HMS Minotaur, Defence, Shannon, Orion (cancelled) 1908-1920

HMS Minotaur, Defence, Shannon, Orion (cancelled) 1908-1920WW1 RN Cruisers

Blake class | Edgar class | Powerful class | Diadem class | Cressy class | Drake class | Monmouth class | Devonshire class | Duke of Edinburgh class | Warrior class | Minotaur classIris class | Leander class | Mersey class | Marathon class | Apollo class | Astraea class | Eclipse class | Arrogant class | Highflyer class

Pearl class | Pelorus class | Gem class | Forward class | Blonde class | Active class | Bristol class | Weymouth class | Chatham class | Birmingham class | Birkenhead class | Arethusa class | Caroline class | Calliope class | Cambrian class | Centaur class | Caledon class | Ceres class | Carlisle class | Danae class | Cavendish class | Emerald class

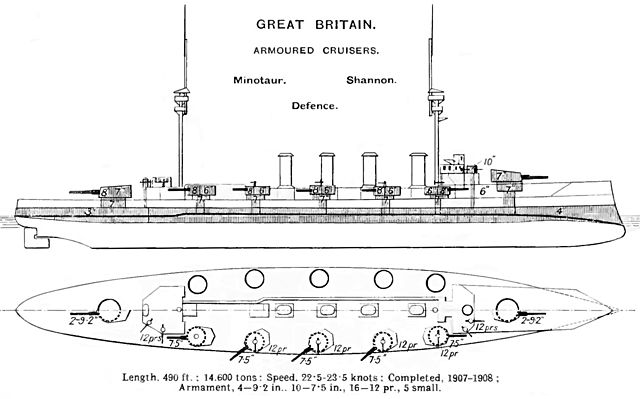

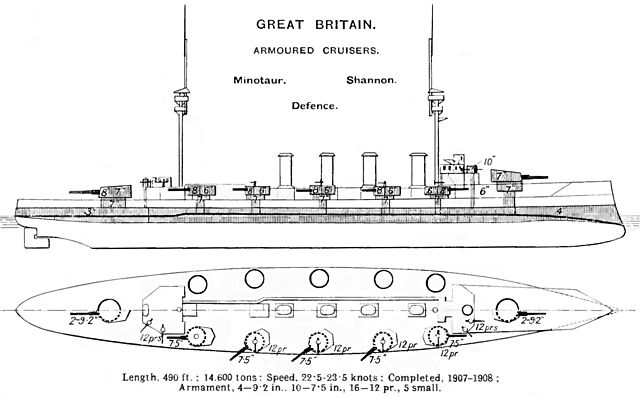

The last British Armoured cruisers: The three Minotaur class marked an additional milestone towards a semi-monocaliber heavy artillery, to the detriment of protection, with heavier tonnage and greater dimensions. There were still two twin turreted main guns fire and aft, and many secondary heavy guns in single wing turrets, with a remarkable arc of fire. Their hull was also one foot (30 cm) wider, but given their similar machinery as the previous class, this traduced into a loss of speed down to 22.5 knots. Protection singularly revised downwards, except the two twin main turrets and their communication wells. Their funnels were shorter, posing spotting issues to the bridge in downwind. They were thus raised in 1909 by 14 ft (4.50 m) while in 1917 HMS Minotaur and Shannon received tripod masts and reduced light armament with a single 3-in AA mount.

Accepted in service in 1908, so at the same time the first battlecruisers were completed, their career remained active, HMS Defense being based in China in 1912 and with the 1st squadron in the Mediterranean. She chased the Germans Goeben and Breslau to the Dardanelles and rallied Admiral Cradock in the Falklands, but was not present at the Battle of Good Hope Cape. By 1915, she became flagship of the 1st cruiser squadron and took part in the Battle of Jutland, sunk by Friedrich der Grösse. HMS Minotaur was based also in China from 1910 to 1914 and covered an Australian troopship convoy to the Mediterranean, became flagship of the Falklands Squadron before joining the Grand Fleet, overhauled and by 1916 in the 2nd Cruiser Squadron at the Battle of Jutland. HMS Shannon was with the 2th Cruiser Squadron in 1914, relocated to Cromarty, and she took also part in the Battle of Jutland. In November 1916 she escorted convoys to Murmansk and until the end of the war, North Atlantic convoys under decommissioned in 1920.

Development of the Minotaur class

The Minotaur-class ships were the last armoured cruisers of the Royal Navy, significantly larger, more heavily armed than the Duke of Edinburgh class, although with a reduced protection to compensate for a heavier armament and not loose to much stability. Later, the design was also criticized for this and the wide dispersal of 7.5-inch (191 mm), albeit others found it advantageous in terms of redundancy. Naval historian R. A. Burt called them “cruiser editions of the Lord Nelson-class battleship”. E.H.H. Archibald of the Greenwich National Maritime Museum described them as “armed in a manner that presented one of the most ferocious sights in the fleet”. The class originally counted four ships, which was the norm to create a csquadron at the time. She would he been named HMS Orion, but was cancelled due to budget pressure (HMS Dreadnought built, thwo battlecruisers on the way) and due to the unexpected purchase of the Swiftsure-class battleships, former Indipendencia made for Chile and cancelled after a treaty putting an end to the first south american naval arms race.

Design of the Minotaur class

Hull and general design

The Minotaur class displaced 14,600 long tons (14,800 t) standard (or as buiult), 16,630 long tons (16,900 t) deeply loaded (with all ammunition, oil, food, water and crew on board). HMS Defence and Minotaur were thei own sub-class at 519 feet (158.2 m) long for 74 feet 6 inches (22.7 m) in beam, for a mean draught of 26 feet (7.9 m). Shannon differed in design as she was one foot (30 cm) beamier even and thus caused one foot less in draught. That was done to test if the draught patter more than the beam in order to gain speed.

Compared to the previous DoE (Duke of Edinburgh) they gained 1,050 long tons (1,070 t) more in displacement while being longer at 13 feet 6 inches (4.11 m) overall, with a bit more freeboard than their predecessors. Their metacentric height was 3.05 feet (0.9 m) standard, 3.25 feet (1.0 m) deeply loaded. The Minotaurs carried a crew of 779 officers and ratings, up to 802–842, between 1908 and 1912.

Greenwich museum coll. half-hull

Design-wise, for a layout perspective, they shared a lot of common points with the previous DoE class. Their prow combined a ram bow and high forecastle adapted to the rough conditions of the north sea. Like battleships, their hull had an elliptic shape all along to the pointy stern. The latter had a gallery like on battleships. They had relatively short ends and a long amidship section with the four funnels heavenly spaced, apart the fore funnel a bit close to the bridge. The latter was composed of of a bulkt structure around the conning tower supprting forward light guns, and the bridge was built behind the CT, perched on a map room, combining an enclosed ridge with wings and rood open bridge. The two pole masts were built to only support light spotting tops. There were two for each, but the foremast in addition carried a searchlight platform.

To not clutter the long lower deck section admisdhip section where the five secondary turrets were located, all service boats were piled up aft, at the foot of the aft mast and served by a single boom. Another searchlight was located above the structure encompassinge the rear conning tower. There was a similar bulky structure supporting light guns there as well. Two other searchlights were installed on intermediary lattice platforms between funnels. The four outer win turrets were protected by bulwarks. They all could fire forward of aft in theory, albeit the muzzle blast was not going to do good on the roof on the next turret… It’s not sure it was even tested. This artillery could not of course cross-fire.

In 1909 so quickly after trials and early service it appeared that the Funnels were not tall enough, as smoke billowed in front the spotting tops and bridge, so they were were raised up to 15 feet (4.6 m) that year. This cured smoke interference with at least the bridge and reduced it for the spotting tops. During the war, in 1915–16, they received two 12-pounder AA guns feauting high angle mounts on the rear superstructure and quarterdeck. Anti-aircraft defence wa staken more seriously at that stage indeed. In 1916 the formast seemed too weak to support tehe new fire control systems that were developed and they were reinforced by two legs. The new fire-control director by Barr & Stroud gave them a much greater optical range and better accuracy. HMS Shannon received it just after the tripod was created, and Minotaur later in 1917–18 as these were in high demand. It was for the first right in time for Jutland, but not the latter. In 1918 vvibration showed this intermediary solution of legs was not sufficient and a true tripod was needed, which replaced their foremast. At the same time, their forwar 12-pounder AA was moved to the top of the forward turret for a better fire angle.

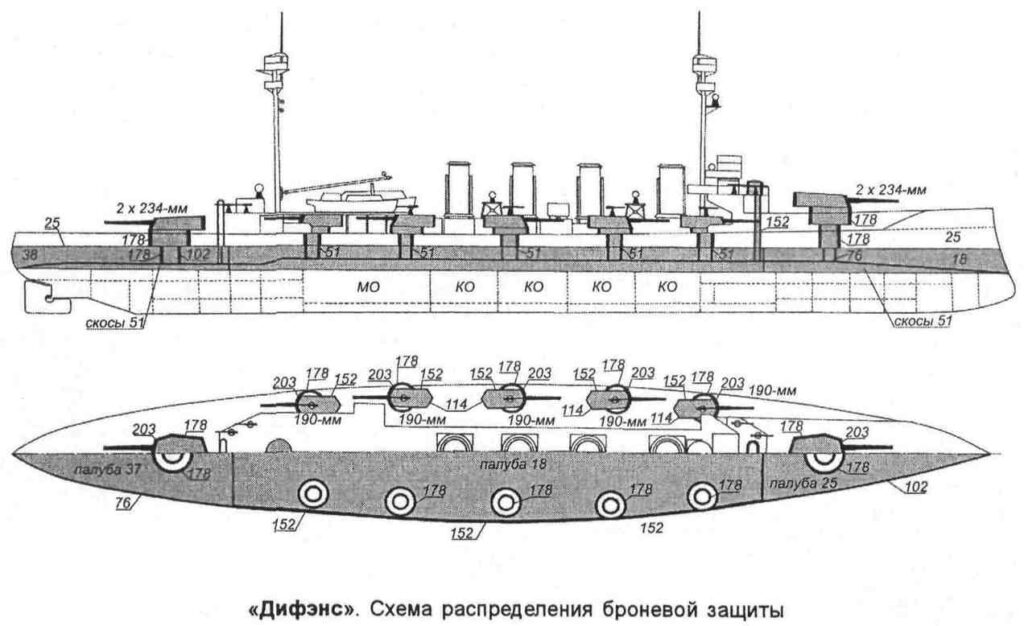

Protection of the Minotaur class

The Armour scheme was degraded as said above compard to the previous DoE and this was criticized. The upper belt was considered superfluous as the main deck casemates were eliminated, as the transverse bulkheads connecting the waterline belt to the barbettes against raking fire. So in short, they lacked a proper citadel. The 6-inch (152 mm) waterline armour belt wa smade from Krupp cemented armour under licence, and it extended past the fore and aft 7.5-inch gun turret barbettes. The main belt lower edge went 5 feet (1.5 m) deep below the waterline (normal load).

Forward it was tapered down by a 4 inches (102 mm) thick belt extension 50 feet (15.2 m) from the bow, and then ended to the bow itself tapared down to just 3-inches.

Aft the belt armour there was an extension to the stern of 3 inches thick, so less than forward.

The machinery was covered by a stray of armour plating up to 1.5–2 inches (38–51 mm) thick in guise of a proper armoured deck.

-The main turrets had 8 inches (203 mm) thick faces, 7-inch (178 mm) sides.

-The main barbettes had 7 inches of armour to protect the ammunition hoists, down to the belt. It was indeed thinned to 2-inches between the lower and main decks.

-The secondary 7.5-inch turrets had 8-inches face but 6 inches (152 mm) thick sides. Barbettes were 7 inches down to the belt and then 2-inches (51 mm).

-The waterline turtledeck war armoured also, but this ranged from 1.5 inches or 38 mm (flat amidships) to 2 inches or 51 mm on slopes when connecting to the lower edge of the waterline belt.

-At both ends this deck armour was 2 inches.

-The forward conning tower had walls 10 inches thick or 254 mm

-The rear conning tower had 3 inches walls, or 76 mm, probably with the 2-in roof as forward.

Powerplant and performances of the Minotaur class

The Minotaur class had two four-cylinder triple-expansion steam engines (VTE), connected each to a single shaft.

They were fed by 24 water-tube boilers with a working pressure of 275 psi (1,896 kPa; 19 kgf/cm2). This combo gave them a total of 27,000 indicated horsepower (20,130 kW). Design speed was 23 knots (43 km/h; 26 mph).

As for range, they carried 2,060 long tons (2,090 t) of coal and 750 long tons (760 t) of fuel oil, to be sprayed in the boilers to increase burn rate.

At full capacity, they were able to reach 8,150 nautical miles (15,090 km; 9,380 mi) as designed, at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).

During their sea trials on 6 December 1907, Minotaur reached her designed speed at 23.01 knots based on an output of 27,049 ihp (20,170 kW) for as long as eight-hour in a full-power run.

HMS Shannon ironically proved the slowest of the class: She only reached 22.324 knots (41.344 km/h; 25.690 mph) from 27,372 ihp (20,411 kW) in trials. This was three days before Minotaur. She proved that a lower draft was not compensating a greater beam in order to gain speed. Her narrower sisters did better on the same output.

Armament of the Minotaur class

Main

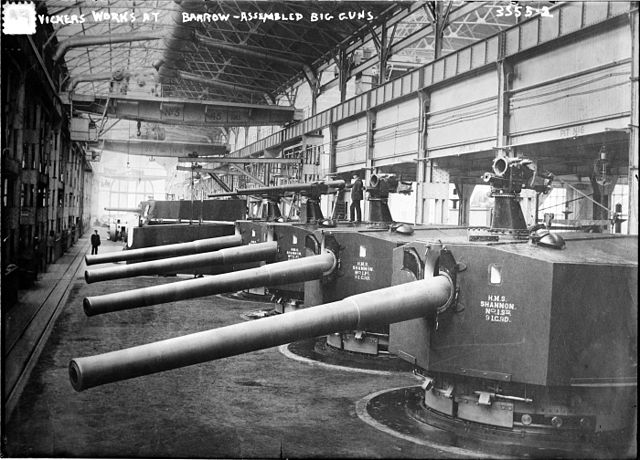

The Minotaurs carried four 50-calibre BL 9.2-inch Mk XI guns, like the DoE, but instead of having spread out in single gun turrets, had four in two twin turrets fore and aft. This brand new twin hydraulically powered centreline turrets mirrored the design of battleships turrets of the time. The design was essentially the same as for the Lord Nelson class. This gave them the same four-gun broadside as the Duke of Edinburghs but freed the sides for more heavy guns, which was the main argument for this design.

The Minotaurs carried four 50-calibre BL 9.2-inch Mk XI guns, like the DoE, but instead of having spread out in single gun turrets, had four in two twin turrets fore and aft. This brand new twin hydraulically powered centreline turrets mirrored the design of battleships turrets of the time. The design was essentially the same as for the Lord Nelson class. This gave them the same four-gun broadside as the Duke of Edinburghs but freed the sides for more heavy guns, which was the main argument for this design.

-They fired 380-pound (172 kg) projectiles at a muzzle velocity of 2,875 ft/s (876 m/s) with armour-piercing (AP) shells.

-The mounts an elevation range of −5°/+15°.

-Maximum range was 16,200 yd (14,813 m)

-Rate of fire was four rounds per minute, 100 rounds per gun were carried.

Secondary

The secondary armament was much heavier that any previous design (and in the world): Ten single gun, hydraulically powered turrets housed each a 50-calibre BL 7.5-inch Mk II gun. There were five of these on either side, their barbettes and wells protected by the belt.

-The mounts could depressed to −7.5°, elevate to +15°.

-They fired 4crh 200-pound (91 kg) AP shells wit a muzzle velocity of 2,841 ft/s (866 m/s)

-Maximum range was 15,571 yd (14,238 m).

-Rate of fire was four rounds per minute and each gun had a stock of 100 rounds.

Light Artillery

To deal with torpedo boats, all these ships had sixteen QF 12-pounder 18-cwt guns. These were the equivalent of 3-inches or 76 mm. They were located on pilvot mounts, unmasked, with eight mounted on the tops of the 7.5 inch gun turrets and the other eight in the superstructures, four fore and four aft.

-They fired 12.5-pound (5.7 kg) shells at a muzzle velocity of 2,660 ft/s (810 m/s)

-Maximum range was 9,300 yd (8,500 m), maximum elevation +20°.

Torpedo Tubes

These ships were intedned to take their place in the battle line and one of the tacrtic on papert at the time was to be able to fire their torpedoes on the oppisite battleline. Thus they mounted five submerged 18-inch torpedo tubes: Two per broadside, one in the stern as a chase defence.

Author’s profile of the Minotaur class in 1914.

Warrior class specifications |

|

| Displacement | 14,100 ton standard, 14,600 tons FL |

| Dimensions | 519 ft x 74.5 ft x 26 ft (158,2 x 22,7 x 7,92 m) |

| Propulsion | 2 shafts, 4 cyl. VTE, 24 Yarrow boilers, 27 000 shp. |

| Speed | 23 knots (45 km/h) |

| Range | 6,680 nautical miles (12,370 km) at 10 knots (19 km/h) |

| Armament | Armament: 2×2 9.2-in(234mm), 10×1 7.5-in(190mm), 16x 3-in, 5x 18-in (457mm) TT (sub). |

| Armor in(mm) | Belt 6(152), Barbettes 7(178), turrets 8(203), CT 10(254), decks 1(20). |

| Crew | 755 |

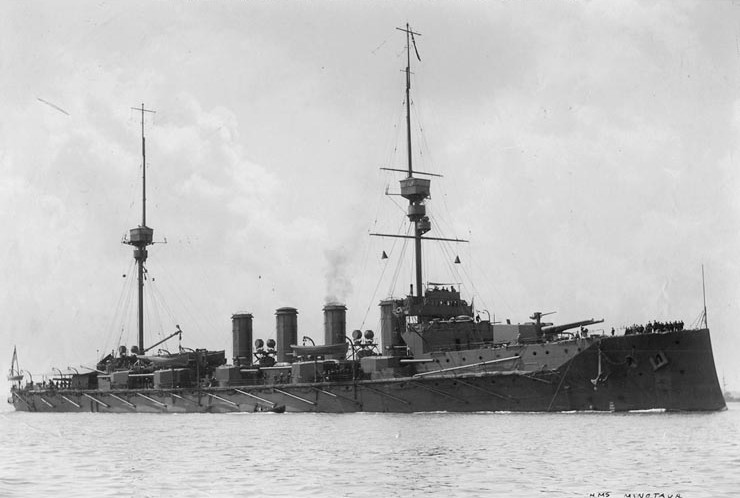

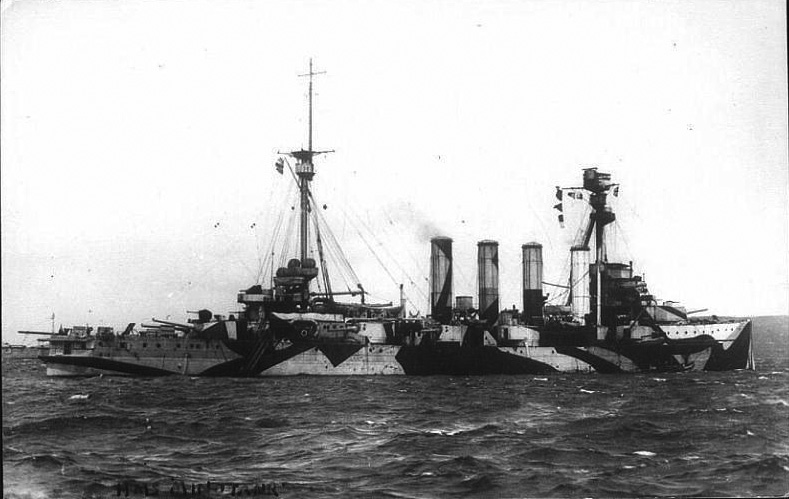

HMS Minotaur

HMS Minotaur

HMS Minotaur in 1917-18

HMS Minotaur was ordered under the 1904–05 naval construction programme. Laid down on 2 January 1905 at Devonport Royal Dockyard she was launched on 6 June 1907 (baptises by the Countess of Crewe). Just before commission as she was worked out, she suffered a coal gas explosion injuring three sailors plus a dockyard worker on 6 November. She was commissioned on 1 April 1908 for a cost of £1,410,356.

Soon before trials she was assigned to the 5th Cruiser Squadron, Home Fleet. She escorted the royal yacht “Victoria and Albert” from Kiel to Reval in the baltic, King Edward VII and his wife visiting Nicolas II of Russia for this June state visit, after the Kaiser. The next month, HMS Minotaur escorted HMS Indomitable hosting the Prince of Wales to Canada in order to commemorate the tercentenary of Quebec City. Back home she was sent to the 1st Cruiser Squadron after the reorganizion of 24 March 1909. She took part in two fleet reviews, June and July and then was ordered to the China Station by January 1910, relieving HMS King Alfred as squadron flagship.

She was in Wei Hai Wei on 3 July 1914 as war was looming near, and were were ordered to Hong Kong. As the First World War broke out she sailed with the older armoured cruiser HMS Hampshire and light cruiser HMS Newcastle sailed to Yap Island (Carolines), at the time German controlled. They captured the collier Elisabeth on 11 August there, destroyed the radio station with gunfire. Looked then for the East Asia Squadron without success, until SMS Emden was reported afetr her diversionary trampage in the Bay of Bengal by mid-September.

HMS Minotaur was ordered to patrol the west coast of Sumatra. When it was ibvious Emden disapparead again, she was sent to escort an ANZAC troop convoy from Wellington in New Zealand by late September to the Indian Ocean and Suez. But she was detached from the convoy as the Cape of Good Hope needed reinforcement against the probable passage of Von Spee. In reality Emden played a ruse as Maximilian took the way east, towards South America. The was at the Cape on 6 November when reported the Battle of Coronel and terrible deteat. Not doubt the could have dealt with ease and defeat the two Scharnhorst class. She became flagship of the Cape of Good Hope Station (Vice Admiral Herbert King-Hall). She later escorted a South African troop convoy to Luderitz Bay, German South-West Africa for a landing and campaign. She was off Table Bay when learning about the Von Spee’s dedfeat in the Battle of the Falklands by early December, and since the perile was not there anymore, ordered home by 8 December.

Minotaur became flagship at home of the 7th Cruiser Squadron (Rear Admiral Arthur Waymouth) in Cromarty Firth. She had a brief refit and drydock overhaul by early 1915 and was assigned to the Northern Patrol almost until the battle of Jutland. In addition to her 12-cwt anti-aircraft (AA) gun she received a QF three-pounder (47 mm) AA gun as well. She was transferred to the 2nd Cruiser Squadron on 30 May 1916 and took part in the Battle of Jutland as flagship of Rear Admiral Herbert Heath.But she was unengaged and never fired in anger her 9.2 or 7.5-inch guns.

Later on 19 August she took part in an interception of the High Seas Fleet. She was assigned until November 1918 to the Northern Patrol. On 11 December 1917 with her sister Shannon and four destroyers, she patrolled between Lerwick and Norway and could not prevent the loss of a convoy off the Norwegian coast. They arrived only to rescue survivors and escort the sole survivor ship (destroyer Pellew) back to Scapa Flow.

In 1917–18 she had a AA gun reshuffle and new fire-control system installed with modern director atop a tripod mast. She was paid off on 5 February 1919, sold in March 1920 for BU.

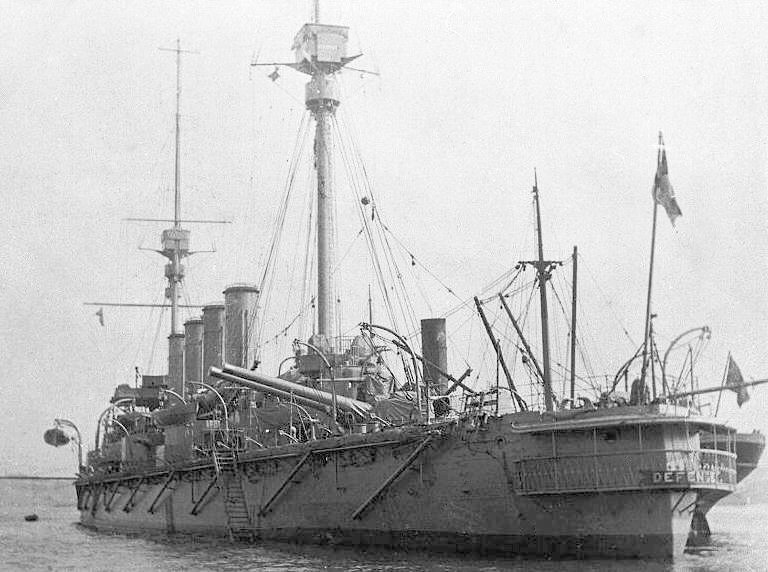

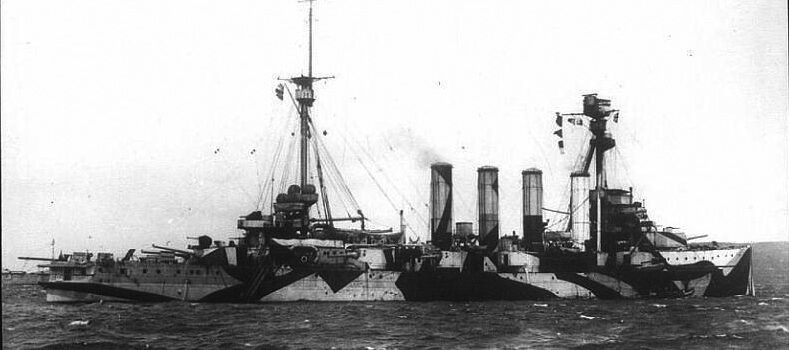

HMS Defence

HMS Defence

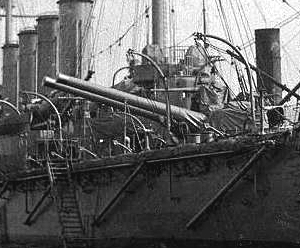

Stern of HMS Defense as completed before the war

HMS Defence was ordered in the 1904–05 programme. Se was the last laid down, on 22 February 1905 at Royal Dockyard, Pembroke Dock in Wales, launched on 27 April 1907 (by Lady Cawdor) and commissioned on 3 February 1909 (cost £1,362,970). Assigned to the 5th Cruiser Squadron, Home Fleet and then 2nd Cruiser Squadron from 23 March 1909 and by June, to the 1st Cruiser Squadron. She escorted the ocean liner RMS Medina in 1911–1912 (royal yacht for King George V) to India at the Delhi Durbar. She was back in Plymouth by early 1912 and soon after transferred to the China Station until December and then back to the 1st Cruiser Squadron, Mediterranean, as flagship.

A few hours After the First World War broke out, she chased the two Souchon’s Med Sqn. warships she shadowed until the, SMS Goeben and Breslau but refrained to open fire as Rear-Admiral Ernest Troubridge ordered not to engage Goeben, a better adversary. She blockaded them inside the Dardanelles until the changed flag. Next she was ordered on 10 September to the South Atlantic, trying to catch the East Asia Squadron. This was cancelled on 14 September as the latter were believed still in Eastern Pacific and she returned to the Dardanelles. Alas, the Yavuz and Midilli (new names) were now for long in action in the black sea. She was ordered again to the South Atlantic by October to join RADM Cradock, but wa soff reached when learning about the Battle of Coronel. She eventually met the battlecruisers HMS Inflexible and Invincible to transfer her long-range radio equipment to Invincible and escorted a troop convoy for home, from Table Bay, Cape Town on 8 December. She was back with the 1st Cruiser Squadron, Grand Fleet as flagship in 1915.

She received a short refit and stayed on patrol until the Battle of Jutland, as flagship, Rear-Admiral Sir Robert Arbuthnot, 1st Cruiser Squadron, as starboard flank of the cruiser screen, and after evolution, she was found just to the right of the centre of the line. At 17:47 with HMS Warrior (leading their respective squadrons) she spotted the German II Scouting Group and combat started. Their fire fell short and they started a pursuit in front of the battlecruiser HMS Lion, narrowly avoiding collision. They soon spotted the German light cruiser SMS Wiesbaden but when ready to engage her at 5,500 yards (5,000 m) they were spotted at 18:05 by German battlecruiser SMS Derfflinger and four battleships at just 8,000 yards (7,300 m). HMS Defence was hit by two salvoes and her 9.2-inch magazine exploded. The fire spread via ammunition passages to the adjacent 7.5-inch magazines and she had a serie of explosions that broke her in two at 18:20, sinking with all hands (between 893 and 903 men).

Her wreck was rediscovered in mid-1984 by Clive Cussler in a survey of the North Sea. She was explored by divers in 2001 (Innes McCartney) and surprisingly found intact, then declared a protected place under the act of 1986.

HMS Shannon

HMS Shannon

Stern of HMS Shannon in 1914

HMS Shannon was ordered under the same 1904–05 naval programme, laid down on 2 January 1905 at Chatham Dockyard, launched on 27 April 1907, Christened by Lady Carrington, commissioned on 19 March 1908 (cost £1,415,135). While fitting out in Portsmouth she was bumped at low speed on 5 December 1907 by HMS Prince George, broke loose from her anchorage.

She became flagship of the 5th Cruiser Squadron, Home Fleet, then 2nd Cruiser Squadron, commissioned as private ship from April 1909 for the King, then flagship of her squadron on 1 March 1910. She visited Torbay in January 1911. She was replaced as flag by the battlecruiser Indomitable on 5 March 1912, transferred to the 3rd Cruiser Squadron as flagship. In January 1914, she relieved Indomitable in turn as flagship during exercises off Spain. Shannon and the 1st Battlecruiser Squadron, 2nd Cruiser Squadron later visited Brest, France.

In October 1914, she was patrolling off the coast of Norway and spotted, intercepted the German armed merchant cruiser SS Berlin. She sailed into the Heligoland Bight on 26 November when bombed and missed by a German aircraft. She hd a refit until 24 January 1915. She was in Cromarty Firth as the Armoured Cruiser HMS Natal had a magazine explodin on 30 December 1915, she sent boats to rescue rescue survivors.

She was like her sisters present at the Battle of Jutland on 31 May 1916 but stayed mostly unengaged. After the battle she stayed searching survivors for several days. HMS Shannon was paid off on 2 May 1919, started a new life as accommodation ship until sold for BU on 12 December 1922.

Read More/Src

Books

Burt, R. A. (1987). “Minotaur: Before the Battlecruiser”. Warship. 42. London: Conway Maritime Press: 83–95. ISSN 0142-6222.

Campbell, John (1998). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 1-55821-759-2.

Corbett, Julian. Naval Operations to the Battle of the Falklands. History of the Great War: Based on Official Documents. Vol. I (2nd, reprint of the 1938 ed.). London and Nashville, Tennessee: Imperial War Museum and Battery Press. ISBN 0-89839-256-X.

Corbett, Julian (1997). Naval Operations. History of the Great War: Based on Official Documents. Vol. II (reprint of the 1929 second ed.). London and Nashville, Tennessee: Imperial War Museum in association with the Battery Press. ISBN 1-870423-74-7.

Corbett, Julian (1997). Naval Operations. History of the Great War: Based on Official Documents. Vol. III (reprint of the 1940 second ed.). London and Nashville, Tennessee: Imperial War Museum in association with the Battery Press. ISBN 1-870423-50-X.

Dixon, John (2008). A Clash of Empires (1st ed.). Wrexham, Wales: Bridge Books. ISBN 978-1-84494-052-3.

Newbolt, Henry (1996). Naval Operations. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents. Vol. IV (reprint of the 1928 ed.). Nashville, Tennessee: Battery Press. ISBN 0-89839-253-5.

Newbolt, Henry (1996). Naval Operations. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents. Vol. V (reprint of the 1931 ed.). Nashville, Tennessee: Battery Press. ISBN 0-89839-255-1.

Parkes, Oscar (1990). British Battleships (reprint of the 1957 ed.). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-075-4.

Specs Conway’s all the world fighting ships 1921-1947.

Links

The Minotaur class on wikipedia

Videos

Model Kits

3D

Note: First Published on Apr.5, 2018

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign