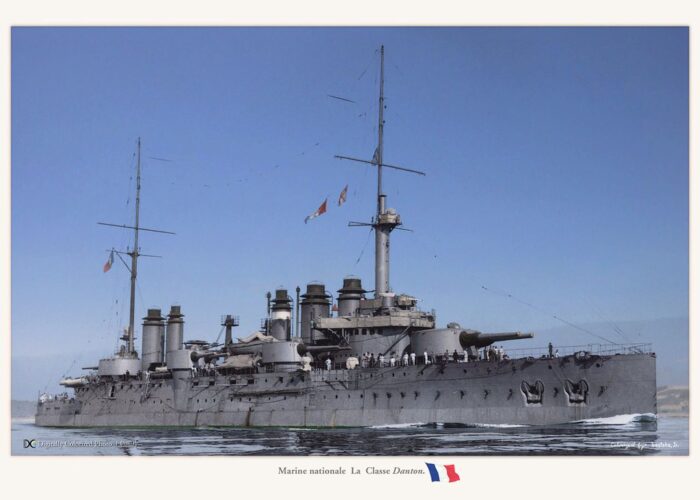

France (1909)

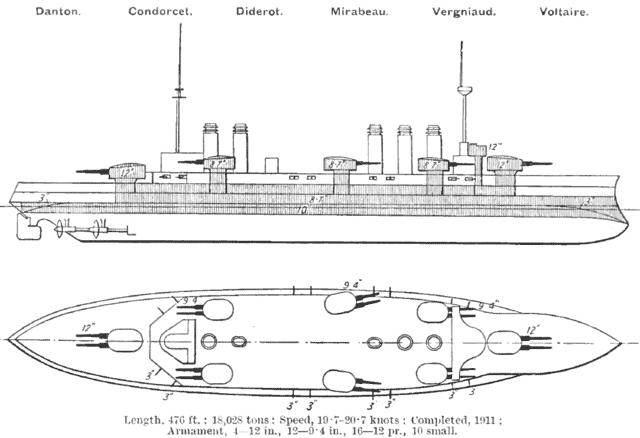

France (1909)Condorcet, Danton, Diderot, Mirabeau, Vergniaud, Voltaire

WW1 French Battleships:

Duperre class | Terrible class | Amiral Baudin class | Hoche | Marceau class | Charles Martel class (1891) | Charlemagne class | Henri IV | Iena | Suffren | Republique class | Liberté class | Danton class | Courbet class | Bretagne class | Normandie class | Lyon classThe six Dantons were the last French pre-dreadnoughts. They had the misfortune to be ordered in 1906-1908, when HMS Dreadnought was launched. However, the planned construction resumed until the delivery of the six ships in 1911, to be succeeded by the first French Dreadnoughts, the Courbets. The Danton spent their career in the Mediterranean, quite active in many theaters of operation. The delay and decisions to built them had been questioned a lot, and part of this post answers this. This post is the first of five on late French WWI battleships.

Development

France was famously delayed in the dreadnought race because of these particular ships, sparkling a lot of debates by later naval historians on why, even knowing about HMS Dradnought, their construction was maintained, causing France to enter WWI with a generation late of battleships. One one hand, the Dantons were quite improved compared to the previous Patrie and Liberté classes. They were heafty ships as 18,300 tonnes instead of 14,800 tonnes, and were the first to receive setam turbines on French battleships, they were thus faster at 20.6 knots on trials, and took into account Cuniberti’s 1903 design ideas by mixing to their main mm armament, a much larger secondary battery of 9.4-inches turrets, making them a compromise like the British Nelson class, the one and only French “semi-dreadnoughts”. But this was through redesigns.

To go there, this was of course a long road. The Danton-class were originally ordered as the second tranche of a French naval expansion plan. It was started in response to the growth of the Imperial German Navy after 1900. Discussions started in 1905 and it was already planned an improvzed repeat of the Liberté-class battleship design. The Russian defeat by the Japanese at the Battle of Tsushima by May 1905 of course had a profund impact on the French admiralty which were make to believe by analysts, that a large number of medium-caliber guns was the reasons the superstructures of the Russian ships was so damaged, impeding answer and keping the crew busy extinguishing multiple fires. This other factor was a superior speed and handling, which also was credited with a role in their victory. These were important lessons for the RN, which was comforted in its doctrine and design types, as the IJN was equipped in majority of British-built ships, but it was especially damning for the French Navy, which equipped and influenced heavily the Russian Imperial Navy. Many of its pre-dreadnoughts seeing action were indeed typical of the “Jeune Ecole”.

IJN Nisshin’s post battle damage assessment

This was a wakeup call for the French Navy, which decided that for the secondary artillery it was preferrable to increasing range and swap from the usual 194-millimeter (7.6 in) caliber to a more punchy 240-millimeter (9.4 in). It was believed these would have a greater ability to penetrate armor at longer ranges and a better rate of firethan 12-inches or 305 mm main guns. The second requirement was for faster ships, well above 20 knots of possible rather than 18-19 on pre-dreadnoughts.

However at the time, this means reducing armor thicknesses, without exceeding 18,000-metric-ton (18,000-long-ton) limits. These were dictated by the shipyard infrastructures at the time, plus bugretary constrains imposed of the Minister of the Navy of the time, Gaston Thomson. The preliminary design repeated the repeat of triple-expansion steam engines by March 1906, but with additional boilers to make up for the better top speed.

Proposals were made while the design progressed, especially when the new HMS Dreanought was known in construction and notably its new armament made of all 305 mm (12 inches) main guns. Naturally, some in the Navy wanted to replace the 240 mm guns turrets by single 305 mm (12 in) turrets making an additional sicx main guns, for ten total, making the first French “all-big-gun” ship. The single turrets were believed to keep a ring size identical to the 240 mm twon guns. But crucially, this was rejected. The argument was it would have raised displacement above the 18,000-metric ton limit. The second argument was that these main guns were slow-firing and the overall volume fire in contradition to the conclusions of the 1905 report.

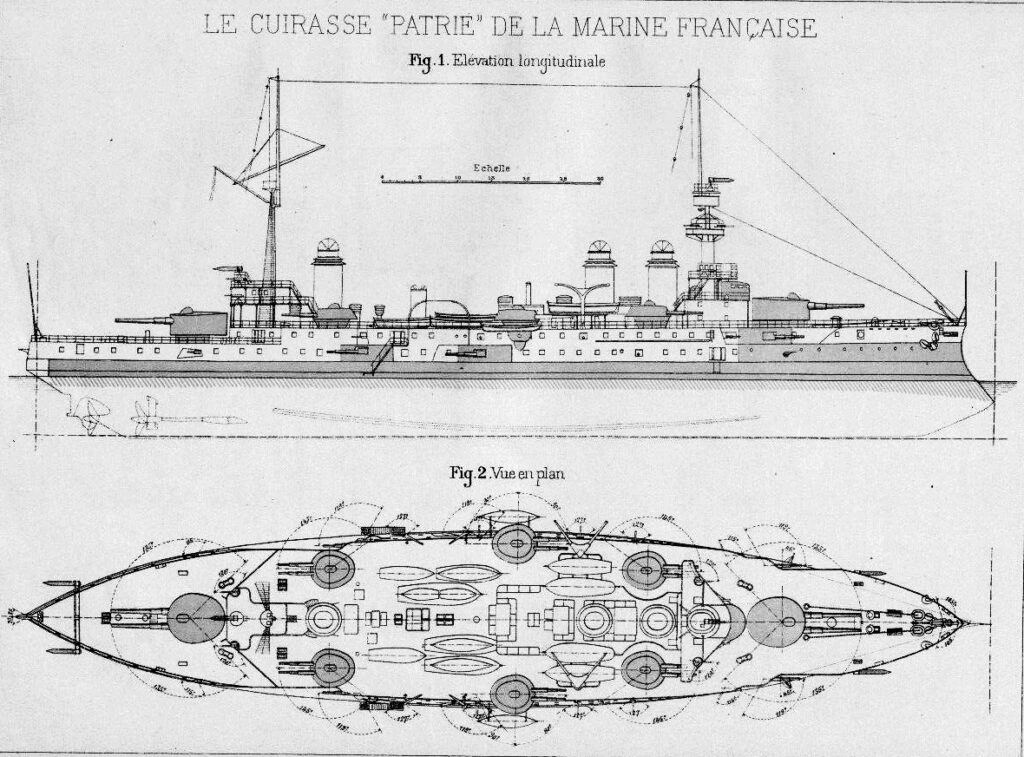

The previous Liberté class design

Then came heated parliamentary discussions over the new design. Cost considerations seemed to be set aside for a moment, as many, especially conservatives, feared that France would being left behind in the technological arms race. Many pointed out the British adoption of the innovative Parsons steam turbines, previous though impossible for ships of a battleship size. In the end, the Marine Nationale sent a technical mission to Parsons and visited several shipyards and gun factories. One stop was the Barr & Stroud rangefinder factory in May 1906 as France was also left behind in terms of fire control.

But among all possibilities, the French looked at the turbines as their solution to the speed problem of the new battleships they projected.

Indeed, given the weight of the boilers of the time, there was no way to reach greater speed with extra boilers and compensate for their own extra weight. The greater speeds were seeked after, the more output was requied, soon offset by extra weight in a defavourable curve. Mathematically this was a loosing battle.

But the turbines shown to the French changed everything. They offered far more power in a much smaller package. Sure, their consumption was abysmal, especially at low speeds, but it was believed this was still relevant in the context of the Mediterranean. In between, three months earlier already, the minister had ordered the first two ships from A. C. de la Loire, St Nazaire and their keel was laid down in April 1907. The admiralty board decided to use turbines in July, so already making for multiple design changes early in construction, and ordering sets of Parsons turbines, in very high demand at the time. Since delays amounted and France wanted the tecnology, a licence was acquired to buid them in France instead, but there was an industrial delay to get these designed and built without no previous experience in this technology, added an extra delay.

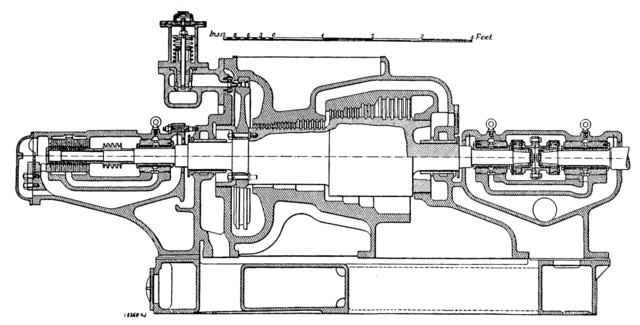

Parsons steam turbine in 1911

Then Minister Thomson requested a study after he was convinced by Schneider (the French Vickers-Armstrong) that they were about do deliver heavier and more powerful 45-caliber 305-millimeter Modèle 1906 gun. The decision was taken on 3 August, while at the same time her rejected the navy’s decision to use turbines. On 6 October 1907, the director of naval construction, M. Dudebout, urgently requested a decision as the ships were already in construction. He also recommende that the first three ships would be completed with triple-expansion steam engines instead not add too many delays, then other three in the FY1908 tranche using steam turbines. This was also asked to void extra spending to modified the previous accepted designs, to accommodate the turbines and a four propeller shaft arrangement. It should be noted that the turbines at the time were three times as expensive as steam engines for only a marginal gain.

Thomson accepted Dudebout’s recommendation, but still took no decision until December, wating for the parliamentary debates. These latter shown a full support both in the majority coalition and even opposition, for turbines, in all six ships. The Contracts for the remaining four ships were signed on 26 December, the very day this debate ended. But Thomson continued to drag his feets on the types of boilers to use and preferred to send another technical mission to Babcock & Wilcox, to study the latest designs cou)pled to turbines, in April 1907, and did not accepted French-built boilers until 3 June 1908, long after the last ships were laid down. All this of couirse triggerred extra delays.

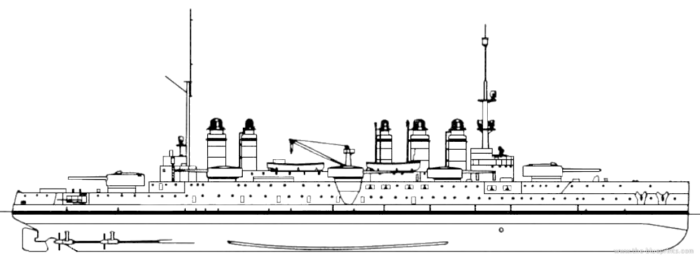

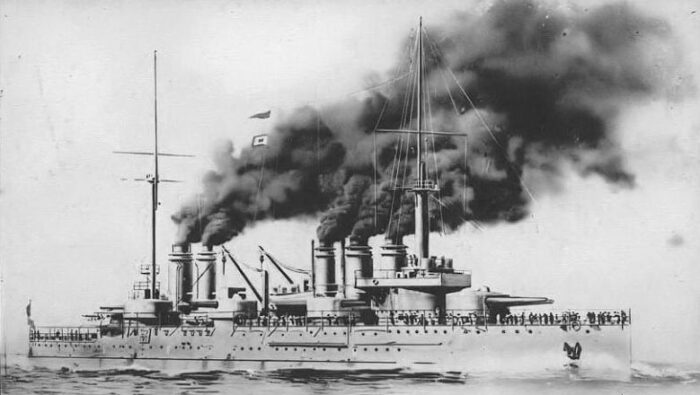

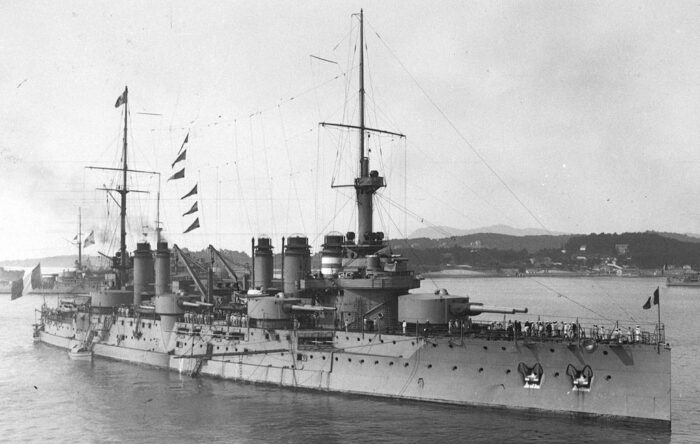

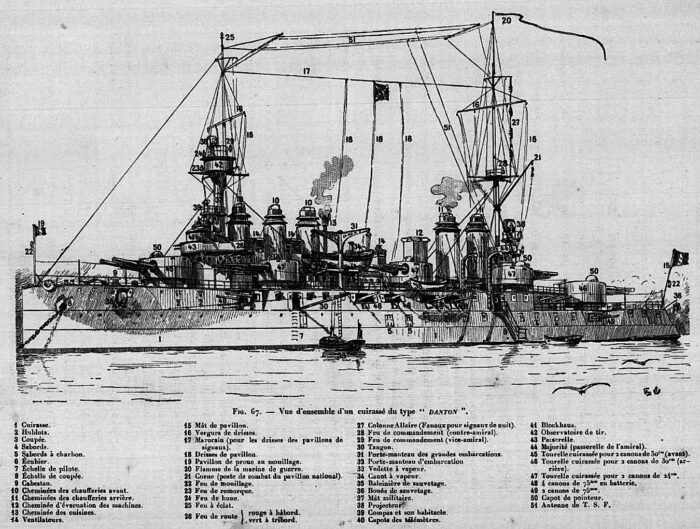

Danton’s basic profile in 1911

The final design was estimated to 18,318 tonnes (18,029 long tons), but this was before the adoption of the new Modèle 1906 gun. For it, a new and larger turret was required, which also obliged to modify completely the supporting structure and reinforced the lower hull supports for these. Again, the yards had to scrap large parts of the completed hulls to access and modified lower decks accordingly. The minister tried to to reduce displacement by having the armor thinned down, and still stick to the original tonnage limitations, but this was exceeded already at estimate stage, and even more when built. The names were chosen in between and following a new Republican tradition, figureheads of the englightment, before the revolution, were chosen.

Design

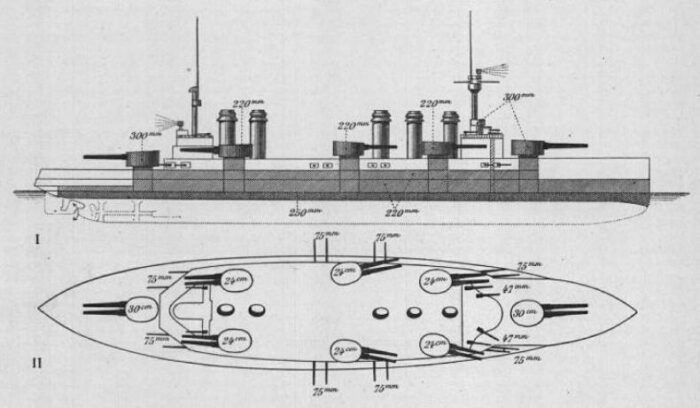

Brassey’s naval annual 1915 – Danton class armour scheme (cc)

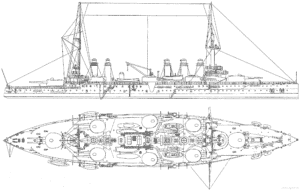

Hull and General Layout

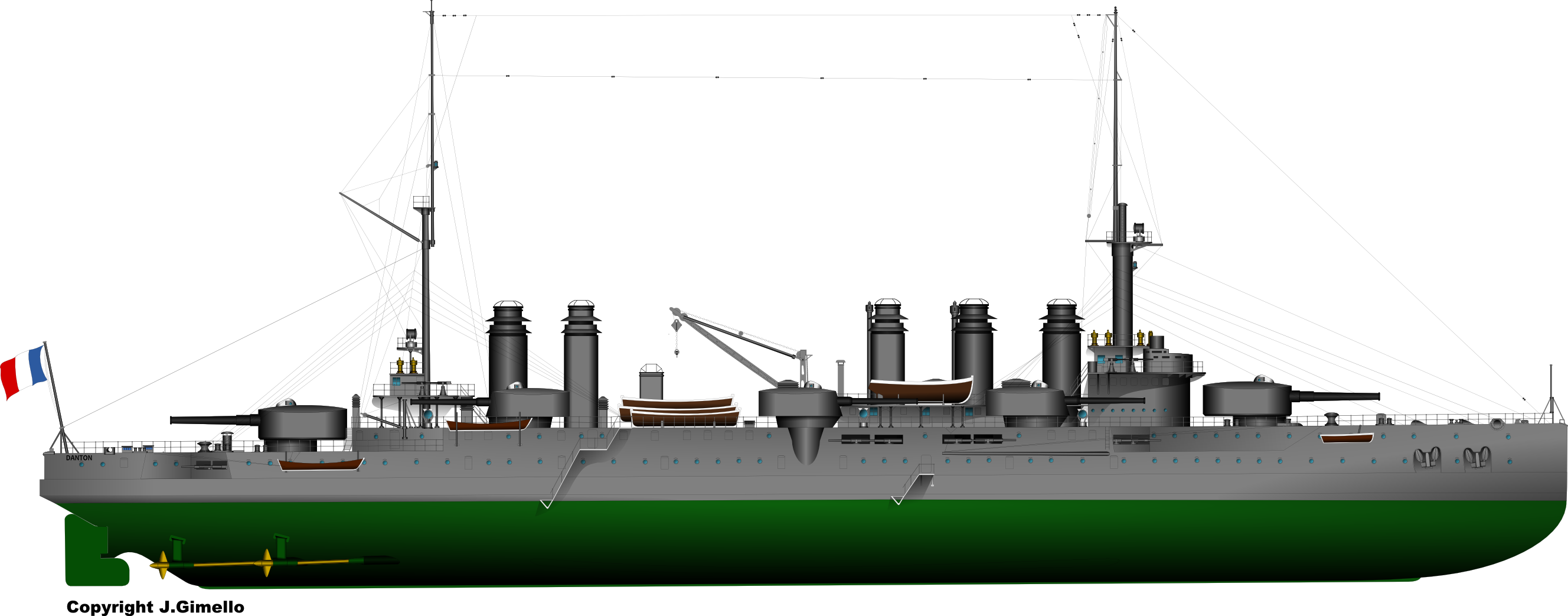

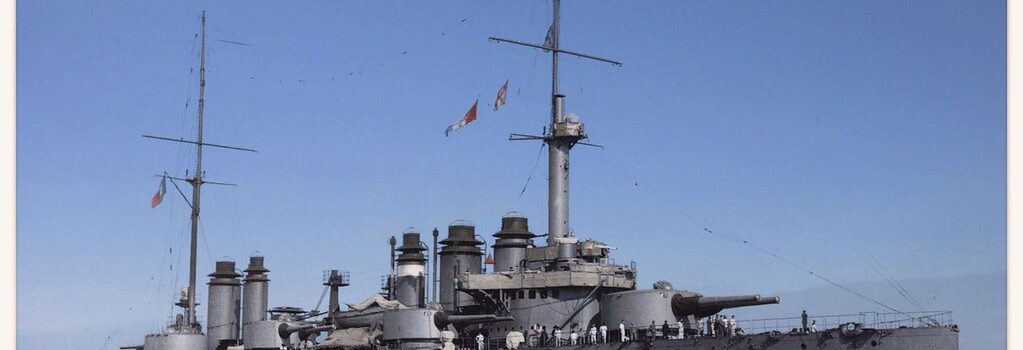

The Dantons as chosen were significantly larger than their predecessors. Their hull was much stretched out to accept heavier secondary turrets, to 145 meters (475 ft 9 in) long at the waterline and 146.6 meters (481 ft) overall. That was a 13 meters (42 ft 8 in) increase. The beam progressed as well, up to 25.8 meters (84 ft 8 in) versus 24.25 m (79 ft 7 in). Draft went to 8.44 meters (27 ft 8 in) at deep load from 8.2 m (26 ft 11 in). These battleships ended slightly overweight with a final displacement of 18,754 metric tons (18,458 long tons) under normal load, 4,000 tonnes (3,900 long tons) more than the Liberté class. When acting as flagships, they had 40 officers and 875 ratings, and down to 28 officers and 824 ratings in normal conditions, versus 32+710 on the Libertés.

The general profile was also very different. They still had a taller forecastle, two storey aft deck, two military masts, with the formast being thicker, but not topped by heavy fighting structure and instead light projectors. There was a spotting top, and the aft last was a bit taller and a pole, also supporitng wireless telegraphic cables. The two bridge and aft strutures were tall, they renounced to any tumblehome and had no ram bow, instead a straight prow, that would became standard on next French Battleships. The base of the bridge was still in horseshoe, with a conning tower and bridge above, two cranes amidshipn, abaft the two middle seocndary turrets to managed a fleet of 18 boats (6 between funnels, 4 forward abaft funnels, 4 under davits forward, 4 under davits aft). They also had two anchors port, one starboard, plus two rear secondary anchors. But the biggest change of all, reflected by their numerous boilers, was the instalation of five funnels instead of three, three forward, two aft, all cyindrical and of various dimensions. Only the light artillery was carried in hull casemates, four firing forward, four aft, eight broadside.

Powerplant

It was decided to purchase directly four license-built Parsons direct-drive steam turbines for each ship, rather than waiting for French ones to be buolt, albeit they were assembled in France in France under licence. Each drove a single propeller. That was a considerable change over a tradition of three shafts and required many designs changes once the choice was made to the hull’s underbelly structures. Steam came from 26 coal-fired Belleville or Niclausse boilers. This was more than 22 Niclausse used by the Liberté class and explained the five funnels.

Boiler alteanated on three ships of each batch. They were housed in two large compartments for safety. In all, 17 were placed the forward boiler room, exhausted in three forward funnels. Nine were located in the aft boiler room and exhausted through the last two funnels. The turbines were located amidships, between the boiler rooms in three compartments. The center engine room housed two turbines dirving the inner shafts. The outer compartment, narrower, housed a turbine each to drive the outer shafts. They were rated at a total of 22,500 shaft horsepower (16,800 kW). The boilers had a working pressure of 18 kg/cm2 (1,765 kPa; 256 psi).

The ships were tailored for a top speed speed of 19.25 knots (35.65 km/h; 22.15 mph). They exceeded these fifures in sea trials, from 19.7 to 20.66 knots (36.5 to 38.3 km/h; 22.7 to 23.8 mph) but this was still less than the 21 knots of the Dreadnought. It happened later than the Niclausse boilers adopted for Condorcet, Diderot, Vergniaud were not well suited to be coupled with steam turbines and burned far more coal than Belleville boilers (On Danton, Mirabeau, Voltaire). This went with a lot of smoke and spark or flames from incomplete combustion. In all, the ships carried 2,027 tonnes (1,995 long tons) of coal, a figure that brough them close to an estimated range from 3,120–4,866 nautical miles (5,778–9,012 km; 3,590–5,600 mi) at 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph) but this was depending on boilers. It seems that 3370 nm at 10 knots was the norm for Niclausse ships. And endurance that was almost half that of the Liberté (8,400 nautical miles (15,600 km; 9,700 mi) at 10 kn (19 km/h; 12 mph)) due to the uneconomical fuel consumption at low speeds as predicted. This severely reduced their utility in the Atlantic and condemned them to the Mediterranean theater.

Armament

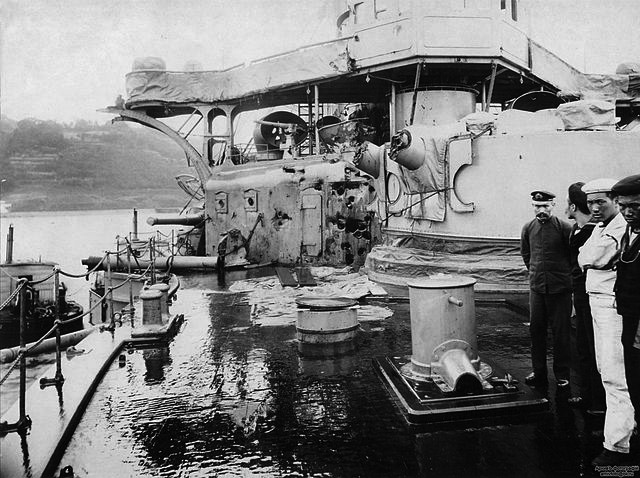

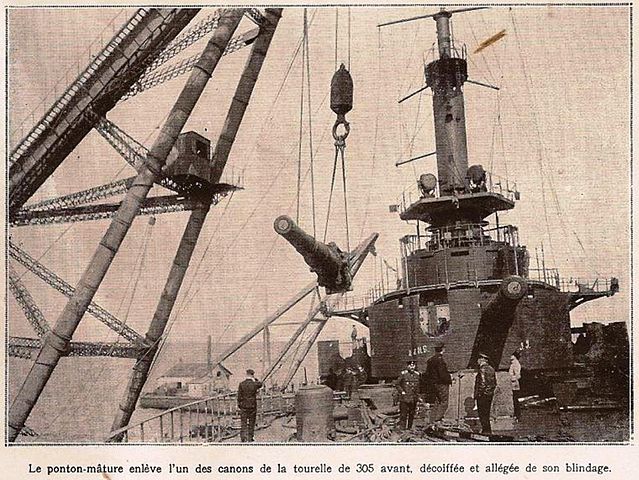

Mirabeau’s 305mm gun being replaced at Sebastopol in 1919 – src Forum Histoire aviation marine – L’Illustration n°3983 09/08/1919

Main: 2×2 305mm/45 M1906

The Schneider 305 mm Modèle 1906 guns were mounted in two twin-gun turrets, fore and aft of the superstructure. More on these

Specs:

Elevation +12°, range 14,500 meters (15,900 yd).

Shells: 440-kg (970 lb) AP, muzzle velocity 780 m/s (2,600 ft/s)

Rate of fire 1.5 rounds per minute.

Supply: Eight ready rounds, rear turret wall. Propellant between the floor of firing chamber, bottom.

75 rounds per gun, with marging of additional 10 rounds.

Secondary: 6×2 240mm/50 M1902/06

Twelve 240mm/50 Modèle 1902 guns in six twin-gun turrets, three per side. They were unique to the Danto class, never used for anither ships. Full specs on navweaps It should be noted that these guns ended in fortifications and shore batteries in the interwar, at Gorée and Vũng Tàu notably, still usable in the war of Vietnam. In WW1, there were two at Verdun, Fort Vaux.

Specs:

Elevation +13°, range of 14,000 meters (15,000 yd)

Shells: 240-kilogram (530 lb) AP or HE. mv (AP) 800 m/s (2,625 fps).

Rate of fire: 2 rounds per minute.

Supply: 12 shells, 36 propellant charges in turret

80 rounds per gun, 100 rounds in case of war.

Tertiary: 16x 75mm/63 M1908

Sixteen 75-millimeter (3 in) Modèle 1908 Schneider guns. They were mounted in unarmored embrasures, or casemates, in the hull sides, four forward firing through cutouts, four aft at the prow and five on the broadside forward of the amidship gun barbette. More on these

Specs:

Weight 3,200 lbs. (1,450 kg), Length oa 191.2 in (4.857 m).

Elevation: 25°. Range: 8,000 meters (8,700 yd) mv 2,789 fps (850 mps)

Shell: HE: 14.1 lbs. (6.4 kg), 9.6 in (24.2 cm)

ROF: 15 rounds per minute.

Supply: Shell hoists being slow and hard to handle (three-round cases, 7 rpm), 576 rounds were stored close to the guns, in ready-use lockers.

Each gun had 400 rounds, max 430 rounds in wartime.

Tertiary: 10x 47mm/50 M1902

Typical Hotchkiss (3-pdr). They were placed in the bridge’s wings and structures for and aft.

The tertiary armament was singularly reinforced at the beginning of the great war: Indeed in addition were fitted twelve 75 mm mounted on the turrets which sufficient elevation and caliber to be used as AA weapons.

During the war, extra 75 mm AA guns were installed on the roofs the two forward 240 mm gun turrets and in 1918, the mainmast was shortened to fly a captive kite balloon. The most important change was the elevation of the 240 mm guns, increased by modifying the mounts and baskets, extended their range to 18,000 meters (20,000 yd).

Torpedo Tubes and Mines

These ships also carried six Modèle 1909R torpedoes (114 kg (251 lb) warhead, 3,000 meters (3,300 yd) at 28 knots (52 km/h; 32 mph) or 2,000 meters (2,200 yd) at 33 knots (61 km/h; 38 mph) settings. There was also a storage space for 10 Harlé Modèle 1906 mines (explosive charge of 60 kgs (130 lb)).

Armor

Total weight of the armor accounted for 36%, so 6,700 metric tons overall. This was still sub-par compared to British and especially German battleships however, more in line with Italian designs, but that was still 1,200 metric tons (1,200 long tons) more than their predecessors.

Waterline Belt: 250 (270mm) amidships (9.8 in), tapered down to 180 mm (7.1 in) (other sources 150mm/6 inches) at both ends, backed by 80 mm (3.1 in) teak.

Belt composition: 2 strakes, 4.5 meters (14 ft 9 in) above, 1.1 m (3 ft 7 in) below waterline.

Lower belt connection to the armour deck: Tapered down to 80–100 millimeters (3.1–3.9 in)

Bulkheads: 200mm (7.9 in) transverse stern. 154 mm (6.1 in) fwd, connected to the sides of the forward barbette.

Upper belt: 48 mm (2 inches).

Main turrets: 340 mm (13.4 in) of frontal armor, 260 mm (10 in) sides, roofs 2x 24 mm (0.94 in) mild-steel plates.

Barbettes: 246 mm (9.7 in) down to 66 mm (2.6 in) below the upper deck.

Secondary turrets: 225 mm (8.9 in) front, 188 mm (7.4 in) sides, 3x 17 mm (0.67 in) roof.

Secondary barbettes: were protected by 154 to 148 mm (6.1 to 5.8 in).

Conning tower: 266 mm (10.5 in) forward, 216 mm (8.5 in) sides. Other sources: 300 mm (12 in)

Communication tube: 200 millimeters thick.

Protected decks*: Waterline and weather decks, formed from triple layers of mild steel, 15 mm (0.59 in) or 16 mm (0.63 in) for 48 and 45 mm total.

*Called “pont blindé supérieur” and “pont blindé inférieur”.

ASW protection:

Anti-torpedo bulge: 2 m (6 ft 7 in) deep below waterline.

Backing: Torpedo bulkhead, 3x 15-millimeter armor plate.

Inboard bulkhead: 16 watertight compartments, 12 kept empty, 4 abreast the boiler rooms as coal bunkers.

It should be noted that if relatively adequate in 1900 against 12 or 18 inches torpedoes, this system was useless against modern 533 or 21 inches torpedoes as shown by the fate of Danton which capsized in 40 minutes after two torpedo hits. Voltaire survived her two hits however.

Propulsion

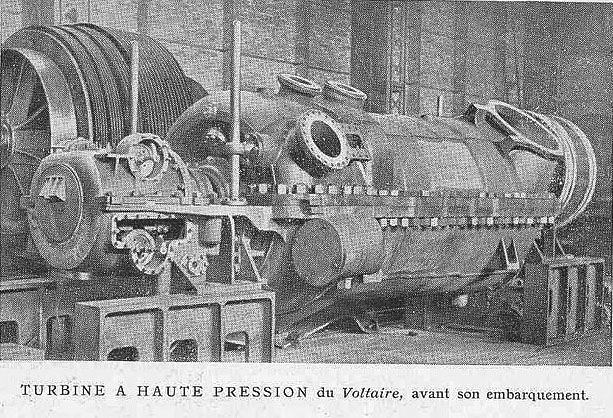

Voltaire’s Turbine before installation

Each ship was fitted with four license-built Parsons direct-drive steam turbines. The steam was drown from 26 coal-fired Belleville or Niclausse boilers, each type being alternated on groups of three ships of the class. They were housed in two large compartments, 17 forward, 9 aft boiler room corresponding to the numerous funnels. The turbines developed 22,500 shaft horsepower (16,800 kW) total using steam at a working pressure of 18 kg/cm2 (1,765 kPa; 256 psi).

Maximum speed as designed was 19.25 knots (35.65 km/h; 22.15 mph), but at sea trials they reached from 19.7 to 20.66 knots (36.5 to 38.3 km/h; 22.7 to 23.8 mph). Niclausse boilers burned however much more coal than Belleville boilers and copious amounts of smoke and sparks, even flames from incomplete combustion. Estimated range from 3,120–4,866 nautical miles (5,778–9,012 km; 3,590–5,600 mi) at 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph) was almost half that of their predecessors and they needed frequent coaling stops during the war.

Construction

Condorcet was built at A. C. de la Loire, St Nazaire, Danton at Arsenal de Brest, Diderot at Chantiers de Penhoët, St Nazaire, Mirabeau at Arsenal de Lorient, Vergniaud at A. C. de la Gironde, Bordeaux, and Voltaire at F. C. de la Méditerranée, La Seyne-sur-Mer. The ships were named after French Enlightment era statesmen and writers.

Construction was prolonged by a number of factors, an old illness typical of French constrcution at the time. There were some 500+ changes made to the original design though various navy ministers, compounded by the inability of the chief engineer to make timely decisions. In the end, the builders had to rip out some completed sections to incorporate these modifications, costing a lot and delaying further shups that should have been completed in 1909, not 1911. Shortagesa and bottlenecks in shipyards, delays in delivery, labor shortages and strikes only added to the mysery. As for the next class of true “dreadnoughts”, they were condemned to wait, due to the lack of large building slips in existing dockyards.

This underfunding of infrastructure over 30 years explains in part many shortcomings of the Jeune Ecole designs, and the issues to launched the first French dreadnoughts, as well as why they remained limited and one generation behind. The root of this problem had been in part that the state considered infrastructures as shipyard’s problems, not willing to invest in these, and was not helped by political instability. Even if political will to invest in these new sliplay was there, frequent minister changes doomed all long term decisions. Add to this, there was the problem of inland yards, the majority of Frenc shipyards were sometimes indeed deep inside waterways, which were often found right in the middle of cities and industrial areas that would need to be expopriated at great cost. Needless to say, shipyard had no power to do such expropriations, it was a political decision.

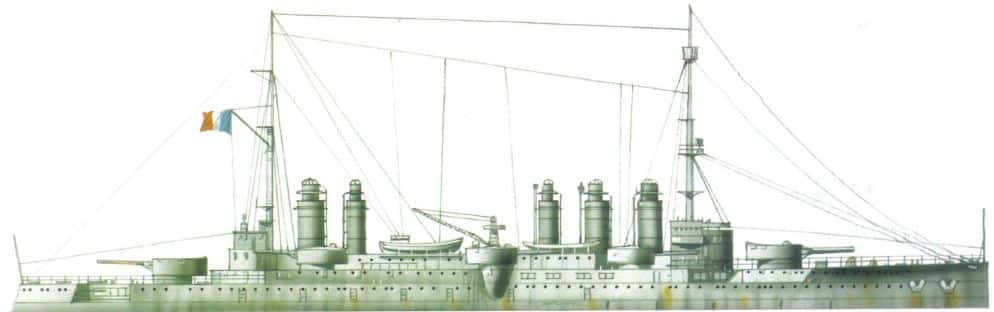

Profile of the class.

Author’s illustration of Danton class battleships

⚙ Danton class specifications |

|

| Dimensions | 146,6 x 25,8 x 9.20 m |

| Displacement | 18 320t, 19 760t FL |

| Crew | 681 |

| Propulsion | 4 screws, 4 Parsons turbines, 26 Belleville/Niclausse boilers, 22 500 hp. |

| Speed | 19,6 knots. max. (40 km/h; 25 mph) |

| Range | 4,600 nmi (8,500 km; 5,300 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Armament | 4 x 305 mm, 12 x 240 mm, 17 x 75 mm, 10 x 47 mm et 2 TT sides 457 mm |

| Armor | Belt 300, turrets 300, blockhaus 300, barbettes 170 mm, Decks 75 mm |

Evaluation

Danton’s class career was not spectacular, the Danton being the only recorded loss, torpedoed by the U-64 off Sardinia, while the Voltaire survived in 1918 to those of the UB-18. These ships fired warning shots at the Greek government in Athens to force the Greeks to rally to the allies. The same vessels (Diderot, Vergniaud, Voltaire, and Mirabeau) formed the squadron of the Aegean Sea alongs with dreadnoughts, deployed against the Austro-Hungarian fleet. On November 13, 1918, they were stationed in Constantinople. After the war, Vergniaud and Mirabeau set out for operations in the Crimea in 1919, bombing Sevastopol in the hands of the “reds”. But Mirabeau underwent a storm and was stranded, but saved and towed back to dock in 1919. Never repaired, she served as a pontoon for experiments, while the others undergone some modernization in 1922-25. This particularly concerned underwater protection, with fitting of bulges. These three ships (Condorcet, Diderot and Voltaire) spent the rest of their career as school ships.

Condorcet was removed from the lists in 1931 but still served as a training ship for torpedo boat crews, cleared of its armament but equipped with 4 Torpedo tubes on its deck, and was extant in Toulon in 1939. In November 1942 she was scuttled like the rest of the fleet, but remained afloat and was later repaired as a pontoon. In 1944, she was struck by an raid raid. She was towed and sunk by the Germans at the entrance of Toulon harbor and, after the landings in Provence, refloated. She was finally stored before demolition, which took place in 1945.

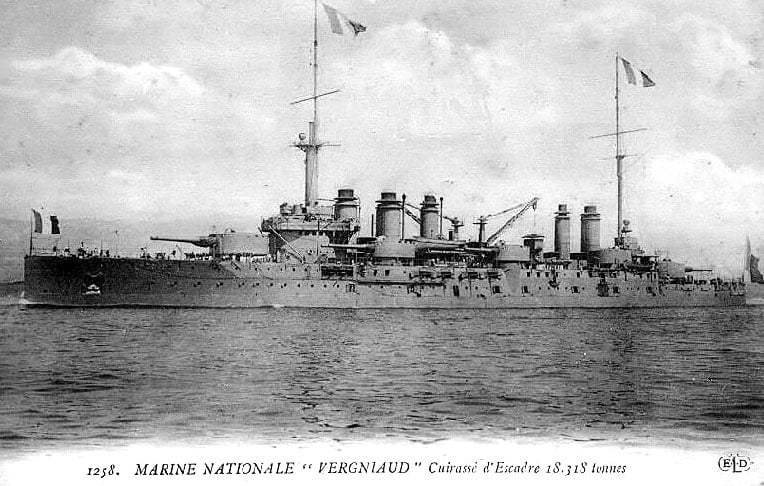

Vergniaud at Toulon, Potcard ELD editors (Eugène Le Deley) (cc)

Voltaire had been converted into a pontoon since 1930, and was definitively condemned in 1935, but sold for scrap only in 1939. The Vergniaud served as a target ship after 1921 and was scrapped In 1929. Finally, the Diderot also served as a pontoon, condemned in 1936 and srapped in 1937.

The Danton class in Action

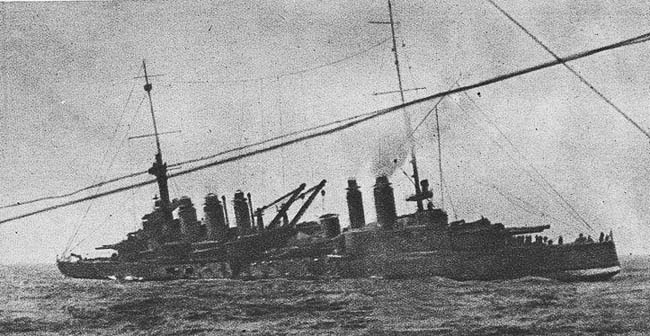

Condorcet (1909)

Condorcet (1909)

Construction of Condorcet was ordered on 26 December 1906 to Ateliers et Chantiers de la Loire, Saint-Nazaire. But she was laid down on 23 August 1907 as the design was continuously worked on. She was launched on 20 April 1909 after scores of modifications and only completed by 25 July 1911, after six years. Condorcet was assigned to the 1st Division, 1st Squadron, Mediterranean Fleet as commissioned, trained in 1912, and took part in combined fleet maneuvers between Provence and Tunisi (May–June 1913). She was part of a naval review for President Raymond Poincaré on 7 June 1913. She joined the squadron tour of the Eastern Mediterranean in October–December 1913. She took part in grand fleet exercise by May 1914.

In Auugust with her sister Vergniaud and the new Courbet, she tried to locate the battlecruiser Goeben and the light cruiser Breslau signalled in the Balearic Islands. On 9 August she was in the Strait of Sicily, trying to precent their escape through Gibraltar as Britanin was still not at war with Germany. On 16 August 1914 she was part of a combined Anglo-French Fleet under overall command of Admiral Auguste Boué de Lapeyrère for a sweep in the Adriatic Sea against the Austro-Hungaraian Navy. They gunned down SMS Zenta at the Battle of Antivari. Condorcet took part in several raids into the Adriatic and patrolled the Ionian Islands, to prevent a Turkish sortie from the Dardanelles. From December 1914 to 1916, she ws part of the distant blockade of the Straits of Otranto, from Corfu. On 1 December 1916 she ws part of the allied fleet in Athens pressuring the Greks to join the entente and for Allied operations in Macedonia. She was transferred to Mudros to prevent Goeben from breaking out, remaining there until September 1917. She ended in the 2nd Division, 1st Squadron in May 1918, in Mudros.

From 6 December 1918 to 2 March 1919, she was part of the Allied squadron in Fiume (Yugoslav question). Next she was in Channel Division. She was modernized in 1923–24 (better underwater protection, four aft 75 mm guns removed). She entered the Training Division at Toulon and notabky she housed the torpedo and electrical schools. She had a torpedo tube fitted on the port side of her quarterdeck for demonstrations. She was partially disarmed in 1931 (London treaty), converted into an accommodation hulk. In 1939 she had her propellers removed. By April 1941 she was used to test the propellant used on the battleship Richelieu, which had one gun detonating at the Battle of Dakar on 24 September 1940. Shots were fired from her aft turret by remote control clearing the propellant. In July she hosted the signal, radio and electrician’s schools with new berthing areas built at the base of the funnels, removed previously. She had the latest radio equipment installed. On 10 September 1941 she was rammed by the submarine Le Glorieux by accident. This flooded one compartment, she was drydocked for repairs and captured intact by the Germans on 27 November 1942. She was then used by the Germans as a barracks ship, but bombed by the Allies in August 1944 (Anvil Dragoon), scuttled. Some 240 mm guns ended in a battery on the north bank of the Gironde estuary, Bay of Biscay. Salvaged in September 1945 she was sold for BU on 14 December, completed by 1949.

Danton (1909)

Danton (1909)

Named after George Danton, a lawyer and Revolution statesman, she was laid down at the Arsenal de Brest in February 1906 with a launching scheduled for May 1909, but anarchist workers prevented it to happen. She was launched on 4 July 1909, completed and fitted-out, then commissioned on 1 June 1911. A week after she sailed t the UK, taking part in the Coronation of George V’s naval review. She was assigned to the 1st Battleship Squadron in April 1912 with her sisters.

While sailing off Hyères, Mediterranean, she suffered an gun explosion in a turret, killing three men, injuring several others. It was attibuted a misuse of probably decaying powder charges. In 1913, she was joined by two dreadnoughts, Courbet and Jean Bart in unit.

Her career in World War I remained with the Mediterranean Fleet from August 1914, guarding convoys bringing French troops back home from North Africa, and looking for the battlecruiser SMS Goeben in the area, which in effect bombardeded the coast. The squadron changed command, for Vice Admiral Chocheprat. By 16 August, this was Admiral de Lapeyrère, and he sailed from Malta to the Adriatic to blockade the Austro-Hungarian Navy, resulting in the action of Antivari.

While under command of Captain Delage she was torpedoed by U-64 (Kapitänleutnant Robert Moraht) at 13:17 on 19 March 1917, 22 miles (19 nmi; 35 km) SW of Sardinia while returning to duty from a refit in Toulon, underway to Corfu for the Allied blockade of the Strait of Otranto. She carried rotational extyra members to replenish crews of other ships at Corfu as well. The U-boat threat was well known and she was seen zig-zagging. She received two torpedo hits rresulting in an uncontrollable flood, slow down still for 45 minutes, enabling 806 men to make an orderdly escape and being rescued by the destroyer Massue and patrol boats. Still, 296, including Captain Delage went down with her. Massue also attacked U-64 with depth charges and oreventd another attack. The wreck was rediscoeved in February 2009, “in remarkable condition” during an underwater survey between Italy and Algeria to built the GALSI gas pipeline, under 1,000 metres (550 fathoms; 3,300 ft), stting on the bed upright, turrets all in place.

Diderot (1909)

Diderot (1909)

Named after Denis Diderot, a writer and philosopher of the enlightment, Diderot was laid down at A. C. de la Loire in St Nazaire on 20 October 1907, launched on 19 April 1909 and completed in 25 July 1911. She was assigned to the 1st Division, 1rst Squadron of the Mediterranean Fleet, taking part in combined fleet maneuvers in May–June 1913 and the naval review for Raymond Poincaré on 7 June 1913. She was part of the tour of the Eastern Mediterranean in October–December and was at a grand fleet exercise by May 1914.

In August she was in the Strait of Sicily to intercept Goeben and Breslau. On 16 August 1914 under an Anglo-French Fleet she was part in the raid of the Adriatic Sea and sinking of SMS Zenta, escorted by SMS Ulan (which escaped) off Montenegro. She took part in several raids into the Adriatic and Ionian Islands and until 1917, was in the distant blockade of the Straits of Otranto from Corfu. In May 1918, she was flagship of the First Division, 2nd Squadron, based in Mudros with Mirabeau and Vergniaud. They were to prevent a sortie of Yavuz (Goeben) until November.

After the Armistice of Mudros on 30 October she took part in the occupation of Constantinople (12 November-12 December) and was based in Toulon by 1919, modernized in 1922–25, TS from 1927 to free battleship tonnage (Dunkerque class), condemned on 17 March 1937, sold for BU 30 July, starting 31 August.

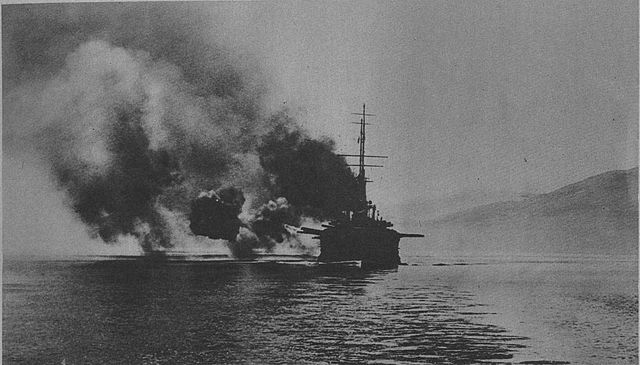

Mirabeau (1909)

Mirabeau (1909)

Mirabeau bombarding Athens – Src Le Miroir numéro 162 page 9 – 12 December 1916 (cc)

Named after the Comte de Mirabeau, an important figure of the French parliament in the revolution, she was laid down at Arsenal de Lorient in Lorient on 4 May 1908, launched on 29 October 1909 and completed 1 August 1911, faster than her sisters. She arrived at Toulon on 15 August, became flagship, Rear Admiral Dominique-Marie Gauchet, Mediterranean Squadron, 2nd Division, 1st Battle Squadron with four sisters. She was part of the naval review for Pdt. Armand Fallières off Cap Brun on 4 September and was visited by the navy Minister, Théophile Delcassé.

By mid-April 1912, her squadron hosted three British armored cruisers at Golfe-Juan under Rear-Admiral Edward Gamble, which unveiled monuments to King Edward VII and Queen Victoria at Cannes. Mirabeau was in July maneuvers, Western Mediterranean and simulated blockade of Ajaccio in November. On 3 March 1913 she was in gunnery off Hyères Is. with Winston Churchill in attendance. She took part in combined fleet to north africa in May–June and the review for Raymond Poincaré on 7 June. Her uni fell under command of Rear Admiral Marie-Jean-Lucien Lacaze from 16 August and she was part of an Eastern Mediterranean tour this winter, visiting Egypt, Syria, and Greece.

Lacaze moved to Voltaire on 12 March 1914 as she had to leave for engine repairs. During the July Crisis, she unloaded practice ammunition and dumpled lots of old propellant for new ones from 27 July and recoaled before the mobilization on 2 August. Two days later under Augustin Boué de Lapeyrère in the 1st Naval Army she was sent to the Algerian coast to escort troop convoys and waited for SMS Goeben after their raids on Bône and Philippeville. Her machinery problems limited her however to 15 knots, slowing the whole squadron, whuch could have intercepted otherwise Souchon’s ships. Vice Admiral Paul Chocheprat ordered them westwards instead. Mirabeau left repair for a sortie in the Adriatic, and patrols off Greece and the Italian coast to bar a breakout. After Jean Bart was torpedoed on 21 December by U-12 she was withdrawn to Navarino Bay. On 11 January 1915 the fleet was alerted of a sortie from Pola (false alarm). She patrolled the Ionian Sea. With Italy at war from 23 May she was sent to Malta, alternated with Bizerte in Tunisia and the Otranto Barrage. She was in Malta on 30 June when a torpedo exploded in a nearby warehouse but was lightly damaged, 2 men killed, 11 wounded.

By November 1916, brought landing parties to Athens which in December, took part ina presure move for the Greeks to Allied operations in Macedonia. For good measuren, Mirabeau fired four rounds into the city, one landing near the Royal Palace. She was based all 1917 in Corfu and Mudros to block Yavuz. In August she tested a tethered balloon. By April 1918 she was in Mudros and was reassigned to the 2nd Squadron, 1st Division. She took part in the occupation of Constantinople from 12 November, and was deployed to the Black Sea to support White Russians in Sevastopol but ran aground during the 18 February 1919 dnowstorm on the Crimean coast, refloated after 6,000 metric tons were removed, notably her guns, turret and upper belt armour, boilers, and coal. Several weeks were needed until 6 April. She was towed by Kagul and Thernomore to a drydock in Sevastopol for repairs and be reequipped. But was caught by the red advance on the city and her guns, ammunition and part of her armor was in placed on 5 May, so she was towed to Constantinople by Justice and five tugs. She was then towed to Toulon on the 24th and was stricken on 22 August after inspection, hulk sold and towed to Savona, U from 28 April 1922.

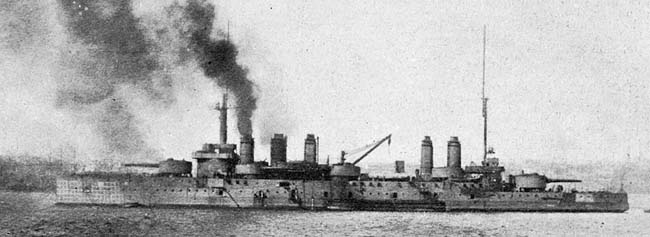

Vergniaud

Vergniaud

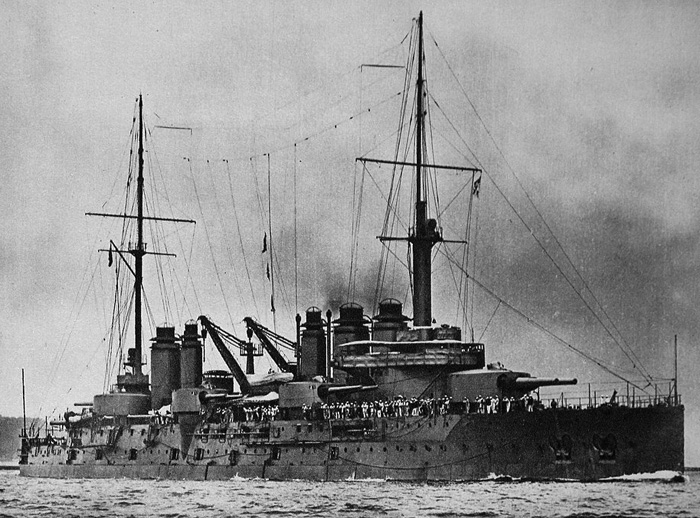

Battleship Vergniaud during a during a naval drill in Toulon, May 1914. Gallica – Agence Rol Src (cc)

Named after Pierre Vergniaud, a prominent member of the revolutionary assembly, she was laid down at A. C. de la Gironde in Bordeaux on July 1908, launched on 12 April 1910 and completed on 18 December 1911. Total cost was 55,247,307 francs. She was in the 1st Division, 1st Squadron and took part in combined fleet maneuvers by May–June 1913, naval review before Raymond Poincaré on 7 June and tour of the Eastern Mediterranean until December, then grand fleet exercise in May 1914. In the summer with Condorcet and Courbet, she searched for Goeben, escorted troop convoys and sailed to Malta. On 16 August 1914 she departed for the Adriatic, a sweep that claimed SMS Zenta at Antivari. Later she bombarded Cattaro on 1 September to try to lure out the Austrians, and blockaded the Strait of Otranto until August 1915 alternating between Malta and Bizerte and was sent to Toulon for a refit;

She was transferred to the 2nd Squadron on 27 March 1916, but remained in the Otranto blockade from Argostoli and Corfu as well as the Allied intervention in Athens by December 1916. However the lieutenant in charge of her landing party was killed in the incident. She was given a short refit at Toulon (9 November 1917-January 1918) and back to Corfu, then Mudros in May, but suffered a boiler burst on 14 September (4 killed, 9 wounded). She took part in the occupation of Constantinopla and returned to Toulon on 17 December.

By early 1919 she was back in action off Sevastopol to stop the Soviet forces advancing on the city, but for naught as she helped evacuation Allied troops by April 1919 under Vice-Admiral JF Charles Amet. As he wanted her crew to launch a support on land, a mutiny erupted on Vergniaud and several ships from war-weary sailors which demanded to return home. The whole affait degenerated a mass shooting of sailor demonstrators, one died from Vergniaud. Sailored went so far as unfurling red banners in support of the Bolsheviks and threaten to join them. The 4-day stalemate ended in a victory for the sailors as the ships withdrew to France, herself on 29 April, towing the merchant ship SS Jerusalem to Constantinople. She was based in Beirut from May to August 1919 to monitor Turkish activities off Palestine, Lebanon and Syria and arrived in Toulon on 6 September, in reserve from 1 October. Gioven her inspection, she was decommissioned in June 1921, condemned on 27 October, disarmed in 1922 with niner 240mm guns installed as coastal defence batteries in Dakar, Senegal. In 1940, they forced the Allied fleet to withdraw from the Vichy French (Battle of Dakar). Vergniaud became a target ship, notably to try effects of poison gases and bombs on a battleship until 1926. For disposal on 5 May 1927, she was sold for BU on 27 November 1928. Oddly enough the Soviets remembered the French mutiny and erected a monument to them in Sevastopol, at Morskaïa Square.

Voltaire (1909)

Voltaire (1909)

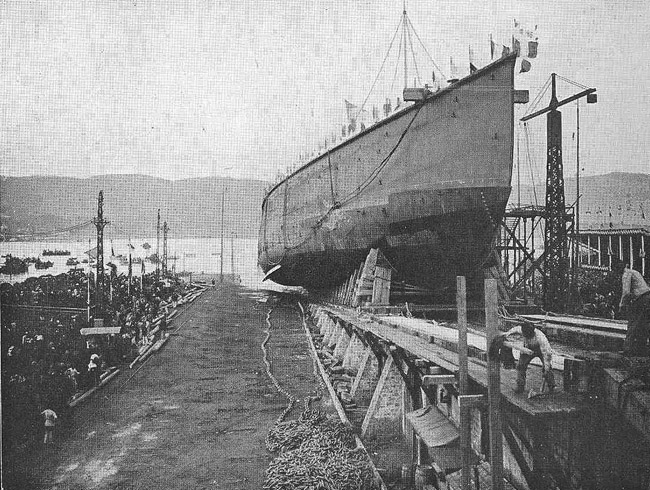

Launch of Voltaire

Named after the famous writer, philosopher, polemist, and major figurehad of the enlightenment (pen name), the battleship was ordered to F. C. de la Méditerranée, La Seyne-sur-Mer on 8 June 1907, launched on 16 January 1909 and completed on 5 August 1911. She entered service in the 2nd Division, 1st Squadron and took part combined fleet maneuvers off Tunisia in May–June 1913 and naval review for Pdt. Raymond Poincaré on 7 June. She took part in a tour of the Eastern Mediterranean by October–December 1913 and grand fleet exercise by May 1914.

By early August 1914 she was off the Strait of Sicily (Goeben escape route).

On 16 August 1914 she made the sweep to the Adriatic Sea and action off Antivari, plus other raids into the Adriatic and Ionian Islands patrols. From December 1914 to 1916 she blockaded the Straits of Otranto from Corfu. On 1 December she sent a landing party to force Athen to join the allied intervention in Macedonia. In 1917 and until April 1918 she was based at Mudros. She was overhauled from May to October 1918 in Toulon and returned to Mudros on 10 October but was torpedoed by by UB-48 while off the island of Milos. There were two hits, but she survived unlike her sister Danton. The ASW prortection and the location of the hits made crew’s effort successful. Sghe was stabilized enough to be temporarily repaired at Milos, sailed to Bizerte and arrived in Toulon. She was modernized in 1922–25 (better underwater protection) and became afterwards a TS (training ship) from 1927 until written off on 17 March 1937, scuttled in Quiberon Bay on 31 May 1938 for long-term use as a surfaced target, wreck only sold by December 1949 BU from March 1950.

Other photos of Voltaire, Agence Rol

Shipbuilder model at the Musee de la Marine, Paris.

Detailed vectorial illustration by J.Gimello ( http://forummarine.forumactif.com/t3541-cuirasse-danton)

Links/Sources

Books

Chesneau, Roger & Kolesnik, Eugene M., eds. (1979) Conway’s all the world fighting ships 1906-1921.

Corbett, Julian (March 1997). Naval Operations to the Battle of the Falklands. History of the Great War: Based on Official Documents. Vol. I. Battery Press.

Dumas, Robert & Prévoteaux, Gérard (2011). Les Cuirassés de 18 000t. Outreau: Lela Presse.

Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One: Guns, Torpedoes, Mines and ASW Weapons of All Nations. Seaforth Publishing.-7.

Gille, Eric (1999). Cent ans de cuirassés français. Nantes: Marines.

Jordan, John (2013). “The ‘Semi-Dreadnoughts’ of the Danton Class”. In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2013.

Jordan, John & Caresse, Philippe (2017). French Battleships of World War One. NIP

Meirat, Jean (1978). “French Battleships Vergniaud and Condorcet”. F. P. D. S. Newsletter. VI (1).

Ropp, Theodore (1987). Roberts, Stephen S. (ed.). The Development of a Modern Navy: French Naval Policy, 1871–1904. NIP

Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World’s Capital Ships. Hippocrene Books.

Links

Amos, Jonathan (19 February 2009). “Danton Wreck Found in Deep Water”. BBC News. Retrieved 19 February 2009.

on navypedia.org

Bretagne class BB on wikipedia

Individual: The Provence

battleships-cruisers.co.uk/

on commons.wikimedia.org/

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign