Nuclear Powered Attack Submarines: USS Skipjack, Scamp, Scorpion, Sculpin, Shark, Snook (SSN-585 to 592) 1956-1990

Nuclear Powered Attack Submarines: USS Skipjack, Scamp, Scorpion, Sculpin, Shark, Snook (SSN-585 to 592) 1956-1990Cold War US Subs

GUPPY | Barracuda class | Tang class | USS Darter | T1 class | X1 class | USS Albacore | Barbel classUSS Nautilus | USS Seawolf | Migraine class | Sailfish class | Triton class | Skate class | USS Tullibee | Skipjack class | Permit class | Sturgeon class | Los Angeles class | Seawolf class | Virginia class

Fleet Snorkel SSGs | Grayback class | USS Halibut | Georges Washington class | Ethan Allen class | Lafayette class | James Madison class | Benjamin Franklin class | Ohio class | Colombia class

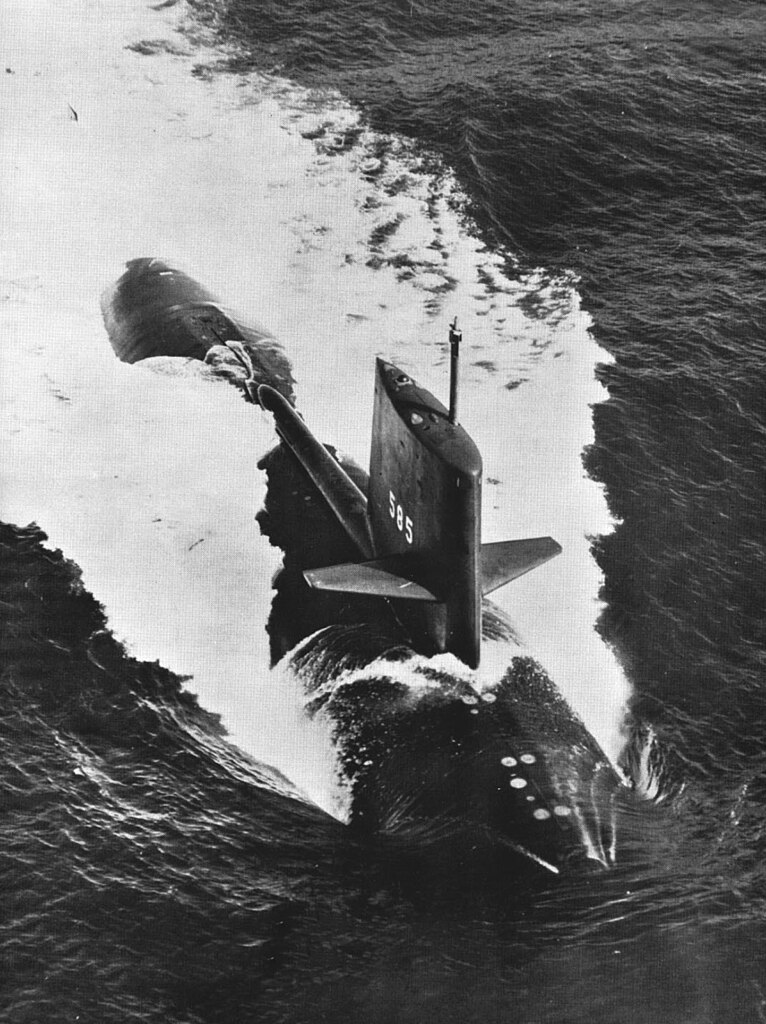

The Skipjack class (project SCB 154) were six Navy nuclear submarines entering service in 1959-60: Skipjack, Scamp, Scorpion, Sculpin, Shark, Snook, introducing the teardrop hull and new S5W reactor and really quickstarting the second generation of USN nuclear submarines. They became the fastest U.S. nuclear submarines until the Los Angeles-class from 1974. They also obliged the USSR to revise its ASW policy. All had a long operational lives, were never modernized but amassed a long list of excellence awards and battle stars for their tours of duty in Vietnam. #usn #USNavy #unitedstatesnavy #skipjack #nuclearattacksubmarine

Development, Project SCB 154

The teardtop hull introduced by USS Albacore had a deep influence on submarine design in the USA but also abroad. Two class at home were derived from its unique shape, the last conventional US attack submarines, the Barbel class, and the first true class of SSNs after the Skate (built in meaningful numbers), the Skipjacks. Ther Barbel class were a sort of backup, being cheaper than SSNs, whereas the Skipjacks became the perfet underwater hunter-killers, combining a new high performance reactor and this new shape to reach speeds in excess of 33 knots as it was hoped. One of the key concerns were advanced in nuclear reactors made in the Soviet Union, and the Project 627 (november) attack subs that were designed at the same time. The first boat was launched in 1957 a year prior. They later were proved capable to reach 30 knots submerged based on two reactors.

So the USN needed an “interceptor” for this first generation of Soviet SSNs in any case. Combining the recently pioneered teardrop hull and the new, next-gen pressurized nuclear reactor promoted by Westinghouse, paired with its own in-house steam turbines, were communicated as the best option to Hyman Rickover. They seemed a match in heaven to go past the 22 knots of USS nautilus, Skate class or 23 knots of Seawolf. Ten knots faster was indeed the core metric sustained under SBC 154 and a daunting prospect to achieve. Only nuclear power could do this. The true advantages of the teardrop hull were of course capable of bringing up the supplement needed to reach this tershold, but the specifics of the new reactor were of course of an immense importance and great care was taken in its development (see later). It was found however the Westinghous turbines were disappointing (and costly) and for the rest of the class, General Eletric equivalents were chosen.

SBC 154 development started probably in 1954, unrelated to the number, the design was solidified in 1955 and the class approved FY1956, so as fast as possible. The lead boat was SSN-585. It was the next iteration which followed previous conventional boats number, the supplementary “N” defining the propulsion source.

This first boat was untrusted and ordered to Electric Boat, laid down on 29 May that year. She was commissioned three years later in April. Construction time ws a bit shoter for her five sisters, the last one, USS Snook, being commissioned in October 1961. Numbers were still limited as the class was seen still a bit as experimental, albeit six boats were for a full squadron already, so they were also intended to be fully operational as a unit.

Design of the class

The hull was inspired by the Albacore, but the internal arrangement were innovative as well and similar to the Barbel class built concurrently and a bit earlier. Compared to previous 1st gen US SSNs she had a single screw and a X shaped rudder and stern plane combo. The single screw adoption trigerred, like for the Albacore and Barbels, considerable debate and analysis within the Navy and eventually this so-called “body-of-revolution hull” reduced surface sea-keeping, but compared to the immense gains in underwater performance, this was seen as a necessary tradeoff.

Hull and general design

The Skipjacks used the same HY-80 high-strength steel as Albacore. It had a yield strength of 80,000 psi (550 MPa), but it was not intended first to increase diving depth but just for extra rigidity at greater speeds. HY-80 nevertheless remained standard in submarine construction through the Los Angeles class, which presented its own set of innovation, just 13 years later.

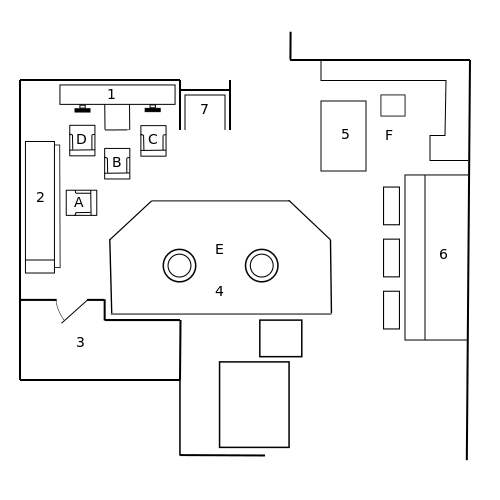

Control room of Skipjack class, the bow is at the top.

The Skipjack retook from the Barbels an innovative, unique combination of a conning tower, control room, and attack center, all in the same single room. A trend that was now standardized for duture submarines. This went with the new “push-button” ballast control feature instead of a maze of valves, which were still present in some cases as a backup. The trim system piping no longer went through the control room but instead was remotelly electrically activated, using hydraulic operators on each valve, all from the control room. This considerably reduced control room space, reduced crew via automation and gained time for conducting trim operations. The overall layout allowed also to display all navigation essentials, combined sensors data and weapons operations make for the captain and XO overall management of the boat far more leaner and easier. This decision helping process at greater speed matched the new underwater speed of these boats.

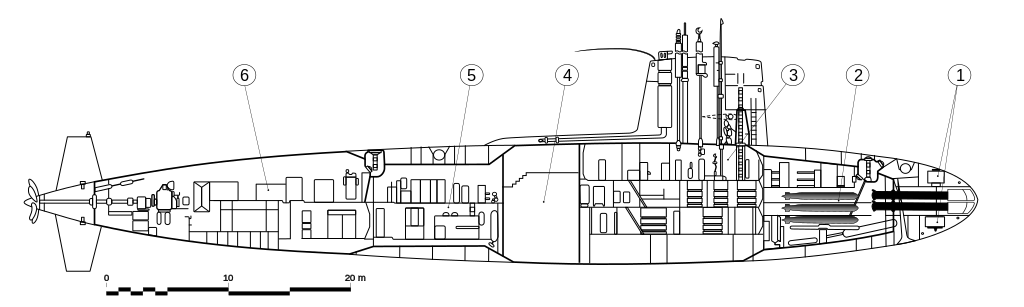

Cutaway drawing of Skipjack class:

1. Sonar arrays

2. Torpedo room

3. Operations compartment

4. Reactor compartment

5. Auxiliary machinery space

6. Engine room

Much of the overall internal arrangement was found so successful as to be retaken for the next Thresher and Sturgeon-class submarines. Albeit the centralized control room and push button trim system reduced the crew a bit, automation was not systematic and these boats still had a crew of 99 for a relatively small hull, unlike the roomier Nautilus or Seawolf. So if sailor had three-tiered bunks, they were not enough for the whole crew, as they were shared and used in three shifts. Only officers had their own provate bunks, and a captain a proper bed in his cabin. Interiors, thanks to the interned piping was covered with paneling making the internals cleaner overall.

Great care was placed in climatization and air purification as well and multiple small innovation alleviated the still difficult living conditions aboard. They felt “cramped” and this was only gradually improved on the next Tresher/Permit and finally large Los Angeles class. At 6,927 tonnes (6,818 long tons) submerged and 362 ft (110 m) long instead of 251 ft 8 in (76.71 m) and a more constant beam hull, they felt far more roomier even for their crew of 16 officers +127 enslisted.

The Skipjacks had five main compartments in a relatively short, stubby hull, especially compared to the latter boats, elongated and with much smaller fins. These compartments were the Torpedo Room, Operations Compartment, Reactor Compartment, Auxiliary Machinery Space (AMS), and Engine Room.

The design was still single-hull with a double hull around the torpedo room and AMS for ballast tanks. The next Tresher class improved on these and extra innovations were brought later by the USS Tullibee when the torpedo room was relocated into the operations compartment via angled midships torpedo tubes. This freed the whole bow to house a far larger sonar for increase sensory performances.

The bow planes were moved to the sail in order, as calculated, to cut down on flow-induced noise close to the bow sonar arrays. They became the “sail planes” or “fairwater planes” and the Skipjacks were the first to sport these, placed at the top of a massive sail compared to their hull size. They were also found successful enough to be later backfitted on the Barbels. This became standard on U.S. nuclear submarines until, again, return to bow planes on the last batch of Los Angeles-class submarines (launched 1988). The Skipjacks also featured a small “turtleback” behind the sail, to contain the exhaust piping of the auxiliary diesel generator, and albeit it could create turbulence, placing in the wake of the fin seemed the only way to reduce this. That feature would remain for subsequent class, but reduced.

Powerplant

The Skipjacks class were the first US Navy subamrines to introduce the S5W reactor. Known as ASFR (Advanced Submarine Fleet Reactor) during ist development, the S5W reactor designation stands for S = Submarine platform; 5 = Fifth generation core designed by the contractor and W = Westinghouse was the contracted designer.

The Skipjacks class were the first US Navy subamrines to introduce the S5W reactor. Known as ASFR (Advanced Submarine Fleet Reactor) during ist development, the S5W reactor designation stands for S = Submarine platform; 5 = Fifth generation core designed by the contractor and W = Westinghouse was the contracted designer.

Ity became the standard reactor for submarines of the United States Navy until the Los Angeles-class (again) coming up with the S6G reactor. It was considered so advantageous as being requested to equip the the first British SSN, HMS Dreadnought.

Some time before 1971, the S5W vessel and core replaced the S1W reactor vessel and core at the S1W prototype facility, which kept its name. The additional power generated by the S5W reactor at higher power levels urged the construction at the facility of steam dumps outside the original submarine style hull.

This pressurized water reactor was both simplied and overdesigned, but this was mainly intended at enhancing redundancy and intended to ease combat operations and tolerance of battle damage. These contributed greatly to its reliability, longevity, and safety record, in complete opposite of the Soviet 1st gen reactors.

The S5W reactor plants were later upgraded (not on the Skipjacks though) to be refueled with a S3G core-3.

The S5W was used on 98 U.S. nuclear submarines in 8 classes, making it the most-used US Navy reactor design ever.

In the end, the S5W procured a considerable advantage, powering via steam exchangers and boilers two General Electric geared steam turbines rated for 15,000 shp (11,000 kW)) on a single shaft. There was also a five-bladed propeller which shape resulted from studied made on USS Albacore, this also became a standard for next classes.

The next cross design for the rudder/diving plans alleviated the supposed agility problem. Top Speed when surfaced was 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph) and underwater it was an unprecedented 33 knots (61 km/h; 38 mph) submerged. Range was of course unlimited except by the quantity of food aboard. It was tested that the crew could endure about 90 days at sea or more in wartime, reduced a but in peacetime. Test depth thanks to the new hull and steel used reached some 700 ft (210 m). To compare, USS Nautilus was probably around 500 ft.

The class had internal divergence between yards: SSN585 had two sets of Westinghouse geared steam turbines, and a single Westinghouse S5W nuclear reactor whereas the rest of the class, SSN588 to 592 had two sets of General Electric geared steam turbines instead, judged more efficient, but kept the same Westinghouse S5W unit.

Armament

This was the only compartment in which the new SSN was not innovative. They were among the last SSNs with bow torpedo tubes, no stern tubes, a feature considered obsolete with the advent of better acoustic torpedoes and better speed. They had, like the Barbels, six bow tubes, in two rows of three. All were loaded and operated parlty remotelly from the central control room and parlty from the torpedo room, notably for maintenance and weapon selection. Indeed, and unlike the Barbels or any previous US attack submarine, they were given an imprecedented choice of weapons, bar from encapsulated antiship missiles. They just lacked the sensors to operate these.

This was the only compartment in which the new SSN was not innovative. They were among the last SSNs with bow torpedo tubes, no stern tubes, a feature considered obsolete with the advent of better acoustic torpedoes and better speed. They had, like the Barbels, six bow tubes, in two rows of three. All were loaded and operated parlty remotelly from the central control room and parlty from the torpedo room, notably for maintenance and weapon selection. Indeed, and unlike the Barbels or any previous US attack submarine, they were given an imprecedented choice of weapons, bar from encapsulated antiship missiles. They just lacked the sensors to operate these.

These were all similar Mrk 59 tubes, using a new filling method to avoid noise and twenty four 21 inch (533 mm) were carried in total, including the six pre-loaded at port to gain space.

Below are listed all these torpedo types:

Mark 37 torpedoes

A post-WW II electric acoustic torpedo forst deployed in 1957. The Skipjacks were probably given the 1960 Mark 37 Mod 1, specs below. The 19″ (48.3 cm) Mark 37 and Mark NT37 Designed about 1956 (last introduced, Mod 3: 1967) became the standard US Submarine launched ASW torpedo of the 1960s and until the 1990s.

⚙ specifications Mark 37 TORPEDO |

|

| Weight | 1,660 pounds (750 kg) (mod.1) |

| Dimensions | 161 inches (410 cm) (mod.1) x 19 inches (48 cm) |

| Propulsion | Mark 46 silver-zinc battery, two-speed electric motor |

| Range/speed setting | 23,000 yards (21 km) at 17 knots, 10,000 yards (9.1 km) at 26 knots |

| Warhead | 330 pounds (150 kg) HBX-3 high explosive with contact exploder |

| Max depth | 1,000 feet (300 m) |

| Guidance | Active/passive sonar homing, passive 700 yards (640 m) from target, active and wire-guidance |

Mark 14 torpedoes

The “backup” WWII infamous torpedoes, with its (now fortunately !) fixed Magnetic influence exploder. Enormous stockpiles were still in storage from wartime production, so always some were available for any patrol. They were only phased out definitely from 1975 and even lingering until 1980, mostly as practice torpedo.

In short:

20 ft 6 in (6.25 m) x 21 in (530 mm) and 3,280 lb (1,490 kg)

Powerplant: Wet-heater combustion/steam turbine with compressed air tank fuelled by 180 proof Ethanol blended with methanol or other denaturants for 9,000 yards (8,200 m) at 31 knots (57 km/h) or 4,500 yards (4,100 m) at 46 knots (85 km/h), Gyroscope guided and carrying 643 lb (292 kg) of Torpex.

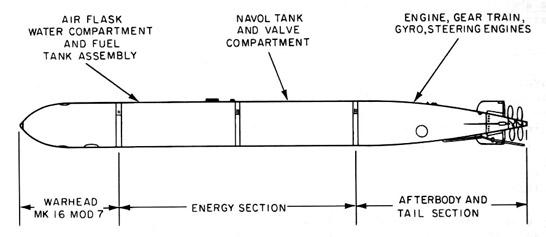

Mark 16 torpedoes

Another WW2 design, which was the successor to the Mark 14 and entered service in 1943, with some 1700 built, retired in 1975.

These were the irmproved Mark 14 essentially, replacing the troublesome Mark 14 whenever possible. Againj, large stocks available and used as practice and backup torpedoes.

In short (mod 8, the latest):

Mass 4,155 pounds (1,880 kg), 246 inches (6.2 m) x 21 inches (533 mm), Warhead 1,260 pounds (570 kg) Mk 16 HBX with Mk 9 Mod 4 contact/influence exploder

Turbine, “Navol”, concentrated hydrogen peroxide for 46.2 knots (85.6 km/h; 53.2 mph) 11,000/12,500 yards (11,430 m) range, Gyroscope guided.

Mark 48 torpedoes

Last model adopted by the Skipjacks in replacement for the Mark 14/16 they could have aboard. The Mark 48 and its improved Advanced Capability (ADCAP) variant were heavyweight submarine-launched torpedoes. They were designed to sink deep-diving nuclear-powered submarines and high-performance surface ships. They entered service in 1972 for the first mod, 1988 for the ADCAP, so it’s unlikely the latter was operated by the Skipjacks.

⚙ specifications Mark 48 TORPEDO |

|

| Weight | 3,434 lb (1,558 kg) |

| Dimensions | 19 ft (5.8 m) x 21 in (530 mm) |

| Propulsion | swash-plate piston engine; pump jet Otto fuel II |

| Range/speed setting | 38 km/55 kn or 50 km/40 kn |

| Max depth | 500 fathoms, 800 m (2,600 ft) est. |

| Warhead | 647 lb (293 kg) HE plus unused fuel, proximity fuze |

| Guidance | Common Broadband Advanced Sonar System |

Mark 45 ASTOR nuclear torpedoes

The elephant on the room. These very particular torpedoes were designed in part in respsonse to Soviet rumored small warheads tests and probably adoption on torpredoes and for general tactical use as per the new wide scale 1960s US deterrence policy.

The Mark 45 anti-submarine torpedo (ASTOR) was submarine-launched and wire-guided usable against high-speed and deep-diving Soviet submarines. It was first recommended for implementation by 1956 Project Nobska a summer study on submarine warfare. Its was 19-inch (480 mm) in diameter (at first not compatible with 21-inches tubes on Skipjack) while carrying a W34 nuclear warhead and under direct control maintained between the torpedo and submarine until detonation. It had no homing capability. The design was completed in 1960, 600 were built between 1963 and 1976 until replaced by the Mark 48 torpedo.

It is noted there since some sources states the Skipjacks could operate these, but that would need modification or at least one tube to this caliber It is not reported in Conways and other sources.

Sensors

BPS-12 radar

The AN/BPS-12 is a medium-range surface search and navigation radar, modified BPS-5 and similar to the BPS-14 radar. It uses both a periscope antenna and a conventional antenna. Last use on the Skipjach class.

BQS-4A Sonar

The BQS-4 was active sonar, here in its latest variant. The AN/BQS-4 is an active/passive detection sonar consisting in the AN/BQR-2 passive detection system and added active detection capability.

The BQS-4 active component comprised seven vertically stacked cylindrical transducers, located inside the BQR-2 chin bow dome to transmit its active “pings.”

In addition to passive listening, it can operate in either automatic echo-ranging or “single-ping” modes.

BQR-2B Sonar

No data so far.

SQS-49 sonar

Same model as used on the Skate class SSNs.

No data so far.

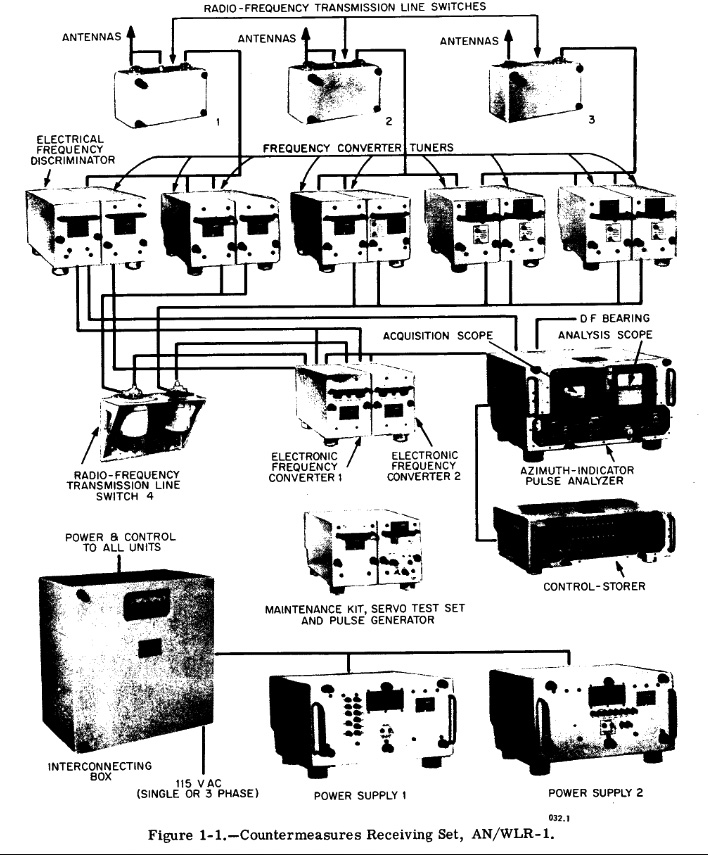

WLR-1 ECM suite

Early ECM system. From JETDS nomenclature system: W = Surface/Underwater Combined, L = Countermeasures, R = Receiver. Main electronic countermeasures applications system with a long history, instroduced in the 1960s. The AN/WLR-1 family superseded the AN/BLR-1 (1953) c1964. Bands 1 through 3 are covered by the AS-5048 (vertically polarized) or the AS-5049 (horizontally polarized) from 50-100 MHz to 160-320 MHz, up to Band 9: 7300-10750 MHz (Omni and DF)

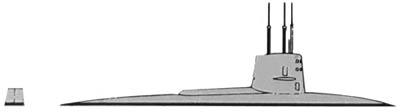

Conway’s profile

SSN-585 USS Skipjack

SSN-589 USS Scorpion

⚙ specifications |

|

| Displacement | 3,075 tons (3124 t) surfaced, 3,513 tons (3,600 t) sub. |

| Dimensions | 251 ft 8 in x 31 ft 7.75 in (76.71 x 9.6457 m) |

| Propulsion | 1 shaft S5W reactor, geared steam turbines (15,000 shp (11,000 kW)) |

| Speed | 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph) surfaced, 33 knots (61 km/h; 38 mph) submerged |

| Range | Unlimited except by food and crew fatigue |

| Test depth | 700 ft (210 m) |

| Armament | 6× 21 in (533 mm) bow Mark 59 torpedo tubes (bow), 24 torpedoes |

| Sensors | BPS-12 radar, BQS-4A, BQR-2B, SQS-49 sonars, WLR-1 ECM suite |

| Crew | 85-93 |

General assessment and influence

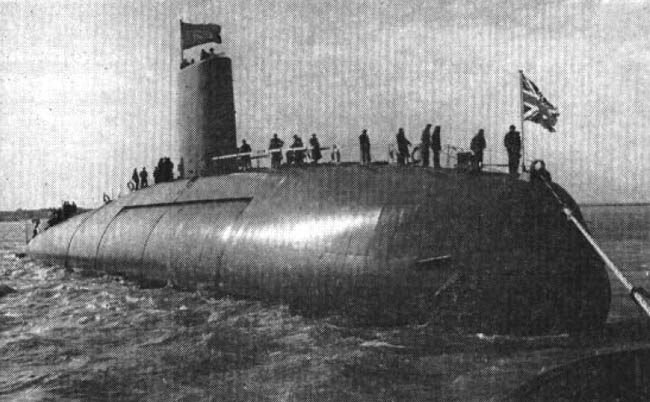

The impressive sail of USS Scuplin, with officers on top of the fairwater planes acting there as ad hoc bridge wings.

The Skipjack class submarines were designed primarily for hunting and destroying enemy submarines and surface ships. They also performed intelligence-gathering missions and supported carrier battle groups. These submarines played a crucial role during the Cold War, providing the U.S. Navy with a stealthy and capable platform for undersea warfare. The Skipjack class paved the way for subsequent classes of U.S. nuclear submarines, incorporating many design features and technologies that became standard in later classes such as the Los Angeles and Seawolf classes. The innovative hull design influenced submarine development globally, leading to advancements in submarine speed, stealth, and maneuverability. They were a pivotal development in the history of naval engineering, embodying significant technological advancements and contributing to the effectiveness of the U.S. Navy’s submarine force during a critical period of the Cold War.

USS Skipjack’s motto was “Radix Nova Tridentis” (“Root of the New Sea Power”) setting the tone until 1988. She was soon dubbed the “world’s fastest submarine” aftee her sea trials records trumpeted in March 1961. Her actual speed was a guarded secret. The speed resulting from external calculation absed on 15,000 shp, reasonable assumptions about her hull’s coefficient of drag and cross sectional area, as well as her appendage drag via algebra, resulting in 31 knots submerged, 2 knots shy of the Albacore’s best theoretical submerged speed of 33 knots.

Her maneuver capabilities included reversing direction in the distance of her own length, which ws called “flying”, and she can climbe, dive, and bank like an airplane. The antisubmarine warfare novelties created by such maneuverability and speed was an unseen benefit that would take decades to integrated into new tactics.

Shorter than later subs, she lacked the space to be upgraded with newer systems however, and the whole class suffered suffered in later years to keep old, second-class sonar equipment and fire-control. She was the reason why next designed (Tresher/Permit) opted for a constant beam middle hull, loosing some agility but gaining extra space for these future upgrades, which was kept for all next designs.

Despite these limitations, the six boats remained an effective attack submarine squadron untiol the end of the cold war, precisely because of their superior speed. Only known upgrade was the installation of a new seven-bladed propeller during their refit of 1973-1976 dependng on the boats. These replaced the noisier early five-bladed propeller used for a trans-Atlantic underwater crossing record while returning from a forward deployment in the Mediterranean. The new model was much quieted thanks to revised shape blades and more numerous ones to get a lower turning rate and thus reduce cavitation but also reducing their speed noticeably. In the end, these made for a lot of tradeoffs.

During her shakedown cruise in August 1959, USS Skipjack she became the first nuclear ship to pass through the Strait of Gibraltar and operate in the Mediterranean, even precluding USS Enteprise, Long Beach or previous USN subs for that matter. She spent time in Groton, Connecticut,to iron out problems delaying her operational entry into service, but benefiting other boats of the class in contstruction. She took part in advanced Atlantic submarine exercise from May through July 1960 and thus gained a first Navy Unit Commendation and Battle Efficiency “E” award, but her crews will gained three more during her long career.

Operationally, they were the first to truly showed the USN what a squadron of SSN can do in various theaters of operations. If supplied in bases or ships, these vessels could remained on station and patrol for up to six months if needed. The idea of entire crew shifts was just around the corner.

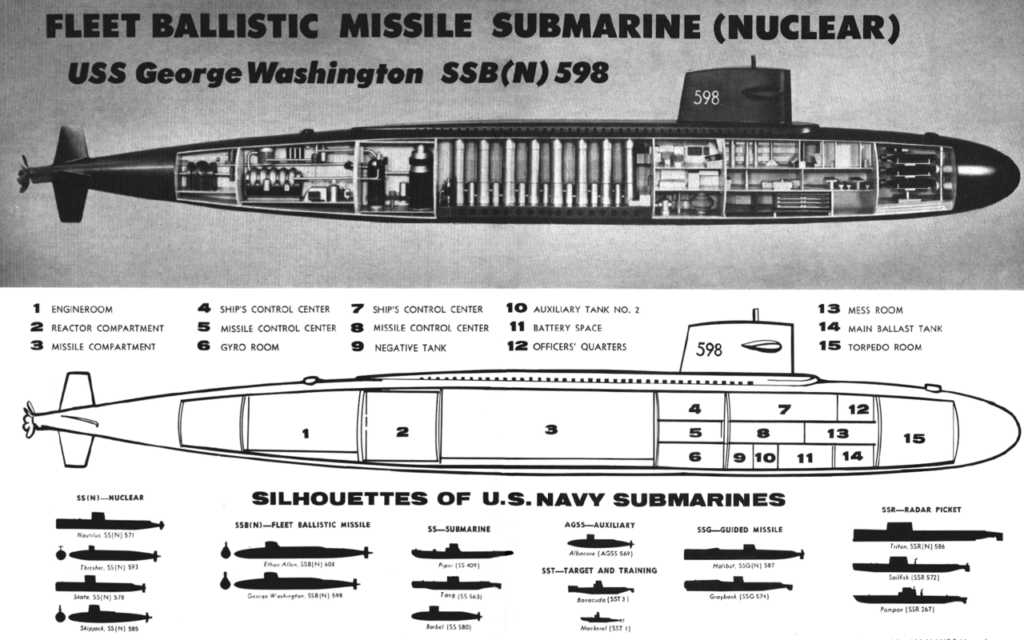

Building the first SSBNs: G. Washington class

To design the first generation of US nuclear ballistic submarines (SSBN), the Georges Washington class, also in the works at the time, engineers were instructed to just add a missile compartment to this arrangement, and it remained standard for the next 41 US 1st gen SSBNs. So the George Washington class were closely derived from the Skipjacks, so much so in fact USS George Washington herself (SSBN-598) was rebuilt from the incomplete first USS Scorpion. Her hull was laid down twice in fact, her original hull being redesigned to become the George Washington and the material for building USS Scamp was also diverted for USS Theodore Roosevelt, delayed her own construction.

The George Washington class submarines were the United States Navy’s first class of fleet ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs). These submarines were crucial in the development of the U.S. strategic nuclear deterrent during the Cold War. The lead submarine, USS George Washington (SSBN-598), was commissioned in December 1959 and they remained in service from 1959 to 1985.

They were based on the Skipjack class, just lengthened to accommodate ballistic missile launch tubes to c381 feet (116 meters) for the same beam of 33 feet (10 meters).

The Propulsion relied on the same single S5W nuclear reactor, single 5-bladed screw propeller and a lowered submerged speed of over ‘Over 20 knots’ (about 23 mph or 37 km/h) but the same virtually unlimited range and endurance, constrained primarily by the crew’s food supply and the need for periodic maintenance.

Originally they were equipped with 16 Polaris A-1 ballistic missiles, later upgraded to Polaris A-3 missiles with greater range and accuracy. But they also kept the Skipjacks’s six 21-inch (533 mm) torpedo tubes for self-defense. The crew was much larger, about 140 officers and enlisted personnel but to remain for longer on patrol, they operated on a dual-crew system (Blue and Gold crews) to maximize operational deployment time.

The George Washington class was the first to combine the stealth and endurance of nuclear-powered submarines with the strategic missile capabilities, significantly enhancing the U.S. Navy’s nuclear deterrent. They formed the sea-based leg of the U.S. nuclear triad (alongside land-based missiles and strategic bombers), ensuring a secure second-strike capability.

Their primary mission was deterrence patrols. They operated in a “deterrent patrol” mode, staying submerged and hidden for long periods to maintain the threat of a retaliatory nuclear strike.

During their service, George Washington class submarines conducted numerous deterrent patrols, maintaining a continuous at-sea presence. They set the standard for subsequent U.S. SSBNs, influencing the design and operational concepts of later classes such as the Lafayette, James Madison, and Ohio classes. They demonstrated the feasibility and effectiveness of the SSBN concept, which remains a critical component of the U.S. strategic deterrent to this day. The class comprised USS George Washington (SSBN-598), USS Patrick Henry (SSBN-599), USS Theodore Roosevelt (SSBN-600), USS Robert E. Lee (SSBN-601) and USS Abraham Lincoln (SSBN-602). Giving their new critical role, fish named seemed not fitting, and they competed with aircraft carriers in naming tradition, before the “stock” was depleted and the later classes borrowed state names, fundamentally those of Battleships with the Ohio class.

Building the HMS Dreadnought: A British Skipjack ?

The design of the prototype HMS Dreadnought is closely related to the Skipjack class with the entire aft section identical, since her hull was built around a common S5W reactor, albeit the fore section was based on earlier British studies into early nuclear submarine designs. Engineers took great care in ensuring to marry the two designs seamlessely. So from the front, both looked quite different. HMS Dreadnought’s sail was also smaller and shaped differently.

HMS Dreadnought (S101) was the United Kingdom’s first nuclear-powered submarine and marked a significant milestone in the Royal Navy’s capabilities. She was laid down in 1959, launched in 1960, and commissioned into the Royal Navy on April 17, 1963. She served until her decommissioning in 1980. She was based on the design of the U.S. Skipjack class submarine, featuring a streamlined, teardrop-shaped hull for optimal underwater performance for 265 feet (81 meters) in lenght (so greater) and a beam of Approximately 32 feet (9.8 meters).

She was powered by the same single Westinghouse S5W nuclear reactor with same single screw propeller, enabling high speeds over 20 knots (about 23 mph or 37 km/h) when submerged, but less than the original model, 28 knots (52 km/h; 32 mph) submerged. She shared also six 21-inch (533 mm) bow torpedo tubes and had a larger typical crew complement of around 113 officers and enlisted personnel.

She was the first British submarine to use nuclear propulsion, greatly enhancing the Royal Navy’s operational capabilities by allowing prolonged submerged operations and higher speeds compared to conventional diesel-electric submarines and was built with significant technical assistance from the United States, reflecting the close defense cooperation between the two countries.

HMS Dreadnought played a crucial role during the Cold War, providing the Royal Navy with a platform capable of extended submerged patrols, thus enhancing the UK’s strategic deterrent and maritime defense capabilities and conducted a variety of missions, including surveillance, intelligence-gathering, and anti-submarine warfare exercises.

As the First of Its Kind, HMS Dreadnought paved the way for future generations of British nuclear-powered submarines, influencing the design and development of subsequent classes such as the Valiant, Churchill, and Swiftsure classes. She demonstrated the viability and advantages of nuclear-powered submarines for the Royal Navy, leading to the development of a robust fleet of SSNs and SSBNs (fleet ballistic missile submarines); marked the beginning of the Royal Navy’s nuclear era, significantly enhancing the UK’s naval capabilities and its position within NATO during the Cold War. Her famous name and legacy continued the tradition of British naval innovation and excellence, dating back to the revolutionary battleship HMS Dreadnought launched in 1906, which had similarly transformed naval warfare.

Skipjack SSN-585

Skipjack SSN-585

USS Skipjack was the first of a batch of two. She was laid down on 29 May 1956, launched on 26 May 1958 and commissioned the first on 15 April 1959. Skipjack commenced 1961 operations by two weeks of training and anti-submarine warfare exercises in August and between Mayport, and Groton for fixes. In late 1960, USS Skipjack was also nearly involved in a diplomatic hazard, albeit not caught, but still clearly violating Soviet territorial waters by sailing up Kola Bay while submerged while being at some point just 30–40 yards (27–37 m) of a pier at Murmansk… Her location data recorder was deliberately disabled to prevent generation of any official record. This was all declassified after the fall of the USSR. Upon returning from this mission, She spent the remainder of the year in a restricted yard for upkeep.

In January 1962, Skipjack she was homeported to Key West, Florida and received an extensive overhaul at Portsmouth Naval Shipyard, Maine over four and one-half months. She operated next off London, Connecticut, before being prepared and depart in October for her first Mediterranean Sixth Fleet operational campaign.

She took part in many NATO exercises and was the first SSN to ever visit Toulon, La Spezia, Naples, and back to New London. While underway she earned the record of the fastest submerged transit of the Atlantic Ocean, that still stands today.

In 1963 she was taken by more ASW exercises, testing all the possibility offered by such as fast nuclear-powered attack submarine. She spent two months with NATO forces and exercises “Masterstroke” and “Teamwork”, stopping at Le Havre, and Isle of Portland, back in October.

She spent 1965 training and has a refit at Charleston until 18 October 1966. She was homeported to Norfolk, Virginia, and resumed Atlantic Fleet exercises.

By February 1967 after sonar and weapon tests she took part in Atlantic submarine exercises in March-June and spent the summer in restricted availability, Newport News. After this she took part in FIXWEX G-67 against ASW aircraft in October-November. She spent 1968 in local operations off Norfolk.

On 9 April 1969, she entered drydock for a major overhaul at Norfolk until late 1970. In 1971 she performed sound trials and weapons tests at the Atlantic Fleet Range in Puerto Rico (25 January through 5 March) and took part in NATO “Royal Night” until 9 October.

USS Skipjack underway 1970s

1972 reproduced the same routine of local operations, including the Caribbean.

By the spring in 1973, she made another Med Cruise with the 6th Fleet, homeported at La Maddalena (Sardinia) and back in September, crossing path with Hurricane Ellen while underwater.

Next were more ASW aircraft exercises, playing the role of a Soviet submarine but she was placed under certain handicaps notably a reduced designated operating area of 20 x 10 miles and she had a noise problem in her reduction gears. Adversary hunters were given her sound profile, quite unique at all times. All that was done not to accidentally launch a simulated attack on a real Russian submarine roaming around.

At the end 1973 she was sent to Groton for her mid-life refueling overhaul at General Dynamics, Electric Boat. The overhaul took all summer from 1974 until her refreshing cruise and trials by the summer of 1977. She was deployed to the Mediterranean in October, 1977and back in March 1978. She later made a 59 day ASW exercise in the northern Atlantic, halted in Scotland. Late 1978, saw her back to the Mediterranean up to the spring of 1979 eanring Comsubron 2 Battle Efficiency “E.”

From early December 1979 to mid-February 1980 she had NATO exercises, North Atlantic, speinf Xmas in Halifax. Next year same exercises saw her Mark 48 qualifications in the Caribbean, then short ops and short refit in Groton.

In June 1980, she was deployed in the Caribbean, South Atlantic, South Pacific rounding the continent for UNITAS. While operating in the Caribbean she however collided with an underwater mound but in-port inspection by divers and Navy inspection team saw little damage so she returned to UNITAS albeit Commander Plath was removed from command, having the right infos on his maps.

By late 1980 she made her transit to the Pacific Fleet for overhaul at Mare Island Naval and ended at San Diego, for an overhaul through 1981-1982.

In 1986, she made “Northern Run” to the North Atlantic Ocean and the next year another Mediterranean deployment and dry-dock time. By early 1988, her stops included Port Canaveral, and Halifax during an exercise. While USS Bonefish (SS-582) experienced a disastrous fire some TV news broadcasters confused her with USS Skipjack as she bore some resemblance.

She took part in 1988 UNITAS cruise, stopping in Puerto Rico and Caracas, Cartagena, and transited the Panama Canal, but one of her motor-generator broke down. She was dry-docked for repairs in Groton.

Her authorization to dive expired in March 1989 after the 1987 inspection of her so she was scheduled to be decommissioned. In March-June, she training students at the Submarine Officer Basic School in Groton, always surfaced. Her anchor got stuck at some point and freed by Divers from Groton. She had her last dry-dock fix for about $75K and transited to Norfolk. There, she became support boat for for another submarine in sea trials. She then entered NNSDDCO in October for decommissioning on 19 April 1990 and she was recycled via the nuclear Ship and Submarine Recycling Program 1 September 1998.

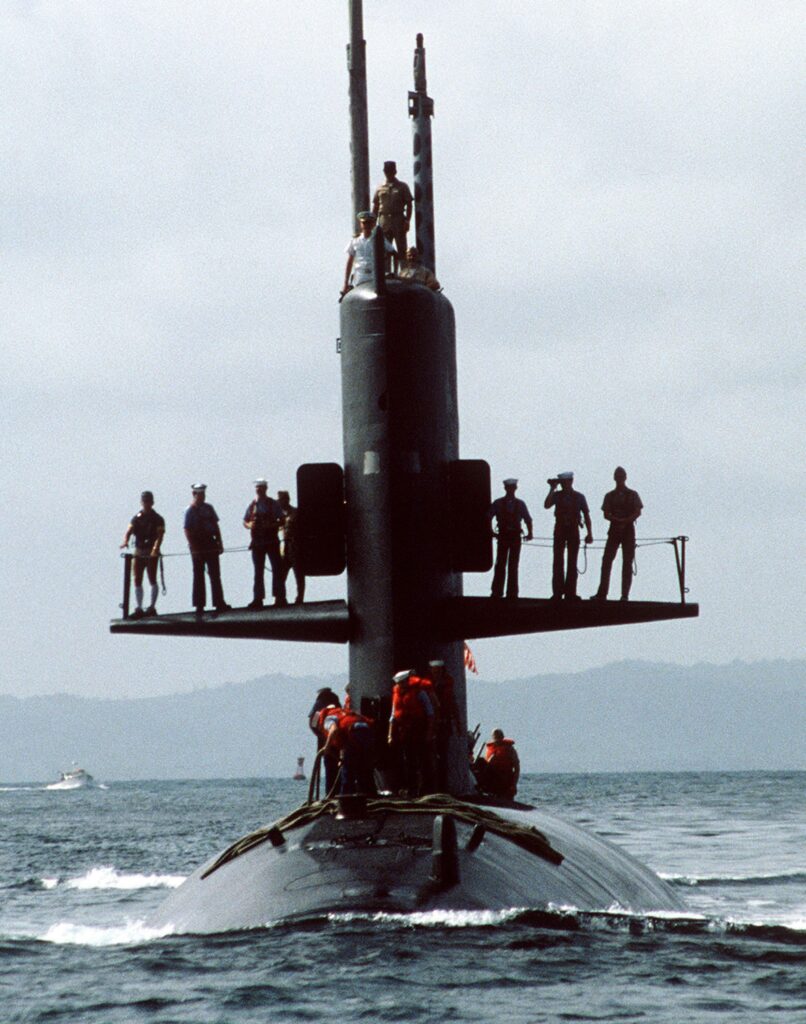

Scamp SSN-588

Scamp SSN-588

USS Scamp underway 1970s

USS Scamp was ordered to Mare Island Naval Shipyard and laid down on 23 January 1959, launched on 8 October 1960, commissioned on 5 June 1961. After four months of advanced trials and training off Bremerton, Washington but also San Diego and Pearl Harbor she was in Vallejo, Mare Island for fixes. After her final acceptance trials she started local operations off San Diego, she lost lost her screw on 4 December 1961, towed back to Mare Island.

April 1962 she made her first Westpac until July, local waters until September, and second Westpac. Back to San Diego, February-March 1963 drydock overhaul. third WestPac. Advanced training and ex. off Okinawa, back October 1963. West Coast ops. til June 1964,, 4th Westpac, back San Diego September 1964.

Overhaul Mare Island January 1965. June 1966 installation SUBSAFE package. Training cruises San Diego. Local ops. San Diego til mid-1967. 28 June, new Westpac, 7th Fleet, opertations off Vietnamese coast, back 28 December 1967.

Local ops til May 1968. 11 May Pearl Harbor and back 19 May-15 June, San Francisco, Mare Island restricted availability (RA), San Diego 16 July.

Local ops til 1969. 1 November Puget Sound regular overhaul to January 1971. HP Bremerton. HP San Diego, 12 February 1971, Pearl Harbor, 27 July, new Westpac. 30 August Subic Bay, 7th Fleet ops, not Vietnam. San Diego 2 February 1972, redeployed South China Sea summer, back 1 August. RA Puget Sound until 28 November, local ops. San Diego til December.

29 March 1973 departed for Pearl Harbor 5-10 April, Yokosuka, 23 April Vietnam ops until 1 September, Guam, Pearl Harbor 10-15 September, back San Diego 21 September, local ops and UNITAS XIX.

1980 HP Groton Naval Submarine Base New London (Connecticut) first Mediterranean tour October 1982-March 1983. Ops. Libyan coast, Line of Death Muammar Gaddafi.

Fall 1983 won 2nd BATTLE EFFICIENCY SERVICE AWARD. July 1984 UNITAS XXV South America.

24 February 1987 storm North Atlantic, attempted to rescue crew sinking Philippine freighter MV Balsa 24, she had a flooding, damage to her sail: Early retirement but saved the life of one crew member, 18 died. USS Scamp was decommissioned, stricken 28 April 1988, recycled via the nuclear Ship and Submarine Recycling program 9 September 1994.

Scorpion SSN-589

Scorpion SSN-589

USS Scorpion in 1967, note the two-tone experimental livery

Built at Electric Boat USS Scorpion was laid down on 20 August 1958, launched 29 December 1959 and completed on 29 July 1960. Commander Norman B. Bessac was her first captain and she was assigned to Submarine Squadron 6, Division 62, New London 24 August. Exercises 6th Fleet, NATO navies. Local ops. Eastern Seaboard til May 1961. 1962, awarded a Navy Unit Commendation.

Norfolk HP, became nuclear submarine warfare tactics spec. base. Exercises Atlantic Coast, Bermuda, Puerto Rico. Overhaul June 1963 to May 1964. 4 August to 8 October transatlantic service. Spring 1965, European waters ex.

In 1966, special operations. Captain was awarded a Navy Commendation Medal, crewmen cited for meritorious achievement. Declassified: Scorpion entered inland Russian sea in “Northern Run” 1966, filmed a Soviet missile launch through periscope.

Overhaul 1 February 1967 Norfolk, refueling, emergency repairs, SUBSAFE not fitted. CNO Admiral David Lamar McDonald approved her reduced overhaul on 17 June 1966. Late October 1967 refresher training, weapons-system acceptance tests under Francis Slattery off Norfolk, sailed 15 February 1968 for Mediterranean deployment, 6th Fleet until May and back.

Reported several malfunctions, notably freon leakag. Electrical fire in escape trunk after leak shorted shore power connection. Escorted SSBNs off US Naval base Rota, provided noise cover for USS John C. Calhoun when entering Atlantic to deceive Soviet intelligence trawlers and SSNs (November-class) out of Rota.

Stayed in the Azores, located an Echo II-class and guided-missile destroyer. Then headed for Naval Station Norfolk but disappeared in May 1968.

Last message relayed by Nea Makri, Greece, reported at 15 kn under 350 ft and “to begin surveillance of the Soviets.” Awaited at Norfolk on 27 May but overdue for hours.

Atlantic fleet launched a sea and air search from 28 to 30 May, up to 55 ships and 35 aircraft. USS Scorpion and crew declared “presumed lost” on 5 June. Name struck on 30 June. Seach went on using Bayesian theory, same used to locate lost atomic bombs.

Oceanographic research ship Mizar later located sections of her hull 400 nmi (740 km) SW of the Azores under 9,800 ft (3,000 m) based on sound tapes from SOSUS containing sounds of her implosion. Court of inquiry made based on photos from bathyscaphe Trieste II. Now the subject of the loss of Scorpion had been well covered in mass medias, so better to keep it short. The cause of sinking was never firmly established.

Sculpin SSN-590

Sculpin SSN-590

USS Sculpin via Miraflores gate, Panama

USS Sculpin was ordered to Ingalls Shipbuilding in Pascagoula, Mississippi. She was laid down on 3 February 1958 and launched on 31 March 1960 commissioned on 1 June 1961.

Sculpin left Pascagoula on 8 June for HP San Diego. Shakedown training, special trials and tests off Puget Sound. August, Pearl Harbor and back. Mare Island fixed until March 1962.

May first Westpac, Pearl Harbor, special operations, visited Naha in Okinawa, back in August. Local ops, overhaul Mare Island January 1963. From San Diego started local operations, first submarine leaving Mare Island after the Thresher Disaster.

Pearl Harbor by December, new westernPac marred by defective piping, back 25 February 1964. 8 April sailed again to 7th Fleet. Stopped ay Sydney and Subic Bay, Okinawa. Awarded a Navy Unit Commendation. west coast Ops San Diego-Bangor over 25 months.

27 November 1966 sailed to Naha, Westpac, back 11 May 1967, local opes. Extended training cruise 27 July to 26 October. 11 November demonstration dive for President Lyndon B. Johnson.

2 January 1968 started major overhaul until 22 January 1969. Shakedown training, West Coast 22 August, upkeep until 8 September. Local ops until 6 February 1970, sailed to Pearl Harbor, Westpac.

Okinawa 6 March, Subic Bay, Hong Kong, Yokosuka, back 21 August. Local ops. til 4 January 1971, RA Mare Island until 16 April. November 1971 sailed for secret deployment tracking weapons smuggling trawlers South China Sea from 5 January 1972. 10 April 1972 was posted south Hainan. Followed smugglers for 2,500 miles to Southern coasts of South Vietnam. 24 April a South Vietnamese destroyer sank the Chinese trawler. Back 24 July.

Berthed San Diego. 2 February 1973 Mare Island RA, local ops. under command of Captain James Joseph Pistotnik until 12 November. New Westpac January 1974.

1975 refueling overhaul Bremerton. 1977 local ops. San Diego but rammed by USS Snook (SSN 592) while trying to tie up next to her. Damage to her bow tube outer doors, 6 weeks drydock.

RIMPAC April-May 1978. June 1978, Panama Canal, then Curaçao, HP Groton, Connecticut. Ex. “Northern Wedding”, stop Holy Loch, Scotland.

February 1979 Mediterranean Ops. 1982 overhaul Mare Island but in trials suffered severe angles in a crashback maneuver submerged. 1984 Sculpin was in picket duty between Syria and USS New Jersey as she shelled Beirut..

USS Sculpin was decommissioned on 3 August 1990 and recycled via the nuclear Ship and Submarine Recycling program 30 October 2001.

USS Shark underway 1985

Shark was ordered to Newport News Shipbuilding, laid down on 24 February 1958 and launched on 16 March 1960. She was commissioned on 9 February 1961. Shakedown in Caribbean Sea, May 1961. Post-shakedown repairs, final acceptance, first deployment Mediterranean Sea, 6th Fleet from 12 August 1961 until 14 November 1961. September–October visited Piraeus, hosted the entire Greek Royal family aboard, cruise above/underwater.

29 January 1962 was in Bermuda 2 weeks training. North Atlantic 15 March-23 May, stopped Portsmouth. 25 August other 2 months North Atlantic. Back to Norfolk, RA until 7 January 1963.

SUBFALLEX North Atlantic 7 August-24 October, stop Faslane, Scotland. 1963 local ops. and Caribbean Ex.

22 March 1964 departed for SUBSPRINGEX, back 21 May. 25 June Charleston overhaul until 7 June 1965. 7 April awared Navy Unit Commendation for meritorious service.

Sea trials 7 June, but July, 7, suffered damage, forward oxygen system, repairs Charleston. 9 October sailed to Key West, Florida, TT tests, wire-guided torpedo development project.

Back Norfolk 25 October 1965, local ops until 8 January 1966.

Special operations until 24 March 1967, stop Holy Loch. 12 April, awared a second Navy Unit Commendation. 16 May Halifax, first visit of a nuclear ship to a Canadian port. Operated with RCN ASW units. Used in a Naval Department educational film for training and PR.

11 June 1967 refuelled at Norfolk until March 1968. Local ops. Resumed ops. 9 August 1971, 1972 refresher training, trials East Coast, Med TOD from 31 May to 19 November 1972. HP New London.

1978: UNITAS and Mediterranean deployment. 1980, exercises Atlantic Fleet and RCN.

Overhaul Mare Island September 1981 to May 1983. USS Shark was decommissioned on 15 September 1990 and recycled via the nuclear Ship and Submarine Recycling program 28 June 1996.

Snook SSN-592

Snook SSN-592

USS Snook off Rio de Janeiro in 1984

USS Snook was ordered with USS Sculpin to Ingalls Shipbuilding, laid down on 7 April 1958, launched 31 October 1960 and completed on 24 October 1961.

After shakedown Puget Sound area, departed San Diego 23 June 1962 fir Westpac 7th Fleet, back 21 December. 1 February 1963 Mare Island extensive hull improvements. From 23 August, local ops and new Westpac, then back, Mare Island 3.5 months repairs, installation new electronic equipment.

Local ops. San Diego area, 19 March 1965, six-month WestPac. Stopped Sasebo, Chinhae (South Korea). Awarded Navy Unit Commendation. Six months sound trials, drydock. 16 April 1966 new WestPac Okinawa, Yokosuka, Sasebo, Chinhae, Subic Bay, back 19 November. 19 March 1967 Puget Sound, 14-month overhaul, refueling. 30 June 1968 back San Diego local ops. Sank ex- USS Archerfish (AGSS-311).

1969 ASW exercises. May, new WestPac for seven months, back 22 December.

Late January 1970, exercise “Uptide” with 1st Fleet. June to September drydock Mare Island, back San Diego, six-month WestPac, back 12 July 1971, local ops.

Operations in 1972, 13 May sailed for 2-month tour Vietnam, stopped Kaohsiung, Taiwan. Drydocked Puget Sound. 10 January 1973 sailed for 8th WestPac, Seventh Fleet. Stopped in Guam.

Back to San Diego 16 June. 4 months Sonar evaluation tests. 26 November, COMTUEX 12-73, Mare Island refueling overhaul. Logs missing for the next years.

She was decommissioned on 14 November 1986 and recycled via the nuclear Ship and Submarine Recycling program 30 June 1997.

Read More/Src

USS Scamp and crew standing on her sail planes.

Books

Gardiner, Robert and Chumbley, Stephen, Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships 1947-1995

Hutchinson, Robert, Jane’s Submarines, War Beneath The Waves, From 1776 To The Present Day. Harper Paperbacks 2005..

Polmar, Norman (2004). Cold War Submarines: The Design and Construction of U.S. and Soviet Submarines, 1945-2001. Brassey’s.

Links

navypedia.org/ skipjack.htm

web.archive.org/web/ www.personal.psu.edu

usstorsk.org/

oneternalpatrol.com uss-scorpion-589.htm

navweaps.com/ WTUS_PostWWII.php

apps.dtic.mil/ /ADA054698.pdf

apps.dtic.mil/ ADA054698

militaryperiscope.com/ anbqs-4/overview/

navy-radio.com/manuals/

nvr.navy.mil/ SSN_590.HTML

hazegray.org/danfs/submar/ssn590.txt

hazegray.org/danfs/submar/ssn592.txt

navsource.org/archives/08/08592.htm

navsource.org/archives/08/08590.htm

jproc.ca/sari/counter.html

en.wikipedia.org/ Skipjack-class_submarine

Category:Skipjack_class_submarines

Videos

1960s U.S. NAVY ASW ANTI-SUBMARINE WARFARE EXERCISE USS SHARK SSN-591

Documentary on USS Scorpion

Model Kits

Main query on scalemates, all models

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign