HMS Cressy, Hogue, Aboukir, Sutlej, Bacchante, Euryalus (1899)

HMS Cressy, Hogue, Aboukir, Sutlej, Bacchante, Euryalus (1899)WW1 RN Cruisers

Blake class | Edgar class | Powerful class | Diadem class | Cressy class | Drake class | Monmouth class | Devonshire class | Duke of Edinburgh class | Warrior class | Minotaur classIris class | Leander class | Mersey class | Marathon class | Apollo class | Astraea class | Eclipse class | Arrogant class | Highflyer class

Pearl class | Pelorus class | Gem class | Forward class | Blonde class | Active class | Bristol class | Weymouth class | Chatham class | Birmingham class | Birkenhead class | Arethusa class | Caroline class | Calliope class | Cambrian class | Centaur class | Caledon class | Ceres class | Carlisle class | Danae class | Cavendish class | Emerald class

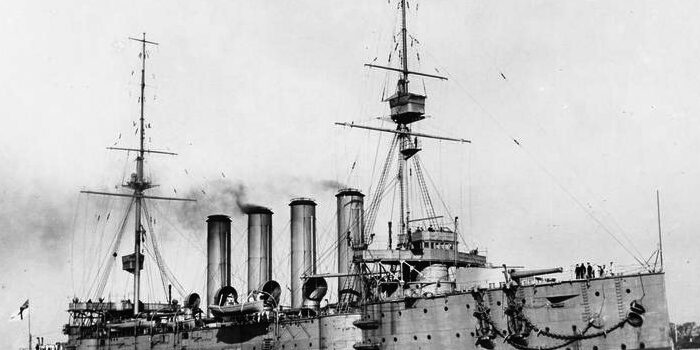

The Cressy-class cruisers were a group of six armored cruisers built for the Royal Navy in the early 1900s. They were incremental improvements over the previous Diadem class, criticised for their considerable downgrade in armament. The Cressy class had two 9.2-inch main guns on a large displacement, better armour, notably a proper belt, all thanks to a 1,000 ton increase in displacement, and they were praised to be stable, apart pitching in moderate weather. They were a bit faster but had the same silhouette overall. They served in Home waters, Mediterranean and Far East and famously in 1914 Cressy, Aboukir, Hogue, Bacchante and Euryalus formed the 7th Cruiser Squadron, crew by inexperienced reservists and called the “Live Bait Squadron”. Indeed Cressy, Hogue and Aboukir were sunk in on 22 September 1914 by U-9 near the Dutch coast. Believing this was a mine or accident, the two other came to assist and were sunk in turn. This event changed surface warfare for ever, making clear to all that the submarine threat was real. The surviving Sutlej, Bacchante and Euryalus were quickly sent to the Mediterranean and far east, ending their career in 1920-21. #ww1 #submarinewarfare #u9 #ottoweddigen #hogue #cressy #aboukir #royalnavy #armouredcruiser #greatwar

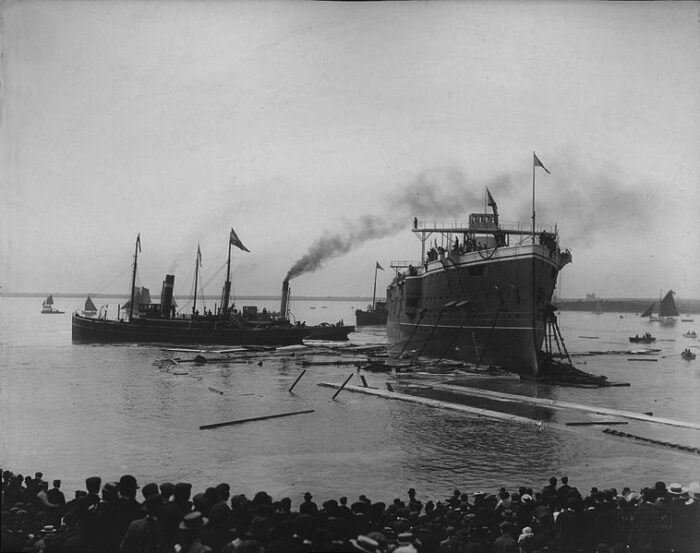

The launch of HMS Hogue in 1900, colorized by the author

As a general consideration, the Cressy class were indeed improved, valluable armoured cruisers, perfectly valid at the turn of the century. They showed the right way to approach the concept and led to the even larger Drake class. Slowly but surely this type of ships was closing on 14,000 tonnes, battleship territory. However, they emerged at a time torpedo boats were the concern, not submarine. As a result they were perfectly prepared to face incoming TBs with their Quick Firing light artillery but poorly defended against underwater attacks, with a limited compartimentation.

When entering service, they were sent in various assignments, Hogue and Sutlej in the channel, Aboukir and Bacchante in Gibraltar, Cressy in Hong Kong, Euryalus in Australia. The latter in 1904 had a troublesome machinery which required care and repairs until she was fully operational.

The launch of HMS Euryalus

Gradually as tension with Germany grew, they returned to the Home Fleet, all there in 1914. HMS Aboukir was in reserve, recommissioned with a crew of reservists and sent to patrol South of the North Sea, for the famous Force C, known as the “14 powerful”. She was torpedoed by U9 manned by Otto Weddingen on September 4, 1914 and sank with almost all her crew followed by HMS Cressy which prewar was in the North America and the East Indies stations but also part of Force C in 1914. She lost 560 men on this day. HMS Hogue also served in Force C but took part in the Battle of Heligoland Bay. She towed the crippled HMS Arethusa back to the port. She suffered the same fate as Cressy and Aboukir in the hands of U9. This was a national disaster and wake-up call for all those in the RN that did not took submarines seriously. Plans for a serious approach to ASW started right after the loss was confirmed by German propaganda. Another sad result was that ASW interfered from then on with rescue operations, with tragic consequences.

HMS Bacchante served on the river Humber in 1914, was transferred as a Force C as flagship, took part in the Battle of Heligoland Bay, escorted convoys to Gibraltar, defended the Suez Canal, and took part in the Dardanelles Campaign in 1915. In 1916 she escorted convoys in the North Atlantic and collided with HMS Achilles in the Irish Sea in 1917. She ended the war at Gibraltar as flagship, was in reserve in Chatham, sold and BU 1920. HMS Euryalus was also in Force C, escorted convoys to Gibraltar, defended Suez, Smyrna and the was at the Dardanelles. She supported the Arab revolt in the Red Sea, and served in the East Indies, ending her career in Hong Kong, back home to be sold for BU. HMS Sutlej in 1914 was in the 9th squadron operating off Ireland from 1915 to 1916. She operated later at Santa Cruz, then the Home Fleet with the 9th squadron until placed in reserve at Rosyth from 1917, sold for BU in 1919

Design Development

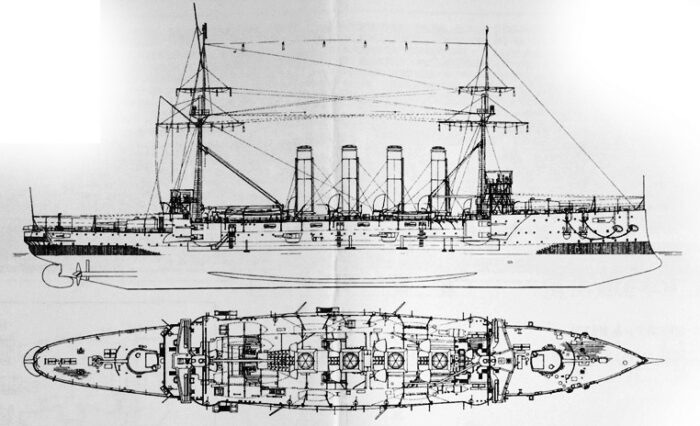

2 views from Kombrig. The whole set of original plans had been privatized, on sale in a book.

Six large armoured cruisers were ordered in 1898, as an improvement of the previous Diadems, with more significant protection, and more powerful machinery to compensate, possibly gain speed and with a reinforced armament going back to the 1890s Powerful standards. The greatest change was the adoption of Krupp cemented armour (CM) for belt armor, thinner and lighter yet stronger and more flexible. The ammunition wells and bunkers were also armored, the internal “citadel” was reinforced. The heavy turrets had hydraulic bearings and were steerable at any angle while allowing reloading to gain in rate of fire, another considerable improvement.

These ships had a longer silhouette but a general size still corresponding to that of the Diadem, and yet their hull was fuller, with 1000 tons more displacement, mostly improvements in stability a better stern profile for greater agility. They were also good steamers, surpassing their expected contract speed on trials. On the other hand, ASW protection was not better than the previous design. Separation between machinery rooms was minimal as well as compartmentation below the waterline armour belt. This internal protection, against a 21 inches 300 kgs warhead was just paper thin and internal layers not able to cope with flooding.

Hull and general design

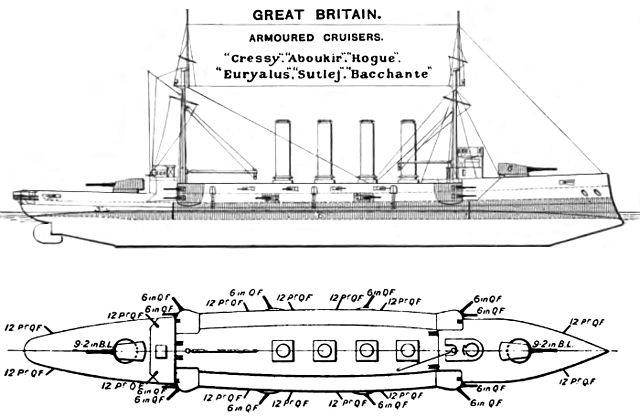

Cressy class diagrams Brasseys 1906

The Cressy class displaced about 12,000 tonnes. The exact values are still foggy to this day.

The hull had finer lines forward which was beneficial to top speed but also increased pitching. Of course the ram bow was a constant feature.

Protection

The game changer was their brand new 6-inches or 152mm Krupp steel belt. It was 230 ft (70.4m long) by 1.6 ft (0.5 meters) high, extending from the main deck to 5 ft (1.5 meters) below the waterline. This belt was enclosed at both ends by 5 inches (127 mm) bulkheads, extending to the bow by a 2 inches (51 mm) armour strake. So these ships had a citadel.

The protective deck compared to the previous Diadem class however was reduced in thickness to 1.5 inches (38 mm) but increased to 2,5 inches (64 mm) abaft the belt. There was an additional strake of armour of 3 inches (76 mm) over the steering gear, as well as over main deck from the after bulkhead and to the stem, tapered dow to 1 inch (25 mm) thick.

There were armoured tubes surrounding the ammunition hoists up to the 10 inches (234 mm) main gun barbettes.

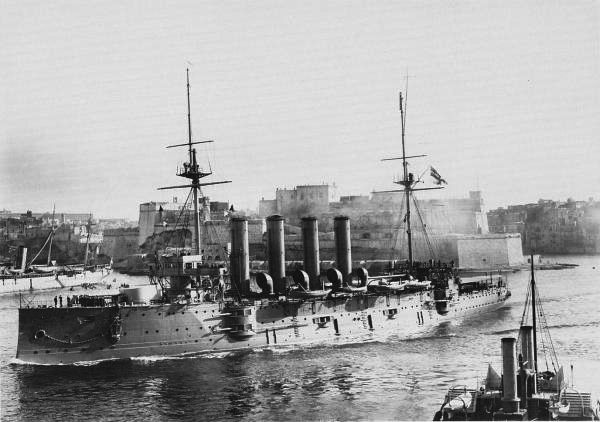

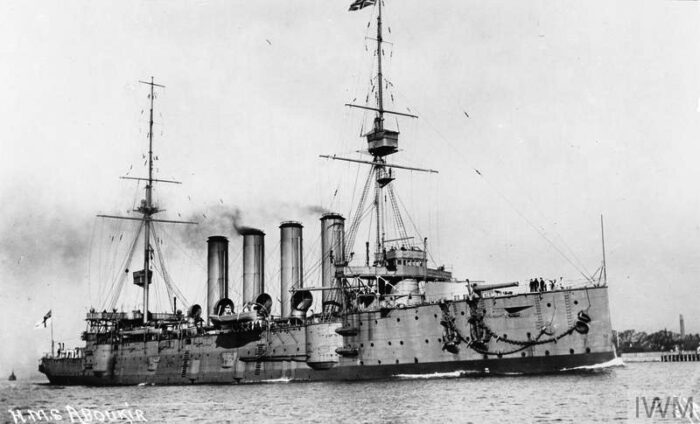

HMS Aboukir in Malta

The ammo tubes of the casemate guns and hoists were considered behind the side armour and left unprotected however.

The thickest, best protected aprt of the ship was the conning tower, as usual used as officers combat backup bridge under fire. For this, she had walls 12 inches thick (305 mm) wich was supposed to withstand battleship caliber hits. As customary, armoured cruisers were seen as potential battleline complement, in addition to their oversas stations duties.

Powerplant

The Cressy class had a better powerplant. Still two shaft propellers, driven by two 4-cylinders vertical triple expansion steam engines. Thet were fed by no less than thirty Belleville boilers for a grand total of 21,000 ihp (16,000 kW), to compared the Diadems had between 16,500 hp and 18,000 hp (13,000 kW). Contracted speed was 20 knots just like the Diadems, however on trials, they all exceeded that designed speed. Cressy was the slowest still ar 20.7kts and Hogue reached 22.06kts based on 21,432 ihp. As for range, they carried 1,600 tons of coal in normal load, for an endurance of 2,610 nautical miles at 20 knots.

Armament

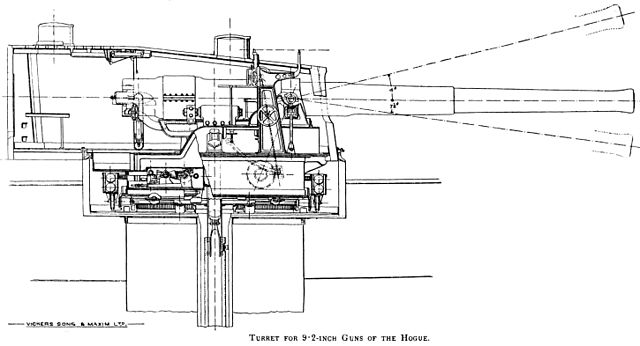

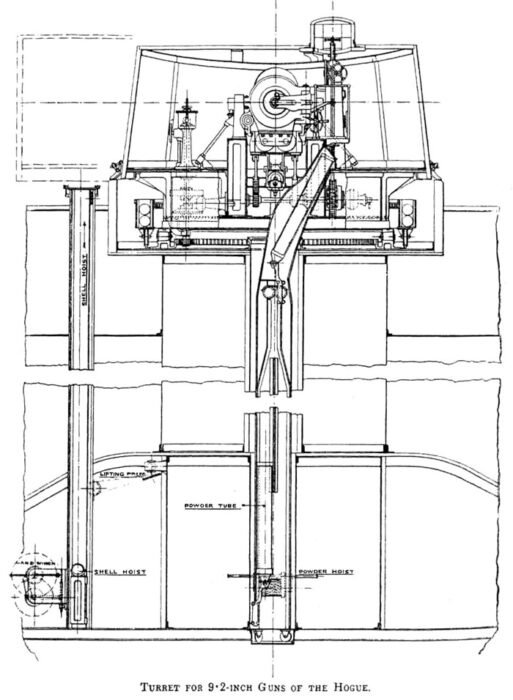

Breech-loading 9.2 inches turret of the Cressy, right elevation

The Cressy class signalled a return to large naval guns, with the standard medium battery of single QF 6-inch (152 mm) guns from sixteen (on the Diadems) down to twelve, but compensated by the addition of two main single 9.2 in (234 mm) guns in turrets fore and aft. This was rounded by a relative diminution of light armament, twelve single 12 pounder (3 in (76 mm)) guns instead of sixteen (Diadems) and three single 3 pdr (47-mm) guns as before, but it seems they did not carried extra Maxim machine guns. They also had underwater torpedo tubes.

BL 9.2-inch Mk IX – X naval gun

Breech-loading 9.2 inches turret of the Cressy, rear elevation

These Mk IX and Mk X guns were breech loading 9.2-inch (234 mm) 46.7 calibre models service from 1899 to the 1950s, both used as naval and coast defence guns with the longest and most varied career of any British heavy ordnance. They equipped notably the Drake-class, Duke of Edinburgh-class, Warrior-class armoured cruisers, King Edward VII-class battleships and M15-class monitors. But also the Pisa class (Italy) and Giorgios Averoff, the Greek flagship for decades.

Mk IX specs: 27 tons barrel & breech, 35 ft 10 in (10.922 m). Used a Welin interrupted screw for 3 rpm on average.

Shell: 380 lb (170 kg) exact diameter 233.7 mm at 2,643 ft/s (806 m/s)

Elevation was from -20° to 15° on Mark V Barbette mount and 360° for a range of 29,200 yd (26,700 m).

6 inches BL Mk VII (152 mm)

This gun was introduced on the Formidable-class battleships of 1898 and ended as new standard secondary on capital ships, and primary on cruisers, monitors, and smaller ships. They still served in World War II, but with heavy charges for more range and speed with the Mk VIII modified with the breech opened to the left instead of to the right. HMS Rawalpindi had these when facing Scharnhorst and Gneisenau in November 1939 but also HMS Jervis Bay against Admiral Scheer.

On the Cressy class, they were located in the same two-storey casemates fore and aft plus two on the lower battery level, just above the belt. There were recessed fore and aft on the forecastle and pop for a full forward or aft arc of fire.

Specs:

16,875 lb (7,654 kg) gun & breech, 279.2 inches (7.09 m) long or 269.5 inches (6.85 m) (44.9 cal) barrel

Welin interrupted screw for 8 rpm, Recoil 16.5 in (419 mm), manned by 9.

Shell: 100 lb (45 kg) 152 mm mv 2,525 ft/s (770 m/s)

Range 14,600 yd (13,400 m) with Lyddite 13 lb, Amatol 8 lb 14 oz or Shrapnel 874 balls@27/lb

12 pounder (76 mm)/40 12cwt QF Mk I

A widely produced, exported and licenced model across the globe. Designed in the 1890s, operational from 1894, this was the go-to QF gun to deal with Torpedo Boats.

They were located on the Cressy class in the upper, open battery deck, five in opening behind tall bulwark only protected against light shrapnel. The remainder four were in the lower bridge decks and in four small hull casemates fore and aft.

Specs: Separate-loading QF 7.62 cm, single-motion screw for 15 rpm

Muzzle velocity: 2,210 ft/s (670 m/s), range 11,750 yd (10,740 m) at 40° elevation.

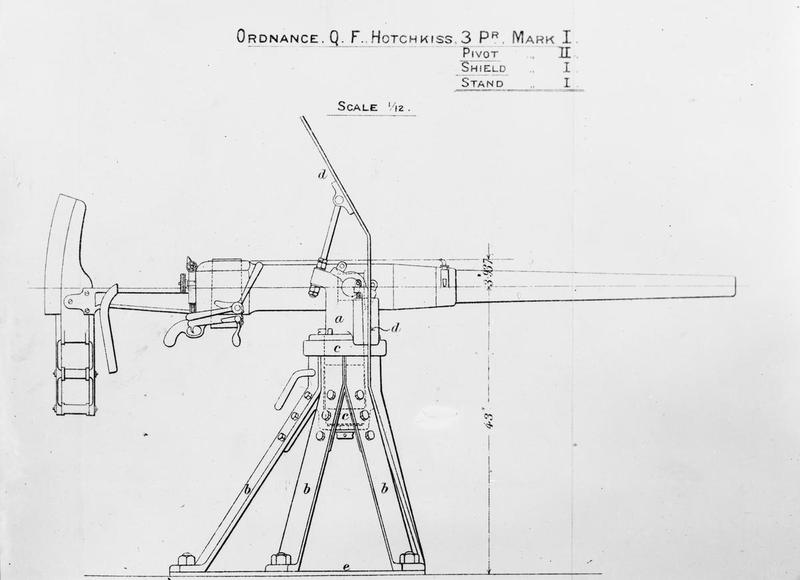

3 pounder (1.9 in/ 47 mm)/40 3pdr Hotchkiss Mk I

The Hotchkiss classic 1880s ordnance, one-man, QF anti-torpedo caliber. These were located in the upper bridge decks.

Specs:

240 kg (530 lb), 2 m (6 ft 7 in) barrel 1.8 m (5 ft 11 in) 40 caliber

Shell: Fixed QF 47 × 376 mm R, 3 kg (6.6 lb) full, 1.5 kg (3.3 lb) round, mv 571 m/s (1,870 ft/s)

Vertical sliding-wedge for 30 rpm, max range 5.9 km (3.7 mi) at +20°.

Torpedo Tubes

Two, fixed, underwater on each beam. Whitehead Mark I model 450 mm (18 inches) by default. They were located under the forward bridge.

Author’s profile of hms cressy in 1914.

⚙ specifications |

|

| Displacement | Approximately 12,000 tons |

| Dimensions | 472 x 69 x 26 feet (144 x 21 x 8 m) |

| Propulsion | 2× shafts VTE steam engines, 30 Belleville boilers, 21,000 ihp (16,000 kW) |

| Speed | 21 knots |

| Range | |

| Armament | 2× 9.2-inch Mk X, 12× 6-in Mk VII, 12× 12-pdr, 3× 3-pdr, 2 × 18-in TT (sub) |

| Protection | Belt 6 in (152 mm), Deck 2 in (51 mm), CT 12 in (305 mm), Turrets: 6 in (152 mm) |

| Crew | 760 officers and ratings |

The Cressy in service

HMS Cressy

HMS Cressy

HMS Cressy was laid down by Fairfield Shipbuilding, Govan, Scotland on 12 October 1898, launched on 4 December 1899 and after sea trials passed into the Portsmouth reserve on 24 May 1901 before being commissioned on the China Station on 28 May 1901 with a departure delayed for months when her steering gear broke down. She departed in October 1901 via Colombo on 7 November, Singapore on 16 November and later assigned to the North America and West Indies Station 1907-1909 and reserve back home.

She was assigned to the 7th Cruiser Squadron after August 1914, tasked with patrolling the “Broad Fourteens” North Sea with the Harwich force protecting the eastern Channel. She missed the Battle of Heligoland Bight as part of Cruiser Force ‘C’ in reserve off the Dutch coast. Rear Admiral Arthur Christian ordered her to carry 165 unwounded German survivors from Harwich Force, escorted by Bacchante, to the Nore.

On the fateful morning of 22 September, Cressy and her sisters Aboukir and Hogue patrolled without escorting destroyers (they took shelter from bad weather) in line abreast some 2,000 yards (1,800 m) apart at 10 knots for possible sights of smoke plumes in the distances. That’s what their lookouts expected in their spotting tops. The weather improved, Tyrwhitt was en route to reinforce them with his destroyers accordingly.

U-9 under Kapitänleutnant Otto Weddigen meanwhile was ordered to attack British transports at Ostend but weathered the storm submerged. When surfacing he spotted the British cruisers and approached to attack, submerging to periscopic depht. She fired one torpedo at 06:20 at Aboukir, hitting her starboard side. Naturally her captan believed this was a mine and ordered the other two to watch for some, close and transfer his wounded men. Aboukir however capsized at 06:55 despite counterflooding.

As Hogue approached, captain Wilmot Nicholson, realized it could be a submarine attack and signaled Cressy to look for a periscope while still closing at Aboukir. Her crew threw overboard anything that would float for survivors. She stopped, lowered her boats when hit by two torpedoes at 06:55. Just at the same time, the trim imbalance after the launch of two torpedoes caused U-9 to rose to the surface. Hogue’s gunners opened fire but faled to hit her as she managed to submerge again. Hogue capsized in ten minutes at 07:15.

Cressy spotted U-9 and attempted to ram her before she made her dive, and resumed her rescue efforts. She too, was torpedoed at 07:20, coming from U9 stern tubes, one hit. U-9 h then turned aroudnd to present her bow’s last torpedo, fired at 550 yards (500 m) at 07:30, which hit Cressy’s port side. Boilers exploded, scalding men around. She then took on a heavy list as flooding was catastrophic. She capsized and disappeared at 07:55. This happened close enough to the Dutch shore for many ships to arrive and rescue survivors at 08:30, the British trawlers jopined in and at last, Tyrwhitt and his destroyers at 10:45. U9 tok the lives of 1,397, but 837 men were rescued. Cressy lost 560. In 1954 her remains were granted to the Dutch for salvage which started on 2011.

HMS Hogue

HMS Hogue

Hogue (after the 1692 Battle of La Hogue) was laid down on 14 July 1898 at Vickers, Sons & Maxim (Barrow-in-Furness) launched on 13 August 1900 and fitted out for completion at Plymouth by September 1901, sea trials in December and fully commissioned at Devonport, 19 November 1902. She was assigned to the Channel Squadron and on 11 March 1904 collided with the merchant ship SS Meurthe off Europa Point. She was reassigned to the China Station and in 1905 became the boys’ training ship, 4th Cruiser Squadron, North American/West Indies Station. She was placed ib reserve at Devonport, 1908, then Third Fleet at the Nore 1909, but on 26 November 1909 a coal bunker explosion killed 2. She was refitted at Chatham 1912–13, assigned to the 7th Cruiser Squadron in 1914.

Like her sisters she protected the “Broad Fourteens” in the North Sea and Harwich. Next she was with Cruiser Force ‘C’, Dutch coast and she towed the crippled Arethusa (Tyrwhitt’s flagship) back to port. On 22 September she sortied with Aboukir and Cressy without escorting destroyers. After Aboukir was hit by a torpedo she was the first to close in to taken over her crew when Captain Wilmot Nicholson realized this was a submarine attack, signalling Cressy to look for a periscope, but she was hit by two torpedoes at 06:55 and capsized in ten minutes, sink at 07:15. Survivors started to be picked up from 08:30, joined by trawlers at 10:45. She lost 377 men that day. Her remains were scrapped in 2011.

HMS Aboukir

HMS Aboukir

Aboukir was laid down at Fairfield on 9 November 1898, launched on 16 May 1900, was fitted out at Portsmouth from March 1901, commissioned on 3 April 1902 and assigned to the Mediterranean Fleet, leaving UK in May for Malta. She made two deployments here in 1902–1905 and 1907–1912 and by September 1902 visited Greek waters for combined maneuvers, with landing at Nauplia and Argostoli and escorting the damaged HMS Hood to Gibraltar in October. She was placed in reserve back home in 1912 but in August 1914, reassigned to the 7th Cruiser Squadron with reservists on board, patrolling the Broad Fourteens and later in Cruiser Force ‘C’, Dutch coast. 22 September she patrolled Dutch waters with her sisters Cressy and Hogue when caught by SM U-9 coming from Ostend. She fired one torpedo at 06:20 at Aboukir, hitting her port side. Captain John Drummond thought this was a mine, ordered the other two to come to pick up his wounded men. He was soon informed of the proportions taken by the flooding, that could not be stopped. He ordered a massive counterflooding of compartments on the opposite side but to no avail. She quickly listed and capsized at 06:55, before he had even time to order abandon ship. Only one boat was available, the others being smashed or could not be lowered as winches had no power. Hogue approached and closed to pick up men when she was hit by two torpedoes herself. Soon Cressy, albeit informed of a possible submarine, closed in to pick up men from both when hit herselfn sinking quickly later. Aboukir lost 527 men, the heaviest tally.

Her remains were scrapped in 2011.

HMS Sutlej

HMS Sutlej

USS Sutlej was named agyer battles in First Anglo-Sikh War. She was laid down at John Brown, Clydebank on 15 August 1898, launched on 18 November 1899, commissioned at Chatham on 6 May 1902 under Captain Paul Bush, replacing HMS Diadem in the Channel Squadron by late July. She was seen at the Spithead fleet reviewt on 16 August 1902 for the coronation of King Edward VII and cruised to the Aegean with the Channel Squadron for combined manoeuvres.By October 1902 she escorted HMS Hood from Gibraltar to Chatham. Next she was at the China Station until May 1906, became a boys’ training ship at the North America/West Indies Station was and back home in 1909 as flagship, 3rd fleet reserve until 1910. While off Berehaven in Ireland on 15 July a boiler explosion killed 4.

In 1914 she joined the 9th Cruiser Squadron for convoy escort duties down to the Spanish coast and then the 11th Cruiser Squadron in Ireland by February 1915, next the Azores in February 1916, 9th CS in September and ultimately paid off at Devonport on 4 May 1917 ot free crews, ending as accommodation ship. In January 1918 she was depot ship at Rosyth named “Crescent” and bac to “Sutlej” in 1919, decom. and sold for BU on 9 May 1921 to Thos. W. Ward, Belfast, then Preston, BU in 1924.

HMS Bacchante

HMS Bacchante

Bacchante (named after the female devotees of the Greek god Bacchus) was laid down at John Brown, Clydebank on 15 February 1899, launched on 21 February 1901. She had her gunnery trials at Chatham in October and sea trials by November 1902 under Captain Frederic Edward Errington Brock. She was assigned to the Mediterranean Fleet as flagship, releaving HMS Andromeda. On 20 December she was commanded by Captain Christopher Cradock and remained in the Mediterranean under until 1905, back home in reserve. In 1906 she joined the 3rd and later 6th Cruiser Squadrons. By January 1907 she was under command of William Ruck-Keene until October 1910 and operated in the Mediterranean under Rear Admiral Douglas Gamble, captain Reginald Tyrwhitt and Flag Lieutenant Bertram Ramsay, two famous names (as Cradock, the hero of Coronel). In 1912 she was in the 3rd Fleet and in August 1914 became flagship of the 7th Cruiser Squadron, patrolling the “Broad Fourteens” and at the time of the Battle of Heligoland on 28 August she was flagship of Rear Admiral Henry Campbell, Cruiser Force ‘C’, Dutch coast. After her sisters were sunk by U9 she was transferred to the 12th Cruiser Squadron, escort ships between England and Gibraltar by October.

Next with her sister Euryalus she was transferred to Egypt by late January 1915 , protecting the Suez Canal although against Turkish raids. She started her Dardanelles campaign, shelling Turkish defences. She covered the landing at Anzac Cove during the Battle of Gallipoli on 25 April, shelling Gaba Tepe, and again provided fire support near Anzac Cove for several months notably the 3rd attack on Anzac Cove on 19 May. On 28 May she entered with HMS Kennet Bodrum harbour to sink several Turkish vessels here. In August she shelled Turkish troops during the Battle of Lone Pine (6 August) and the Battle of Chunuk Bair (7–9 August) but went back to Egypt during the evacuation of Gallipoli in December. Her former captain, Algernon Boyle remained behind at Anzac Cove. By Late 1916 she returned home. Later on escort, she was damaged in a collision with the armoured cruiser Achilles in the Irish Sea, on February 1917. She was flagship of the 9th Cruiser Squadron at Sierra Leone, from April 1917 to November 1918. Afterwards she was paid off at Chatham by April 1919, sold for BU 1 July 1920.

HMS Euryalus

HMS Euryalus

Named after the Greek hero Euryalus, she was laid down on 18 July 1899 at Vickers, launched 20 May 1901 and while completing on 11 June 1901, a major fire at Ramsden dock Barrow badly damaged her teak wood sheathing took fire and required repairs. Her completion was delayed futher when as before she could be towed to Cammell Laird, Birkenhead, she slipped off the support blocks still in drydock, severely damaging her hull. This was not over. On sea trials on 27 June 1903, she collided in Devonport with the fleet tug HMS Traveller. The latter sank. Euryalus was was completed on 5 January 1904, last of her class. She was assigned as flagship of the Australia Station and back home in 1905 was in reserve, then sent to the North America and West Indies Station in 1906, a training ship attached to the 4th Cruiser Squadron, then reserve 3rd Fleet from 1909 back home, until 1914. She was in the 7th Cruiser Squadron, patrolling the “Broad Fourteens” of the North Sea with the Harwhich force at the eastern end of the Channel to protect this flank of the supply route to France. On 10 August, she became flagship, Rear-Admiral Arthur Christian, Southern Force, eastern end of the Channel. Sh did not took part in the Battle of Heligoland Bight on 28 August, being off the Dutch coast.

On 20 September Euryalus sailed with Aboukir, Cressy and Hogue in the Broad Fourteen but to port to recoal. Two days later SM U-9 did its work. Her captain was so shock he asked to be relieved of his command. Bacchante was soon transferred to the 12th Cruiser Squadron, escorting ships between England and Gibraltar and with Euryalus, both transferred to Egypt by late January 1915, defending the Suez Canal. Under Rear-Admiral Richard Peirse, East Indies Station she became flagship for the operations in the Dardanelles and was operating in the north in March.

Next she became flagship of Rear Admiral Rosslyn Wemyss in April when the landing took place at Gallipoli. At the Cape Helles landings on 25 April, HMS Euryalus had herself three companies of the 1st Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers and a Royal Naval Division platoon to land and support on Beach ‘W’. She shelled Turkish positions later at the Second Battle of Krithia on 6 May. After a brief refit at Malta from 30 December 1915 to 20 January 1916 she returned to Egypt.

By 15 January 1916 Wemyss became CiC, East Indies, and made Euryalus his flagship again. In January-April 1917 she was refitted at Bombay. On 29 June she shelled the Yemeni town of Hodeida before an assault of the Royal Indian Marine. Rear Admiral Ernest Gaunt succeeded to Wemyss on 20 July and she was no longer flagship on 29 August. By early November four 6-inch, four 12-pdr were landed at Bombay. She sailed to Hong Kong, paid off on 20 December and conversed as a minelayer, unfinished when the war ended. Back home she ended at the Nore in April 1919 until sold for BU on 1 July 1920, done in Germany beginning by September 1922.

Sources

Specs Conway’s all the world fighting ships 1921-1947.

Links

dreadnoughtproject.org/

.naval-review.com/ cressy detailed-original builders plan review

navypedia.org brit_cr_cressy.htm

https://www.worldwar1.co.uk/armoured-cruiser/hms-cressy.html

The Cressy class on wikipedia

Video

Model Kits

modelwarships.com cressy_combrig.html

amazon.com Armoured-Cruiser-Cressy plans

On scalemates. Some choices at 1:700 by Kombrig.

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign