US Maritime Commission Built 1938–1946, service 1938–1970, 328 ships

US Maritime Commission Built 1938–1946, service 1938–1970, 328 ships

Foreworld: US Maritime Commission Fleet

Foreworld: US Maritime Commission Fleet

The United States Maritime Commission (MARCOM) was an independent executive agency of the U.S. federal government created by the Merchant Marine Act of 1936, abolished on May 24, 1950. Created at first to replace WWI vintage vessels of the United States Merchant Marine and operate ships under the American flag. It formed the US Maritime Service for training officers and from 1939 until 1945, funded and administered the largest and most successful merchant shipbuilding effort in world's history with 5,777 oceangoing merchant and naval ships total.

♆ Liberty ships - ♆ Victory ships - ♆ Freighters Type C1 - C2 - C3 - C4 - ♆ Tankers T1 - T2 - T3

Development

Type C2 cargo ships were designed by the US Maritime Commission (MARCOM) in 1937–38. They were all-purpose, five holds vessels, and in total 328 were delivered from 1939 to 1945. Unlike the C1, the C2s were tailored for rapid Atlantic crossings, with emphasis put on speed and fuel economy, the latter set to 15.5 knots (28.7 km/h) but with 19 knots (35 km/h) shortruns to ouptpace U-Boats. The first C2s were 459 feet (140 m) long but the sub-classes all varied in size and tonnage, depending on their shipyard. Some were intended for specific trade routes with substantial modifications and most were converted for military use and taken over by the USN, mostly in assault ship and specialized cargo vessels, taking part both in the European campaign, Pacific Campaign and Korean war, even Vietnam war for some. They were well armed with 5-in/38 main guns complemented by 3-in/50 or 40 mm and 20 mm AA guns. They amassed collectively a very large number of battle stars, some indivually had up to 11-12 for their long career, sometimes from 1942 to the 1960s. But most returned to civilian service until the 1970s.

In 1937, MARCOM distributed new designs, taking in account criticism by shipbuilders, ship owners, and naval architects. Final designs incorporated many changes suggested by them, making for reasonably fast but economical cargo ships while still could compete with other nations’s cargos. Indeed the whole program came from the realization in 1939 the US merchant fleet was ageing fast, most of its vessles beiong close to 20 years and more. Building costs were also minimized by standardization of design and equipment, while the design still kept sufficient speed and stability to be requisiutioned and used by the USN as naval auxiliaries in case of national emergency. Which became the case in September 1939, more so in December 1941. According to the War Production Board, in 1943 the C-2 cost $313 per deadweight ton (or 10,800 deadweight tonnage) at a unit cost of $3,380,400 (2020: $48,136,896 adjusted for inflation).

In 1937, MARCOM distributed new designs, taking in account criticism by shipbuilders, ship owners, and naval architects. Final designs incorporated many changes suggested by them, making for reasonably fast but economical cargo ships while still could compete with other nations’s cargos. Indeed the whole program came from the realization in 1939 the US merchant fleet was ageing fast, most of its vessles beiong close to 20 years and more. Building costs were also minimized by standardization of design and equipment, while the design still kept sufficient speed and stability to be requisiutioned and used by the USN as naval auxiliaries in case of national emergency. Which became the case in September 1939, more so in December 1941. According to the War Production Board, in 1943 the C-2 cost $313 per deadweight ton (or 10,800 deadweight tonnage) at a unit cost of $3,380,400 (2020: $48,136,896 adjusted for inflation).

Design

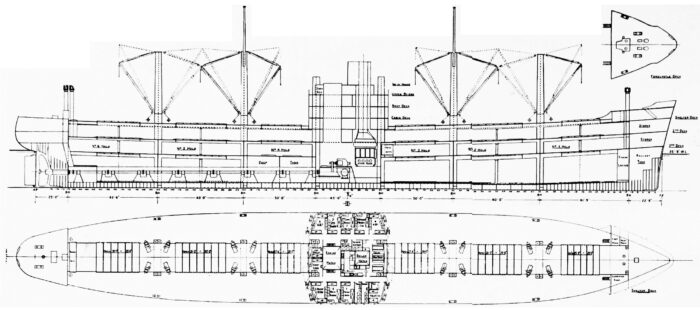

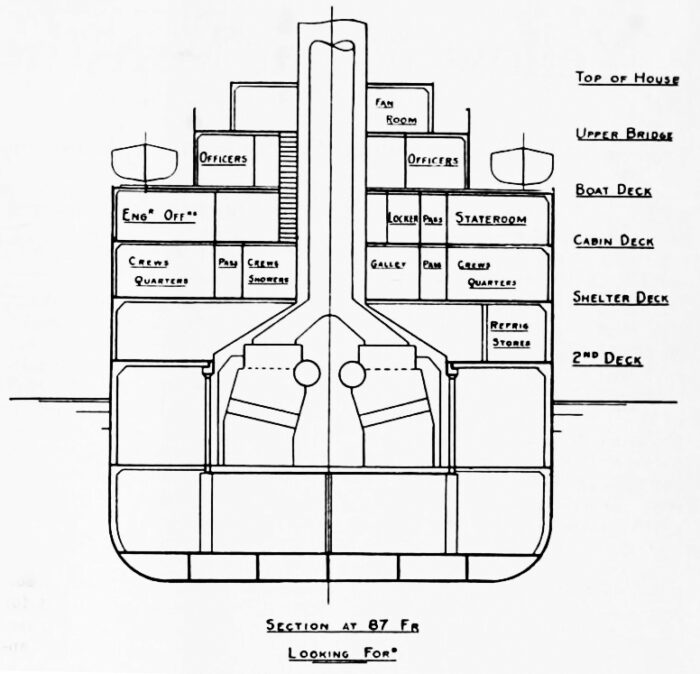

The basic specifications called for a five-hold steel cargo ship with raked stem and cruiser stern, complete shelter and second decks, and a third deck in Nos. 1–4 holds. Dimensions of the hatches were 20 ft × 30 ft (6 m × 9 m), except for No. 2, which was 20 ft × 50 ft (6 m × 15 m), allowing such cargo as locomotives, naval guns, long bars, etc. Ventilation to the holds was provided by hollow kingposts, which also served as cargo masts. Cargo handling gear consisted of fourteen 5-ton cargo booms, plus two 30-ton booms at Nos. 3 and 4 hatches.

Hull and general design

Inboard profile and shelter deck plan of C-2 design standard cargo vessel.

Living accommodations were much improved with crew accommodations amidships, officers quarters on the boat deck, captain’s quarters on the bridge deck, close to the wheelhouse, chartroom, gyro and radio room. There was a central heating with hot and cold running water throughout.

Length: 459 ft (139.90 m), Beam: 63 ft (19.20 m), Draft: 25 ft (7.62 m), AWL Height: 40 ft (12.19 m)

Many like SS Donald McKay were converted by the U.S. Navy in wartime, and commercial versions operated in parallel by the government. From late 1945, surplus commercial ships were resold to various merchant shipping lines for affordable prices, and remained in service until the early 1970s. They never suffered serious structural issues.

C2 Cargo Ships Minutia

Overall these ships were designed for a 459 feet hull, betwen PP. 435 feet for a beam molded of 63 ft and 40 feet 6 inches tall, draft, loaded of 25 feet 9 inches.

Displacement was 13,812 tons. Gross measurement: 6,228 tons. Deadweight capacity was 8,767 tons and deadweight cargo capacity of 7,137 tons.

Bale capacity was 550,000 cubic feet, for a volume capacity of 77.000 cubic feet.

Block coefficient was 0.687, Longitudinal coefficient: 0.699, and Midship section coefficient of 0.98.

Parallel middle body percentage. 12. 5. G. M. light 9.25′, G. M. loaded 3.13′.

Sustained sea speed at load draft: 15 knots

Designed normal shaft: H.P 6,000

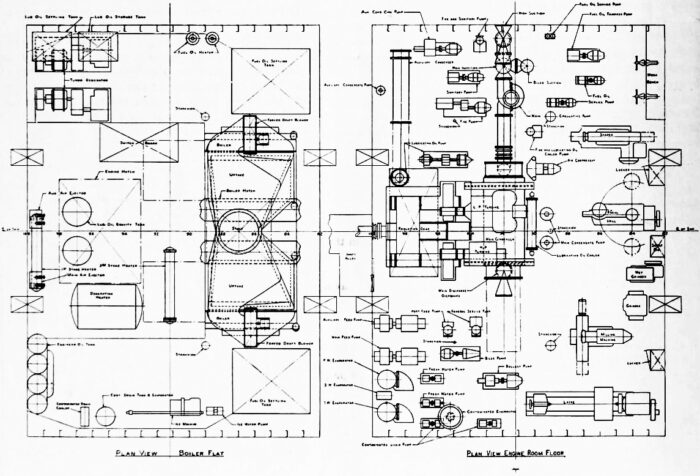

Single screw drive by double-reduction gear cross compound steam turbines.

Two water tube boilers. Steam conditions 450 lbs. 750° F.

Designed propeller revolutions 80. Diameter of propeller 20 feet

Steaming radius at 15 knots: 13,000 miles

Weights: Steel hull 3,704 tons, Wood and outfit 769 tons

Machinery: 660 tons

Passengers, crew, and effects: 10 tons

Stores: 10 tons, Fresh water, potable: 25 tons, Reserve feed water: 259 tons

Fresh water, miscellaneous: 112 tons, Oil fuel 1,214 tons.

Ship ready for sea without cargo: 6,763 tons

Powerplant

Plans of engine room, showing her machinery arrangement.

These vessels came with two boilers feeding steam to two turbines, in turn mater on a single shaft and propeller. Total output was 6,000 shp (4,500 kW) on AF-11 designs or diesel engines

for a top Speed in both cases of 15.5 knots (28.7 km/h) as designed and 19 knots (35 km/h) max for short runs to outpace U-Boats.

Diagrammatic transverse section through machinery spaces

Armament

USS Wayne (APA-54) at NAS Norfolk in 1943, painted in dark navy blue, MS21 sea blue system: Navy Blue 5-N on all vertical surfaces without exception, Deck Blue, 20-B for horizontal surfaces, Deck Blue as well as Canvas Covers.

The ships, when operated by the USN, were given a full panoply:

One single 5 in/38 (127 mm) modern dual-purpose gun mount, not typical of the early models used on escort carriers, four single 3 in (76 mm) dual-purpose gun mounts for AA and anti-surface defence, and ten single 20 mm AA gun mounts (AF-11 design) for AA defence.

5 in/38 Mark 12

Unshielded, located forward in a “bath-tube” like platform built over the bow for maximal ac of fire.

The Mk 12 Gun Assembly weighted 3,990 lb (1,810 kg), mounts c29,260 lb (13,270 kg), for 223.8 in (5.68 m) long. The Barrel measured 190 in (4.83 m) bore, 157.2 in (3.99 m) rifling.

Crew was about 8 men. It used a Vertical sliding-wedge breech, with a recoil of 15 in (38 cm), capable of an elevation from −15° to +85° and a traverse of 328.5 degrees. It fired a 53 lb (24) 127×680mmR HE shell up to 15 rpm, at a muzzle velocity of 2,600 ft/s (790 m/s) initial. The gunner ussed an Optical telescope. Full data.

3 in/50

A classic design initiated in the 1890s, in service for 90 years (1900-1990). Type unknown. Probably the same used on the “AVD” seaplane tender conversions, “APD” high-speed transports, “DM” minelayers, and “DMS” minesweeper conversions.

Mark 21 spec:

1,760 pounds (800 kg), 45–50 rounds per minute with autoloader. AA Mount -10° to +85°.

Rounds: Complete round: 24 lb (11 kg), 13 lb (5.9 kg) AP, AA (with VT proximity fuze), HE, Illumination.

2,700 ft/s (820 m/s), 14,600 yd (13,400 m) range at 43° elevation and 30,400 ft (9,300 m) AA ceiling.

On 7 La Salle-class transports (C2-S-B1), 2 Storm King-class transports (C2-S-AJ1), 8 Mount Hood-class ammunition ships (C2-S-AJ1), 7 Lassen-class ammunition ships there were 4 per ship.

Generally placed in side sponsoned platforms port starboard or paired on the forecastle and sterncastle (aletrnative to a 5-in/38 gun).

20 mm AA

Standard mightweight AA gun ubiquitous in the USN. No need for further presentations. The location was very much dependent on on the ship type. Many had these placed on paired platforms port and starboard for the best arc of fire. Full data.

⚙ C2 Cargo specifications AF-11 |

|

| Displacement | 5,443 DWT, 13,910 tons |

| Dimensions | 459 x 63 x 25 ft (139.90 x 19.20 x 7.62 m) |

| Propulsion | 1 prop. 2 turbines, 2 boilers, 6,000 shp (4,500 kW) |

| Speed | 15.5 knots (28.7 km/h), pushed to 19 knots (35 km/h) short runs |

| Range | 10,000+ nm as standard () |

| Armament | 1× 5 in DP, 4× 3 in DP, 10× 20 mm AA mounts |

| Protection | None: ASW compartimentaton and double hull. |

| Sensors | Likely destroyer type radar in 1944 |

| Crew | 287 on average |

C2 Cargo: A full Description

Some Comments on the Building Program Proposed by the Maritime Commission

A merchant marine is a very complicated fabrication, much of which is composed of invisible and almost imponderable elements that must be built up over a long period and that require constant vigilant nursing to prevent their evaporation and the possible collapse of the entire -structure. The most tangible and, of course, one of the most important elements of a national merchant marine, is the fleet of ships that are its operating tools. When we speak of rebuilding our merchant marine we mean primarily the process which will ultimately furnish that merchant marine with a new set of tools — a new fleet of ships. However, in addition to the ships there are many other elements which are necessary, and many of these must also be rebuilt, so that in any careful analysis of a rebuilding program all these elements must be considered. The single ship, however, will take a year or more to build, so we must consider first getting started on the ships and while the ships are building we must recondition, rebuild, and re-equip all the other elements that should be included in a well designed, properly built merchant marine structure. The principal elements to be drydocked, repaired, reconditioned, scraped, cleaned and painted are:

(1) Legislation. Much of this element, that is now obsolete and outmoded— acting as a growth of weeds or barnacles to slow up progress — should be scrapped and discarded. In its place there should be added a carefully prepared code of law based on the needs of modern transportation services.

(2) Personnel. The American merchant marine needs a complete revision of ideas and conceptions concerning both officer and crew personnel. The officers and crew need an entirely new basis of training and education. Even the operating executives may have to get a new education.

(3) Ports. The great majority of American ports are operating on 19th century ideas in a 20th century world. Perhaps we shall find many handicaps here that can be removed by intelligent concerted action.

(4) Insurance: is an important element in a successful merchant marine. Is our American set-up for marine insurance capable of improvement?

(5) Shoreside Personnel. Can anything be done to improve the efficiency of longshoremen, checkers, tally clerks, passenger and cargo agency personnel so that costs of shoreside operation may be reduced without cutting wages?

(6) Shipping Finance. Working capital is the bone and sinew of modern business. It has been verv wary of American shipping. What must be done to get capital interested?

These and many other questions face us as we enter 1938 determined to “Start Rebuilding our Merchant Marine.” It is our intention to cover all of these matters in a series of articles running through the year. In this first article of the series we are considering the fleet — the ships we need — types, numbers, speeds, equipment.

Rebuilding the US Merchant Fleet

As we write, the special session of Congress is being bombarded with many merchant marine bills, each of which is designed to make possible an early start of the rebuilding program announced by the U. S. Maritime Commission. The largest unit of that program, the 730 foot passenger liner for the United States Lines, is already under construction at the Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company. The Maritime Commission is promising immediate calling for bids on 20 vessels of various types, including 10 of their standard cargo vessel design.

(Before this article got to press bids were called for on 12 vessels on this standard cargo carrier design.)

Along with these promises for the immediate future the large oil companies are steadily ordering replacements for their tanker fleets. The Navy is ordering both fighting and auxiliary craft. Altogether the total gross tonnage now under construction or order in American shipyards and Navy yards is greater than that of any year since 1923. That this work is to be largely increased is certain and that fact should be of great comfort to the American shipbuilding industry, which has had many very lean seasons during the past fifteen years. Some shrewd observers are convinced that the present prospects for American shipbuilding are rosier than at any time in the recent histoty of that industry.

Granting that this is the case, it must be a matter of great concern to the American ship operator in overseas trade that this Government inspired shipbuilding program shall produce vessels that will be, as to their respective types, world leaders in safety, in overall operating economy, in comfort, in dependable schedules, and in service to the shipping and traveling public. The principal reason for this activity in American shipbuilding is not lack of ships but the fact that the great majority of American ships are so old that they have become too deteriorated and too obsolete to be profitable competitors with the newer ships of other nations.

A normal life period for the steel hulls is 20 years. By that time deterioration has progressed to the point where upkeep is beginning to make large inroads on income. Some 85 per cent of our steel steamships in the overseas trade, reaching that point already or will have reached it by 1941-42. Many of these vesels need replacement on this score.

Obsolescence

Obsolescence is another story. A ship, like an automobile or any other manufactured article, may be practically obsolescent before she is launched. Such was the ease with many of our war built cargo carriers of the standardized types. These vessels, designed eight years before the last of them were finished, came into immediate competition with post-war designs and speeds in European vessels. They were therefore not usable or salable here or abroad. Hence many ships during the later period of that shipbuilding effort went directly from the builders’ yards to storage on some mud flat to await a more favorable opportunity, which never came.

Nearly all of the vessels now operated by our principal competitors in overseas trade routes have been designed and built since the war. These ships have incorporated refinements in hull design and technical advances in marine engineer ing, much of which was unknown when America was building her great fleet of cargo vessels. As we see the world’s merchant marine picture today, it would seem foolish for any nation starting to rebuild its merchant fleet to standardize on types, speeds, drives, or sizes for competitive vessels unless they can make their standard equal to or better than the very best afloat of its type.

If we are satisfied to begin a building program with a standard which is any less than the best obtainable we will find ourselves at the end of this shipbuilding effort in much the same position as in 1920. i.e. with a lot of more or less obsolete vessels on our hands.

Maritime Commission Program

The tentative program of replacements for the American merchant fleet as developed by the experts of the Maritime Commission calls for 95 vessels of types and estimated costs as follows:

-46 cargo vessels, 58,880,000t

-14 cargo vessels; 19,040,000t

-10 cargo and passenger vessels, 40.000.000t

-10 cargo and passenger vessels, 55,000,000t

-1 special liner, 15,000,000t

-10 tankers, 28,520,000t

Total 95 C2 type vessels for $256,440,000t

This program was authorized by Congress in August, 1937, as an initial unit of a five year program calling for the building of 225 to 250 vessels at an estimated cost of $520,000,000.

Construction work began on this program in November, 1937, with the formal signing by the Maritime Commission of a contract with the Newport-News Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company for the construction of the special liner item at a cost of $15,750,000 (adjusted price basis). This cost figure is only 5 per cent higher than the estimates made by the Commission.

This vessel, so far as form, speed, machinery, and size are concerned, is the ideal for the majority of the traveling public on the North Atlantic today. We thoroughly agree with the position taken by the Maritime Commission on the matter of super liners of high speeds and monster size. Economically these huge liners are a liability. The same amount of capital and subsidy as would be necessary to maintain a service with two or three such vessels could maintain a fleet of air transports of far greater speed and of equal overall capacity.

As military or naval auxiliaries the huge ships are not nearly so valuable as the medium sized liners. Only a few of the world’s ports can accommodate them, and they cannot pass through the Panama Canal.

However, since the program calls for only one special liner we need not interest ourselves further in the details of her design, since it is not establishing a standard. Mainly of interest in this respect are the 60 cargo vessels in two classes with 14′ ships in one cla^-s and 46 in the other. The estimated cost of these units is $1,360,000 for each of the 14, and $1,280,000 for each of the 46. As we write the Commission has called for bids on 12 of these vessels. We reproduce herewith profile, deck plan, machinery layout and outline midship section of the standard design for these ships as issued by the Maritime Commission, General characteiistics are given in the table herewith.

This design has many excellent points as to form and type. There are, however, several details in which it seems to us the design stops short of being a good standard design for a competitive overseas trade vessel for future successful use. The arrangement of the interior space for both passengers, crew, and cargo will, of course, need to be changed to meet the requirements of the various trades.

From the standpoint of operation in overseas trades out of Pacific Coast ports we would suggest that the deep tanks for fuel oil be moved to forward side of the forward bulkhead of the engine room, and be run from tank top to 2nd deck. To get the same cubic capacity for oil this tank would require a fore and aft length of approximately 22 feet. We would then divide the space between this tank and the forepeak bulkhead into two main cargo holds each 75 feet in length and each with a hatch 20 feet by 35 feet.

We would remove all stanchions in way of hatches, and compensate for this with center line bulkheads between hatches and transverse webs in way of hatch ends. We would carry transverse watertight bulkheads up to shelter deck so that with heavy cargoes we could fill the space and take advantage of greater allowable draft.

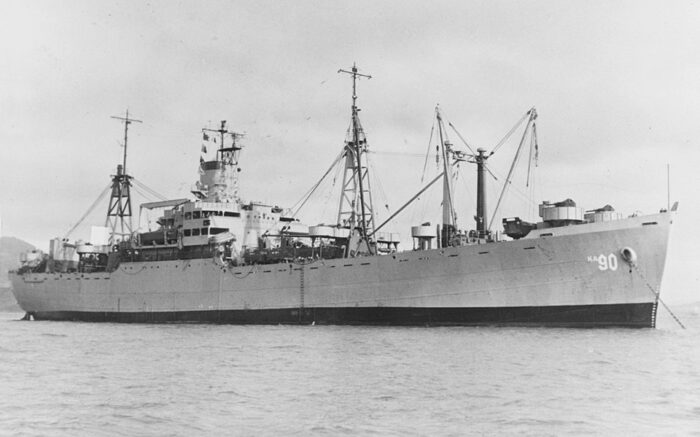

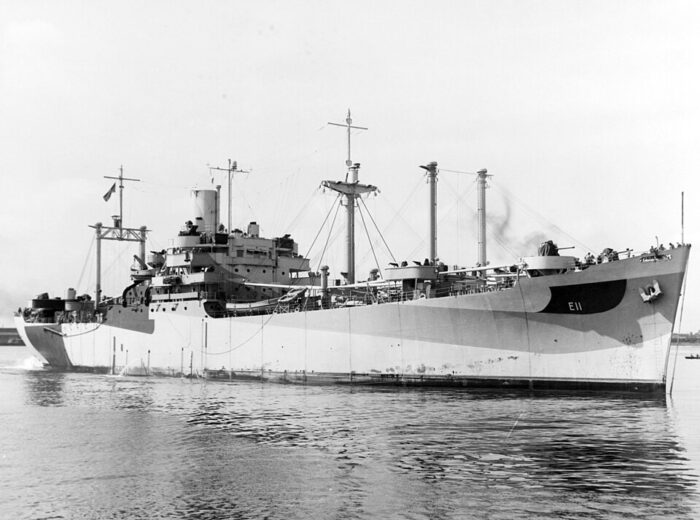

USS Polaris (AF-11) off Korea 1953

Placing the deep tank and spacing the holds and hatches thus would allow an extension of the midship superstructure forward for about 25 feet, thereby permitting larger passenger staterooms and public rooms. We would devote the entire cabin deck to the 12 passengers, place the engineers on the shelter deck level and the crew in the poop.

This arrangement has the advantage of giving the passengers an exclusive space for recreation, for eating, and for sleeping quarters. Such exclusive space is becoming more necessary as the eight hour day rule at sea puts two thirds of the crew off duty all the time. In other words, it is hardly a fair proposition to ask 12 passengers on such a ship to pay good money for board and lodging in a small house where approximately 30 members of the crew are sleeping or loafing all the time.

The passenger accommodations on this cargo vessel as designed could never be sold in competition with ose installed on Scandinavian. Dutch, British, French. German, Italian, or Japanese vessels of similar class and speed.

Crew accommodations in the poop could be made more comfortable and with larger recreation rooms than are provided in the small deck house of the C-2 design. The crew’s mess room and the galley could be arranged on the after end of the amidship house on the shelter deck level.

Design details which we personall, would wish changed if we were building such a vessel for operation anywhere are:

(1) Flat decks. We certainly would put in some camber on the decks of a 60 foot beam hull.

(2) No bilge. We would certainly want bilge drainage at the side of the hold floors.

(3) Propeller speed. With modern designs of propellers considerable deadweight could be saved to advantage by increasing the propeller speed 50 per cent to 120 r.p.m. and decreasing propeller diameter to from 13 to 14 feet. The tip speed of the smaller wheel at the higher revolutions would be a little less than that of the 20 foot wheel at designed speed. The propeller diameter reduction would give more depth of water over the tips. This extra depth of water might give sufficient additional surplus propulsive efficiency to offset the slight reduction due to the increased revolutions.

(4) Bow form. The modified Maier form type of bow offers many advantages in maintaining schedules against head winds.

(5) Rudder. There is much advantage in having a balanced rudder on a vessel of this .-^ize and speed.

(6) Superstructure form. We would certainly give the forward end of the superstructure a much moie pronounced streamline effect.

The first cost of the hull with these proposed changes would be slightly higher. The first cost of the machinery would be somewhat lower. The total overall cost would be a little higher, perhajjs 5 per cent. The resultant ship, however, would be well worth the additional cost as a better competitor in any operator’s trade route.

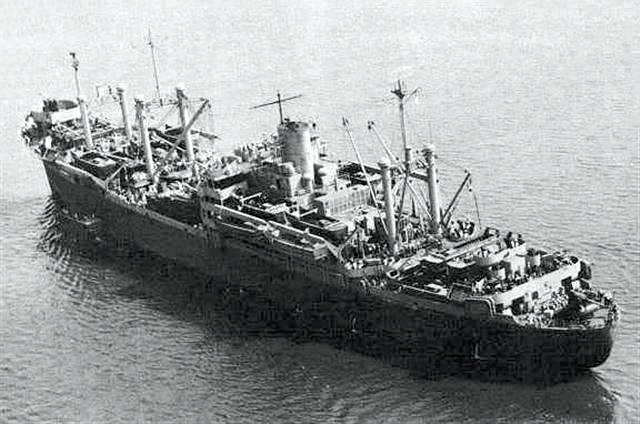

USS Whiteside AKA-90 anchored in San Francisco Bay c1948

Steam pressure is another item of this design on which it may not be wise to standardize at the figure set. American power plant engineering has led the way into higher ranges of steam pressures. Why should American marine engineering be content to stick around 400 pounds? Germany has already gone to 1300 pounds in marine plants with great benefits in space and weight savings and some fractional benefit in fuel consumption.

It is well understood that the principal benefits from the use of higher steam pressures in marine propulsion plants lie in space and weight savings. These savings, however, albeit largely confined to new construction in which the entire vessel is designed to take fullest advantage of their possibilities. Hence the impoitance of going to the higher pi-essure ranges in any proposed program of new standardized construction.

There arc great possibilities inherent in the welding process, by the use of which carefully designed standard assemblies of portions of the ship’s structure may be duplicated in fabrication and riveted or welded into the ship’s hull. Examples are the stem, the stern, the tank structure in way of engine foundations, bulkheads, and any special reinforcing members in way of auxiliary machinery foundations.

We have no desire to hold up the program of building until these or any other changes are made in designs. The majority of the proposals made herein can be handled in the detail work in shipyards with little if any alteration in costs. We simply wish to emphasize the obvious fact that in producing a standard design for vessels which are to be run in competitive trade routes we should look first at the design features necessary for successful competition and build our standard design around those features. Then we should carefully study the standard design to reduce first cost in its building. First cost is important, but it is only one out of several important elements, in the design of a vessel that is to successfully meet the ct)mpetition of the world’s finest merchant ships.

Source: PACIFIC MARINE REVIEW 1938 (src below)

Military Types

Stores Ship – AF types:

3 Aldebaran-class (C2): Aldebaran (AF-10), Polaris (AF-11), Jupiter (AK-43)

2 Hyades-class (C2-S-E1): Hyades (AF-28), Graffias (AF-29)

6 of 10 Alstede-class (C2-S-B1-R): AF-50, AF-51, AF-52, AF-54, AF-60, AF-61

Attack Transports: APA (1 + 6AP)

3 Ormsby-class attack transports (C2-S-B1), APA-49, APA-50, APA-51 (AP-94, AP-95, AP-96)

4 Sumter-class attack transports (C2-S-E1), APA-52, APA-53, APA-54 (AP-97, AP-98, AP-99) APA-94

Transports – AP (13):

7 La Salle-class (C2-S-B1)

3 Tryon-class (C2-S-A1)

2 Storm King-class (C2-S-AJ1)

Cargo ship – AK (21 + 1 AKA)

Arcturus (AK-18) to Electra (AK-21), Alchiba (AK-23) to Alhena (AK-26), Betelgeuse (AK-28), Mercury (AK-42), Jupiter (AK-43), Libra (AK-53) to Oberon (AK-56), Andromeda (AK-64) to Virgo (AK-69), Wyandot (AK-283) (AKA-92 1963).

Attack Cargo Ships – AKA (60 + 17AK):

USS Alhena (AKA-9/AK-26)

11 Arcturus-class:(C2, C2-F, C2-T):

AKA-1 to AKA-4 (AK-18 to AK-21), AKA-6 to AKA-8 (AK-23 to AK-25), AKA-11 to AKA-14 (AK-28, AK-53, AK-55, AK-56).

32 Tolland-class (C2-S-AJ3):

AKA-64 to AKA-87, AKA-101 to 108

30 Andromeda-class (C2-S-B1):

AKA-15 to AKA-20 (prev: AK-64 to AK-69), AKA-53 to AKA-63, AKA-88 to AKA-100

General Stores Issue Ship – AKS (2 + 2AK)

3 Castor-class general stores issue ships: USS Castor (AKS-1), Pollux (AKS-2), Pollux ii (AKS-4/AK-54), Mercury (AKS-20)/AK-42)

Ammunition ship – AE (15 + 2AKA):

USS Mount Hood ammo transport, lead ship (AE-11) at Norfolk NS 16 July 1944.

7 Lassen-class (C2, C2-T, C2-N): USS Lassen (AE-3), Kilauea, Rainier, Shasta (AE-6), Mauna Loa (AE-8), Mazama (AE-9), Akutan (AE-13)

8 Mount Hood-class (C2-S-AJ1)

Converted from Andromeda-class in 1965: Virgo (AE-30) (prev: Virgo (AKA-20)), Chara (AE-31) (prev: Chara (AKA-58))

Aviation Supply Ship – AVS (1AK)

Jupiter (AVS-8) (AK-43)

Command ship – AGC (15)

4 Appalachian-class: Appalachian (AGC-1), Rocky Mount (AGC-3), Catoctin (AGC-5)

8 Mount McKinley-class: Mount McKinley (AGC-7) to USS Teton (AGC-14)

3 Adirondack-class: Adirondack (AGC-15), Taconic (AGC-17)

C2 Cargo subtypes

C2-S-B1

C2-S-B1

USNS Bald Eagle

115 ships built in all. 9,150 tons. Built at Federal SB, NJ Moore DD, CA, Consolidated, CA and Western Pipe & Steel, CA.

USNS Bald Eagle was used sucessively by agents of the War Shipping Administration (WSA) in 1943—1948, operated by the U.S. Army in 1948—1950 and the Military Sea Transportation Service from 1950 to 1970. She was built at the Moore Dry Dock Company, Oakland, California, delivered to the WSA on 28 May 1943, pennant 243368. Until 9 September 1946 she was operated on Atlantic lines, and postwar by the Pacific Far East Lines under bareboat charter until 2 May 1947. She had other operators and ended in the Reserve Fleet 30 July 1948. On 4 October she became an U.S Army under bareboat charter as Army transport. but with a reorganization of the DoD, transferred to the Military Sea Transportation Service, transferred on 1 March 1950 as an MSTS refrigerated cargo ship, T-AF-50. She had then a crew of 55, capacity of 323,309 cu ft (9,155.1 m3) of chill/freeze cargo, and operated between the east coast and northern Europe.

On 16 July 1970 Bald Eagle was retired, transferred to Maritime Commission custody and on 1 March 1973 sold for BU to Andy International, Inc. for $75,666.66.

C2-S-AJ1

C2-S-AJ1

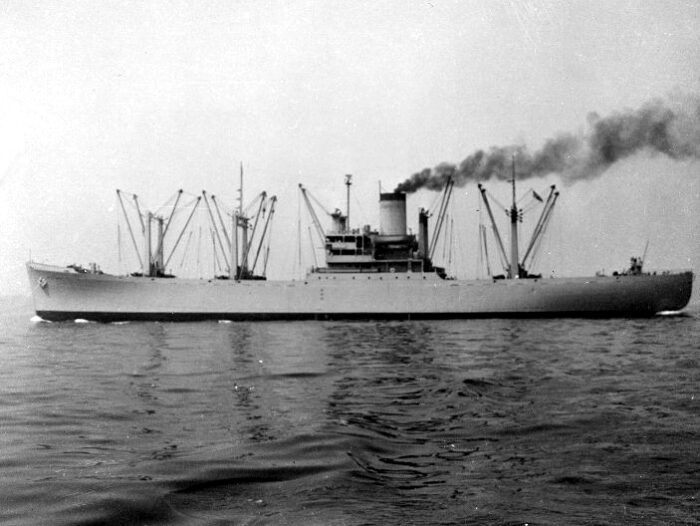

USS Adirondack

In all, 64 ships of this type were built at North Carolina SB, NC., tonnage 10,755t.

USS Adirondack is a solid example of a ship which stayed with the USN until 1955 but in a different role as the photo above, a command ship. Laid down on 18 November 1944 she was launched on 13 January 1945 and commissioned on 2 September 1945, built at Wilmington, NC. She was well armed, with two main 5-in/38 guns, 3×2 40 mm Bofors and 6 20mm Oerlikon AA.

But she was oin service the very day Japan surrendered on board USS Missouri (BB-63) in Tokyo Bay. Initially designed as an amphibious force flagship or floating command post with advanced communications equipment, extensive combat information spaces for a landing force commander she was well fitted still and valuable for potential futture amphibious ops. After shakedown training in the Chesapeake Bay until 12 October she became flagship, Commander, Operational Development Force (CTF 69) off Norfolk until August 1949 and sent to Philadelphia for inactivation, reserve from February 1950, but as flagship Philadelphia Group, Atlantic Reserve Fleet. She was recommissioned on 4 April 1951 as the Korean war flared up and required her services, she served a time for the Atlantic Fleet Training Command in Norfolk and in refit by 3 June to take command in the Mediterranean as flagship for CINCSOUTH and CINCNELM.

By May 1953, she sailed for Norfolk for overhaul and reassignment. She became flagship, Amphibious Force, Atlantic Fleet, made a Caribbean tour and stopped at San Juan on 23 March to host COMPHIBGRU FOUR and taking part in Operation “Sentry Box” off Vieques, then LANTAGLEX-54, “Packard V” in May, then Operation Keystone, with conferences held in Naples and carring international observers with observers. She had a refit at Norfolk on 27 September, took part in Operation “NORAMEX”, “ANGEX II”, “TRAEX 11-55” until bacl at Norfolk for inactivation, in reserve from 9 November 1955, stricken 1 June 1961, sold for BU 7 November 1972.

C2-S-AJ3

C2-S-AJ3

Of this class, 32 ships of 11,300t were built at North Carolina Shipbuilding Co in Wilmington.

USS Tolland was laid down on 22 April 1944, launched on 26 June 1944 and commissioned on 4 September 1944. Named The Mighty “T” she was awarded 2 battle stars for her service in World War II: Assigned to Task Group 29.7, she left Hampton Roads on 14 October for Hawaii via the Panama Canal on 21 October, to Pearl Harbor on 5 November, took part in amphibious maneuvers off Maui, returned to the West Coast on 6 December to take cargo and back to Pearl Harbor on 23 December added to more training notably to load and unload cargo at great speeds in January 1945, but also AA drills until she departed with Task Force 53 on 27 January for Eniwetok, with marines of the 5th Marine Division and a Seabee unit. Via Eniwetok and Saipan, sge arrived off Iwo Jima on 19 February for ten days of unloading despite heavy weather and rough tidal conditions: 3 LCVP and 1 LCM sank, but all men made it to shore. One unmanned amphibious craft struck her propeller, one shell destroyed her radio antenna and later care for 25 marines, wounded on shore. Tolland and other AKA’s left the Bonins and after R&R prepared for Okinawa. Drydocked at Espiritu Santo she was combat-loaded to carry the 27th Division, leaving the New Hebrides on 1 April 1945 for the Ryūkyūs. She arrived on 9 April, anchored as a floating reserve with Task Force 53 with her AA crews hard at work through many massive air attacks, in general quarters many long hours night and day as 22 air attacks deployed over 8 days. She claimed a “Betty” on 12 April, an “Oscar” on 15 April (shared). She left later via Saipan to Ulithi for R&R, exercises and drills until 14 May, returned to Angaur (Palau Islands) to load heavy guns and setn to the Philippines, off-loading cargo at Cebu on 24 May, moved to Subic Bay for upkeep, then Manila 22-28 June and to Leyte to embark troops, vehicles, and equipment of the 323d Division for amphibious training in preparations for the invasion of Japan. While in Lingayen, word of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and later of the capitulation was heard of 15 August. She was sent to Batangas Bay, Luzon, then to Tokyo, present for the capitulation signing on USS Missouri. After a halt at Zamboanga on 2 September where she embarked the 41st Division to Kure for occupation duty she returne to Manila, embarked elements the Chinese 52nd Army at Tonkin Gulf to retake French Indochina, then Chinwangtao. On 14 November she left Taku for Seattle (20 November) and TU 78.19.6 remained in the Pacific northwest until 28 February 1946, she then departed for Fort Hueneme and on 11 March loaded cargo for Guam, Apra Harbor on 27 March to 20 April and headed for Panama, Balboa on 13 May, reporting to CiC Atlantic Fleet on 14 May via Hampton Roads to Norfolk on the 21th, decommissioned on 1 July, returned to the War Shipping Administration, struck 19 July, sold and acquired by the Luckenbach Steamship Co. as SS Edgar F. Luckenbach in October 1947 until 1959 then the States Marine Line as SS Blue Grass State, sold 6 November 1970, SS Reliance Cordiality (Panamanian), sold for BU at Kaohsiung in 1971.

C2-S-E1

C2-S-E1

The Sumter-class sister ships USS Warren

30 ships, 10,565t, Built at Gulf SB, AL. Sumter-class attack transport (4 sister ships). USS Wayne was originally laid down as MC hull 476, yard hull 7 (251508) on 20 April 1942 as “Afoundria” in Chickasaw, Alabama, at the Gulf Shipbuilding Corporation. Renamed SS Wayne she was reclassified as the transport AP-99 on 26 October 1942, launched on 6 December 1942, then attack transport APA-54 on 1 February 1943, under USN 30 April 1943 as USS Wayne and completed, commissioned on 1 May 1943 “in ordinary.” Converted for military service at Key Highway Yard, Baltimore, from 11 May 1943 as APA-54 to 27 August 1943. USS Wayne took part in nearly all major amphibious operations of the Pacific war and was thus awarded 7 battle stars. Her case was not isolated, but shared with most assault transports of the 1942-43 series. She was well armed, with two main guns (5-in), four twin, 40 mm and ten single 20 mm AA but was initially given two quad 1.1/75 mm “Chicago Piano” due to bottlenecks. Here is an abbreviated summary of her career.

She left Baltimore on 1 September for Norfolk, taking fuel, stores, equipment and landing craft, made her shakedown in Chesapeake Bay, Hampton Roads in October, New York to complete loading and departed on 13 October, escorted by USS Doran (DD-634) and USS Canfield (DE-262) for the Pacific via Panama, San Diego, remaining there until November for training with the 4th Marine Division and departing on 13 January 1944 with the 3rd Battalion, 24th Marines for Maui, Hawaii, fueled from USS Tallulah (AO-50) and supplied from USS Pastores (AF-16) before heading for the Marshall Islands. Long story short she took part in the Invasion of Kwajalein in April, Invasion of Saipan in June, Invasion of Peleliu in August (fired upon by coastal batteries in the night of 20 September), Invasion of Leyte in Ocrober (Aircraft kill on the 14th), Invasion of Luzon in January 1945, shooting down a “Frances”, Invasion of Okinawa in March, in R&R at Kerama Retto in early April in assistance to the crippled USS Hinsdale (APA-120) and back to Hawaii on 27 April.

San Francisco in May, having an overhaul at Astoria, Oregon in May, San Diego in July, and learning about the end of the war while underway in August back to the Pacific. She left Eniwetok on 26 August to Guam, unloading cargo and passengers, embarked the 3d Battalion, 6th Marines at Saipan and sailed to Japan for occupation duties on 18 September, landed on 23 September, then sailed to Manila to pickup up personnel to repatriated, and headed for home via Guam in October to refuel, reached San Diego on 6 November, making another such trip from 21 November 1945 to 7 January 1946 in Operation Magic Carpet. Later via New Orlean she headed to Mobil and the Gulf Shipbuilding Corp. to be decommissioned on 16 March 1946, stricken on 17 April 1946, transferred to the War Shipping Administration. Resoldf to a Civilian company afetr conversion, Scrapped, May 1977.

C2

C2

Twenty ships built (9,758t) at Federal SB, Sun Yards, PA, Newport News, VAn Tampa SB 9,758t. USS Polaris (photo) was a standard “liberty ship” of the C2 type, Laid down on 23 July 1938 at Sun Shipbuilding in Chester as SS Donald McKay, Launched on 22 April 1939 and acquired for military conversion by the USN on 27 January 1941, completed and commissioned on 4 April 1941. As completed as military transport, she had a single 5 in/38 (127 mm) forward, four single 3 in DP gun mounts and ten single 20 mm AA gun mounts.

Twenty ships built (9,758t) at Federal SB, Sun Yards, PA, Newport News, VAn Tampa SB 9,758t. USS Polaris (photo) was a standard “liberty ship” of the C2 type, Laid down on 23 July 1938 at Sun Shipbuilding in Chester as SS Donald McKay, Launched on 22 April 1939 and acquired for military conversion by the USN on 27 January 1941, completed and commissioned on 4 April 1941. As completed as military transport, she had a single 5 in/38 (127 mm) forward, four single 3 in DP gun mounts and ten single 20 mm AA gun mounts.

USS Polaris made five trips from the U.S. East Coast to Reykjavík in Iceland (June 1942 to February 1943) and five to Port of Spain, Trinidad, San Juan, Puerto Rico, from March to July 1943 then from October 1943 to February 1944, four more at Guantanamo Bay and Hamilton in Bermuda, Virgin Islands and San Juan, then in March-September 1944, three convoy trips to Oran, Algeria and Mediterranean ports. On 10 November 1944 she departed New York for the Panama via Colón to the Pacific, Eniwetok, Saipan, Tinian, Apra and Seattle 9 January 1945. Pearl Harbor, Eniwetok, Ulithi. Los Angeles, Ryukyus, Tokashiki Island, San Francisco in August. She was decommissioned on 18 January 1946, stricken 7 February 1946, transferred to the Maritime Commission on 30 June, but reactivated in the same role during the Korean War in Service Squadron 1 (six trips to Korean waters 29 January 1951-23 July 1954). She held the record as par tof the Aldebaran-class provisions store ship for the provisions transferred per hour while on underway replenishment: 116.10 tons to USS Midway on 29 April 1955. Stricken on 10 October 1957, transferred to the Maritime Administration. 1970: National Defense Reserve Fleet Suisun Bay, BU.

C2-S-AJ5

C2-S-AJ5

10 ships. Tonnage 10,400t. Built in North Carolina. Best example: SS American Scout.

C2-F

C2-F

7 ships. 9,390t, built at Federal SB. Best example: USS Oberon (photo). She was part of the Arcturus-class attack cargo ship and had a very active career in WW2, taking part in most operations. She was started in 1941 at Federal Shipbuilding and Drydock Company, Kearny, New Jersey as SS Delalba, Launched on 18 March 1942, acquired by the USN on 15 June 1942, converted and commissioned on 15 June 1942, as USS Oberon (AK-56). She was armed with a single 5″/38 caliber gun mount forward, four single 40 mm gun mounts and 18 single 20 mm gun mounts. She became one of the most decorated USN transport (11 battle stars, 6 for WW2, 5 for Korea). She was part of Operation Torch on 24 October 1942, starting operations on 8 November, at Fedhala, French Morocco. On 24 November she departed for the Pacific via Panama Canal as AKA–14, reached New Caledonia, New Hebrides and back to Norfolk, on 12 March 1943. Back in the Mediterranean in July she was off Gela for the landings on Sicily, and Salerno, then on the Oran-Bizerte supply run and later at Belfast, damaged by an Atlantic storm, repairs at Philadelphia and back to North Africa in April via Cardiff, part of Assault Group II for the Operation Anvil on 15 at St. Tropez, then runs Oran-Naples, and back home in October, reassigned to the Pacific, sent to Leyte, arriving on 21 February 1945, with Amphibious Group 7, Kerama Retto in March and the battle of Okinawa on 1 April (shot a kamikaze). From 26 April, South Pacific, learning about V day underway to the Philippines. Occupation troops to northern Honshū, 25 September. Yokohama, then back to Seattle in November. Used postwar by the Navy Transportation Service to bases in the Pacific. Then Military Sea Transportation Service from October 1949, ammunition replenishment vessel in the Korean War operating from Sasebo and between Sasebo and Wonsan, two tours of duty. decommissioned on 27 June 1955, reserve until struck 1 July 1960, transferred to the Maritime Commission, National Defense Reserve Fleet, LKA-14 1 January 1969, sold for scrap 3 December 1970.

7 ships. 9,390t, built at Federal SB. Best example: USS Oberon (photo). She was part of the Arcturus-class attack cargo ship and had a very active career in WW2, taking part in most operations. She was started in 1941 at Federal Shipbuilding and Drydock Company, Kearny, New Jersey as SS Delalba, Launched on 18 March 1942, acquired by the USN on 15 June 1942, converted and commissioned on 15 June 1942, as USS Oberon (AK-56). She was armed with a single 5″/38 caliber gun mount forward, four single 40 mm gun mounts and 18 single 20 mm gun mounts. She became one of the most decorated USN transport (11 battle stars, 6 for WW2, 5 for Korea). She was part of Operation Torch on 24 October 1942, starting operations on 8 November, at Fedhala, French Morocco. On 24 November she departed for the Pacific via Panama Canal as AKA–14, reached New Caledonia, New Hebrides and back to Norfolk, on 12 March 1943. Back in the Mediterranean in July she was off Gela for the landings on Sicily, and Salerno, then on the Oran-Bizerte supply run and later at Belfast, damaged by an Atlantic storm, repairs at Philadelphia and back to North Africa in April via Cardiff, part of Assault Group II for the Operation Anvil on 15 at St. Tropez, then runs Oran-Naples, and back home in October, reassigned to the Pacific, sent to Leyte, arriving on 21 February 1945, with Amphibious Group 7, Kerama Retto in March and the battle of Okinawa on 1 April (shot a kamikaze). From 26 April, South Pacific, learning about V day underway to the Philippines. Occupation troops to northern Honshū, 25 September. Yokohama, then back to Seattle in November. Used postwar by the Navy Transportation Service to bases in the Pacific. Then Military Sea Transportation Service from October 1949, ammunition replenishment vessel in the Korean War operating from Sasebo and between Sasebo and Wonsan, two tours of duty. decommissioned on 27 June 1955, reserve until struck 1 July 1960, transferred to the Maritime Commission, National Defense Reserve Fleet, LKA-14 1 January 1969, sold for scrap 3 December 1970.

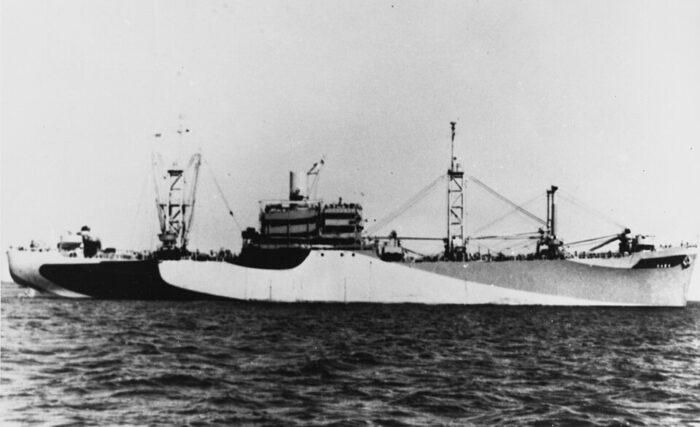

C2-S

C2-S

6 ships, 9,970t. Built at Bethlehem Sparrows Point, MD. Best Example: USS Alhena (photo). A 6 battle stars recipient, she was laid down on 19 June 1940, launched on 18 January 1941, acquired on 31 May 1941 and commissioned on 15 June 1941. Originally she was ordered as SS Robin Kettering, 3rd of three geared turbine, mod. C2-S types for the Robin Line, by Bethlehem Shipbuilding Corp. at Sparrows Point Shipyard, Maryland. She was peculiar with her increased length to the C3 type, no bow or stern sheer, flat, broad funnel. Her bale capacity was 593,655 cubic feet (16,810.4 m3), grain capacity 659,215 cubic feet (18,666.9 m3) or 11,530 cubic feet (326 m3) of refrigerated cargo, 3,485 cubic feet (98.7 m3) “special cargo” space, in five holds. Range was 18,500 nm (34,300 km), crew 43, +12 passengers and 16x 5-ton derricks, a 10-ton derrick, a 30-ton derrick. After purchase by the Navy she was armed with just a single 5″/38 caliber gun mount.

Her service records comprised shakedown training off the East Coast, Boston, Brooklyn, ferried cargo by mid-January 1942, then embarked troops on 5 February for Europe for the Naval Transportation Service, Halifax, Belfast, Clydebank and back to New York. She crossed the Canal and headed for the Tonga Islands, Tongatapu on 9 May to landed Army and Navy personnel, back to San Diego on 5 June. She then took part in the Solomon Islands campaign via the Fiji Islands with TG 62.1 to Guadalcanal on 7 August, Espiritu Santo, Tulagi and Espiritu Santo and had several supply runs between Espiritu Santo and Efate with a stop at Guadalcanal and a 4 killed and 20 wounded+25 marines in a sub attack on the 29th by I-4 (n°5 hold hit by a torpedo). She was assisted by USS Monssen (DD-436), taken in tow, then the tug Navajo (AT-64) to Espiritu Santo on the 7th, then New Caledonia, Noumea, then Australia, Sydney on 20 November and repaired until June 1943, reconverted to an attack cargo ship (AKA-9). She headed back to Nouméa with runs to Guadalcanal and Auckland, taking part in the Bougainville operation, Empress Agusta Bay, then between Nouméa and Guadalcanal before heading back to Hawaii. Nexst she took part in the assault on Saipan with the 2nd Marine Division via Eniwetok. She was later in overhaul at San Francisco and was present when Mount Hood (AE-11) exploded in Seeadler Harbor in Manus (Admiralty Islands) on 10 November 1944. She had 3 crew members killed, 70 wounded, 25 seriously. She needed 6 weeks repair work. Later at Ulithi she took the 3rd Marine Division. Next with TU 51.1.4 she landed troop on the eastern beaches of Iwo Jima on 27 February 1945 (3d Marine Regiment 3d Marine Division). Next she returned to the Volcano Islands and Nouméa and prepared for the Okinawa invasion, by late May, to Leyte and operating between Manila and New Guinea. On 13 October she was in Tokyo Bay and operated in support of occupation forces through 19 November, departed Yokosuka for Seattle, then San Francisco, Christmas holidays, Okinawa, Tsingtao, San Francisco on 18 March 1946 and the east coast, Norfolk, New York City to be decommissioned on 22 May, struck 15 August, transferred 12 September and resold as Robin Kettering (1946 – 1957) and Flying Hawk (1957 – 1971).

C2-S-B1-R

C2-S-B1-R

The sub-class comprised 6 ships, 7,640t. Built at Moore Dry Dock. No example.

C2-S-AJ4

C2-S-AJ4

6 ships, 9,652t. Built at North Carolina (Santa ships). On example: SS Santa Luisa. Three more of the C2-S-DG1-Type were identical, all for the Grace Line service. They had four pole masts, extend passenger capacity. Santa Luisa was ordered in January 1945, laid down at North Carolina Shipbuildung Co. Wilmington on 13.11.45, launched on 02.04.46 and completed on 17.09.46 and never was part if the USN. She served with the Grace Lines up to 19.05.69, sold as Luisa to Central Gulf SS Corp. and scrapped in 1970.

C2-S-AJ2

C2-S-AJ2

5 ships, 10,350t. Built at North Carolina Yard. Example: USS Southampton was laid down on 26 May 1944, launched on 28 July 1944 and commissioned on 16 September 1944. In USN service she was armed with a single 5″/38, four twin 40 mm guns and sixteen single 20 mm AA gun mounts as a Tolland-class attack cargo ship, AKA-66. After shakedown she headed for the Hawaiian Islands and left Pearl Harbor on 27 January 1945 with the 25th Regiment, 4th Marine Division via Eniwetok to Saipa, trained off Tinian and reached Okinawa. In this campaign she earned 2 battle stars, her only incident was when a mortar shell exploded close aboard one of her LCVP’s, wounding the coxswain and a seaman. Sje took part in occupation duties in late 1945-erarly 1946, was sold later as SS Flying Clipper, until sold for scrap on 29 July 1971 to Taiwan.

C2-SU-R

C2-SU-R

5 ships, 8,595t, built at Sun Yards, PA. Ex. MS Stag Hound was launched on 18 October 1941 and completed on September 1942. She was armed with a single 5 in/38 one 3 in/50 and six 20 mm AA guns. Her career was short: She left NYC on 28 February 1943, for Rio de Janeiro and at 19:15 on 3 March, she was hit and sank by the Italian submarine Barbarigo with two torpedoes. Barbarigo operated from Bordeaux (Betasom). 10 officers, 49 men, 25 Naval Armed Guardsmen made it into lifeboats and a life raft, rescued by the Argentinian steamship Rio Colorado.

C2-T

C2-T

4 ships, 8,656t. Built at Tampa SB, FL. Example: USS Shasta. She was laid down on 12 August 1940, launched on 9 July 1941, acquired on 16 April 1941, Commissioned on 20 January 1942 after conversion as a Lassen-class ammunition ship, armed with a single 5 in/38, four single 3 in/50, two twin 40 mm, eight twin 20 mm guns. She was deployed to Adak, in support of the Attu and Kiska operations, then against the Gilberts, the Marianas, the Palaus, Philippines. In Feb. 1945 she made her first successful underway replenishment of ammunition. While doing this off Iwo Jima, she was targeted by shore batteries. On 5 June she was hit by a typhoon southeastern of Okinawa and later survived an attack by kamikaze attack at Ulithi, drifting mines at Okinawa.

In Leyte Gulf she joined TG 30.8 on 17 July 1945 and headed to Puget Sound via Eniwetok, decommissioned at San Diego on 10 August 1946. After the Pacific Reserve Fleet she was recommissioned on 15 July 1953, Atlantic Service Fleet at Norfolk for a modernization overhaul and Mediterranean deployments for eleven years with the 6th Fleet, notably during the Jordanian crisis of May 1957, Lebanese crisis of August 1958. In 1966 she was part of the Vietnam war, in duty at Yankee Station, and back home took part in the search for USS Scorpion (SSN-589). Stricken 1 July 1969, she was dold for BU on 24 March 1970 to a spanish company.

C2-S-A1

C2-S-A1

4 ships, 8,130t. Built at Bath Iron Works, ME. Example: SS Empire Oriole was Completed in October 1941 as “Extavia” for American Export Lines Inc. intended for the Spanish, North African and Black Sea trade. She was shorter than the basic design at 420 ft (128 m) to navigate rivers to inland ports. To MoWT in 1941, renamed Empire Oriole in British service, then USMC in 1942 renamed Extavia, converted to a transport ship by Todd Shipyards in Brooklyn, completed in November 1943. No partciular event. To American Export Lines in February 1946. Scrapped July 1968 in Alicante.

C2-SU

C2-SU

3 ships, 9,620t, built at Sun Yards, PA.

C2-S1-B1

C2-S1-B1

3 ships, 7,640t. Built at Moore Dry Dock

C2-S1-DG2

C2-S1-DG2

3 ships, 8,720t. Built at Federal SB, all cargo-passenger ship: SS Santa Monica, SS Santa Clara and SS Santa Sofia.

C2-N

C2-N

3 ships, 6,350t. Tampa SB: USS Akutan, USS Mauna Loa and USS Mazama. Example here: USS Akutan. She was laid down on 20 June 1944, launched on 17 September 1944 and commissioned on 15 February 1945. When converted for the USN she became a Lassen class ammo ship armed with one 5 in/38, four single 3 in/50, two twin 40 mm, eight twin 20 mm. She proceeded to Ulithi, Caroline Islands for her first mission on 11 May 1945 with Service Squadron 10, Pacific Fleet and with Task Group (TG) 50.8 at the Okinawa campaign. Back to Ulithi on 22 June after weathering a typhoon and headed for Leyte, with Service Squadron 8 until mid-August and left with TG 30.8 to replenish ammunition for the 3d Fleet. On 28 October she left for the east coast via Eniwetok and Pearl Harbor, decom. in Norfolk in December 1945 (2 battle stars). In reserve. She was struck fon 1 July 1960, fate unknown.

C2-G

C2-G

2 ships, 9,020t. Built at Federal SB: SS Santa Elisa and SS Santa Rita (both torpedoed in 1942). The first was launched on 29 May 1941 and completed on July 1941, armed with just a few 20 mm AA guns indirectly for USN service, as she operated by the Grace Line, as part of Convoy WS 21S from Newport for Malta, taking part in Operation Pedestal. She straggled from the convoy, and was attacked and torpedoed by the Italian motor boats MAS 557 and 564, 25 nm (46 km) southeast of Cape Bon in Tunisia, on 12/13 August 1942. MAS 557 strafed her with AA fire and killed her British army gunners, allowing the secnd to close in and launch a 450 mm torpedo that struck her starboard near the No. 1 cargo hatch at 05:17. Filled with aviation gasoline she burst into flames and sank at 07:17 on 13 August with 28 survivors. Some members were awarded DSMs for “heroism above and beyond the call of duty”. Her sister was sunk by U-172 of South Carolina on 9 July 1942.

Read More/Src

SS American Forester in Hamburg, 1969. Many soldiered on well into the late 1970s.

Career Events

Wartime losses were few:

SS Santa Elisa was torpedoed in 1942 and sank off Tunisia, SS Santa Rita torpedoed in 1942 in the North Atlantic. SS Louise Lykes was torpedoed and sank the same in 1943. SS Shooting Star sank in South Atlantic in 1943, SS Fairport North Atlantic 1942, SS Santa Catalina sank off Georgia 1943, SS African Star South Atlantic 1942. One was badly damaged and written off, SS African Dawn (CH-111) which collided with a tanker in convoy, at 23:00 hrs, on octber, 28, 1943. As for the USN, USS Pollux was wrecked and sank off Newfoundland in 1942, USS Mount Hood famously exploded and sank in Manus FOB, Admiralty Islands, in 1944.

Postwar losses:

Highflier(C2-S-B) exploded and sank in 1947. Wild Rover (C2-S-B1), while renamed Mormackite, capsized in heavy seas, sank off Cape Henry, 7 October 1954 with survivorse attacked by sharks.

USS Starlight (C2-S-AJ1) was another famous case. She departed home on 26 December 1969 with a full load of 8,900 bombs, rockets, shells and mines bound for Da Nang, South Vietnam. In rough weather, her cargo, loosly secured, started to shift and bomb dropped and detonated. She exploded and broke in two on 5 January 1970 north of Midway Atoll. 29 died during the evacuation.

USS Towner (C2-S-AJ3) now SS Guam Bear, was wrecked in 1967 after a collision outside Apra Harbor, Guam, resulting in a constructive total loss, hulk was towed just 2 nautical miles (3.7 km; 2.3 mi) off shore and scuttled.

SS American Shipper (C2-S-AJ5), delivered December 1945, sank in 1974 in the Balintang Channel, 400 miles (640 km) southeast of Hong Kong due to typhoon.

Books

Lane, Frederic C. (21 September 2001). Ships for Victory: A History of Shipbuilding under the U.S. Maritime Commission in World War II. JHU Press.

Sawyer, L. A. & Mitchell, W. H. (1981). From America to United States: The History of the long-range Merchant Shipbuilding Programme. World Ship Society.

Links

Bath Iron Works Well Ahead of Schedule

on shipbuildinghistory.com c2 list

archive.org/ pacific marinerev PLANS

maritime.dot.gov/ ss american scout

usmm.org badger_state

shipspotting.com

on shipcamouflage.com MS21

archive.ph/ shipbuildinghistory.com

on books.google.fr/

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign