The cheap answer to British ASW warfare

The Flower class corvettes were a serie of anti-submarine corvettes, specialized in this work in all weather conditions and particular in that they were all built in civilian, and not military years. British frigates like the 139 River class built in WW2, were military-grade vessels, faster and better suited for a large panels of missions. But the Flower class were strickly limited to submarine-hunting and nothing else. They were strongly built and seaworthy, but slow, unarmoured, without redundancy, poorly armed for surface engagements and against AA threats. But between huff-duff, sonar, and a large provision of depth charges, they became adept U-Boat hunters, sinking a large part of Dönitz force during the battle of the Atlantic from 1941 to 1944.

⚠ Note: In this post i will not detail, for obvious reasons of space and interest, the career of each and every of these corvettes. Rather i would keep it at the level of statistics. I leave that for future dedicated articles on the British and Canadian Flower class as well as the Castle class.

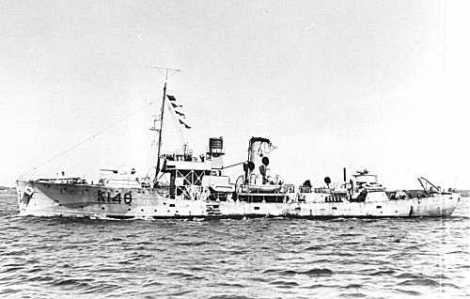

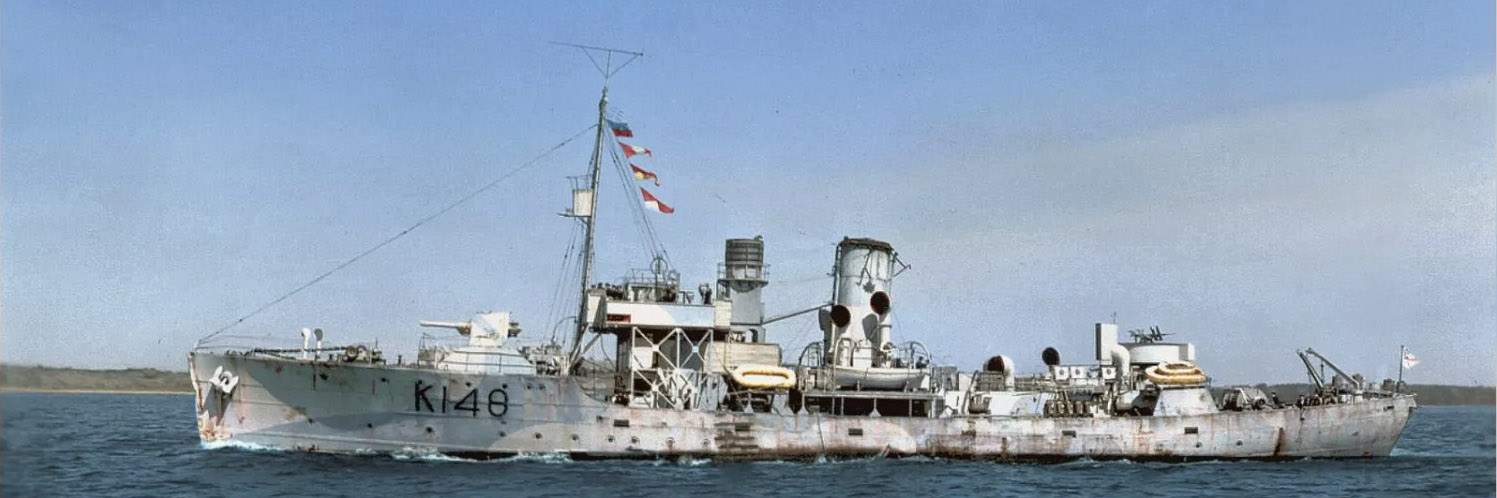

Irootoko Jr. colorized photo of HCMS Amherst

Historically significant for the contribition they made to the ultimate allied victory in WW2, they were cheap and relatively simple vessels inspired by a rugged whaler design, and could free already overtaxed Naval Yards in Great Britain and the Commonwealth. In addition to the 143 built in British Yards, 68 were delivered by Canada for its own needs, and 52 “improved Flower” in 1942, including 42 by Canada, whereas the larger, more military Castle class was developed in 1943. Together with the 46 Castle, no less than 309 ASW corvettes (less those sunk in action) took part in many escort convoys in the Atlantic.

Genesis: The Whaler choice

Smith’s docks Southern Pride, the civilian whaler which formed the basis for the Flower design in 1939

The idea behind the Flower class was not invented in WW2. In fact, if the design was ready in such short period in early 1940, this was due to a simple decision of the Admiralty when war broke out to resurrect old concepts, as a new battle of the atlantic seemed a real possibility. Two in fact. The forgotten “Z-Whaler” class (1915) for a start. There was actually a flower class in WW1 which were sloops, built by civilian yards also, quite a success, but a bit large for their intended role.

The Z-Whalers on the other hand were at first designed at a request of the Russian Imperial Navy. They were 15 inocuous-looking whalecatchers, with better manoeuvrability, a reinforced bow to ram surface U-Boats, stiffened to replace their harpoon gun by a 12-pdr 18CWT (76 mm) gun, all built by order on 15 March 1915 to Smith’s Docks, Middlesborough. They would never be delivered to Russian but instead were stationed in Stornoway in the Shetlands. Their seaworthiness was a disappointment however and trawlers were preferred, notably the “Kil” class and P-Boats.

So in late 1938 discussions in the admiralty on the topic led to study a fusion of the two: A larger whaler type to be built en masse by Civilian Yards. The rest was merely searching for the right whaler type and model to be copied and improved upon for the Navy needs. In January 1939 Mr. William Reed OBE of Smith’s Docks Co. in Middlesbrough was approached by the British Admiralty with a design request of a cheap, simple multi-role warship to be built in small civilian shipyards stranger to naval standards.

Smith Docks was highly regarded due to its past experience of the Z-class whaler we just saw, and its reputation in the civilian market for very sturdy and efficient whale-catchers. The design suggestion was based on a larger version of the 700-ton, 16 knots (18 mph; 30 km/h)Southern Pride with many modifications. She was 30 feet longer for better speed, taking in account estimaetd U-Boat surfaced speed, and was propelled by two marine oil-fired boilers which can be manufactured in just 16 weeks instead of classic water tube boilers requiring about seven months.

Indeed by early 1939, the admiralty wanted far more escort ships, fearing a repeat of the U-boats warfare of WWI, especially on the east coast of British Isles, what became later the “Western Approaches”. A fleet of dedicated, cheap and small vessels, yet larger and faster than trawlers vessels made in small merchant shipyards, whoch wiuould form the small convoy escort division, available quickly and en masse. These were initialy intended for coastal convoys however, but the design of the original vessels, long range hunters, meant they would perfectly fit the need of mid-oceanic escorts as well, and so they would ncquire their fame in the battle of the Atlantic. They were to be be deployed for the first half of the trip, but later they were present all along.

Contemporary Patrol Ships

The Flower class was not the only escort vessels the Royal Navy had in 1940. To be exact, these were not really useful and so absent from records in peacetime, but not entirely. In 1934 indeed, with a dreaging international situation, the admirakty seeked to resurrect the escort ship concept, through a “patrol ship”, technically tasked to practice submarine-hunting in home waters. The RN built first a serie of six “patrol vessels”, the Kingfisher class. Built by known Navy yards, Fairfield, Stephen, Thornycroft and Yarrow, the HMS Kingfisher, Mallard, Puffin, Kittiwake, Sheldrake and Widgeon (the last launched in 1938) were just commissioned when WW2 broke out, followed by the three improved Shearwater class (Shearwater, Guillemot, Pintail) launched in 1939. They looked like sloops or gunboats with a classic forecastle hull with straight prow, a 4-in Mk.V gun forward, and from 30 to 60 depht charges, with dix projectors and two long racks afte. They really were specialized, military vessels, with relatively high speed (20 knots thanks to Parsons Turbines) but a limited range to to their 120-160 tons of oil. In practice none really had any influence on wartime designs, as the later River class drew more on improving the Flower concept than these prewar vessels.

Also of note were a group of fifteen US PCE type sub-hunters and patrol vessels obtained via lend-lease when available. Home water escort was provided mostly by large less than 100 tons vessels, built by Dennys and Fairmile, MGB (“Motor Gunboats”) and HDMLs. Alongside the Flower class, the RN also frequently operated Minesweepers as escorts, as they were built for this precise dual role: The Halcyon and Bangor, Bathurst, Algerine classes and a diverse fleet of armed trawlers, about 300, also built Civilian yards alongside the Flower class: Let’s cite the Basset, Tree, Dance, Shakespearian, Isles, Hills, Round Table, Fish, and Military class. The latter were no small vessels: They reach 1010 tonnes fully loaded and were capable of good seaworthiness in degraded conditions, but not to the level of the Flower class. And these were only tailor-built vessels, completed by scores of requisitioned trawlers converted as such.

Order and Production

The design was rapidly and a first bulk order was placed to rapidly ramp up a suitable anti-submarine force from scratch. The first order called for 26 vessels and more so that by mid-1939 no less than 110 were already under construction in the contracted civilian shipyards around the country. Surprisingly enough, even large ones, accustomed to very large vessels were contacted, such as Harland and Wolff yard of Belfast, constructors of the Titanic and many other prestigious liners. By September, 180 ships in all in the RN were fitted with Asdic at the time, the best known underwater submarine detection system: 150 destroyers, 24 sloops, 6 were coastal patrol vessels. Destroyers were diverted for fleet escort and not present in fleet convoys, while sloops were not at ease in gale conditions in the North Atlantic on winter. Coastal patrol vessels however were later classed as corvettes and became soon the bedrock of the escort forces.

In total British shipyards alone would deliver 145 vessels of the initial design, Canadian shipyards 121 of a modified and improved design with greater displacement to accomodate a larger crew size and better armament such a single 4in BL Mk.IX gun, one Hedgehog and two twin 2-pdr ‘pom pom’ guns and up to six 20mm Oerlikon cannon plus 70 depth charges in racks and projectors. By the end of January 1940, 116 were in construction, plus ten ordered from Canadian shipbuilders being transferred to the RCN. And the idea was also soon considered by the French Amiralty which lacked ASW vessels. Four were ordered for the French Navy, the first being completed after the fall of France and thus, transferred to the Free French Naval Forces, the remainder taken over by the RN. Four more were buult in France on the same design, but captured completed by the Germans (see later). 31 were ordered by the RN under the 1940 War Programme, 6 cancelled on 23 January 1941. Already at the time, replacement was on its way.

Design evolution

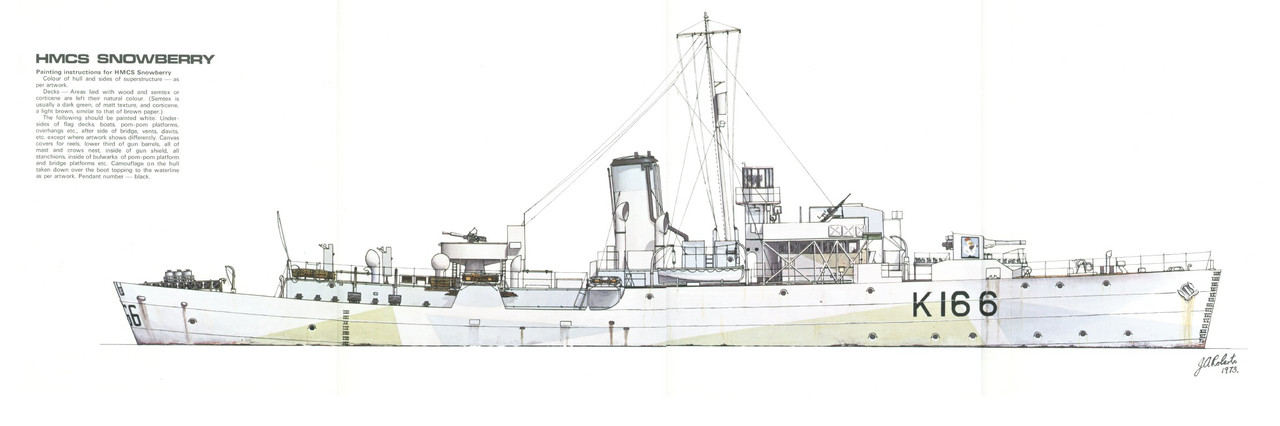

A very nice 3D depiction of a typical Flower-class corvette, HCMS Snowberry (From Pinterest)

A very nice 3D depiction of a typical Flower-class corvette, HCMS Snowberry (From Pinterest)

The simple design of the Flower class using parts and techniques, notably scantlings, proper to merchant shipping, so to be built uqing well known techniques in small commercial shipyards the UK and Canada. The use of commercial triple expansion machinery also simplified construction, but did not favored speed. However it simplified their use, making work of the Royal Naval Reserve and Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve crews far easier as they were familiar with their working.

The Flower-class vessels were rather slow for at 16 knots (18 mph; 30 km/h). For information, the Type VIIA indeed only reached 16 kts on diesels, surfaced, but the VIIB reached 17.2 and the VII 17 knots with later versions such as the VII/42 being capable of 18.5 kts and the large Type IX 18.2 to 19.2 knots.

Amrmament wise, this was light to say the least, as they forcuse on ASW weaponry. Many original designs however were initially fitted with minesweeping equipment, and no AA at all but two depht charge throwers aft and two racks plus reloads. The only real weapon onboard was the forward mounted 4-in/45 BL Mark IX, to at least fire on a surfaced U-Boat. It was mounted high so that it could play its lowest elevation.

The modified Flowers were later fitted with limited anti-aircraft weaponry, which was increased over time. The early design included the trademark raised forecastle and a well deck. The bridge or wheelhouse was continued by a lower deck aft, about 1/3 of the lenght. The crew quarters in the forecastle were far from the emachinery but close to the battered prow in heavy weather. The galley was at the rear, and messing arrangements were criticized.

Profile of HCMS Snowberry (Forum laroyale-modelisme.net)

Profile of HCMS Snowberry (Forum laroyale-modelisme.net)

The modified Flowers had the forecastle extended (“long forecastle” design), providing a larger space for the crew could out of the weather, but the added weight (Lenght and width were about the same, the bridge was further forward and taller) ships’ stability and speed was improved. Older Flower class had also their forecastle extended, and the hull section was altered forward and aft above the waterline to give more sheer and flare. Bilge keels were added and or deepened, the bridges improved, splinter protection also, electric power was augmented so serve radars, detection equipments and extra AA. Steam heating and better ventilation was procured alsoin living space, making the crews less miserable in heavy weather. The very early vessels were always damp and wet internally.

So many modifications were made to the first Flower-class vessels during mid and latter years of construction, all the way to late 1942. The original Flowers had a mast forward the bridge, but on the modified ones, it was relocated returned to the “normal position” aft of the bridge. A cruiser stern was added in place of the original trawler/whaler design also. The Improved Flower had the same output but higher oil reserves. AA was augmented as well as the DC capacity. As for the Castle class, changed were so many a new name was applied to it (see later). It was basically a more military design, closing on the River class Frigates, but they were few in comparison of the original “Flower”.

The class is also called by many authors “Gladiolus class” as she was the first launched, on 24 january 1940, laid down at Smith Docks, south Bank in October 1939, meaning construction took a mere four months ! She was completed in March 1940, being one of the very first batch in service. Among the last built was HMS Poppy (K213) in Yard 677 of Hall, Aberdeen, started on 3.1941, launched on 20.11.1941 and completed in May 1942, with the whole set of modifications brought by Smith’s team, passed onto the other yards.

Early_plans_for_the_Flower_class_corvette

flower-class-early-type1939

flower-class-early-type

hmcs-agassiz-k129-1941-flower-class-corvette

General design & Protection

Prow of an early type, with the mainmast forward of the bridge.

As said above the basic design was inspired by the north sea whaler Southern Pride. She was a steam-powered whaler from Smiths Dock, Middlesbrough, in 1936. She measured 160 ft (49 m) for 582 GRT of civilian displacement, and its VTE engine procured a top spee of 15.25 knots (28.24 km/h; 17.55 mph). Construction rested on scantlings, and the forecastle was fairly short, about 1/4 of heir entire lenght, with the whaling harpoon gun on a platform. She was converted into a warship after requsition in six weeks at 75,000 pounds and after five years of service, was wrecked off Freetown in June 1944.

HMS Jonquil (K-68) in 1942, a late type.

Differences were many, but overall, the forecastle was extended aft as the first measure. The former harpoon gun location was eliminated for the main gun to be moved on a platform closer to the bridge. The latter was enlarged and the freeboard considerably augmented. The hull was made more marine, with a bit more flare and sheer. The early vessels had the same clipper style stern but it was changed later for a cruiser stern. The fact the basic hull was lengthened by 30ft by Reed, was intended in part for propulsion improvement, allowed to reach one more knot. It allowed to increase also the number of watertight compartments for ASW protection, the extra internal volume was usable for the ammunitions and depth charges magazines and a larger crew required to operate an armament that simply did not existed on the base design.

In terms of protection, it was simply inexistant, which was a condition for a construction in civilian yards, unable to deal with complicated welding technique and hardened steel, already in high demand anyway in military yards anyway. Its only much later during the war that simple splinter protection was added, sometimes consisting on only internal paint, but the crews managed to add themselves extra plating, until this practice was forbidden due to obvious stability issues. The larger size of the design made the admiralty considered no longer as a “patroller”, same category as the armed trawlers, but a “corvette”, the closest next rating. This was the first time the RN had “corvettes” in its inventory since almost centuries.

Propulsion

Cutaway of the class, from Issuu

It was essentially the same, amazingly enough for the base Flower, improved Flower, and the Castle class. It consisted in a unique VTE (Vertical, Triple expansion) steam engine, 2 cylinder, single-side fire-tube boilers of the “Scottish” type. Oil-firing was standard however. It was fed by two cylindrical boilers, but some later obtained from the navy two admiralty 3-drum models. This simple and trusted machinery well in the capacity of the yards, was assorted with a fuel capacity of 230 tonnes. The choice of oil was related to the 1939 RN standard and enabled more range with a smaller capacity. Boilers type and quality would change depending on the shipyard and later variants. The very first ones were the venerable scotch types, and the late types had the best of the tim, the much improved three drum boilers. Triple expansion engine were enough for 16 knots via a single shaft and 3 blade screw propeller, in lake like conditions only. However for each degraded sea state while stayling economical, it could fell quickly to 10 knots or less, maintained above at a greater consumption.

HMS Bellwort deck plan

This capacity was enough for 3,500 nautical miles at 12 knots, and this was enough for a single trip to the US (2,880 nm), and refuelling there, but of course during attacks they evolved and ran at a larger speed, consuming much larger fuel. Depending on their mode of operations, some made the mid-Atlantic trip, once releaved by Canadian Corvettes coming the other way, others made the full one. Fuel capacity was augmented as a test during construction: On HMS Meadowsweet it was augmented to 308, while on HMS Balsam, Godetia, Potentilla, and Tamarisk the new fuel tanks intended for the improved Flower had a 337 tons capacity. This enabled a 3,900 nm range, or simply allowed more flexibility while in convoy. In many cases, refuels at sea were performed.

Armament

Main Gun

4 inch Mk.IX gun on HMS Vervain, 1942

The weak point of the design, although not much could be done due to the stability issues and space aboard in general. At the time, it seemed important to possess at least a main gun to deal with enough punch against a surfaced U-Boat, and the choice soon fell on the well-known, proven, cheap and available 4-inches 45 caliber BL (101.6 mm), Mark IX. Weighting only two tons wthout the shield, it fired a 31 pounds (14.1 kg) AP or HE shell, worked with a Welin interrupted screw. It could depressed to -10 degrees (and elevate to +30 degrees), which was important, given its high position, to deal with relatively close U-Boats. The average rate of fire for a trained crew was around 10-12 rpm. Muzzle velocity was 800 metres per second (2,600 ft/s) and max range 12,660 metres (13,850 yd), practical below 5,000 m to deal with such small target, which basically only presented its conning tower to fire at. On Canadian corvettes, built later, as the late Flower built in UK in 1941, it was replaced by a 4-in/40 QF Mk XIX, with better performances. 100 rounds of ammunition were carried.

AA armament

QF2 MkVIII

Not included right away but introduced gradually, and expanded, it consisted at first of a single 40mm/39 2pdr QF Mk VIII “pom pom” with mounts Mk VIII bandstand mount amidships a pair of either Lewis paired Light Machine Guns, or Vickers liquid-cooled 12.7mm/62 heavy machine gun set in place. The latter was recoignised not very useful, and replaced generally by 20 mm/70 Oerlikon AA guns in single mounts. Typcally two were installed on the bridge’s reinforced wings on the late type Flower.

Depth Charges

Mk.VII depth charges

The usual set comprised two to four Mark II Depth Charges Throwers (DCT), aft on the poop deck, facing either side, and two Depth Charge Racks (DCR) at the stern. Each carried fiven but they were railing to the aft superstructure for a total storage of 40 more DCs. Reload was made by hand, using winches, always a dangerous task with a rolling deck washed by waves. These depht charges were of the standard British type, meaning it was the Mark VII: In entered service in 1939, weighted 420 lbs. (191 kg) and carried a 290 lbs. (132 kg) TNT with a sink Rate or Terminal Velocity of 9.9 fps (3.0 mps) with a max setting at 300 feet (91 m) later 500 feet (182 m).

The next Improved Flowers and Castles were equipped wit the same, albeit in larger quantities, until the Mark X (1944) and the Mark X*. The X** was not introduced in service in 1945 despite its great depth (down to 1,500 feet (457 m)). Squid and Hedgehog made them obsolete. There are doubts also if the Mark VII Heavy studied from 1940 and proper to depth charge launchers were used aboard, outside experimentally. Weighting 420 lbs. (191 kg) with a 290 lbs. (130 kg) TNT charge, they had a sink rate/terminal velocity of 16.8 fps (5.1 mps) and a 300 feet (91 m) max setting, helped with a 150 lbs. (68 kg) cast-iron weight attached. The idea was to reach the U-Boat faster, and it was claimed it could split open a 0.875 inch (22 mm) hull at 20 feet (6.1 m), or force to surface at 12 m or more. The game changer was a minol charge (1942) for better results, with a 30% increase.

Hedgehog & Squid

Introduced on the Improved Flower and mandatory on the Castle class, these became the new standard for ASW warfare, pioneered by the Royal Navy. They are fully detailed in the ASW weaponry section.

Hedgehog: British “secret weapons” to replace the failed Fairlie Mortar tested in 1941, it was composed of a platform with a serie of 24 launcher spigots firing a 65 lb (29 kg) 7 in (178 mm) rocket carrying 30 lb (14 kg) TNT or 35 lb (16 kg) Torpex to 200–259 m (656–850 ft) and explosing by contact. This was a fast reaction, direct weapon answer ASW grenades could not give.

The Squid on the other hand was a more evolved form of ASW weaponry, introduced from 1943. It was composed of three mortar tubes firing a far more deadly charge, a 12 in (305 mm) projectile weighting 440 lb (200 kg) and carrying a 207 lb (94 kg) minol charge at 275 yards (250 m) and using a time fuse. It was used on the Castle class in 1944-45.

As for their minesweeping gear, it took valuable space on deck but was seldom used, and removed from all vessels (and omitted during construction) by late 1941.

Modifications

Armament-wise, HMS Delphinium, Erica, Hyacinth, Peony, Salvia were rearmed with a 3-in (76mm)/40 12pdr 12cwt QF Mk I/II/V or a 3-in/45 20cwt QF Mk III/IV, and a single 40/39 2pdr QF Mk VIII. HMS Gloxinia, Mimosa, Primula, Samphire, Snapdragon had the usual 4-in BL Mk IX, but an additional 3-in/40 12pdr 12cwt QF Mk I/II/V or Mk III/IV aft plus a single 40mm/39 2pdr pompom QF Mk VIII, and always the same DC provision.

Trivia: The crew and living, working condition aboard

Canadian Corvette captain (from pinterest)

Paired with the civilian yard construction and general design, the Flower class were designed to be manned by crews drawn from the Royal Naval Reserve and the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve (RNVR). Many captains were in complement also drawn from the Merchant Navy. They knew full well the problematics of the merchant vessels they escorted and often knew also the captains of those, helping to pass the concept of convoy into practice, despite sometimes some resistance. With the MAC (Merchant Armed Cruisers) and the other MACs (Merchant Aircraft Carriers) and CAM-ships they avoided to further overtax the Royal Navy. But it was not rare for former Flower class crews to later operate on River class Frigates, taking advantage of their experience.

The daily experience of a crew on such vessel was not brillant, especially in the North Sea, North Atlantic, and along the “murmansk road” especially in winter. The very early Flower class was quite crude in its accomodations and very damp. Location of the living quarters were ideal on the design standpoint but in real life, this made the whole space quite wet. Although the Flower class rode the waves well, even better in heavy weather compared to most destroyers, they were still small and not immune to wave large enough to crash on her decks.

Still, life on board was generally miserable, cold, wet, monotonous, uncomfortable, each wave crashing on the Foc’sle being followed by a cascade into the well deck amidships while men at action stations were drenched constantly. Spray even entered living spaces through hatches opened in order to pass ammunition magazines, often opened during alerts for hours. Interior decks were also drenched by condensation, which dripped from overheads, not helping the crew to sleep, sometimes so exhausted they kept the same outfit for days on end. The sole sanitary toilet was drained by a straight pipe to the ocean and reverse flow would just spread icy water into the ship and surprise those using it.

One crucial part of this discomfort was linked to over-population aboard, with twice as many crewmen as anticipated, which slept where they could, on lockers or tabletops, avoiding the floor, always damp. Perishable food cannot be kept aboard due to constant moist and the crew became accostumated to corned-beef and powdered potato as daily meal for weeks.

Despite some praising their ability to stay afloat even in the worst conditions, they still rolled heavily, up to 40° either side permanently. So “greenhorns”, young crewmen, were sick for days on in heavy seas as their host “would roll on wet grass” and this personal was basically close to useless the first weeks, they needed at least one or two convoys to acclimatise. Still, the ship were seaworthy enough that no sailor ever fell overboard between actions.

As it is said below in action records, the worst of the worst was experienced by crews on the arctic road, fighting constantly against the cold, and frantically de-icing the ships everyday to avoid them toppling over. If that was not enough, sleeping was almost impossible but for the most exhausted, with the main living quarter forward being not only constantly beaten by waves, with the ship’s hull twisting noises, but constant noise of other sailors just coming and going between quarters and eating, living in that same space. On top of that was the obvious danger of a torpedo hit. Devoid of any protection, any would just fill the vessel in a mere seconds, sending her to the bottom with all hands. It was rare to manage to survive, but some did. Mine hits, due to their larger payload, was always fatal. However, especially in late 1941 and early 1942 when the Luftwaffe was present over the Atlantic and escort carriers since not in sight, air attacks took their toll but were only fatal in four occasions. The ships were rugged and AA armament was considerably augmented past late 1942, resulting of even more ammo to store aboard and extra crewmen for already saturated living quarters.

HMS Gladiolus original specs (1940) |

|

| Dimensions | 62.48 x 10.11 x 4.14m (205ft 4in x 33ft 2in x 13 ft 7 in) |

| Displacement | 900 t standard to 1110 t FL |

| Propulsion | 1 shaft VTE, 2 Scotch boilers, 2,750 shp |

| Speed | 16 knots () |

| Range | Oil 230 tons, 3,500 nmi/12 kts |

| Armor | None |

| Armament | 1 × 4-in Mk IX, 2×2 0.3in Lewis AA HMG, 40 DCs |

| Crew | 85 |

HMS Bluebell, late type

⚙ HMS Balsam 1942 (late type) |

|

| Dimensions | 63.5m lenght, 4.8m DL (208ft 4in, 15ft 9in) |

| Displacement | 1170 tons standard, 1,390 tons Fully Loaded |

| Propulsion | 1 shaft VTE, 2 admiralty 3-drum boilers, 2,750 hp. |

| Speed | 16.5 knots |

| Range | 337 tons of oil, same range |

| Armor | 0.5 in plating in some places |

| Armament | 1× 4-in/40 QF Mk.XIX, 2x 2-pdr pompom, 4x 20mm AA, 40 DCs |

| Sensors | Huff Duff, Type 271 radar, type 123 sonar |

| Crew | 109 (1942) |

The Canadian Flowers

List given. Relatively similar to the British ones but generally with a better engine. HCMS Brantford, Calgary, Charlottetown, Dundas, Fredericton, Halifax, Kitchener, La Malbaie, Midland, New Westminster, Port Arthur, Regina, Timmins, Vancouver, Ville de Quebec, Woodstock were armed with a 4-in/45 BL Mk IX main gun, single 40mm/39 2pdr QF Mk VIII pompom and two 20mm/70 Oerlikon Mk II/IV from the onset and a 24-tubes 178 Hedgehog ASWRL as well as 4 DCT, 2 DCR and 70 grenades in reserve.

⚙ HCMS Chambly specifications |

|

| Dimensions | 57.9 pp, 62.5 oa* x 10.1 x 4.14-4.80m DL |

| Displacement | 950 t, 1280 t* FL |

| Propulsion | 1 shaft VTE, 21 cyl boilers** |

| Speed | Same |

| Range | 230 tons oil but 3,500 nm/12 kts |

| Protection | None but anti-spall liner, some light armor plating late. |

| Armament | Same but Mark IX 4-in, 2×2 Vickers 0.5 in AA. |

| Sensors | Type 271 or type 286 radars, type 123 sonar |

| Crew | 109 |

*HCMS Calgary, Charlottetown, Fredericton, Halifax, Kitchener, La Malbaie, Port Arthur, Regina, Ville de Quebec, Woodstock were 63.5m long oa, 1015 tons standard, 1350 tons FL.

**HCMS Calgary, Charlottetown, Fredericton, Halifax, Kitchener, La Malbaie, Port Arthur, Regina, Ville de Quebec, Woodstock, Brentford, Midland, New Westminster, Timmins, Vancouver had Admiralty 3-drum boilers.

***Same as above, 1x 4-in (102mm/45) BL Mk IX, 1x 40mm/39 2pdr QF Mk VIII, 2x 20mm/70 Oerlikon Mk II/IV, 24x 178 Hedgehog ASWRL, 4 DCT, 2 DCR (70 DCs).

Improved Flower (1942)

HMS Clarkia, a late type, showing her longer forecastle, but low bridge.

British Yards: Betony, Bugloss, Burnet, Forrest Hill, Giffard, Mimico, Arabis, Arbutus, Balm (cancelled 11.1942), Charlock, Long Branch (ex-Candytuft) (RCN).

Canadian Yards: Atholl, Cobourg, Fergus, Frontenac, Guelph, Hawkesbury, Lindsay, Louisburg, Norsyd, North Bay, Owen Sound, Rivière du Loup, St. Lambert, Trentonian, Whitby, Comfrey, Cornel, Dittany, Flax, Honesty, Linaria, Mandrake, Milfoil, Musk, Nepeta, Privet, Rose Bay, Smilax, Statice, Willowherb, Asbestos, Beauharnois, Belleville, Brampton, Ingersoll, Lachute, Listowel, Meaford, Merrittonia, Parry Sound, Peterborough, Renfrew, Simcoe, Smith`s Falls, Stellarton, Strathroy, Thorlock, West York.

Despite their surpringly good seaworthiness in all weather for their size, the admiralty thought the design could be improved, a task Smith’s docks was tasked for. A design was worked on, with more range, more space for better armament, more flare at the bow and a longer forecastle. The Canadian Yards delivered far more ships, as part of the revised 1942-1943 program, revised 1943-1944 program and British order for USN (reverse lend-lease).

The RN ordered 27 modified Flower-class corvettes under the 1941 and 1942 War Programmes. British shipbuilders were contracted to build seven of these vessels under the 1941 Programme and five vessels under the 1942 Programme; two vessels (one from each year’s Programme) were later cancelled. The RN ordered fifteen modified Flowers from Canadian shipyards under the 1941 programme; eight of these were transferred to the USN under reverse Lend-Lease. The RCN ordered seventy original and 34 modified Flower-class vessels from Canadian shipbuilders.

Canadian shipbuilders also built seven original Flowers ordered by the USN, which were transferred to the RN under the Lend-Lease Programme upon completion, because wartime shipbuilding production in the United States had reached the level where the USN could dispense with vessels it had ordered in Canada. The RCN vessels had several design variations from their RN counterparts: the “bandstand”, where the aft pom-pom gun was mounted, was moved to the rear of the superstructure; the galley was also moved forward, immediately abaft the engine room. The also had, like late British yards Improved Flower, retractable sonar domes instead of fixed units, reduced mast (the very last even has lattice masts), relocation of the galley along others. Alongside Oerlikon guns, many also carried Lewis MGs, paired, as they took little space.

There were few losses among these: Only Trentonian sunk on 22.2.1945 by U1004 and HCMS Merrittonia as a result of navigating error on 30.11.1945.

HMS Forrest Hill (1942) |

|

| Dimensions | 57.9 pp 63.5 oa long, same |

| Displacement | 1,000 t standard, 1,370 t FL |

| Propulsion | Same but 2 Admiralty 3-drum boilers |

| Range | 7,400 nmi/10 kts |

| Armament | 1x 4-in/40 QF Mk XIX, 1x 2pdr QF Mk VIII or 2×2 20mm/70 Oerlikon Mk II/IV, 2x 20mm/70 Oerlikon Mk II/IV or 4x 20mm/70 Oerlikon Mk II/IV, 1x 24 – 178 Hedgehog ASWRL, 4 DCT, 2 DCR (100 grenades) |

Castle class (1944)

Castle class (1944)

To RN: Allington Castle, Alnwick Castle, Alton Castle (cancelled), Amberley Castle, Appleby Castle (cancelled), Arnprior (ex-Rising Castle) to RCN, Avedon Castle (cancelled), Bamborough Castle, Barnard Castle, Barnwell Castle (cancelled), Beeston Castle (cancelled), Bere Castle (cancelled), Berkeley Castle, Bodiam Castle (cancelled), Bolton Castle (cancelled), Bowes Castle (cancelled), Bowmanville, Bramber Castle (cancelled), Bridgenorth Castle (cancelled), Brough Castle (cancelled), Caistor Castle, Caldecot Castle (cancelled), Calshot Castle (cancelled), Canterbury Castle (cancelled), Carew Castle (cancelled), Carisbrooke Castle, Chepstow Castle (cancelled), Chester Castle (cancelled), Christchurch Castle (cancelled), Clare Castle (cancelled), Clavering Castle (cancelled), Clitheroe Castle (cancelled), Clun Castle (cancelled), Colchester Castle (cancelled), Copper Cliff (ex-Hever Castle) to RCN, Corfe Castle (cancelled), Cornet Castle (cancelled), Cowes Castle (cancelled), Cowling Castle (cancelled), Criccieth Castle (cancelled), Cromer Castle (cancelled), Denbigh Castle, Divizes Castle (cancelled), Dhyfe Castle (cancelled), Dover Castle (cancelled), Dudley Castle (cancelled), Dumbarton Castle, Dunster Castle (cancelled), Egremont Castle (cancelled), Farnham Castle, Flint Castle, Fotheringay Castle (cancelled), Hadleigh Castle, Hedingham Castle, Helmsley Castle (cancelled), Hespeler (ex-Guilford Castle) to RCN, Humberstone (ex-Norham Castle, ex-Totnes Castle) to RCN, Huntsville (ex-Wolvesey Castle) to RCN, Hurst Castle, Kenilworth Castle, Kincardine (ex-Tamworth Castle) to RCN, Knaresborough Castle, Lancaster Castle, Launceston Castle, Leaside (ex-Walmer Castle) to RCN, Leeds Castle, Maiden Castle, Malling Castle (cancelled), Malmesbury Castle (cancelled), Monmouth Castle (cancelled), Morpeth Castle, Norwich Castle (cancelled), Oakham Castle, Orangeville (ex-Hedingham Castle) to RCN, Oswestry Castle (cancelled), Oxford Castle, Pendennis Castle (cancelled), Petrolia (ex-Sherborne Castle) to RCN, Pevensey Castle, Portchester Castle, Raby Castle (cancelled), Rayleigh Castle, Rhuddlan Castle (cancelled), Rushen Castle, St. Thomas (ex-Sandgate Castle) to RCN, Scarborough Castle, Shrewsbury Castle, Thornbury Castle (cancelled), Tillsonburg (ex-Pembroke Castle) to RCN, Tintagel Castle, Trematon Castle (cancelled), Tonbridge Castle(cancelled), Tutbury Castle(cancelled), Warkworth Castle (cancelled), Wigmore Castle (cancelled) York Castle (same).

To RCN: HCMS Arnprior, Bowmanville, Copper Cliff, Hespeler, Humberstone, Huntsville, Kincardine, Leaside, Orangeville, Petrolia, St. Thomas, Tillsonburg.

HMS Denbigh Castle (IWM)

This was the pinnacle of ASW corvette design in WW2, going further away from the intial concept to a fully fledged military vessel. A fully dedicated article will be done on these vessels in the future, so much they were modified and a new design compared to the previous Flower class.

The last development of the “Flower” class with a much longer hull to cure for good the issues of habitability and fuel stowage. Same machinery exactly, and despite the heavier tonnage and longer hull, speed was preserved and radius of action greatly enchanced. The armament was also reinforced, with the same gun but far better ASW suite resting on the new Squid system and less on depht charges now considered obsolete. AA armament also took a boost with up to ten 20 mm Oerlikon guns.

The “Castle” class was planned in the 1942 and 1943 programs with 59 ships on order but curtailed to 46, and just 39 entering service with the additional HMS Empire Shelter, Empire Rest, Empire Lifeguard, Empire Peacemaker and Empire Comfort completed as convoy rescue ships operated under merchant flag outside the Royal Navy, armed with just two 3-inm/40 guns and four 20mm Oerlikons. Production in Canada (37) was cancelled altogether. HMS Hurst Castle was sunk on the 1st September 1944 by U482 West of Ireland, HMS Denbigh Castle on 13 February 1945 by U992 in the Barents Sea. All were reclassified to frigates in 1947 and Berkeley Castle was docked after an accident on February 1953, never repaired and scrapped. Many also ended as Meteorological vessels with a single 40mm/60-mm Bofors gun and Squid, to be of use in wartime.

HMS Hespeler (ex-Guilford Castle) |

|

| Dimensions | 68.6m pp 76.8m oa x 11.2 x 4.11-4.19m deep load |

| Displacement | 1,010-1,060 t standard, 1,590-1,630 t FL |

| Propulsion | 1 shaft VTE, 2 admiralty 3 drum boilers 2,750 shp |

| Speed | 16.5 knots |

| Range | 480 tons oil, 6,200 nmi/15 kts |

| Armament | 1x 4-in/40 QF Mk XIX, 2×2 + 6 single 20mm/70 Oerlikon Mk II/IV, 1×3 12-in Squid Mk 4 ASWRL, 2 DCT, 1 DCR (15) |

| Sensors | Type 271/272 radar, Type 144 and type 147 sonars |

| Crew | 120 |

The Flower class in action

These Flower-class corvettes started to be commissioned in mid-1940. They immediately proved remarkable for their small size, quite cabale in heavy weather in which destroyers for example, had a hard time. Their crews were hardy fellows, accoustomed to excessive rolling and poor accomodations. Their speed was never enough for the task at head though, with their valiant 4-cylinder, triple-expansion (TE) engine only rendering 2-3 knots less than surfaced U-boat (since they operated this way by night) and were in any case well below the minimal 20 knots required for ASW warfare by the naval staff. This meant that quite soon, plans were made for a replacement with a better speed and other improvements.

Their small size meant not only they could not accommodate more sophisticated ASW hardware, and lacked range as well. From mid-1941 forward-firing hedgehogs were installed anyway while solutions were found to increase depth charges provision. They soon gained in 1942 enlarged bridges and better AA as well as a larger crew to serve these. These vessels were soon overloaded, so much they needed to carry ballast in compensation. By 1945 their improvement reach its zenith but gradually they were replaced by more capable vessels such as the US escort destroyers and British River class Frigates, faster, larger, better equipped and better armed.

The Flower class were exclusively given the unglamorous task of convoy escort, herded together with other vessels of many classes; British convoys generally always comprised a mid-1930s destroyer when available and one of the fifty modified ex-US four pipers of 1919-1921 vintage. Sloops were just too slow and small for this task. Most convoys ran at the slowest vessel’s speed, generally a pre-WWI steamer. The average was 12 knots, which happened to be the flower’s ideal cruise speed. The problem was that U boat had no problem converging on the convoy at 17-18 knots surfaced, and then attack by night. The only saving grace was their 8 knots submerged speed.

Tactics

The task of the Flower class was essentially, when located, to make keep their head below water as long as possible. The Flowers tried to pin them down long enough for the convoy to escape out of range and then rushed back in formation. It was a painful, dark, miserable routine in a war of attrition and the frustration of captains was their poor speed in order to properly chase the U-Boats. They were small, but still had some draught, enough to fall prey of the submarines they intended to hunt down. Convoys, vital for Battle for the Atlantic were composed on a main group with all the vessels in formation, several lines deep, flanked by their shepherd dogs, the escorts. Convoys started well before the first Flower class was operational, on September 1939 and went on until May 8 1945, both in the North and South Atlantic and later Arctic from 1942.

When they arrived in 1940, the first Flower class started to replace hard-pressed destroyers, freed to take on fleet jobs. After the threat of German commerce raiders vanished and the fall of France, Admiral D£onitz setup his HQ in Lorient and from then on, by late 1940, U-Boats started to operate from the Coast of France, and Norway later. In the “box pattern”, Flower class were the slow division and usually stayed closer to the pack, whereas destroyers took more distant posts, ready to pounce on any signal. Flower class were slower to react and operate, and took long to take back their position, hence their position usually closer to the main convoy.

The Convoys they escorted varied considerably in size, and on average reached in mid-1941 to 30 ships, in 6 lines abreast spaced around 500 yards apart plus five ships long, spaced up to one mile in front. Tankers and troop ships were placed in the middle, faster, more survivable cargoes on the flank, called the “coffin corner”. By late 1940s when the Flower entered service, the escorts was quite thin, sometimes down to a single escort. The Flowers class would see action mainly in the Atlantic, north and south, but not only: Some escorted convoys in and out the Indian ocean and Mediterranean. Some were found in need of better AA when escorting the extremely dangerous convoys to Malta from Egypt or Gibraltar, as well as Italy and Greece.

When spotting a surfaced U-boat, it was adviced to simply run directly at the submarine to force her to dive, crippling her speed and agility as well as blinding her. Keep U-Boats down, making passes upon passed of depth charge long enough to allow the convoy to escape was the favorite tactic, even if the Depht Charges were rarely sufficient to destroy an U-Boat. Many just choose to dive deeper and even sit on the bottom when possible, full silent, until the escort was far away. The problem was by night as U-Boats on diesels could sometimes out-run Flower class Corvettes, but this could fall at 8 kn (15 km/h; 9.2 mph) in poor weather or less, a situation in which the corvettes were at an advantage. Still, they rarly go hunting for far away U-Boats that were detected or spotted. This was the job of destroyer. A Flower could have been cleverly distracted while other U-Boats attacked undefended corners, and time to catch up after a chase was considerable.

“wolf-pack” attacks were devised in 1942 to overwhelm escorts, using their numbers to distract them while one or two could pass undetected into the convoy and caused havoc. Better sensors and armament helped to re-establish some balance, in particular radar, HF/DF (for longer range telecomunication detection), and the ASDIC, which becemae better and more senstive as the war progressed. Still, tactical advantage always resided with the attackers, choosing their operating mode and generally draw defending Flower off-station. It is generally assumed that U-Boat kills was a measure of their success, but in reality this was more to do with tonnage effectively protected. Ofter U-boat were detected and not engaged if far away, while some guns and depth charges were more to push out these U-Boats away, followed by a full speed return to station. Skirmishes by many shadowing U-Boats were common, and exhanges were rarely decisive, but it put the men aboard on their nerves, driving exhaustion.

Continuous actions demanded always greater seamanship skills and this was taxing on the crews. Exhaustion was such it led to a collision with escort and merchant ships, leading to damage and in a case, a sinking in shallow water. Mines were also a danger, ans five were lost that way, but aviation less, as four were sunk this way. Their AA was considerably reinforced over time while Luftwaffe’s presence dwindled down and by 1943 was localized mostly in Norway.

But the most dreaded route of all, for its multiple dangers and terrible conditions, was the route to Russia. Every merchant men and reservist crew on these little escorts was preying not to be assigned to the Murmansk road, dubbed the “worst journey in the world”. Sub zero temperatures and ice added to rough seas transformed the trip into a nightmare: Each crewman when not on duty elsewhere was struggling to keep out ice from the ship, which soon clogged not only the deck but everything standing on it, to the point the ship would capsize. One solution was to connect hoses to the engine exhaust or steam circuit and work with this, but as soon as the cold set in again, combined with permanent saltwater drenching, it was to be performed all over again, everywhere, all the time.

In addition to Uboats, officers on the bridge, open (that why later Flower class models were preferred there, as the earlier one’s tiny bridges saw their windows frozen solid and obscured, had to scan deriving ice day and night not to follow the fate of RMS Titanic. When the weather improved, they were easy targets for air spotters and the Luftwaffe as well as ambushing U-Boats. The Flower, still were able to roll on a damp lawn and most of them survived in quite appealing conditions, when their whaler origin talked.

In late 1942 some also took part in operation torch assisting troopships safely in position and some even overed the landings, providing shore bombardment. They also departed and patrolled in the vinity against always possible Vichy French submarine attacks, forming anti submarine screens. In fact each time a convoy of troopship was mobilizer, the Flowers were there: They also covered the landings in Sicily and Italy, Normandy and Provence. During the reinforcement operations after D-Day, they created a norial of vessels, forming a strong anti submarine screen around the shipping channels from Britain.

By late 1944, the game was nearly done in the Atlantic, as the U boat threat was now greatly diminished and now, the Flowers, outclassed and surplus were gradually withdrawn from service depending on their general state, ending as training vessels or simply pout into reserve to free those preciously experienced crews. They quietly disappeared in various scrap yards, but the better preserved were either sold or found many civilian uses (see later). By 1943, despite constant imporovements, the design, in light of combat experience, was generally seen as obsolete. Now more experienced shipyards concentrated on more advanced River-class frigates and Castle-class corvettes. But until they arrived, convoys were always covered at 50% at least by Flower class corvettes.

The HMS Sunflower’s case

HMS Sunflower underway during sea trials.

Probably the most successful Flower class corvette of WW2 was HMS Sunflower. I hope to give a clue about what was the operational life of each and every of these Corvettes through this shining example:

HMS Sunflower was born as K41 in Smith’s Dock Co., Ltd. on South Bank-on-Tees, the original creator of the serie. She was laid down on 24 May 1940, launched on 19 August 1940 and commissioned on 25 January 1941. During work-up, sea trials and initial training with a green crew (see later), she escorted the RN submarine HMS Thunderbolt and Surcouf during their passage to the Firth of Clyde. The second was captured in July 1940, interned and later passed onto the Free French Navy, before disappearing in strange circumstances in the gulf of Mexico. As one of the very early batch, she still had the original reciprocating 4-cycle VTE engine with Scotch fire-tube boilers and her 16 knots speed was only nominal.

She was soon assigned to one of the eight escort groups formed as part of the Western Approaches Command. She even was part of the 1st Escort Group, with six destroyers and four sister ships. Their first convoy escort was between 19 July and 1 August 1941, with Convoy ON 69 (26 merchant ships). At the time they encountered a pack of 8 U-boats and 2 Italian submarines from Bordeaux. In February-March 1942 a reaorganization saw her reassigned to the Mid-Ocean Escort Force (MOEF) and she joined Escort Group B7, the last of such naval groups. She took part in Convoys HX126, HG 59 from Gibraltar, OB 323 to Dispersal Point, Convoy HX129, SC34, OB330 and OB336, OG69, HG68, SC39, HX146, ON10, ON15, HX153, ON30, ON39, HX159, ON42, SC57, ON49, SC60, ON55, HX169 and was under refit by February 1942, with a Type 271 fitted. In fact during her carrer she was fitted with a SW1C and later 2C radars and a Type 123A and later Type 127DV sonar.

She went on in convoy protection in the dangerous midsection, North Atlantic and in the spring of 1942, had the chance of relatively uneventful missions, but this changed in the summer and autumn, but still, with no losses. By 11 December she had her first serious test with ON 153 when three merchantmen were sunk during a night attack, seeing HMS Firedrake torpedoed by U-211, which sunk witll all hands including the convoy commander (Ggroup’s Senior Officer – Escort or “SOE”) Eric Tilden. She depht-charges several U-Boats without kill and rescured 27 survivors. Current captain of HMS Sunflower, Lt. Commander John Treasure Jones, took charge next as SOE based on seniority.

Group B7, a cross designated HMS Sunflower

B7 also saw firce battles with ONS 20, 206, 207 and 208, but the better experiences crews by now succeeded in having no less that nine U-boats sunk or badly damaged. In February 1943 A/Lt.Cdr. James Plomer, RCNVR took command, and her success streak would change dramatically. His first mission was Convoy ONS 5 (46 merchant ships) from Liverpool 21 April 1943. By early May submarine attacks would go up and on the 5th, she succeeded during one attack to correctly pickup by sonar, then approach for a DC pass on a correct path and succeeded in sinking U-638, her first kill. The convoy arrived in Halifax on the 12th wuth the loss of 13 ships, but for 6 U-boats killed, which was a 1:2 ratio, better for the allies than in 1941.

During Convoy ON 206 (68 merchant ships) also from Liverpool (11 October 1943) there was an attack and she arrived in New York on the 27th, but with her second kill on 17 October, sinking by DCs U-631 South-east of Cape Farewell in Greenland. While on the 29th, a decisive Hedgehog attack by HMS Duncan and HMS Vidette claimed U-282, shadowing the Convoy. From 20 March 1944 she was commanded by T/A/Lt.Cdr. Leslie Hugh Stammers, RNVR. In May 1944 she was assigned to Force L and prepared for her mission in direct support to the Normandy Landings (Operation Neptune at the time). She was part of Escort Group 154, with HMS Sweetbriar and Oxlip. Their task was troopship escort in the English Channel and mocements in the area back and forth with Britain and reinforcements and supplies throughout the summer.

On 30 August 1944 she was based in Sheerness, always for Channel convoy defence and by October she was reassigned to Convoys from the Southwestern Approaches to the English Channel, and from London as Western France had been cleaned up of all Luftwaffe’s airfields. So the ships now transited via the souther route, off Normandy and to the north of the bay of Biscaye. By February 1945 she was back in Channel convoy defence, still facing occasional E-Boats sorties and mines from R-Boats as well as Snorkel U-Boats attacks gathered on convoys assembly points and soon she started to hunt for coastal traffic in Home waters in the north sea. The battle of the Atlantic was pretty much over at this point. T/A/Lt.Cdr. Herbert Samuel May, RNR was in command from 31 Jul 1944 until she was in reserve.

By May 1945, V-Day in Europe, due to her age and condition, she was paid off and placed in Reserve at Harwich until on the disposal list in 1947, sold for BU to Thos. W. Ward (Hayle, Cornwall), dismlantled from August 1947. He career only spanned four full active years but it was considered normal for these vessels considered “expandable” which worked with often both maintenance to the very limit of their capabilities. Like many other Corvettes she was pretty worn out in 1945. Complete Records on U-boat.net.

Here’s what her captain Treasure Jones had to say about her crew:

Around 90% of my crew had not been to sea before. They had been called-up, done a little training in barracks and then sent to man the ships. They were strengthened and knit together by a small number of trained ratings and naval pensioners. I had three officers plus an Engin-room Artificer, who was in charge of the engine and boiler rooms, with a Stoker Petty Officer to assist him. Of my three officers, only one had been to sea as an officer and he had just joined the Royal Naval Reserve prior to the war. My Second Officer was little older; his only sea experience was that he had served six months on the lower deck in one of the battleships, then been sent to an officers training college for 3 months; this was his first ship as an officer. My Third Officer was a young man of 19. He had joined-up straight from school, done six months on the lower deck as a rating, followed by 3 months at an officers training college before being appointed to my ship. I was daddy to these men was well as Captain, since I was 35 at the time…

HMS Sunflower’s story motivated a famous best seller, Nicholas Monsarrat’s “The Cruel Sea”, adapted into a 1952 war film starring Jack Hawkins and Denholm Elliott, ranking among the greatest British war movies of all times. It was tribute to the most numerous escort on the British side, at some point representing in 1942 50% of all allied escorts. They contributed at a cost way below Frigates and DEs, to winning the war against the allies.

We will not go back into the armament and specific configurations of the class, but on their operational records here.

Feats and battle records

U-26 was sunk by Gladiolus on 1 July 1940.

Marcello-class submarine Nani was sunk by Anemone on 7 January 1941

U-70 was sunk by Camellia and Arbutus on 7 March 1941

U-110 was captured on 9 May 1941 by the destroyers Bulldog and Broadway and the corvette Aubrietia. U-110 was sunk the next day to preserve the secret.

U-147 was sunk by the destroyer Wanderer and Periwinkle on 2 June 1941

U-556 was sunk by Nasturtium, Celandine, and Gladiolus on 17 June 1941

U-651 was sunk by the destroyers Malcolm, Scimitar, the corvettes Arabis and Violet, and the minesweeper Speedwell on 29 June 1941

U-401 was sunk by the destroyers Wanderer and St. Albans and the corvette Hydrangea on 3 August 1941

U-501 was sunk by Chambly and Moosejaw on 10 September 1941

Argonauta-class submarine Fisalia was sunk by Hyacinth on 28 September 1941

U-204 was sunk by Mallow and the sloop Rochester on 19 October 1941

U-433 was sunk by Marigold on 16 November 1941

U-131 was sunk by the destroyers Exmoor, Blankney, Stanley, the corvette Pentstemon, the sloop Stork, and a Martlet aircraft from Audacity on 17 December 1941

U-567 was sunk by the sloop Deptford and Samphire on 21 December 1941

U-356 was sunk by the destroyer St. Laurent, with Chilliwack, Battleford and Napanee on 27 December 1942

U-756 was sunk by Morden on 1 September 1942

U-94 was sunk by a US Catalina flying boat and Oakville on 28 August 1942

U-588 was sunk by Wetaskiwin and the destroyer Skeena on 31 July 1942

U-379 was sunk by Dianthus on 8 August 1942

Perla-class submarine Perla was captured by Hyacinth on 9 July 1942

U-660 was scuttled after being damaged by Lotus and Starwort on 12 November 1942

U-124 was sunk by Stonecrop and the sloop Black Swan on 2 April 1942

U-82 was sunk by the sloop Rochester and Tamarisk on 6 February 1942

U-252 was sunk by the sloop Stork and Vetch on 14 April 1942

U-432 was sunk by the corvette Aconit on 11 March 1943

U-444 was sunk by the destroyer Harvester and the corvette Aconit on 11 March 1943

U-609 was sunk by the corvette Lobelia on 7 February 1943

U-536 was sunk by the frigate Nene, with Snowberry and Calgary on 20 November 1943

U-753 was sunk by Drumheller, the frigate Lagan, and a Canadian Sunderland seaplane on 13 May 1943

Flutto-class submarine Tritone was sunk by Port Arthur and the destroyer Antelope on 19 January 1943

U-163 was sunk by Prescott on 13 March 1943

Acciaio-class submarine Avorio was sunk by Regina on 8 February 1943

U-87 was sunk by Shediac and the destroyer St. Croix on 4 March 1943

U-224 was sunk by Ville de Quebec on 13 January 1943

U-135 was sunk by the sloop Rochester, the corvettes Mignonette and Balsam, and an American Consolidated PBY Catalina aircraft on 15 July 1943

U-306 was sunk by the destroyer Whitehall and Geranium on 31 October 1943

U-617 was destroyed while grounded by Hyacinth and the Australian minesweeper Wollongong on 12 September 1943

U-436 was sunk by the frigate Test and Hyderabad on 26 May 1943

U-192 was sunk by Loosestrife on 6 May 1943

U-125 was sunk by the destroyer Oribi and Snowflake on 6 May 1943

U-634 was sunk by the sloop Stork and Stonecrop on 30 August 1943

U-638 was sunk by Sunflower on 5 May 1943

U-631 was sunk by Sunflower on 17 October 1943

U-282 was sunk by the destroyers Vidette and Duncan and the corvette Sunflower on 29 October 1943

U-414 was sunk by Vetch. on 25 May 1943

U-523 was sunk by the destroyer Wanderer and Wallflower on 25 August 1943

U-757 was sunk by the frigate Bayntun and Camrose on 8 January 1944

U-744 was sunk by the destroyers Icarus, Chaudiere, Gatineau, the frigate St. Catharines, and the corvettes Fennel, Chilliwack, and Kenilworth Castle on 6 March 1944

U-741 was sunk by Orchis on 15 August 1944

U-641 was sunk by Violet on 19 January 1944

U-845 was sunk by the destroyers Forester and St. Laurent, the corvette Owen Sound and the frigate Swansea on 10 March 1944

U-1199 was sunk by the destroyer Icarus and Mignonette on 21 January 1945

Loss Analysis

Despite their initial shortcomings, the Flower-class proved instrumental in the Battle of the Atlantic and provided still in 1944 the backbone of Allied convoy escorts. 36 Flower-class corvettes were lost in this war, 50% to U-Boats, but they collectively claimed 50 U-Boats. Of the 22 torpedoed by enemy U-boats, most were during the heat of night combat, and later in the war by guided torpedoes. The 51 enemy submarines they sank comprised 47 U-Boats and four Italian boats. The most successful was HMS Sunflower, which claimed alone U-638 on 5 May 1943 and U-631 on 17 October 1943, whereas most kills were mostly collaborative effort. In the 51 sunk, they were clearly attributed to the Corvettes since uncontestable signs of sinking followed their own DC pass. Sunflower also shared U-282, on 29 October 1943, something Winston Churchill reported and the crew duly awarded. This was not as good as some RN frigates or USN escort destroyers, but still, quite a feat for what were essentially glorified whalers.

Canadian Flower class

Canadian Flower class

These were the HMCS Brantford, Calgary, Charlottetown, Dundas, Fredericton, Halifax, Kitchener, La Malbaie, Midland, New Westminster, Port Arthur, Regina, Timmins, Vancouver, Ville de Quebec, Woodstock (I) HMCS Agassiz, Alberni, Algoma, Amherst, Arvida, Arrowhead, Baddeck, Barrie, Battleford, Bittersweet, Brandon, Buctouche, Camrose, Chambly, Chicoutimi, Chilliwack, Cobalt, Collingwood, Dauphin, Dawson, Drumheller, Dunvegan, Edmundston, Eyebright, Fennel, Galt, Hepatica, Kamloops, Kamsack, Kenogami, Lethbridge, Levis, Louisburg, Lunenburg, Matapedia, Mayflower, Moncton, Moose Jaw, Morden, Nanaimo, Napanee, Oakville, Orillia, Pictou, Prescott, Quesnell, Rimouski, Rosthern, Sackville, Saskatoon, Shawinigan, Shediac, Sherbrooke, Snowberry, Sorel, Spikenard, Sudbury, Summerside, The Pas, Trail, Trillium, Wetaskiwin, Weyburn, Windflower (II).

HMCS_Agassiz

They were all built in Canadian yards along the 1939-1940 program. The Flower class were small vessels made in civilian specs, derived from a whaler design, lightly armed and slow, but well tailored for their ASW role. The class comprised the HMCS Brantford, Calgary, Charlottetown, Dundas, Fredericton, Halifax, Kitchener, La Malbaie, Midland, New Westminster, Port Arthur, Regina, Timmins, Vancouver, Ville de Quebec, Woodstock which were armed with one 102mm/45 BL Mk IX, one 40mm/39 2pdr QF Mk VIII, two 20mm/70 Oerlikon Mk II/IV, and one 24 – 178 Hedgehog ASWRL, 4 DCT, and 2 DCR with 70 deep charges in reserve.

HMCS_Amherst

The HMCS Agassiz, Alberni, Algoma, Amherst, Arvida, Arrowhead, Baddeck, Barrie, Battleford, Bittersweet, Brandon, Buctouche, Camrose, Chambly, Chicoutimi, Chilliwack, Cobalt, Collingwood, Dauphin, Dawson, Drumheller, Dunvegan, Edmundston, Eyebright, Fennel, Galt, Hepatica, Kamloops, Kamsack, Kenogami, Lethbridge, Levis, Louisburg, Lunenburg, Matapedia, Mayflower, Moncton, Moose Jaw, Morden, Nanaimo, Napanee, Oakville, Orillia, Pictou, Prescott, Quesnell, Rimouski, Rosthern, Sackville, Saskatoon, Shawinigan, Shediac, Sherbrooke, Snowberry, Sorel, Spikenard, Sudbury, Summerside, The Pas, Trail, Trillium, Wetaskiwin, Weyburn, Windflower were armed wth the same 102mm/45 BL Mk IX but for AA two 12.7/62 nstead of the 2-pdr, 2 DCT and 2 DCR. Electronics-wise they used a type 271 or for some ships, type 286 radars, and the type 123 sonar.

HMCS_Algoma

The Canadian “Flower” program started as a local production for the Royal Navy, when 10 ships were ordered, transferred to Canada before completion. The Canadians 70 more corvettes for the needs of the RCN, although the majority were extra equipped with a minesweeping equipment. They were launched in 1940-41 and completed in 1941, in a fairly short time on average. By 1943-1945, survived ships had extra light AA armament, one 40mm/39 2pdr QF Mk VIII, two 20/70 Oerlikon Mk II/IV or three, four in alternative, or two twin mounts of the same. ASW armament always comprised the 24-tubes Hedgehog ASWRL, 4 DCT and 2 DCR with up to 72 deep charges in reserve.

HMCS_Alberni

There were a few losses, as the U72 Submarine sank the HMCS Levis (possibly also U552, 19/9/1941). HMCS Charlottetown was sank by U517 on 11/9/1942 and HMCS Shawinigan by U1228 on 25/11/1944. HMCS Weyburn hit mines and sank on 22/2/1943 and HMCS Regina was sunk by U667 on 8/8/1944 while HMCS Albernie was also sunk on 21/8/1944 and HMCS Louisburg was sank in the Mediterranean by an Italian air torpedo on 16/2/1943.

The Flower class became arguably the most important vessels of the Royal Canadian Navy in numbers, forming the bulk of its forces, and their effort deserves much recoignition. Amazingly, it’s between the locally built and manned Flower and Rivers that the RCN gained the world’s 4th rank in tonnage, but its role is somewhat forgotten due to this rather obscure commitment compared to combat fleets. Stats-wise, they Canadians had 31 Enemy U boats confirmed sunk, 42 Enemy surface vessels sunk or captured and 25,345 merchant ship Crossings completed, but lost 33 ships in action with 1,797 Men.

Other users

The American Flowers

USS Intensity (PG-93) in 1943

In December 1941, the USN had a large building programme, including ASW ships but their completion was a long way away, so the Royal Navy agreed to transfer (it was called at the time “reverse lend-lease” ten Flower-class corvettes. These were commissioned vessels seeing actions since late 1940 in the Atlantic, reclassified in US service as Patrol Gunboats, numbered PG 62 to 71. They were known locally as the “Temptress class”. Soon, the USN placed orders for 15 more, to be delovered by Canadian shipyards, of the latest Modified Flower type. Eventually only eight were taken into service, the remainder being retransferred to the RN under Lend-Lease since they had been purchased by the USN. These latter, called the “Action class” were denominated PG 86 to 100.

Armament-wise the Temptress class had a British 4-inch gun forward, US pattern 3 in (76 mm)/50 DP gun aft, two 20 mm Oerlikon AA guns, two depth charge racks and four depth charge throwers (all US pattern). The Action class had two US 3-inch/50 guns and the Hedgehog ASWRL. None was sunk in action: They were the USS Temptress (HMS Veronica), USS Surprise (HMS Heliotrope), USS Spry (HMS Hibiscus), USS Saucy (HMS Arabis), USS Tenacity (HMS Candytuft) and for the Action class, USS Action (HMS Comfrey), USS Alacrity (HMS Cornel), USS Brisk (HMS Flax), USS Haste (HMS Mandrake), USS Intensity (HMS Milfoil), USS Might (HMS Musk), USS Pert (HMS Nepeta). Thos returned to the RN were the USS Beacon/HMS Dittany, USS Caprice/HMS Honesty, USS Clash/HMS Linaria, USS Splendor/HMS Rosebay, USS Tact/HMS Smilax, USS Vim/HMS Statice, and USS Vitality/HMS Willowherb.

Other users (allied and others)

Free French

These were the Aconit, Alysse, Commandant d’Estienne d’Orves, Commandant Detroyat, Commandant Drogou, La Bastiaise, Lobelia, Mimosa, Renoncule and Roselys.

Shortly after the start of the war the French Navy ordered 18 Flower-class ships. To gain time, 12 were to be built from UK yards (one delivered to the FFNF), but also six in France: Two from Ateliers et Chantiers de France (at Dunkirk) and four from Ateliers et Chantiers de Penhoët, Saint-Nazaire, accustome to larger vessels. The first two were listed as “cancelled” but the four others were captured after the fall of France by Nazi Germany, three completed for the Kriegsmarine by 1943–44 (see later). 18 in all were ordered by the French Government in 1940 but not transferred.

However, the RN would later block for delivery and retain four of them, later to be sent to the FNFL, and in addition transfer nine more to the FNFL (Free French Naval Forces), which soldiered on until V-Day in Europe: These were notably the Aconit, Commandant Drogou, Commandant Détroyat, Commandant d`Estienne d`Orves, Mimosa, Renoncule, Roselys, armed in 1944-45 with two twin Hotchkiss 7.7mm/87 LMG and two single 57mm/40 6pdr Hotchkiss Mk I, and two 20mm/70 Oerlikon plus 2 DCT for 72 DC at all, as well as a type 271 radar and type 128 sonar. All in all, there were tow losses, Alysse on 8.2.1942 by U654 and Mimosa on 9.6.1942 by U124. The first managed to stay afloat for two days before sinking, helping saving the crew.

Free Dutch

A single vessel, Friso (ex-Carnation) built in Grangemouth from 10.1939, launched 3.9.1940 and completed on 10/1940 was transferred and renamed on 3.1943 and then back to the RN on 10.1944, retaking the name of HMS Carnation.

Free Norwegian Navy

Andenes, Buttercup, Eglantine, Montbretia, Potentilla, Rose were transferred to the Free Norwegian Navy, four in 1941, one in 1942 and one in 1944. They were purchased postwar and had a long service, some as civilian vessels until 1969-71. Two were lost: Rose, Rammed and sunk on 26 October 1944 by Manners and Montbretia, by U-262 on 13 November 1942.

Royal New Zealand Navy

The RNZN employed two ships in WW2, Arabis, transferred on 16 March 1944 and returned in 1948 and Arbutus on 5 July 1944, same fate. They were likely BU afterwards.

Free Hellenic Navy

Four were transferred to the Free Hellenic Navy in 1943: Apostolis (former HMS Hyacinth), Kriezis (HMS Coreopsis), Sachtouris (HMS Peony), and Tombazis (HMS Tamarisk), transferred back to the RN in 1951-52 and BU.

Royal Indian Navy

In early 1945 as the need for Corvettes died down, four were transferred to the RIN to escort convoys in and out of the Indian Ocean: Assam on 19 February 1945 (HMS Bugloss) returned in 1947, Gondwana on 15 May 1945 (HMS Burnet) transferred back on 17 May 1946 and resold to the Royal Thai Navy as Bangpakong, Sind transferred on 24 August 1945 and transferred back to the RN on 17 May 1946 (HMS Betony) also resold to the Royal Thai Navy as Prasae and lost in 1951 on the North-Korean east coast. The fourth, Mahratta misses WW2 with the RIN as she was transferred only in 1946 and was not returned: Stranded, she was lost in 1947 (In ww2 she served as HMS Charlock).

Kriegsmarine

And yes, even the Kriegsmarine used these, as Patrouillenboot Ausland (patrol boats, foreign). These were the captured four French Navy Flower-class corvettes built in St. Nazaire-Penhoet and seized in June 1940 while in construction, completed in 1943-44 and renamed PA 1 to PA 4. These were the ex-Arquebuse (launched October 1940) assigned to the 15 Vorposten Flottille, sunk by RAF 15 June 1944 at Le Havre, ex-Hallebarde, same unit and fate, ex-Sabre, same and ex-Poignard not completed but by the Germans and relaunched on 1 September 1944 as La Télindière but sunk uncompleted as a block ship at Nantes.

Post war users

The relatively Flower class vessels were really an emergency solution designed to take car of the ASW escort problem. As military ships they were of little value compared to Frigates, and among the first to be declared surplus in 1946, discarded and sold. In addition they had been pushed hard and not spare by heavy weather in the North Atlantic and were worn out, sometimes more so than destroyer escorts and frigates. But not all were sold for BU. Indeed among those in the best general shape and condition, often the 1942 generation ships, some 32 coming from RN, RCN, and USN stocks were transferred to the following:

Argentina, Chile, Dominican Republic, Greece, India, Republic of Ireland, South Africa, Venezuela. They were cheap and usable as coastal patrol vessels, and cared for enough to last until the 1970s.

The Irish Navy notably bought three of them which became LE Macha, LE Cliona, and LE Maev, forming the bulk of its small fleet. Three more corvettes and surplus minesweepers were not purchased due to severe budget restrictions and these vessels served until 1968–1970. They were replaced by Ton-class minesweepers and benefited from 1973 from European funding for building three more modern ships in replacement. See the Irish Navy.

South African Navy

A single vessel, SAS Protea, was originally built at Charles Hill & Sons Ltd., Bristol, laid down 28 October 1940, launched 26 July 1941 and in servuced in WW2 as HMS, Rockrose, transferred on 4 October 1947 and converted as survey vessel, scrapped in 1967.

Free Belgian Navy

HMS Buttercup for example served with a Belgian volunteer crew from 23 April 1942 to 20 December 1944 (Royal Navy Section Belge) before transfer to the Royal Norwegian Navy as HNoMS Buttercup and later HNoMS Nordkyn until 1956 and 1969 as the whaler Thoris. A fitting end for that design. More famously, Godetia served from 12 February 1942 to 16 December 1944 in the Royal Navy Section Belge (sold 1947).

Free Yugoslavian Navy

HMS Mallow (which claimed U-204 in 1941) was transferred on 11 January 1944, renamed Nada and kept, renamed from 1948 Partizanka, and returned 1948 but sold afterwards to the Egyptian Navy (El Sudan). Another was sold, but for civilian service in 1946 and after some time under Panamean flag, ended as the Israeli Corvette Hagana.

In the remainder, all were not scrapped either. They were still valuable as large trawlers and of course whalers for civilian service, and it was the fate of 110 other surplus Flowers. Some even saw service as mercantile freighters, or used by smugglers, some were used as tugs or weather ships, quite capable to endure the worst conditions. HMCS Sudbury became a towboat specialized in deep-sea salvage and in November 1955, she rescued the freighter Makedonia in the North Pacific, towing her for a month in severe weather, making her famous for that feat.

The ex-Canadian Norsyd and Beauharnois were used as freighters but the latter under cover they worked for the Mossad LeAliyah Bet, one branch of the Haganah operated under the British Mandate for Palestine. These vessels organized Jewish immigration, carrying many refugees while being intercepted in the Mediterranean Sea in 1946 by the destroyer HMS Venus, and interned in Palestine, freed after the independence of 1948, while both ships were commissioned into the newly created Israeli Navy as INS Hashomer and Hagana.

The fate of RCN HCMS Sackville is unique however as the sold survivor of the 300+ strong fleet. She is owned by the Canadian Naval Memorial Trust, after being converted in 1952 as a research vessel for Canadian Department of Marine and Fisheries until the early 1980s and then acquired and restored to her original appearance by the trust. She is displayed in Halifax, Nova Scotia in the summer and spring and stored in the naval dockyard at CFB Halifax, cared for by the Maritime Forces Atlantic, Canadian Maritime Command. Not able to power herself, she is towed by a naval tug and yearly participating each Sunday in May to Commemoration of the Battle of the Atlantic ceremonies off Point Pleasant, at the entrance to Halifax Harbour. Official site

Gallery

HMCS-Alberni-launching-a-minesweeping-float-BC-coast-Mar-1941

HMS_Jonquil_IWM

HMS_Picotee_IWM

HMCS_Trillium_Bridge

HMCS_Riviere_du_Loup

H.M.C.S. GIFFARD K 402, R.C.N., Royal Canadian Navy-Flower Class Corvette, of W.W.II/1939-1945. Note: PENDANT NUMBER-Credit, Wikipedia. Brain CANUCK Murza…Killick Vison, W.W.II Naval Researcher-Published Author, Niagara Falls, Ontario, Canada.

HMCS Port Arthur K233

HMS Orchis (K 76) 6 May 1941 HMS Orchis (Lt. H. Vernon, RNR) picks up survivors from the British armed boarding vessel HMS Camito that was torpedoed the previous day by German U-boat U-97 in position 50°40’N, 21°30’W. 15 Aug 1944 German U-boat U-741 was sunk in the English Channel south-west of Brighton, in position 50°02’N, 00°36’W, by depth charges from the British corvette HMS Orchis (A/T/Lt.Cdr. B.W. Harris, DSC, RNVR).

HMCS Kitchener

HMS Campanula (K 18) 23 Aug 1941, HMS Campanula (Lt.Cdr. R.V.E. Case, DSC, RNR) picks up 38 survivors from the British merchant Aldergrove that was torpedoed and sunk by German U-boat U-201 north-west of Lisbon, Portugal in position 40°43’N, 11°39’W. 7 Feb 1943, HMS Campanula (Lt.Cdr. B.A. Rogers, RD, RNR) and HMS Mignonette (Lt H.H. Brown, RNR) together pick up the 37 survivors from the British merchant Afrika that was torpedoed and sunk by German U-boat U-402 in the North Atlantic

HMS Clarkia, Flower class corvette.

HMCS Lunenburg K151

Overall picture

The contribution made by these vessels to the allied war effort was considerable. While mobilizing Civilian Yards, and sparing tme and resources precious for other also vital military shipping they sank more subs than their own losses, and despite all their shortcomings, partly cured over time, until the excellent Castle class, they gave a tremendous operational experience which provided useful feedback to design and build a whole generation of new frigates and destroyers, notably the 1,390 tonnes River-Class. They were all the Flower could have been if managed as proper military vessels.

Between greater speed, endurance, seakeeping abilities, but with same armaments and sensors, they were still closer to the Flower-Class vessels. The Loch-Class frigate (1944) built in parrallel to the Castle class corvettes introduced new sensors and the Squid ASW mortar, achieving complete dominance over the North Atlantic. But this was all pioneered by the unsophisticated nearly 300 Flower-Class corvettes. In short, they proved to be the right ship at the right time. A measure of desperation that worked better than expected.

Scr/Read More

Links

hms sunflower records

navygeneralboard.com

uklandpower.com

On HMCS Amherst

On BBC ww2peopleswar/stories

wiki

silverhawkauthor.com on the castles and flower (super article !)

Flower Class Corvettes: Shipcraft Special, Pen & Sword Books Ltd, J. Lambert and Les Brown

The Australian Bathurst class (pdf)

southern pride on uboat.net

taubmansonline.com plans and schemes

Books

Gardiner, Robert; Chesneau, Roger, eds. Conway’s all the world’s fighting ships 1921-47

Alex H. Cherry wrote Yankee R N, the story of a Wall Street banker who volunteered for active duty in the RN, including details of Flower operations.

Peter Coy, who served in Narcissus in the North Atlantic between June 1942 and August 1944, wrote ‘The Echo of a Fighting Flower’ about her and B3 Escort Group, comprising two British and four Free French corvettes.

Hugh Garner wrote Storm Below which provides a detailed account of Flower-class corvettes and the stresses of shipboard life during World War II.

James B. Lamb wrote The Corvette Navy, which accounts the use of these vessels by the RCN during World War II.

Hal Lawrence wrote A Bloody War including first-hand accounts of his service aboard Moosejaw and Oakville.

Nicholas Monsarrat wrote the best-known fictionalised account of Flower-class corvette operations in his novel The Cruel Sea. A less well known volume by the same author, Three Corvettes, is a collection of wartime essays of his personal experiences as an officer on board a Flower, although only the first part deals with North Atlantic convoy escort duties.

Robert Radcliffe wrote Upon Dark Waters, a fictionalized account of Flower-class corvette Daisy, set in 1942 on the North Atlantic.

Denys Rayner wrote Escort, a first-hand account of his experiences as an officer aboard a Flower.

Douglas Reeman’s 1969 novel To Risks Unknown features the fictional Flower-class corvette Thistle.

Mac Johnston wrote “Corvettes Canada” aptly subtitled “Convoy Veterans of World War II Tell Their True Stories.”

Jane’s Warships of World War II (Harper Collins, 1996)

Jane’s Fighting Ships of World War II (Studia Publishing, 2001)

Corvettes (John Lambert, War Monthly Magazine)

Warships of the Second World War (Purnell’s History of the World Wars Special, 1973)

Videos

3D renditions – warthunder

HMCS Sackville Walkaround

Matsimus Flower class

Wow know Ur ship, Flower class

Drachinifel Flower class – Guide 124

Model Kits

The subject had been well overviewed, notably by Matchbox and then Revell at 1:72 scale, which is quite rare for ships of that size. But fleetscale also distributed a hull at 1:48. Other scales seen has been 1:96 Deans Marine & John Piper Collection, 1:144 by Revell, Model Craft Hobbies, 1:350 by Black Cat Models, Mirage Hobby, Iron shipwright, 1:400 by L’Arsenal, 1:700 by Atlantic Models, Triumph, Naval Works, White Ensign…

Revell’s gargantuan 1/72 HMCS Snowberry.

1:700 kit, hlj.com

Matchbox 1:72 Snowberry review, which preceded the Revell Kit.

Flower class general query

modelwarships.com hms bryony

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon