As Japan signed the treaty of London, the Imperial Navy was capped for heavy cruisers, and with extra limitations in tonnage. This led to the creation of four six “light” cruisers equiped with fifteen 6-in guns, later to be swapped for 8-in guns in wartime: The Mogami class (最上型) were the first four of this program. They took part in many engagements of the Pacific war but none survived the onslaught.

The 6-in shells avalanche

The Mogami class were designed at the time Japan’s political elite was still willing (and able) to comply with international treaties. The 1930 London treaty crucially forbade heavy cruiser construction (that is, with 8 inches (200 mm) main guns. Nothing prevented a country to create a heavy (10,000 tones) treaty cruiser that can be upgraded in case of war from the now allowed 6-inch, to a 8-inch again, after a simple turet swap and internal loading system and ammo revision, a few months work. That’s precisely the calculation made the admiralty staff, as a condition to accept the treaty.

They were planned amidst the choices of global tonnage restrictions, and instead of the improved Takao initually planned: Tonnage limit for light cruisers went close to set limit and only freed by scrapping the four old prewar Tone and Chikuma classes protected cruiser, but also the planned replacement of the Tenryu class and Kuma class in 1934-1937, which allowed Japan to build 6 new light cruisers: The Mogami and Tone classes. The furst became officially the Design C-37, a 8,500 tons design, which was only possible for the allocated six last peacetime cruisers of the IJN.

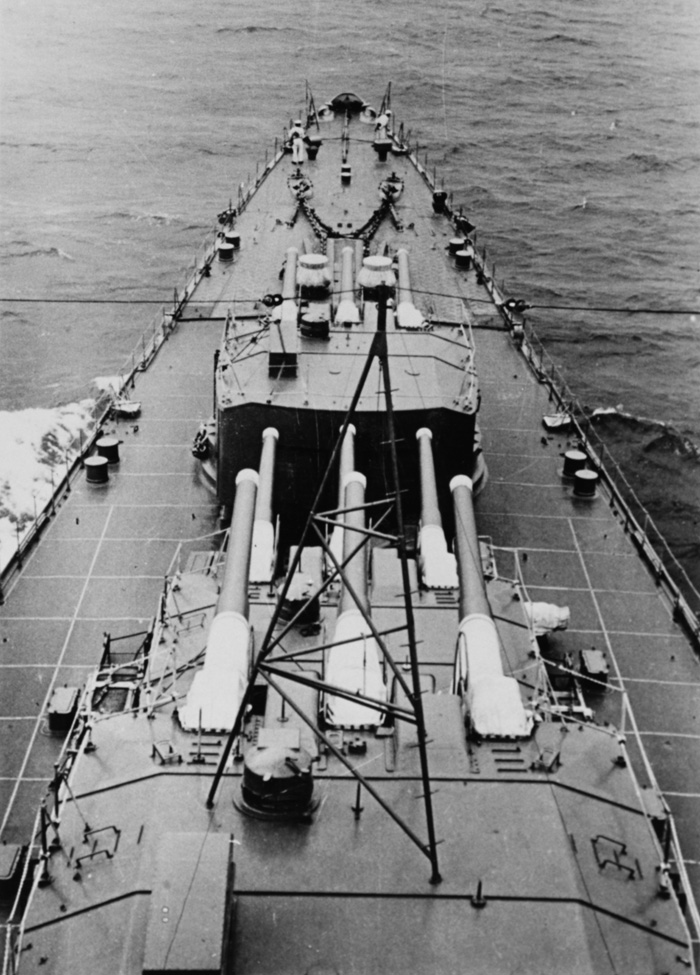

The immediate consequence of the London treaty being signed was found in the 1931 Fleet Replenishment Program. The IJN did not wanted to be thrown back to an Aoba/Furutka design and instead, simply wanted to build a cruiser to the maximum allowed by the Washington Naval Treaty/London treaty combined. While constrained by the choice of 155 mm (6.1 in) guns, they were to be crammed into five triple turrets, the choice of five turrets being a logical follow-up of the previous Takao class.

This made for a total of fifteen 6-in guns, a first for Japan. In addition, these main guns were also of a modernized type, faster-firing and with a new cradle and turret allowing 55° elevation, unheard of at the time. This made the Mogami design the first with a fully dual purpose main battery, coupled with and increasingly heavy anti-aircraft protection and of course quickly reloadable turreted torpedo launchers with the “long lance”. A deadly package that was soon recoignised in naval publications.

These were reclassified as light cruisers because of their initial standard displacement of 8,500 tons, reached 37 knots (and thus surclassing most cruisers of their time), but this also caused the same issues over again in IJN warship design: They vibrated a lot; and were lacking in rigidity and stability overall. But their fifteen 155 mm guns like the contemporary Brooklyn class could pour on any target 27,400 metres (30,000 yd) an avalanche of 75 rounds a minute, versus 20 to 30 for the heavy cruisers. Since the Japanese privileged tactical surprise over all else, this seemed an advantage. But the idea was always to replace them with the 20 cm/50 3rd Year Type naval gun, which was done during WW2 for all vessels. The latter had a rate of fire nearing four a minute, almost the same.

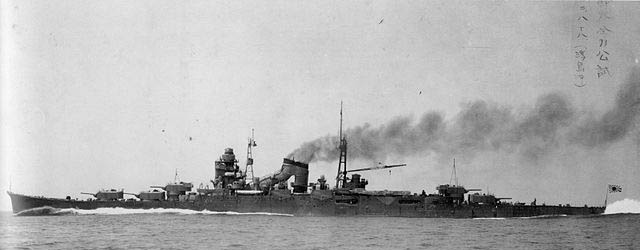

Mogami at Kure in 1935 trials

The quest for lightness, and its issues

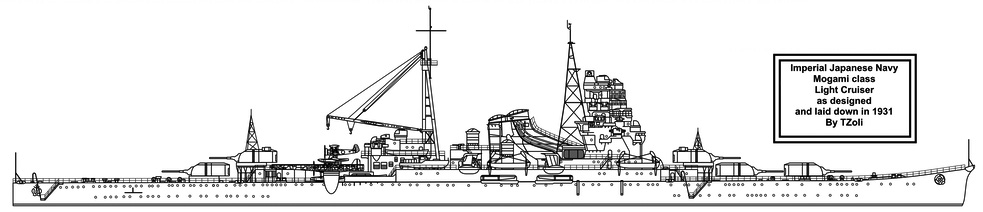

The initial C37 design showed a very different appearance, closer to the Takao class: The bridge was indeed still massive, and very similar to the Takao, adopted despite being known as top heavy with a large target surface, shot-trap issues, and wind resistance. It was counterbalance by the centralised fire-control, communications and navigational stations, and a fou-led lattice foremast. To save weight later (and thus have more cruisers for the allocated dispacement), and improve transverse stability, engineers found a way to create far more more compact and, smaller, lower superstructures, in aluminium at that. This is the main distinctive elements over previous classes, especially the Takao and their bloated steel bridges. Also during construction, electric welding was used, again to save weight. However soon cracks developed and appeared all over during sea trials, showing defects still in welding techniques, quite new at the time.

Still to meet the 8,000 tons weight limits discussed for the 1935 treaty, engineers fitted just ten boilers rather than twelve on the Takao/Myōkō classes with a new exhaust arrangement designed to minimize weight too. The middle funnel for example was just venting its exhaust gasses into the underside of the forward one, reclined from its base and merged with the aft one. This loss of power was compensated with brand new geared impulse turbines reaching 22,000 shaft horsepower (16,000 kW), allowing to meet a top speed superior by 1.5 knots (2.8 km/h; 1.7 mph).

Protection was kept the same, not impressive but well designed and using dispersion on multiple layers. The class was easily able to survive many hits. In the end, corrections were still necessary and these cruisers had a declared displacement (standard) of 8,500 tons (10,980 FL) but a real displacement of 9,500 tons. On trials they would even partially load, displaced 11,169 tons. The 1935 London treaty indeed only authorized light cruisers up to 8,000 tons standard. The Royal Navy was compelled to meet it with the Colony class design in 1938, but the result was quite different of course.

The engineer’s achievement was nothing short of exceptional, to cram as much armament on such a light displacement, while keeping high speed and average protection. But it was clear as the ships were completed in 1935, they showed excessive topweight, still. Instability had a price, with not the roll required for a goood firing platform, not counting the danger in case of heavy weather, or simply abrupt hard turn, and structural weakness shown by cracking hull welds, plus vibrations making their fragile telemetric and targeting systems quite inneficient.

As Japan eventually refused to go further and sign and withdrew from the conference on 15 January, also de fact ripping off all previous treaties although still bound by inspections and questions for foreign commissions. Freed from limitations, engineers had to fit hull bulges on Mogami and Mikuma, then added on Kumano and Suzuya while in completion, increasing their beam to 20.5 m (67 ft) for 11,200 tons dsiplaccement. The extra weight solved the issues, but this was paid by a two knots top speed sacrifice.

Design of the Mogami

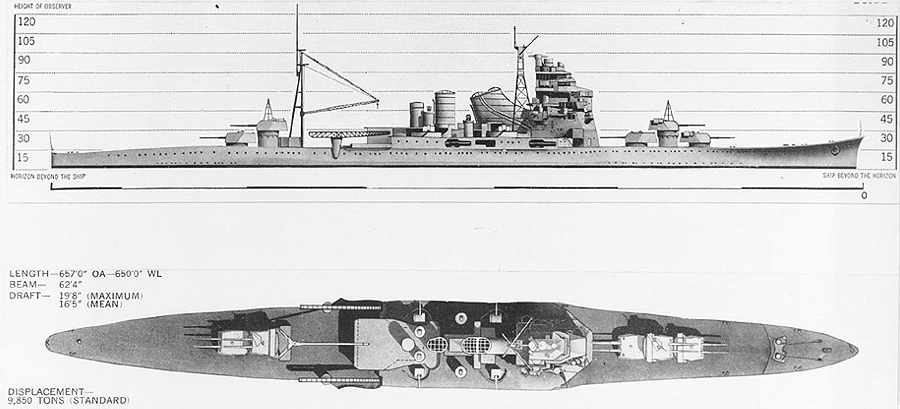

ONI depiction of the Atago (Takao) class

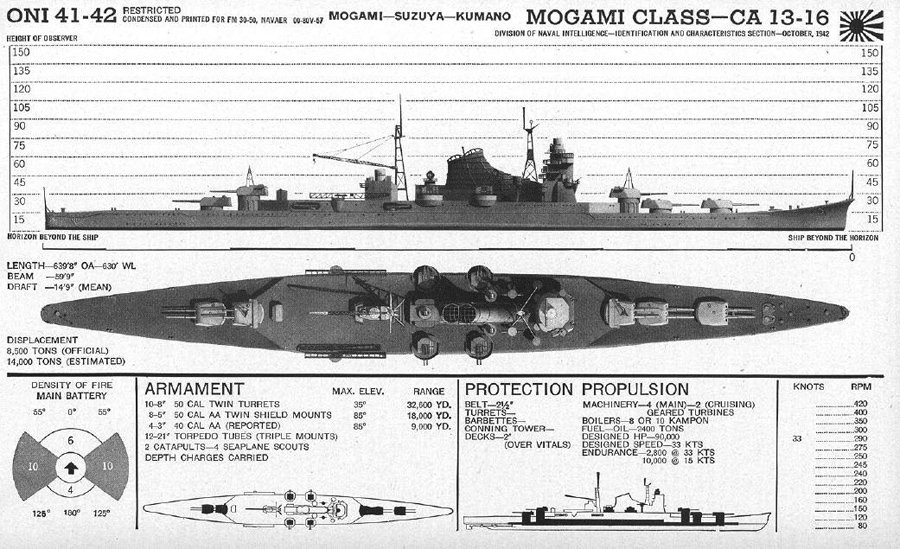

ONI depiction of the Mogami class, to compare. Differences are quite obvious.

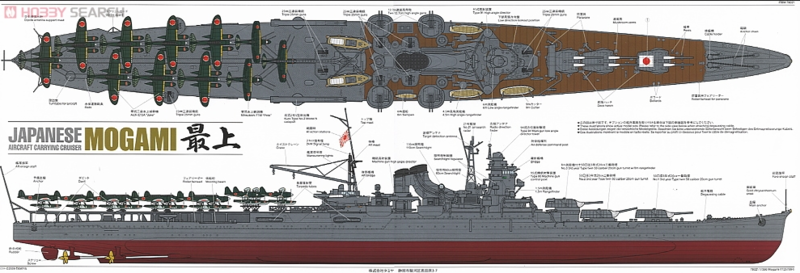

The general design of the magami, signed by superstar lead designer Yuzuru Hiraga followed the same basic hull shape defined for the Nachi class back in 1925. This was a typical “narrow-waste” hull shape, with the minimal waterline beam, favourable ratio of 1/10 for top speed, and two-stepped flesh duck hull on two levels, raised at the bow, and sloped down aft to the stern. The poop was however taller than on previous cruisers. Seen from above, the greatest beam was reach just forward of the mainmast, aft, whereas the Takao class had a straight section amidships.

-The first major difference with the Takao class was a larger battery superstructure, it extended past the side catapults, the “X” barbette.

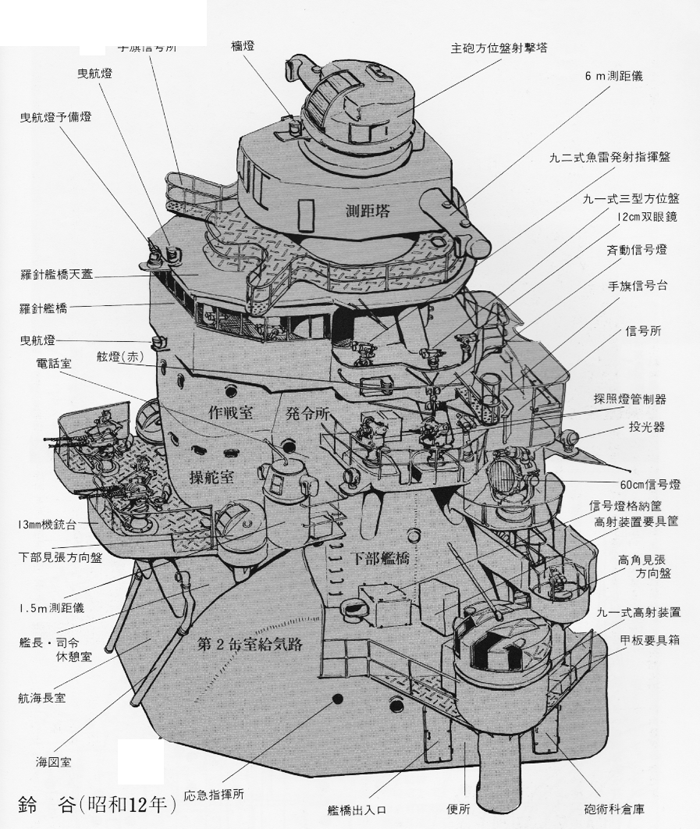

-The second difference was the much smaller bridge superstructure. Not only it was lower, but also had a single ain navigation bridge and not much around, supporting a massive telemeter. The tower was framed, as for Takao, by two rearwards facing air intakes, acting like side add-on armor. This made over the whole bridge much difficult to hit.

-The third difference were the all-truncated exhausts into a single raked funnel: The Takao had one truncated and one straight behind.

-The fourth difference was the implementation of A,B,C turrets forward, with three on deck level, one superfiring (C) at superstructure level, superfiring (On Takao ‘C’ was at deck level and facing rearwards, to the bridge).

The fifth major difference was the shape and location of the masts: The foremast was behind the bridge, atop the forward truncated exhausts, on four legs and with lattice, relatively short. The mainmast aft was located not close to turret ‘X’ as on Takao, but close to the funnel, at the level of the forward TT banks and in front of the aft bridge.

The sixth difference was the upper aviation deck, with enough space to park an extra seaplane and relocate it on either catapult, since there was no hangar.

Evolutions of the design

The initial design had a large bridge, but also for the first time to comply with the treaties, a battery Main of fifteen 155mm guns. They were “firsts” in many ways: For the caliber, first, as they reached the maximum caliber allocated by the Washington treaty, setup over the French own caliber, and later confirmed with the London treaty. There was no shortage of 6-in guns in Japan (152 mm), an already well-proved ordnance, but the admiralty wanted for this new class to go as far as possible within the treaty limits.

Thus, a new gun design was started alongside the Mogami class design (see later). Second, they were innovative also by their loading system, partial automation, and morover for their great elevation: They were designed to provide AA fire, notably using newly developed “secet weapons” like the AA “shotgun ground” specially designed for heavy guns in AA defense. The secondary armament was more conservative, trusted to the known 5-in caliber, but introducing the new type (12,7cm Type 89). Torpedo armament was the same as the Takaos, and did only changed for weight reasons later. These were reloadable quadruple tubes.

Changes however erupted at the time of the Mogami and Mikuma commission, trigerred by the famous Tomozoru incident, of 14th of March, 1934. Immediately it was supected stability issues on the Mogami class, leading to a programme called the “first efficiency or stability improvement works”. It was drafted in June 1934 to be applied on the first two units, already launched. The other were at the time, just laid down. It included the following list of modiifcations:

-Strengthening the transverse bulkheads;

-New, much smaller bridge cut by 2/3;

-Removal of the seaplane hangar;

-Complete refit of the aft superstructure, 50% lighter;

-Deck height reductions;

-Moving the torpedo tubes further aft;

-Increasing AA guns, with 4 twin 40 mm mounts;

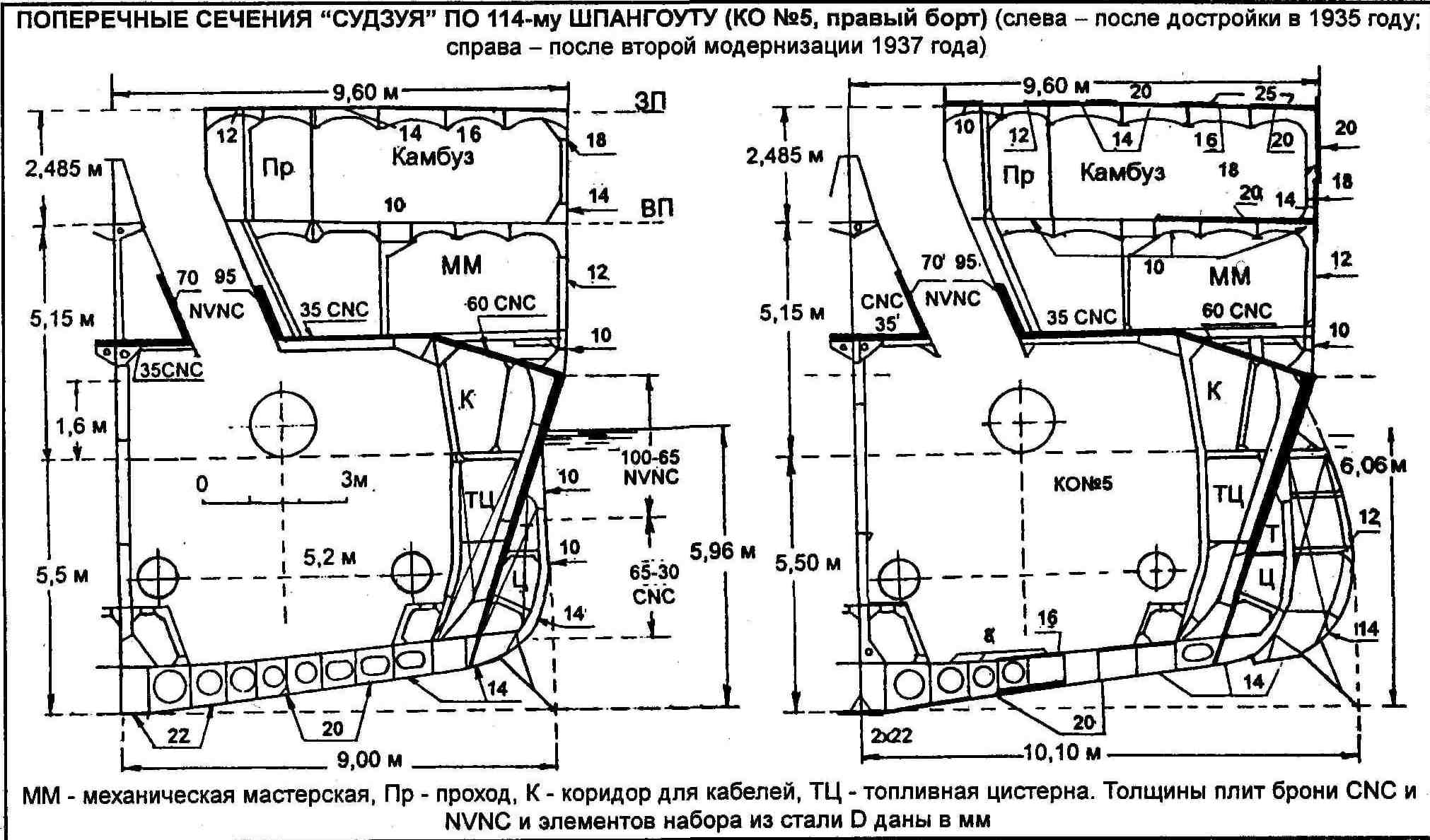

Protection scheme in detail

The construction of the hull and protection overall were in line with previous designs, notably Hiraga’s famous integrated structural armor and hull plating, which saved weight. Most of what was done for previous designs, the Takao and Nachi, was still valid. The belt armor or example was sloped inwards, like for previous cruisers, addin an artificial trhickness, or better deflection power to incoming shells. The problem was that after adding bulges, the latter became “short-traps” of some sorts for plunging shells; This was mitigated by the distance travelled underwater or 2-3 meters in calm weather. Ballistic studies showed the loss of velocity here.

Armour figures were about the same, just slightly decreased for the main belt (100 versus 102 mm or 3.9 in vs 4 in) in exchange for more protection over the magazines (140mm or 5.5 in versus 127 mm or 5 in), but there was an additional 5-in armor plating over them anyway. The design of the belt protection was also different from the Takao: The upper belt layer extended all the way to the “X” barbette, unlike for the Takao, where it stopped before the aft catapults, well short of the barbette. It was inclined in an inner angle of 20° over 110.5 m long (), connecting with anti-torpedo bulkhead at its lower edge. It was 6.5m high over a length of 78.2m on Mogami and Mikuma, and over 74.2m on Suzuya and Kumano.

Armor schematics detail, ONI

The citadel also extended about ten meters past the fore and aft outer barbettes (‘A’ and ‘Y’). On the Takao it stopped before ‘Y’, at the level of ‘X’ barbette aft, and extended just a few meters in front of ‘A’. It was 100mm (4 in) on its upper edge, tapering to 65 mm () on its lower edge to the citadel and main armor deck, connected with a 65 mm upper edge on the longitudinal bulkhead. Transverse bullheads were 105 mm thick, while the thickness decreased to 25mm near the double bottom.

The magazines were protected by narrower belts, 4.5m in height, connected to the longitudinal bulkhead and it upper edge was tapered down to just one inch, 0.1 m above the waterline. it was 30mm close to the double bottom. They had a flat 40mm lower deck. The steering gear compartment was protected by 4 in (100 mm) for its longitudinal part, enclosed by 35 mm transverse bulkheads, and completed by a 30 mm medium deck.

The Main battery turret had the same pathetic 25 mm or armor (0.98 in) to deal with shell fragments, as their barbettes. The armor deck was slightly decreased at 35 mm, versus 37 mm. They were assumed similar for the two upper decks of Takao, acting as energy-bleeding layers for incoming shells: 12.7, then 25 mm (0.5, 0.98 in), making a three-layered vertical defense. The later addition of bulges also added an extra longitudinal bulkhead, backed by a void, and extra fuel-filled upper longitudinal compartments behind the belt for extra ASW protection, over 3.3 meters deep (10.8 feets).

The machinery space were also divided into suparated spaces both for the turbines (four spaces), and boilers rooms (four, with two each). They had a 100 mm (4 in) conning tower with a 50 m roof (2 in). It should be noted that the smaller bridge make it harder to hit, its shape and configuration, with no shot-traps contrary to the Takao’s, and higher general quality of Japanese steel.

Comparison sections bulges and armour between the Mogami and Mikuma

- Belt: 100 mm (3.9 in)

- Belt over magazine: 140 mm (5.5 in)

- Main armored deck: 35 mm (1.4 in)

- Upper decks: 12.7 to 25 mm (0.5 – 0.98 in)

- Main bat. turrets: 25 mm (0.98 in)

- Magazines: 127 mm (5.0 in)

- Bulkheads: 105 mm (4 in)

Powerplant

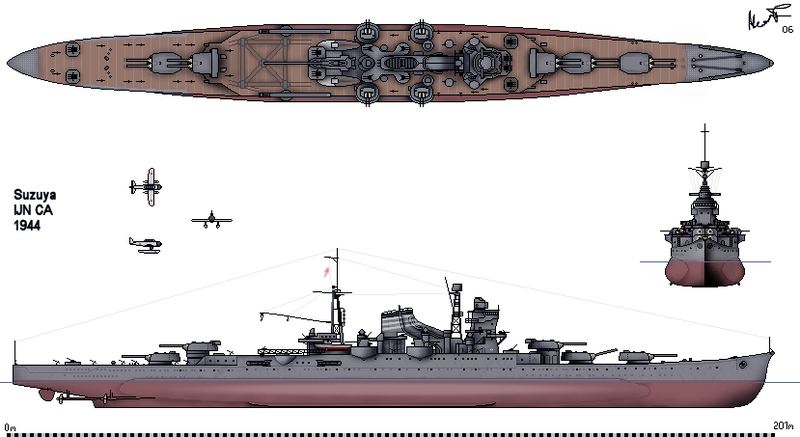

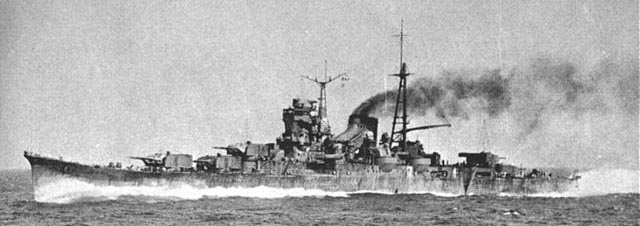

Suzuya on trials at Tateyama

This powerplant was basically the same as previous Takao class, it was innovative in that the new lighte Kampon Boilers were far more efficient and took less space: It comprised four propellers shafts driven by four geared steam turbines and fed by 10 Kampon boilers, instead of 12 on the takao. However it was soon modified to just eight to save weight, all truncated into a single funnel, unlike the Takao class. Moreover, with four less boilers, the ouptu was quite impressive: 152,000 shp (113,000 kW) versus 132,000 shp (98,000 kW) on the previous Takao.

Top speed as design was 37 knots (69 km/h; 43 mph), far better than the Takao and their 34.2–35.5 knots, but after prewar modifications, they took much weight and top speed decreased to 35 knots, which was still better than the modified Takao and Nachi, making them the fastest Japanese cruisers to date. They also had a good range, of 8,000 nmi (15,000 km; 9,200 mi) at 14 knots (26 km/h; 16 mph), but a bit less than the Takao’s 8,500 nm. All in all, this powerplant was considered so efficient it was adopted for the construction of the aircraft carriers Soryu and Hiryu, which in turn became the fastest aircraft carriers in the world.

Armament

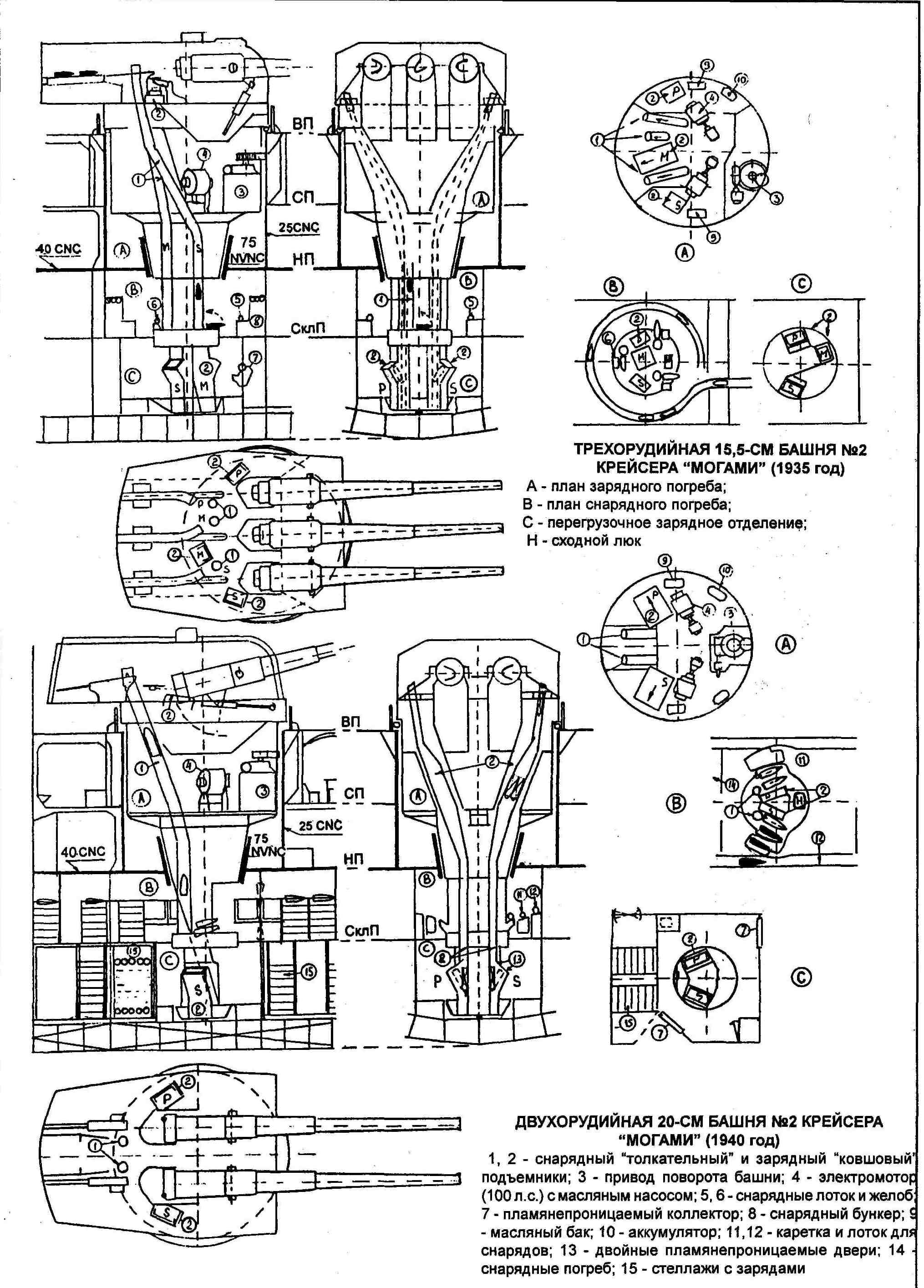

Main: 5×3 15.5 cm/60 3rd Year Type

As usual, when constrained to use a light cruiser caliber, forced by the London treaty they signed, the Japanese naval staff wanted to take the maximum allocated they could take that limit, which was not the usual 152 mm (6 inches) generally adopted by most fleets, including the Japanese, which derived theirs from WWI Vickers Guns and British practice, but went straight to the “exception” that was granted to the French and their Canon de 155 mm Modèle 1920 at the treaty of Washington, and confirmed by London. The reaoning of this authorization, necesary to obtain France’s adhesion was wronf however, as even this minute difference in caliber made quite a difference: The new Japanese 155 mm shells weighted 57 kgs, versus 45 kgs, which made quite a difference at impact.

The adoption of this new caliber did not either conducted to just relining the barrels and calling it a day. The 3rd Year Type was a completely new ordnance, from top to bottom. Not only of a larger caliber, but the barrel construction, monobloc type with autofretting, recoil mechanism, and Welin breech blocks were all new, as well as their mounting, which was also innovative: They allowed these new guns to elevate up to 45°, making them in effect AA guns as well, so dthe first dual-purpose heavy calibers of the IJN.

However these new guns also had limitations: Their Breech block would be operated either hydraulically or by hand, but overall the process of reloading was still slow, which combined to their still limited elevation, and slow traverse, made them totally unsuitable as AA guns. The idea was rather for them to fire an adaptation of the new “grapeshot shells” developed to blast large areas at long distance in opening on an incoming air attack (and proved not successful in wartime).

These guns developed at Kure arsenal from 1933, introduced in 1935 (80 were built), also equipping the next Tone class cruisers and Yamato class battelships, weighted overall 12.7 metric tons (28,000 lb), with a total of 9.615 metres (31.55 ft) and 9.3 metres (31 ft) barrel. They could also depressed down to -7°, allowing the to fire with close incoming, low freeboard targets, had a top rate of fire of 5 rpm, while the shells had a muzzle velocity 925 metres per second (3,030 ft/s), for a maximum firing range of 27,400 metres (30,000 yd), at 45°. These guns stayed in place until the “swap” -after Japan revoked all treaties-, before the war broke out in Europe.

The swap: 5×2 20.3 cm/50 3rd Year Type 2 guns

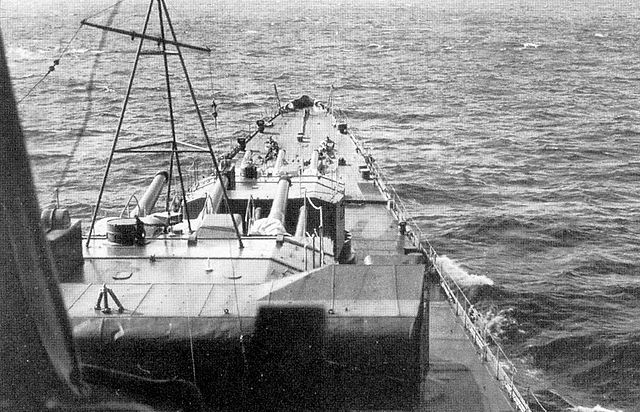

Mogami 1943, forward turrets seen from the bridge

It was done on all four from January 1939 and up to march 1940 in Kure. These 203mm/50 3-shiki 2-go imposed the fitting of new barbettes, and modifications of the well below and reloading system. It was more complex than anticipated and led to a better design for the following Tone class. The 203mm/50 3-shiki 2-go were not either the same as the previous Takao class. There were derived from the latter, but improved, for the 1939 pattern.

These guns, produced by the Muroran Ironworks were quite an improvement over the previous model (1-go) as they used a 33.8 kg (74.5 lb) powder charge to fire 8 in (203.2 mm) projectile, 125.85 kg (277.5 lb) at 835 m/s (2,740 ft/s), compared to a faster (870 ms), but lighter 7.9 in 110 kg (242.5 lb) shell.

These guns weighted 18.7 tonnes, 10.31 metres (33.8 ft) in all, barrel only 10 metres (33 ft), with an exact caliber of 203.2 mm, 3 rpm, and max firing range of 29 kilometres (18 mi). Their Type 91 AP shell impact velocity went from 5 km (3 miles) at 2133 ft/s (650 m/s), to 1247 ft/s (380 m/s) and 25 km (15 miles) at 30° elevation, which was 55°, with the type C and D turrets. The larger barrels and turret obliged however to permanently raise the turret ‘B’ barrels above the roof of ‘A’ turrets to fit in. There was an interruptor gear to avoid collisions when traversing.

Secondary: Four twin 127 mm (5 in) guns

Mogami 1943, starboard side AA armament

These classic dual purpose secondary guns has beel well seen in previous classes. The 12.7 cm/40 Type 89 naval gun had the following characteristics:

- Weight: 3,1 ton (6,834 lb)

- Barrel length: 5,080 millimeters (16 ft 8 in)

- Shell: Fixed 127 x 580mm 20.9–23.45 kgs (46.1–51.7 lb)

- Breech: Horizontal breech block

- Elevation: -8° to +90°

- Rate of fire: 8-14 rounds per minute

- Muzzle velocity: 720–725 meters per second (2,360–2,380 ft/s)

- Max Ceiling: 9,440 meters (30,970 ft) at 90°

- Max Range: 14,800 meters (48,600 ft) at 45°

AA battery: Four 40 mm/62 (1.575″) “HI” Type 91

Initially it was quite symbolic, comprising just four single 40 mm (1.6 in) AA guns. These were an old 1923 design, licenced in Kure from Vickers WWI 2-pdr AA gun Mark II.

The were instroduced in 1925 and deployed on Many IJN ships 1925 to 1935, from a stock of 500 imported from Britain, plus 200 mount, the rest were licence-built. Theu used a 50 round belt although the Japanese tried, but failed to conceive a 100 rounds belt. They were obsolete in 1935, due to their poor muzzle velocity, slow rpm and short range, and thus removed for replacement by 25 mm AA at the first occasion, before the war.

- Gun Weight: 619.5 lbs. (281 kg) with cooling water jacket

- Gun Length: 98.5 in (2.502 m)

- Rate Of Fire: 200 rpm

- Shell: 2.95 lbs. (1.34 kg)

- Propellant Charge: 0.243 lbs. (0.11 kg)

- Cartridge: 40 x 158R

- Muzzle Velocity: 1,969 fps (600 mps)

- Approximate Barrel Life: 5,000 rounds

- Range, AA Ceiling +85°: 13,110 feet (4,000 m

Modernized AA battery:

In 1938-40, all four ships received four twin 25mm and two twin 13.2mm MGs. These were standard issues Type 96 AA guns, well covered in other posts; In 1942 this was reiforced by ten triple 25mm/60 96-shiki, but this varied from ship to ship and went to 50 tubes at the end of the war while the inneficient 13.2 mm were likely removed in 1944.

Torpedo tubes:

This too, changed during their active life. At first, they were to be equipped with four quadruple 21-in TTs, but soon this was swapped for triple banks with the new Type 93 “Long Lance”. The four triple banks of 610 mm (24 inches) were located aft, in niches of the main deck, in the superstructure. These TTs had also 24 reloads (18 for the next two cruisers), and a fast semi-automated reload system which allowed them to fire two full volleys in succession. For weight reasons, the supply was reduced to 18 torpedoes and later in 1942, but augmented again to 24. Just recalls the Type 93 could reach 40,400 m (44,200 yd) or go up to 96 km/h (52 kn) at a slightly reduced range. Nothing was comparable in any navy.

Modifications:

Detailed scheme of the Mogami’s bridge.

Durring the war, many modificatiosn were done: New twin turrets, better catapults to cope with heavier seaplanes of the F1M and E13A generation, torpedo stowage increased to 24 torpedo, relsulting in a final, fully loaded displacement rising to 15,057 for the first pair, and 14,795t for the second. In late 1942, Mogami was completely rebuilt (see dedicated section later) as an hybrid cruiser. In April 1943, Suzuya and Kumano were given two extra twin 13.2m/76 AA and an additional four triple 25mm/60 Type 96 plus were fitted with the Type 1 2-go radar. In 1944, between April and July, they obtained eight single 25mm/60 96-shiki and then four triple of the same, ten single, plus the Type 2 2-go and Type 3 1-go radars. In July, Kumano was the last modified, with sixteen 25mm/60 Type 96 AA guns, and same radars.

Onboard Aviation

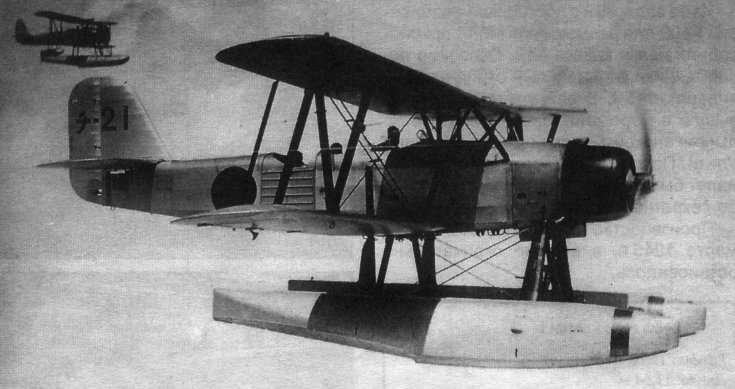

Kawanishi E7K1

Two models were allegedly used by these cruisers, combined, as three were onboard:

One Aichi E13A1 “Jake” seaplane, and two F1M2 “Pete”; They were served by two side catapults, with 180° traverse. The full deck was criss-crossed by rails to manage them between launches, as there was no hangar. The planes were just stored there and protected by tarpaulins. They were served by a large single lattice boom attached to the aft led of the mainmast tripod. The ship’s relocation of the aft bridge and mast closer to the funnel “cleaned up” the aft deck for aircraft operation and this was considered a new successful feature of the Mogami design compared to the previous Takao/Nachi. However the lack of hangar, forced by a redesign, had the planes out under the elements, with a quicker deterioration and heavier maintenance. Initally, both first pair of cruisers were completed with two Nakajima E4N2, and one E7K1.

-The Nakajima E4N light observation biplane was developed in 1930-31 and 153 were built total, deployed on cruisers. They were mostly replaced by the Nakajima E8N “Dave” but during trials and early service they seemingly shows the E4N, replaced probably in 1937 by the E8N, and from 1941 onwards by the F1M. The Kawanishi E7K (introduced 1935) was the larger, long range reconnaissance model, later replaced by the monoplane E13A. They, too were likely in service from 1936 to 1940 or 1941, seeing action in China.

Aichi E13A1 “Jake”

Quickpecs: Introduced in 1941, this was a monoplane inspired by contemporary German designs such as the Arado 196, and used as long-range reconnaissance model onboard the Mogami class at the time of Pearl Harbor. It was able to reach 376 km/h, and cover 2,089 km (1,298 mi, 1,128 nmi), so more than double the F1M.

F1M2 “Pete”

Quickpecs: Introduced in 1941, this model had a long a rocky development starting in 1936 after its first flight. 944 were manufactured until 1944. It was capable of covering 740 km (460 mi, 400 nmi) and speed up to 370 km/h (230 mph, 200 kn), used for observation onboard.

Aichi E16A Zuiun “Paul”

This model in development was called to be operated from IJN Mogami when rebuilt as an hybrid carrier cruiser; This was the new generation of high performance reconnaissance planes of the IJN, destined to replace all models in service, from a specification of late 1939. 256 were built until 1944. The first flight was done in 22 May 1942, but this model was plagues with problems and it was only introduction by February 1944. Meanwhile Mogami was completed with a more classic air group, it’s not sure she swapped on the new Zuiun after she was repaired after battle damage in late 1943, repaired until mid-February 1944, or in her last refit in June. She met her fate on 25.10.1944 in battle in Surigao Strait, probably with her provisional air group.

General assessment of the class

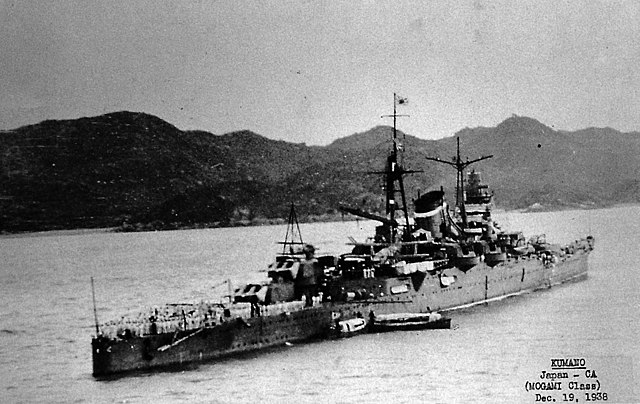

IJN Kumano in target practice off cape Ashizuri 1939

The Mogami class is now largely seen among authors and naval architects as a desperate attempt to fit a circle into a smaller square; By wanting at any rate to be qualitatively superior to foreign designs, the Imperial Japanese admiralty insisted for each new class to push the boundaries of what was possible in terms of speed, armament and even protection on the lightest package in order to maximize every gram authorized by treaties. Japanese naval constructors were placed in an increasingly dificult position by the harsher conditions of the 1930 and 1935 treaties.

The Royal Navy’s Director of Naval Construction (DNC), one briefed by Naval Intelligence about the public displacement figure announced by the Japanese associated with their actual capabilities, famously said in 1935 “they must be building their ships out of cardboard or lying”. Of course this search ultimately ended with grave stability, vibrations and structural issues that had to be corrected later, once treaties would be denounced, which actually happened in 1936. Promptly all these defective treaty cruisers were almost rebuilt to fix their issues, a process than went on until 1940 for some vessels.

The Mogami class made a great impression internationally, influencing both the British “Town” class cruisers and especially the USN Brooklyn-class cruisers, which arrived at the same level with their light artillery, but faster due to their more advanced semi-automatic reloading system. However, also designed over a severe 10,000 tons limit, they proved under-protected and poorly upgradable in the future.

Construction and modifications

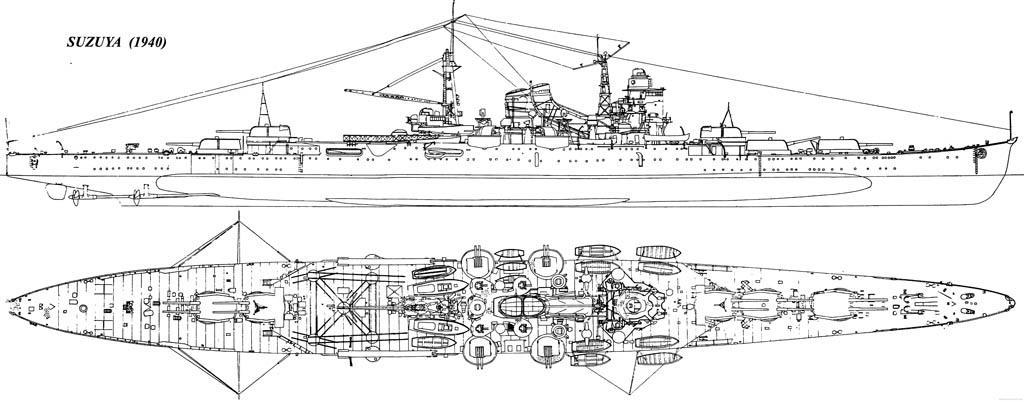

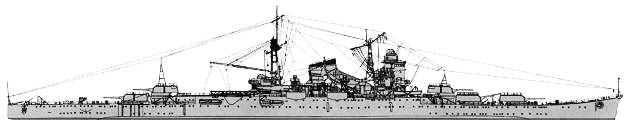

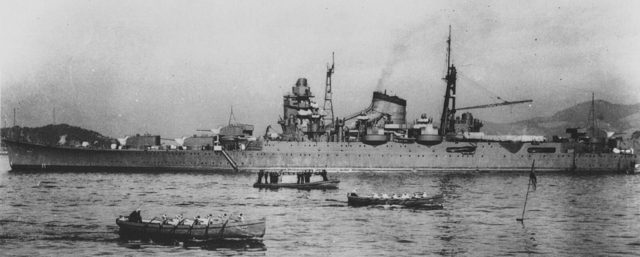

IJN Suzuya on completion, 1935

The Mogami class cruisers comprised four ships: Mogami, Mikuma, Suzuya, and Kumano, launched in 1934 (1936 for Kumano), completed in 1935-1937, built at Kure, Mitsubishi in Nagasaki, Yokosuka and Kawasaki or Kobe yards. Sea trials revealed problems for the first two, the usual vibrations problems due to the structural weakness in the hull. This was so severe than both the fire control director and turrets were unusable. The last two were built later and promptly reinforced, and their design revised. They received bulges for stability, and reinforcements all along the hull. Mogami in fact went straight back in drydock for a refit in 1936-38 and in addition to the above modifications, had an heavy internal bracing.

Various blueprints covering the cutaway profile, top view, cutouts of the hull’s sections.

In 1937, following the denunciation of the 2nd London Naval Treaty of 1936, the IJN decided to modernize and refit her existing units, which included the recently completed Mogami and Tone classes. The barbette diameter of the Tone class was changed during construction there were no problems for them to fit the 20cm twin gun turrets used on the other cruisers but Mogamis was already finished by this time so construction new turrets postponed their refit. This (‘third efficiency improvement’, ‘ main gun replacement works’) allowed an easier swap from 155 mm triple to 203 mm twin turrets, it was followed by the replacement of the Type 90 by the dreaded Type 93 “Long Lance” and replacing side seaplane catapults (heavier and stronger models) and installation of a torpedo-firing command station located on top of the mainmast.

In 1939, there was a plan to have the completely rebuilt and this went with fitting the twin 8-in turrets planned from the beginning, although the barbettes differed. In all they had some 3,700 tons of additions. A second series of modifications followed in Kure in 1939-40, and no les than twenty 8-in twin turrets were prepared for the swap. Protection was further improved, AA reinforced, initially four 5-in DP twin turrets, four single 40 mm AA, but soon it went to twenty, then thirty 25 mm AA in single, twin and triple mounts (fifty in 1944, at Leyte). Due to these additions, the quadruple TT banks were replaced by four triple, still making a volley of six very long range ordnance (and reload). Also it was found their new reduced superstructures offered less vulnerability, inspiring the last Japanese cruisers designs.

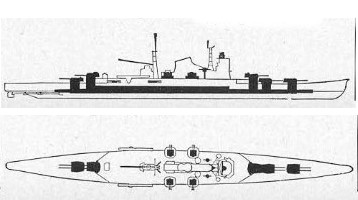

INJ Mikuma as completed in 1935, showing her original triple turrets

IJN Mogami in May 1943, rebuilt as an hybrid aviation cruiser (6 seaplanes onboard)

⚙ Mogami class specifications 1941 |

|

| Dimensions | 201.6 x 20.6 x 5.5 m (661 x 67 x 18 feets) |

| Displacement | 9,500 tons standard, 11,800 tons Fully Loaded |

| Propulsion | 4 shafts geared steam turbines, 10 Kampon boilers, 152,000 hp. |

| Speed | 37 knots (69 km/h, 43 mph) |

| Range | 8000 nm @ 14 knots. |

| Armament | 5×2 8-in/50 (203 mm), 4×2 5-in DP (127mm), 4x 40 mm AA, 4×3 24-in TTs (610mm) |

| Protection | Belt 3.9 in, decks 1.4 in, turrets 0.98 in, Mags: 5 in |

| Aviation | 3 × Aichi E13A floatplanes (see notes) |

| Crew | 850 |

General assessment & mods in wartime

Wartime modifications

Mogami hybrid cruiser reconstruction (1943)

Blueprint of the Mogami after reconstruction

After the battle of Midway (Mikuma sunk, Mogami heavily damaged) in August 1942 and up to April 1943, Mogami repaired but also converted into an aviation cruiser. This move was thought by the general staff simply to increase awareness of the fleet, by having an organic scouting capability in the cruiser division. One motivation for this radical reconstructionwas that Mogami was heavily damaged and neede dit at first, and this went on in around four months, with the entire aft section razed, ammo storage rooms modified to house gasoline and ammunition for the seaplanes.

The already existing aircraft deck was extended to the stern, widened beyond the beam also, with a rail system to move the eleven Aichi E16A Zuiun floatplanes as planned on deck. At first however, due to the Zuiun troubled development, she carried a mix of Mitsubishi F1M Pete and Aichi E13A Jake floatplanes, as other Mogami class ships. Her light AA armament was increased during this refit, and with associated directors, to four twin and ten triple 25mm/60 type 96, two twin 13.2 mm, and an 1-shiki 2-go radar. Final specs after this was a displacement of 12,206 standard, 13,940t FL with a draught of 5.89m, and maximal speed augmented from 34.7 to 35kts as shown on trials.

After this conversion of nine months her main role was of fleet support, providing reconnaissance and scouting for the fleet. She could launch all her planes in roughly 30 minutes.

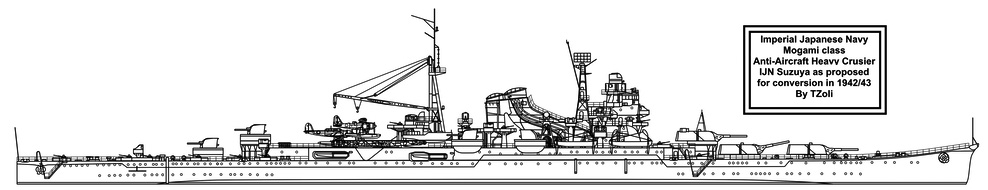

Suzuya AA reconstruction (1943)

Tzoli illustration of the planned AA variant

Plans were drawn up also to convert IJN Suzuya and Kumano, but specifically this time as Anti-aircraft cruisers to provide a fleet escort, recoignising the threat of USN aviation in 1943. This was not entirely carried out, but this included replacement of the main twin turrets by twin of the new 127 mm (5 in) DP-AA mounts (so five twin) and massively increase light, possibly with triple, twin and single mounts, up to 80.

Original plans were marred by an acute wartime shortage for the new 127 mm DP guns, as well a suitable dockyard for this conversion: With frequent repairs they were at full capacity. Suzuya was the only converted, having their aft main turrets replaced, but keeping the same forward battery making it equal to the Furutaka/Aoba in firepower. It was also planned for IJN Kumano this full conversion, which in her case would also include replacement of the main gun rangefinder, with a new High-angle rangefinder and extra Light AA director towers for better coordination of the 60 to 80 barrels onboard. This was never carried out.

Planned aircraft carrier conversion (Summer 1942)

Planned conversion of the Tone class as aicraft carrier, that would have been broadly similar for Mogami, if not converted as a hybrid carrier.

Two more ships of the Mogami class were ordered in January 1942 (第301, or “301 go”) at Mitsubishi, Nagasaki, BU incomplete, and IJN Ibuki at Kure K K laid down on 24.4.1942, launched 21.5.1943 and rebuilt as aircraft carrier from 12.1943. She was BU incomplete.

Shortly after Midway proposals were made to replace carrier losses by completing existing ships in construction as aircraft carrier and convert/build others. Conversion plans were made for all cruisers and battleships in current construction. For battleships, only Ise-Hyuga so completed as hybrids, and they would have been followed by Fuso and Yamashiro.

The three left Mogami and two Tone class were also scheduled for conversions, estimated about 8 months to finish. Plans proposed for the full decked models, with an island, about 195-200m per 23,5m in width at the flight deck and an estimated capacity of 30 planes. In fact only Ibuki was chosen in 1943, but she was never completed before the end of the war.

Action Assessment

IJN Suzuya in 1944 (the blueprints)

IJN Mogami and IJN Mikuma were present at the Battle of Midway, in June 1942, under command of Admiral Yamamoto. The two ships were badly damaged by aviation, the first in the confusion of the night, by a serious collision on June 6, 1942, at 2:15 am, then around 5 am, while the Admiral ordered a general withdrawal of the fleet. She was badly damaged by SBD Dauntless dive bombers.

IJN Mikuma did not survive the battle and sank, while Mogami was attacked later in the day. She survived, crippled, sailing to Kure and stayed there in repairs for a long time. As a result, sent back to Japan for full repairs she was eventually rebuilt into a hybrid aircraft carrier, carrying 11 seaplanes. She was thought out for a better coverage to the squadrons. In 1943, she resumed service with also a new revised AA composed of thirty 25 mm guns, in fifteen twin mounts.

Rear deck of the Mogami after conversion

This reconstruction inspired the admiralty, who decided to order the construction of a further two cruisers of the same type, the Ibuki class. Only the first was nearly completed, reconverted in between as a fast aircraft carrier. Mogami participated in the battle of Surigao soon after, and she was savaged by American cruisers’s heavy fire. Suzuya and Kumano, were present at the Battle of Samar near Leyte, falling on Taffy 3, but repelled after an epic defense. This closed the 1944 year on a crushing defeat for the Japanese.

IJN Mogami was sunk on the 25th by Grumman TBM Avenger torpedo bombers. IJN Suzuya was sunk the same way, while Kumano survived, but finally spotted and bombed by other aircraft on November 25, 1944, exactly one month after the disappearance of her twins. Overall, the four cruisers had little trime to train due to their initial defects, which imposed reconstructions. Contrary to the Takao and Nachi class, their crews were largely “green” in 1941, unlike the “China veterans” of the other cruisers, and they largely were sidelined to convoy protections missions and landing cover, or commerce raiding (like in the Indian Ocean Raid).

Their bombardment role at the opening of “Operation Mo” was an ill-fated one, but mmotivated essentially by their great speed, the best of any cruiser at that time. It was hoped that they could negate air power on the island and destroy all installations before the invasion force could arrive in harm’s way. A sound, but dangerous plan. A counter-order followed by very late decoding, placed them in harm’s way, and an ambush by USS Tambor, followed by a wrong manoeuver practically cost the fleet half of the class. Call it bad luck, it was a serie of mishaps, that combined to create the perfect catastrophy. Hunt down by air groups they precisely came to destroy, IJN Mikuma was sunk, while Mogami was badly damaged and the decision to convert her as a “scout cruiser”, although logical at the time, was not very successful overall and cost her a long immobilization. This led only the second class (Kumano) to took the bulk of the action in the long Carolines campaign.

They only took frontline duties at the Battle of Leyte, sent to Samar in a mission that looked like a breeze due to the expected opposition, there again, unexpected resistance from destroyers and escort air group cost the Japanese Navy their last two cruisers (Mogami was sunk at Surigao Strait). They never were pitted in classic cruiser-to-cruiser engagements, like those of the Java sea or Kolombangara, which made an assessment of their true fighting capabilities more difficult. However due to their greater speed and still impressive armament, plus radars and impressive AA in late 1944, they could have done way better. After being rebuilt, they still showed good damage resistance in combat and their damage control crews seemed good enough to retard or avoid the inevitable, and human losses were relatively mild in comparison to many other tragedies of the war.

Mogami was basically destroyed by cruisers, but by night and with apparently neither their radar or excellent lookouts able to prevent the USN ambush. Precise 8-in shells destroyed her brige, depriving her of any efficient counter-battery fire, and soon mobility due to PT-Boat’s torpedoes, the latter showing again their utility there. This made easier for other cruisers to finish her off, using what was at the time, the world’s best and most accurate firing direction radars for gunnery.

IJN Mogami in Kure, July 1935, sea trials.

Sources and resources

More profiles

Blueprint 2 views, IJN Suzuya after reconstruction in 1940

Rigging scheme, IJN Suzuya 1941

Artists impression of Suzuya in 1944- Color, CC

Books about the Mogamis and IJN

Conway’s all the world’s fighting ships 1922-47

Campbell, Naval Weapons of World War Two, pp. 185-187

Watts, Japanese Warships of World War II, p. 99

Lacroix, Eric & Wells II, Linton (1997). Japanese Cruisers of the Pacific War.

Whitley, M. J. (1995). Cruisers of World War Two: An International Encyclopedia

Brown, David (1990). Warship Losses of World War Two. Naval Institute Press.

Dull, Paul S. (1978). A Battle History of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1941-1945

Jentschura, Hansgeorg; Jung, Dieter & Mickel, Peter (1977). Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869–1945

Links

Mogami class on the pacific war encyclopedia

Mikuma TabRecMov combinedfleet.com

Invasion of Borneo, giving more details on the cruisers

Capture of the Andaman islands

allied merchant losses Indian Ocean Raid

Mogami variants on forum.worldofwarships.eu

Model kit galore

Fortunately, the four Mogami class were well-covered by manufacturers, starting with all the Japanese ones, both in triple and quad turret versions: Tamiya at the classic 1:350 and 1:700 scale, Aoshima, Marusan, Five stars & Fujimi 1:700 only, but also Nippon Hobby at 1:400, Answer-Angraf at 1:200, IMAI 1:550, then the board game XP Forge and Bandai 1:1200, Fujimi set 1:3000, parts with finemolds, and Fukuya 1:350 and Rainbow, White Ensign for the 1:700 Tamiya kit, or the FlyHawk Model 1:350.

The mogami query on scalemates

The IJN Mogami 1/350 model pre-Midway on Tamiya’s site, w/wt hull (twin turrets).

IJN Mogami (July 1935)

IJN Mogami (July 1935)

Mogami after being refitted with 8-in guns 1940

IJN Mogami was completed at Kure Naval Arsenal on 28 July 1935 under command of her first captain, Tomoshige Samejima (formerly on Kitakami), until November 1935 and commission, replaced by Captain Seiichi Itō, himself until April 1936, and then Shunji Isaki until January 1941. All this time, the crews trained extensively in home waters, she never operated along the coast of China. Full logs of her prewar career (combinedfleet.org). The most critical event in their early career she was badly damaged by a typhoon, during the annual fleet exercize on 26 September 1935, along with MIKUMA.

In mid-1941, IJN Mogami took pat in her first abroad deployment. She took part in the fleet tasked for the occupation of Cochinchina (French Indochina) from the operating base on Hainan. Japan and Vichy French authorities reached an agreement, allowing the Japanese to use their airfields and harbors, from July 1941.

Mogami in trials, 1935

During the attack on Pearl Harbor, IJN Mogami was assigned to cover the Japanese invasion of Malaya as part of Cruiser Division 7, Vice Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa (1st Southern Expeditionary Fleet). She provided close gunnery support for the landings of Japanese at Singora, Pattani and Kota Bharu. Next, she was sent to participate in the invasion of Sarawak with Mikuma, covering the landings at Kuching. In February 1942, after a supply run at Hainan, she was assigned to cover landings in Java, Borneo and Sumatra. On 10 February 1942, she teamed with IJN Chōkai wehn both were attacked by USS Searaven, which missed.

Battle of Sunda Strait

IJN Mogami, nice fwd view underway 1936

On 28 February 1942, IJN Mikuma and Mogami, the cruiser Natori, escorted with the destroyers Shikinami, Shirakumo, Murakumo, Shirayuki, Hatsuyuki and Asakaze engaged the USS Houston and HMAS Perth with gunfire and torpedoes, after the latter attacked a convoy in Sunda Strait. Houston and Perth were sunk in this engagement, but the Japanese lost the transport IJN Ryūjō Maru, with IJA 16th Army commander Lieutenant General Hitoshi Imamura aboard. Nevertheless, opposed to “comparable” cruisers, they proved quite efficient, notably by the use of their “long lance” right away in the dark.

In March 1942, IJN Mogami with the Cruiser Division 7 steamed off Singapore, covering Japanese landings on the Bangka Island, off Sumatra and proceeded to the Andaman Islands. She later took part in the Indian Ocean Raids, from 1 April 1942 departing from Mergui, Burma to team with CruDiv 4. IJN Mikuma, Mogami and the destroyer Amagiri were detached as the “Southern Group”. They preyed on the merchant shipping in the Bay of Bengal and claimed also the 7,726-ton British passenger ship Dardanus as well as the 5,281-ton steamship Ganara, 6,622-ton merchant Indora underway to Mauritius. On 22 April she was back to Kure and dry dock for overhaul, departing again on 26 May for Guam and assigned to Rear Admiral Raizō Tanaka’s Midway Invasion Transport Group’s protection.

Battle of Midway

On 5 June 1942 Cruiser Division 7, this time with all four Mogami-class cruisers reunited was ordered to shell Midway Island, in preparation for a landing. Thisunit was escorted by DesDiv 8 and from 410 miles (660 km) off the island made a 35 knots (65 km/h) “made dash” to the Island, in choppy seas and leaving the slower destroyers behind. However as they proceeded, at 21:20, the order was canceled. Nevertheless, this brought them on the pathway predicted by the submarine USS Tambor. The US sub was spotted by IJN Kumano’s scout plane, signalling a 45° turn to starboard, correctly executed by the flagship, and IJN Suzuya, but Mikuma erroneously made a 90° turn.

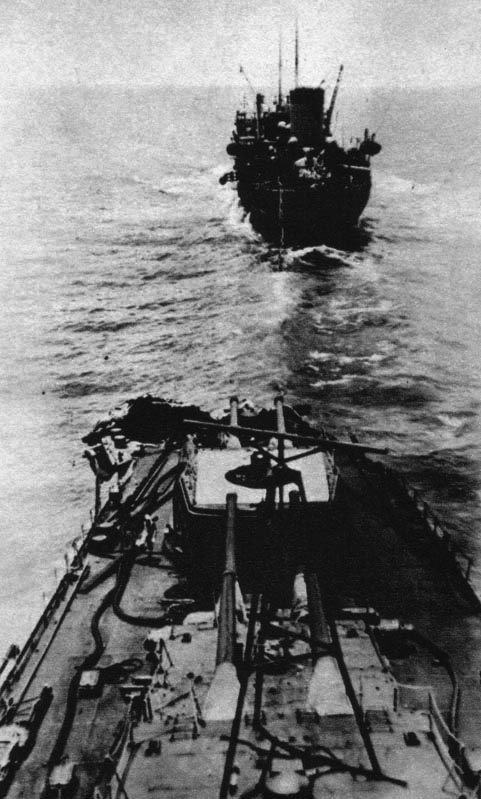

Mogami and Nichiei Marus after Midway

Mogami was just behind and turned 45° as commanded but collided soon with Mikuma: She rammed her portside below the bridge and her bow caved in as the result. Mikuma’s own portside oil tanks ruptured, but damaged was otherwise light. Both were protected by IJn Arashio and Asashio for their slow return. Nevertheless, at the first hours at dawn, they had been spotted by radar and attacked by USAAF Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses from Midway, at high altitude. As often in that case, all missed. At 08:05 also from Midway, they were attacked by six USMC Douglas SBD Dauntless and six Vought SB2U Vindicators, making only near-misses.

But this was still not over. On 6 June 1942 morning, as both cruisers were heading for Wake Island, the position has been signalled to USS Enterprise and Hornet, which launched at them three waves of 31 SBD Dauntless. As a result, IJN Mikuma was hit by at least five bombs, badly damaged as the fire also ighited her torpedoes and she was soon devastated by a serie of catastrophic explosion, sinking quickly as a reslut. Arashio and Asashio were also hit by bombs. IJN Mogami herself too six hits, having her “Y” turret blown apart, other hista long the hull and 81 crewmen killed. Lieutenant Commander Masayushi Saruwatari, seeing what happened on Mikuma ordered quickly to jettison torpedoes and other explosives. This arguably saved her. Damage parties were eventually able to control the fires and she was able to steam again.

IJN Mogami was back to Cruiser Division 7, on 8 June. She had provisional repairs in Truk. Under escort she returned to Japan, for repairs and major conversion at Sasebo Naval Arsenal which tool place from 25 August until 30 April 1943. She was re-commissioned into the 1st Fleet, CruDiv 7 but on 22 May, collided with oiler Toa Maru in Tokyo Bay. On 8 June in Hashirajima she was moored close to IJN Mutsu when the latter exploded and sank. Her own damage was light, and she sent all her boats to attempt a rescue, making none. On 9 July 1943 she departed for Truk escorting a major troopships and supplies convoy, unsuccessfully attacke dunderway by USS Tinosa. After Truk, they proceeded to Rabaul and in August-November, IJN Mogami made several sorties from Truk in response to USN attacks on the Marshall Islands.

On 3 November 1943, CruDiv 4, 7 and 8 were assigned to the Solomon Islands campaign, an attack off Bougainville. Whe stationed at Rabaul on 5 November, IJN Mogami was attacked SBD Dauntless from USS Saratoga, hit by a single 500 lb (227 kg) bomb (19 killed). Fire damage was controlled and she was repaired in Truk by the fleet workshop IJN Akashi. She was able to return in Japan, Kure for more repairs and modernization from 22 December to 8 March 1944. She was able to return and participate in the Philippines Campaign:

Battle of the Philippine Sea

Mogami 1943, forecastle view

On 13 June 1944 she was assigned to Rear Admiral Takatsugu Jojima’s “Force B” (Carriers Jun’yō, Hiyō and Ryūhō, battleship Nagato behind Kurita’s “Vanguard Force C” in protection of the Philippines. At 05:30 on 19 June, IJN Mogami launched two reconnaissance floatplanes, while soon TF 58 off Saipan was attacked but largely repelled in the “Great Marianas Turkey Shoot”. At 20:30, 20 June, Hiyō was lost and this night Mogami departed back to Okinawa, and to Japan in Hashirajima, then Kure on 25 June 1944.

After her last refit, where she possessed a total of 60 barrels (14×3 and 18×1 AA guns) plus the new radars Type 22 and Type 13, she trained and departed on 8 July via Okinawa and Manila for Singapore, to operated off Brunei, until October, training with the rest of the fleet close to the fuel sources.

Battle of Leyte Gulf

In the morning of 24 October 1944, Nishimura ordered Mogami to launch all her floatplane in Leyte Gulf. One reported four USN battleships, two cruisers and 80 transports and also four destroyers and MTBs near Surigao Strait, and later twelve carriers, ten destroyers 40 miles (64 km) southeast of Leyte. During the attack on Sulu Sea (By Enterprise and Franklin), Mogami was damaged by strafing and rockets, but still able to proceed. She was to take part soon in the Battle of Surigao Strait.

On 25 October, about 03:00-03:30, she was attacked by PT boats and destroyers, seeing Fusō and Yamashiro hit by torpedoes, Yamagumo sunk, Michishio disabled. Amazingly, Mogami was unscathed. But after entering the Strait, she was hit by four 8-inch shells from USS Portland. Her bridge was knocked-off, as her air defense center, captain and staff killed on the spot, she was disabled, commanded by the chief gunnery officer, but as she retired, she collided with IJN Nachi, her bow damaged open, flooding rapidly. However this time, fires reached her torpedoes that exploded in succession. She lost her starboard engine and later picked again by radar, hit by a deluge of shells and hit by 10 to 20 6-inch and 8-inch shells from Portland, Louisville and Denver.

At 08:30 she lost her port engine and became adrift, powerless. The coup de grace was given by 17 TBF Avenger from TG77.4.1. She was struck by two 500-lb. bombs and burned furiously. So much the damage party could do little. Order was given to abandon her at 10:47, shile she stayed afloat for two hours and scuttled by torpedoes, at 12:40 by IJN Akebono. She sank at 13:00, but 700 were rescued. She was stricken on 20 December 1944.

IJN Mikuma (Aug. 1935)

IJN Mikuma (Aug. 1935)

IJN Mikuma in 1939

IJN Mikuma was completed at Mitsubishi on 29 August 1935 under command of Captain Suzukida Kozo and her trials revealed that firing all her main battery guns at once popped the welds along her sides. This and countless other problems, some structural, some related to vibrations, others to her stability, comprmised her early service, which started with the annual large fleet exercises, when she was catch by a typhoon, and damaged as a result. In November while in repairs, Captain (later Vice Admiral) Takeda Moriji was appointed, replaced by Iwagoe Kanki in Dec. 1936. She really returned into service from December 1937, but apart drilld, not much happened.

In 1939, under command of Captain Kubo Kyuji, and later Kimura Susumu, IJN Mikuma underwent a substantial reconstruction. As planned, her triple 6 in turrets were removed and their barbettes and wells were modified, as well as the ammunitions storage. She obtained her twin 8 in guns turrets, her former turrets being fitted on the battleship Yamato. Torpedo bulges were also fitted for a better stability.

By September, afer post-reconstruction trials and training, IJN Mikuma (under command of Shakao Sakiyama, her last captain) participated in the occupation of Cochinchina (French Indochina) and from July 1941 her new forward operating base became Hainan, the most subtropical island of China, close to Indochina. In December 1941, when the attack on Pearl Harbor took place, IJN Mikuma covered the invasion force to Malaya, CruDiv 7 (Ozawa’s 1st Southern Expeditionary Fleet) followed by gunnery support on Singora, Pattani and Kota Bharu.

Next, like her sister ship Mogami, which was her teammate, she covered landings on British Borneo, Miri and Kuching. In February 1942, she covering landings in Sumatra and Java but while underway on the 10th as she was with IJN Chōkai both were torpedoed -but missed- by USS Searaven.

Mikuma at the Battle of Sunda Strait

Mikuma’s forward deck seen from the bridge

At 23:00, 28 February, CruDiv 7, escorted by 5 DDs and the light cruiser Natori engaged USS Houston and HMAS Perth. At 23:55, Houston managed to hit Mikuma several times. This knocked out her electrical power but the teams worked frantically to have it restored. She ceased fire, but in the dark, this protected her. Battle damage left her six dead, eleven wounded while Houston and Perth were sunk. In March, Mikuma was sent to Singapore, covering landings in Sumatra and also participated in the capture of the Andaman Islands.

From 1 April 1942 her unit moved from Mergui to join CruDiv 4, taking part in the Indian Ocean raids. CruDiv 7 was escorted by the DD Amagiri and they were detached from the fleet to prey on merchant shipping (see Mogami for the tally). On the 22th they were back to Kure, and a well-deserved overhaul. On 26 May, they were in Guam for Rear Admiral Raizo Tanaka’s Midway Invasion Transport Group. So confident was the general staff that they already received orders for after “Operation Mi” (the attack on Midway). They were to proceed to secure the Aleutian Islands far north, and afterwards were scheduled to plan for the preliminary operations against Australia. Little the crew knew about their fate.

Fate: Battle of Midway

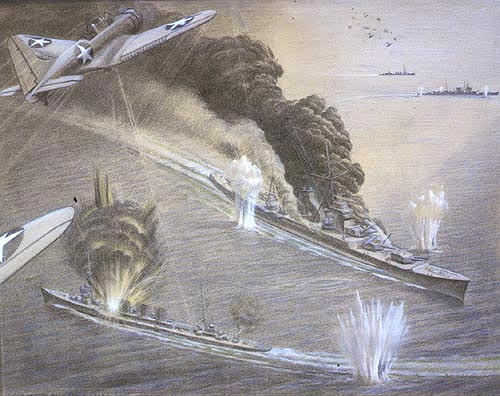

Mogami and Mikuma at Midway, 6 June, Charcoal-Chalk drawing by Griffith Bailey Coale, USNR

On 5 June, Yamamoto odered CruDiv7 to proceed at full speed to Midway, shelling airfields and installations in preparation for the landing. With DesDiv 8 soon left behind in the heavy weather, they were about 410 miles (660 km) from their objective when the orders were cancelled, the latter being only decoded and applied the following day at 02:10 just 50 miles (80 km) off Midway. Soon they were engaged by USS Tambor, spotted by Kumano, turning hard to starboard to avoid possible torpedoes, but Mikuma’s captain Shakao Sakiyama erroneously made a 90° turn, being rammed by IJN Mogami, making her portside oil tanks rupture and spill oil. Both cruisers stayed behind, dangerously close, protected by the destroyers Arashio and Asashio. They were to proceed back to Guam, but soon were spotted again, after the sub gave the alert.

On Midway, general quarters has been signalled and everybody was on deck of the “unsinkable aircraft carrier”. At 05:34, eight Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses were the first to take off, and they bombed thme from high altitude, making only “far misses”. But the hunt was on, and on Midway’s airfield, ground crews prepared fevereshly other waves to take off: At 08:05, these were six USMC SBD Dauntless and same number of SB2U Vindicators. The attack was more precise, but the USMC pilots lacked training and even the Dautlesses, used in conventional bombing, failed to make any direct hits. Japanese staff however were astonished to see one Vindicator (Capt. Richard E. Fleming, postumhous MoH) shot in flames, neverthless attempting to bomb and crash on Mikuma, narrowly missing her and hitting the sea. That was a first clue about the the defender’s resolution.

The following morning on 6 June 1942, still underway to Wake Island the US aircraft carriers took part in the huner and their three waves of SBD Dauntless (31 aircraft), this time all trained to dive-bombing, arrive on them. US pilots were good enough to even hit Arashio and Asashio, manoeuvering as hell. Mogami was hit by six, Mikuma by at least five. Her forecastle, bridge, amidships superstructures, were all set afire. The forward guns were out of order, and AA shells in flames ricocheted on the bridge, caused damage and killing/wounding personnel.

Mikuma burning at Midway.

Amidships the fire soon lite up the torpedoes. The Type 93 heavy warheads cooked off and resulting in a serie of tremendous explosions. Captain Sakiyama was severely wounded himself and ordered to abandon ship but it was too late: IJN Mikuma rolled to port, sinking rapidly with almost all her crew but some sources stated she was cuttled by torpedoes the following day. Whatever the case, the Captain was saved by Asashio but died four days later and with Arashio, 240 survivors escaped death. On 9 June 1942, USS Trout rescued two more. They would end the war in Pearl Harbor as POWs. Mikuma was stricken on 10 August.

IJN Kumano (Oct. 1937)

IJN Kumano (Oct. 1937)

IJN Kumano 1938

IJN Kumano was completed at Kawasaki Shipyards, Kobe on 31 October 1937 under command of Captain Shōji Nishimura, until May 1939. Modification work was done at Kure Naval Arsenal until October 1939 so she had little service before WW2 broke out. Her first “operational” commander (in full commission at last) was Captain Kaoru Arima, from 15 November. The war one was one month old. He was replaced on 15 October 1940 and trained his crew hastily to full proficiency as Japan’s turn was just around the corner.

From 16 July 1941, IJN Kumano was assigned to part of Sentai-7 with her three sister ship, based out of Hainan, southern China, able to intervened and support the Japanese invasion of French Indochina. When the attack of Pearl Harbor was launched, the entire unit was committed in other simultanous operations against the British. IJN Kumano had the honor of being flagship, Vice Admiral Shigeyoshi Inoue, for the IJN 4th Fleet. They took part in the invasion of Malaya (1st Southern Expeditionary Fleet), Singora, Pattani and Kota Bharu.

On 9 December 1941, IJN I-65 reported Force Z, received by IJN Sendai, promptly relaying the message to Ozawa, flagship IJN Chōkai. Due to poor receiption, 90 min. were needed to decode it fully, added to the fact it was also incorrect about the Britush fleet heading. Two Aichi E13A1 “Jake” were promptly catapulted from Suzuya and Kumano to confim the exact location of Force Z and shadowed it, but they eventually ditched at sea, due to lack of fuel. Suzuya’s crew was later recovered. On the 10th, Force Z, now fully tracked, was assaulted by a massve strike of “Nell” Navy bimotor torpedo bombers (22nd Air Flotilla), taking off from Indochina. Singapore’s fleet was wiped out.

ONI phoos of Kumano underway, 1942

Later, IJN Kumano and Susuya were tasked with the invasion of Sarawak, and the landings at Miri. From Cam Ranh Bay they also covetred landings at Anambas, Endau, Palembang and Banka Island, then Sabang on Sumatra and Java, starting the Netherlands East Indies campaign, until mid-March. Next was the invasion of the Andaman Islands, and the Indian Ocean raid from 20 March 1942, Kumano, Suzuya and Shirakumo detached to prey on merchant traffic, sinking Silksworth (4,921 tons), Autolycus (7,621 tons), Malda (9,066 tons) Shinkuang (2,441 tons) and the US steamship Exmoor (4,986 tons). One E8N “Dave” floatplane from IJN Kumano was damaged by a Curtiss P-36 Hawk from RAF No.5 based in Cuttack, India. IJN Kumano then headed back to Japan, Kure (27 April) for an overhaul, and sent on 26 May to Guam, joining the Midway Invasion Transport Group (Sentai -7, Tanaka) escort.

With other cruisers of the 7th squadron

During the Battle of Midway on 5 June, lookouts aboard Kumano spotted USS Tambor while the four cruisers were en route to Midway for a preliminary bombardment at full speed, and the order was recalled, but as the ships were almost in sight of Midway. Kumano and Suzuya correctly made the turn to avoid a possible launch from Tambor, but not Mikuma, which collided with Mogami. Damaged, they were left on site with destroyer escorts, and were underway at slower speed behind, repeately attacked, from Midway and later from USN aicraft carriers, until Mikuma was sunk and Mogami badly damaged.

IJN Kumano’s forward turrets before 1939

Kumano like Suzuya made it home, in Kure on 23 June. On 17 July, both were assigned as the covering force for the invasion of Burma. Spotted en route by the Dutch submarine O23 they evaded six torpedoes, west of Perak off Malaya, on 29 July 1942. In August, they were reassigned as a reinforcement of Guadalcanal. They participated in the Battle of the Eastern Solomons, on 24 August. IJN Kumano did not saw combat that day. She returned safely to Truk. On 14 September while underway north of the Solomons she was atacked by ten USAAF B-17 Flying Fortress, but only had light damage.

At the Battle of Santa Cruz on 26 October, she supported Nagumo’s Carrier Strike Force. She was back to Kure on 7 November for minor repairs and sent to Rabaul on 4 December 1942 with troops and supplies onboard. The rest of the year was spent in patrols and fast transport missions (Tokyo night express style) until mid-February 1943.

Kumano Damaged after battle.

She was overhauled and modernized at Kure Naval Arsenal on 6 June 1943 and back to Rabaul on 25 June, again to land extra troops and supplies from Japan. On 18 July, she escorted one majot “Tokyo Express” mission with IJN Chōkai and Sendai. She was attcked off Kolombangara by USMC Grumman TBF Avengers from Guadalcanal. Her aft hull was damaged by near-misses from bombs, she had emergency repairs at Rabaul, with IJN Yamabiko Maru, later at Truk with IJN Akashi another fleet workshop and repair ship. She was eventually withdrawn to Kure until 3 November for her last repairs.

In January-February 1944 she was based in Palau, and later in Singapore until mid-May 1944 where she received additional AA. Until June, she was based at Tawi-Tawi but participated in the Battle of the Philippine Sea attacked by planes on 20 June, from USS Bunker Hill, Monterey, and Cabot. She had to return to Kure on 25 June for repairs, although damage was light, resulting from near-misses. She received two new radars here and yet extra AA. On 8 July 1944, she departed with troops and supplies for Singapore. She stayed there until late October.

On 25 October 1944 she was pressed at the Central Force, participating in the Battle off Samar. That day she was targeted by the destroyer USS Johnston defending Taffy 3, receiving a single Mark 15 torpedo, which blew off her bow. She had to retire toward the San Bernardino Strait when surprised by a reinforcement wave of aircraft, but suffered only minor damage. On 26 October she was attacked by USS Hancock air group while in the Sibuyan Sea, this time struck by three 500 lb (227 kg) bombs. But she survived the impact, her damage control teams making wonders. She was able to sailed to Manila Bay for repairs. Her bow needed replmacement in drydock, and her four boilers, wrn-out and damaged as well. On 29 October while in drydock, she was submitted to the fury of combined carriers of Task Force 38, strafed and bombed, which necessitated extra repairs.

At sea again on 4 November, she headed for Formosa (Taiwan) with Convoy Ma-Ta 31. On 6 November 1944 as she was off Cape Bolinao, Luzon, the connvoy was attacked by a USN “wolfpack” composed of USS Batfish, Guitarro, Bream, Raton and Ray, which launched 23 torpedoes simultaneously. Two of these struck Kumano, probably from USS Ray. One destroyed bow (again!), the second destroyed her starboard engine room, enough to cause flooding to all four engine rooms. As a result she soon slowed down to a crawl, listing to 11° and soon without steering. At 19:30, the cargo ship Doryo Maru tried to tow her to Dasol Bay. She was later moved to Santa Cruz, Zambales (Luzon).

Kumano on 25 November 1944

While under new repairs on 25 November she was assaulted by USS Ticonderoga’s air group, Avengers hit while her moored along the peer, and she took five airborne torpedoes, plus four 500 lb (230 kg) bombs. The flooding and fire made her uncontrollable. Nothiong could prevent her demise, as she rolled over and sank at 15:15 in shallow (31 m, 102 ft) waters. 497 (including Captain Soichiro Hitomi) went down with her, but 636 were rescued. She was only stricken on 20 January 1945. These repeated attacks later had Admiral William “Bull” Halsey saying “if there was a Japanese ship I could feel sorry for at all, it would be the Kumano”.

IJN Suzuya (Oct. 1937)

IJN Suzuya (Oct. 1937)

IJN Suzuya on trials, 1937

Suzuya was launched on 24 November 1934 in a ceremony attended by Emperor Hirohito. Like her sister ship Kumano, IJN Suzuya was completed in January 1936, but sea trials revealed many problems: Untested equipment, welding defects, being top-heavy and causing stability problems in heavy weather so she underwent a complete and very costly rebuilding program which ended nearly two years after. She was officially commissioned on 31 October 1937, made her shakedown cruise but returned for her reconstruction until 30 September 1939, WW2 actually has broke out.

IJN Suzuya 1938

A routine of crew drills, yearly manoeuvers in home waters throughout 1940 and up to 1941 started. Under command of Captain Masatomi Kimura, she was dispatched on 23 January 1941, making a show of force after the Battle of Ko Chang in the Franco-Thai War as part of the Kure Naval District’s Cruiser Division 7 (2nd Fleet) with her sister ships. Sher later participated in the summer of 1941 to the occupation of Cochinchina and the rest of her career is pretty similar to Kumano whith which she served with up to a point.

At the time of Pearl Harbor she took part in many landings, as part of the invasion of Malaya, invasion of Sarawak, and later Sumatra and Java. Her observation seaplane also shadowed force Z, but was also lost. She also took part in the Indian Ocean raid on 20 March 1942, sharing the meagre tally of four merchantmen. She also took part in the “Midway run” which ws countermanded as the four cruisers were just a few miles of the Island, when ambushed by USS Tambor

and turning hard. Like Kumano, she did the turn correctly and went back to Wake while her sister ships collided and were soon hammered by B-17 and others along the way.

Next for Suzuya was the long Solomons campaign: On 24 August 1942, CruDiv 7 joined Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo’s Carrier Strike Force northeast of Guadalcanal, leading to the Battle of the Eastern Solomons, in which Ryūjō was sank. Suzuya was too far away to see action that day. She patrolled between Truk and the Solomon Islands until mid-October 1942.

IJN Suzuya 1939

On the 26th, Nagumo’s Carrier Strike force was involved in the Battle of Santa Cruz, a long-range air battle, in which Suzuya was a distant part. She became thereafter separated from her sister ship Kumano. By early November, CruDiv 7 reinforceed Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa’s 8th Fleet based in Shortland. There it was tasked of the bombardment of Henderson Field, Guadalcanal, in the night of 14 November. Suzuya was assisted by the cruisers Maya, Tenryū, Chōkai, Kinugasa and Isuzu and five destroyers. In all she landed on the airfield some 989 8-in shells. On their return they were ambushed by USS Flying Fish, which missed. They were also attacked by the air group of USS Enterprise, and from Henderson Field. As a result, IJN Kinugasa was sunk, Chōkai and Maya damaged but Suzuya escaped unscathed. Until January 1943 she resumed patrols and convoys escort between Truk, Kavieng and Rabaul.

She was overhauled back in Kure on 12 January 1943, receiving additional AA guns and a Type 21 air search radar, plus triple-mount Type 96 25 mm AT/AA Guns. She departed Yokosuka on 16 June 1943 to escort a resupply convoy to the Solomon Islands and made Truk-Rabaul trips without incident until the end of 1943, although on 18 July, she was attacked by USMC TBM Avengers from Guadalcanal off Kolombangara. She only had near misses and little damage from snrapnel.

ONI Photos

On 3 November, she was reunited with IJN Mogami and Chikuma and all three departed Rabaul to shell US landing forces landed at the Empress Augusta Bay at Bougainville Island, but were prevented to do so by US Admiral Merill’s victory. IJN Sendai was sunk in this battle. IJN Suzuya was back in Rabaul on 5 November and was present during a massive carrier raid (Saratoga and Princeton), but not damaged. On 1 February, she assisted the evacuation of Truk, was later refitted in Singapore on 24 March 1944.

On 13 June 1944, under command of Admiral Soemu Toyoda she took part in Operation “A-Go”, to defend the Mariana Islands. IJN Suzuya was part of Kurita’s “Force C” (Yamato, Musashi, Zuihō, Chiyoda, Chitose, Atago, Takao, Maya, Chōkai, Kumano, Chikuma, Tone, Noshiro). The air attacks to Task Force 58 off Saipan were met by crippling losses (“Great Marianas Turkey Shoot”). On 20 June Hiyō was lost and that night, IJN Suzuya retired to Okinawa. The battle was lost.

She was overhauled and refitted in Kure on 25 June 1944, with more AA guns (50 total: 14×3, 18 single) plus the new Type 22 and Type 13 radars. On 8 July she headed for Singapore and Brunei, close to oil supplies, for fleet training and patrols until October 1944 anso receiving the new Type 22 Kai 4S fire control radar.

Its in the Battle of Leyte Gulf she met her fate: As part of the fleet assembled in Brunei she was soon mobilized on 25 October 1944 at the Battle off Samar, falling on US landing forces protected by Taffy-3 with just three escort carriers and a destroyer squadron while Halsey, drawn away by a bait force, was too far to intervene. IN Suzuya started to shell the three “Jeep carriers” of TG 77.4, participating in the destruction of USS St Lô, but she was attacked by ten TBM Avenger, a near-miss destroying her port propeller.

At 10:50 she was attacked yet by thrity more carrier aircraft and another near-miss blew up her Long Lance torpedoes in No. 1 torpedo tubes starting a wild fire and other explosions into her starboard engine rooms, No. 7 boiler room which soon ran out of control. At 11:50 s about one hour, Captain Teraoka ordered to abandon ship. At 13:22 she rolled over and sank. The Destroyer IJN Okinami picked up 401 of the crew and later some US warships rescued others. She was stricken on 20 December 1944 but her wreck never has been located yet, as she is believed to have sunk quite deep. At least this put her out of harm of pillagers, unlike many other ships in the southern pacific, as a proper war grave.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign