WW1 Italian Battleships

Kingdom of Italy (1886-1916) 20 battleships

Kingdom of Italy (1886-1916) 20 battleships

Foreworld about ww1 Italian Battleships

Italy started WWI with 16 battleships, several dreadnoughts in completion, construction, or planned. Recoignised as a major naval power in the Mediterranean, the fact it choosed eventually the side of the entente was crucially important for Britain and France to secure access to their colonies. Italy did not lacked talented engineers and a solid industrial basis in the north to fulfill its capital ship procurements in full autonomy.

The process started already in the 1860s with an Ironclads race, notably to face Austria-Hungary. From the lessons of Lissa, Italian engineers and the admiralty board devised new ships, some surprisingly powerful and using unique designs to gain supremacy in the Mediterranean. In 1880 for example, Italy unveiled two ironclads fitted with 100-ton 450 mm calibre muzzle-loading guns, making them the most powerful warships afloat. Italian engineers were also the first to test the waters of fast battleships (as pre-dreadnoughts !) and V. Cuniberti famously pioneered the idea of the monocaliber ship.

This post is best seen in conjunction with WW2 italian Interwar Battleships

Ships of the origins: Italian Ironclads (1860s)

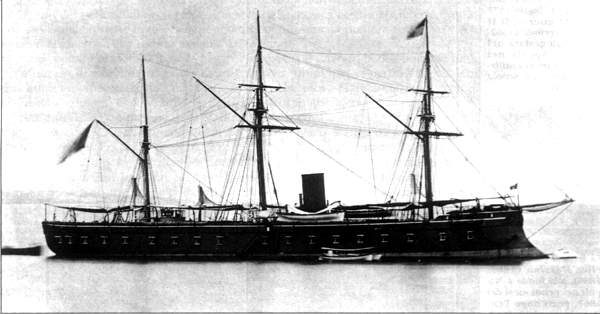

Italy was not long to adopt ironclads. It happened during its unification, arguably a long process but solidified as a consequence of the Second Italian Independence War of 1859. Even before the Regia Marina was created in 1861, two ships were ordered in France in 1860 and laid down in June and December 1860: The Formidabile-class. Rather small ships, they were followed by the Principe di Carignano class, Principe di Carignano (1863), Messina (1864) and Conte Verde (1867), built this time in Italy, the Re d’Italia class (Re d’Italia (1863), Re di Portogallo (1863) built in UK, the Regina Maria Pia class (Regina Maria Pia (1863), San Martino (1863), Castelfidardo (1863), Ancona (1863) again built in France. Most of these were ready to fight the Austrians, after a considerable effort translated into the battle of Lissa in 1866.

The Roma class (Roma (1865), Venezia (1869)) and the delayed the Conte Verde (1867) of the Principe di Carignano class, integrated world’s naval innovations at the time but still not those of Lissa. The Roma class however were the first Italian central battery ships, integrating the latest technology by Insp. Eng. Giuseppe De Luca, which designed them at first as regular broadside ironclads but later changed the design. De Luca later worked on the Principe Amedeo class (Principe Amedeo, Palestro (1871)).

The transitional ship was the Affondatore, a 1865 turret ram which missed Lissa by a few hours and was modernized two times until decomm. in 1907, then depot ship in WWI. The first and last centra Battery ironclads of the Italian Navy were the two Principe Amedeo class (1871) designed by Guiseppe de Luca and the first to be entirely built and completed in Italy, over nine to ten years:Laid down in 1865 they were completed in 1874-75. They survived until 1902-1910 in a mastless, modernized form. For details, return to check the (future) Italian Navy 1870 & Italian Navy 1890 for a more detailed review with specs.

No ship was laid down from 1865, in the rush of the war with Austro-Hungary, and 1873, this time with steam-only turret ships, in three series: 1873, 1876 and 1881.

Italian Barbette ironclads

Duilio class (1876)

Caio Duilio, Dandolo

A concentrate of innovations: Caio Duilio was the lead ship of the namesake class of ironclad turret ships, built for the Italian Regia Marina in the 1870s. The name recalled Roman Admiral Gaius Duilius. The Duilio was started in January 1873, launched in May 1876, and completed in January 1880. The class also comprised the Dandolo, and both replaced the sail and steam Principe Amedeo-class ironclads (1865), both missed the battle of Lissa. The Duilio class was designed by Cuniberti, and the first Italian steam-only ones. Strategically, they fitted with Italy’s large naval expansion program pitted against Austria, compounded by new possibilities offered by the opening of Suez Canal in 1869.

Italia class (1880)

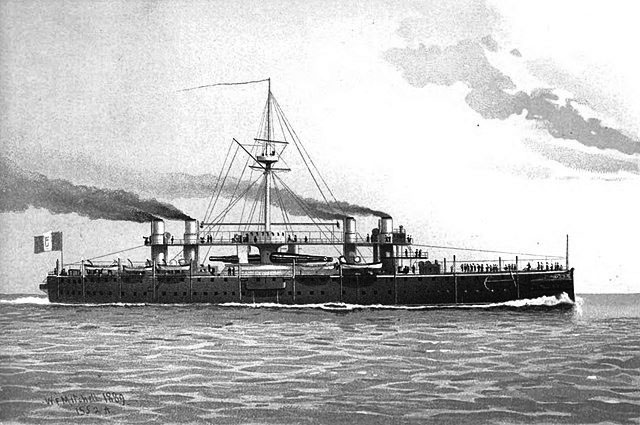

Italia, Lepanto

The Italia class comprised two ironclad battleships of the Regia Marina, built between the late 1870s and early 1880s. They were designed by famous engineer Benedetto Brin, which took a radical approach on protection design to profit overall speed, with an exceptionally extensive internal subdivision. Combined with their very large 17-inch (432 mm) guns, they were quite singular vessels which soon attracted the attention of admiralties around the world, notably the Royal Navy, and are now considered “proto-battlecruisers” my many specialists.

They however only served for about thirty years, and had uneventful careers. In the Reserve Squadrons for the last decade they served as training maneuver ships, Lepanto being fully converted into a training ship in 1902 and was discarded in 1915. Italia was modernized in 1905–1908, but also becoming a training ship. They briefly saw action in the Italo-Turkish War of 1911-12 off Tripoli. Italia was still active as a guard ship during World War I, but converted into a grain transport in 1917.

Ruggero di Lauria class (1884)

Ruggiero di Lauria, Francesco Morosini, Andrea Doria

The Ruggiero di Lauria class were the next ironclad battleships built for the Regia Marina and a return to the more reasonable Duilio class, as essentially improved versions, with new, lighter and faster breech-loading guns, better armor protection, more powerful machinery. They were designed by Giuseppe Micheli, which criticized Benedetto Brin, making a difference here.

Construction however was very slow, and if it started in 1881, they were completed ten years after, at the time the first pre-dreadnought battleships were built by all nations. Obsolescent, they saw little service, spending time alternating between Active and Reserve Squadrons, and conducting training exercises. They were removed from service after 18 years, in 1909 and up to 1911.

Francesco Morosini ended as target ship, Ruggiero di Lauria became a floating oil tank, Andrea Doria a depot ship, in service during World War I. Andrea Doria was even re-enlisted as local guard ship and then returned to her oil storage duties after 1918, BU in 1929. Ruggiero di Lauria survived until …1943 as a depot ship, sunk by allied bombers and her wreck was salvaged in 1945 for BU.

Italian Pre-dreanoughts Battleships

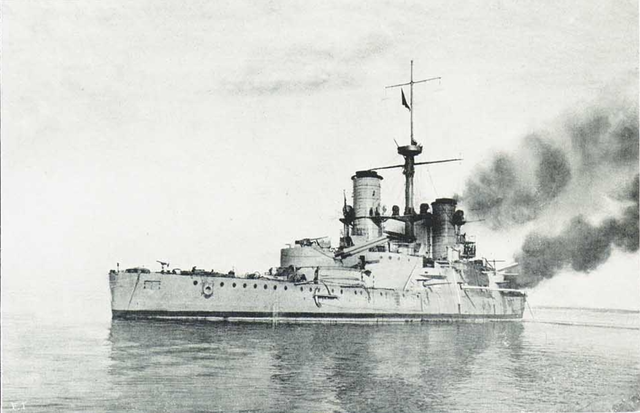

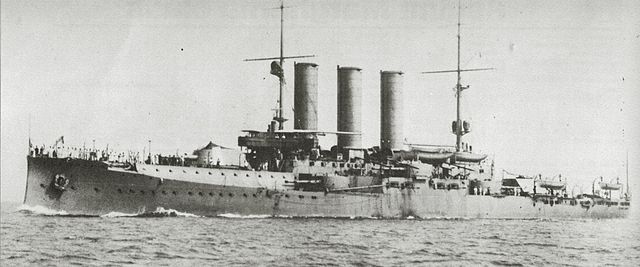

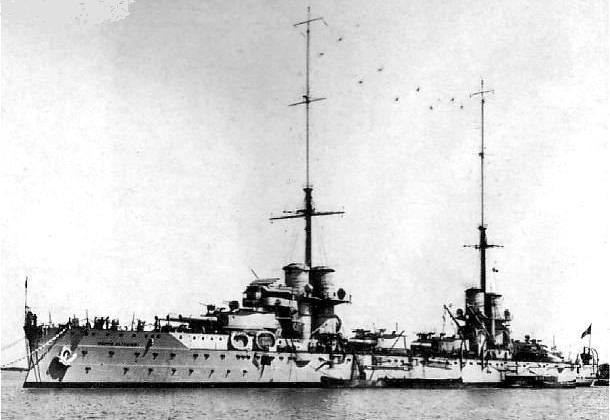

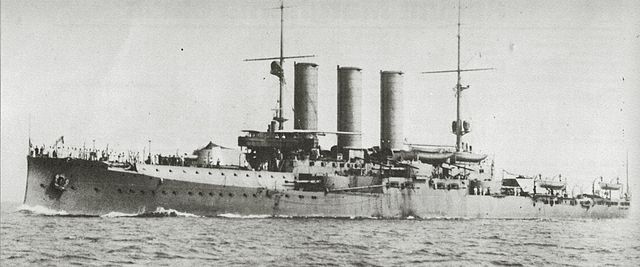

A ship of the Regina Margherita class

Re Umberto class (1888)

Re Umberto class (1888)

Re Umberto, Sicilia, Sardegna

In 1883, the first two ships of this class, Re Umberto and Sicilia, were authorized in parliament by the Finance law. They had been designed by Benedetto Brin, then president of the naval projects committee. In 1885, the parliament also decided to vote for the construction of a third ship, the Sardegna, in order to create a complete squadron.

The latter had the first triple expansion machines and small tubes cylindrical boilers. She was almost 1,000 tons heavier, and two meters taller. In common, they had several unique characteristics: Three funnels, two of which were in tandem, main guns in raised turrets-barbettes forward and aft, with a lower caliber (343 mm versus 430 on the previous Ruggero di Lauria), but they fired twice quicker, and had a better arc of fire, instead of the old school echelon. The hull was therefore significantly longer, but remained low. Sardegna was the first to be equipped with the Marconi Wireless telegaphy system. Italy had quite an advance in this field, giving the fleet amazing tactical flexibility.

In 1912, Re Umberto reached the end of her career and she was used as supply ship, at anchor in Genoa. Striped in May 1914 she ended as a supply ship in La Spezia from June 1915. But she was reactivated in December 1916, converted into a port defense battery, located in Brindisi then towed to Valone. In 1918, she was converted for a final assault on the Austro-Hungarian wel defended port of Pola, where she was planned to lead the way like an expandable bulldozer, followed by 40 MAS, just armed with eight shielded 3-in (76 mm) and many 240 mm Howitzers, fire towers and bow blades. A “spec ops” ships before the British own vessels at Oostende. Towed to Venice for this raid planned at the end of October, the whole operation was canceled with the armistice. She was stricken in 1920.

Sicilia was reformed in July 1914, but resumed service as a supply ship in Taranto, and then a workshop until the end of the conflict. She was stricken in 1923 and BU. Sardegna became flagship of the North Adriatic fleet based in Genoa until November 15, 1917. Then, she was sent to Brindisi, used as a coastal battery with just a secondary armament redced to four 3-in (76 mm) and three 0.5 in heavy machine guns. On July 10, 1918 she was transferred to Taranto, then left in 1919 for Constantinople where she remained until 1922. She was stricken in 1923 and later sold for BU.

Author’s illustration of the Sardegna

Specifications

Displacement: 13,600 T – 15,430 FL

Dimensions: Length 130,7 m (428 ft), Beam 20,4 m (67 ft), Draft 8.84 m (29)

Propulsion: 2 shafts TE engines, 18 boilers, 22 800 hp, 23.3 knots.

Armor: Deck 19 mm

Crew: 185

Armament: 12 x 76 mm, 2 x 450 mm TTs.

Ammiraglio di St Bon class (1897)

Ammiraglio di St Bon class (1897)

Amiraglio di Saint Bon, Emanuele Filiberto

In response to the prohibitive cost of the Re Umberto class, Admiral de Saint Bon, then Minister of the Navy, proposed a new type of economical battleship. He died in November 1892 when specifications had been prepared, and Benedetto Brin who took over as interim chief engineers, passed his work to Vice-Admiral Racchia. Her took over the project and made changes, notably to name the led ship by honoring Amiraglio di Saint Bon. Construction started in July 1893 at the shipyards and arsenals of Venice. Emanuele Filiberto was started in October the same year at the shipyards of Castellamare.

They were launched in April and September 1897, and entered service even before their completion, in February and September 1901. For once, with a quick and efficient construction. Filiberto, which funnels were taller, was however riddled with issues and only operational in April 1902, so 10 years after its design, and once again, these were already obsolescent at the very start of their career. She also diverged by her tertiary armament, comprising six 76 mm, and eight 47 mm.

These two battleships had clearly reduced dimensions and tonnage (5,000 tons less) and 10 inches (254 mm) main guns instead of 13.4 in (343 mm) and corresponding lighter armor. A compromise between battlecruisers and battleships, but with low speed. As a result, they were deemed of little use. Their freeboar was still low and problematic in heavy weather, although the turrets were raised enough. These guns were of a new Ansolda model which proved very successful however.

In 1911-13 they received six searchlights around the funnels and central mast. In 1914, they were scheduled for retirement and demolition in 1915, but Italy’s entry into the wa changed this fat and St Bon served as a coastal defense battery, then as AA defense ship in April 1916, until November 1918 in Venice. Filiberto was converted into a troop transport at the end of 1917, also heavily modified and camouflaged. Eventually both were stricken in 1920 and sold for BU.

Author’s illustration of the Di St Bon in 1900

Author’s illustration of the Emanuele Filiberto in 1917

Specifications

Displacement: 9,650/9,940 t standard, 10,000/10,500 T FL

Dimensions: 111,8 x 21 x 7,70/7,20 m.

Propulsion: 2 shafts TE, 12 Cyc. boilers, 13,500/14,300 hp. 18 knots.

Armor: Belt 250, Deck 68, CT 250, tutters 250, battery 150 mm

Crew: 565

Armament: 4 x 254, 8 x 152, 8 x 120, 8 x 57, 2 x 37, 4 x 450 mm TTs.

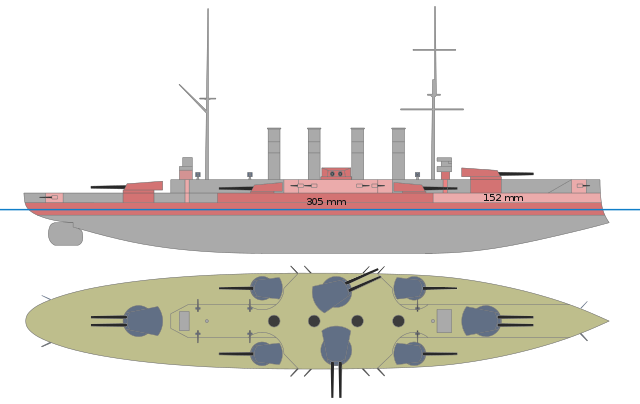

Regina Margherita class (1901)

Regina Margherita class (1901)

Regina Margherita, Benedetto Brin

The two ships of the Margherita class, were the first really large, modern Italian battleships, designed in 1898 by Benedetto Brin, former admiral and chief engineer, now Minister of the Navy. They had to be powerful and fast, even if it meant sacrificing some protection. The basic armament had to be extremely imposing, with in addition of their 12-in battery, not less than twelve 8-in guns (203 mm). But the death of Brin during design put an end to these developments. Chief Engineer Ruggero A. Micheli returned to a more reasonable caliber. The concept will however be kept and applied to future Regina Elena class.

These ships, although poorly protected, were actually 2 knots faster, more manoeuvrable, and held the sea well thanks to their high freeboard. The symmetry they represented between the bow and the stern were intended to deceive gunners and submariners on the real direction of the ship at low speed. In terms of powerplant, the gain in speed was paid in a simplification of the boilers, which all burned coal, abandoning the previous mixed system. Started in 1898-99, launched in 1901 and completed in 1904-1905, they came to a premature end during the Great War: Margherita was struck by two mines laid by UC14 on December 11, 1916 off Valone, and Brin was sunk by an explosive charge laid by Austrian combat swimmers in the port of Brindisi on September 27, 1915.

Author’s illustration of the Benedetto Brin in 1914

Specifications

Displacement: 13,215 t, 14,737t PC FL

Dimensions: 138,65 x 23,84 x 9 m

Propulsion: 4 turbines, 28 Niclausse/Belleville boilers, 21 800 shp, 20,1 Kts.

Armament: 2×2 305, 4x 203, 12x 152, 20x 76, 2x 47, 2x 37, 2 MGs, 4x 450 mm TTs sub

Armor: Barbettes 152, Battery 152, belt 152, turrets 203, deck 80 mm

Crew: 812

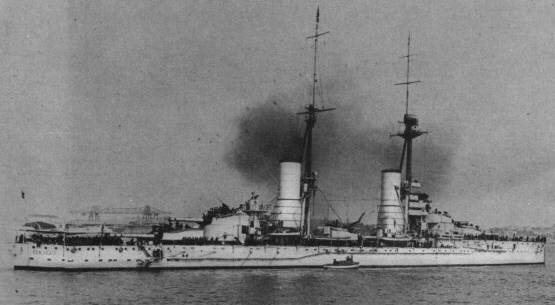

Regina Elena class (1904)

Regina Elena class (1904)

Regina Elena, Roma, Vittorio Emmanuele, Napoli

The last Italian pre-dreadnought battleships were arguably the best, and precursors of the Dreadnought. They were in effect, “semi-dreadnougts”. The minister of the navy in 1899, Giovanni Bettolo, asked chief engineer of naval constructions, Vittorio Cuniberti, for a design of armoured cruiser, 8,000 tons initially, uniformly armed with twelve 8-in (203 mm) guns.

His theory of a powerfully armed, fast protected ship went a long way, the plan for a new battleship class for the Regia Marina gave him the opportunity to apply his principles. The latter was a very fast battleship, 13,000 tons, also more powerfully armed than many of its contemporary among pre-dreadnoughts. Cuniberti personally prepared another more ambitious design of a 17,000 ton ship, armed with twelve 305 mm guns, but refused as too ambitious by the minister. Cuniberti was nevertheless authorized to publish his project of “monocaliber ship” in Jane’s magazine in 1903, not lost by Jackie Fisher back in UK, and only conformed his past intuitions.

The genesis of the Regina Elena, which was to lead to the construction of four vessels in all to constitute a powerful squadron, was therefore a compromise between armored cruiser and the latest specifications of the ministry: It was capable of reaching 21-22 knots thanks to 19,000 to 21,000 shp, much higher than its contemporaries. If it remained a pre-dreadnought by the choice of two 12-in only (in single turrets at that !) its secondary artillery was particularly powerful, with the initially planned Brin’s twelve 8-in (203 mm).

The great difference between the two calibers also made it possible not to confuse the water plumes on impacts, which made it possible to correct fire, unlike the British Nelson which adopted the larger 11 in (234 mm) caliber. However, one can wonder about the use of single and not twin turrets which largely dinimished the overall potential of the design. They could have been the best pre-dreadnought in the world. In general, these ships were applauded by the Admiraltie at the time potential adversaries of Italy were France and Great Britain. Cuniberti deeply influenced Lord Fisher who pushed the Admiralty to start building the HMS Dreadnought, in particular to prevent competing navies from doing it first.

Author’s illustration of the Regina Elena

Specifications

Displacement: 12,550/12,660 – 13,770/13,914 Tonnes FL

Dimensions: 144,20 x 22,40 x 8,6 m

strong>Propulsion: 2 shaft VTE, 28 Belleville boilers, 19,300/21,900 ihp, 21-22 knots.

Armament: 2 x 305, 12 x 203, 16/24 x 76, 2 x 450 mm TTs sub

Armor: Belt 250, Decks 68, Blockhaus 250, turrets 250, battery 150 mm

Crew: 565

Development of Italian Dreanought Battleships

Cuniberti design (1899)

Cuniberti’s famous armored cruiser design. The main turrets carried 203 mm (8-inches) guns, interestingly, in single, lighter wing turrets, and four twin, including two wing amidship. At the time this ship was designed in 1899-1900, the context was not favourable on a budgetary level for massive Naval spendings. But Vittorio Cuniberti design was nevertheless the first “all-big-gun” fighting ship. In addition to this impressive main battery of twelve guns, this cruiser could reach 22 knots while being protected by 6 in (150 mm) of armor.

However it is still not clear if the idea was initiated by the minister of the Navy, Giovanni Bettolo (under the Pelloux II government), or if Bettolo was informed of Cuniberti’s ideas, then decided to offer him a chance to submit his design for a possible approval of the parliament. The parliament rejected the design as too costly. But Cuniberti compromised and obtained the design in 1901-1902 of the Regina Elena class “semi-dreadnoughts”. The original 1899 project was authorized for publications, and ended in a Jane’s article of 1903. It was not the “bright idea” that inspired Fisher to start its own plans, but just a confirmation of what was already in the air on this topic. The Battle of Tsushima in 1905 seemed however to inflex some of these ideas and renew with closer range battles and the importance of secondary artillery, but Fisher kept his course.

Spanish Battleship Proposals (1907-08)

Another line of development leading to the Dante Aligheri was a serie of proposals made to answer an International request by the Spanish Government to design their own first modern battleships, of the dreadnought type. Previously Spain only had the obsolete, 1890s, french-built Pelayo (1887) and a collection of modernized ironclads. The war of 1898 and crushing defeat of the armamda woke up the government and parliament about the importance of a modern and well-trained, well supplied navy.

Although Spain ultimately adopted the Vickers design for the 1912 España class, the initial Italian proposals shed a light on possible alternatives to the Dante:

Tavola B design, Battleship Ansaldo to be built at Cartagena (1907), with all twin turrets, pretty close to the final design.

1908 Tavola C design by Cuniberti (22,000 tons, 12/305mm in two triple turrets, one twin amidships, 21,25 knots.)

Russian Battleships Proposals (1908-1909)

Below are three Ansaldo proposals for Russia, all three of a 23,000 tonnes, triple turret configuration battleship.

All three were prepared by Guiseppe Tavola, chief engineer at Ansaldo in 1908.

-Design A (left) was a 23,000 tonnes standard, 176m x 28m x 8,15m, 21knots, armored with 203mm/102mm Upper belt, 102mm decks, 256 mm CT, 51 mm ASW longit. bulkheads and armed with 6×3 305mm, 16×1 120mm Casemated Guns.

-Design B (middle) was a 21.650 tons project, 167m x 27m x 8,15m, 21,25 knots, same armor but 4×3 305 mm Cannons

-Design C (right) was a 22.000 tons project, 178m x 27m x 8,15m, same speed, same armor and armament but different configuration.

This leaves quite a grasp of what the Italians could have produced of not budget constrained to a specific tonnage. The “A” proposal would have, with no less than 18 12-inches guns, be a serious adversary for anything else at the time, but perhaps HMS Agincourt and her 14 guns. But the all-axial solution was nevertheless seductive in that no firepower was wasted in batteline broadside fire. The final Italian design was nowhere near these protection figures, with at best 250 mm on the belt, 280 for the CT, but 22.8 knots, which was better than many BBs of the time. The Austro-Hungarians with their Tegetthof still choose to take the engineering risk of having four triple superimposed turrets, less of bravado than forced by the size of the Yard’s basin. And the Italians, seeing the path recoignised beforehand, followed suite with the Cesare class.

Argentina Proposals (1908)

A Progetto Ansaldo dated 1908 for Argentina (US Yards were eventually chosen for the Rivadavia class). Reminsicent of the Gangut/Dante with its triple turrets at deck level, and minimalistic superstructures, but unlike the Dante, five turrets for fifteen guns, including two in axis and two in echelon. The aft turrets had raised barbettes for better arcs of fire. Twelve secondary guns in casemates.

Also there was a small metal model preserved at Fondazione Ansaldo, Genoa, likely also a proposal for the Armada de Argentina. Specs shows a much smaller vessels, length of 136m, 24.20m beam, draught 8.2 m, 16,100 tons standard displacement, 19 knots, 4 shafts, range 5,000 nm armed with eight 305mm/50 in twin turrets, 20x100mm/50 in casemates, protected by a main belt of 230 mm, upper belt of 180-150-100mm, 250 mm main gun barbettes, and turrets 250mm (front) 150mm (rear), main deck 38mm.

WWI Italian battleships in 1915

Dante Alighieri, named after the most famous Florentine poet (born 1265), was also the first Italian Dreadnought battleship. Dante followed the Regina Elena class of 1907, and thus was “late to the party”, but innovating as the world’s first battleship with triple turrets, making for a total of twelve 12-in guns. She was thus the most powerful battleship in the world when she came out. The Russians had their own Gangut class inspired by an Ansaldo design, very similar to the Dante, and the Austro-Hungarians were not long to buikt their on, but risking superfiring turrets (Viribus Unitis). Plans had been drawn up by chief engineer, admiral Edoardo Masdea, assisted by Antonino Calabretta, who also fitted her for the first time with four propellers. Dante was also innovative as having eight secondary guns in twin turrets, rather than all in casemates.

The three-year wait, late construction was explained on one hand, to budget constraints as per the other Regina Elena class still completing, and on the other hand benefiting from a meticulous study. Dante was designed a bit like a prototype for following classes. The main turret layout in the axis, was deemed inadequate, but the “all triple” configuration was later corrected with the Giulio Cesare class superfiring and mixed twin/triple turret solution. The vast majority of small defensive guns were on the turrets roof and four on the deck.

Superstructures were minimalistic, narrow to allow the greatest clearance and arc of fire for the amidship turrets notalby, both in chase and retreat. The superstructure decks were stacked close to the forward funnel. Dante was laid down in Castellamare di Stabia, in June 1909, launched in August 1910, completed in January 1913. She was therefore the only operational dreadnought of the Italian Navy in 1914. Capable of 23 knots she was also the faststed in the Mediterranean until the Queen Elisabeth class were deployed. But this speed was paid in armor, sensibly weaker.

Dante Aligheri made only four sorties without notable events during the Great War. As early as 1913, she tested a Curtiss reconnaissance seaplane, and in 1915 had her old 3-in (76 mm/40) replaced by for sixteen 40 mm/50, including four AA. In 1923 she was further modified by the addition of a tripod mast, rear funnels shortened as her masts. She served mainly as a training ship, scrapped in July 1928. As a prototype she could not have been grouped into a division.

Author’s illustration of the Dante in 1914

Specifications

Displacement: 19,552 – 21,600 T. PC.

Dimensions: 168 x 26,6 x 8,8 m

Propulsion: 4 shafts Parsons turbines 23 Blechynden boilers, 32,200 hp. 23 knots.

Armament: 3×3 305mm, 20x 120mm, 13x 76 mm, 3x 450 mm TTs.

Armor: Belt 254, Decks 40, CT 305, turrets 254, battery 98 mm

Crew: 981

Cavour class (1915)

Cavour class (1915)

Guilio Cesare, Conte di Cavour, Leonardo Da Vinci

After the Dante Alighieri, which served as a prototype, a class of first three units was defined by Edoardo Masdea at the beginning of 1910. The specifications always included 305 mm pieces (while in Great Britain we were preparing to switch to 343 mm), but for an authorized tonnage of 23,000 tons, and a speed of 22 knots. The lessons learned from the Dante helped to redefine the plans for these battleships. The first difference was the abandonment of the layout of the central turrets to distribute them in forward and rear echelon, with a single piece remaining in the center, in accordance with contemporary designs. The originality of the Italian concept was to mix triple and double turrets, the latter superior to lighten the efforts of the framework, for a total of 13 pieces, which was superior to all the dreadnoughts built so far, except for the Sultan Osman I, future HMS Agincourt, with its 14 pieces, at the time Turkish order from English shipyards. In 1910, indeed, the sounds of boots were heard in the Balkans, and the sublime door was the most likely potential adversary.

The second particularity of the Guilio Cesare was to return to the solution of barbettes for all the secondary armament (abandonment of the double turrets), picked up in the center, on a reinforced diamond battery easier to protect a priori, and requiring large ranges of hull clearance. Then, the two pairs of chimneys were replaced by two high chimneys framing the central turret, and on which were grafted the successive walkways, also supported on two tripod masts, another originality of the design. The tertiary armament, composed of 19 pieces of 76 mm instead of 13 still took place on the turrets, and 6 on the bridge. The armor of batteries and bridges were reinforced, that of the turrets increasing to 280 mm. The originality had been to design a large blockhouse with walls 280 mm thick, protecting the command and the firing center by the same structure.

The Conte di Cavour was started in La Spezia in August 1910 – June and July for the and Giulio Cesare and the Leonardo da Vinci, at the Ansaldo (Genoa) and Odero (Sestri Ponente) shipyards, launched in August and October 1911, and commissioned on May 14 and 17, 1914 for the Cesare and the Da Vinci, April 1, 1915 for the Cavour. All three were therefore operational when Italy declared war on the Central Powers. These units then formed the first line division, the spearhead of the Italian fleet. But their rare exits from Taranto where they were all three based, to be able to intervene against a possible exit of the Austro-Hungarian fleet from the Strait of Otranto, were without notable facts, although they participated in bombing raids. Four pieces of 75 mm AA were added during the war, and the Da Vinci sank following sabotage by Austrian divers, who had succeeded in forcing the harbor of Taranto, on August 2, 1916. She was refloated in 1919 but finally demolished. The other two were recast twice, and participated in the Second World War.

Author’s illustration of the Guilio Cesare in 1916

Specifications

Displacement: 23,000- 24,250 T. FL

Dimensions: 176 x 28 x 9,3 m

Propulsion: 4 shafts Parsons turbines, 20 Blechynden mixed boilers, 32,200 hp. 23 knots.

Armament: 13x 305mm, 18x 120mm, 19x 76 mm, 3x 450 mm TTs.

Armor: Belt 254, Decks 111, CT 280, turrets 254, battery 127 mm

Crew: 1237

Andrea Doria class (1916)

Andrea Doria class (1916)

Andrea Doria, Caio Duilio

Based on the plans of the three Giulio Cesare, two new dreadnoughts were approved in 1911 and designed by Chief Engineer and Vice-Admiral Giuseppe Valsecchi: These were the Andrea Doria and Caio Duilio, started at La Spezia and Castellamare in February and March 1912, launched in March and April 1913 and completed on 10 May 1915 for the Duilio (thus before Italy entered the war), and March 1916 for the Doria.

Very similar to the Cesare from which they borrowed the essential, they differed however on many points: Their secondary parts passed to the caliber 152 mm and were less numerous, distributed at the front and the rear of the hull, with low ranges to better respond to abeam attacks from torpedo boats and destroyers. Their chimneys were largely raised, the front tripod mast passing in front of the chimney, the central turret was lowered to improve stability, (as well as the deepened hull) and their shielding of turrets and reinforced battery. Finally they received from the start 6 pieces of 76 mm AA of caliber 50. Their power and their speed were slightly lower.

During the war, the two buildings were based in Taranto, forming the 2nd line division, playing a mainly deterrent role. They were hardly active in the war, flying only two sorties. After the war they received faster 76 mm 40 caliber AA guns and 2 40 mm Vickers Bofors. In 1925, they received a Curtiss reconnaissance seaplane, and a catapult for the latter in 1926. They were completely overhauled and rebuilt between April 1937 and October 1940, even more radically than the Giulio Cesare, and their career during the Second World War world was much more active. They were both removed from the lists in 1956, after forty years of service…

Author’s illustration of the Doria in 1917

Specifications

Displacement: 23,000- 24,730 T. FL

Dimensions: 176 x 28 x 9,4 m

Propulsion: 4 shafts Parsons turbines, 20 Blechynden mixed boilers, 30,000 hp. 21 knots.

Armament: 13x 305mm, 16x 152mm, 19x 76 mm, 3x 450 mm TTs.

Armor: Belt 254, Decks 98, CT 280, turrets 280, battery 130 mm

Crew: 1237

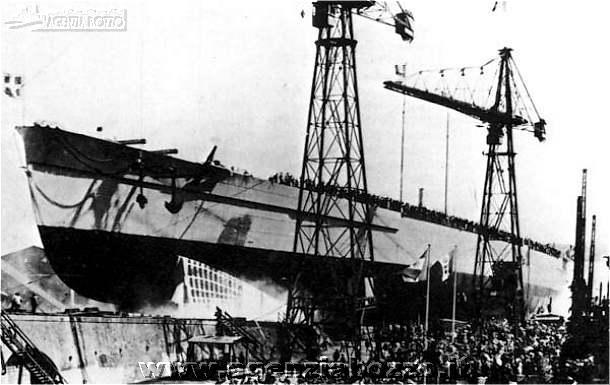

Caracciolo class (1916)

Caracciolo class (1916)

Francesco Caracciolo, Marcantonio Colonna, Cristoforo Colombo, Francesco Morosini

The last class of dreadnoughts designed before the war in Italia was the Caracciolo, started in 1914-15. They were radically new ships, much faster and powerfully armed. They showcased the new generation of fast battleships also, born after the Washington treaty. But because of the war, they were never completed.

When the Washington Treaty was ratified in 1923, it put an end to an industrial and military escalation that had begun in 1914, towards faster and better armed ships. Italy was no exception to the rules. In 1916, the last dreadnought to enter service, the Andrea Doria, was fitted with only 12-in guns and a top speed of 21 knots.

However, the British had just introduced their five Queen Elisabeth class into service, armed with 381 mm guns and capable of 23 knots. Aware of this delay, and like Germany with the Bayern class, the Italian Admiralty wanted a new battleship project on the table in 1914, intended to retake initiative, notably over The Royal Navy (then a potential adversary). Studies were conducted by Chief Engineer Rear Admiral Edgardo Ferrati. The first plan envisaged a ship armed with not less than twelve 381 mm (15 in) in four triple turrets, and twenty 152 mm (6 in), which combined with their speed, made them the world’s most powerful battleships.

But this first draft project was far too ambitious for the means of the navy, and was revised down considerably. The second project had twin, not triple turrets, resulting in ships closer to the Queen Elisabeth. Among its specificities, this new project also adopted the 6-in as a secondary caliber, and 102 mm (4 in) for dual-purpose guns, instead of the old 76 mm (3 in) on turret’s roofs, plus 40 mm Breda AA guns as well as a significant reinforcement of armor and torpedo armament, and loss of speed.

The keel of the lead vessel, Francesco Carracciolio was laid at Castellamare di Stabia in October 1914, and construction was well underway, while three other keels (Cristoforo Colombo, Marcantonio Colonna, and Francesco Morosini) were laid at Ansaldo, Odero, and Orlando in March and June 1915. But once the war had broken out, it seemed impossible to complete them, as the demands on personnel and equipment were so great.

The priorities of the Admiralty were then to mobilize its means for the construction of light vessels, more economical and faster to build, and the maintenance/repair of active ships. Construction of the four giants was suspended in March 1916. Caracciolo, whose entry into service was initially scheduled for 1917-18, would have displaced almost 10,000 tons more than the previous Dreadnoughts and being capable of 28 knots, doubled as battlecruisers. They constituted the world’s first examples of “super-dreadnoughts” such as those built in all shipyards in the late 1930s.

When the cancellation occurred, 9,000 tons of the carracciolo’s hull had been assembled. At the end of the war, the question of this hull arose, and a shipowner, the “Navigazione Generale Italiana”, proposed a commercial conversion, paying for the completion, so she was launched eventually in October 1920. Nevertheless, the project did not materialize, and the hull was dismantled. For the others, the dismantling was also quickly carried out, all the more easily as little metal had been assembled. The artillery was either used on Isonzo Front’s wartime Italian monitors in 1917-18, including the famous Faa’ di Bruno, or recycled (re-cast).

Author’s illustration of the Caracciolo

Specifications

Displacement: 31,400t, 34,000t FL

Dimensions: 212 x 29.6 x 9.5 m

Propulsion: 4 shafts Parsons Turbines, 20 Yarrow boilers, 105,000 hp. 28 knots.

Armament: 4×2 381mm, 12x 152mm, 8x 102mm, 12x 40mm, 8x 533 mm TTs sub

Armor: Belt 303, Deck 40, CTs 400, Turrets 400, Battery 220 mm

Crew: 185

Ferretti’s tandem turret Designs (1916)

Ferretti’s 10/381 “quintuple turrets” battleship design was only known by a proposal, to succeed the Carraciolo class. The original drawing were published in ”Warships of the first battle line” in “Transactions of the International Engineering Congress” of 1916. The design showed a “Kearsage style” pair of triple turrets, with fixed twin turrets above, for a total of ten 381 mm guns plus 12 secondary guns in triples turrets fore and aft, and a powerful AA which was quite avant-gard at the time. Not much is known about the fate of such design. The twin stage turret was already proved a bad idea due to loading concerns, plus stability issues because of the topweight.

General Edgardo Ferrati Designs (1915-1919)

Rear Admiral and General of naval engineering Edgardo Ferrati was the designer of the Caracciolo class battleships, first designed in 1913. It was proposed in two occasions to convert the ship in an aircraft carrier like HMS Argus and later a revised vessel in 1921 with an island superstructure, and then a total conversion in a merchant ship. Revised specs for 1919: 31.400 tons, 34.000 FL, 29,6 m beam, height 13,75 m., 9,50 m draught and 1800 t. oil, same output for a 8,0000 miles range with 1,800 oil tons.

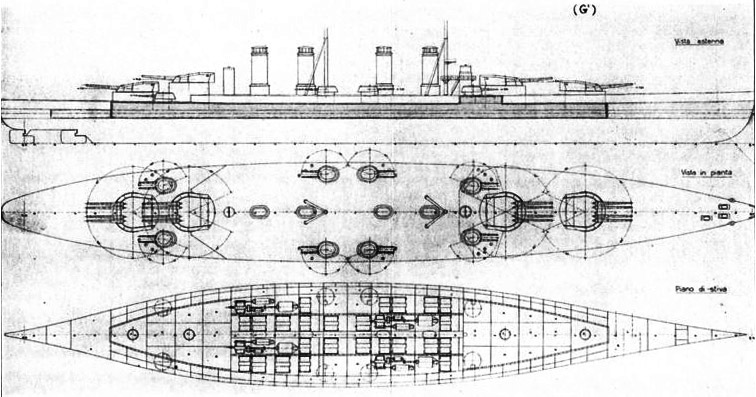

During the development of the Caracciolo there was an initial first design proposal, somehow similar to the final model, but the initial design oassed through three series of possible variants called F,D and G. These projects were fairly similar in an evolutive process, with the F series as first variant, then D and eventually G, the last one. They were all “super-dreadnought” battleships with the same main artillery, but many alternative turret proposals to play with the armour scheme and secondary battery plus always the same 28 knots top speed. What made them remarkable -although technologically still a stretch, and problematic in some ways, was their quadruple configuration.

Design F, was the lighter of all variants, with just two quad turrets and for secondary guns eight turrets with dual 170 mm guns, and 24 single mounted 102 mm guns, plus the usual 533 mm torpedo tubes battery (8). Output was planned at 55000/75000 HP for 25~27 knots. Armour was light, battlecruiser standards, with 270 mm at best. The sub-variant was repowered to reach 95000~115000 Hp, for 31 knots, making her an obvious battlecruiser.

Design D: 3×4 381mm, 16 dual mounted 152 mm guns, 20 single mounted 102 mm

Design D bis: same, but 12 dual mounted 170 mm guns

Design D1: same and back to 16 dual.

Design D2: 12 dual again or not at all (only the 20 102 mm).

The D series was similar to the F but with a larger armament and more outptut: Three quadruple 381 mm gun turrets and same secondary armament. 65000-85000 HP estimated for 25~27 knots, same armor layout as the “F” series.

Design G: The largest, on paper 37,000 tonnes battleships, so before Washington limitations. The G class were still lightly protected by just 50 mm of deck armor. They were supposed to carry no less than sixteen 381 mm guns in four triple turrets, all superfiring (the same as two Queen Elisabeth class put together). Same guns, but with with an improved reloading system for 2 rpm and 830 m/s. Secondary artillery in eight twin turrets with 170 mm guns (7 inches), twenty-four dual-purpose 102 mm guns and later 40 mm AA guns.

In 1915, that was quite impressive by any standard, but of course, budgetary-wise, totally unrealistic. All these plans are stored at the USMM (Italian Navy Historic Office) today. They were published, along with the associated data, to the Bollettino d’Archivio, Dic. 1988 by A. Rastrelli. All in all, quad turrets were rejected on three points: The turret weight (and structural problems), the famous case of “all eggs in the same basket” hit, and massive dispersion. The French did not have such preventions.

Read more/Src

Gardiner, Robert, ed (1979) Conway’s all the world’s fighting ships 1865-1905 & 1906-1921

Clowes, W. Laird (1905). The Naval Pocket-Book. London: W. Thacker & Co.

Ordovini, Petronio, Sullivan “Capital Ships of the Royal Italian Navy, 1860–1918 Part I.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign