Marine Nationale (1887-80), Protected cruiser, 1890-1910

Marine Nationale (1887-80), Protected cruiser, 1890-1910WW1 French Cruisers

Sfax | Tage | Amiral Cecille | D'Iberville class | Dunois class | Foudre | Davout | Suchet | Forbin class | Troude class | Alger class | Friant class | Linois class | Descartes class | D'Assas class | D’Entrecasteaux | Protet class | Guichen | Chateaurenault | Chateaurenault | D'Estrées class | Jurien de la Graviere | Lamotte-Picquet classDupuy de Lome | Amiral Charner class | Pothuau | Jeanne d'Arc | Gueydon class | Dupleix class | Gloire class | Gambetta class | Jules Michelet | Ernest Renan | Edgar Quinet class

Davout (After Napoleon’s Marshall) was a protected cruiser of completely new and modern type built between 1887 and 1890. It was ordered at the height of the “Jeune Ecole” influence over the Marine Nationale, under Admiral Théophile Aube as Minister of Marine. The latter preferred cruisers to battleships and wanted to develop torpedo carriers as well. Davout and very similar Suchet built almost at the same proceeded from the same design and to fill the role of a medium cruiser according to Aube. Davout was not masted like her predecessors, Sfax, Tage, and Cecille marking a true break in design. They were armed with a main battery of six 164 mm (6.5 in) guns in single mounts, and had a better top speed of 20.7 knots (38.3 km/h; 23.8 mph).

Davout had a relatively uneventful career, only entering service in 1893, but placed in the Reserve Squadron, Mediterranean Sea. Apart training exercises, after the major overhaul seeing the installation of new boilers, she was versed to the North Atlantic Station in 1902 and in 1910, was already struck, sold to ship breakers in 1913, a year before WWI broke out.

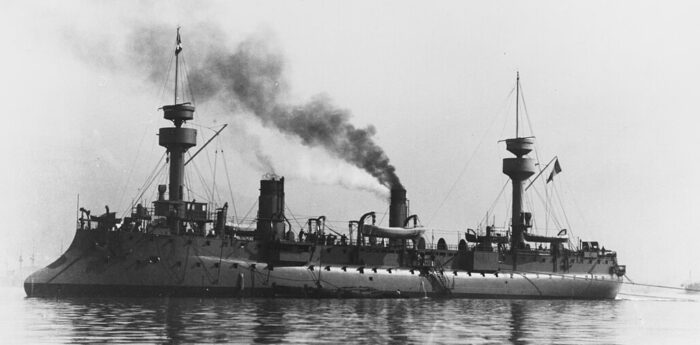

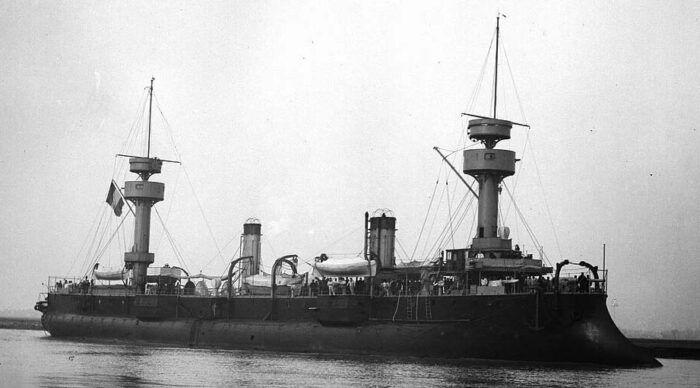

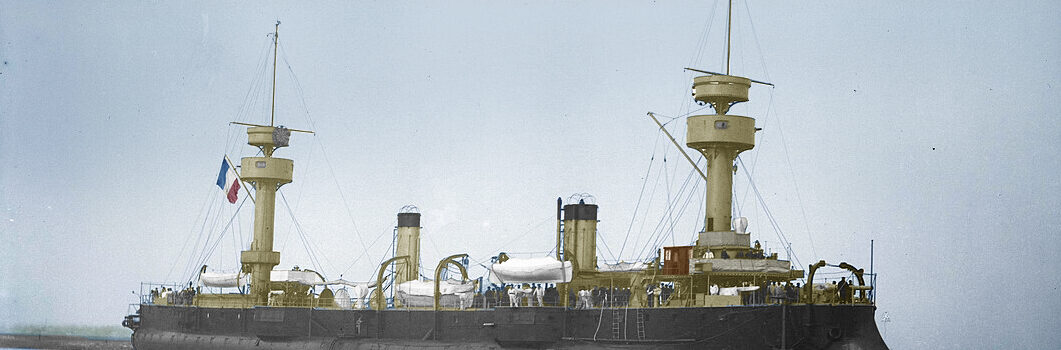

The French cruiser Davout photographed very early in her career, probably at Toulon. Note the clock indicator on the upper maintop of the after military mast. Its purpose is unknown but later devices of this nature were used to indicate the ship’s gun firing range of the ship’s firing angle off the bow. src history.navy.mil, unknown author, CC

Design of the class

Design Development

Davout was designed during the tenure of Admiral Théophile Aube, French Minister of Marine in 1886. However, it had its earlier origin in his predecessor Charles-Eugène Galiber by December 1885, which wrote the specification. At the time, Galiber wanted a 2,600 t (2,600 long tons; 2,900 short tons) cruiser capable of no less than 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph), with forced draft. Aube, which replaced Galiber in January 1886, soon gained a reputation of a disruptor in naval circle. Some would compare it to Admiral Fisher in some ways, but his influence was so deep and ingrained in the Marine Nationale for almost a decade, that it considerably changed it, and not for the best. Years later Boué de Lapeyrière called him “wrecker of navy”. His radical theories brought a lot of younger officers besides him, hence the “young school” moniker for his powerful faction. This post is not going to dive deep into the Jeune École doctrine, but let’s summarize it like a vision in which battleship were obsolete, and instead the Navy could defend France using a combination of cruisers and torpedo boats as well as attacking enemy merchant shipping. It was still in large part directed against Britain.

By the time Aube came to office, the French Navy just laid down three large protected cruisers we saw before, the Sfax, Tage, and Amiral Cécille. Aube’s budget thus was more ambitious as he called for another six, and ten smaller cruisers or avisos. He requested and reviewed no less than eleven designs, evaluated by the Conseil des Travaux (Council of Works). The design prepared by Marie Anne Louis de Bussy (1822-1903) was selected. De Bussy was a sailor and former polytechnician, St Cyr (mil. school) student as well, gradually recognized as a top engineer, which in 1885 Inspecteur Général du Génie Maritime (CNC) established plans for the cruisers “Forbin”, “Surcouf”, “Davout” and “Dupuy de Lôme”.

The most influence of Aube hd on the design, was to require a speed of 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph) in normal draught. Aube ordered three ships to that design, on 1 March 1887: These were the Davout, Suchet, and Chanzy. The contracts however were finalized after he left the ministry, under his successor Édouard Barbey.

Barbey wanted to reduce the program and by May 1887, when the new budget was approved, he ordered three large cruisers of the Alger class and six small cruisers of the Forbin and Troude classes as well as two more medium ships. Chanzy was cancelled, Davout and Suchet were recast as the two remaining medium ships. They were also now branded as prototypes for the smaller Friant class. Work went on plans for Suchet under the supervisor at Toulon, which decided to make alterations, so Davout kept the original design and remained single of her class. However Aube’s propulsion system intended for Davout was not going to meet the intended speed (it’s notably why Sucht was modified). These engines necessitated increases in displacement as well, asn all these changes had an impact on designing the Friant-class.

Hull and general design

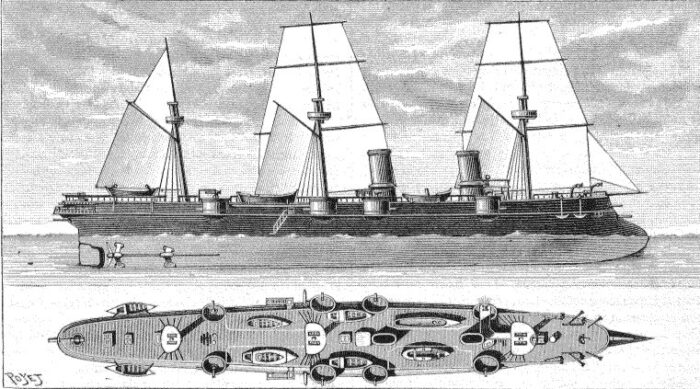

The initial, incorrect sketch by illustrator Poyet in 1890, should show two military masts. She never was completed with a rigging.

Davout ended as a 91.25 m (299 ft 5 in) long overall design, with a beam of 11.62 m (38 ft 1 in) and average draft of 4.65 m (15 ft 3 in). It could go up to 6 m (19 ft 8 in) aft when fully loaded. She displaced 3,330 t (3,280 long tons; 3,670 short tons) as well, less than the Cecille for example. Her hull had a better ratio for faster speeds, but she also featured a pronounced ram bow and overhanging stern, a pronounced tumble home, courtesy of Aube’s influence, and a flush deck. The bow was not strengthened for ramming attacks, however. The superstructure were kept minimal, with a conning tower and small bridge forward, then two heavy military masts with fighting tops housing light guns and spotting tops. Their crews amounted to 323 officers and enlisted men.

Powerplant

Davout was powered by two propellers (4 bladed), driven in turn by two inverted, 3-cylinder triple-expansion steam engines. Steam came from eight coal-fired fire-tube boilers. They were ducted into two widely spaced funnels amidships. This power plant had a total output as calculated of 8,950 indicated horsepower (6,670 kW), enough for reaching the contracted top speed of 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph). On her initial speed trials she reached 9,039 ihp (6,740 kW), so more than intended on force draft, and this allower her to reach only 20.07 knots (37.17 km/h; 23.10 mph) on light and perfect condition. This was barely above the contracted speed, so that the yard filled its obligations, but did not impressed, as when fully loaded in combat condition and heavily weather this speed was never to be reached by far.

Coal storage was of 477 t (469 long tons; 526 short tons) on a normal peacetime load, but there was enough internal space to reach up to 534 t (526 long tons; 589 short tons) in wartime and full load. This gave Davout a 7,130 nautical miles (13,200 km; 8,210 mi) range at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). But her main problem was the unreliablility of her propulsion system in service. Aube insisted on discarding the sailing rig, so she was the first French protected cruiser without it, but placed too great trust in the yard’s proposed machinery. The latter was delivered by Toulon Arsenal and its suppliers, but neither the boilers or their uptakes could be cleaned while steaming, and they were quickly clogged to the point a regular speed could not be kept after just a few days of operation. She was thus unable to perform long-distance cruises. This ensured she never was deployed on overseas stations.

Protection

Davout was protected by an armor deck made of mild steel:

Deck; 82 mm (3.2 in) thick flat section over the propulsion machinery spaces, magazines

Outer deck fore and aft: 30 mm (1.2 in).

Sloped sections, sides: 80 mm (3.1 in).

The deck was layered on 20 mm (0.79 in) hull plating.

Deck, flat section, 0.51 m (1 ft 8 in) above the waterline.

The sloped sides met the hull plating 1.09 m (3 ft 7 in) below the line.

Above the deck: Cofferdam to contain shell fragments, control flooding.

Main battery guns: 4 mm (0.16 in) gun shields (shell fragments).

Conning Tower: 70 mm (2.7 in)

Overall, the protection was a bit lighter than previous cruisers, also reflecting a smaller size.

Armament

She was armed still the same way as Cecille with quick firing medium guns as primary armament:

Six 165mm/30 M1884, then completed for torpedo boat defense by four 65mm/50 M1891, four 47mm/40 M1885, two 37mm/20 M1885, and six 350mm TT in a lozenge pattern. She had no secondary battery unlike Cecille.

Main battery:

Unlike Cecille which had eight, Davout only had six 164.7 mm (6.48 in) M1881 28-caliber, all placed on single pivot mounts. Four of the guns were mounted in sponsons on the upper deck, two on each broadside. One gun was placed in the bow and the other was at the stern as chase guns. There is no data on these models. Navweaps database starts with the M1891.

Light battery:

Since she completely lacked a secondary battery, close defense rests on an array of three calibers for her light artillery:

Four 65 mm (2.6 in) M1888 9-pounder guns in hull casemates fore and aft

Four 47 mm (1.9 in) M1885 40-cal. 3-pounder Hotchkiss guns. Probably located in the structures and decks fore and aft.

Eight 37 mm (1.5 in) M1885 20-cal. 1-pounder guns, all in individual mounts, covering each angle of the military masts’s fighting tops.

Torpedo Tubes:

Davout carried six 350 mm (13.8 in) torpedo tubes, in her hull above the waterline. This was in contrast to previous proetcted cruisers, which only had four, reflecting on the emphasis on torpedoes by Aube and his supporters. The lozenge plan was kept, but with two in the bow, one per broadside, two were in the stern. In general, a single tube was located at the bow or stern, denoting of a torpedo use that was more agressive in melee combat, as the Jeune Ecole theorized a closer combat due to the innacuracy on guns at the time at long range.

Modernization

Davout had a major refit between 1894 and 1896:

In 1894: Main battery guns replaced with quick-firing, same caliber.

In 1895: New armored conning tower fitted with 40 mm (1.6 in) sides and communication tube down. 4 mm gun shields replaced by 54 mm (2.1 in) shields. Heavy military masts replaced with lighter pole masts, elimination of the fighting tops to save weight and stability. 37 mm guns removed as well as the stern torpedo tubes.

1900: Second major overhaul: Removal of the bow torpedo tubes and four 37 mm guns. New Niclausse boilers installed and third funnel. Boilers now separated into three boiler rooms, the first had two boilers, the four. Unfortunately photos post-refit are hard to come by. None are open source.

Reference. src

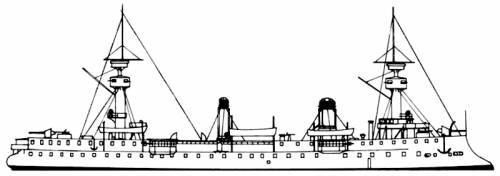

Conways profile of Davout.

⚙ Davout specifications |

|

| Displacement | 3,330 t (3,280 long tons; 3,670 short tons) |

| Dimensions | 91.25 x 11.62 x 4.65m (299 ft 5 in x 38 ft 1 in x 15 ft 3 in) |

| Propulsion | 2 shafts TE steam engines, 8 × fire-tube boilers: 9,000 ihp (6,700 kW) |

| Speed | 20.7 knots (38.3 km/h; 23.8 mph) on trials, 17-18 kts practical. |

| Range | |

| Armament | 6× 164 mm, 4× 65 mm, 4 × 47 mm, 2 × 37 mm, 6 × 350 mm TTs |

| Protection | Deck 51 to 102 mm (2 to 4 in), CT 71 mm (2.8 in) |

| Crew | 329 |

Career of Davout

The French cruiser probably photographed at Toulon at completion, prior to completion of fitting out for operational service. The ship is high in the water (light) and lacks certain fittings topside that can be seen in other early views of the ship.

Davout was ordered on 1 March 1887, at the Arsenal de Toulon, in southern France, with a keel laying on 12 September 1887, launching on 31 October 1889 and commission on 20 October 1890 bfore her sea trials. However they delayed due to grave issues with her propulsion system. The engines but also the boilers. Cracks were observed, vibrations were excessive, some parts assembly proved sub-par, ect. This required several repairs and alterations before each new attmpt at sea trials. In the end, the builder was constrained to braze boiler tubes, and they had to be redone anew in the end. The pistons were also replaced. This postponed her final completed in 1892, and full commission on 20 September that same year.

She joined the Mediterranean Squadron in Toulon. In 1893 she was transferred to the Reserve Squadron, six months on active service, fully crewed, for maneuvers. The next six months she was mothballed with a maintenance crew. That reserve also included several older ironclads plus the cruisers Tage, Sfax, Forbin, and Condor. In 1894, she sailed north, on th e west coast for a refit at Rochefort, ordered on 20 March, started on 21 July, completed on 20 February 1895. She returned for the fleet maneuvers from 1 July to the 27th as part of “Fleet B”, teaming with “Fleet A” (French Navy) against a third, hostile “Fleet C” impersonating the Italian fleet. She was back at Rochefort for more refits.

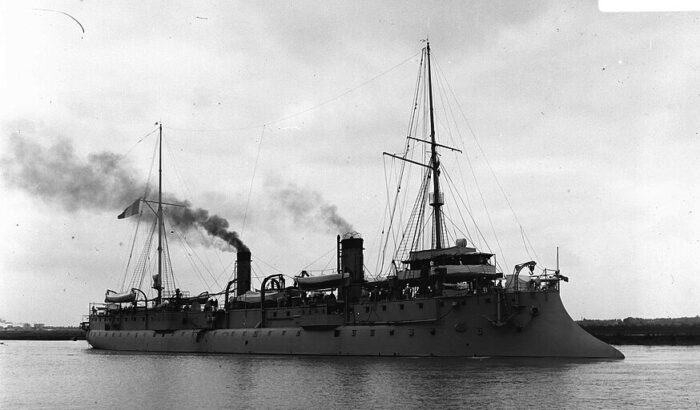

Date unknown, early in her career. src “Memory of Men”, cultural portal of the Ministry of the Armed Forces with inventory number MR 5 G 159.

Davout post 1895 refit showing her pole masts and cut down structures to regain stability after a gun change. The new QF were heavier. Same source as above, CC

In 1896, she was reduced to the 2nd category reserve, with old defense ships and ironclads, but retained in a state that allowing quick mobilization in case of war.

The main reason was also her numerous shortcomings, notably her machinery problems had never been cured properly. She was withdrawn from service for a lengthy reconstruction in 1897, starting with the projected installation of new Niclausse-type water-tube boilers, but this was cancelled. In 1898, she entered the training squadron with Amiral Charner and Friant. In January 1899 she was back in the reserve fleet but recommissioned on 1 April and returning to the training squadron. She followed it to Brest by late September, dispersed and deactivated for the winter. She then was sent again to Rochefort to be laid up on 1 October for her delayed re-boilering, carried out between August and December 1900.

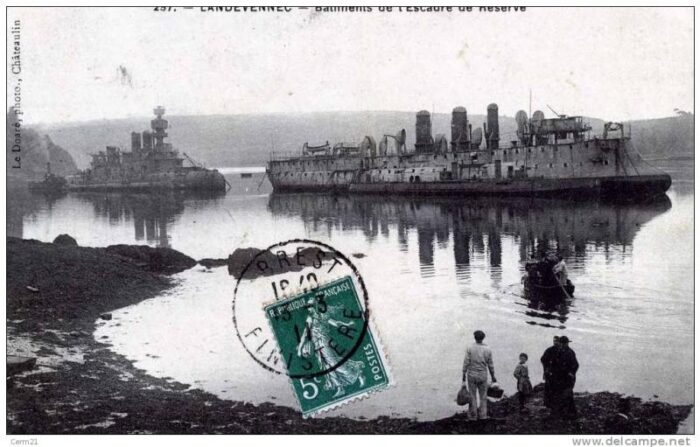

Davout in Brest, later in her career, but before her 1900 reboilering.

Fully reactivated in 1902 she replaced her near sister Suchet on the North Atlantic station. She had torpedo tubes removed during that time. She was decommissioned for the last time on 1 May 1909, reassigned as a training ship for boiler room crews on 27 May, based in Brest. She was towed on 16 August, anchored in Landévennec outside of Brest, the traditional protected bay used to store mothballed French warships to this day. She remained there until struck from the naval register on 9 March 1910. She still stayed there until sold to ship breakers on 23 October 1913 and broken up in Brest, never seeing the start of WWI.

Read More/Src

Books

Brassey, Thomas A. (1893). “Chapter IV: Relative Strength”. The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co

Brassey, Thomas A. (1899). “Chapter III: Comparative Strength”. The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.

Brassey, Thomas A. (1902). “The Fleet on Foreign Stations”. The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.

Thursfield, J. R. (1892). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). “Foreign Naval Manoeuvres”. The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.

Thursfield, J. R. (1897). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). “Naval Manoeuvres in 1896”. The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.

Weyl, E. (1896). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). “Chapter IV: The French Navy”. The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.

Campbell, N. J. M. (1979). “France”. In Gardiner, Robert (ed.). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1860–1905.

Clowes, W. Laird (1894). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). “Toulon and the French Fleet in the Mediterranean”. The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.

Gleig, Charles (1896). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). “Chapter XII: French Naval Manoeuvres”. The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.

Jordan, John & Caresse, Philippe (2017). French Battleships of World War One. NIP

Leyland, John (1900). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). “Chapter III: Comparative Strength”. The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.

Roberts, Stephen (2021). French Warships in the Age of Steam 1859–1914. Barnsley: Seaforth.

Ropp, Theodore (1987). Roberts, Stephen S. (ed.). The Development of a Modern Navy: French Naval Policy, 1871–1904. NIP

“Ships: France”. Journal of the American Society of Naval Engineers. III.

Links

https://www.navypedia.org/ships/france/fr_cr_davout.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_cruiser_Davout

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Davout_(ship,_1889)

https://threedecks.org/index.php?display_type=show_crewman&id=24445

http://dreadnoughtproject.org/French%20Warship%20Plans/

https://www.secretprojects.co.uk/threads/french-never-build-and-preliminary-designs-since-1880.41079/

Model Kits

None, want one ?

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign