Implacable class Aircraft Carriers

United Kingdom: HMS Implacable, Indefatigable (1942)

United Kingdom: HMS Implacable, Indefatigable (1942)

WW1/WW2 RN Aircraft Carriers:

ww1 seaplane carriers | Ark royal (1914) | Campania | Furious | Argus | Hermes | Eagle | Courageous class | Ark Royal (1936) | Illustrious class | Implacable class | Colossus class | Majestic class | Centaur class | Unicorn | Audacity | Archer | Avenger class | Attacker class | HMS Activity | HMS Pretoria Castle | Ameer class | Merchant Aircraft Carriers | Vindex classThe Illustrious near sister ships

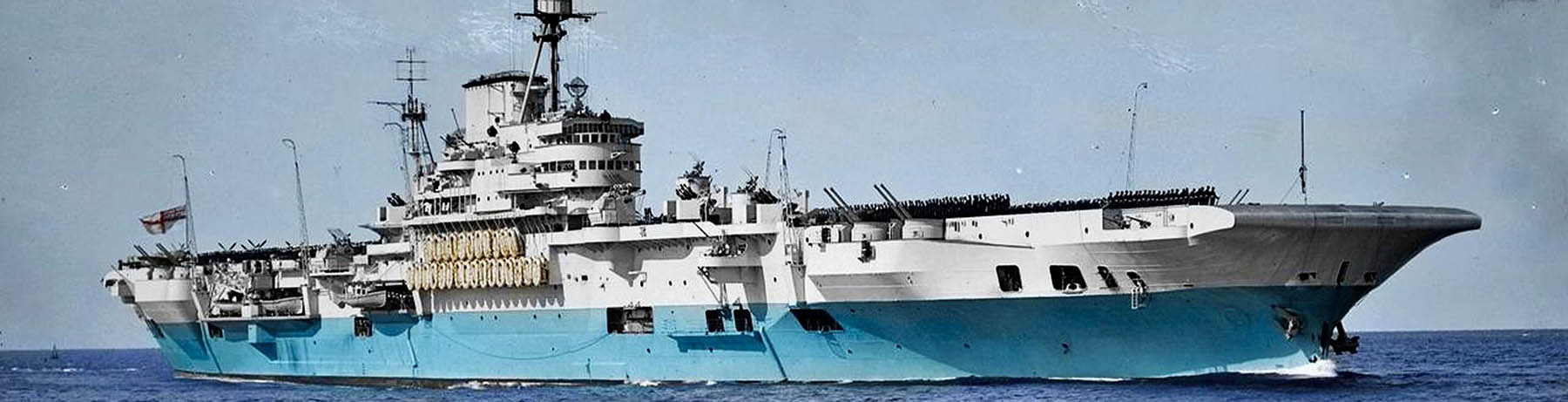

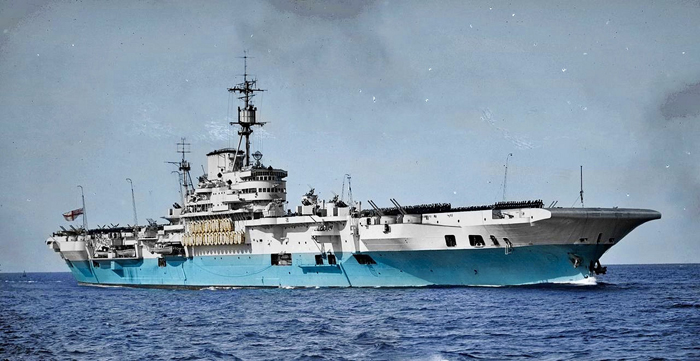

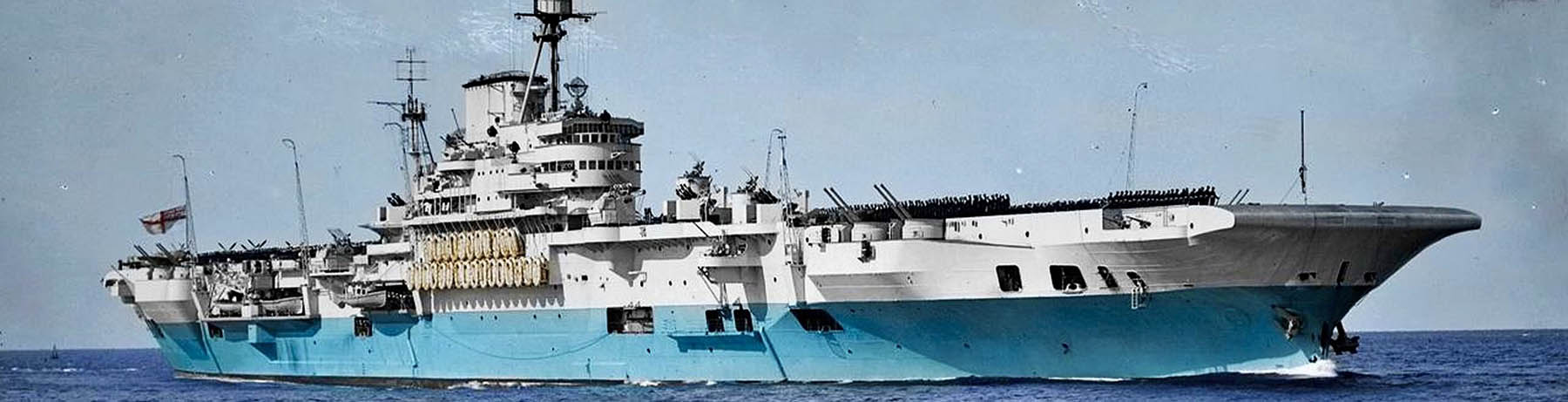

The Implacable-class were two aircraft carrier of the British Royal Navy in World War II, closely derived from the Illustrious class, but faster and with more aircraft onboard, while still keeping the benefit of being fully armored. They were initially assigned to the Home Fleet from 1944 and saw action in Norway, notably agains KMS Tirpitz and right after this, assigned to British Pacific Fleet (BPF) until the end of the war.

In fact, HMS Indefatigable was the first British Capital ship to go to the Pacific, attacking Sumatra en route, then participating to Operation Iceberg (Okinawa) while her sister ship HMS Implacable was delayed by a refit and only arrived in June 1945, both raiding the Japanese Home Islands in the summer. HMS Indefatigable continued operations and ferried Allied troops and POW back home, before starting a cold war career: HMS Implacable as training carrier, Indefatigable converted also for it, and modernized, followed by Implacable in 1952. Their major modernisation was however cancelled as too expensive and lengthy and they decommissioned in 1954, sold 1955–1956, having less ten years of ininterrupted service. As armouredcarriers.com put it, “incomprehensible”.

Design development 1937-39

The genesis of the Implacable class went back all the way to the genesis of the Illustrious class. The choice of an armoured hangar, of it sperfectly protected the air group and shown its value during WW2, both in the Mediterranean and Pacific, had its major tradeoff: A very small air group, less than half the one carried by the Yorktown class ! – If workarounds were found, like more versatile naval planes such as the Fairey Fulmar a fighter/observation/light bomber model, and later carrying a permanent extra air park on the deck, at the time, the Illustrious design was still seen by some in the Royal Navy with great scepticism.

The initial Illustrious class were planned with six ships, in the hope they could operate by pairs to combine larger air groups, with six vessels planned, of which four eventually constituted the proper Illustrious class (with HMS Indomitable as its own sub-class), while the remainder two were considered for improvements. The biggest class of fleet aircraft carriers of the Royal Navy in fact was split into three groups with significant differences. The third was to be greatly enhanced, called the Implacable group. Among modifications asked in 1938-39 were a two-level hangar, increased planes onboard, four shafts and a reworked flight deck with no longer roundabouts but square ends, gaining space.

The question of tonnage

The Implacable class were planned in the the 1938 Naval Programme and were to remain in the peacetime 23,000 long tons (23,000 t) limit allocated by the Second London Naval Treaty. Many improvements were seeked out, like a top speed of 32 knots (59 km/h; 37 mph) which urged a fourth steam turbine and shaft (so four instead of three). The additional weight was offset by reductions in armour thicknesses, in the hangar deck and bulkheads. The Director of Naval Construction worked on design D, another modified Illustrious design to carry an additional dozen aircraft for 48 total, in a lower hangar, and the already planned additional machinery, meaning even more armour.

Two hangars and a dilemna

General outline

Engineers tried hard to squeezes out as many internal space as possible, with a hangar height down to 13 feet 6 inches (4.1 m) (upper) just enough for the new Fairey Albacore to fit in, and 16 feet (4.9 m) for lower one to fighters. But it was soon reversed to accommodate taller aircraft, while the upper hangar was raised to to 14 feet (4.3 m). Design D with the sum of all these modifications as at last was submitted to the Board of Admiralty, on 2 August 1938. It was approved on 17 November after weeks of discussions and amendments.

In April 1939 there was an ultimate change, before the keels were laid down: The lower hangar was furher reduced to 14 feet as the main armour was raised to 2 inches (51 mm). No amphibians would be carried as a result, and indeed, the TBs were often carried up and figher down in practice, with 2-storey lifts to manage them.

Construction

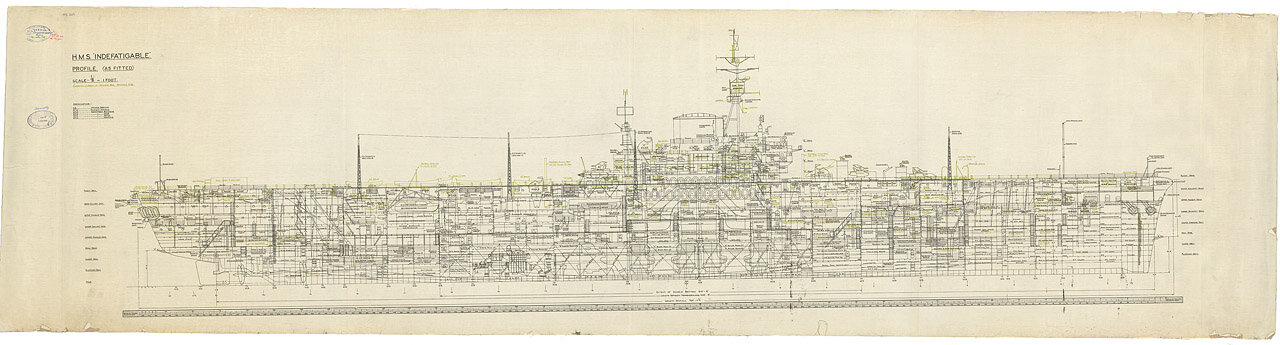

Launch of HMS Indefatigable, December 1942.

The last blueprints were drafted in detail, and transmitted to the chosen yards, Fairfield Shipbuilding and Engineering Co., Govan, Scotland for HMS Implacable, laid down first, on 21 March 1939 as the ink of the last blueprints was still not dry, and John Brown & Co., Clydebank, Scotland for HMS Indefatigable on 3 November the same year, as the war already started. However the latter yard was able to built and launch way faster, despite of the war: Construction was almost suspended and later relaunched, with enough peronal and resource, but much delayed: Both were launched in December 1942, Indefatigable just two days ahead of her sister-ship and yet most authors choosed implacable as the lead vessel of the class due to her earlier keel laying and the war disruptions.

December 1942 meant they spent three full years in hull construction, almost four for the first (From early 1939 to 1940, 1941, to late 1942); As a result, their completion was also delayed, slipping to May, 3, 1944 for Indefatigable, first again, and August, 28, for Implacable. The usual training and shakedown delays meant they really had the end of 1944 and 1945 to serve with distinction: By the time, Allied forces were battling their way towards Berlin in western Europe and Italy, there was practically no naval operations in the Mediterranean, the “battle of the Atlantic” was now mostly won, and only the Kriegsmarine’s Norwegian threat remained, for a time. Due to many factors, notably the crippling issue of peacetme tonnage they proved too small to operate jets after the war and this limited their active service to a few years (both sold for scrap in 1955-56). Not a bargain for the taxpayer money…

Design

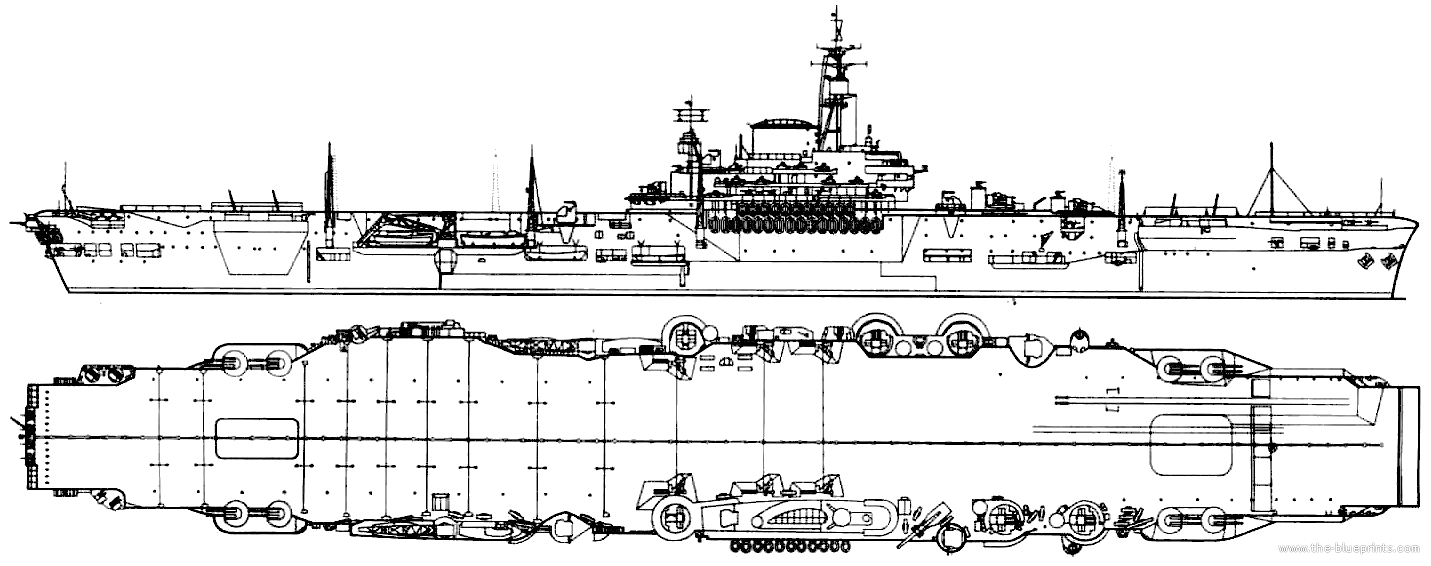

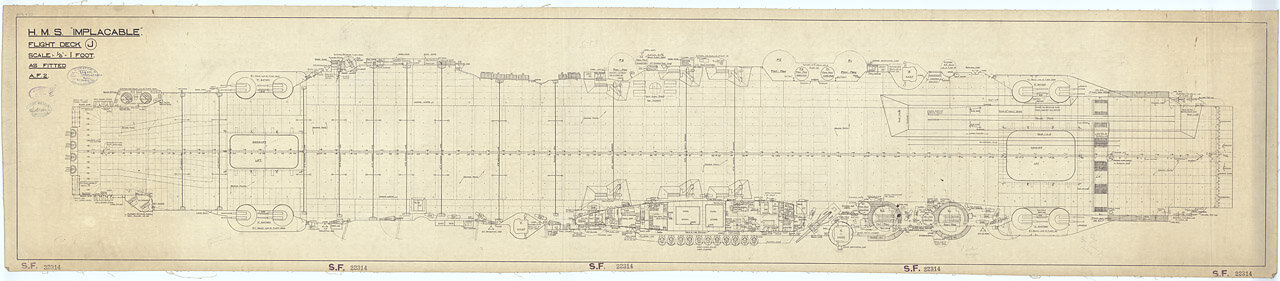

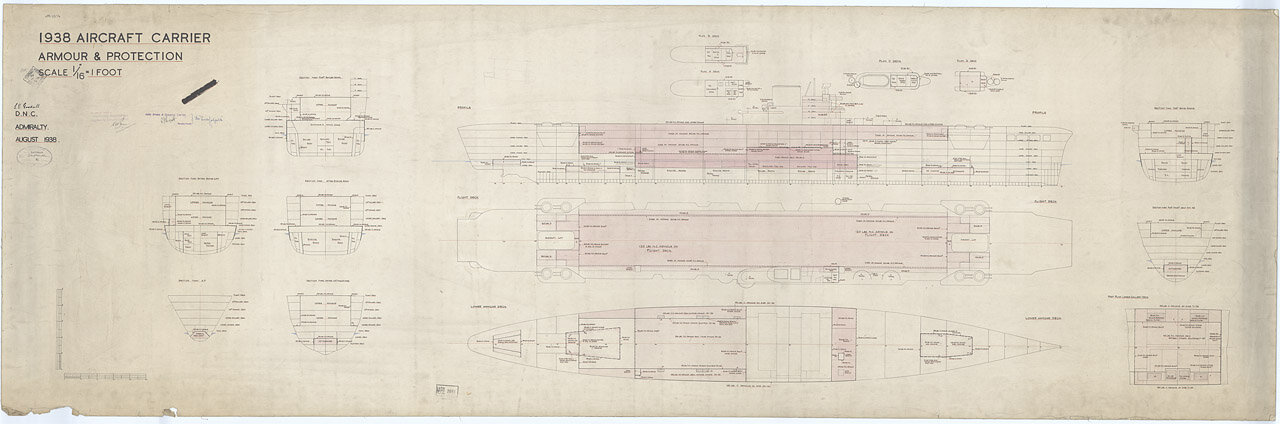

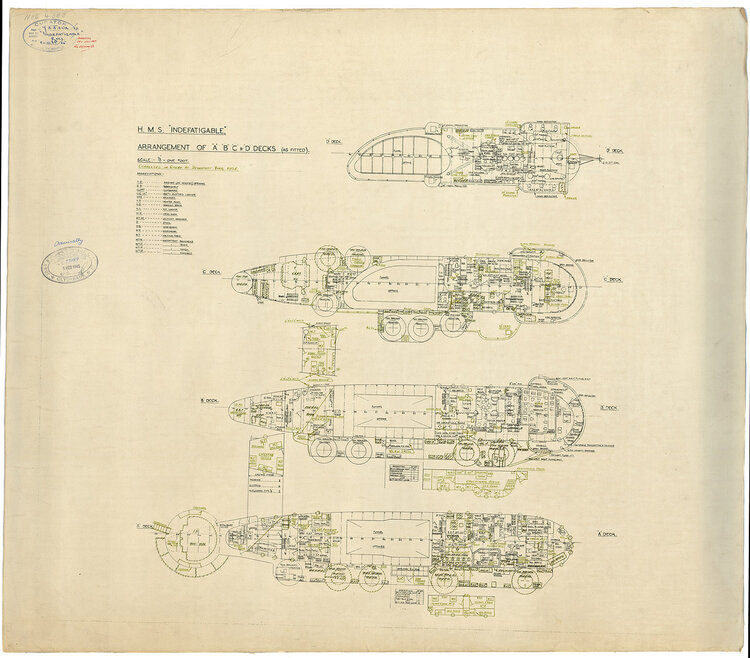

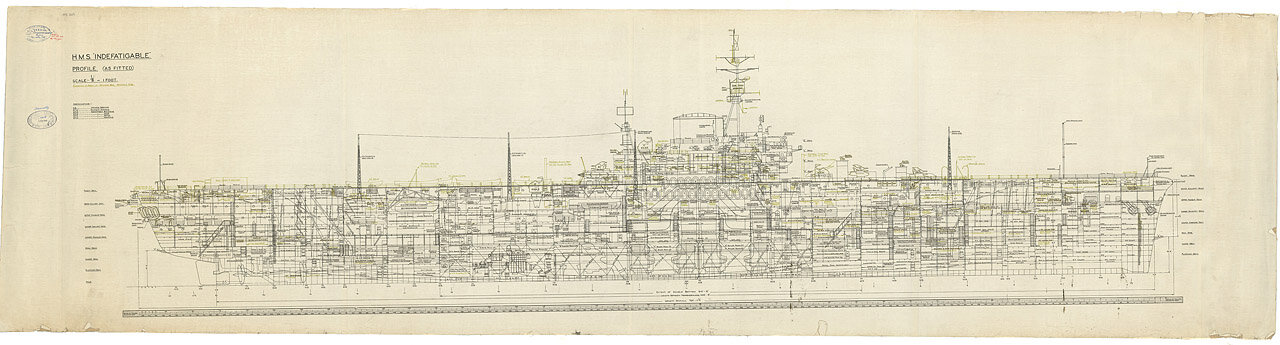

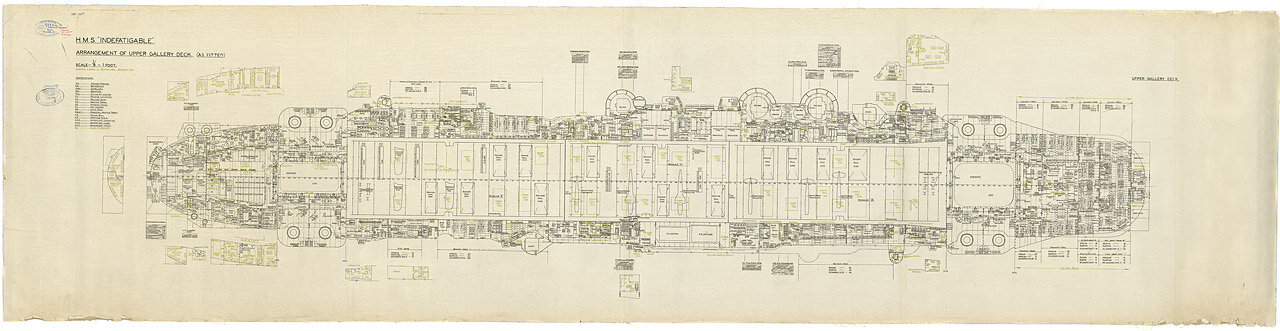

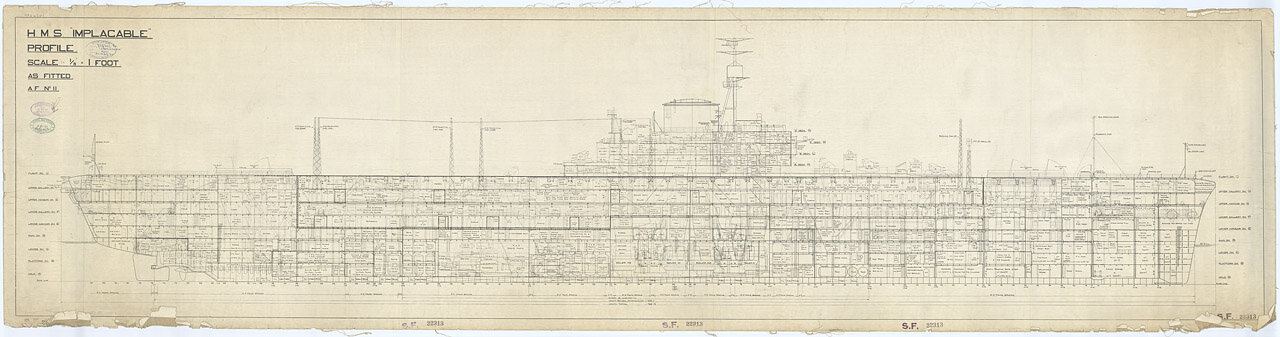

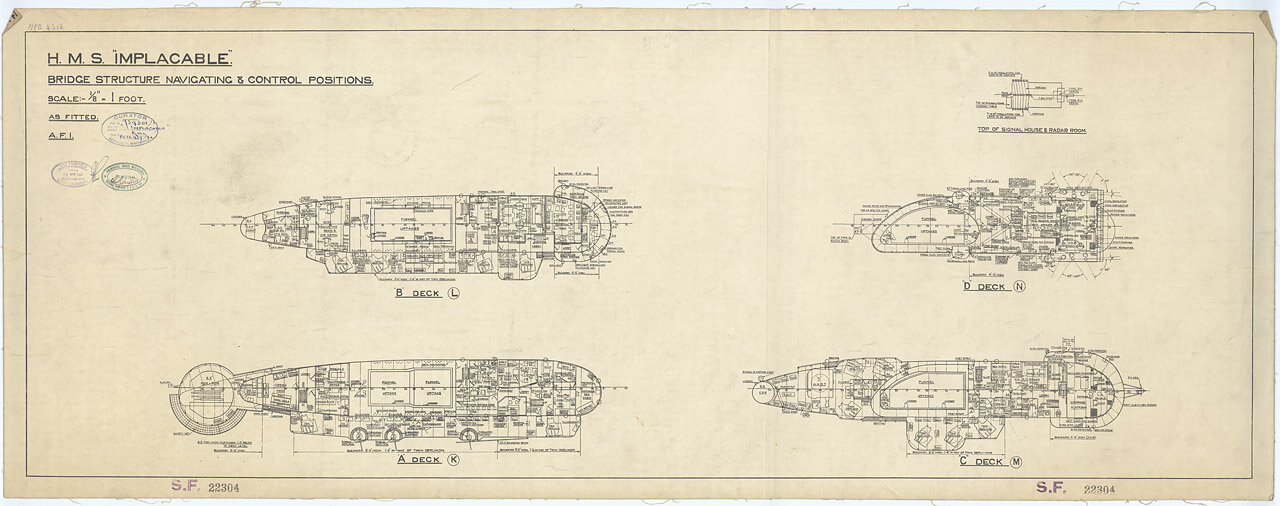

The HMS Indefatigable/Implacable 1938 blueprints.

Hull

Overall design was the same, however with slightly revised dimensions: With 766 feet 6 inches (233.6 m) long overall (20 feets longer) or 730 feet (222.5 m) at the waterline (30 feets longer there), they were not however beamier, still with the same 95 feet 9 inches (29.2 m) at the waterline for a greater draught however, of 29 feet 4 inches (8.9 m) deeply load (versus 28 fr 10 in or 8.8 m). They were significantly overweight, displacing 32,110 long tons standard and 32,630 tons deeply loaded, way more than the 23-26,000 tons of the Illustrious. Metacentric heights were 4.06 feet (1.2 m) (light), 6.91 feet (2.1 m) (deep load) and complement reached 2,300 officers and enlisted men in 1945.

Armour Protection

Philosophy

Like the previous vessels, the Implacable class main advantage was their armoured hangar. We will not swelve again into the development of this concept and details, that are related in the development of the Illustrious class carriers. The concept was essentially to put “all the planes in the same basket”, a large, entirely enclosed hangar under layers of protection above (the main flight deck was armored), the sides, and even two large bulkheads, creating some sort of “citadel bis”, above the main citadel.

When the doors accessing to the external lifts were fully enclosed in high alert, this internal armored cocoon perfectly protected the air group. The concept proved its utility in the amazing punishment that took several of the Illustrious class in the Mediterranean. It impressed so much the USN (which privileged aicraft capacity over protection, but tried to do some improvements on their Essex class) that at some point even wanted to purchase one of the British armoured carriers.

However this concept came with a massive tradeoff, the single armoured hangar was quite small, and these fleet carriers carried a very small air group, about 30-45 planes, as much as a twice smaller escort carrier. This imposed the FAA to seek out versatile models such as the Fulmar, at the same time fighter, light bomber and recce model. In operation, these small air groups had far less appeal than the Essex famous “sunday punch”, leaving a complete fighter squadron as CAP for protection while the rest were in flight for a strike.

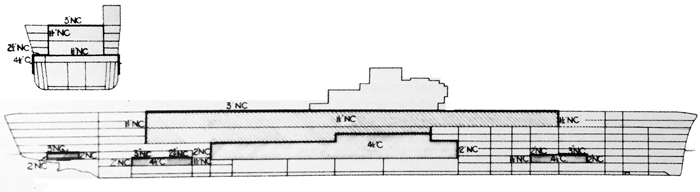

Details of the Implacable’s protection

The small air group critics eventually won their point, and it was decided to modify the next two of the “illustrious type” carriers to be heavily modified in order to carry more planes. The only way to achieve this, was to cram two hangar, one over the other, doubling the parking surface. Engineers managed to to this even without making the ships too high, or top heavy, which was nothing but quite an achievement.

The flight deck was protected by 3 in (76 mm) of armour, like the previous ships, with side protected by 1.5 inches (38 mm) walls, far less than the 4.5 in (114 mm) of the Illustrious, and just 2-inch bulkheads (against 4.5 in previously). None of the extra 51 mm (2 in) extra armour was installed when the top hangar height was reduced as a tradeoff. The hangar deck ranged from 1.5 to 2.5 inches (38 to 64 mm) in thickness. By compromising on protection the engineers granted the additional air group but this was nowhere near the very thick protection of their forebearers. This was to be demonstrated in the Pacific.

For conventional protection, the waterline armour belt reached 4.5 inches (114 mm), but on the central section, making an armoured citadel behind the lower hangar deck. This citadel was close by 1.5 and 2-inch transverse bulkheads. The underwater protection counted on eavy compartimentation creating a buffer around the engines rooms and boilers rooms. These compartments could be liquid and air-filled to use overpressure, in a way similar to that of the Illustrious class. This was calculated to resist a 750-pound (340 kg) warhead. Main ammo magazines, outside of the citadel, had their own armored boxes, 2 to 3-inch thick for their roofs, 4.5-inch for their sides and 1.5 to 2-inch for their bulkheads, comparable to the previous class.

Propulsion

Indefatigable machinery control room

Their propulsion system was improved also compared to the previous vessels, noytably to cope with the additional displacement: Four Parsons geared steam turbines instead of three, so four shafts and propellers, fed by steam coming from eight Admiralty 3-drum boilers (six on the Illustrious). Total output was then 148,000 shaft horsepower (110,000 kW) instead of 111,000 on Illustrious, which enabled a top speed of 32.5 knots (60.2 km/h; 37.4 mph), versus 30.5 kts.

Sea trials showed less stellar performances, 31.89–32.06 knots (59.06–59.38 km/h; 36.70–36.89 mph) respectively on both carriers, based on 150,935–151,200 shp. They carried 4,690–4,810 long tons (4,770–4,890 t) of fuel oil, enough for a 6,720–6,900 nautical miles (12,450–12,780 km; 7,730–7,940 mi) range at 20 knots, way better than the Illustrious’s 10,700 nm at 10 kts, so half that speed.

Armament

4.5 inch guns of the Implacable class. Note they were completely “buried” in the flight deck not to create any obstacle.

It was essentially the same s the Illustrious class, although provision was made for lighter AA during completion, due to war experience.

Eight twin QF 4.5-inch Mk.II dual-purpose guns

They were mounted in eight powered RP 10 Mk II** twin-gun turrets in sponsons on each corner of the hull. unlike the Illustrious, and also a result of war lessons, the turret roofs were flat and flush with the flight deck. They could fire shells at 2,449 ft/s (746 m/s), 12 rpm, to 20,760 yards (18,980 m) and at +45° up to 41,000 feet (12,000 m).

Five Octuple, one quad QF 2-pdr anti-aircraft guns

40 mm Mark VIII “pompom” AA octuple mounts.

40 mm Mark VIII “pompom” AA octuple mounts.

This was not a massive improvement over the Illustrious class, as the latter had six octuple mounts. Trust was placed more on the Oerlikon guns, absent from the previous designs. These mounts were placed in front of the main island (two) and one superfiring aft (quad), and three on the opposite side, all octuple. Potentially, the quad could be replaced by an octuple and another placed on the deck below, so making for a total of seven octuple (48 guns). They maximal range 6,800 yd (6,200 m), and rate of fire about the same as the Bofors.

Oerlikon 20mm anti-aircraft guns

As completed, they carried 17 to 21 of them, in single mounts, but until the end of the war, they would have up to 60 in all. In the Pacific, this started to change and some Bofors started to replace the 20 mm, which had a maximum range of 10,750 yd, more likely to shot down a Kamikaze. In 1946, Oerlikons started to be exchanged for Bofors guns, 11–12 Bofors guns and 19–30 Oerlikons in the end;

Fire Control & detection

Rear island of HMS Implacable, showing the rear Type 285

The 4.5-inch guns were controlled by four Mk V* (star) M type fire-control directors. Each was topped by a Type 285 gunnery radar, two were located on the flight deck’s edges, and the remainder on top and fore and aft of the island, plus a third aft of the funnel. A fourth director was on the port side of the hull below the flight deck. They used a Fuze Keeping Clock AA fire-control system for gunnery calculations before sending their data. The Vickers 2-pdr “pom-pom” had each theior own mounted Mk IV director, using a simple range Type 282 gunnery radar.

Also the tripod carried a Type 293 target indicator radar and the Type 277 surface-search/height-finding radar was mounted on the bridge. The Type 279 and Type 281B early-warning radars (based what the Victorious hate later in this war, but for navypedia, they carried a type 279, type 272, and type 277 as completed. Mention of the Type 281B starts in 1945 for both, as the Type 293, unchanged but in 1950, teir six FCS radars were swapped for fove Type 282. They were discarded with these.

Air Facilities

Both carriers were longer, and their flight deck had squared ends, not rounded as in previous designs. This enabled more usuable surface, for a total of 760-foot (231.6 m) with a maximum width of 102 feet (31.1 m). The particular design of the flight deck enabled more paking spaces on the sides, especially aft, where the width was twice that of the landing deck end. There was a single hydraulic H-III model aircraft catapult port forward. Across it was a folded safety net for emergency landings;

The catapult was capable of launching 20,000 lb loads at 56 knots, or 16,000 at 66 knots and American-built aircraft, without the one-ton trolley running on the new twin tracks. This was a weight saving, and as the planes were now launched tail-down, gained 4 knots. The arrester gears were the same as before, but capable of restraining heavier loads, nine aft, three forward. Towards 1945 new ones were fitted, abme to stop a plane at 75 knots on two-thirds throttle. It was reported she could stop a Seafire III every 43 seconds.

There were two lifts on the centreline: The forward one, alongside the catapult, was the largest, measuring 45 by 33 feet (13.7 by 10.1 m) and connected only to the upper hangar. The much smaller aft lift was 45 by 22 feet (13.7 by 6.7 m) served both.

The upper hangar measured 458 feet (139.6 m) in lenght, the lower one 208 feet (63.4 m), bith 62 feet (18.9 m) in wieght and with a height of just 14 feet. As a result, Lend-Lease Corsair fighter-bomber could not fit, neither cold war helicopters and more jets. The total capacity was 48 aircraft, still very short of what an Essex-class carried. Only through a better organization, the use of a permanent deck park allowed to reach the critical size of 81 aircraft, comparable to an average US fleet carriers, but protection was only ensured for half this. The lower hangar was indeed only half the lenght of the uppor one. Contrary to Ark Royal, not two full size, taller hangars; The forward part was left free for extra accomodations, mess decks, offices, store rooms. The flight deck also was 50 feet above the waterline, 12 feet more than HMS Illustrious.

Additional crewmen and maintenance personnel for the air group had to find a place in facilities never thought for such crew, and they were housed in the lower hangar by default. In all, in addition of an undisclosed tonnage of ammunitions below the second hangar, the ships carried four aviation gasoline (avgas) tanks, totalling 94,650 imperial gallons (430,300 l; 113,670 US gallons) enough for five sorties per aircraft. Buried deep inside the hull they were protected in theory by the layering above.

Air Group

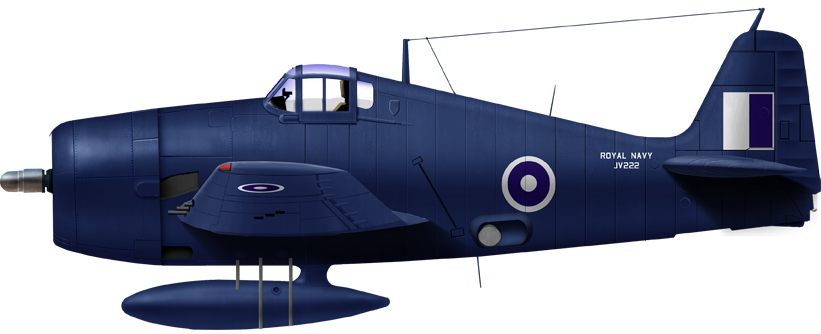

HMS Implacable’s air group in 1945, Seafires and Hellcats

Since the Indefatigable and Implacable were completed much later than the Illustrious class, and has a much larger capacity, the air group reflected this. At the time of their completion in 1944, the Fleet Air Arm ws immensily more powerful, counting not only on US designs such as the Grumman Martlet, but also more potent Sea Hurricanes and Seafire for her own defence, as well as late torpedo bombers such as the Fairey Barracuda, and the Fairey Firefly observation/fighter-bomber.

On June 1944 HMS Indefatigable had onboard a mixed air group countring 12 Seafire, 12 Firefly and 24 Barracuda. At the time, it was paramount to eliminate KMS Tirpitz and a fighting threat in Norway, and the aior group reflected this. In August, priorities changed and her her group was augmented, now comprising 24 Seafire (twice more), still 12 Firefly, but also 12 Hellcat and “only” 12 Barracuda for ship-to-ship attacks, although with their last equipments they could undertake ASW patrols as well. It seems also they carried two amphibian Sea Otter for recon & SAR (the successor of the Walrus). By the time they operated in the Indian Ocean, they combined 32 Seafire with 8 Hellcats modified for photo-reconnaissance. But 73 aicraft means they needed 479 maintenance crew, which lacked accomodations onboard.

Seafire crashlanding onboard HMS Indefatigable

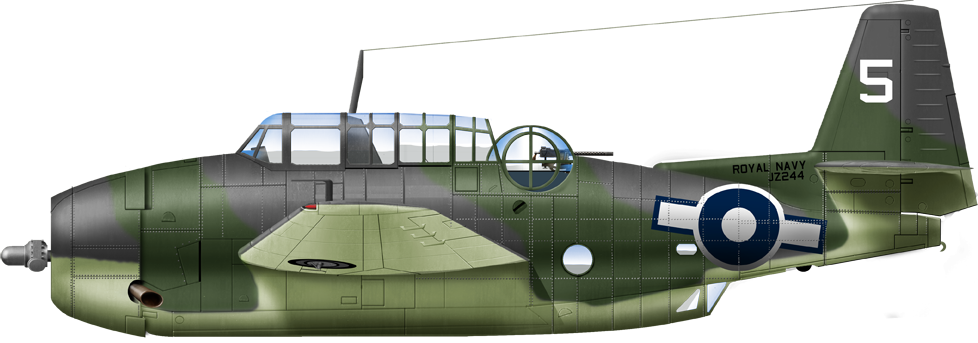

In early 1945, as both carriers were sent to the far east, their air group reflected a largely US equipment: In January, HMS Indefatigable had 6 Hellcat, 32 Seafire and 21 Avenger. The latter were configured to acrry bombs only, not torpedoes, as shown in photos. Indeed, they cold not carry the large British torpedo.

In March 1945, HMS Indefatigable even had an all-US air group, 29 Hellcat and 15 Avenger, used also for ASW patrol with depth charges. In the summer however, both carrier air group regained some British flavor: 48 or 40 Seafire, and 11-12 Firefly, plus always the same 21 Avenger on board. The Seafire were not used only for air supremacy against Kamikaze but also carried out strafing attacks along the Japanese coast and escorted the Firefly and Avenger all the way, while keeping a significant CAP behind to deal with Kamikaze raids, most often lone aircraft rater than the large okinawa strikes.

It’s by mid-1945 they reach their greater air group of 81 aircraft, the bulk being seafires, used for air cover but also strafing and bombing attacks when the need arose; The maintenance crew was now reaching 550, less the air crews, making the ships even more crowded, and this was aggravated somewhat by the choice of Bofors instead of Oerlikons, which needed even more manpower.

Hellcat Mk.II used for camera recce over Japan, Summer 1945. Sqn.888, HMS Indefatigable.

Avenger Mk.I from Sqn.820, HMS Indefatigable, late 1945. The original photo only shows the rear identifier, not the main id number, which is absent there.

In 1949, the last air group of Implacable as a training carrier was all-British, comprising 13 Sea Hornet and 12 Firebrand.

Blackburn Firebrand (here of Sqn. 813 in 1946)

Author’s old illustration of HMS Indefatigable, BPF, Japan, summer 1945.

HMS Indefatigable (1942) |

|

| Dimensions | 233.6m oa x 29.2 x 8.9 m (766 ft 6 in x 95 ft 9 in x 29 ft 4 in) |

| Displacement | 32,110 long tons (32,630 t) (Fully loaded) |

| Propulsion | 4 shafts geared steam turbines, 8 Admiralty 3-drum boilers, 140,000 hp |

| Speed | Maximum speed: 32.5 knots. |

| Range | 4,500 nmi/12 kts, 1,820 nmi (3,370 km; 2,090 mi)/25 kts |

| Armor | Waterline belt: 114 mm, Flight deck: 76 mm, Bulkhead, Hangar sides: 51, Magazines: 76–114 mm. |

| Armament | 8×2 QF 4.5-in DP, Five Oct. Quad. QF 2-pdr AA guns, 18-21 twin, 17-19 single Oerlikon 20 mm AA, 81 planes. |

| Crew | Crew: 2,300 with the air crew in 1945. |

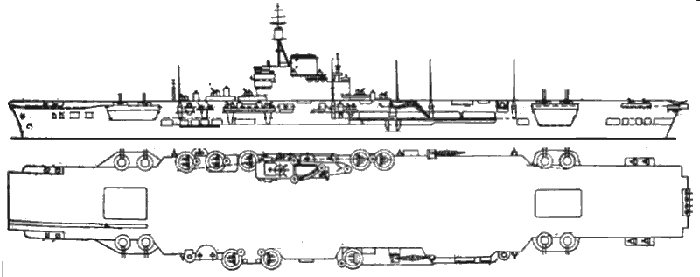

Planned cold war Modernization

HMS Implacable in 1947

Implacable and Indefatigable being relatively recent ships compared to the Illustrious class, they were scheduled for a full modernisation planned in 1953–55, after the model of HMS Victorious. The draft Staff Requirements were ready bu July 1951 and they concerned the following points:

-Combining the two hangars into one, 17-foot-6-inch (5.33 m) high to manage modern jets.

-Strengthening the flight deck and aircraft handling equipment for 30,000-pound (14,000 kg) models

-Enlarging both to the same to 55 x 32 feet (16.8 by 9.8 m)

-Adding a gallery deck between the hangar and the flight deck for more accomodations

-Addition of two modern, powerful steam catapults

-Radical increase of the aviation fuel stowage to 240,000 imperial gallons

-New boilers for better endurance

-Reinforced masts and accomodations for the latest radars

-Electrical power augmented with new modern units

-Replacement of her AA armament with 3″/70 Mark 26 guns and Bofors

By October 1951, estimated completion for Victorious well past its initial estimate, with cost rising. Implacable was scheduled to start initially by April 1953, for completion in 1956. However the Director of Dockyards stated that was just ludicrous and only a start in April 1955 was realistic, unless postponing cancelling modernisations of two cruisers and the guided missile test ship RFA Girdle Ness.

The Controller of the Navy asked to reduced if possible time and cost but even the minimum modificationss required to be worthwhile were the most expensive. Eventually the Navy Controller ordered the Director of Dockyards to reschedule the modernization of Implacable between June 1953 and December 1956, limuted to a three-quarters of the structural work. Shortage of skilled workers showed for Victorious was also acute and delayed the operations.

HMS Implacable underway in 1946

To further reduced the structural work, the replacement of boilers was dropped, and existing radars would be fitted, less demanding. In January 1952, the modernized armament was limited to six twin-gun 3″/70, three sextuple Bofors mounts. But even this plan was not realized as eventually, the Admiralty decided that Victorious would be the last fleet carrier modernised. The whole modernization process was too much for the crippled postwar British economic conditions and choices needed to be made for several programmes.

Final assessment of the class

British CVs of the British Pacific Fleet at anchor in 1945

Thus, the more recent, and arguably better suited Implacables were not modernized, unlike the much earlier Victorious. Both fleet carriers as a result would have barerly more than ten years of active service. On armouredcarriers.com, both are seen as “Armoured flight deck carrier design in disarray”. It is started that’s the war shortages of armour that resulted in the weaker protection of both carriers, and choice of larger groups for these last two vessels, still on the blocks.

However the website’s article title, “incomprehensible” is about the final design choice made for the hangars, to combat top weight, rather than trying to eliminate it elsewhere. Ideally, both carriers would have been given both hangars 16ft high in order to accomodate new models. As it appeared they just could not accomodate US planes, the corsair, Avenger and Corsair; At 14 ft, only the nimbler Firefly and Seafires could fit in. In appear that one motivation to reach that decision was that it was assumed all future British naval plane designs would incorporate the lower rearward folding wing system, which would prove incorrect.

Seafire Mark III inside the upper hangar. There is little room to spare, even for the nimble fighters. src: armouredcarriers.com

Whatever the case, the choice of having these two low hangar was what ultimately doomed both carrier’s usefulness and lifespan, explaining their short service. When in active missions, the lower half-hangar was in the end devoid of planes, other than those taken care of by the Air Engineering Department, using its all area as workshop space. Only the upper one was used for active parking. As a result, for full strikes they carried and in between, they carried the 3/4 of their active park on deck. Most often CAP fighers were those kept in the hangar. This was only possible in the Pacific. Given the pos-war economics, the conversion with a single, taller hangar could not be performed, and thus, both carriers were condemned to an early retirement. They could even not be used as helicopter carriers, since they could not fit inside either.

What redeemed both carriers however was the excellence of their fire protection systems, probably more than their passive armor protection, which was inferior to the Illustrious’s. They combined, like the prvious vessels, an unprecedented level of fire hazard safety due to the combination of generous ventilation systems (to avoid building up avgas emanations in their closed hangars), drains to carry excess water from the sprinklers, side fire hoses to avoid capsize, three asbestos fire curtains dividing the upper hangar, and emergency salt-water hangar spray system as a backup.

Having an extra set of shaft and turbine, more boilers improved speed, but also represented more stokers and engineers which needed extra accommodation, the Implacable just dies not possess. They would have to be skeezed wherever possible. Having the engineering teams and mechanics directly sleeping in the hangar, where sound would resonate loudly, were a recipe for bad sleep and thus, less efficient personal. Overall, the ships were seen as too cramped and in general, quite impopular with the crews.

Combating top weight by thinning the armour protection down to a mere “splinter protection” (D.K. Brown: The Design and Construction of British Warships 1939-1945, Major Surface Ships), was also not perhaps the best course of action; If the places had been reversed, and either Implacable or Indefatigable were in the place of HMS Illustrious on January 10, 1940, when she was hit by eight bombs from 550lb to 2200lb, it is possible, if not likely they would have been written off, not surviving this ultimate test.

It was estimated in 1944 that the new bomb models with AP caps, dropped from greater speed at lower altitude would pierce through the 1.5in side plating quite with ease for a 500lb bomb and raising it to 2 in was what ultimately lowered the hangar and doomed the general utility of the ships, but nevertheless, the general arrangement was considered a bit more effective compared to the Illustrious class, even though being 1,300 tons lighter.

In the Atlantic, where they were initially designed to operate, their doctrine was to carry all planes inside the hangar, stowed below and not on the flight deck, underlined by the design choice of having the strength deck at the flight deck, so being entirely watertight. Their efficient enclosed ‘hurricane bow’, tailored for the rough north sea gale, proved very useful in the Pacific, and HMS Indefatigable’s captain cheeky response to Admiral Halsey’s query about her status: “What typhoon?”, compared to the extensive damage on Wasp and Randolph.

Uktimately it’s the battle test which was the great equalizer. In that matter, it’s difficult to assess their real effectiveneness. In daily operations, they performed well enough, having an air group close of than of an Essex-class. They fitted in well, and the USN estimated their protected far better than their own fleet carriers anyway. Their ultimate showdown was at Okinawa. There, there was no shortage of Kamikaze attacks to show their usefulness, and indeed, their armored deck did the job: They “splashed” many Kamikaze on it. The strenght deck proved its worth, time and again, but design-wise it was too costly to create, raising a top-weight that had to generate sacrifices elsewhere. Only Indefatigable saw burning aviation fuel from the flight deck leaking through a popped rivet of hole in the armour, and contained by damage control. None of the two was ever hit hard as their earlier sisters.

HMS Eagle, of the Audacious class, completed postwar, the last British fleet armoured carriers.

Overall, comparing the Implacable and Essex would be unfair, like comparing apples and oranges. The first were still treaty CVs, in between the Yorktown and Essex, while the latter were post-treaty “free for all” designs. It would be fairer to compare the latter to the next generation, Audacious class, never completed during wartime. They were still “armoured carriers”, albeit less intensively than the Implacable and designed to carry at least 60 planes inside hangars. There, engineers decided to get rid of the “box” concept with a strenght deck. It was eliminated entirely. They were wartime designs rated at 36,800 tons (as built), so with far more generous accomodations. They became eventually the “perfect armoured carriers”, but were too late in coming due to the highly stressed level of British naval construction at that time. The USN and their greater resources would ultimately catch up in 1945 with the Midway class, and repeated on the postwar Forrestal’s flight deck design. With the almost complete loss of USS Bunker Hill and USS Franklin, they learned their lessons, albeit too late.

Scr/Read More

Links:

On armouredcarriers.com

On navypedia

On battleships-cruisers.co.uk

On uboat.net

On worldnavalships.com

Full logs on naval-history.net

About the 820 Sqn.

On portsmouth.co.uk

wiki

Books:

Gardiner, Robert; Chesneau, Roger, eds. Conway’s all the world’s fighting ships 1921-47

Brown, David (1977). WWII Fact Files: Aircraft Carriers. New York: Arco Publishing

Campbell, John (1985). Naval Weapons of World War II. Annapolis

Chesneau, Roger (1995). Aircraft Carriers of the World, 1914 to the Present: An Illustrated Encyclopedia

Friedman, Norman (1988). British Carrier Aviation: The Evolution of the Ships and Their Aircraft.

Hobbs, David (2013). British Aircraft Carriers: Design, Development and Service Histories. Seaforth Publishing

Howe, Stuart (1992). De Havilland Mosquito: An Illustrated History. Aston Publications

McCart, Neil (2000). The Illustrious & Implacable Classes of Aircraft Carrier 1940–1969. Fan Publications

Roberts, John (2000). British Warships of the Second World War.

Rohwer, Jürgen (2005). Chronology of the War at Sea 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two (Third Rev ed.).

The Illustrious and Implacable Classes of Aircraft Carrier 1940-1969, McCart, N

Model Kits:

The rare 1/700 model by Neptune (N°1111)

It seems only her air group had coverage, but not the ships themselves. Contrary to the cold war victorious, or the Illustrious class in wartime, Airfix ignored them.

3D rendition of the Implacable in WoW

HMS Implacable

HMS Implacable

HMS Implacable off Greenock, just completed

HMS Implacable was laid down at airfield Shipbuilding and Engineering Co., Clydeside, on 21 February 1939 (Yard Number 672) and with WW2 breaking out, her construction suspended from 1940 until later in 41. The Battle of the Atlantic was the utmost priority. Work resumed at last in late 1941 and gradually stepped up until she was launched on 10 December 1942, in presence of Queen Elizabeth.

Captain Lachlan Mackintosh was her first commander, supervising her completion in November 1943. Commission came on 22 May 1944, followed by sea trial, revealing many issues. After rectification she had a formal completion on 28 August and went to the Home Fleet, training intensively until her first air group, 1771 Squadron (Fairey Firefliy) arrived on 10 September, followed by the Fairey Barracuda of 828 and 841 Squadrons (No. 2 Naval Torpedo-Bomber Reconnaissance Wing).

Implacable off Greenock in June, with her 1944 camouflage

Implacable’s Norwegian Campaign

Her first mission at last, was to locate precisely KMS Tirpitz which left Kaafjord by early October and for this she departed Scapa Flow on 16 October, launching her Fireflies upon arrival. After two days of sorties, they eventually spotted the German Battleship off Håkøya Island, near Tromsø. She was prevented to launch an attack knowning the Luftwaffe had bases nearby, and the air group lacked escort fighters. On her way home, she spotted and damaged a German cargo. On 16 October, Seafires of 887 and 894 Squadrons (No. 24 Naval Fighter Wing) arrived, enabling future atacks.

Implacable at an unknown date, in grey livery, probably just completed.

In late October, she took part in Operation Athletic, rampaging the Norwegian coast. Her air group claimed six ships and an U-Boat, loosing one Barracuda. They made in fact the very last wartime torpedo attack of the Royal Navy. On 1 November 1944, Captain Charles Hughes-Hallett took command, and Implacable’s Barracudas were replaced by Seafires, from No. 30 Naval Fighter Wing (801 and 880 Sqn) from 8 November, which covered minelaying operations by escort carriers until 21 November, to prevent German sorties.

Implacable in late 1944

On the 12th, Admiral Sir Henry Ruthven Moore (C-in-C, Home Fleet) made Implacable his flagship to conduct a general hunt of a German convoy reported off Alsten Island, which became Operation Provident. Implacable launched its Seafires and Fireflies but bad weather precluded more sorties until 27 November. The convoy was nevertheless eventually spotted, and two cargos were sank, six others badly damaged. Among the ships sank, MS Rigel was a POW transport, unkbeknowst by the RN, and this caused the death of 2,500 total, allied many POWs among these.

The air group warming up for a sortie

Back to Scapa on 29 November, she became flagship for Vice Admiral Sir Frederick Dalrymple-Hamilton, second in command, for Operation Urbane, a minelaying operation. Fireflies spotted and helped sinking a German minesweeper durn this 8 December Operation. She was back to Scapa on 9 December, and on 15 December moved to Rosyth for a refit, preparations were made to be assigned to the British Pacific Fleet, notably by modifying and augmenting her light AA armament.

Implacable’s Pacific Campaign

Implacable in 1945

The overhaul was completed on 10 March 1945. She was assigned the 801, 828, 880, and 1771 Squadrons (48 Seafires, 21 Avenger, 12 Fireflies, for 81 total). This was the largest air group aboard any British carrier ever, even postwar. HMS Implacable departed on the 16th, went through the Suez Canal, Port Said (25 March) but durjng the crossing she was nearly beached by a strong gust of wind. It toiook hours for her escorting tugboats to pull her off, but she was undamaged and proceeded to Sydney, arriving on 8 May 1945, where the crew learned the war has ended in Europe.

She joined the BPF’s main operating base at Manus Island (Admiralty Islands) on 29 May and in early June, became flagship, Rear Admiral Sir Patrick Brind, for Operation Inmate. This was a large scale, final attack on Truk, Carolines. The operation started on 14 June and in all, the carrier made 113 offensive sorties in two days, loosing one Seafire only, before proceeding back to Manus Island, reached on 17 June to resupply. On 30 June, No.8 Carrier Air Group was formed onboard: No.24 Naval Fighter Wing was part of it. They trained intensively for future operations.

Implacable’s Avengers off Japan, 10 July 1945, part of her “permanent deck park”.

The BPF was sent off the Japanese coast from 6 July and she arrived on the 16th. She launched 8 Fireflies, 12 Seafires which raided designated targets around Tokyo the following day, although bad weather marred their efforts. The next day they were more successful, and located most of their targets. Bad weather again prevented sorties on 24–25 July. Afterwards, her air group attacked Osaka and roamed the Inland Sea. The escort carrier Kaiyo was notably found and badly damaged.

After a replenishement run, since both avgas and ammo ran dry, she resumed airstrikes on 28-30 July, locating and sinking the IJN transport Okinawa, near Maizuru, a masjor arsenal. Bad weather and fequent refuelling had more missions delayed until the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. It’s only by 9 August that she resumed air operations, and her Seafires flew 94 sorties. Northern Honshu and southern Hokkaido were rampaged, for the loss of two Seafires. The 10th, they sank two warships and many small merchantmen, destroyed railroad locomotives, parked aircraft and other opportunity objectives. The BPF however was scheduled to be withdrawn on the 11th to prepare for Operation Olympic, the November invasion of Kyushu, and she was en route for Manus on 12 August, learning of the 15th about the surrender. Her air group by then had made more than 1,000 sorties.

HMS Implacable in the cold war

Implacable and Formidable back to Sydney

As the operation was cancelled, she was sent to Sydney on 24 August for a refit. Her hangars received accomodation to pick up and repatriate Allied PoWs and soldiers. Her air group was left in Australia. She arrived at Manila on 25 September, loading over 2,000 allied PoWs of three nationalities, including Canadians. The Americans left at Pearl Harbor (5 October) and she reached Vancouver on the 11th. She stayed there for several days, opened to the public.

After a week, and replenishment, she left for Hong Kong and another PoWs rpatriation run, stopping afterwards at Manila, loading 2,114 more passengers, which left at Balikpapan in Borneo a for a transhipment to Britain while she carried instead 2,126 men of the 7th Australian Division back home, Sydney, on 17 November. On 8 December 1945 she went to Papua New Guinea to pickup more troops back to Sydney, staying there for Christmas. Just before the crew removed all accomodations to be ready to normal operational status.

In January 1946 she had her air group back (not 880 Sqn, disbanded) and the 1790 Sqn. After intensive exercises, she visited Melbourne, reunited with her sister ship, HMS Indefatigable. Flagship, Vice Admiral Sir Philip Vian, new BPF commander from 31 January she went on her training and goodwill tour of Austrlia before an overhaul on 15 March in Sydney, until 29 April. She dumped overboard her otherwide worn out 16 Lend-Lease Avengers (828 Sqn) and afterwards sailed for home at last, on 5 May. She arrived at Devonport on 3 June.

The admiralty soon assigned her as a deck-landing training carrier, and she started exercises in August 1946. On 25 September, she had a new commander, Aubrey Mansergh, and for two months she trained intensively with the Home Fleet. She received light damage on 7 November after a collision HMS Vengeance, while docking in Devonport.

On 1 February 1947, she joined the freshly completed battleship HMS Vanguard used as royal yacht for King George VI, touring South Africa. The carrier also hosted the king and his family on 7 February, granting them with an air show while the queen addressed the crew. She stopped at Freetown in Sierra Leone and Dakar in Senegal before proceeding to the Western Mediterranean, Girbraltar, and back home on 7 March for a long refit at Rosyth.

Implacable during a parade, however her flight deck

It started on 17 April and was completed in October 1947. On board her reduced air group comprised the new 813 Squadron (Blackburn Firebrand) and went on training until John Stevens took command on 9 February 1948, spending the summer in demonstrations for students of the Royal Navy’s staff college. She became the first British carrier operating the Gloster Meteor (Lt. Commander Eric Brown was the first to land). Other models landing were the Westland Wyvern and Short Sturgeon and intensive training which ended with a mock attack by motor torpedo boats.

A 10-week refit followed on 10 November, nd more deck-landings until the was assigned to Gibraltar on 27 February 1949, with 801 Sqn onboard (from 5 March, and its Havilland Sea Hornets). As flagship, Admiral Sir Rhoderick McGrigor, the following day, she trained with the Home Fleet. And went to the Atlantic and North sea, visiting Oslo and Bergen in June 1949, also visited by King Haakon VII. Back in Portsmouth she hoted King Abdullah I of Jordan and later Prime Minister Clement Attlee. 702 Sqn arrived (De Havilland Sea Vampire) in September 1949 for evaluations, until 11 November.

HMS Implacable in 1946

February-March 1950 were spent training in the Western Mediterranean under command of Captain H. W. Briggs. She departed later for the Irish Sea and off Scotland, visting later Copenhagen durig the summer, hosting King Frederick IX of Denmark. She was Admiral Vian’s flagship until the latter transferred his flag to HMS Vanguard, on 11 September 1949. Back home, she was placed in reserve.

The admiralty planned to convert her as a training ship, with extra accommodations and classrooms, but was denied the major reconstruction that could have let her operate modern aircraft because of budget constraints. Indeed, a similar reconstruction on HMS Victorious proved to be far more expensive and lenght than planned. By June 1952, the reconstruction was cancelled and she was recommissioned on 16 January 1952 as flagship, Home Fleet Training Squadron.

On 13 February 1952, she became Dover’s guard ship, attending the state funeral of King George VI. She departed afterwards fo the western Mediterranean and exercises in June, with a scenario of a fast troop convoy attacked by aviation. On her way back home she visited Copenhagen in july. She was back to Gibraltar on 25 September, visiting Lisbon, and was back to Devonport for her last, short refit. On 16 November, during this refit, an accidental oil fire in her galley destroyed her electrical wiring, prologating her refit until 20 January 1953.

February and March were spent again in the western Mediterranean with Indefatigable, for more exercises before, followed by a short overhaul in Southampton and participation to the Coronation Fleet Review of Queen Elizabeth II, on 15 June, as flagship, Vice Admiral John Stevens, Home Fleet Training Squadron, later relieved by Rear Admiral H. L. F. Adams. She trained off the Scilly Isles, Bristol Channel, ferried the 1st Battalion, Argyll & Sutherland to Trinidad due to the crisis in British Guiana and Royal Welch Fusiliers to Jamaica in October 1952, back home on 11 November.

Not much happened in 1953 and on 19 August 1954, she was relieved as flagship by HMS Theseus. HMS Implacable was decommissioned on 1 September 1954, slde for BU to Thos. W. Ward, 27 October 1955, in Gareloch and scrapped at Inverkeithing.

HMS Indefatigable

HMS Indefatigable

Prow view in 1944 as completed

HMS Indefatigable was laid down by John Brown & Co., Clydebank, on 3 November 1939 (Yard Number 565), and launched on 8 December 1942, much delayed after suspension. She was christened by Victoria of Hesse, the Dowager Marchioness of Milford Haven and Captain Quintin Graham was first in command, supervising the long completion of the ship. This went on in August 1943 but by ruse (Operation Bijou) from the London Controlling Section, she was allegedely already in service, which apparently worked on the Japanese, the disinformation going on for more than a year that she was already in the the Far East and bac to the Clyde for a refit.

Official commissioned came on 8 December 1943 and sea trials started, but similar problems were found as on her sister ship, so multiple fixes delayed her actual completion until 3 May 1944. A de Havilland Mosquito landed on 25 March (Lieutenant Eric Brown) for evaluation. Indefatigable was assigned to the Home Fleet spending several months in air crew training with the newly arrived Fairey Fireflies of 1770 Squadron (from 18 May) and Fairey Barracuda from 826 Squadron, in June 1944.

Indefatigable’s Norwegian Campaign

HMS Indefatigable underway in 1944

HMS Indefatigable made a first operational sortie on 1 July 1944, to provide air cover for the ocean liner RMS Queen Elizabeth, carryung US troops to Britain and when back, she was catch up by her fighter squadron 887, (Supermarine Seafire) and 820 Sqn with Fairey Barracudas, combined into the No. 9 Naval Torpedo-Bomber Reconnaissance Wing. She was deplyed against the battleship Tirpitz in Kaafjord: On 17 July she launched her air group wth others in a first attack called Operation Mascot. Her 23 Barracudas, and 12 Fireflies operated differently tactically-wise: The first attacked the battleship directly, the second strafed flak positions. But that day the German setup a thick smoke screen which foiled the approach of the Barracudas, and they launched, failed to hit, one forced to ditch on return.

894 Sqn (Seafires) arrived on 24 July, making a two Sqn-strong fighter wing, No. 24, with 887 Sqn. She then targeted many objectives in Norway from 10 August 1944, her fighters claiming 6 Messerschmitt Bf 110 fighters, also sinking a minesweeper. For Operation Goodwood, the next serie of air raids on Tirpitz, Indefatugable had a small squadron on Grumman F6F Hellcat (1840 Sqn), replacing Barracudas (826 Sqn) and on 22 August at dawn, she launched the remaining squadron of 12 Barracudas, 11 Fireflies preceded by the 8 Hellcats, plus 8 Seafiress. Again that day, the Battleship covered herself with a vary large smoke screen. FLAK was fierce and two Seafires were lost in action, while the rest mostly missed. The first raid was, again, a waste of time.

An ASW patrol Fairey Barracuda strapped in place aft of the deck, standing ready. Note the bracings and depth charges underwings.

Later another raid took place, with the very same events happening, and with the same results. But this time, Indefatigable lost none. Another was planned, but postponed due to bad weather until the 24 August. That day, she launched 12 Barracudas, 11 Fireflies, 4 Seafires, which at least contributed to some light damage by two hits on the Geran battleship: A 500-pound (230 kg) bomb and a 1,600-pound (730 kg) AP bomb, which penetrated the armoured deck, but failed to explode inside. Although all planes came home, this was another failed attempt and th admiralty grew impatient, as Churchill. The final attack was made on the 29th, and again for nothing. Fortunately none plane was lost, while 887 Squadron’s Seafired strafed the area and sank seven seaplanes moored at Banak during this raid. They had free hand due to the absence of the Luftwaffe. On 19 September 1944, HMS Indefatigable departed Scapa Flow for a rampage near Tromsø, but the whole operation was cancelled, again due to bad weather.

Indefatigable’s Indian Ocean operations

Indefatigable Underway 7 November 1944 in the Indian Ocean

It was decided to have the aicraft carrier refit for a short time (28 September-8 November) in order to operate on the east asian front. Whenn out, she became flagship of the 1st Aircraft Carrier Squadron (Rear Admiral Sir Philip Vian) from 15 November 1944. She was visited the next day by King George VI. Later maintenance crews for the 820, 887, 894 and 1770 Squadrons came on board, with new accomodations built for them. The air group its largest extent yet, with 40 Seafires, 12 Fireflies, 21 Avenger (armed only with bombs and DCs), before departing on 19 November, asined to the British Pacific Fleet. In fact she departed alone, much earlier than her sister ship Implacable, which had a much longer and intensive refit at the time. She transited via Colombo (Ceylon) on 10 December while Vian transferred his flag to HMS Indomitable.

Alongside Victorious and Indomitable, she made the bulk of the BPF air force. First with Operation Lentil (4 January 1945) she attacked a Japanese-held oil refinery at Pangkalan Brandan (Sumatra). She received six photoreconnaissance Hellcats (888 Squadron). She launched on the target Fireflies of 1770 Squadron armed with RP-3 rockets, which also claimed to have shot down a Nakajima Ki-43 “Oscar” (quite an agile fighter by the way), loosing one firefly, ditching out of fuel close to the carrier. When back on 11 January, whe was visited by Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten in charge if the South East Asia Command. She sailed to Sydney in preparation for Pacific operations, which included intensive AA training and close cooporation drills with the USN. But underway, the BPF blasted the oil refineries near Palembang in Sumatra (24-29 January), called “Operation Meridian”.

It was decided that over the pacific long range operations, her Seafires were best kept for close defense, providing the fleet combat air patrols and dealing with incoming Kamikaze. So the carrier only contributed with ten Avengers and two Firefly squadrons alone. The first attack saw almost all oil storage tanks destroyed, the refinery also wrecked for three months. Five days later, part of the same operation, the BPF raided another refinery with 820 and 1770 Squadrons. Two Fireflies made a reconnaissance mission over a nearby IJA airfield that was on course, for planning an attack, which wend as very successful but almost pyrrhic in nature, as losses were heavy (but unknown), while CAP Seafires claimed a Mitsubishi Ki-46 “Dinah” in reconnaissance and all five Kawasaki Ki-48 “Lily” bombers attacking from the same airfield.

Indefatigable’s Pacific operations

Fairey Firefly prepped to be launched

The BPF passed under the Sydney bridge on 10 February. Crews rested for a time, while she had maintenance. When it was over, the replenished ship departed with her fresh crew to the advance base at Manus Island with the rest of the BPF and RDV with the USN. Sh departed on 27 February and arrived on 7 March. More training followed, and she departed for Ulithi on 18 March 1945, to join the US Fifth Fleet on the 20th, taking part in the first phase of Operation Iceberg, the invasion of Okinawa.

The British were tasked to neutralise airfields on Sakishima Islands, between Okinawa and Formosa (Taiwan) from 26 March, with Seafires in CAP, Avengers and Fireflies all armed with bombs. The British fighter lacked 13 pilots and and only made 72 sorties that day and the following. The airfield was eventually destroyed and at the fall of March, she departed to refuel. When back in operation, HMS Indefatigable was targeted by a massive Kamikaze raid, which went through the CAP and her AA defense: She was hit, becoming the first British aircraft carrier damaged by a kamikaze, on 1 April.

As usual practice, the agressing fighter also carried a bomb, but fortunately it did not detonated, and most damage was stopped by the armored deck. But burning fuels and the detonation kill 21 and wounded 27 nevertheless, the most severe losses of her career so far. Her flight deck was back in operation in just 30 minutes, with the prompt reaction of the safety team, as well equipped and trained as were the USN’s.

On 12-13 April, the BPF started to target northern Formosa, also dotted with military airfields. The first day she had two Fireflies duelling with five Mitsubishi Ki-51 “Sonia” dive bombers, having four down; Like the Fulmar it replace, the verastile model proved just as good as a fighter when needed against less agile opponents. Meanwile, four CAP Seafires spotted and attacked four Japanese fighters (three A6M Zero, one Kawasaki Ki-61 “Tony”), shooting down one Zero.

Back to the Sakishima Islands on 17 April, there was another raid, before the fleet retired in Leyte Gulf, to rest and resupply. Many Seafires were lost to a variety of causes with 25 out of 40 out of commission. 5 replacements were received, but did not rebuilt the fighter strenght. They were criticized for their short range by Admiral Vian, which requested more lend-lease Hellcats and Corsairs if possible. When Operation Iceberg started properly on 25 May, the BPF had lost 61 Seafires in all, many just damaged beyond repair and worn out. They suffered much to deck-landing accidents. Back in action on 4 May, Indefatigable went on rampaging the Sakishima Islands.

The BPF was back in Sydney to rest and resupply, plus maintenance on 5 June and departed soon for Manus after three weeks, leaving Indefatigable behinf for machinery repairs. Her air group, which trained on land all this time, came back aboard on 7 July: New was the 1772 Sqn (Firefly) replacing, 1770 Sqn. On 20 July she was back with the BPF, started operations off the coast of Japan. First her air group raided Osaka and in various Inland Sea targets later. Her Seafire squadrons in between has been given external fuel tanks and were now able to bot be constraint to CAP only, but they started to escort the attacking squadrons over Japan.

Her air group constributed to the near-destruction of the escort carrier IJN Kaiyo, sank smaller ships on 24 July, on 28 and 30 July, but further operations were cancelled due to bad weather. Between this and refuelling runs, the bombing of Hiroshima had air operations resumed on 9 August. That day, her air group targeted airfields and other objectves over northern Honshu, and southern Hokkaido. The next day she sank (and constributed to sink) two warships and many merchantmen, also targeted the Japanse railroad system and and parked aircraft in various airfields.

The American carrier Randolph (right) and Indefatigable (left) off the Japanese coast, 30 August 1945.

The withdrawal of the whole BPF was planned after 10 August, back in Austrlia to prepare for Operation Olympic in Kyushu (November), and while the BPF departed for Manus on 12 August Indefatigable stayed behind, to support the Allied occupation force. On the 13th, she attack targets near Tokyo and on the morning of the 15th, her air group was prepared for the first airstrike on Kisarazu Air Field (four Fireflies, six Avengers, eight Seafires), when it was postpones due to bad weather.

Avenger Mark I crash-landing in 1945

Depring later that day when the weather improved, they were attacked en route by 12 Zeros: This was the last British air fight of the entire war. One Seafire was shot dow, as an Avenger, for four Zeros down, and four more probable, four more damaged, proving either the good performances of the Seafiire and pilot experience, but also the poor state of readiness of very young Japanese pilots at this point. An Avenger even claimed badly damaging Zero. A Yokosuka D4Y “Judy” went though the CAP and AA and targeted the carrier: It went well after the ceasefire was in effect, but fortunately, her missed. CAP were maintained until the end of the day and the next as all japanese did not received the message yet. More attacks will followed. In between, her air group started to search for POW camps and drop supplies when located.

Indefatigable’s cold war career (1945-1955)

Indefatigable at Charlotte Sound, New Zealand, November 1945

On 17 August, Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser (BPF C-in-C) visited Indefatigable, addressing the tired but happy crew. Flying operations went on and she was granted to visit Sagami Bay, Tokyo, on 5 September. At least her crew saw the main campaign objective. On the 8th, she departed for Manus, to resupply, and then sailed to Sydney, arriving on 18 September. Her refit lasted until 15 November while the crew was in prolongated leave. On 1 November 1945, Captain Ian MacIntyre took command and the carrier became Vian’s flagship again from the 22th. When ready she departed for a goodwill tour of New Zealand, arriving in Wellington on 27 November.

Opened to the public she was visited by Australian Prime Minister Peter Fraser. She was in Auckland on 12 December and finally back to Sydney (for Xmas rest) and Melbourne on 22 January 1946. She was prepared to head for home, nine days later as Vian transferred his flag to Implacable. She stopped in Fremantle and crossed the Indian Ocean the south to East Africa, reaching Cape Town, also opened to the public, and visited by the Governor-General of South Africa.

She arrived in Portsmouth Dockyard on 16 March 1946 for a long refit, intended to participate in the British version of Operation Magic Carpet: She had her hangar modified into accommodations for 1,900 passengers, including separated facilities for women. Departing for Australia on 25 April she had 782 RN personnel onboard, plus 130 Australian war brides. They mostly disembarked at Colombo, the war brides at Fremantle. In Sydney, she embarked a complete naval hospital, patients and personal, plus over 1,000 RN officers and ratings, departing on 9 June 1946 for Plymouth (7 July).

Next she carried men between Malta and Colombo. She arrived in the latter on 15 August, loading personal from all three service bound to UK. She arrived in Portsmouth on 9 September. Hr last voyage saw her carrying 1,200 RN personnel and civilians to Malta, Colombo, and Singapore. There she embarked 1,300 personnel bound to Portsmouth (29 November). She was refitted agains for a fourth and last voyage, sailing empty west for Norfolk, Virginia, and loading there RN personnel bound to Portsmouth, on 21 November.

Indefatigable in November 1945

Her last phase of her career started with a refit, as she was placed in reserve in December, her captain leaving on 7 January 1947. At first she was reconverted for military purposes and intended as a training carrier like her sister ship. The refit took place in mid-1949 and she was recommissioned under command of Captain Henry Fancourt, from 22 August. She depatrted for Devonport for her long refit strarting on 30 August. Captain John Grindle was appointed on 24 March 1950, second recommission being made on 28 May (later relieved by Captain Robert Sherbrooke) as she made her sea trials on 28 June 1950. Inspected by Rear Admiral St John Micklethwaithe in July she received her first trainees and participated in exercises with the Home Fleet, plus a cruise to Gibraltar in winter.

On 12 March 1951, she depated Portland, as Micklethwaite’s flagship for more fleet training, before a refit at Devonport, in May 1951. Captain John Grant took command on 6 June. She was open to visitors at the Festival of Britain, 17 July, but five of them were stranded aboard later when a storm hit, her captain ordering Indefatigable to put to sea to go for more moderate seas away. Rear Admiral Royer Dick made her his flagship in September, followed by a short refit in Devonport, in January 1952.

The two sister-ships were reunited for their annual cruiser to Gibraltar, from February 1952. Summer exercises were followed by a cruise and visit to the Danish port of Aarhus. There, she hosted Queen Alexandrine of Denmark. Later Captain Ralph Fisher took command (30 January 1953), for more exercises and usual cruise to Gibraltar, followed by a stop in Portland (March 1952) and Bournemouth (May 1952), joining the rest of the fleet on 9 June heading for Spithead and the Coronation Fleet Review on 15 June. There, the Queen admired the nine carriers of the Royal Navy in full regalia, two more than the force which went through WW2 (the four Illustrious and two Implacable) as wartime carriers in construction were just being completed.

Indefatigable also trained after the summer to the Scilly Isles and Bristol Channel in the fall, starting he small refit on 6 October. The Admiralty on 26 January 1954, announced that both ships were not suitable for a fll econstructon and no longer relevant in jet age as training carriers, so that they would be retired for good. First, Indefatigable was reduced to reserve, but still in full commission as she made her cruise to the Western Mediterranean in winter followed by more exercises with the Home Fleet, aslo stopping in Casablanca (Morocco) and back to Gibraltar.

Captain Hugh Browne took command of the aicraft carrier from 10 May and the ship was prepared for the visit of Queen Elizabeth II and her husband on the 14th, just returning from their Commonwealth tour on HMS Vanguard, escorted by her sister-ship. In June, Indefatigable trained in Scottish waters, visited Aarhus and in August started a lenghty transfer to HMS Ocean, retaking her role as training carrier. In Rosyth on 2 September, she was soon paid off, until October. She stayed there until June 1955, then to Gareloch to be listed for disposal. She was eventually sold for scrap in September 1956, broken up at Faslane.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign

Dear Sir or Madam.

I was a Boy Seamanwith others to HM Implacable , and at 16 years old ( after 9 months training from HMS Ganges boys training establishment, Suffolk.)

The ship was for training, and I was trained , among, other many things, on the engine room telegraphs from the wheelhouse and on the wooden wheel…

The ship went through Scapa Flow and visited Brest in France and Vigo in Spain. The history of the final days of this ship is therefore incomplete.

Yours sincerely

Raymond Lee .

Many Thanks for the updates on Implacable !