Cavour’s sister class: Doria

The Andrea Doria class (or Caio Duilio class for Italians sources) was the last dreadnought battleship class of the Regia Marina to see service in WW1, started in 1912 and completed 1916. The Andrea Doria and Caio Duilio were an incremental improvement over the Conte di Cavour class, with a main battery of thirteen 12-in guns (305 mm) guns, as most countries that went into that race late, whereas the British already swapped on the 14-in caliber.

Both battleships were stationed in southern Italy to ensure the Austro-Hungarian Navy stayed trapped in the Adriatic, and they saw no action but drills, as local deterrent. After the war, they were involved in the Corfu incident in 1923, joined the reserve in 1933, and completely rebuilt from 1937 until 1940, seen them thrown in WW2. Stationed in Taranto they were caught by the famous British carrier strike in November, which placed RN Caio Duilio out of action until May 1941. Escorting convoys to North Africa saw ultimately Andrea Doria damaged, until fuel shortages brought their activity from 1942 and until the surrender to a standstill. They ended interned in Malta, and retired, discarded and BU in the 1950s. Their unimpressive active service lasted for 20 years.

Design of the Doria class

Both Andrea Doria-class battleships were designed by naval architect and Vice Admiral Generale del Genio navale Giuseppe Valsecchi. They were planned and ordered in response to the French Bretagne-class. The latter were better armed, with ten 340mm guns, but the Italians trie to compensate by having the admidship triple turret giving them thirteen guns (three more).

The design proceeded from the generally successful Conte di Cavour-class and only encurred some minor changes. The superstructure was reduced, which was obtained by shortening the forecastle deck and lowering the amidships gun turret for better stability and arc of fire. This also concerned a much more powerful, standard secondary armament, now sixteen 6-in guns (152mm) rather than the light 4.7 in (120 mm) guns of the Cavour.

Their hull was about the same, 168.9 meters (554 ft 2 in) long at the waterline, 176 meters overall, like the previous class for the same beam of 28 meters (91 ft 10 in) and slightly greater draft of 9.4 meters (30 ft 10 in) versus 9.3 in. Displacement was a tad lighter at 22,956 long tons (23,324 t) normal up to 24,729 long tons (25,126 t) deeply loaded versus 25,086 long tons (25,489 t) deeply loaded for the Cavour, mostly the result of the forecastle shortened. ASW protection and compartimentation was about the same, with a complete double bottom and a subdivision into 23 longitudinal and transverse bulkheads. They had the same pair of rudders on the centerline and the crew was 31 officers and 969 sailors.

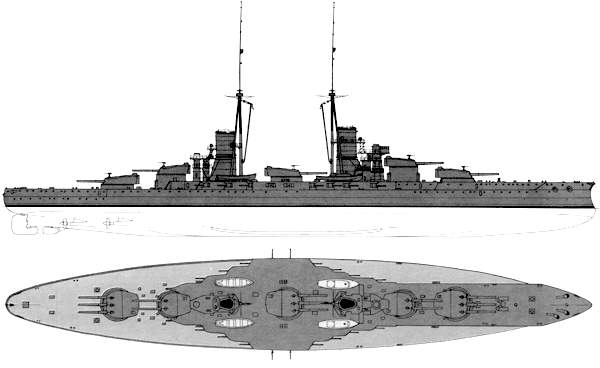

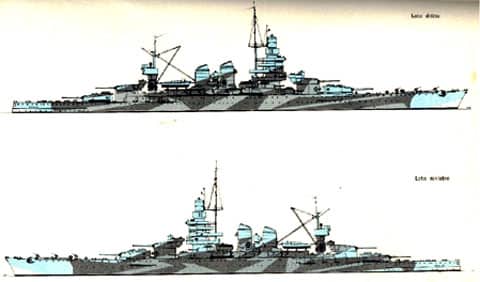

Comparison between the two classes, with Cavour (top).

The most striking difference outside the forecastle, was the placement of the tripod mast, behind the funnel, and the funnels themselves, raised a few meters to lower smoke interference.

Propulsion

Both battleships had a very different powerplant than the the Cavour: Three Parsons steam turbine arranged in three engine rooms, instead of four mated on four shafts. The center engine room housed a single turbine that drove the two inner propeller shafts. Both side engines rooms comprised a turbine set, driving each an outer shaft. Steam was provided by 20 water-tube Yarrow boilers (as in the previous class), with the same mixed arrangement: 8 burned oil and the remainder 12 burned coal, but sprayed with oil. Their design speed was 22 knots (41 km/h; 25 mph) based on a nominal output as designed of 32,000 shaft horsepower (24,000 kW) (compared to 30,700–32,800 shp (22,900–24,500 kW) on the Cavour). But both battleships failed in trials to reach these figures. They achieved 21-21.3 knots (38.9 to 39.4 km/h; 24.2 to 24.5 mph) only on trials. Both carried in peacetime a total of 1,488 long tons (1,512 t) of coal, completed by 886 long tons (900 t) of fuel oil. On paper, their range was 4,800 nautical miles (8,900 km; 5,500 mi) at the cruising speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph), the same as the Cavour.

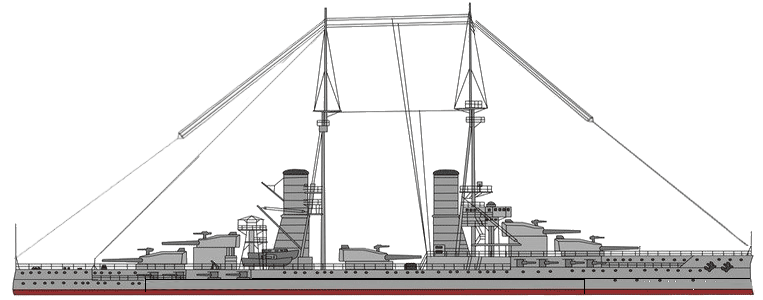

Battleship scheme in 1913 (modified)

Armament

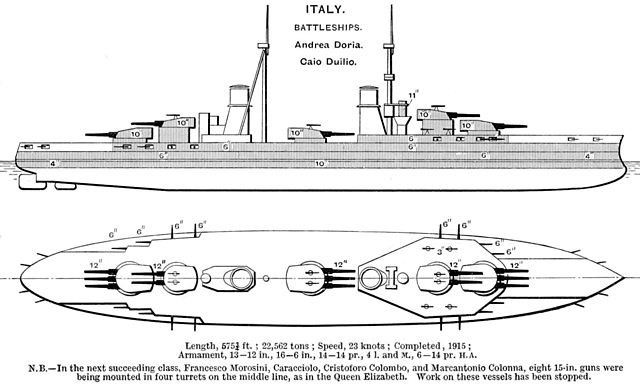

As built, both battleship had the very same main guns and arrangement as the Cavour: Thirteen 46-caliber 12-inches or 305 mm guns provided by Armstrong Whitworth, Vickers. They were placed in five gun turrets, all centerline, two twin turrets superfiring forward and aft, and three triple at deck level as they were heavier, including one amidship which took space and obliged to design reduced superstructure to free the arc of fire. They were designated ‘A’, ‘B’, ‘Q’, ‘X’, and ‘Y’ and had an elevation of −5 to +20 degrees. They were provided each with 88 rounds, 452 kg (996 lb) AP types. For guns’ performances naval historian Giorgio Giorgerini affirmed the rate was one round per minute at a muzzle velocity of 840 m/s (2,800 ft/s). Their maximal range was 24,000 meters (26,000 yards).

The secondary armament comprised sixteen 45-cal. 6-inches guns (152 mm) designed by Armstrong Whitworth, all in side casemates. As they were low, they had the same problems as USN battleships secondary battery at the time: They were wet in heavy weather. The rear guns were so obscured by water spray, gunners had to wait in between water splashes to fire; Depression was −5 degrees and maximal elevation +20 degrees. Rate of fire was six rpm, firing a 47 kg (104 lb) HE shell at a muzzle velocity of 830 mps (2,700 ft/s) to 16,000 meters (17,000 yd). 3,440 rounds were carried in all.

The light, tertiary artillery intended to deal with torpedo boats comprised nineteen Vickers 76 mm/50 (3.0 in) guns, in 39 different locations. Notably the turret roofs, and upper decks. Elevation was about the same as the secondary guns but with 10 rpm. They fired a 6 kgs (13 lb) AP shell at 815 mps (2,670 ft/s), up to 9,100 meters (10,000 yd). As customary for the time, the Doria were provided with three underwater torpedo tubes, 45 cm (17.7 in) on the broadside, and one in the stern.

Brassey’s diagram of the class as published in 1923.

Protection

It was again, close to the Cavour class, with only slighlyt different arrangement due to the shorter forecastle. They had a complete waterline armor belt, 250 mm (9.8 in) thick, tapered down to 130 mm (5.1 in) up to the stern, and down to 80 mm (3.1 in) up to the bow, after the barbettes positions. Above it was a strake of 220 mm (8.7 in) thick, up to the lower edge of the main deck to create a sloped box. Over it was another, 130 mm thick stray protecting the casemates. Two armored decks constituted the vertical protection, a 24 mm (0.94 in) main deck in two layers, with 40 mm (1.6 in) slopes down to the main belt and an upper deck 29 mm (1.1 in) in two layers. Transverse bulkheads closing the “box” by connecting the belt and decks were about 90 mm. The turrets faces were protected by 280 mm (11.0 in) of sloped amor, with 240 mm (9.4 in) sides, 85 mm (3.3 in) back plate and roof. They seated on 230 mm (9.1 in) thick barbettes above the deck, down to 180 mm (7.1 in) below, and 130 mm below the upper armored deck. The walls of the forward conning tower were 320 mm (12.6 in) thick, and aft 160 mm (6.3 in). This was better forward than on the Cavour, 280 and 180 mm (11.0–7.1 in) respectively. It should be noted that if the turrets seems lightly protected, the slopes accounted for an artificial thickness in fact greater, 280 mm being equivalent to 310 mm in direct fire.

Author’s illustration of the Doria class as built.

Doria specifications 1916 |

|

| Dimensions | 176 x 28 x 9.3m |

| Displacement | 23,000 tonnes, 25,000 tonnes FL |

| Crew | 31+969 |

| Propulsion | 4 screws, 3 GS turbines, 20 Yarrow boilers, 30,000 hp |

| Speed | 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph) |

| Range | 4,800 nmi (8,900 km) |

| Armament | 13x 305mm (2×2, 3×3), 16 x152mm, 19 x76mm, 3x 17.7 in TTs sub. |

| Armor | Decks 98 mm, barbettes 130mm, turrets 280mm, belt 250mm, CT 320mm fwd. |

The Doria class during WW1

Both battleships were completed as Italy already was at war, with the triple Entente (France, UK, Russia) but they saw little to now action during that time: Italy’s main opponent was the Austro-Hungarian Navy, which stayed in Pola to avoid a decisive battle that would probably ended badly, and her battlefleet stayed inactive too, for the duration of the war. Admiral Paolo Thaon di Revel, naval chief of staff feared indeed Austro-Hungarian submarines and minelayers, at ease wit the Adriatic shallow seas, and this threat was too much to risk his precious capital ships. He preferred to create a blockading deterrent force at the southern end of the Adriatic. Smaller ships, TBs, gunboats and MAS torpedo boats instead used to raid the Austro-Hungarian coast, posing a threat to their ships in turn. Revel’s battleships spent their time idle with a few sorties for training, at close range and with a safety net of patrolling TBs and destroyers, or trained in port. From the time Andrea Doria and Caio Duilio entered service, on 13 March 1916 and 10 May 1915 respectively, until November 1918, sailors lived a dull service while Officers could at least enjoyed the nearby city pleasures and mondainities.

Andrea Doria in 1927

The interwar

Andrea Doria and Caio Duilio both cruised in the eastern Mediterranean after 1918, seeing first hand, and intervening in postwar disputes. Caio Duilio was sent to quell a Greek-Turkish dispute over the control of İzmir in April 1919, while Andrea Doria suppressed Gabriele D’Annunzio’s seizure of Fiume, in November 1920. She also replaced her sister ship in the Black Sea after the İzmir case, relieved later by Giulio Cesare. Andrea Doria and Caio Duilio also participated in the Corfu incident in 1923. By January 1925, RN Andrea Doria started a goodwill tour, passing Gibraltar, and stopping at Lisbon in Portugal, to represent Italy for the 400th anniversary and celebration of Vasco da Gama. Outside a routine of peacetime service and cruisesto other ports in the 1920s, they were eventually placed in reserve in 1933, amidst crushing economocal difficulties resulting of the 1929 financial crisis.

-1918: They received two 76 mm/50 on AA mounts, their first anti-aircraft armament. One was placed forwards, at the bow and the other on top of ‘X’ turret.

-1925: Some of the 76 mm/50 Vickers guns was down to 13, those of turret tops, whereas six new 76 mm/40 guns were installed abreast the aft funnel as well as 2-pounder AA guns.

-1926: Upgraded rangefinders (reinforced forward tripod and larger main rangefinder) and fixed aircraft catapult, port side with a Macchi M.18.

Both battleships after 1933 were thought to be modernized, as were the Cavour class. This was scheduled eventually after the first ones, in 1939. They went into drydock and this reconstruction lasted until October and April 1940 respectively, so they emerged, again, in wartime.

Late interwar reconstruction

Before even talks of modernization, it was recoignized the Littorio-class battleships would not be ready in time to replace the Cavour and Doria class, and as a stop-gap measure to answer the newly built French Dunkerque-class battleships announced in 1931, in 1933 it was decided to modernize (and later rebuilt completely) the two Cavour, and the two Dorias followed three years after, in 1937. The changes were considerable and to simply this, let’s make a list:

Hull and superstructure:

-Brand new bow section after the old one was was dismantled. Longer by 10.91 meters (35 ft 10 in), a more radical approach than on the Cavour-class where a new bow was grafted over the old one. -Inncreased beam at 28.03 meters (92 ft 0 in) with Pugliese ASW longitudinal protection

-Increased draft at 10.3 meters (33 ft 10 in) DP.

-Increased displacement to 28,882 long tons/29,391 long tons respectively.

-Crew increased to 70 officers, 1,450 enlisted men.

-Brand new upper hull, with the forecastle extending to the aft barbettes.

-Completely new silhouette, dictated by the new narrow truncated funnels, new tower bridge, new deck superstructure, and rear tripod mast and aft CT.

Powerplant:

-Only two propeller shafts

-New Belluzzo geared steam turbines for 75,000 shp (56,000 kW).

-Height superheated Yarrow boilers.

-Top speed 26.9–27 knots (49.8–50.0 km/h; 31.0–31.1 mph) on trials, 26 knots (48 km/h; 30 mph) as designed.

-2,530 long tons (2,570 t) of fuel oil

-4,000 nautical miles (7,400 km; 4,600 mi) at 18 knots

Armament:

-Center turret, torpedo tubes, casemate guns, AA guns removed.

-4×3 135 mm (5.3 in) turreted guns

-Ten 90 mm (3.5 in) dual purpose single AA turrets.

-15(6×2 +3 single) Breda 37mm/45 (1.5 in) AA guns

-16 (8×2) Breda 20-millimeter (0.8 in) Modello 35 AA guns.

-Rebored main guns to 320 mm (12.6 in)

-New turrets with electric power.

-New mounts for fixed loading angle +12 degrees max elevation +27-30°

-New 320-millimeter AP shells 525 kgs (1,157 lb) 830 m/s (2,700 ft/s) muzzle velocity

-Maximum range 28,600 meters (31,300 yd)

By early 1942 the aft 20 mm were replaced by twin 37 mm mounts instead and relocated to Turret ‘B’ roof. Stabilized 90 mm guns mounts motors removed. The forward superstructure and integrated CT protected by 260 mm, fire-control director and its three large rangefinders reminded of the system developed for the Littorio.

Protection:

-135 mm (5.3 in) armoured deck.

-120 mm (4.7 in) thick faces secondary turrets?

-Pugliese system for ASW protection, large cylinder with fuel oil/water around to absorb torpedo blasts.

The Final tonnage diverged between the two classes, from 29,391 tonnes (Duilio) down to 28,882 tonnes (Doria)

Doria specifications 1940 |

|

| Dimensions | 186.9 x 29.2 x 8.6m |

| Displacement | 29,100 tonnes /29,400 tonnes FL |

| Crew | 1300? |

| Propulsion | 2 screws, 2 reduction turbines, 8 Yarrow boilers, 90 000 hp |

| Speed | 27 knots (40 km/h; mph) |

| Range | 6,700 nmi () |

| Armament | 10x 355mm (2×2, 2×3), 12 x135mm (4×3), 10 x90mm AA, 12x 37mm, 15x 20mm Breda AA. |

| Armor | Decks 135-166 mm, barbettes 130-280mm, belt 130-250mm, CT 250mm. |

Back into service

By that time, Italy had entered World War II on the side of the Axis powers. The two ships joined the 5th Division based at Taranto. Caio Duilio participated in a patrol intended to catch the British battleship HMS Valiant and a convoy bound for Malta, but neither target was found. She and Andrea Doria were present during the British attack on Taranto on the night of 11/12 November 1940. A force of twenty-one Fairey Swordfish torpedo-bombers, launched from HMS Illustrious, attacked the ships moored in the harbor. Andrea Doria was undamaged in the raid, but Caio Duilio was hit by a torpedo on her starboard side. She was grounded to prevent her from sinking in the harbor and temporary repairs were effected to allow her to travel to Genoa for permanent repairs, which began in January 1941.In February, she was attacked by the British Force H; several warships attempted to shell Caio Duilio while she was in dock, but they scored no hits. Repair work lasted until May 1941, when she rejoined the fleet at Taranto.

Caio Duilio in 1948

In the meantime, Andrea Doria participated in several operations intended to catch British convoys in the Mediterranean, including the Operation Excess convoys in January 1941. By the end of the year, both battleships were tasked with escorting convoys from Italy to North Africa to support the Italian and German forces fighting there. These convoys included Operation M41 on 13 December and Operation M42 on 17–19 December. During the latter, Andrea Doria and Giulio Cesare engaged British cruisers and destroyers in the First Battle of Sirte on the first day of the operation. Neither the Italians nor the British pressed their attacks and the battle ended inconclusively. Caio Duilio was assigned to distant support for the operation, and was too far away to actively participate in the battle. Convoy escort work continued into early 1942, but thereafter the fleet began to suffer from a severe shortage of fuel, which kept the ships in port for the next two years. Caio Duilio sailed away from Taranto on 14 February with a pair of light cruisers and seven destroyers in order to intercept the British convoy MW 9, bounded from Alexandria to Malta, but the force could not locate the British ships, and so returned to port. After learning of Caio Duilio departure, however, British escorts scuttled the transport Rowallan Castle, previously disabled by German aircraft.

Both ships were interned at Malta following Italy’s surrender on 3 September 1943. They remained there until 1944, when the Allies allowed them to return to Italian ports; Andrea Doria went to Syracuse, Sicily, and Caio Duilio returned to Taranto before joining her sister at Syracuse. Italy was allowed to retain the two ships after the end of the war, and they alternated in the role of fleet flagship until 1953, when they were both removed from service. Andrea Doria carried on as a gunnery training ship, but Caio Duilio was placed in reserve. Both battleships were stricken from the naval register in September 1956 and were subsequently broken up for scrap.

Andrea Doria at sea in 1943

Andrea Doria en route to Malta to surrender, September 1943

Andrea Doria en route to Malta to surrender, September 1943

Battleship Caio Duilo en route to Malta to surrender, September 1943

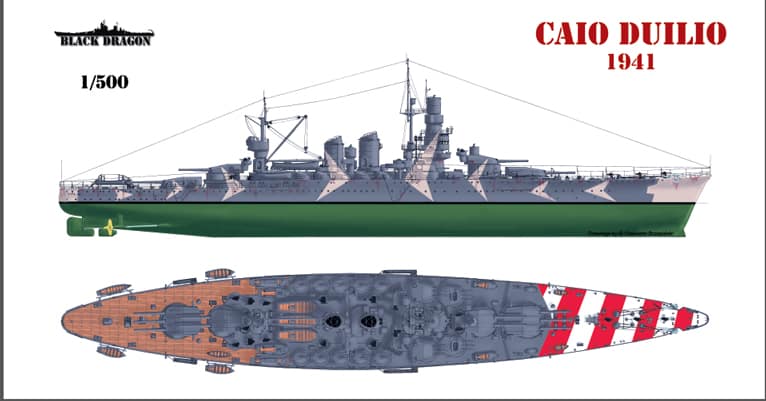

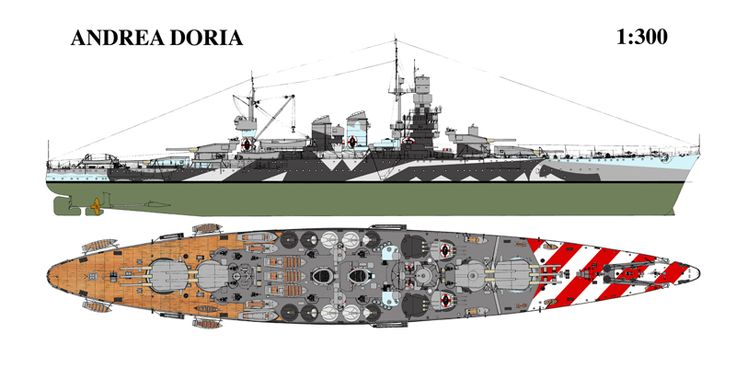

Various liveries of both battleships

Caio Duilio, fleet flagship May 1947 – November 1949 at Taranto

Links

Specs Conway’s all the world fighting ships 1922-1947.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrea_Doria-class_battleship

Author’s illustration of the Doria in 1941

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign