Marine Nationale Protected cruiser, 1887-1906

Marine Nationale Protected cruiser, 1887-1906WW1 French Cruisers

Sfax | Tage | Amiral Cecille | D'Iberville class | Dunois class | Foudre | Davout | Suchet | Forbin class | Troude class | Alger class | Friant class | Linois class | Descartes class | D'Assas class | D’Entrecasteaux | Protet class | Guichen | Chateaurenault | Chateaurenault | D'Estrées class | Jurien de la Graviere | Lamotte-Picquet classDupuy de Lome | Amiral Charner class | Pothuau | Jeanne d'Arc | Gueydon class | Dupleix class | Gloire class | Gambetta class | Jules Michelet | Ernest Renan | Edgar Quinet class

Sfax was the first Protected Cruiser of the French Marine Nationale, a topic opening a new cycle with 19 ships and classes to cover until the dreadnought age. She was a masted cruiser designed for stations in the French colonial Empire, bearing many of the trademarks of French constructions at the time. She was well armed for her modest dimensions, not even reaching 4,600 tonnes, had a ram bow and classic tumble home, but she was slow. She alternated between the Mediterranean, Northern, and Reserve Squadrons with training exercises and part year-commission. Likewise, she served at the North American station in 1899 and was reduced to permanent reserve in 1901, and sold in 1906.

Protected Cruisers

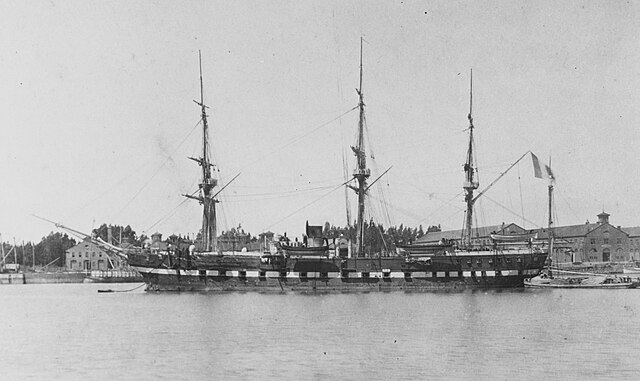

French was not new to cruisers. The concept and name were already adopted in the 1870s, after series of Frigates since 1850, the converted Armorique class, Cosmao, Taliman, Résolue, Vénus, the next were called “croiseurs de 2e classe” such as the Decres, Desaix, Limier, Chateurenault, Linois , Infernet, Sané, Bourayne, Hirondelle, Rigault de Genouilly class. They were typical distant station unprotected cruisers. The first large ship that was already closer to an actual “cruiser” in an international comparison, was Duguay-Trouin in 1877. With Duquesne and Tourville they formed a class of well-rigged 5000t 1st class near-sister ships that could potentially deter any gunboat or light cruisers in French colonial waters. Next were series of smaller 2nd class vessels, which brings us up to the Milan launched in 1884. She really was the forerunner of French protected cruisers, with a pronounced ram bow, greater speed (18.5 knots vs. 13.9 on the 1884 Dubourdieu) and reduced rig. She was as much as an early scout cruiser as well.

Sfax however was closer to the tradition of Dubourdieu, a classic masted cruiser, but integrated a turtle deck armor at the waterline, which was a brand new concept for the French Navy, years before the first armoured cruisers. Indeed, the idea of placing armour on a cruiser was largely the result of the 1870s increasing power of armour-piercing shells. Even ironclads had troubles with these and needed very thick, heavy armour plates and many thought the next generation of shells would be able to pierce these. Frigates and early cruisers or “aviso” and assimilated vessels were easy preys for these new shells as well. They needed long endurance, large consumable supplies, large high-speed machinery. Little weight was left available for any armour protection. Their sides would remain vulnerable, but others argued that a “minimal armour” could be installed and optimized and installed just below the waterline. The idea this protection would be met above water, very obliquely by shells, and so needed to be just a fraction of a heavy belt armour. This protection would be basically created above the engines, boilers and magazines, with hopefully enough reserve buoyancy to keep a cruiser afloat even if riddled above water.

The very first armoured deck was experimented on HMS Shannon (1875), which however still had a primary vertical belt armour while her protective deck was partial, creating a citadel. In fact, Shannon was classed as an armoured cruiser instead. The very first ships with only an armoured deck as main protection were the British Comus class corvettes laid down in 1876, and again, it was partial and mostly covered the machinery spaces. These slow vessels were designed for distant stations. The next Satellite and Calypso classes followed that concept.

The very first armoured deck was experimented on HMS Shannon (1875), which however still had a primary vertical belt armour while her protective deck was partial, creating a citadel. In fact, Shannon was classed as an armoured cruiser instead. The very first ships with only an armoured deck as main protection were the British Comus class corvettes laid down in 1876, and again, it was partial and mostly covered the machinery spaces. These slow vessels were designed for distant stations. The next Satellite and Calypso classes followed that concept.

Thus, in 1879 already this started discussions in the French admiralty. In 1880 were ordered in Britain the Leander-class cruisers, this time defined as true “protected cruisers” with a full armoured deck. Ordered in 1880, the French admiralty choosing the right kind of cruiser to sport such protection took more time to define, albeit all agreed it would be for distant stations.

The French Dubourdieu

The French Milan

Sfax’s construction was decided upon in 1881 and her plans were ready and approved, the construction voted FY1882, contract awarded to Brest Arsenal (Arsenal de Brest). She was named after an important colonial city, Sfax in Morocco, and also named after the Bombardment of Sfax during the recent, French conquest of Tunisia in 1881 by the Third Republic. She integrated aspects from both the Milan and Dubourdieu, trying to reach a satisfying mix, being faster than Dubourdieu but with the same range, and better armed, whereas integrating many concepts from the Milan hull, notably a tumble home, ram bow, overhanging stern.

Design of the class

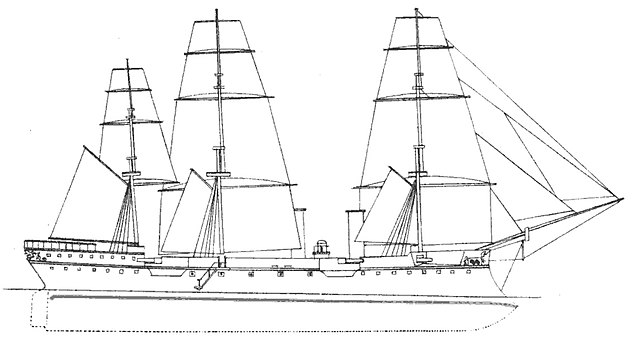

Drawing showing her full rig in 1887 (Brasseys naval annual)

Design Development

Unlike the earlier French Cruisers, Sfax carried an armor deck covered her propulsion machinery and ammunition magazines and was almost integral. Given the ideas of the Jeune Ecole at the time she was conceived as a commerce raider in the event of war with Great Britain but also rigged as a barque to supplement her engines for her distant stations, preying on British distant lines of communications. She was well armed in general, and this was revised later in her career. The design was worked out by French naval engineer Louis-Émile Bertin, which already prepared in 1870 a new type of ironclad river monitors with a highly subdivided watertight compartments and later Bertin suggested a similar feature on 1872 cruisers (rejected in 1873).

But the 1878 French Navy cruiser program authorized by the Conseil des Travaux (Council of Works) for a strategy to attack British merchant shipping in wartime. In peacetime, these cruisers would free more important units in distant stations. The program called for 3,000 long tons (3,048 t), 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph) cruisers, and led to design initially the unprotected Naïade, Aréthuse, and Dubourdieu, all masted and with wooden hulls. But Milan was remarked with her absence of masts, great speed and steel-hulled design so a fifth ship was initially ordered to Dubourdieu as “Capitaine Lucas” but the Royal Navy announcement of the construction of its Leander class might change these plans. The Navy proceeded anyway.

The Director of Materiel in charge of the construction of Capt. Lucas was Victorin Sabattier. However he temporarily vacated his position in 1881 due to illness. Bertin protested about the nex design, given what was done in the Royal Navy and managed to convince Alfred Lebelin de Dionne which took over the job, to adopt instead his 1873 proposal. Lebeling then managed in turn to convince the Minister of the Navy, Georges Charles Cloué to stop construction of Capt. Lucas in favor of Bertin’s new proposal, which went through a serie of improvements suggested by the Council of Works. But this process to time. In between ordered in 1882, under the new Navy minister Auguste Gougeard and renamed Sfax after a recent victory, the new experimental cruiser was ordered at Brest, Britanny, NW France.

Hull and general design

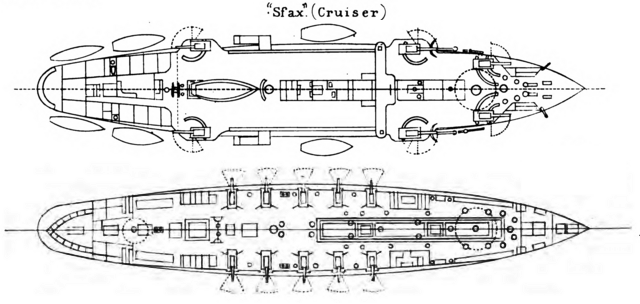

From Brasseys 1887

Sfax was surely a large ship, the largest cruiser in the French Navy so far, at 90.03 m (295 ft 4 in) long at the waterline, 91.56 m (300 ft 5 in) long between perpendiculars, 96.08 m (315 ft 3 in) long overall at the tip of her bowsprit. The beam was still 15 m (49 ft 3 in); but already reduced at deck level compared to the waterline to try to regain stability, another Bertin’s idea. Her average draft was 6.77 m (22 ft 3 in) forward, up to 7.65 m (25.1 ft) aft. Her designed displacement was 4,561 t (4,489 long tons). But as usual, calculations and execution diverged (notably due to design additions) and final displacement was 4,888 t (4,811 long tons) as completed, which pushed the waterline a bit lower, and so the armour.

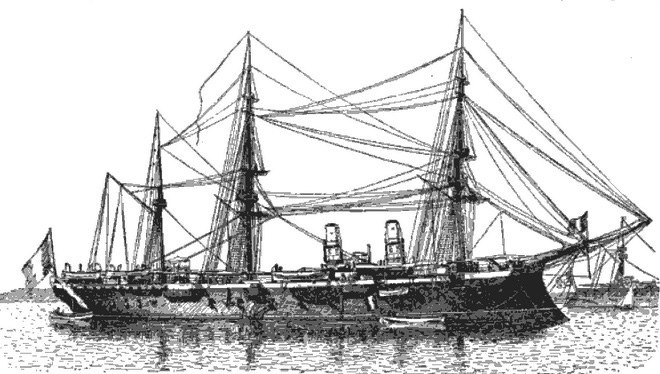

Like Milan, she feartured and all-iron hull, wrought irn plating bolted on steel frames. Being a colonial cruiser, she was also sheated and coppered to protect her hull from biofouling on extended cruises, layered on timber backing. She featured a pronounced ram bow, reinforced for efective rammings, but also had short fore and sterncastles. Berting added to the design his typical cofferdam above the waterline, with an earl cellular layer between the armour and main deck. Her pronounced tumblehome shape ended in a clipper-like overhanging stern in which resided the officers. Her superstructure was barebones, with a small conning tower forward and a wooden cabin, over which was located the main bridge betwene funnels. Her crew comprised 470 officers and enlisted men and she had nine boats, including six under davits aft and amidships.

Powerplant

Sfax was powered by two propeller shafts with 4-bladed screws. They were driven by horizontal, 2-cylinder compound steam engines, fed by steam produced by twelve coal-burning fire-tube boilers, ducted into two funnels amidships. As designed she was also fitted with a generous barque sailing rig, on three masts. Total sail area was 1,990 square meters (21,400 sq ft) so she could proceed on sail power alone, but this was imposed upon Bertin’s wishes, and the hull was not well oprtimised for it, notably the ram bow. As a result she proved to perform poorly under sail. Steering was controlled with a single rudder.

Her twin engine power, like Milan, was supposed to gave her a much better speed than traditional masted crusiers, despite the added armour. Her poweplant was rated for 7,680 indicated horsepower (5,730 kW) as contracted, at 90 revolutions per minute, which was traduced by a top speed of 16 knots (30 km/h; 18 mph). But on trials by May 1887, on light load, her machinery could only reach 6,495 ihp (4,843 kW), and yet was sitll capable of reaching top speed of 16.71 knots (30.95 km/h; 19.23 mph), but on forced draft.

In fact she was in the end much slower in service due to excessive vibration at speeds above 13 knots (24 km/h; 15 mph) and the engine was not pushed forward of 65 rpm, 30% less than the output nominal figure. In practice she was limited to just 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph), barely better than the Dubourdieu class and negatng her commerce raiding pretenses. Coal storage was 710 t (700 long tons) at normal load, but by filling all void cmpartments aboard, this could rise to 1,000 t (980 long tons) at full load in wartime. Her cruising range was thus around 4,200 nautical miles (7,800 km; 4,800 mi) at just 10.5 knots (19.4 km/h; 12.1 mph).

Protection

Sfax was fitted with an armor deck made of wrought iron plating, 30 mm (1.2 in) thick and layered on 10 m (33 ft) of deck plating. It was 0.6-0.9m (2-3 ft) initially below water and was 60 mm (2.3 inches) thick in four layers of steel. Bertin wanted to push it to 38 mm (1.5 in) thick but the design was judged already top heavy and this was reduced to save weight and instead strengthen deck supports. This armor deck was low in the ship at 0.75 m (2 ft 6 in), aggravated by the extra displacement after delivery. In theory a plunging shell was already braked by the density of water before hitting the thin belt. This was a “turtleback” arrangement below the waterline, with downward sloping sides tapered down to 28 mm (1.1 in).

Between the armor and main deck Bertin’s signature cofferdam was added to watertight compartmentalization and ensure to contain any flooding. This section between the armour and main deck comprised no less than seven longitudinal and sixteen transverse bulkheads. Many of these cells were fill with water-absorbing cellulose. Others were used to store extra coal.

The only armoured partr of the ship was her unique conning tower between funnels, with 30 mm walls.

The 164.7 mm guns were also protected by 8 mm (0.31 in) sponsons walls and had lighter shields that could stop shrapnel for those on deck.

Armament

Main battery:

Six 164.7 mm (6.48 in) M1881 28-caliber on single pivot mounts. Four mounted in sponsons, upper deck, two the broadsides, remaining two were placed in embrasures, in the forecastle.

Secondary battery: Ten 138.6 mm (5.46 in) M1881, 30-caliber guns, at the main deck battery amidships.

Anti-torpedo boat battery: She sported eight 37 mm (1.5 in) guns in single pivot mounts, partly in the fighting tops, the rest on the bridge’s wings and upper deck posts fore and aft.

Torpedoes:

She carried five 356 mm (14 in) torpedo tubes above waterline: Two forward, two broadside, one in the stern.

Undercarriage guns: She also had two extra 65 mm (2.6 in) M1881 field guns to be used for a landing party.

Modernization

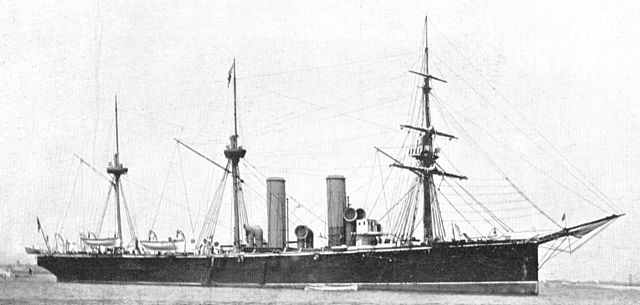

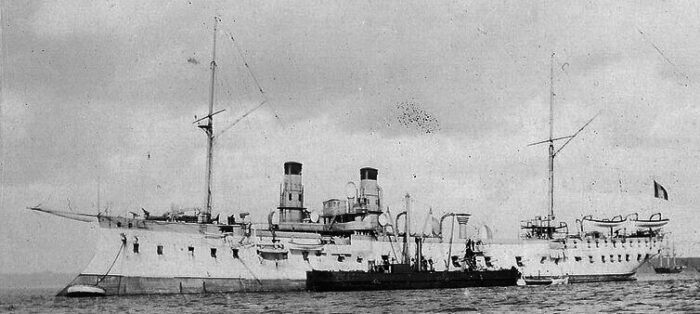

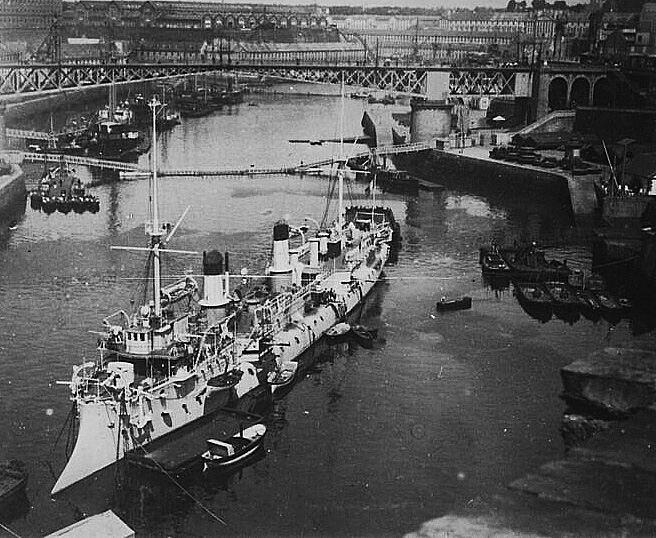

Sfax as modernized in 1899, Brest, Northern Sqn.

Sfax experienced several cycles of refits and modernizations:

In 1888-89 her unsatisfactory sailing rig was modified from a barque to a schooner rig. She also had new propeller screws fitted in October 1888 trying to address her vibration issues, but this failed and they were reverted to their former propellers by February 1889.

In 1892, her bowsprit was replaced with a lighter jibboom.

From March 1893 and May 1894 she had her most comprehensive overhaul: Main and secondary battery were replaced with 30-cal. M1881 162 and 138 mm quick-firing guns. Also her six 5-tubes 37mm/20 autcannons were removed as well as three of her torpedo tubes, one in the bow and two in her beam.

Her sailing rig was removed entirely and the bases replaced by military masts and some of the light guns placed in new fighting tops.

Her last refit was between August 1897 and August 1898:

Her original boilers were replaced by Indret fire-tube boilers. Her three military masts were removed and replaced by only a fore and mizzen pole mast. The base of the main mast was converted into a ventilation shaft. Her light armament comprised six 47 mm (1.9 in) M1885 QF guns as well as four 37 mm QF guns and six 37 mm revolvers, the latter being fitted in reinforced fighting tops and the remainder edistributed along the upper deck. She still had her vintage 65 mm landing guns. She however had but her broadside torpedo tubes removed.

⚙ Sfax specifications |

|

| Displacement | 4,888 t (4,811 long tons) |

| Dimensions | 96.08 x 15 x 6.77 m (315 ft 3 in x 49 ft 3 in x 22 ft 3 in) |

| Propulsion | 2 shafts compound steam engines, 12 × fire-tube boilers: 6,495 ihp (4,843 kW) |

| Speed | 16.71 knots (30.95 km/h; 19.23 mph) |

| Range | 4,200 nmi (7,800 km; 4,800 mi) at 10.5 kn (19.4 km/h; 12.1 mph) |

| Armament | 6× 164 mm, 10 × 138 mm, 8 × 37 mm, 5 × 356 mm TTs |

| Protection | Deck 30 mm (1.2 in), CT 30 mm, sponsons 8 mm (0.31 in) |

| Crew | 470 |

Career of Sfax

Sfax with her rig modified in 1889

Sfax was laid down at the Arsenal de Brest on 26 July 1882, launched on 26 May 1884, fitted-out work from 10 October 1885 to 1 September 1886. She was only commissioned for sea trials on 17 January 1887 off Brest, until 7 June, then accepted in full commission. Just eight days she left Brest for Toulon, the main Mediterranean base. She took part in fleet maneuvers from 11 June and was placed in reserve for the remainder of the year.

In 1890, Sfax was transferred to the Northern Squadron from Brest, facing the English Channel. She took part in naval maneuvers alongside the ironclads Marengo, Océan, and Suffren as the scout cruiser Epervier from 2 July in a scneario of amphbious assault from the east, likely a German squadron, concluded on the 5th. She took part in Joint Mediterranean/Northern Sqn. maneuvers in 1891 also from 2 July and until the 25th, then was placed again in reserve.

In 1892, Sfax was transferred to the Mediterranean with the reconnaissance force, battle fleet, despite her limited speed. She served along with the cruisers Tage, Amiral Cécille, and Lalande. Fleet maneuvers went on from 23 June to 11 July. In 1893 she was placed in the Reserve Squadron, six months active and training her crews, then laid up the other six with a reduced crew. She served alongside the Tage, Davout, Forbin, and Condor. She was refitted also in Marseille and took part in large exercises by 1894. On 9-16 July off Toulon she had intensive shooting practice and wa spart of a blockade simulation, and scouting operations, western Mediterranean, until 3 August.

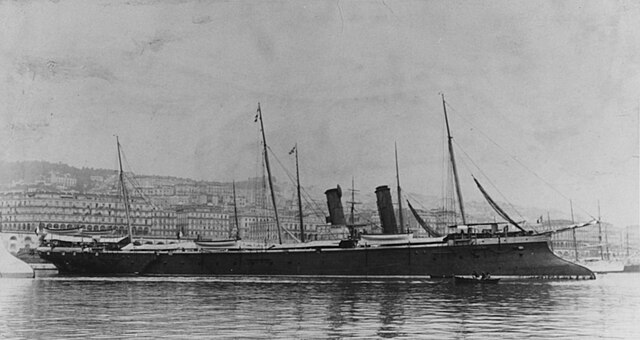

Sfax as modernized 1895

By late January 1895 she took part with the barbette ironclad Amiral Duperré to an experimental bombardment of a simulated coastal fortification, on Levant Island over six hours each day for three days. Thuis showed an intensive bombardment could cause some guns to fail, and she had a few casulaties from shell fragments. This was instructive in any cases and urged the use of longer range guns. Sfax served with Forbin and Milan during the remainder of this year’s fleet maneuvers on 1-27 July as part of “Fleet A”, tasked with defeating the hostile “Fleet C” standing for the Regia Marina.

She was in reserve in 1896 but took part sill in annual maneuvers (Reserve Squadron, with Lalande, Amiral Cécille, Milan, and Léger) on 6-30 July. By mid-1897, she was reactivated for combined exercises with the Northern Squadron from 18 to 21 July. Sfax and Tage simulated a hostile fleet coming from the Mediterranean to attack communications lines off the Atlantic coast. They were successfully intercepted by the Northern Squadron.

Sfax in Brest 1899

Sfax after her last modernization in 1889-99 at Brest was recommissioned and assigned to the North American station, with the new old Dubourdieu, relieving the equally old Rigault de Genouilly. Meanwhile France had been rocked by a political scandal, the Dreyfus affair. When Alfred Dreyfus was pardoned, Sfax brought back from Devil’s Island (French Guiana) to Port Haliguen. By January 1901 she was in the 2nd category reserve. From 20 January 1903, she wa sin the special reserve, seeing no further service and having a reduced skeleton crew. She was formally decommissioned on 13 August 1905, stricken from the register in 1906, but used as a storage hulk, for shells and propellant charges, from 1906 to 1909. She was eventually sold on 26 May 1909, the sale concluded on 25 August 1910, after which she was borken up, making her missing the balkan wars of 1911-1913.

Read More/Src

Books

Barry, E. B. (1895). “The Naval Manoeuvres of 1894”. Philadelphia: L. R. Hamersly & Co

Brassey, Thomas, ed. (1886). “Sfax”. The Naval Annual. Portsmouth: J. Griffin & Co.: 239.

Campbell, N. J. M. (1979). “France”. In Gardiner, Robert (ed.). Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1860–1905.

Gleig, Charles (1896). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). “Chapter XII: French Naval Manoeuvres”. Naval Annual. J. Griffin & Co.

Jordan, John & Caresse, Philippe (2017). French Battleships of World War One. NIP

Lansdale, Philip V. & Everhart, Lay H. (July 1896). “Notes on Ordnance and Armor”. ONI.

“Naval Notes: France”. Journal of the Royal United Service Institution. XLII (247). J. J. Keliher & Co.

“Notes on Ships and Torpedo Boats”. Notes on Naval Progress, January 1898. Government Printing Office.

Roberts, Stephen (2021). French Warships in the Age of Steam 1859–1914. Barnsley: Seaforth..

Ropp, Theodore (1987). Roberts, Stephen S. (ed.). The Development of a Modern Navy: French Naval Policy, 1871–1904. NIP

Thursfield, J. R. (1898). Brassey, Thomas A. (ed.). “II: French Naval Manoeuvres”. Naval Annual. J. Griffin & Co.

Links

on navypedia.org/

on scientificamerican.com/

on laststandonzombieisland.com

on battleships-cruisers.co.uk/

on wikiwand.com List protected cruisers France

on history.navy.mil/

on en.wikipedia.org/

colorized photo on deviantart.com/

Model Kits

None, want one ? Contact me.

Videos

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign