United Kingdom (1895) – HMS Powerful, HMS Terrible

United Kingdom (1895) – HMS Powerful, HMS TerribleWW1 RN Cruisers

Blake class | Edgar class | Powerful class | Diadem class | Cressy class | Drake class | Monmouth class | Devonshire class | Duke of Edinburgh class | Warrior class | Minotaur classIris class | Leander class | Mersey class | Marathon class | Apollo class | Astraea class | Eclipse class | Arrogant class | Highflyer class

Pearl class | Pelorus class | Gem class | Forward class | Boadicea class | Blonde class | Active class | Bristol class | Weymouth class | Chatham class | Birmingham class | Birkenhead class | Arethusa class | Caroline class | Calliope class | Cambrian class | Centaur class | Caledon class | Ceres class | Carlisle class | Danae class | Cavendish class | Emerald class

The Anglo-Russian naval arms race

Before the better known anglo-german naval arms race of 1906, the British press were scared, as the government and ultimately the Navy that had no apparent answer, to the known construction in 1890 of a massive Russian cruiser, Rurik, specifically intended in case of war to act as a commerce raider in Asia, with enough range to create havoc from the Kamchatka to the Indian Ocean. Not knowing her exact specifcation, the admiralty rapidly drafted two cruisers to compete. This was the first step of a naval arms race which also comprised the Russian replay, with the three Pereviet support “fast battleships” and the British Centurion class.

Two record-breaking cruisers

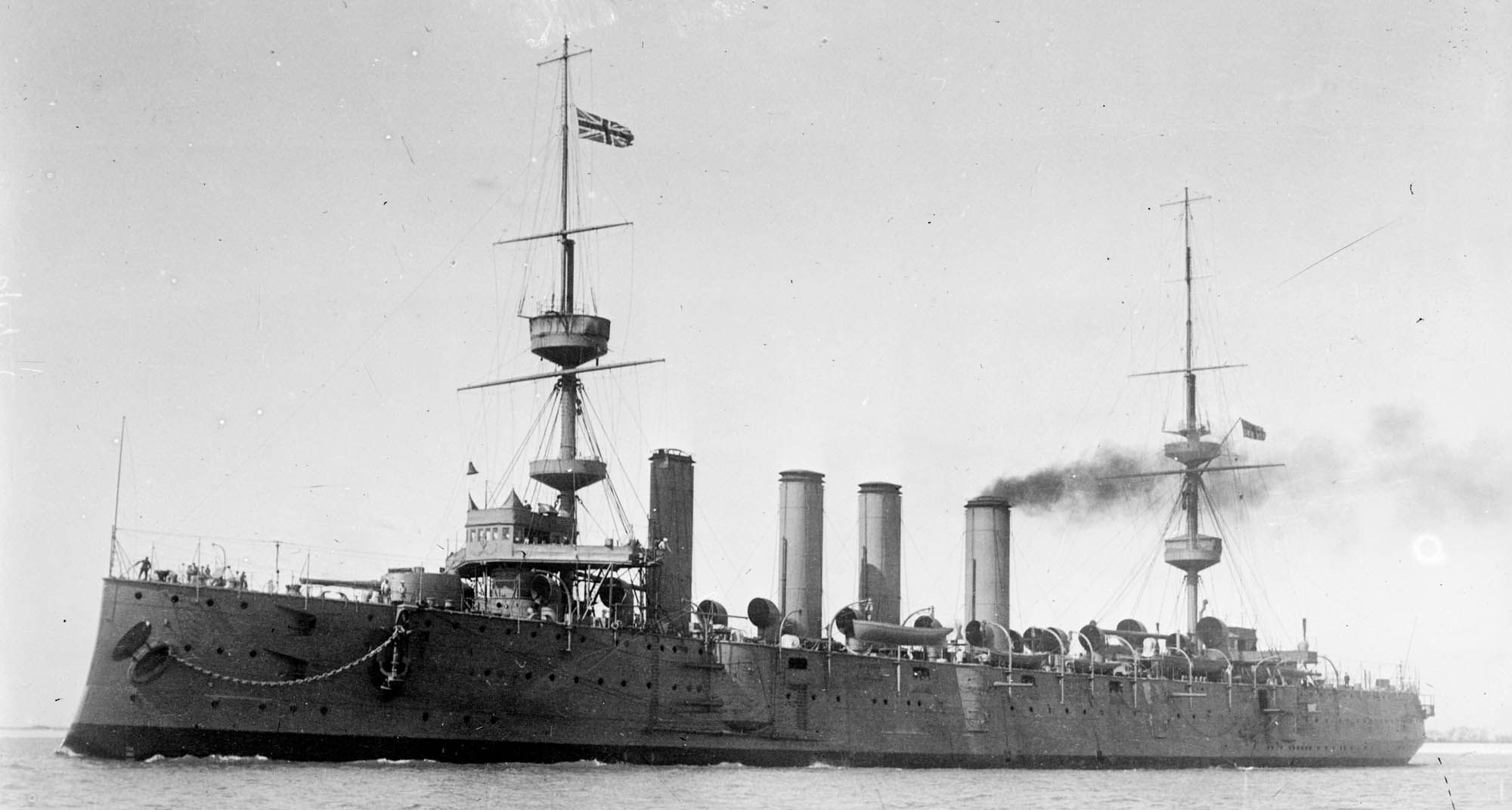

The Powerful class cruisers were two impressive vessels trigerred by the “russian scare”, the paranoia-inflated, massive Russian cruiser was in construction in 1890 (indeed the largest at the time), planned to prey on British Merchant trade in the far east at a time of high tension between the two Empire, betwene Afghanistan to iran to Asian waters. To answer the Rurik and announced designs sur as the Rossiya and Gromoboi, the Royal Navy ordered two massive cruisers. Outside purely technical aspects, which perfectly embodied British naval supremacy of the time, as real military ships, they were in fact retrospectively regarded as of “great white elephants”. Their construction at Vickers, Barrow in Furness and J&G Thompson, Clydebank cost the British taxpayer around £740,000 in 1894–98, their career being relatively short and uneventful, but at least they did participate in WWI.

As answers to the Rurik and Rossia, then were certainly designed to be better, and in turn, took the title of “largest warships afloat”. Upon completion in 1897 and 1898, with a construction span of 4-5 years, unusual for British ships, they took over the torch of largest warships in the world. Tellingly named “Powerful” and “Terrible”, their displacement was twice that of all previous cruisers like the Edgar class, costing also twice. Their crew approached 900 officers and men, also contributing to an expensive maintenance, which sealed their fate as soon as paranoia dropped.

HMS terrible

Design of the Powerful class

The opposing Russian cruiser Rurik.

Then political pressure urged the construction of both cruisers, the Admiralty was caught its hands full with an ongoing, extensive naval construction program mandated by the Naval Defence Act of 1889. Some preliminary discussions, delayed by the situatio were held eventually in November 1891, but it’s only in 1892 that William White, by then the Director of Naval Construction, that sketch designs were prepared for a heavily armed, large cuiser, with at least as well armor as the previous Edgar class, but also faster and with the range to chase and catch if possible Rurik and her successors, but also the willinness of the Russian admiralty to seize fast ocean liners in 1885, converted as armed merchant cruisers. The question of fast, large transatlantic liners clipping the waves was also a question that hauted Britush engineers as well as Russian’s and weighted much in the design of the new cruisers.

White’s preliminary studies concluded that an enormous load of coal would be necessary for her mission, because she would not have the luxury or re-coalling along the way. A large number of boilers were also necesary to achieve the desired speed, making the prospective ship having a “mammoth hull”, as large and roomy than an ocean liner. It was soon established more than 100 feet (30 m) longer than the Majestic-class battleships of the time, or the Edgar class.

Maintain high speed in heavy weather also dictated this large and long hull was also tall, and White gave her a freeboard one deck higher than battleships or cruisers. For that matter, it was expected to make these ships very seaworthy. White also though using the new lightweight and efficient Belleville water-tube boilers recentkly developed would spare weight and allowing to achieve the required speed while allocating even more space for coal. However, conservatives in Parliament and the Admiralty both resisted the idea of using such bolers, arguing recent RN’s failures with these in the past. They wanted extensive trials conducted with HMS Sharpshooter first. These would later proved to be a complete success, and this design perk gained approval. White was greelighted for the whole design on 23 October 1893, at the time Rurik was still in completion, recently launched. The cruisers were ordered in the 1893–1894 Naval Estimates.

Hull’s construction

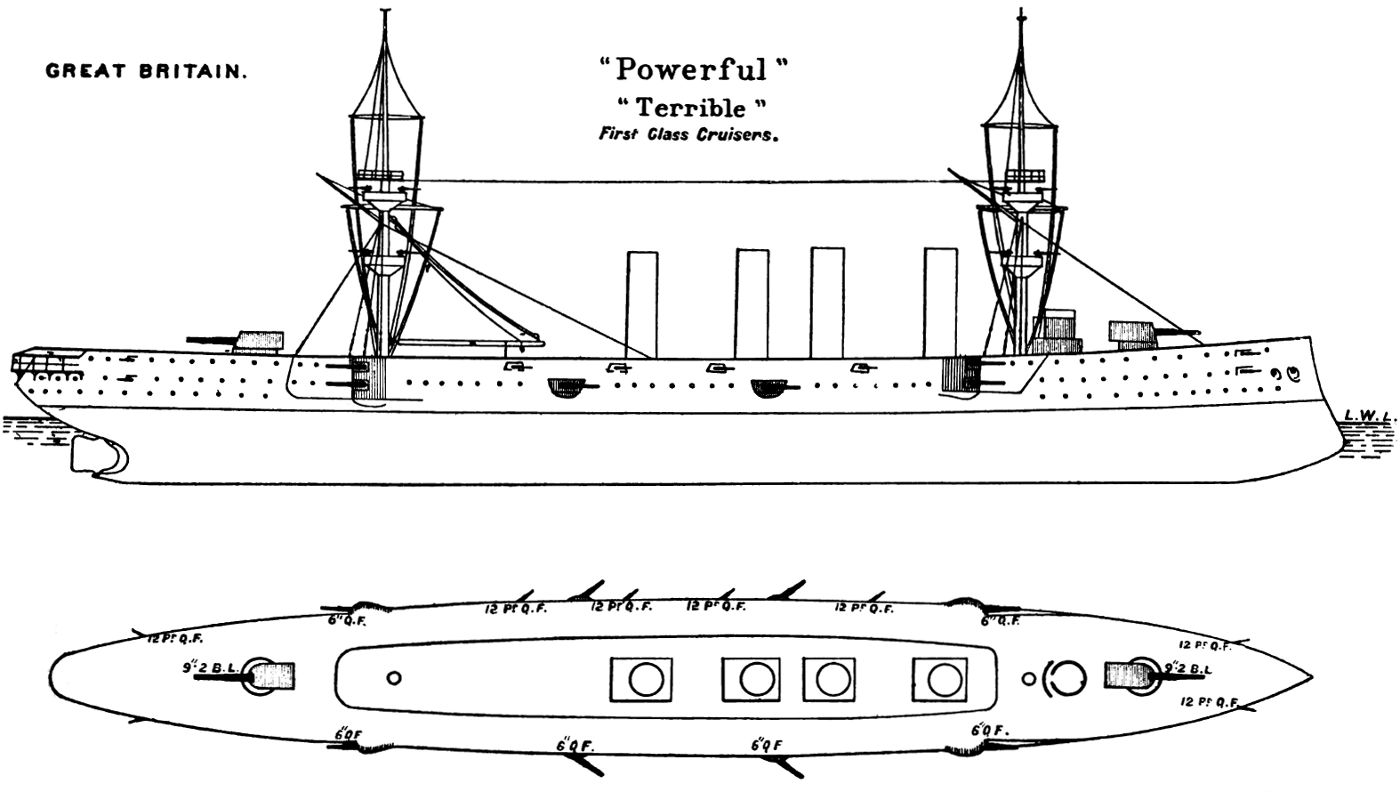

Powerfulas depicted in Brassey’s 1902, really a liner-lloking cruiser

The Powerful class displaced 14,200 long tons at normal load, and an estimated 18-19,000 fully loaded (no figure available). This was still way larger than Rurik or the Rossia class. They had an overall length of 538 feet (164.0 m) for 71 feet (21.6 m) at their greatest beam, and 27 feet (8.2 m) draft. Designed for overseas service they had wooden-sheathed hulls to prevent biofouling, and internal arrangements to prevent inner compartments overheating, notably for ventilation and in the materials used. The hulll was constructed with a double bottom, subdivided into 236 watertight compartments. Deep load metacentric height was calculated to be 2 feet (0.61 m) and 2.65 feet (0.81 m) on Terrible and Powerful respectively. Complement as designed was considerable, with 894 officers and ratings, largest of any Royal Navy ship ever built. With their tall, triple deck hull dotted with rows of portholes, two masts and four funnels they somewhat looked like oceanic liners.

Machinery

Technically, they were the first ships of this size to employ water tube boilers of the Belleville type, a world’s firts soon adopted worldwide. It raised concerns about their development and accumulated teething problems. They were powered by two 19 ft, 6 in (5.9 m) propeller, which shafts driven by vertical inverted four-cylinder triple-expansion steam engines. Steam was provided by a record-breaking 48 Belleville small tubes boilers, at a working pressure of 210 psi (1,448 kPa; 15 kgf/cm2).

Total expected output was 25,000 indicated horsepower (19,000 kW) at forced draught for a top speed as designed of 22 knots (41 km/h; 25 mph), way better than the 19 knots capable Rurik. It was also higher by 3 knots than the previous Edgar class. On trials they even reached speeds up to 21.8–22.4 knots (40.4–41.5 km/h; 25.1–25.8 mph), with forced heating, at 25,572–25,886 ihp (19,069–19,303 kW). Normal peacetime coal load was 1,500 long tons, enough for 7,000 nmi (13,000 km; 8,100 mi) at 14 knots, up to 3,100 long tons when filling all void compartments in wartime, making them the largest coal bunkers capacity in the Royal Navy. This was enough for a 12,000 nm or more range, with more frequent 20-knots runs as expected in their role.

Their machinery was satisfactory in general. They were seen as efficient steamers throughout their service. After early service, their four funnel appeared too short for efficient exhaust, and were raised from five meters (20 feets), also to avoid obscure observers in the fighting tops. Not quite agile, they did well as expected in heavy weather, made good, stable platforms with a predictive roll, and were still recognized as good sailors and walkers.

Armor scheme

HMS Powerful, brasseys Naval Annual 1896

The powerful class cruisers used Harvey armour:

-Gun turrets 6 in (152 mm) face, sides, 1-inch (25 mm) roof.

-Main turrets barbettes 6 in (152 mm)

-Secondary guns casemates 6 in (152 mm) with 2-inch (51 mm) rear plates.

-Conning tower 12-inch (305 mm) plates

-Curved armoured deck 3 feet 6 inches (1.07 m) above the waterline with 6 feet 6 inches (1.98 m) edges below the waterline.

-Armored deck 6 in (152 mm) thick over machinery

-Armored deck 4 in (102 mm) thick over the magazines

-Same, 2.5 inches (64 mm) thick in the middle section.

-Gull bottom 1 foot (0.3 m)

-Upper protective 2.5 inches thick.

Armament

Their roomy configuration above the waterline made them roomy enough to accomodate more ammunition han usual, but their armament and its distribition remained classic for the time, with a majority of their twelve 6-in guns in casemated two-storey sponsons, two twin 9.4-in in fore-aft turrets. In 1904 the Navy still found them underarmed and added four extra 6-in guns on their upper deck.

- Two turreted 9.2 in (234 mm) guns (deck guns for and aft)

- Twelve single 6 in (152 mm) guns in casemates along the hull, four twin with recesses and four single.

- Sixteen single 12-pdr (3 in, 76 mm) QF Vickers guns, all in casemates

- Twelve single 3-pdr (47 mm (1.9 in)) Hotchkiss QF guns on the decks and fighting tops

- Four 18 in (450 mm) torpedo tubes, in submerged broadside pairs.

HMS Powerful naval Brasseys diagram

The Royal Navy great white elephants

William_Mackenzie_Thomson_HMS_Powerful_1st_Class

Modern historians compared them often to the USN Alaska class of 1943 in that the latter were also ordered after a “Japanese cruiser scare” which proved false, and did not fit anywhere in the Navy’s scheme after completion, having little wartime service, and not long afterwards either. Like them, the Powerful class would revealed themselves “overkills” compared to the cruisers they were supposed to match, they were larger, faster, better armed than Rurik, but also the Rossyia and Gromoboi.

Observers in the contemporary magazine “The Engineer” at the time also criticised these for their light armament compared to their great size. White replied in an open letter by pointing out that they could not take additional ammunition due to internal space design, and the need to carry coal instead. He added their armament still “accounted for 27% more in displacement compared to the Edgar class, and rotected by 660 long tons (670 t) of armour, versus 40 long tons (350 t)”

The Admiralty nevertheless did not found the ships satisfactory in service, having a crew 64% larger than the Edgars (so equivalent to two cruisers), while costing 61% more in maintenance with basically the same armament. Naval historian Antony Preston also underlined the “extreme folly of building cruisers to match specific opponents”, in that case, a semi-imaginary threat as the Russian curisers never were such a threat in the end. In practice the were created opponents they never met, as their 1902 alliance with Japan had the latter decisively defeat the Russians and liminate the threat in 1905 for good, leving the Royal Navy wih two massive, costly cruisers without purpose. The admiralty instead just wanted affordable ships in larger numbers. No navy would ever match either the Powerful class, that were just too large and expensive for their own good. They faded away in menial roles and were retired faster than other British cruisers.

Links

The Powerful class on wikipedia

On historyofwar.org

Specs Conway’s all the world fighting ships 1860-1905.

Powerful class specifications |

|

| Dimensions | 164 x 21,6 x 7,3 m |

| Displacement | 14,200 t FL |

| Crew | 894 |

| Propulsion | 2 screws, 2 VTE steam engines, 48 Belleville WT boilers, 25,000 hp |

| Speed | 22 knots (40.7 km/h; 25.3 mph) |

| Range | 7,000 nmi (12,960 km; 8,060 mi) at 14 knots (25.9 km/h; 16.1 mph) |

| Armament | 2x 254, 12x 152, 16x 76, 12x 47, 4 TT 457 mm (SM) |

| Armor | Deck: 2–6 in (51–152 mm) Barbettes: 6 in (152 mm) |

Gallery

HMS Powerful illustration in 1914.

HMS Terrible

The Powerful class in action

Early in their careers, the two ships were based in China, then rallied South Africa to carry troops and support infantry companies. In 1899, they made the big titles of newspapers when landing vanguard troops to support Ladysmith during the Boer War.

In 1902-1904 they were the subject of a small redesign and were set aside as being considered too expensive for service. Only in 1915 HMS Terrible was reactivated, used as a troop transport. She rallied the Mediterranean, then returned in reserve at Portsmouth, reclassed as an utility ship at anchor until 1920. Renowned Fisgard III she then served as a training ship until 1932.

The HMS Powerful came out of the reserve in 1915 to serve as a training ship in Devonport. Her vast dimensions made it well predestined for this new duty. She continued this service from 1919 under the name Impregnable II until 1929, before being stricken, sold off and later broken up.

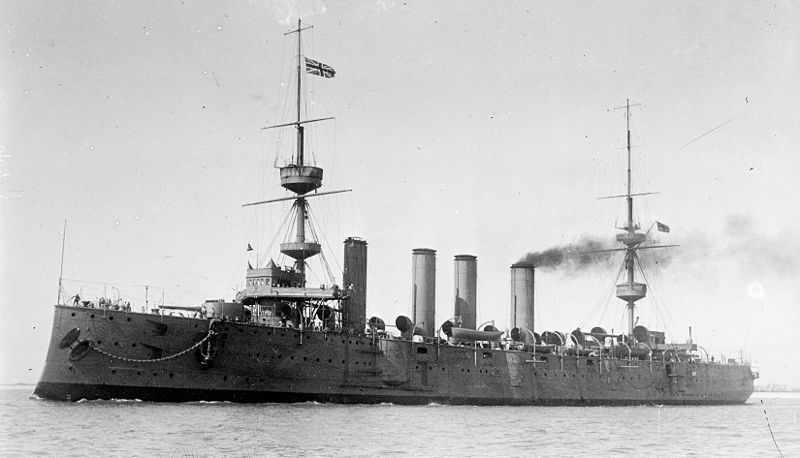

HMS Powerful

HMS Powerful circa 1905

HMS Powerful was laid down at Vickers Barrow-in-Furness shipyard, on 10 March 1894, launched on 24 July 1895 (Chistened by Louisa Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire) and commissioned on 8 June 1897. Her first commander was Captain Hedworth Lambton, and the cruiser was assigned to the China Station. However she was delayed to prepare and participate in Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee parade, on 26 July 1895. Afterwards, she sailed, at full speed, making a run between Wei Hai Wai in China, and Yokohama in Japan by late July 1898. Her stokers mutinied however as the machinery space probably reached ungodly temperatures, but she arrived in port, and departed later to Port Arthur.

From the China Station to the Boar War

She spent the year 1896, 97 and 98 without incident in the China Station. In 1899, she was recalled home, via the short route through the Suez Canal, but later she was asked to round the southern tip of Africa, showing the flag amidst rising tensions with the Boers. Transiting via Hong Kong, on 17 September she arrived at Simonstown on 13 October. Since two days, the Second Boer War was already started, and Captain Lambton landed a half-battalion of the King’s Own Yorkshire from Mauritius.

HMS Terrible (Captain Percy Scott) arrived the following day and the latter provided improvized field carriages with navy 4.7-inch (120 mm) guns and 12-pounder guns. Lieutenant General George White, commander of the besieged forces at Ladysmith asked for artillery support, the cruisers happily provided. Meanwhile HMS Powerful also landed four guns to Durban, arriving on 29 November 1899. Captain Lambton there acquired two extra 12-pdr, sending a naval brigade to Ladysmith via trains. Once Ladysmith freed in late February, Powerful’s Marine brigade went back to Simontown on 12 March. Powerful left Simonstown for Portsmouth, arriving on 11 April.

The cruiser at her return was greeted after an article about the “heroes of Ladysmith” had an enormous impact, making Captain Lambton a household name. Queen Victoria sent a congratulation telegram, while the cruiser’s staff was welcome in a celebratory march and reception in London, also recorded on film. The naval brigade paraded also in front of Queen at Windsor Castle, on 2 May 1900.

Later career

HMS Powerful at Farm Cove, Sydney Harbour, 1908 (postcard)

HMS Powerful was paid off on 8 June 1900, at Portsmouth, for a long refit between 1902 and 1903. She received four extra 6-inch guns in casemates amidships (or on deck after other sources), had her rig simplified and other detail modifications. Recommissioned in August 1903 (under command of Captain Lionel Halsey) she was rushed to participate to the annual fleet manoeuvres. Afterwards she was reassigned to the reserve on 1 March 1905. The cruiser was later reassigned to Sir Wilmot Fawkes’s Australia Station, recommissioned as flagship, and she remained there until 1908.

By December 1905, HMS Powerful was based in Fremantle, Western Australia. She spent the year 1906 without incident, and by 10 October 1907 she headed for in Colombo, Ceylon, based there the remainder the year. On 3 February 1908 the cruiser took part in an experiment, the trans-Tasman radio transmission, from the Tasman Sea. In August she hosted a special correspondent to greet the visit of the sixteen USN Great White Fleet battleships. HMS Powerful departed with a new crew from Colombo on 12 January 1910 and in 1911 visited Auckland in New Zealand, Captain Edward Bruen advising for the buildup there of naval stores facility.

After being ordered home in January 1912, she carried the body of Alexander Duff, 1st Duke of Fife, embarked at Port Said in Egypt on her way on March, 9th. AAfter arrival, she was assigned to the 7th Cruiser Squadron, 3rd Reserve Fleet. She was afterwards reclassified as a Boys Training Ship, in Devonport, by August 1912, then she was debaptised, and reclassified as a tender, “HMS Impregnable” in 1913, and served that way until the end of WWI. She was still used for training from 23 September 1919 as “Impregnable I”, and the next decade, until paid off on 27 March 1929, sold for BU in August.

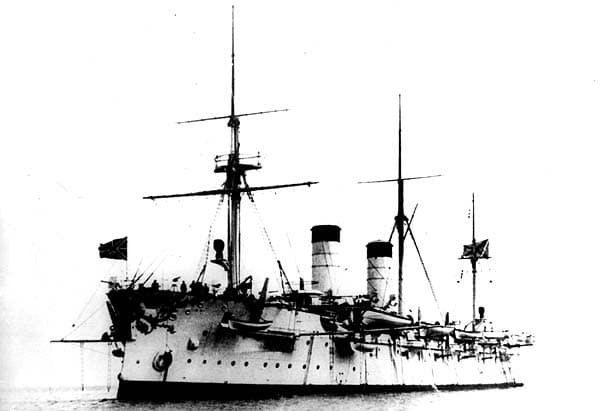

HMS Terrible

Cruiser HMS Powerful 1895 Location

HMS Terrible was built from 21 February 1894 at J. & G. Thomson Clydebank, launched on 27 May 1895 and fitted out at H. M. Dockyard in Portsmouth from 4 June, commissioned in July 1897 only to participate in the queen’s Diamond Jubilee parade, then returned to preparations until commissioned for actual active service, with Captain Charles Robinson in command, on 24 March 1898.

By May 1898, she ferried George Goschen, 1st Lord of the admiralty, and Austen Chamberlain, Civil Lord of the Admiralty, to Gibraltar and then Malta for inspection, also carrying relief crews for the Mediterranean Fleet. Underway, she was pushed full spead ahead, to establish a new record 2,206 nmi (4,086 km; 2,539 mi) in 121 hours in heavy weather, in the Bay of Biscay. The trip from Portsmouth to Gibraltar was made at 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph) on average, based on 12,500 ihp, and she made the trip from there to Malta at 21.5 knots (39.8 km/h; 24.7 mph), which were all records for the Royal Navy, as for any other Navy’s cruiser at the time.

On 13 March 1899, she suffered a boiler explosion when back to England. One stoker died, there others badly burned but survived and this led to an inquest poiting the finger at the use of salt water. The latter extensive corrosion and eventually reuined the boiler tubes, seven bursting due to overheating. This trigerred a serie of reforms for machinery management in the Royal Navy and better use of water, notably addition of distilling systems separating salt.

HMS Terrible at the Boer War

Captain Percy Scott became the new ships’s captain on 18 September 1899. He received orders to head for the China Station, however believing hostilities were close in South Africa, Captain Scott asked the Admiralty to go there via Cape of Good Hope, the long road, as did HMS Powerful later. HMS Terrible arrived at Simonstown on 14 October, before the war has broke, and Captain Scott soon found he could bring to land some of his naval guns, mounting on improvized wheeled mounts. Her wanted to support the army inland, lacking the range to provide artillery support. Army observers indeed complained about being out-ranged by the Boer’s own artillery.

Terrible’s ad hoc mounts proved in fact very effective and these 4.7-inch (120 mm) proved invaluable during the siege of Ladysmith. HMS Terrible then headed for Durban (6 November), her captain being appointed as Military Commandant, at the head of an improvized naval brigade, sent as Ladysmith relief force. They departed with two 4.7-inch and eighteen 12-pounder guns fro the cruiser, which proved very useful later at the battles of Colenso in December 1899 and Spion Kop in January 1900, and eventually the relief of Ladysmith, on 28 February. Scott even sent one of his small searchlights, mounted in a train to be used as a signal light, communicating with the besieged garrison. Terrible’s party came back to the cruisers as heroes, and Terrible departed Durban on 27 March 1900, this time for China, the other war.

Boxer Rebellion

HMS Terrible, 1st Class Cruiser Built at Barrow in Furness, 1897 Painting

HMS Terrible departed due north, crossed the Indian Ocean and arrived at Hong Kong, on 8 May 1900. Captain Scott immediately prepare to mount another landing party and asked to mount four 12-pounders on field carriages that were embarked at Durban. He also drilled the crew to perform well in marksmanship, knowing they would be inevitably ordered north, to Peking and the international delegation threatened by the Boxers.

On 15 June, Captain Scott was ordered to load three companies of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers, then sail to Taku forts (at the mouth of the Yangste). She arrived on the 21st and landed a single 12 pdr gun in support to the relief force; They reached Tientsin on 24 June. The other three guns prepared were landed for another expedition, defeating Chinese forces in Tientsin by mid-July, and from there, constituted the second relief expedition to Peking, arriving at last in August 1900. Terrible’s landing party participated in the liberation of the international quarters and returned to the cruiser once situation was clarified. They were back on 7 September.

Scott afterwards, drilled his crew hard to regular marine gunnery practice. He devised ingenious training aids, until his crew reached the very respectable score of 78.8% at the 1900 prize firing. Sent in Hong Kong on 17 December, Scott took part to form a relief party and salvage the capsized dredger Canton River. Two months later the operation was over, and the cruiser participated in another firing prize in 1901, reaching 80%, ending as great winners and best Royal Navy shots.

HMS Terrible 1895 at anchor

In early 1902 the cruiser participated in reconstructing Hong Kong, between relief and providing condensed water, help quelling an outbreak of cholera and water famine. In July 1902, Captain was ordered back home. The cruiser stopped in Colombo and Aden before reaching the Suez Canal, crossed the Mediterranean via Malta and Gibraltar, and back to Portsmouth (19 September). Although less famous than Powerful’s captain and crew -rather unfairly- as the events were now quite distant, 700 of her officers and men nevertheless were greeted in a public dinner in Portsmouth. The cruiser was paid off on 24 October before her refit in John Brown and Co. Clydebank dockyard, notably gaining four extra 6-inch guns. Back in full service on 24 June 1904 , she carried relief crews to the China Station by December.

Last service years

Paid off on 22 December, she was assigned to the reserve on 3 January 1905, but reaactivated in August to escort the HMS Renown, carrying the Prince and Princess of Wales during their tour of India, and back in 1906. HMS Terrible became flagship for the 6th Cruiser Squadron in their annual summer manoeuvres, and back to reserve, the reactivated on 7 November, to ferry relief again new crews to China. Underway back, she lost a propeller, but completed her trip with the remaining engine.

Refitted again in May 1908-April 1909 she joined the 4th Division, Home Fleet but was primarily used as an accommodation ship. On 6 December 1913 she was anchored at the Pembroke Dock, then listed for disposal in July 1914, until WWI started.

HMS Terrible was recommissioned in September 1915, to be used in her best possible role, as the “Royal Navy’s liner”, ferrying troops to the Dardanelles due to her large size and good speed. To make room, her main 9.2-inch guns were removed as the ammunitions. Off Mudros on 2 October she quickly departed home and arrived at Portsmouth, reaffected as a depot ship, then a tender to HMS Vernon (January 1918) and HMS Fisgard in 1919. By the end of this year, she was hulked, loosing all hopes of a possible military career: She was disarmed, her propulsion machinery almost entirely removed to make room for extra accomodations, as a training ship for engineering apprentices. This started in August 1920, under the new name of HMS Fisgard III.

She served as such for the interwar, until January 1932 when she was sold (in July) John Cashmore Ltd. and BU in Newport (Wales).

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign