The famous “Condotierri” cruiser class was an invention from postwar authors, trying to group a serie of light cruisers named after ancient Italian warlords but built for various purposes. The first of these were also the first post-WWI Italian cruisers to see service. Five classes followed one another, but they were quite different. The first two series were very lightly built destroyer hunters in the 5,000 tons range, while the second series (three classes) were ranging from 8,000 to 10,000 tons (D’Aosta group and following), trying to marry speed and protection at best.

However the early “tin-clad cruisers” of the first two series, Giussano and Cadorna, did not left a good impression on their adversaries, mostly due to their own limitations and task, destroying French large destroyers and not engaging their equivalents. They were way to small and fragile to fight other cruisers and proved heavy preys even for enemy destroyers.

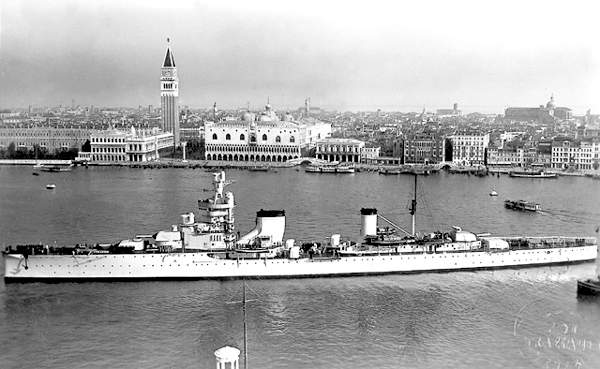

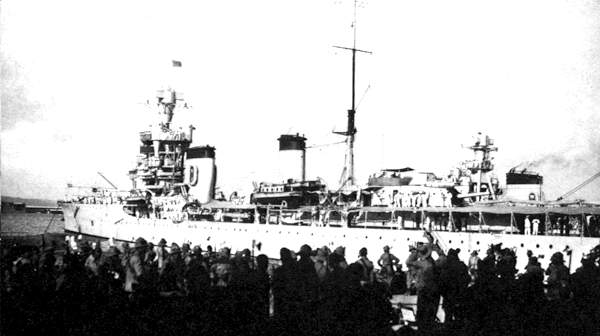

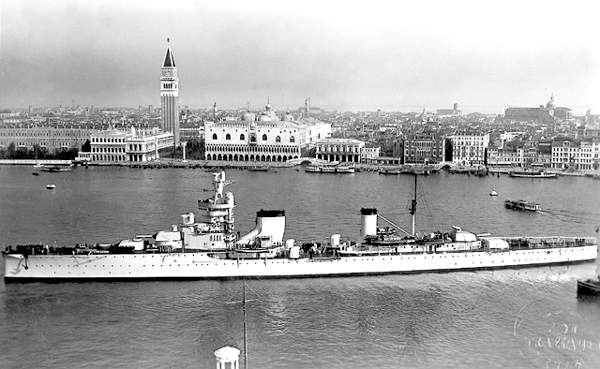

Bartolomeo Colleoni in Venice

Early developments

Italian experience with cruisers ceased with the Quarto, first Italian turbine cruiser in 1911 and the Nino Bixio class, Two “Esploratori” (scouts) from Castellamare du Stabia. Nino Bixio and Marsala were designed by the same engineer, Giuseppe Rota, which created the Quarto. Great speed should be reached but was never approached on trials. Only Marsala closely reached the contract speed of 27.5 knots, heating boilers to be rated at 22,500 hp. They entered service in May and August 1914, and were quite active during the Great War. However they accumulated problems of engine reliability and performed poorly compared to the Admiral Spaun class of the same generation. They were stricken in 1927-1929. Technically the last Italian cruisers has been the two Campania class (1914) but they were merely glorified gunboats for colonial service.

In 1926 the French unveiled their first destroyer leader class, called “le Fantasque”. They were quite superior to any Italian destroyer of the time and made even a threat for larger ships. The admiralty decided to built “budget” small cruisers, between destroyers and proper cruisers to catch an sink these destroyers.

Preliminary work was given to general Giuseppe Vian. The latter started from there to create the new cruisers needed by the Regia Marina; Vian worked under his senior engineer, the famous Giuseppe Rota. The latter was the first director of La Spezia Naval base and of INSEAN (Naval Institute), considered the father of modern Italian naval architecture.

He was also in 1890 director of the Castellammare di Stabia shipyard, General Inspector of the Corps of Naval Engineers, and dedicating most of his career naval architecture. He created models to test hydrodynamic shapes and test water in motion.

He collaborated with Edoardo Masdea on the battleship Dante Alighieri and designed the Nino Bixio. he also designed a conversion in aircraft carrier for the cancelled Francesco Caracciolo, and also designed an hybrid carrier/cruiser which was presented but not approved by the Ministry of the Navy. He would also design the large Navigatori class destroyer and worked in close collaboration with General Giuseppe Vian on the Alberto di Giussano light class cruiser class, advocated after his long service for the creation of the National Institute for Studies and Experiences in Naval Architecture (INSEAN) in 1927.

Design of the Giussano class

Outside the Nino Bixio and Quarto of WW1, design influences could have been drawn from the war reparation cruisers obtained by Italy in 1920: The Taranto (1911, ex-German Strassburg), Bari (1914, ex-German Pillau), Brindisi (ex-Austrian Helgoland), or Ancona (ex-German Graudenz).

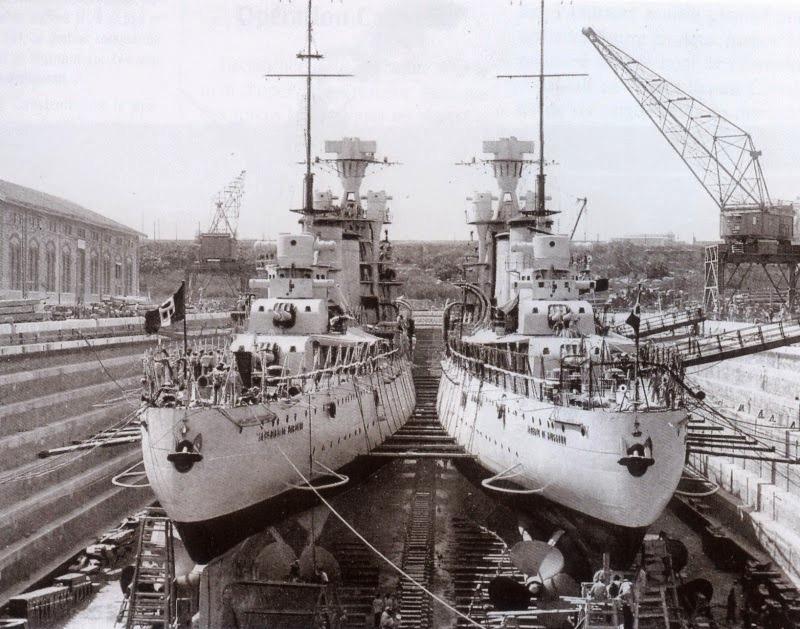

The Giussano class were the first ships of the “Condottieri” serie. They were named indeed after famous Italian Condotierre, historical figures such as Alberico da Barbiano (1349-1409, leading the Compagnia San Giorgio), Alberto di Giussano (Lombard legendary Guelph warrior during the wars of the Lombard League against Frederick Barbarossa in the 12th century), Bartolomeo Colleoni (captain-general of the Republic of Venice of the XVth century) and Giovanni delle Bande Nere (Lodovico de’ Medici).

The Giussano class were the first ships of the “Condottieri” serie. They were named indeed after famous Italian Condotierre, historical figures such as Alberico da Barbiano (1349-1409, leading the Compagnia San Giorgio), Alberto di Giussano (Lombard legendary Guelph warrior during the wars of the Lombard League against Frederick Barbarossa in the 12th century), Bartolomeo Colleoni (captain-general of the Republic of Venice of the XVth century) and Giovanni delle Bande Nere (Lodovico de’ Medici).

These cruisers were originally designed to engage the heavy French destroyers of the Aigle, Jaguar and Lion classes. In order to catch them, they sacrificed everything to speed. Although they were designed to reach 39 knots on trials, RMS Barbiano reached 42 knots by forced heating and empty, earning the world record for a cruiser. Only the later French Le Fantasque class large destroyers could reach this speed.

To achieve this goal, the cursor was down to almost zero for protection, minimalistic at best. Also they were relatively top-heavy because of their superstructure and high, narrow hull, rolling badly as a result. The cruisers of the first group designed by General Giuseppe Vian, started in 1928 and in service in 1931 had powerplants equivalent to those of the much heavier Zara-class cruisers, but without any protection.

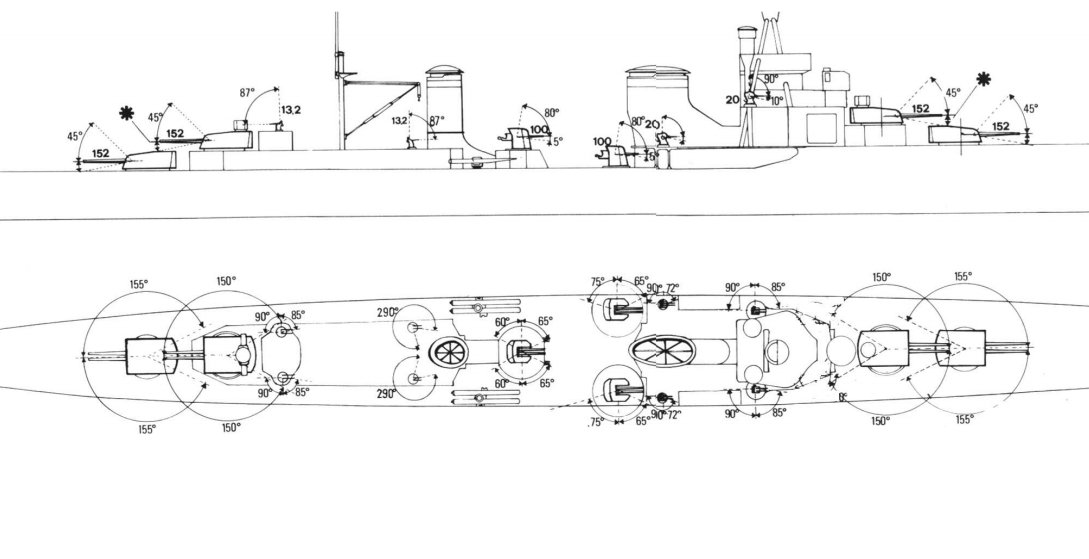

Armament

To overwhelm French destroyers, these cruisers were armed with a comfortable margin: Height 8-in guns or 152/53 mm Ansaldo 1926 artillery pieces in four twin mounts. All four turrets were mmounted in superfiring pairs force and aft. These were true twin mounts, in which both barrels were elevated in concert. There was no independent elevation. The guns made by Ansaldo weighted 7.22 t, versus those of OTO, 7.57 t. Barrel were 6.682 m long, with a shell weight of 50 kg (AP model 1926), or 47.5 kg (Mod. 1929 AP) and 44.3 kg (HE), with a muzzle velocity of 1000 m/s (For the AP Mod 1926), 850 m/s (AP Mod. 1929) and 950m/s (HE). Maximum range was 24.6 km (For the HE) down to 22.6 Km for the 1929 AP shells. Elevation was -5°/+ 45° (Mod. 1926) and -10°/+45° (Mod. 1929).

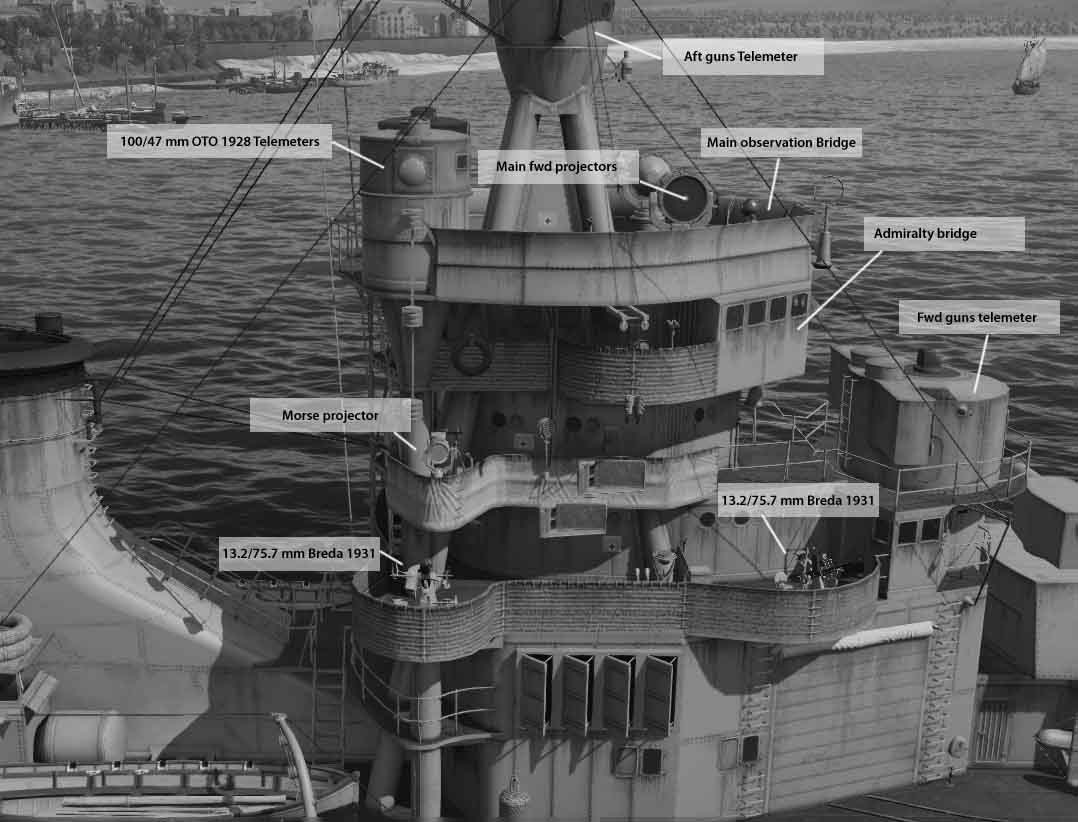

Secondary armament comprised six 100/47 mm OTO 1928 in three 3 twin mounts, two placed either side of the forward funnel and one centerline on the aft quarterdeck, in front of the rear funnel. These models were derived from the WW1 Škoda 10 cm K10 da 100 mm which armed the Novara type cruisers obtained as war reparations. The mount and barrel weighted 2,177 ton, barrel lenght was 4 985-4 940 mm, with 26 caliber. The type of shell-and-cartridge integrated ammunition weighting 26.02 kg, with a firing rate of 8 to 10 rounds a minute at a velocity of 840-880 m/s and maximum range of 12 600-15 400 m.

Secondary armament comprised six 100/47 mm OTO 1928 in three 3 twin mounts, two placed either side of the forward funnel and one centerline on the aft quarterdeck, in front of the rear funnel. These models were derived from the WW1 Škoda 10 cm K10 da 100 mm which armed the Novara type cruisers obtained as war reparations. The mount and barrel weighted 2,177 ton, barrel lenght was 4 985-4 940 mm, with 26 caliber. The type of shell-and-cartridge integrated ammunition weighting 26.02 kg, with a firing rate of 8 to 10 rounds a minute at a velocity of 840-880 m/s and maximum range of 12 600-15 400 m.

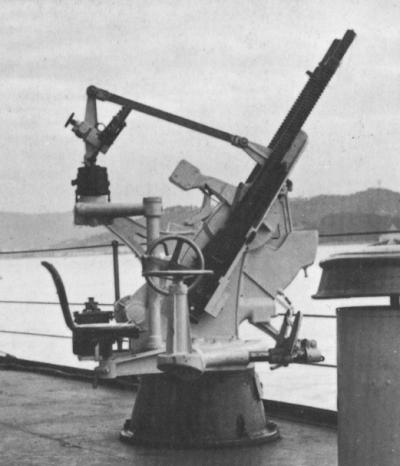

Breda twin 37 mm/54 model 1938 AA

The AA armament comprised four twin mounts of the Breda 37/54 mm. They were placed either side of the boat deck, between the rear funnel and mainmast, and in nacelles in the bridge superstructure. It seems they were not protected by a shield as delivered a shown in the blueprints. These twin mounts weighted 277 kg with a Barrel length of 1998 mm, shell weight of 830g, a Gas operated-drive for 140 rpm at 800m/s and 3,500 m useful range, top range of 6,000 m. They were fed by 6 vertically placed cartridges racks, while the mountings had an elevation from -5° to + 85° and 360° angle. They were Water cooled on Mod. 1932 buu air cooled on the newt Mod. 1938 and 1939.

Breda Model 31 13.2 mm HMG

This was completed by four twin 13.2/75.7 mm Breda 1931 heavy machine guns, placed on the bridge forward main deck, and rear bridge superstructure.

In 1938-39 the 37/54 guns were replaced with new 20 mm/65 guns and two ASW planes were carried to be deployed both for protection and reconnaissance. These were IMAM Ro.43, sturdy but slow biplanes launched from a forward deck catapult.

IMAM Ro.43 on the front catapult of Zara. The same system was used on the Guissano class cruisers.

Powerplant

Since speed and armament were favored over protection, the latter was to be sufficient to catch French destroyers and flee superior adversaries, as an active protection. The propulsion group comprised two propellers, on shafts connected to Belluzo geared Turbines fed by six Yarrow boilers, rated for a total of 95,000 hp. As a result top speed was 37 knots (69 kph) as designed and up to 42 knots (78 km/h) in speed trials, maintained for a short while however. This was good to create a record and sensation on the world stage, a propaganda coup for the regime, but in 1940-41 these engines were already tired and no longer able to provide the necessary speed. It was unsufficient anyway to protecte the ships against torpedoes and mines. Autonomy was 3,800 miles at 18 knots (7,000 km at 33 km/h).

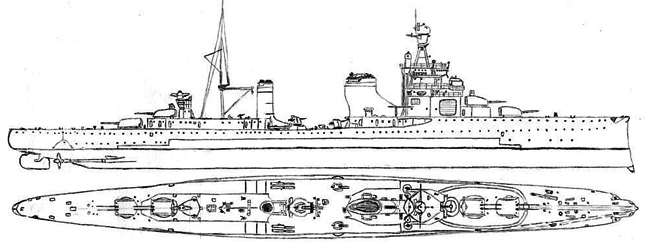

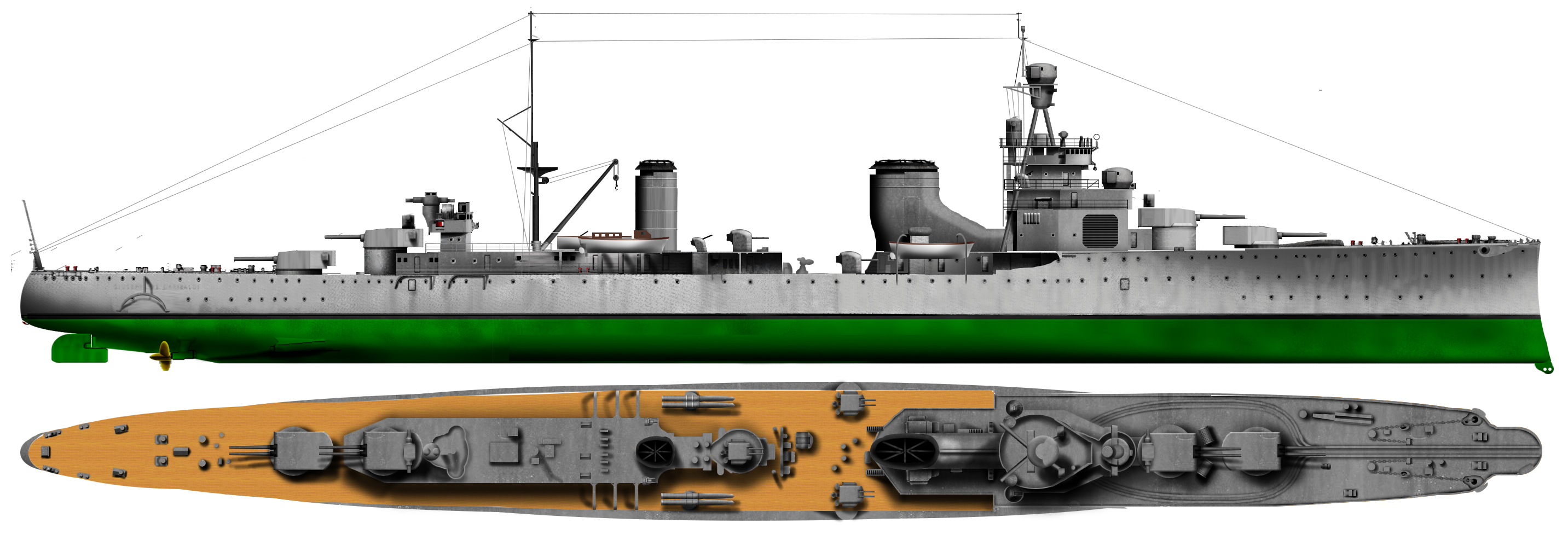

HD Illustration of the Guissano class

Protection

These ships as seen above had a ridiculous level of protection, between 20 and 40 mm, with many areas totally uncovered. Even the 102 and 120 mm British destroyers had all chances of get through at all shooting distances. This scarce armor was heavier around the conning tower to protect the backup controls, but less impressive above and around the engines. Underwater protection was also lacking, especially compared to the units launched for the Regia Marina in the following years. For all these reasons this first vessels serie were called -even by their crews- “paper cruisers” or even “tissue paper cruisers”. The armament was good for the time but clearly inadequate on the anti-aircraft side (active protection), given the rapid development of aviation in the second half of the 1930-40s.

Military planners of the Regia Marina at the time these ships were designed, mainly compared to the French navy (of which speed was a fundamental factor), was based on the assumption, theoretically correct but in practice surpassed by facts, that high speed could be a substitute of protection against torpedoes. Like battlecruisers, this allowed these cruisers to attack in conditions of superiority and flee in inferiority. One concrete example were the Austro-Hungarian cruisers of the Admiral Spaun class, managing to escape clashes, raiding the coast and wrecking the otranto barrage before the Italian fleet or the allies could arrive. The threat posed by mines was also underestimated by the naval staff, perhaps given the more open theater of operations.

Terrible compromises

As a result of these choices, these “tin-clad cruisers” (also made by France a the time) were all sunk with relative ease during the war. As a result of their inexistent protection against shell fire and lack of any ASW measure, all the units of the Di Giussano type were sunk in action: The Colleoni in 1940 during the Battle of Cape Spada, the Alberto of Giussano and the Alberico da Barbiano in 1941 during the Battle of Cape Bon and the Giovanni delle Bande Nere in 1942 off the coast of Stromboli.

Compared to the rest of the Condotierri group, There was a progressive increase in armor, initially very low, with a belt thickness that did not even reach the ships’s speed in knots (25 mm versus 42 knots). This changed over time, to reach 130 mm in the fifth group of the Duca degli Abruzzi class. As a result the Bartolomeo Colleoni stood little chances against HMS Sidney while the Garibaldi survived two torpedoes from the British submarine HMS Upholder.

Evolution

The two following Cadorna class ships kept the features with only minor changes and rather than light cruisers were merely large explorers. Real light cruisers were started from the Montecuccoli class, heavily modified and much heavier with significantly better protected and more reliable engines in order to maintain the required speed for long. The two units of the Duca d’Aosta class continued the trend with greater armor thickness and better engines power. This trend to sacrifice some speed to reach a better protection, combined with the extra guns made them the best of the whole Condotierri group.

A missed AA conversion project

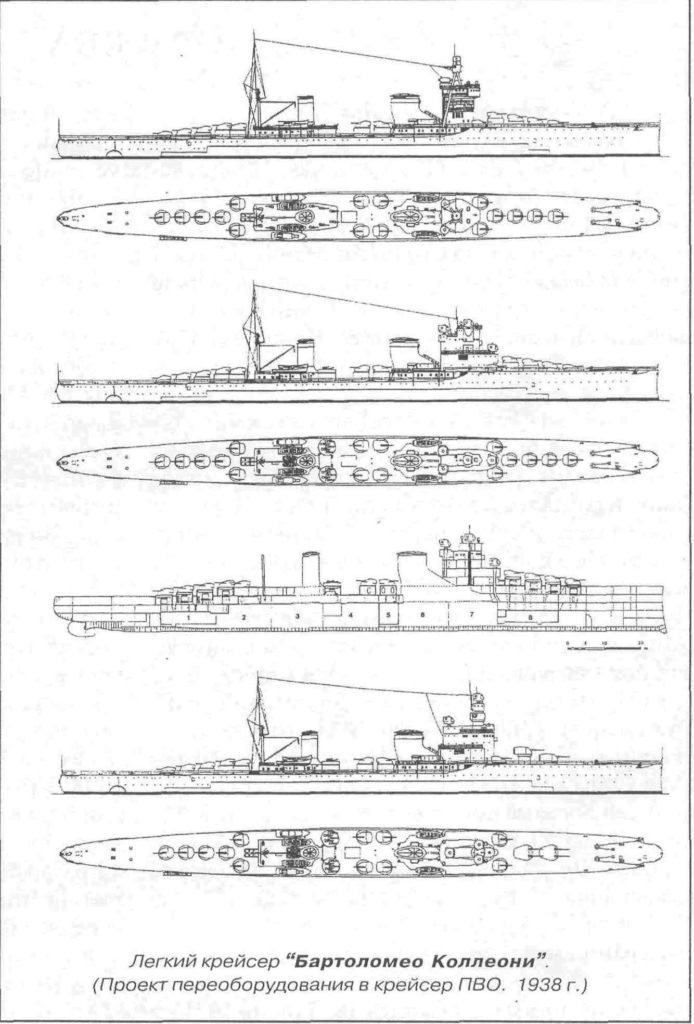

Profiles from Franco and Valerio Gay “The Cruiser Bartolomeo Colleoni” (Conway Maritime Press) showing drafts by the Comitato Progetti Navi (in-house navy design team) and O.T.O. yards. The First design of February 1938 (top) was the most radical. They were 16 single 90mm/48, and the gun was still under development at the time. This pretty simple conversion allowed the fire control equipment to be installed on the slightly modified bridge. Deck would have been reinforced with 30mm of nickel-chrome steel plates, helped by the removal of the heavier 152mm turrets.

In 1938 already it was realized, these Di Giussano and the 2 Cadorna were too weak to face any British units it was thought to turn these early cruisers into anti-aircraft dedicated cruisers, like the Royal Navy was making of old C-class light cruisers. Thes escort conversion ensured the protection of the fleet and of lines of maritime communications in coastal waters. The idea was copied by the US Navy (with the Atlanta) and recalled on a dedicated platform later with the Dido class in UK.

These anti-aircraft cruisers had a considerable advantage in terms of stability compared to escorting destroyers, as they were more stable platform due to their size, had better or more fire control systems. For cost issues, the admiralty settled on the conversion of the four Di Giussano cruisers only. However budget and time only allowed to convert the first two of this sub-class. The admiralty still needed the remainder to fill their cruiser role, waiting for the Costanzo Ciano 12,000-ton sub-class to enter service and replace them. However both Costanzo Ciano and Luigi Rizzo, scheduled in 1938 for 1941-1942 were canceled in June 1940.

This transformation would have been very extensive bu rational with a reduction in the engines, two less boilers, but greater cost-effectiveness, range, to the cost of top speed. The new layout comprised a very powerful AA armament, sixteeen 90 mm guns in single mounts plus and twenty 20 mm Breda heavy machine guns in 10 twin mounts. The second conversion plan was less radical ans called for four 135 mm guns remained, as well as twelve 90 mm guns, eight 37 mm twin mounts, and sixteen Breda 20 mm.

This second variant would have guaranteed some protection against light enemy ships. Indeed the excellent 135 mm was less powerful and had a lower range than the 152 mm (6 in) but was remarkably more precise and can reload faster. They would have been very suitable for escort tasks, in the battle fleet and above for convoys with Africa and the Balkans. The problem of a weak armor persisted however, with the same underwater protection only compensated by the addition of counter-keels, not included in the final plan. It was decided, however, to abandon the project to concentrate the available resources and the completion of the battleships. This old obsession of the admiralty also conducted to a costly conversion of the surviving dreadnoughts of the Doria and Caesare classes.

The Guissano class in action:

In short in service, the Giussano class proved uncomfortable, with poorly designed internal arrangements and lack of autonomy and engine reliability as well. In fact none survived the war, Bande Nere being sunk by the submarine HMS Urge, the Colleoni in July 1940 in a duel with the cruiser Sydney, the Barbiano and Giussano by the destroyers HMS Legion, Maori, Sikh and Dutch destroyer Isaac Swers during the battle of the cape Bon in December 13, 1941.

Alberto Di Guissano

This cruiser, launched on April 27, 1930 was completed in June the next year and commissioned into the Regia Marina. In the 1930s she participated in the normal peacetime routine of the fleet as part of the 2nd Squadron. She patrolled also during the Spanish civil war. On 10 June 1940, together with the 1st Squadron, she was part of the IV Cruiser Division. She was involved in the battle of Punta Stilo in July 1940, during which she launched an IMAM Ro.43 seaplane for reconnaissance. She carried out a sortie to lay mines off the coast of Pantelleria in August 1940 and acted as a cover for some coastal operations and protecting supply convoys to and from North Africa until the end of the year.

On December 9, 1941, under captain Giovanni Marabotto, she left Palermo with her sister Alberico da Barbiano, carrying urgent fuel supplies to planes based in Tripoli. However admiral Toscano, commander of the IV Division believed that surprise vanished after the RAF spotted them and ordered to turn back. On December 12th, the need was still desperate and the two cruisers were ordered to leave again and sail to Tripoli, using their great speed to try to slip in by night. However, they were intercepted off Cape Bon on December 13th before dawn by four enemy destroyers: HMS Sikh, Legion and Maori, two of the powerful Cossack class, and the Dutch HrMs Isaac Sweers, all of the 4th Destroyer Flotilla.

Di Giussano fired three salvos but was struck by at least two torpedoes (on a volley of six from HMS Maori, as well as artillery fire. After some pipes burst, burning drivers in the machinery and stopping the left propeller, the ship started to slow down. Fire developed in a less fast and violent way than on the Da Barbiano, but she was immobilized, and eventually she has to be abandoned, left sinking after breaking in two, at 4.20 am.

283 men of the 720 in total died in the sinking. A sailor left on board testified hit the ship caught fire immediately after being hit, fuel spilling and extending the fire rapidly to the surrounding sea, therefore many sailors died in the flames after jumping while while others drawn.

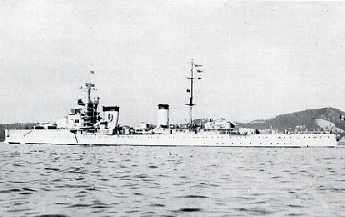

Alberico Da Barbiano

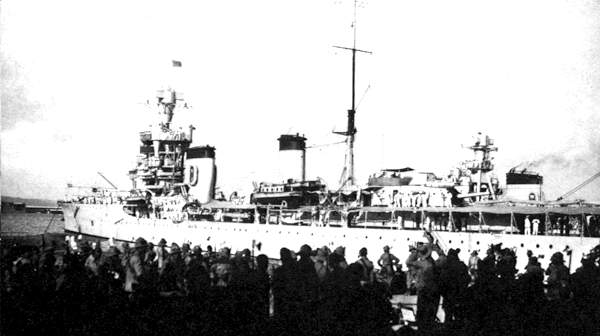

Alberico da Barbiano in 1940

The Da Barbiano entered service in the early 1930s, carrying out missions in the western Mediterranean during the Spanish civil war. On 10 June 1940, she joined forced with the 1st Squadron, as part of the IV Cruiser Division. She took part as her sister ships in the battle of Punta Stilo, catapulting an IMAM Ro.43 seaplane to try to spot the British fleet. She later covered the supply convoys to North Africa along 7 missions covering 13,241 miles.

On 12 December 1941 she left Palermo in Sicily with Alberto di Giussano to carry urgent fuel supplies to Tripoli. The first attempt previously has been recalled by the admiral, fearing an ambush as their group was spotted by aviation. Like her sister ship, she was caught on December 13th during this new trip off Cape Bon, by the British 4th Destroyer Flotilla, four enemy destroyers (Sikh, Legion, Maori, Isaac Sweers) and the attack was so sudden and brutal she could only scramble in due time the heavy machine gun posts to react. The Alberico Da Barbiano received three torpedoes from HMS Sikh, Legion and Maori, plus man hits of HE shells.

She caught fire and starting sinking, set adrift and shaken by many explosions. This mayhem lasted for 10 minutes. Later she turned upside down at 3.35 am and dive to the bottom, carrying with her most of her crew a mere ten minutes after the attack started. 534 survived out of 784 men, comprising the admiral Antonino Toscano, commander of the IV Division, but also division captain Giorgio Rodocanacchi. Both could scape but decided to stay with their ship sinking, and were posthumously decorated with the Gold Medal for Military Valor as well as machine-gun officer Lieutenant Franco Storelli. Her Wreck was found by the 2007 “Altair” expedition sponsored by Cressi, lying at a depth between 60 and 70 meters.

Bartolomeo Colleoni

Bartolomeo Colleoni entered service in the early 1930s, carrying patrols in the western Mediterranean during the Spanish civil war.

In November 1938 she was sent to relvieve the Raimondo Montecuccoli in the Far East station, arriving off Shanghai on December 23, 1938. She remained there until the war broke out between the UK and Germany and on 1 October 1939, was relieved herself by the corvette Lepanto, and returned to Italy on 28 October. The “Commodore” by Arturo Catalano Gonzaga di Cirella, published a book about the event in 1998.

The Bartolomeo Colleoni, received IMAM Ro.43 seaplanes, launched from a prow’s catapult. She was part of the 2nd Cruiser Division, 2nd Squadron, together with Bande Nere. On June 10, 1940 she made a a sortie to lay mines in the Sicily Channel, and on July 6 escorted a large convoy of supplies from Naples to Benghazi. These were reinforcement troops from Esperia and Calitea carried onboard the freighter Marco Foscarini, Vettor Pisani and Francesco Barbaro. On 9 July she took part in the battle of Punta Stilo, launching her planes to try to spot the British fleet.

On 18 July she sailed from Tripoli with delle Bande Nere as flagship of Admiral Ferdinando Casardi) bound to the island of Leros in the Aegean Sea. Indeed British activity there was causing concern and both cruisers were made ready to launch raids against British ships. At dawn on July 19 however, as they had been spotted by the RAF th day before, they were intercepted by the cruiser HMAS Sydney and five destroyers off Cape Spada in Crete.

The battle of Cape Spada saw both cruisers heavily engaged, Colleoni had her engine room wrecked by fire and the ship immobilized, an easy target for torpedoes. Admiral Casardi thought he faced two cruisers and four destroyers and ordered the surviving Bande Nere to flee, chased by HMAS Sydney, while himself stayed on the Colleoni, immobilized and in flames (the blow’s ammunition depot exploded and cut it in two). She was indeed soon targeted with a full torpedo volley from British destroyers HMS Ilex and Havock.

As a result of multiple simultaneously hits, the ship dramatically exploded and sank rapidly at 8.29, bringing with her 121 sailors. 525 were however recovered and taken prisoner by the British. Commander Umberto Novaro has been seriously injured but was saved by her crew and dragged out of the bridge where he clang to the wheel to sink with her ship. He would die however four days later in Alexandria as a POW. The Royal Navy gave him full military honors in the presence of the surviving crew and captain Eugenio Martini, former second in command of the cruiser Bartolomeo Colleoni.

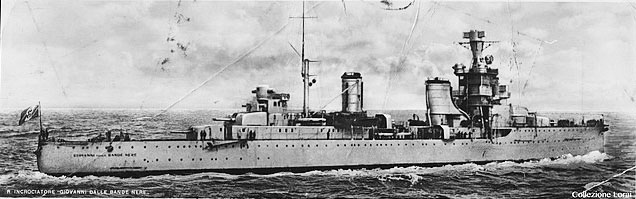

Giovanni Delle Bande Nere

Giovanni Delle Bande Nere started her career in April 1939, takng part in the occupation of Albania, covering coastal operations and firing in coastal positions. She was part of a special unit under command of the admiral Arturo Riccardi. Heavy cruisers of the Zara class together with 13 destroyers and 14 torpedo boats plus several steamers carrying a total of 11,300 men and 130 tanks plus equipments and supplies were to be landed. The action was largely unopposed, contraried by a few salvos fired in Durres and Santi Quaranta. They met overall very little resistance. Main prts were captured and soon the capital fell, with King Zog forced into exile.

Later, Giovanni delle Bande Nere was equipped with IMAM Ro.43 seaplanes, one launched from a a forward deck catapult and the other in standby like her sister-ships. She teamed with the Colleoni, making the 2nd Division and fought at the battle of Punta Stilo on 9 July 1940 a few days after escorting a large convoy to Libya. On 19 July, she was sent to the Aegean, still with the Colleoni, to raid enemy traffic. But soon the pair met the Australian cruiser HMAS Sydney and five British destroyers. The battle of Cap Spada proved fatal to the Colleoni, badly hit and immobilized in flames and later “executed” by torpedoes from the destroyers. Meanwhile admiral Ferdinando Casardi, commander of the II Division had raised his mark on the Bande Nere and was injured by a hit, ordering the ship to flee, chased down by the HMAS Australia thanks to her speed. However in the process, she was hit a second time and speed soon fell to 29 knots while sailors frantically tried to repair the damage and allow her to reach 32 knots with temporary repairs again. Sydney was also hit in return by 6-in shells of the Bande Nere, her forward funnel badly damaged. She eventually preferred give up. All her way out, Bande Nere risked to be catch and attacked by the RAF nearby. She would deplore 8 dead and 16 wounded during this battle.

Later Bander Nere would actively participate in convoy duties for Libya. 5-7 February 1941 she escorted Conte Rosso, Esperia, Marco Polo and Calitea to Tripoli, carrying the entire “Ariete” armored division. On May 24, 1941 she teamed with the cruiser Armando Diaz and the destroyers Ascari and Corazziere, making indirect escort cover for numerous convoys, ready to fell on any threat. On February 25, Diaz was torpedoed by a submarine and sank almost with all hands. On 10 December 1941 Band Nere was requisitioned for supplying aviation petrol and materials to Tripoli, with two other light cruisers of the IV Division, Alberico da Barbiano and Alberto di Giussano. She was however at the second attempt stuck in Palermo because of an engine problem. She renounced the mission which saw the destrouction of her two sister ships of the remaining IV Division in the night of 12-13 December. On 21 February 1942 however, she took part in Operation K.7, protecting two convoys to Libya, an operation which ended with a full success.

On March 21 1942 she took part in a composite force sent against an English convoy heading for Malta. This was the second battle of the Sirte in which the Bande Nere duelled with the British cruiser HMS Cleopatra and was soon hit by a 6-in shell (152 mm), causing 15 deaths and substantial damage but she carried on the fight.

Author’s Illustration of the Bande Nere, just before being sunk by a single torpedo in April 1942. Notice: The reference for this 20 years old illustration is no longer viable. Caouflage not accurate.

On the morning of 1 April 1942, Bande Nere left Messina, heading for La Spezia, escorted by the destroyers Aviere and Torpedo boat Libra. At 9 am, some 11 miles from Stromboli, this small fleet was ambushed by the British submarine HMS Urge. One of her torpedo hit the Giovanni delle Bande Nere in the middle, breaking it in two. She quickly sank, dragging with her from 381 to 287 men according to various sources. Her wreck was found by the Italian naval minesweeper Vieste on 9 March 2019, while off Stromboli she made a routine technical verification and surveillance of the seabed.

Colleoni after her action with HMAS Sydney July 1940, as shown here, her bow was broken in two.

Technical specifications of the Giussano class

Displacement: 5,110 t. standard, 6,840 t. Full Load

Dimensions: 169.30 m long, 15.30 m wide, 5.30 m draft

Machinery: 2 propellers, 2 Belluzzo turbines, 8 Yarrow boilers, 95,000 hp.

Maximum speed: 36.5 knots

Protection: Belt 42, Deck 20, Turrets 23, Blockhouse 40-25 mm

Armament: 8 x 152 guns (4×2), 6 x 100 guns (3×2), 8×37 AA, 8×13.2 AA , 4×533 mm TTs (2×2)

Crew: 520

Read More/Src:

Conway’s all the world fighting ships 1922-47

it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Classe_Alberto_di_Giussano

againstallodds.fandom.com/wiki/Alberto_da_Giussano_class_light_cruiser

military.wikia.org/wiki/Giussano-class_cruiser

forum.worldofwarships.eu/topic/5736-the-di-giussano-aa-cruiser-project/

Genesis of Italian light cruisers (Italian web archive)

On associazione-venus.it

On laststandonzombieisland.com – G Delle Bande Nere discovered

conlapelleappesaaunchiodo.blogspot.com/2018/07/giovanni-delle-bande-nere.html

Alberico da Barbiano – Incrociatore leggero, su marina.difesa.it.

otivazione Motivazione della Medaglia d’Oro all’ammiraglio Toscano, al comandante Rodocanacchi.

www.quirinale.it/elementi/DettaglioOnorificenze.aspx?decorato=13244.

www.focus.it/cultura/storia/il-ritrovamento-del-relitto-dell-incrociatore-italiano-da-barbiano

A pag. 82 del testo citato si accenna alla fragilità strutturale della nave.

Gordon Smith, Royal Navy casualties, killed and died, March 1942

Daniele Ranocchia, Le Operazioni Navali nel Mediterraneo

Giovanni delle Bande Nere – Incrociatore leggero, marina.difesa.it.

Pietro Cristini, Vita operativa degli incrociatori

The Modeller’s Corner:

https://www.regiamarinamas.net/id91.htm

https://www.scalemates.com/brands/delphis-models–243

nntmodell.com/en/Ships/Ship-Kits/Giussano.html

EVA scale kits FB page

Latest Facebook Entry -

Latest Facebook Entry -  X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive

X(Tweeter) Naval Encyclopedia's deck archive Instagram (@navalencyc)

Instagram (@navalencyc)

French Navy

French Navy Royal Navy

Royal Navy Russian Navy

Russian Navy Armada Espanola

Armada Espanola Austrian Navy

Austrian Navy K.u.K. Kriegsmarine

K.u.K. Kriegsmarine Dansk Marine

Dansk Marine Nautiko Hellenon

Nautiko Hellenon Koninklije Marine 1870

Koninklije Marine 1870 Marinha do Brasil

Marinha do Brasil Osmanlı Donanması

Osmanlı Donanması Marina Do Peru

Marina Do Peru Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Regia Marina 1870

Regia Marina 1870 Nihhon Kaigun 1870

Nihhon Kaigun 1870 Preußische Marine 1870

Preußische Marine 1870 Russkiy Flot 1870

Russkiy Flot 1870 Svenska marinen

Svenska marinen Søværnet

Søværnet Union Navy

Union Navy Confederate Navy

Confederate Navy Armada de Argentina

Armada de Argentina Imperial Chinese Navy

Imperial Chinese Navy Marinha do Portugal

Marinha do Portugal Mexico

Mexico Kaiserliche Marine

Kaiserliche Marine 1898 US Navy

1898 US Navy Sovietskiy Flot

Sovietskiy Flot Royal Canadian Navy

Royal Canadian Navy Royal Australian Navy

Royal Australian Navy RNZN Fleet

RNZN Fleet Chinese Navy 1937

Chinese Navy 1937 Kriegsmarine

Kriegsmarine Chilean Navy

Chilean Navy Danish Navy

Danish Navy Finnish Navy

Finnish Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Polish Navy

Polish Navy Romanian Navy

Romanian Navy Turkish Navy

Turkish Navy Royal Yugoslav Navy

Royal Yugoslav Navy Royal Thai Navy

Royal Thai Navy Minor Navies

Minor Navies Albania

Albania Austria

Austria Belgium

Belgium Columbia

Columbia Costa Rica

Costa Rica Cuba

Cuba Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia Dominican Republic

Dominican Republic Haiti

Haiti Hungary

Hungary Honduras

Honduras Estonia

Estonia Iceland

Iceland Eire

Eire Equador

Equador Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Latvia

Latvia Liberia

Liberia Lithuania

Lithuania Mandchukuo

Mandchukuo Morocco

Morocco Nicaragua

Nicaragua Persia

Persia San Salvador

San Salvador Sarawak

Sarawak Uruguay

Uruguay Venezuela

Venezuela Zanzibar

Zanzibar Warsaw Pact Navies

Warsaw Pact Navies Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary

Bundesmarine

Bundesmarine Dutch Navy

Dutch Navy Hellenic Navy

Hellenic Navy Marina Militare

Marina Militare Yugoslav Navy

Yugoslav Navy Chinese Navy

Chinese Navy Indian Navy

Indian Navy Indonesian Navy

Indonesian Navy JMSDF

JMSDF North Korean Navy

North Korean Navy Pakistani Navy

Pakistani Navy Philippines Navy

Philippines Navy ROKN

ROKN Rep. of Singapore Navy

Rep. of Singapore Navy Taiwanese Navy

Taiwanese Navy IDF Navy

IDF Navy Saudi Navy

Saudi Navy Royal New Zealand Navy

Royal New Zealand Navy Egyptian Navy

Egyptian Navy South African Navy

South African Navy

Ukrainian Navy

Ukrainian Navy dbodesign

dbodesign

Sorry to bother you but you mispelled a couple of names on this page. In the title you wrote GIUSSANO wrong and the complete names are ALBERTO DI GIUSSANO and ALBERICO DA BARBIANO, also Italian light cruiser were named CONDOTTIERI, plural of Condottiero, you wrote it wrong the first time.

Also it’s impossible to me to comment below the Regia Marina main page or the Littorio class page, therefore I’ll write it here. It is LITTORIO not litorrio, you wrote it wrong in that article’s title and multiple times in that article itself.

I’m not a native english speaker so I’m sorry if I made some mistakes, have a good time and good luck with this great site!

Both fixed, thanks !

I added a notice on the Giussano to precise it was a traduction of a 15 years old other post, but it’s not up to standard of the Garibaldi class and will be proofread and split up into two articles in the close future.