WW2 USN PT Boats: Overrated Success ?

The “wooden marvels” were known by many names during WW2, but the official and generic “PT-Boat”, meaning “Patrol, Torpedo (Boat)”. They were an unknown type for the USN in WW1, as there was no need for such “naval dust” when a large battlefleet was available mostly to project power. Therefore, it’s the only the conditions of war that urged the need for these small vessels, although the acquisition process started already back in 1938. Three standards emerged from a three years long competition, Elco, Higgins and Huckins. Wooden-built not to tax strategic materials, they were deployed in all theater of operations, not only the Pacific but Mediterranean, and even the Channel. Small, but well armed and fast, they proved able to perform a large variety of missions, but they also paid a heavy price for their dangerous close quarters missions. PT-Boats certainly played their contribution to the allied victory in WW2, but nothing comparable to the rest of the fleet, submarines included.

Modest and relatively inexpensive, PT-Boats’s inflated fame was largely earned in the Pacific, especially in the Solomons and Philippines. They proved able to distrupt traffic within the confines of innumerable islands, lagoons and archipelagos of the Southeast Pacific in close collaboration with US Marines. They were the supreme “jacks of all trades”, from ASW patrol to skirmishing, ground support, spec ops, troop transport, supply, AA cover, and raiding deeply into enemy lines. The “barge busters” also rarely engaged destroyers or even cruisers, but their inflated successes in early 1942 needs to be toned down.

The shining moment of the 800+ PT Boats ever built was “only” the sinking of IJN Terutsuki off Guadalcanal. This was meagre for thousands of sorties, but overall axis losses amounted to hundreds of units sunk and a thousand more or less seriously damaged, most being light vessels. They were also significantly larger than other equivalents of the allies, the small Thornycroft MTBs, MAS from Baglietto or G5s from Tupolev, in fact closer to the British Fairmiles, Italian MSs or Russian D3s.

These generous dimensions and flexibility meant it was possible to install almost “a la carte” armaments and equipments depending of the unit commander’s tasks at hand. They proved modular enough for these quick reconfigurations, and by 1943, all had radars to operate by night. Their flexibility meant they could operate from a great number of bases scattered over the theater of operations, sometimes close to known IJA garrisons or bases. They also earned dedicated ships (converted Barnegat class ships) for maintenance, supply and repairs, ranging from five to 40 PT-Boats depending of the squadrons present. Overall, although not impressive compared to larger ships or submarines, manned by courageous, resourceful crews, they played their part into sometimes seriously disrupting enemy operations, wherever they went, and thus securing their place in the USN while not taxing traditional military yards or using strategic materials.

WWI US Navy MTBs

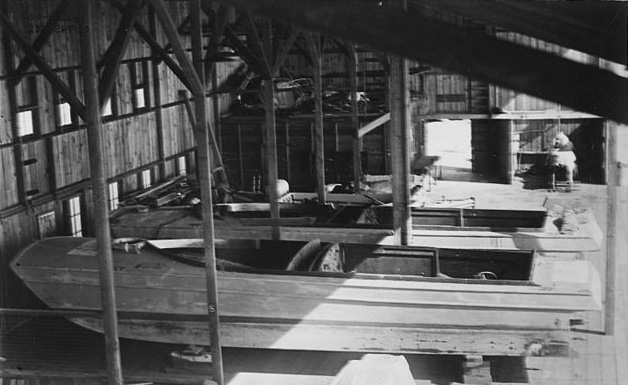

WWI Hickam’s PT Boat

Hickmans’s Sea-sled broadside view in San Diego, California

When the war broke out in August 1914, the US want nothing of an involvement but prospect for possible exports for the belligerents, also covering the USN own needs. William Albert Hickman, a Canadian designersettled in California, wrote for his own initiative procedures and tactics for a fast and agile (and seaworthy!) torpedo motorboat using his system, to be used against battleships and cruisers. This proposal went to Rear Admiral David W. Taylor at the time directing the USN Bureau of Construction and Repair (C&R, later BuShips) and the next month Hickman received a greenlight to draft plans of a 50-footer (15 m) “Sea Sled” torpedo boat, with an inverted vee planing hull (an early form of catamaran, using partly wing-in-ground effects), which he designed, as he was also a small boat builder. He submitted this design to the Navy, hoping of some contract, and in a return letter by Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels, the latter explained he had to reject it, based on the fact the US was not at war, not on technical grounds.

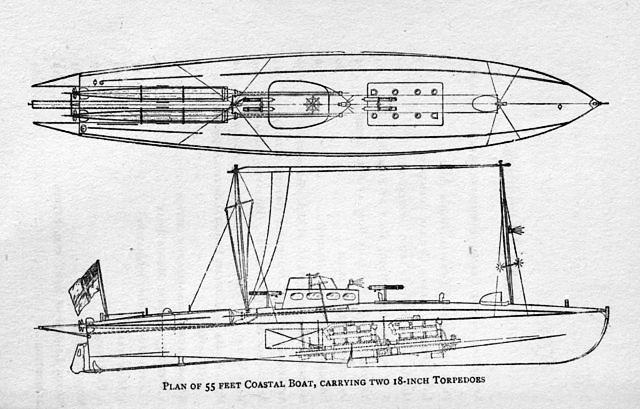

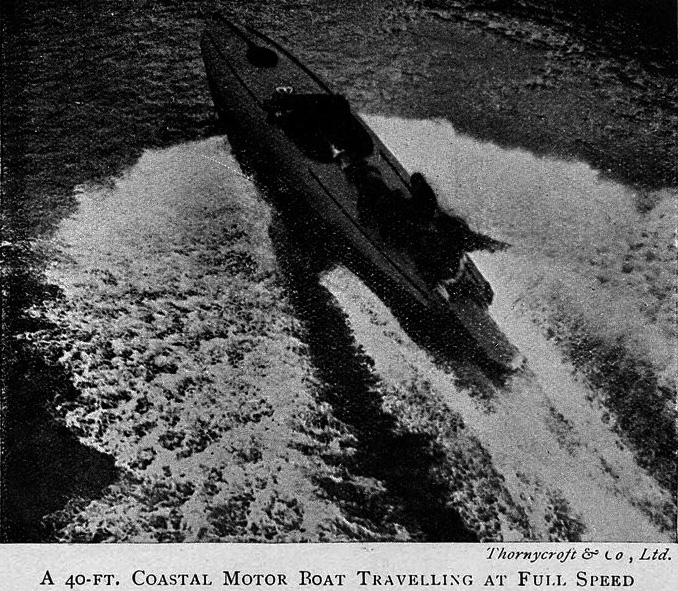

Hickman, undeterred, sent his proposal to the British Admiralty in October, which was interested but expressed doubts that such as small boat, even pushed to 60 feet, would be enough to cope with the north sea. Hickman, still willing to obtain a contract, built on private funding a demonstrator, which was a ’41-footer’ (12 m) carrying a single 18-inch Whitehead Mark 5 torpedo, common at the time. In February 1915, he demonstrated it in a show run at 35 knots (65 km/h; 40 mph), in winter so in rough sea condition off Boston. It was attended by both US and foreign representatives. No contract followed. The British Admiralty representative there however, Lt. G.C.E. Hampden, reunited back home in summer of 1915 the Lieutenants Bremner, and Anson to discuss the possibility of developing such boat at home. They approached John I. Thornycroft for an equivalent, a process that ultimately led to the CMB line or “Coastal Motor Boat” of which a serie entered service from April 1916.

British 1916 CMB, plan and in action

In August 1915 though, the US General Board approved the test of a single experimental small torpedo boat which could carried by rail or a regular steamer on deck. Thie boat, redignated C-250 was awarded not to Hickman but Greenport Basin and Construction Company in New York. Construction took time and it was delivered for official testings by the summer of 1917, but failed to reachs its specs. A second boat designated C-378, based on Hickam’s sea sled design was ordered, from him this time between late 1917 and early 1918 depending on the sources. Hickam just went with his own prototype built in September 1914 crossed with the C-250 designed (when he failed the competition).

C-378 training with a floatplane in 1918, showing it was almost as fast.

This new prototype was C-378 was tested just before the Armistice, which resulted in a cancellation of the whole program (and compehensible frustration of Hickman).

Nevertheless, the Hickman C-378 which weighted 56,000 lb (25,000 kg) reached 37 knots (69 km/h; 43 mph) during trials. This tim, Hockman went for a 1,400 horsepower (1,000 kW) aviation engine, amd long runs maintaining 34.5 kn (63.9 km/h; 39.7 mph), while tossed in winter, braving a northeaster storm, going up through 14 ft waves. For the time, and even to this day, it’s nothing but an achievement for such type of vessel. Despite this there was no utility for it but endless testings. The “Sea Sled” was not forgotten and came back in 1939, being used by the Army and Navy as a rescue boat or a seaplane tender during the interwar.

Interwar Tests

Already in 1922, the US Navy agreed that they needed torky combustion engines for their propulsion, but wanted to test the two CMB types in service in the RoyalNavy at the time: A 45-footer (14 m), and the 55-footer (17 m). They were tested extensively, the larger of the two being put to numerous and various trials until 1930. Nothing followed.

In 1938, as boots noises were heard throughout Europe and in Asia, the rejection of treaties and nationalism at an all-time high, the US Navy looked upon procuring theor own MTBs, at least for testing and defensive purposes. The admiralty sponsored a design competition to small boat builders. The goal was to obtain a highly mobile attack boat, in part inspired by WWI actions, like those of Italian MAS, or British models against the Bolsheviks in 1919. Prizes would be awarded for the winning design, and in 1940, about 12 manufacturers answered with at least a prototype. Canada and Great Britain however would supply the initial needs of the US Navy from December 1941. There was also a perceive need from probable belligerents of an incoming war, which became reality in September 1939.

In 1938 so, the USN restarted an investigation, this time based on the numerous boat builders that flourished before the 1929 crisis and which were still there. They excluded Hickman’s Sea Sled in defining two different classes. They wanted to create a 54-footer (16 m) boat and a 70-footer (21 m) which were more appropriate to be seaworthy. This was strickly restricted to a small cadre of respected naval architects, and the Navy, Hickman nont being among them. More on the topic of the Hickman’s PT

Design development

Original Competition

The competition was published on 11 July 1938, with this time four types defined (two more were added, destined to the same boat builders):

-A 165-foot subchaser (Future PC type)

-A 110-foot subchaser (Future SC type)

-A 70-foot motor torpedo boat

-A 54-foot motor torpedo boat.

The prize for each was set to $15000, including an extra $1500 for those reaching the final competition ring. All designs were to be submitted on 30 March 1939.

-The “70 footer” was restricted to the whole size range until 80 feet. It was able to carry not one but two standard Naval 21-inch torpedoes and four depth charges, with two .50-cal HMG for close protection, and sustain a speed of 40 knots in all sea conditions, and this over 275 miles, or 550 miles at cruising speed, around 30+ knots. These were quite stringent conditions.

-The “54 footer” was restricted to 20 tons for easy transport, 40 knots but 120 miles/240 miles, and armament of two torpedoes plus depth charges and single .50-cal machine-guns, plus a smokescreen generator.

September 1938 arrived (concluding a busy summer!), 24 designs being received for the 54 footer, 13 for the 70 footer.

George Crouch (one of the particpants), which new full well about the merits of Hickman’s Sea Sled design wrote that he esteemed his design far superior to BuShips, until it was specifically excluded from the competition. Three designers for the first, five for the other were retained for the second round of the competition. They were asked to submit detailed plans for their respective boats with a deadline set on 7 November. On March 21, 1939, the final round was concluded. The USN announced that Sparkman and Stephens won the grand prize for the 70-footer category, Professor George Crouch with Henry B. Nevins, Inc. winning for the 54-footer category.

Contracts thus followed, placed to two yards to produce these, in May 25. Sparkman and Stephens (the 70 footer) was asked to scale up their design to 81 feet overall, while Higgins Industries contacted by the Navy on the behalf of Henry B. Nevins, Inc. since they had the capability to deliver the new prototypes PT5 and PT6. On June 8, it’s Fogal Boat Yard that was contracted to built the PT-1 and PT-2 and Fisher Boat Works to built the PT-3 and PT-4 all four for the 54-footer (Crouch design) and Philadelphia Navy Yard (PT-7, PT-8) for two new 81-footer this time in-house designed by BuShips, mainly in aluminum and with no less than four engines.

Later Higgins built a second PT-6 “Prime” of its own initiative. It was completely redesigned by Andrew Higgins using his own methods but incorporating in part (the aft hull section), Hickman’s inverted V design, notably for its landing crafts. They built later the PT-70 incorporating further improvements over PT-6 Prime.

Meanwhile, the Navy went on testing the new boats just delivered. They were gruelling tests, in realistic conditions, and fully armed. This revealed limitations and many issues that had to be solved before even meeting requirements and specifications. The Navy continueed to push for continual improvements until they reach an agreement over the satisfactory working design, one which could be used as standard.

Huckins 77 footer prototype PT-9 in June 1940

At Electric Launch Company (Elco) meanwhile, saw chief engineer Henry R. Sutphen of his team, Irwin Chase, Bill Fleming, and Glenville Tremaine, went to the United Kingdom for ideas in February 1939, at the Navy’s request. They were to be shown British Thornycroft motor torpedo boat designs, proepcting to acquire one which could serve as a backup and to compare US designs. They visited the British Power Boat Company and acquired a 70-footer (21 meter) built as a private venture and called PV70. In British service it became PT-9. It was based on the Hubert Scott-Paine’s racer. This became the prototype for the early Elco PT boats, later to be the main supplier of PT Boats. By late 1939 the Navy contracted Elco, not part of the early competition, to start production of eleven replicas of the PT-9, to be delivered to the navy and tested as a full strenght squadron for naval exercize evaluations.

A third protagonist came about in the second competition (the plywood derby, see later) and this was Huckins Yacht Corp., Jacksonville in Florida. This was a very respected designer and builder of high-end, high performance and luxury boats, among the most reputed any in the jet set and Hollywood could dream to acquire. On 11 October 1940, an agreement between this company and the Navy was drafted and signed, in which the Navy would provide its one military-grade engines, while Huckins was to provide the PT boat for these, and that this one should be offered to the Navy for an undisclosed amount. This was a 72-footer (22 m) internally called MT-72 and after bein acquired, became PT-69, the company only earning $28.60 for it all.

‘The Plywood Derby’

The final chapter of this nearly four year process was a final competition pitting the new competitors between them.

In March 1941 an heavy weather run from Key West to New York by the Motor Torpedo Boat Squadron 2 using Elco 70-footers had to cope wuth up to 10-foot waves even, at moderate speeds, which washed their bow all along, the crew reporting “extreme discomfort” and fatigue, compunded by structural failure with the forward chine guards goned and broken bottom framing as well side planking cracking among others. MTBRON 1 however was very satisfied with the 81-footer Higgins (PT-6), with beter seakeeping. The USN therefore cancelled further Scott-Paine boats purchases while the U.S. Navy Bureau of Ships (BuShips) purchased more Packard engines to equip both Huckins and Higgins boats, building their own prototypes.

There was in May a Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) attended by BuShips, BuOrd, MTBRONs, and Interior Control Board Conference about future PT characteristics. The 77 ft Elcos proved not enough for the task, and it was estimated it would be the same for the 70 ft (21 m) Elco. Comparative tests for evaluation asked for five new design but no more Elco 77-footer.

The Board of Inspection and Survey (Rear Admiral John W. Wilcox, Jr.) conducted these service tests off New London from 21 to 24 July 1941 with the PT-6, PT-8, PT-20, PT-26, PT-69, PT-70 and a British MRB-8 (Motor Rescue Boat) (specs in the detailed review of MTBs).

Each member of the Board conducted an independent inspection between structural sufficiency, habitability, access, arrangement for attack control and communication facilities, in order to keep an objective eye.

They were all tested with weapons loaded, fully equipped (with all torpedoes and depth charges) and fuel for 500 nm/20 knots. Tactical parameters were obtained by an airship taking photos all along. The goal was to study their seakeeping qualities, hull strength at max speed, in the open ocean. Each boat had an accelerometer installed in the pilot house. The first open water test started on 24 July 1941 over 190 nmi at full throttle, which became the reasons for the famous nickname “Plywood Derby”. It was conducted from the mouth of New London Harbor to Sarah Ledge and around the eastern end of Block Island, off Fire Island Lightship with the end line at Montauk Point Whistling Buoy.

Both Elco 77-footers were actually fully armament loaded, but the others instead had same weight copper ingots topside. The “race” shown a transverse failure for PT-70, the choice of copper being disastrous as they often fell into the hull. Of the nine that raced, six completed it, three withdrawing (PT-33 -structural damage; PT-70 -loosing copper ingots; MRB -engine issues from the start).

PT-20 and a single Elco 77-footer came first at 39.72 kn on average. PT-31 made 37.01 kn, PT-69 (Huckins boat) 33.83 kn and PT-6 (Higgins 81-footer) 31.4 kn, PT-8 Philadelphia NyD boat ended at 30.75 kn and the PT-30, PT 23, PT-31 being around 37 kts. Accelerometers ranked the Philly NyD PT-8, whch took the least pounding, and the Huckins PT-69, followed by the Higgins boat and Elco last.

The was soon a second open-ocean trial:

The ingot loading proved not very practical, but they were conducted this time over 185 nmi, still fully fitted out on 12 August 1941, and only PT-8, PT-70, and MRB ended the race. Elco sent PT-21 and PT-29, and like the others, fending off 16 ft (4.9 m) waves. The Huckins boat (PT-69) withdrew (bilge stringer failure), the Higgins 76-footer had numerous structural failures, PT-21 had minor cracks in the deck. PT-29 was used as a pace boat with PT-8. Average speeds recorded crowned Elco PT-21 at 27.5 kn, Higgins PT-70 at 27.2 kn, Higgins MRB and Philly NyD PT-8 at 24.8 kn, but accelerometers data were incomplete due to the heavy pounding. The air observation (aisrhsip) was abandoned due to the heavy weather. Elco boats were found the least structurally sound overall.

Board of Inspection and Survey’s findings were that any of these boats on average could reach 30 knots or even 40 knots with light ordnance load. Maneuverability was generally satisfactory with a 336 yards (307 m) turning circle, that there was enough space to accomodate the planned torpeod tubes and depht charges, but that structural weaknesses fractured bilge stringers quite often. It was agreed that the Packard power plant was to become a standard. It was also made standard an armament of two torpedo tubes, depth charges and light AA.

Overall, the Huckins 78-foot (PT-69) should be considered for immediate construction, the Higgins 80-foot (PT-6) design should be scaled down a bit and was ecceptable for immediate construction, while the Elco 77-foot design was acceptable under condition of strenghtening the hull according to the Bureau of Ships recommandations. The “in-house” Philadelphia 81-foot was to be lightened and given three Packard engines for new tests.

It appeared overall that the main issue was structural. Runs were made wothout issues on open sea with moderate seas, but the Higgins PT-70 and 77 footers. In between tests however, both companies worked to cure the causes of these structural failures. The second (punishing) endurance run still shown weaknesses on the PT-70, 69 and PT-21, but more localized and easier to modify on recommandations. Overall the “Plywood Derby” was a first naval, realistic, detailed and rigourous assessement, rarely done with any other warhip to far, in any country. It was a benchmark to be followed in the cold war and an essential part of the PT boat development in the US. Some design challenges needed decades to fix (in fact hull and propellers shapes determined by computerized calculations) but they defined a standard for propduction that could be easily implemented and arrived perfectly on time.

Not only the Packard plant received demands to step-up production radically, but the Huckins 72-foot and “redux” Higgins 81-footer were scheduled already for production. In October 1941 BuShips held a new conference, setting new requirements this time for production boats, notably the ability to carry the four 21 in (53 cm) torpedoes (no tubes), length restriction to 82 foot and confirmation of Higgins and Huckins orders.

Elco, which became the largest provider, was under scrutiny to cure its boats’s structural weaknesses, under BuShips recommendation. Even after these changes were done, Elco competed for the PT-71 – PT-102 order but failed based on a higher cost. They created a new facility to lower the unit cost, and received the third batch in the end.

Initial specifications

The USN looked for smaller vessels than their steel-hulled patrol boats, but higher speeds and cryying at first four 21-in (533mm) torpedoes. Primary role was ship hunting, and at first they were indeed classified as “motorized torpedo boats” (MTB), something widely shared and generalized in Navy parlance as MTB until replaced by missiles Fast Attack Craft or FACs. The USN evaluation resulted in some model chosen, but the companies behind lacked the industrial capability for mass production later degraded to simpler forms. This became the famous “Plywood Derby” ending with the choice of ELCO, Higgins and Huckins. All three soon received orders.

Conclusion of trials

It’s Elco Motor Yachts from Bayonne, New Jersey, but also Higgins in New Orleans in Louisiana (already seen for the LCVPs) which were retained for mass production, along with Huckins since the two soon had bottlenecks for production. Ultimately it’s Elco that produced the most numerous of them. The design and construction were thus standardized between the 80-foot Elco boat, the 78 ft Higgins, and a the 78 ft Huckins Boat. Near 400 Elco PTs were built, while Higgins turned between 199 and 205 and just 18 for Huckins.

Elco answered after simply purchasing a British the new Scott-Paine MTB, sent to Electric Boat in Groton, which Elco was a subsidiary. No need to present Electric Boat, they were the great pioneers of US submersibles. This Elco prototype was called PT-9 becoming the very first US PT boat, after many modifications. But still needed time To prove the concept on sea trials, alone and against other PTs. For two years, PT-9 won all the plywood derbies. Confident it its wooden wonder, Elco enlarged its plant, tripled its capacity and it the peak in 1944, employed some 3,000 men and women working three shifts per day, six days a week, with one new PT boat solling our of the line every 60 hours.

General conception & construction

These PT-Boats were built en masse by four main firms: Elco, Higgins, Vosper and Huckins. Although the first two remain in the majority, the Vosper were of British origin, built and transferred in “resverse lend-lease” as it is true that the British expertise in the matter was recognized worldwide. 768 units will be built in total. The traditional doctrine of the US Navy, inherited from Mahan and ignoring the “naval dust”, however used launches in large numbers during prohibition, patrolling against the traffic of Rum on the great lakes from Canada. . Thornycroft launches had been purchased on a trial basis at the end of the Great War, and in 1939, when hostilities broke out, several prototypes were ordered, including one built in Britain, from Hall-Scott, which became retrospectively the 9th of these prototypes (PT9) and the direct ancestor of the PT-Boats.

These PT-Boats were built en masse by four main firms: Elco, Higgins, Vosper and Huckins. Although the first two remain in the majority, the Vosper were of British origin, built and transferred in “resverse lend-lease” as it is true that the British expertise in the matter was recognized worldwide. 768 units will be built in total. The traditional doctrine of the US Navy, inherited from Mahan and ignoring the “naval dust”, however used launches in large numbers during prohibition, patrolling against the traffic of Rum on the great lakes from Canada. . Thornycroft launches had been purchased on a trial basis at the end of the Great War, and in 1939, when hostilities broke out, several prototypes were ordered, including one built in Britain, from Hall-Scott, which became retrospectively the 9th of these prototypes (PT9) and the direct ancestor of the PT-Boats.

Quickly the PT10 to 19, of the “70 foot” model and armed with two torpedoes, were delivered by Elco (Electric Boat Company, founded by the father of modern American submarines, John Holland), then lengthened to 77 feet to place four torpedoes. 12 ASM models (PTC1-12), built in parallel, were sent to the Royal Navy on lease. The firm Elco then produced the series PT20 to 68, of 80 feet, which would become its standard. The PT109 was part of the third series, PT103 to 196, and there were 6 others, the PT314 to 367 and 372-383, and up to 790, or 400 copies in total until 1945. They were built in wood, in order to combine lightness with ease of construction and to contribute to the preservation of strategic materials.

Hull

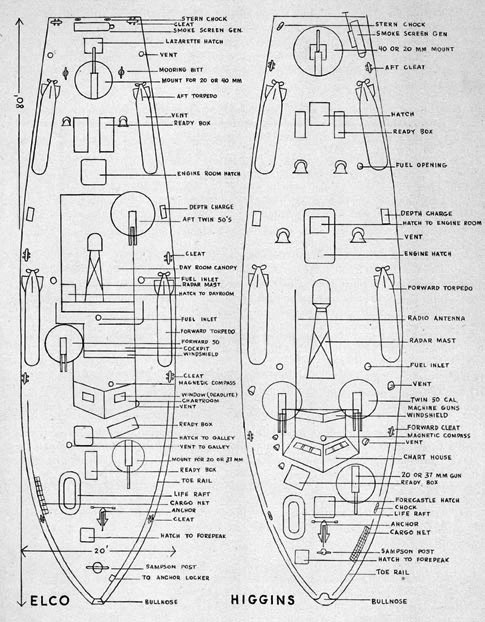

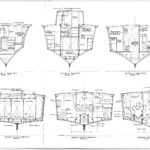

ONI, know your boat, upper deck showing differences between Elco and Higgins boats, July 1945

Nicknamed by the press “plywood wonders”, the PT Boats were in reality constructed of two diagonal layered 1 in (25 mm) thick mahogany planks, with a glue-impregnated layer of canvas in between. Holding all this together were thousands of bronze screws and copper rivets to avoid rust. This had the advantage of easy damage repair in the field, patching, ect. And to include local base force personnel. They proved also capable to be disassembled relatively easy, as five Elco Boats arrived as knock-down kit to Long Beach Boatworks for assembly (West Coast) just to see if that was possible. And the five were assembled and operational in a short notice indeed, without much issue. This offered further strategic mobility, as now they could even by, at least in theory transported by smaller vessels and/or in larger quantities rather than all-mounted on top of decks.

The construction of the Elco boats reused some recipes from Huckins boats, and their structure was made of mahogany, in 2×2 thick planking, while Higgins boats had recipe of its own, but used about the same techniques.

Aluminum parts were expected to be painted and cleaned in suitable pickling solution, or washed with clear water, dried and painted afterwards with zinc chromate primer before its regular painting.

All stainless corrosion-resisting steel prior to painting were to sand blasted or cleaned before painting.

Galvanizing using the hot process was to be done with zinc at least 98% pure, ater treatment of zinc spray and not hot dipping. It was even stated that the increase in weight due to galvanizing could be between 0.8 and 1.6 pound per square foot. For all external parts to be galvanized it was expected to use a heavy coat of red lead.

See also: DETAIL SPECIFICATIONS FOR BUILDING MOTOR TORPEDO BOATS PT 565-624 (80-Foot) – By BuShips 31 March 1944.

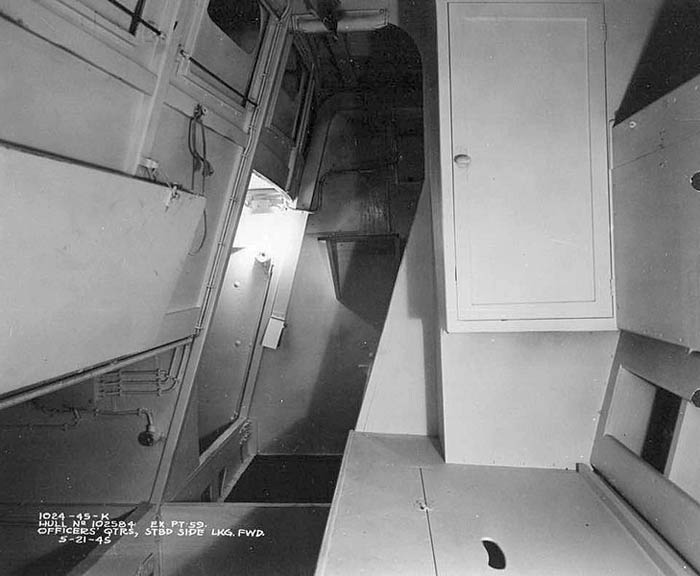

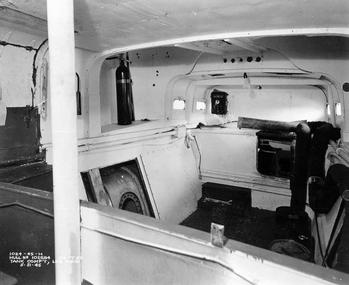

The Officer’s quarter on board Elco PT109

The internals were spartan to say the least, but functional. The interior, while full speed, was so noisy no sailor could ever dream to try to sleep inside. They all waited until the boast was stantionary at a safe place. Thus it was not rare to see them, unlike larger ships using quarters, operating on 24-hours shifts. Accordinf to the lit of equipments, the boats were granted enough mattresses and sleeping berth for all men onboard. As shown on this cutaway or this one by Donn Thorson, living quarters, understandably, were located forward, as far as the engines possible. However in rough weather this was a very noisy and leaky compartment to live in.

Safety: Elco boats carried a Rubber life raft and a 9-foot Dinghy. Each of the 14-17 sailors and officers had both regulatory WWII US Navy Kapok Life Jacket (or assimilated), and when in action station, a standard M1 helmet, Navy version. It was not the US Navy Mk II talker helmet. The dimensions of the boats were such that oral communication and signs still worked.

The bridge on board Elco PT109

Powerplant

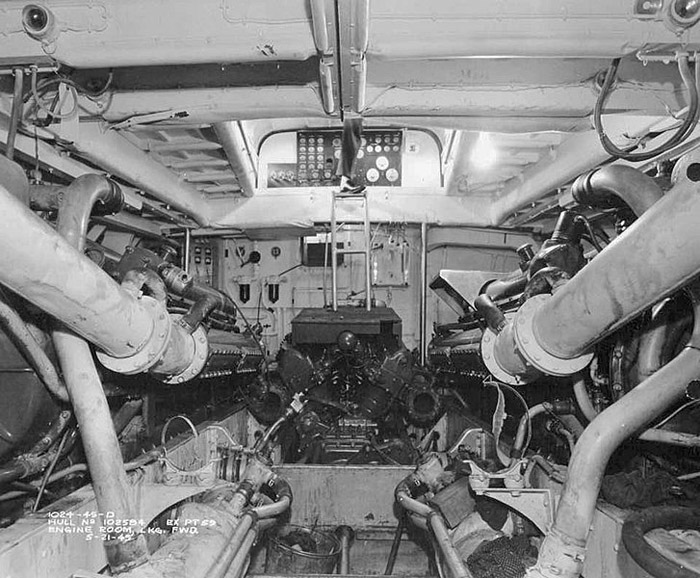

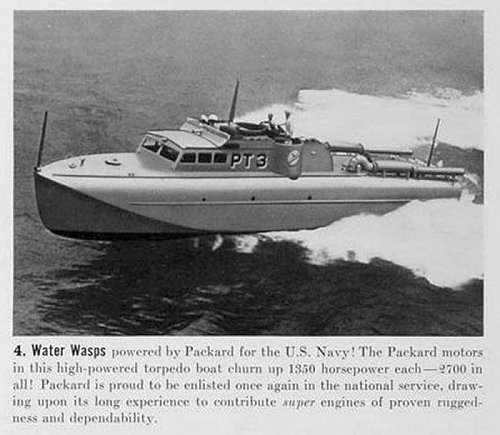

The mainstay of all designs was the Packard V12 4M-2500 (and following), a marine petrol engine which had nothing to do with the British Rolls Royce Merlin engine as sometimes stated, but a model developed for boat racing in the 1930s, notably deceloped by Garr Wood for his world record speed boats. Here what is said about it by him (src)

Packard 4M-2500 (pinterest)

Packard built already thousands before the second world war notably “Liberty” aircraft engines and sued General Electric superchargers patents to create the serial marine engine for U.S. Elco, Huckins and Higgins PT Boats as well as British Vosper MTB’s. Given all boats carried three of them, that’s at least 1,500 provided for completion, but since they were worn out after years of service, the same number of replacement engines and parts would grow to above 3,000 for PT Boats alone.

The initial Packard 4M 2500 provided 1200 bhp, then 1,350 BHP and by 1945, 1,500 BHP, meaning a total output “under the foot” of 4,500 bhp, but they were also known gas-guzzlers 5000 gallons of 100 octane aviation fuel consumed ina single night sortie. Cruising speed was 2400 rpm with a theoretical 3000 rpm for 41+ knots bursts.

Some in the field changed the gear ratio’s on the supercharger for extra power also, but this practice shortened their life span. Packaerd designed specially for the PT-Boat a terminal electrical device to synchronise them. The centre engine was surrounded by a port and starboard wing engines, not direct but but through Veedrive gearbox. Cavitation issues at low speed and a tendency to veer left was known (see also the handling).

The engine room on board Elco PT109

Handling

PT boats were designed -as stated in the handling book- to answer the following question:

“Is it possible to build a small ship, extremely fast and still seaworthy, which can deliver a real knockout punch to a capital ship?”

So having the seaworthiness of a round-bottom sailing ship and huge speed was only relevant as so far the sea stays calm, or be at east in the worst weather didcated compromised. The PT boat was designed thus to outrun anything that floats and carrying also weapons to sink all kind of targets, while being capable of a reasonably high speed in bad weather.

Its flat-bottom required special handling in a seaway and don’t needed to be capped in speed on a 4-foot sea still. But at double, thanks to maximum speed down wind or across. It was discourage to try to head directly into the wind and heavy weather, while it woukld be impossible to man stations properly, with the addition of much spray reducing further visibility.

It was advised to steer a zigzag course, and taking the wind and seas quartering over the bows instead to optimize speed, maintain visibility. Condition of loading of 30°-45° and down to 20° were sufficient. In a 20 feet sea and greater, it was estimated a PT Boat still steer down wind or across it and steer into it with a turn or two of the wheel, obove crests and calculating the next wave at a favorable angle. Steering left and right would allow to keep a almost straight course, dead aweather at good speed.

The PT boat having three right-hand propellers, and two or three rudders, each directly aft of each propeller in the slip-stream had effects on the handling, obviously. This made for a triple torque, tendency to veer to the left full speed ahead and rudder amidships. It was due to the top propeller blade working at pressure than the bottom blade, giving the latter a stronger thrust against the water sideways pushing the stern starboard at 1,000 r.p.m., on all three shafts. 3° to 4° right rudder were needed to compensate. It was cancelled above 1,500 rpm and at high speed.

Another characteristic was its great agility: A PT boat would turn on her own length at slow speed, one engine ahead, one astern, rudder hard over. This was handy in the confined in some areas, or just to manoeuver with other vessels nearby. PT Boats were often “packed” in squadrons near their motherships, when not berthed.

To have a better idea of the Huckins 78ft internals: ptboatforum.com

Equipments

Here is an extract of the BuShips march 1944 handbook for 80 footer PT Boats construction:

Two Pioneer compasses, One Rubber life raft, One 9-foot rigid standard dinghy (stored aft of the mast).

For the crew, accomodation anf furnitures:

CREW’S QUARTERS: Four Transom berth cushions, pantasote covered, One Mess seat cushion, same and two Mess seat cushion backs, same, One Door curtain, lavatory, One Table, mess.

OFFICERS’ STATEROOM: One “Root”-type berth, One Transom and cushion, Two Thin mattresses, One Chair, with cushion.

PETTY OFFICERS’ STATEROOM One “Root”-type berth, One Transom and cushion, Two Thin mattresses.

CHART ROOM: One Seat cushion, pantasote covered, One Back cushion, pantasote covered.

OFFICER’S MESS: One Seat cushion, pantasote covered, One Seat cushion, back.

CREW’S DAY ROOM: Two Crews lockers (portable), Two “Root”-type settees, Two Mattresses.

ENGINE ROOM: One Observer’s seat cushion.

MISC:

-One M. S. A. explosimeter Model 2.

-A Regular steel shipping cradle per boat, complete with chocks and boat-locating arms. In addition, there shall be supplied one out of every four cradles equipped with rubber-tired wheels and steering linkage.

-Two 75-pound Danforth anchors, with 5/8″ shackle and 3/4″ pin.

-Two 50 Fathoms 4 1/2″ sisal anchor rope complete with thimble and shackle. Rig one for service.

This is just a part of all equipments aboard.

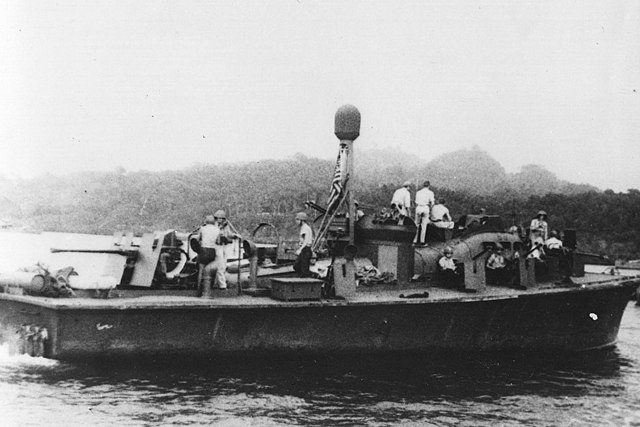

The SO Radars

In standard from 1943, all PT Boats received a SO type radar, placed on top of their twin leg mast, aft of the bridge. The small array was protected from sea spray by a plastic dome.

This was a family of small, short range Air/Surface Search radars mostly intended for night operations. The “family” comprised the SO-1, SO-2, SO-7, SO-8, SO-9, SO-11 and SO-13, all 10 cm sets with slightly different powers and ranges. SO-3, SO-4 and SO-12 (CXBX) operated at 3 cm only.

Production was 525 SO (all types) and 587 SO-13 (which became standard between February and November 1944), but also 2047 SO-1, 1700 SO-8, 535 SO-2, 110 SO-9, 350 SO-4 and 235 SO-3, all with the basic same wavelength of 10 cm and power Output of 75-200 KW. Crucially the detection range was 16 nm on average at the surface and 35 nm in the air. Pulse Width was 0.37 or 1 microsecond with a Frequency of 650 Hz (on 65 kW), scan rate 12 rpm, and at max range unclutterred it could detect all surface targets up to 20 nautical miles (37 km), down to 5 nautical miles (9 km) for submarines.

The 420 lbs or 190 kg units were found on PT-Boats but also on many light vessels and “boats” of the USN, such as sub-chasers or LCCs.

Armament

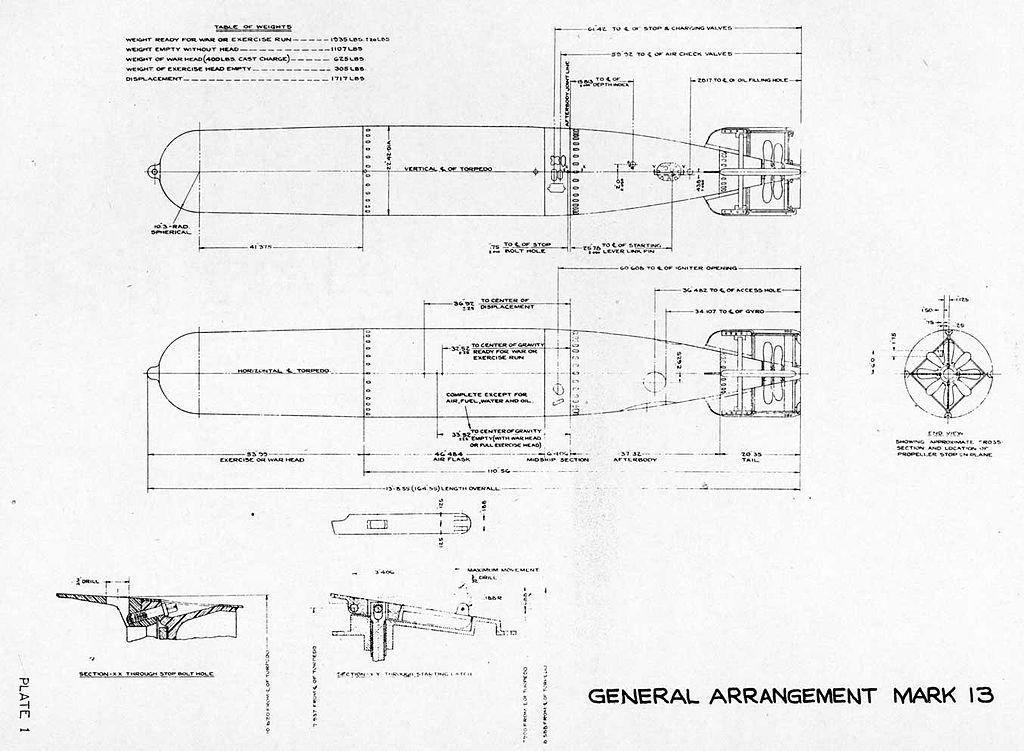

Their initial armament included 4 torpedo tubes, later phased out, as lighter 21-in Mk.13 torpedoes (shortened Mk.14) with gyroscope launching, from the side cradles were the main armament. It was coupled in all cases by four heavy machine guns 50 cal. (12.7 mm) Browning in twi turrets after of the bridge. Things became quirky for the heavyer AA armament, with mix 40 mm Bofors, 37 mm and 20mm Oerlikon AA guns.

For infantry support, some were given two rocket launchers, 12 tubes, 114 mm (4 in), and 127 mm (5 in) in 1944, going as far as four sets an a 60 mm mortar (2.3 in). With a wooden deck it was easy to bolt on many equipments in various locations. Still, there were guidelines on stability to be followed. They also had ASW launchers at the stern with the provision of ten ASW grenades and sometimes two depht charge launchers without reloads, or coupled with two reload racks using pushers.

Typically the Huckins was armed with a 40mm Bofors aft (like the others), a 37mm standard, also centerline on the bow deck and a 20mm Oerlikon also aft, centerline with a simple locker separating it from the stern Bofors. The bridge was indeed further forward than the others and the two twin cal.50 were at the same level abaft the bridge, unlike the Elco boats which had these two in échelon, as were its largest guns, the Bofors and 37mm, also in échelon aft. The Oerlikon was placed forward.

One feature that became commonplace were two sets of 8-cell Mark 50 Rocket Launchers installed on a swivel mount that can allowed the launched to be folded inwards, and outwards when in use.

For an Elco boat of 1944, the BuShips preconised list included:

-Four Torpedo launching racks, Mark 1.

-Two Mk. 17, Mod. 1 mounts for twin .50 cal. machine guns.

-One Mk. 14 22 mm. A. A. mount.

-One 40 mm. Army type A. A. gun (stern) with tools and equipment.

-One .50 cal. machine gun spare (packed in box).

-Two .50 cal. machine gun Instruction Manuals.

-Two sets .50 cal. machine gun sights.

-One box spare parts for .50 cal. machine gun mounts and cradles.

-Eight ammunition boxes .50 cal., 250 rounds each.

-Eight ammunition boxes .50 cal., 250 rounds each, spares.

-One Oerlikon 20 mm. A. A. machine gun, 1 box of spare parts and tools, and 1 instruction manual, and 12 magazines.

-One Oerlikon spare barrel.

-One Smoke screen generator Mk. 6 for mounting on stern.

Torpedoes

A Sailor readies a torpedo for launch from PT boat off Florida c1944

The standard model imposed was the Mark 13 Bliss-Leavitt. This was an aerial torpedo, but of 21-inch rather than 18-inch. It was not a reduced copy of the standard (and very controversial) Mark 14 per se and shared many components, fortunately not all its defects.

It originated in a 1925 design study but development dragged on along Navy specs changes. By late 1944, the design was refined enough to allowe reliable drops from 2,400 ft (730 m) at 410 knots (760 km/h) instead as exposing the carriers, very low and very slow. This of course was no problem for the PT-Boats. The 1944 Mark 13 weighted 2,216 lb (1,005 kg) and still carried a potent 600 lb (270 kg) of HE Torpex.

Although classed as a “21-in” it was in reality as 22.5 inches (570 mm) tprpedo measuring 13 feet 5 inches (4.09 m), squat dimensions compatible with the bomb bay notably of the Grumman Avenger. It was not supermely fast, only reaching 33.5 knots (62.0 km/h; 38.6 mph) over 6,300 yards (5,800 m) which was 12.8 knots slower than the Mark 14, and it had a lesser negative buoyancy. Nevertheless it lacked magnetic influence system used in the same Mark IV exploder and thus, had at first a better detonating chance. Total production reached 17,000 in WWII.

Mk.13 Torpedo launched from its cradle, at full speed.

It should be noted that early models, such as the PT-109, used a Mark 14 torpedo (Elco PT boats) and some were even given the older Mk8 torpedo depoending on available stocks. This was prior to the fitting of the much lighter Roll Off Racks for the 22.5″ Mk13 which became standard issue in 1943. The use of the Mark 14 explains the lack of successes in 1942.

Anti-aircraft

In 1944, a prototype with greater firepower was built, the “Thunderbolt” equipped with a 20 mm Oerlikon quad AA mount M??? at the back, similar to that which equipped Half-Tracks. Nothing came out of it, since these mounts were already in short supply for the European theater.

But the usual lot was of four types:

-One 40 mm Bofors Mark VII see more

-One 37mm autocannon Mark 4, a 1924 patented Browning design, in service from 1942 (ROF 150 rpm mv 2,000 ft/s, using 30-round magazine)

-One 20mm Oerlikon Mark VII? See more

-Four 50 Cal (12.7mm -1/2″) Browning Machine Guns mounted in manually operated rotating turrets, with the ammo bands circling inside.

Depth Charges

Appearance

One of the mediterranean camouflaged tested the spectacular “zebra pattern” in black and white or shades of grey, which was very distruptive but complex to make and thus, rarely applied. The only larger ship that displayed this supreme “razzle dazzle” scheme was the French cruiser Gloire.

BuShips recommended that all completed boats were painted and varnished throughout, with sufficient coats to preserve the surface on the long run. All fastening holes and sensitive outside equipments shall be carefully puttied when they were not plugged (bolted) with sanding before and between coats. Of course for all external metal the fampous standard “red primer” was indispensable. The standard marine paint by default was the Navy formula 5-11 special haze gray (Navy Dept. Spec. 52C45). Fastening holes used smoothing cement, Navy formula 62. The finish was a coat of haze gray (Navy formula 5-H) and a third finish coat was left to the latest camouflage schemes, to be applied in the field.

The Bottom was primed with copper bottom enamel, with all fastening holes cemented with putty, finished with two coats of the same as before. The interior was only painted with one coat of primer, glazed and with two coats of fire retardant white paint (Navy Dept. Spec. 52P22). An extra coat was required in busy passageways or confined spaces, which were many. The superstructure was finished with no less than three coats of formula 511 special haze gray, and final camouflage. Decks were primed with fastening holes filled with smoothing cement and two coats nonskid deck paint, plus camouflage if required. Thus, not only the hull, but superstructures and decks could be painted.

Huckins 78-foot (24 m) PT-259 underway near Midway c.1944

As for this external field painting, many of these units were camouflaged to match the densely vegetated environment. Still on the “decorative” chapter, their crews liked to paint “shark mouths” on the stern, others were more inspired by pin-ups and cartoon characters taken from the habits of bomber crews. But these aesthetic escapades were often in contradiction with the official directives whose respect was ensured by more or less tolerant unit commanders…

There were however official camoufmage schemes provided, followed with more or less zeal. For examples, see the individual profiles at the end of the article.

Trials by Fire: Tactics & Operations

USS PT-167 is holed by an enemy torpedo that failed to detonate, 5 November 1943. Painting by Gerard Richardson

“PT boats filled an important need in World War II in shallow waters, complementing the achievements of greater ships in greater seas. This need for small, fast, versatile, strongly armed vessels does not wane.”

— JOHN F. KENNEDY

PT (Patrol, Torpedo) boats were deemed quite useful for short range oceanic scouting with with torpedoes and light, fast armament. It was at forst thought of them to attack enemy supply lines and harassment of warships. All, in all some Forty-three PT squadrons were created in time, each sporting no less 12 of them. PT boat duty was not thought after but by those who want something very dangerous, requiring string caracters and initiative. Despite some results, these squadrons suffered an extremely high loss rate in WWII, being overall more easy prey for larger ships than hunters themselves. Their most useful role in the Pacific notably was to assist submarines in destroying Japanese supply lines. However with only a limited radius of 500 nm at 20 kts, bases needed to be kept “close to action” which was only permissible in some areas, like the Solomons, Marshall and Philippines or around New Guinea. The first Higgins boats fought at the Battle for the Aleutian Islands in 1943. Later they were preferrablly shipped to the Mediterranean theater, Elco models being used almost exclusively in the Pacific.

Originally antiship vessels, they were publicly and erroneously by the press credited with sinking Japanese warships soon after Pearl Harbor but their earl test was in the long Solomons campaign an most often by night. They mostly targeted Japanese barge traffic in the highly contested “Slot.” But squadrons were deployed in the southern, western, and northern Pacific. A few even saw action in the English Channel, seeing action in Normandy.

During World War II Elco Naval Division of Electric Boat Co., Bayonne, N.J., built nearly 400 PT-boats for the U.S. Navy. Most (326) were of the standard “80-footer” using the trademark double-planked mahogany construction, gaining fame in daring night raids on movies but rarely succeeded in those attacks. They carried indeed four torpedoes, but they were of low power, similar in capabilities to airbone models, with a direct contact, surface run at relatively low speed, short range compared to standard Naval Torpedoes.

Their primary mission was to attack enemy shipping, everything that presented itself. Ideally warships, and by default, landing vessels, auxiliaries and merchant ships. For antiship missions, they could lay and destroy mines when equipped with paravanes or special gear. They were used also for ASW patrols, being given a few depht charges, and an hydrophone, by default of a sonar. They were also used to sneak out at night behind enemy lines and carry out rescues or harass enemy coastal supply lines earning the nickname “barge busters.” PT boats were also sufficienty well armed to provide fire support for troop landings, being able to beach themselves before extraction. They would be used also to lay smoke screens and rescue downed aviators, or to carry out intelligence, and doing deep raids which gave them the same aura in the public as their land african equivalent, the “Long Range Desert Range”. Almost all surviving Elco PTs were soon scrapped or sold.

For these “specops” operations the boats’s initially open air exhausts at the back were covered by mufflers. They were used for silent running by feeding the exhaust out under the water at low speeds. Each had butterfly flap valves fitted in the main exhaust pipes, after the muffler take off, operated by a lever system. Thus system was proven relatively effective and made the chances of a PT Boat arriving on target at low speed by night in surprise way greater.

A 80-foot (24 m) Elco PT boat with original Mark 18 torpedo tubes on patrol off the coast of New Guinea, 1943

General Mac Arthur praised the PPT Boat concept he saw very well fitted for the defence of the Philippines, he became a strong advocate of PT boats, but none was present when the Japanese attacked in January 1942.

“A relatively small fleet of such vessels, manned by crews thoroughly familiar with every foot of the coast line and surrounding waters, and carrying, in the torpedo, a definite threat against large ships, will have distinct effect in compelling any hostile force to approach cautiously and by small detachments.”

— General Douglas MacArthur

Seen from Washington, DC however, the few PT-Boats done were all to be sent to Britain in lend-lease. MacArthur instead tried to appraoch Britain to procure a serie but all models were kept for British service in wartime. He could not test PT boats to defend the Philippine Islands when they were really needed, but a few arrived before the fall of the Philippines, evacuating personnel including MacArthur himself and his family. PT-41 (Lt. John D. Bulkeley) MTB Ron 3 evacuated them from Corregidor, after he famously said “i shall return”. The mission was done by night through the Mindoro Strait via Cuyo Islands (west of Panay) and a close encounter with a Japanese cruiser west of Negros.

PT-41 arrived in Cagayan (Mindanao), MacArthur promising recommendations for the crews. Bulkeley earned a Medal of Honor for his dangerous run. It’s after this start that PT-Boats, sometimes called “MacArthur’s secret weapons” often were reported in the medias with bogus sinking of important Japanese ships. Most of the time they proved false, but in some case, damaging was assimilated to sinking. In any case, these were a moral booster after the loss of the Pearl Harbor battlefleet and series of defeats. But they were forgotten when media attention was diverted to the Doolittle raid.

During the Solomon Islands Campaign the press was quick to raise to the public’s attention back at home the “Green Dragons” and “Devil Boats”, as nicknamed by the Japanese. They were deployed to hunt warships in the early doctrine, but results were so mediocre (due notably of faulty torpedoes) that they were soon withdrawn from these operations. Modern “speical type” IJN destroyers were more hunters than preys for these and they paid aheavy price, with the greatest loss rate in 1942 and until early 1943. Modern destroyers indeed used projectors and could fire fast and fiercely enough to destroy these “mosquitoes”. PT Boats plays more of a deterrence which indirectly caused extra caution when Japanese knew PT boat presence, disrupting indeed their supply runs, notably to Guadalcanal. The Japanese recovered several Mk.13 torpedoes and soon came to the conclusion these PT boats were a mild threat overall, but this modified their plans and this caused ultimately their defeat and evacuation of the island and in fine, the fall of the Solomons.

Commander Bulkeley, which evacuated McArthur declared that these PT boats were made:

“to roar in, let fly a Sunday punch, and then get the hell out, zigging to dodge the shells.”

This was partly true but over romanticized during WW2 by the medias, fuelling a popular belief that they could engage enemy capital ships and still escape. But in reality they were just too noisy and still too slow not to be dealt with, with deadly accuracy by any IJB secondary and even AA guns. Attacks of this kind were quite rare, not to say suicidal. The wooden hulls could not even hold water with a near-miss, let along direct hits.

PT 59 after her conversion into a gunboat.

The tactics were rapidly changed, and smaller forces (not full squadrons) were detached during the night for such attacks, engines running low, with all kinds of measures to try to mitigate their noise. They approached that way until torpedo range (which was short), launched and indeed escaped at full speed. By night the torpedo wakes were indeed sometimes detected. If the torpedoes hit and exploded, flames would illuminate the whole area and uncover their position as a giant flare would. When trying an “all stealthy” approach, the commander also tried to escape at low speed until the torpedoes hit, or if the first round missed and still undetected, officers which could stomach it would try a second attempt. Nerve-racking to say the least.

The real specialty came about naturally, in this quick darwining evolution. PT boats found more success against Japanese barge cnvoys, often weakly defended, rather than warships. As soon as this was discovered and now “cold” about the use of their faulty torpedoes, all squadrons commander wanted thier boats to be reconverted as gunboats essentially, with more machine guns and light cannons added. Some wanted the standard 3-in/50, but the weight was just too great for the wooden hulls and rate of fire still unsufficient for this kind of raids. Instead, the most efficient weapon, outsid the 20mm Oerlikons, were the often always stern Bofors. Its position imposed tactics in formation, whith loops, starting with a forward charge, broadside and retreat all guns blazing.

US air superiority in daylight condemned the tradtional Japanese convoys with large ships to night missions with barges instead, “coating” in shallow waters.

“Know Your Boat” distributed to newly trained crews, as often using humor to let the message pass better. U. S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1945, Maritime Park Association

PT boat crews fed a reputation of recklesness fed by their own profile, with small crews authorizing far greater familiarity between officers and men, and lax discipline. Initiative was not only on the line of duty but also in the art of scavengening whatever could bolster their capabilities or supply them in the scarcity of the early war conditions. This lax attitude was reflected also on land during rest periods, with the military police kept more busy with this lot. PT Boat crews were also known for lax outfit to say the least, fighting bare chested and not always wearing trousers, or having non-regulatory attire. A situation not unlike some submarine crews. One thing the navy obtained at least was to avoid painting personal symbols or pinups on their boats, unlike the air corps. They were often locally camouflaged, in sometimes surprising fashion, although the Navy obtained some discipline there in patterns and colors, which was regulated (see apparearance). They tolerated though, the occasional shark teeth on the bow.

Nevertheless, while all this took place, the naval staff official doctrine was still to seach and attack surface vessels, and recoignising the danger of exposure, they were supposed also to lay mines and use smoke screens. More missions added to the lot, which impacted their loss rate. All in all it seems, depending of the source, that 531 PT boats were built. The overall picture was 69 lost mostly to enemy fire, followed by storms and accidents or friendly fire. Early boats of 1941 were simply worn out by 1943-44. The loss ratio was still very acceptable as these were considered “expendable”. But the Navy wanted to have nothing to do with these boats, which were mostly gathered at PT Base 17, Samar, Philippine, to be broken up to salvage everything of value and leave the wood to rot. Nine PT boat hulls survived, some restored (see below).

58 footers Prototypes

PT-9 off Washington DC (1940)

PT-1:

This very first 58ft Experimental MTB, laid down 12 July 1939 by Fogal Boat Yard in Miami, Florida to answer the USN called. She was launched launched on 16 August 1939 and completed 20 November 1941, tested by the navay but rejected, and nicknamed “Wet Dream”. She was reclassified as a Small Boat pennant C-6083 on 24 December 1941, ending as a service launch at Newport. 30 t, 30 knots, armed (as planned) with two Mk IV-4 torpedoes, two .50 cal. M2HB. She was powered by two 1,2000 hp Vimalert gasoline engines after after initial trials, on Navy demand, by Packard 4M-2500 engines on two shafts.

PT-2:

A second 58 feet Experimental Motor Torpedo Boat (laid down 19 August 1939 at Fogal Boat Yard in Miami, Launched 30 September 1939, Completed 20 November 1941

(later reclass. as “Small Boat, C-6084” in December 1941, kept for training. She displaced 30 t, with two shafts 1,200hp Vimalert gasoline engines for 30 kts.

PT-3/4:

Ads by Packard, on the PT-3

A third 58 footer prototype, laid down 1 August 1939 at Fisher Boat Works in Detroit, completed on 20 June 1940 and placed to the MTB Sq1 for trials on 24 July 1940. MTBRon 1 was commanded by Lt. Earl S. Caldwell. After a serie of trials she was transferred on 19 April 1942 to the Royal Navy as MTB-273 but canceled and went instead to the Royal Canadian Air Force as Bras D’Or, M 413 (first of the name, the other would be a cold war hydropter) used as a High Speed Rescue Launch for downed pilots.

She was returned to the U.S. in April 1945, retransferred to the Shipping Administration in May 1946 and undergoing today a restoration.

First with two 1,350hp Packard gasoline engines for 25t (beam 18 ft) she combined two standard torpedoes, two .50 cal., two DCR. Speed unknown.

PT-4 was Laid down at the same time as PT-4 at Fisher Boat Works and completed by 20 June 1940, trialled at MTBRon 1 she was nicknamed “Get In Step” and later “Old Faithful”, scheduled to be the RN MTB-274 but RCAN instead (B-120), back to the US in June 1945, civilian service from October 1946. Same specs as above but armed with only two twin HMGs.

80 footers Prototypes

PT-5:

First Higgins 81 footer prototype. She was laid down on 1 August 1939, launched 4 November 1940, comp. 1 March 1941 and received by the US on 17 March 1941 to MTBRon 1, making gruelling trips at high speeds. After this, like MTB-3/4 her transfer to the RN was cancelled and she ended in the RCAN as Abadik (M 407), with Eastern Air Command, Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, later B-117, back to the US in 1945, then Shipping Administration in 1946 and from 1948 used by Nock Sicari of Flushing in New York as the yacht Gloria. She displaced 34 t for 15.4′ beam and 8.5′ draft, but these are the 1948 measurements. The crew was 6, and she operated during tests with two 21-in torpedoes, two .50 cal. HMGs, powered by three 1,200 bhp Vimalert gasoline engines, the first with this configuration.

PT-6:

There were two of them initialy, both by Higgins as 81 footers. The first was contracted to Finland as rescue boats, but sold to the RN in June 1940, MGB-68 in January 1941, training duties at HMS St. Christopher (Coastal Forces training base), Fort William, Scotland. Paid off in July 43, sold 1944 civilian service, then to father Euan O’Brien’s (1968) in Scotland, houseboat in Bowling Basin until 1977, then to Bowling 1980s and in Clyde, destroyed by fire in 1988. 34 tons, three Packard 3M-2500.

The second one was identical (Launched 29 October 1940) and assigned for tests at MTBRon 1, RN transfer cancelled in July 1941, instead RCAF Nictak (M 447), returned June 1945, Small Boat, Fate unknown. She had better Packard 4M-2500 gasoline engines.

PT-7:

PT-7 was another 81 footer, a “BuShip boat” built at the Philadelphia Navy Yard, launched 31 October 1940, with her transfer cancelled after some tests to the RN, and instead became RCAF Banoskik (M 408) in Nova Scotia, later B-118, returned to the US in 1945 and sunk as a target soon after.

She was quite larger and heavier at 51 t for dimensions 81 x 17 x 3 feet, 41 kts. Armed with four 21″ torpedoes, one Bofors mount and four Hall-Scott gasoline engines mated on two shafts.

PT-8:

Second admiralty boat, with an Aluminum-hull built by Philadelphia Nyd. Launched, 29 October 1940, started tests with MTBron 1 from 25 February 1941 then MTBron 2, 13 August 1941 and later reclassified as the District Patrol Craft YP-110, 14 October 1941

Assigned to Inshore Patrol, Fourth Naval District, 1942, stricken 10 January 1943, but not scrapped, hull retained for tests, sold postwar, seen on sale 2008, extant in Franklin, LA, 2010.

PT-9:

The sole British MTB in US service, for trials. She was a 70 footer Scott Paine MTB, laid down by the British Power Boat Co., Ltd., in Hythe, Hampshire and acquired by the Navy on 24 July 1940 for comparative tests at MTBRon 1, then transferred on 8 November 1940 to MTBRon 2. Tested in Florida and Caribbean waters, winter 1940-1941, to be retransferred to the RN but instead went to Canada as

V-264, Halifax-Gaspe harbor defense force, then S-09 and from March 1943 patrolling from Quebec (blackout patrols) on the Saint Lawrence River, mostly searching for U-Boats. Safety vessel in Toronto, 1944, returned February 1945, sold for BU September 1946, tr. Shipping Administration 1946, fate unknown.

Specs: 55 t. 70 x 20 x 5 ft, three 1,500shp Packard V12 M2500 gasoline engines for 41 kts. In Canadian service she had two MGs, 8 Depth charges, powered by two 550hp Kermath V-12 gasoline engines.

WW2 small series & prototypes

Elco PT-10 to PT-19:

70 footers launched from August 1940 at Elco, Bayonne, New Jersey. They all served with MTBRon 2. (Displacement 40 t. 70 x 11 x 6 ft, Three 1,500shp Packard V12 M2500 for 41 kts, crew 14, armed with two twin .50 cal. M2 (Dewandre turrets), four 18″ torpedoes or two 21″ torpedoes) plus alternative Lewis MGs and 20 mm Oerlikon, all. Most were transferred to the RN Transferred to the Royal Navy from 11 April 1941.

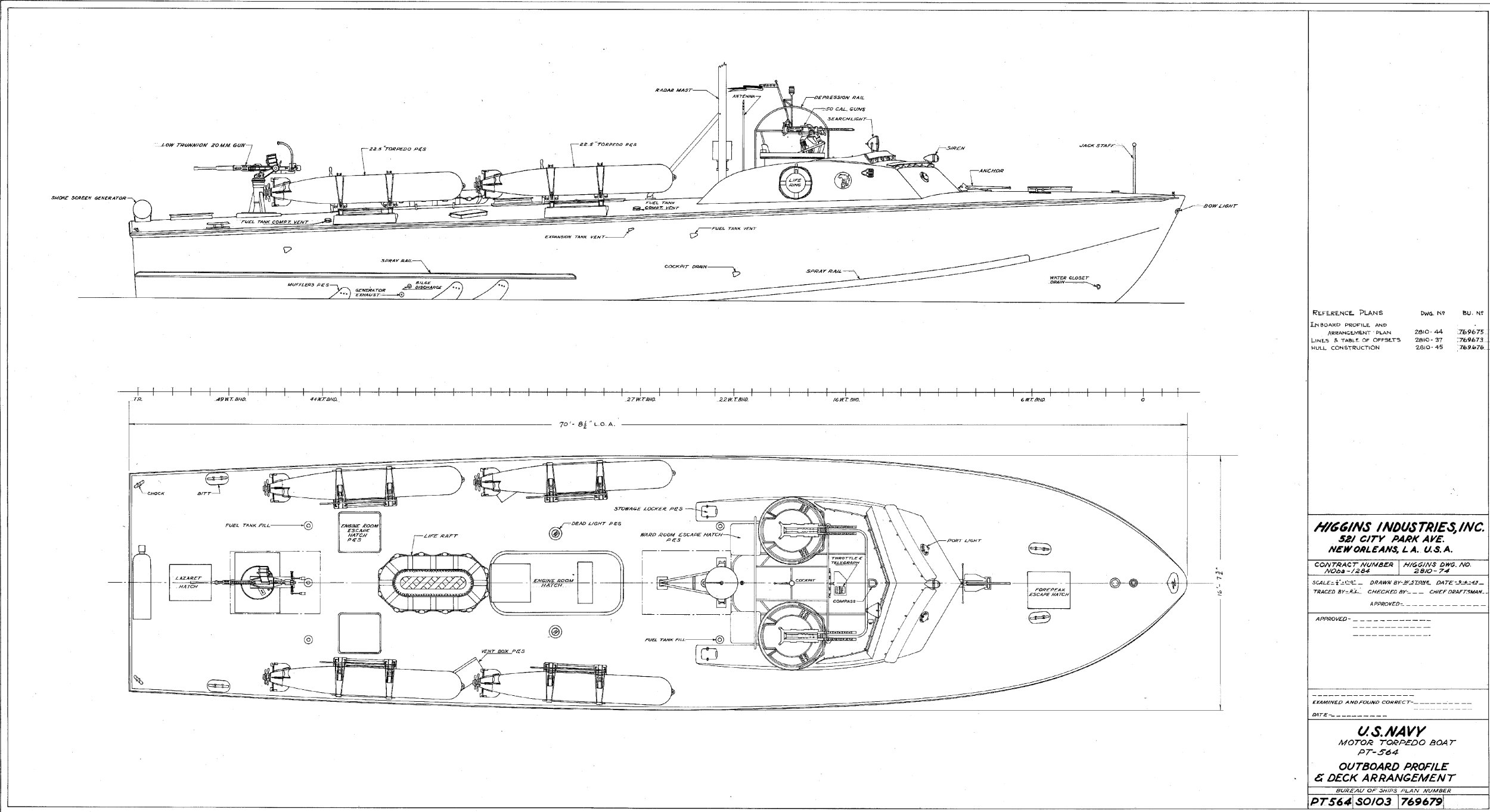

Higgins 70′ “Hellcat” PT-564

Laid down in 1942, Comp. 30 June 1943, comm. August 1943. She was a high speed (46 kts), low silhouette new prototype. A Board of Inspection and Survey showed trials in September in which she reached 47.825 knots on full-throttle mile run. By November it was decided however not not put her on production as she was less maneuverable, costier and more complicated to build.

In service from 2 September 1943 and assigned to MTBRon 4 by November 1944 (Lt. Comdr. Jack E. Gibson) in the training squadron based at Melville, RI. It was 28 boats strong, for Higgins boats crews. Squadron 4 later was sent to the Solomons in the Operational Development Force (advanced training), stricken in February-March 1946. After 1948 she was sold to the IDF Navy as MB-200 and reequipped with a single 20mm/70 Mk 10, still the two twin 12.7mm/90, four 572 TR, and SO-13 radar. See the interior arrangement.

Specifications: 40 t, 70 x 20 x 4-ft 6-in, 3 props 1,500shp Packard W-14 M2500 46 kts, armed with 4x Mk XIII 21″ torps, 2×2 .50 cal. 1x 20mm mount

Canadian Powerboat 70 Footer:

The serie comprised the PT-368 to PT-371. They were Scott-Paine designed boats built in 1942 by the Canadian Power Boat Co., Montreal, Quebec, and acquired by the Navy 21 November 1942, Comp. 19 April 1943. Originally planned for the Dutch KNIL, then Caribbean, acquired under reverse lend-lease from the Dutch Government but converted to Elco standard at Fyfe’s Shipyard in Long Island and reassigned with Elco’s 80 footer PT 362-367 made in Harbor Boat Building Co. in California.

They were in service with MTBRon 18 (Lt. Comdr. Henry M. S. Swift, USNR) assigned to the Southwest Pacific. They saw combat in Dreger Harbor, Aitape, Hollandia, Wakde, and Mios Woendi and Kana Kopa (New Guinea), Manus (Admiralties) and at Morotai (Halmaheras). They ended in San Pedro Bay, Philippines.

Specifications: 33 t, 70 x 19 x 5 ft, 3x 1,500shp Packard W-14 M2500 for 41 kts. Crew 12, 2x 21-in TTs, 1x 37mm, 1x 20mm, 2×2 .50 cal. MGs.

Special Hull Prototypes:

-98 footer Aluminum PT-809:

-89 footer Aluminum PT-810:

-94 footer PT-811:

-105 footer PT-812:

Main Types (The three sisters)

Huckins 78 footers (1943)

Huckins 78 footers (1943)

Huckins PT95 during sea trials

The Very Best and Finest PT boats

During the “plywood derby”, Huckins presented a prototype which cost the company $100,000 in 1940. It was trialled, selected, and refined as the 78-footer. The pre-serie prototype was attibuted the pennant PT-69 and was noted for its quadraconic hull design unique to the company, as well as its robust construction method. It was evaluated in July 1941. It looked very promising and even managed to stand out before its other competitors Elco and Higgins. Huckins was selected for production, but since Elco and Higgins showed they could rapidly ramp up production, the much more modest capacities of Huckins only earned them an order for 18 boats. Few in number and costier than the rest, they were regarded however as the very best PT-Boats of the time. The lucky crews that got attached to them praises their qualities. The finish quality was also of another level, true to their luxury yachting origin.

The Huckins Yacht Corporation under wartime industrial procurements had to share their Quadraconic Hull construction, to be licenced to Elco and Higgins as their robust laminated hull as well. Huckins was indeed renowned for its fine yacht designs and that’s whyt it is seen here first. Elco and Higgin’s performances are largely attributed to this technical expertise from Huckins.

Huckins boats weighted 40 tons (unladen) and used Packard marine gasoline engines (3M-2500, 4M-2500 and 5M-2500 in 1945) rated for 1,350 horsepower each and more. These derived from the 1925 “Liberty” aircraft engine. Although standard speed was 39 knots, they proved able to reach 42 knots on trials, and to maintain this even in rough waters.

Their design was peculiar with a bridge amidships, long bow deck, torpedo tubes in inline pairs angled on the sides, typically two twin Browning 0.5 cal. in standard turret amidships, stern light 40mm Bofors cannon and one to three 20 mm Oerlikon forward, plus two stacks of four depth charge throwers aft. The crew ranged between 11 (minimal) and 17 (1945) manned by two officers, to the Lieutenant grade.

Despite their qualities, the small quantities meant the USN, which regarded standardization as paramounts, wanted them not on the frontline, but rather assigned to specific defensive patrolling of sensible areas and crew training. PT-95-97, the first production boats (PT-69 was the prototype) went straight for training, based at Melville (Rhode Island). The remainder (PT-98 – PT-104) were assigned to defend the Panama Canal Zone and PT-255 – PT-264 Hawaiian waters. The Royal Navy also received ten of them from 1942. The 18 boats delivered were assigned to two squadrons fully filled by early 1943 as ships arrived peace meal.

Huckins PT-69/70

Two similar boats completed and delivered on 30 June 1941, reclassified District Patrol Craft YP-106 by September 1941, Third Naval District stricken in 1945, sold 1947.

The first becam the yacht Atlantis II, British flag in 1961, fate unknown. The second was District Patrol Craft YP-107 same date, discarded

Specs: Displacement 40 tons 72 x 16′ 6″ x 4′ 6″, four Packard V12 M2500 gasoline engines, 630shp on 2 props, for 41.5 knots FL and 43.81 knots (tests). Crew 15, two twin .50 cal. Browning M2, four 18″ torpedoes.

Specs Huckins 78′ PT-95 – PT-102 and Continued (PT-265 – PT-313)

Displacement: 52-56 t. Full Load

Dimensions: 23.93 x 6.12 x 1.60 m (78 x 19.5 x 5 ft)

Machines: 3 shafts 1,500shp Packard W-14 M2500 gasoline engines, 1,050 hp.

Maximum speed: 39-41 knots

Armament: 4x 18in (457 mm)* Ts, 1x 40mm Bofors, 1-3 20 mm AA or 1x 37mm, 2 DCR, 2×12 127 mm RL

Crew: 17

*Initially two 21-in TTs

⚙ Higgins Boats 1st Continued series (USSR) |

|

| Displacement | 52-56 t. Full Load |

| Dimensions | 23.93 m long, 6.12 m wide, 1.60 m draft (78 x 20′ 8″ x 5′ 3″) |

| Propulsion | 3 shafts 1,500shp Packard W-14 M2500 |

| Speed | 41 knots |

| Armament | 1x 40mm, 4x 21″ Tr, 2×2 .50 cal., 1x 20mm mount |

| Crew | 17 |

Elco 80 footers (1942)

Elco 80 footers (1942)

PT-196 “Elcopuss” with her impressive livery More

The 80 ft (24 m) production of Elco Naval Division boats became the largest and heaviest (longest, not beamiest) of the three PT boats standards in WWII and more were built (326) than other types. A paradox given the initial structural weaknesses of the prototypes compared to the other two. In the end, the best (Huckins) was only given a token order in comparison. These 20 ft 8 in (6.30 m) beam were classified as “boats”. The fact that they could be carried (just for transport anyway) on the deck larger freighters forbade them the title of “ship”, in the traditional sense. Still these “boast” could carry smaller ones, at least inflatables.

Other sources production wise gave 385 built, with prototypes rounded to 400. It seems the differencial were boats built in 1945, cancelled on V-Day but completed anyway. 326 could be those effectively seeing WWII.

They were not only the longest of the three, but also the largest, as 80 x 20 ft 8 in (so a ratio of 1/4) for 56 ton displacement. They were given Packard marine gasoline engines, rated at 1,200 bhp each for a total of 3,600. But as war progressed, these engines were upgraded, followed and compensated for the addition of equipments and armament.

They carried three officers, 14 ratings but wcould be operated to as few as 12, compared to 17 for the Huckins boats. Armament was standardized at first to a “light” combnination of a single 20-mm Oerlikon cannon aft, and two twin M2 turreted (0.5 in Browning HMG) or due to shortages, 0.8 in (7.6 mm) Lewis equivalents, four 21-inch torpedo tubes with the “short” Mark 8 torpedo. Later this was expended and augmented, and a larger variety of equipments carried, like smoke dischargers, rocket launchers, radar, etc. Many were “augmented” in the field, such as President Kennedy’s PT-109 which had a 37-mm anti-tank gun fitted on her fore deck.

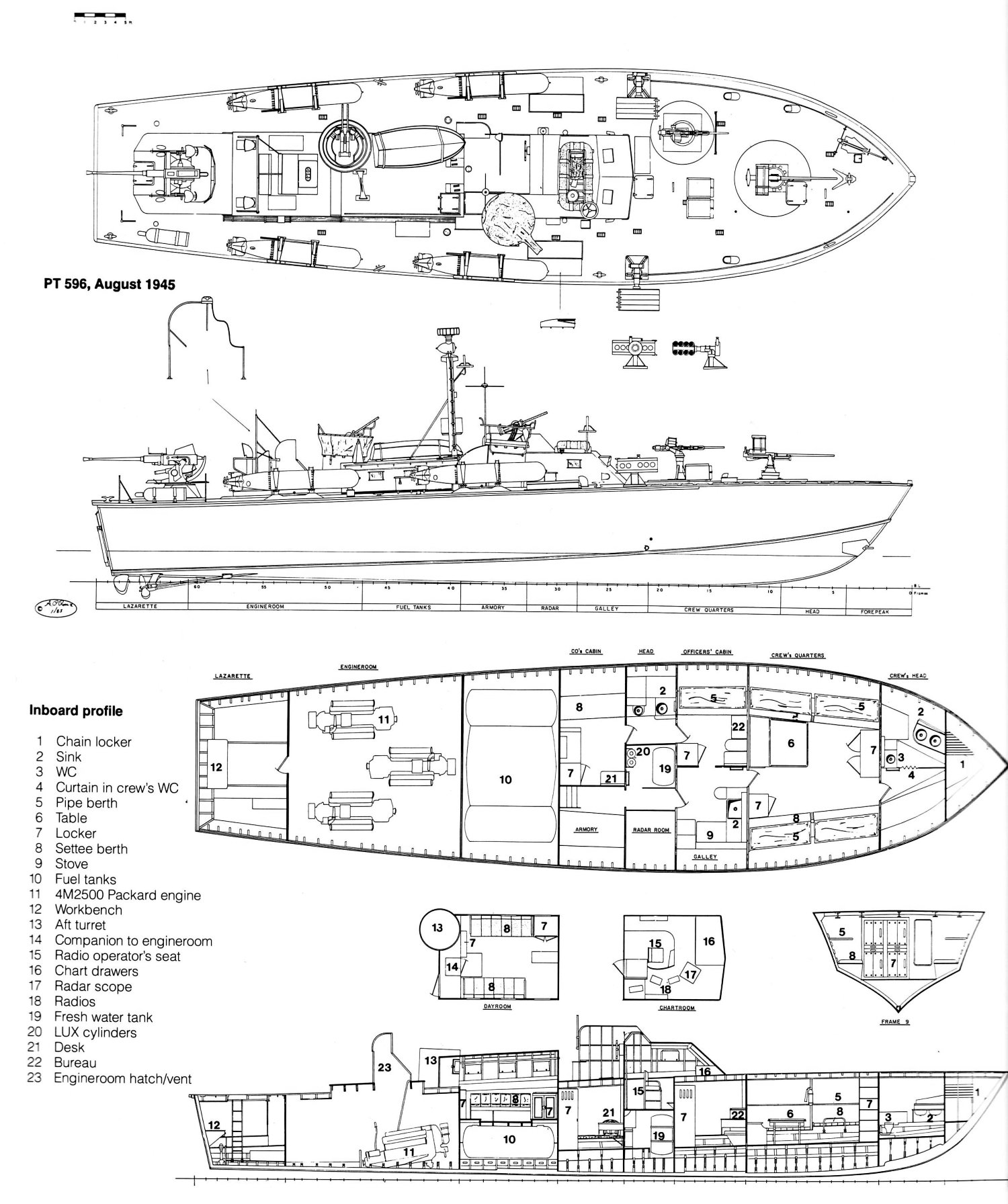

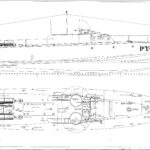

PT-593

Tehnical overview of a 80ft ELCO PT-Boat, Side elevation and deck plans from “Allied Coastal Forces of World War II: Vol. II” by John Lambert and Al Ross, via Robert Hurst on navsrource.

Specs

Displacement: 40 tons, Full load.

Dimensions: 24.38 m long, 6.30 m wide, 1.60 m draft.

Machinery: 3 shafts gasoline engines 1050 hp. Top speed 39 knots.

Armament: 4 torpedoes 18-in (457 mm), 1 x 40mm, 1 x 37mm, 1 x 20m AA, 2×2 HMG 50 cal. (12.7 mm), 2 depth charges, 2×12 5-in 127 mm rocket launcher.

Crew: 17.

⚙ Higgins Boats 1st Continued series (USSR) |

|

| Displacement | 52-56 t. Full Load |

| Dimensions | 23.93 m long, 6.12 m wide, 1.60 m draft (78 x 20′ 8″ x 5′ 3″) |

| Propulsion | 3 shafts 1,500shp Packard W-14 M2500 |

| Speed | 41 knots |

| Armament | 1x 40mm, 4x 21″ Tr, 2×2 .50 cal., 1x 20mm mount |

| Crew | 17 |

Higgins 78 footers (1942)

Higgins 78 footers (1942)

The PTs produced by Higgins, in New Orleans, were 215 units, from PT71 to PT808, but with many cancellations. These were shorter but also wide models. Also 1.60 m deep, their hull was more roomy than the rest and deeper, although narrower than the Elco boats. They could travel 500 nautical miles at 20 knots. In 1944, Higgins also produced the prototype “Hellcat” (PT564) lightened, aluminum, but it could not receive heavy armament and was not followed.

Service wise, Higgins boats joined the frontline later than the ELCO in US service, as the first production batches were sent to Russia and Britain via lend-lease in 1941 (before pearl harbor).

In fact approximately half of the Higgins boats served in the Mediterranean and English Channel, the other half in the Pacific and Aleutians.

The series comprised the following orders:

- Higgins 78′ PT-71 to PT-94

- Higgins 78′ Continued PT-197 to PT-254

- Higgins 78′ Continued PT-265 to PT-313

- Higgins 78′ Continued PT-450 to PT-485

- Higgins 78′ Continued PT-625 to PT-660

- Last serie: Higgins 78′ Continued (PT-791 – PT-808)

⚙ Higgins Boats 1st Continued series (USSR) |

|

| Displacement | 52-56 t. Full Load |

| Dimensions | 23.93 m long, 6.12 m wide, 1.60 m draft (78 x 20′ 8″ x 5′ 3″) |

| Propulsion | 3 shafts 1,500shp Packard W-14 M2500 |

| Speed | 41 knots |

| Armament | 1x 40mm, 4x 21″ Tr, 2×2 .50 cal., 1x 20mm mount |

| Crew | 17 |

⚙ Higgins Boats 5th Continued series* |

|

| Displacement | 48 t. Full Load |

| Dimensions | 78 x 20′ 8″ x 4′ |

| Propulsion | Same |

| Speed | Same |

| Armament | Same plus 1x 37mm, 8x Mk 6-300lb. DCs, 2x20mm |

| Crew | 11 |

*Note: from the last batch, PT-797 to PT-801 were canceled on 7 September 1945 and PT-802 to PT-808 on 27 August 1945.

Specials:

British Elco BTP

British Elco BTP

BPT-1 to BPT-68

They were known as the British Motor Torpedo Boats (BPT), BPT-1 to BPT-68. Built by Elco for Lend-Lease Transfers. PT-49 became BPT-1, Laid down 12 June 1941 and reclassified BPT-1 in July 1941,

Launched 26 August 1941, Comp. 20 January 1942, transferred 4 February 1942, commissioned as MTB-307. They had diverse assignations, moslty the Mediterranean. In the case of BPT-1 she was paid off 10 March 1945 at Palermo in Sicily, transferred to Italy in February 1947 as GIS-0019.

⚙ Elco BPT series |

|

| Displacement | 40 t. Full Load |

| Dimensions | (77′ x 19′ 11″ x 4′ 6″) |

| Propulsion | 3 shafts Packard V12 M2500 |

| Speed | 41 knots |

| Armament | 2×2 Dewandre turrets 0.5 Vickers, 2×2 twin .303 Lewis, four 21-in Torps. |

| Crew | 15 |

Vosper 72 footers (1945)

Vosper 72 footers (1945)

The PTs produced by Vosper in Great Britain, in 1944-45, were 137 planned, smaller, slower but with more autonomy on patrol (570 nautical miles at 20 knots). They had two torpedo tubes in order to revert more to an anti-ship role. These were the PT-368-371, 384-449, 661-730. They had four Depht Charges in chutes but some experimented with powered quadruple chutes.

It should be noted that on the reverse, the US via lend lease procured the RN some 80 PT-Boats:

-Elco MBT-359-268, 307-236, MGB82-93, with 11 MTBs and 2 MGBs lost.

-Higgins MTB-419-423, MGB67-73, 100-106, 177-192, no loss

-Other USN types, MTB269-271 and 273, 274, no loss.

⚙ Vosper series |

|

| Displacement | 45 t. Full Load |

| Dimensions | 22.10 m long, 5.87 m wide, 1.68 m draft (78 x 20′ 8″ x 5′ 3″) |

| Propulsion | 3 shafts 3,375shp |

| Speed | 38.75 knots |

| Armament | 2×533 mm TTs, 1x20mm, 2×0.5 in Vickers AA, 4 ASW DCT |

| Crew | 10-12 |

PTC Boats (1943)

PTC Boats (1943)

Motorboat Submarine Chaser Conversions

Concerned the PTC-1 to PTC-66. Built by Elco. Interestingly enough, after completion from February 1941 they served from 6 March 1941, going to Motor Boat Submarine Chaser Squadron ONE (PTCRon 1) under command of LT. John D. Bulkeley. But the unit was soon abandoned because unsatisfactory sound gear to locate submarines. At least they had a SO-13 (or assimilated) radar. A dedicated article will follow on this type.

⚙ PTC conversion |

|

| Displacement | 27 t. Full Load |

| Dimensions | (70′ x 15’3″ x 3’10”) |

| Propulsion | 2 shafts 1,500shp Hall-Scott Defender gasoline engines |

| Speed | 30 knots |

| Armament | 2×2 .50 cal. Browning M2, 24 depth charges |

| Crew | 11 |

Preserved examples

PT 658 off Portland, still operational.

PT-658 was a Higgins boat originally intended for Squadron 45, Pacific Fleet, but with the war closing, never sent there. In 1958 it was sold to an individual in Oakland, renamed Porpoise and later repurchased by an association, PT Boats, Inc. by veterans which restored her between 1995 and 2005. It is one of the two fully functional afloat example, now on the north bank of the Willamette River in a custom-built boathouse (Portland, Oregon) “PT-658 Heritage Museum”, the Swan Island Industrial Park.

PT-305 was another Higgins 78 footer restored by the National World War II Museum in New Orleans, originally assigned to MTB Squadron 22 (Captain LCDR Richard J. Dressling) which saw action on the coast of Italy, France and sunk a German Flak lighter, F-lighter, and MAS boat, which was more tricky. Restoration was complet in 2016 and she made her sea trials with the US Coast Guard on Lake Pontchartrain.

A few originals survived, not least PT 617 at Battleship Cove in Fall River (Mass.):

PT-617: The end of the war saw most PT-Boats stripped, beached and burned, or scrapped (their wooden structure was not treated to resist much years) but the PT-617, a 80-foot Elco type which survives up to this day, but in static form.

PT-796: On of the very last Higgins boats, she never saw action. Post-war duty with MTB Squadron 1 in the Caribbean and East Coast was followed by towing experiments. In 1961 she was maskeraded as PT-109 for John F. Kennedy’s inauguration, and was decommissioned in 1970. PT Boats, Inc. bought and restored her in 1975 and she is displayed with PT-617 at Battleship Cove. Hr nickname of “Tail Ender” came from her being od the very last batch built.

Famous examples

PT-137

PT-137 was such exceptions, and at the Battle of Surigao Strait, on Oct. 25, 1944. She succeeded in crippling the light cruiser Abukuma, later caught and sunk by B-24 bombers. (see a cutaway). She served with MTBRon 7 (LT Rollin E. Westholm, USN), she served in the Southwest Pacific, seeing action in New Guinea (Tufi, Morobe, Kiriwina, Dreger Harbor, Aitape) and in the Philippine (San Pedro Bay, Ormoc). Transferred to PTBRon33 in 1945, still in the Philippines. She was nicknamed “Snafu”, “Arbie Barbie” and “The Duchess” successively. A full review will be done when tackling the class individually.

PT-109

JF Kennedy’s PT 109 crew

PT-109 skippered by John F. Kennedy while in ambushed was surprised in the night of Aug. 2-3, 1943, by IJN Amagiri in a strait off the Solomon Islands. Rammed, the poor PT boat broke in two, killing two crewmen and injuring Kennedy. Perhaps the best known PT operating in the Solomon Islands, South Pacific with 14 other PT boats sent for a nighttime ambush of four enemy destroyers of the Tokyo express. Most fired their torpedoes and retired by three remained behind to druvey the results, including PT 109. In the confusion, Kennedy mistook a fellow PT for an approaching destroyer and could not manoeuvr fast enough to fire a torpedo. Kennedy and survivors swam 3 miles to a small island, surviving with the help of locals and ultimately being rescued by PT-157.

Mediterranean PT Boats

PT-333 underway off New York, August 1943

PT-333 underway off New York, August 1943

In the Mediterranean Sea PT-Boats were also used for coastal operations, especially well suited for the confines of the Adriatic and of the Aegean Islands. They generally targeted heavily armed German supply barges (F-lighters) sometimes also sinking their escorts, German E-boats. Encounters with Italian ships were rarer, since presence of the USN really started in 1943 (from November 1942 onwards). However when operating around Sicily as soon as they had a port, they tried to at least disrupt the evacuation of the island following the success of Operation Husky. The Italians laid down in particular, dense minefield to interdict the allies to approach. PT boats were thus used to removed some, and penetrate the area. A good career example, PT-6 or PTron15: Casablanca, Bizerte, Pantelleria, Op. Husky, Palermo, Salerno and Invasion of Italy, Maddalena and Bastia, Anzio, Elba, Southern France and Op. Anvil, Leghorn. The three PT squadrons of the Mediterranean were there for 2 years, loosing 4 boats (mines) with 5 officers and 19 men Kia, 7 officers, 28 men wounded. They fired 354 torpedoes, claimed 38 vessels sunk for 23,700 tons, damaging 49 (22,600 tons) and with British boats co-claimed 15 more vessels (13,000 tons), damaging 17 (5,650 tons). “At close quarters” by Bulkley.

Channel and DD-Day PT-Boats

As part of Operation Neptune (D-Day), the allies deployed a number of patrol boats, which had to secure streamline navigation in the English Channel between Great Britain and the Normandy coast. On June 6, 1944, these were the PT-484, PT-552, PT-564, PT-565, PT-567, PT-568, PT-617, PT-618, PT-619, PT-1176, PT-1225, PT-1232, PT-1233, PT-1252, PT-1261, PT-1262, PT-1263. The danger came from U-Boats and E-Boats. The latter sorties indeed: Off Le Havre, four German E-Boots emerged from the screen smoke and went face-to-face with the allied fleet and Force S (Sword) convoy, and a fierce fighting ensued. The escorting Svenner, was hit and sunk. All four E-Boats disappeared bacl into the smoke. None of the PT-Boats met any German ship the first day. They stayed on patrol anyway until more reinforcements arrived the following days and weeks.

PT Boat Supply and Maintenance

Lead vessel of the Oyster Bay class motor torpedo boat tenders (AGP-6/AVP-28), is there anchored in the Leyte Gulf by December 1944 servicing a full squadron. She still had a destroyer armament and could fend off attacks while delivering shore bombardment, acting as much as a base and supply/maintenance vessel. Note by that time, all PT-Boats had a radar and were camouflaged.