US Navy 1941-44

US Navy 1941-44USS Atlanta, Juneau, San Diego, San Juan, Oakland, Reno, Flint, Tucson, Juneau (ii), Spokane, Fresno

The USN first AA cruisers (1941)

At the end of the 1930s, the concept of “super destroyer” became trendy, and the US Admiralty also had plans to replace the light cruiser of the Omaha class from the 1920s. The final concept resulted in a lightweight dual-purpose ship armed only with the standard 5-in gun in semi-automated twin turrets. They were primarily escorts, and could perform as flotilla leaders as well, relying on speed to compensate for the lack of firepower and protection. Their tonnage indeed was limited to 6,000 tons according to a definition from the second treaty of London in 1936 related to replacements. Production was planned to be a first batch of four ships, followed by another one later. The war broke out and they were planned as a serie of 11 ships in the 1940 rearmament program.

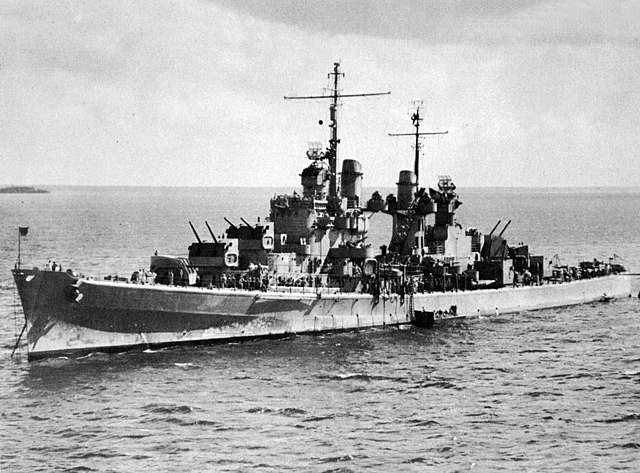

The first four were accepted in emergency in January-February 1942, two lost in the hell of the Salomon Islands (Atlanta and Juneau), and the others gradually in 1943, San Diego, San Juan, Oakland, Reno, Flint, and Tucson taking part in subsequent island hopping operations, escorting fast task forces. The last three (Oakland sub-class) were significantly modified with an open deck and additional AA, sacrificing DP turrets and other wartime lessons brought modifications such as the addition of ballasts, removal of TTs and redesigned superstructures for a greater arc of fire. The last were launched in 1944-46, USS Juneau (ii), Spokane and Fresno, entering service after the war has ended. Tasked mainly of AA protection for Task Forces in the Pacific they were not the best vessels, experiencing machinery issues all along their career, their top speed and agilty suffering from this in return. They proved a little more useful as destroyer leaders, and remained in service between 20 and 25 years. The last in 1973, USS Spokane.

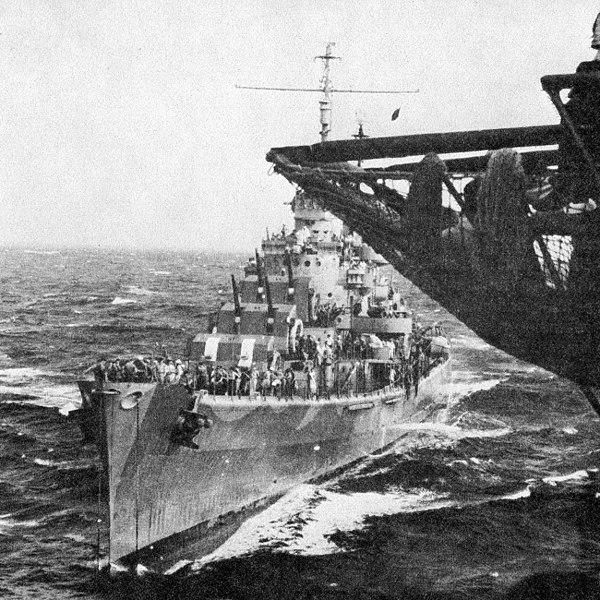

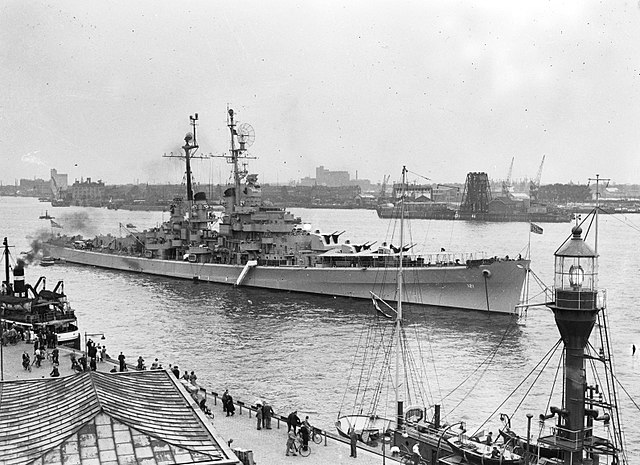

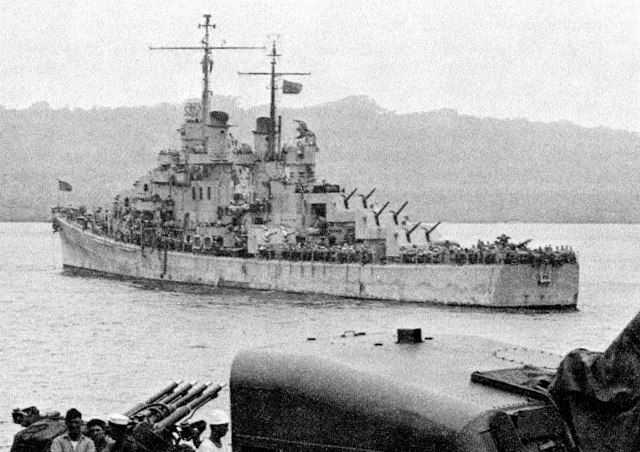

USS Juneau after launch: Forward view and stern

Design development

AA cruiser is a controversial topic for WW2. It was clearly a trend at the very late 1930s, as well as “super-destroyers”. It was realized the threat of aviation was very real and in case of conflict, and that a better AA armament covering protection from high altitude bombers (to some degree), down to low-flying strafing aircraft and torpedo bombers was necessary. Both the US and British Navy explored these designs. The British started first, with the reconversion of their WW1 vintage “E” class cruisers as dedicated AA escorts, and the Dido class (1937). The latter were initially designed as replacement for the earlier Arethusa class, and designed as small trade protection cruisers, but with dual-purpose turrets, smaller caliber, they already constituted an intermediary design. There was probably some influence over the design of the Atlanta class, which also took the same tonnage reference design authorized by the second treaty of London in 1936, 7,500 tonnes. The treaty banned heavy cruisers as a whole. But the Atlanta class had to wait for specific, comparable weapons system to be matured, and this became the ubiquitous 5-in/38 Mark 12 dual purpose twin turret. A legendary weapon that was used from 1934 to 2008.

Work began in December 1936 with the aim of having ten ships in the 5,000-7,000 tons displacement range. Several designs were prepared by BuShips for the admirarty, all armed with a mix of 6in and 5in guns. The Admiralty settled in 1937 on the new dual purpose 6in/47 gun still under development. It would happen this wasn’t really ready until 1945 (the Worcester class adopted it). The massive Cleveland class built after the end of treaty limitations reverted to this solution of mixing 6in and 5in guns. The Atlanta core design was settled on nine 6in and six 5in guns, as desired by the admiralty, but BuShips soon rang the bell of impossibility, within the 8,000 tons limit.

Rendition of USS San Juan in world of warships

Eventually the this discussion ended with the adoption of the new dual purpose 5in gun which development was faster. It was a risky proposition to concentrate a cruiser on basically what was at the time a destroyer main armament. But at the time, the aviation threat inclined towards the choice of long range anti-aircraft gun. Indeed, the USAAF “heavy bomber” lobby was vocal about the capability for them to bomb from high altitude any fleet. The final design of 1938 carried eight twin 5in gun houses, sixteen guns in all, so three times more than an average destroyer. Due to the light weight of these, engineers were able to placed them on superfiring positions on three levels without compromising much the stability.

Six were were mounted on the centreline on three levels, but still, the remainder were placed on the broadside, at first four, then only two, on either side of the rear superstructure. But even with this configuration, these ships proved they had stability issues that were corrected n further development during the war.

Only seven turrets could fire on the broadside, but some papers in the general board file suggests they would have been used to fire star shells. The second batch had its side guns removed and replaced by lighter 40 mm quad Bofors and on the third one, the middle four turrets were dropped to reduce top weight.

USS San Juan amidship, showing its AA position, sloped rear funnel superstructure and boats

The Atlanta were surely the most overrated cruisers of that era, especially in regard of their top speed, expected to be 40 knots, enabling them to hunt down destroyers. On trials, they barely approached 33.27 knots at full power and overheated boilers, and this was only just above their designed speed of 33 knots. Initially, their speed was thought to be an active protection, making armour protection superfluous. In the legal sense, as presented to the Congress, they were replacements for the 1920 Omaha class, and so were suppose to take back their flotilla leader role as well. These small cruisers were meant to work with destroyers on the flanks and vanguard of the battle line. The Atlanta class was authorized in 1939, and ordered in 1940, in March, April, and May. The first hull laid down was of USS San Diego at Bethleem NyD, Quincy. The first launched was USS Atlanta in September 1941, hence the class name.

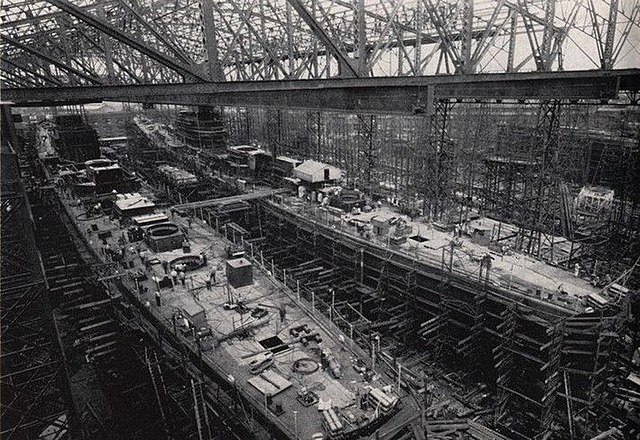

San Diego and San Juan under construction at Fore River Shipyard in early 1941

Their overall design evolved very much in light of an alternative design with twin 6-in/47 as the development of the 5-in/38 took more time than expected. This led to a parallel development, shown in the video game world of warships here as the “Dallas class”. We will have a look on this parallel unbuilt design in a future dedicated post. They were basically designed to fill a niche tonnage: The admiralty had only 17,600 of 143,500 tons left for light cruisers, leading to the 1934 Number 389 design. The fictious “Dallas” was a further development of it in 1940, designed with two hull configurations, A and B. Although it was never built, the Atlanta took back some elements of this.

General overview & construction

The hull was based on a 6700 tonnes standard design, 8300 fully loaded, and slim: With a beam of 16.21 m (53 feet) for a length overall of 165 m (541 feet) it was even below the 1/10 ratio, essentially the same as a destroyer, or of the Omaha class they replaced. This, combined with a three-level artillery and superstructures that needed to tower above these, made for ships that had a high metacentric height, so unstable in rough seas.

The ships were originally designed to house 26 officers and 523 men. This increased later to 35 officers and 638 men in the first batch, first four ships, and 45 officers and 766 men with the second group (Oakland). They were designed as flagships to fit their flotilla leader role, built with additional space for a flag officer and staff, a space was later used instead for additional crew controlling the AA weapons and electronics. As built they had no radars, only fitted during their maintenance or on completion, from the spring of 1942: First they were fitted with the SC-1 and SG search radars, and the FD (Mk 4) radar for fire control. As the war progressed, this was much upgraded, especially for the third group (Juneau ii).

Pilothouse (San Juan 1944)

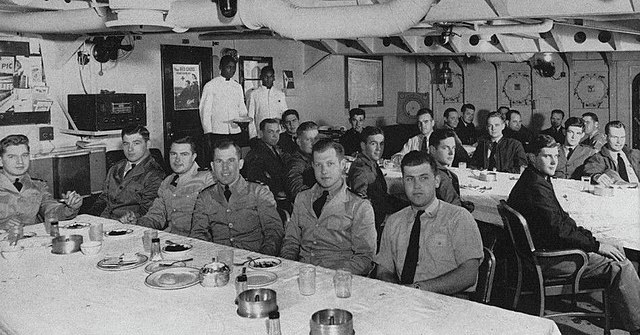

Wardroom Mess (San Juan 1944)

Charthouse (same)

Signalmen (Juneau 1949)

Powerplant

The Atlanta class was designed initially to reach 40 knots, but this needed more space to cram into it a massive powerplant. BoShip proposed a more reasonable configuration with two geared steam turbines (and two propellers), fed by four admiralty boilers working at a pressure of 665 psi (oil fired of course), rated at 75,000 horsepower (56,000 kW). The ships could maintain a top speed of 33.6 knots (62.2 km/h; 38.7 mph) as shown on trials, USS Atlanta reaching at best 33.67 knots (62.36 km/h; 38.75 mph) on 78,985 shp (58,899 kW). No significant changes were made to the powerlant in subsequent batches.

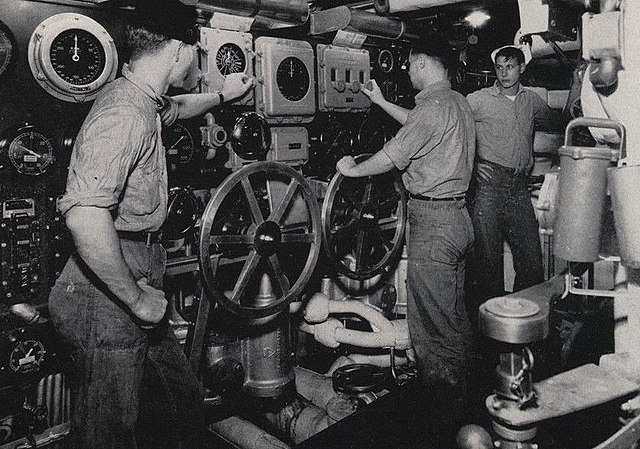

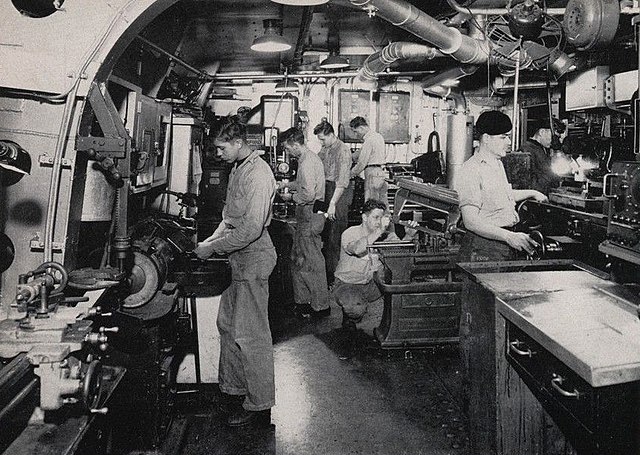

On board USS San Juan, the machine room (top) and Machine shop (bottom)

Armament

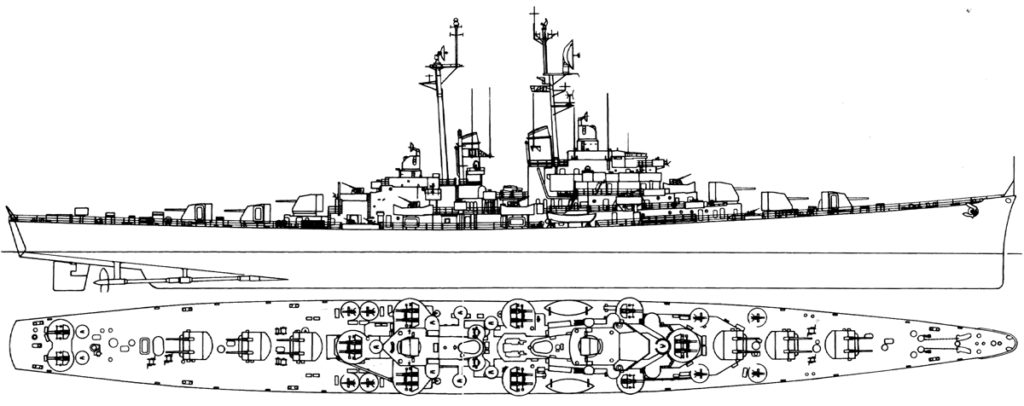

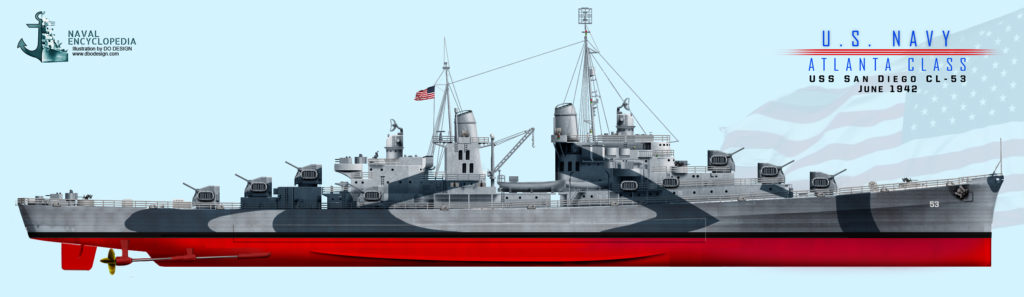

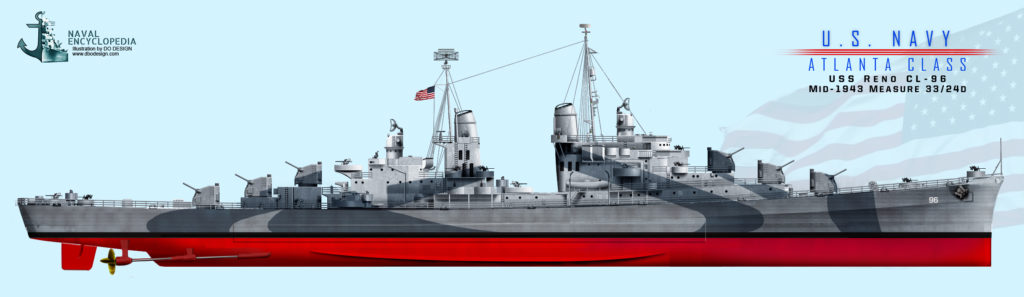

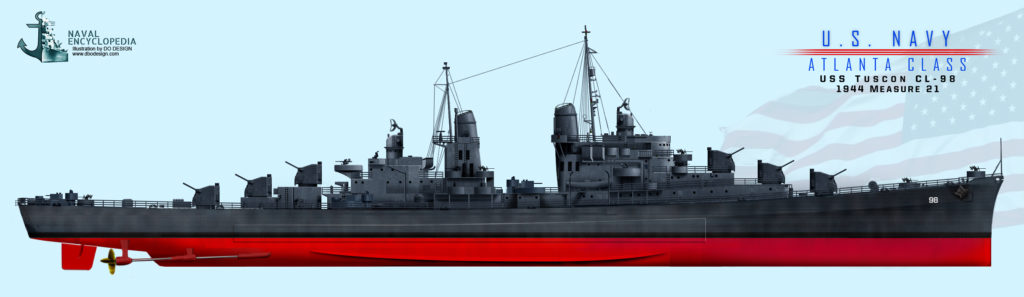

Atlanta class design (CL 51-54)

Main Battery

As built, the Atlanta had a main gun battery composed of eight dual 5-inch/38 caliber gun mounts (127 mm). Altogether, they could fill the sky or rain down on any destroyer 17,600 pounds (8,000 kg) of shells per minute. The most effective AA ammunition was the radar-fuzed “VT” shell. Fire control was managed by two Mk 37 fire control systems, located atop the bridge froward and aft. Despite being completed in 1941, they lacked radar at first, but an FD (Mk 4) model was fitted during the first refits in 1942. From 1943, it was upgraded or fitted for units still under completion, by the improved Mk 12/Mk 22.

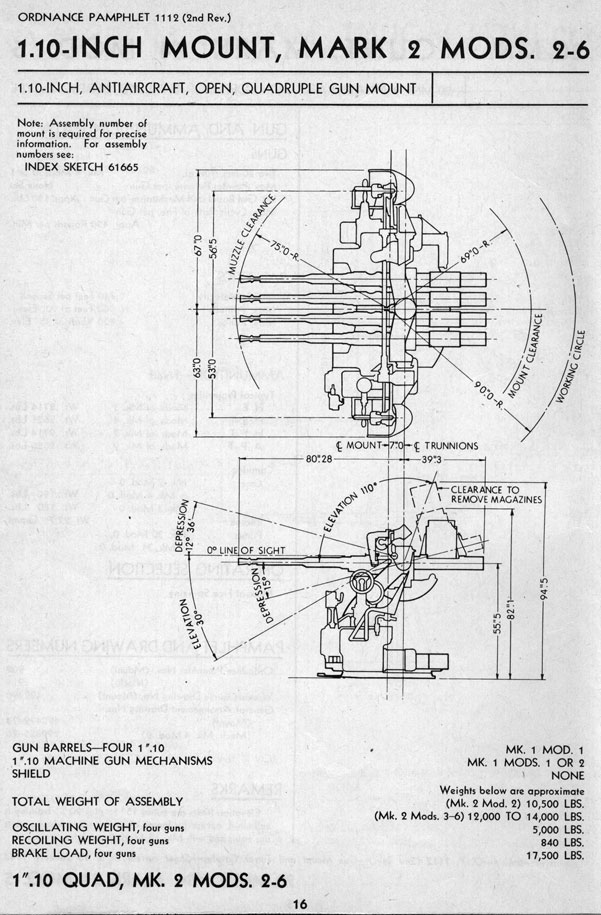

Tech sheet for the 1.1 inches/75 (28 mm) quad AA gun “Chicago Piano” (src navweaps.com)

Secondary Battery

The first four were fitted with a “1940” pattern anti-aircraft armament, twelve 1.1-inch (28 mm)/75 caliber guns in three quad mountings, the infamous “Chicago Pianos”. They were not assisted by fire directors and of dubious value. Fortunately in early 1942 more became available, and a fourth quad mount was installed on the quarterdeck, as well as directors, Mk 44. In late 1942 they were all replaced for good by the trusted Bofors 40 mm anti-aircraft guns with Mk 51 directors, but in twin mountings. It is unclear if they possessed twin or single cal.05 heavy machine guns.

In early 1942, close-range AA was buffered, by the fitting of eight 20 mm Oerlikon AA guns, in single Mk 4 mounts: Two were placed on the forward superstructure, four amidships (between funnels) and two on the quarterdeck aft. In 1943 two more were added on the forward superstructure and another two abaft the second funnel. By the end of 1943, a quadruple 40 mm Bofors replaced the quarterdeck twin mount. To combat weight increase, the ships lost their six depth charge projectors. This AA additions were not planned in the initial design and participated in the ships being overcrowded and not very popular as a result.

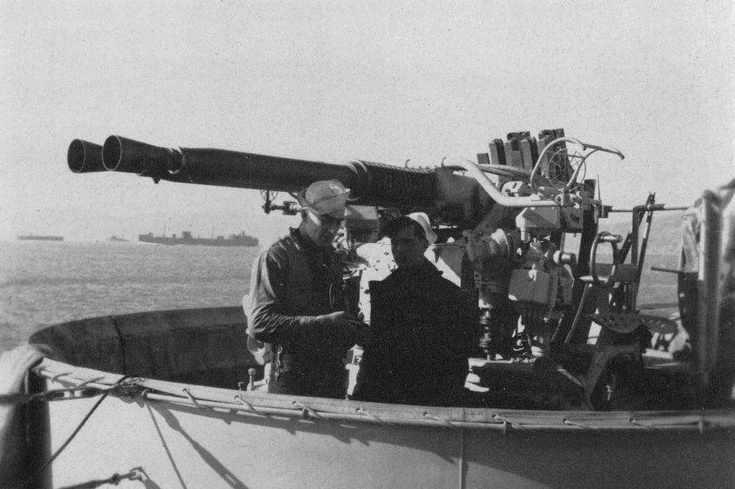

40 mm Bofors on board USS Juneau

Torpedo Tubes and ASW

The Atlanta-class were the sole wartime class of cruisers in the USN to be commissioned with torpedo tubes: Eight 21-inch (533 mm) were fitted on the broadside, in two quad launchers. This capability was a reminder of their flotilla leader primary task. However, no anti-submarine armament was planned, depth charges or sonar. In early 1942, a serie of upgrades saw them fitted with a sonar and standard destroyer battery: Six depth charge projectors on the broadside, plus two tracks at the stern. However later this year and 1943 the admiralty decided they were more valuable for AA defense and projectors were removed. The stern racks were kept however. The later Oakland sub-class never received projectors, only the two stern racks.

Sub-Class Oakland (CL 95-98):

This second group was sometimes called “Oakland class’ by some authors, but most attached them to the larger Atlanta class since their differences were minor. It is not the case with the last batch (Juneau (ii)), heavily modified. The four ships of this batch saw their design revised to combat stability issues: They only had their six axial twin 5-inch/38 mounts. For lighter AA, they also had Bofors from the start, but four additional twin Bofors, in place of the former 5-inch/38 wing turrets, plus two between funnels. So the 20 mm Oerlikon there were replaced on the bow, with the addition of four more on the forward superstructure and eight amidships abaft the aft funnel and quarterdeck. This made for a total of sixteen, twice as many on the previous batch.

By the end of the war, the batch lead vessel, USS Oakland was the first fitted wit the so-called “anti-kamikaze upgrade”: The 4 aft twin Bofors were replaced by quad mountings while the 20 mm Oerlikon were down to just eight or even six, and rather in twin guns while torpedo tubes were removed, all to make room and spare weight.

Protection

Assuredly the weaker part of the design. None of these ships were intended to face off cruisers, only destroyers. For this reason, their protection was layered, sloped, intended to protect them from incoming 5-in (120-130 mm) shells at low trajectories. They had thin armor, maximum of 3.75 inches (95 mm) for the belt, with their immune zone designed to sustain hits from a 5.1 in AP shell at 60° angle on 6,000-16,000 yards. The goal was to limit protection to the the essentials, the machinery and magazines. The 5-inch gunhouses were protected only by 1.25 inches (32 mm), against shrapnel and aviation fire essentially, same thickness for the armoured decks underwater as well. The conning tower had walls 2.5 inches (64 mm) thick.

Bureau of Ships Revised design (1942): Juneau class

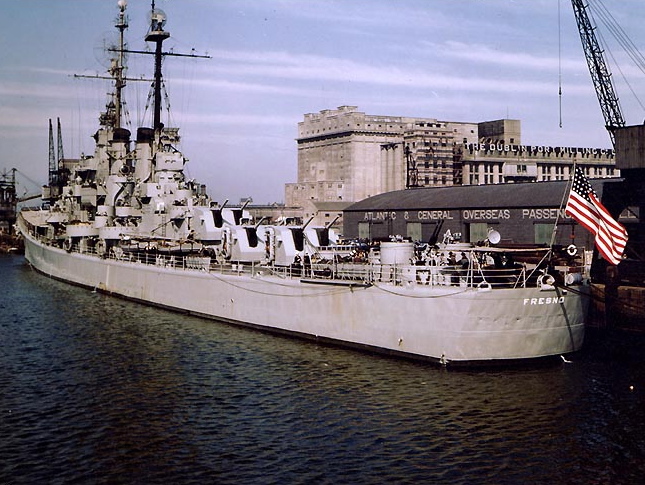

That year, in light of early war experience, the Bureau of Ships proposed to the admiralty a revised design, that would be attributed later to the hull numbers CL119-121 (USS Juneau(ii), Spokane and Fresno. This was a considerable redesign, in light of war experience. Like for the Cleveland and Baltimore, these were upgrades to better distribute the weight overall and combat stability issues, and also give them a better arc of fire. This translated on many changes in the Atlanta class, now called “Juneau” (2), also comprising CL-119, 121 (Spokane) and CL-121 Fresno. The first two were launched before the end of WW2 but they were completed in early 1946, the their in November that year. They served in Korea and NATO fleet for most of their career and were BU in 1961-73, condemned by the missile age.

USS Fresno in Dublin, Ireland, May 1948

The modifications consisted of an overhaul of their twin mount placement, which saw the second pair placed at deck level, and the last superfiring pair, down from one level. This greatly contributed to lower the center of gravity of the ships since this also allowed to lower the whole bridge superstructure and fire directors as well. Watertight integrity was also reworked. A better distribution now allowed to add more light AA, in the shape of four quadruple and six twin 40 mm Bofors, the “Kamikaze upgrade” already seen on the previous batch: In all, 6 quad and six dual 40 mm (1.6 in) Bofors (32 in all) and 8 dual 20 mm (0.79 in) Oerlikon (16 in all). Displacement: 6,718 long tons (6,826 t) standard, 8,340 long tons (8,470 t) fully loaded, dimensions unchanged, crew: 623, and the latest FCS and radar upgraded.

In the cold war, at the time of their service in Korea, they had been modernized with new radars and FCS, and their light AA battery entirely replaced by seven twin 3 in (76 mm)/50 caliber Mark 22 anti-aircraft guns. These were very high velocity, medium range, radar assisted weapons, better suited to jets. The other ships of the former batches received this upgrade as well.

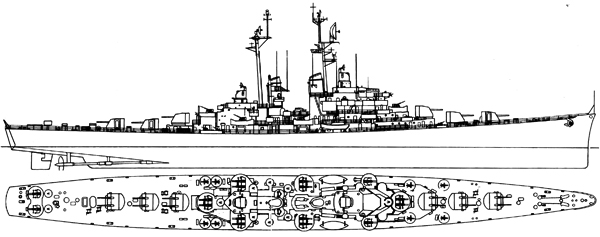

Blueprint of the class. Note: This class will be treated as a standalone.

USS Juneau (CL-119) underway on 1st July 1951

Characteristics (in 1941):

Displacement: 6,718 t. standard -8,340 t. Full Load

Dimensions: 165 m long, 16.21 m wide, 6.25 m draft (541 x 53 x 6.25 in)

Machinery: 2 shaft Westinghouse turbines, 4 B & W boilers, 75,000 hp.

Top speed: 32.5 knots

Armor: Belt & Bulkheads 3.75 in, decks, gunhouses 1.25 in (95, 32 mm)

Armament: 8×2 5in (127mm), 4×4 40 mm AA, 8x 20 mm AA, 2×4 TT 21-in (533 mm), 80 ASW DCs

Crew: 623

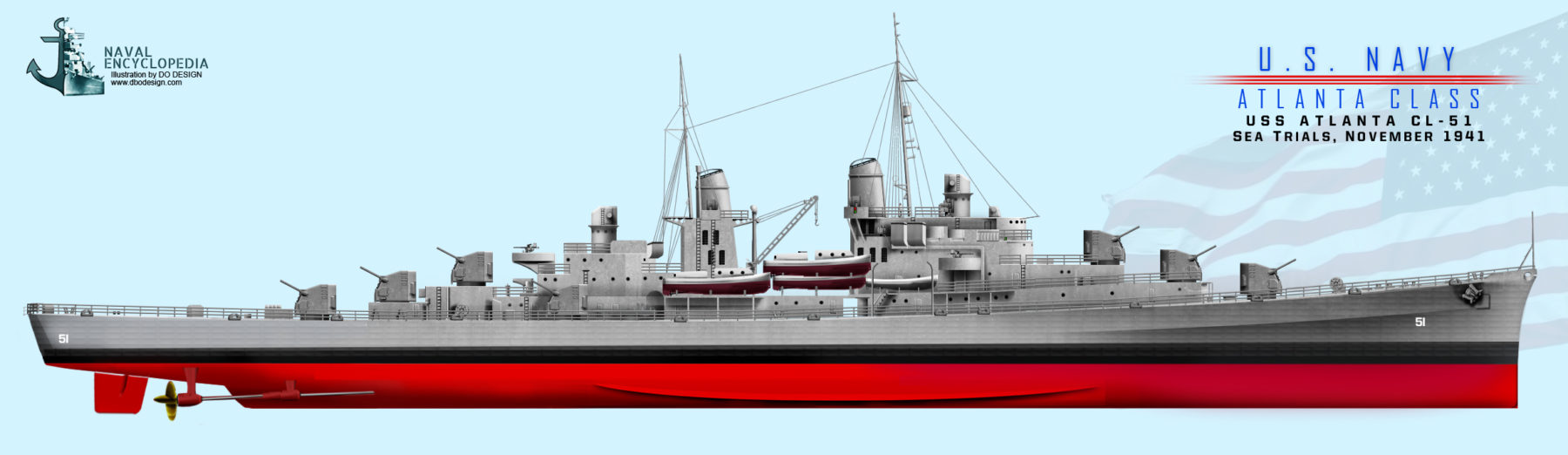

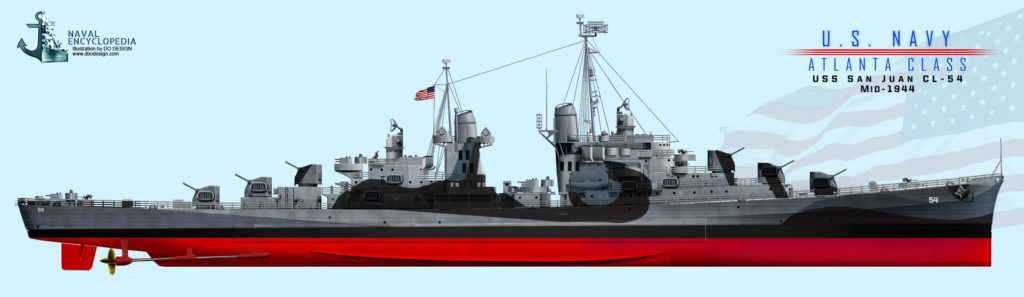

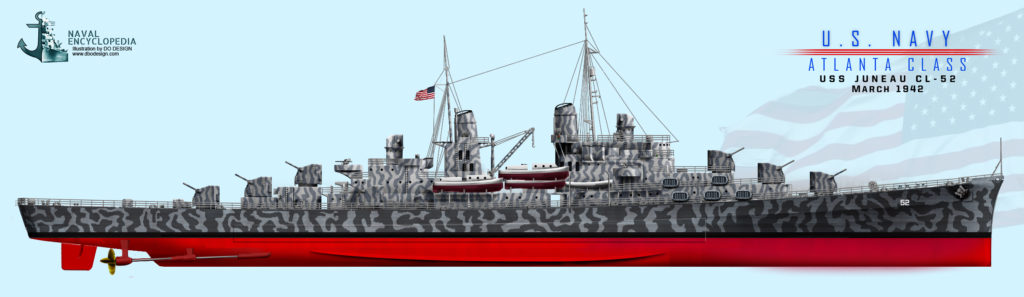

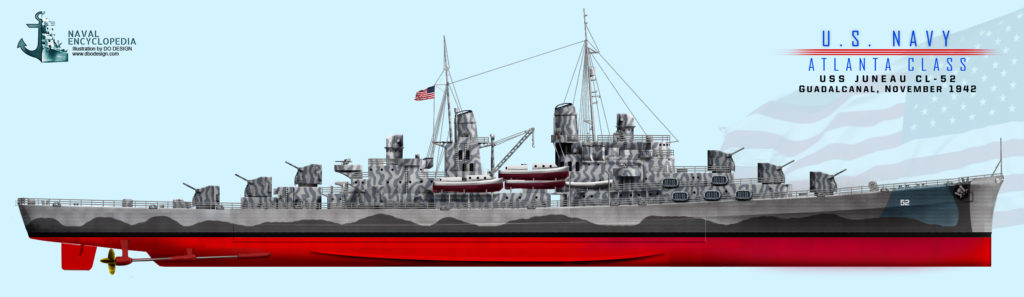

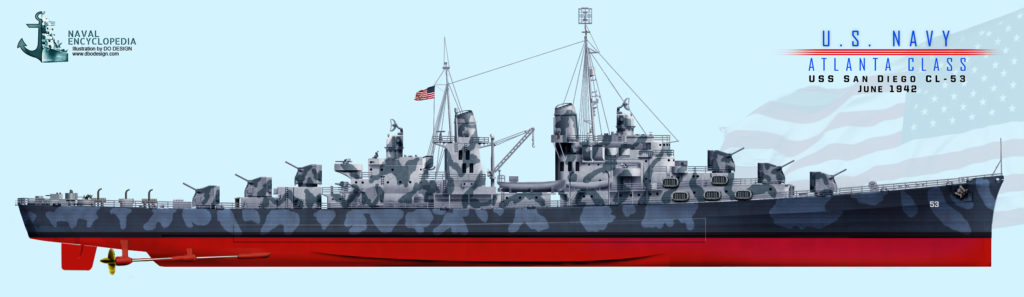

Profiles for modellers

USS Indianapolis as built, before commission

USS San Juan, measure 32/22d (left side), mid-1944

USS Flint, measure 32/22d (right side)

The Atlanta class in action

USS Massachusetts, San_Diego and San_Juan at Fore River Shipyard in 1941

The dates given are those of their entry into service, not their launch.

USS Atlanta (1941)

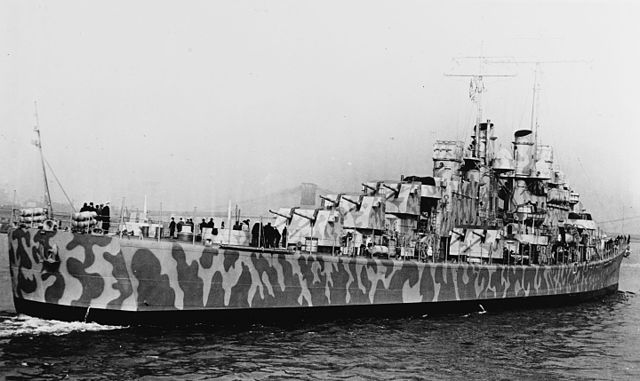

USS Atlanta in speed trials, November 1941, before her commission in December. She was the only ship in the whole class to be so commissioned before the US entered the war.

After fitting out in December 1941 (she was declared completed just before the attack on Pearl Harbor), USS Atlanta started her shakedown cruise, lating until 13 March 1942 in Chesapeake Bay and Casco Bay (Maine), heading afterwards to New York NyD for post-shakedown fixes. Declared “ready for distant service” on 31 March 1942, USS Atlanta departed New York for Panama on 5 April, exited through Balboa on 12 April wit her first mission to Clipperton Island and proceeded to Hawaii, searching for IJN presence underway. She was in Pearl on 23 April.

Battle of Midway:

After an antiaircraft practice off Oahu on 3 May 1942, USS Atlanta, teamed with the destroyer USS McCall on 10 May escorting the troopships USS Rainier and Kaskaskia to Nouméa in New Caledonia, and six days later, joined Vice Admiral William F. Halsey’s Task Force 16 (Enterprise and Hornet) back to Pearl Harbor as news arrived of enemy moves towards the Midway Atoll. She sailed with TF 16 on 28 May and screened the carriers northeast of Midway. On the morning of 4 June the cruiser cleared for action, protecting USS Hornet. Japanese planes made two attacks on TF 17, leaving USS Atlanta unscaved. She screened TF 16 until 11 June.

Guadalcanal

She made an antiaircraft practice on 21 and 25–26 June in Pearl and was drydocked on 1–2 July for maintenance until 6 July. She also trained in shore bombardment. On 15 July 1942, USS Atlanta sailed with TF 16 for Tongatapu and stopped at Nukuʻalofa, Tonga on 24 July 1942. She refuelled there from USS Mobilube, and was prepared on 29 July for the invasion of Guadalcanal, reaffected for this to TF 61. Screening the carriers on 7–8 August, USS Atlanta remained there until 9 August, replenishing in between deployments near the Solomons.

USS Atlanta escorting USS Hornet, with USS New orleans in the BG, 6 June 1942

Battle of the Eastern Solomons

Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto sent the Combined Fleet south of Guadalcanal to cover a large reinforcement troop convoy, spotted by USN scout planes on 23 August, proceeding to the northwest at dawn. USS Enterprise and Saratoga launched their planes but failed to make contact. On 24 August, USS Atlanta received enemy contact reports, and screened Enterprise as TF 16 posted itself north-northwestward to be closer to the reported enemy carrier group. She later started to fend off an incoming wave of IJN bombers and fighters from Shōkaku and Zuikaku. TF16 was now ordered to increase speed to 27 knots and about 18 Aichi D3A1 “Val” from north northwest attacked first at 17h10. For 11 minutes, USS Atlanta created a barrage over USS Enterprise, while the carrier was manoeuvring violently.

USS Enterprise took one hit and shrapnel damage from five near hits. Captain Jenkins (USS Atlanta) later reported five IJN planes down, but otherwise she was never targeted herself.

Reporting for duty to TF 11 (TF 61 on 30 August) she operated for a week, whereas I-26 torpedoed USS Saratoga and she screened her as Minneapolis try to tow her to safety. They reached Tongatapu on 6 September and the AA cruiser refuelled and her crew rested.

Back in operations on 13 September she escorted USS Lassen and Hammondsport to Dumbea Bay, Nouméa and later reported to Task Group 66.4, then TF 17 on 23 September, sailing with USS Washington, the DDs Walke and Benham to Tongatapu. On 7 October, she escorted transports to Guadalcanal, until 14 October, and sailed to Espiritu Santo, refuelling, before joined Rear Admiral Willis A. Lee’s TF 64. She was posted in the Segond Channel on 23 October while two days later, a massive Japanese Army offensive took place in Guadalcanal while Admiral Yamamoto sent the Combined Fleet south. Atlanta’s TF 64 team comprised also the cruisers USS San Francisco, and Helena, later engaged in the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands on 26 October. On 27 October, the submarine I-15 attacked TF 64, without success.

On October, USS Atlanta hosted Rear Admiral Norman Scott as flagship of the new TG 64.2. She refuelled from USS Washington and joined four destroyers northwest, for a shelling sweep against Japanese positions on Guadalcanal. On 30 October at Lunga point she embarked Marine liaison officers and steamed west to start bombardment of Point Cruz at 06:29. She was back to to Espiritu Santo on 31 October to refuel.

Naval Battle of Guadalcanal

Still Admiral Scott’s flagship, the light cruiser and her escort of four destroyers escorted the troopships Zeilin, Libra and Betelgeuse to Guadalcanal, screening them in a force called TG 62.4 off Lunga Point, landing their supplies and reinforcements on 12 November. At 09:05, report arrived that nine bombers and 12 fighters were incoming from the northwest. At 09:20, Atlanta ordered the three auxiliaries to proceed in column northwards, with the destroyers circling around them. 15 minutes later, nine “Vals” from Hiyō arrived over Henderson Field, and he AA barrage started right after downing “several” planes as reported later. Zeilin, Libra and Betelgeuse suffered only minor damage and returned to safer waters off Lunga Point. At 10:50, USS Atlanta received another incoming air raid report. 15 minutes later, 27 Mitsubishi G4M “Bettys” navy heavy bombers from Rabaul were sighted over Cape Esperance in a loose “V” formation. But they ignored the ships and proceeded to bomb Henderson Field. On 12 November, USS Atlanta was off Lunga Point, covering landings with TF 67 (Rear Admiral Daniel J. Callaghan). At 13:10, report came of 25 “bogeys” heading for Guadalcanal, and battle stations were ordered.

TG 67.1 was steaming in two groups northwards at 15 knots when at 14:10, 25 “Betty” Bombers arrived, breaking up into two groups over Florida Island. They made a very low attack, at 25 to 50 ft (8 to 15 m). USS Juneau opened fire first at 14:12 followed by USS Atlanta a minute later. She later claimed two “Bettys” after they dropped their torpedoes. One “Betty”, crippled by AA fire, crashed into the after superstructure of USS San Francisco (flagship), the only ship damaged in the attack.

This was only a respite. A Japanese surface force (two battleships, one cruiser and six destroyers) was detected heading south toward Guadalcanal, apparently to shell Henderson Field. Admiral Callaghan was ordered to cover the retiring transports and cargo vessels and TG 67.4 departed Lunga Point at 18:00, steaming eastward through Sealark Channel. At 11:00 Callaghan’s force reversed and headed westward when USS Helena’s radar had a contact at 26,000 yd (13 nmi). Her search radar and gunnery radars would pick up more contacts and while Callaghan’s order for a rapid course change nearly caused a collision between Atlanta and one of the four destroyers. She retook her station ahead of San Francisco when the destroyer IJN Akatsuki shot flares and illuminated USS Atlanta. She immediately trained her guns on the incoming destroyer, opening fire at only 1,600 yd (1,463 m) soon joined by other ships.

USS Atlanta 25 October 1942

Two other Japanese destroyers however also crossed her line, and USS Atlanta engaged both while soon another unidentified assailant from the northeast opened fire. But soon, one torpedo hit the US AA cruiser at her port forward engine room, probably from Inazuma or Ikazuchi. Atlanta lost her power, only her diesels took over for basic electric feed, and her gunfire stopped. Akatsuki sank meanwhile, but Atlanta was hit by about 19 8-inch (203 mm) shells from USS San Francisco, utterly confused in the melee. Most simply passed through without detonating, but their fragments killed many men, including Admiral Scott and members of his staff. Atlanta in turn prepared to return fire until proper recoignition was done on both sides. Atlanta’s Captain Jenkins assessed the critical situation. His ship battered and mostly powerless, listing to port with a third of his crew dead or missing. At daylight, she witness American destroyers burning nearby, a crippled USS Portland, and the hull of IJN Yūdachi. USS Atlanta drifted toward the shore east of Cape Esperance and dropped her starboard anchor while her captain reported to USS Portland about her condition. Boats from Guadalcanal came out, to evacuate Atlanta’s most critically wounded men and by mid-morning, only valid men remained onboard. She was taken in tow by USS Bobolink from 09:30 on 13 November, heading toward Lunga Point. The crippled cruiser reached Kukum at 14:00. Jenkins (later awarded a Navy Cross) knew by then his efforts to salvage the ship were fruitless and her received authorization by the Commander of the South Pacific Forces, to act at his own discretion. He would later order to abandon ship while preparation to sink her were made with a demolition charge. This proceeded at 20:15 on 13 November 1942, 3 miles west of Lunga Point. The reck is now under 400 ft (120 m) of water. She was struck on 13 January 1943.

IJN Akatsuki in 1937

Her wreck was rediscovered in 1992 by Robert Ballard using ROVs. But the exploration was marred by strong ocean currents and poor visibility. Another dive was made in 1994, by two Australians, making the first mixed gas scuba diving expedition to Guadalcanal. In 1995 and Denlay and Terrance Tysall mounted other expeditions to survey the site. A last was done in May 2011 (Global Underwater Explorers) leading to a documentary.

USS Juneau (Feb 1942)

After a hurried shakedown cruise due to wartime, along the Atlantic Coast (spring 1942), USS Juneau started Vichy-French blockade patrols in early May, off the French Caribbean. This was notably to prevent any escape of Vichy French ships there, two cruisers and an aircraft carrier. Back to NY NyD she made her post-test cruise alterations before being sent for other patrols between the North Atlantic and Caribbean, until 12 August 1942, escorting convoys along the way. At last she was ordered to the Pacific on 22 August, stopping in the Tonga Islands and New Caledonia, meeting on 10 September Task Force 18 (Rear Admiral Leigh Noyes, USS Wasp). TF 17 (Hornet) later joined in and combined to form TF 61, which primary mission was to ferry aircraft to Guadalcanal. On 15 September, USS Wasp was torpedoed by I-19, and sank while USS Juneau and assisting destroyers rescued 1,910 survivors, brought back to Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides by 16 September. Back to TF 17, USS Juneau covered three actions at Guadalcanal, the Buin-Faisi-Tonolai Raid, Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands and Naval Battle of Guadalcanal (or third battle of Savo).

USS Juneau underway, battle of the Santa Cruz islands, 26 October 1942

Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands, 26 October 1942

On 24 October, Hornet’s task force combined with Enterprise, recreating TF 61 (Rear Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid), which repositioned itself north of the Santa Cruz Islands. An ideal position to intercept any fleet trying to reinforce Guadalcanal. The battle for Henderson Field during the night only alerted to a possible naval attack which started by the morning of 26 October. Both aicraft carrier planes took off after a fleet was spotted, damaging the carriers IJN Zuihō and Shōkaku and the heavy cruiser Chikuma plus two destroyers. However after 10:00, 27 enemy aircraft targeted USS Hornet, valiantly defended by USS Juneau. Her barrage, combined with other ships, downed some 20 attackers. But Hornet was hit several times and so badly damaged she sank as a result the following day. Juneau joined Enterprise’s TF and helped repel later four Japanese air attacks, co-claiming some 18 planes. In the evening, the US forces withdrawn to the southeast. A tactical failure, this battle was a strategic victory in the Solomons.

Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, 8 November 1942

Juneau refuelled in Nouméa, New Caledonia, and then reported for duty at TF 67 (Rear Admiral Richmond K. Turner) escorting reinforcements to Guadalcanal. They were there on 12 November, the AA cruiser taking up her position in the protective screen. The landings proceeded until 14:05 until 30 Japanese aicraft were spotted, and a vigorous barrage started, seemingly effective (Juneau claimed six torpedo bombers). American fighters cripple what remained of this wave, which made no significant damage. Later that day, a large enemy surface force was reported heading for Guadalcanal an at 01:48 on 13 November, Rear Admiral Daniel J. Callaghan’s small landing support was attacked by two battleships, one light cruiser and nine destroyers.

Between pitch black, bad weather and confused communications at almost point-blank range, the ships were intermingled and Atlanta was crippled. USS Juneau on her part took a port torpedo hit, launched by IJN Amatsukaze. She had to withdrew before noon on 13 November, limping out from the harrowing battle scene with USS Helena and San Francisco toward Espiritu Santo. Her machinery was partly flooded she she had only one propeller working, and ws heading at 13 knots about 800 yd (730 m) starboard quarter of USS San Francisco. Her bow was underwater from 12 feet (3.7 m).

USS Juneau in October 1942

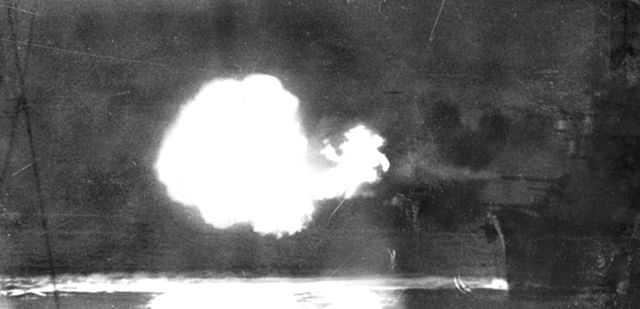

Just after 11:00 however, they were ambushed by I-26. She launched a spread, intended for San Francisco, but two torpedoes passed ahead of her, one striking Juneau behind, on the exact same spot she was already hit during the battle. A great explosion was perhaps caused by the now unprotected magazine being hit, and USS Juneau broke in two, sinking in just 20 seconds, bringing with her most of her crew. Fearing more attacks from I-26 Helena and San Francisco did not attempt to rescue survivors, but it was established later 100 sailors survived, fending for themselves for eight straight days before before spotted by a passing by aircraft.

Sadly all but 10 died from the elements and shark attacks, including the five Sullivan brothers, later honored by the naming of a famous destroyer escort. The event also partly inspired the novel at the origin of Steven Spieleberg’s masterpiece “save soldier ryan” (about the Niland brothers this time). On 20 November 1942 USS Ballard recovered two of the ten survivors. Five more were rescued by a PBY Seaplane. More on the wreck exploration (national geographic) by R/V petrel (Paul G. Allen). The wreck’s position was known.

The five Sullivans brothers, all onboard USS Juneau. They wanted to serve together in spite of USN policy, and became a symbol of US commitment into the war. Destroyers would be named after them.

USS San Diego (1942)

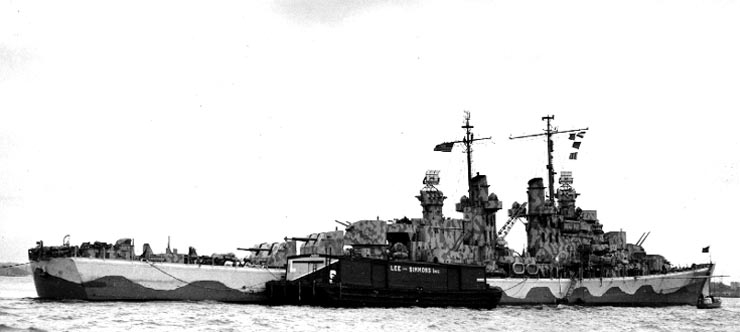

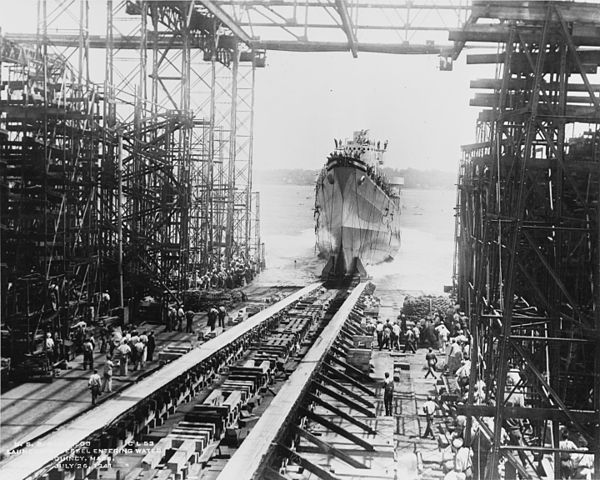

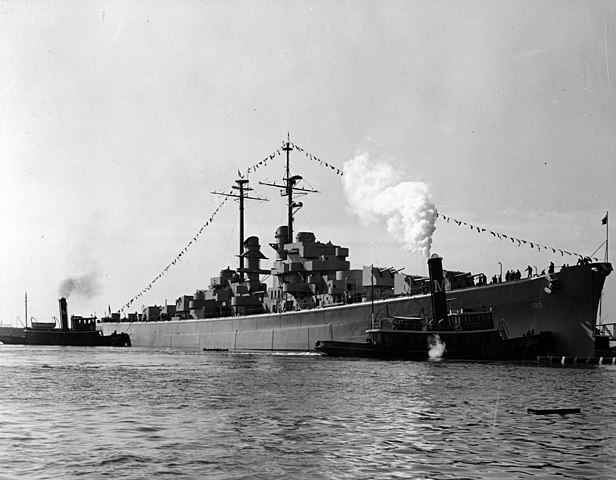

Launch of USS San Diego at Fore River Shipyard, 26 July 1941

USS San Diego made her shakedown training cruise in Chesapeake Bay, and was soon ordered to join the Pacific fleet. She sailed via the Panama Canal, arriving on her namesake city on 16 May 1942, and sailing again, escorting USS Saratoga. But even steaming at her best speed, she narrowly missed the Battle of Midway. On 15 June she escorted USS Hornet in operations and by early August, supported the invasion of the Solomons at Guadalcanal.

USS San Diego off Boston, 10 January 1942

The Battles of the Solomons, June-December 1942

San Diego was present during the battle of Santa CRUZ, finding off attacks but could not prevent the the sinking of USS Wasp on 15 September and USS Hornet on 26 October. She later brought her cover to USS Enterprise and was actively involved in decisive three-day Naval Battle at Guadalcanal in 12–15 November 1942. She survived her sister ships Juneau and Atlanta, and left to Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides and then sailed again for Auckland in New Zealand. Here she was supplied and her crew had a well-deserved rest.

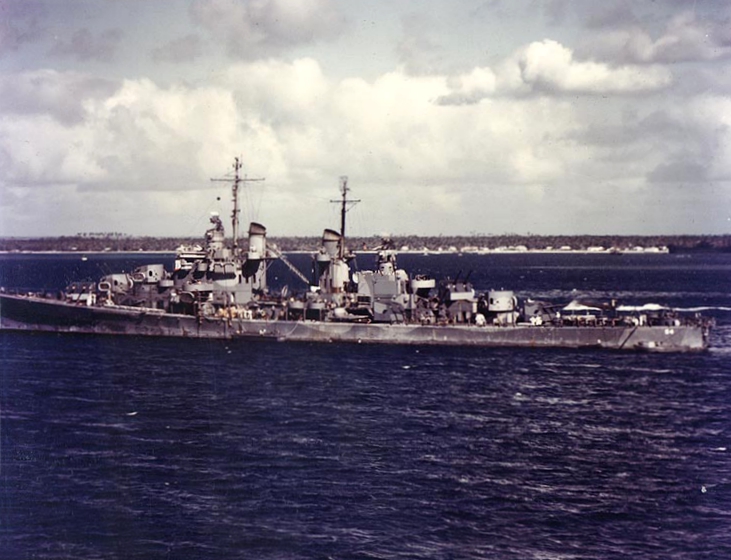

USS San Diego underway, 8 March 1944

The Island hopping campaign, 1943

She later sailed for Noumea in New Caledonia, joined USS Saratoga’s task force, by then the only US aircaft carrier left operative in the South Pacific (Enteprise had been damaged and was under repairs). She joined HMS Victorious for the invasion of Munda in New Georgia and later screen them during the attack on Bougainville. On 5 November, and against on 11 November 1943, she escorted USS Saratoga and Princeton during their raids against Rabaul. USS San Diego also took part in Operation Galvanic, the capture of Tarawa (Gilbert Islands). She escorted USS Lexington after she had been damaged by a torpedo to Pearl Harbor on 9 December. The AA cruiser then proceeded to San Francisco and entered the drydock for maintenance and upgrades. Notably, she saw the installation of modern radar equipment and a brand new Combat Information Center, plus modern 40 mm Bofors guns replace the criticized 1.1 in (27 mm) batteries, which also equipped the now lost Atlanta and Juneau and perhaps in part responsible of their relative lack of effectiveness, fortunately compensated by their excellent 5-in/38.

USS San Diego off Mare Island NyD 10 april 1944

Operations of 1944

By January 1944, USS San Diego joined Vice Admiral Marc Mitscher’s Fast Carrier Task Force*, sticking to it until the remainder of the war. She protected the fast carriers against aerial attack the best she coud, downing many planes in the process. USS San Diego took part in Operation Flintlock (conquest of Majuro and Kwajalein) and Operation Catchpole, the invasion of Eniwetok (Marshall) 31 January-4 March 1944. Task Force 58 attacked Truk, the “Gibraltar of the Pacific.”, again, screened by USS San Diego.

She sailed back to San Francisco afterwards, her radar was upgraded, AA was added and other modifications made. She then reported for duty in the fast carrier force stationed in Majuro. She then proceeded to positions for the attack on Wake and Marcus Islands in June 1944. She saw the attack on Saipan, and raids on the Bonin Islands, as well as the First Battle of the Philippine Sea (19–20 June). She was refuelled and her crew rested at Eniwetok before going back to cover the TF in support of the invasion of Guam, Tinian, and the Palau islands, plus more actions in the Philippines.

USS San Diego, 1st January 1944

On 6-8 August 1944 she gave close support, with on-demand gunnery to Marines at Peleliu. On 21 September 1944, she was in action in the Manila Bay area after a stop to refill at Saipan and Ulithi. She covered TF 38 during the battle on 12–15 October around Formosa. USS San Diego claimed two Japanese aicraft in her sector, driving two ther away, but still, USSS Houston and USS Canberra were badly damaged. USS San Diego covered their escape to Ulithi. She experienced a typhoon on 17–18 December and had some repite before new operations rolling in 1945.

USS San Diego off San Francisco, 14 October 1944

Operations of 1945: Iwo Jima & Okinawa

In January 1945, TF 38 was in the South China Sea, raiding Formosa, Luzon, Indochina, and Japanese forces in southern China, and resplenishe dlater at Ulithi. USS San Diego in February was committed in covering the preparatory raids against Iwo Jima, and on 1st March, she was detached from the carrier force to shell Okino Daijo, to prepare landings on Okinawa. After another refill at Ulithi, she she was back in action around Kyūshū, finding off more kamikaze attacks. She participated in another bombardment, this time during the night of 27–28 March on the island of Minami Daito Jima and on 11 and 16 April fended off more air attacks, claiming a dozen of planes. As suicide attacks increased, she also escorted crippled ships to safety. After another stop at Ulithi, she she covered the proper invasion of Okinawa. She retired to refill again, but was drydocked at the floating dock at Guiuan, Samar in the Philippines.

She was last back in action, this time on the coast of Japan, participating in major raids on naval bases and targets of opportunity by the carrier force, from 10 July until the end of the war. On 27 August, indeed, USS San Diego had the honor to be the first major Allied warship to enter Tokyo Bay. She carried Marines that occupied Yokosuka Naval Base and formal surrender of IJN Nagato. Then it was time for war honors and awards. In all, she covered 300,000 miles (480,000 km) across the Pacific, downing or damaging perhaps a hundred planes. She became one of the most decorated cruiser of her class, due to her early service and survival to Guadalcanal. She entered San Francisco on 14 September 1945, left her crew on leave for some supplies and maintenance, and returned afterwards to serve during “Operation Magic Carpet”, bringing American troops back home.

USS San Diego was eventually decommissioned, Pacific Reserve Fleet, on 4 November 1946. She stayed in Bremerton (Washington), redesignated CLAA-53 in 1949 and in 1959 she was formally struck from the Naval Register and sold in December 1960 to be broken up in Todd Shipyards, Seattle.

USS San Diego in the arsenal of Mare Island, late 1945, showing its armament details

USS San Juan (1942)

USS San Juan, colorized, underway in 1942

After her shakedown training cruise in the Atlantic, USS San Juan sailed to Hampton Roads in Virginia, on 5 June 1942. She joined a carrier task group around USS Wasp and moved to the Pacific while escorting a large group of troopships there, bound for the Solomon Islands. After a rehearsal in the Fiji, USS San Juan brought her gunnery support during the the landings at Tulagi, 7 August 1942. The night of 8–9 August while patrolling the eastern approaches between Tulagi and Guadalcanal (Admiral Norman Scott), gun flashes were spotted. They came from the disastrous Battle of Savo Island. She retired with the empty transports and sailed to Noumea before joining Wasp, operating with the carrier forces between the New Hebrides and Solomons. The Japanese air strike happened on 24 August and San Juan withdrawn to refuelled, being away from the Battle of the Eastern Solomons. San Juan had a damaged a gun mount off Guadalcanal and she was tasked to escort a damaged USS Enterprise for repairs to Pearl Harbor. She arrived there on 10 September 1942.

San Juan at anchor in 1942

On 5 October 1942, USS San Juan stopped on her way to the south pacific at Funafuti (Ellice Islands), delvering a deck load of 20 mm Oerlikon guns to the freshly arrived marines. Then followed a raid through in the Gilberts, and she sank on her way two Japanese patrol vessels on 16 October. She disembarked POWs at Espiritu Santo and eventually joined USS Enterprise on the 23. Three days later she made contact with an enemy carrier forces. The Battle of Santa Cruz Islands followed, and during the last IJN dive-bombing raid, one bomb narrowly missed San Juan’s stern, but the detonation caused flooding in several compartments while her rudder was damaged. She was summarily repaired in Nouméa on 30 October ad then in Sydney drydock for ten days. She then departed Australia to rejoin USS Saratoga at Nadi, Viti Levu Island, in the Fijis, on 24 November.

USS San Juan off Norfolk, 3 June 1942

USS San Juan coming alongside USS wasp in August 1942

1943 Operations:

Until June 1943, USS San Juan was based in New Caledonia and amde frequents sweeps in the Coral Sea with her carrier group or alone, taking part that month in the occupation of New Georgia. Her Task Force later operated in the New Hebrides, stopped in Efate, and and Espiritu Santo and on 1st 1 November, the Saratoga group raided airfields on Bougainville and Rabaul and covered the landing on Bougainville. Later, this Saratoga task group covered the occupation of the Gilbert Islands. San Juan was later detached with USS Essex for a raid on the Kwajalein, finding of attacks especially on 4–5 December. At last she left for a major overhaul at Mare Island arsenal in the USA.

USS San Juan and USS Barker escorting USS Kanawha off Tongatabu, July 1942

1944 Operations:

USS San Juan was back in Saratoga TG off Pearl Harbor by 19 January 1944. First, this force covered the occupation of Eniwetok in February 1944. San Juan was detached to escort Yorktown and Lexington when assaulting the Palau, Yap, and Ulithi islands on 30 March, 1 April and on 7 April, she escorted USS Hornet(2) (CV-12), at Hollandia by April 1944, Truk at the end of the month. The TG Hornet then sailed to the Marshalls, to support the Marianas campaign by early June, with raides on Iwo Jima, Chichi Jima (Bonin Is.), and the landing at Saipan. USS San Juan also participated in the first Battle of the Philippine Sea, in the famous “great turkey shoot”. She refuelled at Eniwetok, and was detached to escort USS Wasp and Franklin’s TF in July 1944 for the reconquest of Gua, and new strikes on Iwo Jima and Chichi Jima and again on Palau and Ulithi. By that time, USS San Francisco sailed home at San Franciscio for her maintenance and overhaul, and was back to Eniwetok on 4 August, this time in Yorktown’s TG after a refresher training between San Diego and Pearl Harbor. She was back in her old Lexington’s TG at Ulithi on 21 November 1944 and by early December, was present in the strikes on Formosa and Luzon and landings on Mindoro. She was sent at the scouting range of Japanese airfields to draw out Japanese aircraft by radio deception but it failed. On 18–19 December she was battered by a typhoon, and spent Xmas in Ulithi for small repairs.

Colorized photo of USS San Juan in Tonga, 25 August 1942

1945 Operations:

This year was also quite active, San Juan covering the landings on Luzon and strikes on Formosa and Okinawa on 3–9 January, while on 10–20 January ports and shipping in the South China Sea in Indochina (Saigon, Cam Ranh Bay) were raided, as well as Hong Kong. Refilled at Ulithi, San Juan joined the USS Hornet TG for air strikes directly on Tokyo during as the landings on Iwo Jima were taking place in February 1945. She was back to Ulithi on 1 March 1945 to prepare for Okinawa, back with USS Hornet on 22 to 30 April, north and east of Nansei Shoto. When she was not in air alert, she shelled shore objectives on demand. On 21 April she was detached to shell Minami Daito Shima, some 180 mi (290 km) from Okinawa. Her TG was responsible in part of the sinking of the Yamato on 7 April. After refuelling at Ulithi, she was sent off Nansei Shoto to attack Japan. Then, the AA cruiser was sent to Leyte Gulf on 13 June for repairs. She later joined USS Bennington (a late Essex class CV), on 1 July 1945, for strikes on the mainland and harbors. She received news of the capitulation while underwat on 15 August and joined the 3rd Fleet entering Sagami Wan (Tokyo Bay).

The crew of San Juan at general quarters

She then carried unit commander Commodore Rodger W. Simpson tasked with Allied PoW in Japan, collecting and caring for them back to the US. On 29 August, she landed parties liberating camps of Omori and Ofuna, plus Shanagawa hospital. Most were transferred to the hospital ships USHS Benevolence and Rescue. San Juan sailed later to Nagoya-Hamamatsu area, Sendai-Kamanishi and dropped anchor on 23 September next to IJN Nagato at Yokosuka. She was back home on 14 November after stopping at Pearl Harbor. In November she was back for operation “Magic Carpet” to Nouméa and Tutuila and was back to San Pedro on 9 January 1946. She later sailed at Bremerton (Washington) for inactivation, on 24 January 1946. She was decommissioned and reserve on 9 November, redesignated CLAA-54 on 28 February 1949 and stricken on 1 March 1959, sold for BU on 31 October 1961.

USS San Juan scoreboard in 1944

USS Oakland (1943)

USS Oakland in San Francisco Bay, 2 August 1942

Entering service in the summer of 1943, USS Oakland, the first of the modified serie of Alanta (2nd batch) made her shakedown and training cruise off San Diego and sailed to Pearl Harbor. She was there on 3 November. So her wartime career was shorter and less “intensive” than earlier ship, as her sisters. She meet an escort force of three heavy cruisers and two destroyers joining Task Group 50.3 (TG 50.3) assembled off Funafuti (Ellice Islands) for Operation Galvanic, the assault of the Gilbert Islands. Air strikes started on 19 November, and USS Oakland had to fend off a wave of Japanese torpedo bombers on the afternoon of the 20th. For her baptism of fire, she claimed two kills and two kill assists. On 26 November, she was deployed northeast of the Marshall Islands, fending off another torpedo plane attacks. On 4 December, however one of these struck USS Lexington and USS Oakland covered her slow withdrawal to Pearl Harbor.

Operations of 1944

On 16 January 1944, she left Hawaii with TG 58.1 and sailed to the Marshall Islands. She covered more air strikes at Maloelap (29 January) and Kwajalein (30th) and the amphibious assault the following day. 1 February. She also shelled IJN positions in Majuro Lagoon on 4 February, dropping anchor until the 12 when TG 58.1 departed to launch another attack on Truk (16–17 February).

Japanese aerial attacks meawnhile were pressing on 21–22 February, hit the Marianas and Oakland’s gunners downed or splashed two and two again before replenishing at Majuro.

TG 58.1 sailed on 7 March to Espiritu Santo, skirted the Solomons, covered the taking of the Emirau Island (New Britain) on the 20 and a week later, the western Carolines. The TG was caught in unrelentles air attacks which USS Oakland fended off with assistance never damaged in the process. This TG also attacked Palau (30 March) Yap (31) Woleai (1st April) before respenishing at Makuro again. In April TG 58.1 attacked Wake Island and Samar, Truk at the end of the month and Satawan in May as well as Ponape. USS Oakland then headed to Kwajalein on 4 May to resplenish making a refresher anti-aircraft training before returning to attack Guam on 11 June and later the Volcano and Bonin Islands on 14 May 1944.

Task Force 58 intercepted West of Marianas a large Japanese surface force, which degenerated into the first Battle of the Philippine Sea and “Turkey Shoot” anhiliating the last well trained air groups of three Japanese carrier divisions. Afterwards, only young inexperienced recruits will face now battle hardened American pilots until the end of the war. When American pilots returned from it after dark, Admiral Mitscher ordered to “Turn on the lights” as USS Oakland’s did with its 36 in (910 mm) searchlights, contrary to usual military procedure. TG 58.1 attacked afterwards Pagan Island on 23 June and Iwo Jima. The TG replenished as Eniwetok and on 30 June assaulted the Bonin Islands, combining an air and sea bombardment against Iwo and Chichi Jima (3–4 July) and took part in the return fight in the Marianas. On 7 July 1944, the carrier groups launched strikes at Guam and Rota and USS Oakland, assisted by USS Helm recovered downed pilots off Guam while also shelling the Orote peninsula on their way. On 4 August in the morning spotting planes discovered a Japanese convoy out of Chichi Jima in the Bonin Islands and an attack group was formed, with UUS Oakland her sister ship USS Santa Fe, and the USS Mobile and Biloxi plus the Destroyer Division 91, detached from the main task group. They raced at 30 knots between, via Yome Jima, falling on the Japanese on 17:30. Destroyers formed ahead of the cruisers and first sank a small oiler and the destroyer Matsu. USS Oakland sank (with assistance) a 7500-ton supply ship and shelled Chichi Jima. She made three runs, pounding the harbor of Funtami Ko, destroying a shore battery and retired on 5 August. In 6–8 September 1944 her task group hit Peleliu (Palau) and raided enemy airfields in the Philippines until 22 September. On 6 October, she resplenished at Ulithi and escorted her TG to the Ryukyu Islands, hitting Okinawa on 10 October 1944 but also Formosa and the Pescadores on 12 October, fending off an air attack.

While they were reployed on 13 October to hit Formosa, a massive IJA strike took place, unleashing full fury at nightfall, and despite a withering barrage, USS Canberra (TG 38.1) was hit by a torpedo and later Houston. Oakland covered their withdrawal into safer waters and a drydock, and return to assist the fleet’s raid on Luzon (17–19 October) and covered the landings on Leyte on the 20 October. After a supply run at Ulithi the 24th, USS Oakland was ordered to join a stopping fleet assembled to face a Japanese squadron heading on Leyte Gulf, but she arrived too late, assisting the carriers launching search and destroy mission to finish off the remainder of the fleet. In November–December 1944, USS Oakland operated with TF 38 during the whole Philippine campaign and cashed a typhoon on 18 December.

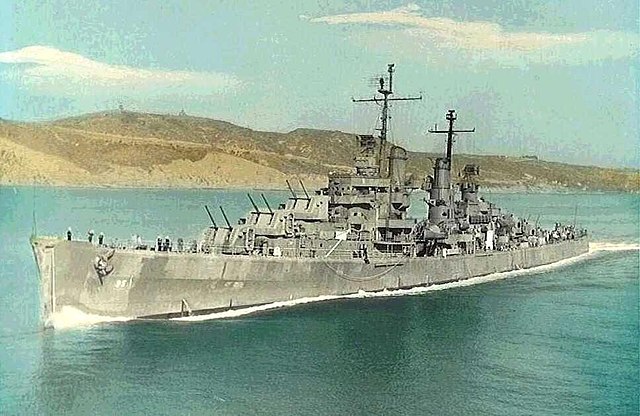

USS Oakland underway in 1945, color photo (cc) src navsource.org

Operations of 1945

USS Oakland was back to San Francisco and a major maintenance and overhaul period from 11 January 1945. She made post-dockyard trial runs and a training refresher cruise to Hawaii, arriving on 4 March, and more training south of Oahu after the 7. On the 14th she was ordered to Ulithi, a staging area for the upcoming campaign against Okinawa. She departed from the atoll on 30 March, and stopped at tap to prepare for the most massive ambitious amphibious of the Pacific war yet. On 2 April she was affected to TG 58.4 and assisted strikes on Sakashima Gunto before Okinawa itself. On 10 April, she was reaffected to TG 58.3 and repelled a first masive air attack on 11 April, claiming a dive bomber. She then moved northward on 15 April, covering aistraikes on the airfields at Kyūshū. There were two new air strikes in which the AA cruiser claimed a “Frances” bomber, and driving off another one. Another massive raid was done on the 17 and Kamikazes evaded combat air patrols. Oakland downed one that day and another the 29th. TG 58.3 was under unrelentless attacks for 11 days in April 1945, until there was nothing left to attack the American armada, which went on striking Okinawa. USS Oakland then detached to a quieter sector to practice AA gunnery with drones and towed sleeves on 11 May. They downed two kamikazes that day, attacking and ultimately sinking USS Bunker Hill, just 2,000 yd from the cruiser. The task force proceeded on Kyūshū on 13 May and the following day, USS Oakland’s guns were blazing on a horde of Zeros, concentrating on USS Enterprise, followed by a wave of kamikazes appeared, Oakland downing four of them and claiming two assists. On the 29th she moved to help TG 38.1 (Halsey) entering Leyte Gulf, San Pedro Bay, on 1 June 1945. On 10 July, TG 38.1 started attacks on Honshū and Hokkaidō. In 17–20 July, Tokyo was hit, on 24–27 July Kure and Kobe. On 7 August, the force turned to attack Honshū-Hokkaido and on the 15th ceasefire was declared.

Postwar service

USS Oakland now assisted the occupation of Japan, starting in Tokyo Bay on 30 August, and Yokosuka Naval Base, close to USS Missouri. She stayed until the night of 27 September, when struck by a typhoon, tanker dragged anchor, stricking her bow and causing some damage. She took part to Operation “magic carpet” back and forth from San Francisco before inactivation in Bremerton, and an overhault at Puget Sound Navy Yard.

On 6 January 1947, she made a post-war cruise to the Far East, stopping at Pearl Harbor and making a two-month fleet exercise in the Marianas and Marshall. She also visited Guam, Saipan and Kwajalein. She proceeded east to China, as American forces there supported Nationalist Chinese against communist Chinese. She was at Tsing-tao on 30 March, flagship of Capt. Sherman R. Clark, at the head of Destroyer Flotilla Three. She also operated off Shanghai for three months, making a dozen patrols in the East China Sea. In May communist forces started to attack the U.S. consulate at Peking and all forces were placed in high alert. USS Oakland landed armed sailors to help Marines embattled in Tsing-tao. Tensions eased in June and USS Oakland left on 20 July 1947, after making a stop at Yokosuka and Pearl Harbor. On 18 March she became CLAA-95 and was decommissioned on 1 July 1949 at San Francisco. She was struck on 1 March 1959 and sold to Louis Simons, 1st December, for scrapping.

USS Reno (1943)

USS Reno underway off California, 25 January 1944

Second ships of the 2nd batch, USS Reno made her shakedown cruise off the coast of San Diego and departed from San Francisco on 14 April 1944 to meet the 5th Fleet (Admiral Raymond A. Spruance), later affected to Vice Admiral Marc Mitscher’s Fast Carrier Task Force (TF 58). Her first test of battle was around Marcus Island on 19–20 May 1944 and three days later, Wake Island. In June to July 1944, she assisted her TF against Saipan (11 June) Pagan Island (12–13) and Volcano Islands, Bonin Islands (Iwo Jima, Haha Jima, Chichi Jima) (15–16 June). On the 19th, she repelled a large IJN carrier task force off the Marianas Islands in what became the Battle of the Philippine Sea. In 20 June-8 July 1944, USS Reno covered the conquest of Saipan, Guam (17–24 July) the Palau Islands (26–29 July). By then, the 5th Fleet was reorganized as the 3rd Fleet and USS Reno participated in operations in the Bonin Islands (4–5 August) and Palau in September. Her Task Force concentrated against Mindanao on 9–13 September 1944 and the landings on Palau islands on 15–20 September, plus air attacks on Manila, Luzon. When closing to Nansei Shoto (8 October), USS Reno and other ships of the TF 38 came closer to Japan itself than any other naval unit so far. Three days of air strikes proceeded. Formosa was hit on 12–14 October 1944, and that day, Reno claimed six enemy aircraft during a counterattack. A torpedo plane however crashed into her fantail, exploding and showering debris which incapacitated her sixth turret for a time.

On 24 October 1944 (invasion of Leyte) TF 38 was hit by a very large air attack from Clark Field in Luzon. USS Princeton was hit by an aerial bomb and nearly written off, she was escorted by Reno while teams tried to contain the fires and men were evacuated. Due to the intense heat and smoke the AA cruiser could do little but stayed at a reasonable distance, until the carrier listed, her flight deck stricking Reno with light damage. When Princeton’s torpedo warhead magazine exploded there was no hope left and the captain ordered to abandon ship while USS Reno was ordered to sink the crippled carrier, one of the rare time any of these cruisers used their TTs. On 25 October she was back with TF 38 sailing to attack the IJN Northern Force leading to the Battle off Cape Engaño, final engagement of the Battle of Leyte.

During the night of 3-4 November 1944 east of the San Bernardino Strait while steaming with Task Group 3 (TG 38.3) (admiral Sherman), USS Reno was ambushed by I-41, wich launched a spray of torpedoes. She took two hits, both on her port side. One failed to detonate and stayed locked into the outer hull (later defused) but the other one exploded four decks below topside, causing 46 dead and more injured. Dead in the water for the remainder of the night she was torpedoed by another Japanese submarine, missing, and the latter was chased off by a destroyer ordered to defend her. She was towed on the morning, for some 1,500 miles (2,400 km) to Ulithi Atoll, being temporarily repaired by USS Zuni. Her starboard torpedo tubes were removed at this occasion to improved a compromised stability.

USS Reno, badly damaged November 1944

The teams pumped out some 1250 tons of seawater from the compartments. For their efforts to save the ship, Gunnery officer Arthur R. Gralla received the Navy and Marine Corps Medal. She started her long trip home, across the Pacific, through the Panama Canal, before entering the drydock in Charleston Navy Yard, on 22 March 1945. This took seven months and the war was over by then. She made post-repair trials on the the Texas coast, training and then making runs for Operation Magic Carpet in 1946, but in the Atlantic, repatriating GIs from Le Havre to NYC. She was decommissioned in Port Angeles (Washington), 4 November 1946, Pacific Reserve Fleet at Bremerton, CLAA-96 on 18 March 1949, and finally stricken on 1 March 1959, sold in 1962 and BU. Due to her state she was not reconducted for cold war operations. Despite her short service she won 3 battle stars during WW2.

USS Flint (Jan 1944)

Launch of USS Flint, 25 Jan. 1944

Flint was commissioned on 31 August 1944. She made her shakedown cruise, followed by a training cruise for the remainder of the year, before reporting to the 3rd Fleet at Ulithi on 27 December. She was affected to Task Force 38 to support the invasion of Luzon. Screening the aircraft carriers she also operated later off Taiwan, China coast in general, fending off a large kamikaze attack on 21 January 1945. After a supply run at Ulithi until 10 February 1945, USS Flint returned to TF 38, covering air strikes on Tokyo and preparatory operations before the landing at Iwo Jima. She was there on 21 February, providing AA cover and some shelling on demand by the Marines, supplying in between to Ulithi on 12-14 March. She assisted operations against Kyūshū befote the final push at Okinawa, claiming several airplanes on 18-22 March.

USS Flint and Shannon and carriers of TF 38 resplenishing between operations at Ulythi atoll, March 1945

As TF38 closed on Okinawa, USS Flint and other cruisers shelled beach installations until the landings started on 1st April. She resupplied at Utilhi in 14–24 May and operated off okinawa until 13 June before withdrawing to Leyte Gulf. On 1 July she left to cover TF 38 in its final air attacks on the Japanese home islands, raods on the east coast of Honshū until the war ended. On 24 August she was ordered off Nii Shima as a rescue ship and homing station for planes carrying occupation troops to Japan. On 10-15 September she was on Tokyo Bay and covered patrols over Central Honshū until 21 September. She travelled to Eniwetok to loaded homeward bound servicemen at Yokosuka (13 October) carrying veterasns bac home via San Francisco (28 November). She made another run, then reported at Puget Sound NyD of Bremerton in January 1946 to be decommissioned. Placed in reserve on 6 May 1947 she was never overhauled and called for service afterwards. She was sold for BU in 1965, awarded four battle stars during her war service.

USS Flint in August 1945

USS Tucson (1945)

Wartime service (1945)

After outfitting and commission at San Francisco on 3 February 1945, USS Tucson, the last of the second batch of the Atlanta class, started her shakedown off San Diego. When it was over she sailed for the western Pacific, on 8 May 1945. She stopped at Pearl Harbor (13th) staying there for three weeks of training and sailed on 2 June, stopping underway at Ulithi on 13-14 June and headed for the Philippines, arriving in Leyte gulf on 16 June. She was assigned to Task Force 38 and more specifically to Task Group 38.3 (TG 38.3) under command of Rear Admiral Gerald F. Bogan, comprising the new aircraft carriers USS Essex, Ticonderoga, Randolph, Monterey, and Bataan. Her wartime service was short. By then, the IJN has been sunk and the IJA eliminated, apart sporadic Kamikaze attacks. She assisted the final operations against the Japanese homeland. On 1st July, she sailed from Leyte Gulf with TF 38 to take position, and on 10 July, was launched the first large scale strike, against Tokyo. On 14–15 July, TF 38 attacked Hokkaidō and northern Honshū, then southern Honshū, Tokyo again and on 24-28 July south of Shikoku, separate groups now tasked to hunt down remaining traffic in the Inland Sea. On 30 July, strikes were made on Kobe and Nagoya. After a refuelling TF 38 was again in operatons for the second week of August, and USS Tucson herself was posted off northern Honshū. She sailed with them when attacking Tokyo again on 13 August, the capitlaton following two days later. She earned just one battle star during the war.

USS Tucson on the way to the scrapyard 1967

Post-war service

USS Tucson remained in the Far East, stationed off Honshū to cover landings of occupation troops in Japan and on 20 September she sailed to Okinawa band proceeded to the United States, stopping at Pearl Harbor and arriving in San Francisco, on 5 October 1945. On the 23th she sailed off San Pedro to participate in the Navy Day celebration (27–28 October) and the following day reported for duty in San Diego. The Pacific Fleet Training Command decided to convert her as an antiaircraft gunnery training ship. Until August 1946 she trained about 5,000 officers and men, particopating in between to various special events on the Pacific coast. On 6 September, shewas drydocked in Puget Sound Naval Shipyard during three month for a major overhaul and modernization as a destroyer leader. She trained out of San Diego for two months, and participated in a large fleet exercise near Hawaii. On 24 February 1947, she was in the defensive team of Hawaii during an attack scenario. She was in Pearl Harbor on 11 March and departed on 18 March to search for survivors from SS Fort Dearborn.

On 27 March, she was back to San Diego, taking part in west coast operations, and sailed again for the pacific on 28 July via Pearl Harbor. She was based in Yokosuka, arrving on 15 August. She cruised the waters of the Yellow Sea and the East China Sea as tensions grew between the Communists and Nationalists. She visited Shanghai twice and Tsingtao, transited by Yokosuka and was back in San Diego on 6 November. After west coast service, until 9 February 1949, when she was prepared for inactivation at Mare Island Naval Shipyard. On 11 June 1949, she was decommissioned, versed to the Pacific Reserve Fleet. She stayed here until 1st June 1966, stricken afterwards. She became a test hulk until 1970, sold on February 1971 for BU. One of her turret’s rotating mount ended in the giant Van de Graaf particle accelerator at the physics department of the University of Arizona in Tucson, Arizona, decommissioned around 2005.

USS Juneau(ii) (1946)

USS Juneau (Cl 119) in 1952

USS Juneau (CL-119) was the first of the second, heavily modified batch. She was laid down in September 1944, launched un July 1945 but construction was halted as the war ended, pending her fate. She was finally completed and commissioned on 15 February 1946, spending this year in operations along the Atlantic seaboard and Caribbean, and was deployed three times in the Mediterranean in 1947. She sailed from New York on 16 April 1947 to join the 6th Fleet at Trieste, arriving on 2 May where she took part in the “trieste crisis”, tensions over ownership of the area between Italy and Yugoslavia. She also made an extended and demonstrative tour of Greece, threatening communists very active in the country in near civil war. She was back to Norfolk on 15 November for training and returned to the 6th Fleet from until 3 October 1948 and until September 1949. She was reclassified CLAA-119 on 18 March 1949 and departed Norfolk on 29 November for the Pacific where tensions rose in Korea.

USS Juneau anchored nearby USS Toledo at Yokosuka in 1950

She arrived at Bremerton on 15 January 1950, served along the Pacific coas became flagship in April 1950 for Rear Admiral J. M. Higgins (Commander Cruiser Division 5) before heading for Yokosuka, arriving on 1st June; She started patrols in the Tsushima Straits and when North Korea invaded the south on 25 June, USS Juneau was available to Vice Admiral C. Turner Joy for operations. She patrolled south of the 38th parallel, preventing enemy landings and made her first shore bombardments, taking place on 29 June at Bokuko Ko. She destroyed shore installations, and on 2 July sank three enemy torpedo boats near Chumonchin Chan. She also covered raiding parties along the coast. On 18 July, her force now bolstered by HMS Belfast, shelled enemy troop concentrations near Yongdok, almost wiping out entire units and nearly stopping the advance. After a halt at Sasebo Harbor to refuel and resupply on 28 July, she made a sweep through the Formosa Straits and joined the 7th Fleet at Buckner Bay in Okinawa on 2 August. Flagship, Formosa Patrol Force on 4 August she served there until 29 October and joined the Fast Carrier Task Force off the east coast of Korea. She later returned to Long Beach on 1 May 1951 for an overhaul of nine months. She received eletronics upgrades with the Mk 37, 56 and 63 fire control systems, and fourteen of the new long range, superfast 3-inch/50cal (in single and twin mounts). She was sent back to the pacific in January 1952 and Hawaii, Yokosuka in April back to the korean war. She condicted strikes along the Korean coast with carrier planes and was back to Long Beach on 5 November 1952. In 1953-54 she made training maneuvers and operations with Atlantic Fleet but also the 6th Fleet, alternating the Atlantic and Caribbean, and Mediterranean fleet.

Back to the East Coast on 23 February 1955, she was placed in reserve at Philadelphia NyD, on 23 March 1955. She was fomally decommissioned on 23 July, attached to the Philadelphia Group of the Atlantic Reserve Fleet until November 1959, and stricken, sold in 1962. Her active career had only spanned nine years, but her concept was no longer relevant in the jet age. She also was too small to be converted, and in a general way, still relatively unstable and weakly built. Her sister ships did not fare better. However at least she was awarded a battle star for her service in Korea.

USS Spokane (1946)

USS Spokane after launch, 22 September 1945

USS Spokane was laid down like her sister ships of the third batch at Federal, Kearny, on 15 November 1944. Launched on 22 September 1945 as the war has ended, she was completed nevertheless in May 1946. She made her shakedown cruise between Bayonne in New Jersey, Brooklyn in New York and in June 1946, Guantánamo Bay in Cuba. She also trained for battle practice and gunners training on drones and towed targets. Back to New York on 11 September 1946 she was assigned to the 2nd Fleet, European waters, arriving in Plymouth on 7 October. She started a goodwill tour in January 1947, visiting Scotland, Ireland, Norway, and Denmark. She headed back home via Portugal, Gibraltar and Guantánamo Bay, taking part in 1947 fleet exercises. She was in Nofolk in March, taking part in more exercises in the Chesapeake Bay, and stopped for maintenance at the Brooklyn Navy Yard in September-October. Back to Norfolk she took part in Navy Day celebrations on 27 October, and was prepared for a long deployment abroad.

USS Spokane in Rotterdam, 1947 and 1950

USS Spokane sailed off Norfolk on 29 October to join the 2nd Task Fleet for tactical exercises off Bermuda until 8 November and proceedd afterwards to Plymouth. She served with the Naval Forces, Eastern Atlantic and Mediterranean. She was present during the crowning celebrations of Princess Elizabeth II and later visited Bremerhaven in Germany by 24–26 November, back to Plymouth for more tactical operations in the north atlantic, and stopped in February 1948 in Rotterdam, visited by Prince Bernhard on 17 February 1948. On 1st March, she sailed for Norfolk. By 18 March she became CLAA-120 and resumed service on the eastern seaboard, until an ovehaul and modernization at the New York Navy Yard (May-September 1948). On 4 January 1949, she was sent in the Mediterranean. In January 1949, she was visited in Athens by King Paul and Queen Fredrika of Greece. She participated in war games with the 6th Fleet and visited Turkey, Italy, France, Sardinia, Tunisia, Libya, and Algeria, and back to Norfolk on 23 May 1949. She became a training ship for Naval Reserves, 4th Naval District and taking part in some exercizes in the Virginia Capes area. On 24 October 1949, she was inactivated in New York, placed in reserve and then decommissioned on 27 February 1950. On 1 April 1966, she became AG-191 but striken on 15 April 1972 and sold for BU in May 1973.

USS Fresno (1946)

USS Fresno off Portland UK, Dorset, 14 August 1947

USS Fresno (CL-121) was launched on 5 March 1946 at Federal Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company Kearny in New Jersey. She was commissioned on 27 November 1946 (Captain Elliott Bowman Strauss) and after her shakedown cruise in the Atlantic on 13 January-7 May 1947, she also visited the Caribbean, Montevideo, Uruguay, and Rio de Janeiro. On 1st August she sailed from Norfolk in Virginia and then heded to Europe, visiting ports of northern Europe and the Mediterranean. Back in December 1947 in Norfolk, she was deployed again in Europe on 3 March until 19 June 1948, stopping at Amsterdam, Dublin, Bergen, and Copenhagen, and being based in Plymouth UK. She was reclassified meanwhile CLAA-121 on 18 March 1949. She notably cruised to Prince Edward Island and Bermuda and was finally decommissioned at New York Naval Shipyard, on 17 May 1949. She was berthed at Bayonne, New Jersey in reserve until 1966 and stricken, then sold for scrap on 17 June that year. She did not earned battle awards like USS Juneau(ii) the only one in action in Korea, but instead the less prestigious WW2 Victory Medal and Navy Occupation Medal “EUROPE”. Her active service was only of three years in the US Navy… Again, like her sisters she was no longer relevant in the cold war context.

USS Fresno in Rotterdam, 1947

Read More/Src

Sites

//www.historyofwar.org/articles/weapons_atlanta_class_cruisers.html

//www.navalanalyses.com/2018/02/warships-of-past-uss-juneau-cl-119-anti.html

//www.cmchant.com/the-anti-aircraft-cruiser-the-us-atlanta-class

//www.petemesley.com/lust4rust/83-solomon-islands/wrecks/wreck-details/95-atlanta

//pwencycl.kgbudge.com/A/t/Atlanta_class.htm

//www.world-war.co.uk/US/atlanta_class.php

//en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atlanta-class_cruiser

Return to the USS Atlanta: Defender of Guadalcanal.

US Cruisers List: US Light/Heavy/AntiAircraft Cruisers, Part 2″. Hazegray.org

Entry for 12–13 November: First Naval Battle of Guadalcanal

//www.navsource.org/archives/04/051/04051.htm

//en.wikipedia.org/wiki/5-inch/38-caliber_gun

Books

Conway’s all teh world’s fighting ships 1922-1947

Friedman, Norman (1984), U.S. Cruisers: an illustrated design history, Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press

Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command. Archived

Naval Marine archives – Cruisers role and Mission p55

Bullard, Thomas (1975). “Question 28/75”. XII (4): 357–358.

The Lost Ships of Guadalcanal by Robert Ballard and The Naval Battle of Guadalcanal: Night Action 13 November 1942 by James Grace

The model’s corner

Dragon Models 1/700 USS San Diego (CL-53)

ISW 4119 – USS Atlanta CLAA51 – Resin Model Kit

Pit-Road USS Atlanta CL-51 1:700

USS Juneau CL-119 Scale Shipyard 1:96

USS Atlanta CL-51 Strike Models 1:144

USS Oakland CL-95 Modelik 1:200

USS Juneau CL-52 Blue Water Navy 1:350

More.

Videos

The Atlanta class by Drachinfels

//youtu.be/UHvpQFHXmKw

//youtu.be/FFqIotUYIw4

//youtu.be/EA7euaGKmsU

//youtu.be/cB_OCPfrAGQ

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign

Wonderful information.