (versus 1,230 tons) for a max range of 4,122 nmi (7,634 km) at 18 knots (21 mph; 33 km/h), versus 2,930 nm for Cardorna, an 1/3 increase allowing them a broader specter of missions with the fleet.

Protection

ONI plate, showing the armour layout

Protection was entrusted to two nichrome steel walls: There was an external one of 60 mm and an internal one of 25 mm amidships, plus 30 mm in correspondence with the main barbettes, spaced from each other by 1.60 m. It should be noted that while the protection of the Italian cruisers covered about 75% of the length of the ship, in practice from the first forward barbette to the last one in the stern, it left only secondary importance compartment unprotected. British cruisers copmparatively had protection that covered only 30% of the length, leaving ofter ammunition stores for thee main turrets unpritected. The main problem with these ships was undoubtedly poor effectiveness of the turrets, even as engineers were not enthusiastic as topweight was already reduced by opting already for single cradles (fixed dual mounts) to the risk of high interference and poorer accuracy.

Being larger and better protected meant an increase of 1,376-tons (18.3% of her displacement) destined to armour, compared with 8% for the Cardona, a three time increase.

Still not impressive for a cruiser (the belt could barely withstand a destroyer AP round), it was less appalling compared to the early “tin-clad” cruisers, and was radically improved on many levels with this new class:

-Main armored Deck: 30 mm thick (1.2 in). It topped the main belt at waterline line, with slopes reaching that same thickness. The weather deck above was mildly protected. But there was not extra protection for the ammunition storage deeper in the hull or steering gear.

-Main Belt amidships: 60 mm thick (2.4 in). It was all all or nothing scheme, extending as along as the barbette. Beyond it the hull forward and aft was not protected.

-Main turrets: 70 mm (2.8 in). This was for the sloped front and sides only. The roof and back were more lightly protected, likely 30 mm (1.2 in).

-Conning Tower: 100 mm (3.9 in). The walls had this thickess (roof included), but thinner below the armored deck (thickness unknown).

To put things in perspective that was compared to 20 mm (decks), 24 mm (belt), 23 mm (main turrets) and 40 mm (CT) for the previous Cadorna. The extra addition was in the ship’s size, which was larger, with more surface to cover as well. The Montecuccoli’s funnel crowns and uptakes, main bridge or superstructures were not armoured.

Armament

Main: 4×2

Surviving 6-in gun

The armament overall was essentally the same as on the previous Group I-II Condotierri class. In all, eight 6-in guns or 152/53 mm Ansaldo 1926 in four twin mounts, but now upgraded to the 57 caliber. All four turrets were in superfiring pairs fore and aft. There were solidary twin mounts, with no independent elevation. This caused the issue of a potentially massive barrel interference when firing, so it was slightly delayed between barrels, but still, the second shell in the salvo per turret had its trajectory greatly disturbed by the previous shell own trail.

These Ansaldo guns weighted 7.22 t, with 6.682 m long barrel. The semi-armor piercinf shells that were fired weight 50 kg (AP model 1926), or 47.5 kg (Mod. 1929 AP) and 44.3 kg for the high explosive (HE). Muzzle velocity was 1000 m/s (For the AP 1926 or 950m/s for the HE. Their max range was 24.6 km (HE) or 22.6 km (m1929 AP) at +45° elevation. Useful range was way below that.

Src

Main director APG

Secondary: 6×2 OTO 100mm DP

OTO 100 mm twin mount

A “classic” among classic, this ordnance originated in the Austro-Hungarian 10 cm/50 (3.9″) Skoda 1910 K10 and K11, which examples were obtained after the peace was signed, and Italy obtained war prize cruises, in particular the excellent Admiral Spaun class cruisers and some destroyers. A copy was done with few changes but a loose liner. In 1924, OTO (Livorno) started mass production, with the 100 mm/47 (3.9″) Modello 1924, 1927 and 1928. In 1930 it was adopted by the Soviet Navy, in close cooperation with Italy at the time, with Chervona Ukraina and Krasny Kavkaz being equipped by the 100 mm/50 (3.9″) “Minizini”. They were also used by the Argentine Veinticinco de Mayo class built in Italy and naturally equipped Group I/II light cruisers of the Condotierri class.

The Montecuccoli had three mounts, under shields, aft of the superstrcture, one axial, upper, and two at deck level amidships. They were used for dual fire, and thus used AA modello 1928 shell of 54.23 lbs. (24.6 kg) and the HE modello 1928 of 62.17 lbs. (28.2 kg). Exact bore lenght was 185.0 in (4.700 m). Circa 600 rounds were carried per gun (wartime more). Range was 16,670 yards (15,240 m) at 45° and ceiling 33,000 feet (10,000 m).

Src

AA armament: 37 mm and 13.2 mm

They carried four twin mounts, Breda 37/54 mm modello 1932, not protected, and each weighting 277 kg with a Barrel length of 1,998 mm. HE Shell weighted 830g. This was a Gas-operated-drive reload system capable of 140 rpm at 800m/s and 3,500 m (useful) 6,000 m (theoretical). Fed by 6 vertical cartridges racks with +85° elevation, 60° angle. The barrel jackers were water cooled and possibly later upgraded to the air-cooled modello 1938/1939. Src

They also carried four twin 13.2mm/76 modello 1931 Breda heavy machine gun mounts. In short, they used a 1,532 lbs. (695 kg) mount, with a -11/+85 degrees elevation. At 45° they reached 6,600 yards (6,000 m) with an effective range of 2,200 yards (2,000 m). They were just introduced as the ships were completed. They were replaced by Breda (licence built Swiss Oerlikon) 20 mm/65 guns during WW2.

Torpedo and Mines:

She was completed with a rather weak torpedo armament for the standards of the time, just two twin mounts with 533 mm or 21-in Torpedoes, of the Si 270/533.4 x 7.2 “M” Type (1930) by Napoli’s Silurificio Italiano.

Weight: 3,748 lbs. (1,700 kg)

Overall Length: 23 ft. 7 in. (7.200 m)

Explosive Charge: 595 lbs. (270 kg)

Range/Speed (3 settings):

- 4,400 yards (4,000 m)/46 knots

- 8,750 yards (8,000 m)/35 knots

- 13,100 yards (12,000 m)/29 knots

The type was powered by a Wet-heater and later in WW2 a new model was introduced, a bit faster at 48 knots, 38 knots and 30 knots for the ranges seen above.

Thanks to deck rails running from the forcastle, both cruisers were able to carry 112 to 146 mines (unknown type, src) and did in effect laid several minefields. They also carried two or four paravanes to eliminate mines (2 located on the “B” barbette walls), and had two depht charge launchers installed at the stern with 12 projectiles in reserve.

Onboard aviation:

Both cruisers were provided from the onset with an axial catapult with hydraulic and steam explosive launch system, with enough space around for two to three seaplanes (one on the catapult, two stored close to the funnel). Initially as completed, she carried a single Macchi M.41 fighter and a Cant.25 observation seaplane. Later they were replaced (likely from 1937 onwards according to photos) by two to three Imam Ro.43 biplane observation/spotting general purpose floatplanes. They were removed in 1945. The catapult had a limited traverse, up to 30° from centre line either side of the fore funnel.

Modernizations

Evolution of the Montecuccoli, in 1937, 1938, 1942 and 1944. Click to see further modernizations.

In 1943 Raimondo Montecuccoli received a Gulfo EC.3/ter radar (plus extra AA, eight Oerlikon guns after repairs). The armistice came and by late 1943 she received four twin 13.2mm/76 AA and her battery was competed with ten extra 20mm/70 Oerlikon (18 total). In 1944 apparently her two twin banks were removed, but she received two single extra 20mm/70 Oerlikon and a British type 291 radar was installed on her formast.

By early 1945, both the catapult and seaplanes were removed. Her first postwar refit was perform between 1947 and mid-1949 as a schoolship, as two boilers were removed (remaining output 75,000shp for 29kts) and armament was changed to her “B” superfiring twin main turret 152mm/53 removed, a single twin 100mm/47 AA left, four twin 37mm/54 AA and eight single 20mm/70 AA and four twin 40mm/60 Mk 1 AA guns. She also received a new sturdied foremast to support heavy new radars. Her final displacement was 7,675 tonnes standard and 8,994 tonnes fully loaded for a 5.4m draught.

Monteccucoli class camouflage in 1942.

Raimondo Montecuccoli in June 1940

Sources/Read More

Links

Modernization of the Garibaldi and other Condotierri cruisers in the cold war

On navypedia.org

condottieri-class-cruisers (NE)

www.regiamarina.net

planciacomando

marinai.it: The great cruise of Montecuccoli 1956-57 (pdf)

marina.difesa.it

regiamarinaitaliana.it

lavocedelmarinaio.com

Books

Montecuccoli’s prow underway in 1960

Monografia ridotta nave R.Montecuccoli per aspiranti e allievi dello Stato Maggiore, Livorno, Poligrafico dell’Accademia Navale, 1959.

M. J Whitley, Cruisers of World War Two: An International Encyclopedia, Londra, Arms and armour Press, 1995

Carla Casazza, Montecuccoli 1937-38 Viaggio in estremo Oriente, Bologna, Coop Bacchilega, 2006

Brescia, Maurizio (2012). Mussolini’s Navy: A Reference Guide to the Regina Marina 1930–45. Annapolis, Maryland: NIP.

Chesneau, Roger, ed. (1980). Conway’s All The World’s Fighting Ships 1922–1946. London: Conway Maritime Press.

De Toro, Augusto (December 1996). “Napoli, Santabarbara 1942”. Storia Militare. 39.

Fraccaroli, Aldo (1968). Italian Warships of World War II. Shepperton, UK: Ian Allan.

Whitley, M. J. (1995). Cruisers of World War Two: An International Encyclopedia. NIP

Paolo Alberini, Franco Prosperini, Dizionario biografico Uomini della Marina 1861-1946,

Model Kits

Career

Raimondo Montecuccoli

Raimondo Montecuccoli

Montecuccoli’s prewar career

Raimondo Montecuccoli prewar in Sydney, 1937, for the 150th anniversary of Australia

Raimondo Montecuccoli entered service in 1935. She was assigned to the VII division with her sister ship Attendolo. At the outbreak of the Spanish civil war in 1936, she participated in various missions to protect maritime traffic. In 1937 he was sent to the Far East under the command of Captain Alberto Da Zara to protect Italian interests in the area. Indeed, the Sino-Japanese conflict just broke out and Italian citizens and assets could be at risk. She departed from Naples on 30 August and arrived in Shanghai on 15 September after stops at Port Said, Aden, Colombo and Singapore. Mission acomplished, she sailed south, visiting Sydney and representing Italy at the occasion of 150th anniversary of the founding of the State of New South Wales’s celebrations. She also visited Hobart, Adelaide, Brisbane and Melbourne.

Returning to Shanghai she continued to operate in those waters in defense of Italian interests, visiting also several Japanese ports, like Yokosuka and Kure, and returning to Italy in 1939. Back home in November 1938 she was relieved in Shanghai by Bartolomeo Colleoni. In the period 1935-1940 commanders had been Carlo Alberto Coraggio (from 30 June 1935), Mario Bonetti (from 10 April 1936), Alberto Da Zara (from 11 April 1937), Onorato Brugnoli (from 23 December 1938) and Giovanni Galati (21 December 1939 – 27 April 1940).

Montecuccoli’s wartime career

Montecuccoli in Taranto (wow)

Among her early war missioned from June 1940, here are the most notable:

-She flew IMAM Ro.43 seaplanes with Muzio Attendolo and Duca d’Aosta when taking part in the battle of Punta Stilo on 9 July 1940.

-Together with Eugenio di Savoia and five destroyers, she later fired at Greek positions on the island of Corfu on 18 December 1940.

-In April 1941, Raimondo Montecuccoli laid down an extensive minefield off Cape Bon, along with her sister Muzzio Attendolo and the cruisers Eugenio di Savoia and Duca D’Aosta.

Battle of Sirte

-She was part of the M.42 convoy escort, culminating in the first battle of Sirte on 17 December 1941. She was mobilized by Comando Supremo as the 7 Divisione Incrociatori with Emanuele Filiberto Duca d’Aosta and her sister Muzio Attendolo. Iachino stayed distant as a covering force, opening fire at about 32,000 m (35,000 yd), off range for British Cruisers while Vian laid smoke and moved to the attack, but after a 15 minutes shelling, Italian forces disengaged and headed westward to cover M42. HMS Kipling only was shook by a near-miss either possibly from Gorizia and/or from Andrea Doria and Giulio Cesare and possibly also HMAS Nizam, still by near-misses from Maestrale. As the convoy reached its destination unscaved, her mission was successful without firing a shot.

Battle of Pantelleria

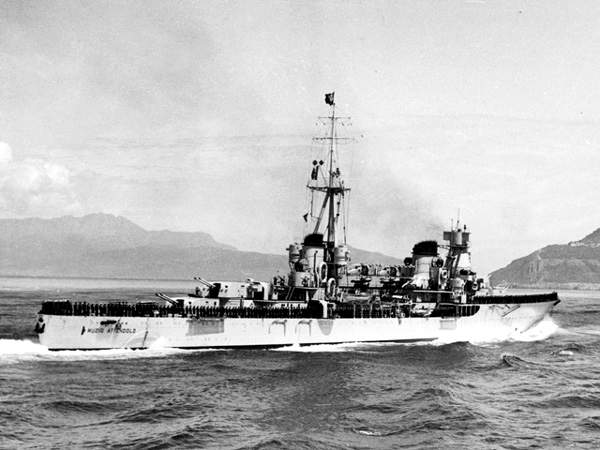

Montecuccoli unwerway in 1942

By she took part in jer most serious engagement on 12-16 June 1942 (operations Harpoon) and the Battle of Pantelleria. Raimondo Montecuccoli and Eugenio Di Savoia, formed the 7th Division which engaged in a long gunnery duel the large Allied convoy to Malta, damaging the cruiser HMS Cairo and destroyer HMS Partridge. They also fired at, and knocked out the towed destroyer HMS Bedouin, later finished off by SM.79 bombers of second lieutenant Martino Aichner (281st Squadron, 132nd Group); During the same convoy attack she set fire to the large tanker Kentucky, and the cargo ship Burdwan, struck already by the Luftwaffe.

According to post-battle reports, Raimondo Montecuccoli also scored a hit on the minesweeper HMS Hebe at “approximatively 26.000 yards”. Fires erupted aboard and she had extensive splinter damage with electrical cabling to sweep mines destroyers, wires, steering gear, echo sounding gear and voice pipes, sounding machine, Commanding Officer’s Cabin were all damaged. As for HMS Bedouin she had been already damaged by a previous air attack, and under tow by HMS Partridge, which was forced to cast off her tow and leave her behind. Only two ships from the convoy reached Malta, one of them holed by a mine.

On 4 August Raimondo Montecuccoli and Eugenio di Savoia sortied to shell without consequences a small Allied convoy off Palermo, during the Allied invasion of Sicily (Operation Husky) and tried to shell the fleet in port. The “Allied convoy” they spotted was the submarine chaser USS SC-530 escorting a freshwater barge. They failed to sink them and withdrew after picking up coastal search radars tracking them with their Metox systems.

Battle of Mid-August (Pedestal)

Two months later, she was mobilized for another Malta convoy interception in 10-15 August 1942 (Operation Pedestal). Called by the Italians Battaglia di Mezzo Agosto, or “Battle of mid-August”, it took place far at sea and could not be attached to a particular location. On 12 August, Kesselring began discussions with Comando Supremo for the co-ordinated Axis attack and reported that the Luftwaffe was to start bomber escort sorties and could not provide air cover for Italian ships, suggested laying extra mines (The Regia Marina already laid a minefield). This absence of air cover limited surface operations and only the light cruiser Muzio Attendolo was sent with two destroyers from Naples to Messina for the operation. Still, Comando Supremo mobilized for it CruDiv 3 (Gorizia, Bolzano and Trieste, 7 destroyers) and CruDiv 7 (Eugenio di Savoia, Raimondo Montecuccoli and Muzio Attendolo, 5 destroyers) plus 18 submarines, 19 MS/MAS boats. But Montecuccoli was only mobilized as “backup”, and did not took part in any engagement.

The Raid on Naples

Muzio Attendolo was theoretically part of the 7th Naval division with Eugenio di Savoia and her sister Raimondo Montecuccoli, reinforcing the main attack force that was the 1st Battle Squadron, with the three Littorio-class battleships. Combined, they could have been very effective in classical naval warfare, but the Battle of Taranto changed their ideal location for more remote positions, and Naples, had become the Italians’ most important naval base. These, were hosted the 7th CruDiv and 1st BS, becoming a priority target for the RAF and USAAF. The city was an important port and strategic location for the RM as were Taranto and La Spezia, and air raids started with French attacks on 10 and 15 June 1940 already. RAF raids started on 1 November 1940, 8 January 1941, 10 July, 9, 11, 18 November and in 1942 were weekly or even daily as part of a strategic campaign led by Vickers Wellington bombers taking off from Africa.

While in Naples on 4 December 1942, the day of Santa Barbara, a raid of 20 USAAF B-24s of 98th and 376th Bombardment Groups taking from British airfields in Egypt arrived over the city, well defended, but unscaved as the local command believed they were a formation of German Ju 52 previously announced, and in addition coming from the direction of the Vesuvio as a trick. It was too late when realizing the mistake as bombs dropped from 6,000 meters just as anti-aircraft defences opened fire at 16.40. A rain of 500 and 1000 lb bombs fell into the port, on the many ships present.

Coming in from the higher Vesuvio, pilots underestimated the time needed to spot, identify, and target the most important targets, making course corrections and between structures and other topographic features, confused the pilots. Bombardiers tried to quickly pick out the more important targets as they approached quickly, and the direction of the air-attack had many B-24 out of position for a bombing run, so they missed the battleships, but they were able to inflex course over the cruisers of the 7th Division.

Some bombs were near-misses, but some also struck the cruisers Montecuccoli, Eugenio di Savoia, and her sister ship, quite badly. Eugenio di Savoia as a result of a near-miss aft had 17 dead and 46 wounded mostly when the rear part of the hull was near-missed, likely by a 1000 ib bomb. An initial examination showed this could be repaired in 40 days. Her twin Muzio Attendolo was also hit in the center by one or two bombs and the damage was quite extensive below the waterline, in fact she listed badly and sank to the bottom, superstructures still emerging. Estimates of recovery and repair were estimated to about a year, but never took place. It was over for her sister ship.

Montecuccoli was next in line and she was struck by a bomb midships, which entered right inside a funnel, disintegrating the area and leaving a crater. The armoured grating protected her vital machinery underneath. If it could have penetrate further ctastrophy could have been total. She had 44 killed and 36 wounded as a result. After the raid, examination took place, showing all the damage where her funnel was, and supporting structures. Her armor however managed to save her and after the initial estimation, it went to seven months of work. The other consequence of the raid was that the 1st BS soon departed for La Spezia, the best defended RM port.

In total the 7th division was crippled, with 188 killed estimated (total number unknown) and 86 wounded. When repairs were done, in the local yard she received four extra 20mm/70 mm Oerlikon machine guns as extra AA defence, before being returned to active duty. She became also one of few Italian naval units fitted with the Italian-designed EC-3 ter Gufo radar. However when recommissioned, this was just weeks before the armistice of August 1943 and she did not sortied prior.

Montecuccoli post-armistice

Montecuccoli in Livorno, 1955 (postcard)

While at that stage Muzio Attendolo was still considered repairable, salvage operationsonly started after the Italian armistice. During the allied occupation she was used as a floating barrack. She could have been converted as an anti-aircraft cruiser to replace Luigi Cadorna, lack of funds and fear of a refusal by the Allied Commission led her to be scrapped instead.

From 8 September, Monteccucoli had been moved in La Spezia, and with two units, Eugenio di Savoia and the Attilio Regolo, recreated the 7th Cruiser Division, added to the 1st BS, battleships Roma, Vittorio Veneto and Italia, plus DesDiv IX, XII (destroyers Mitragliere, Rifiliere, Carabiniere and Velite), DesDiv XIV (Legionario, Oriani, Artigliere and Grecale) and squadron of torpedo boats (Pegaso, Orsa, Orione, Ardimentoso and Impetuoso) from Genoa in addition to CruDiv 8 (Garibaldi, Duca degli Abruzzi, Duca d’Aosta) escorted by the torpedo boat Libra. They set sail to surrender to the Allies for internment in Malta with other vessels coming from Taranto.

Before departing, Duca d’Aosta was reassigned to CruDiv, replacing the small Attilio Regolo, moving to the CruDiv 8 Division. The transfer famously saw the Luftwaffe attacking the Italian fleet underway with “Frit-X” guided, rocket propelled bombs (the first antiship missile attack in some way): Roma, Bergamini’s flagship, sank on 9 September off Asinara coast. When Montecuccoli arrived to surrender and struck her flag, she had carried out 32 war sorties covering 31,590 miles. The “co-belligerence” era saw her participating in numerous missions, mostly as fast transport and for POW repatriation in Italy. She went on in this task without any war mission until the end of the war, with no noticeable event as the Mediterranean became de facto an “allied lake” with only localized coastal operations led by the axis.

Wartime captains has been Captain Franco Zannoni from 28 April to 24 October 1940, Arturo Solari from 25 October 1940 to 20 January 1943, Carlo Unger of Lowemberg from 21 January to 16 May 1943 (interim), Ubaldino Mori Ubaldini from 17 May 1943 to 21 August 1944 and Luigi Cei Martini from 22 August 1944 to the end of the war, in 1945.

Montecuccoli in the cold war

Montecuccoli in 1960 at anchor in Genoa

Ramondo Montecuccoli was one of the four “Condotierri” cruisers left to the Italian Navy following the Peace Treaty: Luigi Cadorna, Duca de Abruzzi and Garibaldi plus Montecuccoli. After a regime change, she joined the newly established Marina Militare, still not part of NATO, and resumed extensive training after a postwar refit, extensive maintenance and some modernization work. from 1947 to 1949 she was converted to serve as a training ship for the Livorno Naval Academy cadets, and carried out summer education campaigns, the first in 1949, from the Mediterranean and beyond; For example she cruised to Santa Cruz de Tenerife in 1951, and London in 1952.

Yet, technology advanced rapidly in many fields and it was felt she needed another refit and modernization, started in the Arsenal of La Spezia from June 1954. The modernization work was aimed at making her more suitable as dedicated training ship and embrace new standards after Italy’s entry into NATO structure, receiving the new pennant C552.

Montecuccoli as a school ship, stern view

Changes consisted in the removal of two boilers to declaim usable space, as well as her nº2 turret, well and ammunition storage, the whole 100mm/47 dual artillery, both turrets, storage and FCS, and her eight now obsolete 20mm/70 Oerlikon machine guns. Instead she was fitted by eight 40/56 “Bofors”, also replacing the 37/54 mm guns. She received a reworked bridge, with extended facilities for C&C and spacious enough for officers and cadets, but also a new mast with surface and aerial detection, aerial detection and fire control radars, plus a new firing center installed lower in the hull. Fuel tanks had an increased capacity of 300 m³ for an extra 615 miles. Her appearance changed in particular on the central area between the forward funnel, new mast and new command bridge.

Alternating fleet exercizes and educational campaigns, she visited Copenhagen in 1955, Montreal, Boston and Philadelphia in 1958, Helsinki in 1961. She also made a famous circumnavigation of the world from 1 September 1956 to 1 March 1957, representing Italy in Australia (as she did in the intwerwa), for Melbourne Olympics, going home by rounding Africa after the crisis in the Suez Canal. Under the command of captain Gino Birindelli, in all she visited 34 ports on four continents and covered 33,170 miles.

Same, 1960.

This however proved to be had last voyage, her hull was now reaching her limits of age and she was disarmed, lowering her flag for the last time in Taranto during a well attended ceremony on the evening of 31 May 1964.

She stayed in reserve however, preserved for long term in case of war and possible reactivation, while her role of training ship was retaken in 1965 by San Giorgio, a former Capitani Romani class vessel. After eight years in reserve, she was sold fro BU, towed for this to La Spezia in 1972.

Some of her remains had been preserved, exposed at Mount Pulito at the entrance to the Città della Domenica and wildlife-recreational park of Perugia in Umbria. There, the public could see her well preserved 152 mm (6 in) twin gun, bridge mast and anchors with a plaque commemorating her 156 missions and 77 800 miles covered.

Muzio Attendolo

Muzio Attendolo

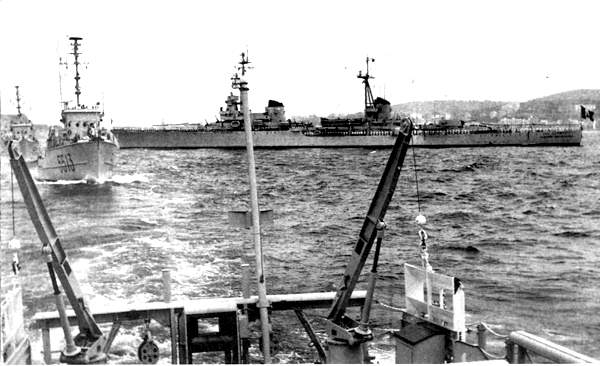

Cruiser Muzio Attendolo underway in 1940

Completed in 1935, Muzio Attendolo served in the Mediterranean, in the same unit as her sister ship, CruDiv VII. From 1936, under command of Captain Manlio Tarantini, she departed for Spain as the civil war broke out, to protect Italian citizens and assets and later for patrolling neutral waters and ensuring officially that no supplies came to either side (in reality the Republicans). Captain Federico Martinengo was in charge from March 1938 to 9 December 1940.

Punta Stilo (9 July 1940)

She was present at the Battle of Punto Stilo (Or battle of Calabria). She was part of the 7th (Light) Cruiser Division, Vice-Admiral Luigi Sansonetti (Division Commander) comprising three light cruisers in addition to Muzio Attendolo, Eugenio di Savoia, Emanuele Filiberto Duca d’Aosta and her sister, Raimondo Montecuccoli. However due to the position of the unit at Punta Stilo, the cruisers were never engaged not fired any shot. Captain Martinengo was relieved by Giorgio Conti from 10 december 1940, until 1st Augusto 1941.

She was present at the Battle of Punto Stilo (Or battle of Calabria). She was part of the 7th (Light) Cruiser Division, Vice-Admiral Luigi Sansonetti (Division Commander) comprising three light cruisers in addition to Muzio Attendolo, Eugenio di Savoia, Emanuele Filiberto Duca d’Aosta and her sister, Raimondo Montecuccoli. However due to the position of the unit at Punta Stilo, the cruisers were never engaged not fired any shot. Captain Martinengo was relieved by Giorgio Conti from 10 december 1940, until 1st Augusto 1941.

Operation Halberd (27 Sept. 1940)

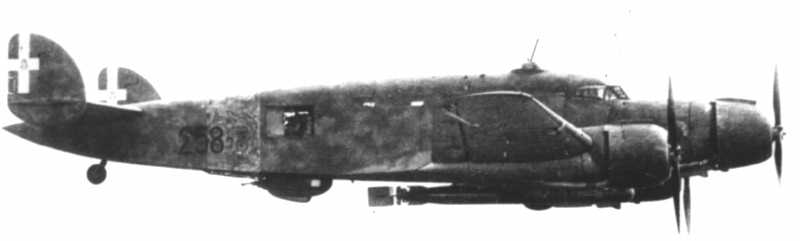

SM.84 carrying torpedoes

Later, she took also part in Operation Halberd unlike her sister ship, a British operation to resupply Malta, in which she took part as a wing of CruDiv VII, composed of the light cruisers Luigi di Savoia Duca degli Abruzzi and herself, under supreme order of Admiral Angelo Iachino. It happened southwest of Calabria, as the Italian fleet tried to intercept a large convoy, well defended, of nine cargo ships, full to the brim with ammunitions and supplies for Malta. The main Battle happened on the 27th, but the light cruisers never were in the right position to be engaged before Iachino withdrew. It was a British tactical victory as the convoy arrived largely unscathed and Admiral Somerville was knighted (a second time) by Cunningham in recognition of his successful command of Force H. Iachino was criticized by his undecision, despite having battleship to throw into the battle. Aviation played a major part with important losses on both sides.

Other engagements: Sirte and Pedestal

At the inconclusive First Battle of Sirte, which came about as a British attempt to intercept the resupply of Benghazi, Attendolo was part of the “Close covering force” covering Convoy M42 while possibly called for an interception. Events ar the same as for her sister ship Montecuccoli, so we will not dive into it. The interception was short-lived and she withdrew to protect the convoy, without firing a shot. In between, Captain Conti had been relieved by Mario Schiavuta from 2 August 1941 until the loss of the cruiser on 4 december 1942.

At Pedestal or the “battle of mid-august”, this was something else. The Regia Marina under Admiral Alberto Da Zara deployed no battleship (after what happened at Tarento, they were based too far away and considered too slow for effective action, and some still in repairs) but still three heavy cruisers (Trieste, Bolzano, and Gorizia, sole survivor of Matapan), three light cruisers (the VII Division including both sister and Eugenio di Savoia), plus 12 destroyers, which could all make a final run at 35 knots, and ambushing forces comprising 23 MAS, 21 submarines and supported by the Regia Marina and Luftwaffe under orders of Kesserling, some 285 bombers, mostly, escorted by 304 fighters so around 600 aircraft. More than some air-sea battles of the Pacific.

Same tactics were used as for Operation Harpoon back June 1942, with joint reconnaissance of Force H, starting on 11-12 August, followed by Axis air attacks from Sicily and Sardinia, and ambush of incoming packs of Italian submarines and German U-boats, plus a barrage comprising Axis torpedo boats and minefields in four successive barriers to disperse the convoy, making it more vulnerable to a fast surface force, and support by 22 torpedo-bombers and 125 dive-bombers (German and Italian Stukas), with fighter escorts, 40 medium bombers, all in a synchronised attack.

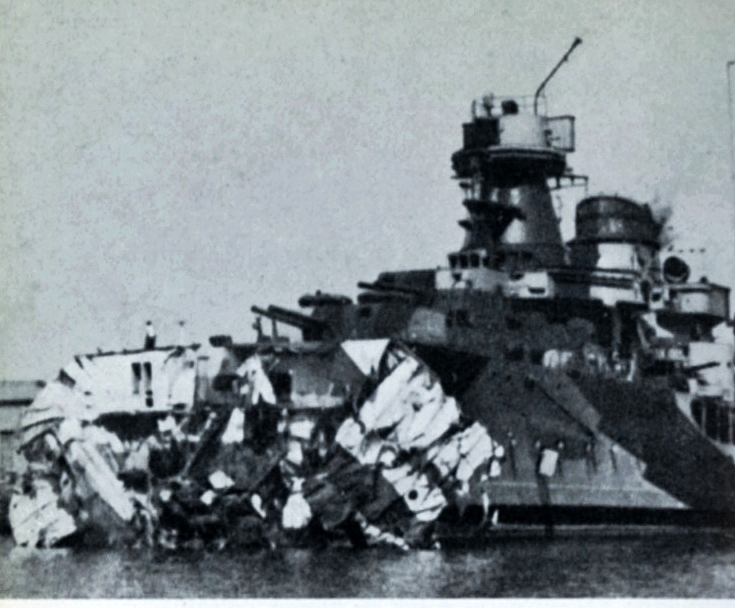

However, the Italian cruiser division being denied air cover by the Germans, it was withdrawn. However the British had submarines in the area of their retreat, the cruisers went through their patrol area and Muzio Attendolo was soon spotted by HMS Unbroken (an U-class submarine) in the early morning of 13 August. A 21-in torpedo struck her bow, which was completely shattered, to the point she was only able to crawl back to safety under good escort. Engineers reinforced the damaged forward bullhead and welded plates to stop flooding so she could accelerate, and escape other potential attacks.

When she arrived at Messina, it was realized by the headquarters of the Autonomous Maritime Military Command as much the damage was extensive. She not only lost her whole forward section up to the bulkhead, which held firm just in front of the “A” barbette, and the transversal bulkhead was what mostly spared her extensive flooding while she did not plunger much due to the inbalance after the loss of the damaged part. It essentially lightened the ship and allowed her to list a bit at the stern, the froward section being slightly more abive water as a result, reducing further any flooding.

Strangely she was not the only one to loss her bow that day as Bolzano was similarly torpedoed by the same HMS Unbroken (note the irony of her name) but amidship, and not repaired due to a lack of resources. They were the only surface losses of the Regia Marina that day (plus two submarines sunk and on damaged). Attendolo was further repaired, and towed from Messina to Naples for prolongated drydock repairs, initially estimated to be done within 3 months. But this proved optimistic.

Muzio Attendolo bow destroyed, general view and close.

Santa Barbara Day Raid

Muzio Attendolo was repaired and part of the 7th Naval division with Eugenio di Savoia and her sister Raimondo Montecuccoli, the “light” arm of the Regia Marina at Naples, bolstered by the 1st Squadron and all three Littorio-class battleships. Quite a powerful deterrent, for which, afetr Operation Torch and ongoing allied convoys, the allies wanted eliminated for good. Airpower was though after, and by On 3 December 1942, a massive bomber force of USAAF Consolidated B-24 Liberator were mobilized in an airfield in Egypt. They took off for a long trip started in the early hourse of 4 December 1942 (St. Barbara’s Day in Italy), with 20 USAAF B-24s of 98th and 376th Bombardment Groups taking off and proceeding armed with 500 and 1000 lb bombs.

As events proceeded the same way as for her sister ship we will go quick about the details. They arrived unnoticed, from Vesuvio, too late to make last minute corrections, bombardiers confused by the clutter of constructions, and missed completely the important battleships, arriving instead above the cruisers and dropping their payload. The heavy bombs were intended for battleships, but they were trusted to go ungodly damage to lightly protected cruisers of the 7th Division.

One bomb nearly missed (but shooked and damaged) Eugenio di Savoia on her aft hull (17 dead, 46 wounded) and then hit Raimondo Montecuccoli midships inside the funnel, blasting her entire superstructure and leaving a crater. Her citadel acted as a “raft”, and she survived, with the armour crown and grating of the funnel acting well too. Raimondo Montecuccoli also deplored 44 killed and 36 wounded as a result. Repairs were stimated short and she would have a long, very long life afterwards.

Muzio Attendolo however, was hit also midship, and by possibly two bombs, between her “X” turret (upper one aft) as her superstructure. This time, the damage went through the citadel and her main power was instantly shot down while flooding started. Not only she had no power but the damage below the waterline due no near-misses caused an extensive flooding, difficult to tame, plus a fierce fire broke aft. The spreading of fire was eventually contained before another air-raid alarm was heard (false alert) at 21:17. By precaution, repair crews were evacuated while other were scrambling for cover.

The second air raid never materialized and the crews returned to their hard work trying to save their ship. Soon, extra repair personnel from the port and and vessels attended Muzio Attendolo over an hour later. The crippled ship meanwhile had her flooding uncheck, to the point she rolled almost 180 degrees, stopped by her superstructures, and settling to the bottom, at her moorings at circa 22:19. The following day the battleships departed to La Spezia and further damage assessments were made.

Attendolo was still considered repairable after this, the staff being informed of a possible 10-12 months worth. However salvage operations did not materialized before the Italian armistice. Once upright and patched, but noit fully repairs still, the cruiser was stripped and used as floating dock during the Allied occupation of Naples. After the war ended, another team examined her structures still in good condition, and it was planned to convert her as a modern AA cruiser, replacing the old Cadorna. However the lack of budget to proceed in the difficult post-war context of Italy had the plan cancelled. There was also the fear of a refusal by the Allied Commission. So she was scrapped instead in place.

Gallery

Raimondo Montecuccoli (world of warships)

Amidships

Forward View

Aft view

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign