Industrial Era Ships & Tech

Since the XVIIth Century, steam began to appear as a feasible new source of energy. In the XIXth more engineers will add their science to bring new innovations into the fray, from the torpedo to the submarine and turbine.

INDUSTRIAL ERA TECH, PIONEERS & ENGINEERS

The century of the Industrial Revolution is also the course of a plethora of pioneers, engineers, architects, inventors, that have disrupted the lives of millions of people by developing machinery. Getting rid of horsepower and manpower has been the focus of many “engineers” since antiquity. Hiero of Alexandria was probably the father of all pioneers in steam power. As early as 50 or 60 AD, he designed the very first practical steam engine, while converting steam to motion in a very simple and compact design: The Aeolipile. However this last has few applications yet but the principle was used to build fancy devices used to produce special effects, notably in temples…

Ideas of exploiting steam power flourished during the renaissance. Even the great Leonardo da Vinci worked on a “rediscovered” marvel of ancient times : Archimedes steam cannon. But it was not before the XVIIth century that those ideas were really put to the test, and far more time before any application on a floating device, other than for show. In The old traditions of the wooden Navy partly explain the very slow transition period that will waive shipping sail only for steam only : The first commercial steamship appears as early as 1810, but the last sailing cargo ships do not disappear until about 1930. Below follows a list of famous engineers, being set up.

Pioneers Engineers of steam

Steam engineers in naval history

INDUSTRIAL ERA NAVAL TECH

Steel industry: The great revolution of naval artillery

Steel for example, originally embryonic, becomes accomplished to the point of allowing the melting of metal plates of large dimensions, ad also making larger shells, and duplicate more easily all the parts associated with a specific machinery. The traditional timber could’nt satisfying anymore any fleet because of its own limits of endurance loads, heat, moisture… The steel industry also made it possible to design composite plates of different metals and alloys, hence the origin of the very first composite armor plates which were the mainstay of the Ironclad era.

More importantly, the techniques of modern fondry bring a marked increase in quality for lower price. Thus, it was common for the guns to crack and explode in the eighteenth century, depending of their origin. It is estimated as well as the quality of the original molding template, it could take a number of lined before reaching their limits of strength and become dangerous to their users. With the science of modern steelmaking, more longer guns were produced, while being more reliable and durable, playing on the assembly of parts to create a recoil brake already built into the structure of the canon, to adding an alloy core more resistant to heat, and especially to create a trustful mechanism for breech loading. Tactical advantages were obvious : Breech loading was easier and faster in the heat of battle, range was greatly increased, now reaching ten miles and more, and maintenance was also easier.

The passage of the SBML (Smoothbore muzzle loading) to the RML (Rifle muzzle loading), to the RBL (Rifled Breech loading) was effective around 1850, altoough many ships in 1880 still bear both RML and RBL. At that time, the first drying breech guns were still unreliable and many gunners had serious suspicious of it. But the conservatism ended with the development of these, and from an elite minority alongside the muzzle-loading, have become the majority, and in 1865, the exclusive dotation of any warship, in any caliber.

The process of rifled barrels was already ancient and had the function of the projectile to rotate very fast, as resulting in better penetration into the air: The result was that same length and same caliber guns became both increasingly accurate, and with greater range. But as they were still few armouries capable of producing such gun (one by country-only speaking of the greatest at the time), they were expensive and generally the biggest guns on board, only two or four of these being produced per ship.

Gunnery improvements

The classical smoothbore gun in use since the time of the Renaissance was built of rough casting in bronze or iron, usually garnished with side handles that were used in fact to its handling by pulleys, on a natural lever point. The cannon bore was sometimes constituted of a different metal, treated to be more resistent, an early attempt of composite guns. The gun was based on a mobile carriage (in depth) consisting of a wooden base mounted on wheels on which rested two media surrounding the tube, resting on cylindrical bulges at the base of the barrel. The Canon was aimed thanks to a primitive wedge-shaped wooden insert at its base, just hammered more or less. The recoil was reduced through a combination of wheels on the lookout and its attachment to the internal wall of the battery by a system of pulleys (brague to hoists), which deadened the energy released when firing.

The recoil of the barrel was calculated for the team of gunners to reload the mouth, to relent operation that requires hoists for the fall even in the middle of the bridge battery, a pre-cleaning with the swab, “sweeping” the tube to extract soot and deposits resulting from combustion, and the laying of the loose powder wrapped in a canvas bag pushed to the bottom of the barrel, loading the ball in the same way, then re-positioning by traction the whole lot to the wall by pulling on the hoist of Brague, and then reloading the flint hammer. Because of the dangerousness of the blow to the GPO, the latter, after setting up, by pressing the corner to the desired depth with a mallet, retreated and pulled on the rope that freed the dog. It was also customary in a heavy fire to throw buckets of water on the barrels of the guns, an ever dangerous operation because the under the thermical schock, the already developing cracks in the barrel could result in an explosion in the face of the crew on the next shot. It was also used to spread sand on the deck so that men do not slip on the blood of victims of splinters, the main result of the impact on even a thick wooden composite wall…

The whole operation took about twenty seconds on average, but officers were trying to bring batteries that number to fifteen or even twelve to respond more quickly to the adverse ship. Some dashing and able captains, even made hard-turns, allowing them to use their opposite broadside. Some extreme-aiming methods included the removing the rear wheels of the carriage to further increase the rise, especially when it came to get the opposite ship dismasted (to fire over the battery on the basis of masts, or cut the rigging with the infamous chain-shot).

Standard shots were sometimes replaced by a hotchpotch of pieces of iron, grapples, or grapeshot against the crew and riflemen of the enemy ship. For each gun, five to nine men were necessary, which explains the importance of crews piled on sixty meters of a vessel. The lateral aiming of the broadside was limited, the ship was simply steered around towards the goal, and usually lost the use of the battery from the other side during classic engagement (although, as specificed above, smaller and more agile vessels can compensate their lighter broadside by just swapping sides, allowing the other to reload).

The classical tactic of the “line” of battle, ships following and fighting at close range (less than 500 meters due to the very poor accuracy of the guns), and the origin of the “ship of the line” class, then passed to the “battleship” class in more modern way is meant to cook during the Second World War. One of the favorite tactic was to try to outflank the back or front of the queue to move opposite to the other side and thus make use of its other broadside, while keeping the line. Pass astern of a ship was also a tactic to destroy its rudder, paralyzing it at the same time. Nelson favorite tactic, usually in numerical inferiority, was to create a local numerical superiority by sending his ships in two parallel lines on each side of the enemy line. This “sandwiched broadside” tactic was a gamble : dealing with the biggest enemy ships – including the flagship, and have all of them destroyed, and the entire fleet was supposed to collapse. This was the case both at Trafalgar and Aboukir.

Revolution in gun aiming : Turrets and Barbettes

With the progress of the industrial age, the gun will change considerably during the 1870s, several successive revolutions: First, thanks to new alloys, including steel, machine guns could be fitted with a cylinder head opening. The moving parts makes it possible more or less than loading projectiles breech. The loading operation was thus significantly facilitated and the decline of the room did not need to consume an important place in the bridge battery. But he still had many detractors and not really required until about 1890. Another innovation was to place the cannon on a swivel looking metal side. We asked this because looking on rails in the halfpipe, which enabled the roll in position angle of 80 to 90 degrees, compared with the previous zero angle guns. Swivel guns and allowed the ship to keep its road and to fire or is the goal. And we are moving to a smaller number of guns, but orientation and larger caliber, which would give the central battery ironclads.

It must be on site Columbia Elswick Armstrong and English engineer Ericsson inventing a new type of brake down more suitable, consisting of metal strips placed on the rails Parallel and friction with other vertical stripes constitute the look-out and a mechanism to allow channels to put the unit in place, but everything was still working at the force of arms. With guns than twelve tons, it was appropriate to consider another solution: We will then proceed on hydraulic brake and not mechanical, and secondly, for pointing to the solution of the watch mobile turn, the forerunner of the turret. In 1861, the United States, the Stevens brothers had devised a battery of high seas with fully adjustable mounts on guns in all directions. This brilliant precursor was not followed.

By John Ericson against the Americans proposed a “turret” avant-garde as gun carriage and turned all screening. This leads to the ship that becomes universally known minimalist: the monitor. This system, however, was quite heavy because the turret was placed on a shaft and rested on the bridge, it was a powerful mechanism for the hydraulic lift and rotate to the desired angle. In turn, the Englishman John Coles, commander of active conceived and proposed an improved turret system. The principle remained the same, but the turret rested permanently on the bearings, which simplified its rotation. Faced with the skepticism of the British Admiralty (short term), Coles offered his invention to the Danes who adopted it for their monitor Rolf Krake in 1864. The French in turn, used a system but also turning barbette, the screen is quite low and the gunners were not protected. But this system conut long success through simplicity in particular to ensure the loading maneuvers.

The site was then Elswick Armstrong-simplify and refine pointing maneuvers, loading guns, by inventing a system based entirely on water power rather than steam. By 1890, this system became the majority, and radiation technique (and commercial) would give the site a large majority position in the production of naval ordnance, and shipbuilding itself. The quality of the British steel industry was also profier to the melting of parts much longer: The “size” is the measure of length comparison between the fly (length of the gun tube from the base of the cylinder head to the mouth), and diameter. And 1850 guns with calibers from June to August, they went to 20 gauges around 1875. This siginfiait also through the introduction of shells, a much greater range, from less than 1000 meters to over 5000. With heavy-loading cannon’s mouth who survived still remained the problem of loading, which was solved with creative solutions and varied: for example, are oriented in a transverse position on the lookout sets, and switch on the fly was down so that the bolt is in the air and the mouth in the bridge battery. we also put a system of lift, or all bolt-gun-turret came down to a level …

About 1895, they began to move away from barbettes poorly protected against fire for oblique and full towers are especially concentrated on a loading system allows to do this regardless of their angle of fire. The loading system evolved, as shells were now lifted from the ammunition storage rooms by a system located in the axis of the turret. The shell and cartridge (powder charge usually surrounded by paper) was then brought by a chariot or a reinforced mat. Then, early in the century, innovation is still possible that loading at any angle, expanding down the entire turret. This system is still in use on the modern automated turrets.

Ammunitions: From cannonballs to AP shells

Another fundamental innovation, initiated in 1860 concerned the ammunitions: Navies dropped the cannonball and its derivatives such as Paixhans explosive special grenade. The latter, invented by engineer Henri-Joseph polytechnician Paixhans is neither more nor less than the precursor of modern HE shells. It was established in 1819 and proposed to a commission of officers and technicians of the Army. But it was not until 1854 that Napoleon III, after the death of the person concerned, decided to build three armored batteries illustrating his theories successfully. Long before Paixhans, Carron invented the famous “carronade” naval guns firing angle firing explosive bullets. It was a resurgence of neither more nor less than the spread of mortars in use on marine galiots since the seventeenth century. Nevertheless Paixhans brings the power of explosive projectiles form studied and the ability of these guns to shoot horizontally. Rockets were also used in naval warfare, and cannons could be loaded by chained cannonballs, red hot ones, or canister shots to precede a boarding.

The “bombs” more or less spherical and hollow, came to form ballistic shells studied from 1870. It is the latter, which combined with a scoring of the bore and longer length of the fly will move progressively from 20 000 to 40 meter range 000 of the first to the second world war. The shells of modern rooms are equipped with large deployable wings and provided with additives that brought charges that distance over 100 km, not counting the giant guns recurrence projects since the beginning of the century and the nineteenth century (the gun running the rocket “from Earth to the Moon” by Jules Verne).

First steamers 1801-1819

Any invention has many fathers

The Aerolipile was the earliest known attempt to devise a practical steam engine. This simple device created by Hiero of Alexandria in Hellenistic Egypt turned steam to a rotating motion in the 1st century AD. However there was no real control, and despite the speed of the contraption, brute horsepower was negligible. However some archeological researches and text re-reading (plus the amazing discovery of the Anthykitera mechanism) went as far as pretending the Greeks used routinely steam power to open doors or create special effects in Temples, 2400 years from now, not to mention Archimede’s “steam cannon” purposely built during the Siege of Syracuse.

The Aerolipile was the earliest known attempt to devise a practical steam engine. This simple device created by Hiero of Alexandria in Hellenistic Egypt turned steam to a rotating motion in the 1st century AD. However there was no real control, and despite the speed of the contraption, brute horsepower was negligible. However some archeological researches and text re-reading (plus the amazing discovery of the Anthykitera mechanism) went as far as pretending the Greeks used routinely steam power to open doors or create special effects in Temples, 2400 years from now, not to mention Archimede’s “steam cannon” purposely built during the Siege of Syracuse.

In any case, this new form of energy was (re-)born after the intellectual bubbling of the Enlightenment. Despite the absolutism, such engineering was well seen by Royal power, especially in France. Experiments went in just about every field and names like Denis Papin and his steam digester, Faraday, Thomas Newcomen, Thomas Savery.

James Watt’s engine animation

The French Cugnot created the first “steam trolley”, great-great ancestor of the automobile. A steamboat was described and patented by John Allen in 1729. James Watt was the first to adapt a steam engine to a ship and transmitted the force (still derisory) to the rotation of two-wheeled blades, the first naval paddle wheels. William Henry of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, made an engine and tested a steamboat in 1763. Twenty years after, he probably inspired D’Abbans Pyroscaphe. This will initiate exactly at the dawn of the nineteenth century an industrial revolution that will change the face of the world and make it a much smaller place.

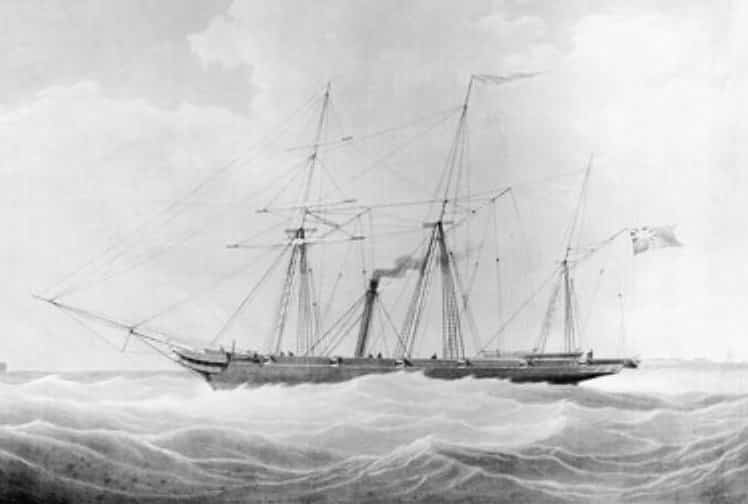

1836 British patent for a steamship.

It will take another thirty or forty years before the steam was serviced daily in navigation. The regularity brought by steam power, this autonomy towards meteorology, was the only great revolution in naval transport, and will enable modern passenger transport.

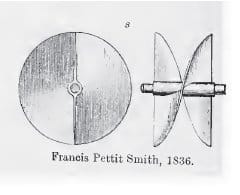

Francis Petitt Smith patent for a screw propeller, 1836.

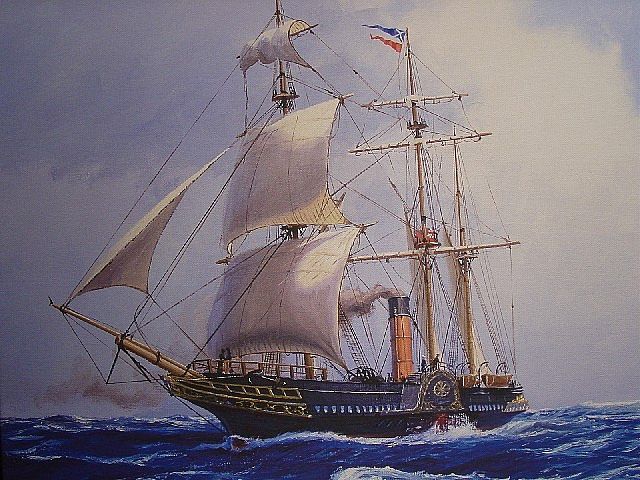

The mixed vessels sail/steam would become be a reality despite certain mistrust and strong traditionalism, conservatism of the maritime sphere. The “steam-only” ships from Fulton in 1801 were the few that followed were seen as a bit radical, as this new power took decades to reach reliability and power, both in the civilian and military fields. Until at least 1885 ships had been using a mixed solution. Although they were accepted for regular lines on the civilian lines from the 1830s, Navies only adopted it past the 1850s when the Crimean war broke out. That was only for the arrival of the propeller screw, since fragile paddle wheels were too unprotected for military purposes.

SS California, first Pacific line paddle steamer (1848)

First Steamers:

In short, here are the ships that will be covered:

First experiments by Symington, Fulton, Bell, and D’Abbans.

-Charlotte Dundas, Pyroscaphe, Clermont,Comet, Savannah.

-First Military Steamers like HMS Rising Star, Sphinx,

-American Paddle Steamers of the Mississippi.

SS Archimedes, the first screw-propelled ship.

First “packet-ships” (to come later)

- Archimedes (1838): first propeller liner

- The Great Western (1837): first regular line liner

- The Great Britain (1843): First liner with iron hull and propeller

Pyroscaphe (1783)

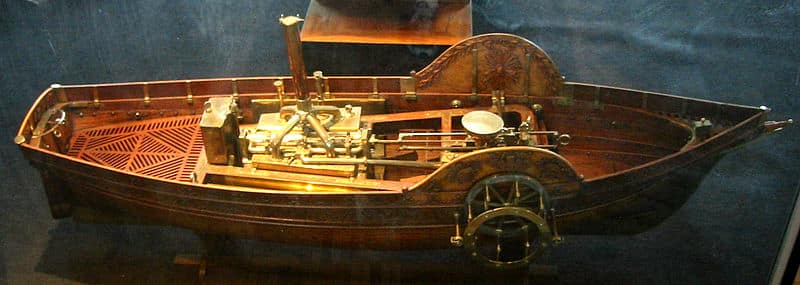

Undoubtedly one of the first steamers, the Pyroscaphe was a riverine adaptation of the Newcomen steam engine perfected by Marquis Claude François de Jouffroy d’Abbans. As early as 1774, the engineer had attempted to sail a first ship, but the engine was so weak that the current countered her action. Later, he made a much more ambitious new endeavour by scaling up his whole design. The large vessel (45 meters long) was propelled by a double action cylinder, and two large paddle wheels. Built by Antoine Frerejean, his crew consisted of just three. He made a first attempt on the Saone on 15 July 1783, but the machine stopped working after 15 minutes, putting an end to the project.

Charlotte Dundas (1801)

The first “operational” steamship. Not the work of Thomas Fulton, but of another late-century pioneer enlightment, William Symington. He had specialized in the mechanics of water mills, mine pumps, and had derived from it a compact, reliable steam engine. Means of propulsion he imagined was rather the vane wheel, in which a cylinder rotated via an articulated shaft, as early as 1793. His sponsor having finally retired from the project, his system remained without application for years until the Director of the Forth & Clyde Channel Co., Lord Thomas Dundas, was drawn via Captain Schrank who had devised a model of a tugboat equipped by the Symington machine.

Named after the director’s daughter, the tug was successfully tested in 1801 on the Carron River, after being revised and corrected with a new horizontal machine. The wooden vessel was 17 meters long by 5.5 wide with a draft of 2.4 m. The hull was cut open for the paddle wheel. The final ship was built in 1803 by John Allan and the machine by the Carron Co., making its first crossing with several officials on board including Lord Dundas, the project leader. Two months later, he towed two 70-tonne barges along the Forth & Clyde Canal to Glasgow, with an average of 3 kph, despite a contrary wind that stopped all ships making the same voyage. Proof was made of the reliability and efficiency of steam.

Despite this success, there were no other uses of the tug, as the company feared an erosion of the banks of the canal because of the waves raised by the ship. The Duke of Bridgewater, who owned a company on another canal, was also interested, but he died before the project could succeed. The Dundas was abandoned by its owner until 1861, when it was demolished, and Symington was never paid to match his personal investments. But this brilliant British pioneer had paved the way and inspired other engineers, including the American Fulton

Clermont (1807)

Thomas Fulton is now considered the “steam pope”, but in reality he was only one of the many engineers who, from the beginning of the eighteenth century, had boldly set out to discover the energy of steam. On the other hand, he was the first to design a viable steam-powered ship, in a history marked by disappointments, capsizing, fires, explosions… An American, Fulton was merely a pragmatic observer inspired by inventions that synthesized the best mechanical compromise.

Fulton’s Clermont replica.

Robert Livingston, a wealthy politician and investor from New York who obtained exclusive Hudson navigation rights and was invited to attend Fulton’s demonstration on the seine in 1803. Impressed, he signed with Fulton a first Contract for the construction of a steamship derived from its experiments.

Called first North River Steamboat, then North River Steamboat of Clermont, and commanded by Captain Andrew Brink, the ship made a two-day connection between Abany and New York. It had been built at Charles Brown of New York with British machines of Boulton and Bimingham Watt. It measured 40 m by 4.90 m with 2.10 m draft. He carried two masts rigged with sails in the third, in case his machines stopped working…

Welcomed with skepticism, the ship was nicknamed “Fulton’s folly” or “Fulton’s monster”. During her crossing, she was met by weary sailors onboard other ships but was cheered by the public massed on the banks all along its route. After such spectacular success, Fulton secured the construction of two sister-ships for their operating company, Neptune’s chariot, and Paragon, in 1809 and 1811. None of them knew of any accident, and they survived their inventor, who died in 1817. Commercial exploitation of steam navigation had just begun.

Comet (1812)

Henry Bell was a famous Scottish engineer, born at Tophichen in 1767, and one of the great pioneers of steam in Europe. In 1808 he moved to Helensburg, with the takeover of a public bath establishment managed mainly by his wife, because the financial security that it was procuring allowed him to go about his experiments on steam…

In 1812 he made for Sir John Wood & Co at Fort Glasgow Clyde navigation company a 13-meter steamship equipped with a 3-horsepower engine, named after the great comet that had been visible that same year in The European sky. She made her first trip from Greenock to Glasgow, boarding passengers, and inaugurating the first regular steam line in Europe.

One of the original features of his ship was that it had no mast, the chimney in place, to the point where a square sail on a yard and a jib were attached. Propulsion was carried out by sidewall impellers. In spite of a derisory speed and a contrary wind, the first crossing was a great success, which was followed by the establishment of new companies and new steamers in record time. The Clyde quickly became the most steaming river in the world. However, the Comet was re-engineered in 1819, but eventually failed on benches of Craignish Point near Oban which it served. The Comet II, built in 1820, hit the steamer Ayr near Gourock in 1825 and sank rapidly, with its passengers and crew, making 62 casualties. This drama marked Bell deeply and prompted him to withdraw from the world of steam.

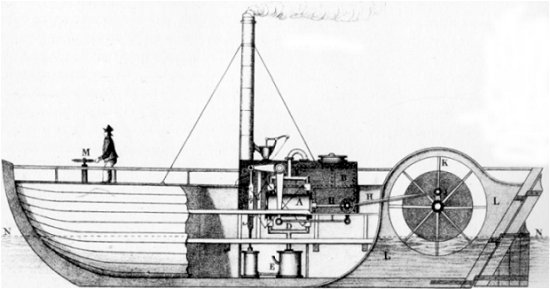

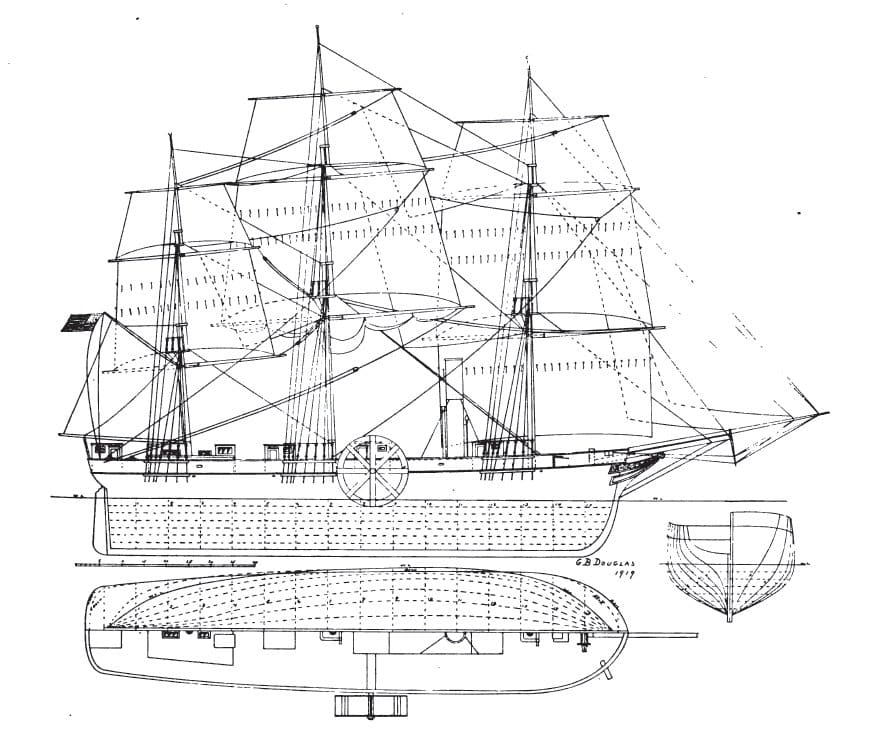

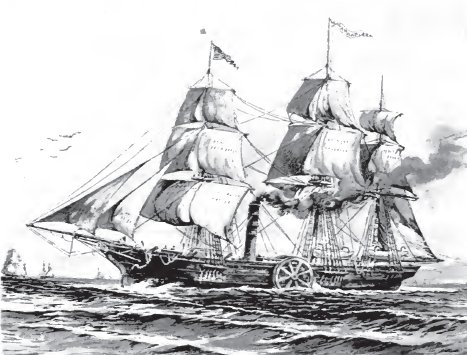

Savannah (1819)

This steamer, which can be considered the first transatlantic, was the common invention of the engineer Stephen Vail, who had worked with Stephens and Fulton, and Commander Moses Rogers, a visionary vapor-friendly. The two men founded the Savannah steamship Cie around the dream of building from operating the first transatlantic ship. Revolutionary, the ship was in relation to the vapors of his time in the sense that it retained the classical mature of a single-passenger ship of the time, its machine being seen as “auxiliary”. In this way, the sail carried out the main part of the propulsion, the machine taking over as soon as the wind conditions were no longer favorable.

It also saved space thanks to the lower quantity of coal on board, but also a regularity of service which opened up new prospects for commercial shipping. Finally the concept was relatively safe at the time or explosions and machine breakdowns were commonplace.

Built by the Fickett & Crockett shipyard in Corlears Hook, New York, the fairly conventional vessel had a slightly larger draft, which meant only 30 meters long for 8 wide and 320 tonnes. Modest, but the customers paid dearly for such a crossing, faster than any other ship, in facilities of a luxury novel at the time, only equaled by some yachts…

Its funnel top was steerable according to the wind force, in order to prevent its smoke from blackening the sails and its wheels actuated by chains, disassembled and placed on deck in case of sailing on wind power alone, their pivot and moorings being removable in the hull. Rogers, who was a mechanical enthusiast, took a close look at the construction, inspecting with great attention every piece of the machine built at Boulton and Watt in England, then the most famous firm in the world.

At the end of February 1819, the steamer made his first tests with a great success. The concept seemed validated for its promoters. On March 28, the ship left Savannah for her home port in New York, receiving enthusiastic press acclaim and President Monroe’s visit with War Minister John Calhoun. The former suggested that the government should exploit her on the Florida line, but Cuban piracy at that time made considered this exploitation too dangerous.

On the commercial side, however, Savannah’s beginnings has been calamitous. She first failed to find a crew, frightened by the mixture of steam and traditional rigging, and the nickname given by many sailors of “steam coffin”. Eventually men were recruited in the city of new London, where the first master Stephens Rogers thought finding reliable men. The crew recruited, remained to convince passengers, equally frightened by the concept and mixture sail/steam, despite the comfort announced.

Finally on May 22, 1819, the passengers and crew aboard, the ship made her first trip, an inaugural journey that would take her from New York to England, Sweden, Russia. The little habit of seeing smoke in the middle of sails would cause an Irish station lookout to report a fire. An epic attempt was made to “rescue” the presumed lost ship, shooting warning shots to the prow, as reported in his newspaper commander Rogers. The arrival in Liverpool was warm, the press being more enthusiastic than the officials. The voyage had lasted 28 days, of which 18 had been steamed, the machine proving reliable, but the voyage duration time was greater than that of many sailing ships over the same distance. This was attributed to contrary weather. The ship was in fact twice as fast than on sail power on a calm day.

Diagram of the Savannah

The relative coldness of official authorities, was imputed to insistent rumors that the ship was a gift from the American government to the Tsar, or was to be rented by Jerome Bonaparte to deliver his half-brother from his long exile in Saint Helena. The arrival of the Savannah in Sweden was no Less enthusiastic. King Charles XVI (formerly Marshal Bernadotte) offered to buy the ship for $ 100,000, which Major Rodgers declined, estimating the total cost of the ship and its operation, far superior…

During her crossing to Russia in the Baltic, she enthused one of his passengers, Lord Graham, a famous general of Wellington. He was astonished by the speed with which the ship changed from “sailing” to “steam” mode in less than a quarter hour.

At St. Petersburg the reception was even more grandiose. The Tsar and his court made numerous “sea parties” and cruises aboard the ship. The latter made an unprecedented proposal, not even dreamed of by a Fulton years earlier: The exclusive commercial concession of Russian waters, from the Baltic to the Pacific. As a good family man, who wants to remain in his country, Rodgers declined the offer, not without regrets. On his return the ship passed through Copenhagen and Norway. But in the long run the SS Savannah was a commercial failure. No doubt the clientele was not ready.

SS Savannah from Chatterton

There were no other attempts at transatlantic operations on the part of the Americans before 1845 on comparable ships. Stephen Veil was never totally paid for the investments made, and the situation even worsened for the company, victim of the serious fire that devastated the city of Savannah. Attempts was made to sell the ship to the government, but President Monroe finally declined it. The ship passed under a new commander, but after two years of service she was grounded and permanently lost on Long Island reefs. Thus ended a glorious pioneering attempt, before the frenzy of “steamships” that will explode much later in the century, and was definitely going to revolutionize the crossing of the Atlantic.

Industrial Age Naval Warfare

This is content from cyber-ironclad.com, devoted to XIXth century naval warfare. The Era of Jules Verne and Brunel, of technological revolution. Ships moved from wood, broadside guns and sails to turrets, steel and steam.

Timeframe

The eighteenth century was a pivotal era for ships and ships warfare as well as in many other areas. It started at the dawn of the new century, with Fulton and other pioneer experiments and because over a period including ships built beyond any late eighteenth century to the early twentieth century (ending in 1905, years before the issue of Dreadnought), old fashioned tactics and relatively short range gunnery still prevailed: After all, Tsushima was fought at relatively short range in a classic broadside fashion.

Battle of Riachuelo

This section focuses on navies of the 1850’s to 1905, a timeframe able to classify many ships built, converted and sunk between. In fact, the historical episodes considered, it will also issue a navy punctual screenshot on a particular date.

Battle of Lissa, 1866, the great return of the ram

Timeline :

1805

Birth of steamships, by Scottish-born engineer Fulton. A serie of steam-only ships will appear until the development of mixed ships (sail and steam) from the mid-1920s; By the 1830s there were quantities of mixed ships in service on civilian trade routes, which bring time reliability whereas previous ones were tributary, like in the past, of the elements. The Navy at that stage only get interested by small, fast mixed corvettes used as despatch vessels, to carry orders and personal between ships of the line; Thick black smoke, dirty coal were seen a liability for a military ship. Until 1850.

Trafalgar: The last great ship-of-the-line battle.

1850

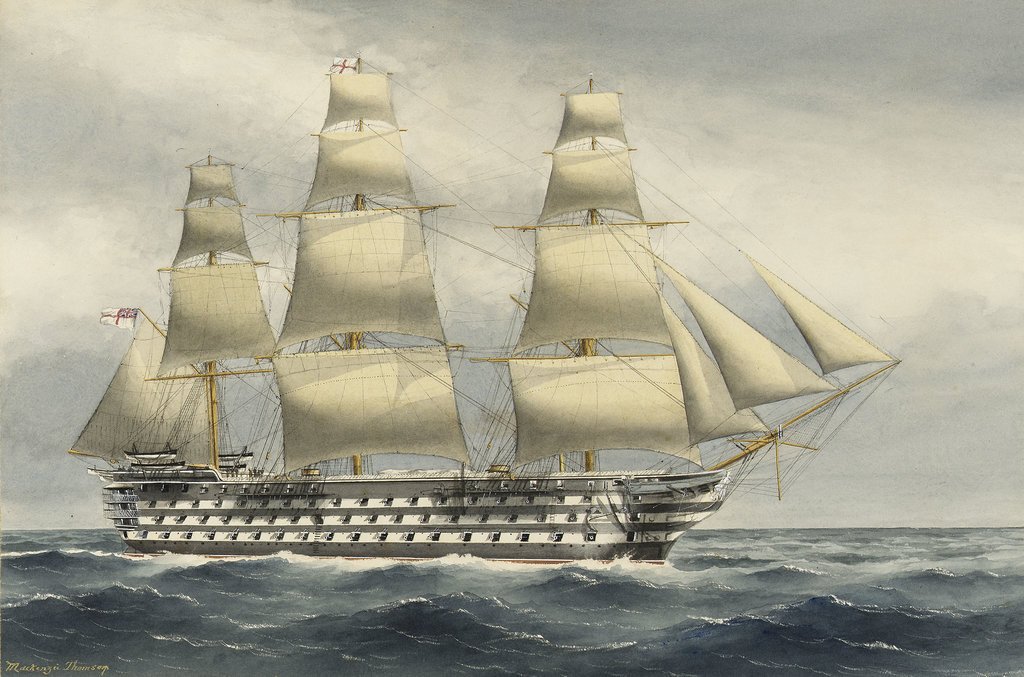

Mixed ships are more common, but the bulk of the workforce is made up of pure sailing ships, tall multi-deckers that tradition required and fast frigates, with impressive crews and a harsh discipline.

1954

A new kind of alliance of British and French forces against Russia in Crimea. The two-decker steamship Napoleon demonstrated the usefulness of its propulsion, urging the British in their turn to convert many sailing ships. Also in this conflict, the very first ironclads of the Tonnante class showed a clear superiority over land fortifications.

SS Britannia, the first modern British ocean-going steamship

1861

Another date to consider as it takes us to the beginning of the secession war, which lasts until 1865 and saw the development of new revolutionary ships. But also in Europe the commissioning of the world first all-iron battleships (Iron Duke) in response to the 1859 French ironclad Gloire. The new warring sea kings.

HMS Conway, used as schoolship in the 1880s.

1866

The Battle of Lissa: A large scale naval battle including Italian and Austro-Hungarian ships. Why this battle is important ? It proved the deadly usefulness of the Ram, which makes it great return since the antiquity…

Battle of Lissa: An improvized ramming fest

1870

The Franco-Prussian War: Ironclads are now top the list of fleets, supported by many mixed vessels. If the war itself is ground-based and short, the panorama offered this year on the fleets of the world is appealing and a turning point where new solutions and experiments are tested, notably, the sail began to loose ground and the steam-only solution gain credits.

1870 duel between French Bouvet and Prussian Meteor.

1890

at the time of the Fashoda crisis, the face of world naval powers has changed: Several newcomers made their appearance in this game of maritime and colonial powers such as France and Britain: Unified Germany, Italy, Austria-Hungary, are in a position to stage an impressive potential, which herald the new equilibrium that will prevail in 1914. Russia will soon reach the height of his power, while Japan emerged from feudalism to enter resolutely into the race with the industrial empires of the world, and USA obsolete “old navy” is on the brink of change. The sail is clearly dying, but torpedo and mine are now serious threats. A new era. The inherited chivalrous spirit gives way to cold reality mechanics.

The Brazilian Navy, battle of Rio de Plata

1894

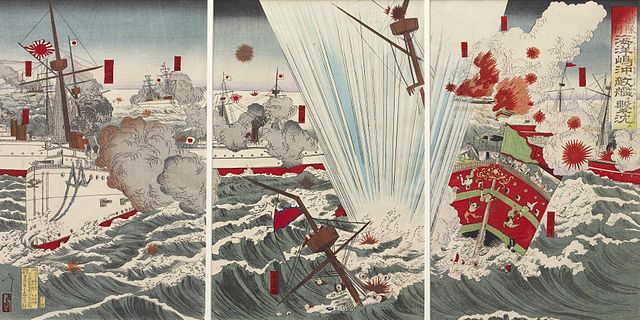

is the first illustration of this new era : Japan attacked China, still partly in the hands of Western outlets, and is mostly a comparison of western technologies and tactics through a duel of Asian fleets, one agonising, another rising. This is the battle of Yalu

1898

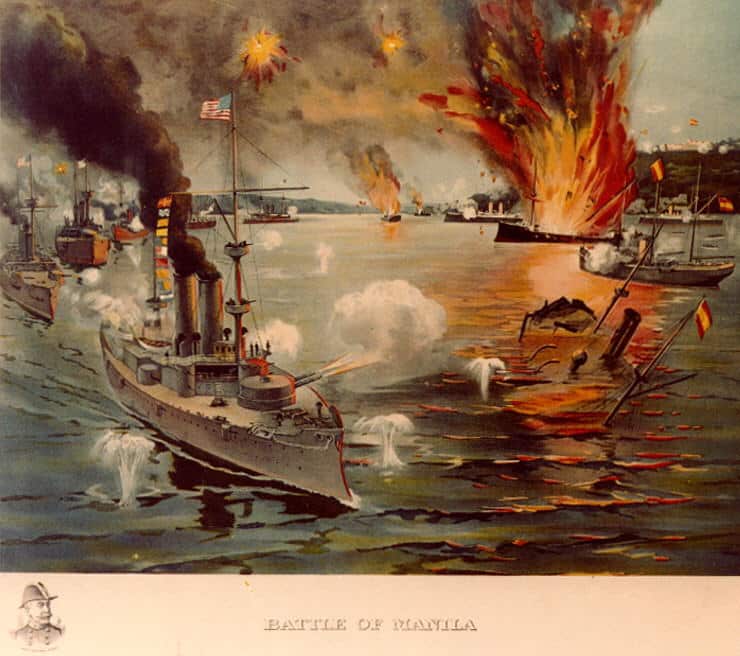

is the “splendid little war”, which saw the old, crumbling Spanish colonial Empire facing a dashing, young American nation that awakened as a sea power.

1905

The final picture, just before the shifting of power and surging of new technologies of 1914. The prologue will be the last Sino-Japanese War of 1905. The following year, leaving the HMS Dreadnought and the battlecruiser which are still evolving maritime concepts. For more information, see “battles”

Battles

The great conflagrations of the past (Trafalgar, Aboukir) are taught as the most famous “classic” battles for ships of the line, to the same level as Salamis and Lepanto for galleys. However on the second half of the century, a new form of confrontation emerged out of traditional patterns of naval tactics because of industrial era’s many innovations.

We do agree that the last great naval battle of ships sailing took place at Navarin in 1827. It was a coalition of Russian ships, English and French associates against the fleet of the Ottoman Empire, still formidable at that time, old adversary of the Western powers and Russia since precisely Lepanto in 1571. Specifically, some naval battles of the period will not be included, the simple fact that the industrial era is a period that begins roughly in 1820. War of the Duchies between Denmark and Prussia in 1864 and a few others.

Bolivarian wars of independence:

-Battle of Sorondo on the Orinoco in Venezuela in 1812: Spanish victory over the insurgents.

-Battle of Lake Maracaibo (1823): Revenge of Venezuela over Spain.

-Battle of Port-Del Buceo (1814): In the Rio de la Plata, the Argentinians destroy a Spanish squadron.

Columbia and American War 1813-1815:

-Battle of Lake Erie (1813): American Victory.

-Battle Lake Champain (1814): Same scenario.

War in the Balkans, Greek Independence:

-Battle of Chios (1822): Greek victory against the Turks.

-Battle of the Bay of Suda (1825): Greek victory against a Turkish-Egyptian coalition.

-Battle of Navarino (1827): Victory coalition of British, French and Russians on Turkish-Egyptian fleet.

Cisplatin War (River Plata):

-Battle of Los Pozos (off Buenos Aires, 1826): Argentina win against Brazil.

-Battle-Lara-Quilmes (1826): Same scenario.

-Battle of Juncal (off Uruguay, 1827): Same.

-Battle of Vila del Carmen (coast of Patagonia, 1827): Same.

-Battle of Monte Santiago (1827): Brazil’s Revenge.

War of Great Colombia

-Battle of Malpelo (1828): Victory against the Peruvian Gran Colombia

-Battle of Cruces (1828): Same scenario.

Russo-Turkish War of 1828:

-Battle of Braila: Russian Victory.

Portuguese Civil War:

-Battle of Vila da Praia (Azores, 1829): Victory of the Liberals on the absolutists.

-Battle of Cape St Vincent (Gibraltar, 1833): Same scenario.

Peruvian-Chilean War:

-Battle of Islay (Pacific, 1838): Combat undecided.

-Battle of Casma (Pacific, 1839): Chilean victory.

Insurrection in Yucatan

-Battle of Campeche (1843): Victory insurgents Yucatan and the Mexican Texans.

Franco-Vietnamese conflict :

-Battle of Tourane (1847): French victory over the fleet Thai imposing French colonial rule for a hundred years.

Crimean War (1853-1855):

-Battle of Pitsunda (1853, black sea coast of Georgia): Russian victory over the Turks.

-Battle of Sinope (1853, Black Sea): Same scenario.

American Civil War (1861-1865)

-Battle of Hampton Roads (1862, coast of Virginia): Combat undecided between Virginia and Monitor.

-Battle of Memphis (1862, Shelby County, Battle River): Union victory.

-Battle of Cherbourg (1864): Fighting between CSS Alabama and USS Kearsarge and win it.

-Battle of Mobile Bay (1864, coasts of Alabama): Union victory.

War of Duchies:

-Battle of Eckenford (1864): Prussian victory over the Danes

-Battle of Rügen (1864, Baltic): Danish victory over the Prussians.

-Battle of Heligoland (1864, North Sea): Danish victory over a Prussian-Austrian coalition.

War of the Triple Alliance:

-Battle of Riachuelo (Rio Prana, Paraguay, 1865): Brazilian victory over Paraguay.

War of the South Pacific:

-Battle of Papudo (Valparaiso, 1865): Chilean victory over Spain.

-Battle of Abtao (islands Chiloe, 1866): Peruvian-Chilean victory over Spain.

-Battle of Callao (peruvian Coast, 1866): Victory in Peru to Spain.

Austro-Italian War:

-Battle of Lissa (Adriatic, 1866): Austro-Hungarian victory over Italy.

Japanese civil war known as the Boshin war :

-Battle of Hakodate (1869): Victory of the Imperial fleet in the fleet of the Republic of Ezo.

Franco-Prussian War of 1870 :

-Combat in Havana (1870): Combat undecided between the gunboats and Bouvet Meteor.

War in the South Pacific :

-Battle of Chipana (1879): Combat undecided between Peruvian and Chilean corvettes.

-Battle of Iquique (1879): Win two ships including a battleship Peruvians against two Chilean ships. The same day, one of the Peruvian vessel was then routed by a Chilean unit in Punta cranes.

-Battle of Angamos (1879): Chilean contrast with a whole squadron deployed against the battleship Huascar.

Franco-Chinese War of 1883 :

-Battle of Foochow (1884): French squadron victory of the Chinese fleet.

Battle-Shei-Poo (1885): French torpedo boats against two Chinese frigates which destroyed one another.

Sino-Japanese War of 1894 :

-Battle of Fengdao (1894): Japan’s victory over Chinese units.

-Battle of Weihaiwei (1894): Japanese victory over a Chinese fleet.

–Battle of Yalu (1895): Same scenario.

Spanish-American War of 1898:

-Battle of Manila Bay (Cavite): American victory over a Spanish fleet at anchor.

-Battle of Cardenas (Cuba): Battle between three and five American Spanish gunboats. Spanish victory.

-Battle of Santiago de Cuba: American victory over the Spanish squadron in Cuba.

Evolution of battles following the evolution of the technique :

The steam enters in the fleet, first in a minority, then more openly in 1850 with the first steam ship of the line, designed by the French Dupuy de Lome. The “Napoleon” is its name, is a three-decker, the British look with irony and disdain. The size of boilers and coal bunkers, dirt, black smoke, everything is good to distrust them. In addition the mode of propulsion is then known impeller, fragile on a warship as directly bordered by the enemy. But nobody thinks so adapted to this new rare vapors of Commerce, the “worm” taken from the great Archimedes. It is well protected under the waterline. The Napoleon, who manages to have a steam propulsion without too much interference and maneuvering space on board, seems to be a good compromise.

Battle of Sinope

The first practical application of this new type of vessel will take place during the Crimean War. The French ships, some mixed, and the English ships, all sailing, shelling the forts of the coast of Crimea. During these operations, the Russians are able to fly and the lack of wind prevented the ships to move freely. worse, the current approaches a disabled ship under fire Russians. The ship seems lost when the “Napoleon” occurs, throwing ropes, the unfortunate vessel and trailer out of range of enemy guns. The maneuver impressed the British who will remember. Other innovations are entering Paixhans like grenades, and the French have armored batteries before the letter, the four thunder. These are used successfully against the Kinburn fort. Batteries are armored with the idea is not new but will test this concept for future high seas battleships

Bombardment of Kinburn by French armoured batteries

Among the operations of the Civil War, we note the Battle of Hampton Roads, on the east coast in 1862, which opposes the first two monitors, the Confederate Merrimack battery sets, and the USS Monitor and its revolutionary single piece of artillery turret. John Coles, the creator of the turret and the lookout, and John Ericsson, contribute. The numerical inferiority of Southern Naval condemn a priori any major action, and they will attempt during the war to break the blockade and to trade war with privateers, including the famous Alabama and Shenandoah. There were few real “battles” more usually duels or coastal bombardments, such as the destruction of the USS Housatonic by the HL Hunley submarine. The Mississippi and its tributaries saw bombardment of forts like on the James River. Numerous monitors were built, converted from older ships.

Battle of Hampton Roads: Duel between ironclads.

Then comes the battle of Lissa, in the Austro-Italian war of 1866. His main lesson was dramatically confirmed the relevance of the spur in naval combat. This feature had vanished from the architecture of warships since very ancient times, since the Romans, already longer believed in the virtues of the collision at the time of war against Carthage. With the arrival of the First Prev vapors and autonomy motive of these vessels, similar to the galleys, propelled by oars, we thought its reintroduction, but it was only with the first cuiassés that it was decided to resume with this accessory: It was indeed a very strong hull and propulsion reliable and powerful to be effective.

The sloop (“aviso”) Bouvet model of 1870.

During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, the number of the French navy exceeded by far those of the Prussian fleet. In fact apart from an aborted project of landing in Denmark, which would probably have resulted in a large-scale direct confrontation between the two navies, the only naval encounter took place November 9, 1870 at Havana between the Bouvet and the gunboat Meteor. It ended in a “tie” the two ships leaving out of action.

Industrial age fleets

At the forefront is the United Kingdom, second only to France, and in third place the Spanish fleet in a way that has barely changed since the end of Napoleonic wars… Russia was at that time, a match for the Turkish fleet, but certainly not against a combined Franco-British squadron.

1854: Review at the start of the Crimean War:

Mixed steamship of the line HMS Victoria 1859

1861: The Secession War.

That conflict raged during four years and seen naval combats as well as riverine battles, and many military improvements and new concepts put to the test. The disproportion of naval forces in favor of the Union is obvious. Nonetheless, the two fleets dealing with different priorities are interesting by the units they built and operated during the conflict:

1865: The Austro-Italian war

The Battle of Lissa highlights the usefulness of the spur resulting from the vessels propulsion, and as subsequent renewal of antiquity tactics and general flavor. This section focuses on the potential of the fleets of its two belligerents at the beginning of the conflict. An aging, multicultural empire, and a dashing new nation, who recently gets its independence and will innovate in naval architecture and design under the new name of Regia Marina. On the Austro-Hungarian side this victory fuelled the will to built a large navy, although sized to the Adriatic sea, which was done in the 1880-1890s. Note: The battle of Lissa comprises a complete review of both navies.

1870: The Ironclad era & the Franco-Prussian war

An era defined by the launching of the French Gloire and the British Warrior which led the way for all other European nations, and the Franco-Prussian War surged as the key moment for both the French and German histories. On the latter side, this was the unification of German states inherited from the Holy Roman Empire into a single unified Empire under the iron will of Prussian politician Otto Von Bismarck, and on the French side, the definitive end of the Empire and the Republic firmly implanted for the next 200 years (as well as the commune, the first proletarian revolution).

The naval forces in this played a little part, but the state of the navies of the time is a good screenshot of what will come. Fleets are ranked in order of importance. The only “naval battle” which occurred was the duel between the gunboats Komet and Courbet off the South American coast, which ended as a draw.

Prussian Navy 1870

Grand review of world’s 1870 Fleets :

Dutch Screw Frigates & corvettes

Prins H. der Neth. Turret ship (1866)

Buffel class turret rams (1868)

Skorpioen class turret rams (1868)

Heiligerlee class Monitors (1868)

Bloedhond class Monitors (1869)

Gloire class Bd. Ironclads (1859)

Magenta class Bd. Ironclads (1861)

Palestro class Flt. Batteries (1862)

Arrogante class Flt. Batteries (1864)

Provence class Bd. Ironclads (1864)

Embuscade class Flt. Batteries (1865)

Belliqueuse Bd. Ironclad (1865)

Alma Cent. Bat. Ironclads (1867)

Ocean class CT Battery ship (1868)

French converted sailing frigates (1860)

Infernet class Cruisers (1869)

Bourayne class Cruisers (1869)

Arbalete class gunboats (1866)

Etendard class gunboats (1868)

Revolver class gunboats (1869)

- Monitor Atahualpa (1865)

- CT. Bat Independencia (1865)

- Turret ship Huascar (1865)

- Frigate Apurimac (1855)

- Corvette America (1865)

- Corvette Union (1865)

- Formidabile class (1861)

- Pr. de Carignano class (1863)

- Re d’Italia class (1864)

- Regina maria Pia class (1863)

- Roma class (1865)

- Affondatore turret ram (1865)

- Palestro class (1865)

- Guerriera class (1866)

- Cappelini class (1868)

- Sesia DV (1862)

- Esploratore class DV (1863)

- Vedetta DV (1866)

1890: The Fashoda incident :

Three fleets are then nominated for the colonial control of Africa. Steam definitely replaced sail, turrets have supplanted batteries, destroyers, submarines and mines appeared. Dramatic sea warfare changes are on the way, a new diplomatic order is building on the world chessboard. Reviews of France and UK in 1890 (See the 1898 page)

1894: The Sino-Japanese War :

First – (the second comes in 1937), sees clash of ships still rely on technology and Western expertise. The success of Japan at the battle of Yalu, far from certain at the start, earned the empire a model of commitment to Britain, while cultivating its difference and overall confident about its superiority in Asia.

Japanese imperial navy 1894 and Chinese imperial navy: See the 1898 Page.

1898: The Spanish-American War

In “splendid little war”, largely due to Teddy Roosevelt expansionism will, the American casus belli came as an excuse to help the insurgents to free Cubans from the old Hispanic rule, starting from the accidental explosion of the USS Maine, well exploited by press. This gave the battle of Santiago de Cuba, and later the battle of Manila bay, in the Spanish-held Philippines. In two battles, the still young and freshly reconstituted US navy decisively defeated a Spanish fleet almost without loss, despite superior forces, although made up of obsolete ships and victims of the defensive choices of their commander, helped by US deception and surprise alike.

La Plata class Coast Battleships (1875)

Pilcomayo class Gunboats (1875)

- Tordenskjold (1880)

- Iver Hvitfeldt (1886)

- Skjold (1896)

- Cruiser Fyen (1882)

- Cruiser Valkyrien (1888)

- Gunboat St Michael (1970)

- Gunboat “1804” (1875)

- Gunboat Dessalines (1883)

- Gunboat Toussaint Louverture (1886)

K der Neth., rig. turret ship (1874)

Evertsen class coast defence ships (1894)

Pontania class Gunboats (1873)

Friedland CT Battery ship (1873)

Richelieu CT Battery ship (1873)

Colbert class CT Battery ships (1875)

Redoutable CT Battery ship (1876)

Courbet class CT Battery ships (1879)

Amiral Duperre barbette ship (1879)

Terrible class barbette ships (1883)

Amiral Baudin class barbette ships (1883)

Marceau class barbette ships (1888)

Cerbere class arm. rams (1870)

Tonnerre class Br. Monitors (1875)

Tempete class Br. Monitors (1876)

Fusee class Arm. Gunboats (1885)

Acheron class Arm. Gunboats (1885)

Jemmapes class C.Defense ships (1890)

La Galissonière Cent. Bat. Ironclads (1872)

Bayard class barbette ships (1879)

Vauban class barbette ships (1882)

Prot. Cruiser Amiral Cécille (1888)

Descartes class Cruisers (1893)

R. de Genouilly class Cruisers (1876)

Laperouse class Cruisers (1877)

Crocodile class gunboats (1874)

Tromblon class gunboats (1875)

Condor class Torpedo Cruisers (1885)

G. Charmes class gunboats (1886)

Inconstant class sloops (1887)

Bombe class Torpedo Cruisers (1887)

Wattignies class Torpedo Cruisers (1891)

Levrier class Torpedo Cruisers (1891)

Siete de Setembro class (1874)

- Pr. Amadeo class (1871)

- Italia class (1885)

- Ruggero di Lauria class (1884)

- Carracciolo (1869)

- Vettor Pisani (1869)

- Cristoforo Colombo (1875)

- Flavio Goia (1881)

- Amerigo Vespucci (1882)

- C. Colombo (ii) (1892)

- Pietro Micca (1876)

- Tripoli (1886)

- Goito class (1887)

- Folgore class (1887)

- Partenope class (1889)

- Giovanni Bausan (1883)

- Dogali (1885)

- Staffeta (1876)

- Rapido (1876)

- Barbarigo class (1879)

- Messagero (1885)

- Archimede class (1887)

- Guardiano class GB (1874)

- Scilla class GB (1874)

- Provana class GB (1884)

- Curtatone class GB (1887)

- Castore class GB (1888)

Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen

Søværnet

Søværnet

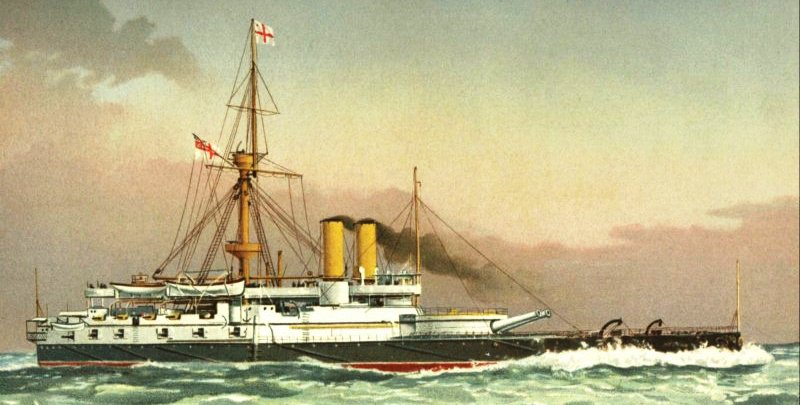

Royal Navy

Royal Navy

HMS Hotspur (1870)

HMS Glatton (1871)

Devastation classs (1871)

Cyclops class (1871)

HMS Rupert (1874)

Neptune class (1874)

HMS Dreadnought (1875)

HMS Inflexible (1876)

Agamemnon class (1879)

Conqueror class (1881)

Colossus class (1882)

Admiral class (1882)

Trafalgar class (1887)

Victoria class (1890)

Royal Sovereign class (1891)

Centurion class (1892)

HMS Renown (1895)

HMS Shannon (1875)

Nelson class (1876)

Iris class (1877)

Leander class (1882)

Imperieuse class (1883)

Mersey class (1885)

Surprise class (1885)

Scout class (1885)

Archer class (1885)

Orlando class (1886)

Medea class (1888)

Barracouta class (1889)

Barham class (1889)

Pearl class (1889)

1905: The Russo-Japanese War

This war was at the same time the first confrontation of modern battleships and the last were they fought in the old style. The battle of Tsushima also was an earth-shaker event, that boosted Japanese ambitions (and explains the Pacific war in 1941-45) and the first nail in the coffin of the Russian Empire (and the revolution and USSR, the cold war). In 1906, dreadnoughts required rethinking the concepts of naval warfare in terms of speed rather than firepower. We take the opportunity to make a general assessment of fleets at that time:

Belligerents :

-Russian imperial Navy 1905

-Japanese imperial navy 1905

Other fleets of 1905 :

-Royal navy

-French republican navy

-Imperial German navy

-United States Navy

-Italian kingdom

-Spanish Armada

-Dutch Royal navy

-Ottoman imperial navy

-Chinese imperial navy

Historical Landmarks

Ships that made History

In this chapter we will focus on ships which had a significant impact on Naval History, chiefly on propulsion innovations, but not only: Navigation, cargo handling, protection, or just ships associated with particular events or campaigns (like oceanography).

Bulk carriers, from John Bowes to Berge Stahl:

A Bulk carrier (“bulk carrier”) in English, is the goods carrier “by default” since probably the Middle Ages. During the antiquity, it already existed but standardized to the transport of ponderous thanks to the amphorae, the world’s first “universal container”. The transportation of all types of goods was the norm before the appearance of container ships. Bulkers in the modern sense of the term appeared around 1860, the pioneer being the John Bowes (1952). Prior to this date, because of the sailing, the crossings were long, and for steam still stammering and mixed transport, the coal took too much room to make profitable the remaining place in the hold.

The transport of heavy goods in large holds did not go without serious stability problems, which explained many shipwrecks. The loading of various goods was a real headache and a very long operation, and dangerous for the dockers as for the sailors. Without solving these loading problems, the John Bowes was for the first time bringing a set of solutions to these problems and generate a real specialization.

Until 1914, this type of cargo steamer alone was predominant, facing a traffic still largely populated by tall iron sailing ships. In 1905 alone, about fifty of these steel sailing ships were launched. Sailing seemed to many shipowners, still profitable in some segments of the shipping industry. Progress will be slow and will be on the shape and the opening and closing devices of the holds, the mechanisms of the hoists and all the maneuvers on board. If the steam managed them, the electric would slowly take its place. The use of hoists of a new kind made it easier to load. In 1914-18, maritime traffic, which for the most part was based on English ships, was the victim of the excessive underwater warfare of the German Empire and its allies. The number of sailed yachts increased sharply, in particular because of their slowness and their impossibility to maneuver effectively. Steam cargoes alone also paid their share. In 1917, the admiralty to the losses decided to launch a plan of massive construction of standardized cargo ships. These standards became those of the post-war period and the majority of these “standard” ships (type A to J) still constituted nearly half of the cargo ships in 1939.

The second world war saw a second battle of the Atlantic, on a much larger scale and more relentless, because of the number of submarines engaged on one side and the variety and massiveness of the answers made by the British Admiralty, then after the entry into the US war, the US admiralty. Cargos type C1, C2, C3, built in mass in the mid-30s, then the famous “Liberty ships” and “Victory ships” During the war, there was a war of numbers, statistics, and ultimately many of these mass-produced bulk carriers that were not innovative at all but were strong, fast, and easy to maintain.In 1950, the first container ship Ideal X, forever revolutionized the transport of goods, but bulk carriers did not disappear, on the contrary, the last ones even reached a tonnage worthy of supertankers like the Berge Stahl…

Standards (recent classifications)

Handysize: 10,000-35,000 tonnes Handymax: 35,000-50,000 tonnes Panamax: 50,000-80,000 tonnes Capesize / over Panamax, 80,000-300,000 tonnes.

Most large bulk carriers have 5 to 9 holds and are equipped with cranes between each hold, this for the poorly equipped ports. Some are called “self-unloaders” and have a system of side loading strips (the “grasshopper”). Others are gearless, with no unloading equipment and depend on well equipped ports. These are the most economical. There are also so-called “OBO” (Ore Bulk carriers), relatively complex transport, BIBO who are responsible for packing the bulk during the crossing, and finally specific types of bulk carriers like those of the American Great Lakes and the “barges”. bulk carriers “fresh water.

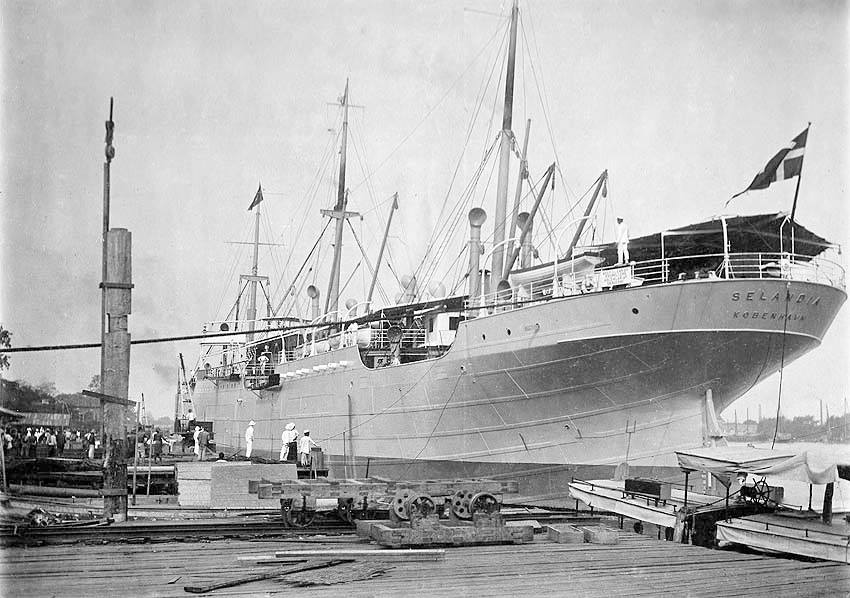

MV Selandia, the first diesel-propelled freighter (1911)

MS Selandia, the first diesel freighter. Civilian vessels are rarely seen on naval encyclopedia, except when they innovated ways of building or propelling ships. The Danish MS Selandia was one of these. Completed in 1911 by Burmeister & Wain, this 6800 TW vessel was fitted with two 8 cylinder diesel, propelling two shafts, rated for twice 1 250 ch and capable of 12 knots. Not only it allowed to get rid of large and sometimes dangerous boilers but also the venerable triple and quadruple expansion steam engines arrived at the end of their development, and the bulky provisions of coal carried, which reduced the amount of payload carried.

Just like the turbine did for torpedo boats and soon larger naval ships, the diesel made its way not only in the civilian market but also in the Navy, for patrol boats and needless to say, for submarines, allowing them to cruise large distances. Submarine warfare would have been impossible without it. This strange funnel-less ship soon earned world fame, being visited by many heads of states, like an enthusiastic Churchill before the war. She also served as a mixed passenger ship until 1942, capsizing off Omaekazi, Japan. Do note that in 1903, two ships became the first propelled with diesel-electric propulsion, the Russian Vandal and French Petit-Pierre.

John Bowes, the first modern cargo ship (1852)

This bulk carrier is the first true one to have been built from the keel up. A true Precursor, she was innovative on many points. Built entirely of steel, her rigidity seemed to ensure a long life. She worked on steam first (although having masts she can be rigged in schooner), which ensured a good regularity of service. With additional ballast loaded with seawater, this made handling operation quick and safe, and stability was greatly improved at sea. It is on this last point that this “steam collar”, a term used for “cargo” (there were no other sub-distinctions), built and chartered by the General Iron Screw Company Company, proved to save time and considerable money and her career was long and very profitable for the owner. Very quickly imitated, she became a standard. The John Bowes completed her career in November 1933 under the Spanish flag, she sank in a storm. At that time the bulk carriers were all of a derivative model.

Src :

http://freepages.family.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~treevecwll/ttrans.htm

http://www.plimsoll.org/diversityofships/shipsofthesteamage/howthetrampsteamerevolved/default.asp

Technical specification :

Dimensions: 30.8 meters PP by 5.28 meters by 3.20 meters of draft.

propulsion: 2 steam engines of 2.35 hp for a single propeller, 9 knots. He received new machines in 1864 and 1883.

Cargo: A load of 650 tons of coal, with a speed of delivery equivalent to two charcoal sailing classic of the time.

Ideal X, the first container ship (1956)

The Ideal X, a T2 tanker owned by Malcom McLean (1956). She was modified to carry 58 metal containers between Newark, New Jersey and Houston, Texas on its first voyage. In 1955, McLean built his trucking company McLean, into one of US’ biggest freighter fleets with a revolutionnary approach to intermodularity, which he also co-invented. Now Intermodal in transport is the norm. To appreciate the scope of the innovation, let’s recall how it was before:

Shipping during the early part of the Century and the Industrial Era did not changed much if not the the apparition of reliable steam engines and therefore, more constant trade with previsible schedules. Freighters during both world wars operated types of dry cargo: Bulk cargo and break bulk cargo (like grain or coal) unpackaged in hull’s compartments a bit like on tankers, later using ballasts to avoid problems of stability in heavy weather.

Break-bulk cargo was basically packages or various packed goods, carried in nets and loaded during long man hours in a pecise scheme. These were loaded, lashed, unlashed and unloaded from the ship one piece at a time by dockers. This process took time and could lead to accident, sometimes fatal ones. Mishandling cargo or bad storage has also consequences. Also freighters only carried these goods inside the ship in large bays closed by bilge boards.

Mc Lean had the idea of grouping cargo into standard containers. He devised metallic boxes capable of housing 1,000 to 3,000 cubic feet (28 to 85 m3) of cargo instead of nets. The larger boxes could house up to 64,000 pounds (29,000 kg) and their shape made it more secure and faster to load cargo inside a large hold. One of these benefits was that allowed the cargo to stay firmly in place when secired due to the box shape and standard in case of heavy weather (excessive roll) and also made handling operations much faster.

It reducing shipping time by 84% and costs by 35%. Nowadays this way of carrying goods represents 90% of the world trade. An estimated 125 million TEU or 1.19 billion metric tons worth of cargo ten years ago. These containers, which generally are loaded top to bottom of plastified loads of corrugated boxes are usually of two types of the same size, defined by the internationally accepted ISO norm: The 20 feets (6.06m) and 40ft (12.2m). Both are 8ft (2.43m) wide, 8.5ft (2.59m) high with locked doors using the same system, although with time refrigerated types or higher boxes made their apparition like the 9.5ft (2.89m) model.

The beauty of the concept is that they also fit railways platforms or the standard European 30 ton truck fit to carry the 40ft/”13,6m”(& 45ft) payload hold. These boxes are nowadays so ubiquitous and their human-compatible dimensions made them ad hoc habitats, and many end their life on land, either as private storage boxes (a car can fit inside), server housing, or student flats. But there are many projects to recycle and refurbish them as studios and flats. This could even be the return of the 1970′ concept of ‘modular housing’ that was tried in Tokyo and other places.

MS Savannah, the first nuclear-propelled cargo (1962)

The NS Savannah, first nuclear-propelled cargo ship. She was planned by Government agencies after Eisenhower’s “Atoms for Peace” initiative, approved by the Congress in 1955 and developed by a special joint venture between the Atomic Energy Commission, the Maritime Administration (MARAD), and the Department of Commerce, built in the state of New Jersey. Her overall cost was $46,900,000 ($18,600,000 for the ship alone and $28,300,000 for the nuclear plant and fuel) – whereas the average liberty ship cost was $2,000,000, but the goal was to demonstrate the ability to travel dozens of times without refueling, which could be seen as an advantage but first and foremost the ship was an ambassador of peaceful applications of the atomic energy. At first, there were talks about just taking the USS Nautilus powerplant, but a conscious choice was made to create a reactor to commercial specification breaking all tie with the military.

NS Savannah was launched in 1959 at Yard 529, completed in December 1961, acquired for commercial service in May 1, 1962 and she made her maiden voyage on August 20, 1962. She displaced 13.999 GRT or 9.900 long tons DWT, for 596 feets long (181.66 m) and 78 ft wide (23.77 m). The Babcock & Wilcox (a well-known boiler manufacturer) nuclear powerplant rated for 74 Megawatt powered two De Laval steam turbines and the whole powerplant was rated for 20.300 hp, connected to a single propeller shaft. Top speed achieved on trials was 24 knots, reduced to 21 in service (39 kph or 28 mph). Her range was 300,000 nmi or 560,000 km with her 32 fuel elements. She was conceived as a mixed passenger/cargo ship, which was obvious on her profile, as she can carry in nice accommodations 60 passengers and 10,040 tons of cargo fo a crew of 124 (yes, this was way before automatization, and there was service personnel for the passengers).

But her service was short. She started with a passenger-first cruise ships for the States Marine Line with reduced cargo and was later converted as a cargo ship alone for the American Export-Isbrandtsen Lines from 1965. She resumed service until the end of 1971, when she was deactivated. Three other nuclear-propelled civilian ships were built (German NS Oto Hanh, Japanese Mutsu, Soviet Sevmorput but the real first nuclear-propelled civilian ship was the Soviet icebreaker Lenin back in 1957.

The NS Savannah (also the name of the first steam-propelled American passenger ship) is now at anchor at Patriots Point Naval and Maritime Museum near Mount Pleasant, South Carolina as a museum ship and classed as a National Historic Landmark. More recently, she has been moved to Maryland to undergo a full nuclear decommissioning process, in order to be turned over to a museum group for preservation and display.

Nuclear propulsion was never feasible commercially, as the building cost far exceeded the fuel/cargo cost per ton. Besides, containers rapidly made operating costs even lower, but this story is for another day…

Read more:

http://www.radiationworks.com/nuclearships.htm

Berge Stahl, the world’s largest cargo ship (1986):

This bulk carrier is a monster. With its appearance of supertanker, it seems promised to transport heavy, and it was actually built in South Korea (Hyundai) for the purpose of transporting iron ore. Launched in 1986 on behalf of the Norwegian shipowner Bergesen Worldwide Gas ASA, it could only touch two ports: Europoort, Rotterdam in Holland and the Terminal Marítimo de Ponta da Madeira of Itaqui, Brazil.

It currently holds the record for a mineral carrier, and that for a bulk carrier. The only bigger “cargo ship” is currently the Emma Maersk container ship. Yet, like his ancestor of 1850, this giant has its full length for the payload, its castle and the crew, the propulsion being at the extreme rear, and being provided by a single propeller of 9 meters in diameter. Like the John Bowes, its empty return crossings are made on ballasts filled with seawater. The desalinization of the latter as the cleaning of the holds is part of its everyday life at anchor.

Technical specifications:

Dimensions: 342.1 meters by 63.5 m by 23 m of draft.

propulsion: 1 Hyundai diesel of 27610 hp for a single propeller, 13.5 knots.

Cargo: A load of 364,768 tons of iron ore.

Sources: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Berge_Stahl

The grandfather of steam power.

The grandfather of steam power.

Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola 中华帝国海军

中华帝国海军 Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Πολεμικό Ναυτικό

Πολεμικό Ναυτικό Koninklije Marine

Koninklije Marine Marine Nationale

Marine Nationale Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 大日本帝國海軍

大日本帝國海軍 Preußische Marine

Preußische Marine Российский флот

Российский флот US Navy (‘old navy’)

US Navy (‘old navy’) Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliches Marine

Kaiserliches Marine Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign