US Navy (1942-43): USS Independence, Princeton, Belleau Wood, Cowpens, Monterey, Langley, Cabot, Bataan, San Jacinto.

US Navy (1942-43): USS Independence, Princeton, Belleau Wood, Cowpens, Monterey, Langley, Cabot, Bataan, San Jacinto.WW2 US Carriers:

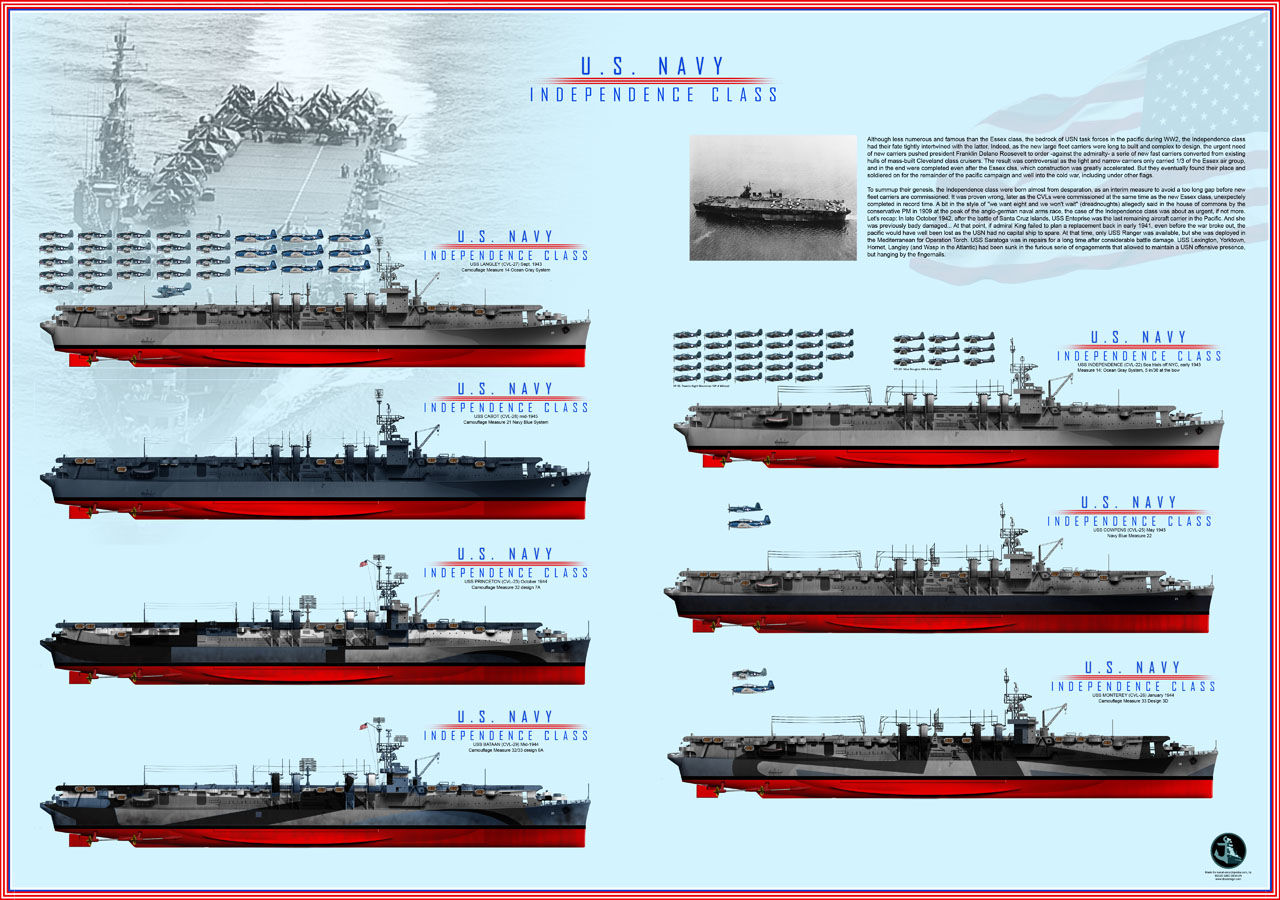

USS Langley | Lexington class | Akron class (airships) | USS Ranger | Yorktown class | USS Wasp | Long Island class CVEs | Bogue class CVE | Independence class CVLs | Essex class CVs | Sangamon class CVEs | Casablanca class CVEs | Commencement Bay class CVEs | Midway class CVAs | Saipan classAlthough less numerous and famous than the Essex class, the bedrock of USN task forces in the pacific during WW2, the Independence class had their fate tightly intertwined with the latter. Indeed, as the new large fleet carriers were long to built and complex to design, the urgent need of new carriers pushed president Franklin Delano Roosevelt to order -against the admiralty- a serie of new fast carriers converted from existing hulls of mass-built Cleveland class cruisers. The result was controversial as the light and narrow carriers only carried 1/3 of the Essex air group, and in the end were completed even after the Essex clss, which construction was greatly accelerated. But they eventually found their place and soldiered on for the remainder of the pacific campaign and well into the cold war, including under other flags.

Context for the “interim carriers”

Launch of USS Cowpens

To summup their genesis, the Independence class were born almost from desparation, as an interim measure to avoid a too long gap before new fleet carriers are commissioned. It was proven wrong, later as the CVLs were commissioned at the same time as the new Essex class, unexpectely completed in record time. A bit in the style of “we want eight and we won’t wait” (dreadnoughts) allegedly said in the house of commons by the conservative PM in 1909 at the peak of the anglo-german naval arms race, the case of the Independence class was about as urgent, if not more. Let’s recap: In late October 1942, after the battle of Santa Cruz Islands, USS Enteprise was the last remaining aircraft carrier in the Pacific. And she was previously bady damaged… At that point, if admiral King failed to plan a replacement back in early 1941, even before the war broke out, the pacific would have well been lost as the USN had no capital ship to spare. At that time, only USS Ranger was available, but she was deployed in the Mediterranean for Operation Torch. USS Saratoga was in repairs for a long time after considerable battle damage. USS Lexington, Yorktown, Hornet, Langley (and Wasp in the Atlantic) had been sunk in the furious serie of engagements that allowed to maintain a USN offensive presence, but hanging by the fingernails.

Genesis of future wartime CVs

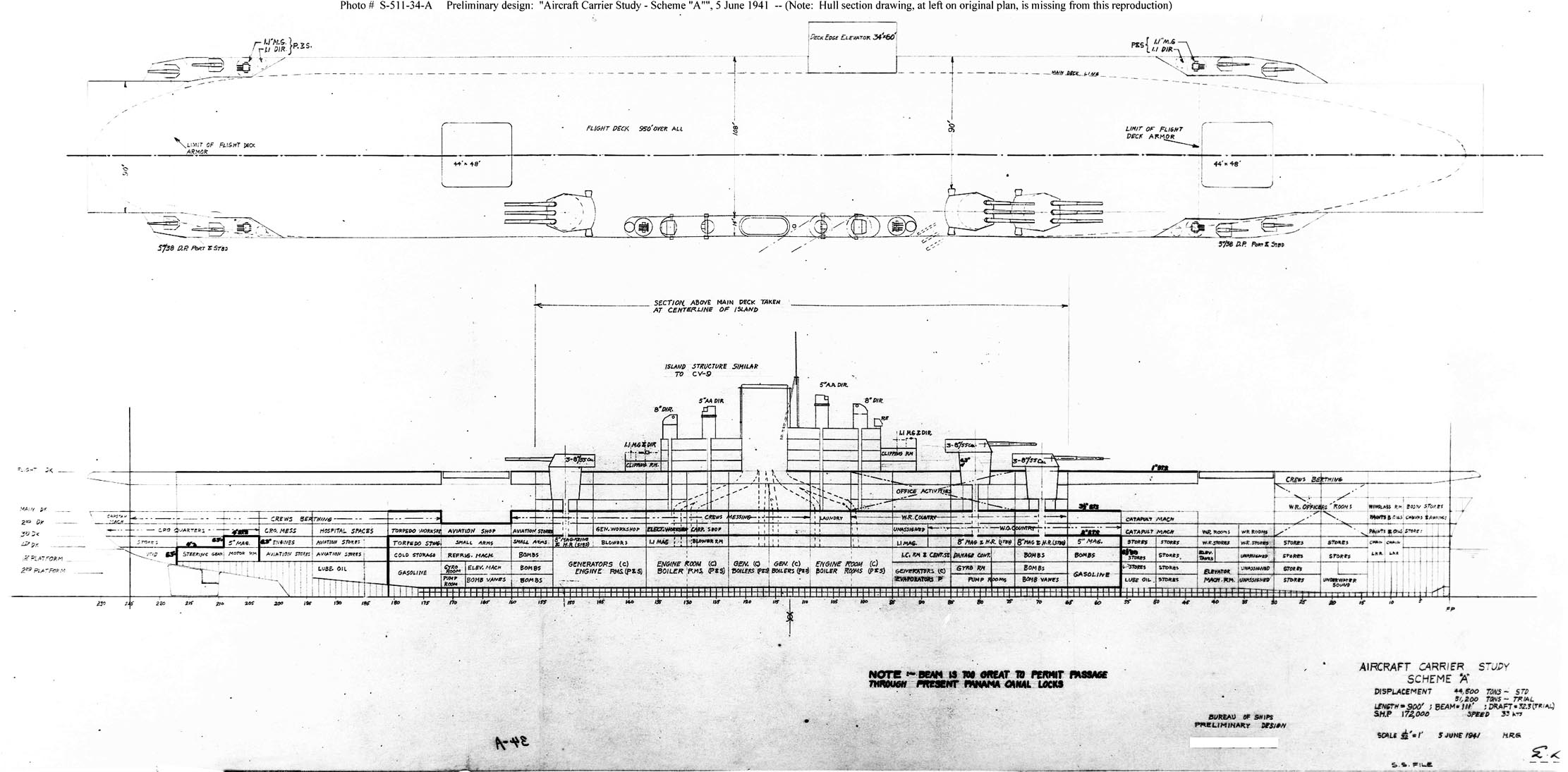

“A” scheme preliminary design study, June 1941: 44,500-ton, 900 ft, 3×3 8″/55 guns, 8x 5″/38 – navsource

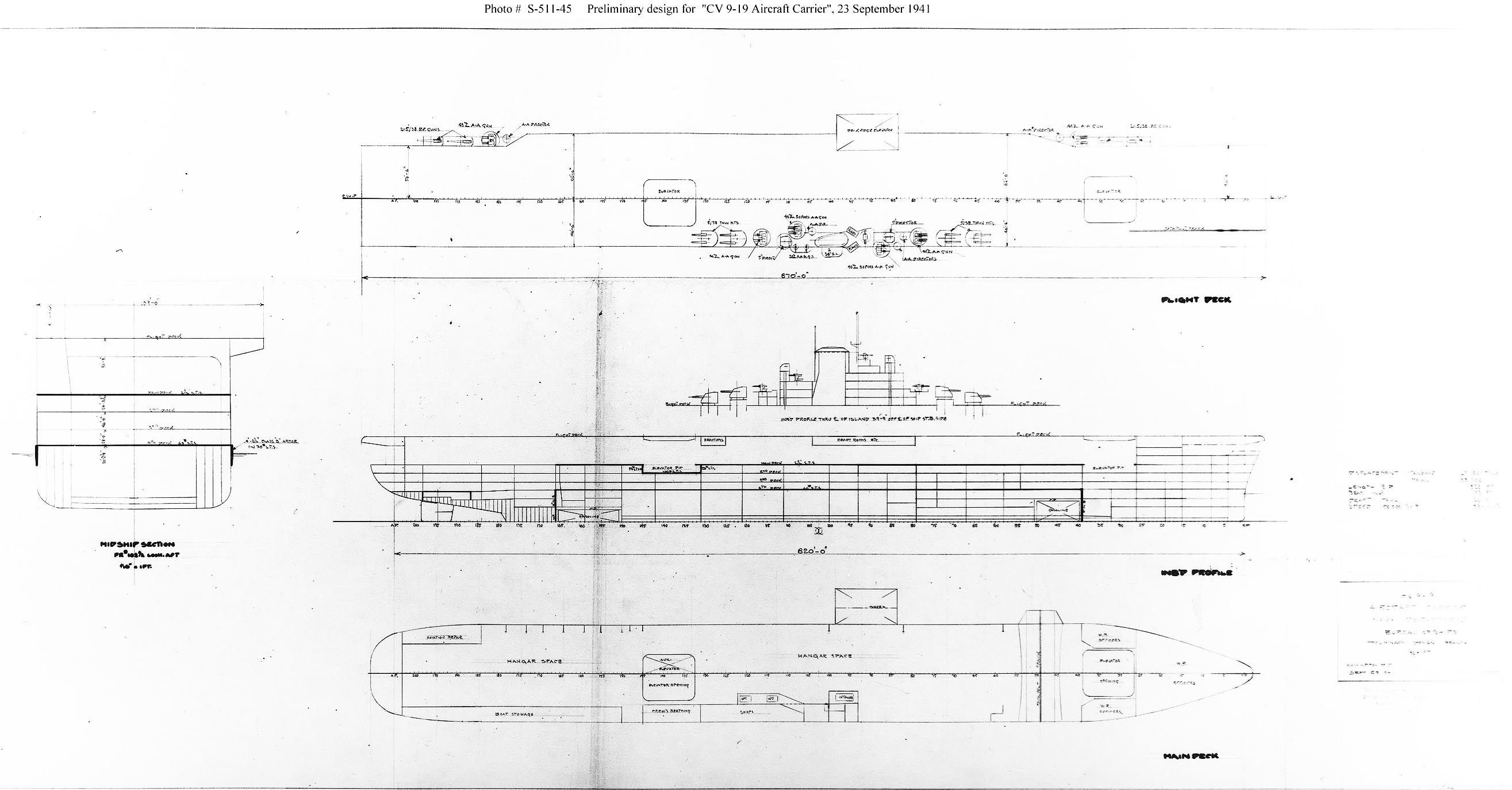

Essex class preliminary design, September 1941

Long before reaching this critical point for the US Navy, as war broke out in Europe in late 1939, it was clear that the admiralty should prepare a new class of aircraft carriers in case the United States would be dragged in it. Peacetime limitations already reached the maximal allocated tonnage with USS Wasp. Therefore if only a state of war could free the admiralty from it, better to have a successor aircraft carrier design ready, one that was also unencumbered by unit tonnage limits. This became the genesis of the famous Essex class, the very bedrock of the USN for the years 1942-45 but also until the 1970s, and one of is most legendary and intrumental warship class ever.

The Essex were planned to carry a large air group as shown in prewar exercises and naval games as well. Larger dimensions also allowed some protection to be carried, contrary to the earlier compromised classes, the best of which were the Yorktown class. The new Essex design took years, right after the Yorktown class was started in fact. They reached 35,000 tonnes fully loaded, 1/3 more than their predecessors and included many innovations in firepower, with, from 1940, a radical increase in AA. However, it’s only on 28 April 1941 that the keel of the first of these ships, USS Essex, was laid down at Newport news, where six new large shapes were built for the occasion.

Two more keels were laid down in September, and two in December, with other Yards created basins for more, at Bethlehem, Quincy, New York Navy yard, Norfolk and Philadelphia. Given the size of the new ships this was an unprecedented industrial effort, unrivalled in history and never surpassed since. At the time however, as President Roosevelt made the point on this new programmes in early 1941, he was given the completion dates of the ships, at best early to mid-1944, given the average construction delays of the time. That meant in case of a war in which nearly all aircraft carriers and capital ships of the USN in the Pacific were wiped out in action in the first year -although very improbable, but in the most likely scenario against Japan, it seems risky to have no replacement for years, whereas even in six months the geostrategic situation could be reversed or dramatically changed.

The conversion order

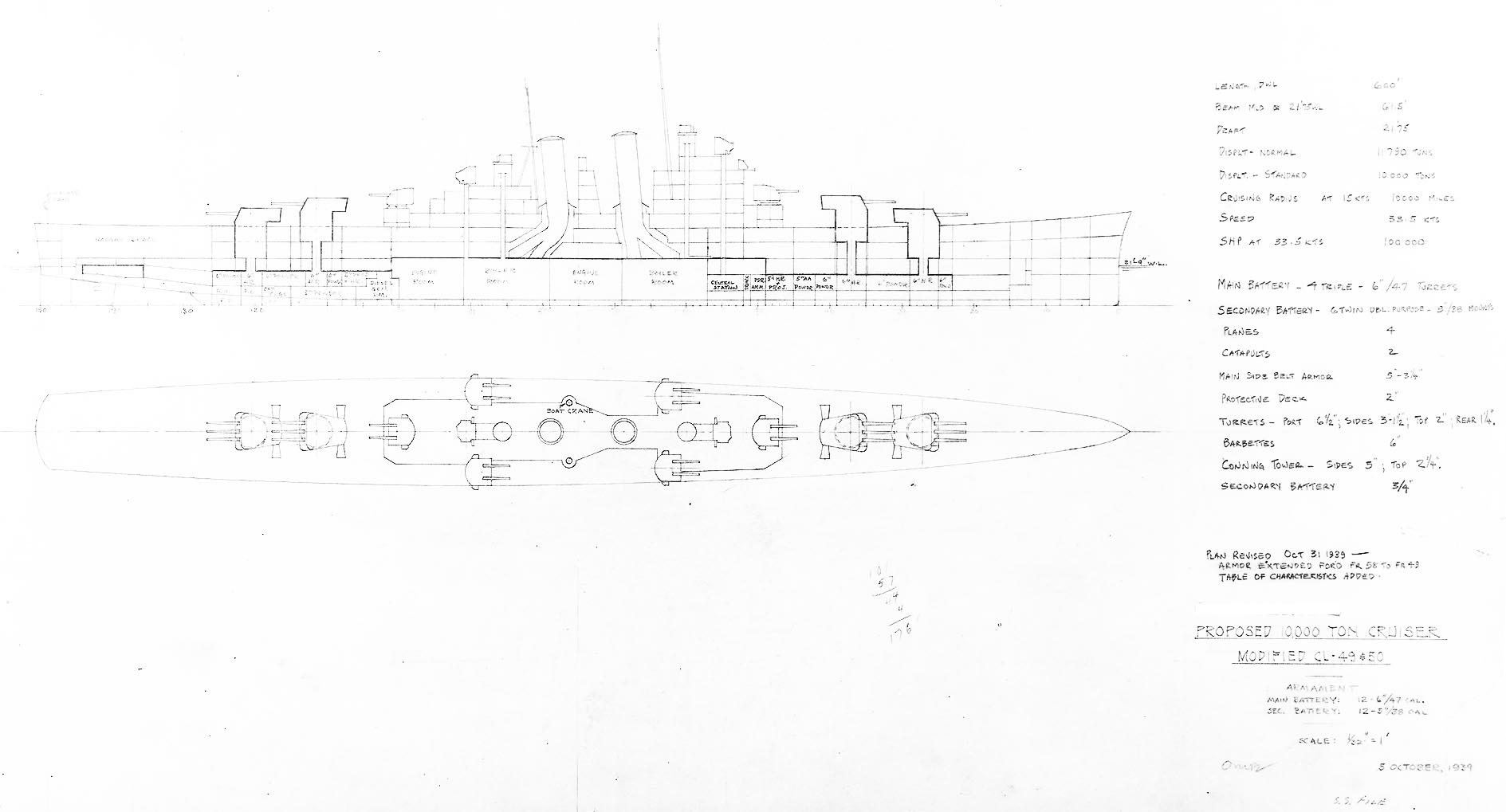

USS Cleveland preliminary design, 1939 “10,000 tons light cruiser”

The Essex class were very large and complex ships, so an intermediate class that could be delivered far quicker was hoped for. There were not many alternatives. A great part of the complexity associated with new built ships were their hulls. On an aircraft carrier, superstructures were very limited and the bulk of a conversion consisted in creating a hangar over an existing deck. Such conversion was already ongoing for Atlantic operations even before the war (see the Long island class) and the conversion took a mere four months to complete ! That meant in case by mid-1941 hulls were requisitioned, completion could be expected in about early 1942 at the earnest, so a full year and more before the awaited Essex. At least that was the prospect.

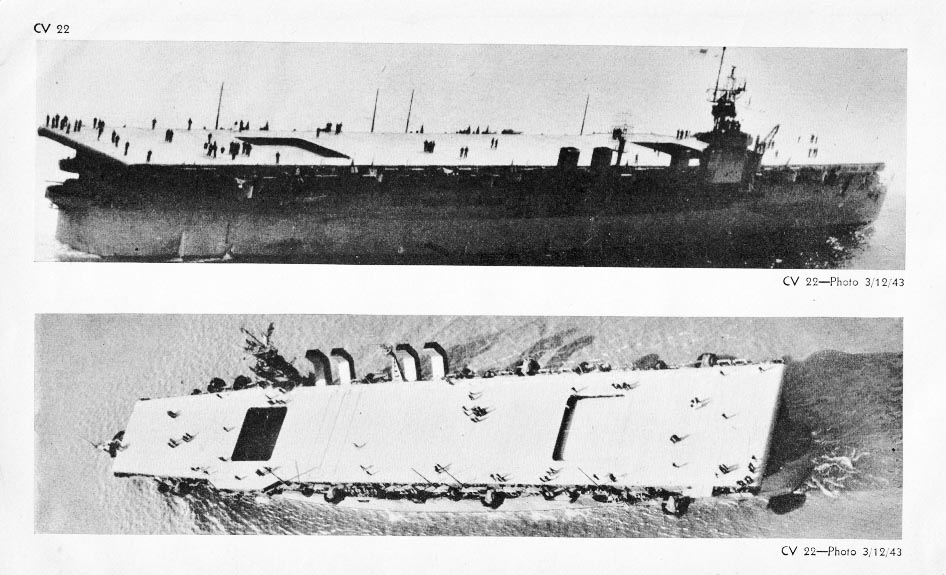

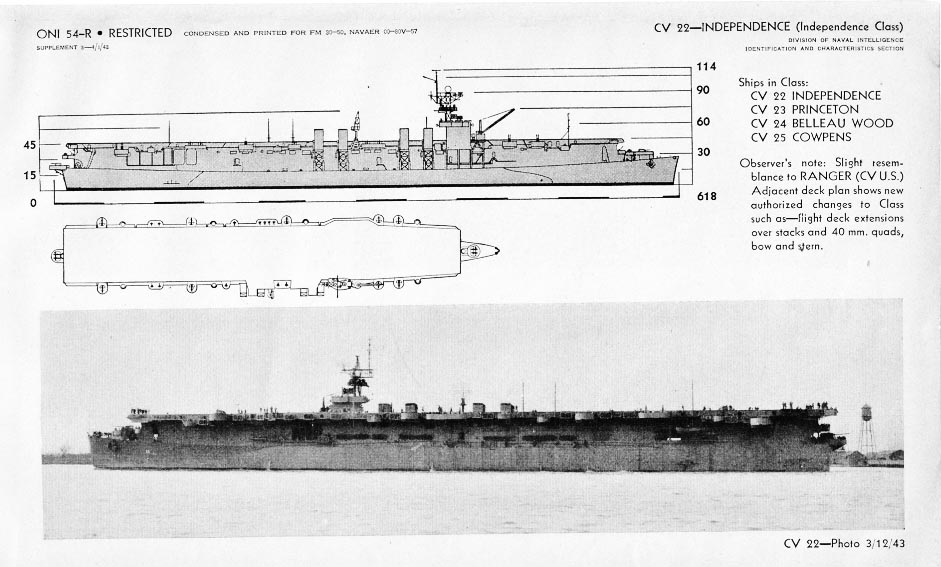

ONI documentation about the class

Discussions with the president on this topic back in July 1941 soon focused on the new hull of the Cleveland-class light cruisers by then started in large numbers. This class soon attracted great interest from the President, as he saw a way to boost naval air power quickly, when war was looming.

He well noted no new fleet aircraft would be completed before 1944 and by himself, in his quality of former naval secretary, proposed to convert many of these new cruisers under construction to carriers.

The admiralty almost immediately objected the small size of a cruiser would only make for a weak air group, not compatible with the USN air naval doctrine of the time. But this was a presidential order, there was no discussion: Studies immediately started at BuShip (Bureau of Ships), for a cruiser-size aircraft carrier. They started with previous conversion ideas, such as one early proposal based on the mediocre Pensacola class.

But as he admiralty suspected, such conversion shown its serious limitations. On 13 October 1941, the General Board placed its veto on the presidential proposal, arguing there were to be too many compromises to these carriers to be effective, a wasted of time and energy.

Admiral Ernest (“Ernie”) King’s commented, after examination of the USS Independence conversion plans in January 1942: “This ship will be a most useful unit, and [her plans] are sufficiently promising to warrant immediate steps towards the conversion of two additional ships of this class. Examination of the prospective dates of completion of the 10,000-ton cruisers…indicates that it would be practicable to select two for conversion now which could be completed at approximately the same time as the Amsterdam. It is further considered that there are sufficient cruisers of this type under construction to warrant conversion of two more ships to aircraft carriers. If the decision is made now the very desirable result will be the completion of three small aircraft carriers at about the end of the year 1942, instead of one as now planned.” Friedman, N., U.S Aircraft Carriers: An Illustrated Design History.

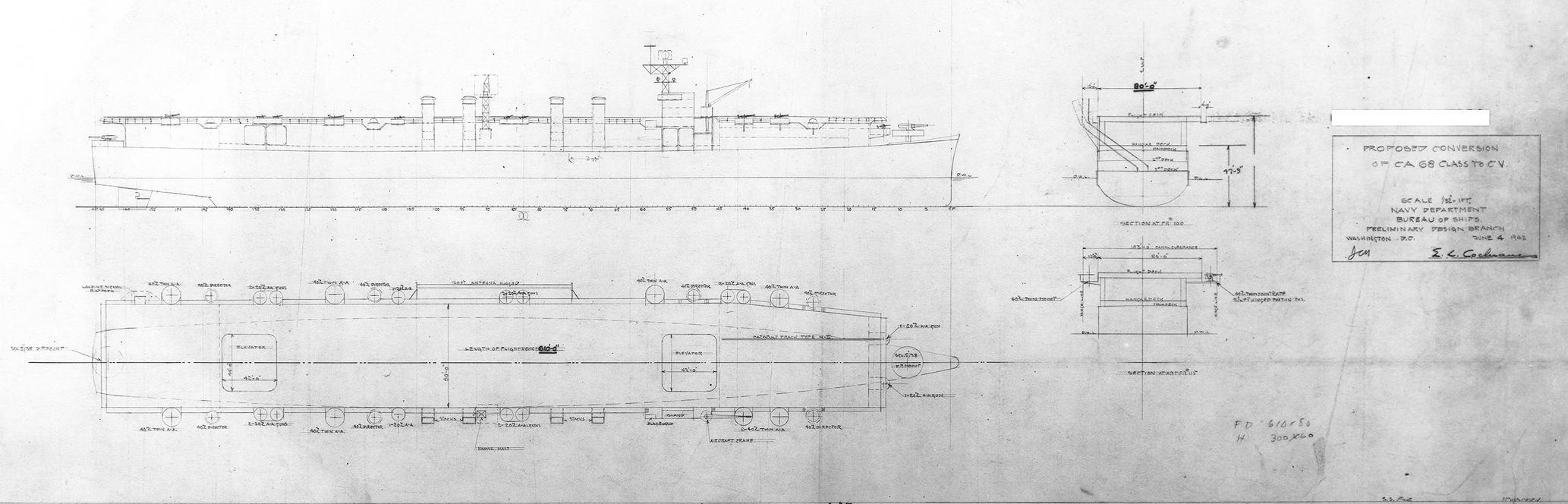

CVL S-511-54-A Proposed Conversion, Preliminary design plan prepared for the General Board during consideration of aircraft carrier conversions of other types of warships. 4 June 1942, scale 1/32, Naval History and Heritage Command.

Undeterred, President Roosevelt ordered another study which was eventually proposed by BuShips on 25 October 1941, this time, Bureau of Ships worked around the clock to have everything fit in and managed to cram in the hangar a larger air group. This second study was submitted to the admiralty, and the latter concluded these aircraft carriers would be this time not mediocre but of “lesser capability”, and available sooner thanks to many design compromises.

As these discussions were still going on, in December 1941 the attack on Pearl Harbor completely changed the dynamic and the admiralty recoignised that more carriers were urgently needed. This was a case of “better something, even sub-par, than nothing”. The Navy therefore approved the second proposal, made recommendations. First, King greatly accelerated construction of the 34,000-ton Essex-class CVs, but still recoignised they would not be ready before 1943 at the earnest. This made the Cleveland-class cruisers conversion the only, and best conversion hull available for an interim carrier at the time, securing the conversion design on hulls already laid down in New York SB.

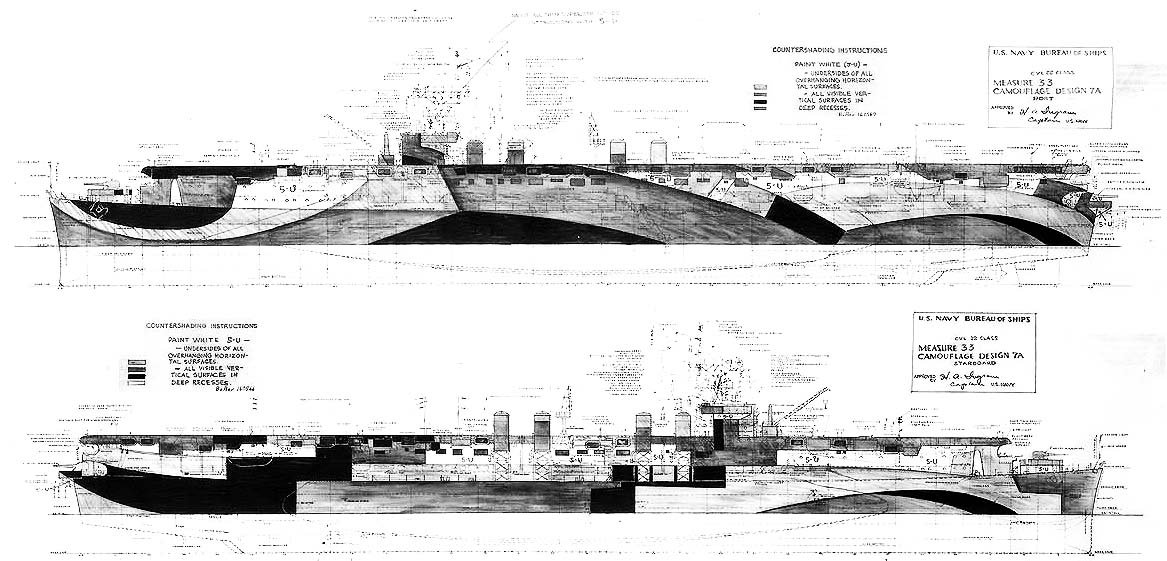

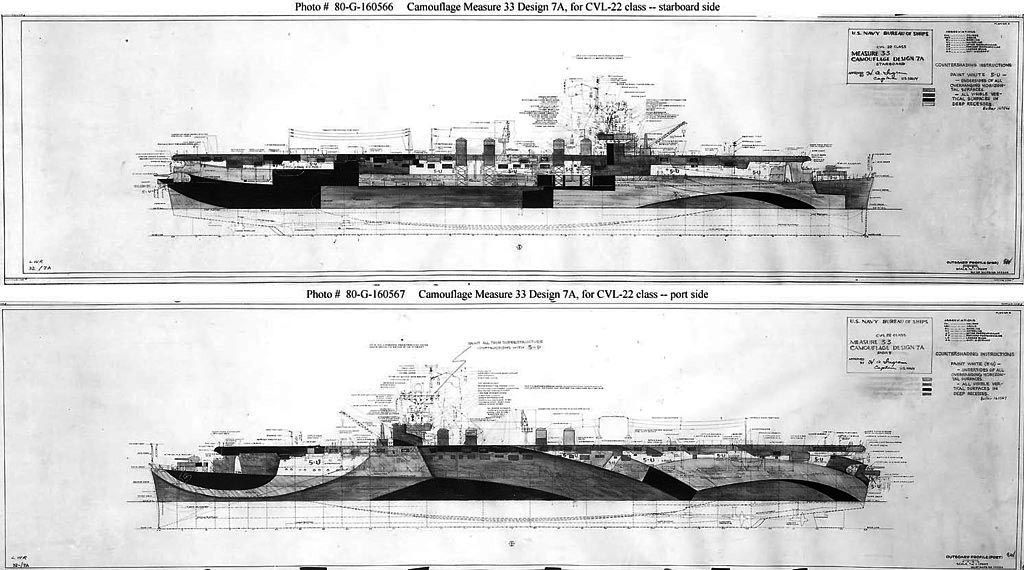

Camouflage Design Measure 33 7A, CVL-22

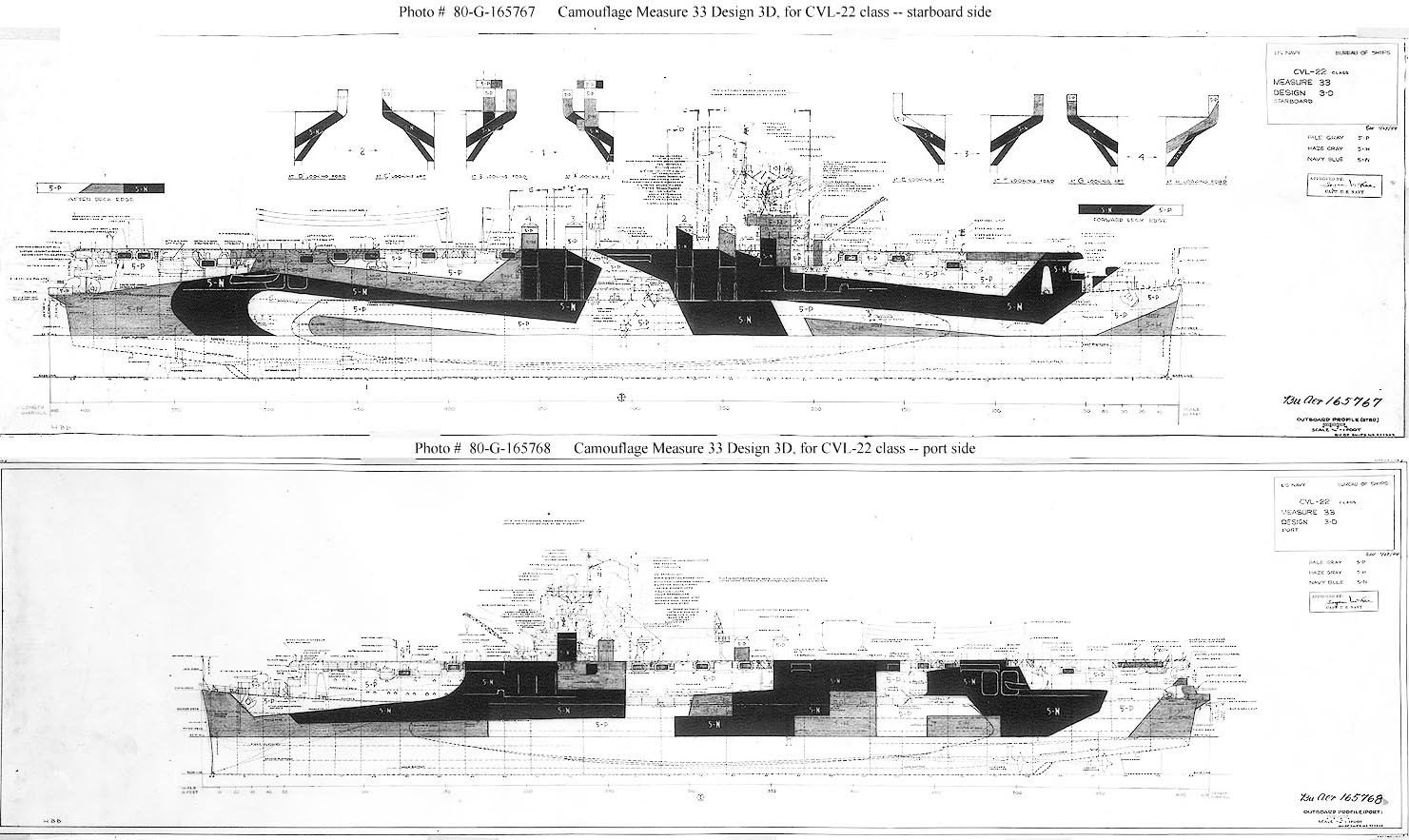

Camouflage Design Measure 33 3D

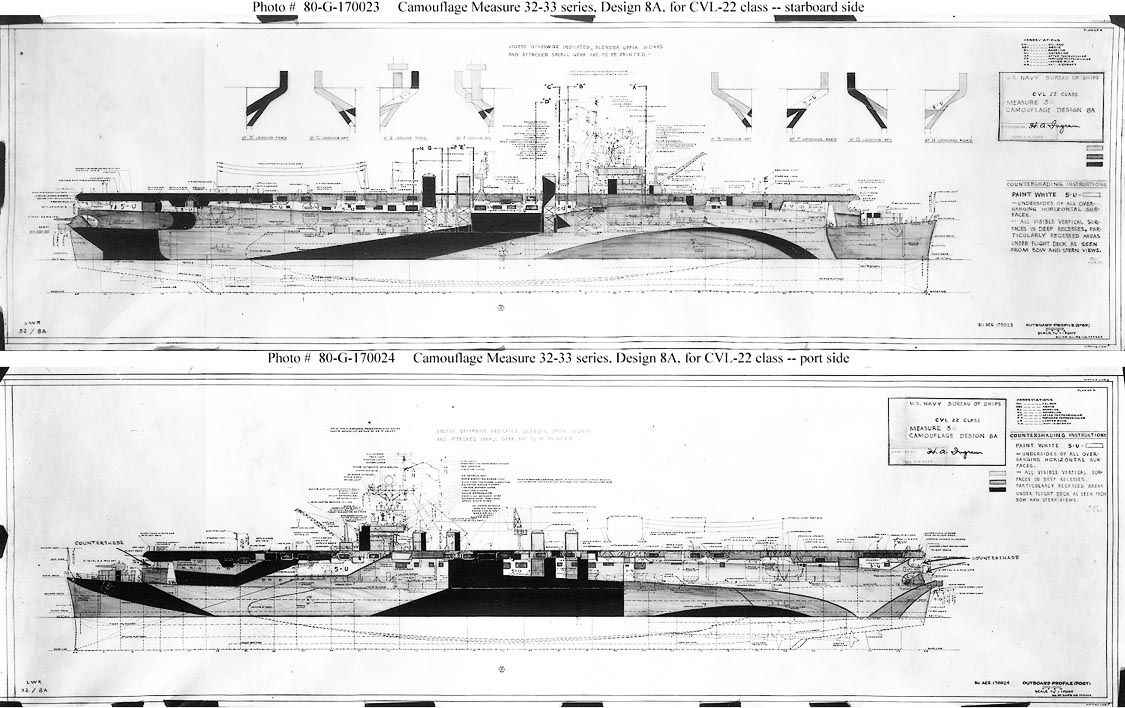

Camouflage Design Measure 32/33 8A

Camouflage Design Measure 33 7A

Conversion and completion of the new CVLs

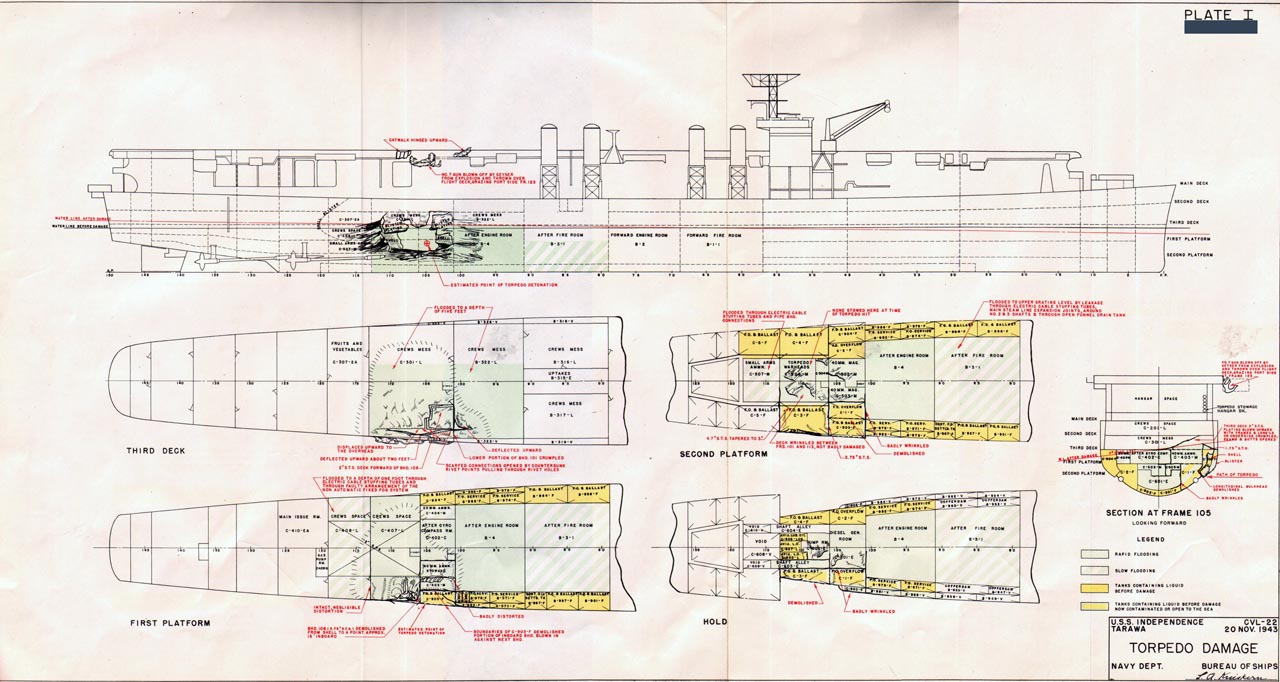

Torpedo damage study showin the internals of the class

Nine hulls were requisitioned at New York SB Naval Yard: Keels of CL-59, 61, 76, 78, 79, 85, 99 and 100, laid down in May, June, December 1942 and January, February, March, May, August and September 1943. After launch, the conversion of the first, USS Amsterdam, CL-59, renamed USS Independence (CVL-22), launched in August 1942, was completed in December 1942, and she was commissioned in August 1943. This was later than USS Essex, with only fuelled more controversy in the presidential choice. But all nine carries were operational in 1943 eventually, with an average conversion time quite reduced after launch. Until commission, it took six months for CVL-22, but this was reduced to four on all other carriers as the first conversion was semi-experimental and allowed to pinpoint and fix many teething problems in the process. Four months was exactly what was expected, in par with the peacetime conversion of USS Long Island, although the Independence class were way more complex. In particular, some alteration to the inner compartimentation of the hull were made, and ammunition and gasoline storage as well. But in the end, most of the work focused on the hangar and deck as expected. Time was spared also in the design of the small island, which was already standard on CVEs (USS Charger, Bogue class, Casablanca, and others). Modularisation allowed to standardize these. In the end, CVL 22 was completed in January 1943 and USS San Jacinto, CVL 30, in December 1943.

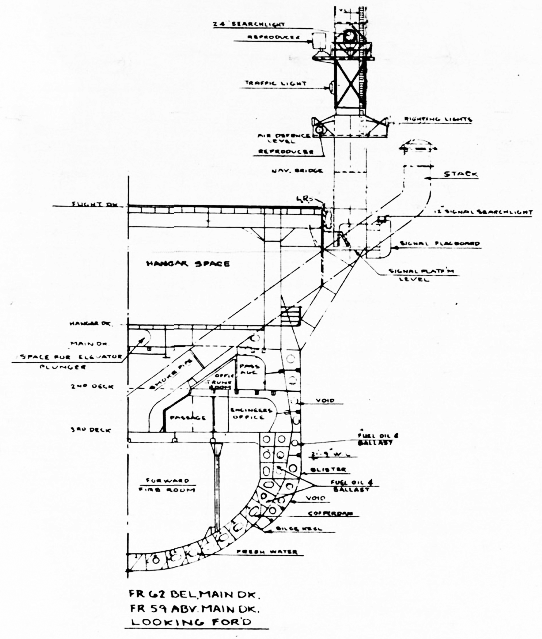

section cut midship showing the engine room, double hull and exhaust pipes

Design of the Independence class (CVL)

The choice of the Cleveland class hull already placed limits on buoyancy and stability. For this reason, the inclusion of an armoured deck was quickly brushed off. The carrier however would have the benefit of the cruiser’s protection, its armoured deck, belt, bulkheads, creating a citadel below the hangar. Engineers managed to place inside the single level hangar 30 aircraft, so 1/3 of the Essex air group. But the real trump card of the design was its speed, inherited from the Clevelands: 31.6 knots. On paper however it was less than for the Essex (32,7 knots), but in all cases, clearly sufficient for fleet service, contrary to all CVEs delivered in between and based on cargos. This granted the USN in 1943 a total of sixteen fleet carriers: seven Essex and nine Independence, the core of task forces mobilized for the island hopping campaign. Given the fact their air group was 2/3 smaller, they were the equivalent of three more Essex-class. Better than nothing indeed.

Hull conversion, hangar and facilities

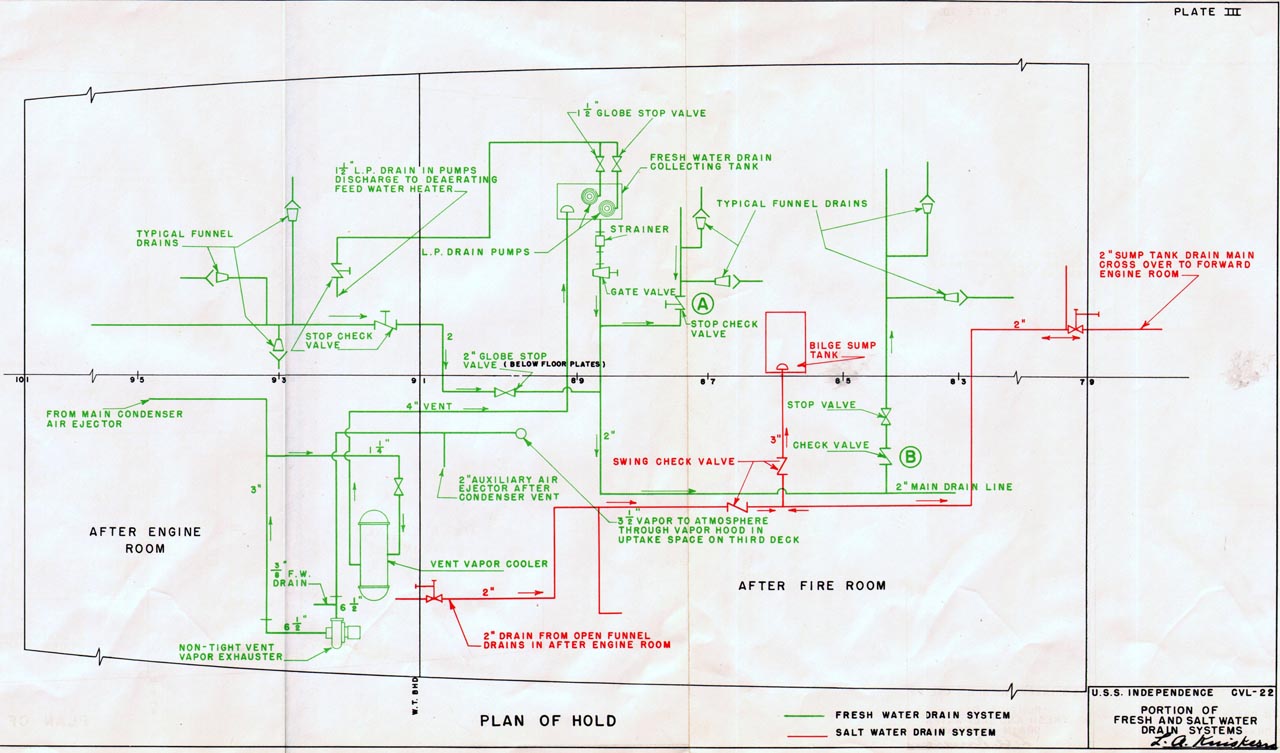

Internal pipes distribution, freshwater system

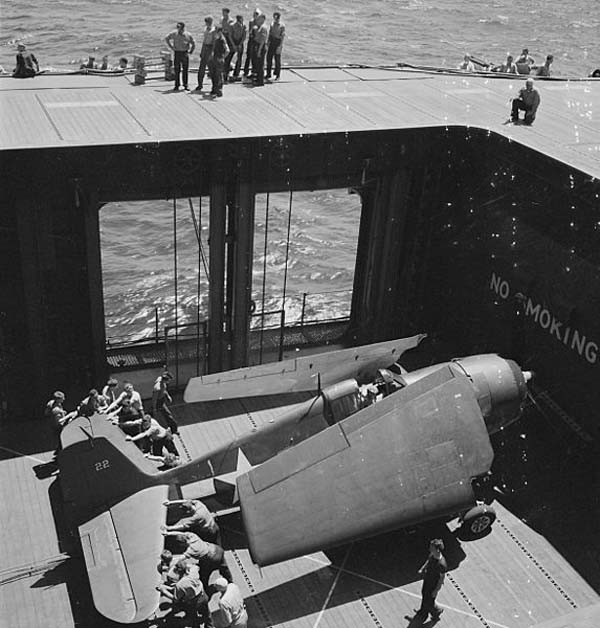

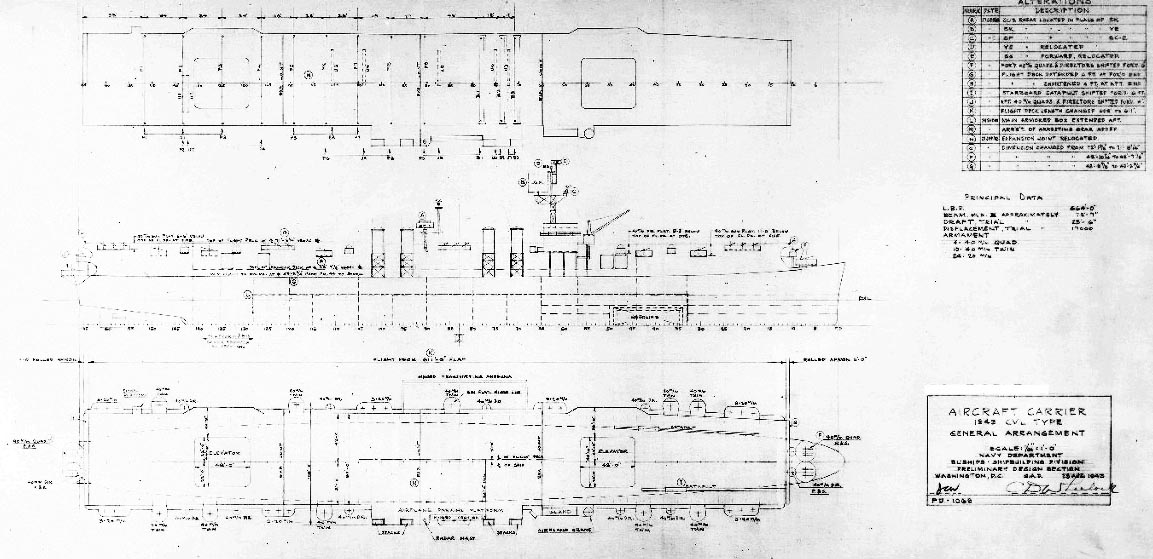

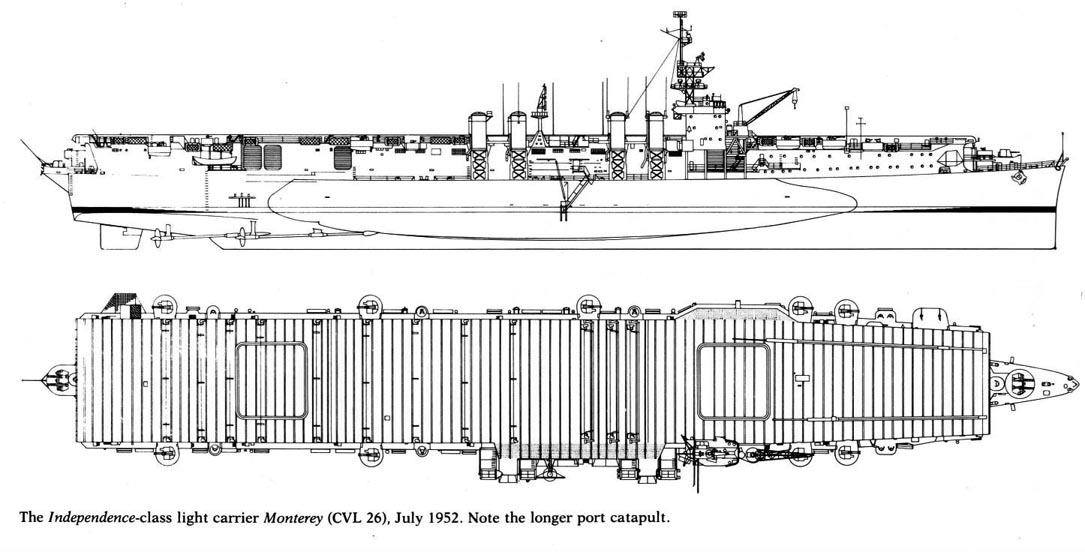

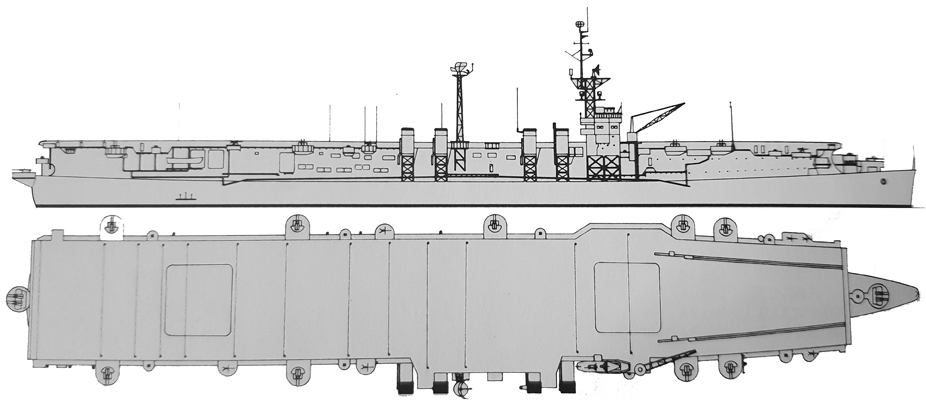

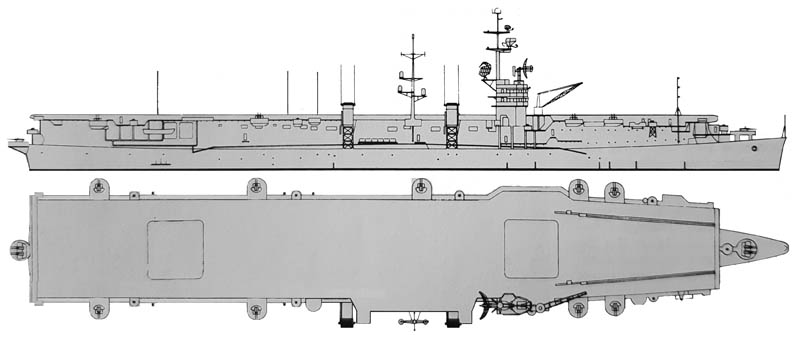

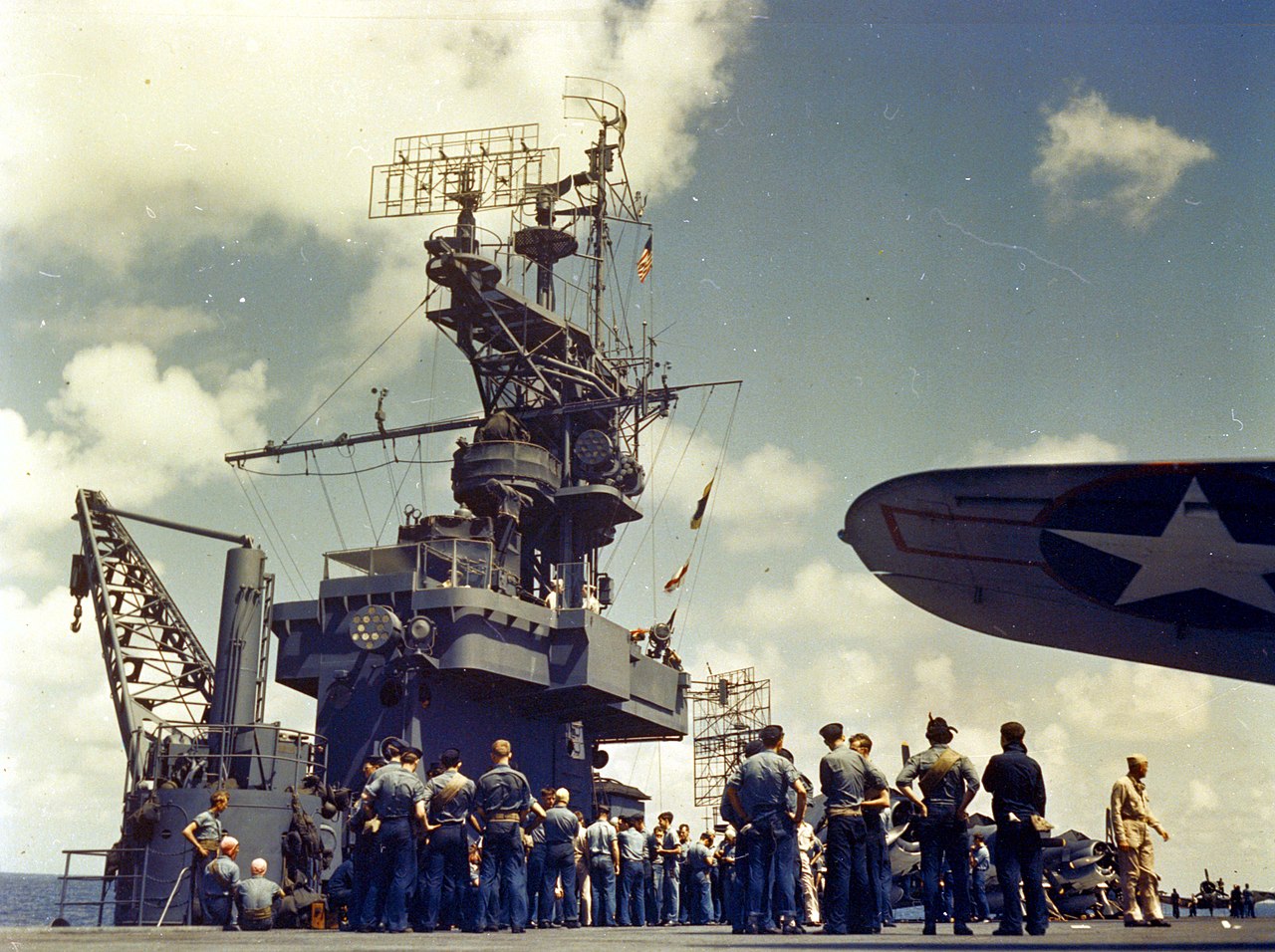

After nine light cruisers were reordered as carriers in the first half of 1942, the design showed a relatively short and narrow flight deck and hangar as a result of the already narrow Cleveland-class hull: A 21,79 meters or 71 feets 6 inches beam, compared to the Essex’ 28.34 meters (96 feets), so 1/3 narrower. As a result, and given the limited overhang needed to place AA defenses close to the deck, ensuring a better arc of fire, the flight deck was only 33.27 m wide (109 fts 2 in), compared to 44.95 m (147 ft 6 in) on the Essex, a good ten meters less. This was the width necessary to have planes parked on each broadside, still leaving extra space for planes landing or taking off. So because of this, aircraft parking was a more complicated affair. The flight deck was basically a rectangle aft, with an extension over the machinery exhaust pipes starboard (the right side), and an other extension port, facing the island, while the flight deck became narrower forward to follow the curvature of the prow below. The four flat-sided pipes were placed amidship with the island in front, placing it about 2/5 forward.

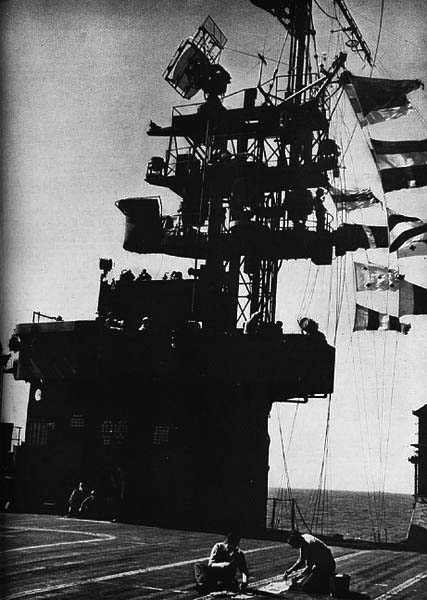

ONI booklet about the Indep. class

This was a small superstructure, with three enclosed levels, with an open bridge above. It supported two small telemeters, one main fire direction post to direct AA fire, and at its rear, a sturdy lattice mast which supported three platforms, a projector, a main aerial surveillance radar and a fire control radar. The combined weight of the island, flight deck, and hangar cause concerns for stability, based on calculated topside weight. Engineers soon devised blisters to be added to the original cruiser hull to compensate. This provided extra buoyancy, extra ASW protection against torpedoes, and increased the original beam by 5 feet (1.5 m) – It was 20.22 m originally (66 ft 4 in). They also had two square lifts about the same size, one abaft the island, behind the lift (the idea being to bring prepared aiecraft directly from the hangar to be catapulted) and the second aft, about 50 m close to the stern. Two hydraulic catapults were placed at the front, with enough gap between them to launch two large size models such as the Helldiver, but not two Avengers. The original design however shown a single hydraulic catapult. It was changed for two for faster operations and in the first modernizations of the 1950-60s, they switched for steam catapults.

All in all many sacrifices were made in order to have them avilable in short time. They had seakeeping difficulties, and were badly battered by Pacific typhoons. Their small flight decks also made operations difficult, if not downright dangerous and they experienced a far higher accident rate than on the Essex-class. For this reason, “rookies” were preferrably sent to the new CVs rather than the CVLs, which kept their pilots for longer in order to stay sharp, or during exchanges with equally small CVEs. Those who left for an affectation on the larger Essex soon saw quite a difference in landing “confort” notably. Being narrower, these carriers also rolled more, only aggravating the problem of a small, narrow landing deck. Still, based on light cruisers, they were fast enough to follow the fleet, unlike the fastest of all CVEs, the Casablanca-class. Their names followed US Navy’s policy and they were all named after significant historic ships or battles.

Powerplant

A major factor when studying the feasibility of a conversion from the light class cruisers to aircraft carriers was the propulsion and powerplant. Engineers had to be sure they cover the needs of both ship types almost without modifications. While the cruisers had a top speed as specified of 32.5 knots, the carriers were 22 feet longer and went for a design speed of 31.5 knots. These could be met by their propulsion plant as it was: With a total ouprut of 100,000 SHP (75 MW), passed through four screw propellers, shafts driven by classic steam geared turbines. For training and logistic it was more simpe to stick with the existing system, there was little automation but dependence to a well-trained engineering crew.

The heart of this system was four General Electric, cross compounded, geared steam turbines. Each was giving 25,000 SHP at normal workable steam pressure. Each set included its high pressure turbine, but also dual flow low-pressure turbines for astern elements. There was also a small cruising turbine for harbour manoeuvers or slow speeds transit (like for the panama canal). These turbines plants were virtual copies of twin 30,000 HP sets from new destroyers. This high standardization across DDs, cruisers and these CVs ensured easy repair and fixes everywhere a repair ship was available.

Superheated steam came at 600 psi, 850 degrees Farenheit. Four Babcock & Wilcox M type, controlled superheater boilers provided it. They could be found also across the fleet. Compartmentation was another interesting aspect of the shared design:

-Four main spaces with alternating firerooms/engine rooms

1-Forward fireroom containing the first two Boilers and turbo generators for electrical power onboard.

2-Forward engine room: Outboard main turbines sets.

3-Aft fireroom, third and fourth Boilers and two more turbo generators

4-Aft Engine Room, two inboard main turbines sets.

The electrical power onboard rested on four 600 kW ship service turbo generators by GE and their switchboards. There was also a 250 kW emergency diesel generator (forward engine room), and a second 250 kW one was aft of the machinery spaces. However the only change here for the carrier was to obtain more electrical power, so these were upgraded from to 750 kW. The only real change in the design was of course, the boiler uptakes relocation. Instead of being ceterline they were directed to the starboard side. Four individual smoke stacks, slab-sided, ended just below and away from the flight deck to void smoke intererence, an old issue since the original USS Langley. Air intakes for the forced draft blowers were placed on either side of these funnel uptakes.

Protection & AA defence

Twin 40 mm Bofors onboard USS Independence. This was the first class with just two “light” AA calibers, a radical choice.

It was clear to everyone that being narrow and small, these CVs have no space free to accomodate some large armament, like the ubiquitous 5-in/38, even in sponsons, but perhaps overhanging places such as the prow. Alas, the latter was so narrow, only 3-inches guns could fit in. However for the sake of simplicity, assuming they would be escorted by cruisers of the Cleveland and Atlanta class, it was decided to give them only light AA weaponry: The common 40 mm Bofors and 20 mm Oerlikon, and this at the end of the design process. They would fit more easily in moderate size sponsons and also found a place fore and aft of the hull under the deck hoverhangs. However this was revised again, and for reasons of training, supplies, and doubts already on the supposedly weaker Oerlikon, it was decided to go for an all 40 mm artillery in the end. Therefore the situation was as follows in 1943:

-26 Bofors 40 mm guns in all, distributed in two quad (fore and aft), 8 dual (9 for the ONI sketch) in large sponsons, two forward, two aft further apart, one more mid-ship port. And sixteen 20mm Oerlikon single mounts, also along the deck in smaller sponsons initially. They were also assisted by ten Mk 51 directors. This was true for CV-23, 23 and 24.

Air group

Grumman F6F-3 Hellcats from VF-25 warming up on the flight deck of USS Cowpens, circa January 1944

Ships of this class carried a small air group – only about 30 aircraft. This was originally set to consist of nine fighters, nine scout bombers, and nine torpedo bombers, but later revised to about two dozen fighters and nine torpedo bombers. In late 1943 and 1944 the typical air group of CVLs comprised the following:

-24 F6F Hellcat fighters

-9 TBM Avenger torpedo bombers

-1 J2F Duck utility amphibian

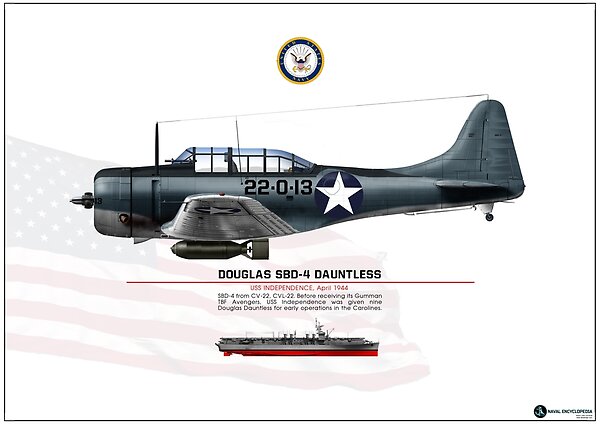

However, upon commissioning it seems USS Independence was still equipped with previous generation planes: Twenty-Eight F3F-3 or F3F-4 Wildcats and nine Douglas SBU-4 Dauntless, soon replaced by the same number of Grumman TBF Avenger. Navypedia states the first two ships were also equipped with some Vindicators, but i can’t find any confirmation. The TBF Avenger became the class standard for strike aircraft. It was the first production model, possibly never replaced on the first three carriers, but the CVL-25 and following had the TBM-1 instead, replaced by TBM-3s in 1945. USS Belleau Wood for example had 25 F6F-5 and 9 TBM-3 in July. The class also operated ten to fifteen Vought F4U-4B Corsair either from 1945 and in the 1950s, noyably for close support in Korea, but completed on USS Bataan by ten to fifteen 10-15 Grumman AF-2 Guardian ASW planes.

F6F taking of from USS Monterey. Note the scene is shot from the open command bridge

F6F Hellcat brought from an elevator

F4U Corsairs onboard USS Bataan during the Korean War, 1953

Now, this calls for comments: There were almost three times more fighters than torpedo bombers:

As the design was finalized and the ship nearing completion it was assumed their smaller size did not favored large planes, and so their limited internal capacity would be maximized by carrying fighter rather than heavier types. The second point was that the main fleet CVs, Essex class, were believed to carry the “big bird” intended to carry out large strikes. The Independence class therefore would assume a role of escorts, and fighter reserve. They could create a large CAP on site (Carrier Air Patrol) and resupply the depleted fighter groups of the Essex-class, sent escorting the strike waves.

It was even thought ideally each Essex class whould team up in a task force with two of these CVLs. So the single squadron of Avenger was really an afterthought. It was there to give the carriers a minimal strike force, in case, for example that while all strike groups from the larger Essex-class would be in the air and another enemy force was spotted, with nothing left to attack it, the CVL could launch their own groups left in reserve. This was also providing them with more tactical versatility in case they operated on their own, in task group detachments and transport escorts.

Grumman F4F-4 Wildcat from VF-22 onboard USS Independence in April 1943. It was replaced later that year by the new Hellcat.

Douglas SBU-4 Dauntless from CV-22 onboard USS Independence also in April 1943. It was replaced by the TBF Avenger at the end of the year. Help support the site !

About the Saipan class

Saipan (CVL-48) in 1955

The very concept of the Independence class conversion made the admiralty thing about an easy way to pursue this concept, but partially eliminating one crucial limitation, that of their air group. The obvious way was to choose the larger cruiser hull, and in that case, those of the Baltimore class heavy cruisers. This idea of admiral King in 1943, for two extra light carriers per year to be ready by December 1945, they were intended to replace losses of Independence class carriers. The larger Baltimore class allowed a larger and more versatile air group on paper, 48 aircraft instead of 30.

The initial idea of giving them ASW bulges was cancelled while protection was similar to the Essex class carriers, and the flying deck was reinforced, the island was based on the Commencement Bay class, the AA battery much increase, still with light 40 and 20 mm. However the second intended pair was cancelled as the war ended. USS Saipan and Wright (CVL-49, 49) were launched in July and September 1945, too late to be cancelled, and so they were commissioned in July 1946 and February 1947 respectively. They served until 1976-77, notably gaining battle stars in the Korean war, deploying helicopters and Douglas Skyraider. They ended as training carriers. Although still carrying 45% the capacity of a Midway class, they were still more valuable than the original CVLs.

1943 CVL Type Preliminary design plan prepared during initial development, 28 August 1943. Alterations in 27 September 1943, 17,000-ton, 664-ft, 1/32 scale (Naval History and Heritage Command).

Cold war service

USS Monterey modernized, during the Korean war.

It would have been a waste of time and energy to scrap the ships after 1945 for that little service, despite their small size making them disqualified for jets. They were mothballed, placed in long term preservation like the rest of the fleet, and some re-emerged at the time of the Korean war. Three were also sold to foreign countries: Two to France, USSLangley, which became Dixmude in 1951, and USS Belleau Woods (locally renamed “Bois Belleau”), in September 1953. For more about these, see the French coldwar section. The third export was just before being sold to scrap: Spain, whih obtained the modernized (after the contract was signed), with the USS Cabot, which became Dédalo, from 30 august 1967. She served until the late 1980s and therefore ebecame the last extant ship of this class worldwide. Unfortunately she was not preserved. For more, see the Armada coldwar section.

USN Carriers: Korea & Cold war service

CVL launching its F6F-5 (stacked aft) and TBM-3E (fwd), Korea, 11 Sept. 1951.

From December 1946, USS Cowpens was in commission reserve at Mare Island, until 15 May 1959, reclassified as the aircraft transport AVT-1. But she was stricken in November. USS Monterey left Japan on 7 September, to repatriate troops, taking part in “Magic Carpet” and made voyages between Naples and Norfolk. Decommissioned on 11 February 1947, Atlantic Reserve Fleet she was recommissioned on 15 September 1950 for the Korean war. She trained for four years with the Naval Training Command, naval aviation cadets, student pilots, and helicopter trainees. She later took part in flood rescue mission in Honduras and was decommissioned on 16 January 1956, AVT-2 on 15 May 1959, but sold in May 1971.

USS Cabot was in and out of commission but in 1948, she was assigned to the Naval Air Reserve training program, off Pensacola. She qualified carrier-based pilots until 1951. She cruised to the Caribbean and made a European waters tour in January-March 1952. Decommissioned, she was placed in reserve from January 1955. She became AVT-3 on 15 May 1959, returned in limited service, loaned, modernized, and took over by the Spaniards in 1967 (see later). When purchased, she was stricken from the US register in 1973.

USS Bataan took part in Operation Magic Carpet, in Europe, from Naples, making two series before inactivated on 10 January 1946 Philadelphia NyD, but converted as an antisubmarine carrier, but in reserve from 11 February 1947. She was reactivated for the Korean war, 13 May 1950, at Philadelphia. Captain Edgar T. Neale took command. She would have the richest combat record in Korea of all CVLs. Bataan spent four months in training operations off San Diego, performing landing qualifications and ASW exercises, loading supplies on 16 November before departing for Japan. On 14 December she joined TF 77 deployed along Korea’s northeastern coast.

Her air group’s on 22 December launched a serie of raids with Vought F4U-4 Corsair (VMF-212) to defend the Pusan perimeter, operating over Hungnam, covering the retreat. She operated with the carriers USS Sicily and Badoeng Strait until 24 December, also flying air reconnaissance, close air support along the 38th parallel. USS Bataan was reassigned to Task Group (TG) 96.9, west coast, and raided North Korean troop concentrations closing on Seoul.

She retired to Sasebo between in January 1951 and relieved HMS Theseus in the Yellow Sea but was back with Task Element (CTE) 95.1.1 to blockade the Korean west coast, making 40 sorties a day, her attack groups destroying rail yards and bridges, but she lost three Corsairs to AA. For two months, she made other patrols and later supported the UN counterattack toward Inchon and Seoul, assisted by St. Paul and HMS Belfast.

In April 1951, Bataan and HMS Theseus retired to the Sea of Japan, resuming the west coast blockade. VMF-312 corsairs operated with British Fairey Firefly and Hawker Sea Fury, attacking Wonsan, Hamhung, and Songjin. She lost five more aircraft. On 22-26 April alone, she flew 136 close air support sorties.

In May she operated with the British carrier HMS Glory, launching 244 sorties also rampaging the Taedong Gang estuary, lossing one plane. Bad weather put an end to these operations. She was relieved on 3 June before heading for Japan and then Puget Sound for overhaul and maintenance. After a stop at Yokosuka on 27 January 1952, and Tokyo Bay in February she embarked VS-25, heading for Buckner Bay (Okinawa) for three large and realistic ASW “hunter-killer” exercises in the event of Soviet intervention. She later embarked VMA-312 at Kobe and resumed operations off Korea on 29 April, relieving HMS Glory (CTE-95.1.1).

HMS Belfast seen from USS Bataan off Korea, 27 May 1952.

Her air group attacked in particular the supply routes between Hanchon and Yonan, with 30 sorties a day, loosing one plane to AA on 22 May. USS Bataan was relieved by HMS Ocean and after a stop in Yokosuka she was back in the yellow sea in June and July, until her departure on 4 August for San Diego and the Long Beach Naval Shipyard.

After her overhaul, and training she was back on site, performing two ASW training operations in Neovember and December. On 9 February 1953, she embarked VMA-312 and relieved HMS Glory as Task Unit 95.1.1 command ship. Her air group struck Chinnampo and the Ongjin peninsula. She made four more line tours in March-May before returning to Yokosuka, and back home via Pearl Harbor in May. After an overhaul until 27 July, armistice was signed but she made a last voyage to Kobe and Yokosuka. Back home she was decommissioned, reserve in the pacific fleet and stricken in 1970. On her part, San Jacinto was decommissioned on 1 March 1947, Pacific Reserve Fleet, San Diego. Reclassified AVT-5 on 15 May 1959 she was kept in reserve and struck on 1 June 1970, sold by December 1971.

La Fayette class

French La Fayette in Along Bay, Indochina, 1953

In the French case, not one but two Independence class were transferred under MDAP. First France obtained USS langley in 1950, renamed Lafayette. On her first trip directly to Indochina she also carried a full load of WW2 air groups. They received their French marking on ther way to Indochina. In 1953, she was joined by a second carrier, USS Belleau Woods, recommissioned as ‘Bois Belleau’. This however was five years loan. They operated their USN piston-engine Hellcats, Helldiver and Avengers. Lafayette served in Indochina until 1953, relieved by Bois Belleau, soldiering there until 1956. Both were later refitted in France, catapults modernized, lattice mast installed as new electronics (radar DRBV 22A). In 1958 a DRBI 10 height finder was installed and they only flew Vought Corsairs, from Toulon. They also took part in the Algerian war while Lafayette in 1956 took part in the Suez Crisis. In 1960, Bois Belleau was returned back to the USN and Lafayette in 1963, both soon scrapped.

French La Fayette as modernized 1959

Bois Belleau departing Norfolk NS for France, just renamed and recommissioned in december 1953.

Dédalo

Spanish Armada Dédalo in 1980

USS Cabot was deactivated in 1947 and mothballed, recommissioned 1948-1955 and in reserve until 1967, loaned to the Spanish Armada under MDAP. In 1973 she was purchased, after full modernization in the US to the latest standards. Decks and lifts were much strenghtened to carry AV8B jets, new electronic equipments were installed, the whole electrical network was overhauled, air conditioning installed, machinery also but halved, with just two funnels uptakes and speed down to 24 knots, freeing space. Hangar capacity was down to 20 aircraft. In the 1980s, the Armada seeked US assistance to adopt the Meroka CIWS and continue to serve with the Prince de Asturias. But this never happened, instead she was returned in 1989 to the US and displayed as a museum ship in New Orleans until 1999. Short of cash, preservation attempts failed, and she was sold at auction and broken up in 2002. Her island survived until the Texas Air Museum, at Rio Hondo, Texas which displayed it, closed. She was the very last remnant of the class still in existence.

Dédalo in 1969

USS Independence 1944, old author’s profile

⚙ Specifications 1943 |

|

| Displacement | 11,000 standard 15,100 FL |

| Dimensions | 190 oa (182.8 wl) x 21.8 x 8 m (622 x 109 x 26 feets) |

| Propulsion | 4 shafts GE TED, 8 Babcock & Wilcox boilers, 100,000 shp (75,000 kW) |

| Speed | 31.5 knots (58 km/h; 36 mph) |

| Range | 13,000 nmi (24,000 km) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Armament | 26× 40mm, 16x 20mm AA, 28-35 planes |

| Armor | High tensile plating over magazine & machinery |

| Crew | 140+1,321 |

Complete overview of all camouflage measures applied to the class. Help this website also by getting the poster or any other merchandise available on the shop.

Read More:

Friedman, Norman U.S. Aircraft Carriers United States Naval Institute (1983)

Faltum, Andrew The Independence Class Aircraft Carriers, Nautical & Aviation Publishing

Wright, C. C. (1998). “Design Histories of United States Navy Warships of World War II- USS Independence

USS Independence wreck survey on noaa.org

Wik entry on the topic

usndazzle.com

Blueprints

About the indep. powerplant

About the CVL camouflage measures

Bow view of USS Cowpens, Mare Island Naval Yard, California, 12 May 1945

Plans and visual resources

Nice 3d view from Jim laurier’s weapons encyclopedia

Model Kits corner

Dragon USS Independence 1943, 1:700 with markings for 2 others. The kit was started by Pit-Road in 1990, reboxed by revell in 1996, and remanufactured by Dragon with new parts and new boxes in 2006-2007. Dragon made it also in 1:350 as well as FlyHawk.

All kits on scalemates

Modellers books includes: USS Independence CVL-22 Warship Pictorial Nr. 40, 2013 by Steve Wiper and “The Independence Light Aircraft Carriers” by Andrew Faltum in 2004.

Videos

decription of the class by navyreviewer

Launch footage

The Independence class in service

USS Independence (CVL 22)

USS Independence (CVL 22)

Early apperance of uss independence in April 1943, with her first air group, VF-22 and CV-22

Form USS Amsterdam (CL-59), launched as CV-22, 22 August 1942 (NY Shipbuilding Corp. she was commissioned on 14 January 1943 under command of Captain G. R. Fairlamb Jr. She passed the Panama Canal and arrived in San Francisco on 3 July 1943, the departed for Pearl Harbor on 14 July and after 2 weeks of training with Essex and Yorktown, was prepared for the raid on Marcus Island, which took place on 1 September, followed by an attack on Wake Island 5-6 October, and the Rabaul and Gilbert Islands strikes, making a supply stop on 21 October. Rabaul was assaulted first on 11 November and she claimed six Japanese aircraft. After a refuel in Espiritu Santo, she sailed to the Gilbert Islands, supporting the invasion of Tarawa, 18-20 November 1943. She also repelled a counterattack on 20 November, shooting down six, but but hit by an aerial torpedo starboard. She steamed to Funafuti on 23 November for emergency repairs, then San Francisco on 2 January 1944 for complete repairs. She was back to Pearl Harbor on 3 July 1944, receiving an additional catapult, and started training for night operations. In late August she was sent off Eniwetok and joined a TF assaulting on 29 August Peleliu island in the Palau. Between night reconnaissance and night CAP (combat air patrols) for Task Force 38, she covered the operation.

uss independence off mare island arsenal, july 1943

USS_Independence_underway_in_early_1943

In September 1944, the fast carrier task force launched strikes against various targets in the Philippines in preparation for the invasion. USS Independence soon concentrated on Luzon. She resupplied and replenished at Ulithi by October and headed later for Okinawa. Her air group participated in strikes against Formosa and the Philippines at large, repelling Japanese air counterattacks. She was in 24/24 operations, with her strike groups by day, CAP by night. She was east of the Philippines on 23 October, as the Japanese attacked. Her Aircraft (part of Task Group 38.2, Rear Admiral Bogan) spotted Kurita’s striking force in the Sibuyan Sea, on 24 October. She flew a strike against Musashi and a cruiser. Her night search aircraft shadowed the Japanese ships until dawn 26 October, until the great Battle for Leyte Gulf. Her planes also chased off and damaged the remainder of these forces at the Battle off Samar, assisting TF38 in finishing off Admiral Jisaburō Ozawa’s diversion fleet, off Cape Engaño. Afterwards she resumed her routine of strikes in the Philippines.

She was back afterwards for another resplenishment in Ulithi, and crew’s well deserved rest 9-14 November 1944, before being recalled to cover post-landing cover operations. This went on until 30 December 1944, followed by a north sweep, from 3 to 9 January 1945, covering the landings on Luzon. She followed Halsey afterwards in the South China Sea, striking Formosa and Indo-China. By that time she ceased night operations, and was back at Pearl on 30 January 1945 for maintenance.

Her last engagement was at Okinawa: After stopping in Ulithi on 13 March 1945 she went to the Japanese home island, launching day strikes on 30-31 March, and providing CAP and more strikes in support of the troops, scoring more aerial kills along the way. She departed for Leyte on 10 June and in July-August made final strikes against Japan. From 15 August she made surveillance flights, discovering and reporting numerous POW camps and cocering landings of Allied occupation troops. She departed Tokyo on 22 September 1945 for San Francisco, via Saipan and Guam. She then took part in Operation Magic Carpet from 15 November 1945, until 28 January 1946.

Instead of other CVLs, the eight battle stars veteran and lead ship of the class was chosen for Operation Crossroads: She took part in the “Gilda” dampage test, Able atomic bomb on 1 July 1946 at 0.5 mile of ground zero. Her funnels and island were crumpled by the blast and she took part in another test on 25 July, then she was towed to Kwajalein, the back home, decommissioned on 28 August 1946 and scuttled near the Farallon Islands off California, 29 January 1951, by two torpedoes. There was some later controversy as it was claimed that she carried at the time barrels of radioactive waste, contamining the Farallon Islands, but this was renied in 2015. She rests 790 m deep at the the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary and her hulk was surveyed in 2016. No radiactiovity was detected and the team took photos of hangar planes and weaponry scattered.

USS Princeton (CVL 23)

USS Princeton (CVL 23)

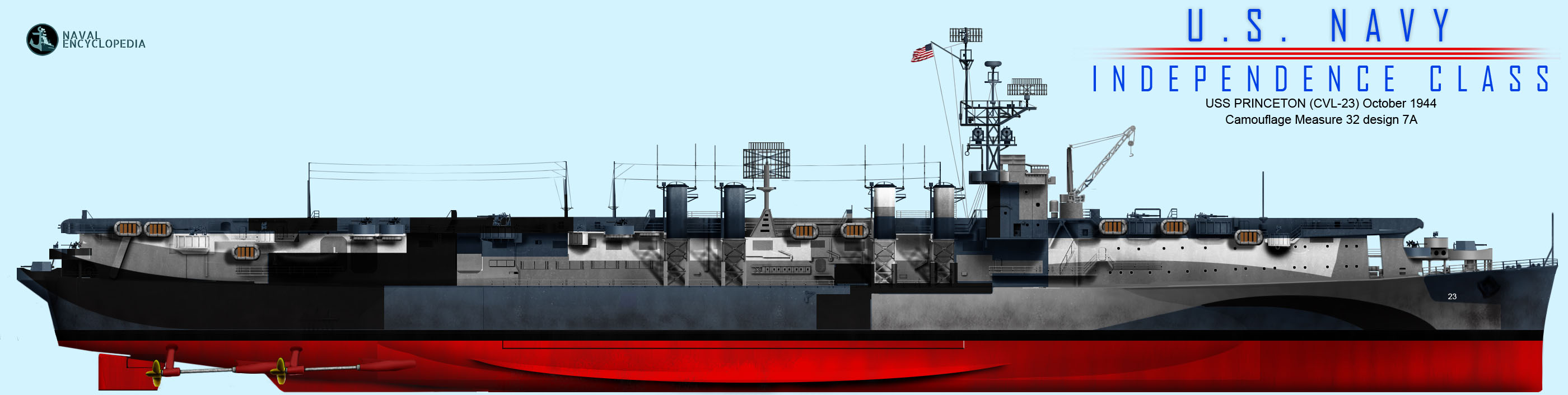

USS Princeton at the time she was sunk. Measure 33, design 7a. This pattern was also used for Cowpens and San Jacinto.

Aft view of USS Princeton, 28 March 1943

Converted from USS Tallahassee (CL-61) at NY Shipbuilding on 2 June 1941, CV-23 Princeton from 31 March 1942 was launched 18 October 1942 and commissioned at Philadelphia on 25 February 1943 with captain George R. Henderson in command. She made a shakedown in the Caribbean, and embarked Air Group 23 for training in the Pacific, off Pearl Harbor in August. TF 11 operated off Baker Is. on 25 August 1943 and the carrier became flagship of TG 11.2 during the attack on Baker on 1–14 September. Her CAP claimed an Emily. She joined TF 15 to raid Makin and Tarawa, before returning to Pearl Harbor. In October 1943, she sailed to Espiritu Sant and there joined forces with USS Saratoga, the centerpiece of TF 38, for attacked on Buka and Bonis in the Bougainville on 1–2 November 1943 followed by operations at Empress Augusta Bay then attacks on IJN cruisers in Rabaul and with TF 50 attacks on Nauru. USS Princeton covered the convoy heading for Makin and Tarawa and was back to Pearl Harbor and the west coast with a load of damage planes to repair. On 3 January 1944, she joined TF 58 and TG 58.4 attacking Wotje and Taroa on 29–31 January and supporting amphibious operations against Kwajalein and Majuro. Her air group destroyed the airfield on Engebi and rampaged installations for three days in the atoll. On 7 February CVL 22 was back in Kwajalein for replsenishment and was back to Eniwetok on 10–13 and 16–28 February, covering the invasion.

The carrier was back to Majuro and Espiritu Santo for replenishment and returned on 23 March for more attacks in the Carolines, raiding the Palaus, Woleai and Yap until 13 April and afterwards a swoop off New Guinea, for the Hollandia operation on 21–29 April 1944, and back for a raid on Truk on 29–30 April followed by Ponape on 1 May. On 11 May, she was back to Pearl Harbor and returned on Majuro on 29 May for another sweep in the Marianas and Saipan. She covered operations there on 11-18 June, attackingGuam, Rota, Tinian, Pagan, and Saipan and participated in the ensuing Battle of the Philippine Sea, contributing alone for 30 kills (pilots) and three for AA. Later her air group attacked Pagan, Rota and Guam. On 14 July, she covered the invasion of Guam and Tinian. On 2 August 1944 after a supply run to Eniwetok, she was assigned to the Philippines, raiding the Palaus en route. On 9–10 September her air group attacked northern Mindanao. On 11 September, the Visayas. She was sent again for the Palau offensive, then the Philippines again, Luzon’s Clark and Nichols airfields. Later she attacked Nansei Shoto and Formosa;

On 20 October 1944 shile she attacked Dulag and San Pedro Bay in Leyte as part of Task Group 38.3, she cruised off Luzon and mostly took on all small airfields threatening the Leyte Gulf for the future landings. On 24 October, Clark and Nichols fields sent their last masses of planes, and shortly before 10:00 a.m. USS Princeton was targeted by a lone Yokosuka D4Y ‘Judy’ which went through her CAP. Against this dive bomber, her AA was short range and could do little. She took a hit by a single bomb stricking between the elevators, through the wooden flight deck and exploding in the hangar. Soon a massive fire broke out, spreading into gasoline lines, causing further explosions. Soon, Cruisers and destroyers came alongside for assistance, pimping salt water to extinguish the fire, notably USS Irwin on her forward hangar deck section. USS Birmingham soon was also ready to combat the fire.

USS Birmingham coming to help USS Princeton

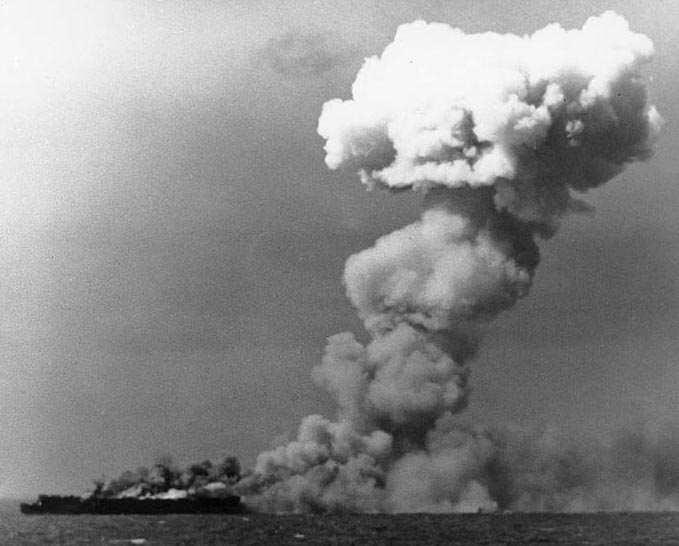

The final explosion, before she sank.

But At 15:24, a second, very large explosion shook Princeton, probably as “bombs cookup” in the magazine. Her superstructure was blasted and she had many casualties, USS Irwin being also damaged. She rescued 646 crewmen, jumping at sea and later received Navy Unit Commendation award. At 16:00, unfortunately, fires were out of control. Evacuation was ordered. After 17:06, USS Irwin was ordered to scuttle her by firing torpedoes, but this failed to torpedo malfunctions. USS Reno camed at at 17:46 but three minutes later an immense explosion tore down CVL 22. The entire forward section blew up. Nearby ships were dhowered by debris miles away, while a massive mushroom was visible by all in the fleet. Crippled, USS Princeton eventually sank at 17:50. Toyal casualties has been 108 men, 10 officers 98 enlisted men. 1,361 were rescued. USS Birmingham in fact also paid a heavy proce for her assistance: 233 killed and 426 wounded. Explosion also destroyed two 5-in guns, two 40 mm and two 20 mm guns. USS Morrison lost its foremast and her portside was smashed by the blast wave, USS Irwin had her forward 5-in, mounts and director destroyed and her starboard side smashed while USS Reno lost a 40 mm. Captain John M. Hoskins, rescued, lost his right foot. USS Birmingham earned a Navy Unit Commendation that day and Lt. Robert G. Bradley was posthumously awarded the Navy Cross as well as executive officer Cdr. Joseph Nathaniel Murphy who assumed command. USS Princeton won nine battle stars for her service.

USS Belleau Woods (CVL 24)

USS Belleau Woods (CVL 24)

USS Belleau Woods fresh from Philadelphia shipyard, 18 April 1943

USS Belleau Woods was started as CL 76 USS New Haven on 11 August 1941, launched on 6 December 1942 and Commissioned on 31 March 1943. She made soon after a brief shakedown cruise and reported to the Pacific Fleet. She was in Pearl Harbor on 26 July 1943. Her first mission was to support the assault on Baker Island on 1st September 1943, then taking part in the Tarawa invasion on 18 September and the attack on Wake Island on 5–6 October, then assigned to TF 50 for the invasion of the Gilbert Islands on 19 November to 4 December 1943. She then operated with the renamed TF 58 (former TF 50) during the attack on Kwajalein and Majuro Atolls an then the Marshall Islands on 29 January to 3 February 1944. She also aparticipated in the attack on Truk raid of 16–17 Februaryand like her sister ships, the attack on Saipan, Tinian, Rota and Guam on 21–22 February. She also attacked Palau, Yap, Ulithi and Woleai on 30 March to 1st April, notably destroying the Wakde and Sawar Airfield layer to secure the operation on Hollandia and new Guinea landings of 22–24 April. Afterwards she partipated in the Truk-Satawan-Ponape raid on 29 April to 1st May and covered after a resupply ren the invasion of Saipan on 11–24 June. This wa followed by the raod one the Bonins on 15–16 June and the first Battle of the Philippine Sea on 19–20 June. Then followed another raid on the Bonins on 24 June. Her air gropup has been credited with the destruction of the Japanese aircraft carrier IJN Hiyō.

Crewmen fighting fires aboard USS Belleau Wood 30 October 1944

She then retitred for a well-deserved hoverhaul and crew’s rest in Pearl Harbor from 29 June to 31 July 1944. She then departed to join TF 58 and the occupation of Guam on 2–10 August. She was next assigned to TF 38, covering the occupation of the southern Palaus from 6 September to 14 October. Afterwards she took part in operations againsy the Philippine Islands on 9–24 September. She covered the Morotai landings on 15 September and made her first Okinawa raid on 10 October. Her ir group next attacked northern Luzon and Formosa until 14 October, Luzon on 15-19 October. Of coutse like most of her sister ships she was present during the epic battle of leyte: She fought at the Battle off Cape Engaño on 24–26 October, fgiving the occasion to her air group to down many more planes. On 30 October USS Belleau Wood east of Leyte had a Japanese kamikaze targeting her. Although it was shot by AA, it crashed on her flight deck aft, penetrating the unarmoured deck and causing massive fire in her hangar, later cooking off her ammunitio supply. Damage control parties were hard at work to save her, with all hands available, and in the meantime she lost 92 men, died or missing. Fortunately she did not followed the fate of USS Princeton and damage was brought eventually under control. But when that arrive, she was almost written-off.

Temporary repairs at Ulithi were made on 2–11 November in a floating drydock and she proceeded to Hunters Point in California, for permanent repairs. This occasion also was taken for an overhaul completed on 29 November 1944: Mdified island, new radar, more AA. She departed on 20 January 1945 to join TF 58 respenishing at Ulithi, arriving on 7 February 1945. From the 15 February to 4 March, she launched her air groups in a serie of raids on Honshū Island, Nansei Shoto, as well as brining close support to Marines landed at Iwo Jima. She carried out a new serie of raids with the 5th Fleet against Japan from 17 March to 26 May and the 3rd Fleet from 27 May to 11 June. She ent to Leyte to receive a brand new air Group, AG 31 at Leyte in June, training them untim 1st July and joining again the 3rd Fleet. There, she took part in the last raids of the war, betwene 10 July to 15 August, claiming for her part a Yokosuka D4Y3 “Judy” (by Clarence “Bill” A. Moore from VF-31, the “The Flying Meat-Axe”. USS Belleau Wood made her last raid on 2 September over Tokyo… for a display during the surrender ceremonies. She earned for her rich service a Presidential Unit Citation and 12 battle stars and remained in Japanese waters until 13 October. Stopping at Pearl on 28 October, she headed for San Diego with more than 1,200 veterans onboard. She made runs for “Magic Carpet”, between Guam, Saipan and San Diego until 31 January 1946. She ended mothballed in San Francisco and was decommissioned at the Alameda NAS on 13 January 1947.

USS Cowpens (CVL 25)

USS Cowpens (CVL 25)

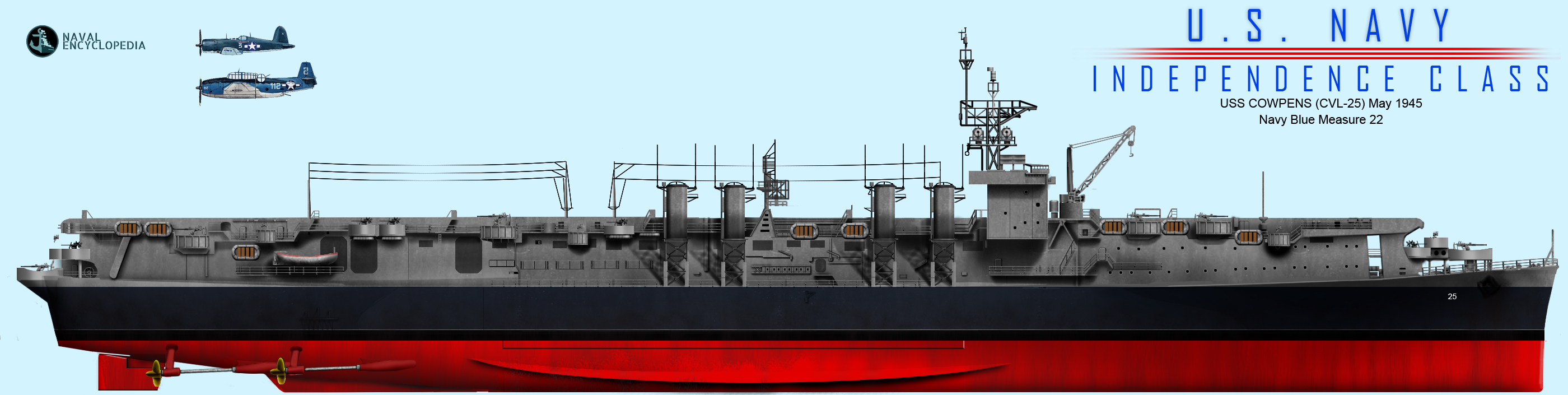

USS Cowpens in 1945, Navy Blue/medium gray graded camouflage Measure 22.

Departing Philadelphia, on 29 August 1943, Cowpens arrived at Pearl Harbor on 19 September to begin the active and distinguished war career which was to earn her a Navy Unit Commendation. She sailed with Task Force 14 for the strike on Wake Island on 5–6 October, then returned to Pearl Harbor to prepare for strikes on the Marshall Islands preliminary to invasion. She sortied from Pearl Harbor 10 November to launch air strikes on Mille and Makin atolls from 19 to 24 November, and Kwajalein and Wotje on 4 December, returning to her base on 9 December.

Joining Task Force 58, Cowpens sailed from Pearl Harbor on 16 January 1944 for the invasion of the Marshalls. Her planes pounded Kwajalein and Eniwetok the last 3 days of the month to prepare for the assault landing on 31 January. Using Majuro as a base, the force struck at Truk on 16–17 February and the Mariana Islands on 21–22 February before putting into Pearl Harbor on 4 March. Returning to Majuro, Task Force 58 based here for attacks on the western Carolines; Cowpens supplied air and antisubmarine patrols during the raids on Palau, Yap, Ulithi, and Woleai from 30 March to 1 April. After operating off New Guinea during the invasion of Hollandia from 21 to 28 April, Cowpens took part in the strikes on Truk, Satawan and Ponape from 29 April to 1 May, returning to Majuro on 14 May for training.

USS Cowpens in July 1943

From 6 June to 10 July 1944, Cowpens operated in the Marianas operation. Her planes struck the island of Saipan to aid the assault troops, and made supporting raids on Iwo Jima, Pagan Island, Rota, and Guam. They also took part in the Battle of the Philippine Sea on 19–20 June, accounting for a number of the huge tally of enemy planes downed. After a brief overhaul at Pearl Harbor, Cowpens rejoined the fast carrier task force at Eniwetok on 17 August.

Then, on 29 August, she sailed for the pre-invasion strikes on the Palaus, whose assault was an essential preliminary for the return to the Philippines. From 13 to 17 September, she was detached from the force to cover the landings on Morotai, then rejoined it for sweep, patrol, and attack missions against Luzon from 21 to 24 September. Cowpens, with her task group, sent air strikes to neutralize Japanese bases on Okinawa and Formosa from 10 to 14 October, and when Canberra and Houston were hit by torpedoes, Cowpens provided air cover for their safe withdrawal, rejoining her task group on 20 October.

USS Cowpens in November 1943

En route to Ulithi, she was recalled when the Japanese Fleet threatened the Leyte invasion, and during the Battle of Surigao Strait phase of the decisive Battle for Leyte Gulf on 25–26 October, provided combat air patrol for the ships pursuing the fleeing remnant of the Japanese fleet. Continuing her support of the Philippines advance, Cowpens’ planes struck Luzon repeatedly during December. During the disastrous Typhoon Cobra on 18 December, Cowpens lost a man: ship’s air officer Lieutenant Commander Robert Price, several planes, and some equipment, but skillful work by her crew prevented major damage, and she reached Ulithi safely on 21 December to repair her storm damage.

Listing badly during the typhoon Cobra

From 30 December 1944 to 26 January 1945, Cowpens was at sea for the Lingayen Gulf landings. Her planes struck targets on Formosa, Luzon, the Indochinese coast and the Hong Kong-Canton area and Okinawa during January. On 10 February, Cowpens sortied from Ulithi for the Iwo Jima operation, striking the Tokyo area, supporting the initial landings from 19 to 22 February, and hitting Okinawa on 1 March.

TBF avenger landing

On 13 June, following an overhaul at San Francisco and training at Pearl Harbor, Cowpens sailed on for San Pedro Bay, Leyte. Along the way she struck Wake Island on 20 June. Rejoining Task Force 58, Cowpens sailed from San Pedro Bay on 1 July to join in the final raids on the Japanese mainland. Her planes pounded Tokyo, Kure, and other cities of Hokkaidō and Honshū until 15 August. Cowpens was the first American carrier to enter Tokyo Harbor.

USS Cowpens 31 August 1944

Remaining off Tokyo Bay until the occupation landings began on 30 August, Cowpens launched photographic reconnaissance missions to patrol airfields and shipping movements, and to locate and supply prisoner-of-war camps.

Men from Cowpens were the first Americans to set foot on the Japanese mainland, and were largely responsible for the emergency activation of Yokosuka airfield for Allied use and the liberation of a POW camp near Niigata. From 8 November 1945 to 28 January 1946 Cowpens made two voyages to Pearl Harbor, Guam, and Okinawa to return veterans on “Magic Carpet” runs.

In Tokyo Bay, 18 December 1945

USS Monterey (CVL 26)

USS Monterey (CVL 26)

USS Monterey, measure 33 design 3d. The same pattern was used for USS Belleau Woods

USS Monterey just completed in the Delaware River

USS Monterey became CVL-26 on 15 July 1943 after commissioning, and after her shakedown cruiser stopped in Philadelphia and headed for the western Pacific, Gilbert Islands on 19 November and helped to cover the operations on Makin Island. She took also took part in Kavieng strikes (New Ireland) on 25 December with Task Group 37.2 and covered the landings at Kwajalein and Eniwetok. She was later assigned to Task Force 58for the Caroline Islands campaign and Mariana Islands campaign, but she also took part in operations in northern New Guinea, and the Bonin Islands until July 1944. She also took part in the first Battle of the Philippine Sea on 19–20 June.

USS Monterey in the Bismarck sea, off New Guinea, attack on Hollandia

USS Monterey made an overhault stop at Pearl Harbor and sailed out on 29 August to participate in strikes against Wake Island on 3 September 1944, and with the TF 38 she participated in strikes in the southern Philippines and the first against the Ryukyu Islands. In October-December 1944 she operated in the Philippines, covering the Leyte and Mindoro landings. She also endured CAPs to fond off kamikaze attacks, until in December, she was damaged by the Typhoon Cobra, blasting her with fierce 100 knots (190 km/h; 120 mph) winds. She was badly battered for two days, lossing some planes as their cables snapped, which also caused fires on the hangar deck.

USS Monterey, Ulithi Atoll, 24 November 1944

Future US President Gerald Ford served onboard USS Monterey and saw this first hand. He later told her was nearly swept overboard as General Quarters Officer onboard. he was ordered to go below to assess the raging fire, reporting to Captain Stuart Ingersoll. The damage team did wonders and the ship eventually survived the storm, but had to sail to Bremerton Yard (Washington state) for repairs and an overhaul in January 1945. She was then back TF 58 and supported Okinawa operations by launching strikes against Nansei Shoto and Kyūshū from 9 May to 1 June. She rejoined TF 38 for the final strike against Honshū and Hokkaidō from 1 July to 15 August.

USS Monterey departed home waters on 7 September, with troops bound for New York City, arriving on on 17 October. USS Monterey stayed there for a few days for all Newyorkers to visit and see the impressive tally painted on her island superstructure: Five enemy warships, several damaged, 5000+ tons of Japanese shipping, 300 planes, and many industrial facilities in Japan. She earned 11 battle stars for her wartime service. She took part in Operation Magic Carpet, making several runs between Naples and Norfolk until decommissioned on 11 February 1947, Atlantic Reserve Fleet, Philadelphia.

USS Langley (CVL 27)

USS Langley (CVL 27)

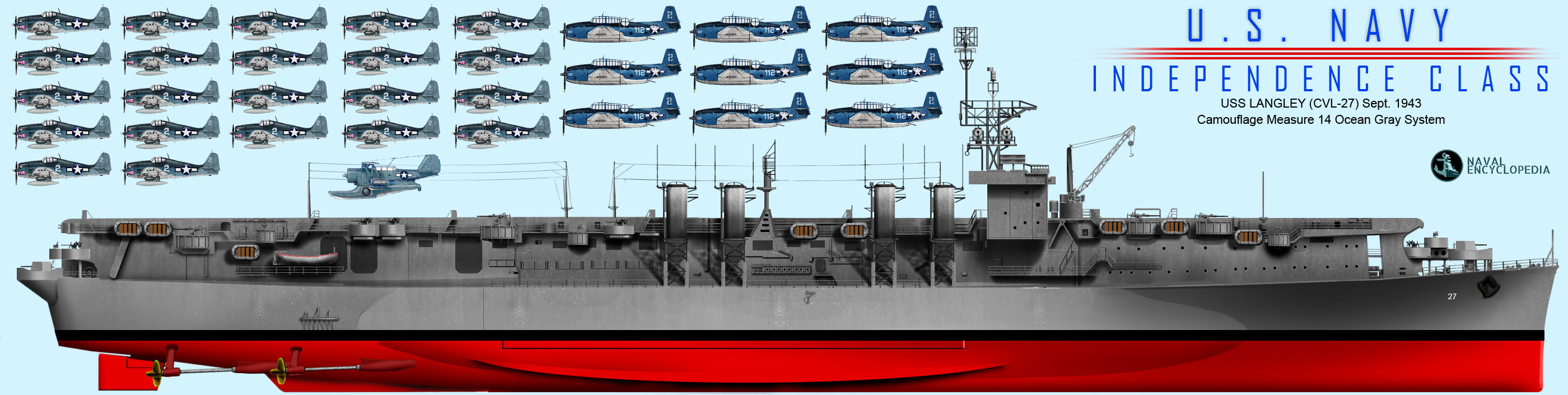

USS Langley in 1943 as completed, measure 14 Ocean Gray.

USS Langley and other carriers entering Ulithi attoll. This became one of the main resplenishment base for the USN, far from Pearl Harbor.

USS Langley (name after Samuel Pierpont Langley) was converted from the light cruiser USS Fargo (CL 85) and retook the name of USS Langley (CV-1), first USN aircraft carrier sunk while transporting planes in February 1942. She was even originally, earlier, being laid down as USS Crown Point (CV 27), at NY Camden in New Jersey, on 11 April 1942. Launched on 22 May 1943 she was commissioned on 31 August 1943 under Captain W.M. Dillon. She made her shakedown cruise in the Caribbean Sea and sailed out frrom Philadelphia on 6 December 1943, bound for for Pearl Harbor for further training.

Her first round of wartime operations started on 19 January 1944, assigned to Task Force 58 in the Marshall Islands. In January-February she with her recently arrived Air Group 32 (CVG-32) she raided Wotje and Taroa Islands for the larger operation of Kwajalein. Later in February she attacked Eniwetok, resupplied in Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides, and was back to raid Palau, Yap, and Woleai in the Caroline Islands (30 March-1 April). She also sailed to New Guinea, covering the invasion of Hollandia on 25 April 1944. Afterwards her air group attacked non-stop for 48 hours the archipelago of Truk, the “Japanese gibraltar”, claiming 35 enemy planes, for loosing just one. Next stop, Majuro on 7 June 1944 and the Mariana-Palau Islands . On 11 June still as part of TF 58 she was part of a 208 fighter, eight torpedo bombers raid against bases, facilities and airfields on Saipan and Tinian. Until 8 August she took also part in the Battle of the Philippine Sea (19-20 June) and its aftermath.

She departed Eniwetok on 29 August with TF 38 (Halsey) for raids on Peleliu and various objectives in the Philippines, preparing for the invasion of the Palaus (15-20 September 1944). She also raided Formosa and the Pescadores. She covered the landings on Leyte and took part in the battle of Leyet (Operation Sho-Go) on 24 October, her air group being fully comitted in the action of the Sibuyan Sea. She also was in the massive strike against the Japanese Center Force, in San Bernardino Strait. She also took part in the Battle off Cape Engaño, her planes notably co-claimed the destruction of the carriers IJN Zuihō and Zuikaku. By November 1944, she covered the proper invasion of the Philippines, roaming the Manila Bay area. CVG-44 notably targetes reinforcement convoys and airfields on Luzon, they also sunk many ships and destroyed installation around Cape Engaño. On 1 December she departed for a resplenishment at Ulithi.

In January 1945, USS Langley was part of the sweep in the South China Sea and also covered the invasion of Lingayen Gulf. She raided Formosa, French Indochina and the China coast at large until 25 January 1945. She also fended off two dive bombers on 21 January 1945, one dropping its 50 kg (110 lb) bomb which ended straight through the carrier’s deck forward, going down to the gallery deck and explode among officers quarters (fortunately not in it at the time). The fire was extinguished, and the flight deck repaired the following hours. She participated in raids afterwards on Tokyo and Nansei Shoto, to prepare for the main operation on Iwo Jima in February-March 1945. After striking the Japanese home islands she attacked Okinawa on 23 March. Until 11 May, she took part in various missions, from clsoe support to CAP, ASW patrols and raids on Kyushu, searching for kamikaze bases in southern Japan. After a stop at Ulithi she was back in Pearl Harbor, steaming to San Francisco (3 June) for prolongated repairs and modernization at Hunters Point NyD. When this was over, the war was also nearly over, on 1 August. On the 8 she was in pear Harbor to learn the end of tjhe hostilities. Soo after she made two “Magic Carpet” runs and made two more trips, this time to Europe. She was in Philadelphia on 6 January 1946, placed in reserve with the Atlantic Reserve Fleet in May 1946 and decommissioned on 11 February 1947.

USS Cabot (CVL 28)

USS Cabot (CVL 28)

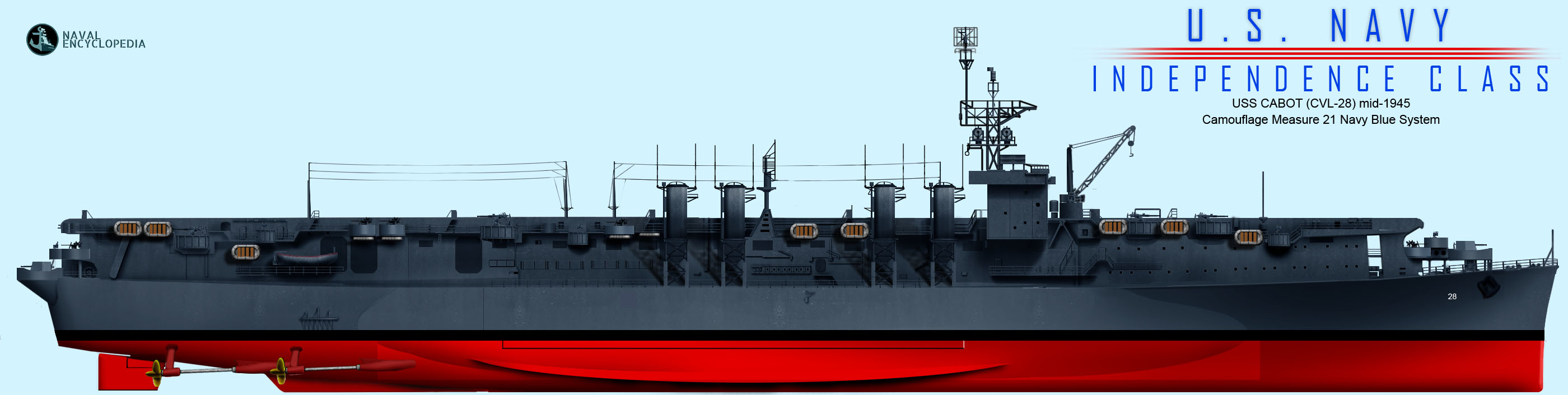

USS Cabot in early 1945, measure 21, navy blue system. Navy Blue 5-N was applied for all Vertical surfaces without exception and Deck Blue 20-B for vertical surface, wooden deck being darkened in Deck Blue, Canvas Covers dyed ideally to Deck Blue. Measure 21 was also applied to Princeton and cowpens in 1943, Langley in 1944, and all ships in 1945 to the exception of USS Cowpens, which used the graded system, measure 22.

USS Cabot underway

USS Cabot trained after commission, off Naval Air Station Quonset Point, Rhode Island, her own Air Group 31. She departed for Pearl on 8 November 1943 and sailed for Majuro on 15 January 1944, assigned to TF 58. On 4 February-4 March 1944, she launched her air group against Roi, Namur, and Truk as part of the Marshalls campaign. Back to Pearl Harbor for maintenance and supply, USS Cabot was back in Majuro, and from there, raided Yap, Ulithi, and Woleai in March 1944. She also provided cover during the attack on Hollandia 22-25 April, and afterwards Truk, Satawan, and Ponape and back to Majuro in June 1944 in preparation for the Mariana Islands campaign 19-20 June. She also had her air group taking a tally during the Battle of the Philippine Sea (“Marianas Turkey Shoot”), and her strik force in air group 31 also attacked Iwo Jima, Pagan, Rota, Guam, Yap and Ulithi until 9 August.

In September 1944 USS Cabot air group attacked Mindanao, Visaya island, Luzon and on 6 October, Air Group 29 relieved 31, her pilots taking a well-deserved break. USS Cabot sailed from Ulithi to raid Okinawa and provided fighter cover and escort during the raids on Formosa, 12-13 October. She assisted the crippled USS Canberra and Houston unti they reached the Carolines, and returned north for strikes on the Visayas, taking eventually part in the Battle of Leyte Gulf, 25-26 October.

USS Cabot made striked afterwards on Luzon, being called for day ground support ashore, also repelling kamikaze attacks. On 25 November, USS Cabot was faced by several waves off kamikazes. One piered through her AA defences and, despite being badly hit, crashed on the port side of her flight deck. This destroyed a 20 mm gun platform and disabling 40 mm Mounts and fire director while shrapnel killed dozens, burning debris spreading fire. That day she lost 62 men, killed or wounded. However her damage control party soon had everything back in order. USS Cabot maintained her station while temporary repairs were made. On 28 November she departed for Ulithi and more permanent repairs. She was back in action on 11 December 1944, attacking Luzon, Formosa, Indochina, Hong Kong, and Nansei Shoto in the great South China Sea raid. By February-March 1945, AG 28 attacked the Japanese homeland and Bonin islands in preparation to the assault on Iwo Jima. She also raided Kyūshū and Okinawa in March 1945 but took part in neither batthe, instead retiring to San Francisco for a long overhault until June 1945.

Her crew trained at Pearl Harbor, and she recovered Air Group 32, launching her final strikes on Wake Island (1 August 1944) underway to Eniwetok. She remained there waiting for fiurther orders, before joining TG 38.3 on 21 August, to cover the landings in the Yellow Sea in September and October 1945. She also repatriated veterans from Guam to San Diego, arriving on 9 November. She steamed to the east coast, decommissioned, in reserve at Philadelphia on 11 February 1947. For the rest of the career see the previous cold war section. She was in effect the last CVL ever in service, seeing the end of the cold war and sole preserved (only for a time unfortunately). During her career she earned nine battle stars and a presidential unit citation.

USS Bataan (CVL 29)

USS Bataan (CVL 29)

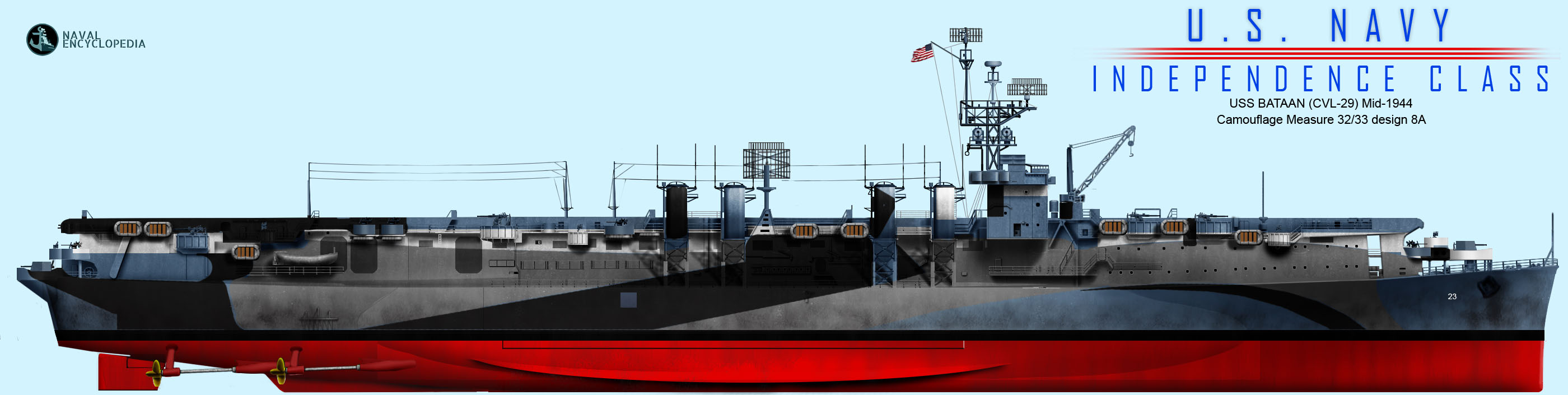

USS Bataan, measure 33 design 8a. The same pattern was used for USS Independence in 1944.

Originally the Cleveland-class USS Buffalo (CL-99), she was renamed Bataan on 2 June 1942 and further reclassified as CVL-29 on 15 July 1943, launched on 1 August 1943, commissioned on 17 November 1943 (Captain V. H. Schaeffer). Her name paid hommage to the Marine of the said battle, which death march survivors were now in POW camps. She made her first trials at Philadelphia Naval Shipyard, fixes, and a preliminary shakedown cruise in Chesapeake Bay, then the West Indies, on 11 January 1944 for her main training cruise. She lost en route a Grumman F6F Hellcat, crashing on her second stack, killing three. She was fixed in Philadelphia on 14 February and moved to the Pacific via the Panama Canal on 8 March. In San Diego on 16t mrch she departed for Hawaii, arriving in Pearl on 22 March and making immediately started pilot qualification drills before deployment. A second aircraft was lost on 31 March, crashing into her landing barrier and going overboard. The pilot was recued. At last, USS Bataan departed on 4 April with escorting destroyers, to the Marshall Islands, Majuro Atoll (9 April) and assigned to Task Force 58. She then sailed with the USS Hornet(ii) Belleau Wood, Cowpens and TG 58.1 for her first operation, against Hollandia in New Guinea.

On 21 April, she launched five fighter sweeps on various points in New Guinea while deploying her Combat Air Patrol, soon claiming a Mitsubishi G4M1 Betty and Mitsubishi Ki-21 Sally. She then headed north to assault Truk Lagoon on 29 April 1944. She deployed her Grumman TBM Avenger on the base, one being shot down, her crew rescured by the submarine USS Tangaffected for this mission during the battle.

USS Bataan underway in January 1952

On 30 April, TG 58.1 sailed to Ponape in the Caroline and in addition to her CAP, the carrier started a Anti-Submarine Patrol (ASP) to protect the battleships shelling the objectives. Then, they went to the Marshall Islands and Kwajalein lagoon, arriving on 4 May 1944 to prepare for the invasion of the Mariana Islands.

USS Bataan moved to Majuro, on 14 May, to repairs her problematic forward elevator but without success. She had to sail to Pearl Harbor and returned to Majuro, on 2 June 1944. She was then prepared for Operation Forager and tasked to hit hard Japanese airfields in the Marianas together in coordination with the 15 fleet carriers of TF 58 which took in turn Saipan, Guam, and other islands. Whe attacking Saipan, USS Bataan was teaming with Hornet(ii), Yorktown(ii), and Belleau Wood, in the reorganized TG 58.1, on 6 June 1944. She also attacked Rota in support and four of her F6F Hellcats in rescue submarine cover patrol shot down three approaching Mitsubishi A6Ms. Another claimed a Nakajima Ki-49 Helen. On 12 June, she coverred the carriers striking Orote airfield, Guam. Her Hellcats shot down a group of incoming Yokosuka D4Y Judy bombers. On 13 June, this was Rota again for her strike groups. The she sailed for the Bonin Islands on 14 June.

TG 58.1 was sent against Iwo Jima and Chichi Jima, destroying both airfields intended to strike the the Marianas, 15 June. USS Bataan planes also spotted and sunk the Tatsutagawa Maru. On 16 June, a large Japanese force was reported and her Task Group was redeployed to face it. During the ensuing Battle of the Philippine Sea, CVL 29 was placed approximately 150 miles (240 km) west of Saipan and Bataan launched on the 19 and CAP and ASP planes while a TBM Avenger shot down a Nakajima A6M2-N Rufe seaplane fighter. For six hours, Bataan’s fighters repelled four major Japanese air raids. Despite of this, 16 torpedo bombers get through but were dealt for by her AA. She dodged torpedoes with ease, one of the advantage of her nimble and agile cruiser hull. In all she claimed 10 Japanese aircraft out of around 300 in the Great Marianas Turkey Shoot. On 20 June, the CAP and ASP routine was back as normal. But the Jpanese retired and one of her Hellcat shot down a lone Betty. She took part in a 206-aircraft strike on the retreating Japanese at dusk. She co-claimed the IJN Hiyō and other damaged, but the landing by darkness was difficult. She lost just one plane however. On 22 June, the chase was called off, back to the Marianas.

On 23 June, Bataan attacked Pagan Island, and the Bonin Islands and the following day, Iwo Jima witht he air groups of Yorktown and Hornet. However her strike group and later her CAP met incoming Japanese aor groups and a battle followed, in which USS Bataan lost three aircraft, claiming 25 in return. The group was in Eniwetok for resplenishment on 27 June 1944 and back in the Bonins on 30 June. New strikes were made on Iwo Jima on 3 and 4 July, Pagan Island on 5 July and Guam 6-11 July. However to fix her forward elevator she sailed back to San Francisco on 30 July for a comprehensive oeverhault, Drydock refit and training, for two months. She also had a second catapult installed as well as a new air-search radar, deck lighting, rocket stowage, and second aircraft landing barrier. Back tp Pearl on 13 October she was assigned to TG 19.5, spending four months preparing for other operations against the Bonin and Ryukyu Islands in early 1945. She notably trained her pilots for night-fighter operations, loosing seven in accidents and in early 1945, five more, including her first Vought F4U Corsairs. Planes were lost, but not the pilots. In pearl she was also given three new 40 mm AA guns and departed for Okinawa.

The Battle of Okinawa started for the USS Bataan on 13 March when she arrived, assigned to Task Unit (TU) 58.2.1, with the USS Franklin, Hancock, San Jacinto, two battleships, two heavy cruisers and destroyers, supporting the last amphibious operation of Okinawa. Her air group notably attacked airfields on Kyushu but also the naval bases at Kure and Kobe while her CAPs dealt with Kamikaze. She saw first hand the damage on USS Franklin. Bataan antiaircraft crews were excellent and splashed two Judys and a Nakajima B6N Jill ina single day but her air group lost four aircraft. On 23-28 March, she struck Kerama Retto and other objectives over Okinawa. Kyushu followed on 29 Marchand support after the 1st April landings of the Marine Corps. Her air group was split between this and striking the southern Kyushu. On 7 April, she took part in the Battle of the East China Sea, hittng hard the approaching Yamato Kamikaze Task Force. Bataan’s pilots claimed four torpedo hits on Yamato, a cruiser and two destroyers. The next 10 days were routine, alternated by replenishments at sea. On 18 April, she sank I-56. On 14 May there was a massive kamikaze attack in which she lost eight crewmen killed, 26 others wounded. Until May her gunners and pilots claimed 12 aircraft for 9 lost.

On 29 May, she sailed for the Philippines, San Pedro Bay, arriving on 1 June. After maintenance and crews’s rest ashore she sailed with TG 38.3 on 1st July to strike the Japanese home islands, deaing with airfields in the Tokyo Bay area on 10 July, shore installations (northern Honshu and as far north as Hokkaido 14-15 July. Her planes co-claimed the IJN Nagato in Yokosuka on 18 July. She attacked Kure on 24 July, damaging IJN Hyūga. Bad weather however precluded more attacks, which resumed on 28 and 30 July (typhoon), until 9 August. She attacked Misawa Air Base (northern Japan) and on 10 August, Aomori, then back to Honshu on 13 August but on the 15 all operations were canceled as surrender terms were discussed. She was present on the 2 September and was in Tokyo bay on 6 Septembe, picking up crew members ashore and sailing to Okinawa to pick 549 Marines, and was bound for home on 10 September, arriving at New York on 17 October.

USS San Jacinto (CVL 30)

USS San Jacinto (CVL 30)

Laid down as USS Newark, CL-100, on 26 October 1942 at NY, Camden, she became CV-30 USS Reprisal on 2 June 1942 and San Jacinto on 30 January 1943, CVL-30, launched on 26 September 1943. She was commissioned on 15 November 1943 under command of Capt. Harold M. Martin. She made a shakedown cruise in the Caribbean and headed for the apcific via panama, then stopping in San Diego and Pearl Harbor, until she sailed to Majuro in the Marshall, assigned to Vice Admiral Marc Mitscher’s TF 58/38, the fast carrier striking force. The embarked the already well trained Air Group 51 and prepared for the Marianas campaign.

USS San Jacinto 22 January 1944

Her air group provided search patrols at Marcus Island, and on 23 May 1944 she participated in the attack on Wake Island, previously pounded by Task Force 14. One TBF Avenger was lost in this mission during an anti-submarine patrol. On 5 June 1944, USS San Jacinto she sortied with Task Force 58 from Majuro and took position on 19 June as the IJN unleashed its last gamble, 400 planes, against the invasion fleet. USS Jacinto’s pilots quickly raised their tally in the famous “Marianas Turkey Shoot”. Her gunners also shoot down ths which get through. Admiral Mitscher sent afterwards his TF in hot pursuit, while night recoverytook place, with some losses. Next, USS San Jacinto attacked Rota and Guam while providing a CAP and ASW patrols. She lost one fighter pilot over Guam, rescued on month later. She made a refueling/replenishment run in Eniwetok Atoll, before going back to the next step, a raid on the Palaus on 15 July. On 5 August she attacked Chichi shima, Haha and Iwo Jima, followed later by Yap, Ulithi, Anguar and Babelthuap, until landings on 15 September.

For the anecdote, future president George H. W. Bush was onboard USS San Jacinto. He was shot down on 2 September on his TBF Grumman Avenger #46214 (VT-51) over the island of Chichi Jima. He was one of the youngest navy pilot in the USN, to join a torpedo bomber squadron, later he was recued and at 20-year-old, received the DFC. Following a new replenishment at Manus, San Jacinto took part in the attacks on Okinawa and sent reconnaissance planes to prepare the future invasion. She took part in strikes against Formosa, and northern Luzon, also patrolling the Manila Bay area in October 1944. On 17 October there was an accident as a had landing fighter plane which trigerred its machine guns, right into the island structure, killing two, injuring 24, including the commanding officer and crippling the radar. While the landings on Leyte took place on 20 October, USS San Jacinto provided cover until on 24 October, the IJN was spotted. Hence started for the CVL her greatest test so far: The battle of the Philippines.

He air group was dispatched first to the Sibuyan Sea, and after refuelling took off to attack the northern force, off Cape Engaño. On 30 October she shot down two approaching kamikaze. She refuelled at Ulithi, and joined attacks on the Manila Bay area, interrupted by an air group swap at Guam (Air Group 45). She was also damaged during a typhoon in December 1944.

Repaired in a floating drydock at Ulithi, USS San Jacinto with the TF entered the South China Sea. Attacks followed on Formosa, Cam Ranh Bay in French Indochina, and Hong Kong. After a new refueling/replenishment, TF 38 prepared the invasion of Luzon by rampaging the Ryukyu Islands. USS San Jacinto in fact soon joined the first carrier strikes directly against the home islands. The first raids took place on 16 and 17 February 1945, her CAP shooting down many approaching kamikaze. First dogfights also developed over airfields in the Tokyo area. This was to prepare notably for the invasion of Iwo Jima, where she brought support for the Marines. She departed for other raids on Tokyo and Okinawa and sailed to Ulithi.

Kamikaze attacks intensified and she witnessed the explosion of USS Franklin. On 19 March 1945, a kamikaze also narrowly missed her. While Operation Iceberg took place, the invasion of Okinawa she provided a vital cover: On 5 April alone more than 500 planes (mostly kamikazes) arrived and between her air group and gunners took a large part in the 300 shot down, the remainder causing havoc on the US fleet. One kamikaze splashed down just 50 feet away from her port bow, but she escaped all damage. The next weeks she would remaine don site and on full alert, providing and support and repelling other air attacks.

On 7 April 1945, USS San Jacinto TBM Avengers claimed the destroyers IJN Hamakaze and Asashimo, sent as kamikaze together with the IJN Yamato. USS San Jacinto’s air group also targeted kamikaze airfields on Kyūshū, and maintained their CAP and ASW patrols. On 5 June 1945, she emerged from another typhoon lightly damaged, and made a replenishment run at Leyte, sailing back yo Task Force 58 for the final raids of the war, her air group raiding Hokkaidō and Honshū in July and then patrolled along the coast of Japan until 15 August 1945, searching for opportunity targets. After the surrender, she started “mercy flights” over Allied POW camps, dropping food and medicine until land parties arrived. She assisted to the surrender signature in Tokyo Bay on 2 September 1945, and returned home, eventually dropping anchor in NAS Alameda, California, on 14 September 1945. She won five battle stars for her service.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870