Introduction: The legendary Armada

The Spanish Empire was once the largest in the world, long before the British Empire, fleets of powerful galleons, military cargo ships, crossed the Atlantic to bring amazing levels of wealth to the Spanish crown, following the establishment of Spanish colonies in the Caribbeans, then South America. Not only this trade bring trade to new heights, and commerce raiding in the age of corsairs, then piracy, it also made the Armada the largest fleet in the world. The peak of it was Philip II of Spain fleet launched to conquer the British Isles pitted against Elisabeth I and her rebellious nation in the name of the “true faith”.

The Spanish Empire was once the largest in the world, long before the British Empire, fleets of powerful galleons, military cargo ships, crossed the Atlantic to bring amazing levels of wealth to the Spanish crown, following the establishment of Spanish colonies in the Caribbeans, then South America. Not only this trade bring trade to new heights, and commerce raiding in the age of corsairs, then piracy, it also made the Armada the largest fleet in the world. The peak of it was Philip II of Spain fleet launched to conquer the British Isles pitted against Elisabeth I and her rebellious nation in the name of the “true faith”.

Articles covered

- Emperador Carlos V

- España class Battleships (1912)

- Pelayo (1887)

- Princesa de Asturias class cruisers (1892)

- Alfonso XII class cruisers (1887)

- Aragon class cruisers (1879)

- Destructor (1886)

- Infanta Maria Teresa class cruisers (1890)

- Isla de Luzon class cruisers (1886)

- Pelayo (1887)

- Reina Regentes class cruisers (1887)

- Velasco class cruisers

Articles upcoming

Rio de la Plata (1898)

Estramadura (1900)

Spanish Torpedo Boats

Spanish Sloops/Gunboats

Destructor class (1886)

Temerario class (1891)

Torpedo Gunboat Filipinas (1892)

De Molina class (1896)

Furor class (1896)

Audaz class (1897)

Spanish TBs (1878-87)

Fernando class gunboats (1875)

Concha class gunboats (1883)

Legend has it that for this fleet, large forested areas of Germany within the Habsburg Empire, and Belgium, after those of Spain, were cut-off. This 1588 “great armada” comprised 22 heavy galleons of Portugal and Castile and 108 armed merchant vessels (mostly Fluyts and pinnaces) with 4 war galleasses of Naples. This was not that of a juggernaut compared to the British fleet which counted 34 warships and 163 armed merchant vessels. British Warships were recent (new class inaugurated in 1573), nimbler and more agile, and a full blow battle at Gravelines, the use of fire ships and a storm striking the fleet on its great cruise around the British Isles and off Ireland condemned this enterprise and had important consequences for the gradual decline of the Spanish Empire.

Nevertheless, Spain was still a major naval power in 1805 and its alliance with Napoleon meant both fleet was more than a match for the British fleet, at least on paper. After Trafalgar, hopes for the Armada were gone, and the Royal Navy domination coincided with the consolidation of the British Empire and the gradual demise of the Spanish Empire, soon deprived of most of its South American possessions following a long list of Bolivarian revolutions.

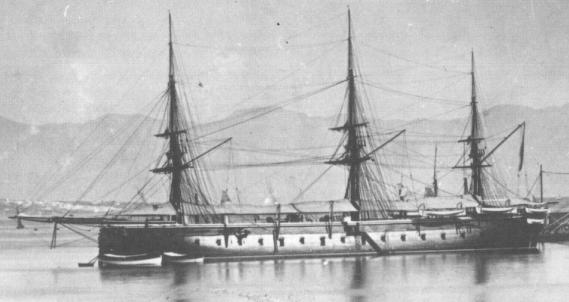

Ironclad Arapiles

One of the most powerful fleets in 1874

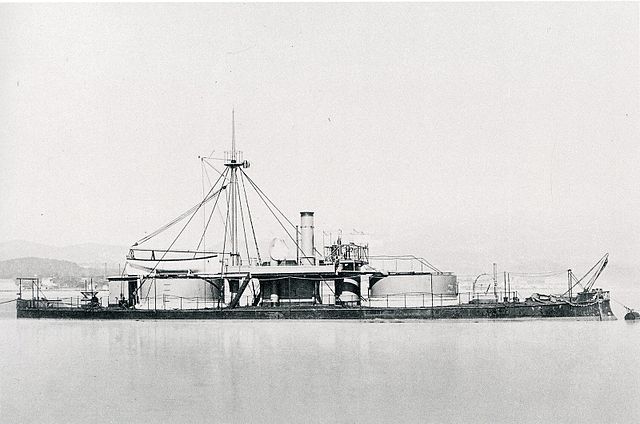

By the 1860s, the Spanish Empire still clung to still numerous overseas possessions and despite political troubles and instability at home, long periods of peace allowed to maintain a fleet just barely able to cope with the challenge; Thre screw frigates (Asturias, Berenguela an Blanca) and five screw sloops, and 29 paddle frigates and gunboats, plus a sailing fleet of two 86-guns ships of the line, four frigates, four corvettes, and 25 smaller vessels of all ranks. Large steam frigates were under construction, the Conception and Lealtad, in 1860. But soon Spain was one of the early adopters of broadside ironclads. After the French-built Numancia and Spanish-built Tetuan (1863), the British-built Vitoria (1865), Arapiles (1864), were followed by the Spanish-built Zaragosa (1867), Sagunto (1869) and Mendez Nunez (1869). Spain also had a monitor, the Puigcerda (1874) and the Duque de Tetuan, a floating battery of 1874. All these ships saw action in the Carlist wars. This gave the Spanish fleet in 1874 a seven ironclads-strong core, above the Turkish Ottoman fleet, and well above the recently created German fleet or the small Austro-Hungarian navy.

Floating battery Duque de tetuan, 1874

Spanish Monitor Puigcerdá

All were armed with Hontoria guns, licenced versions of the Pallister, Canet, and later the purchase of Parrott, Armstrong, and Krupp cannons and Schwartzkopf torpedoes. Sinificant events during that time were the Peruvian-Chilean war, and Cadiz mutiny of 1868, which had a deep political impact on the country, a bit like the Potemkine much later in another context. During the civil war at some point factions had their own squadrons. However the one boasted by Carthagena was seized by radical republicans. By 1874 order was restores as the Monarchy but the Virgina affair almost bring Spain to the brink of war with the USA. Indeed, an insurrection had started in Cuba since 1868 and a steamer bound to Cuba was seized by the Tornado, believing it was loaded with weapons and aid to Cuban rebels, including mercenaries.

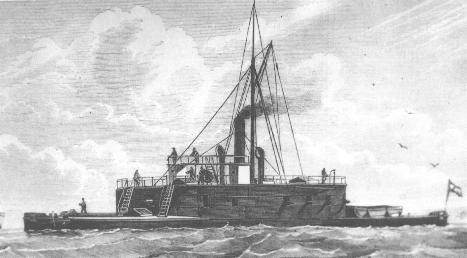

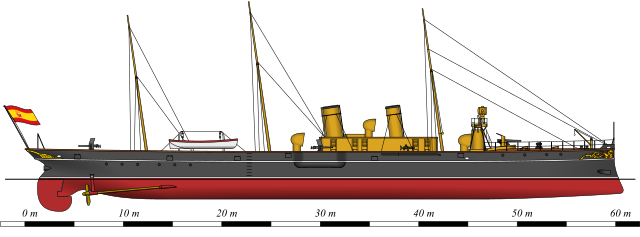

Desctructor in 1900. Arguably the first destroyer (1886) – Wikimedia Commons

As a consequence, the British and American crew was shot. Despite a settlement was found in 1879, this fuelled a resentment that was going to erupt after the USS Maine explosion in Havana by 1898. Meanwhile, the Spanish fleet was reinforced by an array of new ships, the battleship Pelayo in 1887, five armoured cruisers, and 20 protected and unprotected cruisers. Spain also tried the concept of torpedo gunboats, with 12 ships in the 1880s, and was an early adopter of the concept of destroyer, with the Furor class in 1896 (British-built) and several others as well as torpedo-boats from many shipyards. Sloops and gunboats were also numerous, used for colonial stations. But the 1898 war shattered all the restored confidence in the fleet, which was impressive on paper, superior to the USN.

Situation of the Armada Española after 1898

From the rank of a powerful navy, although second-rate in 1898, still possessing an empire, Spain emerged from the “splendid little war” with the loss of Cuba and the Philippines (most of the Empire remaining), and was amputated from the bulk of its overseas fleet. The latter was already aging in 1898, and lack of new constructions meant the Armada was largely obsolete by 1906. There was no longer any consideration to restore the Armada anyway. In November 1907, however, the Cortes (parliament) voted a new naval plan. This law of January 7, 1908 detailed the major projects on three points: The first was the strengthening of the industrial capacity of the Spanish shipyards. The Naval Ship Sociedad Espanola (SECN) was founded for this purpose. British shipyards were ordered to enter the capital of this company at 40%, including Armstrong, Withworth Ltd., John Brown and Co., and Vickers Ltd.

Five shipyards were thus reinforced, with new additions, and worked on for the future needs of the armada: Ferrol, Cartagena, Cadiz, Bilbao, and Santander. Engineers and even English shipyard managers were hired in these companies to supervise the staff. Thus equipped, these shipyards were tasked to create the “new armada” a fleet of modern ships fit to protect the homeland, short of colonial dreams, and modelled itself on the Royal Navy, the old historical adversary. The second part of the plan stipulated that the SECN consortium also set up foundries for armor, sheet metal and artillery. The third part ordered the construction of 3 battleships, 3 destroyers, 24 torpedo boats and 4 gunboats. Just as the Armstrong shipyards greatly influenced the production of the cannons and turrets of the new battleships, French Normand was entrusted for torpedo boats, which up to that point were a collection of worn-out coastal boats dating back from before the 1898 war.

The experimental Isaac Peral, first electrical submarine (1888) by famed engineer of the same name, Isaac Peral y Caballero (+ Berlin 1895). He has been fed up with the incury of Spanish naval staff

And by chance, this plan came to an end in 1914. In fact, by that date, the Armada had to be totally modernized. In 1913, when the first came to its conclusion, a second plan was set up for the construction of three other battleships of 21,000 tons, 2 light cruisers, 9 destroyers, and 3 submersibles. Two naval bases were to be developed to ensure the reception of this second squadron in the Mediterranean with Ceuta (Morocco) and Port Mahon in Menorca in the Canaries for the Atlantic. However, the upgrading of the shipyards and the industrialization of the SECN took time, so that in 1914 the ships planned for the 1907 plan were not yet fully completed. As a result, the Armada’s workforce was further strengthened by many older units awaiting retirement. So this gave a total of two Dreadnought Battleships, 11 Cruisers, 11 Destroyers and 26 miscellaneous ships, which made an Armada a force to be reckoned with again.

Reina regente, the most modern Spanish cruiser in WW1, here in 1912.

Strenght of the Armada Española in 1914

2 Dreadnought Battleships: Dreadnoughts: 1, class Espana. (1912, Alfonso XIII and Jaime I in completion or construction).

1 pre-deadnought Battleships: Pelayo (1887).

11 Cruisers: Reina Regente (1906), Estramadura (1900), Rio de la Plata (1898), 2 class Cataluna (1896), Emperador Carlos V (1895), Lepanto (1892), Alfonso XIII (1887), 3 class Infanta Isabel (1885-88).

11 Destroyers: Recent: 3 Bustamante class (1913). Older ones: 4 class Audaz (1897).

9 Torpedo Boats: Type No. 1 Vickers-Normand (1912), 7 operational units in 1914, 15 more under construction. Older; 2 class Hazor (1887).

17 Miscellaneous: 4 gunboats of the Recalde class (1910-12), 8 torpedo gunboats: 5 Temerario class (1888-91, including 2 in the process of withdrawal of service), 3 Dona Maria de Molina class (1897). 3 Cortes class (1895), Large sea going gunboats Cartagena (1908) and Perla (1887).

The old Numancia (1863) survived the post-1898 unlistings and was struck in 1912.

The Vitora (1865) was the last ironclad of her generation, also discarded before ww1, in 1910 to 1912. The Tetuan (1863), Arapiles (1864), Zaragoza (1867), Sagunto (1869) Mendez Nuñez (1869) has been retired and not modernized.

The Armoured crusier Emperador carlos V suvived the war of 1898. In 1914 she was present at the United States occupation of Veracruz.

The French-built 1880s barbette ship Pelayo was one of these ill-fated jeune ecole designs. in 1914 she was in reserve due to their age and much more capable dreadnoughts that needed manpower.

The Spanish Navy during WW1

With war breaking out, Spain remained neutral, and for the additional reason that in case of conflict its fleet was not ready, then in the midst of modernization. The construction of three dreadnoughts had been delayed, and if Alfonso XIII and Jaime I had been launched in 1913 and 1914, the first was not completed until August 1915 and the second had to wait until December 1921. Moreover, the other three battleships planned for the 1913 program (Reina Victoria Eugenia class) were not even started. Three light cruisers were started at Ferrol Shipyard in 1915 and 1917, the Reina Victoria Eugenia and the two Mendez Nunez class, but the first was completed in 1923 and the other two in 1924-25.

The destroyers of the Alsedo class were not started until 1920. The reason for these delays was due to the fact that British shipyards were mobilized for the benefit of the Royal Navy alone, and that parts and competent engineers had returned back home to work in domestic programmes, while supply from the UK was cut off. In all, ships delivered in 1914-18 were Battleship Alfonso XIII in 1915, Submersible Isaac Peral, and three Class A submarines plus eleven torpedo boats.

The cruiser Cataluña in 1914

Although neutral, Spain was politically divided on the question of what side to choose. Its conservative, Catholic and aristocratic majority favored central empires, while part of the political class (republicans and liberals) and the majority of the people were rather favorable to the entente. The latter begged the Spaniards to carry out a stricter control on the entry and exit of ships and personal coming from Germany in its waters, especially in the Canary Islands, where German presence was quite important, but also in the Mediterranean, where German privateers found temporarily refuge. With the development of submarine warfare, many U-Bootes were interned, especially as a result of systematic attack on fruit trade for the allies that passed through these waters, and all were given to the allies after the armistice. But an agreement that compensated for the loss of 260,000 tons of shipping sunk by Germany by granting Spain 7 ships was not recognized after the war and Spain never recovered the tonnage lost, if not by many new constructions. In 1914, its commercial fleet comprised 479 steamers and 80 tall ships for a total of 443,000 tons. After the Great War, Spanish forces were committed to the Rif war in Morocco, and the fleet was reinforced again in the 1920s (see above).

The 1916 Isaac Peral being launched.

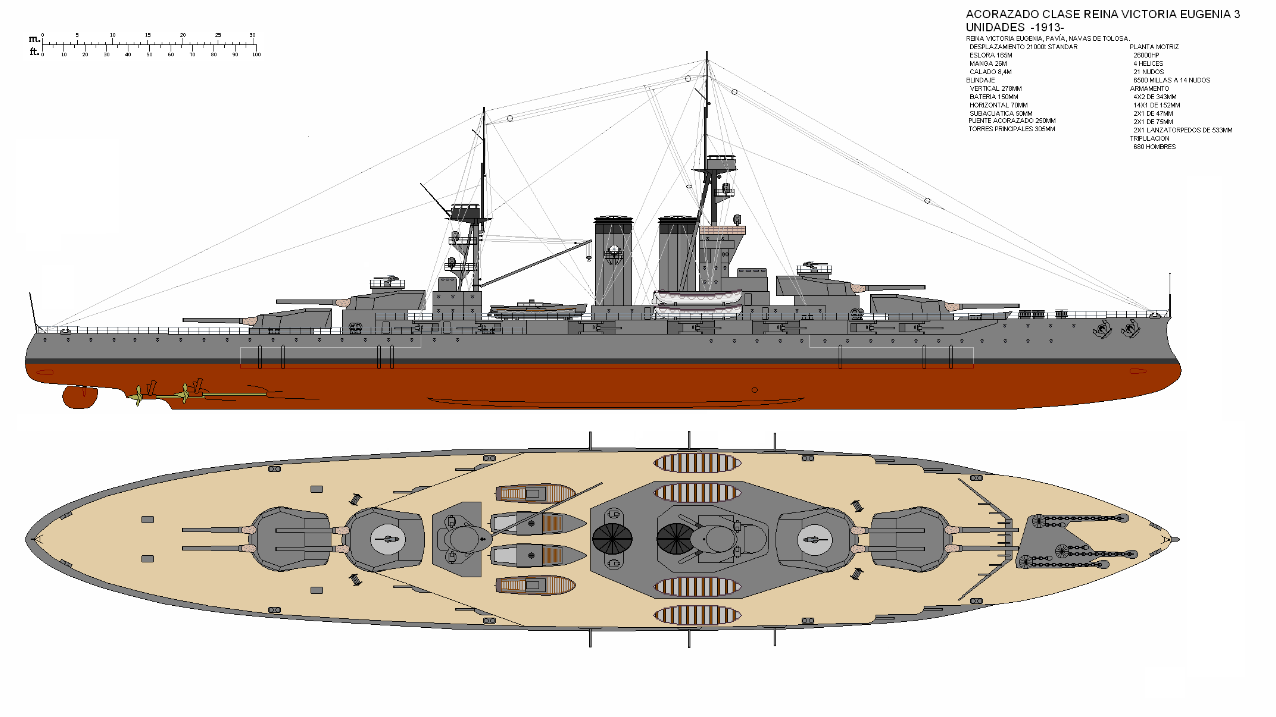

Paper battleships: The Reina Victoria Eugenia (1913)

With the Espana class, Spain joined the restricted club of dreadnought makers which counted the UK, USA, Germany, France, Italy, Austro-Hungary and Russia. Imperial Japan’s own dreadnoughts were built in the UK, and it was almost the case for the Espana class; Although all three were built at SECN, Ferrol with Spanish specifications, they were the product of a consortium largey dominated by British forms: Vickers, Armstrong Whitworth, John Brown & Company that formed the Sociedad Española de Construcción Naval (SECN). New 184 by 35 m (604 by 115 ft) drydocks and two 180 by 35 m (591 by 115 ft) slipways were buit at Ferrol for these, that can serve for larger ships if the budget allowed it. Delays ensured the Espana class three ships were not in service in time: One prior to 1914, one in 1916 and the last in 1921. The latter was obsolete as in between, the super-dreadnought type was already in favour. A second Navy Law of 1912 (Plan de la Segunda Escuadra) planned indeed the building of three other ships to supplement the Espana class. They were later called the Reina Victoria Eugenia class and planned to be laid down in 1914 and 1915 for a completion planned for 1920.

Probable appearance of the Reina Victoria Eugenia if drawn, author unknown – from the-age-of-navalism-1890-1918 forum civfanatics.com thread.

The admiralty took advantage of the rapid progresses made by UK and other nations in artillery caliber and configuration, speed and armour schemes. The guns were likely to be delivered from UK, and many other parts. Like the Espana, the new class consisted of three ships, Reina Victoria Eugenia (King Alfonso’s English wife), and two others named B and C. Designed by Vickers-Armstrongs they were planned to displace 21,000 long tons (21,000 t) with a top speed of 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph).

First draft called for four twin turrets with 15-inch (380 mm) guns but budget constraints led to a selection of four twin 13.5-inch (340 mm) guns instead. Secondary armament was twenty 6-inch (152 mm) guns in barbettes. Although there are no blueprints known, their probable appearance would havebeen of contemporary british ships like the King Georges V or Iron Duke with two funnels and superfiring turrets in the axial plan (without the central turret). Also significant foreign technical assistance was required but the outbreak of the First World War led to long delay for the España class as seen above and pure and simple cancellation of the Reina Victoria Eugenia.

Postwar, Spain was not signatory at the Washington Naval Treaty, and therefore not tied to any restrictions. But budget constraints and new priorities for the army at large (also an obsolecent design) meant they were never approved. Later in the interwar Spain considered also the Scharnhorst and Litorrio designs. And super-cruisers like the well-advanced Ansaldo cruiser. But that’s a part of the upcoming interwar and WW2 Armada.

Blas de Lezo, one of the three postwar British-built “town” class cruisers in 1923-25, which saw the civil war and undergone massive refits.

Sources/read More

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_battleships_of_Spain

Official Armada Espanola website, History section

Destructor (1887), the first destroyer (ES)

Google Books Spanish Naval Power, 1589-1665: Reconstruction and Defeat

Google Books Destroyers of the Spanish Navy LLC Books

Spanish Royal Academy of Naval Engineers (VDM Publishing): Lambert M. Surhone, Miriam T. Timpledon, Susan F. Marseken

Conway’s all the world’s fighting ships 1860-1905 and 1906-1921

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign