Revolutions in sciences and naval architecture

This period is often regarded as an era of perfecting ships of the line, making frigates and corvette a more substantial part of the fleets, and of pre-eminence and rivalry of the great European military and commercial empires, on the world’s stage.

Civilian ships are still generally of modest size, following coastal routes (apart the Indiamans) but with an exceptional diversification of forms resulting from the know-how of this seafaring people that are the Dutch. All these merchant ships have artillery on board. Some were in effect hybride warships, like the Dutch, English and French Indiamans, war and trade vessels or updated version of the Galleons. Global Empires went with considerable fleets and private companies became vital component of this strategy.

The era of great explorations was not over either, La Pérouse and Cook will push further back the boundaries of maps, still quite incomplete on the South Pacific. British-Dutch, then British and Dutch against the French marked the end of the eighteenth-century tall ships, derived from the galleons of the previous two centuries. Shipbuilding treaties tended to standardize more than ever shipbuilding, marking the transition between empiric traditions and baroque ornaments and cold mathematics concepts. A new, scientific approach to shipbuilding which was directly a result of the enlightenment. Faith in science, not in god or divine inspiration.

Brilliant engineers like Frederik af Chapman are cold typologists, who succeed to the old-time brilliance of the sculptors of the previous century. The ship of the line is rationalized, approaching pure functionality, an evolution which slowed down until 1850.

One can say that in the matter, these last great classical sailship battles would take place after the French revolution, in 1805 to Aboukir and Trafalgar, and by extension, at Navarin in 1827. But for the world’s culture, 1805 Trafalgar and Aboukir are the last major naval battles of the line fought by the greatest fleets of their time. The British, winning the seven-years war (some says the first true world war), and later the perile of Revolutionary France and Napoleon, securing a “pax Britannica” which endured until the end of the XIX the century, and the French and Spanish fleets, on the decline while the Dutch were just a souvenir.

Northern Europe Merchant Ships

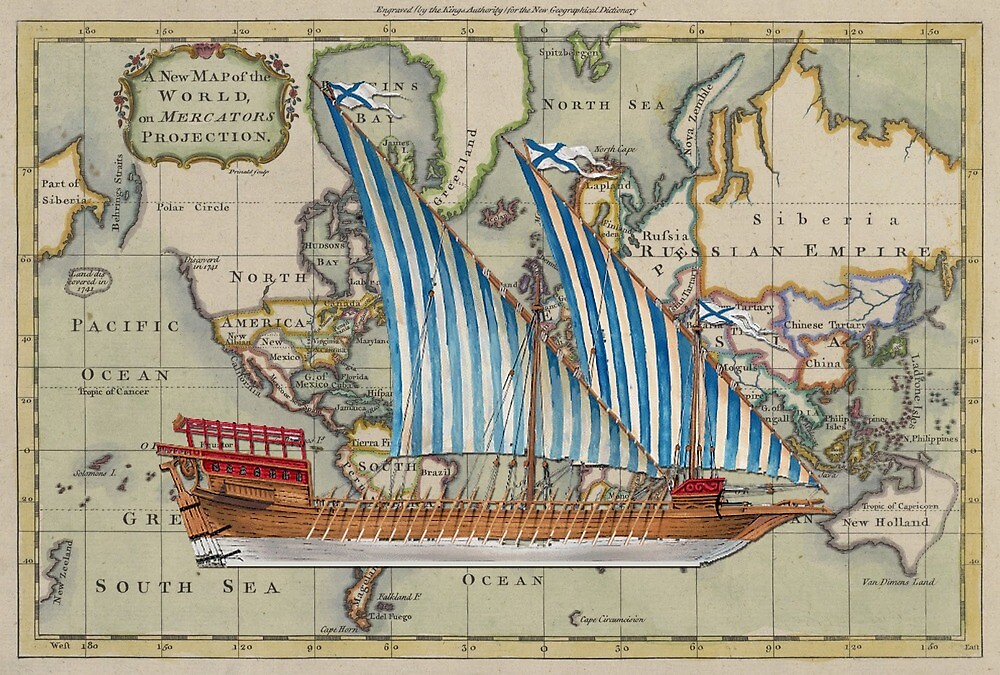

Chat (Kat)

The Dutch “Kat” is one of the most famous cargo ship of that enlightenment era, practising deep sea shipping as cabotage in northern Europe.

If in the seventeenth century Holland fought incessant wars against Great Britain, the low countries gradually lost its supremacy over world maritime trade in the next. However the creative genius of its engineers and craftsmen still made the reputation of its building sites. Originally the creators of a large number of European cargo ships, the Dutch invented the “Cat”, “Kat” originally. This term appeared in the Middle Ages to designate an intermediary between the nave and the galley, often a mixed ship of more than 200 rowers per board.

However this name was also applied to a totally different ship built by the Dutch to find a good compromise between the Flute and the Boyer. Rigged with two masts, she is a modest ship, devoted to the transport of coal or wood. However she evolved in the eighteenth century in a three-masted form. Her rounded transom, barge-like, and shallow draught gave way to a straight deck, and the Cat could be confused with other cargo ships including the Indiaman, but was strongly differentiated by its riverine capabilities and characteristics as well as low artillery embarked.

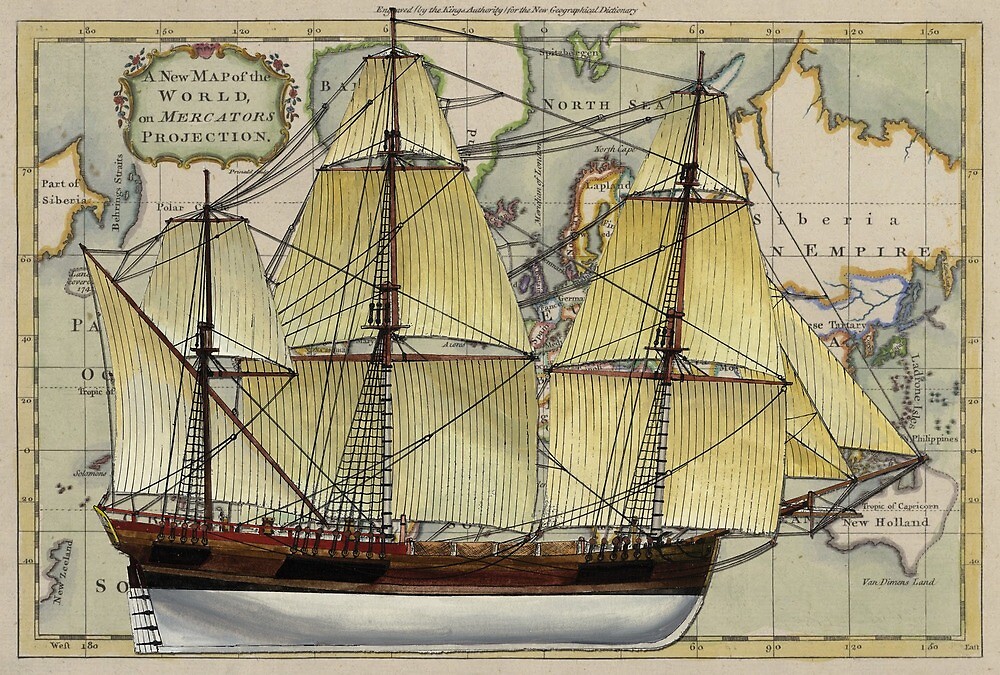

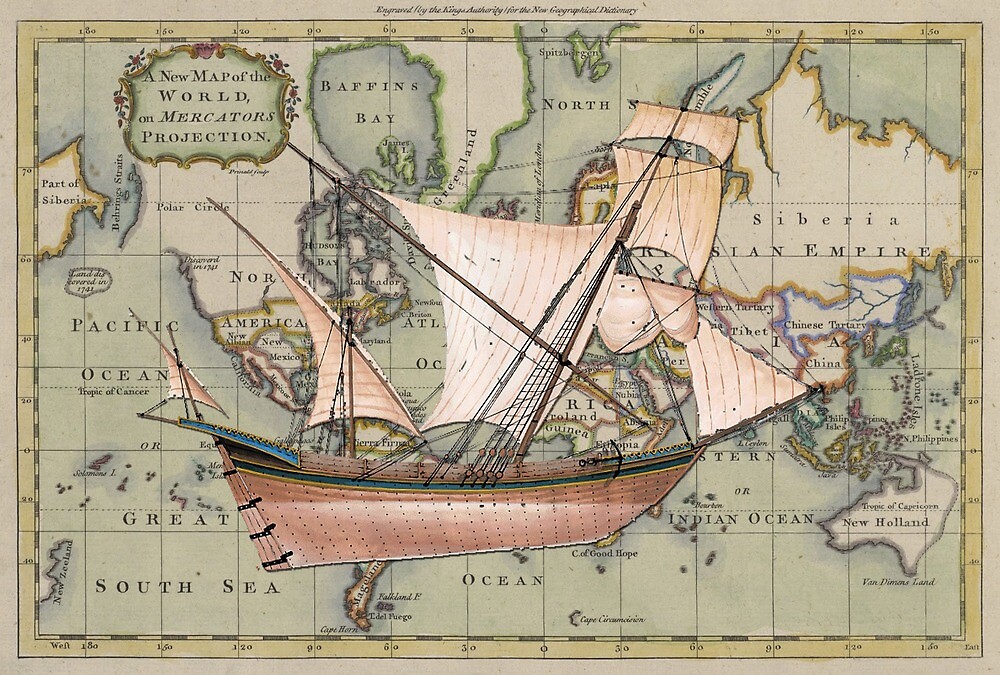

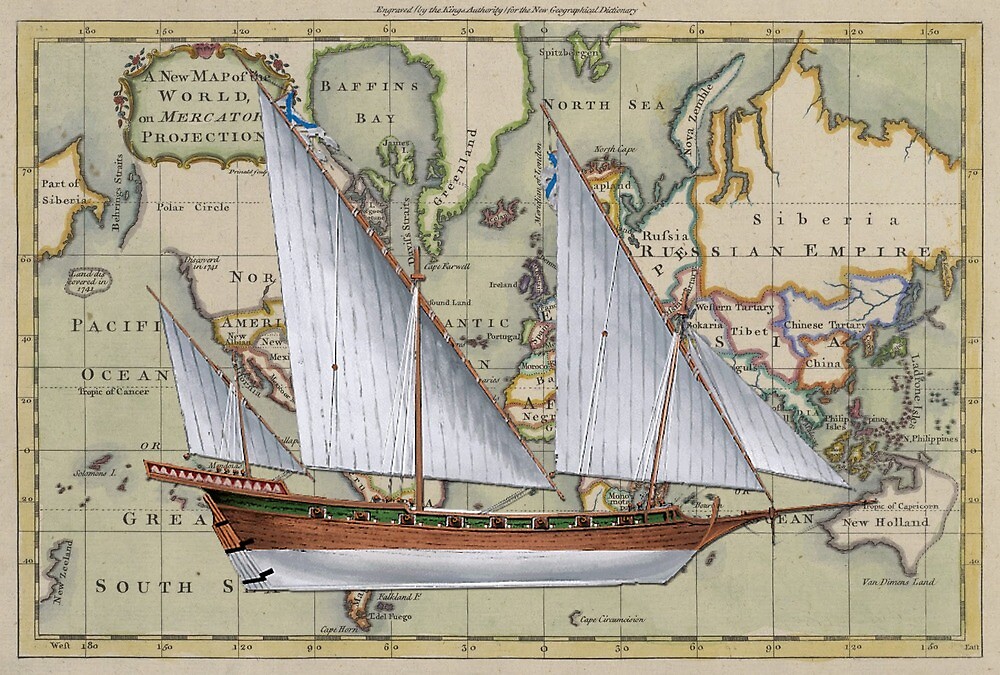

3-masted cargo barque

In the eighteenth century other merchant marines than the Dutch did not demerit. French and Great Britain merchant fleet recovered a bit of the market once held by the Dutch. This ship, shown here from 1750-70, is rigged in three-mast, even though many of the merchant ships of the time were satisfied with a Brick rig. Her crew was imposing. Pure cargo ship, her hull was particularly roomy, wide at the bow, the hull generally affecting almost a barge-like shape. Space had been made by removing artillery to further optimize the load, which indicated that the ship was limited to busy seaways in Europe, and probably had to be escorted. Very spartan aesthetically, her only concession to ornamentation lied in her transom.

https://web.archive.org/web/20170719105854/http://www.navistory.com/pages/renaissance–xvi-xviith.php

https://web.archive.org/web/20160516092549/http://www.navistory.com/pages/lumieres-xviiie.php

https://naval-encyclopedia.com/images/divers/renaissance/

Enlightment Era Warships

A reconstruction of English frigate.

The frigate HMS Rose was built in Hull in 1757. She was a “sixth rank” ship, barely superior to the corvettes of the same time. After a long service in the Channel and in the Caribbean, she was sent to the American thirteen Colonies in 1768. In 1774, under the command of James Wallace, she was sent to Rhode Island, in the Bay of Narragansett to put a stop to merchant traffic off Newport. As no American ship was at her level, she played her dissuasive role painstakingly.

From then on, Newport merchants petitioned their colonial legislature for a flotilla capable of attacking the British frigate. Financing the transformation of a merchant ship, they had a fast trading schooner chartered under the orders of John Paul Jones.

The latter became the very first ship of the future US Navy. Later, in May 1776, the colony of Rhode Island was shattered, followed two months later by the other colonies. During the war of independence that followed, the HMS Rose frigate participated in the New York landings, carrying out many raids and incursions far ahead of the Hudson. Wallace was made Chevalier by the crown. He pushed his action along the coast, recruiting civilian sailors for incorporation, capturing merchant ships, supplying garrisons, including Boston.

When the war reached a new level with the help of the French, turning in favor of the insurgents, the town of Savannah where the British frigate was anchored, was the object of a siege. The French fleet had planned a landing to take the city by sea, but the British had the frigate scuttled in the passage leading to the bay. As a result, the city supported the siege until the end of hostilities.

The Frigate was rebuilt in 1970 in Lunenberg, Nova Scotia under the direction of architect Phil Bolger, and has since been in constant representation. She made appearances in many films, sometimes repainted. For example, it was used for a full-size replica to be double the Surprise (Master and Commander).

Hemmemaa with latin rig (1781)

Hemmemaa was the first and most famous of the “frigates of the archipelago” with the Turumaa. Designed by famous naval architect Frederick af Chapman to replace classic sailing frigates, too massive with a draft too strong for the Baltic shoals, the type was the spearhead of the Swedish fleet during the Second Northern war. Baltic against Catherine of Russia. The latter, as in the past and its model Pierre de Grand, uses Latin architects and builds ships directly from the Mediterranean basin, which are well adapted to the conditions of the Baltic (see “Russians Galleys”).

Swedish ships were even more original. In order to reap the benefits of the galley that inflicted defeats on them during the first Baltic War, Chapman conceived a modernized and more rational version of the old Galeasses, the very one who had defeated the Turks in Lepanto 1571.

But the Galeass have powerful artillery but in return, a strong draft. Chapman wanted to create lighter ships. His solution was to design ships with a central battery, the rest of the bridge being occupied by banks of rowers. These frigates of the archipelago, however, have three men per bench offset, and 24 to 22 guns per side, for 40 or 38 oars. The second figures are given for the smaller Turumaa. The other main difference between these two types of ships is that the Turumaa was usually only square rigged, while the Hemmemaa was most often Latin rigged. Both had 3 masts, four counting the bowsprit.

These ships replaced traditional sailing frigates used by the Swedes so far. They were in operation in the heart of summer, with melting ice. Several battles marked the use of these ships during the Second Baltic War: In 1788, the Battle of Hoglund was an indecisive encounter. The Swedes were however forced to stop their offensive. In 1789, the same scenario was repeated, and the Swedes took refuge in their Karlskrona base. The Russians started a blockade. In August 1789, the first battle of Svenska Sund started, when a Swedish convoy stood in defense against a Russian attack and were sunk.

About thirty ships carrying troops were destroyed or captured, as well as eight ships. In June 1790, the Swedes tried to prevent the junction of the Kronstadt and reval fleets. They did not succeed, and the offensive turned to rout. Their ships took refuge in Vybord, where the Russians in numbers blocked them there.

A month later, the Swedish squadron will succeed in forcing the blockade, but at the cost of high losses: 7 ships and more than 20 small transports, the Russians on their side did loose 11 ships. The Swedes were in defensive position in front of Svenska Sund in July 1790. The Russian attack failed in front of the strength of the fortifications and turned into rout. The Swedes chased the fugitives and still managed to destroy many more ships. In total, this Russian defeat would cost 64 ships of all tonnages on the 140 total of the Russian fleet. Empress Catherine was obliged to sign peace…

Capped Lead Galley (1715)

During the first Baltic War, Peter the Great, founder of St. Petersburg, called on Italian engineers and architects to define his galleys, the ship most suited to the shoals of the Baltic which was to be the node of his clashes with Sweden. Three types of galleys were defined to constitute the Russian fleet: “standard” galleys, about 40 meters, directly inspired by the Genoese and Venetian models, also built in the Black Sea, with a swim of 27 oars per side and four men each, “a scaloccio”, which represented a total number of 216 men, three artillery pieces in chase, sometimes two in stern, and a company of marine riflemen. The largest galleys, as in the Mediterranean fleets, were divided between “patrons” and “admirals”. Thes were to command a detachment of galleys and were a little larger (46 to 50 meters, 30 to 36 oars as the illustration above), and five men per bench, as well as reinforced artillery.

The total width was around 9 meters. The above illustration shows five artillery pieces, four 4-pounders and a 24-pounder, as well as six side pieces in the quarterdeck and two 18-pounder at the sterns, as well as 14 culverins. The smaller 3-pounders on mobile mounts were located on the side rails. These galleys-admirals were supreme command units to lead a squadron, likely to bear the Tsar’s mark in person. They were 50 meters long and over, with a crew of 380 rowers distributed by five out of the 38 oars per side, and using a mixture of bombards and 24, 18 and 12 pounders.

This same type of galley was still in use during the Second Baltic War led by Sweden’s King Gustav III against Catherine of Russia. Rarely armed in comparison to their size, the great Russian galleys could not seriously worry the Swedish ships except for ramming, thanks to a speed of 7 knots, quite formidable in calm weather. These are the “half galleys”, xebecs and half-xebecs, and the famous Skampayevas who were the most effective.

French Bomb Galiot like the Salamandre (1715)

A French galiot, one of those which entered the composition of the fleet.

This type of very specific and specialized siege shipe is born from the punctual need to have a heavy artillery capable of overcoming terrestrial objectives, including coastal fortifications and Vauban-style citadels. Their curved mortars placed in a central housing of the deck could if necessary also serve in battle, firing heavy incendiary bombs.

The name “galiot” is derived from flat-bottomed vessels used by the Dutch. The rig also was specific with a large mast very far back to clear the range of the mortar. Their artillery was completed by small side guns.

Normandy Flambart of the XVIII-XIXe cent.

With her pansy air and auric rig, the Flambart has something of a “fishing coaster”. It was a Norman traditional ship, which is derived from the French term “flamber” in reference to the will-o’-the-wisps which sometimes clung during storms to the apple of the mast, also called St. Anselm fires, and which frightened superstitious sailors, as warning signs of disaster. This was a fast vessel for paddling (line or trawl) characterized by two masts, with the foresail leaning forward and the main mast rearward, very close.

They carried a horn sail and a foresail to the third, and a jib on the bowsprit. Saffron was small in size, so the maneuver was most often done in sailing. They fished by trawl and line, and occasionally by cabotage, since the eighteenth century. The Seine Bay shoals were also called flambarts in the same way. Flambart is also known as the Sailing Boat of the Bretons (from Britanny), carrying a large boom: The Dagou Jaguen is a small one.

Russian Half Galley during the battle of the Gulf of Bothnia in 1714.

If the great galleys inspired by the Genoese and Venetian models had some success, the models of galleys by far the most widespread in the Russian navy were the “half galleys”. Inspired by Mediterranean galiots and half-galleys, the latter simply presented themselves as shortened galleys, with fewer rowers (on average three men per bench, and from 18 to 25 oars per board, or a maximum of 150 rowers).

They had only two masts and large lateen sails. Their fellows seemed more important in proportion, and these ships had a modest artillery, limited to three pieces in chase, 6 and 18 pounders. But what seemed to be a weakness was counterbalanced by great manoeuvrability, which was lacking in larger models. With a maximum of 30 meters long by 5 wide, these half-galleys sneaked more easily and could interfere with the manoeuvrers of the opponent. They inspired a model of galley proper to Russia, even more modest, the famous Skampaveyas. The latter won many battles against the Swedes during the first Baltic War. The half galleys were still considered the spearhead of the navy of Catherine II of Russia in 1780.

Russian Xebec in 1789

Russian Half Xebec

It is unusual to see the racy silhouette of these typically Mediterranean hybrid ships, symbols so feared by the Westerners as immediately associated with barbary pirates who raided the southern coast of Europe and merchant ships at the beginning of the Renaissance. True thoroughbred, the elegant xebec was a derivative of the galley, with the difference that the oars had been removed in favor of a very consistent sail, Latin, then by evolution, mixed, entirely square alternately to a Latin sail.

Related to the Polacca, which is a modern evolution, but also to the smaller Tartanes, the Spanish Felucca, the Mistic and the Warbler, the Pinque, the Xebec (Sciabecco in Italian) remains one of the symbols of the Mediterranean. Continuing to draw on this heritage in order to try to adapt it to the Baltic Sea, closed sea a priori suitable for this kind of ships, Catherine of Russia, inspired by Peter the Great, called on Spanish builders to build a few dozen of these boats and half-xebecs to oppose the heavy Swedish ships during the second Baltic war in 1788-90.

The Russians were thus barely modified copies of these ships which were also built and used in the French navy. Their draft was weak, their hulls narrow but without making them an unstable ship, their masts short, not composed or “to pible” and light carrying large Latin sails on antennas completed by jibs on the “bowsprit”, or a partially square sail, with a Latin veil at the front, a light square in the middle and a brigantine aft.

The demi-xebec was a shortened version, with two masts instead of three, wearing a Latin sail at the front, a brigantine aft surmounted by a square topsail. All were also maneuvering to rowing in case of flat calm, very practical to move in the sandy shallows of the islands of the Gulf of Bothnia. The crew of these ranged from 200 to 240 men, the half-xebecs with less than 150 men on board. The latter, more agile, carried an artillery reduced to 8 pieces of iron or advantage, while the xebecs aligned as standard 24 guns. They had the advantage of more artillery than the galleys.

HMS Prince (1670)

This 1670 first-class ship of the line became the flagship of the Royal Navy fleet after the disappearance of the HMS Sovereign of the Seas. She carried about 96 guns (nominally 100) and was classified as a three-decker (3 complete artillery decks, one more open half deck). Black was at the time the most used color as the official livery of Royal Navy ships. The decoration however more sober than that of contemporary French ships of Louis XIV.

The HMS Prince was built by Phineas Pett the Younger, at Deptford Dockyard, and launched in 1670. During the Third Anglo-Dutch War she acted as a flagship for Lord Duke of York (later James II). She was found again in action during the Battle of Solebay (1672), right in the centre of the English center, attacked by the Dutch core led by Admiral Michiel de Ruyter. HMS Prince was heavily damaged by the De Zeven Provinciën in a two hours epic duel. Captain Sir John Cox was killed on board (head of the fleet as well). The Duke of York was forced to leave the board and raise his flag to HMS St Michael, under captain John Narborough.

HMS Prince was repaired and eventually completely rebuilt by Robert Lee at Chatham Dockyard in 1692, renamed HMS Royal William. During the War of the Grand Alliance she also fought at the Battle of Barfleur of 19 May 1692 against the French. HMS Prince was part of red squadron, flagship of Rear Admiral Sir Cloudesley Shovell, and first ship to break the French line.

She was rebuilt a second time by John Naish, Portsmouth in 1714, launched again on 3 September 1719 and renamed Royal Williams. However she saw no service and eventually was reduced to a 84-gun Second rate ship in 1756 (it is not precised if this was as a Razee). In 1757, she was part in an ill-fated expedition against Rochefort under admiral Sir Edward Hawke. But she forced Île-d’Aix’s garrison to surrender. The next year under Boscawen and Wolfe she attacked the French Fortress of Louisbourg in Nova Scotia, duelling with a French squadron. In 1758, she returned to Canada under Captain Hugh Pigot to for the campaign against Quebec. After the Battle of the Plains of Abraham and fall of the French capital of Nouvelle France, she was back to England with the body of General Wolfe. In 1760, HMS Royal William she became Admiral Boscawen’s flagship, heading the fleet in Quiberon Bay but was damaged after a severe gale, forced to return. But she was part later in the expedition against Belle Île in 1761, and patrolling the coast of Britanny. She fought also during the Seven Years’ War but was broken up in 1813. By that time she was 143 years old ! …

British Frigate 1680

https://web.archive.org/web/20170416153030/http://www.navistory.com/pages/the-enlightment/british-frigate-1680.php

Mediterranean Ships

Sakouleiva

Reconstitution of a Greek Sakouleiva

Known originally as the Saccoleva in Italian and Sacolève in French, but derived from Sakouleiva in its original Greek, she was a low tonnage decked vessel, a wide coaster (15 meters by 5 for the largest) with a curved bow, narrow saffron rudder, while the deck and the freeboard are so low and smoothed that it is necessary to raise a pavise to prevent the sea from invading the deck and hold. The Sakouleiva is a fast and large-capacity merchant ship for its size, widely used from the beginning of the 17th century, resulting from the synthesis of different types of Western and Arabic types, with quite unique features, such as the leaning front mast, jibs on a bowsprit, the combination of Latin and square sails, as well as a livarde (as the illustration above).

The serration patterns of the bow and stern are also recurrent features. During the eighteenth century, this type of ship became widespread with combinations of rigs from Bricks, schooners, and are sometimes called Kalandiccios or barges. The first Sakouleivas were small and fatty (8 meters by 3), and equipped with a single sail on livarde and a jib rigged on an outer spar, with one or two masts, the one of the back bearing a Latin sail. Other more important Sakouleivas, ranging from 10 to 12 meters to 4 ratio, wore two lug sails and were often called runners (“trikandiris”).

Late Galleys:

La Liberté, (‘Freedom’), reconstitution of a galley of Lake Geneva in the seventeenth century. Realized through a job reintegration project by jobseekers, the project, designed by Jean Pierre Hirt, was self-financed by the tourist receipts generated on the site and by the canton. It is currently a cruise ship equipped for navigations of several days and the only replica of a galley of this time and this size.

The post-renaissance galley, from the 17th to the end of the 18th century, has finally evolved little if not generated sailing and successful derivatives like the Xebecs, Polacres, Tartanes … The galère tardive from the beginning of the seventeenth century reached its characteristics and definitive forms, resulting from hundreds of years of empiricism for a typological genus dating back to the Bronze Age… The current galley was necessarily propelled by a single row of oars Manned by several men, generally 3 or 4, 5 to 7 for the largest, swimming called “a scaloccio”.

The Venetians were indeed the builders of reference galley in the Mediterranean, competing with the Genoese. Since the Crusades they dominated the maritime trade with the Orient. The commercial and military galleys had many points in common. Specific military variants were derived from the Byzantine Dromons, themselves from Liburnae of the Roman Empire. The Venetians created a type of galley derived heavy galley, Galeasses, which proved its effectiveness to Lepanto and drifted in Galion, itself ancestor of the ships of the XVII-XVIII centuries. That is to say, the galley has had a major impact on Western maritime history.

The great nations of that time, which had a façade in the Mediterranean, but also, and more surprisingly for the general public, in the Baltic and on Lake Geneva, all had galleys in the eighteenth century. We can mention Spain, Italy (the city-states and the Italian Kingdom), France, the Ottoman Empire, the Moorish and “Barbary” the Russians (in the Black Sea as in the Baltic), the Swedes, the Cantons Swiss…

The galley and even its derivative apparently more “marine” Galeazza of the great Armada were not suitable for navigation in the Atlantic and in the sleeve as evidenced by the defeat of the invincible Armada (more due to navigation on return only to the battle itself). In the Mediterranean they had reached by the end of the seventeenth century a kind of unsurpassable perfection in terms of shell shapes, fully drawn, dictated, by the empiricism of speed, and widely copied, as its organization of swimming, the wing, large and simple to brew, only its armament and equipment, excellent tactical compromise.

Unlike galeasses and derivatives, galleys could appear as under armed. But it was not so. In fact they could not align a large flank edge, but only hunting and possibly retreat. This artillery was therefore 3 to 7 heavy pieces, often of decreasing size, and scythes and other hand-held guns mounted on freeboard bases, especially at the level of the rear and front galleries, sketches of fellows serving as platforms.

The Venetian galley, the model copied later, is typical: It is low, its hull is narrow and finely drawn, it is very wide at the level of the talar (the double), a little like the modern aircraft carriers, with a wide central footbridge, which allows, like the ancient galleys Athenian, mass on the bridge many fighters, arquebusiers in the majority, which compensates for their relative lack of firepower. The chiourme is in the open air. We do not care much about its comfort in some marines, as in France where it is about convicts.

The spur has lost its traditional use and is now an ornament that also has a protective function of the bow, and a support and extension of the pointed bow, intangible characteristic. The hull at the front therefore has entries much finer than galleons and vessels, which explains its success. A sail alone, it is indeed in high winds more efficient and faster than a three-masted fully rigged as the Caraque or the Nave. Its classic Latin rig, which takes the crosswind, is also easier to rig despite its size, more versatile and efficient in all weathers. For heavy ships, the galleys serve as greyhounds of the seas. But the number of rowers required is a hindrance to their exploitation, hence the derivatives such as chébec and polacre.

Their typology was established between Galères usual (50 meters (47 hull alone), 255 rowers on 51 benches (one less on the port side to build the fougon, the kitchen on board), Patronnes (one rower more, or 5 or even 6, see the Dauphine), and La Réale, a giant galley of prestige, like the famous reed of Louis XIV, the latter with 7 oarsmen by rowing, 16 meters long and nearly 500 men on board was described as “extraordinary “Like the bosses, these giant galleys of nearly 70 meters had a symbolic and honorific value more than military.

But this perfection should not hide the fact that the galley had entered into a slow decadence at the beginning of the 17th century … Indeed, the galleon became a serious competitor. Almost as fast (at least for the first, from the galeas but much more veiled), they had a far superior firepower, a carriage and a versatility beyond measure, especially because of their ocean capabilities. However the galley retained its main advantage, that of passing the uncertain wind in closed seas like the Mediterranean.

The last actions of the galleys were the work of the Russians against the Ottomans in Chesma in 1770, the Russo-Swedish war of 1790 in the Baltic Sea where the famous “frigates of the archipelago” of Chapman, the seat of the Valetta by Napoleon and the defense of the Knights of Malta in 1798. They then became more prestigious and ceremonial ships, like the Venetian Bucintoro, losing all military value in the West. It is noted, however, that the Turkish fleet still had a dozen anchored in Istanbul in 1927

Réale de France

Louis XIV admiral galley of the French Mediterranean Fleet

The fleet of French galleys from the Louis XIV era reached its apogee with this ship. Formerly as important as the Venetian and Genoese fleets, the French Mediterranean galley force consisted of about a hundred ships, floating prisons, with a warlike role, gradually blunted since the appearance of the galleon.

Louis XIV was to be present on all fronts, as the larger, most populated, richest of the great powers of the time, it relied on Colbert’s ships for its Atlantic facade. The Soleil Royal, her admiral ship, was one of the most illustrious representatives, but in the Mediterranean the Reale of France was its equivalent.

The “Sun King” wanted his “mare nostrum”. To do this, a type of galley of high rank was created, the “Reale”, which remains one of the most sumptuous floating objects. With 33 and 34 oars on respective sides, for 6 or 7 rowers each, it had on board a total of about 600 rowers, including those kept “in reserve” in the lower deck.

There was in addition a musketeer guard of 100 men, about twenty gunners, fifty sailors, not counting officers and lackeys. Altogether, nearly 800 men found a place on this monster, more than 65 meters long by 12 meters wide (without rows). The reale carried six cannon stacked at the front, and two in its stern. It was rather a parade ship than a warship, lacking agility at sea.

Bucintoro

Boom

Felouque

Felucca of Provence fishing, in the eighteenth century.

Called modern French felucca (formerly falque), but known first under its name Arab fâluka, it is also known as Feluca, Falua, and Faluca respectively in Italy, Portugal and Spain who used it. The original ship, the felucca of the nile, is a derivative of the ancient Egyptian barges, especially those that carried the blocks of stone of the great monuments. It is therefore an offspring of a very old ship whose fundamentals have hardly changed, except that the offshore felucca has a much thinner and narrower hull, a sail and a saffron less imposing, but it remains in principle unbridged (if not in front). It is a very simple transport ship, rigged Latin (triangular) for the non-Arab versions and seti (quadrangular) for the others. The Faluka of the Nile is very different, it is related to the Gayassa, treated here. It will be the subject of an article in the middle-age section.

The “Western” Felucca are from coastal Arab feluccas, especially those used by Barbary pirates. It is as fast indeed as the chebec, more manageable, and also rowing. It can be hoisted to the ground easily because of its reduced size. A Provencal felucca (illustration) for example, hardly exceeds 7 meters. It is a large boat in the form of galleys, common to the oaks, tartans, polacres, and naturally the galleys. Its very rudimentary rig is easy to maneuver and the crew can be reduced to two men, see one for the one-part version, the most common among the Provencal feluccas.

The latter, however, rig a jib on the bowsprit. Although capable of facing the open sea, these boats were used for coastal transport, liaison, unloading and fishing. The trap fishery was its most famous use. She left memories (she began to slowly disappear in the early 20th century), and a local name in the var. The traps were more generally “fishing farms” granted by the King to a local lord, privileges and taxes in return for the treasure attached to it. Compelling for sailors, it was banned in 1851 but three remained in 1894.

The trap was also the fixed net (anchored to the bottom) used for this fishing, usually several were stretched between the boats that tightened the vise until catching the bluefin tuna hook in the few square meters of the “death chamber” “(matanza in Italian). This type of fishing was practiced already in the time of the Phoenicians, then the Greeks, and by extension the Greek colonists Phocaea (Marseille).

The Provencal term Madrago is of the same root as the terms matador, Baton and Matamore. Felucca was used to transport the nets, and eventually tuna on their return. The Corsican Felucca was quite close to the Provençal, except that the bow was higher than the stern and it has no guiber. The Sicilian Faluca is quite close to Corsica. Tunisians also practice this fishery, inherited from the Carthaginians during the summer migrations.

Baghla

Also called Baghla, or written Baggalah, this type of very classic Boutre was among the greatest. With two masts with a large airfoil, they were mainly heavy cargo ships (250-500 tons), with a western-style stern-sized quarter-deck, but some were used by Barbary pirates in the 18th century. Finer line, thanks to their large sails, they were quick. The one in the illustration below is an eighteenth-century pirate ship armed with 12 guns.

Mediterranean Allege (XVIIe-XIXe Cent.)

The Allege “lighter” but we say today “feeder” was generally a small cargo ship destined to partly unload large merchant ships anchored and ferry them to river towns. They have the role of current “feeders”, mini-container carriers whose utility was to transfer loads of large container ships, which draft was incompatible with the harbor shallows.

The model seen above is from Arles, detached in Toulon. It was specific to this city, with a hull derived from the Tartane, a single mast, 15 m long by 5 wide (ratio of 3/1, typical of cargo ships), the Allege had a shallow draft and a flat bottom, because it was intended to go up the Rhone. The sheer was rather pronounced, as well as the high “guibre” for the docking of a bowsprit which was a polacca, precursor sail to the foresail. The largest Latin lighters had a small square topsail above their mainmast.

The bowsprit was transformed in the 19th century into a “boute-hors” (simple spar sail) and the polacca was transformed into a kind of great Genoese. The strong wing was a speed insurance in the relatively open conditions of the interior. Arles stones and timber were two of the most common loads of these ships.

Dinghy

The Dinghy, before becoming the generic name of a small boat on board modern ships (akin to “youyou”), was one of the most widespread of the large Indian cargo ships. Also called Dhingi or Dingey, from “dingî” in Hindustani, it is a ship to bring Thoni closer, but the hull is smaller and lighter (no internal reinforcements), and decked but without forecastle.

Its rigging was complicated, mixing main and secondary masts, starboard bowsprit and removable port-side “tapecul”, foresail, livard sails, latine-setie and even marconi sails. The Dinghys originally sailed between Cuddalore and Bombay. Their shallow draft was offset by a large width, allowing them to anchor near beaches. They were fast, though with almost straight bow. Their average dimensions were 20 meters for 5.20 with 90 tons of payload. They were rather sober in decoration and bore only a small round figure at the head of the bow.

Zarook

https://web.archive.org/web/20170415080208/http://www.navistory.com/pages/the-enlightment/zarook.php

Lateen Pink

https://web.archive.org/web/20170415080133/http://www.navistory.com/pages/the-enlightment/pink.php

Lateen Pink

To Come (Complete List):

Galleys and oarships:

Late galleys (general)

The Lead galleys: La Dauphine

Royal Galleys: La Reale de France

State galleys: The Bucintoro

Russian galleys

The Skampaveya

The Russian half galleys

Turunmaa

Udenmaa

Pojammaa

Hemmemaa

The Swedish galleys

Other Mediterranean vessels:

The Barbary Xebec

The French Xebec: The Shark

The Spanish xebec: Frigate El Gamo

The Venetian Sciabecco

The Square Xebec > (plans from François-Edmond Pâris)

The French Polacre

The Tartane

The Mediterranean Pinnacle

The Felucca (Western)

The Tchektirme

The Skapho

The Sakouleiva

The Warbler

The sloop

The Topo

The Luzzu

The Patache

The Latin Allege

Northern Ships:

The Trade Pink

The three-masted Trade ship

The Dutch Kat

The Senau

The Hagboat

The Trade Frigate: HMS Bounty

The Brick

The Foncet

The Ketch

The Huker

The brigantine

The Xebec and Half-Xebec (Baltic)

The Shkoat

The Flambart

Warships:

The bomb galiot and Bombard: Salamander

The American frigate: USS Constitution (1797)

The light frigate: HMS Rose (1757)

The French Light Frigate: La Railleuse, 18 guns

The English Corvette: The Endeavor and James Cook’s Expeditions

The Dutch lineman: Delft 1783

The French Corvette: The Astrolabe and the expeditions of F.G Lapérouse

The Prame

The pirate brig

The brig of war: HMS Sysmondiet

The Cutter: Aldebaran

The corsair cutter: Surcouf

The Ship of 74 Guns: The Redoubtable (1791)

The Vessel of 80 guns: The Superb

Ships of the line:

San Juan Nepomuceno

Santissima Madre

The States of Burgundy

Victory

Arab-Indian ships:

The Boutre

The Djerme

The Boom

The Doni

The Baghala

The Dungyiah

The Dhow

The Dinghy

HMS Vanguard

Documents:

French voyages of exploration and science in the Age of Enlightenment: an ocean of discovery throughout the Pacific Ocean

By Marthe Melguen – Ifremer (EN pdf)

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign