The HMS Tiger: Feline beauty and hard shell

Described by historian John Keegan as “certainly the most beautiful warship in the world then, and perhaps ever”, the Tiger was also better protected, yet cheaper than the older Lion class, the “big cats” disliked by the admiralty. Despite of her merits, no additional battlecruiser of the same type was built. Alone, the Tiger nevertheless proved her worth during three battles. If it Was not for the Washington treaty limitations, with the right modernization should could have become the British equivalent of the Kongo class.

HMS Tiger served with Beatty’s 1st squadron of battle cruisers. She took Part in the Dogger Bank battle, her first major commitment, taking six hits, blowing off her Y rear turret, but only suffered 11 dead and 11 wounded. She participated in the battle of Jutland, firing no less than 303 rounds, but only scored thee hits, for conceding 15 heavy impacts. Q turret was blown ff, as a barbette, but the ammunition stores were spared a flash and she returning to Rosyth, listing to port with 24 dead and 46 wounded. She also took part in the seocnd battle of Dogger Bank. After the treaty of Washington was signed she started a second life as a gunnery training ship after two years of conversion (1924 to 1929), retired in 1931.

Genesis of the Tiger

Despite active lobbying from Sir “Jackie” Fisher, the Admiralty began to doubt the usefulness of battle cruiser concept in 1911 already. Instead of launching a new class of three ships, a sole battlecruiser was authorized in the 1911–12 Naval Programme, and a less expensive ship than the last “splendid cats”. (In fact the cost was £2,593,100) This plan focused on improvements based on the Queen Mary, integrating the experience gained in years. Although not fitted with a good protection, the Tiger was a fine vessel with pleasant lines, original though childless. Although it was laid down after the Kongo, the chief engineer of Vickers drew extensively the ideas contained in the design into the Tiger, and the last of the “splendid cats” – a little less expensive than the others, was launched in December 1913, completed and accepted into service after trials in October 1914.

Design

The hull had an overall length of 704 feet (214.6 m) for 90 feet 6 inches (27.6 m) in beam, and standard draught of 32 feet 5 inches (9.88 m), deeply loaded and battle ready. Displacement was 28,430 long tons (28,890 t) standard and up to 33,260 long tons (33,790 t) deeply loaded. The hull was only 4 feet (1.2 m) longer, 1 foot 5.5 inches (0.4 m) wider tha n the previous class, she displaced 2,000 more long tons, with a metacentric height of 6.1 feet (1.9 m).

Armaments wise, turrets placement and superstructure were completely revised, as well as the position and height of funnels and the front firing control tower. A potent secondary armament was added, located into the central battery, giving concentrated superstructures to clear the range, like the Japanese Kongo class, then under construction at Vickers.

Again, it was specified a very high speed, 28 knots from a nominal 85,000 hp and more resulting from machines pushed white hot to give 105 000 hp (in theory capable of giving 30 knots). In fact 29 knots were achieved with 104,000 hp, but with a daily consumption rising to 1245 tonnes of fuel oil. The smaller hull necessitated twisted compromises to try to find the missing extra storage. Her crew consisted of 1,112 officers and ratings at the beginning of the war, reaching 1,459 in April 1918.

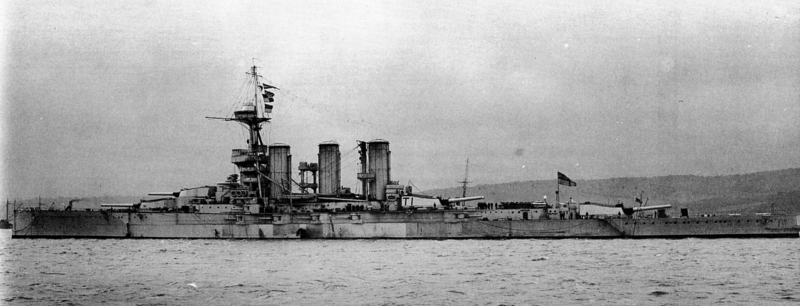

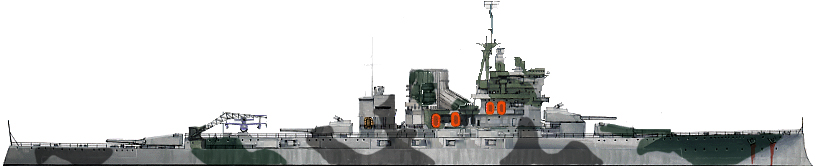

The HMS Tiger in 1918.

Powerplant

HMS Tiger was given two paired Brown-Curtis direct-drive steam turbines. They were placed in separate engine-rooms to avoid losing all power in case of a flooding. Each turbine set comprised high-pressure ahead and astern turbines. The high pressure drove an outboard shaft while the low-pressure ahead and astern turbines drove the inner shaft. Both shafts ended with three-bladed propellers 13 feet 6 inches (4.11 m) large. The steam came from no less than by 39 Babcock & Wilcox water-tube boilers. They were also compartimentalized into five boiler rooms. These boilers worked at 235 psi (1,620 kPa; 17 kgf/cm2). The powerplant was rated for a total of 85,000 shaft horsepower (63,000 kW). With forced heating, this went up to 108,000 shp (81,000 kW) when forced, however on trials, 104,635 shp (78,026 kW) were reached although she met her constract speed of 28 knots (52 km/h; 32 mph), even exceeding it by a knot.

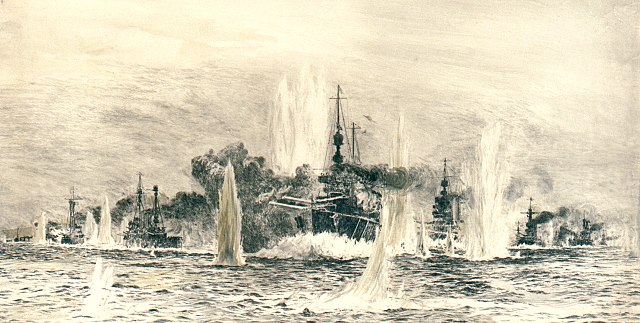

HMS Tiger main guns, ‘Q’ turret, painting

Fuel stowage was mixed, like the boilers heating, 3,800 long tons (3,900 t) of fuel oil, 3,340 long tons (3,390 t) of coal. In total these 7,140 long tons, way more than HMS Queen Mary for example (4,800 long tons), with a varied repartition along the ship’s double hull and caissons. Fuel consumption was 1,245 long tons (1,265 t) on average per working day at sea, staying at 24 knots (44 km/h; 28 mph). At this optimal speed, 3,300 nautical miles (6,100 km; 3,800 mi) could be achieved. Again, HMS Queen Mary, the lmasyt of the “Big Cats” only reached 2,400 nautical miles (4,400 km; 2,800 mi). In addition electrical power to subsytems was provided by four direct current electric dynamos mated on the drives, producing together 750 kilowatts (1,010 hp), which fed the electrical system at 220 volts.

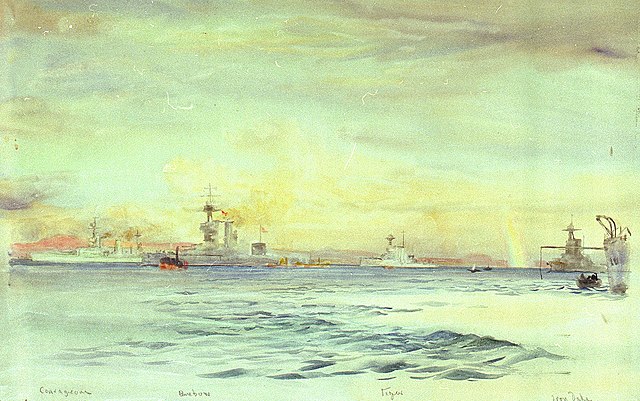

HMS Tiger and the Grand Fleet at Scapa Flow – Painting (cc)

Armament

Primary: HMS Tiger had about the same artillery than previous battelcruisers: Eight 45-calibre BL 13.5-inch Mk V guns in four twin turrets. They were hydraulically powered and called A-B, Q-X because of the situation of the third turret. The mounts allowed the barrels to depressed to −5° and be elevated to +20°. However directors which controlled them only reached 15°. Fortunately superelevating prisms were installed just before the Battle of Jutland to increase that figure.

Each of these main guns fired 1,400-pound (635 kg) shells (standard HE) at 2,491 ft/s (759 m/s). To the max elevation, range was 23,740 yards (21,710 m). The standard rate of fire was below 2 rounds per minute, faster if security measured were botched like in the other “big cats” at Jutland. 1040 rounds were stored in wartime, so this provision rosed to 130 shells for each of the eight gun.

Fire control was assured one of the two fire-control directors, the first installed on the fore-top, foremast and the other on the aft superstructure, which doubled as the torpedo control tower. Bith were 9-foot (2.7 m) rangefinders under armoured hoods. The one above the conning tower passed its data to the ‘B’ and ‘Q’ turrets via a Mk IV Dreyer Fire Control Table. It was located in the transmitting station, deep below the waterline. Range and deflection data were calculated from the observation plots there. This data camed from a mechanical analog fire control instrument in the armoured tower, called Dumaresq Mark VIII*, provided by Fidelity Engineering Company, Limited of London.

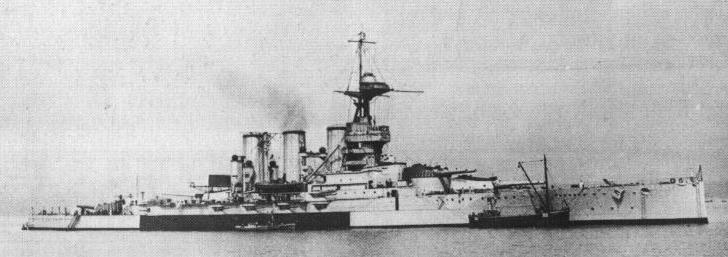

HMS Tiger underway, date unknown.

Secondary:

-The battery was in casemates, twelve BL 6-inch Mk VII guns total, and their mount could depress −7°, elevate 14°. Their shells weighted 100-pound (45 kg), muzzle velocity was 2,770 ft/s (840 m/s), range of 12,200 yd (11,200 m) on average at max elevation. Rate of fire was 8 rpm on average. So they 120 rounds were stockpile for each gun.

-In addition, the Tiger was given two QF 3 inch 20 cwt Mk I anti-aircraft guns, on high-angle Mark II mounts. They can elevate up to 90°, fired a 12.5-pound (5.7 kg) shell at of 2,604 ft/s (794 m/s), at a ceiling of 23,000 ft (7,000 m) and 16-18 rpm on average. 300 rounds were carried for each gun, reduced to 150 rounds in wartime. For these, a second firing control station was fitted, one for each broadside, from 1915.

–Four 21-inch (530 mm) submerged torpedo tubes mounted into the beam, port and starboard pairs, either side of the armour belt end. 20 Mark II*** torpedoes were carried total, each fitted with 400 pds TNT warhead (181 kg). They could be set to two speed, 45 knots and 4,500 yards (4,100 m), or 10,750 yards and 29 knots.

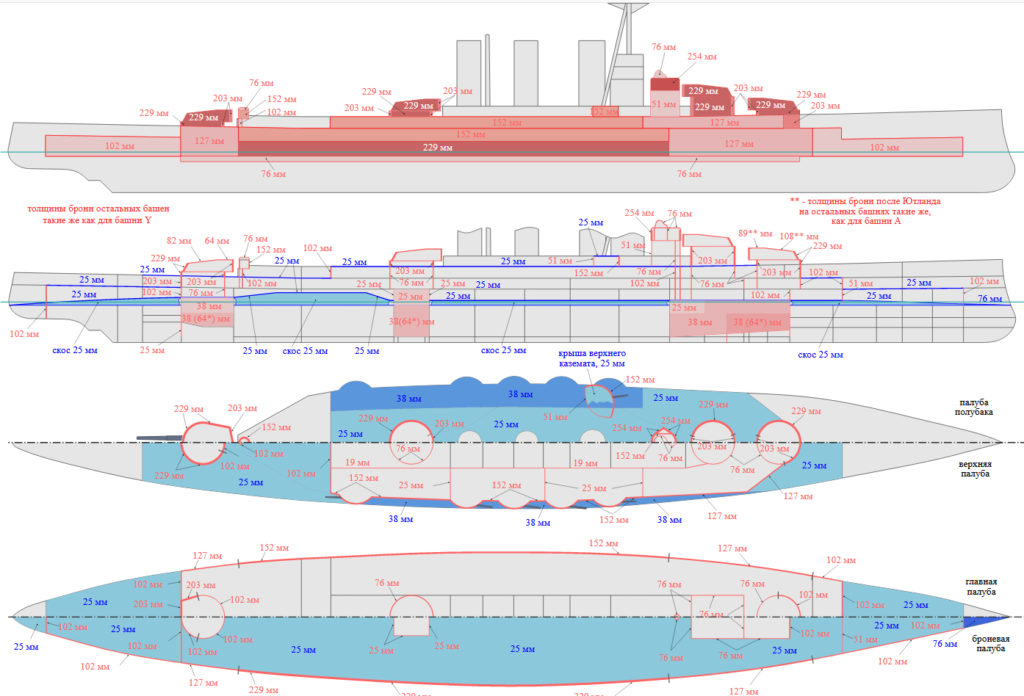

Armor Protection

Tiger’s armour protection was similar to that of Queen Mary with a waterline belt made of Krupp cemented armour, 9 inches (229 mm) thick, thinned downed to four inches on the aft end. The bow or the stern were left unprotected. The belt under the waterline ws thinned down to 27 inches (686 mm) with a strake of 3-in on 3 feet 9 inches (1.14 m) below that. This portion went from ‘A’ barbette to ‘B’ barbette. This was pretty much the system developed for Vickers’s battlecruiser Kongo, and that was the sold similarity with HMS Tiger. Like previous Battlecruisers and the Queen Mary, HMS Tiger had an upper armour belt of 6-in, thinned to 5-in abreast the end barbettes.

However HMS Tiger innovated with an additional strake of 6-in above the upper belt, which protected the secondary armament. The transverse bulkheads closed the ends of the armoured citadel were 4-in thick. Also armored decks used High-tensile steel, and ranged from 1 to 1.5 inches (25 to 38 mm).

Main gun turrets were protected by 9-in, on the front and sides, with roofs 2.5 to 3.25 inches (64 to 83 mm) thick. Barbettes were protected by 8-9 in (203 to 229 mm) and 3-4 in for the part left inside the citadel. The main conning tower had walls 10 inches (254 mm) thick and 3-in roof. The communication tube had walls 4-in thick. The aft conning tower was given 6-in walls and a 1-in cast steel roof. The torpedo bulkheads were 1.5 to 2.5 in (38 to 64 mm) in High-tensile steel, abreast the magazines. The Battle of Jutland reports urged modifications to this scheme, notably over plunging shellfire, so 295 long tons (300 t) of additional armour was fitted, spread between the turret roofs, decks over the magazines, and bulkheads separating at the 6-in guns levels.

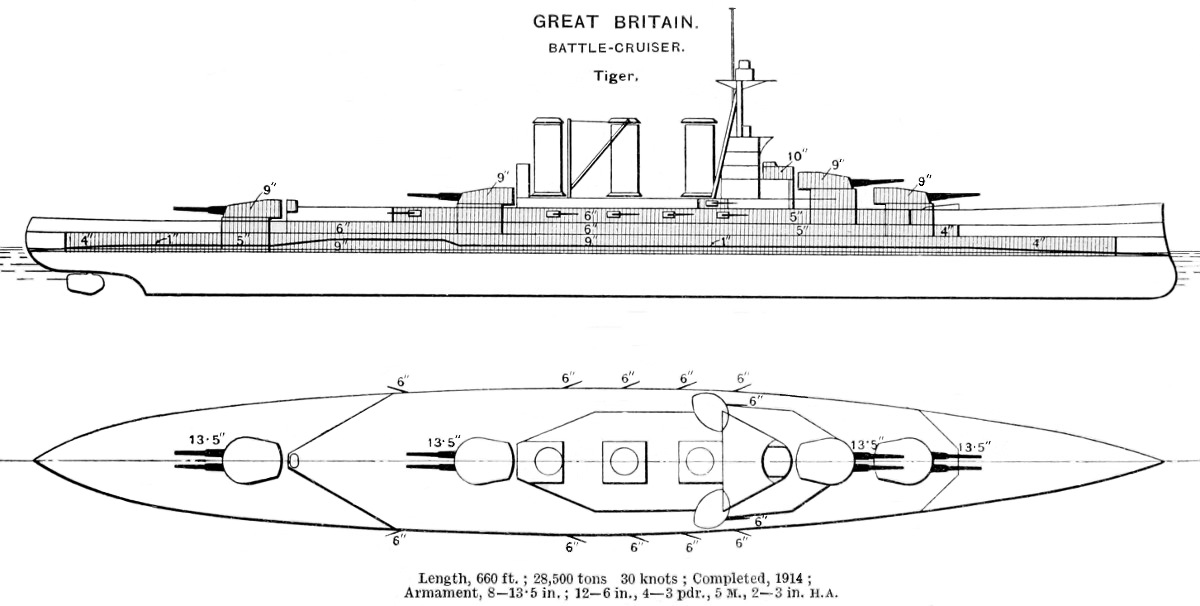

HMS Tiger profile

Refits

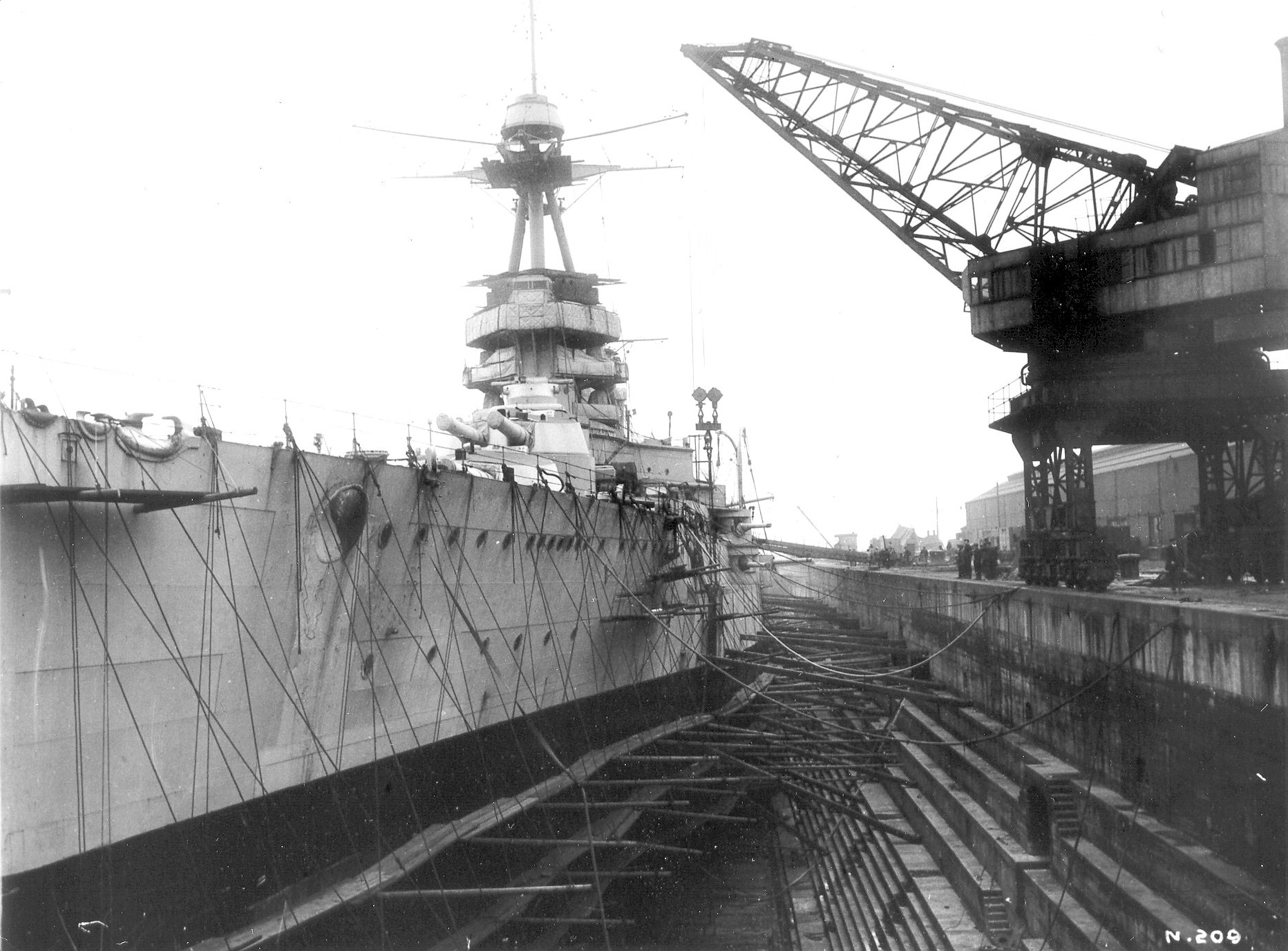

The most important occurred at the drydock at Rosyth, which started on 10 November 1916 and lasted to 29 January 1917. Her turret roof armour were thickened against plunging fire. Also, ‘A’ and ‘Q’ turrets received 25-foot (7.6 m) rangefinders, 15-foot (4.6 m) ones on ‘X’ turret and the conning tower as well as the torpedo control tower. A new fore-top 12-foot (3.7 m) rangefinder was also fitted. Three 9-foot (2.7 m) models were installed on ‘B’ turret, gun control tower and compass platform roof. At last, the already crowned fore-top received a 6-foot-6-inch (2.0 m) rangefinder for the anti-aircraft guns later in the war.

The HMS Tiger during the surrender of the German fleet in November 1918

Active service

Laid down at John Brown & Co, Clydebank, 6 June 1912, HMS Tiger was launched on 15 December 1913, and commissioned on 3 October 1914. For the British taxayer, she was declared costing £2,593,100. In fact she was still outfitting when the war broke out and Captain Henry Pelly was appointed in command. At last on 3 October, she was commissioned in Beatty’s prestigious 1st Battlecruiser Squadron; She was deployed for her first mission after the Battle of Coronel, searching for the ellusive German East Asia Squadron. Beatty estimated then she was not fit to fight, with three dynamoes out of action and unsufficient training due to bad weather. Nevertheless, she departed in a mission that would turn soon into her first battle.

The Dogger Bank: First serious test

On 23 January 1915, German battlecruisers (Admiral Hipper Sqn) headed to the Dogger Bank, chasing for British fishing boats and other craft which could warn the admiralty over German moves. By that time, the British were able to decipher coded messages and were already en route to intercept them. Beatty was informed of them at 07:20, 24 October, by British light cruiser Arethusa, spotting her German vanguard opposite, SMS Kolberg. 15 minutes after, the Germans spotted Beatty’s battlecruisers in return, and Hipper ordered to head south at 20 knots, expecting to flee them if they were indeed enemy ships.

Meawnhile Beatty ordered full speed to catch them and the Lion, Princess Royal and Tiger in the lead made 27 knots at that point. HMS Lion opened fire at 08:52, at 20,000 yards, followed by the others but both the range and low visibility failed to hit before 09:09, SMS Blücher was. The distance fell to 18,000 yards and the German ships concentrated their fire on HMS Lion. Orders were given for each to pick a corresnding targets, but this was not undesrstood and HMS Indomitable engaged Blücher and Seydlitz, as HMS Lion. SMS Moltke was left unscaved, and after a brief u-boote scare, at 11:02, the pursuit resumed. Rear-Admiral Sir Gordon Moore misinterpreted signals and veered North-east to attack the limping Blücher and left the line. Blücher ended as involuntary victim, saving Hipper’s battlecruisers.

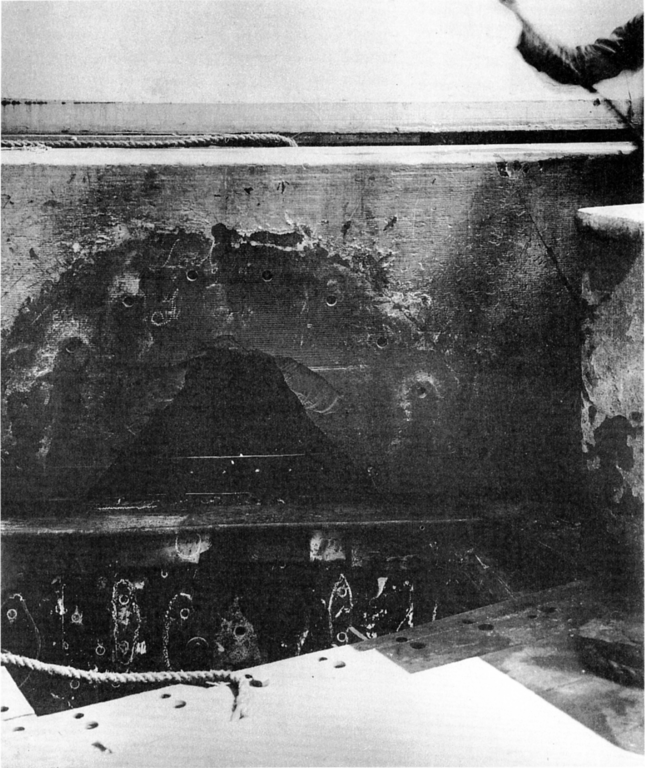

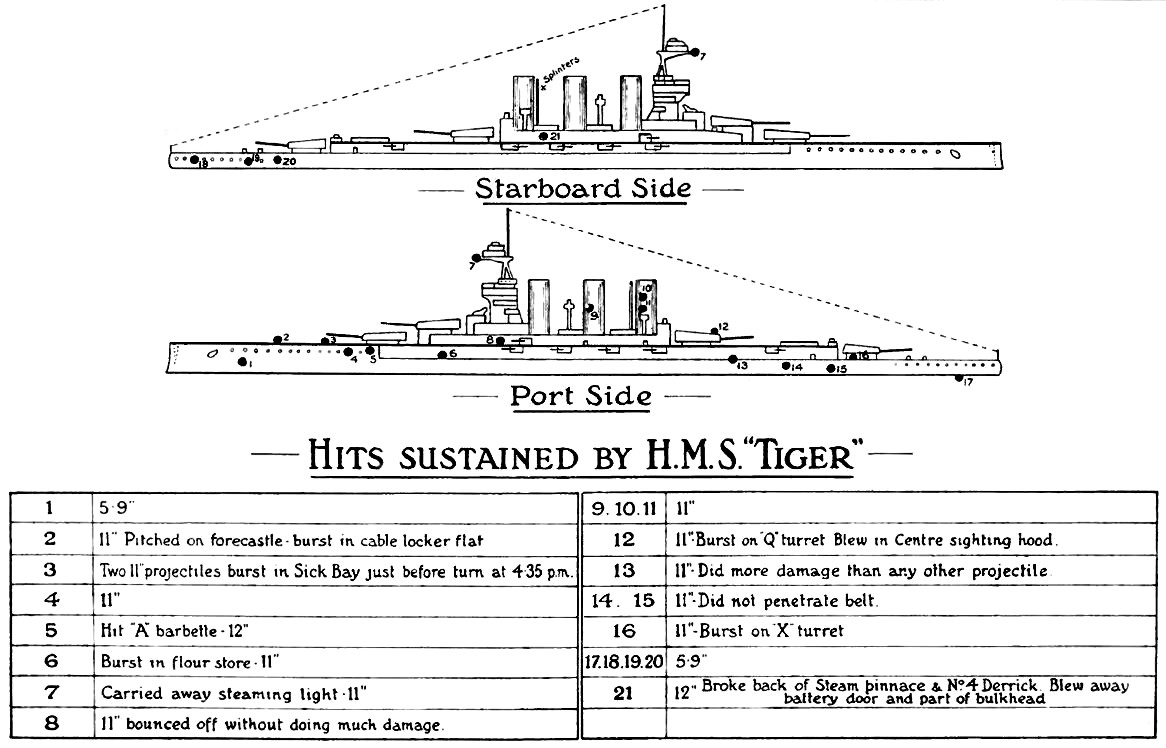

HMS Tiger took six German hits, a 280 mm shell bursting into the ‘Q’ turret roof, fragments damaging the gun’s breech mechanism, jamming the training gear. She had to declared back home, Ten killed and 11 wounded. The repairs ended on 8 February. Reports showed she was really inaccurate, with two hits for 355 13.5-inch (340 mm) shells fired, on Seydlitz and Derfflinger. Lord Fisher went to criticise Pelly’s management. Beatty however attempted to diffuse this and the ship was refitted quickly on December 1915. This was not the last time.

Jutland: The battered beatty veteran

By May, 31, 1916, HMS Tiger with the 1st BCS sally forth to try to intercept the High Seas Fleet rush into the North Sea. Here again, decoding messages has been decisive and the British Battlecruisers are already out as sea since a while when Hipper’s squadron spotted their opposites at 15:20. Beatty however failed to see them in return until 15:30. After an east-southeast heading to cut off the German’s retreat path, Hipper himself ordered a starboard turn, trying to reach a n escaping south-east course. This manoeuver allowed also to fell back on the High Seas Fleet positioned 60 nautical miles behind, essentially luring Beatty into a trap.

The “Run to the South” at 15:45 allowed Beatty to run parallel to Hipper’s course, at a range of 18,000 yards. The Germans fired first (15:48) and the 1st BCS was echeloned, HMS Tiger taking position at the rear and west. She was essentially the closest to the Germans. Her captain however failed to register Beatty’s fire distribution order like in the previous battle. German fire proved accurate and HMS Tiger was hit six times by SMS Moltke. In seven minutes ‘Q’ and ‘X’ turrets were out of action, but otherwise damage was not serious.

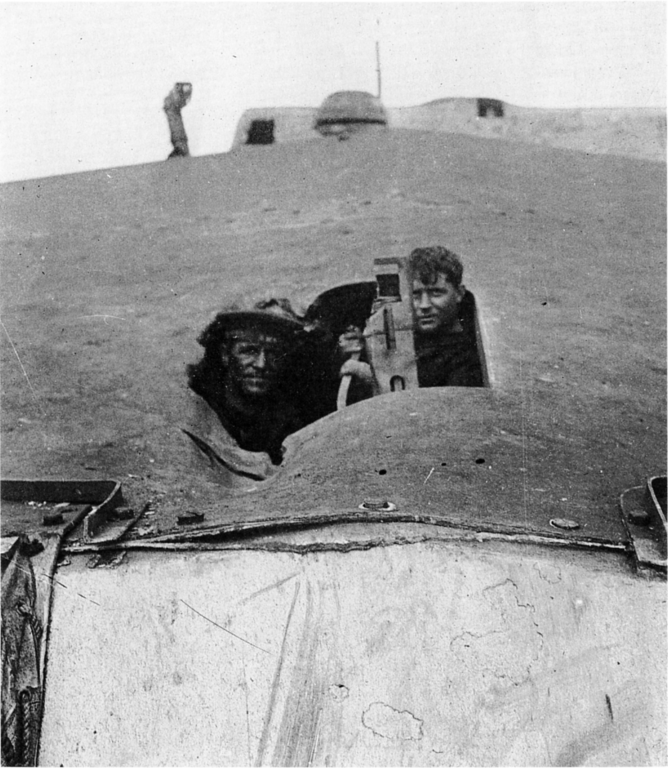

When the range was down to 12,900 yards (11,800 m), Beatty ordered to change course to starboard, opening up the range. Indefatigable was hit and was soon lost, magazines exploding. Despite of this, the range was soon too great and Beatty altered course this time to port, closing in at 14,400 yards. It was then soon starboard again. However HMS Queen Mary was also lost in a cataclysmic forward magazines explosion. HMS Tiger on her part, saw this first hand, at 500 yards, forcing her to make a hard-a-starboard manoeuver to avoid collision. At 16:30 HMS Southampton spotted and reported the High Seas Fleet’s lead ships. Beatty later would turn north, bringing his last ships to safety. HMS Tiger had been hit 17 times, from SMS Moltke. Damage was serious but she still could have continued fighting.

The Germans turned turn north themselves to catch them, but Beatty maintained full speed and he soon outrange them. They tried to join the Grand Fleet whereas they opened fired again at 17:40 on the Germans, while setting sun blinded German gunners. He went on engaging Hipper’s fleet and later, both Scheer and Beatty would lost sight of each others in the haze. Beatty changed course south-east, south-southeast and later Lion’s gyrocompass failed and she led the squadron in a complete circle. At 18:55, Scheer closed in with the Grand Fleet which meanwhile prepared to cross Scheer’s “T”. But Scheer escaped the trap.

Later the ships lost sight and German torpedo boats engaged the British destroyer squadron, whereas Beatty was led by the sound of gunfire, westwars. He spotted the battlecruisers at 8,500 yards and opened fire. It was 20:20. Soo a German pre-dreadnought battleship (Rear Admiral Franz Mauve) was spotted and later sunk. Eventualy after an other exchange, HMS Tiger returned to Rosyth Dockyard (Scotland) two days later. She was docked for repairs, lasting unil 1 July. Reports over HMS Tiger’s 18 hits, with 24 killed and 46 wounded, made sensation. She fired 303 shells, but was credited with just one hit on SMS Moltke,2 on SMS Von der Tann, ans also 136 6-inch rounds, on the light cruiser Wiesbaden and destroyers.

Late war career

After her repairs, HMS Tiger served briefly as flagship for the 1st Battlecruiser Squadron whereas HMS Lion was in drydocks for repairs. On 18 August, during the evening, the Grand Fleet received a message from Room 40 that the High Seas Fleet was about to depart the naval base in its entirity this night, less the II Squadron. The objective was Sunderland, recce would be assumed by airships and submarines. The Grand Fleet steamed up and sailed with 29 dreadnought and six battlecruisers, and every officers expected (hoped) for a new Jutland, this time expecting not to left the Germans escape.

Jellicoe and Scheer received conflicting intelligence however and both fleets passed each others in the North Sea, the Grand Fleet north and Scheer south-eastward. The Germans steered for home and soon the British did the same. The RN lost a cruiser to submarine attack, while a German dreadnought was damaged by a torpedo.

HMS Tiger last years were spent in routine patrols in the North Sea. Both fleets were now prevented to sail again. However she did provide support for the light forces engaged at the Second Battle of Heligoland Bight, 17 November 1917. This was a distant support: She was never cose enough to open fire. In between she had a flying-off platform installed on ‘Q’ turret and searchlight platform on the third funnel. By 1918 however, her topmast was moved to the top of the derrick-stump and a large observation platform fitted to it while the smaller rangefinders were replaced.

HMS Tiger in drydock

Post war carrer

HMS Tiger received in 1919 new flying-off platform for a Sopwith Camel on ‘B’ turret roof. Later she collided with HMS Royal Sovereign by late 1920 in the Atlantic but the damage was not too great and repairs were done. HMS Tiger survived the Washington Naval Treaty as placed in reserve, 22 August 1921. She was refitted in March 1922, receiving a 25-foot rangefinder on ‘X’ turret. Four 4-inch (102 mm) guns replaced her 3-inch AA guns. The ‘Q’ turret flying-off was removed.

HMS Tiger was recommissioned in 1924 as training ship, until 1929. At that stage, she replaced HMS Hood which was planned for a refit, out of commission. HMS Tiger brief active service was to maintain the three Battlecruiser Squadron normal strenght alongside Renown and Repulse. In 1930, HMS Tiger was perfectly serviceable and could have been taken in hand for a major reconstruction, but she was old, and decision was taken to discard her after the new reduction signed at the London Naval Conference of 1930. Captain Kenneth Dewar was replaced by Arthur Bedford until early 1931, when she was decommissioned, paid off on 15 May 1931 at Rosyth, and sold for scrap in 1932.

Links/src

Specs Conway’s all the world fighting ships 1921-1947.

The Tiger’s crew list

On maritime Quest

Additional tech info on battleship-project.org

The HMS Tiger on wikipedia

The Beatty Papers. Volume I. London

Breyer, Siegfried (1973). Battleships and Battle Cruisers, 1905–1970

Brooks, John (2005). Dreadnought Gunnery and the Battle of Jutland: The Question of Fire Control.

Brown, David K. (2003). The Grand Fleet: Warship Design and Development 1906–1922

Burt, R. A. (1986). British Battleships of World War One.

Campbell, N. J. M. (1978). Battle Cruisers. Warship Special. 1(Conways)

Campbell, John (1998). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting.

1st Baron Fisher: Fear God and Dread Nought: Restoration, Abdication, and Last Years, 1914–1920

Goldrick, James (1984). The King’s Ships Were At Sea: The War in the North Sea, August 1914 – February 1918

Newman, Brian (2019). “Battlecruiser Tiger: The Arrangement of the Main Engines”.

Roberts, John (1997). Battlecruisers.

Roberts, John Arthur (1978). “The Design and Construction of the Battlecruiser Tiger”

HMS Tiger specifications |

|

| Dimensions | 214,6 x 27,6 x 8,7 m (704x 90x 32 feets) |

| Displacement | 25 500 LT, 33 260 LT FL |

| Crew | 1121 |

| Propulsion | 4 shafts Brown-Curtis turbines, 39 watertubes boilers, 85 000 shp. |

| Speed | 28 knots (52 km/h; 32 mph) |

| Armament | 8 x 343, 12 x 152, 2 x 76 AA, 4 x 533 mm sub TT. |

| Armor | CT 9in (254), belt 9in (230), bulkheads 4in (100), barbettes 9in (230), turrets 9in (230), decks 3in (75 mm). |

Gallery

Author’s illu of the HMS Tiger in 1916.

A whatif appearance of the HMS Tiger circa 1942 if kept in service and modernized in the late 1930s: Dual purpose 4-in guns, improved mounts allowing 30° elevation, AA battery of Bofors octuple mounts, single 20 mm, RL on the upper turrets, new 8 new boilers with all-oil firing, trucated funnels, rebuilt bridge, new ballistic computer and FCS, improved vertical armor, ASW bulges, aircraft (no hangar) and radar. Capable of 30 knots despite the addition of armour, new structures and AA, a potent addition to the Royal Navy. (Both illustrations by the author)

Various renditions on world of warships

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign