The Argentinian Trentos – What made the Veinticinco de Mayo class cruisers famous in particular was that Argentina was the only Nation in the whole southern continent of America to order new cruisers post-Washington (1922). One was ordered in UK, as a fleet cruiser doubled as school cruiser, ARA La Argentina launched in 1937, and in line with the London treaty latest limitations (leading to nearly 10,000 tons cruisers limited to 6-in artillery).

The Veinticinco de Mayo class cruisers were built by OTO on a specific, tailor-made design inspired by the Trentos, like a midget version and specific artillery (190 mm or 7.5 in) also in between a light and an heavy cruiser. They were strangely close to the also Italian-designed Soviet Kirov class cruisers, also using an intermediate caliber, but of of 180 mm (7-in) and with the same configuration of thee triple turrets. The initial plan called for three, but the third was later cancelled due to budget cuts, and re-ordered in UK as La Argentina. Their operational life was quiet due to Argentina’s neutrality, but long, as they were discarded in 1960, after nearly 30 years of good and faithful service.

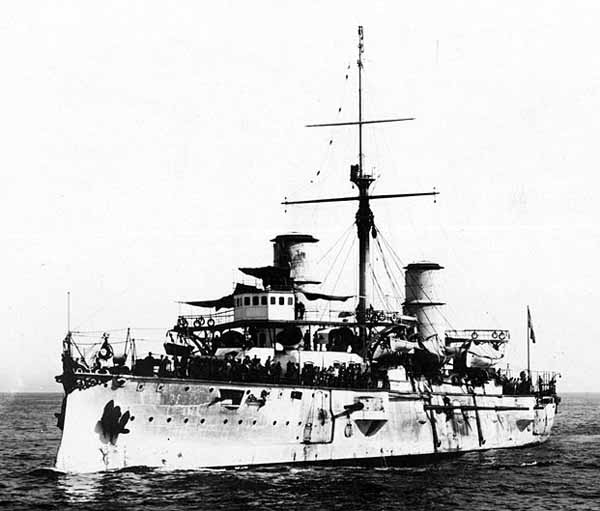

Argentinian cruiser ARA Pueyrredon, which needed to be replaced.

Context

Argentina’s economy and ambition in the mid-1920s found an exutory with a ten-year shipbuilding program which was approved in 1926. It was aimed at giving back an edge to Argentina facing its arch-rivals, Brazil and Chile. The plan called for modernizing Argentinian cruisers, with the last being also the best, Garibald-class vessels which for their time were top-notch, but in 1925 were completely obsolete. Cruisers would also complete support for the Rivadavia class dreadnoughts, just modernized. The program was backed by 75 million, and called for the construction of three cruisers. There was an international tender.

During the early 1900s Argentina was a very prosperous country, ranked among the world’s ten largest economic powers for GDP. So funding was available for all armed branches. In 1926 a large program was adopted to renew the fleet. It was worth 75 million pesos (gold) over ten years. This was enough to provide three new cruisers. Argentina announces therefore that year the opening of an international competition for the three cruisers, a juicy contract for all yards of the time. Traditional suppliers such as the United Kingdom but also the United States (which won in 1910 for the Rivadvia class BBs).

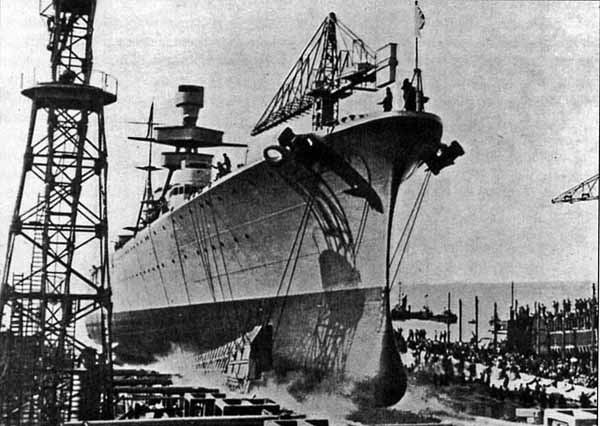

Launch of ARA Almirante Brown

There was also a favourable bias to Italy due to the general satisfaction with the Garibaldi class cruisers in the past. Italian yards still had a favourable reputation and were reputed the cheapest. Therefore it was half a surprise when the Italian company Odero-Terni-Orlando (OTO Melara SpA later) was chosen. Signature of the official contract was made in London on May 5, 1927, where the contract was first emitted.

The two signatories were Admiral Ismael Galindas, representative of Argentina, and Luigi Orlando, president of OTO. The initial order comprised two cruisers, with a total value of £ 2,450,000, to be precise, £ 1,123,000 (ARA Almirante Brown) and £ 1,225,000 (ARA Veinticinco de Mayo). Argentina made a reservation for a third cruiser, postponed the country’s financial situation fell recently and waiting for it to improve. Ultimately, Argentina would chose a more specialised design, and a British one, called C-3 La Argentina.

OTO’s contract for the Veinticinco de Mayo class

The contract awarded to the Italian firm Odero-Terni-Orlando (OTO) was because the proposal was both the most affordable and appealing in engineering ways, as it was based on the Trento class heavy cruisers, just made for the Regia Marina and considered with envy for their size and performances.

In short, the Argentinian Armada in 1926 needed two modern cruisers to replace its oldest cruisers, older than rival Brazil’s Bahia class (less well armed but faster than the Garibaldi class) and Chile’s Chacabuco. The Garibaldi possessed 254, 200 and 150 mm guns, so the new vessels needed to be as powerful as possible.

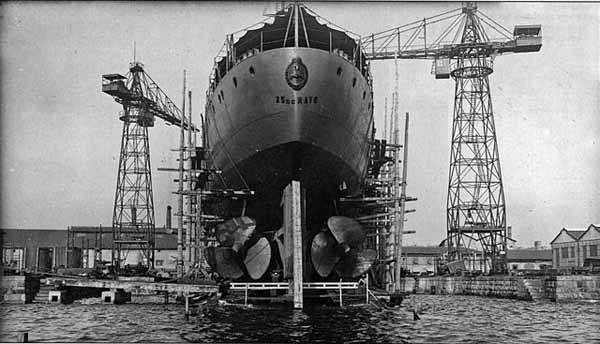

25 de Mayo in drydock, poop view

The gauntlet was took up by OTO engineers to design the Veinticinco de Mayo class cruisers on a basis they prepared -The Trento- and they became compromised masterpieces.

However due to a limited budget, OTO’s design was a puzzle of engineering, trying to cram the heaviest armament possible on the smallest displacement, and keeping as many features as possible from the Trento’s to save time. This was also a semi-risky proposition as the Trentos were Italy’s first post-ww1 design for a heavy cruiser, still untested, and they will have their lot of teething problems, related to their tripod mast and hull’s strength, not speaking of the very light protection.

The design evolved through many iterations with modifications regarding dimensions, armament, protection and the power-plant, under the watchful eyes of the Argentinian commission.

Design of the Veinticinco de Mayo class cruisers

Veinticinco de Mayo’s hull was eventually limited to 162.5 meters long, 170.8 meters overall and 17.8 meters in beam (so 1/10 ratio like the Trento), and 4.66 meters draft when fully loaded. Standard displacement was 6,800 tons, up to 9,000 tons fully loaded. This was 3,000 tonnes less than the Trento, and armament was reduced, but also the most interesting part (see later). Externally, the ships recalled the Trentos, but were also quite different. Outside the artillery, smaller and in three turrets rather than four, they had not a flush-deck hull, which was lower aft with a traditional cut, a tripod with the axial main leg supporting the main fire directors placed just aft of the bridge.

The latter was a small 2-storey structure with no open deck on its roof but an embedded conning tower which supported the first main fire director. Deck superstructures were reduced and narrow. In between the main bridge and tripod, there was the boats deck and behind the main mast and its boom crane, also tripod. The aft superstructure was small and supported the aft director for secondary armament.

The general architecture of the Veinticinco de Mayo class cruisers was characterized by its conciseness. The large unique truncated funnel was completed by a steel arch superstructure, made up of three levels: Navigation bridge, chart room and kiosk. The suspension bridge was closed with a sloping roof and glazing, and the control room was armored, at the top of the command tower.

The aft superstructure superimposed on the deck deck included several devices for fire fighting. Kitchens, bathrooms and laundries were all located in this area and the superstrutures above, which were narrow. The tripods did not posed any vibration issues, and apart the two main range finders, searchlights and signaling equipment were placed in support gondolas. The after main mast duty was its boom crane to manage boats.

Propulsion of the Veinticinco de Mayo class

The first interesting point was that the engines and boilers had the particularity of being located on the upper deck. Exhausts were truncated into a single funnel, located right after the tripod mast.

For propulsion, as top speed was to be above 33 knots if possible, two proven British-built Parsons steam turbines were adopted, fed by six equally proven oil-firing Yarrow boilers (working pressure 21 atm) rated for a grand total of 85,000 hp (63,000 kW). This power was transmitted to two unusually large bronze propellers, 4,06 m each in diameter. On trials, top speed averaged 32 knots (59 km/h) in normal conditions, a feat compared to the relatively small powerplant, and both cruisers reached 33.5 knots during sea trials, therefore filling the contract specs. OTO engineers also stacked oil tanks able to carry 2,300 tons in wartime, 1800 in peacetime, enough to provide 8,030 nautical miles (15,000 km) of autonomy at 14 knots (26 km/h). Some sources diverge on that number, between 7 300 and 12 000 nm. In normal conditions, oil was stored in double bottom and double hull side tanks, providing an ASW buffer.

Armour

Armour was within the standard for light rather than heavy cruisers. A 70 mm (2.8 in) armoured belt was fitted from the first to the last main turret. 60 mm (2.4 in) was used for the command turret. 50 mm (2.0 in) was used for turrets and barbettes. Only 25 mm (0.98 in) was provided for the armoured deck and above aft machinery.

Armament of the Veinticinco de Mayo class

Main artillery

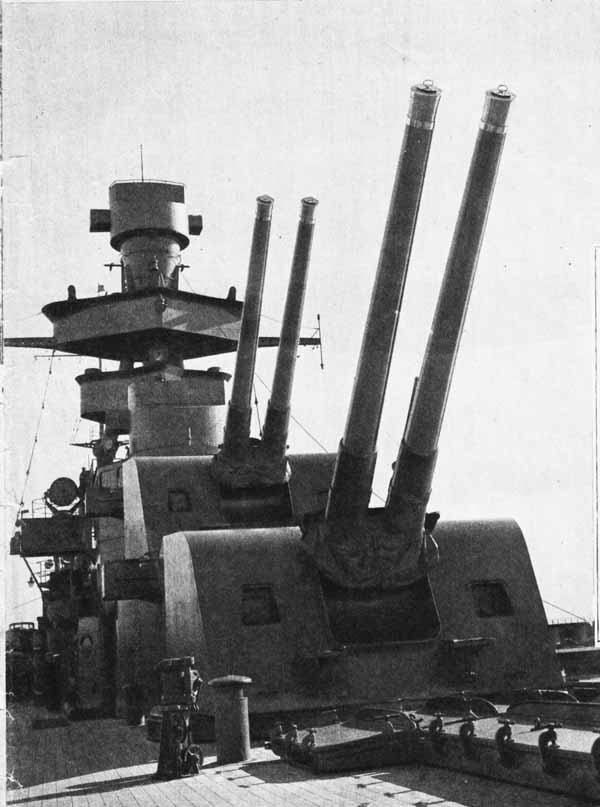

The main 190 mm (7.5 inch) guns were designed especially for this class for greater stability (the Trento class carried 203 mm (8 inch) guns). This could have been a quite powerful gun, but no documents about its characteristics are available in Italian or Argentinian archives.

These guns were supported by a common cradle to simplify construction. Therefore they could not elevate separately, and close trajectories when firing in concert was a problem for dispersion.

These guns could fire a 90 kg (200 lb) shell up to 23 kilometres (25,000 yd). Although was not as large as the 203 mm guns of the Trento, they were quite sizeable for the lighter Argentinian cruisers, after the initial design calculations it was decided to sacrifice the aft superfiring turret to save weight and hull stress, to just three turrets. That was still a volley of six heavy shells, from a 6,000 tons ship. The end result was equivalent to the British York class (York and Exeter).

Secondary Artillery

The secondary armament was standard, consisting of twelve 102 mm (4 inch)/45 Dual Purpose guns, in six twin mounts. They fired a 13.5 kg (30 lb) shell. They were placed along the broadside and protected by masks at first, but in order to save more weight, these gun shields were removed. Due to their low height above water, heavy weather affected them considerably, and left their crews without protection against strafing attacks.

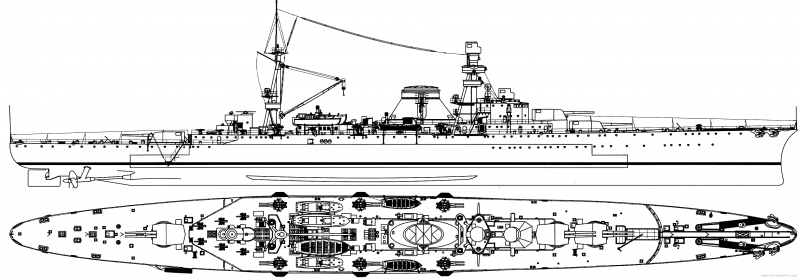

Blueprint of ARA Almirante Brown

AA Artillery

Light AA artillery comprised the same array of the Trento, six Vickers-Terni 40/39 mm guns in single mounts, aft of the superstructure. These were among the first auto-cannons, firing 100-130 rounds per minute. However reliability was lame. The single mounts limited problems but were bad for fire concentration. The Royal Navy’s own mounts were usually quadruple or octuple (“Pom-Pom”). The main issue on the design, because of the higher center of gravity, was reduced superstructures which did not allowed to install AA higher up. The main DP guns on the deck and the 40 mm above the aft superimposed superstructures were too low to not see interferences in heavy weather, which was common in the south Atlantic, in particular on the coast of Patagonia and down to the Falklands.

Torpedo tubes

They were in fixed mounts amidships, in two groups of three firing abeam, unlike the Trento which had two twin groups. They were located aft of the funnel, in beween this and the aft tripod mainmast, abaft the boats deck. This was an obsolete solution, not repeated later as the tubes could not be aimed.

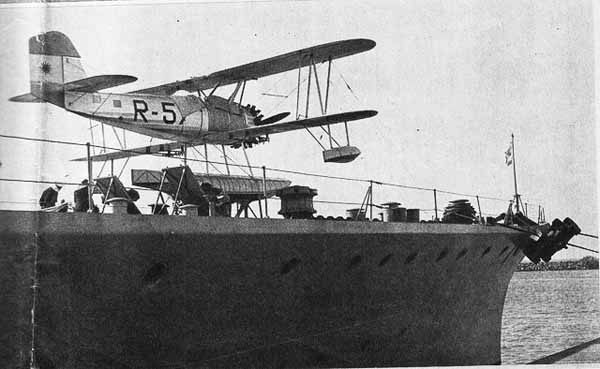

Aviation:

A catapult launcher for seaplanes was placed over the fore deck, also an Italian practice. Sources are widely diverging on these, Grumman seaplanes in WW2, Supermarine Walrus after the war, or Boeing biplane in the 1930s.

Active life

Post-war refit of the Veinticinco de Mayo class cruisers

The ships received a drydock refit in 1944 to improve their stability, further reducing top weight. The twin DP 102 mm gun battery was replaced with six Bofors 40 mm guns, one for each twin mount but four four more Bofors also replaced the former six single old Vickers-Terni liquid-cooled AA guns aft. Crucially, after the war, US Mk.53 radar directors were installed to better serve AA fire. Stability was gained indeed on paper, but this was offset by the addition of a radar. On the same move, the forward deck aircraft catapult was moved from amidships.

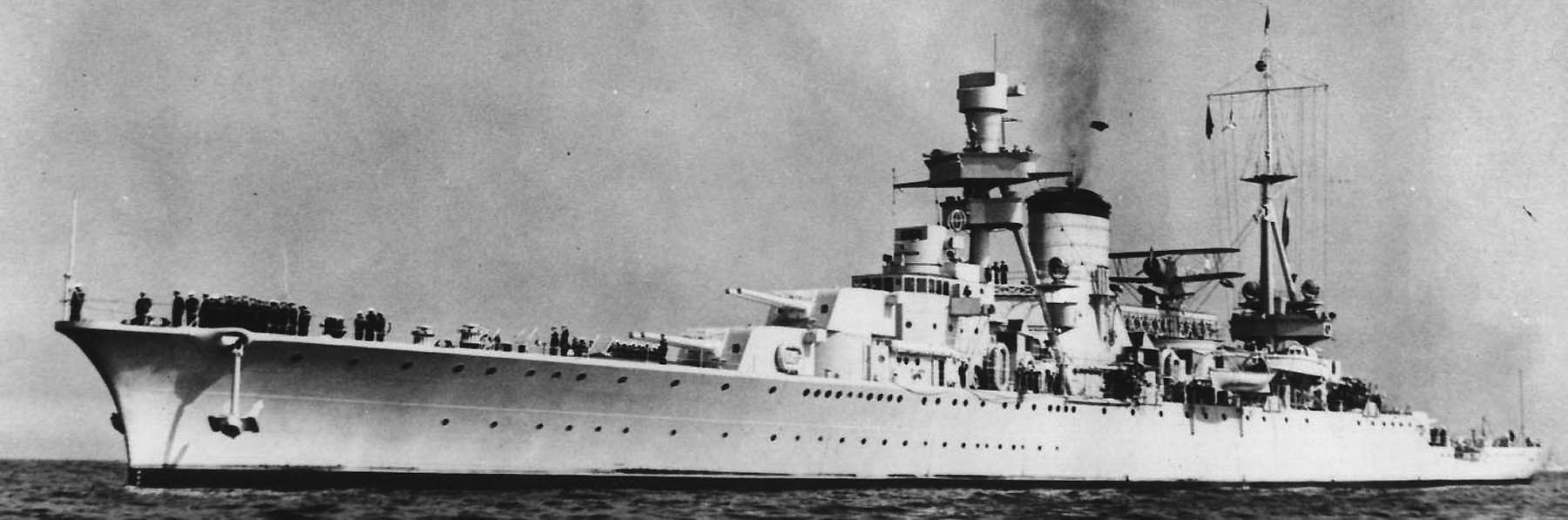

ARA V. de Mayo

ARA Veinticinco de Mayo (C-2), was named after the Argentine National Day, independence declaration towards Spain after the May revolution of 1810. The cruiser’s motto was “We swear to die with glory” (“Juremos con Gloria Morir“, in Spanish). The cruiser was built in La Foce, part of La Spezia, under supervision of the company OTO Melara SpA. When completed, the Yard waited for the venue of officials from Argentine in Italy, and both the 25 of May and Almirante Brown flown the Argentine flag on the first time during a ceremony in July 5, 1931. Both departed for the motherland on July 27, 1931. They arrived on September 15, 1931.

In June 1935, 25 de Mayo carried politician José Carlos de Macedo Soares to Rio de Janeiro in Brazil for a conference. During the Spanish War she was dispatched from Puerto Belgrano on August 8, 1936, to reach the Iberian Peninsula, arriving on August 22, 1936 in Alicante, a republican-held city. Her mission was to protect and recover Argentinian citizens here, and assets threatened by the war. She would carry out patrols along the coast. Her crew also provided humanitarian aid to both the Argentine locals and Spaniards.

At the end of October 1936, she was attacked by the nationalist aviation and opened fire to protect the nearby Soviet cargo ship Kursk which transported hardware precious for the Republicans Army, notably Polikarpov I-16 fighter planes and aerial bombs. This attack and counter fire breached her neutrality stance but was later considered an act of self-defense, as the Nationalist aviation was not distinguishing between targets and the cruiser took near-misses. She returned to Argentina on December 14, 1936.

From February to January 1937, she teamed with ARA Almirante Brown for a grand tour of the Pacific, stopping at Valparaiso and Callao en route. 25 de Mayo would also made an official visit to Rio de Janeiro, bring back home the Argentine President Agustín Pedro Justo. In early 1938, she was anchored in Montevideo, and returned again in 1940. During WW2, due to the country neutrality, she only took part in regular fleet exercises and training sessions, to be ready in case, but without firing a shot in anger.

Author’s profile of the Veinticinco de Mayo class

From February 1944, the Argentinian cruiser was sent in dry dock and had its hull overhauled. She emerged in 1945 to participate in several speed tests, reach 32 knots. By May 1945, Germany surrendered and the cruiser took part in a search for 23 U-Boats still signalled in the South Atlantic, but in vain. In 1947-1948, Veinticinco de Mayo was sent to Antarctica with ARA Almirante Brown, but this exercise was not officially related to operation Highjump, a controversial naval cover to establish the Base Little America IV. Both cruisers were also sent for peacekeeping tasks.

Purchase of band new American and British cruisers by the Argentine Navy made the Veinticinco de Mayo cruisers superfluitous. They still participated in several fleet exercises, but the 25 de Mayo was decommissioned in 1954 and the crew transferred on the still active ARA Almirante Brown. In 1959, 25 de Mayo was placed in the reserve, stricken from the lists on July 31, 1960. She was then put on sale, and purchased on March 2, 1962, but an Italian shipbroker, which towed her to Italy for her scrapping.

ARA Almirante Brown

ARA Almirante Brown, offical photo

Soon before commissioned on July 11, 1931, Almirante Brown reached its contracted speed of 32 knots (59 km/h). Her short truncated funnel was raised to allow less interference from the smoke.

ARA Almirante Brown (C-1), happened to be launched first (August 11, 1929), despite the class bear the name of her sister ship. She was named after the Irish-born admiral Guillermo Brown (1777-1857) largely considered to be the father of the Argentine Navy. She was the third Argentine warship to bear this name.

She arrived on September 15, 1931 in Argentina, officially part of the fleet. Both cruisers would participate to all fleet training exercises, notably showing the flag and parading off the coast of Buenos Aires. From February to January 1937, ARA Almirante Brown toured the Pacific, stopping at Valparaíso and Callao. She carried the President Agustín Pedro Justo back from an official visit to Rio de Janeiro.

In February 1938, she took part in a ceremonial parade to honour his successor, Roberto Marcelino Ortiz. In November-December, she departed Lima with the Minister of Foreign Affairs Jose Cantu. In August 1939, she departed Montevideo (Uruguay) to carry back to Argentina the Uruguayan President Alfredo Baldomir. In October 3, 1941, she was in manoeuvers off Tierra del Fuego, when colliding with the destroyer ARA Corrientes. Both were badly damaged, a tragic event in the Argentine Navy which also ended with an enquiry and court martial commission. The unlucky cruiser was repaired for three months in Puerto Belgrano (Coronel Rosales). By October 1942, Admiral Brown took part in the honorary division heading to Chile to participate in the celebration of the centenary Bernardo O’Higgins death, pretty much considered the father of the Chilean navy.

In late 1943, after a round of “neutrality patrols” Almirante Brown untered the drydock for a one-year overhaul. She was back in the fleet in early 1944. Modifications included the fitting of a catapult, included in the original design. The catapult and crane were placed on the centreline between the funnel and mainmast, operating two Grumman floatplanes. Photos shows however a Supermarine Walrus.

The six old twin 102-mm mounts were retired and replaced by twin 40-mm Bofors guns. About one year after, in March 27, 1945, Argentina declared war on Germany and Japan and the cruiser, like her sister ship, started to search for U-Boats in the area, which could have have remained hidden after the capitulation and not informed of it.

In 1946, Almirante Brown made an official visit to Valparaíso in Chile. She participated in an official parade for the election of Juan Perón as President of Argentina on June, 4. In 1947-1948, she teamed with Veinticinco de Mayo for fleet exercises off the coast of Antarctica. In 1949, she departed to visit New York, stopping on her return trip to Trinidad. On April 20, 1950, she was used for a landing test for a Bell Helicopter, the first of its kind on an Argentine warship.

ARA Almirante Brown in the Antartica

In 1951, two Brooklyn-class cruisers were purchased and ARA Almirante Brown was transferred to the Second Cruiser Division. From 1952, she was placed in reserve at Puerto Belgrano carrying a reduced reserve crew for basic maintenance. She however would depart for Buenos Aires during the coup of September 16, 1955 seeing the overthrow of Juan Perón. In 1959, she returned to the reserve. She was eventually discarded and written off the Argentine fleet on July 31, 1960 and decommissioned on June 27, 1961. Placed on the sales list for scrap metal, she was purchased at auction to the same Italian company which acquired her sister-ship. Both were towed to Italy and BU from March 2, 1962.

ARA Almirante Brown in 1949 – HD

Read More:

Conway’s all the worlds fighting ships 1922-47

M.J. Whitley, Cruisers of World War Two, 1995, Arms and Armour Press

//en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Veinticinco_de_Mayo-class_cruiser

//www.histarmar.com.ar/Armada%20Argentina/Buques1900a1970/CrAlmBrown1931.htm

//www.lasegundaguerra.com/viewtopic.php?t=11133

//www.navypedia.org/ships/argentina/arg_cr_25_de_mayo.htm

//www.argentina.gob.ar/armada

//www.histarmar.com.ar/Armada%20Argentina/HistoriaCrucerosArgentinos.htm

//navypedia.org/ships/argentina/arg_cr_la_argentina.htm

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign