Königsberg, Nürnberg, Stuttgart, Stettin

Königsberg, Nürnberg, Stuttgart, StettinWW1 German Cruisers

Irene class | SMS Gefion | SMS Hela | SMS Kaiserin Augusta | Victoria Louise class | Prinz Adalbert class | SMS Prinz Heinrich | SMS Fürst Bismarck | Roon class | Scharnhorst class | SMS BlücherBussard class | Gazelle class | Bremen class | Kolberg class | Königsberg class | Nautilus class | Magdeburg class | Dresden class | Graudenz class | Karlsruhe class | Pillau class | Wiesbaden class | Karlsruhe class | Brummer class | Königsberg ii class | Cöln class

The Königsberg class were a continuation of the 1902 Bremen class, inaugurating the “cities” serie, followed by the Dresden and Kolberg class, all relatively similar. Gradual improvements were made, and the four ships participated in WWI with various fortunes, also reflecting the German far-flung colonial Empire of the time: SMS Königsberg was scuttled in July 1915 after being damaged by British monitors in an east african river. Nürnberg was sunk in the Falkland battles in December 1914. Stuttgart and Stettin had more “cushy” positions in the home fleet and survived the war, although the first was converted as a seaplane carrier in 1918.

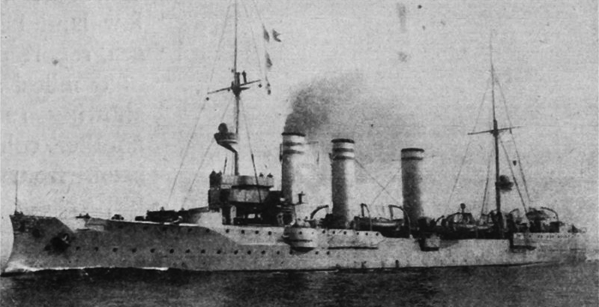

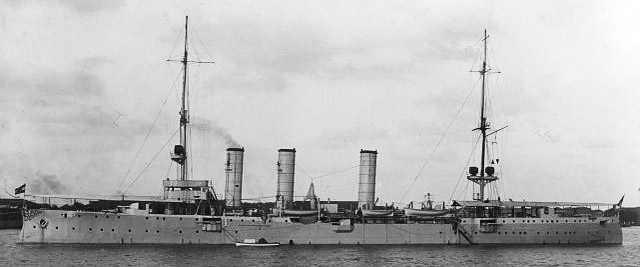

SMS Nuernberg

A continuation of the Bremen class

In Germany, the path towards light cruisers has been a rocky one. The 1880s saw unprotected cruisers that were just glorified gunboats, until the “cruiser-corvettes” and “aviso-cruisers” that tried various concepts of colonial vessels for peacetime and scouts in wartime. However the roots of German ligt cruisers (and the Königsberg class) could be found with certainty in the German Navy ambitious naval program which saw the construction order of eleven cruisers in 1896 (Gazelle class) and seven in 1901. They were considered “IVth class” cruisers, in the 3,000-3,700 tonnes range, the “mythologic” serie being smaller than the “city” serie, but both based on the same general model and armament. They were in general slightly larger and faster than the Bremen.

The 1898 Naval Law authorized in total thirty new light cruisers, to be completed in 1904. The third class, the Königsberg design, was to receive significant improvements in size and speed. Fittin the Königsberg class with turbines was just a move identical to the previous Lübeck of the Bremen class fitted with steam turbines for evaluation. The same was done for dreadnoughts later. SMS Königsberg, was authorized in 1904 and her sister-ships under FY1905 all included an additional boiler to increase top speed.

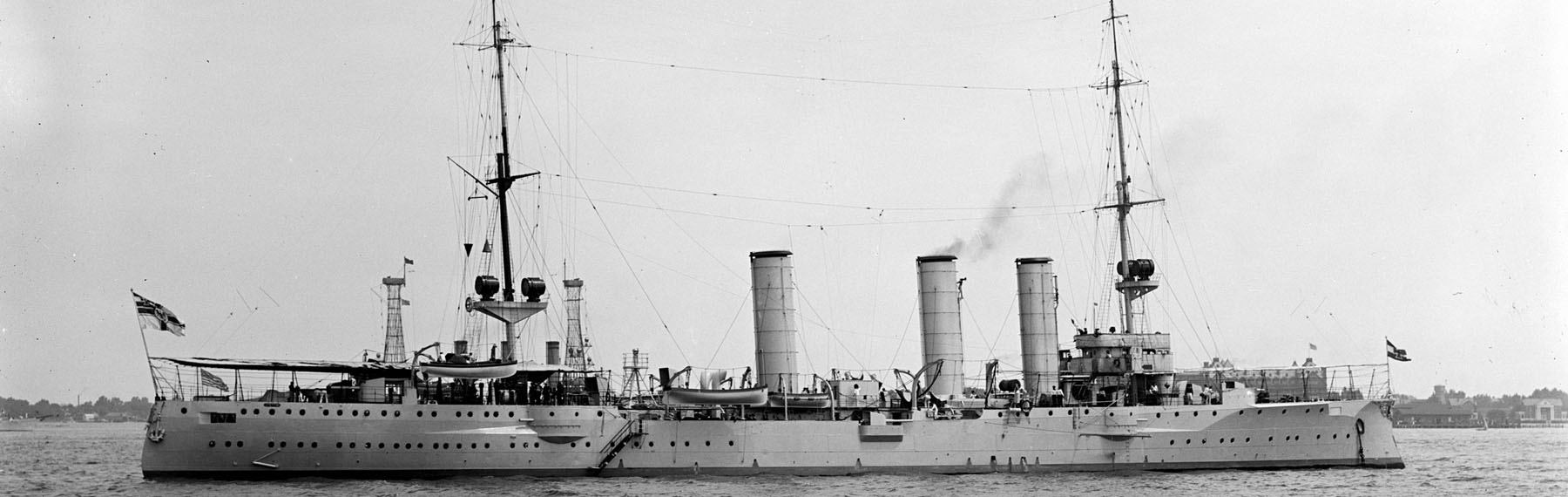

SMS Stettin, Bremen and Moltke in the Background, at Hampton Roads, 1912, the first and last deployment of a German capital ship in the US

The next iteration was still in the 3,000 tonnes range, with the same armament, ten 10,5 cm artillery pieces and 5,7 cm dual purpose rapid-fire guns. The next Dresden were close copies, but faster and larger: They reached 4,468 tonnes fully loaded versus 3,814 for the Königsberg class. The first ship was ordered as part of the 1903-04 programme and the next three as part of the 1904-05 programme. Stettin diverged from the others in many details, notably inaugurating turbine propulsion, but not enough to qualify as a sub-class, and both Nürnberg and Stuttgart diverged from Königsberg. This made these far more diverse compared to the homogenous Bremen class that preceded them, and semi-experimental. Experience with the Stuttgart motivated the adoption of turbines on the next Dresden.

As construction was not started yet, in December 1904, Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz (state secretary of the Reichsmarineamt) issued a report to Kaiser Wilhelm II. In it he warned that the new class should be delayed to make a comprehensive assessemnt of the Russo-Japanese War lessons, and incorporating them in the new design, which was possible even after the keel were laid down, to such extent. For example, it was shown that enhanced protection against naval mines for example was badly needed. The German design staff made several reunions after which they ordered alterations to the Königsberg class design:

-They added an additional watertight bulkhead (aft boiler rooms)

-Rearrangement from thirteen to fifteen Underwater compartments.

-Rearrangement of the coal storage bunkers

They thought to have seriously mitigated the risk of massive flooding, and the failure of multiple boilers. Although it was too late to alter the Königsberg scheduled to start in January, it was refined for the postponed three 1905 cruisers, which hull had to be lengthened by two meters (6 ft 7 in).

In the end, SMS Königsberg was started on 12 January 1905 (launched at Kiel on 12 December) while SMS Nürnberg was started (also at Kiel) on 28 August 1906, so considerably later, Stuttgart earlier by late 1905 at Danzig and launched in September, and Stettin in 1906 (Vulcan, Stettin, her namesake city). She was commissioned just after königsberg in October 1907. The last commissioned were SMS Stuttgart and Nürnberg, in February and April 1908 respectively.

About the name: Three successive cruiser classes were named “Königsberg” in the German Navy: The present one, the 1915 class, and the 1935 class, also called “K-class”.

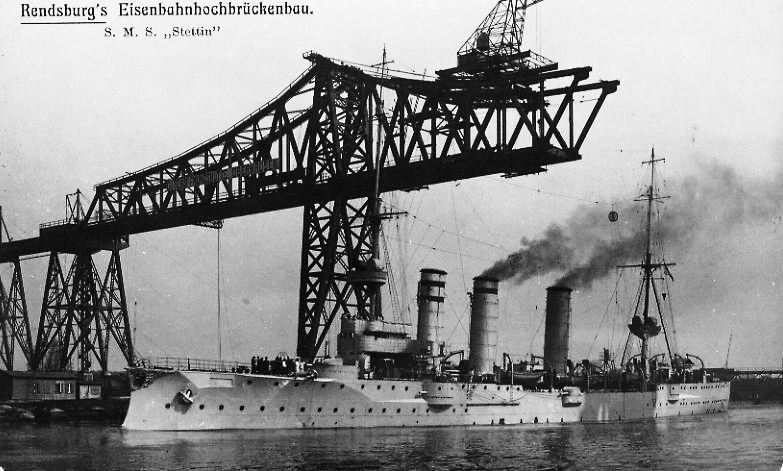

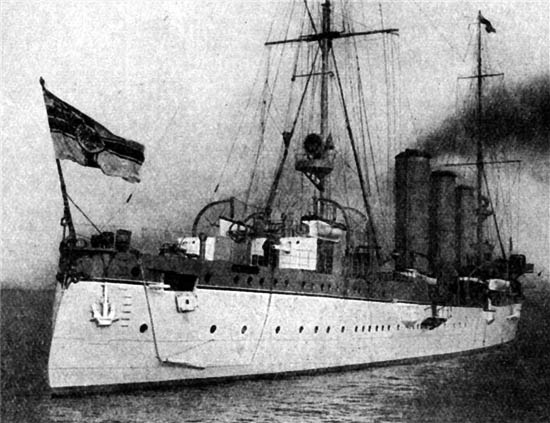

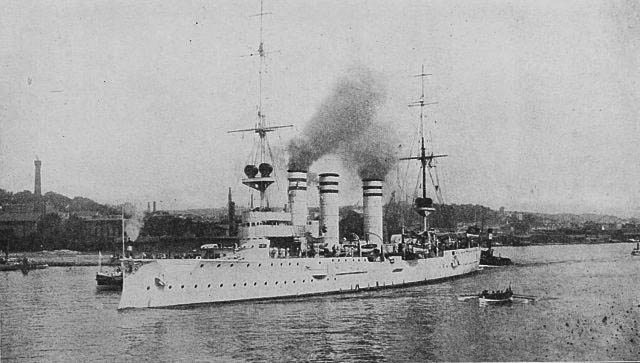

SMS Stettin on a postcard prewar

Design of the Königsberg class

Hull & Gneral characteristics

As said above, the Königsberg were slightly larger compared to the Bremen, although they kept the general same apperance, with a forecastle and poop, main battery deck with broadside sponson and masked artillery, three funnels, two masts, and a bow, which was there far less pronounced. For the first time, engineers went to the new “clipper bow” already experimented in earlier ships. The plough bow proved indeed problematic in heavy weather. The hull dimensions were increased: 114.8 m or 376 feets 8 inches in overall lenght, compared to 110.6 meters at the waterline and 111,1 meters overall (363-364 feets) for the Bremen class. The next three were even longer at 116.8 meters or 383 feets 2 inches at the waterline.

Königsberg was in fact slightly narrower at 13.20 meters versus 13.30 meters on the Bremen, but in order to improved ASW protection, this was increased to 13.30 m (43 feets 8 inches) again on her sister-ships. Koenigsberg’s draught was also less, at 5,2 meters (17 feets), versus her sister’s 5.3 m or 17 feets 5 inches. This allowed them to navigate in shallower waters compared to the Bremen class, with their 5.61 m draft (18 feets 5 inches). This helped Königsberg to hide in the Rufiji river in 1915.

Construction called for transverse and longitudinal steel frames. The steel outer hull was constructed above it, but there was no proper double hull but a double bottom for 50% of the total lenght. The underwater section, below the waterline, was divided into thirteen or fourteen watertight compartments (Königsberg 13, the other three 14). The crew comprised fourteen officers and 308 enlisted men. They had a number of small boats; A single steam-powered picket boat, a barge (used for coaling), a cutter, two yawls (used for training and liaison to the shore), and two dinghies. When all used, they can bring ashore a 80+ men landing party in one go.

Armour Protection

Armor protection was limited, as these ships were light cruisers: The belt had two layers of standard hardenened steel with backed by a layer of Krupp armor (thickness unknown, probably about 20 mm). In addition they had an armored deck 80 millimeters (3.1 in) thick amidships. It was tapered down to 20 mm (0.79 in) aft. It was linked to the belt by a sloped armor making a turtleback 45 mm (1.8 in) thick. The conning tower had walls 100 mm (3.9 in) thick, enclosed by a 20 mm thick roof. The main guns were protected by 50 mm (2.0 in) thick gun shields. Lighter guns were protected by steel wall lightly armoured (8-10 mm) to stop shrapnels only. The superstructures were unarmored.

Powerplant

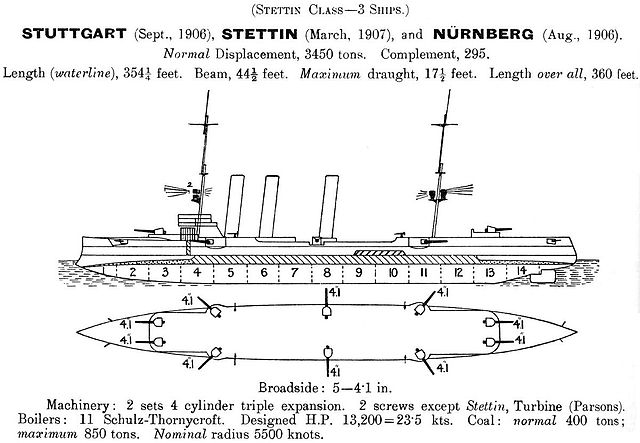

The first three Königsberg-class has a standard set of two 3-cylinder, triple expansion engines. They were rated at 13,200 indicated horsepower (9,800 kW). To speed as a result was 23 knots (43 km/h; 26 mph) as designed. SMS Stettin however tested a pair of British-provided Parsons steam turbines. They were rated at 13,500 indicated shaft horsepower (10,100 kW) allowing a better top speed at 24 knots (44 km/h; 28 mph). However on trials, all cruisers exceeded their design speed, by at least 0.5 knots. Steam was provided by eleven coal-fired Marine-type boilers trunked into three funnels. Only Königsberg had them heavenly spaced, the other three had a larger gap between the aft funnel and the two others. As usual they were tall and raked.

The Königsberg class cruisers carried 400 tons of coal (390 long tons; 440 short tons) in peacetime.

In wartime this could be pushed to 880 tons (870 long tons; 970 short tons), allowing for a calculated 5,750 nautical miles (10,650 km; 6,620 mi) at 12 knots. This was true for the lead ship only however: Nürnberg and Stuttgart could only cover 4,120 nmi and Stettin 4,170 nmi. SMS Königsberg also diverged with the rest of the pack by having two electricity generators, the others three generators each. Total output produced was rated for 90 and 135 kilowatts/100 volts respectively.

For manoeuvers, the ship had a single, large rectangular rudder. On trials, they were reputed to be good sea boats, with a picth and roll up to 20° however, and they became very wet at high speeds. They also suffered from a slight weather helm, in particular for SMS Stuttgart. Their metacentric height was .54 to .65 m (1 ft 9 in to 2 ft 2 in) depending of the ship.

Diagram on Janes, 1914

Armament

-Ten 10.5 cm SK L/40 guns in single mounts: 2 in tandem on the forecastle, six amidships, two in tandem on the poop. Maximum elevation was 30 degrees, range 12,700 m (13,900 yd). Total 1,500 rounds in store, 150 per gun.

-Two 8.8 cm (3.5 in) guns for SMS Königsberg

-Eight 5.2 cm SK L/55 guns for the three others, behind casemate deck walls.

4,000 rounds of ammunition were carried.

-Two 45 cm (17.7 in) torpedo tubes submerged broaside. They were provided five torpedoes in reserve.

This was reiniscent of the Bremen class and adopted also by the Dresden class. As proven by the duel between SMS Emden and Sydney, the lack of heavy guns (6 inches) proved fatal. However these guns were rapid-fire capable and can pour six high explosive shells at each volley on any ship and put it ablaze quite rapidly.

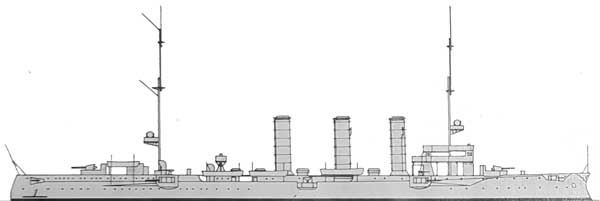

Author’s illustration of the Koenigsberg

Conway’s illustration of the Koenigsberg 1914

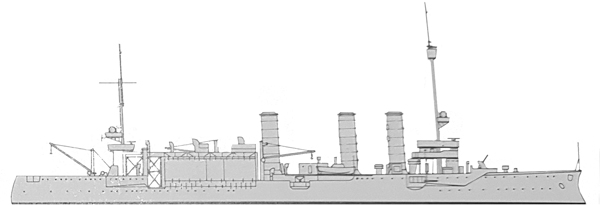

Conway’s illustration of the Stuttgart as converted as a seaplane tender 1918

⚙ Specifications |

|

| Displacement | 9,767 long tons (9,924 t standard, 12,207 long tons FL |

| Dimensions | 185 m oa x 19m x 7m (606 x 62 x 23 feets) |

| Propulsion | 4 shafts Parsons geared turbines, 8 Babcock & Wilcox boilers, 100,000 shp (74,570 kW) |

| Speed | 32.5 knots (60.2 km/h; 37.4 mph) |

| Range | 10,000 nmi (19,000 km; 12,000 mi) at 15 knots (28 km/h; 17 mph) |

| Armament | 5×3 × 6 in (152 mm)/47, 8x 5 in (127 mm)/25, 8 .50 cal.HMG, 4 floatplanes |

| Armor | Belt 2in (51 mm)-5 in (127 mm), turrets 1.25-6 in (152mm), CT 5 in (127mm), deck 2in (40 mm) |

| Crew | 868 |

The Königsberg class in action

SMS Königsberg

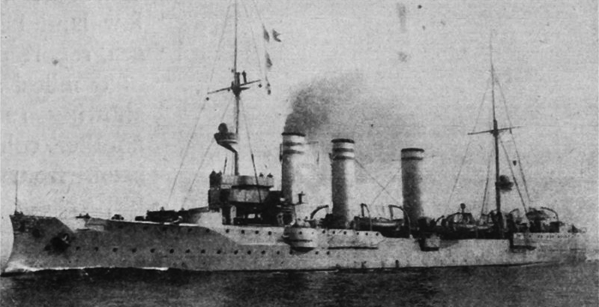

Konigsberg prewar

Peacetime service

Königsberg was ordered as “Ersatz Meteor” in the Imperial Dockyard in Kiel, launched and baptised by the Oberbürgermeister (mayor) of Königsberg, Siegfried Körte. She started her sea trials on 6 April 1907, interrupted when she was tasked to escort Kaiser Wilhelm II’s yacht Hohenzollern during the Kiel Week. In August she was present when Wilhelm II met Czar Nicholas II met. After her trials were completed on 9 September, she visited her namesake city and departed to join the scouting forces, replacing Medusa on 5 November 1907. She escorted Wilhelm II’s yacht again, with Scharnhorst and Sleipner in UK. They were visited by Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands as well. On 17 December, she escorted Prince Heinrich and a delegation to Malmö in Sweden, meeting King Oscar II. She spent 1908 in training routine and started at the end of the year a long training cruise in the Baltic, North Sea and Atlantic ending in December. Placed in drydock in 1908–09 for maintenance she was back in action by February 1909. A routine followed that year and 1910, but she suffered a collision with Dresden on 16 February in the Kiel Bay while escorting the Kaiser. Both had significant damage but none was injured. After repairs in Kiel, SMS Königsberg won the Kaiser’s Schießpreis (Shooting Prize) for gunnery marskmanship. Until September 1910, Fregattenkapitän Adolf von Trotha became captain.

Könisberg sailed to the Mediterranean from 8 March to 22 May 1911, ecorting Wilhelm II’s Hohenzollern. On 10 June she was relieved by Kolberg and transferred to Danzig, and drydocked on 14 June for modernization. On 22 January 1913 she was recommissione, replacing Mainz. She also served with the training squadron in April. By early 1914, a critical decision was made: The high command decided to send SMS Königsberg to defend German East Africa, replacing the old unprotected cruiser Geier used as station ship.

On 1 April 1914, she greeted a new captain, Fregattenkapitän Max Looff and departed Kiel on 25 April 1914, stopping en route in Wilhelmshaven. Her mission was a two-year deployment to German East Africa, but none thought at that tie this was also her last. She passed through the Mediterranean Sea, stopping in Spanish and Italian ports en route before crossing the Suez Canal. SMS Königsberg stopped in Aden and eventually reached Dar es Salaam, her main base and capital of German East Africa. It 5 June 1914. She arrived just in time to take part in the anniversary parade of the Schutztruppe (Protection Force). Königsberg’s captain started to sturdy the surrounding and organize a defense at Bagamoyo. For the locals, the new cruiser was nickname “Manowari na bomba tatu” translated by “the man of war with three pipes”.

After the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, Captain Looff decided to leave Mabamoyo and return to Dar es Salaam on 24 July, to take as much coal her could onboard in prevision of action. He set in place a coast watch network, report any approaching enemy ships. He also set in place a plan to protect local German shipping. On 27 July 1914 he was warned by the Admiralstab about the rising tension and they were informed that the British Cape Squadron from The Cape in South Africa was prepared for blockading SMS Königsberg. It comprised the crisers HMS Astraea, Hyacinth, and Pegasus. Looff prepared his cruiser for combat, ready to sail out at any short notice. On the afternoon of 31 July 1914, that’s what he did, and he soon was spotted and shadowed by the slower British cruisers. Loof managed to steer his ship in a welcomed rain squall and broke contact the following day. He arrived off Aden on 5 August as news of hostilities came out.

Wartime raiding, in search of coal

Koenisberg’s artillerie was partly relocated in various land casemates along the river’s banks.

SMS Königsberg was ordered to attack British trade lines close and in the Red Sea. However short of coal, Looff could do little: His collier, the Koenig was blockaded in Dar es Salaam. The British also purchased all the coal in Portuguese East Africa, denying it to Königsberg. Looff also radioed Zieten to prevent her taking the Suez Canal. He also warned the German freighter Goldenfels, which mistook her at first for a British cruiser. Königsberg eventually fired a bow warning to force her to stop and warn captain about the situation. On 6 August, SMS Königsberg captured the freighter City of Winchester off Omani coast, leaving a prize crew. Both later met Zieten and sailed in the isolated Khuriya Muriya Islands. There, SMS Königsberg loaded all the coal from City of Winchester, and the latter was sunk while the British crew ended onboard Zieten, which sailed to Mozambique. SMS Königsberg later spotted the German steamer Somali (Korvettenkapitän Zimmer) from Dar es Salaam with 1,200 t of coal onboard. When meetig Somali, SMS Königsberg had just 14 t of coal left !. 850 t were tansferred, after which the cruiser could now reach Madagascar. No ships were encountered en route, so the cruiser coaled once again from Somali on 23 August.

The British meantime shelled Dar es Salaam, destroying the German wireless station. At that point however, SMS Königsberg’s engines were worn out and badly needed an overhaul. Captain Loof found a suitable place to proceed, the Rufiji Delta recently surveyed by Möwe. On 3 September 1914 he entered at high tide, passed the the bar and made her way up the river. Meannwhile Loof had his Coast watchers stationed at the mouth of the river with telegraph lines to warn him of approaching British ships. Zimmer (Somali) sent small coastal steamers to resupply Königsberg. One spotted HMS Pegasus patrolling the coast. Loof looked a map and deduced the British crioser would probably coal at Zanzibar on Sunday. He decided to attack Pegasus in port, even before starting his overhaul.

The Battle of Zanzibar

SMS Konigsberg in Bagamoyo

On 19 September, SMS Königsberg left the Rufiji river, arriving off Zanzibar as planned the following morning, spotted the British cruiser and started to open fire at 7,000 meters (23,000 ft) at noon, 05:10. This became the little-known “Battle of Zanzibar”. During 45 minutes, a completely surprised HMS Pegasus was hammered by 105 mm rounds, until she rapidly caught fire. After all her guns were silenced, her hull and superstrctures crippled by shrapnel, she rolled over to port and sank. Although well before this, Crewmen raised a white flag, it could not be seen from Königsberg between heavy smoke and water plumes. The British had 38 dead and 55 wounded. SMS Königsberg then avenged Dar-Es-Salaam by pounding the wireless station. He ingeniously disguised as mines with barrels filled with sand, dumped into the harbor entrance before leaving the harbor. SMS Königsberg en route lso spotted the picket ship Helmut, quickly sank by just three shells. She returned to the Rufiji River to resume overhaul. Parts were transported overland to the shipyard in Dar es Salaam, which was quite an expedition in itself. While moored off the town of Salale captain Loof ordered his cruiser to be heavily camouflaged, with a set of defensive arrangements: Soldiers and field guns defending the approaches, extended network of coast watchers and telegraph lines, improvised minefield in the delta. This took weeks of preparations.

Meanwhile the British learnt about the sinking of the Pegasus and wholesale destruction at Zanzibar. The admiralty ordered troop to be sent from India, and a new flotilla mmounted to search for the German raider under command of Captain Sidney R. Drury-Lowe. On 19 October 1914 HMS Chatham spotted and captured the German East Africa Line “Präsident”, off Lindi. The boarding party found documents about her supply to Königsberg in the Rufiji in September. This was quite a find, and on 30 October, HMS Dartmouth eventually spotted both Königsberg and Somali in the Rufiji delta. Soon after, HMS Chatham, Dartmouth and Weymouth blockaded Delta.

Blockade of the Rufiji River

On 3 November 1914, the squadron started a long range shelling, trying to hit Königsberg and Somali, but she was difficult to located, well blanketed by vegetation in a thick mangrove swamps which concealed them. British fire indeed was done from outside the river. The collier Newbridge was eventually converted as a blockship and sunk in the main channel, on 10 November, despue German fire from the rover’s banks. Looff decided to move upriver, escaping a possible Britush lucky hit. He also hoped to distract many British vessels from other areas (and the chase of Von Spee’s squadron). Soon indeed, the British added the cruiser HMS Pyramus and HMAS Pioneer to the squadron.

Port bow of the German cruiser

Denis Cutler of Durban a South African civilian convinced the admiralty to commissio his private plane into the Royal Marines. The Royal Navy also requisitioned the passenger ship Kinfauns Castle as tender for Cutler’s aircraft. Cutler however had no compass and went missing at his first flight, forced to land on a desert island. Her however located Königsberg during his second attempt, the third flight being made by a passenger, a Royal Navy observer, which noted the positon on the map. However he was shot down and grounded, could not be repaired until parts arrived from Mombasa. Two Royal Naval Air Service Sopwiths were also brought in the meantime, but they were soon wrecked by tropical conditions. Three Short seaplanes at least made a few flights before being grounded for the same reasons. There was still the 12-inch (305 mm) from HMS Goliath available to sink SMS Königsberg with the right range, but shallow waters prevented this. In December 1914 Oberstleutnant Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, C-in-C in german east africa, requested crew members for his campaign and only 220 men were left on the cruiser to maintain its fighting capabilitie, but not to sail out. Königsberg again changed location up river on 18 December and the the 23 two shallow-draft ships went after her. They found and hit Somali but were forced back by defensive fire.

Captain loof was concerned however of his shortage of coal, but also ammunition, food, and medical supplies, with a crew ravaged notably by malaria and a low morale. However soon, the captured British Rubens, renamed Kronborg with a Danish flag and false papers was prepared to sail to relieved Könisgberg with a selected crew chosen for their ability to speak Danish. The ship was packed with coal, field guns and ammunition, small arms and supplies. Königsberg prepared to sail out and met her, then sail home if possible. However HMS Hyacinth spotted Kronborg, and she was chased off to Manza Bay, trapped and forced aground, put ablaze. The crews salvaged much of her cargo which was latted transport to German East Africa.

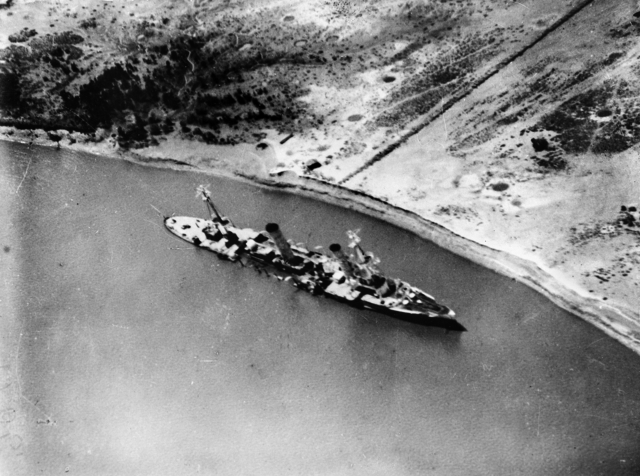

Bundesarchiv – Koenigsberg in east africa

1st Battle of Rufiji Delta

By April 1915, British Admiralty approved Drury-Lowe’s plan he wrote back in November. He planned to use shallow-draft monitors, and these were HMS Mersey and Severn, armed with two 6-in guns each, coming from home. SMS Königsberg meanwhile was moved further upriver and by 6 July 1915, the two monitors crossed the outer sandbar, answering as they went up river, to the heavy Germa nriver banks fire. When both spotted the cruiser and went 10,000 yd (9,100 m) close, in range for teir own guns, but not from Königsberg’s own, they opened fire. Aircraft were used for artillery spotting. However the monitors’ captains mismanaged their distance and were found at range from the German cruiser, which quickly answered: Mersey was hit twice, disabling her forward 6-inch gun. Königsberg was hit four times, partly flooded. The battle went on for three hours, but eventually SMS Königsberg’s rapid fire and marksmanship drove both monitors off.

2nd Battle of Rufiji Delta

Both monitors were back on 11 July, repaired and with better preparations, with the same plan. When in place, they started a five-hour bombardment, but Königsberg answered first with with four guns, then three guns remaining, two and down to just the last around 12:53. The anchored monitors knocked out all guns and started a major fire at Königsberg’s stern, plus heavy casualties. At 13:40, Königsberg was low on ammunition and on valid personal. Looff decided to call it off. Her ordered his crew to abandon ship, and drop the breech blocks plus detonate two torpedo warheads at the bow for a proper scuttling. The ship rolled slowly to starboard and sank up to the upper deck.

The cruiser now scuttled in the river, as spotted by RAF planes.

Close view of the cruiser, scuttled.

Koenigsberg artillerie went on fighting with Lettow-Vorbeck in the east african campaign until 1917

The register listed 19 kills and 45 wounded, including Captain Looff. The British retired and at the end of the day, the crew returned to retrieve the flag, and salvage gns and other equipment. The guns were converted into field artillery pieces or placed into coastal positions. They all saw service in the East African campaign. All ten guns were later repaired in Dar es Salaam and saw service late into the war in various places. Eventually the remaining crew company, Königsberg-Abteilung surrendered on 26 November 1917, interned in Egypt. In 1919, they were celebrated as heroes at the Brandenburg gate. Hence ended an episode which inspired Hollywood’s “The African Queen” with Humprey Bogart in 1951.

SMS Nürnberg

Ordered as “Ersatz Blitz” in the Imperial Dockyard, Kiel SMS Nürnberg launching on 28 August 1906 was headed by the mayor of her namesake city, Dr. Georg von Schuh. After fitting-out and sea trials she was commissioned n 10 April 1908. Her serice in German waters went on between training and limited cruises until she was sent overseas in 1910, assigned to the East Asia Station at Tsingtao (Maximilian von Spee). She was sent off the Mexican coast during the revolution to safeguard german interest and personel there. The rest of her peactime career was uneventful.

Wartime Operations

Before the war broke out, she was releived by SMS Leipzig off Mexico and returned to Tsingtao. On 6 August 1914, Nürnberg eventually met the East Asia Squadron already en route back home in Ponape. Spee decided to gather all his forced forces off Pagan Island, northern Marianas, by then a German possession with coal depots and wireless transmission bases. The available colliers, supply ships, and passenger liners received a signal to sail there and meet the East Asia Squadron. On 11 August, the squadon arrived and soon a few supply ships arrived as well as SMS Emden and the AMC Prinz Eitel Friedrich.

The four cruisers headed for Chile. On 13 August Commodore Karl von Müller (Emden) convinced Spee to detach his ship for commerce raiding, drawing attention to him and creating a diversion. This was accepted. The rest is a fantastic story, the stuff of legend. The squadron coaled at Enewetok Atoll (Marshall Islands) on 20 August and by 6 September, Spee detached this time to send Nürnberg assisted by the tender Titania to Fanning Island, cutting the communication cable there. To confuse British observers, the cruiser was flying a French ensign and approached enough to open fire, destroying the station. This happen at noon on 7 September. SMS Nürnberg then headed for Christmas Island where the squadron waited. Spee sent Nürnberg on 8 September to Honolulu, to send news from his intentions to the German High Command via neutral countries. Nürnberg was chosen because the British only knew she left Mexican waters, and her presence in Hawaii would have been normal. Her captain contacted German agents there, instructing them to prepare coal stocks in South America. Nürnberg departed soon, with news of fall of German Samoa.

On 14 September, Spee sent his two armored cruisers to raid the British base at Apia and Nürnberg meanwhile was ordered to escort the squadron’s colliers and join them here later; The Battle of Papeete took place on 22 September, Nürnberg with the rest of the squadron Squadron bombarding the French colony. and sinking the gunboat Zélée. Fear of mines however prevented von Spee from seizing the coal there. On 12 October, the squadron arrived off Easter Island, joined by Dresden and Leipzig, coming from American waters. A week after, coaling, they departed for Chile. There, Nürnberg would take part in two major naval battles, sealing her fate to Von Spee’s squadron.

Battle of Coronel

At last, the British HQ learned about the German squadron off South America, and decided to gather all their available forces in the area under command of Rear Admiral Christopher Cradock: The armored cruisers HMS Good Hope and Monmouth, light cruiser Glasgow, auxiliary cruiser Otranto, the old battleship Canopus, and the armored cruiser Defence (steaming as fast as possible, but which arrived too late to take part in the batte). Canopus was too slow and Cradock ddcided to left her behind and by the evening of 26 October, the East Asia Squadron was off Mas a Fuera (Chile), learning that HMS Glasgow was previously in Coronel. On 1st November, Spee fell upon Good Hope, Monmouth, Otranto and Glasgow. At 17:00, Glasgow spotted the Germans in turn and Cradock formed a line. Spee however hold off until the sun set more to have the British ships silhouetted by the sun. Nürnberg was bishing but rushed forward. Arriving as it was over, Nürnberg however spotted drifting HMS Monmouth, finishing her off, down to 550 to 900 meters.

On 3 November, Nürnberg and her squadron steamed to Valparaiso to resupply in 24 hours as per international law. Leipzig and Dresden meanwnhile, due to the same limitation, coaled at Mas a Fuera. Spee ordered the while squadron to Mas a Fuera. Now with free hands, that was raiding season. On 21 November, the East Asia Squadron coaled again at St. Quentin Bay and headed for Santa Elena, where they would meet colliers from Montevideo and rpepared to fall on the now unprotected south american trade lines.

Battle of the Falkland Islands

When ready, the squadron sailed to Port Stanley, in order to rampage the entire island, notably its wireless station, coal stocks and installations. However in between, the British sent two battlecruisers, Invincible and Inflexible, plus four cruisers (Vice Admiral Doveton Sturdee) and they waited for them. On 8 December, Nürnberg spotted the island, but she was drove off by the old battleship Canopus. Spee decided to retreatand steamed away at 22 knots with Nürnberg second ship in the line, framed by the two armoured cruisers. Sturdee’s battlecruisers caught up and the battle commenced at 12:50; Spee chivalrously decided to fight off the battlecruisers with Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, allow all three light cruisers to flee, but themselves were soon chased by Sturdee’s own light cruisiers. The hunt for Nürnberg, Dresden, and Leipzig started.

HMS Kent was tasked to hunt Nürnberg down and at 17:00, Nürnberg’s own worn out machinery made her unable to distance the British cruiser so she turned and open fire at around 11,000 m (12,000 yd). Kent only replied about 6,400 m (7,000 yd) away, and Nürnberg turned to port to present her broadside. Both ships pounded themselves on parralel courses, distance dropping down to 2,700 m (3,000 yd). Nürnberg was hit by heavier caliver rounds and was soon devastated, in fire around 18:02. By 18:35, she was silent and Kent ceased fire to approach, but when noticing she was still flying her colors, she resumed fire, until Nürnberg struck her colors. Ken stopped and lowered her lifeboats to pick up survivors, only getting 12 out of the water. The German cruiser sans at 19:26. Among the dead were Otto von Spee, following his father in his watery grave. Nürnberg however hit Kent 38 times, with little effect however.

SMS Stuttgart

After her commission on 1 February 1908, SMS Stuttgart spent a few years in the Baltib and North sea, alternating the routine of seasonal training. In August 1914, she was tasked with patrol duties in the Heligoland Bight. Like other cruisers, she led torpedo boat flotillas, rotating through nightly patrols and roaming the North Sea. Stuttgart made her first on 15 August, with SMS Cöln leading respectively the I and II Torpedo-boat Flotillas.

On 15–16 December, Stuttgart was part of the raid on Scarborough, Hartlepool and Whitby, shelling the towns. Next she was assigned to the cruiser screen of the Hochseeflotte, and providing distant cover to Franz von Hipper conducting hos batlecruiser in another raid. British destroyers were spotted by the screen so Admiral von Ingenohl ordered the Hochseeflotte to depart. At 06:59, SMS Stuttgart and Roon, and Hamburg spotted Jones’ destroyers, which started shadowing them until 07:40 were both cruiser turned to fight them. At 08:02, Roon spotted two light cruisers and ordered a retreat towards the High Seas Fleet.

On 7 May 1915, the IVth Scouting Group, was costituted with the Stuttgart, Stettin, München, and Danzig leading twenty-one torpedo boats. They were sent east in the Baltic Sea to support a German attack on the Russian port of Libau. under orders of Rear Admiral Hopman, at the head of the reconnaissance forces. They were ordered to screen northwards in order to spot and intercept any Russian naval forces exiting the Gulf of Finland. The rest of the fleet would shell the harbor. The Russians indeed soon sailed out with Admiral Makarov, Bayan, Oleg, and Bogatyr. SMS München was engaged but not too long. Libau eventually fell to the German army. Stuttgart sailed west, towards the High Seas Fleet. Nothing much happened afterwards, between maintenance, fleet exercizes and patrols, until May the next year.

SMS Stuttgart indeed was by then still in the IV Scouting Group (Commodore Ludwig von Reuter), when she departed Wilhelmshaven at 03:30 on 31 May, to join the rest of the Hochseeflotte. As usual her unit was tasked of screening and she was posted with the torpedo boat V71 at the rear of the fleet, close to the II Battle Squadron. Stuttgart missed therefore the early battle when the battlecruisers and their own screens were engaged. However as the day was ending, soon before dark at around 21:30, she spotted the British 3rd Light Cruiser Squadron. L.Von Reuter back then was posted south of the High Seas Fleet, far from the Grand Fleet. Poor visibility ensured only München and Stettin could engage at long range British cruisers, Stuttgart being the fourth ship in the line. At some point however, her spotters saw a British ship in the haze, but since she was already under fire, to not complicate the other spotters’s work, the captain ordered to hold fire. There was a tur hard to starboard, trying to draw the cruisers towards the Hochseeflotte, but the 3rd Light Cruiser Squadron refused and disengaged.

The following night fighting up to the 1st June saw the Hochseeflotte engaging the British rear, and the IV Scouting Group met by chance this time the 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron. It happened at projector light, at close range: First illuminated was HMS Southampton and HMS Dublin, which took a beating. Stuttgart and Elbing then concentrated on HMS Dublin, hit eight times, probably from Stuttgart, but damage was limited. On fire however, both cruisers retreated, while the Germans were bating them towards the battlecruisers Moltke and Seydlitz. SMS Frauenlob was hit and sunk by Southampton dueing this brawl. SMS Stuttgart was on her starboard until she lost contact with the IV Scouting Group and ended with the I Battle Squadron. Around midnight she saw another fight, concealed in the darkness when the I Battle Squadron dreadnoughts repulse British destroyers. Stuttgart was found when they turned away to avoid torpedoes, between Nassau and Posen. At around 02:30, Stuttgart was now at the head of the German line, in front of SMS Westfalen, leading I Battle Squadron home. She then screen III Battle Squadron and SMS Friedrich der Grosse, leading the pack. Her ammo stores were 64 rounds lighter but this was little in comparison to the rest of the fleet, and she has not even a scar to prove her engagement.

After Jutland, the fleet was mainly inactive. At some point the admiralty toyed with the idea of seaplane tenders and it was clear that converted civilian steamers were too slow for the fleet. Like for the British, it wa clear that converting a cruiser was the right direction. In 1918, Stuttgart was chosen for conversion. Plans were ready and constrcution started in February 1918 at the Imperial Dockyard, Wilhelmshaven. It was over in May 1918. For this, she lost her aft 10.5 cm guns, two forward broadside guns, leaving four broadside guns only. Two 8.8 cm SK L/45 AA guns were installed instead on the forecastle and the torpedo tubes were kept. The aft was completedly flattened and two large hangars were mounted aft of the funnels. They were designed to house two seaplanes, with a third seaplane carried on top of them. This number soon appeared insufficient for porper support so the plans were quickly modified for a full conversion as seaplane carrier, but this was never carried out and as a seaplane tender, SMS Stuttgard was never operational again. Stricken on 5 November 1919 she was surrendered on 20 July 1920, became war prize “S” to UK but was BU.

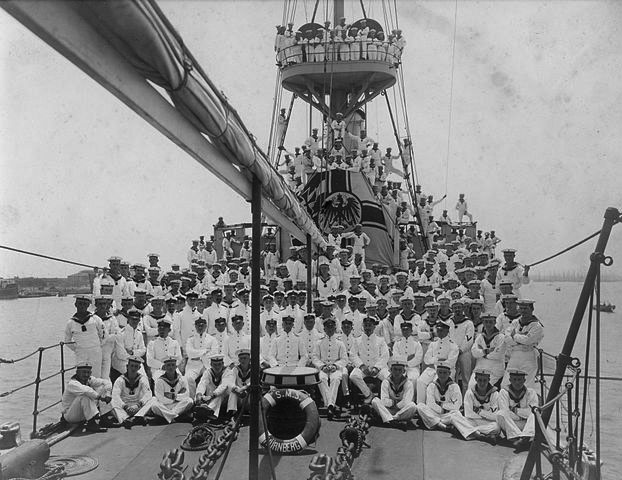

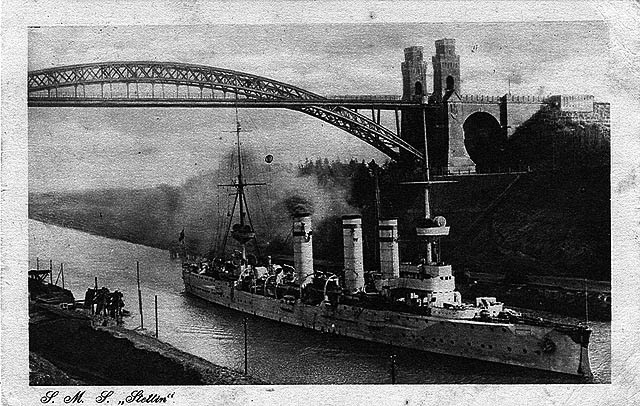

SMS Stettin

Stettin cossing the Kiel canal

Stettin was ordered as “Ersatz Wacht” in AG Vulcan shipyard (Stettin) in 1906, launched on 7 March 1907, and commissioned after her sea trials on 29 October 1907. She served the first years in German waters, alteranting between the baltic and North sea. In early 1912, she was part of a goodwill cruise to the USA with Bremen and SMS Moltke, the only German capital ship in the US ever. She arrived off Hampton Roads, Virginia, on 30 May, greeted by President William Taft, onboard USS Mayflower. She toured East Coast cities for two weeks before going back to Kiel on 24 June. Nothing much happened until the summer of 1914.

Stettin in Hampton Roads, 1912

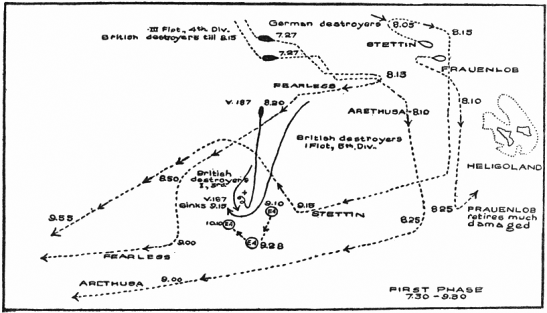

In August 1914, Stettin was patrolling the North Sea, screening the High Seas Fleet. On 6 August wich SMS Hamburg she escorted U-boats into the North Sea. They were posted in a way to ambush the British fleet after she was drawn out. The cruisers were back on 11 August. On the 28, SMS Stettin participated in the Battle of Heligoland Bight. With Frauenlob and Hela she supported torpedo boats patrolling the bight and Stettin was at anchor, posted northeast of the island under overall command of Rear Admiral Franz von Hipper. When the attack started, Hipper dispatched Stettin and Frauenlob in support and at 08:32, Stettin departed in support of the beleaguered TBs. 36 minutes later, she fell on British destroyers at around 8.5 km (5.3 mi). The British DDs immediately brok off. At 9:10, Stettin stopped the chase and fell back to Heligoland, but she had been hit once, on the starboard No. 4 gun. She had saved the torpedo boats V1 and S13 and at around 10:00 at top speed she was back, spotted and engaging eight British destroyers. They were dispersed and sent fleeing. At 10:13, visibility was so poor she broke off this second chase. She took several light caliber ht without much damage but a few men wounded and killed. Around 13:40 she met SMS Ariadne, which just engaged and fled British battlecruisers. Stettin was engaged herself at 14:05 but in the haze accuracy was very poor and she escaped. At 14:20, she was now near SMS Danzig when Von der Tann and Moltke arrived five minutes afterwards and Hipper himself behind onboard Seydlitz. It was all over now and Stettin was back to Wilhelmshaven by 21:30.

First phase of the Battle of Heligoland bight, 1914

On 15 December 1914, I Scouting Group’s battlecruisers raided Scarborough, Hartlepool, and Whitby while High Seas Fleet (Friedrich von Ingenohl) stood in distant support, and Stettin, leading two flotillas of torpedo boats screened their rear. Skirmishes between rival screens in falling darkness convinced Ingenohl he faced the the Grand Fleet and Kaiser himself odered him back. There was no occasion for Stettin to fire that day and night. Nothing much happened until the 7 May 1915, when the IV Scouting Group (Stettin, Stuttgart, München, Danzig, 21 TBs) was rushed to Baltic Sea in support a of the attack of Libau (see above). On year was spent in between maintenance and exercises but nithing much to notice. In late May 1916 however, Stettin became flagship of Commodore Ludwig von Reuter, commander of IV Scouting Group when it sailed out in screening support. They missed the early British and German battlecruiser squadron’s battle, and Stettin later steamed ahead of battleship König, the rest of IV Group dispersed in search of posssible British submarines.

SMS Stettin in 1914

Around 21:30, HMS Falmouth was spotted and engaged by Stettin and München, before turning into the haze. Around 23:30, Moltke and Seydlitz almost collided with Stettin which had to slow down in order to let them pass. IV Scouting Group became disorganized and soon after, was caught by the British 2nd Light Cruiser Squadron. A fight started, soon joined by Hamburg, Elbing, and Rostock. Stettin was hit twice and soon set on fire, her steam pipe pierced, engulfing her in smoke and disabling her spotting abilities; This foiled the captain’s attempt to launch torpedoes. HMS Southampton was hit by Stettin also during the fight, but Frauenlob was sunk. München was the only cruiser close to Stettin until they were both engaged by accident by the G11, V1, and V3 at around 23:55. By 04:00 on 1 June, the German fleet was back to Horns Reef, close to to port. Stettin had 8 killed, 28 wounded, her superstrctures damaged by splinters and burnt. She fired 81 rounds oat Jutland. Unfortunately the battle was the last serious engagement for a fleet mostly inactive, leaving U-Boats a free hand.

In 1917, Stettin left front line service, keeping a smaller crew as a training ship, for the U-boat school until the end of the war. The Treaty of Versailles had her listed to be surrendered and stricken on 5 November 1919, attributed to Great Britain as a war prize in September 1920 (“T”), sold to shipbreakers in Copenhagen, BU 1921–1923.

Resources

Books

Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships, 1906–1921.

Bennett, Geoffrey (2005). Naval Battles of the First World War. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military Classics.

Campbell, John (1998). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. London: Conway Maritime Press.

Farwell, Byron (1989). The Great War in Africa, 1914–1918. New York: Norton

Gray, J.A.C. (1960). Amerika Samoa, A History of American Samoa and its United States Naval Administration.

Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. I: Major Surface Vessels. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press.

Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press.

Herwig, Holger (1980). “Luxury” Fleet: The Imperial German Navy 1888–1918. Amherst: Humanity Books.

Hoyt, Edwin P. (1969). The Germans Who Never Lost. London: Frewin. ISBN 0-09-096400-4.

Nottelmann, Dirk (2020). “The Development of the Small Cruiser in the Imperial German Navy”. In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2020.

Staff, Gary (2011). Battle on the Seven Seas. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Maritime.

Tarrant, V. E. (1995). Jutland: The German Perspective. London: Cassell Military Paperbacks.

Dodson, Aidan; Cant, Serena (2020). Spoils of War: The Fate of Enemy Fleets after the Two World Wars. Barnsley: Seaforth Publishing.1.

Koop, Gerhard & Schmolke, Klaus-Peter (2004). Kleine Kreuzer 1903–1918: Bremen bis Cöln-Klasse. München: Bernard & Graefe Verlag.

Sites

world-war.co.uk

navypedia.org

naval-history.net/WW1Battle1507KonigsbergAction

alchetron.com/

encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net

worldnavalships.com

historyofwar.org

dreadnoughtproject.org

cc photos

wrecksite.eu

wiki

3D models

On turbosquid

Blueridge model 1/700

Arno 1:700 Emden (for conversions)

ww1 german navy models Kombrig 1:700

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign