The great seism in naval matters

The battle of Tsushima is certainly one of the most significant battles of the XXth Century. In terms of size and scope, it was only comparable to Jutland, in May 1916, and the British compared it to Trafalgar. Its consequences, direct and indirect, were as dramatic and far-reaching into the XXth Century. For the first time, a non-European power defeated one in a standard naval engagement. This gave a new level of confidence to the Imperialists on the path of hegemon in Asia, right to the Pacific campaign during WW2. On the other side, this total, unmitigated disaster, was blamed by the Russian population on their elites, triggering a mutiny (Potemkine), mass public demonstrations, and a situation of growing unrest which will boil over in 1917 with the Revolution. The cold war arguably found Tsushima in one of its roots causes.

The roots of tensions with Russia

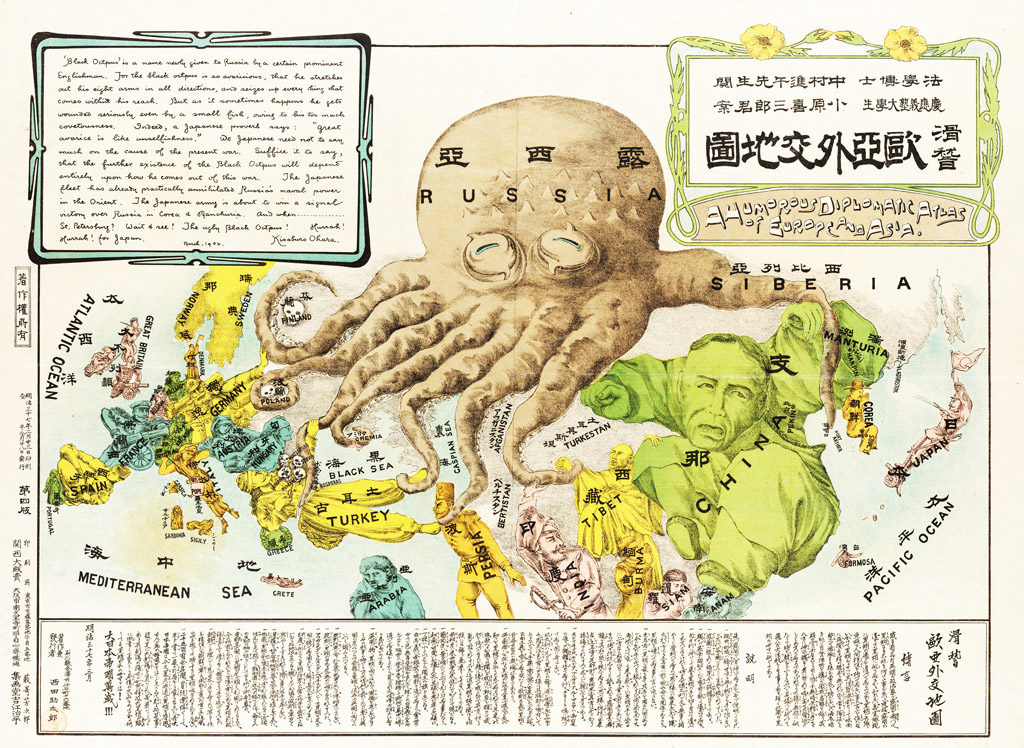

On the far East, only one major power stood to the growing local influence of Japan, after the defeat of the Chinese at Yalu. This was Imperial Russia, a giant present in three strategic areas, with three fleets: The Baltic, the Black sea, and the Pacific, from Vladivostok and Port Arthur. A name that will resonate around the world in the following events. A point of tension already in 1895-96 in Korea, was that King Gojong and his court fled to the Russian legation in Seoul after the murder by the Japanese of Queen Min of Korea, the leader of the anti-Japanese and pro-Chinese faction. Shortly after a popular uprising overthrew the pro-Japanese government. In Korea, after the peace treaty signed with Russia, France and UK on one part and Japan on the other, attempts to try to attach Korea in the Japanese sphere of influence were compromised. Eventually, in 1897, Russia has occupied the Liaodong Peninsula and built the Port Arthur fortress, which became the main naval base for the Russian Pacific Fleet.

The Russian occupation of Port Arthur was at first an anti-British move to balance the occupation of Wei-hai-Wei. Japan, perceived it as anti-Japanese. Soon after, Germany entered the fray, annexing Jiaozhou Bay, and created the Tsingtao fortress dominating the naval base dedicated to the German East Asia Squadron. Until 1903, Russia not only invested and built the Chinese Eastern Railway in Manchuria, on Russian gauge and with Russian troops stationed in Manchuria, but the headquarters were located in the new city of Harbin, the “Moscow of the Orient”. This attitude and the development of the railway did much to fuel anger which erupted in the Boxer Rebellion. The Russians also made inroads into Korea, contained many concessions near the Yalu and Tumen rivers, and started the construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway which could have been used to carry masses of reinforcing troops. The clock was ticking for the Japanese interests in that area. Indeed after the end of the Boxer rebellion, the Russians massed 100,000 troops in Manchuria, which in 1903 occupied the territory without any plan for withdrawing.

Peace attempts and alliances game

Minister Itō Hirobumi did not believe Japan had the necessary strength to take on the Russians militarily and therefore started negotiations, agreeing to officially recognise Russia control over Manchuria in exchange for Japanese control of northern Korea. He was back by old Meiji nobility members including the influent Count Inoue Kaoru while another faction was favourable to war. This hard-line position has its supporters like Katsura Tarō, Komura Jutarō, and Field Marshal Yamagata Aritomo. They were comforted by the 1902 Anglo-Japanese Alliance which was created to balance Russian influence over the area.

Since it was likely neither France or Germany would support Russia at war on two Fronts, and in the West, to UK, the hard-liners gained more support over time. On the other hand, Germany seemed favorable to Russia’s positions, praising the Tsar as the “savior of the white race” facing the “yellow peril” even before the Sino-Japanese war. Wilhelm indeed aggressively encouraged Russia’s ambitions in Asia while France, which was Russia’s closest ally showed great caution in that matter. Indochina was now indeed part of the French colonial Empire and towards this new competition, rather joined the British position. Officially, however, France declared their alliance with Russia was bound to Europe, and France would remain neutral if Japan attacked Russia. On the other hand, Russian authorities believed that they had the full support of the Reich in case of war.

The path to war

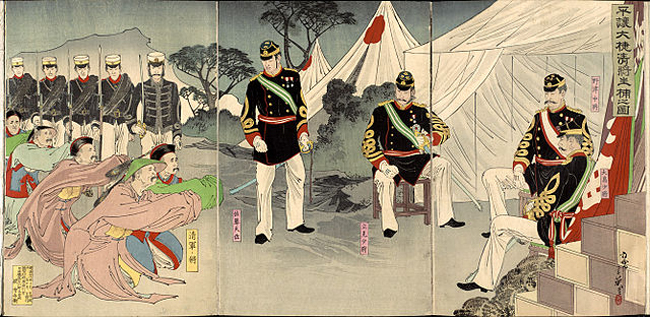

Extract from the 2008 TV serie clouds over the hill – japan’s best seller

By 8 April 1903, Russian troops still occupied Mandchuria and ambassador Kurino Shin’ichirō expressed the wish of the government in July to negotiate their stay or departure under return conditions. This was answered by Roman Rosen in Japan on 3 October. During negotiations, Russia scaled back its demands and claims regarding Korea. But the largest contributor to the degradation of relations and ultimately war was the fact the Korean and Manchurian issues had become linked. On Mandchuria, Japan expressed the will to open the country to free trade (seeking approval by Britain and the USA) as opposed to a Russian takeover. During this, Emperor Gojong of Korea cautiously chosen neutrality. On 4 February 1904 no answer was given to the last Japanese proposal, authorities there thinking Russia was not serious about seeking a peaceful solution. The Tarō cabinet already voted on 21 December 1903 to go to war against Russia and on 08 February, a declaration of war was issued while four hours before, the Russians experienced their own “pearl harbor”.

Attack on Port Arthur

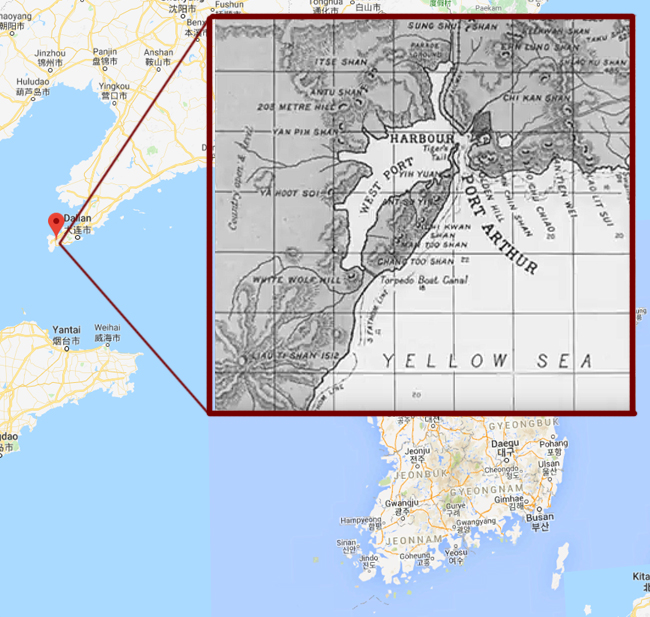

Exactly like in December 1941, the Japanese decided to strike first before negotiations were officially over, by an all-out attack on the Pacific fleet base at Port Arthur. This came as a shock for the Tsar, which only declared war in turn eight days after. In this struggle, the Qing Empire was favorable to the Japanese and offered support and goods. Locally, Mandchurian irregulars and levies joined both sides. For Japan, Port Arthur on the Liaodong Peninsula in the south of Manchuria was the key objective to take before any invasion of Mandchuria. The port-city was well-fortified and a naval assault was risky.

However, during the night of 8 February 1904, Admiral Tōgō Heihachirō ordered only his light ships to take the initiative. His torpedo boat destroyers penetrated the loosely guarded harbor at full speed, torpedoes several ships and almost sank the battleships Tsesarevich and Retvizan, and the cruiser Pallada. At dawn, the rest of the Japanese came at gunnery range to engage remaining ships, but was repelled by Russian fortified coastal artillery. Fire was imprecise and the result largely indecisive.

Composite map showing he location of port Arthur

Geographic situation of Port Arthur and respective spheres of influences

The naval siege

This situation dragged on until April, 16, and the death of Stepan Osipovich Makarov, the admiral. before that, Makarov received the command of the fleet in March and had the will to break the blockade. He sent the battleships Petropavlovsk and Pobeda out at sea, only to be caught in Japanese minefields and while the first sank with all hands including Makarov, the second was towed back to the port and left for repairs. From then, the fleet was even less enthusiastic about the idea to sail in open sea and engage the Japanese.

However this Japanese naval siege successfully locked in the Russians, which allowed and landing near Incheon in Korea to take place unopposed. In the end of April, Kuroki Tamemoto’s army was ready to cross the Yalu River, in Russian-occupied Manchuria. Meanwhile admiral Togo gave orders to block completely the port entrance by sending on 13–14 February concrete-filled steamers, which failed, as another attempt during the night of 3–4 May. The Russian in turn laid mines which claimed on 15 May 1904, the IJN battleships, Yashima and Hatsuse. The second survived but was towed in Korea for extensive repairs.

Breakout attempt: The battle of the Yellow sea

On 23 June 1904 the Russian fleet now under the command of Admiral Wilgelm Vitgeft which prepared a new breakout. The goal was to break through and join Vladivostok he would wait for reinforcement and stay in a better defended and better supplied position. He sailed with his flagship, the Tsessarevitch, in all six battleships, four cruisers, and 14 torpedo boat destroyers at dawn, 10 August 1904. Admiral Tōgō deployed four battleships, 10 cruisers, and 18 torpedo boat destroyers.

At 12:15 mutual visual contact was followed by artillery duels 8 miles away, a long distance at that time. Togo successfully crossed Vitgeft’s T, pounded the Russian line for 30 minutes and managed to hit the Tssessarevitch’s bridge, killing the admiral instantly. Confusion among her fleet soon arose and the flagship was only saved by the intervention of Retvizan, which drew the Japanese fire on him. He took command of the crippled fleet and decided to turn back home to port Arthur. he was then given the insurance of the reinforcement from the redeployed baltic fleet.

Delaying battles

Two other events showed the Russian trying to delay Japanese the advance: First was the battle of Yalu River on 1 May 1904, when Japanese troops stormed a Russian position after crossing the river, inflicting a decisive defeat and gaining a foothold, whereas the Russians were unable to sent reinforcements. At that time indeed, the trans-siberian railway was still stuck in Irkutsk. This feat which had no comparison gave immense confidence to the Japanese, perhaps explaining their losses later like the Battle of Nanshan on 25 May 1904, trying to force their way through well-entrenched Russian troops defending Port Arthur perimeter.

The siege turned to land

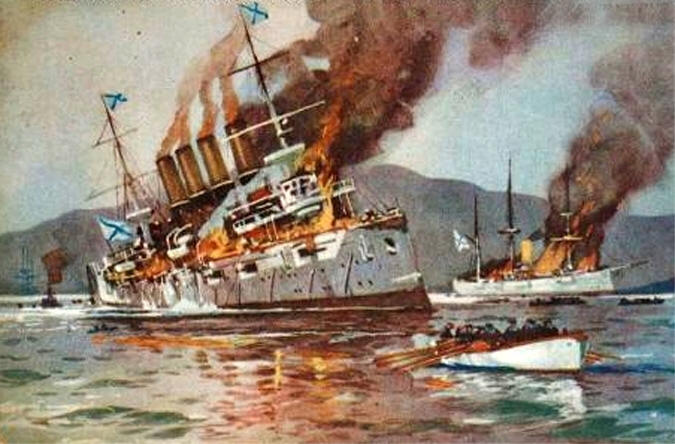

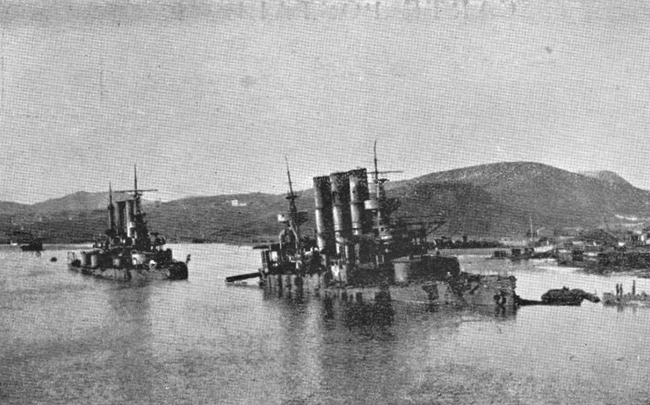

By then the Japanese Army had managed to approach Port Arthur on land, less well defended, and after a grinding trench and mortar battle since the end of April, managed to be close enough in December to bring heavy artillery (11-inch or 280 mm Armstrong howitzers) to bear on key positions on nearby hills. From then on the Russian position became untenable: The Pacific fleet was decimated, four Russian battleships and two cruisers were sunk in succession. The last battleship, badly damaged, was scuttled to prevent capture a few weeks later. This feat was unique in the annals of warfare and never repeated. Attempts to relieve the city failed: The Russian northern army was defeated at the Battle of Liaoyang in late August. After the Japanese detonated several underground mines to further damage the fortifications and closing the grip on the base, Major General Anatoly Stessel, the garrison commander, decided to surrender on 2 January 1905, without any approval of his staff and the Tsar.

Second phase: The intervention of the Baltic fleet

A seven month odyssey

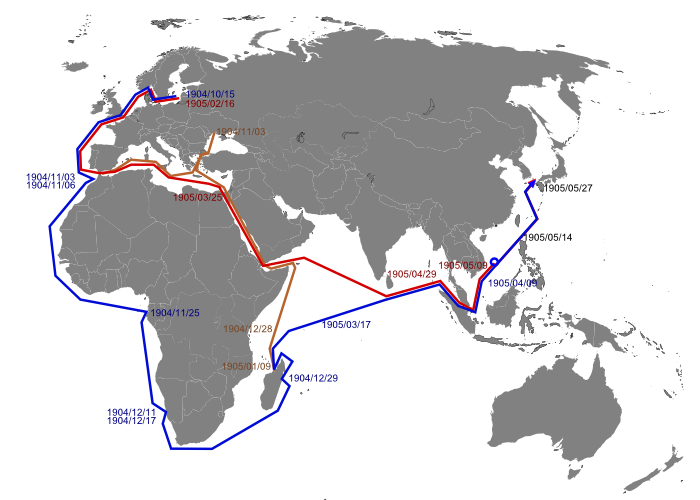

Having three fleets, the Russian could send reinforcements of one of these, despite the huge distances to travel. The easiest solution was to send the Black sea fleet, but poisonous relations with the Ottoman Empire prevented its passage through the Bosphorus. There was less risk of a war with its immediate neighbours in the Baltic, so the Tsar and his staff decided to redeploy the Baltic fleet to the Pacific. That was not a small trip, since Russia had not that many allies but a reluctant France along the way. In addition, the fleet under the command of Admiral Zinovy Rozhestvensky had problems with engines and supplies and only departed 15 October 1904. The Baltic fleet was to pass via the Cape of Good Hope in the course of a seven-month odyssey. The Suez canal was at first avoided as tensions were high with UK, allied with Japan.

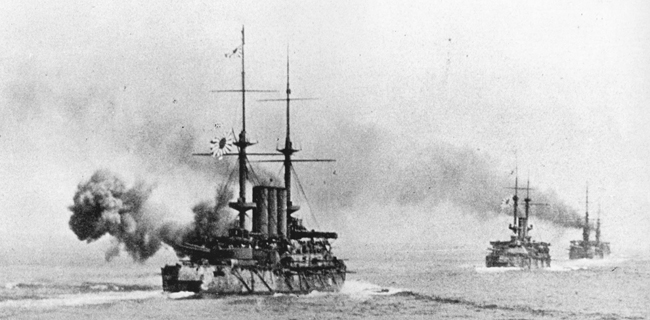

Battleship Borodino

Indeed, right at the beginning of the trip near the Dogger Bank, believing they faced British TBs, Russians TBs fired on British fishing boats on 21 October 1904. Needless to say this triggered official vigorous protestations and the Royal Navy was mobilized. War was avoided (and perhaps the world war would have erupted in 1905 instead of 1914, again, for the sake of alliances and global spheres of influence). The Russian Baltic fleet’s seven-month journey across the globe was a feat that drew a lot of media attention, making headlines as she progressed. The fleet split up when arrived near Gibraltar as the situation permitted it, cruisers and TBs making it through the Mediterranean and the Suez Canal while Battleships, which had more coal reserve and did not need frequent resupplies along the coat of Africa, went by the cape.

The land war (Jan-Feb 1905)

Meanwhile, Russian land forces attempted to drive out the invading Japanese in Mandchuria. The Second Army under General Oskar Gripenberg, arrived in 25-29 January at Sandepu and attacked Japanese positions by surprise, almost succeeding to get through. However the battle was inconclusive and ultimately he was held back by Kuropatkin which sent reinforcements. Both sides tried to beat each other, but the Japanese, in particular, were eager to get to a conclusion soon as for them the completion of the trans-siberian railway could be their undoing.

The second large battle erupted nearly a month after on 20 February 1905. This was the battle of Mukden, a Russian-built city, well fortified and a garrison. Kuropatkin had arrived, joined force with Gripenberg and was attacked by the Japanese on his right and left flanks around Mukden, along a 50-mile (80 km) front. About one million men in total participated in this major battle which lasted for three weeks in icy cold conditions. Eventually, the Russian front crumbled and eventually gave way, Kuropatkin ordering a fighting retreat to avoid being completely surrounded, having lost 90,000 men already. The Japanese failed to beat completely the Russians scattered in small groups and their Mandchurian auxiliaries while all eyes turned back to the sea for the decisive hour.

The battle of Tsushima

Prelude: The end of the Odyssey

The fleet made a several weeks stop at the small port of Nossi-Bé (Madagascar) then belonging to neutral France. The port lacked infrastructures but the Russian Baltic fleet was able to coal, resupply, and proceeded to Cam Ranh Bay, again an allied port, possession of French Indochina. The fleet arrived in Singapore Strait between 7 and 10 April 1905 and reached the Sea of Japan in May 1905. The squadron required 500,000 tons of coal to complete the journey and was not allowed to coal at neutral ports. So to achieve this feat the Russian admiralty had to improvise a fleet of colliers along the way, to supply the ships at sea. The fleet was eventually renamed “Second Pacific Squadron” upon arrival after 18,000 nautical miles (33,000 km). But they only had news that Port Arthur has fallen already in Madagascar. So Admiral Rozhestvensky plan was now to reach Vladivostok, resupply, have the crews rested and prepare for battle. However the shortest and most direct route passed through Tsushima Strait between Korea and Japan, surrounded by Japanese bases and home Islands.

Admiral Tōgō was not long to understand the only logical choice of his future opponent, and that he was heading to Vladivostok by the shortest route. He had plenty of time to have the ships drydocks, maintained repaired and resupplied and the crews rested when he was devising plans with his staff. He was to intercept the Russian fleet using apparently a medieval tactic he knew from his past of Samurai in the Boshin war.

Battle of the japan sea (1969) – starting clip

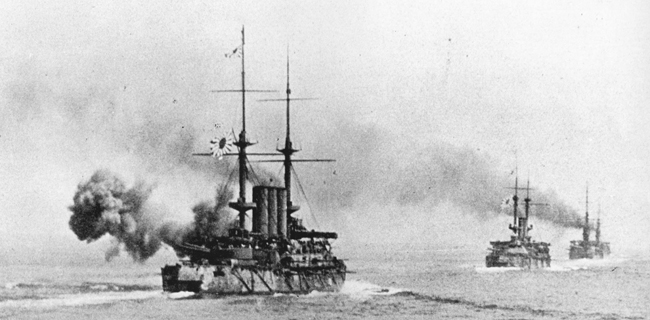

The Japanese Combined Fleet was down to four battleships, completed by a largely intact force of cruisers, destroyers, and torpedo boats. With eight battleships, including the recent Borodino class, and smaller ships for a total of 38 fighting vessels and auxiliaries, had an advantage on paper. In the end of May, the Second Pacific Squadron was travelling at night to avoid being spotted, which was betrayed by the two trailing hospital ships which had their lights open in compliance to international law, and were spotted by the Shinano Maru, equipped for wireless communication. Togo’s headquarters ordered a sortie and later received more informations from his scouting forces.

The fleet was able to be placed in order to “cross the T” of the Russian fleet, bearing al their broadsides on the column. On 27–28 May 1905, the battle began. This was to be the largest naval battle so far with modern, steel warships, made world headlines, and would attract postwar a lot of attention from naval experts. The Royal Navy was not long to take the lessons of this event and this was a determining factor in choosing to develop the monocaliber battleship concept.

Respective Forces

The Russian side: Needless to say such enormous trip, never done before by a modern military fleet, was astonishing by itself. But fighting just at arrival was just the same as an infantry corps wiped to exhaustion in forced marched in order to enter the battle immediately on arrival without rest. That was the same for the Russian fleet. The ships lacked maintenance, having no serious halt on their way during all these monthes (half a year voyage !) to be in shape, the crews were tired, as the clock was ticking in order to save Port Arthur, at least until they reached Madagascar. The rest of the trip was gloomy, with a plummeted morale.

Discipline was still there on the surface, but discontent was brewing among the crew already. Only the four new Borodino-class battleships were still in relative good shape. The other battleships led by Admiral Nebogatov’s 3rd Division were barely able to follow the line and were not able to put a good show. All the ships were heavily fouled, their speed of 14 knots barely maintained for short period while the Japanese were well above 15 knots, giving them some advantage in agility. Above that, the deficiencies in training and lack of budget were exposed, as well as Russian naval tests on torpedoes that showed grave malfunctions.

The Japanese side:

The victor was not obvious on paper at first. The IJN combined fleet was on paper inferior, half the number of battleships. However the ships were recent and in almost pristine condition despite an intensive service. Admiral Tōgō was himself already an aged, veteran captain with battle experience aplenty, at sea recently. His fleet comprised 5 battleships, 27 cruisers, 21 destroyers, 37 torpedo boats and gunboats plus auxiliary vessels for a total of 89, but the latter did not took part in the battle proper, being too slow and vulnerable for the task. The Russian fleet was more battle-oriented, with more battleships, 8 “regular ones”, 3 coastal battleships, but also less cruisers, only 6, and far less destroyers, only 9. Anyway they played little roles on both sides, which gunned themselves to oblivion, although torpedoes were aggressively used.

The battle

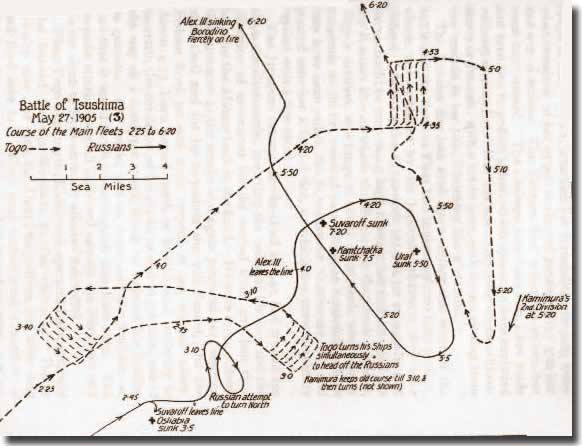

Afternoon action

Way before even spotting the Russian directly admiral Togo placed his fleet in order to block the column, or “cross the T” of his opponent. This classic tactic that was repeated at Jutland and other occasions allowed the whole Japanese line to open fire concentrated on the first ship, generally the admiral’s flagship. Not only it could cut the head of the staff and disorganise the fleet but also allowed to engage targets as they went maximizing firepower while the opponent only had its front guns to answer. The next move was for the targeted fleet was in general to turn and form an opposing broadside column. Needless to say these manoeuvers were extensively drilled and required precision. When the stage was set, as Togo remarked, the weather was fine, with a clear sky allowing long range sighting but high waves. All along, wireless reports came from scouts that shadowed the Russian formation.

At 13:40, both fleets sighted each other and 15 minutes after Tōgō hoisted of the Z flag on Mikasa, famously ordering to the fleet “The Empire’s fate depends on the result of this battle, let every man do his utmost duty.” Fire commenced on the Japanese side at 14:45. The Russians were sailing to north northeast while the Japanese were steaming from northeast to west and turned in sequence, take the same course as the Russians in classic parallel lines. Tōgō’s U-turn was masterful but Russian gunnery was good. Mikasa was hit 15 times in five minutes and later 15 more times, all by large caliber. Admiral Rozhestvensky choosed the formal pitched battle option, based on his superior numbers of heavy guns. At 14:08, the range fell to 7,000 metres, and then 6,400 meters but eventually Superior Japanese gunnery skills and sights took their toll on the Russian battle line. Formed by, and equipped as, the Royal Navy, gunnery accuracy was the order of the day.

Vladimir Semenoff, on his flagship Knyaz (“count”) Suvorov, vividly remembered the carnage of Japanese guns “Shells seemed to be pouring upon us incessantly one after another. (…) In addition to this, there was the unusually high temperature and liquid flame of the explosion, which seemed to spread over everything”. Indeed this pounding, rather than a fair duel, raged on for another 90 minutes, until the first loss, Russian battleship Oslyabya (Rozhestvensky’s 2nd Battleship division flagship). Fuji managed to hit the ammunition magazines of Borodino, causing her to explode. She quickly sank with all hands but her billowing smoke engulfed the scene and reduced fire accuracy a bit. When the evening came, Rear Admiral Nebogatov took command, but soon the Knyaz Suvorov, Imperator Aleksandr III and Borodino added to the losses while the Japanese ships suffered less. Only a few light ships were lost.

Phase 3 of the battle

Night action

Since the Russian fleet still hold some major ships it was by then unthinkable to surrender. The plan was still to reach Vladivostok. That was precisely the Japanese wanted to avoid. Togo despatched at 20:00, twenty-one destroyers and 37 torpedo boats to hunt down and finish off the Russians. The vanguard was struck by destroyers while the flanks were attacked by the torpedo boats (east and south). Torpedo attacked went on for three hours without a break. Obscurity and some confusion caused several collisions but this succeeded in scattering the Russians, all trying to break northwards. They disappeared shortly, only to be betrayed by their searchlights. Navarin struck a mine, stopped and was torpedoed like a sitting duck. Sissoi Veliky was torpedoed and was scuttled the morning. Armoured cruisers Admiral Nakhimov was torpedoed but survived, while Vladimir Monomakh collided with a Japanese destroyer and were scuttled also the next morning. The Japanese only lost three torpedo boats during this fateful night. Japan will prove its mastery of night fighting in future engagements in WW2, like at Savo.

The end of the chase

At 09:30, 28 May, the crippled remnants of Nebogatov’s Russian fleet was spotted, sluggishly escaping, allowing Tōgō’s battleships to catch up and surround it south of Takeshima island. Like at the Yellow sea, fire opened at12,000 meters. By then it was clear to the Russian admiral that he was out-ranged by a safe margin and that his six remaining ships were condemned. Rather than having these destroyed without being able to replicate he ordered them to surrender, hoisting the XGE signal of surrender. However unfortunately for the Russians, this signal was absent from the Japanese code books and continued pounding the fleet.

Amazingly, Nebogatov had white table cloths sent up the mastheads. However, Tōgō did not trusted this new signal an still resumed fire. When it was clear nothing will prevent total destruction, Russian cruiser Izumrud broke formation and attempted to flee. A desperate Nebogatov then hoisted the Imperial Japanese Navy flag and stopped, trying to be understood. This was spotted by Togo, which ordered to cease fire. Both fleet stopped, and Nebogatov embarked in a yowl to negotiate his surrender. As stated to his crews, he knew that for disobeying orders he could have been shot, but wanted to avoid useless slaughter, pleading his men to one day “retrieve the honour and glory of the Russian Navy”.

Upon their return in Russia both admirals faced trial, Rozhestvensky (which survived his wounds but was unconscious during the battle) claimed full responsibility. Their reputations were ruined although the second was pardoned by the Tsar and the first saw prison. The remainder of the Russian squadron, only three ships, reached Vladivostok. Many of these ships had been captured by the Japanese, in addition to those scuttled or damaged in Port Arthur. Not only Togo secured an impressive tonnage of new battleships and cruisers, but he won against two fleets, having lost only two battleships and three destroyers during the whole campaign.

Epilogue: The battle and its consequences

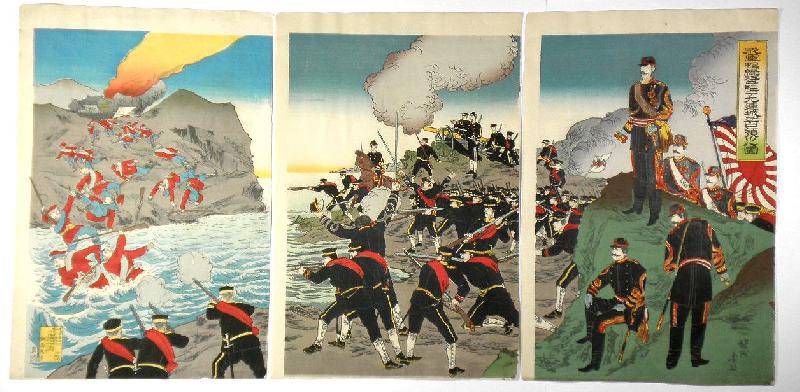

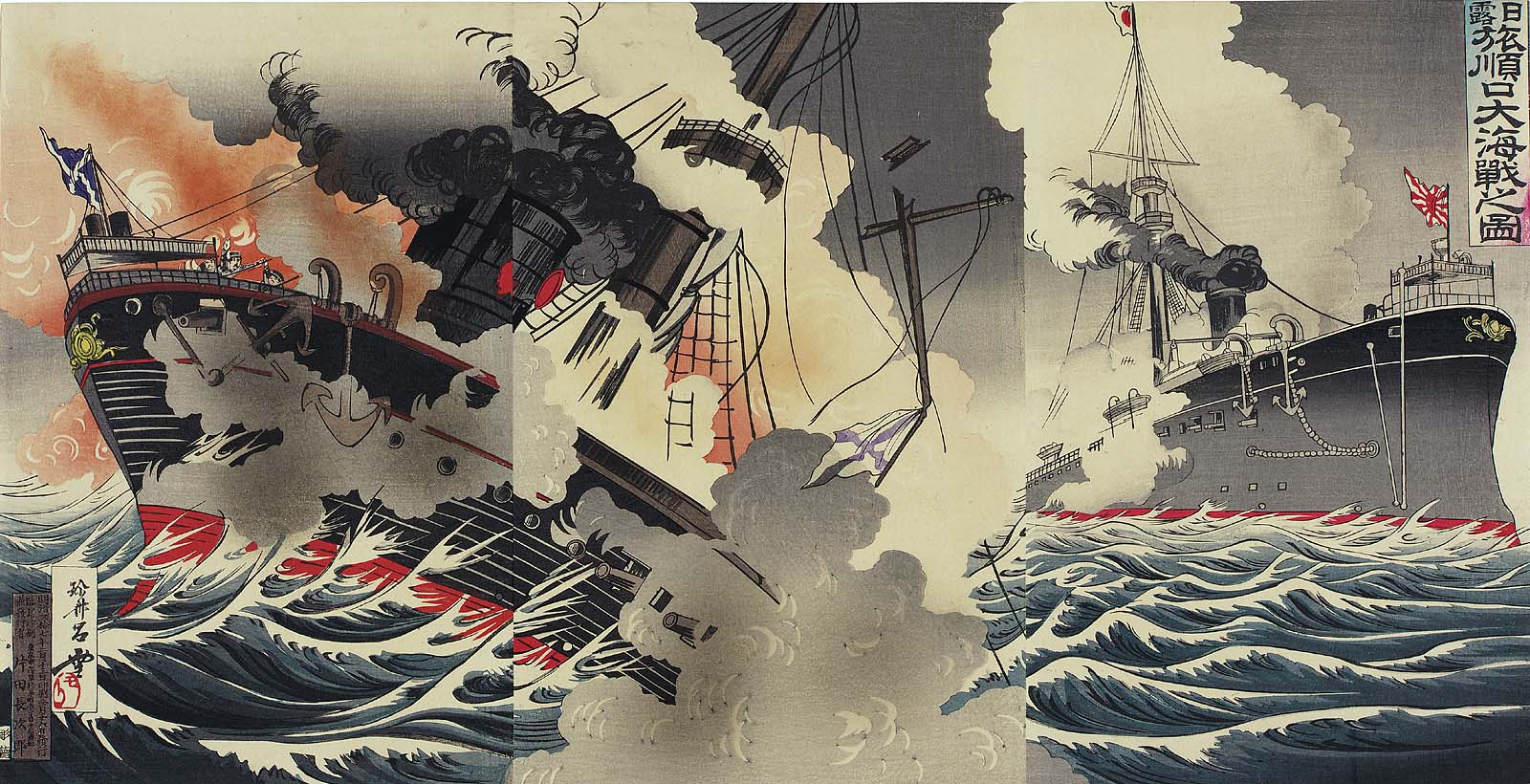

Illustration of the Great Naval Battle at the Harbor Entrance to Port Arthur in the Russo-Japanese War (Nichiro Ryojunkô daikaisen no zu)

The Russians lost their entire second pacific fleet, that is to say their entire Baltic fleet, the spearhead of their maritime might. Eight battleships, numerous smaller vessels, and more than 5,000 men, while the Japanese lost three torpedo boats and 116 men. Three Russian vessels made it to Vladivostok. Immediately after, a combined naval amphibious assault allowed Japan to occupy Sakhalin Island, to force the Russians to sue for peace. The war was lost, with 2/3 of her fleet for the Russian Empire. This nailed down any possibility of future expansion and gravely impacted the country’s morale at all levels.

Towards the Europeans, this further demolished any credibility the Russians built, including towards traditional allies like France, or potential ally like the German Empire, and comforted great Britain on its choice of Japan as an Asiatic ally. At home, the resentment of the crews towards their elites would boil down to open mutiny in the remaining black sea fleet (Potemkine), mirrored by popular bread revolts, brutally suppressed. It contained the germs from which the revolution would blossom, with the court’s reputation as a primer, and the Great war as a catalyzer.

In Japan, the result of Tsushima was diametrally opposed. It gave a supreme confidence to the head of staff, the Emperor and the shut the moderates about Japan’s aspirations to a natural leadership in Asia, even against other European powers, like Great Britain, the Netherlands or France. The militarism of the post-WW1 years further fuelled by the anger caused by limitations by the 1922 Washington treaty, would see the hard-liners ruling the country, pursuing an aggressive agenda over China, after annexing Korea and Mandchuria. Tsushima’s date entered the calendar and was made a national holiday, and still is, while Battleship Mikasa has been preserved and can be visited today. This event was commemorated in many books over the years, like the bestseller “clouds over the hill”, made into a TV serie in 2008, or a 1969 high budget film starring Toshiro Mifune as Togo and an international crew and casting.

On naval standpoint alone, the battle showed that long-range gunnery, as demonstrated already in the Yellow sea in 1904, was the order of the day, secondary artillery playing no significant role, nor light ships like destroyers and TBs. This confirmed many British heads of staff, including admiral Fisher (not mentioning the rest of the world) that only the monocaliber type battleship was the way forward. With twice the budget required for such ships, it triggered a European arms race which had few precedents in history, that is the “dreadnought fever”. Tsushima did not exactly spawn the Dreadnought out of the blue. The idea was Fisher’s already since 1900 and in 1904 he was finalizing a design, also inspired by Cuniberti’s new armoured cruiser types revealed in Jane’s.

But the first modern battleship’s final design was approved, on 22 February 1905 containing indeed several observations from the recent war, including one related to ASW protection on the Russian battleship Tsesarevich. In fact both the Battle of the Yellow Sea and the Battle of Tsushima were carefully analyzed by Fisher’s Committee, Captain William Pakenham’s remark about 12-inch gunfire demonstrating hitting power and accuracy was a justification for a dispensable secondary artillery as “it went unnoticed”. The Yellow sea battle on its part confirmed that long-range (13,000 metres or 14,000 yd) fire was possible and even desirable with the right sights and calculators.

Among other factors it was observed that, gunnery training paid off -on the Japanese side- and the choice of using HE shells also versus the Russian AP shells, which in addition used small guncotton bursting charges and unreliable fuses. Also for the Russian ships bad accuracy, fire smoke was to blame, as easily burning paintwork and the large quantities of coal stored on the decks for the trip were to blame. Japanese accuracy was compounded by the use of recent (1903) Barr and Stroud FA3 coincidence rangefinder while the Russian trusted a variety of older models (their ships were built in several foreign shipyards, like 1880s to 1890s Liuzhol rangefinders which conceded 2000 yards to the Japanese.

About Admiral Togo

Togo was a Samurai fighting during the Tokugawa conflicts (1863–1869). He was aged 15 and part of a gun crew defending the port of Kagoshima, shelled by the Royal Navy. The Satsuma faction soon created a navy and he enlisted to served during the during the Boshin War on the Kasuga. He studied English at Yokohama after the war and perfected himself with Daisuke Shibata and Charles Wagman form The Illustrated London News. In February 1871, Tōgō was one of the selected officer cadets to travel to Britain, perfecting their naval studies.

Togo was a Samurai fighting during the Tokugawa conflicts (1863–1869). He was aged 15 and part of a gun crew defending the port of Kagoshima, shelled by the Royal Navy. The Satsuma faction soon created a navy and he enlisted to served during the during the Boshin War on the Kasuga. He studied English at Yokohama after the war and perfected himself with Daisuke Shibata and Charles Wagman form The Illustrated London News. In February 1871, Tōgō was one of the selected officer cadets to travel to Britain, perfecting their naval studies.

Additional photos of the Mikasa

He gained later a commission in the training vessel HMS Worcester, completed his gunnery training onboard HMS Victory, and he returned home on 22 May 1878 as a Lieutenant onboard IJN Hiei, freshly built in UK. He will first had combat experience during the Imo Incident in Korea, commanding a landing party. Promoted captain in 1884 he used to interact often with the British, American, and German fleets, thanks to his mastery of English. He will further learn in combat onboard Amagi as a closely observed during the Franco-Chinese War (1884–1885) and the French fleet operations by Admiral Courbet and observed Joseph Joffre troops in Formose. He was captain of the cruiser Naniwa in 1894, when the First Sino-Japanese War broke out. He sank a British transport ship, Kowshing, operating with the Beiyang fleet, and took part in the Battle of the Yalu River under orders of Admiral Tsuboi Kōzō, helping sinking the cruisers Jingyuan and Zhiyuan. He was promoted in 1895 rear admiral.

He became for a time the commandant of the Naval War College in Tokyo, commander of the Sasebo Naval College and later was recalled as admiral on May 20, 1900, patrolling along the coast during the Boxer rebellion. Afterwards he will supervise naval construction at the naval base at Maizuru. Navy Minister Yamamoto Gonnohyōe, when appointing Togo, was asked so by the Emperor, answering “the man has luck”. Luck he has, but certainly skills as well, masterfully using his meager forces to defeat two Russian squadrons, loosing only three torpedo boats. He became a war hero at his return to Japan, kept his journals in English, believing he was the reincarnation of Horatio Nelson. Being fluent in English he was invited to the USA and in UK, honored guest of the coronation celebration. He was made Marshal-Admiral of the IJN and was ho,nored by the Emperor koshaku (marquis) in 1934 just before passing out. He was accorded a state funeral, with naval attachés of many nations in the attendance and a naval parade was held in his honour in Tokyo Bay.

Video: A documentary and 3D recreation by kings & general channel

Read More

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Russo-Japanese_War

https://www.britannica.com/event/Russo-Japanese-War

Video (clip): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KFfiNM2o-BM

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JmyqbGgBG04

Movie Battle of the Japan sea 1969 https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0064733/

Depiction in WoW https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g5Gy8-vT4-8

Nihhon Kaigun

Nihhon Kaigun

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign