Germany (1914): SMS Pillau, Elbing

Germany (1914): SMS Pillau, ElbingWW1 German Cruisers

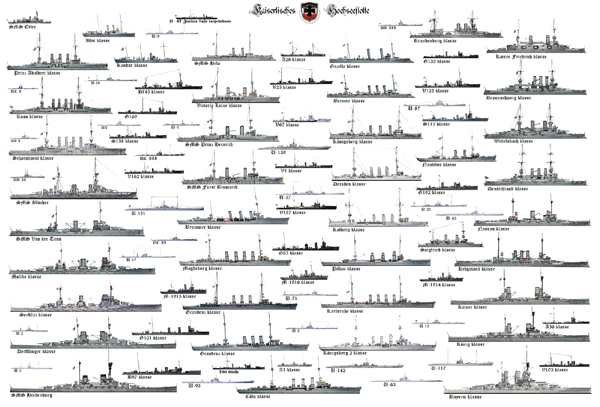

Irene class | SMS Gefion | SMS Hela | SMS Kaiserin Augusta | Victoria Louise class | Prinz Adalbert class | SMS Prinz Heinrich | SMS Fürst Bismarck | Roon class | Scharnhorst class | SMS BlücherBussard class | Gazelle class | Bremen class | Kolberg class | Königsberg class | Nautilus class | Magdeburg class | Dresden class | Graudenz class | Karlsruhe class | Pillau class | Wiesbaden class | Karlsruhe class | Brummer class | Königsberg ii class | Cöln class

From Russia, with Love

The Pillau class were originally the Russian-ordered Maraviev Amurskyy and Admiral Nevelskoy, in 1912 to Schichau Yards. They were laid down in 1913 and launched for the first on 11 April 1914. Therefore on 5 August, both were requisitioned and completed as SMS Pillau and Elbing. They were a bit singular in their style, and their career as well. The first Took part in the battle of Riga, Jutland, Heligoland Bight (2), and became the Italian Bari after the war, modernized and sunk in Livorno by the RAF in June 1943. Elbing on her side took part in the Yarmouth raid, but was lost during the battle of Jutland, not due to enemy action but when she was rammed by SMS Posen…

Design context and construction

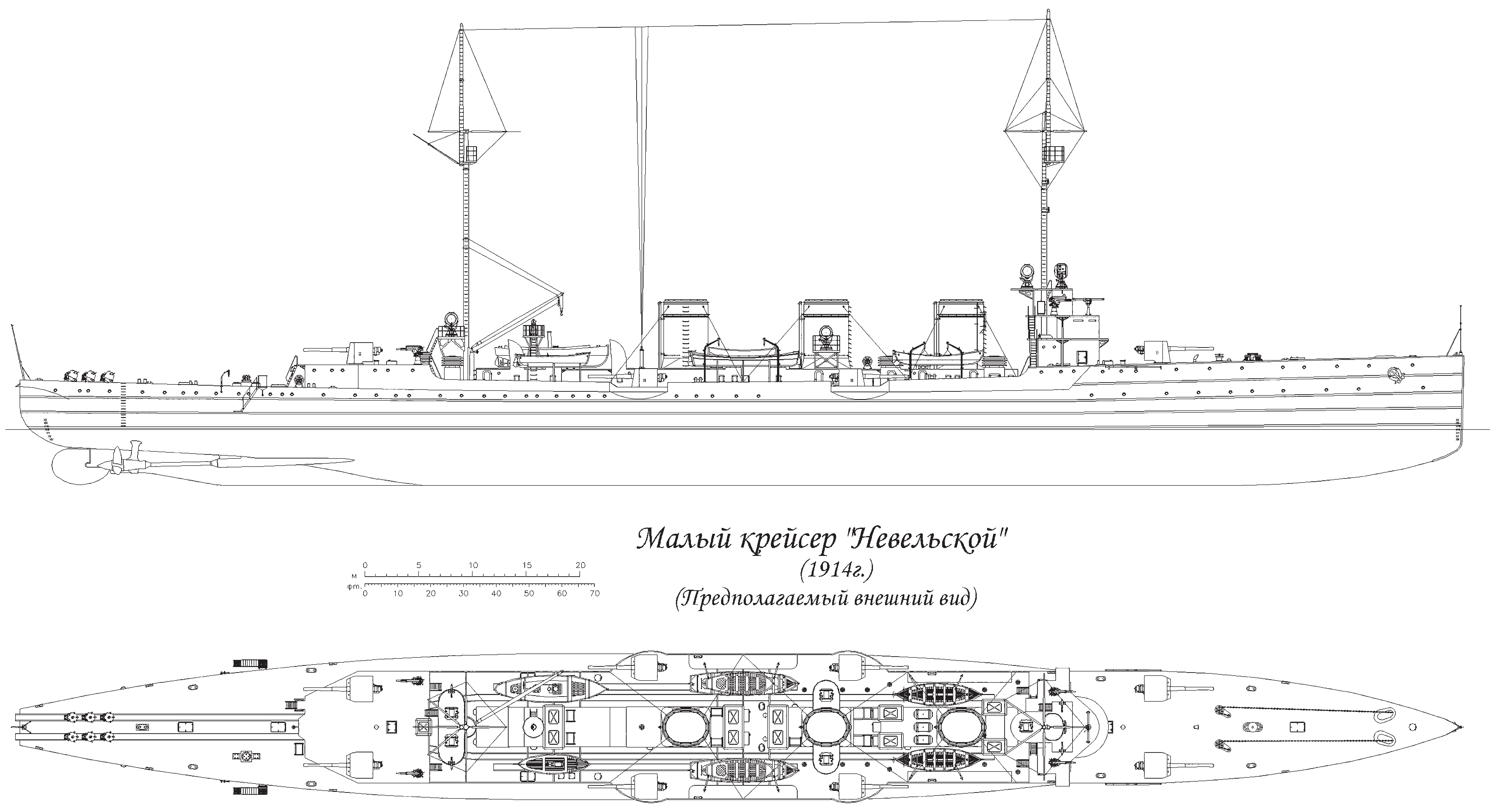

Design of the original Amurskyy class. Notice the conning tower with almost no bridge, three equal funnels, and different armament with the rear ones placed on a superstructure, the side ones on sponsons.

Specifics of the Amurskyy class training/minelaying cruisers

In 1912, the Imperial Russian Navy badly needed new cruiusers fast to rebuilt her crippling losses after the Russo-Japanese war. For memory she lost both her pacific squadron and baltic fleet. Russian yards were alrady busy with some priority construction, in particular dreadnoughts, so the admiralty contacted builders for a pair of light cruisers, and eventually Schichau-Werke, Danzig, won the contract. The Maraviev Amurskyy class were small turbine cruisers planned to acquire as part of a four cruisers procurement, with a design of light cruisers displacing 6800 tons for the Baltic, and 7600 tons for the Black Sea.

There was acute debate about the use of turbine, due to the total lack of training for the crews to service these on new ships. Therefore, the two small cruisers included in the new shipbuilding program were supposed to be turbine training ships. The Naval General Staff considered this task to be prioritary, and also to replace the obsolete Askold and Zhemchug stationed the Far East, now part of the new “Siberian military flotilla”. The third objective was to have them acting optionally as high-speed minelayers, carrying more mines than destroyers, agility and improved maneuverability.

It was planned to reach the agility requirement by a limited length of no more than 130 m and a refined hull shape, although this could adversely impact propulsion. In 1912, the General Directorate of Shipbuilding sent a request for proposals to several yards, Ansaldo, Shichau and Vulkan, pressed to take part in a competition. On the recommendation of the MGSH, two guns were placed on the forecastle, two in casemate bow, two in the aft superstructure and two on the poop.

Experts believed this placement would significantly increase their chase and retreat firepower, and make room for mine rails. Four anti-aircraft guns also were needed to be place as not to interfere with the main artillery still have the best arc of fire possible. Since the displacement was not indicated in the specifications, all projects submitted largely differed on that plan: Putilov submitted a 4,000 tons cruiser, Nevsky 3,800 tons, Revelsky 3,500 tons, Vulkan 4,600 tons and Schichau 4,000 tons. Note that Ansaldo did not even aswered.

As the project was further developed in order to reach agreement to discussions between the MGSH and GUK, the displacement gradually increased while speed decreased and in the end, the Schichau project and its 27.5 knot speed, based on the Kolberg-class cruisers appeared the quickest and most proven of all. But the Naval Ministry was still not satisfied with the traditional German three-shaft configuration, nor their boilers of a type not used in the Russian fleet. It also underlined weak structural basis for the guns and insufficient height above the waterline. Schichau promptly reworked the project and resubmitted it after fixing all issues.

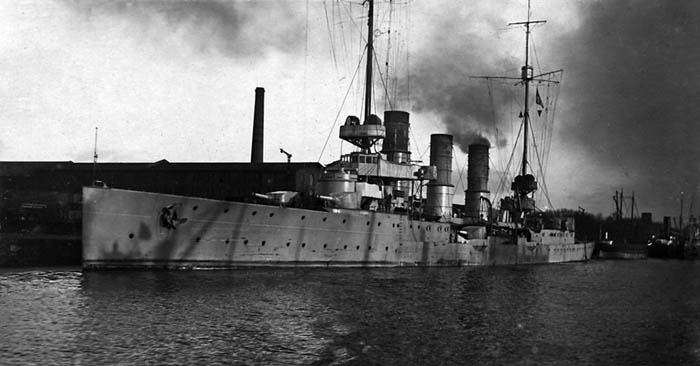

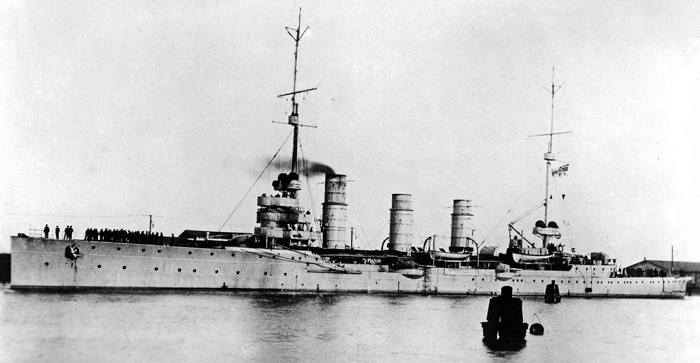

SMS Pillau underway in WW1

Meanwhile, Nevsky Yard was nevertheless recognized as the winner of the competition, but on auction the bidder, fastest construction time were from Schichau, and having considered all applications, the Naval Ministry eventually gave preference to Dantzig Yard, receiving a signed order on July 15, 1914, and a second four months later. Other factories were just not ready to start construction immediately. Putilov shipyard and Revel were already full with orders to manufacturer shells and supplies, while the Nevsky plant could hardly cope with the construction of two destroyers for the Black Sea already.

Giving preference to the Schichau represented a risk however at a time of great turmoil and increasing tensions in the Balkans. Representatives of the General Staff were not even consulted and were faced with a fait accompli, the ministry’s GUK explaining their choice based mostly on the construction time due to a proposal of a slightly modernized SMS Mainz for which plans were drawn already with little modifications. In addition, the yard recommended ten Yarrow boilers (6 coal-burning, 4-oil burning) to feed their own turbines, plus the same propellers as on SMS Karlsruhe.

Both turbines had a capacity of 28,000 liters and the design speed of 27.5 knots (51 km/h) was estimated easy to reach. In January 1913, the named of Muravyov-Amursky and Nevelskoy were reviewed and eventually accepted, for a launch by late 1914, while negotiations were underway between Russia and England for the finalization of the Triple Entente. Of course, by August 1, 1914, war broke out between Germany and Russia leading straight to a requisition and both cruisers changed ownership and later names, on August 6.

Requisition and completion as the Pillau class

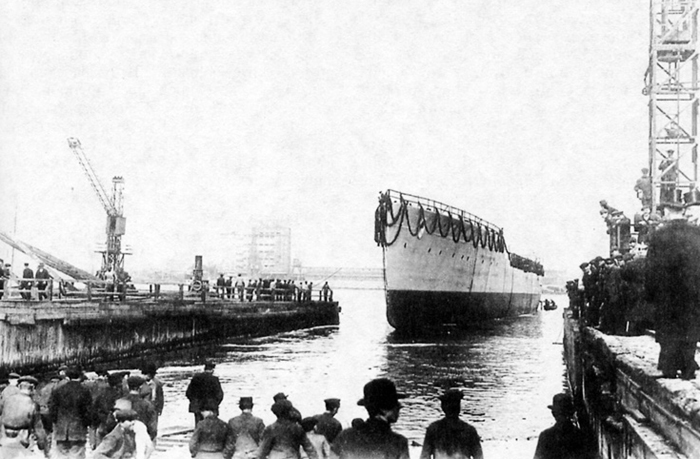

Pillau launch on 11 April 1914

As the war broke out in August 1914, both cruisers were in construction in their basins. The first was launched on 11 April 1914 already and completion was on its way, until stopped by the navy command for standardizattion after the requisition. Plans were changed and modifications made until she was completed and eventually Commissioned 14 December 1914 under the new name of S.M.S Elbing from the baltic port. Her sister ship was launched later, on 21 November 1914 as SMS Elbing. Time was gained since moidifications has been done to her sister so she could be converted and standardized right away. She was commissioned into the High Seas Fleet on 4 September 1915.

Detailed design

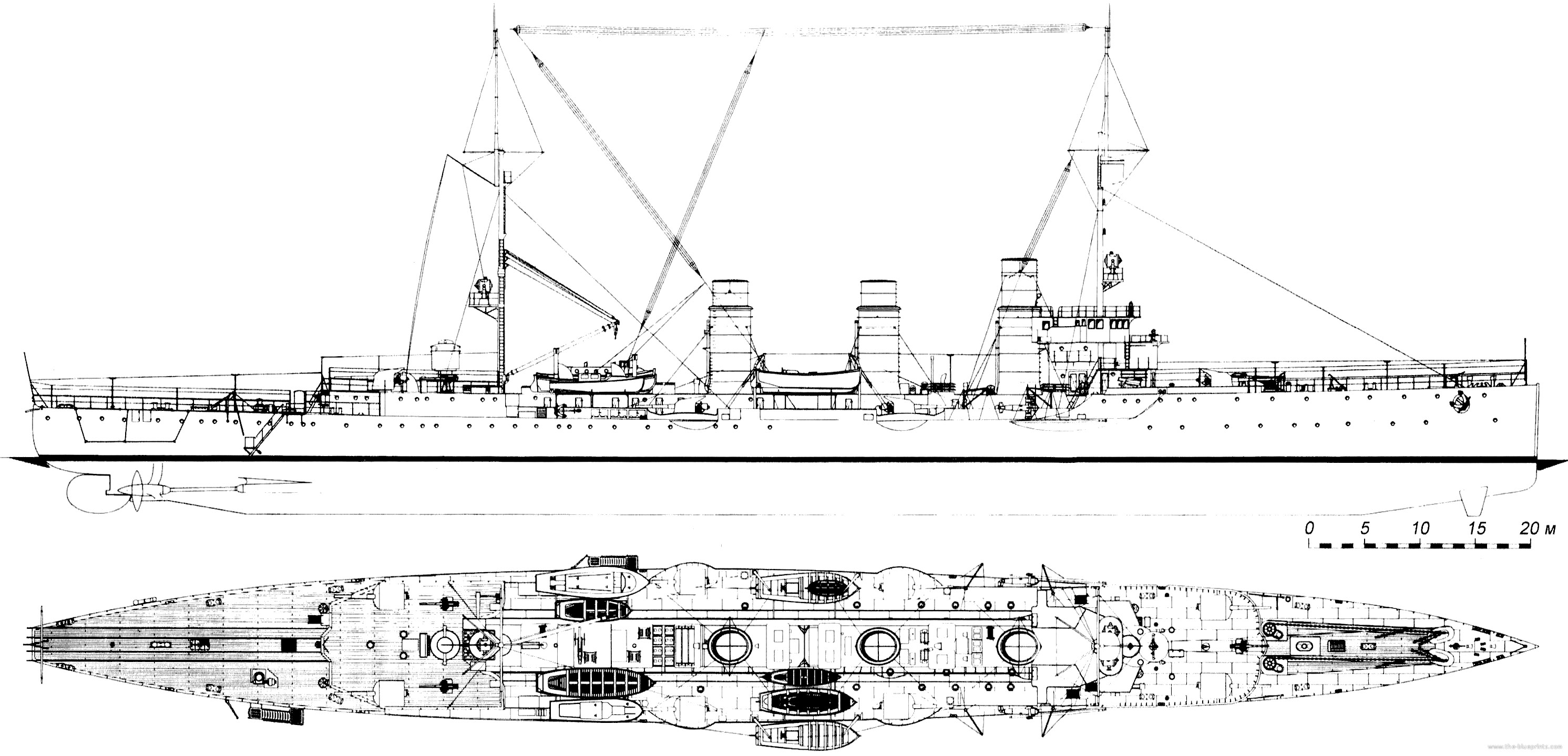

Blueprint of Bari, which presented some significant differences with Pillau

Both vessels had both a family air of German and Russian cruisers strangely. Moslty German, with their three funnels, general forecastle and hull lines, straight prow, and some Russian aspects for the bridge and masts as well as casemates. They were manned by a complement of twenty-one officers, leading 421 ratings. Like all the others they had a fleet of smaller boats: Steam picket boat, one supply barge, two rowing yawls and two dinghies.

Hull construction and general design

The Pillau class hull ended as 134.30 meters (440 ft 7 in) long at the waterline, 135.30 m (443 ft 11 in) overall, with a beam of 13.60 m (44 ft 7 in) and draft of 5.98 m (19 ft 7 in) forward, 5.31 m (17 ft 5 in) aft. Nominal calculated displacement of 4,390 metric tons (4,320 long tons) standard as designed reached 5,252 t (5,169 long tons) when fully loaded. They were not particularly overweight. Construction called for transverse and longitudinal steel frames and below the waterline, it was subdivided into sixteen watertight compartments, and completed by a double bottom extending for 51% of the total jull length.

Armor protection

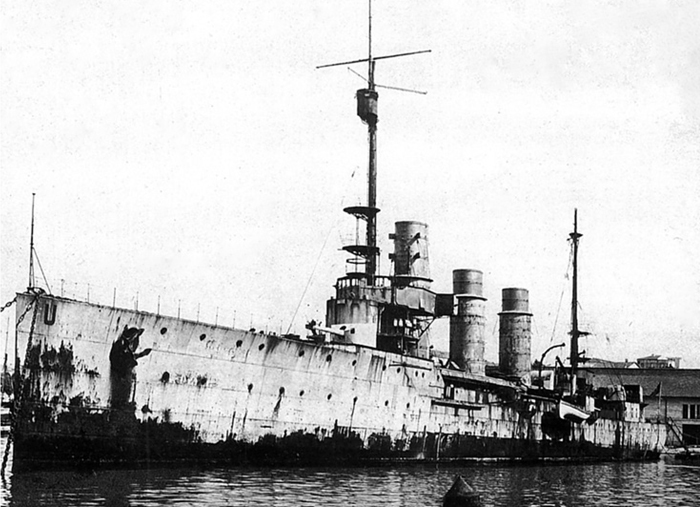

Pillau in port

The Russian Navy imposed changes specific to them in the design, notably getting rid of a waterline armored belt. Instead, they had an armored deck 80 mm (3.1 in) thick in the central section, up to the bow, but tapering down to 20 mm (0.79 in) aft. It was sloped with a layer of 40 mm (1.6 in) on either side on the upper portion of the sides by default of a belt. Main battery guns had 50 mm shields. Conning tower received 75 mm (3 in) thick walls, completed by a 50 mm (2 in) rooftop. That was it. It was design to somewhat resists destroyer fire but not much, and the ASW compartimentation to delay a sinking. Speed was the actual, active protection.

Powerplant & Performances

The propulsion system comprised as said above, two sets of (German Admiralty) Marine steam turbines. They drove two 3.5-meter (11 ft) bronze propellers. Steam camle also froma mix of six coal-fired Yarrow water-tube boilers, and four oil-fired boilers fromp the same manufacturer. They were trunked into three funnels on the centerline. Fortunately for them, the Germans ordered these boilers soon enough.

Performance-wise, these were rated for 30,000 shaft horsepower (22,400 kW) total, in order to reach of top speed of 27.5 knots (50.9 km/h; 31.6 mph). For range, they carried each some 620 t (610 long tons) of coal, plus 580 t (570 long tons) of oil for a grand total of 4,300 nautical miles (8,000 km; 4,900 mi) at the cruise speed of 12 knots (22 km/h; 14 mph), roughly half their top speed. For onboard elecvtrical power, they counted of three German Siemens turbo-generators for a total output rated at 360 kilowatts (480 hp), based on standard 220 Volts.

In general they were considered good sea boats, although fairly stiff. They suffered from heavy roll, though with a relatively predictable motion as gun platforms. They were considered maneuverable, just responsive at the helm, but slow in turns and bleeding speed fast hard rudder, up to 60%. Steering by the way depended on a single large rudder. In a head sea they also lost speed, as expected, not in sync with the wavelenght.

Armament

As designed, they were planned with eight 130 mm (5.1 in) Russian L/55 QF guns plus four 6.3 cm (2.5 in) L/38 guns from Obukhoff. However as completed for the Riechsmarine, this planned armament was standardized. Here is the detail. Specs are similar to other German cruiser’s guns, albeit they were the first German cruisers planned to mount 15 cm guns right away:

The 15 cm (5.9 in) SK L/45 guns in single pedestal mounts were side by side on the forecastle, four amidships and two side by side aft. Range of 17,600 m (19,200 yd), 1,024 rounds provided total. The four 52 mm AA were replaced later by two largely better 8.8 cm (3.5 in) SK L/45 AA guns. Theytwo torpeod tubes were mounted on deck. The 120 mines were carried on two long rails along the main deck, starting immediately aft of the forecastle.

- Eight 10.5 cm (4.1 in) SK L/45 guns

- Four 5.2 cm (2 in) SK L/55 anti-aircraft guns

- Two 50 cm (19.7 in) torpedo tubes

- 120 mines

Pillau in the winter of 1916

⚙ Pillau class specifications |

|

| Dimensions | 135.3 x 13.60 x 5.98 m (443 x 44 x 49 feets) |

| Displacement | 4,390 tons standard, 5,252 tons Fully Loaded |

| Crew | 21+421 wartime |

| Propulsion | 2 shafts steam turbines, 10 WT boilers, 30,000 hp. |

| Speed | 27.5 knots (50.9 km/h) |

| Range | 4300 nm @ 12 knots (7,960 km; 4,950 mi). |

| Armament | 8× 15cm/45 (8 in), 2x 8.8cm/45 (3.5 in), 2x 5cm TTs (19.7 in) |

| Protection | Decks 8cm (3.1 in), CT 7.5cm (3 in) |

Links & Resources

Pillau 1918

Books

Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships, 1906–1921.

McCartney, Innes. 2018. Jutland 1916: The Archaeology of a Naval Battlefield. Osprey Publishing LTD.

Gröner, Erich. Die deutschen Kriegsschiffe 1815—1945. Band 1 Bernard & Graefe Verlag, 1982

Gerhard Koop/Klaus-Peter Schmolke. Kleine Kreuzer 1903—1918. bernard & Graefe Vtrlag, 2004.

Links

Pillau-class cruiser – Wikipedia

SMS Pillau – Wikipedia

Pillau Technical Data (german-navy.de)

Pillau Class Cruiser – SMS Pillau, Elbing (worldwar1.co.uk)

PILLAU light cruisers (1914 – 1915) (navypedia.org)

Germany 15 cm/45 (5.9″) SK L/45 – NavWeaps

Germany 5.2 cm/55 (2.05″) SK L/55 – NavWeaps

Germany 8.8 cm/45 (3.46″) SK L/45 – NavWeaps

Pre-World War II Torpedoes of Germany – NavWeaps

Lost Cruisers – SMS Elbing (esstre.pl)

Легкие крейсера типа Pillau — Global wiki. Wargaming.net

SMS Elbing (1914) — Global wiki. Wargaming.net

SMS Pillau (1914) — Global wiki. Wargaming.net

SMS Pillau – Pillau-class cruiser – Wikipedia

SMS Elbing – Wikipedia

On warthunder

On navyword/narod.ru/Kreuzer

On navyword/narod.ru/Kreuzer

SMS Pillau

SMS Pillau

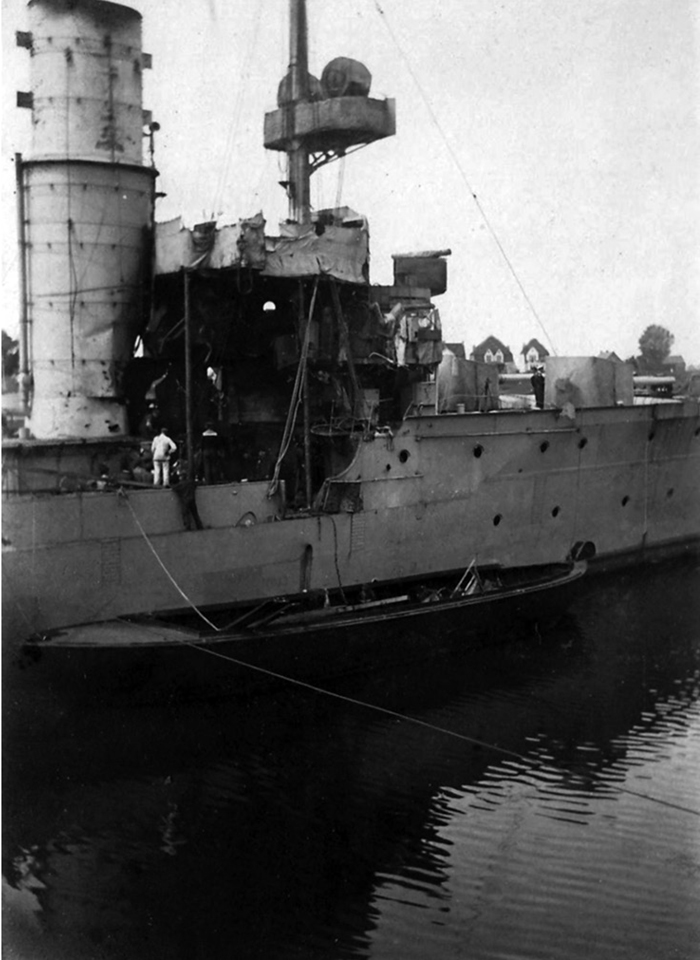

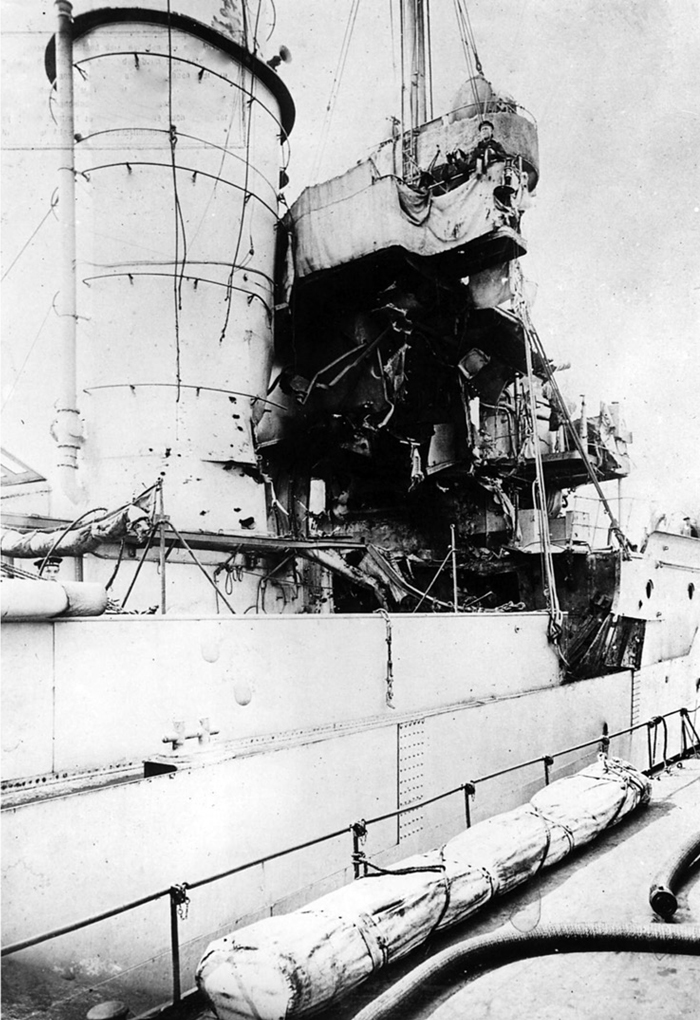

SMS Pillau damaged

WW1 service

SMS Pillau was commissioned on 14 December 1914, trained until assigned to II Scouting Group. She was first sent in the Baltic to take part in the Battle of the Gulf of Riga in August 1915. She screen a force of eight dreadnoughts and three battlecruisers, but on 13 August, Russian submarines ambushed her. Three torpedoes were coming her way, but missed. Pillau was in the second attack on 16 August and when minesweepers cleared the minefields on the 20th, she entered the Gulf, to withdrawn to Moon Sound again due to Russian submarines and mines. She was back in the north sea station by August.

Although she took part in several sweeps afterwards, nothing was of note until May 1916. Like her sister ship she was prepared for a major operation as part of the II Scouting Group, screening for the I Scouting Group, leaving on 31 May for the Skagerrak and at 15:30, Pillau and Frankfurt assisted Elbing, engaging the Britush criser screen, at 16:12 PM firing on HMS Galatea and Phaeton from 16,300 yards (14,900 m) and ceasing at 16:17 due to the range. 15 minutes later they spotted and engaged the seaplane tender HMS Engadine and afterwards were back on stations.

At around 16:50, the British 5th Battle Squadron spotted Pillau, Elbing, and Frankfurt, HMS Warspite and Valiant opening fire first at Pillau at 17,000 yards (16,000 m). She was straddled with almost near-misses, so decision was mlade to lay smoke and hide their escape at high speed. An hour later, German battlecruisers were charged by the destroyers HMS Onslow and Moresby and Pillau, Frankfurt drove them off with rapid fire. At 18:30, Pillau spotted HMS Chester and and scored several hits before disengaging due to the arrival of Rear Admiral Horace Hood’s Invincible class battlecruisers.

HMS Inflexible scored a hit on Pillau, with a 12 in (300 mm) shell which exploded below her chart house; although fortunately the blast went overboard. Due however to her starboard air supply shaft, the explosion blast was also vented into second boiler room which shut all six coal-fired boilers. She managed to maintain 24 kn (44 km/h; 28 mph) using only her four remaining oil-fired boilers and escaping in heavy fog. By 20:30, three boilers were back in operation so she was now steaming at 26 kn (48 km/h; 30 mph) out of harm.

And then came the night battle: The Britsh were closing their trap and at 21:20, the II Scouting Group met British battlecruisers, turning away, and while doing so, Pillau came under fire from them, but not close. HMS Lion and Tiger in all fired salvos at her without result before turning on SMS Derfflinger, and as reported by Pillau they were “very inaccurate”. Pillau and Frankfurt then spotted the cruiser HMS Castor leading several destroyers at 23:00, fired their torpedoes and turned back toward the German lines, keeping their searchlights off not to draw attention.

By 04:00 PM, the fleet managed to reach Horns Reef. At 09:30, Pillau was detached to assist SMS Seydlitz, still far from port. Pillau steamed ahead of her, guideing her to Wilhelmshaven until she however ran aground at 10:00 off Sylt. She was freedat 10:30 and could resume her voyage with Pillau and soon a division of minesweepers testing depth while screening them. Pillau ttempted to tow the battlecruiser but the hard strained line repeatedly snapped. Pumping steamers were there in the evening to help, Pillau guiding them until reaching the outer Jade lightship at 08:30. In all she had fired 113 main rounds, four 8.8 cm shells and a torpedo, with 4 killed, 23 wounded.

Her sister ship was rammed and sunk during the engagement leaving her the sold survivor of her class. Northing much happened until July 1917, whe she saw a mutiny aboard while in Wilhelmshaven. The 20th, 137 men left the ship to protest a cancellation of their leave, spent hours in the town and then returned to resume their tasks as a show of good will. But Pillau’s captain’s retribution was light, with only limited punishment. By late 1917, she was reassigned to the IV Scouting Group with SMS Stralsund and Regensburg.

By late October 1917 they were tasked to replace heavy units of the fleet after Operation Albion in the Gulf of Riga, with battleships of the I Battle Squadron. The operation was cancelled anyway due to the danger of mines and submarines. She wazs back to the North Sea on 31 October and the II Scouting Group.

On 17 November, they screened the battleships Kaiser and Kaiserin, which themselves cover minesweepers in the North Sea. British cruisers supported by battlecruisers and battleships arrived, which trigerred the Second Battle of Heligoland Bight. Königsberg (ii), Pillau’s group flagship, was damaged while the four cruisers evaded the trap but also draw them toward the German dreadnoughts. Both sides exhanges fire but eventually parted away, Pillau being unscathed.

On 23–24 April 1918, she was mobilized for an abortive fleet operation to Norway, as the Germans failed to locate the convoy, Scheer breaking off the operation. By October 1918 with the II Scouting Group she wa smobilized for the final attack planned in force, and Pillau, Cöln, Dresden, Königsberg(ii) were intended to lead a diversionary, drawing attack on merchant shipping directly n the Thames estuary. Karlsruhe, Nürnberg, Graudenz were to be sent to Flanders to draw out the British Grand Fleet. But on 29 October 1918, order to sail from Wilhelmshaven were met with wholesale mutiny forcing cancellation. Pending her fate, SMS Pillau was anchored in Germany, exlcuded for the fleet going to Scapa Flow for internement in 1918.

Italian service as Bari (1920-1943)

Bari in Venice during the interwar

Although she was listed in the Reichmarine, Pillau was stricken on 5 November 1919, surrendered to the Allies in Cherbourg on 20 July 1920 peing attribution. She was ceded to Italy as a war prize. As Bari, modified, she was recommissioned into the Regia Marina on 21 January 1924, as fleet scout (Esploratori). Her German AA guns were replaced with Italian 76 mm (3 in)/40 guns. In August 1925 she ran aground off Palermo. By July 1929, she joined Ancona and Taranto, Premuda as the Scout Division, 1st Squadron in La Spezia.

Modernized in the early 1930s (bridge, forward funnel) she was refitted for colonial service, witll all oil-firing boilers and additional oil bunker space. She lost her forward funnel, having the others cut cut down. Now based on 21,000 shp (16,000 kW) for 24.5 kn she reached 4,000 nmi (7,400 km; 4,600 mi) at 15 knots. She was deployed in the Red Sea and Italian East Africa until May 1938, relieved by the sloop Eritrea, ad by the start iof WW2, received six Breda 20 mm (0.79 in) and six 13.2 mm (0.52 in) HMGs.

In 1940 she became flagship of the Forza Navale Speciale taking part in the Greco-Italian War and covering the the invasion of Cephalonia and mainland Greece. From April 1941 and Greece defeat, she escorted convoys to Greek ports for occupation, but war with France in June 1940 saw her mobilized on the west coast until the capitulation of the latter. In 1942, the invasion of Malta was planned and Bari, Taranto were to cover the landing force. It was cancelled.

In November 1942 she became the flagship of the amphibious force landing at Bastia, French Corsica. Later she shell partisans off the Montenegrin coast, based in Livorno. Eventually placed in reserve in January 1943 the admirakty envisioned her conversion as AA ship (with six 90 mm/50 guns, eight 37 mmguns, eight 20 mm/65/70) but by 28 June it was stil not started when an US air raid devastated Livorno and badly damaged Bari. In September 1943, she was scuttled to avoid falling into German occupiers’s hands. The latter scrapped her partially in 1944. Stricken on 27 February 1947, she was raised on 13 January 1948 and BU.

SMS Elbing

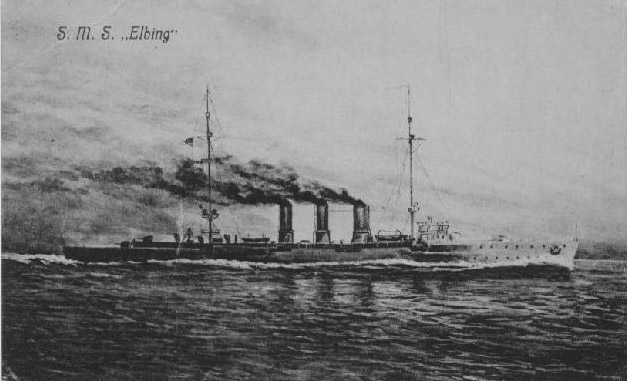

SMS Elbing

Postcard of SMS Elbing

SMS Elbing after some initial training was assigned to II Scouting Group, screening for Rear Admiral Friedrich Boedicker’s battlecruisers of I Scouting Group. She sailed away of them with destroyers for the raid on Yarmouth and Lowestoft on 24–25 April. While approaching Lowestoft, Elbing and Rostock both spotted the incoming Harwich Force (three light cruisers, 18 destroyers) from the south at 04:50. RADM Boedicker initially ordered the battlecruisers to continue while Elbing and five other light cruisers went to to fight off the Harwich Force.

At 05:30, the clash commenced at long range, and weent on wih little scores on each sides and perhaps caution, until the battlecruisers arrived at 05:47. At their sight, the British squadron quickly retreated. The overall result was a light cruiser and a destroyer both damaged. Boedicker did not chased them and broke off after receiving reports of British submarines closeby.

After several months of relative quiet service and few screening sorties without anything noticeable, she was in May 1916 under orders of Admiral Reinhard Scheer for a major operation. She served with the II Scouting Group attached to I Scouting Group, leaving the Jade at 02:00 on 31 May. After heading for the Skagerrak an hour and a half later before the main leet, her lookouts signalled at 15:00 the Danish steamer N. J. Fjord and she detached two torpedo boats to investigate.

Meanwhile HMS Galatea and Phaeton arrived to inspect the steamer, and fired on them at circa 15:30. SMS Elbing then turned to cover them and opened fire at 15:32, scoring the very first “hit” (turned out to be a dud) of the battle on HMS Galatea. The cruusers then turned north toward the 1st Battlecruiser Squadron chased by Elbing, still firing, and soon joined by SMS Frankfurt and her sister Pillau but they stopped at 16:17, out of range. They later spotted and engaged briefly the seaplane tender HMS Engadine, failed to score any hits and later returned to their screening stations.

At around 18:30, SMS Elbing encountered the cruiser HMS Chester and she opened fire, scoring several hits to later disengaged as RADM Horace Hood’s battlecruisers were spotted incoming. HMS Invincible actually scored a hit on SMS Wiesbaden, disabling while Elbing and Frankfurt fire their torpedoes at them, missing. Elbing was framed by water plumes while fleeing from the battlecruisers but labaged to keep the distance. At circa 20:15, Elbing’s suddent leakages in her boiler condensers had her slowing down to 20 kn (37 km/h; 23 mph) and she stayed at that regime during frantic repairs for four hours.

II Scouting Group meanwhile was ordered to take station ahead of the line ro take its night cruising formation. Elbing was unable to keep up and fell with IV Scouting Group. At 23:15, she teamed with SMS Hamburg when both spotted the British cruiser HMS Castor leading a pack of destroyers. Vleverly their captains used the British recognition signal when closing enough to engage them at 1,100 yards before turning on their searchlights. Bt night it was nigh-impossible to recoignise them.

The ruse worked and Castor was soon hit seven times and set on fire by both cruisers, and the British turned away in a panic, but not before the destroyers launched volleys of torpedoes at Elbing and Hamburg, whch manouevred hard to avoid them. One passed right underneath Elbing and failed to explode. The 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron also arrived, engaging IV Scouting Group and hit Elbing once, knowking out her wireless station with 4 killed, 12 wounded. Midnight arrived, and afterwards, the British net was closing on the retreating Germans.

Elbing ran on a the rear British destroyer screen, steaming on the port side of the German line with Hamburg and Rostock when SMS Westfalen opened fire first quickly by Elbing, Nassau and Rheinland. A Brithsh torpedo attack forced the cruisers to turn to starboard, but this placed in the path of thee German line. Elbing just managed to pass between Nassau and Posen, but Posen’s captain was too late to realize the manoeuver and rammed the cruiser, after trying to turn hard to starboard. Her bow went stright to Elbing’s starboard quarter.

The cruiser was holed below the waterline, which flooded the starboard engine room first. She took a 18° list, soon counter-balanced eighteen but was dead in the water, with her engines flooded and shut down. Steam started to condense in the pipes and soon the electric generators went down, the ship loosing all lighting and power. With the pumps down, there was little hope to save her while flooding spreaded throughout the underwater compartments, somewhat reducing the list, but still nit in danger of sinking.

At 02:00 AM, Elbing was helped by the torpedo boat S53 which came alongside to take aboard 477 officers and men, her commander and a few officers remaining on board either to save or scuttle their ship. Amazingly, they rigged an improvised sail to try to bring the ship closer to shore. But their effort was for naught: At 03:00, British destroyers were spotted coming from the south. Before their arrived, order was given to scuttle the ship while the ship’s cutter was lowered and set off, steaming back to port. At around 07:00, a Dutch trawler met the cutter and took the men aboard, returned as POWs to Holland. In total during the battle, Elbing would had fired 230 main 15 cm rounds and a torpedo.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign